From 1929 to 1935, Maud’s writing life continued to reflect her lived experience—particularly her emotions—refracted through her imagination into stories. She found pleasure, as well as release from her troubles, by creating the more tranquil mental space in which she wrote. In the Norval years, the act of writing moved from being a source of pleasure to a therapeutic activity.

Maud was always happiest when she was writing, living in the imaginary world of her characters, where she controlled everything. She was amused by her characters, with their full range of eccentricities, prejudices, and human limitations. Her sense of humour kept her laughing at the misadventures and comical ironies in their lives. She might temporarily lose her sense of humour about her own life, but she could always laugh over her characters. They always grew out of the human nature she had observed, and her female protagonists were always fashioned out of some elements in their very complex creator.

She had written happily and furiously on A Tangled Web all through 1930, finishing her first draft in September. It was a very complex and densely plotted book, aimed at adults. It reconfigured the memories of her own youth, recalled through laughing with Nora over their escapades in Cavendish, and mixed these with the on-again-off-again romance of Marian Webb and Murray Laird.

On one level, A Tangled Web is a humorous study of love and romance in a series of intermarried clans like those in PEI or Ontario. The character who precipitates the action of the novel is a manipulative and cantankerous old woman, Aunt Becky. The novel opens with a meeting she has called to discuss the inheritance of a family heirloom (a decorated antique jug), in advance of her imminent death. Aunt Becky says she may leave the jug to family members, on certain conditions, or she may not: they will have to wait and see. Her instructions will not be revealed for a year. The community is stirred into frenetic agitation, facing the suspense of who will ultimately be the “chosen” one. Everyone attempts to lead an exemplary life for the next year.

Given that greed motivates everyone, the result is a community edginess that precipitates feuds, romances, re-alliances, and general mayhem. All is handled with a comic touch, and the main players are characters whose love affairs keep readers laughing. At the end, just as the contents of the will are to be revealed, it turns out that the will has been lost, accidentally dropped by the person entrusted with it, and most likely eaten by his pigs. And before anyone inherits the jug, it is smashed by the deranged “Moon Man.” Maud has had a good poke at folly in human nature; or, in theological language, she has shown that “all is vanity” in this world.

On another level the book shows characters twisting their reality out of shape by obsessing about an unknown future, something Maud knew that she herself often did. On yet another plane, Aunt Becky’s will creates a situation that mimics the doctrine of Predestination. Because these characters, all caught up in a “tangled web,” do not know what is “written” about their future, they spend all their time trying to keep their credentials intact. Many mess up their lives in the process.

The book was finished right before Maud went on her trip to Prince Albert and the west.

In the years following the publication of A Tangled Web, Maud’s domestic situation did not grow any easier. The economic depression worsened throughout the 1930s, with Maud losing ever more money. Ewan’s salary barely covered basic family expenses. Her sons and their romances kept her on edge. Her asthma grew much worse, and was at times life-threatening. The seemingly endless church events began to wear on her nerves. When she was asked to take on a Sunday School class in the Union church at Glen Williams, she complained in her journal that parishioners expected too much, evidently thinking to themselves, “What do they pay a minister a salary for, if his wife won’t work all the time for them?” (January 9, 1931). In July 1931, Maud wrote an article for publication in the October issue of Chatelaine. Entitled “An Open Letter from a Minister’s Wife,” it is revealing as a self-description, and it shows her frayed nerves:

If at times the minister’s wife is a bit absent-minded or preoccupied or “stiff,” the congregation should not imagine that she is unfriendly or uninterested or trying to snub them. She has a right to expect that they make a few excuses for her. Perhaps she is so tired that she is not quite sane; perhaps she is one of those people to whom it is torture to show their feelings—dead and gone generations of sternly repressed forefathers may have laid their unyielding fingers of reserve on her lips; perhaps she is wondering if anyone could sell her a little time; perhaps there are many small worries snapping and snarling at her heels; perhaps she has had one of those awful moments when we catch a glimpse of ourselves as we really are; perhaps she has the odd feeling of not belonging to this or any world, that follows an attack of flu; perhaps she is just pitifully shy at heart. Or her own feelings may have been hurt. Because minister’s wives have feelings that are remarkably like the feelings of other women, and injustice and misunderstanding hurt us very keenly. (October 1931, Chatelaine)51

When Maud was asked to judge a speech contest and pleaded that she was feeling unwell, a female parishioner told her: “You’ll have to give up writing, Mrs. Macdonald.” Maud fumed. Her normal diplomacy failed her, as her journal account shows: “Half my worry this winter is that I can’t find time to do my own work. I glared at the little fool and permitted myself the luxury of a biting retort. ‘No, Mrs. Sinclair, I shall not give up my writing. But I do intend to give up running all over the country doing other people’s work for them.’ ” She added in her journal: “Oh, I can tell you I licked my chops over that” (January 9, 1931).

But in the third week of January 1931, she pulled herself together and gave “a most unusual paper on the well-known and sometimes loved and often hated little animal, the cat,” at the Brampton Literary and Travel Club.52 And she continued to publish, out of financial necessity.

In February 1931, she published a story in the Canadian Home Journal called “The Mirror.” It is built around a 120-year-old mirror that hung in a home inherited by the heroine, plain, shy Hilary (whose description recalls Maud at a younger age). The mirror, with unique magical powers, reveals the truth to whoever looks into it.

In mid-February she spoke at the Toronto branch of the Canadian Authors Association, reading from her new book. She chose a chapter about the Island clans that, one newspaper reported, “provided rare enjoyment.”53 She explained to the audience that there had been much trouble finding a name for the book, and joked that Donald French was staying up nights reading the Bible to find a title for it, and “even if he doesn’t find one,” she added, “it will do him good.” Three days later, she directed the annual Old Tyme Concert in Norval, said to be the “greatest success ever,” filling every seat in the Anglican hall to the back steps.54 In June, she attended the CAA convention in Toronto as a delegate, attending a full round of luncheons, receptions, dinners, and meetings with other authors. Along with Nellie McClung and the novelist Madge MacBeth (“Gilbert Knox”), she made an address.

In July through September 1931, Maud continued in high-profile activities. She was a judge for a Kodak photography competition held in Toronto, along with other well-known people like Nellie McClung, “Janey Canuck” (Judge Emily Murphy), Wyly Grier (a well-known artist), Canon Cody (prominent clergyman and chairman of the board of governors at the University of Toronto), and Colonel Gagnon (managing director of Le Soleil, and vice-president of the Canadian Press). The competition gave Maud a psychological lift. She wrote a high-spirited entry in her diary on the day after she learned she was to help judge, for the other judges were Canada’s elite. She was particularly pleased when her arguments decided the winning picture: the silhouette of a Canadian prospector and his pickaxe seen against the darkening sky. She was presented with a moving-picture camera for her services. Her mind was already on the subject of memories: “I hate to think of all the lovely things I remember being forgotten when I’m dead!” (July 11, 1931).

At this time, she was recopying her handwritten journals by typewriter (partly so each son could have a copy), and she had come to the Herman Leard story.55 Amid all her activities, and her soul-searching in her own journals to understand the intensity of her former attraction to Herman, she fielded the pesky Isabel, eyed Chester for signs of mental instability, and agonized over Stuart’s fondness for Joy. She kept up her speaking engagements through the autumn of 1931. In October she went to Montreal to make several appearances. On this trip she confided to her journal that “It is not a disagreeable sensation to be lionized!!” (November 27, 1931). She took heart in every confirmation that she was still respected in a literary world where styles were changing fast, where critics were attempting to remould popular taste.

The Canadian novelist Raymond Knister (1899–1932) wrote an article around this time that demonstrates Maud’s disappearance from the literary screens of young Canadian critics. Entitled “The Canadian Girl,” it begins:

Why is it that though Canadian authors are known and read the world over, one cannot think of a single heroine who lingers in the memory …? The long line of English romance and fiction reveals a prodigious gallery of charming creatures, and American literature, though younger, can boast its own types. But why have we no such thing as a fictional character who is at once convincingly real, convincingly charming, and convincingly Canadian?

Anne, who had enchanted millions of readers worldwide since 1908 and created a tourist bonanza for the province of Prince Edward Island, had not impressed Knister.56

Still, Maud retained her readership, but she also was under pressure to continue producing books to avoid a drop in income. In 1930 she had earned $8,314 from book royalties, reflecting the sales of Magic for Marigold (which were mostly achieved before the effects of the stock market crash were fully felt). But she brought out no new book in 1930, so in 1931 her book income was only $1,897. It rose in 1932 to $4,805, thanks to A Tangled Web. But A Tangled Web—by far her most ambitious book to date, and one aimed at adults—did not sell as well as earlier novels. Was this because she was locked into a children’s market, or because of people’s obviously diminished buying power in the Depression, or were her books finally going out of fashion? She felt nervous.

Political events and allegiances were changing too. Maud alludes in her journal to “Red Russia” and the “Red menace in Spain and Germany.” In 1932, she wrote of her mother’s and grandmother’s generations:

They lived their lives in a practically unchanged and apparently changeless world. Nothing was questioned—religion—politics—society—all nicely mapped out and arranged and organized. And my generation! … Everything we once thought immoveable wrenched from its pedestal and hurled to ruins. All our old standards and beliefs swept away—our whole world turned upside down and stirred up—before us nothing but a welter of doubt and confusion and uncertainty. Such times have to come, I suppose, but woe to us whose kismet it is to live in them. (January 24, 1932)

Like so many others, she felt disoriented by the speed of change.

Maud knew she must get hold of herself before she could begin writing again. She began rereading her old favourite novels—the nineteenth-century Scottish “kailyard” novels, like Ian MacLaren’s Beside the Bonnie Brier Bush (1894) and The Days of Auld Lang Syne (1895). She found in them much the “same flavour” as her childhood in Cavendish, “the memory of which is like a silvery moonlight in my recollection” (January 24, 1932). Around this time, she wrote a whimsical short story that dealt in a way with a parent interfering with a young person’s choice of mates—something she was doing herself with both Chester and Stuart.57

Following A Tangled Web, which had been a massive effort, Maud was distracted over her family; finding a good idea for her next novel was not easy. In the May issue of Chatelaine, she published a sentimental story called “The House.” The heroine is a lonely, dreamy, plain child—as Maud envisioned her own childhood self—and this child fixes her love on a house. The story grows out of Maud’s love for places and homes, like the home of the Campbells in Park Corner, where she had felt so welcome in her Aunt Annie’s unconditional love, and where everything always seemed joyously the same. The Campbells might have been on the verge of disaster, but they could always gather round the organ and sing, or entertain each other with funny stories. The more Maud thought about the unhappy state of her own home in Norval, the more she looked back to the homes she had left in Prince Edward Island, even the “old home” with her grandparents. The symbol of a house would become her chief figure in her next book. She started writing Pat of Silver Bush at the beginning of April 1932.

Maud had reread her journals until she could fuse the memories of her own childhood with the anxieties of the fifty-nine-year-old woman she was now. From this grew a new heroine, Pat Gardiner.

Maud finished the book at the beginning of December 1932, and typed it up herself in the following twelve days. She dedicated Pat of Silver Bush to Alec and May Macneill and the “Secret Field,” in memory of a happy walk in October 1932 (November 13, 1932). She was exhausted by the time she finished.

This novel is built on the theme of Pat Gardiner’s extreme attachment to her home. The central events in the novel are the threats to her happy and unchanging life in Silver Bush, including a new baby in the family, starting school, the marriage of an aunt, her father’s thoughts of selling up and going west, and her older siblings’ departures or courtships. Pat’s leitmotif from age eight to eighteen, the time span of the novel, is her hatred of change, particularly as it threatens her beloved old-fashioned family home, “Silver Bush.”

As has been noted, Maud had two sets of mythologies about her own childhood. The first was almost factually accurate—that she had a comparatively happy childhood being raised by her grandparents in Cavendish, a settled rural community, where she had plentiful playmates and extended family. The second, a less true but more compelling myth, is the one recorded in her diaries around 1905—that she was a lonely, solitary, and misunderstood child who was all but orphaned when her mother died and her father left her to be raised by her unsympathetic grandparents. Maud drew on these two mythologies to fashion her two primary child characters in this novel, Pat Gardiner and her friend, Hilary Gordon. Pat Gardiner is the child of the first mythology; Hilary Gordon, a boy whose mother has abandoned him, is heir to the second.

Many of Pat’s characteristics are similar to those of the young Maud Montgomery. For instance, in Chapter One we are told that Pat is a “queer,” emotional child, who loves more deeply than others—and this capacity for deep feeling is accompanied by both intense delight and intense pain. Pat worries unduly over her looks, too, believing that she is ugly. She does not have Maud’s youthful exuberance or her creative gifts, but she draws much else from Maud.

Pat’s best friend, Hilary (“Jingle”) Gordon, is a lonely little boy effectively orphaned when his father died and his mother left him to be raised by relatives, so she could go west and remarry. Hilary idealizes his absent mother for his first fifteen years, and is crushed and disillusioned when they meet. This recalls Maud’s experience at age fifteen, when she was summoned out west to join her father—only to discover that he wanted her there to help his peevish new wife with her housework and babies.

That a parent may not love its child at all is a devastating recognition for a young person, and it is powerfully portrayed in this novel.

As she continued to recopy her journals in the handwritten volumes, Maud had been thinking a great deal of her own father and stepmother. Unlike Maud’s father, Hilary’s self-absorbed mother is sufficiently well-off to arrange for his education, but she does this out of a sense of obligation, not love. (Maud’s father had sent a modest sum of money for her only when her grandmother strong-armed him to do so.) At least Hilary can fulfill his dream of becoming an architect of beautiful houses for the enjoyment of others. He finally realizes that he must develop his career for his own satisfaction, not to satisfy his shallow mother, who takes no interest in his professional success.

For a time, Pat has another good friend, a girl her age named Bets Wilcox. Bets is perfect, beautiful, and shadowy. Such clues suggest that she is marked for death, just like the too-perfect Beth in Little Women. Bets Wilcox dies of flupneumonia, like Frede a decade earlier. Pat asks the very same question in the novel that Maud asked when Frede died: “How was one to begin anew when the heart had gone out of life?” … “Bets seemed to die afresh every time there was something Pat wanted to share with her and could not” (Chapter 31).

Even with its child protagonists, Pat of Silver Bush hardly seems a traditional story for children. Most children want to “grow up,” and they enjoy the excitement that change brings. Pat’s emotional makeup seems highly neurotic, like Barrie’s Peter Pan. Maud’s sense of being disoriented by the ceaseless post-war change was shared by many adults, but when transplanted into the emotions of a small child who is strikingly articulate about her hatred of change, it seems oddly pathological. However, the novel does catch the Zeitgeist of the era, as experienced by many adults.

Although the rather uninteresting Pat lacks Anne’s ginger or Emily’s spunk, Maud compensates by giving the Gardiner family an Irish servant named Judy Plum, who is full of stories, fairy-lore, and smart answers for everything. Judy gives the house most of its personality, and her stage-Irish brogue may be drawn partly from the descendants of Ewan’s “warm” Irish settlers who still attended the Union and Norval churches, and partly from popular plays by Irish writers like Sean O’Casey and W. B. Yeats.

Maud knew how to create atmosphere, and the novel is engaging. The ambience and warmth of the Gardiner home comes through the multiple comforts in Judy’s kitchen, the antics of the many cats, the scenes where extended family and friends sit around on winter evenings spinning tales of family and community. Small frictions and spats maintain narrative interest.

Maud would write to a young fan about Pat the following year: “My characters are all fictitious, as people, but I have met the types to which they belong. I gave Anne my imagination and Emily Starr my knack of scribbling; but the girl who is more myself than any other is ‘Pat of Silver Bush’—my new story which is to be out this fall. Not externally but spiritually, she is ‘I.’ ”58 And Pat was her at this point in her life, (as well as Hilary Gordon) just as Anne, the Story Girl, Emily, and Valancy, had been in turn.

Maud had always dreamed of creating a happy home, like that of her merry Campbell cousins of Park Corner, but her dream was failing to materialize. Too many things in her personal life were under threat in the 1930s: her financial security, her professional status, her husband’s mental health, and her sons’ stability and future. She saw more wars brewing in a world where war had become “a hideous revel of mechanical massacre” (February 25, 1932). She feared more and more for her own state of mind. In Pat of Silver Bush she depicted the happy home she wanted for her family, and she mapped the ways that people must adjust and move on when life disappoints them. But she was finding it hard to do this herself.

Still, no matter how she felt, Maud kept up her professional obligations— her writing, her speaking engagements, and her reply to every fan letter. She reacted strongly to a letter that came to her in July 1933, from a bright young reader in Saskatchewan named Roberta Mary Sparks. Roberta wrote Maud that she loved her books, but she thought her characters were unrealistic— they were too idealistic and too faultless as people. Already smarting under certain critics’ insinuation that her books were sentimental, Maud wrote sharply to Roberta:

Do you think Anne was happy when her baby died—when her sons went to the war—when one was killed? … Poor Valancy had 29 years of starved existence and Emily had her bitter years of alienation from Teddy.… You are probably much more cynical at nineteen than you will be at forty. I am sure there are plenty of girls and boys just as good and true as any of those in my books. I have known ever so many. Of course there are plenty of the other kind, too—always have been and always will be and just now they are not repressed as they used to be and we hear and see more of them. But the other sort must have always predominated or the world wouldn’t have gone on at all. (Letter of July 4, 1933)

Roberta felt the sting of Maud’s forceful response, and did not answer the letter, feeling that she had said the wrong thing to an author she loved, and doubtful that she could explain what she had meant. Roberta had indeed hit a sore spot: in Chester, Maud had one of the “other kind” of young people who were not “good and true,” and she had no idea how to cope.

On December 2, 1933, Chester and Luella Reid confronted Ewan and Maud with surprising news: Chester claimed that he and Luella had been secretly married the previous year, in November 1932. They were twenty-one and twenty-two, respectively, at the time of the announcement. Chester had many years of schooling ahead before he would be a lawyer and able to provide for a family. Luella Reid was clever but lacked any education beyond high school. Maud and Ewan were devastated. To the alleged marriage date, Ewan’s response was to say, over and over, “I don’t believe a word of it,” and it was, of course, a lie.

The diminutive Luella was too mortified to speak, for she knew, and her new in-laws also knew, that such a marriage could mean only one thing— that a baby was on the way. In that era, pregnancy outside of marriage was the worst shame a respectable girl could bring on her family. It was almost always blamed on the woman—women were supposed to be “purer” and better able to exercise self-control than men. People assumed that a woman who got pregnant outside of wedlock was either of low morals or was determined to catch the man by “hook or by crook.” She would carry a stigma for life, even if marriage followed, and the children born in a “forced marriage” also bore a lingering stigma.

Maud knew the power of sex as a component in the makeup of human beings. She said that she always tried to answer the boys’ questions about sex as honestly and openly as she could. She recalled how sex had been a taboo subject in her childhood, something too “vile and shameful to be spoken of” (January 11, 1924). She recalled a doctor’s book in the Macneill household that explained sexual functions clearly but was kept hidden from her—with the result, of course, that she dipped into it “by stealth.” She gave Chester such a book to read when he reached puberty, and she remarked that the “present generation” had “saner views” on sex than earlier ones. When she was writing the second Emily book she could still not bring any hint of physical love into her novels. She was branded as a wholesome writer for the young, and sex was still a taboo subject in fiction for them.

Maud’s advice to Luella after their marriage reveals the traditional attitudes towards sexuality in that era. In keeping with her promise to Luella’s dying mother to be a “mother” to Luella, Maud took Luella aside to talk about a woman’s proper conduct after marriage. According to Luella, she advised her never to let her husband “see her body naked,” telling her that she should “always undress behind a screen.” Maud explained that this would help keep the “mystery” and “magic” in marriage, and that too much familiarity was a bad thing. Luella, of a different and later generation, found the advice amusing, given that she was married and pregnant.

Luella recalled that Maud herself kept a screen in her own bedroom and dressed and undressed behind it. It was large enough to afford complete privacy. Luella observed that Maud and Ewan were both middle-aged when they married, and she said both were very prudish, Ewan far more so than Maud. Luella said that she could not imagine Ewan “ever trying to get ‘peeks’ ” at his wife’s body when she undressed, and she doubted he had ever actually seen Maud naked. Women’s nightgowns then were voluminous to protect against the cold in badly insulated and poorly heated houses. Even in summer, nightgowns were roomy enough to undress under if a woman did not have a screen. Describing all this later in her life, after she had read many Victorian novels and histories, Luella smiled over Maud’s Victorian views about modesty, but she said they were not unusual for women raised in Maud’s generation.59

Maud made all the decisions after the 1933 marriage was revealed. Chester had to continue his schooling. He would continue to work in the Bogart law office, and then take his law courses. Maud found and furnished an apartment for Chester and Luella on Shaw Street in Toronto where she hoped they could be a normal, young married couple, with their indiscretion kept secret. Maud agreed to support them financially through Chester’s training, but on the condition that there would be no more babies until Chester could provide for them.

Chester’s “forced marriage” was particularly hard for Ewan. For the son of a minister of God to get a young woman pregnant was scandal enough, but that the young woman should be the daughter of one of the church’s elders put it beyond the pale. Maud and Ewan tried to save face by placing an announcement in the Brampton paper that said the secret marriage had taken place in 1932, the previous year, just as Chester and Luella had presented it to them. The paper, however, printed the accurate marriage date of 1933. The community was abuzz. Ewan and Maud were so humiliated that they could hardly bear to appear in public.

Chester’s marriage undoubtedly stirred up Maud’s old memories about her own youthful reputation as a high-spirited girl. Maud was a woman who lived in memories, and whose earlier humiliations were never forgotten. She had learned to control her impulsiveness, but she must have worried that she had bequeathed that trait—some “bad blood,” so to speak—to Chester. Chester’s disgrace opened old wounds, and Maud’s fame only intensified her misery. A child’s indiscretions did reflect on the parents in most people’s minds. Slowly, surely, the pernicious idea that everyone she loved deeply was doomed to failure began to deepen its reach in her mind.

From 1933 to 1936 she put her journals aside, too upset by events to face them and write out her humiliation. She had so much trouble sleeping after December 2, 1933, when she learned of Chester’s marriage, that she turned again to Veronal, a widely used barbiturate prescribed by doctors as a sleep-aid and sedative. (It was one of the medications that she and Ewan had been given in Leaskdale for anxiety.) When she resumed her journalizing again, three years later, she would reconstruct a long retrospective entry from notes she had made.

Ewan fared even worse: for him, Chester’s marriage sparked a major depressive episode. Ewan had been comparatively well for most of the Norval period. He had had some small depressive episodes, but mostly he had been preaching effectively, and was quite fondly regarded by his two congregations, especially after his research into the history of the local Presbyterian churches. His even temper cooled down antagonisms. But after Chester’s marriage, Ewan also began to succumb to his old demons, his own idée fixe.

His demons again told him that the corruption in his own home proved that he was not one of the “Elect,” and that he was doomed to Hell—along with the son who so resembled him. Ewan began to brood once again, telling his already distraught wife that he was not fit to minister to his flock when he himself was an outcast from God. Why else would God let this disaster happen? Ewan knew his Bible well, especially the many Old Testament references to the “iniquities of the fathers” being visited upon the “sons to the third and fourth generation.”60

Ewan began to change. He had trouble carrying out his regular visitations, and he sat for long, solitary hours in his darkened study, ruminating, and feeling his estrangement from God and everything positive in his life. He would rise in the morning, dress in his heavy, stiff clerical garb, eat his way through a large breakfast, and disappear into his dark study until the midday meal. He would emerge, eat a heavy meal again, and then return to his study for the afternoon. At the evening meal, he re-emerged, looking dishevelled, moody, closed off, and miserable. He would eat a big meal in silence, and return to his study. His sunless study was intrinsically gloomy, with nothing but theological books on the shelves. He became increasingly self-absorbed and spoke little. No doubt Maud’s anxiety and discouragement affected him. Perhaps they fed off each other, locked as they were in their own prisons of unhappiness. Maud gritted her teeth, kept up her public face, and suffered terrible headaches in private. Ewan dissembled less well in public, and he increasingly took sedatives prescribed by his doctor to help him cope.

One document written by Ewan during this time remains. It is a set of jottings about the men in his parish. These notes are the work of a man brooding destructively. He names and characterizes many of his parishioners. For example, of Robert Reid (Luella’s father) he says: “Explosive and flammable temper— hardly ever under control. Offends people and doesn’t see how he does it and when it is pointed out to him says he was only doing his duty. Has a high idea of his own importance, and very intolerant of other people’s ideas.… The good he does is neutralized by his ill-considered utterances and the impression his whole personality makes …” Of George Gollop: “A conceited egotist. Thinks everyone should realize that he is a great man. Selfish and dogmatic. Unforgiving to a great degree.” The younger men in the congregation, those born between 1896 and 1905, fared better. Of Murray Laird: “Fine young man—intelligent— not perhaps as aggressive as he might be but in this respect he will grow. Fair-minded, tolerant, popular. Calm in expression and steadfast in purpose.”

Luella would later recount a memory of having dinner with her new in-laws during this period. Ewan had been sitting in silence at the table but suddenly erupted to say, apropos of nothing that anyone else had said: “Nobody hates me except Garfield McClure.” He repeated it loudly several times in a pressured way, and seemed to be talking only to himself. Garfield was Luella’s uncle, so she was particularly surprised and discomfited. She also observed, however, that Ewan was correct in his assessment, and that her Uncle Garfield was a controlling and egotistical person who stirred up trouble, and he did undermine Ewan.

Despite Maud’s misery over Chester’s marriage, she held her head high, and continued with her public engagements in the community and in Toronto. On January 8, 1934, she was one of several women who spoke on the topic of “Great Books by Canadian Women” at the Canadian Literature Club in Toronto. She had been invited to speak by one of its officials, a gifted young man named Eric Gaskell, who would figure later in her life. She had been asked to speak on Anne of Green Gables. Marshall Saunders spoke on her book Beautiful Joe, and three other women (not the authors) discussed Mazo de la Roche’s The Whiteoaks of Jalna, E. Barrington’s The Divine Lady, and the works of Susanna Moodie. Unlike Ewan, who lost himself in negative brooding, Maud could use language to help manage her frustrations. One poem that expressed her feelings was written in January 1934, after Chester’s revelations, and is entitled “Night.” The last stanza reads:

The world of day, its bitterness and cark

No longer have the power to make me weep,

I welcome this communion of the dark

As toilers welcome sleep.

Maud would not begin Mistress Pat, the sequel to Pat of Silver Bush, until January 15, 1934, some six weeks after the bombshell of Chester’s marriage. It, too, would embody her explosive personal emotions.

The end of the Macdonalds’ happiness in Norval may have started with the great mill fire that destroyed the village’s character and way of life, but it was sealed by Chester’s marriage. The baby, also named Luella, was born on May 17, 1934.

By June 9, Luella had left Chester and returned home to her father. She told Maud that the apartment she and Chester lived in on Shaw Street in Toronto was “too hot” for the baby. Eyebrows were raised and members of the community exchanged knowing looks. No one had expected Chester to be a good husband.

A substantial number of the parishioners in Ewan’s church were related in one way or another to Luella’s parents. Luella was one of their own, even if she had done the unacceptable and become pregnant before marriage. In their eyes, Chester was a “bad egg”: he had seduced the naïve and lonely Luella after the death of her mother, when she was left to cope with her short-fused, grief-stricken father. If she’d returned to her father—who was in everyone’s view a decent but terribly difficult man—then life with Chester must have been unbearable. People knew that Chester had been thrown out of Engineering, and they wondered how he would fare in his law studies. So did Maud and Ewan, and they were in the uncomfortable position of knowing that everyone else in the community was also watching Chester. Ewan began to feel a chill from his Norval parishioners.

When Luella returned home, she said she was frank with her father about Chester’s behaviour towards her. Chester was always explosive. He left her alone, giving no explanations about where he was. She would later say that whatever faults her father had, she would be forever grateful to him for allowing her to return home, and supporting her after she had brought disgrace on her family. (The attitude that equated premarital pregnancy with shame and disgrace continued through much of the twentieth century, only loosening after contraception was developed and the feminist movement began changing views towards sexuality and marriage.)

The week after the baby’s birth, in May 1934, Ewan had a nightmare about suicide. This terrified Maud: only a few years earlier, in Butte, Montana, Ewan’s brother Alec had gone melancholy, threatened to kill himself, then disappeared. (He was never found.) Ewan was in worse mental health than he had ever been before. He was taking sedatives prescribed by his doctor, and possibly self-medicating with some that were not. He was probably also taking alcoholic spirits for his “constitution,” as well. His nighttime sleep was often disturbed, and he sometimes refused to get up during the day. Maud normally wrote in their bedroom, her screen giving her some privacy, but now Ewan lay on their bed groaning with headaches for much of the day.

By now, Maud had a serious cash-flow problem, because of the continuing financial depression and the loss of her investment money. In 1933, her book income was only $1,641, the lowest it had ever been (except for the unusual year 1919, when she got no income from Page, only the settlement). Even in 1908, when Anne of Green Gables was first published, she had received $1,732 in book royalties. The drop in 1933 was truly alarming. She attributed it to general poverty arising from the Depression and little disposable income for books, but there always remained that terrible possibility that her books had seen their day.

To add to this, Maud now suffered a professional insult. On May 11, 1934, William Arthur Deacon once again implied that her novels were poor and unsophisticated in The Mail and Empire, and compared her unfavourably with Mazo de la Roche:

Whatever advance, in art or in substance, lies between L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables at the beginning of the period and Morley Callaghan’s Such is My Beloved, or Alexander Knox’s Bride of Quietness at the close of it, all that is notable in the Canadian novels falls within this quarter-century. No earlier popular novelist had anything like the skill of Mazo de la Roche.

Maud had long thought that Mazo de la Roche’s novels showed little resemblance to any Canadian society she knew. Years ago, she had sent G. B. MacMillan a copy of the first Jalna novel, along with the comment that it was “clever” and “modern” (December 2, 1927) but that it didn’t reflect life on an ordinary Canadian farm. In a letter to a fan named Jack Lewis she wrote that her own books were true representations of the type of life still lived on the Island. She stated that although her characters were imaginary, they always seemed real when she was writing about them. To her, being judged inferior to Mazo de la Roche was a significant insult.

For his part, Ewan was finding it increasingly difficult to stand in the pulpit and pretend that he was God’s chosen representative. He felt himself a fraud. His preaching began to falter. Composing sermons became increasingly difficult, and delivering them even more so. He started reading them instead of delivering them extemporaneously. Then he started having difficulty even reading his own sermons, stumbling over words like a poorly prepared schoolboy. Next he began to balk when it was time to go to church to preach. Maud plied him with drinks of her homemade wine to fortify him enough to get him over to the church. (She, like her grandmother before her, made wine to “help the digestion.” It was not served at the table, and she kept it in the cellar, so much out of sight that the Norval maids did not know about it, and declared in interviews with me that there was never any alcohol in the Macdonalds’ house. However, there are numerous references to this homemade wine in the journals.)61

When Ewan began talking of suicide in May 1934, Maud was already feeling weak with worry. She had presented his ill health everywhere as physical ailments like headaches, dizziness, and vague internal problems. What if people found out that his problems were mental, branding her family with the stigma of mental illness? That would completely destroy her boys’ future careers, particularly Stuart’s. Nobody wanted a doctor with mental instability in his heritage.

Nora continued to bring consolation and good spirits to the disturbed manse. She had been coming out to visit Maud periodically ever since the Campbell family had come to Toronto in 1928. Like Frede, Nora was Maud’s only safe confidante and “kindred spirit.” Maud trusted her enough that she could tell Nora about Ewan’s mental instability, something she had not even told her relatives in Prince Edward Island.

Nora had been coming out to Norval from time to time, bringing her young son Ebbie, then about ten, with her. Many years later, Ebbie (who became a mining executive, like his father) told a story that is not found in Maud’s journals. He said that as a child he had instinctively felt some fear of Mr. Macdonald because of what he considered a “crazy look” in his eyes. His instincts were confirmed one time when they were visiting in Norval. His mother and Maud were laughing and joking at the dinner table, telling “in” jokes. Perhaps something in Ewan snapped, or perhaps he thought that he was joining in the fun with a practical joke. He rose from the table where his wife and Nora were talking, stepped out of the room, and returned with a gun. All laughter stopped. He pointed it directly at Nora’s head, and acted as if he were going to pull the trigger. Maud was too shocked to move or speak. Ebbie thought his mother was going to be killed by a madman. Then, Ewan lowered the gun and declared it had been a joke.

A few miles west of Norval, in Guelph, Ontario, there was a well-known treatment centre for mental illness and other disorders called the Homewood Sanitarium. Dating from the nineteenth century, this beautifully landscaped private facility treated wealthy and famous patients from all over North America. The grounds were stunning, the buildings baronial, and the doctors as good as could be found when there was no effective treatment for nervous disorders, alcoholism, substance abuse, or mental illness. Homewood was very expensive, and money tight in the 1930s. However, by the middle of June 1934 (after the incident with the gun), Maud decided that she would send Ewan there, telling the parishioners that he needed a full assessment and a rest. If Homewood didn’t help Ewan, she knew that it would at least help her to have him out of the house for a short period.

Ewan and Maud had both been taking medicines prescribed by various general practitioners: Dr. J. J. Paul of Georgetown, Dr. William Brydon of Brampton, and various other doctors that Ewan had sought out in Toronto. Ewan was making the rounds of doctors, peddling his physical symptoms and collecting medications. But he did not tell the doctors about his underlying depression, or “weakness,” as he called it. He was convinced that his heart was weak and he imagined problems with other organs. He was greatly troubled with constipation and he had much difficulty sleeping, as depressed people often do. And he now had periods of losing touch with reality.

Maud administered the various medicines doctors had given him for sleeping: bromides, Veronal, Chloral, Seconal, Medinal, Luminal, Nembutal, tonics with strychnine, and arsenic pills, plus medicines with names such as “Chinese pills,” “liver pills,” and strong cough remedies, which were all made up in local doctors’ offices. Ewan carried one of these cough syrups, which had a strong alcohol base, in his pocket, and took drinks from it all day long to subdue his cough.

Chester and Maud drove Ewan to Guelph, and he was admitted on June 24, 1934. He stayed there until August 17. Maud provided the history of his case.62 By her account, his melancholic attacks had begun in his early teens, and had existed in mild form throughout his university years. He had suffered a severe attack lasting three months when studying theology in Glasgow. In 1910 he had experienced another one lasting about two months, brought about by worry. After the worry was removed, he’d been perfectly well until 1919, when he’d had a very severe attack at age forty-eight, leaving him unable to work. During the next six years he’d had attacks on and off, lasting anywhere from a few days to a few months. From 1926 until the beginning of May 1934, he had been completely free of attacks, Maud said. Then, he had became worried over his heart and blood pressure, despite being told they were not serious problems. The spells usually started with a nightmare or something distressing, and were followed by “headaches,” complaints of “weakness,” and fears and phobias that took over his mind. Maud described the fears as ones of “his future destiny.” He then obsessed about his physical maladies. He would slump, saying he was unable to preach, and his memory seemed impaired.

It is worth noting that Maud did not tell the Homewood doctor any of their recent family problems, including Chester’s forced marriage, the baby’s birth, Luella’s return to her father, and their public humiliation. She gave Ewan’s family history, saying his parents were both of “even temperament,” but she did not mention his brother Alec’s depression and probable suicide. Maud described Ewan in this record as easygoing and the “jolliest man alive” when completely well. She alluded to unspecified fears and phobias that he would not admit to anyone (which perhaps cover all of the personal matters and events she did not want to mention). She did not raise the subject of the medications he had been given, or taken. The admitting physician, Dr. Alex L. Mackinnon, noted that Ewan’s wife was an “authoress from PEI who goes by the pen name of L. M. Montgomery.” The charge for residence in Homewood was then seven dollars per day. His stay until mid-August would cost Maud more than a year’s residence in Knox College for Stuart, at six dollars per week for a minister’s son. In 1934, her income from book royalties had risen to $4,403, but she had many expenses ahead, and these included two sons to educate as her husband was nearing the end of his working life.

Maud returned to writing Mistress Pat while Ewan was in Homewood, and she made good progress, despite suffering bouts of asthma which sometimes became so severe that she had to call Dr. Paul from the next town to give her a “hypodermic.” To other medications she added her homemade wine to help her sleep, and she complained of “a nasty tight feeling” in her head.

Another crisis arose at home. In mid-July, Maud’s maid, Mrs. Faye Thompson, suddenly gave notice that she was going to leave. Mrs. Thompson had been a very good maid and this was unexpected. The timing was bad, too, for it occurred right after Luella had left Chester and returned home to her father, and when Chester himself would be spending more of the summer vacation at home, making more work. Mrs. Thompson’s departure seemed strange when she did not have another job to go to. She said she expected to get a secretarial job, but this did not make sense, given the lack of employment during the Depression. As well, she had no way of affording childcare. Her daughter June was now a very sweet and pretty little girl, and she could not be left alone. Maud was fond of June, and she was very confused and upset over Mrs. Thompson’s curiously inexplicable and sudden departure.

Although Maud hated to lose Mrs. Thompson, she was able to replace her with Ethel Dennis, in August 1934. Ethel was young and naïve, but a respectable, placid young local woman. Ethel was not interested in the hidden inner lives of the Macdonalds, nor intensely watchful of the growing tensions in the family, which was a relief to Maud. Ethel was inexperienced and she require much training, but she was dedicated and loyal.

Ewan was discharged from Homewood on August 17. Maud could not afford to keep him there indefinitely, and she could not see that they were doing anything for him—except teaching him to play Solitaire. He would spend hours and hours on this game for the rest of his life—a big improvement, as far as Maud was concerned, over lying and moaning on the bed next to where she wrote.

Homewood doctors also told him to change his diet: to eat more vegetables, especially salads, to alleviate his ongoing problem with constipation, instead of dosing himself with laxatives. Ewan did not like vegetables or salads, and he did not follow this advice, and the Macdonalds’ normal diet at home did not change. It remained heavy in meats, potatoes and gravies, and desserts—a diet designed for active farm people, not sedentary ministers.

On the way home from Guelph and Homewood on the day Ewan was discharged, the Macdonalds stopped to get a prescription for “blue pills” filled in Acton. Pharmacists often made up their own medications at that time. By mistake, the careless young pharmacist filled the pills with bug poison. Maud gave Ewan one of these poisonous pills the next morning, right after a dose of mineral oil for his constipation. He complained of a burning sensation and soon vomited. The doctor was summoned immediately; miraculously, Ewan suffered no permanent effects from the deadly poison, largely thanks to the oil. But to Maud’s surprise, even though everyone knew he was now home from Homewood, no Norval parishioners came to welcome Ewan back and wish him well. That tipped the Macdonalds off to the fact that something was quite wrong.

In the next few months, Ewan’s mental state worsened. He cycled rapidly between normality and weepy, “sinking,” or aggressive spells in which he declared God hated him and he could never preach again. Maud wrote in her journals that he had never been abusive or violent in this way before, and this frightened her (October 10, 1934). It is possible that Maud’s reference to Ewan’s erratic and threatening behaviour was her way of acknowledging the earlier gun incident without giving the shocking and embarrassing details.

As Ewan’s situation deteriorated, she came to rely a great deal on Stuart emotionally. The always upbeat Stuart had become a force of normalcy in her overwrought life. But he would be returning to university in the third week of September 1934. “Can I continue to endure this hideous life without him?” she asked her journal. Yet, she was glad for him to leave Norval for another reason: his ongoing relationship with Joy Laird.

But, of course, Maud’s greater worry was Chester. He had taken smaller lodgings in Toronto after Luella moved out. Maud did not like him living alone, so she urged him to go back to Knox College in the fall when he started to article in law. But even if Chester had been willing, Knox College would not have allowed him back, given his reputation for stealing. He refused to return to dormitory living, and Luella stayed with her father in the fall, even after the weather cooled down. This confirmed to the community that something was seriously wrong with the marriage.

In early October 1934 there was one happy break for Maud. Murray Laird proposed to Marion Webb, and they were married. The wedding was very quiet, given that Murray’s father had recently died. The only witnesses were Mrs. Alfred Laird, mother of the groom, and Maud herself. Marion, unattended, wore a gown of blue silk, with a velvet hat, and she carried a bouquet of yellow roses and ferns. But even with this small group, Maud could hardly persuade Ewan to perform the ceremony. His on and off phobias were on again on the day of the wedding. Normally, Ewan was very fond of Marion: he loved to tease her because she blushed so easily. But even so, moments before the ceremony was to start, he declared that he was “under a doom.” Luckily he managed to get through the day, and nobody except Maud knew his state of mind.

Ewan was unable to preach in September and October, so Maud arranged for other preachers to come deliver Sunday sermons. Then, on October 12, 1934, Mr. Barraclough told Ewan that the church managers had met and decided to give him sick leave only until the end of December. That meant that he must resign at the end of the year if he was not well enough to resume preaching. With this added pressure, Ewan decided in November to visit his sisters on the Island. Maud was so exhausted by his ups and downs that she willingly acceded. With the disruption, she had been unable to finish Mistress Pat. Ewan rarely slept well, and each day he had new symptoms of imagined diseases, took spells of moaning or raving, or sat around in a dull and moody state. She was herself near the breaking point from the strain.

As soon as Ewan left, Maud could write again, putting all of her own emotions into the imaginary framework of a novel. It was completed at the end of 1934.

Mistress Pat continues the tale of Pat Gardiner and her love for her home, “Silver Bush,” which has been home to the Gardiners for generations. Maud details the rituals of daily life in the joyous family of Gardiners. Like Maud, Pat believes that when people laugh together, they become friends for life. But Pat’s home is under threat—the family is growing up, and the “change” that Pat so dreads threatens from several angles.

The home is given warmth and charm by the presence of rival storytellers: the Gardiners’ Irish maid, Judy Plum, and their hired hand, Tillytuck. The hostile elements in the community are embodied in the ever-present Binnie family, who wield considerable power through gossip. “What will the Binnies say?” is a refrain that always hovers in the Gardiners’ consciousness (as it had in Maud’s), and they must keep assuring themselves they don’t care.

Then, the unimaginable happens. Pat’s brother, Sid, who will inherit the farm, makes a foolish and precipitous marriage to May Binnie. Silver Bush is invaded by an alien presence, in the form of aggressive, coarse, and gossipy May, who has managed somehow to snag Pat’s brother. The Gardiners have always been drawn together by their shared experiences and stories, but May has no appreciation of such ties and sentiment. Silver Bush is just a house to her, and her proprietary presence spoils everyone’s happiness.

Mistress Pat is full of Maud’s literary mannerisms, and the book dwells, to the point of tedium, on the theme of hating change. But it is still a powerful book, perhaps because of Maud’s ability to embody the wrenching change undergone by the western world in the terrible alterations in the Gardiners’ private world. The most powerful symbol in the book is that of the Gardiner home catching fire—significantly, this happens while the family is at church. There is nothing they can do but to watch their home burn down. It ignites because May carelessly left a stove burning when they went to church. May, of course, feels no loss whatsoever now that she has destroyed Silver Bush, and she crassly looks forward to getting a new house in its place.

At the conclusion, Pat’s old friend, Hilary (“Jingle”) Gordon, now an accomplished architect, returns and proposes to Pat. Now that Pat’s beloved Silver Bush no longer exists, she is willing to marry and go away to a new home, one he has designed for her—and the book has the trademark happy ending.

—

This novel was finished in January 1935, about a year after Maud had begun it. It was dedicated to “Mr. and Mrs. Webb and their family,” whose own happy home was emptying as their children married and moved away. Maud’s life was under threat from many angles: the novel had been written during one of the most unhappy periods in her life. Some readers have found the novel unwholesome, complaining that Pat seems more neurotic than normal and sympathetic.

When Maud shipped Mistress Pat off in January 1935 to her American publishers, Stokes, they wrote accepting it within two weeks. But six weeks later, in mid-March, to her dismay, Hodder and Stoughton (her English publishers) refused it. This was a demoralizing and frightening rejection, stirring up the surprise and hurt she had felt when she had been paid a kill-fee for the Marigold stories after being commissioned to write them. Fortunately, by December 1935, she reported that another publisher in Britain, Harraps, had taken Mistress Pat.

The old secure world was gone, like Pat’s home and Norval’s mill. People were now watching with horror as Adolf Hitler became Führer in Germany, and the German Jews were stripped of their rights by the Nuremberg Race Laws. The infamous “Kristallnacht” was still three years away, but the wider world was ready to burn, and Maud’s readers quite understood Pat’s grief in watching helplessly while her beloved home—the symbol of peace, happiness, and security, burned to the ground.

This would be Maud’s last book written in Norval. The burning of Pat’s house was also an appropriate symbol for the end of her personal life in this idyllic village, which had initially promised so much joy.

Problems with Chester continued. In January, the Macdonalds learned that Mr. Bogart was fed up with Chester’s erratic performance. Chester was good at law when he put his mind to it, but all too often he simply did not show up for work, just as he had not shown up for classes. Ewan and Maud made a quick trip to Toronto to try to salvage the situation, and they managed to persuade Bogart to give Chester another try. Chester pleaded that headaches had kept him from going to work. This was a bad sign to Maud.

Something strange was going on, too, in the Old Tymers’ Association. This had always been completely Maud’s own production: she called the meetings; she selected and directed the one-act play, which made up half the program; and she guided other people in developing songs, recitations, and skits for the rest. But for some reason, the executive held a secret meeting, one to which Maud was not invited. One of the parishioners—Garfield McClure (now aged fifty)—orchestrated this.

Garfield McClure had always been a problem. Everyone would have conceded that he was an able man, but also an arrogant show-off who always sought the limelight. (This love of show would follow him to the grave: his elaborate tombstone in the Norval cemetery dwarfs all others.) At that time, he was chairman of the board of the church management, and Ewan had included Garfield in his private assessments of parishioners:

Garfield McClure: A conceited clown who would enter into the presence of royalty unabashed and think himself on the same level socially—one who never considers beforehand what his words may produce. One who expects everyone to toady to him—one who has wild ideas and expects everyone to fall in line with them. One who is not above uttering exaggerated flatteries and doing underhanded work. One who could do some good if he had less conceit and more common sense. One who spoils the little good he does by his silly conduct.

Since Garfield was Luella’s uncle (and was very fond of her), he was furious at Chester’s treatment of her. According to Luella, her Uncle Garfield thought Ewan and Maud should have made Chester treat his wife and child better. Garfield was ready to make trouble for the Macdonalds.

In the Old Tyme Concert, Garfield had always been one of the performing stars (despite a tendency to clown his parts, which irritated many, particularly Maud). He apparently wanted to assume complete control of the organization, taking credit for its success. He called an organizational meeting, telling others he had called it without informing Maud “as a favour to her” because she was so busy with her sick husband. Of course, Maud found out about the secret meeting and learned that she had been deliberately excluded. She was enraged. To her delight, Garfield could not find a suitable play. She graciously provided one. Most of the members saw that he had orchestrated an insult to Maud. The event left a bad taste all around.

But there was far greater trouble brewing. Ewan’s salary in Norval had been in arrears throughout 1934. Then suddenly he was paid. The Macdonalds thought that a nice gesture, particularly given that Ewan had been too “sick” to perform his preaching duties. But Maud felt a continuing chill from the Norval parishioners—quite unlike the Union Church people, who were warm and demonstrative and always solicitous about his health. The Macdonalds were even more surprised when no one from Norval said they were happy to have Ewan back when he returned to the pulpit at Christmas. They would learn the reason eventually, but only when it was too late.

On February 14, Ewan went to a Session meeting and was broadsided by an attack. He was told that people “didn’t want to come to church because of him.” The elders who spoke out—Robert Reid (Luella’s father) was one of them—could offer no proof of this, but all of them, even those that the Macdonalds considered their friends, sat in silent concurrence. Ewan was so wounded by their allegations, true or untrue, that he felt he had to resign.

A day later, he went to Robert Reid’s home and asked directly for an explanation of the ill will shown at the Session meeting. Mr. Reid told him it was the result of “that letter.” Ewan then learned that a letter had been sent out to all parishes from Presbyterian headquarters with directions to keep ministers’ salaries from falling in arrears. As chairman of the board, Garfield McClure had felt chastised by the letter, and was sure that Ewan was the source of this complaint. Garfield had not recognized that the letter was a circular sent to every church, not a missive sent to rap specific knuckles at Norval.

Ewan explained the facts of the case, but he discovered that the truth made no difference to the general feeling of his board of management. Garfield McClure was on a personal vendetta to force Ewan’s resignation, and he had turned many of the Norval congregation against Ewan. He had whispered that Ewan had been too sick to work, but not too sick to complain about not being paid. People could plainly see that Ewan, sick though he might be, did go out in the car from time to time—to Toronto, to Glen Williams (to visits with the Barracloughs), and to chauffeur Maud to various engagements. Many Norval parishioners were already resentful of the Macdonalds’ close friendship with the Barracloughs. Ewan was also criticized for travelling to the Island for a “vacation” when he claimed to be too ill to preach. And since Maud had told everyone that Ewan’s troubles were physical, not mental, and they believed her, there was some justification for grumbling that if he could do so much travelling, then he could also preach.

The Norval people were of a mind that it was time for Ewan to move on and let them get a new pastor who would do his job. And, indeed, it was probably time for him to relocate or retire: church morale was down. Ewan was sixty-five, and he was finding it too stressful to perform as minister—after his humiliation over Chester’s behaviour. Still, the whole affair had been badly handled, and Garfield’s underhanded scheming had intensified the bad feeling.63 Ewan and Maud were profoundly hurt, but they held their heads high. They rightly suspected that Chester’s behaviour had played a big role in the community’s actions against them. Whatever the causes, there was no turning back.

Ironically, Ewan’s indignation at his treatment renewed him, and he started preaching vigorous sermons again. Righteous anger had dispelled his demons far better than Homewood’s expensive treatment. The word quickly went through the community that the elders had been wrong about the letter, and that Ewan had not complained about Norval being behind in payments. This softened people’s attitudes; Garfield and the men responsible for the misunderstanding slunk about attempting to clear themselves of blame. But as Maud noted, with her keen understanding of human nature, the Macdonalds were now resented by certain Norval parishioners precisely because those parishioners now knew they had treated their minister and his wife badly. Resignation was the only possible course of action.

Maud had always hoped that when the time came for Ewan to resign, in the normal course of events, they would buy a tract of land down by the Credit River and build their retirement home in Norval. She did not like living in cities, and she loved the beauty of Norval. She had liked almost all of the parishioners in both parishes before the blow-up. But now the insults she and Ewan had endured from some of them “stained backward” through her association with everyone. They must pack up and leave as quickly as possible.

Toronto would be their destination. Maud loved to visit relatives in Prince Edward Island, but it was never a consideration for retirement. Toronto was where her sons were studying and would start their professions. Maud had many literary friends in Toronto, as well as Nora. She hoped that in Ewan’s retirement—when she would be free of church work herself—she could employ her formidable organizational and speaking skills for the benefit of Canadian writers and Canadian literature. Now, with her boys nearly grown, she could concentrate fully on her own writing, and her own career in the literary world of Toronto. She began looking forward to the future.

William Arthur Deacon, now the influential Literary Editor of The Mail and Empire, had not changed his attitude towards her books. But she had received an important honour that spring—the invitation to become a member of the Literary and Artistic Institute of France, extremely rare for a foreigner.

The Macdonalds had to find somewhere to live in Toronto, quickly. Maud’s investments were still in bad shape, and she did not have enough ready cash to buy a home. She calculated that she could afford fifty dollars a month to rent a home, but the homes she saw at that price were very far below her standard. She hated all the parts of Toronto where the houses were “cheek by jowl” with each other, without space and trees. Then, good fortune intervened. She contacted an innovative realtor named A. E. LePage.

Albert Edward LePage had come into the fledgling real estate industry in 1913. He was a gifted and energetic salesman who catered to the rapidly expanding professional and business classes as Toronto spilled into the suburbs. He was instrumental in establishing the Toronto Real Estate Board and instituting a code of ethics. He was the first Toronto agent to professionalize the business of selling personal homes, devising ingenious ways that people who could not afford to buy a house outright could buy with a mortgage. Maud had found a saviour. Best of all, he was also from Prince Edward Island. Maud felt especial trust in him that was not misplaced.64

As it happened, a famous developer and architectural firm was just opening up an area on Toronto’s outermost western fringes called “Swansea.” On Riverside Drive, the road that Maud and Ewan took to Toronto, she had admired a new development of homes. She fell in love with the property at 210A Riverside Drive (now 210 Riverside Drive). It was listed at $14,000, far more than she could pay all at once.

LePage showed her how she could purchase it with a down payment of a few thousand dollars and a mortgage. She could pay the mortgage off later when some of her stocks rose or when her insurance policies paid dividends. As the agent for that house, LePage negotiated a reduced price of $12,500, and Maud bought the house of her dreams. Her neighbours would all be successful businessmen, entrepreneurs, and professionals. LePage himself lived down the street at 202 Riverside Drive. She could take the streetcar on nearby Bloor Street West and ride downtown on her own. With these negotiations in place, Maud wrote that she “felt like a new creature.” “Hope and encouragement flooded warmly over my bleak heart. Everything seemed changed.… I felt for the first time in a long while that it might be possible to go on with life graciously after all” (March 8, 1935).

The Toronto papers—no doubt contacted by LePage, who saw a good advertising opportunity—carried a picture of the home that Maud had bought, with a description of it.

Mrs. L. M. Montgomery, authoress of “Anne of Green Gables” and several other notable books, has just purchased 210A Riverside Drive, an attractive centre hall, old English type of home, designed by Home Smith & Co’s architectural department. It is located on a beautifully wooded ravine lot, 52 × 130 feet, overlooking the Humber River and contains seven large rooms and three bathrooms and a two-car heated garage. The sale was negotiated by A. E. LePage, realtor, who was born on Prince Edward Island where most of Mrs. Montgomery’s scenes in her books are laid. Morris Small was the builder of the house. It is understood that Mrs. Montgomery, who in private life is the wife of Rev. E. Macdonald, has just completed another book which will be out next fall and that a number of producers are negotiating with her for the screening of her stories.

Wrapping up their last six weeks in Norval was less painful for Maud now, with the prospect of a beautiful new home of her own. Luella and her baby would stay on with her father, and Chester and Stuart would live at home again. For all her frustration with Chester, Maud missed him a great deal.

Still, leaving Norval brought sadness. The Macdonalds hated to move away from the Barracloughs, who had been such good friends. Maud really liked many people in Ewan’s parishes and resented that everything had been spoiled by a few. More than anything, Maud loved the beautiful and quaint little village on the banks of the Credit River, where she could call her cats and then hear haunting echoes.

There were rounds of farewells in all the different organizations, with speeches and gifts. All brought mixed feelings. Maud, who had been feeling exhausted by her endless obligations, suddenly experienced paroxysms of sorrow whenever she thought this would be the last time she worked with a particular group. When Ewan, who was still fuelled by the injustice he had felt, did so well in his final sermons that Maud felt sad that this was the last time he would be in his own pulpit. If she looked out her windows, she was overcome with “soul-sickness” and would break down in tears. She experienced attacks of claustrophobia, feeling in one moment as if she had to escape the house and the walls around her, but in another afraid of the future outside. Her nights were flooded with bad dreams and then wakefulness. She was engulfed by temporary but terrifying waves of despair, which made her feel “hungry for death.” She went to Dr. Paul for a tonic. “He does not however sell peace of mind or relief from a sore heart in bottles,” she quipped (April 4, 1935).

When moving day came—April 25, 1935—Maud got up early to take her last leave of the views she loved: “my beautiful river—silver calm with trees reflected in its sunrise water. Little mists were curling along it in the distance.” It was “a lovely warm day,” and she fought back tears as the rooms were emptied. The vans left for Toronto around 2:00 p.m. She went from room to room in a final check, saying farewell to each. “I have never felt such anguish on leaving any place, not even the old Cavendish home” (retrospective entry, dated April 24, 1935).

As Ewan took their Willys-Knight car out of the garage and they drove away, she puzzled over his absence of sentiment, remarking he “has absolutely no ‘feeling’ for places, no matter how long he has lived in them. I would not be like this for the world. I ‘love’ to love places. But at that moment I envied him his incapacity for loving any place” (April 24, 1935).

Maud had become deeply attached to every place they had lived, putting down “deep roots.” But she had been a transient sojourner in all her homes. Now she was going to a home of her own. No one could cast her out. She prayed that it would be a permanent and happy home. It would be her last “new beginning.” She would call the house “Journey’s End.”

Maud and her Norval Drama Group, around 1927.

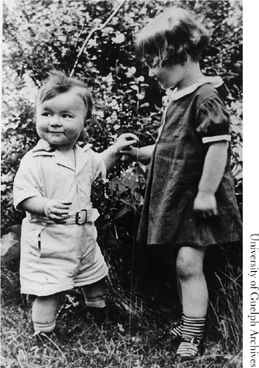

Luella Reid Macdonald and children,

Cameron and Luella (and right).

Maud in the 1930s.

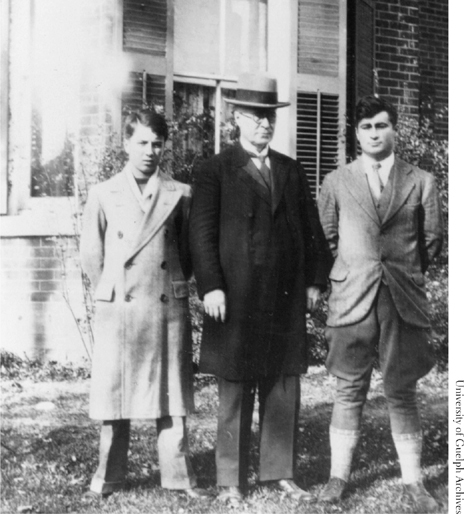

Stuart, Ewan, and Chester Macdonald, circa 1930.

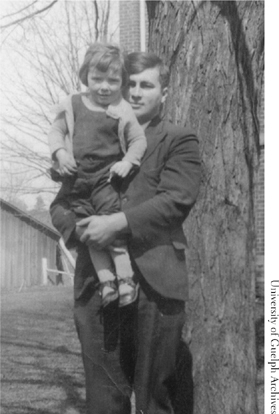

Chester holding June Thompson in Norval.

Chester Macdonald in kilt.

Maud in cloche hat, probably in the early 1930s.

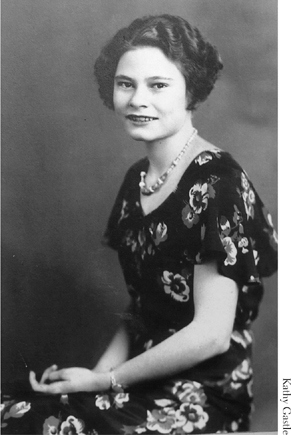

Joy Laird around age 16.

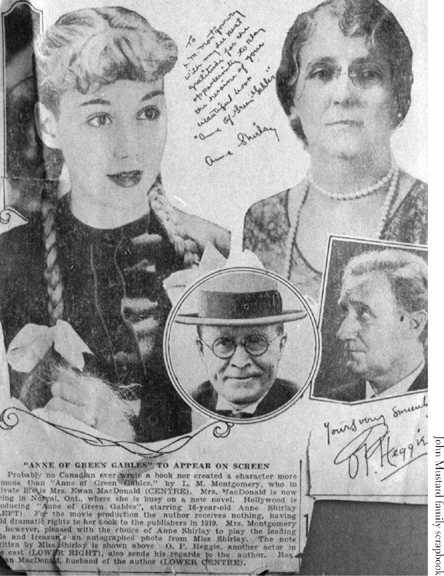

Scrapbook picture of “Anne Shirley,” Maud, Ewan, and O. P. Heggie (“Matthew”).