Maud’s focus was not only on the war abroad. There was also a war brewing in her professional life. A royalty report from her publisher, L. C. Page, in February 1916 was worrisome: he claimed that the sales of Anne of the Island amounted to only 3,200 copies. This was considerably fewer than she had expected, and she suspected Page of dishonest accounting.

Maud had initially offered The Watchman to Page, but Page had brusquely refused it, on the grounds that poetry did not make money. She was furious: he had already made a fortune on her novels, and this book was especially important to her.

By now, Maud had been chafing for several years at Page’s insistence on the initial “binding clause” that held her later books to the same paltry royalty rate of Anne of Green Gables. Her contract to give Page subsequent books had run out with the publication of Anne of the Island in 1915. She could now leave Page with good conscience, and his insensitive refusal of The Watchman was the last straw.

On her literary jaunts in Toronto, she had met John McClelland, of McClelland, Goodchild, and Stewart (soon to be McClelland and Stewart), and she had engaged the company to publish her poems. Page’s refusal to publish The Watchman would prove to be a costly mistake for him. John McClelland’s decision to take on a book of poetry that would itself make no money was undoubtedly the best business decision he ever made. With it, he acquired “L. M. Montgomery” as his author, and the sales of her best-selling books helped his firm become Canada’s pre-eminent publisher of Canadian authors for the rest of the twentieth century.

Maud promised McClelland her next novel, Anne’s House of Dreams. On his advice, she joined the Authors’ League of America, an association that would be able to offer her legal help if her disagreements with Page ever went to court. Lewis Page was well known as a man who used intimidation to get his way—first angry threats, then lawsuits.

In February 1917, while she was reading the proofs for House of Dreams, Maud received a threatening letter from Page: he was furious that she was moving to another publisher, and he had found a pretext to withhold her royalties. In May 1917 she engaged a lawyer through the Authors’ League to deal with Page.

Anne’s House of Dreams is a story of pre-war Prince Edward Island, but it introduces events and emotions more troubling than ever before. In it, Anne’s first child dies at birth, an experience Maud knew all too well. Anne becomes pregnant again, and another baby is born. The “house of dreams” now has a dream fulfilled. At first, it appears to be a book about happiness in marriage—Anne’s and Gilbert’s—and fulfillment in child-bearing. On the surface, the book reinforces romantic attitudes about marriage. Yet Gilbert is always out of sight, and Anne finds a community of other friends.

The book introduces several new characters: a handsome young journalist with the sophisticated authorial skills to turn traditional Island tales into a sellable work; and Captain Jim, a retired sea captain, whose best stories, Maud wrote in her journals, came from her own grandfather. And there are new women characters, as well: Susan Baker, a funny, warm-hearted helper and friend, the housekeeper that Montgomery must have dreamed of; and Miss Cornelia, sharp-tongued gossip and “man-hater,” able to vent some of Maud’s own less “respectable” feelings. The novel provides another glimpse into the comfort that friendship and shared storytelling can provide.

The real focus of the book, however, is the mysterious woman whom Anne sees in the distance one day. She is beautiful, closed off, and tragic. Her name is Leslie Moore—the initials “L.M.” are Maud’s own, of course. Leslie Moore is tragically yoked to a man who is, literally, an emotional zombie, one of the walking dead. Leslie was forced to marry this man, Dick Moore, by her controlling mother, even though she did not love him. On one of his trips abroad, he had a debilitating accident and was shipped back, a shell of a man. Leslie is held in her marriage by a sense of obligation. Inside the lonely and depressed Leslie—who must be a wife to this dead-in-life man—lies a smouldering vitality and near-explosive frustration.

This ill-advised marriage is a startling new theme for Maud, one undoubtedly drawn from her anxiety about her own marriage. Dick is human only biologically. He is unable to connect emotionally to others. The tragic marriage of Leslie and Dick Moore is ended by medical intervention. When his human side and memory return after an operation, Leslie finds that Dick is not her husband after all. He is simply a cousin of her husband, a man who bears a remarkable resemblance to Dick—and Dick, it turns out, is long dead. The repressed, frustrated Leslie is suddenly free to marry again.23

By then Maud was no longer living with the man she thought she had married. Ewan’s capacity for pleasure seemed somehow crippled: he did not take the kind of joy that she did in nature or in other kinds of beauty. He had been lively in her presence when they were courting and during the early part of their marriage, but increasingly he exhibited a curious emotional flatness in his relationship to the world around him that she could not understand. He fell into abstracted moods, was subdued and lethargic. He looked sad. In this era, husbands and wives often lived in different intellectual spheres, but Maud had hoped for a marriage where there would be at least some companionship.

In the novel, an outsider falls in love with the emotionally starved Leslie’s new lover. This young man is a talented journalist named Owen Ford. He speedily wins the repressed heart of “L.M.” The beautiful Leslie Moore eventually moves into a marriage as happy as that of Anne and Gilbert, after being freed from her husband.

Perhaps Maud remembered one of the ministers at Ewan’s induction, Edwin Smith. Smith was very active as a journalist, and he could easily have provided a partial model for Owen Ford. Edwin Smith had the same kind of easy charm as Owen, the same interest in many things, including a notorious fascination with boats and sailing, and the storytelling ability of Captain Jim. After his war service, he would be known as “Captain Smith.”

Anne’s House of Dreams was dedicated to Laura Pritchard Agnew, Maud’s childhood friend in Prince Albert, “In Memory of the Olden Time”—a puzzling dedication. Laura married her childhood sweetheart, a man who adored her, and she apparently had a happy marriage, at least to Maud’s eyes. But Maud privately thought Laura’s husband a dull, insipid man—nothing quite as bad as Dick Moore, but still not worthy of the lively Laura, except in his devotion to her. Perhaps this novel was dedicated to Laura for no particular reason other than to deflect attention away from its real subject: the pain of Maud’s own emotional loneliness in a marriage.

By 1916, Ewan had become largely absent in his wife’s diary. He was rarely mentioned in the first half of 1916, for instance, unless he was ill. In this year, he was sometimes away at recruiting meetings (December 10, 1916; January 5, 1917), and these had begun to depress him. Maud’s diary does not record much joy in her own relationship with Ewan, an absence made all the more noticeable because she does write extensively about her love of her children. In fact, it could be argued that her journal was beginning to substitute for the emotional closeness that might be found in a satisfying marriage. Maud writes on March 16, 1916: “How I love my old journal and what a part of my life it has become. It satisfies some need in my nature. It seems like a personal confidant …”

It is a curious fact that when the Polish army chose one of Maud’s books to issue to their fighting troops in World War II, they chose Anne’s House of Dreams. It was supposed to inspire the young men to fight for the ideal of happy married love, a peaceful hearth, and a safe home. The book implies such pleasures. But its real power comes from Maud’s powerful depiction of the longing for that love and home.

Only Maud’s storytelling ability makes this book compelling. The novel’s plot is as far-fetched as a Gothic romance. Its happy ending strains credulity. But the novel works as a strangely moving read because Montgomery has reached inside herself and externalized her feelings, showing the misery of a lonely soul, and the hope for a better future.

Less than three weeks after finishing Anne’s House of Dreams Maud began writing a version of her life called “The Story of My Career” for publication in Everywoman’s World, a popular magazine for women. Nothing could present a more different view of her life from the depths sounded in Anne’s House of Dreams. Now available as The Alpine Path (Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1975), it provides a sanitized account of her childhood—retelling many anecdotes from her diaries—and ends with her move to Leaskdale, presumably to be forever happy as the contented wife of a clergyman. However, her journals give a different narrative:

I was never in love with Ewan—never have been in love with him. But I was—have been—and am, very fond of him. He came into my life at its darkest hour when I was utterly lonely and discouraged with no prospects of any kind, and no real friends near me. At first I thought I could never care at all for his type of man; but I did; and I married him—and I have not regretted that I did so.… But I write not of these things for the Editor of Everywoman’s. My grandchildren may include what they like in my biography. But while I live these things are arcana. (January 5, 1917)

In the “Story” of her career, she tells how she always wanted to be a writer, and focuses on the perseverance that allowed her to climb “the Alpine Path” to success and fame. The touch is so light in this version of her life that the public believed that she had lived an uneventful and wholly satisfying life until her personal journals began to be published in 1985.

Memories about the family dynamics in the Leaskdale manse were few by the 1980s, but the succession of maids employed by Maud from 1912 onwards did have some superficial observations.24 Maud treated her maids as members of the family, and they all ate meals together. All the maids liked Ewan very much, although many viewed him as rather “stodgy.” Some commented on his inactive nature and his “fleshiness,” but they thought him very fond of his wife (and her very fond of him!). To them, he was a “typical man,” though unnaturally maladapted to the tasks most men should have been doing in the house. However, the Leaskdale maids all regarded the Macdonald family as a very normal and typical family, with the standard family “devotions” after breakfast (“standard Presbyterian fare” at the time, said one maid). These consisted of Ewan reading a passage from the Bible followed by prayers, the entire ritual lasting from five to ten minutes. Maud they remembered for her unfailing sense of humour and companionable nature.

After Maud received a cheque for $2,500 (half her advance) from the Frederick Stokes Company (who became her American publisher after she left L. C. Page, and to whom she had sold the rights to Anne’s House of Dreams), she began looking in her notebook for ideas for her next novel. The plot of Rainbow Valley began to emerge, with the sound of impending war in the background.

The great Halifax Explosion was in early December 1917. Maud’s first thought, like that of many others, was that it was a German attack. This extraordinary tragedy—2.5 square miles of Halifax levelled and 1,600 people killed by the explosion of a ship carrying munitions—seemed to bring the war onto Canadian shores.

By now, stretched between her duties as a minister’s wife, a mother, and a writer, and her worries about the war, Maud’s physical health began to suffer. She was continuously sick with colds or the flu, or other ailments. People noticed that her hands were never still: they were knitting socks for soldiers, crocheting, or otherwise in perpetual motion, nervously wringing or grasping each other. Maud always lived on the edge with her nerves, and her emotional fragility increased during this time, both because of the war and because of her looming legal dispute with her publisher, which had the potential to ruin her financially.

In Rainbow Valley, started in early 1917 and finished in December 1918, she found her own memories of an idyllic childhood irrelevant. She had grown up thinking that wars in other countries were as far away as the moon. It seemed beyond comprehension that the world could have shrunk so fast. National boundaries and oceans of space no longer protected people from war in other lands. In this novel, Maud made a transition from the isolated and lovely atmosphere of Avonlea to the horror of war in Europe.

Maud finished Rainbow Valley the day before Christmas, some six weeks after the war had ended. The novel is set before the war, but as she wrote it, she knew the outcome of the war, who would die, and who would return. Her half-brother Carl Montgomery had lost part of a leg at Vimy Ridge; Edwin Smith had been decorated for service by the British Navy and demobilized; and many of the young men she had taught as boys in Sunday School were now lying beneath the poppies in Europe. She dedicated her new book to three of the young men in the Leaskdale and Uxbridge parishes who died in the war: “To the memory of Goldwin Lapp, Robert Brookes [sic], and Morley Shier, who made the supreme sacrifice that the happy valleys of their home land might be kept sacred from the ravage of the invader.”25 The language of the dedication reflects the language of the pulpit, the Bible, and World War I propaganda.

In this book she introduces the Meredith family: a sad, dreamy widowed minister and his neglected, unruly children. Another new character is the orphan Mary Vance, fostered first by the Merediths, and then by Miss Cornelia. Mary Vance, coming from an abusive background, is coarse and must be nurtured into acceptability. A range of personalities interact: dreamy, bossy, or managerial, lovable or not. Anne and her husband, Dr. Gilbert Blythe, are so mature and respectable now that they are dull. Mary Vance, Miss Cornelia, and Susan Baker (the Blythes’ cook) are the most piquant and forthright. Anne’s son Walter is developed as “different,” a sensitive child who prefers aesthetic interests to rough-and-tumble fighting with other boys. He sees “beyond the veil,” glimpsing into a world that others cannot see.

The setting is “Glen St. Mary,” not far from “Avonlea,” but the people of Leaskdale still point to the Ontario valley that they believe was the basis for Rainbow Valley. Like so many of Maud’s novels, Rainbow Valley gives a sense of a tightly knit, repressive-but-lively-and-bustling Presbyterian community. The sylvan glen that the children call “Rainbow Valley” is a woodland haunt where they escape their hidebound and judgmental community. From its secluded and bubbling spring, they drink pure, cool water. The path from “Rainbow Valley” (recalling “Lovers’ Lane” in Cavendish) leads through the adult community to the wider world outside, and in this future world looms “the shadow of the Great Conflict … in the fields of France, Flanders, Gallipoli, and Palestine.”

On one level, the story provides comfort when John Meredith finally marries, giving his motherless brood someone sensible and practical to love and guide them. Amiable, good, and level-headed only when called to attention, Mr. Meredith spends much of his time thinking about the imponderables of theology. He is an endearing and wistful version of Ewan, an intelligent, abstracted, and generally ineffectual man.

The war precipitated another event. Frede Campbell, Maud’s cousin and treasured “kindred spirit,” had been dating a young chemistry instructor at the Macdonald College named Cameron MacFarlane, but told Maud several times that nothing would come of her relationship with him. He joined the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry. Cameron, home on furlough and now a lieutenant, suddenly proposed on May 16, 1917. Six hours later they were married, just before he left for overseas. Maud described her response to the news as: “Dumbfoundered, flabbergasted, knocked out and rendered speechless.”

However impulsive the marriage, Maud was deeply hurt that Frede had married without telling her first—so much so, in fact, that Maud wrote her correspondent, George Boyd MacMillan, that she had been present at Frede’s wedding, when in fact, she had only visited Frede after the wedding.

Frede had been approaching twenty-eight when Maud married at thirty-six. Several of Frede’s romances had not worked out, and by the time the war came along, reducing the pool of men, Frede was in her mid-thirties, beginning to acquire the derogatory designation of “spinster.” Frede was an intelligent, strong-minded, and independent person. Moreover, she appeared to be launched on a brilliant career as a Home Economist at Macdonald College in Montreal. When women married, whether educated or not, they were expected to give up their professions and tend to their families. Frede joked in the summer of 1918, after her wedding, that she wished she “could have both the ‘job’ and the husband.” This meant that Frede’s education, which Maud had paid for, would essentially go to waste. Of course, many marriages were made in haste during wartime. In 1916, Maud’s younger half-brother, Donald Bruce Montgomery, had married quickly and unwisely in Winnipeg, and Maud saw both of these marriages as further casualties of war.

The war that everyone had expected to last only months dragged on for four years until November 11, 1918. The death of so many young men brought a psychic loss to all of Canada. Many of those who did return came back with missing limbs or with lungs damaged by poison-gas warfare, which shortened their lives. Others returned as psychological cripples, from shell shock or “survivor guilt.” The distinguished Colonel Sam Sharpe of Uxbridge was one of these latter: he committed suicide on his way home from the war, jumping out of a two-storey window in the Royal Victoria Veterans’ Hospital in Montreal. His funeral was huge and attended by many government dignitaries. “Survivor guilt” was not a concept at that time, and people could not understand why he had taken his own life, or imagine how he would have felt if he had been forced to resume life in a community where he would see the parents of young men who had died under his leadership. How could he forget those country roads where he had led his marching battalion of young boys, piping and beating their drums, expecting to return in glory? Many of them were now dead in unmarked graves in Europe, while he had survived.26

Maud, with a mind that ran to literary tropes, became consumed by the image of the “Piper,” an ambiguous figure who at first seemed to be a Scottish bagpiper leading men and boys nobly into battle, but who morphed into a trickster figure: the Pied Piper of Hamelin, leading children to their death. Her imagination was tortured by this shape-shifting character, who had had a very real incarnation in their own community of Scott Township, a bagpiper marching right through the centre of Leaskdale.

In these early post-war months, Maud was finding it increasingly difficult to maintain a positive outlook. In her journals, she expressed growing frustration with a world that did not reward noble thoughts and good deeds. She did not fully understand this changed atmosphere. She accepted religion’s loss of authority, but she was unwilling to relinquish her own belief that justice and goodness should prevail.

Back on June 17, 1916, when the war was well underway, she had voiced in her journal what so many in her generation felt, a feeling that intensified for her as time passed: “Our old world is passed away forever—and I fear that those of us who have lived half our span therein will never feel wholly at home in the new.”

For one thing, the war had reshaped the relationship between men and women. Before the war, and especially in Maud’s own younger days, newspapers and magazines had been full of articles and advertisements depicting women as the “weaker sex.” During the war, women had taken over much of men’s work—everything from running farms to working in munitions factories—and had proved themselves highly capable. Moreover, the war had shrunk the world: people would never again feel safe from the turmoil taking place on distant shores. The technology developed for war would itself transform communication and transportation, speeding up the pace of civilian life, demanding another huge adjustment for the population. Maud, already catapulted from rural Prince Edward Island to urbanizing Ontario, felt the change with particular intensity.

The war’s effect on technology was seen locally. In August 1917, the first flying machine ever seen in those parts had been spotted over Uxbridge. In November 1917, a small aircraft came down unexpectedly in a local field. The whole community converged on the plane and pilot to inspect the strange contraption before it took off again for Camp Borden in Ontario. The local paper gave it a long write-up, concluding:

The Great War has revolutionized the manufacture of air craft.… It is predicted that when the war is over they will come into general use for the conveyance of passengers and mail matter … but we doubt that a very large percentage of our population will trust their lives to any machine that flies through the air. (Uxbridge Journal, July 26, 1917)

The development of automobiles had also been facilitated by the war. In 1918, the Macdonalds bought a car with Maud’s income, a five-seater Chevrolet. Many of the parishioners now had automobiles too. Of course, in the days before snowplows, a car could still not be taken out in winter as it could not get through the drifts; nor could it be used in the spring when the dirt roads were “breaking up,” because it would get mired in the mud. So while travel in winter and early spring was still by traditional means (horse and cutter), there was a general recognition that the world had entered a new mechanized age.

But most of all, the war had undercut the very structures of human belief. The old view of the world, ruled by an omnipotent God who took an active and benevolent interest in all human affairs, was for many nearly impossible to maintain. Decimating a generation of young men hardly seemed benevolent. People might pray just as much, but many were no doubt wondering if God was listening—or if He even existed. If not, then ministers were playing a game of charades, and the Church was nothing but a social institution. Maud herself had already come to this view of the Church. Her pagan china dogs, Gog and Magog, must have smirked in the dark, dead hours of night.

When Ewan Macdonald chose the ministry for a profession, he entered one of nineteenth-century society’s most important and prestigious professions. In the twentieth century, he felt a loss in status, in light of the diminished power of and respect for his profession. Ministers in both large and small communities felt the impact of this changing outlook. The fiery rhetoric of war had turned to ashes in their mouth. Some of the contemplative personalities like Ewan, who had preached for sacrificial heroism while standing safely in his pulpit, were vulnerable to as much “survivor guilt” as the soldiers who returned safely.

Maud would later refer to the “spring of 1914” as the “last spring of the old world” (March 18, 1922). After that date, she said, the world changed. Her own intense sense of personal loss and tragedy were to intensify after the war, and her world view would darken.

On September 1, 1919, Maud wrote in her journal that “1919 has been a hellish year.” For most people, the mere fact that the war was over made it a good year. For Maud, it brought more grief. In 1919, death and mental disturbance deprived her of the two people closest to her. Neither tragedy was directly caused by the war, but both were part of what she described poetically as the poisonous red tide that flowed in its wake.

The “hell” of 1919 had actually started in October 1918 for Maud when she contracted the “Spanish flu” that killed seven thousand in Ontario alone. For two months after, she suffered the languor and depression that followed this illness. This particular flu was unusual in that it often killed the young and healthy, not just the old and sick. Maud reported that so many people died in a short time in Ontario that corpses had to be buried in mass graves because there were not enough coffins.

The Campbell family in Park Corner, Prince Edward Island, also came down with this influenza. George Campbell and his young son died, leaving his mother (Maud’s Aunt Annie) and his young and pregnant wife, Ella, to raise six children all under the age of eleven.

In November 1918, before she was herself fully recovered, Maud left Ewan and the boys in Lily’s care and went to Prince Edward Island to help Frede, who was caring for the entire Campbell family. “Frede and I can always laugh, praise be!” Maud once wrote. “I can’t conceive of Frede and I foregathering, even at seventy, and not being able to laugh—not being able to perceive that sly, lurking humour that is forever peeping round the corner of things” (July 22, 1918). Now, even in a time of enormous distress, after disinfecting the Campbell house, when all were in bed, Maud and Frede shut themselves up to “talk and laugh at our pleasure” (November 9, 1918). Maud was still at Park Corner when the November 11 Armistice was signed. She describes walking down the lane with Frede in the darkness, and across the Park Corner pond bridge “on a grim, inky November night.” They had skipped over that bridge in childhood, but the new world they were in was changing and darkening.

When the flu killed George Campbell, his widow and mother lost their breadwinner—a devastating situation. But at least Frede had a good job at Macdonald College in Montreal and could be expected to help them.

On January 12, 1919, following a dreary Christmas, Maud, still feeling weak and exhausted, went to Boston to appear in court against her publisher, L. C. Page. Relations with Page, who had been such a gracious host in 1911, had turned decidedly sour. Maud was now suing him for the royalties he was withholding out of spite after she moved to a Canadian publisher. He seemed to revel in needling her in every way he could. On Christmas Day 1918, an expensive history book from his firm came to her with a personal note in his own handwriting that read: “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. L.C.P.” The book was named Sunset Canada.27 “Quite free and easy,” she snapped about the unwanted gift. “Especially for the man I’m suing in the Massachusetts Court of Equity for cheating and defrauding me!”

When she arrived in Boston that January, she took an undisguised pleasure in seeing that L. C. Page had aged considerably in the eight years since she had seen him. His appearance showed evidence of the dissipated life she had heard that he had been leading—an observation that suited her sense of justice. She gave her testimony, but the trial continued. On the way home, she looked forward to stopping by Montreal, where Frede was teaching at Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue and supervising the Women’s Institutes in Quebec. She was considered a rising star in her profession. But just as Maud was finishing her business in Boston, she got a wire that Frede had contracted the flu and was seriously ill. The war was over, but this virulent flu was still sweeping the western world, and would eventually kill more people than the war itself had killed. Ominously, this was Frede’s third life-threatening illness.

When Maud arrived at the Macdonald College infirmary, Frede’s condition was desperate: she already had the deadly pneumonia that so often followed this strain of flu. Maud slept in the infirmary, comforting and nursing Frede along with the nursing staff. Frede deteriorated over the next few days. She became too sick to talk, and then to laugh.

Maud and Frede had always been held together by the bond of laughter. Humour allowed them to share problems, re-energize themselves, and pull themselves out of dark moods. Even the memory of jokes shared with Frede helped to steady Maud’s nerves. Now at her bedside in Montreal, Maud tried to cheer her with a tale of little Stuart’s struggle with a pancake. It had been “crisped” at the edge in frying. After trying to cut it with a spoon, he’d asked in a plaintive tone: “Mother, how do you cut pancake bones?” That was the last time Maud heard Frede laugh. On January 25, 1919, Maud waited beside her bed as Frede’s life ebbed away.

It would be months later that she described Frede’s death. “She ‘went out as the dawn came in’—like old Captain Jim in my House of Dreams, just as the eastern sky was crimson with sunrise.” When Maud was able to write again in her journals, she anguished over the prospect of a life without Frede.

How can I go on living when half my life has been wrenched away, leaving me torn and bleeding in heart and soul and mind. I had one friend—one only—in whom I could absolutely trust … and she has been taken from me. (February 7, 1919)

Maud’s pain was so intense that she did not actually write up Frede’s death in her journals until the following September, entering it as a retrospective entry. She had been so overwrought with emotion at the actual time of the death that she was unable to cry or grieve. To her utter mortification, she instead broke out in uncontrollable and hysterical laughter. A friend of Frede’s, Miss Anita Hill, and the nurse held her tightly and comforted her. For two days Maud paced in nervous agitation in the living room of Frede’s residence. Tears finally came, but brought no relief.

Frede’s sister-in-law, Margaret MacFarlane, came to help pack her possessions for dispersal. They found in Frede’s drawer a letter that she had written at the beginning of the flu epidemic directing how to divide her affairs in the event of her death—the wedding gifts from her husband’s friends were to go to his people, everything else to hers. Maud took back the silver tea service she had given Frede at her wedding for Chester’s use when he became an adult. Frede had adored little Chester. Maud also took several other items: a bronze statuette called “The Good Fairy” that had special meaning (she remembered Frede’s joy when it was the first wedding present); a pendant; and earrings of peridot and pearl, which an old beau had given Frede. She thought they might eventually go to Stuart’s future bride, or to one of the Park Corner nieces.

Long before her death, Frede had told Maud that she had a fear of “being buried alive” and a “horror of the slow process of decay in the grave” (January 19, 1919). She had insisted that if she died first, Maud would see that she was cremated. Maud knew that many people, and perhaps even Frede’s own mother, would be upset over cremation, but she followed Frede’s wishes. She put red roses on the casket—Frede’s favourite flowers—for the brief funeral service in the reception area of the “Girls’ Building.” There was another brief ceremony in the crematorium at the top of the mountain in Montreal. Maud wrote:

To see those doors close between us was far harder than hearing the clods fall on the coffin in the grave. It symbolized so fearfully the truth that the doors had closed between us for all time. I was here—Frede was there—between us the black blank unopening door of death. (September 1, 1919)

Emotionally depleted, Maud returned to her life in Ontario. The entire community of Leaskdale mourned Frede’s death. Many years later, people still talked of Frede’s joyous laughter, the genuine, hearty kind that comes from within a person at ease with herself and her life. She made an impression on all who met her.

For weeks after returning home from Montreal, Maud suffered from disturbing dreams and headaches. Well-meaning neighbours sometimes said the wrong things to her. Ewan was unable to comfort her, perhaps because his own demons were depriving him of the ability to empathize. For the rest of her life, Maud would mourn Frede. Every January on the anniversary of her death, memories flooded back. Periodically she would read all Frede’s old letters and feel disbelief that such a vivid personality could be dead. Often when she heard or saw something humorous, she felt a momentary stab of pain because she could not share it with Frede. For a private woman like Maud, one who had been conditioned all her life not to reveal inner worries, the loss of her one trusted best friend was catastrophic.

She and Frede had developed very strong bonds, partly from kinship, and partly from shared experience. They both felt “different” from the rest of their family, that they were the “cats that walked alone.” Each had been a sensitive child who felt misunderstood. At school, each had been clever, leading to a feeling of exclusion from the circle of other schoolgirls. Frede had been a plain, almost ugly child, but, like Maud, she had been radiant with personality and joie de vivre. Each had suffered unrequited love affairs, despairing together that they might never find a mate. Both were ambitious women who wanted to take full university degrees, but neither had a family who could or would pay for them, despite their exceptional intellectual gifts. (Maud had paid for Frede’s training at Macdonald College in Montreal.) Their volatile temperaments were similar, and Frede understood Maud’s rising and falling moods. They shared everything—and when they did, their fears, insecurities, and anxieties turned into laughter. They were both widely admired for their competence and uniquely refreshing personalities, but each had a deep inner, reflective life. Maud was twenty-eight in 1902, and Frede nineteen, when their friendship began to develop, and they had seventeen years of “beautiful friendship” before Frede’s death. Maud wrote:

Well, I must make an end now and face life without her. I am forty-four. I shall make no new friends—even if there were other Fredes in the world. I have lived one life in those seemingly far-off years before the war. Now there is another to be lived, in a totally new world where I think I shall never feel quite at home. I shall always feel as if I belonged “back there”—back there with Frede and laughter and years of peace. (February 7, 1919)

Frede’s death seemed to have a domino effect: next, Ewan began to suffer from a deeper bout of serious depression. Ewan had always basked in Frede’s warm approval, and her death deprived him of someone who boosted his confidence.

When he was well, Ewan was a smart, cheerful, practical man, with dimples and sparkling dark eyes. His sense of humour was a very different kind from Maud’s dry, wry, razor-sharp wit—he teased, bantered, and enjoyed playing practical jokes. When trying to tell a clever anecdote, he usually got the timing or punchline wrong. But his general affability made him lovable. Most of all, he was a kind man—the “kindest man who ever lived,” his son Stuart Macdonald said to me repeatedly. After years of dodging her Grandfather Macneill’s sarcastic digs, Maud valued kindness.

In many ways, Maud and Ewan complemented each other. Maud was a driven “hard worker” in every respect, while Ewan “took things easy.” She was “high-strung,” living daily on her nerves; he was phlegmatic. This might have been a good combination, with Ewan able to calm Maud when she was overwrought, and her boosting him when he was too full of lassitude. There were complications, however: Ewan was subject to depression and Maud to wide mood swings. And there was little space in Ewan’s stern Scottish-Presbyterian culture for open discussion of his private feelings. Ewan had been raised in a world where men discussed actions and beliefs, but not their feelings. These he hid under his reserved exterior, brooding darkly. After the war, a major depressive episode washed over Ewan.

Ministers had to cope with especially hard adjustments after the war ended. Society seemed adrift, and religion no longer acted as a compass. To reorient people to religion, church leaders started a sweeping ecumenical crusade called “The Forward Movement,” the aim of which was to bring congregations back to church, to allow faith to “heal the wounds of humanity.” The most dynamic ministers in various denominations were engaged to travel across the country, giving weeks of inspirational speeches to counter the general drift of society towards secularism.

Ewan’s first major breakdown started the week that the first of these high-powered ministers descended on his parish to speak to his two congregations: the week between May 25 and May 31, 1919. Each night there was to be a different preacher in the area. Ewan was to meet them at the Uxbridge station, ferry them about, introduce them, and listen as they gave energizing speeches to parishioners. Then he and Maud were to host and entertain them at home before they set off again to speak elsewhere.

As soon as the series started, Ewan’s first symptoms manifested themselves in a severe headache and insomnia. His behaviour became increasingly erratic. By mid-week he was morose and withdrawn, still complaining of his headache. He only went through the motions of hosting his guests. Once, he rose before dawn to walk the roads in agitation. Later, he wrapped a bandana around his head and lay in the hammock, moaning. After the men left, his symptoms varied from agitation to a catatonic, glassy-eyed state. This was a new and alarming development.

At the end of that week, Maud insisted that Ewan see the doctor in Uxbridge. Dr. Shier diagnosed his problem as a “nervous breakdown” and prescribed rest, believing that Ewan was overtired from his busy schedule. Ewan was always glad to rest. He sought medical palliatives, such as were available then, to help him relax. Maud gives a spotty anecdotal account in her journals of the drugs that Ewan was taking then and later. However, throughout the rest of the year, Ewan was given various medications: barbiturates like Veronal, and bromides, all central nervous system depressants that doctors of the era prescribed as general sedatives.

Ewan’s trouble came from a deeper source than Dr. Shier recognized. Although he seemed calm enough on the surface, Ewan was a deeply sensitive man. In addition to the guilt he may have felt over persuading young men to join the war, he felt greater pressures resulting from the Church’s waning influence. Another more threatening movement was afoot—this one supported by the government as well as the Church—to merge a number of the Protestant Churches and consolidate congregations into a “United Church.” Many Presbyterians saw it as the destruction of their Church by the Government of Canada, something that seemed unbelievable.

This “Church Union” was going to put many ministers out of a job. Ewan had reason to fear for his own future. He knew he was not as dynamic as the Forward Movement preachers, or as many other ministers he knew. Depressed as he was, he felt inadequate to the challenges ahead. His feelings of inadequacy deepened his depression. It was a downward spiral.

After his visit to Dr. Shier, Maud says that she pried out of Ewan what was really upsetting him. It was, he said, the conviction that he was “eternally lost—that there was no hope for him in the next life. This dread haunted him night and day and he could not banish it” (September 1, 1919). Maud interpreted this as a sign of “religious melancholy,” the term used at that time to indicate a depressive mood disorder that afflicted religious people who would naturally interpret their affliction within their religion’s conceptual framework.

A long medical history was associated with the specific symptoms of the mental disorder that Ewan now exhibited. “Religious Melancholia” dated back to the Middle Ages, possibly earlier. Nineteenth-century texts about mental illness discuss it. Religious melancholics believed that they were doomed to go to eternal Hell after they died, regardless of their behaviour during life.

The Presbyterian doctrine of Predestination—which taught that God had “predetermined” who would go to Hell before they were even born—was an outmoded doctrine in Ewan’s time, but old beliefs die slowly. Predestination was firmly lodged in Ewan’s mind: as a boy, he had heard it preached by old-fashioned rural preachers, and preached again in Charlottetown by an evangelist around the time he was leaving Prince Edward Island for Ontario. It provided him with the explanatory concept to understand precisely why he felt so miserable and depressed.

He linked this to another theological concept: Ewan felt that because he had doubted that he was one of the “Elect” (chosen for Heaven), he had therefore committed the “unpardonable sin” (of doubting God and His power). This idea of the “unpardonable sin” was, like Predestination, an older religious tenet but a powerful one in people’s minds.28 Ewan was caught up in circular reasoning within a complicated theology. Maud railed against the “damnable theology” that had taught him these concepts, but she also believed—probably correctly—that these ideas had taken hold of him so readily because his mind was already disturbed.

Maud says that she dragged more details out of Ewan—confirmation that this mental disorder had first appeared when he’d reached puberty (at age twelve). It had surfaced again at Prince of Wales College when he was eighteen, and again at Dalhousie College. He had been well until his trip to Glasgow in his mid-thirties, in 1906–07. In Glasgow, however, he had been overwhelmed by fears and a sense of inadequacy.

Each breakdown in Ewan’s life had taken place at a pressure point in his life, and had grown from the belief that he somehow did not measure up. This “proved” to him that he was an outcast from God: again, that he had committed the “unpardonable sin” of insufficient faith that God had given him the strength and courage he needed for his profession.

After the war, Ewan’s doubt that religion was the cure to all human woes again proved he was guilty of the “unpardonable sin” and doomed to Hell, where he would burn forever. His saw his fate as having to pretend to his parishioners that he was God’s representative and faithful servant when he inwardly believed he was cursed.

In his breakdown of 1919, Ewan developed all the secondary symptoms of severe depression: social withdrawal, loss of cognitive functions, insomnia, hesitant speech, low energy, constipation, irritability, loss of interest in family and life in general, and obsession with ideas about worthlessness, guilt, and self-destruction. Maud now suspected that the matter was a recurring problem, and that it was serious mental illness. She wrote in her journal: “I was horror-stricken. I had married, all unknowingly, a man who was subject to recurrent constitutional melancholia, and I had brought children into the world who might inherit the taint. It was a hideous thought …”

Mental illness had always been a subject of community gossip on the Island, intensified by the local newspapers of her childhood, which detailed frightening stories of people either “going melancholy” or turning “violently insane.” Those in the first category were likely to destroy themselves, while those in the second were a danger to others. William C. Macneill, a prosperous farmer and father of one of Maud’s many cousins (Amanda), went “melancholy” and drowned himself.

Shortly after 1900, the Island newspapers began expanding their coverage of mental illness, as a result of the new communications technology, the telegraph, which was able to relay news from all over the North American continent. People read, for instance, of cases like that of John E. Sankey, son of the famous revivalist Ira D. Sankey, who was declared insane in New York because he thought he had created the world (covered in April 16, 1908). There was extensive ongoing coverage after 1907 when the New York millionaire Harry Thaw murdered the famous New York architect Stanford White, after White seduced Thaw’s wife, Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, a well-known chorus girl and actress (later immortalized in the movie The Girl in the Red-Velvet Swing). Thaw’s plea was not guilty by reason of “insanity”—a new category of plea in law. For three years the Prince Edward Island newspapers covered his trial and its appeals, and people were riveted to this story. There was wide public disapproval of the fact that Harry Thaw was ultimately acquitted. (Maud pasted a picture of Evelyn Nesbit into her journals, and claimed that she had pinned it up as the visual model for her “Anne of Green Gables.”) Later in that year, a man in Prince Edward Island escaped a murder conviction by pleading insanity and was sent to Falconwood, the province’s insane asylum. After this legal shocker, the province (and Montgomery herself) had an even greater fear of mental illness. Patent medicine firms fanned the flames by advertising in every issue of the paper that they had treatments to “Bring Health to Despondent People.”

Maud wrote in her journals of eccentrics like “Mad Mr. MacKinley” and “Peg Bowen” who roamed around the countryside. They were harmless “crazy people,” present in some form in every community. It is no surprise, then, that Maud’s novels make many references to mentally ill people: recall “Mad Mr. Morrison” who chases “Emily of New Moon” inside a church. This scene was written in the 1920s, following Ewan’s mental breakdown, and is highly symbolic and eroticized. Emily (a heroine based on Maud herself) is accidentally locked together in the darkening church with Mr. Morrison, a hoary old man, who has in his insanity gone seeking his long-deceased young wife. Maud builds up the terror and revulsion that the fictional Emily feels as she flees through the maze of pews in the darkened church, taking flight from the clutches of this crazed but agile madman. Maud registers her revulsion to this old man’s attempt to grasp Emily’s young body. Maud comes perilously close to suggesting the subject of sexual violation by a man who is insane.

Generally, eccentrics and people with mental illness were kept in their communities and tolerated, like “Mad Mr. MacKinley” in Maud’s childhood. Sometimes, if they became too much of a problem or danger, they were sent off to Falconwood. In 1892, when Maud was eighteen, the provincial insane asylum had 137 inmates, committed under the grouping of either “Moral” or “Physical” categories of insanity. “Moral” causes or symptoms included domestic trouble, adverse circumstances, religious excitement, or love affairs. “Physical” causes or symptoms were intemperance (either with alcohol or sex), sexual self-abuse, sunstroke, uterine or ovarian disorders, hereditary or other diseases, and congenital problems like epilepsy. By 1908, with so many astonishing categories to draw from, Falconwood had 223 inmates, ranging from people who had tried to kill themselves (or others) to those who indulged in public masturbation and needed to be put out of sight.

Because Maud had been raised in a print culture of “yellow journalism” that sensationalized and pathologized mental illness, Ewan’s breakdown was particularly distressing to her. Giving front-page coverage to the Harry Thaw trial in Prince Edward Island, the Examiner of February 19, 1907, editorialized: “The vivity with which the American and Canadian People scan the reports of the Thaw trial—loaded with pruriency as they are—is not creditable to the moral tone of the North American continent …” The paper then proceeded to detail all the salacious matter that it so haughtily condemned people for reading, and other local newspapers for reporting.

In the Island society—where most people were born, lived, and died in one place, and everyone knew the family history of everyone else—mental illness simply could not be concealed, and people observed that it did tend to run in certain families. They also noted that while it might be a fleeting occurrence, aroused by passion or despair, and shed with equal swiftness, often the illness recurred. Maud always commented with disapproval when her relatives or friends married into a family that might potentially pass on the “taint” of mental illness.

She began to watch her boys for signs of their father’s instability. Chester and Stuart, who had been her great joy, now became an ongoing source of anxiety. Maud had always puzzled over Ewan’s lack of strong feeling for anything: people, places, things, and especially beauty. His flat response to the physical world now appeared to suggest something missing in his makeup. She noticed how much Chester favoured his father: she described him as “reserved” and “harder to understand than Stuart.” Stuart, however, was frank and open: “Stuart gives the impression of beauty and charm. Physically he is a very lovely child, so clear and rosy his skin, so brilliant his large blue eyes” (February 24, 1919). But she had worries about Stuart, too. “Alas, I fear he has inherited from me something besides my love of beauty—my passionate intensity of feeling and my tendency to concentrate it all on a few objects or persons unspeakably dear to me” (February 24, 1919). The boys were indeed very dissimilar. This was apparent from their earliest childhood.

Maud often lived at the edge of stability herself, but at no point did she lose her hold on reality. In her Prince Edward Island years, she suffered serious depressive states, often quite debilitating. However, she recognized them as abnormal. When she shut herself in a room to pace the floor, or suffered “white nights” of sleeplessness and anxiety, she had perspective on herself. She knew her depressions always coincided with too much solitude and externally depressing circumstances. She also knew what helped her recover: vigorous exercise, good company, and laughter.

Ewan, however, had no perspective on what was happening to him and little memory of his state of mind afterwards. When he had delusions, he believed them. Sometimes he heard voices telling him he would go to Hell and that he should destroy himself. Ewan’s symptoms varied in intensity but usually started with severe headaches accompanied by an expression of profound gloom. He began “pawing at his head” or tying a handkerchief around it. He became very lethargic, taking pleasure in nothing. He would look vacantly into space in absolute silence, or chant doleful hymns, unaware of those around him. If spoken to, he became hostile, refusing to do “his duties as the man of the house” (stoking the fire, carrying out ashes, caring for the horse, and cleaning the stable). His memory became badly impaired, a frequent symptom of depression, and his speech became puerile. Usually, depressed people lose their appetite for food and sex, but Maud states ambiguously that Ewan did not lose his interest in eating, avoiding a comment on his interest in sex. His malady, Maud recorded, cut him off from the “intimacies” of normal life and left him imprisoned by his delusions.

Maud knew that one telltale sign of mental imbalance was self-obsession. Maud characterized her cousin Stella Campbell, on March 12, 1921, as a borderline mental case: “Like all mentally unbalanced people she is completely centred on self.” Maud also remembered with revulsion her cousin Edwin Simpson. He, too, had been totally self-absorbed, despite his intellectual brilliance. When ill, Ewan was completely indifferent to Maud and to his children.

Even Ewan’s appearance changed when he was ill. His facial features developed a “repulsive expression.” His eyes became “shiny,” “wild,” and “haunted.” Maud says she couldn’t “bear to look at him” (January 6, 1923) when he had a “horrible imbecile expression on his face” (March 16, 1924). Sometimes his face turned livid, and he raved obsessively over the idea that he was dying without anyone caring. In other phases of his illness, he would sleep continuously, refusing to get up for several days except to eat. When insomnia overtook him, he fled the house in the early hours, pacing up and down the roads. This alarmed Maud even more: farm folk were early risers and likely to see him, and suspect something was amiss with their minister. When he had visions or heard voices, he muttered out loud to himself, a sure giveaway of his problems. Maud wrote in her diary that aspects of his illness seemed “so unnatural that it fills me with such horror and repulsion that … it turns me against Ewan for the time, as if he were possessed by or transformed into a demoniacal creature of evil—something I must get away from as I would rush from a snake. It is terrible—but it is the truth” (August 31, 1919).

Maud worked hard to keep his mental condition secret, lest her children become social pariahs. Publicly, she attributed his illness to headaches and indigestion. In an era when much of what went on inside the body was largely a mystery, people accepted her explanations. At his worst, she kept him out of sight. When he was only slightly affected, he could keep up a minimal conversation, and they carried out some pastoral visits together, with her carrying the visit through cheerful banter. His malady had one very strange aspect, which was quite atypical of a clinically depressed person: his problems seemed to come and go, quickly and unpredictably. In the space of a half hour, he could change from normal to unbalanced and vice versa. This suggests a more complicated medical issue than mere depression.

Ewan’s first attack, in May 1919, lasted throughout the entire summer. He took medications as prescribed. In desperation, Maud sent him to Boston in June, to the home of his half-sister and her husband, Flora and Amos Eagles. Maud joined him as soon as she could. Boston then had the most advanced North American treatment centre for mental illness, and Maud arranged for Ewan to consult a famous specialist, Dr. Nathan Garrick. Garrick puzzled over the diagnosis: was it, he wondered, “simple melancholia” (a reactive depressive episode largely precipitated by external circumstances), or was it “manic-depressive-insanity” (a serious mental illness that was inherent and would recur again and again)?

There was at that time no effective treatment for either, and Dr. Garrick intensified Maud’s concerns by telling her never to let Ewan out of her sight, lest he attempt suicide—something that he had already spoken of on occasion. Dr. Garrick gave Maud sleeping pills (chloral) for Ewan and told her to make him drink lots of water as his kidneys were not functioning properly. (Slowed body functions often accompany depression.) After a two-month absence from Leaskdale, with their children under the care of the young maid, Ewan inexplicably and spontaneously got better and they returned home. Maud told everyone that Ewan had had “kidney poisoning.” People believed this rather vague diagnosis because she had consulted the best doctors in Boston.

From 1919 onward, Ewan was a new anxiety in Maud’s dark closet of worries. He would recover, and then relapse. He would be treated with sedatives. His changes were unpredictable and dramatic. During some attacks Ewan could function, even if he was dull and miserable. But many other times, he was so mentally disoriented that it was necessary for substitute ministers to fill in. She never knew what a day or week or month would bring.

The Leaskdale congregation remained patient and solicitous throughout Ewan’s recurring illnesses and periods of absence from the pulpit. They had always liked him as a minister, and did not see him in his worst states, so they assumed he had a physical problem. Maud worked so hard for them, and for a long time she placated those who might otherwise have complained. However, the sixty-six parishioners in Zephyr, who paid Ewan $360 a year in 1919, eventually began grumbling that their minister was not worth his salary.29

After the Macdonalds returned from Boston in 1919, Maud hauled out her writing and began working up a plot for a new book, Rilla of Ingleside. Her emotional reserve was depleted, and it would take her nearly nine months just to figure out a plot. “I am the mouse in the claws of the cat,” she wrote in August 1919, after hosting an editor of Maclean’s magazine who had come to interview her for a story. “I talked brightly and amusingly—and watched Ewan out of the corner of my eye.… That is my existence now.”30

Marriages often fall apart when there is serious depression in one partner. Maud says in her diary that she thinks “incurable insanity” is justification for divorce, but that divorces are not part of her family tradition (October 18, 1923). Maud and Ewan had grown up in a culture and time where divorce was considered a scandal. In the 1890s, Queen Victoria’s vigorous condemnation of divorce was reported in the Prince Edward Island newspapers. Other newspaper articles lamented that divorce was becoming a scourge in the United States. On March 6, 1901, The Daily Patriot had crowed that Prince Edward Island had “not [had] a single decree of divorce granted … in … 33 years,” adding proudly that it “is extremely doubtful if any other province or state in the English-speaking world can furnish such a record as this.” The paper noted that in this same period there were 268 divorces in the rest of the Dominion of Canada, with its population of 6 million people. In 1911, the year of Maud’s marriage, Prince Edward Island still held its head high as a province unsullied by divorce, crediting the low divorce rate to good education and a morally upright population.31 They did not comment on the fact that in this same period various murders, poisonings, and spousal abuse cases on the Island, resulted in one of the marriage partners being tossed into Falconwood or jail.

On May 16, 1918, the Uxbridge Journal noted that the Canadian Parliament was debating whether the Senate or the courts should grant divorces. Although attitudes were changing, Maud could not have coped with either the emotional upheaval or the scandal of a divorce, even if she had wanted one—which, apparently, she did not.

As Maud came to contemplate the troubled life stretching endlessly in front of her, she could see that she had shown enormous strength thus far. She had fashioned herself into a very respectable woman by marrying, and in particular by marrying a minister. She had, in her maturity, a will of steel, a genuine affection for the man she had married, and a determination to live her life with dignity. She had become famous, and was widely admired and revered, and she enjoyed her fame and reputation. To abandon a sick husband would have been unthinkable to her, no matter how she might have wished to be freed of his problems. She knew her marriage had its tragic dimensions. So, it appears, did Ewan. He suffered under the additional pressure of fearing that he was a leaden weight in the soaring heart of his exceptionally gifted wife.

Ewan and Maud on their honeymoon in Scotland, in the summer of 1911.

The Leaskdale, Ontario, manse, circa 1911 (Maud’s first home after her marriage).

Leaskdale Presbyterian Church (Ewan’s primary charge).

Zephyr Presbyterian Church (Ewan’s other charge).

Maud and Stella Campbell at Niagara Falls.

“Gog and Magog,” Maud’s china dogs, in Leaskdale.

Dining room in the Leaskdale manse, with Maud, cousin Frede Campbell, and Ewan, holding Chester.

Marjory MacMurchy, a Toronto writer and journalist.

Maud and her first son, Chester Cameron Macdonald, circa 1914.

Ewan in the Leaskdale garden circa 1914.

Marshall Pickering, who sued Ewan after a 1921 car accident.

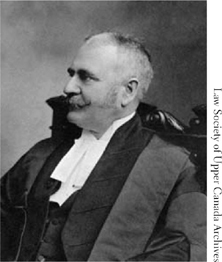

Justice William Renwick Riddell (1852–1945), who presided over the Pickering-Macdonald decision.

The Reverend Edwin Smith.

Picture from Maud’s PEI scrapbook, showing the young Edwin Smith.

Ewan and Edwin Smith.

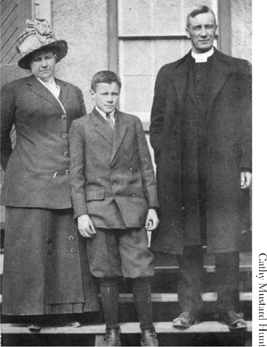

The Rev. and Mrs. John A. Mustard and son Gordon.