Ewan Macdonald was born in Bellevue, PEI, on July 18, 1870, four years before Maud. After taking a teaching licence from Prince of Wales College, he taught school in his home district long enough to fund a degree at the Presbyterian training college, Pine Hill Divinity School, in Halifax. His father’s farm at Bellevue was at the other end of the Island from Cavendish. Ewan’s grandparents had emigrated with his father (age seven) from the Isle of Skye, Scotland, possibly escaping impoverished conditions brought on by the 1840 potato famine. A very handsome man, Alexander Macdonald (1833–1914) had married another Skye emigrant, Christie Cameron (1835–1920), after his first wife had died, leaving him a young daughter named Flora. Christie Cameron was the daughter of Ewan Cameron, a ship’s captain from Point Prim, PEI.

Alexander and Christie Macdonald raised a large family. Their lives were concerned with survival, not with the display of fine manners. Although Ewan’s father owned land in PEI, their household was decidedly rougher than Maud’s. Furthermore, as Highlanders, the Macdonalds came from a Gaelic-speaking tradition. It is unclear whether or not Ewan’s father, who in infirm old age signed his will with an “X,” was literate in English. (Although there had been a system of public education in Scotland since 1696, it was very uneven, and often nonexistent on the islands.) Ewan’s family may have come up from poverty, but they were kindly, gentle people, not judgmental like Maud’s family. They believed strongly in education, and had intelligence and ability.

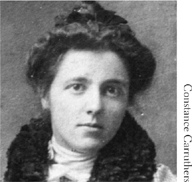

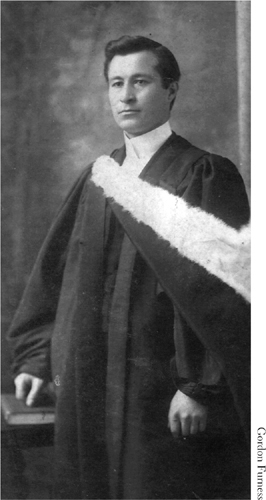

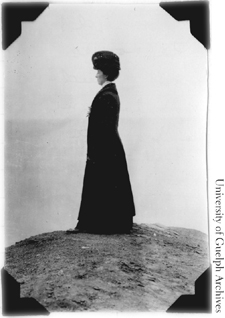

Ewan himself was a good-looking man, with a warm and dimpled smile, good teeth (particularly valued by Maud because hers were so small and crooked), and dark but “rosy” skin. It is likely that his parents spoke Gaelic at home because Ewan retained a pronounced Gaelic accent all his life. Maud found his Gaelic accent charming, even though it might have denoted a lower social class to many of Scottish and English extraction.

A minister needed a wife, and Ewan was looking for one, preferably with musical and social skills. He had already had one secret, failed romance: he had once been engaged to an older woman in his home community, but he had backed out, breaking the engagement. Now he was looking again for a suitable mate. At the point that Ewan became the new Presbyterian minister in Cavendish, the church also needed a new organist. Maud’s musical talents were mediocre, but she had noted the pleasant Ewan, as did several other spinsters in the area, including (as Maud believed) her friend, Margaret Ross of Stanley. The competition for the minister’s attention made the organist’s job more appealing. At twenty-nine, Maud was perilously close to the social scorn of spinsterhood. She accepted the position of church organist.

In the same year that Ewan was inducted, Maud’s cousin Frederica (“Frede”) Campbell turned nineteen. She was nine years younger than Maud, and they had not been close friends earlier. But now that Frede was older, she and Maud discovered that they were also “kindred spirits.” Frede was exceptionally gifted academically, with a unique combination of Macneill brilliance and Campbell vitality. She had met Ewan, and admired him, and this influenced Maud.

Subject to vacillating moods herself, Frede understood Maud, and a powerful sense of trust developed between them. With Frede, Maud could discuss her deepest fears: that she would have to leave Cavendish after her grandmother died and the house finally went to Uncle John F.; that she might not find a man to marry; that if she did, she would be too old to have the children she wanted; that she might have a mental breakdown like those regularly described in Island newspapers. With her cousin Frede, Maud found that she could “rinse out her soul” in a way not possible with anyone else.

From 1898 onward, the “black dog” of depression had intermittently stalked Maud, resulting in sleepless nights, restless agitation, skittery thought processes; at times she even reported an inability to make sense of words on a page. Her journals provide some remarkable descriptions of these episodes, written after they had passed. Only from a distance could she shape and treat them artistically. For example on June 30, 1902, she wrote:

[I] did not sleep until dawn. Every trouble I ever had came surging up with all its old bitterness—and all my little present day worries enlarged themselves to tenfold proportions and flew at my throat. Life seemed a horrible, cruel, starving thing and I hated it and wished I were dead. I cried bitterly in sheer heart sickness and loneliness. Anything like that wrings the stamina out of me.

In April 1903, before Ewan had come to preach for the call, she recorded brooding, feeling constantly tired, and wanting to “fall asleep and never wake again.” Old friends like Mary Campbell (now Mary Beaton) had married and were expecting babies. The year 1903 saw still more weddings: notably the marriage of the Reverend Major MacIntosh, the Cavendish minister before Ewan, to Mabel Simpson, church organist; and the marriage of Maud’s cousin, George Campbell of Park Corner, to Ella Johnstone. In 1904 Maud’s friend Fanny Wise married R. E. Mutch, and Maud’s cousin Murray Macneill (who was now a professor at Dalhousie) married Dorothy Holmes of Halifax. Then, in 1905, Myrtle Macneill, Maud’s younger “cousin,” married Ernest Webb and Maud was also a bridesmaid at the wedding of her friend, Bertha MacKenzie, solemnized by the new minister, the Reverend Ewan Macdonald.

Between September 1903 and May 1905, Ewan Macdonald boarded at Stanley, one of his three ministerial charges (Stanley, Rustico, and Cavendish). All the unmarried spinsters, including Maud, had their eyes on him. During this period, Maud made several trips to Stanley to visit Frede. Now that this unmarried minister was in the picture, Maud began romanticizing the cozy little house in New London where her parents had started housekeeping together. At home, she rummaged through her memories of past male friends: Nate Lockhart, Herman Leard, Will Pritchard. She read a packet of Will’s letters in March 1904, and felt,

as if a cruel hand were tightening its clutch on my throat.… I don’t know why Will’s letters should have such an effect on me … they were not such as would be expected to stir up such a riot of feeling in me. But I’ve been lonely and sick at heart all day, and I just long wildly for his bright friendliness again … I cannot understand my mood at all. (March 16, 1904)

In January 1905, she wrote poignantly in her journals of how unloved she had felt in her childhood. Although the childhood she describes was not the childhood that might objectively be recognized from her other accounts, it does reflect how she re-visioned her childhood when she was depressed. Now, in 1905, her moods cycled rapidly: she was a “winged spirit” on March 16; she was “a caged creature” March 23; the following week “a prisoner released.” But change was coming.

On April 14, 1905, she began to have pleasant dreams. Rumours had been afloat that Ewan Macdonald was moving from Stanley to Cavendish, which meant to Maud that she had perhaps caught his eye. As soon as this move was in the wind, Maud’s spirits ascended rapidly. She started planning her first full-length book. (She had by this time published at least 168 short stories and 192 poems in periodicals.)65

In early May 1905, Ewan moved to Cavendish, taking a room with the John Laird family. This was easy walking distance from the Presbyterian church, and the church was next to the Macneill homestead. From her bedroom window, Maud could see people walking up their lane to the post office, or hear them enter if they came into the kitchen from the back of the house from another direction.

The first evening that Ewan came to call for his letters, Maud—who normally did her writing in the privacy of her upstairs bedroom as soon as it was warm enough in spring—was suddenly positioned in the kitchen, apparently admiring the last rays of light and ready to engage him in cheerful conversation. By her account he entered just as she had finished the first lines of this first full-length novel, to be named Anne of Green Gables. She put her writing aside to chat with the amiable minister. Her new duties as church organist provided matter for discussion.

Perhaps it is true that her basic idea for the novel—as she claimed in one account—originated from a newspaper clipping about a couple requesting an orphan boy to help them, but instead being sent a young girl by mistake. What is certain, however, is that the narrative flowed smoothly out. The main character in this novel was as lively as Maud herself, and resembled her in other ways. The heroine, Anne Shirley, was an unwanted orphan, just as Maud had felt herself to be when she revisited her childhood in January 1905. The first third of the novel presented Anne—a child of wildly fluctuating moods—as the most lovable creature imaginable. She would find love and acceptance in her new home, and then she would sacrifice herself at the end by doing exactly what Maud had done when she’d come home to stay with her grandmother. At the novel’s conclusion, a more mature Anne would sit, as Maud had so often done, looking out her window, wondering what was around the “bend in the road.” The novel was a version of Maud’s own emotional and spiritual autobiography, a blend of her childhood as it was and as she had reconfigured it in the entry of January 1905, followed by the high brought about by the happy anticipation of Ewan’s impending move to Cavendish. Only the facts and names were changed. Maud manufactured a history for Anne in order to obscure her heroine’s origin in her own life. (Anne is the orphaned daughter of two schoolteachers who died of a fever, and her subsequent life includes misery and abuse in various homes and an orphanage until she is adopted by the Cuthberts.) In fact, Anne was a creative rendition of the volatile and lovable child Maud herself had been—not an orphan, but one carefully raised by a loving and supportive grandmother and a difficult, judgmental grandfather whose harsh words had made Maud feel like a charity case at times.

In May 1905 Maud had published a story called “The Hurrying of Ludovic.” In this story, a courtship fails to advance because sluggish Ludovic Speed will not propose to his lady, the thirty-something Theodora. Ludovic is characterized by his “unhesitating placidity” and his eyes “with a touch of melancholy in them” as he shambles down the long road to visit the ever-hopeful Theodora. He has “a liking for religious arguments: and talks well enough when drawn out.” Theodora plots to get this “big, irritating goose” to propose after fifteen years of courting. There were about fifteen months between the time Ewan was inducted as the Cavendish minister and the time Maud sent this story off for publication. The Canadian Magazine published it in May 1905, the month that Ewan strategically moved to Cavendish and started actively courting her. Fifteen months may have seemed like fifteen years to a woman like Maud, who was thirty and had been hopefully encouraging the clueless new minister since the day he preached for the call in spring 1903.

Before she wrote Anne of Green Gables, Maud had been doing better and better financially. Her yearly income from writing was already climbing towards the astonishing sum of $500 a year from short stories and poems. (For comparison, Ewan’s salary in his triple-charge parish was $765 in 1909, and ministers were well paid professionals.)

Maud wrote her Anne manuscript in a flowing hand that seemed to skim the story off a teeming brain. Luckily for Maud, her aging Uncle Leander and his wife did not come to the Island for their usual two months of summer vacation that year. In the absence of this interruption, Maud wrote Anne of Green Gables with manic energy throughout the entire year of 1905, apparently completing the book by January 1906. There was no time to write in her journals in that period—and not much need, either, since they were, on the whole, the place where she vented her unhappiness, and in this period, her life was looking more promising, with a suitor on the scene.

Anne of Green Gables was written in the most positive and forward-looking part of Maud’s life, and it is her most sparkling novel. Anne is a fictional character, of course. Yet, she is as much the result of the coming together of a real man and a real woman as if she were a real flesh-and-blood child. Lucy Maud Montgomery is certainly the “mother” who conceived, carried, and delivered Anne. But Ewan played—literally—a seminal role in the production of this book: he was the catalyst that pulled Maud out of a period of depression, providing the energy to take on a full-scale book. His attentions sustained her spirits so that she wrote with a “wingèd” pen, producing the entire novel in approximately ten months, in longhand, between spring 1905 and early 1906.66

Maud’s “gift of wings” had finally enabled her to take flight, thanks to the astonishing effect of the dimpled and rosy-cheeked Ewan. In spite of—or perhaps because of—the afflictions in her life, Maud had written her first novel, the one that would make her famous throughout the English-speaking world.

Anne of Green Gables is only one of many novels about orphans written in this era, but it has outshone all of them. Part of the book’s power comes from the way Maud draws on her own emotional experience, and reconfigures her own past. Anne is a sensitive and very bright orphaned child who has had disastrous experiences in homes where she was unloved and exploited. By accident, she is sent to the home of two elderly people, brother and sister, who had asked for a boy to help them on their farm. Matthew Cuthbert loves little Anne from the start, but dominant, rigid Marilla plans to return her to the orphanage since she isn’t what they’d asked for. When Anne wails, “You don’t want me because I’m not a boy,” she is expressing Maud’s lifelong sorrow.

One third of the way through the book, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert decide to keep Anne because their sense of duty tells them they can do something for this little waif. Marilla trains her to behave in acceptable ways, and as she grows up Anne enriches their lives and endears herself to the entire community. As the novel ends, she is a young woman poised to take flight. But then death claims Matthew. Because aging Marilla can stay in her home only if someone stays with her, Anne curtails her ambitions in order to repay to Marilla her debt of gratitude.

Anne and Marilla are as different in temperament as emotional little Maud and her Grandmother Macneill had been. When Anne comes to Avonlea (a community like Cavendish), she is a little chatterbox given to extravagant language and excessive emotions. She is either in the “depths of despair” or overexcited with her enthusiasms. She is impulsive and gets into all kinds of funny scrapes. Her most noteworthy trait is her fertile imagination. Staid, sensible Marilla guides Anne into curtailing her wild, romantic excesses of words and actions. Anne wins Marilla’s love, just as Maud did her grandmother’s, as she matures.

Matthew and Gilbert play supportive roles in the novel that mimic Ewan’s role in real life. Ewan was as much taken by Maud’s charming talk as Matthew is by Anne’s. Matthew is as kind and nonjudgmental as Ewan was. And Ewan Macdonald, as suitor, was waiting in the wings, just like Anne’s beau, Gilbert Blythe. In Ewan’s attentions, Maud finally found what Anne sought: to be loved and valued.

Maud’s own community of Cavendish had known her as an impulsive and sometimes otherworldly child, as a difficult-to-control and flirtatious teen, and as a moody young woman who seemed suspiciously off-balance at times. Maud took all the difficult qualities of the child she had been, things that would have been the subject of community gossip, and she turned them into endearing traits in little Anne. By the time Ewan Macdonald appeared on the scene, Maud, approaching twenty-nine, had new self-understanding. In creating Anne so like herself, she was creating a new way of seeing the difficult child she had been as a lovable, engaging one. Perhaps she even hoped to counter village gossip and give people (and possibly this new minister) a way of understanding her. Maud made a great many superficial alterations in the fictional transformation—Anne was given red hair to symbolize anarchy (and perhaps a Scots-Irish heritage), whereas Maud had brown hair. Anne came to an elderly, unmarried brother and sister, not to elderly grandparents; Anne was sent to the Cuthberts by mistake, whereas Maud stayed with her grandparents because her mother had died and her grandmother had a strong sense of duty.

Some of the more literal-minded people in the local community fell to looking for models as soon as Anne was published. A few saw elements of the youthful Maud in her creation. However, others claimed that they themselves were the model for lovable Anne. Ellen Macneill, a little orphan girl who had been adopted by Pierce Macneill and his wife, wanted a piece of Anne’s immortality and went to her grave claiming to be the model because she, too, was adopted. However, of this rumour, circulating during her lifetime, Maud wrote “The idea of getting a child from an orphan asylum was suggested to me years ago as a possible germ for a story by the fact that Pierce Macneill got a little girl from one.” But, she added in total exasperation on January 27, 1911: “There is no resemblance of any kind between Anne and Ellen Macneill who is one of the most hopelessly commonplace and uninteresting girls imaginable.”

Montgomery acknowledges that the prototype for Anne’s home with Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert was that of Maud’s Great-Uncle David Macneill, a “notoriously shy” man like Matthew. He lived with his Marilla-like sister, Margaret, and they raised the illegitimate daughter of their niece, Ada Macneill, a young schoolteacher who was considered by the community to have been “badly used.” This niece’s child, Myrtle Macneill, was a great comfort to them, and in 1905 she married Ernest Webb. Ernest and Myrtle inherited David and Margaret’s farm and raised their children there. It is now a provincial park, with the “Anne of Green Gables House” and the adjoining “Lovers’ Lane” open to the public. Myrtle Macneill Webb and Maud were good friends all their lives, but neither ever claimed that Myrtle was the model for Anne, despite the fact that she was raised in the house that was the model for “Green Gables” and she had done for her elderly surrogate parents what the fictional Anne did for the Cuthberts.

Maud would never admit that her heroine Anne was partly based on the child she herself had been, or at least one of the complex little girls who lay inside her. She rightly thought this was irrelevant and that people would use the idea to discredit her creativity. Over her lifetime, Maud created heroines very different from Anne, and yet each of them is in some way drawn out of the complex person that she was. Nothing made Maud angrier than hearing people say that they knew the originals of her characters, as if all she had to do was to transcribe them from life to make a book. She admitted that her characters had some resemblances to people in real life, but it was her imagination that made them live in fiction.

The book takes its power from Maud’s ability to word-paint landscapes, her skill at characterization, her understanding of how human beings interact in a small community, her trenchant social criticism, her sense of irony, and her sly erudition. Most of all, it is energized by her sense of humour. Readers laugh at the honesty of children, and the foolishness of adults. The book also captures with realism and nostalgia the tranquil nineteenth-century rural life that would disappear after World War I. Maud succeeded in capturing the culture, the history, and the times of her own people—and perhaps even much of the country of Canada—in her first book.

When the Muse descended on Maud Montgomery in that spring of 1905, coming in the company of the kindly Ewan Macdonald, a good-looking but unimaginative suitor, the effects flowed both ways. Ewan’s attentions energized Maud, but in turn her high spirits also stimulated Ewan, who was by nature a bit phlegmatic. For a man like Ewan, whose childhood had been poor and culturally deprived, whose education had been endless hard work, and whose emotional life had been flat, Maud must have seemed like a creature of fancy ready to fill the void. Maud was undeniably a lady in manners, deportment, and dress. He must have been flattered that she would consider a romance with him, a somewhat backward and stiff Highlander. That Ewan chose her over other aspiring women, given her rather plain looks and near spinsterdom, certainly delighted Maud. She used every charm she knew to win him when he came for the mail and she had a chance to talk to him, amusing him with her sparkling wit and stories about the community and her activities in it and the church. Later, in her journals, she would tell this story in a very different way, even razoring out and replacing the pages that originally described their courtship. She would make it sound as if Ewan sought her, and she merely accepted him because there was no better, her “Hobson’s Choice”—which was, of course, at least partly true.

Inspired and invigorated by finding love, Ewan became a very competent minister in Cavendish. He gave interesting sermons. People liked him. Maud gave him entertaining walks through the cemetery, narrating entertaining stories of the departed. He moved into action and mobilized the community to clean up the graveyard where a century’s collection of ancestors lay, including Maud’s mother and the rest of the family. (This beautifying project would be used later in Anne of Avonlea, where Anne encourages the “Avonlea improvement Society”—an idea generated by the popular press of that day, which was devoting much coverage to landscape and garden developments.) As his tenure wore on, and his courtship infused him with energy, his ambition surged. He began to think that he might become an even more successful minister if he took more training.

On October 12, 1906, Ewan drove Maud up to visit married friends, Will and Tillie Macneill Houston. On the way, he told her of his new plans: to leave Cavendish and take additional schooling at the famous Trinity College in Glasgow, Scotland, the most prestigious centre for studying Presbyterian theology in the world. Ewan’s father had fled Scotland to escape abject poverty; now Ewan would go back, triumphant in his calling as a minister of the Lord. Ewan was not wrong in thinking that a brilliant future might stretch before him. He was highly intelligent, and also had the instincts of a “good shepherd”: he was a gentle, well-meaning man. Shrewd and low-key, he was a skilled negotiator when tempers were ruffled, a necessary trait in a minister. He was also an effective organizer and mediator when he was in top form. Energized by romance, he showed great promise.

Ewan had been increasing his presence in the newspapers, preaching in important venues, as befitted ambitious young ministers. The Examiner stated that on September 5, 1906, he preached in the prestigious St. James Presbyterian Kirk in Charlottetown. By September 25, the paper announced that the Cavendish pulpit had become vacant. (He had already announced his intention of going to Scotland.) On October 7, Ewan again preached in St. James Church in the morning service and at Zion Church in the evening. He was preaching in Charlottetown’s most notable churches, in partnership with the distinguished Reverend T. F. Fullerton, a very prominent minister who frequently made the news. This burst of activity was spectacular for Ewan Macdonald after his competent but mediocre academic career. It appeared that his trajectory was that of a successful young minister ready to climb clerical ladders.

Seen in the context of his lifetime performance, his sudden show of activity suggests that he was riding an emotional high induced by his new romance. Had this been his standard and stable mode, his career would have been very different. But he would prove to be a man whose moods rose and sank, like the energies within him, and his performance was uneven.

As they drove along, Maud considered this good-natured man who was modest, yet dedicated and seemingly ambitious. She had read in the newspapers about his preaching in important churches. Anne of Green Gables had been completed some ten months earlier and was still making the rounds of publishers. Maud had no idea that it would become an international best-seller. But she did feel warm and hopeful in Ewan’s presence. As she and Ewan drove by horse and buggy that night, the weather was ominously dark and stormy. He proposed. Maud accepted. Both were very private people by nature, and they agreed to keep the engagement secret.

Ewan left to begin his advanced training in Glasgow around October 20. After she accepted Ewan, Maud wrote her cousin Ed Simpson a letter that made their breakup irrevocably final. Ewan promised to wait for Maud until she was “released” from her duties caring for her grandmother. Meanwhile, she was putting jewels in her own crown. Her grandmother was in relatively good health for her advanced age, and Maud could keep writing. It was a satisfactory arrangement for everyone—except, of course, Uncle John F. Macneill, who wanted the house.

Ewan had no sooner arrived in Scotland than he began to deflate. His departure from Cavendish had been quite a send-off: the community had put on a big celebration for their minister and given him a “purse” to help with his studies. He had crossed the ocean with great confidence, but as soon as he reached the University of Glasgow, he found himself in association and competition with brilliant, cultured, and highly articulate scholars from all over the globe. In Prince Edward Island his Highland roots and heavy Gaelic accent had been a slightly negative social marker among more sophisticated English-speaking Scottish immigrants, but in Glasgow, where the theology school was full of highly educated young Scots, Ewan found himself not only regarded as a backward Highlander but also as a provincial bumpkin from Canada. In Cavendish, Maud—immersed in the literary images of the Highlanders as brave and exotic—had romanticized his Highland roots, and this had bolstered his confidence. He got no such treatment in Scotland.67 Ewan’s name is written on the Glasgow entrance roll with a strong hand, but he soon began to collapse psychologically, skipping classes. He was out of his depth with the urbane and broadly educated students at the theology school. Moreover, he lacked the social graces that would have helped him feel comfortable with the others. This earnest young man soon began to feel inadequate. Within a month, his letters to Maud took on a morbid tone. He spoke only of discouragement.

Maud urged him to see a doctor, but he wrote back that a doctor couldn’t help him. (He was right—there was no medical treatment for depression in that period.) Perhaps he was counselled; perhaps some theologian told him that he was committing the “unpardonable sin” of doubt. At any rate, this idea took hold of his mind. In the theological terms of Presbyterians, the unpardonable sin was a failure to put all one’s trust in God. Believing himself shut out from complete faith, Ewan, now an engaged man, must have felt trapped in a future profession and a life. It is hard to fathom the depths to which his disturbed and disordered mind led him. He left Glasgow in the spring, sometime around March 4, 1907, when he sent a strange, blank, message-less postcard to Maud.68 There are no records in Glasgow of his academic performance at Trinity College beyond his matriculation signature, and no records to show he completed any work whatsoever.69

When Ewan went off to Scotland, his successor in the Cavendish church was another eligible bachelor, John Stirling. Stirling had a chiselled and ruggedly handsome face, a very sharp mind, and a refined manner. He came from a “good family” and was stable as a rock. All considered, with the benefit of hindsight, he was a much more promising man than Ewan.

Ewan returned from Scotland to Prince Edward Island at the end of March a sadly deflated man. After a lot of trouble in finding a charge, he accepted a less than desirable position in another small rural community, the remote Bloomfield-O’Leary parish, a very long way from Cavendish. Only rarely did he visit Maud. In his depressed state, he must have worried about his engagement and whether he himself was suitable for marriage. But he admired Maud too much to play the role of a cad and back out, as he had from his first engagement. Ewan was apparently doing satisfactorily in his new position when Anne of Green Gables was released and became an astonishing success.

Maud’s sudden fame may have inspired Ewan to attend the Presbyterian General Assembly off the Island, apparently looking for better opportunity on the mainland, as so many other ambitious young ministers did. For instance, the Reverend Edwin Smith, who had inducted Ewan as a minister in Cavendish, had already resigned (as recounted in the Patriot on May 1, 1909, p. 8), and had left the Island for greener pastures, and perhaps greater adventure, along with thousands of young people in other walks of life. According to the Charlottetown Patriot, in September 1909 Ewan resigned at Bloomfield, to the regret of his parishioners. He headed to a double-charge parish in Ontario, where he would live in Leaskdale, Ontario, patiently waiting for Maud to be free to marry.

The bitterness between Maud, her grandmother, and John F. Macneill’s family began to take its toll. Lucy Macneill came from an extremely long-lived family. Her sister Margaret lived to be nearly one hundred, and as a clan, the Woolners were normally very long in the land. But her son’s estrangement preyed on her mind, and, as she failed, Maud’s grandmother fell into periods of weeping and sadness.

There were problems at John F. Macneill’s house, too. His lovely daughter Kate had caught pneumonia and died in 1904 at the age of twenty. Maud had liked her. But Maud did not like the other daughters—Maud’s former playmate, Lucy, and Annie, the youngest. Lucy had incurred Maud’s anger for a perceived transgression, probably by tattling on Maud’s flirtatious behaviour, and Maud cut off all association with her, later reporting in her journals that Lucy had married beneath herself. As for Prescott, when his grandmother tartly told him he could wait to have her house after she died, he snapped, “You may live ten years yet.”70 Prescott developed health problems in 1906 and went into painful decline with tuberculosis of the spine, dying before his grandmother.

Maud’s use of language is deadly, and she wrote damning descriptions of most of her Uncle John’s children—Prescott, Frank, Lucy, and Annie. She was more kind to Ernest, the one son she liked, and the one who would indeed eventually inherit the farm. Of Lucy, she wrote:

Lucy was their oldest daughter … I kept on believing Lucy to be my true friend until I had unmistakable evidence of her falseness and deceit. When once my eyes were opened I investigated the matter thoroughly and a sickening tale of underhand malice and envy was revealed.… She had not stopped with distorting facts and insinuating malicious opinions. She had employed absolute falsehood.… Lucy was false to the core.71

Cavendish might have seemed idyllic, but it had the same passionate hatreds in it that fuelled wars on a national scale elsewhere. Until Maud’s journals were published, it was assumed that she knew only the rosy and romantic sides of life, but her devastating character sketches of people in the journals demonstrate otherwise.72

Despite the tensions with Uncle John’s family, Maud kept up her publishing efforts. She wrote and wrote, and read and read, while taking long walks to relieve her own anxieties. She suffered increasingly from headaches. It appears that Maud circulated Anne of Green Gables to publishers throughout 1906, as soon as she had it typed. She reported later that the novel was rejected by five publishers—in order, Bobbs-Merrill of Indianapolis; MacMillan of New York; Lothrop, Lea & Shephard of Boston; Henry Holt of New York; and L. C. Page Company of Boston—and then it lay in a hatbox for a considerable time before she reread it, liked it herself, and sent it out again to the L. C. Page Company of Boston.73 They wrote a letter accepting the novel on April 8, 1907, typed up a contract for the book by April 22, 1907, and Maud received it by post and signed it on May 2. In at least one speech during the 1930s, Maud said that Anne of Green Gables got special attention at the Page Company because a friend of hers from Summerside was a reader there and lobbied for the book.

Perhaps this history of the multiple rejections is accurate, perhaps not. The mail service was admittedly faster then. But if the handwritten manuscript was finished in January 1906, it had to be revised and typed, activities that normally took Maud several months; and if it was then sent to five publishers, one after the other, they would have had to return it almost without reading it, if we are to believe her story of its journeys—which in some tellings had the rejected manuscript reposing in her old hatbox until she had half forgotten it and found it during spring cleaning. Whatever the truth was, Maud was undeniably persistent in the face of manuscript rejection. As soon as any short story, poem, or other manuscript came back, she sent it out again.74

Maud expected Anne of Green Gables to be released in fall 1907, and wrote both of her correspondents, Ephraim Weber and George Boyd MacMillan, to that effect. Page apparently encountered delays with the internal artwork.75 In January 1908, she again wrote MacMillan that she expected it soon. On March 2, 1908, Maud wrote to Ephraim Weber that she had been busy for a month correcting the proofs of Anne of Green Gables, and it was to be out shortly (“around the 15th,” presumably of April). On April 5, 1908, she told Weber that she was expecting the novel any day, and that Page had sent advance publicity for it. On June 12, 1908, Anne of Green Gables was entered for copyright by L. C. Page under the number A-209449, and on June 20, her own copy arrived from Boston. By June 30, L. C. Page had announced that Anne was in a second printing. (The true first impression of the first edition of Anne of Green Gables bears an April 1908 date, and has two garbled sentences in it; Page soon corrected these errors and passed off the June impression as a first impression, first edition.)76 Reviews and letters about Anne began to pour in. Five months after the book was published, Maud reported having received sixty-six reviews.

Long before Anne was published, Maud was regularly written up in Island papers as a gifted poet and short-story writer. By mid-summer 1908 there were further write-ups about the success of Anne of Green Gables. The Examiner carried a long and laudatory review on July 10, 1908. The Patriot followed with a long, favourable review on July 13. On July 29, 1908, the Summerside Journal raved:

Anne of Green Gables, the latest literary effort of Miss L. M. Montgomery, of Cavendish, has made an instantaneous hit. The story throughout is most entertaining and the quaint and delicious sayings of Anne are bound to become household words. The book could only have been written by a woman of deep and wide sympathy. The humorous touches are most captivating. Beyond doubt, Anne of Green Gables is well worth reading. If you wish to see how really clever an Island girl can be just get this book. (p. 5)

Major papers in the United States also carried glowing reviews of the novel. The sales were phenomenal. Soon fans from all over the United States began to descend on Cavendish, wanting to meet Maud. The book was reprinted each month for the rest of the year, and almost as frequently the following year. By 1914, it had gone through thirty-eight impressions, and was still selling well.

When the book became an instant best-seller, Maud’s fragile temperament found sudden fame disorienting. To make matters worse, in July 1908 their house roof caught fire, a portentous event that devastated her nerves. By October she complained of feeling “deadly tired all the time.” Ten days later she complained about uncontrollable hyperactivity in her brain: “vexing thoughts began to swarm through it like teasing gnats.” She had bouts of unexplained weeping, and she began reliving every failure in her life (all symptoms of depression). Her behaviour upset her elderly grandmother even more.

Uncle Leander and his family were again at the family farm. He was a reader, and to his credit, he was impressed by Anne of Green Gables—and even more so by the way the book was selling. He began to treat Maud with new respect, deeming her intelligent enough to discuss men’s topics: politics, literature, history. Her Uncle John F. Macneill read the novel too; he is reported to have sneered that “anyone could have written it.”

Maud dedicated Anne of Green Gables to the memory of her father and mother. One of her greatest disappointments was that her late father would never know that she had “arrived.” Mary Ann McRae Montgomery did live to hear of the book’s phenomenal success. If she resented her stepdaughter’s fame, however, she did not have long to do so. The Charlottetown Examiner reported on April 19, 1909, that “Mrs. Mary Montgomery, who made a fortune in real estate speculation, died at Prince Albert, Sask.” She was forty-six. This was one death Maud did not lament.

Still, amid all this emotional upheaval, Maud was pushing herself to write. L. C. Page had set her to writing a sequel, Anne of Avonlea, a continuation of Anne’s story, even before Anne of Green Gables came out, and the new book was published in 1909 to immense sales. Page now urged her to get on with another book. She cobbled together Kilmeny of the Orchard for publication in 1910, basing it on material published earlier. At the end of 1909, when she was trying to write The Story Girl, she turned once again to herself as a partial model for her heroine, Sara Stanley.

Sara, the “Story Girl,” has an absent father and lives with relatives in Prince Edward Island. She is a local legend for her ability to tell spellbinding stories. Sara actually tells many of Maud’s own set-pieces. The cousins Sara lives with—Dan, Felicity, and Cecily—exhibit the happy qualities of the Campbell cousins, George, Clara, and Stella. Sara’s chief admirers are two young boys, relatives from Toronto. In the year before she married a minister, Maud had fun writing mock-sermons for the characters in her book to deliver, with farcical seriousness.

By January 1910, as she wrote The Story Girl, Maud spiralled towards a complete breakdown. “I thank God I do not come of a stock in which there is any tendency toward insanity,” she writes on February 7, 1910.77 Maud did not lose touch with reality (as in insanity), but her mood swings into depression were debilitating, and they disrupted her life. Maud describes in 1910 how she had a month of nervous prostration: “an utter breakdown of body, soul, and spirit.” The symptoms she describes include sleepless nights, and dreadful mental restlessness when she walked the floors with a fury, like a caged tiger. Talking to people coming to their house for their mail was a torture. She could not read or write or think. People noticed her distraught appearance.

I wanted to die and escape life! The thought of having to go on living was more than I could bear. I seemed to be possessed by a morbid dread of the future. No matter under what conditions I pictured myself I could only see myself suffering unbearably.… I had no hope. I could not realize any possible escape from suffering. It seemed to me that I must exist in that anguish forever. This is, I believe, a very common symptom of neurasthenia. (February 7, 1910).

She added that when she felt that way she could understand why people committed suicide to escape their feelings of torture. Her words are a classic description of a person’s feelings in a severe depression.

With her newly found fame, she now developed many worries about her fiancé: his sinking moods, his irregular performance, his awkwardness in polite society, his narrow range of knowledge, and, worse, his lack of intellectual curiosity for anything outside of his profession. The man who had been so solicitous before now seemed incapable of understanding or comforting her in any way. She told him of her despondent spirits, and he suggested that she give up her writing. He was unable to see that her writing was an integral part of her spirit and sense of self, and that it was, in fact, what sustained her. He simply thought it made her nervous.

Yet he was a very kind man, a trait that, having lived with her Grandfather Macneill, Maud valued highly. She had already backed out on Ed Simpson, and she didn’t want the reputation of being a “jilt.” If she rejected Ewan, who was willing to wait patiently for her until her grandmother died, she might not find someone else. And she did like Ewan a great deal. Maud had sought out Ewan’s love when her prospects were minimal, and she would have felt it dishonourable to back out as soon as she saw a chance for success and wealth.

In February 1910, Maud received a royalty cheque for $7,000. To put this in perspective, the prime minister of Canada made $14,500 in the same year. She had accepted Ewan when she thought he was headed towards a successful career in the ministry. Ewan’s brief blaze of glory had fizzled out after his return to the Island, but she was becoming a wealthy, famous woman. On November 19, 1910, for instance, the respected American periodical The Republic gave her a full page. The second paragraph read:

Less than three years ago the name of L. M. Montgomery was unknown to the reading public of the United States. Today she is in the forefront of our popular authors, not only in this country but in England, Canada and Australia. It is true, of course, that the author had a modest repute for excellent apprentice work … but doubtless those who knew her best little dreamed that her bud of promise was to have so early and splendid development. (p. 5)

Maud’s doubts about the man she was engaged to continued to grow. During her engagement, which they kept secret, she had watched, probably with frustration, as the very attractive John Stirling courted Margaret Ross of Stanley—a woman she believed to have been one of her early rivals for Ewan’s attention. In her journals Maud remained absolutely silent about this budding courtship. After the Stirlings were married in 1910, she stated with some tartness that he was one of those men that women marry for reasons other than love, and she unjustly labelled him as homely.78 John and Margaret Stirling made a happy marriage, remaining friends with Ewan and Maud throughout their lives. By 1911 Maud would look back on this earlier period and meditate on why we “seldom give our love to what is worthiest” (February 5, 1911).

Another friend was married that year. Nora Lefurgey, the vivacious teacher who had boarded with Maud and her grandmother, married Edmund Ernest Campbell, an Island son who was by then a very successful mining engineer in British Columbia. (He appears to have been one of Maud’s older students at Belmont.) This once again reminded her of her age.

Maud was now suffering from the excessive demands of her publisher, L. C. Page. He wanted more books as quickly as she could turn them out. She was expected to produce one book after another at breakneck speed. But at least the frantic pace of her writing kept her from thinking about other worries, like her future marriage to Ewan. She discovered that writing could often help her block out worries in her real life. It was a pleasant way to escape.

Kilmeny of the Orchard (1910), written quickly to satisfy Page, was the expansion of a story published between December 1908 and April 1909 as “Una of the Garden” in a Minnesota-based magazine called The Housekeeper. It tells the story of a young woman bearing a curse, who cannot speak until a suitor arrives and releases her voice. Similar to fairy tales like “The Sleeping Beauty,” it also parallels Maud’s own story: Ewan’s courtship allowed her to move beyond formulaic short stories and sentimental poems. Only then was she freed from a harsh grandfather’s curse. By freeing her from the fears of becoming a pitiful and voiceless old maid, Ewan’s love made her imagination soar and her pen sing. The style of Kilmeny is different from Maud’s other novels, and in style reflects her rereading of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories shortly before expanding “Una” into a novel.

Maud was not writing her novels in a vacuum. This was a period of great Canadian nationalism. An article in the Examiner notes that a host of other Canadian writers—Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, Wilfred Campbell, Frederick George Scott (father of Frank Scott, the famous jurist and poet), and Marshall Saunders were all born in 1861 and were now in their prime, creating an indigenous Canadian literature. Maud’s books were admired by the general public as part of this new burst of creativity. On one level, Anne of Green Gables tells the story of how an orphan found a happy home, but on another, it also captures the colonizing experience, especially the story of Canada’s settlement: an outsider (or immigrant) comes into a new territory, transforms it by naming it and changing it, makes it his or her own, and is rooted there—a classic pattern, but the difference was that this outsider was a little girl. Whatever the appeal, in 1910, new impressions of Anne of Green Gables continued to roll steadily off the Page presses; a British edition had been published and was already translated into Swedish and Dutch.

Maud’s reputation as a writer was spreading internationally. In the summer of 1910 the popularity of Anne carried Maud further into Canadian history, when she drew the admiration of the Governor General of Canada, Earl Grey, who made a trip to the Island especially to meet her.

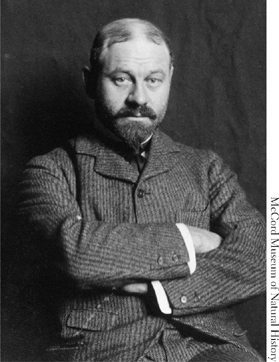

Sir Albert Henry George Grey (1851–1917) was Governor General of Canada from 1904 to 1911. During this period of extensive social change, he was an active reformer, supporter of Canadian culture, and traveller. Known also for his tireless promotion of unity within the Commonwealth, he sought to address as many “ordinary” Canadians as possible. Wilfrid Laurier (then prime minister) said Lord Grey gave “his whole heart, his whole soul, and his whole life to Canada.” Earl Grey was an articulate, gifted diplomat, without pretense or affectation.79 Respected throughout Canada, he took his duties seriously and was the first Governor General to travel to Hudson Bay and Newfoundland.

Towards the end of his office in Canada (the next Governor General was sworn in early the following year), at the age of fifty-nine, Earl Grey undertook an expedition from Manitoba to Hudson Bay and the Maritimes. The members of the expedition had been largely chosen by Grey himself, and included geologists, journalists, and constables of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. Several notable academics from McGill University included the expedition doctor, Dr. John McCrae (1872–1918), lecturer in Pathology and Medicine, and Professor John MacNaughton (1858–1943), a distinguished professor of Classics noted for his wide-ranging literary knowledge and his sociable personality. These men were colleagues of another prominent McGill scholar, PEI native Dr. Andrew Macphail (1864–1938), who was then one of the Island’s most famous native sons. He was not part of Earl Grey’s party.

The expedition was to evaluate the possibility of a rail link from the prairies to Hudson Bay. The expedition started at Norway House at the mouth of the Saskatchewan River; around August 10, 1910, they set off, travelling in twelve twenty-foot canoes, each paddled by two Cree guides, several hundred miles across north-eastern Manitoba. The group faced lengthy portages and rapids in their journey to York Factory, on Hudson Bay. Here they boarded the Earl Grey, a 250-foot steamship that had been built in 1909 for the Canadian government. This boat was an icebreaker as well as a passenger and freight ship that could cross the Northumberland Strait, from the mainland to PEI, in winter. The steamship, with a specially appointed suite for the Governor General, took them through the Hudson Strait, around northern Quebec and Labrador, to the Maritimes. They kept in touch with land through marine dispatch.

On July 16, 1910, when first hearing of this planned venture from his colleagues, Dr. Andrew Macphail wrote to the Honourable Earl Grey, graciously inviting him to visit the Macphail ancestral homestead in Prince Edward Island on the last leg of the expedition. Earl Grey wrote him on July 23, 1910, to say that if they did have time to visit PEI, it would be,

for the express purpose of offering the tribute of my homage to Miss Montgomery. I shd. like to thank her for Anne of Green Gables. I have not enjoyed a book more for a long time than I did hers—a Classic. I recommended all my friends in England to read it—but they nearly all were before me. They had read the book before I had!80

By late August it was clear that the expedition had made good time, and the group could dock in PEI so that the Governor General of Canada, Earl Grey, could meet Maud.

Dr. Andrew Macphail is an interesting character here.81 An important figure in PEI history, he was a high-profile academic at McGill. He was also devoted to improving the standard of living on Prince Edward Island, where he lived part of every year at the Macphail homestead. In 1907, Dr. Macphail was appointed McGill’s first professor of the History of Medicine, and in 1911, he founded the Canadian Medical Association Journal. A Renaissance man in the fullest sense, he was also a man of letters, founding and editing for over a decade The University Magazine, which discussed literature, philosophy, politics, industry, science, and art. He also published several books on a range of subjects. (His 1939 semi-autobiographical novel, The Master’s Wife, is his best-known work today.) His scientific study of agriculture on his farm in Prince Edward Island led him to scientific innovations that started the seed potato industry on PEI. At age fifty, he would enlist in World War I, in spite of having been blinded in one eye, and serve on the front for nearly two years in the medical corps where he helped found the Canadian Field Ambulance Service to provide care for injured soldiers.

If Maud knew anything about this expedition, she had no inkling that it was being routed through Prince Edward Island strictly so that Canada’s beloved Governor General could meet her. Because of Macphail’s standing on the Island, the newspaper depicted it as a visit to Dr. Andrew Macphail’s impressive homestead.

On September 6 Maud was absolutely astonished to receive an invitation from Lieutenant-Governor Benjamin Rogers, saying “His Excellency Earl Grey will be in C’town on Sept. 13th and wishes to meet you.” The same post brought a letter from Dr. Macphail telling her that he would be entertaining the Earl’s party at his home in Orwell, and she was invited to come. Maud wrote in her journal entry of September 7, 1910, that it “speaks something for ‘Anne’ … that she should have been sufficiently delightful to a busy statesman to cause him to single her out in his full life and inspire him with a wish to meet her creator.”

With only seven days’ notice between the telegram and the event, Maud was thrown into a panic over what to wear. There were no clothes in her wardrobe appropriate for a viceregal occasion. She hastily engaged a local dressmaker (Bertie Hillman) and hurried to Charlottetown, where she bought a length of silk in one of her favourite colours, brown.

She also bought and read a book published early that year by Dr. Andrew Macphail, Essays in Fallacy (1910). Dr. Macphail’s status on the Island ensured that this book had received front page attention in the Examiner of September 10, 1909, with the headline: “Dr. Andrew McPhail’s Essays Praised in England: Contemporary Review Recognizes Ability of P.E. Island’s Gifted Son.”82 The article goes on to state that “Dr. Andrew MacPhail’s essays on imperial policies and the future of Canada will materially affect the attitude of responsible thinkers throughout the Empire and in the United States …”

Macphail was an outspoken social critic and had a great deal to say, among other topics, about women. One essay in his 1910 book, titled “The American Woman,” urges women to stop asserting their rights and instead remain submissive, quiet, long-suffering, and attentive to their husbands. Another, “The Psychology of the Suffragette,” condemns women agitating for women’s voting rights. (Island women would not obtain the right to vote until 1922.) Such behaviour “makes a man impatient and finally contemptuous of all femininity,” wrote Macphail.83 Macphail also criticized the proliferation of young female teachers, arguing that young males needed male models for their teachers. The increasing presence of women in schools, he argued, was undermining educational standards. Maud wrote respectfully in her journal that his book was “stimulating” with much “unpleasant truth” in it, but she goes no further, perhaps intimidated by the Examiner’s comment that “Dr. MacPhail’s incisive prose style reveals a mind of extreme ability stored with the best literature and trained by direct observation.”84

Maud must have wondered nervously before she went to the Macphail homestead if the much venerated Dr. Macphail had indeed read Anne of Green Gables, which had been published two years earlier. If he had (as was likely), he would have seen that she had depicted the male teacher, Mr. Phillips, as a fool. By contrast, Anne’s other teacher, Miss Stacy, based on her own Miss Gordon, was a model for all young women to follow: this “lady teacher” inspired her students, touching their lives. At Dalhousie, Maud had published a serious essay on the importance of education for women. Still, she was well aware that her Grandfather Macneill and others like him (including the venerated Andrew Macphail) still disapproved of women teachers. Maud was not one to attack public opinion stridently—instead, she used humour in her novels, feeling it was more effective for ridiculing outdated ideas.85

Maud attended the events in her new brown silk dress, hastily made for the occasion. The Earl Grey dropped anchor at 3:00 p.m. on September 13, in Charlottetown, off the Marine Wharf. Lieutenant-Governor Rogers went on board and brought the party ashore. At 4:00 p.m. they took a train to Uigg, where the guests enjoyed a reception and repast at the Macphail homestead in Orwell. This party included, among others, Lord and Lady Grey, Lord Lanesborough, Lord Percy, Dr. John McCrae, Professor John MacNaughton, Lieutenant-Governor and Mrs. Rogers, the Honourable John Agnew, and “Miss Maud Montgomery.” Later that evening, the group returned to Charlottetown by special train, returning after 10:00 p.m. The next day, they dined on board the Earl Grey. After the dinner, the boat sailed for Pictou, where it would anchor again, and Earl Grey and his party returned to Ottawa by rail.86

Maud’s description of the reception at the Macphail homestead in her journals treats only on comic aspects of the encounter. She recalls how she and Earl Grey strolled out to the orchard to talk in private about her writing. There, they sat on the steps of the outhouse, which had been fixed up with dainty curtains for the occasion. She speculates that Earl Grey was perhaps unaware of the purpose of the outside toilet when he preferred its steps to the Macphail house for unaffected, unpretentious “real” talk.

Strangely, Maud wrote little about the people she met at this reception. Dr. John McCrae was the official physician for the expedition. Born and raised in Guelph, Ontario, he would later make his name known internationally by writing “In Flanders Fields,” the most famous war poem to come out of World War I. At the time of the Earl Grey reception, Dr. McCrae was a thirty-seven-year-old bachelor, two years older than Maud, sharing her birthday of November 30. Maud does not mention meeting this handsome, charming, and distinguished fellow Scottish-Canadian, although she certainly would have been presented to him. After his death in 1918, Maud paid tribute to him by using his poem as the model for Walter Blythe’s famous poem in Rilla of Ingleside. Anne’s son, Walter Blythe, shares McCrae’s literary sensitivity, modesty, idealism, and devotion to duty—all traits and values Maud admired.

Maud did comment on Dr. Andrew Macphail, a man so venerated on the Island that the Island papers carried accounts of his every publication, of every movement he made either on or off the Island, and every off-Island guest who came to his homestead. (For instance, at one point an Island paper announced that Dr. Macphail’s friend, Rudyard Kipling, would be visiting him on the Island the following year, a visit that seems not to have taken place.) Of Macphail, Maud wrote, “the doctor himself is a strange-looking man—[he] looks like a foreigner” (September 16, 1910). Macphail was very high-minded, noted for his principles, his strong views, and his seriousness, and Maud’s characterizing him as a “foreigner” was certainly not a compliment. In a xenophobic era (and Island) that even feared little orphan children like “Anne,” this gratuitous tag in her private journal was in fact little less than insulting.87

It is no surprise that the visit of the revered Earl Grey was headline news in the Island papers. The Charlottetown Examiner announced on September 14, 1910: “EARL GREY, GOVERNOR GENERAL NOW VISITING PEI.” Maud is mentioned only in the third paragraph. Similarly, the Patriot ran several articles before the visit, and the front page on September 14, 1910, charted the “movements of the vice regal party,” mentioning only in the second paragraph that “Miss Lucy Maud Montgomery” was one of the guests. Maud recalls how many of the people in Cavendish were stunned to hear about her invitation to meet Earl Grey. (Her dearest relatives—her Aunt Mary Lawson and cousins Bertie McIntyre and Stella Campbell—were thrilled by the honour.) Although Islanders often saw her name in the newspapers for poetry, and she had received attention for the success of Anne of Green Gables, she still had a small profile on the Island compared to a man like Dr. Andrew Macphail. The “Earl Grey affair” raised Maud’s status throughout the Island.88

Later, the Patriot of October 10, 1911, ran an account of a sketch in another magazine in which Maud informed a journalist that Earl Grey told her he “had determined when he came to the Island to see at least two persons, the authoress of ‘Anne of Green Gables,’ and Dr. Andrew Macphail and his potatoes.” She must have had a twinkle in her eye when she repeated this characterization by Earl Grey, linking her name to books and Macphail’s to potatoes. This article also attributes to Earl Grey the opinion that “Canadians were a very fine people, but one thing he had against them was that they were so apt not to appreciate the work of one of their own until it had been admired by others.”89

Maud and Earl Grey continued to correspond for several months, improving her mood and self-confidence considerably. He had asked for copies of her books and she sent them. He advised her against writing sequels, saying they were “never as good.” He sent her the current Bookman so she could see its portrait of Mrs. Gaskell, the English writer, whom both of them admired. He wrote:

Like Mrs. Gaskell you possess what The Bookman describes as the three fairy gifts of the English Novelists, viz: knowledge of human Nature, Imagination, a natural love for a good story, and a pretty style.

Then he adds, with playful seriousness, in this letter of September 20, 1910:

I see I have endowed you with 4 as against The Bookman’s 3 gifts. I must consult The Bookman again to see where we differ. At any rate this triple or still more this quadruple possession gives you great power, and consequently the burden of a proportionate responsibility.

He cautions her to “withstand the temptations of publishers who will want you to sell your unborn soul for their advantage” and advises her,

to keep your undeveloped influence as a sacred lamp, which shall be a light to yourself, the Island, Canada, the Empire and to the English-speaking peoples of the world. Young as you are, you have already been able to make the name of Prince Edward Island known wherever the English tongue is spoken. That is much: but having got so far, that is only a stepping stone to more important accomplishments.

He forecasts in his letter of September 20, 1910, that if she can only be “sufficiently inspired” from her “sea-girt nest in Prince Edward Island” she will “touch the heart and fire the imagination of the whole Empire.”

Maud replied to Earl Grey on September 26, with the characteristic modesty of a woman writer who could not admit to ambition, since women were supposed to have none. Part of her long letter reads:

I do not think I am a very ambitious woman. I do not care much for fame; and from its attendant shadow of publicity I shrink. But I do wish to give back to the world something of the joy and pleasure I have received from its heritage of “the thought of thinking souls” of the past. I think I know my limitations. I am not a genius. I shall never write a great book. But I hope to write a few good ones … (September 26, 1910, Public Archives of Canada, Earl Grey papers)

Earl Grey’s influence, or attempted influence, did not end there. On September 27 he wrote to Professor John MacNaughton at McGill suggesting that he write an article on “Miss Montgomery.” MacNaughton was a highly respected scholar, and when on the Island, he had expressed admiration for Maud’s literary skills.90 Grey wrote:

I wish you would write a review of Miss Montgomery’s novels for the “University Magazine,” if MacPhail [its editor] approves; but being an Islander I expect he will reserve that appreciation for his own pen …

Earl Grey promised to send Kilmeny, The Story Girl, and Maud’s poems to MacNaughton, adding:

You can introduce into your review, if you like, the incident at MacPhail’s Farm, where I pointed out that her open volume, on which young MacPhail’s 3 candles were resting, evidently had formed the basis of all his illumination. As you pointed out at the Consolidated School, her candle is going to illuminate the Island in every land where the English language is spoken. (Letter of September 27, 1910)91

MacNaughton replied promptly:

Your Excellency, I am very much indebted to you for the kind and gracious letter which I got yesterday. I saw Dr. Macphail last night and found him not as enthusiastic about Miss Montgomery’s work as we are but perfectly willing to let me write about it … (Letter of September 29, 1910)

We can only speculate about Macphail’s private response to Earl Grey’s adulation of Maud. Maud Montgomery and Andrew Macphail were as different as could be in personality and style. Was his pride piqued to hear Earl Grey suggest that Maud’s humorous novels were the basis of so much international “illumination,” a term that had been used in reviews to describe his own collections of thoughtful and serious essays?

Professor MacNaughton never wrote the article on Maud, whether because of Macphail’s disapproval or because of other demands on his time.92 Earl Grey was deeply interested in the fledgling Canadian cultural and literary world, and sympathetic to it. He would have known that a serious article by a major male scholar at McGill would have influenced the course of Maud’s career. Sensing her talent, he wanted to encourage it, providing her with the same kinds of puffs and praise that academic and professional men regularly gave to each other.93

Whatever the underlying politics of Earl Grey’s visit to the Island, and its aftermath, his admiration of Maud was a significant boost to her self-respect, raising her confidence at a low point in her life. However, writing a best-seller had not wiped out the damage from her childhood—her underlying sense that she was of little importance.

Only a month later in 1910, Maud was entertained by another prominent man, her publisher, Lewis Coues Page, of Boston. Page had good reason to invite Maud to visit him, his firm, and his impressive residence: her books were earning him a fortune. Page was a shrewd businessman, exactly the kind of publisher Earl Grey had had in mind in his warnings to Maud. The first contract (for Anne of Green Gables) had specified that Maud’s royalty would be 10 percent of the wholesale price of her books, rather than the more customary 10 percent of the retail price. This was her first novel, and she had no experience with book contracts and publishers.94 Like many new authors, she was so keen to be published that she took what was offered, assuming that as standard.

The further “binding clause” in the Anne of Green Gables contract specified that Maud had to give subsequent books to Page at the same rate for a specified period. It was not unusual for publishers to put binding clauses into their contracts, but to insist her forthcoming titles remain at the same rate was both cunning and unfair. A decent publisher would have given her 10 percent of the retail price, or more after she established herself as a successful author. A writer of continuous “best-sellers” might have hoped for an escalating percent of the retail price. He repeated the same clause in contracts for her next two books, Anne of Avonlea and Kilmeny of the Orchard. By 1910, Maud had learned that she was being shortchanged, and she wrote to him that she did not intend to sign that binding clause in subsequent contracts.

Agents and writers’ unions were fairly new phenomena at that time, so writers were at the mercy of the publishers. Women writers were especially exploited, as they had little experience at defending their rights in public or in initiating legal challenges. Page knew his advantages and pressed them. He also knew that women fell readily for his personal charm.

Page had two motives for inviting Maud to Boston. The first was to show his quaint little Canadian country lass to the curious Boston press, introduce her to Boston socialites, and thus stoke the market for her books with the reading public. The second was to persuade her to sign another contract extending the same binding clause to all books written in the next five years.

Maud had been fighting depression in the autumn of 1910. While meeting Earl Grey in mid-September had been a boost, it was not long before her mood started sinking again. Also, being thrust into the public eye had been disorienting. The invitation to visit Page came on October 13. At first she decided against the visit, and started a letter to Page explaining that she could not come, but then, suddenly, she recalled experiencing a sudden “inrush of energy and determination”; she “felt strangely blithe and joyous” as she had “not felt for years,” and she decided to go after all.

She travelled to Boston by train, accompanied by her cousin Stella Campbell. Both women spent their first day, a Sunday, with a cousin, George Ritchie, and his family. On Monday a taxi arrived to take Maud, Stella, and Lucy Ritchie to Page’s office on Beacon Street, where Maud finally met Lewis Page and his brother, George Page, and others in the firm. The rest of the day Maud spent shopping in the Boston department stores in order to have a suitable wardrobe for the rest of the visit. She had never seen anything like the stores in Boston. She bought herself a brown broadcloth suit, as well as a beautiful hand-embroidered pink silk afternoon dress costing eighty dollars (an amount that would have been approximately half of her year’s teaching salary in Bideford).

She was to be a personal guest of Lewis Page and his wife, Mildred, at “Page Court,” their elegant home at 67 Powell Street in Brookline, Massachusetts. On arrival, she was met by a maid who took her to a guest room. Seeing herself in the bedroom in a full-length mirror was a new experience. She described the visit in her journal entry of November 29, 1910. As she descended the stairs, the “polished hardwood staircase” was “lined with a collection of prints” of the Page ancestors—a very impressive group. She was ushered into the library for tea with Mildred Page, who was “fairly good-looking but utterly without ‘charm.’ “The library was the most elegant room she had ever seen: built-in shelves filled with expensive books, large casement windows, and comfortable easy chairs before a large fireplace. On the wall hung the original painting of the cover of Anne of Green Gables. Later she enjoyed a formal dinner with the Pages and other houseguests, a couple on their honeymoon with connections to Italian royalty, the Boston banking world, and an American senator.

Of Page himself, Maud wrote:

Lewis Page is a man of about forty and is, to be frank, one of the most fascinating men I have ever met. He is handsome, has a most distinguished appearance and a charming manner—easy, polished, patrician. He has green eyes, long curling lashes and a delightful voice. He belongs to a fine old family and has generations of birth and breeding behind him—combined with all the advantages of wealth. The result is one of those personalities which must be “born” and can never be achieved. (November 29, 1910)

Most women reacted to Page in this way: he was tall, urbane, elegant, and charming. According to Page’s literary executor and cousin, the late W. Pete Coues, when Page entered a room, he attracted everyone’s attention with his commanding presence and distinguished carriage. An “outstandingly handsome man,” he was always “well-dressed and avant-garde.” Still athletic, he exuded masculinity in a way that disarmed women. He was five years older than Maud. He had always moved in the top echelons of Boston society and was the embodiment of the aristocrats Maud had read about in British novels.

The entire setting was intoxicating. Maud asked if she might take photographs of the Page home, both inside and out. Her grandfather, Senator Montgomery, had owned a nice house, but it was nothing like “Page Court,” the North American equivalent of the splendid homes on great country estates of British royalty.

During her visit, Page treated Maud like royalty, with luncheons and receptions arranged in her honour, side trips to historic sites and museum tours, as well as book-signings. Boston journalists were invited to “Page Court” to interview Maud, and they wrote about her: “As the young author entered the Pages’ beautiful library one thought came to us: ‘It is a repetition of history: Charlotte Brontë coming up to London.’ By-and-by we found we were not alone in the idea.” One journalist, writing in The Republic, described Maud as,

… short and slight, indeed of a form almost childishly small, though graceful and symmetrical. She has an oval face, with delicate aquiline features, bluish-grey eyes and an abundance of dark brown hair. Her pretty pink evening gown somewhat accentuated her frail and youthful aspect.

… For all of her gentleness and marked femininity of aspect and sympathies, she impressed the writer as of a determined character, with positive convictions on the advantage of the secluded country life with its opportunities for long reflection and earnest study.… Bostonians are charmed with her unique personality no less than with her books; but for ourselves we should be more interested to know just how the pageant of our strenuous life has recast itself on the mind of this quiet but observant and philosophical sojourner.95

Page, who was skilled at fanning public interest, made sure that this magazine (and others) featured the “best-selling” status of Anne of Green Gables in the Boston media:

Every discerning critic realised that in “Anne” a new and original character had come into the world of fiction and would abide until she had become a classic. In these fickle days when of making books there is literally no end, six months is a long popularity for a book, but after over two years “Anne of Green Gables,” now in its twenty-fifth large edition, is selling as well as ever, and is known in every land of English speech.

By the time she left Boston, however, Maud was less impressed with Page. She had written him before she went down that she was unwilling to sign another contract with the “binding clause” in it. She knew that he was reaping huge profits from her books, and also that he should give her better terms. But Page was shrewd, intuitive, and used to getting his way with women—whether they were authors, employees, maids, waitresses, or clerks.

Towards the end of Maud’s visit, Page asked her if he could bring home the next contract for her to sign. She agreed, assuming that he would have omitted the offending binding clause. On her final night, however, he came up to her bedroom with the contract. It would have been appropriate for him to ask her down to the library to read and sign the contract; but, cunning man that he was, he no doubt felt that an awed, repressed “spinster” of thirty-six, who was out of her element in his house and under the spell of his charm, would feel her most vulnerable in the intimacy of her bedroom. Maud was distressed to find the offending clause still in the contract. She wrote later:

Did Mr. Page reason thus:—“She has been my guest; I have been exceedingly good and agreeable to her; in my house and as my guest she won’t want to start a discussion which might end in a wrangle and stiffness; so she will sign it without question.”

If he did, I justified his craft for I decided to sign it for just those reasons. (November 29, 1910)

In forcing Maud’s hand, Page got his way in the short term. But he also made a fatal mistake. Maud would never trust him again. With her innate sense of morality, she felt that she had been cheapened by acquiescing to a business deal that diminished her. She would soon be hearing alarming tales from other people who dealt with Page and considered him unscrupulous.

Yet, the trip had been exhilarating. She had spent wildly for some expensive clothes. She had drunk “Chateau Yquem” for the first time and loved it. She had taken wonderful trips to historical sites. Boston was a place of immense culture and elegant living, and she envied the life of the elite. She began to dream of a new life—if her income and celebrity continued, and if Ewan became a successful minister, eventually moving to a large urban centre where she could be part of a literary world.

Back on the Island, it was more apparent than ever that life was changing. The population demographics of Prince Edward Island were undergoing a significant transformation: the well-educated younger generation, finding more opportunity elsewhere, had for some time been leaving for mainland Canada or the United States.96

Maud’s father’s generation had left the Island in droves when the railways opened up the Canadian west, and the exodus from the overpopulated Island was continuing. In a speech reported in the Examiner on February 16, 1911, Andrew Macphail claimed that in just one single day in September 1908 exactly 5 percent of the adult male population had left the Island. Although this is almost certainly an exaggeration, the Island’s population did decline significantly in the four decades following 1891. By 1910, the desire to leave the Island for opportunity elsewhere was a contagious fever raging through the younger generation. The Island had seemed an idyllic, changeless place in Maud’s childhood, but now it felt increasingly like an isolated backwater.

As previously mentioned, after Ewan returned from his studies in Scotland in spring 1907, he had trouble obtaining a good parish on the Island. Many other ministers were leaving for the mainland, some merely to find work and others to find new experiences. One who had taken this step was the very successful Reverend Edwin Smith, who had trained at Pine Hill Seminary like Ewan, and had inducted Ewan at Cavendish. Smith had resigned at Cardigan, PEI, in May 1909. In September 1909, Ewan resigned at Bloomfield and obtained a parish in Ontario; in so doing, he positioned himself with the other adventurous go-getters on the move.

Island newspapers lamented that the best and brightest young Islanders were departing for greater opportunity elsewhere. Maud had been worried about Ewan’s fizzle in Scotland, but she took some heart when he showed this initiative. The town Ewan was moving to—Leaskdale, Ontario—was close to Toronto. Maud had already met journalists from Toronto: Marjory MacMurchy and Florence Livesay (wife of the distinguished journalist J. F. B. Livesay, and mother of the future poet Dorothy Livesay). They had sought her out in PEI, and she had enjoyed the contact. Her taste of the culture in the big city of Boston had enlarged her “scope for imagination.”

Maud loved her Island, but she knew that she would not be able to stay on the Macneill homestead when her grandmother passed on. Like her Uncle Leander, Andrew Macphail, and her cousin Murray, she could return to the Island for summer vacations. The Island papers treated her with respect, but they were prouder still of Islanders who drew attention on the world stage—especially if they always attributed their success to their Island beginnings, as Andrew Macphail had done. If you were born on the Island and moved away, you were always an “Islander.” Maud’s successful cousin, Murray Macneill, was actually raised on the mainland, but he regularly visited the Island with his parents as he grew up, and was always considered to be an “Islander” by virtue of lineage. Moving away did not mean loss of your Island heritage and identity. Ewan’s move excited Maud.