Gongoozling

A CELEBRATION OF CANALS

Gongoozler: an idle and inquisitive person who stands staring for prolonged periods at anything out of the common.

H.R. De Salis, A Handbook of Inland Navigation, 1901

Although canal building is the subject of this book, it is only the beginning of the canal story. It seems a pity to end without at least a brief look at the end product of so much effort expended by so many people, and so this chapter takes a brief look at the canals through the eyes of a variety of gongoozlers. The curious spectators of the eighteenth and nineteenth century were little different from those of our own time: where a group of men were found at work, another group could always be found to stand and watch them. Even before the canals were finished there was no shortage of spectators, though they were not encouraged by the company: ‘The Lancaster Canal Committee request the Public in general, that their curiosity may lead them to trespass as little as possible on private property: Breaking or pulling down Gates & Hedges are offences at all times without excuse, and if the offenders are discovered they will be prosecuted as the Law directs.’1

But, when work was finished and the Grand Opening Day finally arrived, then anyone and everyone could come and stare. The Very Important got to ride in the boats, while the lesser beings had to make do with watching from the towpath. Everyone had a splendid time: the military bands played suitable patriotic and stirring airs; the proprietors made suitably pompous speeches; poets recited atrocious but lively verses, and the canal workers set about the serious business of getting drunk at the company’s expense. The weather was, of course, fine; the scenery, inevitably, magnificent. Even profits were temporarily forgotten – at least, so the commentators claimed. Here is the whole magnificent scene described by The Times:

‘On Monday last, the navigation of this Canal, from the Thames to the town of Croydon was opened. The proprietors met at Sydenham and there embarked on one of the company’s barges, which was handsomely decorated with flags, &c. At the moment of this barge’s moving forward an excellent band played ‘God Save the King’, and a salute of 21 guns was fired. The proprietors’ barge then advanced, followed by a great many barges, loaded some of them with coals, others with stone, corn &c, &c.

The gay fleet of barges entered Penge Forest. The canal passes through this forest in a part of it so elevated, that it affords the most extensive prospects, comprehending Beckenham, and several beautiful scattered villages and seats.

The proprietors found their calculations of profit irresistably interrupted, by these rich prospects breaking upon them from time to time, by openings among the trees, and as they passed along, they were deprived of this grand scenery only by another, and no less gratification that of finding themselves gliding through the deepest recesses of the forest, where nothing met the eye but the elegant windings of the clear and still Canal, and its borders adorned by a profusion of trees.

When the proprietors approached the basin at Croydon, they saw it surrounded by many thousands of persons, assembled to greet, with thanks and applause, those by whose patriotic perseverance so important a work had been accomplished. It is impossible to describe, adequately, the scene which presented itself, and the feelings which prevailed, when the Proprietors’ barge was entering the basin, at which instant the band was playing ‘God Save the King’, the guns were firing, the bells of the churches were ringing; and this immense concourse of delighted persons were hailing by universal and hearty, and long continued shouts, the dawn of their commerce and prosperity.

The following air, written by a Gentleman, while sailing to Croydon, was most zealously and ably sung by one of the proprietors, Mr J. Walsh, and was received with great applause:

All hail this grand day when with gay colours flying,

The barges are seen on the current to glide.

When with fond emulation all parties are vying,

To make our Canal of Old England the pride.

CHORUS

Long down its fair stream may the rich vessel glide.

And the Croydon Canal be of England the pride.

And may it long flourish, while commerce caressing,

Adorns its gay banks with her wealth-bringing stores;

To Croydon, and all round the country a blessing,

May industry’s sons ever thrive on its shores!

And now my good fellows sure nothing is wanting

To heighten our mirth and our blessings to crown,

But with the gay belles on its banks to be flaunting.

When spring smiles again on this high-favoured town.’

The Times, 27 October 1809

Sometimes there were unofficial as well as official opening ceremonies, and these did not always work out quite so happily. When the lock joining the Gloucester & Berkeley Canal to the River Severn was opened, three local lads decided to brighten up the proceedings by firing their own salute from a cannon – unfortunately, the cannon was ancient and the wadding was wet, and the whole thing exploded as soon as it was lit. Mostly, though, there was no more serious accident to disturb the opening day than the occasional drunk falling into the canal.

Once the canal was open, there were even more interesting opportunities for the idly curious. There was, for example, the opportunity to take a trip on the canal in a pleasure boat. Canals-for-pleasure is no modern concept: Thomas Bentley, in an early version of his pamphlet promoting the Trent & Mersey Canal, suggested that gondolas might be introduced on to the canal – a proposal that conjures up romantic visions of England as a kind of overgrown Venice. Even if gondolas never did come to grace the Potteries, and there were no dark-eyed gondoliers to serenade the maidens of Stoke-on-Trent, the reality was romantic enough. The Rev Shaw took a trip through the old Harecastle tunnel:

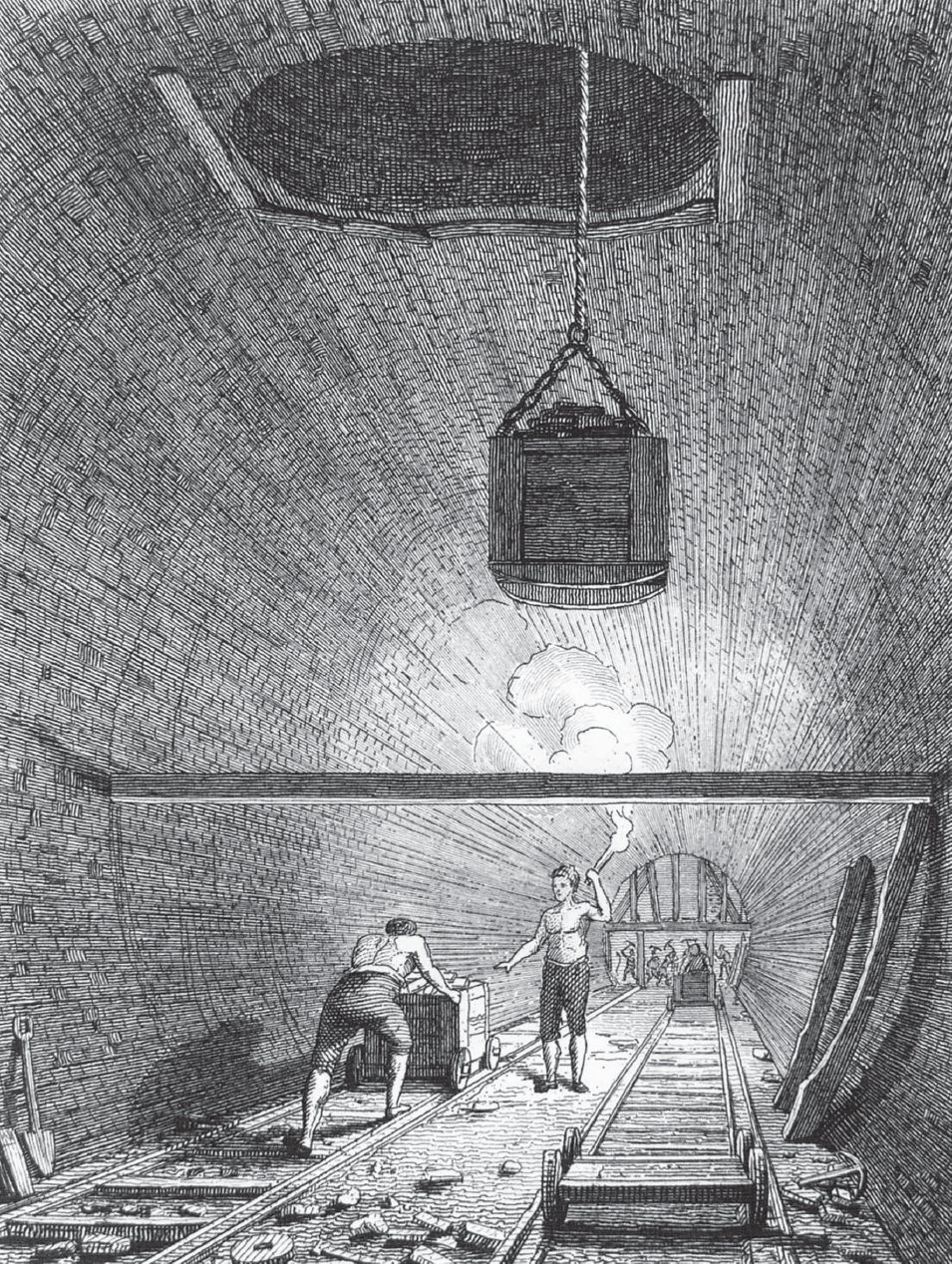

‘I visited this tunnel about the year 1770, soon after it was finished, when pleasure boats were then kept for the purpose of exhibiting this great wonder; the impression it made on my mind, is still very fresh. The procession was solemn; some enlivened this scene with a band of music, but we had none; as we entered far, the light of candles was necessary, and about half-way, the view back upon the mouth was like the glimmering of a star, very beautiful.’2

But the idyllic mood soon faded. The Trent & Mersey was built for commerce, not for sightseeing, and the sound of commerce would have soon drowned out the noise of the ‘band of music’, even if one had come along. ‘The various voices of the workmen from the mines, &c. were rude and aweful, and to be present at their quarrels, which sometimes happen when they meet, and battle for a passage, must resemble greatly the ideas we may form of the regions of Pluto.’

It was all too much for the passenger. The mood was gone, and he soon gave up admiring the beauty and got down to thinking about the economic value of the tunnel and the canal in general:

‘And though the expense attending this astonishing work was enormous, so as to promise little or no profit to the adventurers; yet in a few years after it was finished, I saw the smile of hope brighten every countenance, the value of manufactures arise in the most unthought of places; new buildings and new streets spring up in many parts of Staffordshire, where it passes; the poor no longer starving on the bread of poverty; and the rich grow greatly richer. The market town of Stone in particular soon felt this comfortable change; which from a poor insignificant place is now grown neat and handsome in its buildings, and, from its wharfs and busy traffic, wears the lively aspect of a little seaport.’

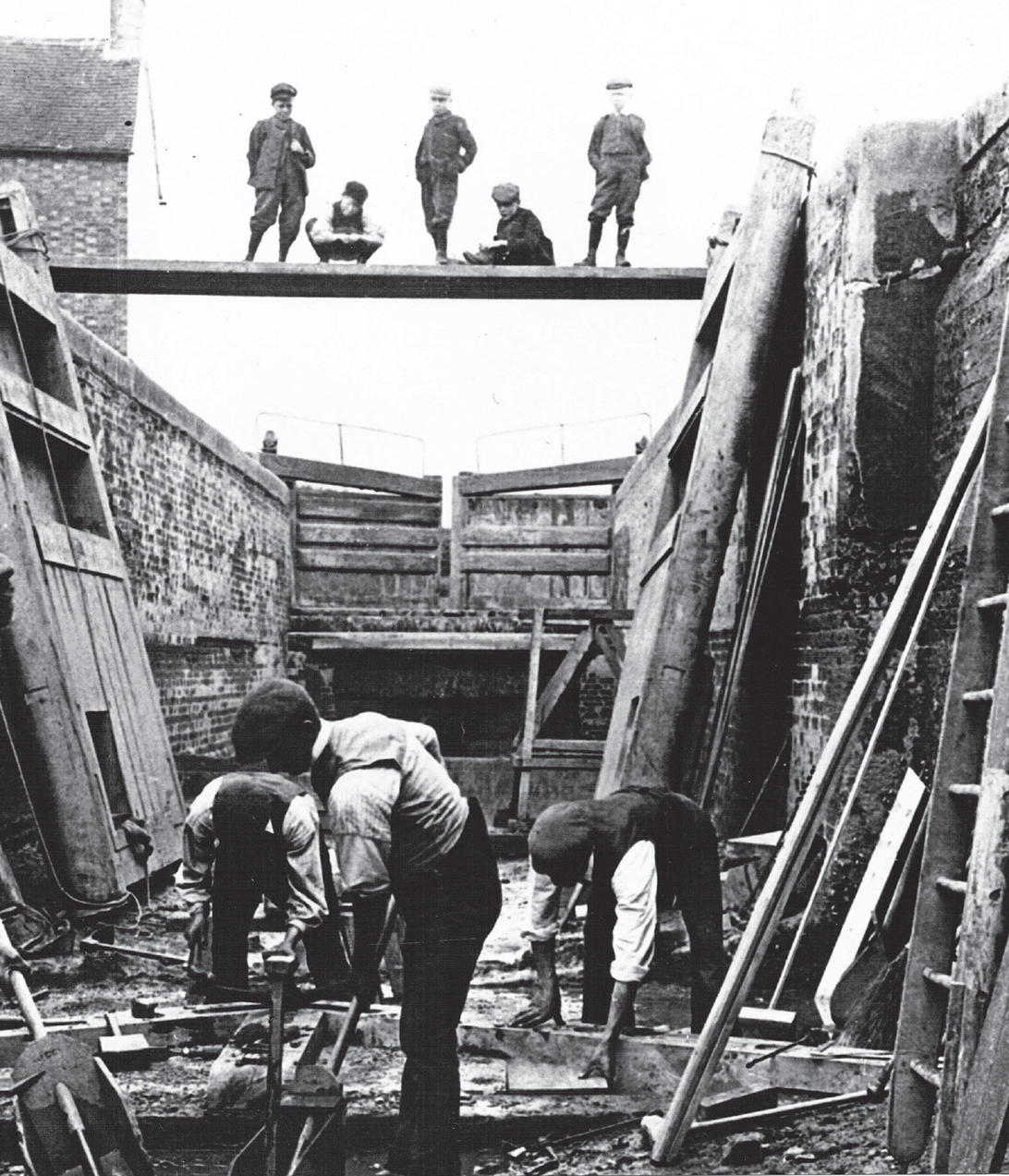

The pleasure of watching others at work. (British Waterways)

This was, of course, what the canals were really all about. For every spectator who came to satisfy his curiosity for seeing something new, there were half a dozen who came to see how prices were affected in towns along the route, the effects on manufacturers’ profits and on the supply of food and other goods, and the income from tolls. The statistics for cost savings made impressive reading:

‘The following statement of the differences of prices of carriage of goods, per ton, by Canal and Land, will strongly convince the great National Utility of Inland Navigation.’

|

Canal |

Land |

Between Gainsbro and Birmingham |

£1 10 |

£3 18 |

Manchester & Etruria, the centre of the Potteries |

0 15 |

2 15 |

Ditto and Birmingham |

1 10 |

4 0 |

Ditto and Stourport |

1 10 |

4 13 |

Liverpool and Wolverhampton |

1 5 |

5 0 |

Ditto and Birmingham |

1 10 |

5 0 |

Ditto and Stourport |

1 10 |

5 0 |

Chester and Wolverhampton |

1 15 |

3 10 |

Ditto and Birmingham |

2 0 |

3 10 |

Ditto and Stourport |

2 0 |

3 10 |

Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 1 December l792

Thomas Pennant found that of all the sights that he saw on his tour through England, there was nothing that could inspire him to greater heights of enthusiasm than the contemplation of the economic benefits brought by the Trent & Mersey Canal:

‘Notwithstanding the clamours which have been raised against this undertaking, in the places where it was intended to pass, when it was first projected, we have the pleasure now to see content reign universally on its banks, and plenty attend its progress. The cottage, instead of being half-covered with miserable thatch, is now secured with a substantial covering of tiles or slates, brought from the distant hills of Wales or Cumberland. The fields, which before were barren, are now drained and, by the assistance of manure, conveyed on the canal toll-free, and are clothed with a beautiful verdure. Places which rarely knew the use of coal, are plentifully supplied with that essential article upon reasonable terms: and, what is still of greater public utility, the monopolisers of corn are prevented from exercising their infamous trade; for, the communication being opened between Liverpool, Bristol and Hull, and the line of the canal being through countries abundant in grain, it affords a conveyance of corn unknown to past ages. At present, nothing but a general dearth can create a scarcity in any part adjacent to this extensive work.

These, and many other advantages, are derived, both to individuals and the public, from this internal navigation. But when it happens that the kingdom is engaged in a foreign war, with what security is the trade between those three great ports carried on; and with how much less expense has the trader his goods conveyed to any part of the kingdom, than he had formally been subject to, when the goods were obliged to be carried coastways, and to pay insurance?

I believe that it may be asserted, that no undertaking, equally expensive and arduous, was ever attempted by private people in any kingdom; and, in justice to the adventurers, it must be allowed, that, considering the difficulties they met with, owing to the nature of the works, or the caprice of persons whose lands were taken to make the canal, that ten years and a half was but a short time to perform it in; and that satisfaction has been made to every individual who suffered any injury by the execution of the undertaking. The profits arising from tonnage is already very considerable; and there is no doubt but that they will increase annually; and notwithstanding the enormous sum of money it has cost in the execution, the proprietors will be amply repaid, and have the comfort to reflect, that, by the conclusion of this project, they have contributed to the good of their country, and acquired wealth for themselves and posterity.’

Thomas Pennant, op. cit.

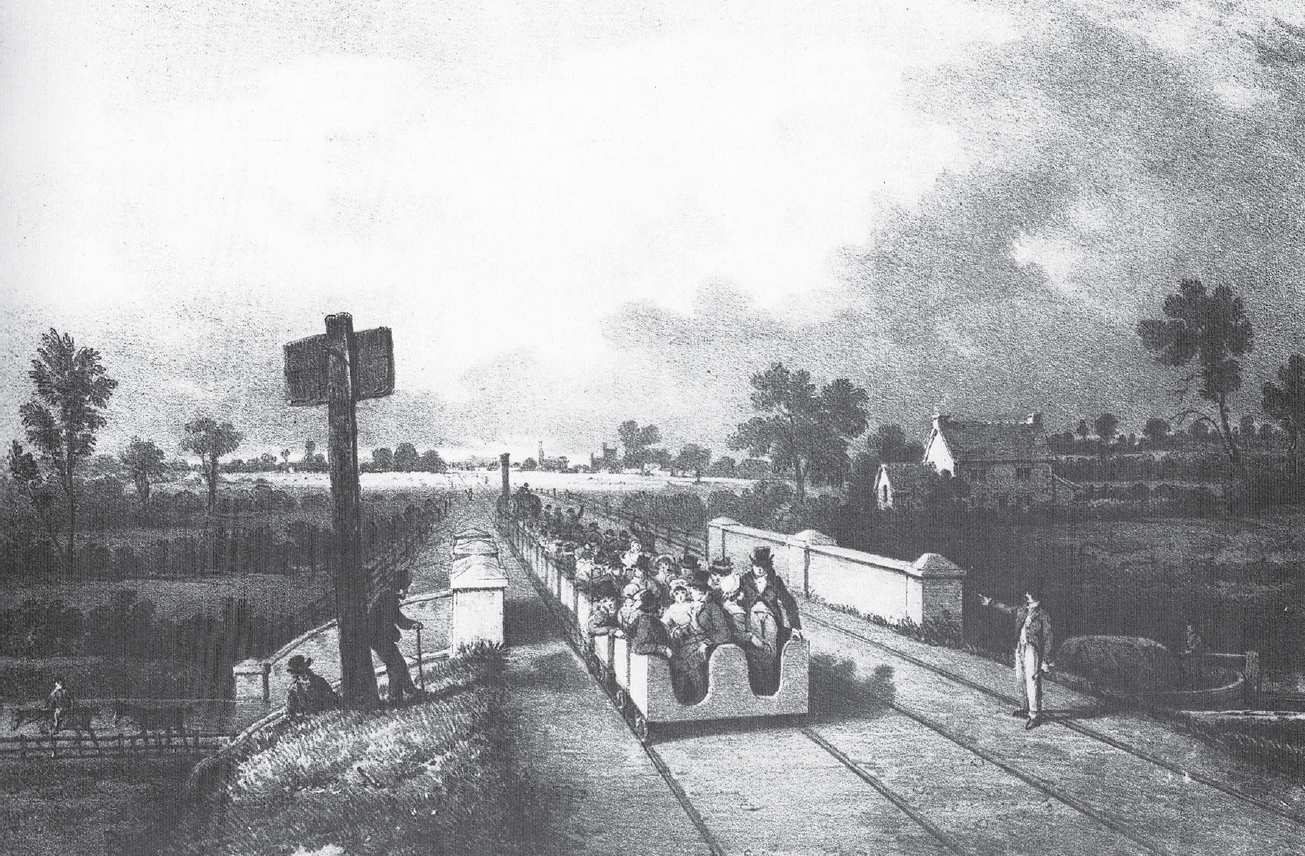

All was for the best in the best of all possible worlds, served by inland navigation. Fifty years later, the Trent & Mersey still prospered, with quarter-shares, originally costing £50, being offered for £620. But the Panglossian dream of unending prosperity for all canals which was so vigorously propagated by Pennant and other writers of the eighteenth century failed to materialise. It scarcely had the opportunity. The gongoozlers of the nineteenth century found a new object of curiosity – the steam engine that could move along on rails and could pull wagons filled with goods and passengers. The canal builders had hardly finished their work before the new age was upon them. The Duke of Bridgewater’s ‘damned tramroads’ came after all to put the canal system in the shade. Steadily, throughout the nineteenth century and into modern times, traffic on the canals declined. Some routes were kept open, many closed. Most of the existing waterways came under the control of the new railway companies, who had little incentive to maintain, let alone improve, them. The process was inevitable. The canal system was created to meet the rapidly expanding transport needs of the Industrial Revolution, and it is no exaggeration to say that without that system the Revolution could not have happened when it did, nor could it have spread in the way that it did. But the canal builders were also constructing the means to their own end: the waterways they built enabled industry to grow and flourish; that industrial growth in its turn fostered technological advances; and from those advances the steam engine developed as naturally as a plant from its seed. The development of the steam engine from its original static to its new mobile form came at just the right time. Once the first successful experiments with the locomotive had been made, there were no technical obstacles to putting the experiments to use. The railway engineers found a whole system of construction techniques and a body of skilled workmen ready and waiting for them – all by courtesy of the canal builders.

A beginning and an end: the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, crosses the Bridgewater Canal opened in 1761. (Museum of British Transport)

Workers in Islington Tunnel on the Regent’s Canal. (The Museum of London)

The canals were built to serve a commercial need. Tens of thousands of men were employed in their making and, for a brief period, they successfully met that need. The canals no longer fulfil that function, but they have found a new purpose, and every year now sees more and more pleasure boats thronging the waterway system. A new generation has discovered the delights of canal gongoozling. The canals have completed the transition from the practical to the picturesque, following the path described by Robert Southey for the Inverary Canal: ‘The canal is a losing concern to the subscribers; and Mr Haddon complains that it draws off the water from the Don, to the hurt of his mills … It is, however, a great benefit to the country, and no small ornament to it, with its clear water, its banks which are now clothed with weedery, and its numerous locks and bridges, all picturesque objects and pleasing, where you will find little else to look at.’3

The whole of the modern development of canals for pleasure boating, on a commercial scale, was foreseen over a century ago. Mr Robins, author of a History of Paddington, published in 1853, wrote:

‘The glory of the first public company which shed its influence over Paddington has, in a great measure, departed; the shares of the Grand Junction Canal Company are below par, though the traffic on this silent highway is still considerable; and the cheap trips into the country offered by its means during the summer months are beginning to be highly appreciated by the people, who are pent in close lanes and alleys; and I have no doubt that shareholders’ dividends would not be diminished by a more liberal attention to their want.’

Mr Robins was a good prophet and, no doubt, he would be gratified to see his prophecy fulfilled. The canals have become accepted as a part of the countryside, and seem to fit in as naturally as the streams and rivers. But what are now ideal escape routes from the pressures of a modern industrial world were once the lifelines of the earliest industrial society. They cost the effort of an army of men; they involved individuals from all levels of society; they made some men rich, and brought bankruptcy to others. But the canal builders achieved one unique distinction – they left behind a transport system that enhances the countryside through which it passes instead of destroying it. That part, at least, of the builders’ dream has come true.

The very last word ought to belong to the eighteenth century, the canal builders’ own age. And the best person to pronounce it is the ballad writer, whose enthusiasm and elan might often have outstripped his abilities, but in whose verses we can still capture the feeling of the time, and the excitement and the great promise that the coming of the canals brought to the country:

Come now begin delving, the Bill is obtain’d

The contest was hard, but a conquest is gain’d;

Let no time be lost, and to get business done

Set thousands to work, that work down the sun,

With speed the desirable work to complete,

The hope how alluring–the spirit how great?

By Severn we soon, I’ve no doubt to my mind,

With old father Thames shall an intercourse find.

With pearmains and pippins ‘twill gladden the throng,

Full loaded the boats to see floating along;

And fruit that is fine, and good hops for our ale,

Like Wednesbury pit-coal, will always find sale …

As freedom I prize, and my Country respect,

I trust not a soul to my toast will object;

‘Success to the Plough, not forgetting the Spade,

Health, plenty and peace, Navigation and Trade.’