The movers came early on February 15, 1926, taking the re-labelled crates without incident. (Pickering’s tale, it seemed, had been floated only to scare them.) They spent the next two nights with Leaskdale parishioners, allowing Ewan time to finish up church business. On Wednesday, February 17, at 9:00 a.m., the Macdonalds left Leaskdale in three cutters; they stayed overnight at the Walker Hotel in Toronto. The next day they were met by Ernest and Ida Barraclough, parishioners who would host them until their furniture arrived in Norval. Maud felt heartened when they settled in the Barracloughs’ well-appointed house to a warm supper and good conversation.

Ewan would again serve two parishes: Norval and Glen Williams. (Each congregation had voted to remain Presbyterian rather than become part of the new United Church.) Each little village lay in a glen with a river curving through it. The Presbyterian churches themselves were huge, stately edifices, very unlike the modest little structures of Leaskdale and Zephyr. The Norval manse, a two-storey, red-brick house, was a large and handsome one, a big step up from Leaskdale’s plainer yellow-brick manse.

The Barracloughs, who lived in Glen Williams, seemed like old-world aristocracy to Maud. Ernest Barraclough, a small, dapper man with patrician manners, was a prominent elder in the Union Presbyterian Church of Glen Williams, and reputedly the wealthiest man in either congregation. Originally from England, he owned and ran a large and prosperous woollen mill. His large brick house at 25 Mountain Street stood atop a hill overlooking his mills and the town below. His wife Ida Stirrat came from a prosperous local family. The gracious Ida was much larger than her slim husband—indeed, she was stylishly ample in size, with regal carriage, and was always tastefully and handsomely attired. She was well liked in the community. The Barracloughs had no children.

There was much to learn about the new community and parish. As talk rambled, Ewan and Maud shot to attention upon learning that the treasurer for both churches, a young man named John Russell, had a connection to Zephyr: he was engaged to a woman whose brother was married to one of Marshall Pickering’s daughters. They were horrified. Now Ewan would have to explain the whole lawsuit to the church managers, requesting to be paid in advance. People here would not know the circumstances of the case and would assume that their new minister had skipped out on a bona fide legal judgment against him. What would people say? The Macdonalds did not sleep well that night.

As soon as their furniture arrived a few days later, the now-anxious Macdonalds returned to Norval to set up their new home. From the top of the hill at the radial train station stop, they surveyed the dark village below, and saw the church spire rising out of the gloom, with the manse beside it.

Maud knew that Norval and its surrounding area was considered one of the “beauty spots” of Ontario, and although it was a cold February night with whipping winds, she was thrilled with her new home. She could live in this self-contained rural community, and yet hop on the “radial” train (an electric train much like a streetcar) and go to Toronto. The radial station was adjacent to the home of John Russell’s parents’ farm at the top of the glen, an easy walk from the manse. Norval itself resembled a Scottish glen as envisioned in novels by J. M. Barrie or Sir Walter Scott. The Credit River reminded Maud of the tumbling mountain streams she had seen in Scotland. It was far more romantic than the quiet little brook that bubbled through “Lovers’ Lane” in Cavendish. She wrote her Scottish pen-pal, G. B. MacMillan, that Norval was more like an “old-world” village than a Canadian one. She could not have found a place in southern Ontario more to her liking. She was prepared to put down deep roots here.

Norval was nestled in a long valley, with steep hills on each of the four sides. The Credit River curved into town from the north-west and exited through the south-east part of the glen, on its way down to Lake Ontario.

The picturesque village was anchored by two imposing structures: the red-brick Presbyterian church at the west end and a huge stone gristmill straddling the river at the east end. Topping the mill roof was a small cupola, with a gnome-like weather vane. The main street—with its hotel, general store, hardware store, bank, butcher shop, bakery, and candy store—was lined with both small and large homes. In the middle of the village, a road came down the south hill (named “Cemetery Hill”) from the cemetery and close to the radial station at the top of the glen, crossed the main street and then the river, and curved up the facing northern hill (“Station Hill”) past the rail road station, then headed through the scenic countryside of farms towards the Union Church, which lay at the top of the glen above Glen Williams.

Norval had been founded on land that had been purchased from the chiefs of the Otter and Eagle native tribes around 1818 by a Loyalist of Scottish descent named Alexander McNab, and was soon joined by his brother James. They saw the potential in the Credit River and built the first gristmill in the 1820s. By 1827 James was offering free land grants to tradesmen who would settle there.

Tradition said that the village took its name from a line in a Scottish play by John Home (1722–1808) called Douglas: “My name is Norval; on the Grampian Hills …” The area was rich in oak and white pine trees which could be floated down the Credit River to Lake Ontario. The original gristmill supported other industries: a cooper shop to make barrels for shipping flour, an ashery that burned hardwood cleared for farmland and produced the potash from which soap was made, and the Gooderham & Worts distillery. Later, Norval included a tannery, brickyard, bakery, woollen and flax mills, a broom factory, brass foundry, and a carriage works. Norval was a main stagecoach stop along the earlier plank road between Guelph and Toronto, and had several hotels and inns. At its peak in the nineteenth century, it was a thriving town of four hundred people.

The Norval gristmill, said at one point to be the largest in Canada, produced some three hundred barrels of wheat flour per day during World War I. Wheat was shipped from the west for processing in Norval, and by the late nineteenth century Norval billed itself the “wheat processing capital” of Canada. Traffic came through on the railroads, and immigrants from the United States were said to “flow like a flood towards the golden acres of the setting sun” out west on the railway. Norval grew into a thriving village with three churches, a Mechanics’ Institute, and an Orange Lodge.1

When the Grand Trunk Railway had come through in the later nineteenth century, however, farmers near town held out for a too-high price for their land, and the railway was subsequently laid out one mile north of the village. This distance was fatal, and the main train made its last stop at the Norval station in July 1926. When the Macdonalds moved there, Norval had shrunk to about two hundred and fifty inhabitants.

The Toronto-Guelph electric suburban radial railway, opened on the south side of Norval in 1917. Maud could travel to Toronto on her own, for shopping or to attend literary meetings and events, or in the other direction, to Guelph, where she made shopping trips to see her favourite millliner to buy the fancy hats she had always loved. For a woman who never learned to drive a car, accessible public transportation was a godsend.

Because Norval lay in a valley, it was an echo chamber. Maud loved the double echo in Norval. When she called her cats, the sound echoed back twice, first from the buildings, then from the hills.

At Ewan’s induction, nearly three hundred people braved three-foot-high snowdrifts to attend, some arriving two hours early to get a good seat in the large church. The local paper noted that one of the important ministers attending was the Reverend John Mustard of Toronto. The paper also boasted that “the Rev. Ewen McDonald [sic] was married to Anna [sic] Montgomery, author of Green Gables.” Maud was now fifty-one years old, author of fifteen internationally acclaimed books.

Ewan soon met John Russell, the church treasurer. To Ewan’s astonishment and relief, Mr. Russell revealed that he already knew about the Pickering case, and had told the Session managers that it was “a framed-up job to extort money” from the Macdonalds. He had already arranged for Ewan’s salary to be paid in advance. Ewan and Maud were mystified by this loyal support, given before Russell had even made their acquaintance, but they nevertheless welcomed it. The Russell family became their fast and loyal friends. Their house was visible at the top of a hill with a picturesque fringe of pine trees; Maud would always affectionately call “Russells’ Hill” the “hill o’ pines.”

Ewan and Maud felt immediately at ease with the people in both parishes. The earliest settlers there had been mostly Scots or Scots-Irish (many from County Antrim in Ireland).2 The first Presbyterian worship group had been founded in 1833, with a circuit minister riding to Norval on horseback and holding church services in people’s homes. The Presbyterians had built a frame church around 1839, but a quarter century later replaced it with the splendid Gothic brick church, costing the huge sum of $7,000 in 1879 (The Anglicans had built themselves a modest frame church in 1846 and the Methodists had built their little church in 1850.) By the 1860s, Norval had erected a fine brick school to replace its wooden one. Norval had even had its own militia group and drill shed during the Fenian raids. The land around the village was so scenic that Upper Canada College of Toronto purchased five hundred acres of land on the Credit River upstream from Norval, to be used for student retreats.

It secretly pleased the Macdonalds that the church and stately manse (built ten years after the church at a cost of $2,700) were the most outstanding buildings in the picturesque little village, and far nicer than most others in Ontario villages. Several other houses were beautifully landscaped with trees, shrubs, and flowers.

Maud had loved the natural beauty of Cavendish, and she thrilled that their new home was a youngster’s paradise, for the sake of her boys. Upstream, the Credit River wound down through much higher hills, cascading, twisting, and turning through rugged bush until it forked and flowed peaceably into Norval. The river’s tributaries and branches meandered in a leisurely way through town, making an extensive riverbank for play and picnics. The Credit was then gathered by a large dam that provided the water power for the flour- and gristmills in the south-east part of the village (where Highway 7 runs now). In summer, youngsters could fish, sit along the bank and talk, or swim in the large reservoir of dammed-up water. In winter, they cleared the snow off the dam to make a large rink for skating. The girls figure-skated or played “crack-the-whip” and the boys played tag or “shinny-hockey,” using wads of Eaton’s catalogue pages to pad their shins. Mindful of the hazard posed by rapids, which did not freeze-over solidly, children could skate for miles on the river. On bright starry nights, parents sometimes built a bonfire on the shore and the skating continued. According to old-timers reminiscing in the 1980s, some of the families brought organs, guitars, and mouth-harps, and after outdoor activity on the river, they would congregate in one of the homes to sing, play games, or make pull-taffy.

The roads coming down the hills at each side of the glen made wonderful sledding for the children, too. The main road through Norval was paved around this time, since it was the only provincial highway from Guelph to Toronto, but the lack of snow-clearing equipment meant that cars were rarely taken out after winter snows began in earnest. Horses and sleighs moved more easily through the snow and they went slowly enough that children could hitch their sleds to a farmer’s sleigh as he left town, getting a ride up the steep hills, then slide back down the hill. Or sometimes they went “hookeying”—hooking their sleds to the sleigh of a farmer leaving town, and when they met another farmer coming in, switching sleighs to get pulled back. For those who wanted even more speed and danger, there was a toboggan chute down Russells’ Hill.

Glen Williams had as much charm as Norval. Its huge grey-stone Union Presbyterian Church, even more striking than Norval church, stood at the top of the hill that climbed out of Glen Williams. The countryside between the two parishes was filled with expansive farms, and in some areas there was some red soil, as in PEI. The well-to-do farmers maintained their two parishes well, and were very glad to get a minister because, after a bitter fight over Church Union, their pulpit had been empty for five months.

Ewan felt proud to have secured this idyllic location for his family. As for Maud, she could live in the kind of scenic country setting she loved, in a place with extensive walking areas as beautiful as “Lovers’ Lane.” Her boys were growing up fast, and if Ewan only remained reasonably well, she would get her life back again.

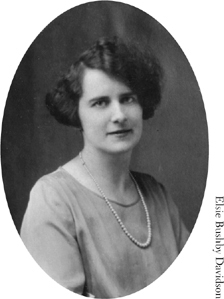

Maud had brought her maid, Elsie Bushby, from Leaskdale. For all her good housekeeping qualities, however, Elsie was inexperienced with men, and easily flattered by any attention. Trouble began when a young man named Rob began courting her. He hung around the Macdonalds’ manse all day, staying (uninvited) for meals, talking incessantly, and bad-mouthing many in the church and community. The Macdonalds found his presence intrusive, but since his parents were in the congregation, they had to endure him. When Rob and Elsie started coming in late after rides in his car, people talked. Maud knew that if Elsie got herself “in trouble,” Elsie’s family would hold her responsible.

Heating systems in a house like the Norval manse were a great conduit for conversations from other rooms. One evening after Elsie returned home late, Maud sat by the heating grate above the kitchen and listened to Rob encouraging Elsie to come to work in Toronto, where he had recently taken a job in a garage. She then heard Rob abuse her and Ewan for using their living room for their own guests when Elsie was entertaining there. Carried by Rob’s volubility, the easily led Elsie declared that she “hated the Macdonalds.” (June 11, 1926).

Maud prided herself on treating her employees well, and she had often heard Elsie tell others how much she liked working for the Macdonalds. Maud was particularly fond of Elsie, but her code of behaviour demanded absolute loyalty and honest dealing from others. She retreated to her bedroom, feeling furious—and deeply hurt.

A few days later she heard angry voices downstairs at 2:00 a.m., and she crept down the back stairs to listen. Elsie and Rob had come in late, made a snack for themselves, and ransacked Maud’s private desk. They were reading her notes—the dated daily jottings of factual events to write up in her journals when she had time. She kept these in a private desk in the library. That they had rifled through her private desk was the last straw for Maud. Although Maud blamed Rob for everything, Maud would never trust Elsie again.

The next day she summoned Elsie, gave her two weeks’ severance pay, and told her sharply to go home to her mother. Elsie was floored, not being privy to what Maud had overheard, and also not knowing that Maud objected to her boyfriend, since he was, after all, in the congregation. Elsie went home to her family in total confusion, feeling disgrace and shame. For many years people in both communities speculated about why she had left the manse so suddenly, without explanation. No one knew.

The greater loss was Maud’s. She missed Elsie’s joie de vivre for a very long time afterwards, feeling a mixture of indignation, betrayal, and, most of all, the loss of a young person she had genuinely liked. Finding a good maid was difficult: business was booming after the war, and locally, the Glen Williams woollen mills offered employment to young women. Maud contacted an agency in Toronto and interviewed a woman named Margaret MacKenzie who had just arrived from Scotland. Maud did not like her, but decided to try her anyway, given the lack of other candidates. She could not do without help and continue in her professional life.

At the end of June, the Canadian Women’s Press Club (CWPC), which now had four hundred members and had been going for some twenty years, sponsored a massive meeting called a “Triennial.” It was a conference of high-powered professional women, with about a hundred delegates from across Canada. The Honourable G. Howard Ferguson, Premier of Ontario, opened the Triennial Congress with a speech arguing that Canada would disintegrate without the pull of “the Empire,” and extolling imperial virtues.3Next, selected delegates spoke about their provinces. A newspaper article continued that “Prince Edward Island was represented by a charming speech by Mrs. Ewan MacDonald,” singling her out alone for praise. The many male speakers in the CWPC Triennial Program included Mayor Lorne Pierce, Donald G. French, F. J. B. Livesay, Norman McIntosh, H. Napier Moore, Newton McTavish—all distinguished publishers, literary critics, and journalists of the era.

Newspapers covered the event and listed the important women journalists and writers attending: Judge Emily Murphy of Winnipeg, Agnes Swinnerton, Cora Hind, Madge MacBeth (“Gilbert Knox”), J. G. Sime, Charlotte Whitton, Isabel Ecclestone MacKay. Maud was one of the speakers: she attended functions at the Toronto Press Club, the Grange, and the Royal Canadian Yacht Club. Her old friend, journalist Marjory MacMurchy, gave a tea in her honour. Maud loved circulating once again in the literary culture of Toronto, and enjoyed the role of a successful older writer who promoted new Canadian writers. The good fellowship improved her spirits for weeks afterwards.

Maud enjoyed these trips to Toronto events, staying over with Marjory MacMurchy, Mary Beal, or her Montgomery cousins, Cuthbert and Ada McIntyre. Her publishers, Mr. McClelland and Mr. Stewart, were always ready to take her out to dinner. They discussed new titles and sent her free books, hoping for her promotional blurbs. And she loved shopping at Eaton’s, her favourite department store.

As for Ewan, he had a slight mental slump in April and May after their move, but he soon improved, and it became clear that the parishioners were pleased with their new minister. He left in early August for a month’s holiday with his own relatives in Prince Edward Island. Maud looked forward to having a little solitude in her new home. She wanted a rest—from packing, from stress, and from Ewan himself. She wanted to “own” her new landscape through long, appreciative, often solitary walks.

Chester, now fourteen years old, was continuing to worry her. Maud confided to her journal that he made a “fool” of himself over “every pretty girl he sees” (August 14, 1926). She wondered if this “girl crazy” phase would pass, or if it would cause serious damage in his life. She was relieved that he did some work in the gristmill for part of his summer, hoping that would keep him out of serious trouble. It was great comfort that his reports from St. Andrew’s were good. He clearly had a fine brain.

Maud turned back to her work on the third Emily book, which she had set aside in 1924 when she started The Blue Castle. Between Chester and Elsie, she felt out of patience with young love, but she had to deal with it in the next stage of Emily’s life. Maud had no interest in the inevitable— consigning Emily to marriage. In Toronto, she had met talented professional women like Marjory MacMurchy, who had married only late in life, and her sister, Dr. Helen MacMurchy, who had stayed single. Both had fulfilling and self-supporting careers. But Maud’s reading public was not ready for Emily to choose a career over marriage, even though “companionate marriages” were a hot topic in the media at the time. (These marriages, in which a couple married to have companionship and conjugal rights without intending to have children, were generally condemned. Conservatives and clergymen argued alike that it was God’s plan for women to marry and procreate.)

While the writing of Emily’s Quest progressed, there were tensions in the manse. Margaret MacKenzie, the new Scottish maid, proved to be eccentric and morose, with few skills in either housekeeping or cooking. Worse, she resented all instruction. But Maud decided to keep her for a short period of time because she was afraid of what people in the new community “might say”—namely, that she herself was “a difficult mistress.” An alien presence like this sullen maid, so different from the cheerful Elsie, had a dampening effect on Maud’s own moods. She fought depression. She worried when Chester was often caught lying. She took both of her sons aside at this time and made them promise never to smoke, but Chester started smoking anyway (and was soon caught). Maud’s overwrought reaction was to weep disconsolately, creating a scene that her younger son remembered vividly to the end of his life.4

Late summer brought the interruptions of making jams and pickles for winter, painting the floors in the manse, giving the occasional speech, and attending missionary meetings. There was also a stream of guests. Maud’s half-sister Ila came to visit with her three children. Maud liked Ila, who, she thought, was much more like their father, Hugh John Montgomery, than her other step-siblings, who resembled Mary Ann.5

In September Maud had a very welcome guest from Cavendish, Myrtle Macneill Webb. She was not the special soulmate that Frede had been, but she was discreet and a “kindred spirit”—someone with whom Maud could both laugh and reminisce. They shared a love of gardening, nature walks, cats, and gossiping about family and people in Cavendish. Ewan drove Maud and Myrtle to Aurora so that Myrtle could see St. Andrew’s, Chester’s private school. They visited old friends in Leaskdale, saw the movie Ben Hur in Toronto, made an outing to Niagara Falls, visited Brampton’s Dale Greenhouses near Norval (said to be the largest greenhouse in the world at that time), toured the University of Toronto campus, particularly Knox College, and then drove around the beautiful Caledon Hills north of Norval, coming home through Belfountain, one of the most picturesque little towns on the winding Credit River. It was a restorative visit for Maud, Myrtle, and Ewan, who enjoyed chauffeuring them around.

The fall of 1926 was busy. The Macdonalds joined in local community fun such as corn roasts, sitting on boxes around the fire by the river, eating candy and roasted corn, telling jokes, singing songs, and generally having a good time. In October, Maud and Ewan had a happy reunion in Galt, Ontario, with the Reverend James K. Fraser, one of her favourite former elementary teachers in Cavendish. Maud and Ewan restarted Young People’s groups in their new parishes, and she was delighted to find that there were talented “organizers” in this parish who did not rely solely on her for ideas. She had time to catch up on her correspondence.

To Lorne Pierce, Toronto’s most influential editor and publisher, she sent some items at his request: a picture of herself, of the Norval manse, and of her old home in Cavendish, plus a manuscript he had asked for, her poem “The Choice” (which she said expressed her philosophy of life). She added a short biography which ended with the information that she had married a Presbyterian minister and had “two sons, aged 14 and 17 respectively, two cats and seventeen hens.”6

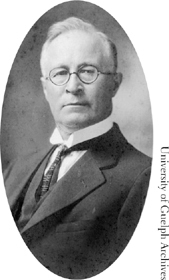

Lorne Pierce (1890–1961) was a founding member of the Canadian Authors Association (CAA), the Bibliographical Society of Canada, and the Art Gallery of Ontario. The editor of Ryerson Press from 1920 to 1960, he devoted his career to the development of Canadian literature, culture, and history. Being noticed by Lorne Pierce meant a great deal, and Montgomery desired nothing more than to be recognized for her achievement on both the national and international stages.7

There were more church activities: for one “Fowl Supper” Maud baked, brewed, made cake, jellies, salads, and “mock chicken,” and then performed as entertainment. After the rain took the fall leaves and the world buckled down for the winter, she still had her beautiful pine trees. She could lie in bed looking at them standing guard at the top of Russells’ Hill, in a “delicate, unreal, moonlit world,” or wake and see them talking “to the sky against the fires of sunrise” (November 1, 1926). Maud’s dreams always reflected her state of mind. She started re-imagining an old dream of discovering, in a house that she had been living in for years, a new and unexpected suite of beautiful rooms. A dour Presbyterian might have predicted that happiness would soon give way to trouble.

Between fall 1926 and 1927, two items were published that Maud does not mention in her journals. The first was a high-profile study of Canadian writers that denigrated her books as the worst writing Canada had produced— an attack that had enough influence that it inflicted a long-festering wound. The second was a small typographical error that opened the old wound of gossip from her childhood and her Leaskdale years.

The first assault, in 1926, on Maud’s reputation was totally unexpected. An ambitious young lawyer named William Arthur Deacon had moved to Toronto from Winnipeg and had the goal of establishing himself in the powerful newspaper and magazine worlds as Canada’s pre-eminent literary journalist. There were already several established literary journalists (such as Stanley Morgan-Powell of Montreal), but Deacon aimed to become the first full-time book reviewer in Canada. (Newspaper journalists had dominated the field of book reviewing and criticism before World War I, and they still had the most influential voice through the 1920s. Academic criticism began to develop only after the war, and became much more important in the 1930s.)

After World War I ended, Canada saw itself as a young country ready to develop a national literature. William Arthur Deacon, a man of huge ambitions, was “infused with a sense of mission for the establishment of an entire, self-contained, dynamic Canadian cultural milieu—a Canadian authorship, a Canadian readership, a Canadian literature—and sometimes he called himself its prophet,” according to Clara Thomas and John Lennox in William Arthur Deacon: A Literary Life. Deacon wanted to develop the literary consciousness of Canadian readers, educating the Canadian public into more “sophisticated tastes.” Like so many other literary nationalists (including Maud), he wanted Canada to develop world-class writers and its own literature.

Deacon regarded as hopelessly old-fashioned the writers who appealed only to “lowbrow” unsophisticates; among these he listed popular novelists like Montgomery and Ralph Connor, both widely read beyond Canadian shores. He described these writers as a national embarrassment. In particular, he regarded Maud’s books as shallow sentimentalism and the “nadir” of Canadian writing. Literary styles were indeed changing: “Victorianism” and “Realism” were going out of style, and “Modernism” was coming in. Deacon saw himself as the critical voice who would sweep out the old and bring in a new, modern criticism and literature.8 (At the same time, a young generation of academic critics were establishing themselves in a parallel role in the universities, and articulating a more intellectualized approach called “Modernism.”)9

A man of prodigious energy, Deacon worked hard writing reviews, promoting writers, engaging in political activism, and keeping in touch with everyone in the book world. He was literary editor of the influential Canadian magazine Saturday Night from 1922 to 1928. And in the autumn of 1926 he published Poteen, a book of essays on Canadian culture, politics, and literature, intended to provide “a concise literary history of Canada” and to demonstrate “justifiable pride … in an emerging literature that already has such worth and distinctiveness.”10 This book (which Maud read) helped establish his reputation as a growing power in the Canadian literary world.11

In Poteen, William Arthur Deacon did not damn with faint praise. Instead, he ended a major chapter with an open attack on Maud’s popularity and reputation:

Lucy M. Montgomery of Prince Edward Island shared the quick popularity of [Ralph] Connor in a series of girls’ sugary stories begun with Anne of Green Gables (1908). Canadian fiction was to go no lower; and she is only mentioned to show the dearth of mature novels at the time (p. 169).

Maud is dismissed on other counts, too. Deacon provides two lists of noteworthy Canadian writers, first of adult fiction and then of children’s literature. Poteen does not include Maud in the first category, although he does include other women writers like Mazo de la Roche, Mabel B. Dunham, Gilbert Knox (pseudonym for Madge MacBeth), Martha Ostenso, Marjorie Pickthall, and Laura Salverson. Nor does he include Montgomery among the Canadian writers who write for children, like (Margaret) Marshall Saunders (Beautiful Joe) and Catharine Parr Traill.

Poteen also includes a survey of the academics who had recently written surveys of Canadian literature. Deacon criticizes Professor Archibald MacMechan of Dalhousie (Maud’s former teacher) for giving attention to Anne of Green Gables in his Head-Waters of Canadian Literature (1924), and he slams MacMechan’s summary chapter as “valueless” because he writes “on the ‘best-sellers’ of the period instead of on the works of literary merit regardless of commercial success” (p. 211). (Maud’s writing is clearly in his sights here.) Deacon promoted the idea that “best-sellers” were usually inferior to serious works of fiction because the masses liked them. Although he disparaged both Ralph Connor and Montgomery, his greater contempt was for Maud. Later in his life, Deacon read Connor’s autobiographical writing, and revised his opinion of Connor when he had more insight into the issues in his books.12

Maud was certainly accustomed to the occasional reviewer complaining that her books were too sentimental, or finding other faults with them. The war had undeniably changed public tastes. She saw that women were caught between the old attitude that they should subjugate themselves to their husbands and the new one that they could have independent ambitions for themselves. By the 1920s her books were beginning to reflect this new reality. Rilla, the Emily books, and The Blue Castle, for instance, all deal in subtle ways with the complicated social forces that impede women’s advancement, achievement, autonomy, and authorship.

Maud’s style was that of a storyteller, with none of the hard edges of Modernism. Her popular best-sellers, “idylls,” and “romances,” made her a ready target for Deacon.

Up to this time, Maud had had generally good press from newspaper reviewers and academic critics. In 1914, one of the earliest critics, Thomas Guthrie Marquis, wrote of Montgomery in his multi-volume Canada and its Provinces: A History of the Canadian People and Their Institutions:

Sympathy with child life and humble life, delight in nature, a penetrating, buoyant imagination, unusual power in handling the simple romantic material that lies about every one, and a style direct and pleasing, make these [Montgomery’s] books delightful reading for children, indeed, for readers of all ages.13

In Head-Waters of Canadian Literature, Archibald MacMechan quotes Mark Twain’s praise for Anne of Green Gables (“In Anne Shirley you will find the dearest and most moving and delightful child of fiction since the immortal Alice …”). Although generally favourable to Anne, and undeniably impressed by its having sold a reputed 300,000 copies in the first eight years, he carefully qualifies his comments, saying the readers of Anne have “a great indifference towards the rulings of the critics” and that “the deftness of touch, is lacking; and that makes the difference between a clever book and a masterpiece.” However, he does judge that “the story is pervaded with a sense of reality; [and] the pitfalls of the sentimental are deftly avoided …”14

Another more substantial 1924 study, Highways of Canadian Literature: A Synoptic Introduction to the Literary History of Canada (English) from 1760 to 1924, by John Daniel Logan and Donald G. French, makes many references to Maud as a regionalist who shows “the beauty, the humour, and the pathos that lies about our daily paths” (299):

In Anne we have an entirely new character in fiction, a high-spirited, sensitive girl, with a wonderfully vivid imagination; … so altogether different from the staid, prosaic, general attitude of the neighbourhood … (p. 300).

The authors praise Maud’s authenticity, and find a psychological depth in her characters that has wide appeal to adults:

In Emily of New Moon (1923) Miss Montgomery created a new child character.… The chief difference … is that she employs a more analytic psychological method in depicting her heroine— a method that tends to produce an adult’s story of youth … which makes equal appeal to the young in years and the young in heart (pp. 301–302).

Dr. Logan was a distinguished professor of Canadian Literature at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, with a Ph.D. from Harvard (at a time when most professors held only Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees). Donald French was a Toronto author and critic and honorary president of the Canadian Literature Club of Toronto. (Maud wrote proudly in her entry of March 5, 1921, that Dr. Logan had said in a lecture: “that Canada had produced ‘one woman of genius’—that ‘L. M. Montgomery’ in the opinion of eminent critics ‘equaled or surpassed Dickens in her depictions of child life and character.’ ”)

Deacon enjoyed flying in the face of the prevailing public opinion (and most critical opinion) with his complete dismissal of Maud’s books. By 1926, at age thirty-six, he was at the beginning of a long and influential career, and attacking a living Canadian literary icon was a useful tactic for a new critic who wanted to be noticed.

Maud knew Deacon personally. She may not have realized at first how much his negative assessment would affect her ranking in the canon of respected Canadian books, but his words were painful to read, and she said nothing about Poteen in her journals. She mentioned Deacon’s name only twice in her journals, despite the fact that he dominated the literary scene in Toronto during her sixteen years in Norval and Toronto, and they were both active as executives in the Toronto branch of the CAA. Both entries express her dislike for him, but give no specific reasons why.15

Deacon consolidated his power in the CAA. He became an activist in reforming Canadian copyright law. He promoted books, authors, and cultural events. As Thomas and Lennox observe, “In these days before the CBC there was … no national communication network and Deacon’s enterprise, combining reviews with literary news and gossip, was certainly devised to join together the book lovers of Canada and to give them access to books.”16 A tireless and lively letter-writer, Deacon was skilful at behind-the-scenes networking with others in the book world, mostly within the growing “old boy” network of publishers, periodical editors, anthologizers, and male professors who were starting to establish the “canon” of Canadian literature. He cultivated them, and they respected his growing influence. His ability to promote writers—or attack or ignore them—made him a very powerful figure, especially with writers and publishers. Occasionally he was obsequious in letters, but most often he was forceful and assertive and confident. He was kind to younger writers or to old friends, like Winnipeg’s Judge Emily Murphy, but he could be abrasive. When the best-selling writer Mazo de la Roche sent him factual information about herself to help him in reviewing her new book, he responded: “Doubtless you were right to approach me, though nothing usually makes me quite so hostile as a request for a favorable review—no matter how subtly the appeal may be conveyed.”17

He worked not through a specific argument so much as by labelling.18Both words (“sentiment” and “sentimentality”) were highly pejorative in modern criticism. “Happy endings” were also a part of this critical discussion, and Deacon linked “happy endings” to sentimental writing. “ ‘Unhappy endings’ are often necessary artistically; and generally fatal commercially,” he wrote in a letter.19 Maud would introduce this discourse on “happy endings” in Emily’s Quest, finished in late 1926 and published in 1927, satirizing “unhappy endings” in the story about the writer “Mark Delage Greaves.”

Maud’s over-sensitivity made it easy for verbal thorns to prick her. Her grandmother’s phrase “What will people say?” remained a lifelong incubus sitting on her shoulder. By the Norval period, she was repeating that line anxiously to her own sons, just as she had heard it in Cavendish during her own childhood when it was used as a powerful agent of social control. In 1927, her incubus found another sharp thorn for its arsenal.

In August 1927 a magazine called The Canadian Countryman began serializing The Blue Castle. This mass-market magazine would take her novel into rural homes all over Canada, including, of course, those in Leaskdale and Zephyr.

The magazine apparently typeset the novel from Maud’s own manuscript, which, unfortunately, had a revealing slip in it, one which had been caught and corrected in the published novel. In just one place, she has called the dashing hero of The Blue Castle, Barney Snaith, by the name of “Smith.”

The last thing in the world Maud would have wanted was for the good folk of Leaskdale and Uxbridge to suspect that the charismatic Reverend “Captain Smith” might have provided the model for the virile Barney Snaith, who roared about in his car rather like Smith did in his, and rescued the frustrated Valancy from her pinched life.

Maud was extremely skilled at concealing the origin of her novels. She maintained a façade of control which kept the passions in her heart out of everyone’s sight. Her professional reserve ensured that no one saw the relationship between her heroines and her well-camouflaged multiple alter egos. No one around her fathomed how frustrated and bored she often was with the life she found herself in.

Maud’s practice was to read each of her books or stories as soon as she received her personal copies. If there were errors, she corrected them in the margins. Her copy of the Countryman has not survived, so we can only conjecture that she felt consternation when she spotted her embarrassing slip, and realized that only one mean-spirited person in Zephyr needed to notice it in order to resuscitate Lily’s gossip over the telephone party-lines.

In late November 1927, with the serialization well underway, Maud mentions in her journals that she suffers from a fierce attack of her “neurasthenia.” She writes in her journals how “old wounds reopened and bled” (November 30, 1927). In an entry on November 28, 1931, the depth of her lingering anger at Lily resurfaces when she records with thinly disguised glee that Lily is pregnant out of wedlock and has to marry the widower who employed her after she left the Macdonalds. She adds about Lily: “The poor creature can’t speak the truth even when she tries.” Maud’s suppressed rage over Lily had no real outlet except in her journals, and since they were intended for eventual publication, Maud had to be careful what she said there too, lest she give away more than she wanted to, rekindling any of Lily’s stories. In 1926, William Arthur Deacon’s attack on her writing had undercut her celebrity. Now, in 1927, this slip in the serialization could provide tinder for malicious gossips back in Zephyr.

When the glamorous Captain Smith had sailed into Norval as a dashing war hero, and was so obviously taken with her celebrity and her conversational skills, this was heady attention for the emotionally and intellectually starved woman she had become by then. Maud knew, as no one else did, that The Blue Castle, which had been such a joy to write, bubbled up from the high spirits that Smith’s admiration had engendered. She obscures the fact that Captain Smith provided a model for the heroine’s sexy and mysterious lover, Barney Snaith by all but erasing Smith from her journals. Yet, she left in many small similarities of the heroine, Valancy, to herself, not in the details, but in the fact that poor, plain 29-year-old spinsterish Valancy had been made to feel that everything associated with men and sex was shameful. For its era, The Blue Castle was quite an explicit book in its extremely subtle representation of sexual repression and then sexual satisfaction, helping it get excluded from some church libraries.

In 1926, while she worked on Emily’s Quest, fear of gossip became a running subtext in the entire Emily series.

In Emily’s Quest, Emily continues to pursue a writing career, but as Maud’s readers were not fully prepared for full-blown career women, there was little choice but to end the trilogy with her marriage. Emily chooses— from three possible suitors—the young man who has become a world-famous artist, Teddy Kent. He is internationally regarded as a “genius,” and every portrait he paints of a woman has something of Emily in it. This reflects another prevalent attitude: that women should live through their men. Emily’s immortality will come through Teddy’s achievements—a compromise, of sorts. (Frederick Philip Grove left an unpublished novel at his death that is built on the same theme.)

Readers pelted Maud with letters as she finished the novel; they weighed in on which suitor Emily should choose. Readers’ responses also reflected the changing times. Many readers felt uneasy over the possessive Dean Priest and worried that he might re-enter the picture. Teddy Kent was hardly a perfect choice either; some readers picked up on his self-absorption, noting that he is devoted to his own career and his art. Emily’s artistic abilities do not interest Teddy any more than they did Dean Priest, whose disparaging words were responsible for her destruction of her first novel manuscript. However, Maud had limited choices, and she married Emily off to Teddy Kent.

The intelligent and ambitious hired boy, Perry, is out of the question for Emily because of his low social status and his rough edges: he marries Emily’s friend, Ilse. And, in fact, much of the book’s focus is on Ilse, a high-spirited young woman who gets herself “talked about.” (Her mother, accused of having a lover, has been the subject of truly lurid gossip, but in the first Emily novel, Emily has a “dream vision” that ultimately proves this to be false.)

Maud freely admitted that Emily was based on herself. But she did not acknowledge that the wild and rebellious Ilse came out of another part of her personality. Ilse is a free spirit, the embodiment of the energy and lawlessness that Maud might have exhibited if Grandmother Macneill had not reined her in so tightly. And Ilse’s father is much like Maud’s—useless as a protector or guide. Maud was relieved when she finished the book in December 1926. It had been a chore.

In late 1926, Maud had many other things on her mind. The Scottish maid, Margaret MacKenzie, had turned out to be untrainable. Maids lived with the Macdonald family, ate with them, and were included in family outings (with their way paid), so it was important for them to be companionable. Fed up with Margaret’s surly behaviour, Maud fired her.

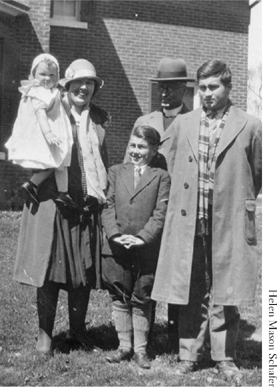

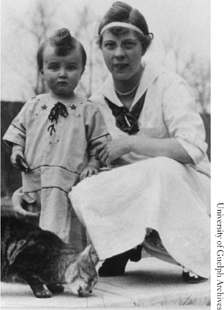

In January 1927, Maud hired Mrs. Mason, a widow with a young daughter named Helen. Mrs. Mason, like Maud, was a very private person. We do not know if she told Maud her story, but if she had, Maud would have felt sympathetic: it bore similarities to that of the heroine in The Blue Castle. Mrs. Mason (born Margaret Ruth Checkley), the favourite daughter of a very strict and authoritarian father with a large and successful farm near Arthur, Ontario, had run away with a farmhand from the neighbouring property, William Mason. Handsome and well dressed, he had come from England and taken a job as a menial worker in rural Ontario. He was middle-aged, received little or no mail, and told nothing of his past. People wondered if his name was really his own. Mrs. Mason fled her father’s wrath, either before or after she married (if she was indeed married), and the couple left for the United States. In fairly short order, Helen was born (June 21, 1925), and William Mason reportedly died of cancer—or so Mrs. Mason told Helen when she grew up. Either unwilling or unable to return home, Mrs. Mason brought her baby back to Toronto, taking refuge with a sister while she sought some means of support. With no one to look after her daughter, factory work in Toronto would have been very difficult. For Maud, life eased again with a good maid in the house.

January 1927 proved an eventful month in other ways. The new year began with a letter from Marshall Pickering’s lawyer, Mr. Greig, threatening to take Ewan’s unpaid debt to the officials in the Presbyterian Church in Toronto. Given that the Norval church was $300 behind in paying Ewan’s 1927 salary of $1,800. Greig could garnishee Ewan’s salary if he found this out.

The Macdonalds were puzzled over why the salary was in arrears. In early January 1927 the mystery was solved when a nervous John Russell came to them, in secret. John, the church treasurer, had been “borrowing” from the church funds. He told the Macdonalds that he had expected a windfall of $500 for injuries suffered in a job some time earlier, and had been borrowing against that for some time. The year-end annual meeting of Session managers was approaching, and he did not have the funds to replace what he had taken. If the fact that money was missing was discovered, the congregation would be in an uproar; even worse, those in the United Church would enjoy a laugh over the Presbyterians losing God’s money to a thief in their midst.

Rather than approach his own family, John Russell came to the Macdonalds and asked for a loan of the missing amount. That would pay Ewan’s salary and replace the balance before Russell was found out at the annual meeting. He promised to give Maud a promissory note to repay her when he could—in other words, probably never.

Maud was no stranger to the ironies of life. She had no choice but to lend the money, noting gallantly that whatever John’s motivations were, he had stood by the Macdonalds in the Pickering affair. John apparently felt no guilt over his “borrowing” church money, for he had firmly intended to repay it, just as he firmly intended to repay Maud. She grimly remarked that at least the situation would seal his loyalty to them. She had made $4,300 from royalties and investments in 1926, and would make $10,794 in 1927. She could afford to pay part of her husband’s salary in this roundabout way. Such a turn of events could hardly have pleased poor Ewan, but what could he do? If Maud did not help cover up the thievery, it would create a huge disruption in the church and scandal in the community.

In the meantime, Maud’s gift for “making things go” was energizing an entire community again. She organized a new fundraising adventure, the Olde Tyme Concert, a social event in which people dressed and performed as historical figures. Maud herself, appropriately costumed, recited “The Widow Piper.” In a time before television, these theatrical ventures not only provided entertainment, but also gave local people with talent a creative outlet. And they raised money for church maintenance and charitable projects. Sometimes the Olde Tymers took their performances to other churches.

In mid-January 1927, Maud went to nearby Guelph, and spoke to a capacity audience at a Women’s Club. The Guelph Mercury reported on her speech:

[She made a] fervent plea for the support of Canadian authors as the means of establishing a Canadian national literature. “Canadian authors, having competition from both England the United States, were,” she said, “at a disadvantage, and were frequently compelled to go elsewhere, in order to provide themselves with bread and butter and soap. If the departure of these young authors continues, there will never be a Canadian literature.” … “Literature is not a sporadic gift from a capricious God. It is a slow growth, and cannot spring from a sordid, petty, and materialistic people. To establish a national literature, our ideas must be noble and enduring, our culture real and profound, because genius is the ability to grasp and give expression to all that has ever existed in the inarticulate soul of a people.”

One might suspect that such high-minded sentiments would have bored the audience, but the report continued:

Mrs. McDonald [sic], who has an international reputation for her books, proved to be one of the most entertaining speakers ever heard locally. Her address was characterized by a brilliant wit, and a charming undercurrent of sly humour, which made listening to her an unalloyed pleasure.20

She finished off her address by reciting some of her own poems and reading some amusing letters from her male readers, particularly what she called “freak” ones: one man wrote about how much he enjoyed her writing, adding judiciously that he was married and only writing out of “pure friendship”; and a Kansas city lawyer wrote her that he had had a dream in which he’d met “Paddy” (a cat in one of her books) in Heaven. And a serious young divinity student in North Carolina enjoyed her books but complained that he feared that her practice of “marrying off all her characters” would bring contempt to the holy state of matrimony. She told the group that she had written this divinity student that if he preferred, she would have her characters live together without benefit of the marriage vows. Then she finished with a reading from The Golden Road.

This basic speech format she used over and over in small towns, and invariably the newspapers reported on what a good speaker she was. She kept people laughing—she was a witty storyteller, with perfect timing. She made a point of reading letters from male fans to offset the growing perception that her books were enjoyed only by women and children.

By early February, Maud was catching up on her letter-writing. She got letters off to her old pen-pals G. B. MacMillan and Ephraim Weber. She answered every fan letter, handwriting each in a standardized format: she was glad they liked her writing so much that they’d taken the trouble to write and tell her; getting letters from her readers all over the world was one of her greatest pleasures; and she regretted that she was so busy she could only pen a line or two in reply. Then she answered questions they asked and told them about her newest book.

Occasionally someone’s letter appealed to her, and she gave that person permission to write her once a year. To one such correspondent, a young man named Jack Lewis, she wrote in February 1927: “I am very glad my books have helped you to appreciate our world. But I guess the power of appreciation was there, though perhaps not awakened, or my books could not have put it into you.” She added that she loved Prince Edward Island “more than any other place on earth. Someday I am going to write a book about legends and sea-stories of the old North Shore. And that will be a book boys will like!”

To another young fan named Evelyn Johnston, she wrote that Emily’s story wasn’t hers, but the flash was. Then she copied out a long description of an imaginary place called “The Land of Uprightness,” which she had written earlier, in which she made note of climbing the “hills of firs” and looking “down over the fields of mist and silver in the moonlight.”

In this airy passage (the kind of fancy-writing that Modernist critics deplored, but which might have intrigued later Freudian critics), she merges the landscape of Cavendish, the Island (where there is a harbour), and the landscape of Norval, where, from Russells’ Hill, she could look down over the mists rising in moonlight above the forks of the Credit River. When the light was right, Norval was indeed a fairyland: there were times when this landscape produced in Maud the magical release of feeling that sent her imagination soaring, what Emily called “the flash.”

Maud repeatedly puzzled over how the pine trees on Russells’ Hill could transport her, and she reflected in her journal:

My love for pines has always been a very deep and vital and strange thing in my life. I say strange because there is nothing in my life— or this life—to account for it. There were no pines in my early home. Very few pines in P. E. Island at all. One or two each in the woods. Yet I always loved pines better than any other tree. And I wrote scores of poems about them; and now that I have come to live in a place that is rich in pines I find that those old poems were true and expressed the charm and loveliness of pine trees as well as if I had known pines all my existence … (December 23, 1928)

Balsam firs she had had in abundance in PEI, but not pines. She may have forgotten that, as a little girl of about ten or eleven, she had studied a prose piece called “The Pine” by the English Victorian art critic John Ruskin, which appeared in the Third Book of Reading Lessons in the Royal Reader Special Canadian Series:

The pine—magnificent! Nay, sometimes almost terrible. Other trees, tufting crag or hill, yield to the form and sway of the ground.… But the pine rises in serene resistance, self-contained; nor can I ever without awe stay long under a great Alpine cliff … looking up to its companies of pines, as they stand on the inaccessible juts and perilous ledges of the enormous wall, in quiet multitudes, each like the shadow of the one beside it—upright, fixed spectral, as troups of ghosts standing on the walls of Hades …

Ruskin goes on to describe the strength, shape, and power of the pines in this ornate rhetorical style, focusing on how Nature (and pines) can inspire the viewer.

When Maud read Ruskin in school, he gave her a “grand” way of seeing and responding to Nature. She, in turn, writing in her own style, taught millions of her young readers like Jack Lewis to see and appreciate and respond to the world of nature around them. Her word-painting provided filler, mood, and atmosphere in her novels, but it also gave aesthetic pleasure to many, taking them beyond the more prosaic realities of life. Other people in Norval looked up at Russells’ Hill and saw a few ragged pine trees. Maud saw the hill with its pines as a portal to another world—one of beauty, of enchantment, of inspiration. In practical terms, her way of describing nature brought a never-ending stream of tourists to Prince Edward Island. She would need this romantic and imaginary escape increasingly as the “wheel of things” began to spin faster and faster.

The real world always reasserted itself, bringing Maud back down from her rhetorical highs. In February 1927, eleven-year-old Stuart disappeared after going out ice-skating on the Credit River with a friend. Carried away with the glories of the “wingèd heel,” the boys had found themselves far from home when darkness fell and sensibly decided to walk home on roads, unaware that they were the object of a huge search. (A child could easily fall through the ice where the water was shallow and fast-running, especially after dark when the hazards were hard to spot.) Maud’s fright took a toll on her fragile nerves.

In addition, the L. C. Page and Company lawsuit dragged on. In early February 1927, the Master’s report had awarded her $16,000 of Page’s profits from Further Chronicles, but she knew that actually getting the money out of the publisher would be a long, expensive process.

Then, on the Island, the Campbells continued to need Maud’s help. Ella’s daughter Amy borrowed money to study nursing (she would become one of the few people who paid Maud back). Over the years, the hapless Stella Campbell had borrowed thousands for her wild schemes and repaid nothing. In Ontario, Maud had lent money to a Leaskdale widower, Will Cook (later Lily’s husband), who failed to repay her. And a friend from Leaskdale times, Mary Gould Beal, had borrowed money in 1925, and again in 1926, as her husband’s business suffered a downward spiral. Money issues were beginning to trouble Maud: Chester was attending an expensive private school, and she planned for Stuart to go there as well.

But there were happy moments, too. In April, Chester stood third in his class at St. Andrew’s, and he declared that he wanted to study mining-engineering for a profession (April 19, 1927). Stuart, still in Norval, was a constant delight to her. The Young People’s Guild play Maud had directed was a smash hit, bringing in $78 for the church. A New York theatre company took out an option on The Blue Castle. Anne of Green Gables was translated into French. Her royalties seemed better. And Norval’s natural beauty continued to be enchanting. With spring and summer coming, her spirits were rising. She wrote in her journals:

Norval is so beautiful now that it takes my breath. Those pine hills full of shadows—those river reaches—those bluffs of maple and smooth-trunked beech—with drifts of wild white blossom everywhere. I love Norval as I have never loved any place save Cavendish. It is as if I had known it all my life—as if I had dreamed young dreams under those pines and talked with my first love down that long perfumed hill. (May 26, 1927)

In July, Maud travelled back to her beloved Prince Edward Island, her first real vacation there in four years. While there, she received a letter from the Prime Minister of England, Stanley Baldwin:

10 Downing Street

19th June 1927

Dear Mrs. Macdonald:

I do not know whether I shall be so fortunate during a hurried visit to Canada but it would give me keen pleasure to have an opportunity of shaking your hand and thanking you for the pleasure your books have given me. I am hoping that I shall be allowed to go to Prince Edward Island for I must see Green Gables before I return home. Not that I wouldn’t be at home at Green Gables!

I am yours sincerely,

[Signed] Stanley Baldwin

Maud received this letter when she was visiting in Cavendish. Taking a walk into “Lovers’ Lane,” she read it “to the little girl who walked here years ago and dreamed—and wrote her dreams into books that have pleased a statesman of Empire. And the little girl was pleased” (July 14, 1927).

With the happy heart of a young girl, she went to a spot on the shore at Cawnpore to speak to a group of Campfire Girls. With surf pounding in the background, she told them old sea stories, including that of the Marco Polo, wrecked at that very spot. Yet changes were taking place in the Cavendish of 1927, and these changes did not please her. The Cavendish Presbyterian Church that had nurtured her as a little girl was now a United Church. The old manse where she had had so many happy visits with her friend Margaret Stirling was gone. The Macneill clan itself was disappearing—in her youth there had been twelve Macneill families, but now there were only six, and four of these had no children. The old community hall was in disrepair, and the books of the old library were unattended and mouldering. Carloads of tourists now descended on Cavendish, crawling about the haunts made famous by Anne of Green Gables. The inhabitants of 1927 Cavendish were losing the quiet rural quality of their village—as a result of her books.

Her Uncle John F. Macneill was now seventy-six, and the bad feeling between him and his famous niece still rankled. But she liked her Uncle John’s son, Ernest—a much gentler and kinder man—and she secretly hoped that the farm would stay in the family. (That wish was eventually fulfilled. Ernest’s son, John Macneill, born in 1930, inherited the farm, which remains in the family.)

During the summer of 1927, a Toronto writer, Florence Livesay, spent her summer holidays in Cavendish, largely as a result of Anne’s popularity. Maud knew her from the Toronto Press Club. Mrs. Livesay (wife of J. F. B. Livesay, general manager for the Canadian Press for Canada, and the mother of future poet Dorothy Livesay) was preparing an article on Maud, and queried how she got a start in such a remote and quaint place as Cavendish. Incensed, Maud snapped in her journals that she thought “the ‘literary atmosphere’ of the old Macneills and Simpsons would not have been too rarified for even Mrs. Livesay to breathe” (July 17, 1927).

The newspapers of late-nineteenth-century PEI demonstrate that the literacy level of Maud’s childhood culture was indeed impressive. It is to Mrs. Livesay’s credit that she saw the importance of the oral tradition in Maud’s writing. The Island newspapers crowed that “Mrs. Macdonald and Mr. and Mrs. Livesay are intimately acquainted, and there have been great ‘foregatherings’ at the shore during their present visit—nights of story-telling which will long be remembered by those privileged to be present.”21

When Maud returned to Ontario after this three-week visit in July 1927, Marion Webb came back with her. All of Ernest and Myrtle Webb’s children were growing up, and one farm could not support them all. Like so many other young Islanders, many of them would have to look elsewhere for a livelihood. Marion was a very pretty girl, with a sweet disposition and a good sense of humour. Both Marion’s mother and Maud wanted to enlarge her horizons by having her visit in Ontario.

Very soon after her return to Ontario, Maud attended the formal garden party in honour of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and the two princes, the Prince of Wales and his youngest brother, Prince George, held on August 6, 1927, at Chorley Park in Toronto. She bought a new dress of lace and georgette in a light cocoa-brown colour, with trimmings of brown and a brownish salmon pink. She wore a hat of leghorn straw, trimmed with a feather of burnt orange, and had a professional photographic portrait made of herself in this dress.

Ewan did not accompany his wife. He had gone for his own holiday on the Island, with his people. Maud went to the reception, met the royal party, and observed that the Prince of Wales (who would later abdicate the throne) looked “tired, bored, blasé, as no doubt he was and small blame to him,” considering that he had to greet four thousand people. She noted that of the two princes, Prince George was “far more chipper looking and seemed to be enjoying himself hugely.”22

Maud did not have to wait in the receiving lines; she was sought out by an attaché and was taken to the Honourable Stanley Baldwin and his wife for a chat of nearly half an hour. Another newspaper account called the length of the visit “a significant tribute at any time but the more notable under the exacting circumstances and one to stir the pride of the most unself-conscious.”23When Maud arrived home, she put away for her grandchildren the gloves she wore when she shook hands with the prince.24

When Ewan returned from Prince Edward Island, the Macdonalds bought a new “closed” car, a Willys-Knight, for $2,000. During September Ewan drove them around, showing Marion the sights of Ontario, such as Niagara Falls. Later in the fall, Marion returned to the Island. She was the kind of daughter Maud would have liked. Maud would miss her so much that she would encourage her to return later, changing the course of Marion’s life.

In early October 1927 Maud had another welcome visitor, her beloved old teacher Hattie Gordon, who was on her way to visit her married daughter in Philadelphia. Sadly, the talented Hattie was now a tired, impoverished old woman, divorced from an abusive husband, with children grown and dispersed. Maud noted that the entire world had changed in the thirty-five years since they had parted. “The girl of 1892 and the woman of 1892 have not met again. They do not exist. And in that realization lies my loss,” Maud wrote on October 14, 1927.

In mid-October 1927, Maud had learned that The Delineator, which had commissioned her to write four stories for them in January 1927, had changed editors, and the new editor, a man, had pronounced Maud’s stories about a child named Marigold “too old-fashioned.” They paid her the promised $1,500, but only as a kill-fee. She was deeply hurt and offended. This was one of the first indications that her writing was falling out of favour with more people than Deacon. It was one thing for critical tastes to change, but was the reading public going to change, too?

It was that November that the Countryman magazine came out with the error citing Barney Snaith as “Smith.” By her birthday on November 30, 1927, feeling battered on several fronts, Maud began obsessing about the past. Her work with the young people’s group had been extraordinarily successful for the past year, and she knew her depressed feelings were abnormal, but she could not shake them. When her Sunday School Bible class gave her a basket of roses at Christmas, she noted that Ewan turned away without a word.

In mid-December, she wrote in her journals that she thought we “are just entering … the age of Science—an age of wonderful discoveries and development.…” (December 17, 1927). Science did not yet understand affective mood disorder, or know how to treat it. When Maud felt depressed, she reread old favourites that suited her mood, like Nora Holland’s sentimental poem “The Little Dog Angel,” and Undine, the novel about a sea-sprite who is adopted by humans. Feeling estranged from her own world, she mused about the book, wondering what in it kept it from going “stale.” It was, she noted, a fairy tale, the sort of story at which the modern world may sneer, but without which people cannot live.

She looked at her son Stuart and saw a tender boy in a brutal world, and brooded that a future world might attack him, as she saw it attacking her (December 23, 1927). He had her personality—and her heightened sensitivity. Early in January 1928, Maud began to worry seriously about her own emotional fragility and the effect that a complete breakdown would have on her writing and her earning capacity. She tried unsuccessfully to call in some of her outstanding debts.

Maud had remained an active member in the Canadian Authors Association, which continued its fight to establish copyright laws that would better protect Canadian authors. Her feeling of Canadian nationalism had increased now that she lived in Ontario. (The Maritimes had always had closer ties with the New England seaboard than it did with Ontario or the rest of Canada.)

The extent of her growing financial insecurity after Deacon’s attack and the rejection of her stories by the new editor of The Delineator is evident in a letter she wrote to the Toronto novelist Katherine Hale on January 9, 1928. Maud told Katherine that she was rereading her husband John Garvin’s Canadian Poets and had come across a poem of Katherine’s there. Maud thanked her for its beauty and poignancy.25 This letter was a well-calculated piece of flattery: John Garvin was an aging but still influential fixture in the CAA. He was an anthologizer of Canadian literature, and he was exceedingly proud of his wife. He was also the chief organizer for the CAA’s fifth annual Canadian Book Week.

In February 1928, Maud spoke at the CAA meeting in Toronto. (She was amused when Garvin, a good-natured windbag, told her that he was responsible for the publication of the Canadian edition of Anne of Green Gables—at that time, there had not yet been a Canadian edition of Anne.) But in her journals, Maud compares John Garvin, who had such pride in his wife, with Ewan:

Ewan secretly hates my work—and openly ignores it. He never refers to it in any way or shows a particle of interest in it. I certainly wouldn’t want him to go about boring people publicly with his appreciation. But I would like him to feel a little. I have never, since I was married, neglected any duty of wife or mother because of my writing. I have done it at odd hours that were squeezed out of something else by giving up some of my own possible pleasure and all my leisure. So he has no justification for this attitude.

However, let me be just. Would I want Ewan to be like old John Garvin in other respects? I certainly would not. Therefore let me not howl with indignation because he is not like him in this. (February 12, 1928)

Maud was resentful. In the previous year, her income had been six times that of Ewan’s. With money made by the plays she had put on, the drama group had re-covered the cushions on the pews of the church auditorium, brought its Sunday School room a piano, and paid for the installation of electric fixtures. These were substantial achievements. But she knew that reason did not control human emotions.

Since coming to Norval, Maud had put forty pounds on her tiny frame. Women then did not mind a matronly, well-fed look. When they carried themselves well and dressed elegantly, it could make them look substantial and imposing, as was the case with Mrs. Barraclough. But the extra weight sapped Maud’s energy. She tripped and hurt herself and took a number of weeks to recover in spring 1928, just when her young people were going to other towns to put on the play she had directed.

There was a bright spot in her spring—Chester had led his class at St. Andrew’s. This allayed immediate fears about his behaviour and development. Soon another worry arose, however: the Barracloughs wanted to move to Toronto, so tried to sell the woollen mill Ernest owned. In the end, Ernest could not find a buyer, so they stayed. The Barraclough house had always been a sanctuary for the Macdonalds. They could count on Ernest and Ida to respect confidences when they talked over personal problems with them, especially their concerns about Chester.

Maud’s spirits always rose with the first signs of spring. By June 1928, she was out in her garden again, feeling better. Ewan took off for the Presbyterian General Assembly in Winnipeg that year—a measure showing that he, too, was doing well. In the last three weeks of June, Maud spent three days in Toronto, again at the Triennial of the Canadian Women’s Press Club. Back in Norval, she entertained Alf Simpson of PEI, Ed’s more likeable brother.

Chester came home for the summer, proud of his academic achievement at school, but still clearly not well adjusted socially. The students at St. Andrew’s had nicknamed him “Rat” (for stealing and eating). All the Norval young folk laughed about the nickname. Maud’s maids over the years had all found his compulsive overeating frustrating: a maid was supposed to keep the cookie jar filled at all times, but Chester would eat an entire platter of cooling cookies at a sitting. He would smell the baking, sneak into the kitchen, steal the cookies, and then deny the theft. One incensed maid grabbed him and turned the pockets of his pants out to demonstrate through the crumbs that he was lying to her. But none of the maids over the years felt comfortable complaining directly to Maud about him, and if they had, it would have done little good. No one could control Chester.

In the summer of 1928, trouble began brewing between him and Ewan. A cryptic comment about Chester spilled into her diary: “something nasty and worrying that embittered life for many days and filled us with deep-seated fear of his future.” She could not bring herself to give details: “There is no use to write much about it—no use tearing open a wound that has begun to skin over. But I have been very wretched over it and I cannot think about it without agony” (July 22, 1928).

The maids reported that his behaviour was unpredictable. When greeted in the morning, or whenever he came into a room, he might answer; but other times he rudely ignored their existence. When he was caught lying or smoking, he alternated between pretending to be extremely contrite and being angry and rebellious. Apologies and promises came easily, but Chester was caught again and again in lies. Most impulsive children (as Maud herself had been) reached an age at which they began to think about consequences and modify their behaviour, but he did not.

Chester’s sexuality continued to be a concern. Although self-gratification and self-exploration is common with adolescents, in his case masturbation caused increasing distress. A maid or anyone else was in danger of accidentally stumbling in on an embarrassing sight. Stuart quit sleeping in the room he shared with Chester and moved outside to sleep in a tent, except in the winter.

Chester’s behaviour around local girls was also causing alarm. According to his contemporaries (interviewed in the 1980s), young women in the community of Norval were very wary of him. Maud watched, paralyzed with mortification, unable to write or talk about it. When she was growing up on the Island, one of the behaviours for which people were placed in Falconwood, the mental institution, was public masturbation.26 Ewan’s increasing anger over Chester’s behaviour may have reflected his memory of his own past—of his own sexual development, including his alleged window-peeping in Cavendish. Ewan was all too aware of the Bible’s pronouncement: the sins of the fathers will be visited on the sons for many generations. Ewan saw this son as re-enacting the sins of his father, either imagined or real. It was an increasingly tense household.

In the athletic culture at St. Andrew’s, Chester had remained an outsider, given his stiff and corpulent physique, lethargic disposition, general untidiness, and surly nature. He was also lazy about studying, but could do well academically in spite of a lack of motivation. Good grades did not endear a teen to a peer group that had already excluded him on other grounds. An outsider at school and an irritant at home, he was growing up an isolated and lonely young man.

At home, he constantly annoyed the maids, but he aggravated his father even more. Ewan had never spent much time with his sons, either talking or playing with them, and he had not built up a fund of goodwill and trust. Frustrated by Chester’s behaviour, Ewan closeted himself more and more in his darkened study and brooded. In private, he complained to Maud about Chester—as if she could do something about this difficult son.

Friendless, Chester mostly stayed in his room and read. By 1928, when he was sixteen, he had solidified into a churlish loner who carried a lot of resentment—resentment towards a world that seemed to shun or dislike him; resentment towards the father he resembled; resentment towards a mother who was consumed by her own busy world of reading, writing, and church and social activities, whose interaction with him was full of frustration; and resentment towards a younger brother with a sunny disposition who was surrounded by friends.

Stuart played well with other children and had never been a problem; in Norval, he loved the river and spent most of his time there with the village youngsters. Stuart, unlike his father and brother, was very sensitive to his mother’s moods. She noted in her journals that when she felt “down,” Stuart would attempt to cheer her, for example by making her a cup of cocoa (February 14, 1928). Stuart loved sports and the outdoor life, and, left to his own devices, he was always busy, happy, and interacting with friends. The sedentary Chester’s jealousy of Stuart increased.

A new kind of narrative began reasserting itself in Maud’s consciousness, and in her journal. She began to obsess that fate had put a curse on her and those she loved. She had lost both her parents; she had lost her cousin and best friend, Frede, to premature death; she had married a man who became afflicted with intermittent mental problems; and now her older son seemed seriously troubled. In depressed moods, she revisited her negative thoughts. Why, she would ask herself, must everything she loved be cursed? The depth of her worry about her older son shows in the fact that she started to bring another theme into her journals, recounting in detail how others’ children had disappointed them.

Maud soon had another jolt. Stuart was an excellent swimmer, but in July 1928 he had a narrow escape in the river. The Norval dam broke and he and his friends were swept over onto the sharp rocks below. They were bruised, but no lives were lost. This was the second scare over Stuart and the river, and Maud began obsessing that something was going to happen to her one “good son,” as she began calling him. She felt that there would be a third catastrophe, just as Frede’s third illness had carried her away.

Soon after that, a truly terrible tragedy occurred in the village, emphasizing how quickly lives could be snuffed out. The Macdonalds’ neighbour, George Brown, had gone up to his farm with his children in the car, and he’d inexplicably driven directly in front of a radial railway train at the crossing. His three children—aged ten, eight, and five—were all killed by the collision, and the father was badly hurt. Stuart witnessed the entire tragedy and ran to help, but found only badly mangled bodies. The town was stunned and paralyzed.27

That summer the church had undertaken some construction on the manse to improve the bathroom. Ewan, preoccupied and inattentive at the best of times, fell headlong into the trench the workman had dug for the sewage system. He was shaken up, but not otherwise hurt. Ewan was frequently absent-minded (like the lovable Reverend Meredith in Rainbow Valley), and car accidents were becoming more common. Maud arranged for Chester to take driving lessons that summer. She wanted a second chauffeur in the family, and she hoped driving would help Chester to become more responsible.

To revive themselves, in early August the Macdonalds took a mini-vacation, motoring with the Barracloughs to Orillia, Muskoka, Cobalt, and North Bay, travelling on the new Ferguson Highway, and returning via Port Carling and Bala. It was a refreshing vacation, if short. Again, as in 1922, Maud lost herself in her reveries over the beauty of northern Ontario.