Maud wanted to be buried in Prince Edward Island, the isle of her birth, in the Cavendish cemetery where all her kinsmen lay. Her husband and two sons made the thousand-mile train ride with her remains. They crossed the windy Northumberland Strait by ferry, travelled to Hunter River by local train, and were driven the last twelve miles by car.

The burial was in Cavendish on April 29, 1942, in the “cemetery on the hill,” next to the schoolyard where she had played, and near her mother’s and maternal grandparents’ graves. In one direction lay the “Green Gables” house and “The Haunted Wood.” In the other direction, towards the sea, lay sand dunes and lingering patches of white ice floating on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The “reluctant Canadian spring” had not yet come to the Island, and some drifts were still unmelted. Normally, cold winds blew off the sea, but on the day of Maud’s funeral a warm, soft wind blew over the land towards the ice. In that gentle breeze, a few songbirds sang, according to accounts at the time.

The little white wooden church was filled to capacity, and many mourners had to stand outside. They had come from all over the Island. The officiating minister was the Reverend John Stirling, who some thirty-one years earlier had married Maud Montgomery and Ewan Macdonald. Recalling the funeral years later, his daughter observed that in 1942 he was close to death himself, facing the most difficult funeral sermon of his life. He fought to control his own emotions as he spoke. His sermon was followed by the comforts of the Twenty-Third Psalm, a prayer by the Reverend J. B. Skinner of Winsloe, and a scripture reading by the Reverend G. W. Tilley, pastor of the Cavendish church.

The official account of this funeral in the Presbyterian Record does not record a somewhat unseemly disturbance in the church also recalled by his daughter. Ewan Macdonald kept looking around in confusion and crying out, “Who is dead? Who is dead?” Each time he was told by his sons who it was, he would ask cheerfully, “Who is she? Too bad! Too bad!” Then the “Who is dead?” questioning would begin again.

Ewan’s disruptions, which his sons tried desperately to silence, added to John Stirling’s distress and, for those who heard them, to the pathos of the service. The church was filled with those who either had known Maud or who felt enormous pride in her achievements. The mourners were stifling the sounds of grief they felt for one of their own, one who had gone away and had now come home in death to the land that had produced her talent. Even people who had never met her basked in the glory she had brought the Island. Those who had read her books instinctively loved anyone who could have written them; they did not have to have known her personally.

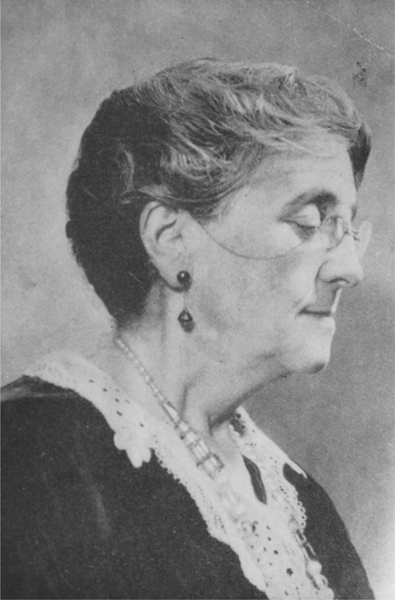

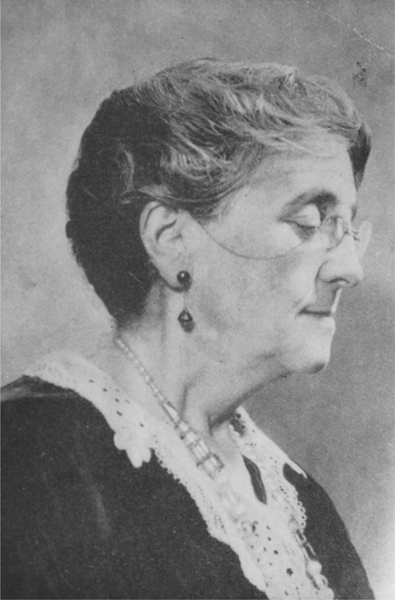

There were whispers asking how she had died: it was an open casket, and, wasted to nothing, she did not resemble the woman they had known. She looked “horrible,” some whispered, lacking fitting words. Appropriately, the minister’s final benediction looked to the future, when visitors would come to visit her grave and “feel their pulses quicken at the thought of their proximity to the dust of one who painted life so joyously, so full of hope, and of sweetness and light.”1

Adjacent to the schoolyard where Maud played as a child, this Cavendish graveyard was a scene of beauty and tranquillity, with rolling hills surrounding it and the distant sound of the pounding surf. Maud had asked in her journals that her tombstone be inscribed with a line she had adapted from Shakespeare: “After life’s fitful fever, she sleeps well.” No one had read this request in her journals, and so she sleeps peacefully among her own folk without it, her grave visited regularly by fans from all over the world.

Ewan gave much wrong information on Maud’s death certificate. He said her father’s first name was “Ewan” and then he changed that to “Hugh John.” He listed Hugh John Montgomery’s place of birth as England instead of Prince Edward Island, and her mother’s place of birth as Ontario, instead of the Island.

But Ewan was confused only part of the time. He could also be quite lucid. After Maud died, he made a call to Luella, expressing concern for her welfare and distress because Maud’s will was being ignored. Luella knew nothing about the will, and the phone connection was poor. She did not know what he was talking about when he said several times, “This isn’t what Mother intended, this isn’t what Mother intended.” The call was cut short by the sound of the phone being slammed down. Luella never heard from Ewan again.

The trust company wound up Maud’s affairs and put the house and many of its contents up for sale. Ewan could not live alone, so Stuart arranged for him to go into a private-care nursing facility in Toronto. He was showered with attention there by nurses who loved this gentle, dimpled, smiling old man, and made his final year happy. He died at St. Michael’s Hospital on December 18, 1943, at age seventy-two, his cause of death listed as “Arterio-sclerosis Heart Disease and Emphysema.” Stuart was in the Canadian Navy by the time his father died, and Chester gave the information on the death certificate, spelling of father’s name as the original “Ewen,” rather than the “Ewan” that Maud had used.

Ewan’s story, as written by his wife in her journals, is that of a man who was a lifelong worry to his family because of his “malady,” as Maud termed it. Stuart Macdonald believed that his father suffered from bouts of depression, but he never, ever regarded him as mentally unsound. Stuart retained enormous affection for his father’s memory, but said that his father became a terrible hypochondriac towards the end of his life, and that the RCMP contacted him about his father’s attempts to get drugs like codeine from different doctors as he continued his ongoing search for an elixir to make himself feel better.

In the 1980s, the very bright and observant Luella was adamant, after reading Maud’s first nine handwritten journals, that no one would have thought Ewan as psychologically impaired as he seems there. Nora Lane, the daughter of Ewan’s doctor, insisted that her family always thought him a sweet, lovable, but lonely old man, with nothing abnormal about him. Marion Webb Laird lived with Maud and Ewan in Norval for an extended period and said that although they were definitely a “strange couple,” they were each clearly very fond of each other. We will never know the extent to which drugs, prescribed by a medical profession that did not yet know their full effects, and continued by Ewan without adequate monitoring, were what damaged this benevolent and unfortunate man’s mental and physical health. His side of his story will never be told.

After his mother’s death, the bank executors changed the locks on the doors so they could take an inventory of the contents of the house in order to settle the estate, Chester no longer had access to the house. His next recorded address, in December 1943, was 142 Douglas Drive in Toronto. He moved about in Ontario after that, making several attempts to set up a new law practice, always trading on his mother’s name. In 1945, his address was Tillsonburg, Ontario. In 1946, it was Fort William, Ontario. An article in the Fort William Daily Times-Journal on July 23, 1946, stated that Chester had come to establish a law practice there, and that he was a son of L. M. Montgomery, and he reminisced in the local newspaper about his mother. Next, he turned up in what is now Thunder Bay, where he made another attempt to establish a law practice. Apparently on an impulse, according to someone who lived there then, he “borrowed” a light airplane and flew it successfully, but damaged it when he brought it down. Again, he left town, suddenly this time. His next address appears to have been 18 Skipton Court, Downsview, Ontario, a street whose name appropriately characterized his sad trajectory.

He married Ida Birrell, some two years after Maud died. Chester’s first son by his second marriage was born on April 18, 1944; his divorce from Luella became final, according to her records, on May 31, 1944; he married Ida on August 31, 1944. The order of those events would have upset his parents had they still been alive, but then Chester had never walked the straight and narrow path.

At one point, Chester and Ida invited Stuart and his wife, Ruth, for a Sunday dinner in Downsview. Ida had gone to much trouble to cook a meal, and they all sat down to enjoy it. Before Chester carved the turkey, he removed his false teeth and set them down beside Ruth, who was sitting adjacent to him. They remained there for the entire meal with the casual explanation that they did not fit well.

Stuart, as a gynaecologist, was in charge of the venereal disease clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital when Chester needed treatment. There were other such clinics in Toronto, but Chester came to Stuart’s clinic and made a point of telling everyone that he was Dr. Stuart Macdonald’s brother—a great embarrassment to Stuart in his own professional territory.

By 1954, Chester had obtained a good position working for the Ontario government, in the Office of the Public Trustee. Office staff there remembered how lawyers in Toronto would telephone Chester when they needed to locate a certain case study, particularly about estate or real estate law, which he knew very well. In pre-computer days, Chester’s extraordinary memory could recall the book and subsection in which relevant case studies were located.

With a steady income, with a devoted wife and two young children from his second marriage, it appeared that Chester was finally settling down to a respectable life, at age forty-two. But he had many sides—from the “elite” aristocrat who would not eat in the kitchen like a peasant to the host who dumped his dirty false teeth beside his dinner guest’s plate.

On September 13, 1954, the Ontario Provincial Police swooped into his office and arrested him. He had put his excellent legal brains to use in the Office of the Public Trustee by devising a scheme of embezzlement. When people died and left an estate, the money was turned over to the Office of the Public Trustee. Chester was in charge of dealing with unclaimed estates. This involved advertising nationally for unknown relatives. If no claimants turned up after a set period of time, the money went into the provincial purse.

Chester almost always managed to turn up relatives in distant places in the very last moment before the waiting period expired. But one day, a bona fide relative turned up at the eleventh hour to claim an estate—and found that it had already been claimed.

Upon investigation, the person who had claimed it did not exist. The trails were easy to follow. In his careless, sloppy way—one that almost invited detection—Chester had left his desk drawers full of incriminating evidence. There were cheque stubs, bank drafts, and copies of letters. Chester had fabricated the identities of the spurious relatives, laying claim himself to the inheritance. He had been squirrelling away money in fictitious accounts, and then emptying these into his own bank account. The embezzling scheme cheated no one but the government, and hurt no one specifically, and it might have gone on until the end of his career but for the fluke of the one man turning up at the last minute, after a ten-year wait, and demanding to know who had claimed his inheritance of $23,045.

When Chester was first arrested, Stuart was called down to the jail by bail officers. Chester assured Stuart that if they could make restitution of the money, the whole thing could be hushed up. In clan tradition, Stuart wanted to avoid the public shame that would be brought on the family name, and put under pressure by the immediacy of the situation, he agreed.

Stuart and Ruth were just negotiating to purchase their first home in an exclusive area of Toronto when Chester was caught. Chester ascertained the amount of Stuart’s accumulated down payment for this house, and then he assured Stuart that this money (variously reported as $8,000, $10,000, and $10,500 in the papers, and remembered as $10,000 by Stuart) would cover it exactly. Chester promised Stuart faithfully that he would repay him. It was a weekend, and the affair was not known yet. Stuart laid down the money.

Chester had embezzled not $10,000, but some $35,600, and Chester’s picture appeared—with him in handcuffs—in the paper anyway. Stuart and Ruth lost their money, which went back into the public purse as part of what Chester owed. They had been saving for that house since their marriage, and now had to start anew. Chester himself had just bought a new ranch-style house in Etobicoke on Burnhamthorpe Road.

Chester’s arrest was big news—it was a major embezzlement scheme, and $35,600 was a lot of money in 1954. The newspapers went after the full story, but, incredibly, they never found out that Chester was L. M. Montgomery’s son. Chester had traded on his mother’s name from the time he began to study law and especially when he tried to establish new practices after her death, but now, for once, he kept quiet about it.

Reporters descended on his faithful wife, Ida, who had been pleased that her husband was doing so well in his job that he had been able to buy them the house. Chester had handled all their finances, and she was shocked, and bewildered by the devastating news. She lamented to reporters that they would probably lose their house now. They did, of course; Chester not only lost his own house, but orchestrated the loss of the house that Stuart was about to purchase, too. Ida, loyal to her husband, told the reporter: “He must have been born under an unlucky star. Nothing has gone completely right with him, although he did his best to help everyone. Time and time again he went out of his way to help friends in trouble and he got kicked in the face for his pains.”2 Chester did in some ways try to help others, and people were genuinely fond of him. His impulses were always generous, even if his means were not always honourable.

Chester was brought to trial a year later, and sentenced on September 28, 1955, to two years less a day in the Guelph Reformatory for embezzling money from the government. The lawyer representing him was Donald F. Downey, his former partner. While Chester served his term Ida and her children stayed with a brother in Guelph to be near him. He was released on November 24, 1956, before his sentence was up, presumably because of good behaviour.

According to Luella, while Chester was incarcerated, he noticed that there was another inmate named “Macdonald” in the Guelph Reformatory. When Chester inquired who he was, he had the extraordinary experience of discovering that this was his own son by his first marriage, Cameron Macdonald, age twenty. They had not met since Chester and Luella had separated, but young Cameron had inherited some of his father’s traits for getting into trouble.

Another person who was shocked by Chester’s arrest was his own secretary, and her perspective offers yet another view of Maud’s complex son. Like many others, she felt he was a good man, a generous man, and a devoted family man. Chester had always been kind to her. She had first met Chester when he was living up north, attempting to start a law practice. Both were in an amateur theatre production—something he still enjoyed. She was a single parent with a small child to support. Chester, being a lawyer, offered to help her get child support payments from her husband. He did all the paperwork, and she started receiving her payments though Chester.

After Chester and Ida moved to Toronto, and he himself found this job in the Office of the Public Trustee, he urged her to move to Toronto. He told her she would have a better chance of finding work in the city. He helped her get a secretarial position in the office, and she became his secretary. Always paternal and helpful, he continued, along with Ida, to be supportive. She said he was quite “the character,” but everyone liked him.

Unfortunately, now that she was in Toronto, her child support payments started faltering. With her secretarial job she was usually able to cover her apartment and food costs. Sometimes, however, she had a shortfall—if she had to purchase clothes for her child, or if she didn’t have quite enough for groceries—and then Chester would always produce a little money (usually five or ten dollars) from his own wallet for her. He always told her she did not need to pay him back, given that he knew how she was struggling to make ends meet. She was very touched by his kind consideration.

When the full investigation of Chester’s affairs was finished, she was astonished to find out that her husband had made all his payments on time, and in full. Chester had taken the money paid in trust for her and kept it for himself, doling out bits when she was herself unable to make ends meet.

After he was caught, Chester promised her that he would return the money to her, and begged her to store his mother’s books and other items for him until he got out of jail. He told her he was afraid they would be taken from Ida and sold to make restitution. She felt pity for him and agreed to do so. He had a forlorn and needy quality that softened people, she said, even when he had hurt them. You could not help liking him, for you always felt he meant well, but was weak.

When Chester got out of jail and came to claim his mother’s books and manuscripts, he told her she was number thirty-six on the list of people he owed restitution. She kept moving down the list, but never quite made it to number one.

People always wondered why Chester was so short of money. Once, he told this secretary it was because Stuart had defrauded him out of his share of their mother’s estate, a bald untruth. In fact, Chester had himself sold his rights to his mother’s published books to her publisher (ostensibly to finance his marriage to Ida.) Jack McClelland became the beneficiary of half of Maud’s Canadian royalties—a boon that helped him continue in his father’s lifelong career of promoting Canadian authors.

Chester’s secretary reminisced about Chester’s complicated and needy character, and his social life. She said that he always “had other women” and she thought this was one of his expenses. He smoked non-stop, and he never had enough money for this habit, either, so he generally “bummed” his cigarettes off others, to the point where people would duck out when they saw him coming. Always rumpled and untidy, he became a joke at work for his eccentricities. He retained an interest in amateur drama and was known as the person to call if an actor suddenly fell ill. Chester could learn any part—small or large—almost instantly, either by reading the playbook or by watching a single rehearsal. But he was absolutely no good as an actor. He could ham up his parts, but emotions never seemed genuine. “It was as if some part of him was missing,” she said, “the part that makes you able to truly empathize with others, and to know how they feel.” This is one of the classic traits of the psychopath.

When his secretary asked him, after his jail term was over, if there was anything he would do over, he answered, “Yes. Not get caught.”

Released from jail, he eventually found a job at the office of Canadian Law Books as an assistant editor. It is unknown if the company was aware of his past when they hired him. He died suddenly, at age fifty-one, on June 14, 1964, at his apartment at 5785 Yonge Street, in Willowdale. His death certificate gives no cause of death. His last date at work had been in February 1964, three or four months earlier. He was cremated. The obituaries mentioned that Stuart Macdonald was his brother, but not that he was the son of L. M. Montgomery, perhaps the most interesting feature in his short and troubled life.

After the funeral of Chester’s wife, Ida, many years later, her sister said sorrowfully to me: “She had a very hard life, filled with many, many disappointments.” Ida had pleasure in her children, though; daughter Cathie lived a quiet life with her mother, and son David went on to a very successful career as a teacher and school administrator.

In March 1943, Stuart Macdonald entered the Canadian Navy, where he became the medical doctor on the Huron, a Canadian destroyer that patrolled the English Channel, departing under the cover of darkness to pick up the wounded. On July 10, 1943, he married Ruth Steele, a petite and beautiful nurse he had been courting since before his mother’s death. Maud never met Ruth.

Stuart returned safely from the war, but he was disturbed by “survivor guilt” and occasional nightmares about his experiences for the rest of his life. He also suffered a very deep, lifelong sense of guilt that he had not been able to prevent his beloved mother’s death—a phenomenon common among those who experience a parent’s suicide. He had an understanding of human nature born of deep reflection over his own family. He told others that “you can’t save people from themselves.” He had been both repelled and fascinated by his brother’s lack of conscience, just as Chester had apparently been mystified by his brother’s ability to attract loyal and devoted friends without effort.

For many years Dr. E. Stuart Macdonald was considered one of the most skilful obstetricians at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, and his obituary in Maclean’s magazine, in October 1982, described him as a much respected doctor. He had seen his last patient in his office minutes before visiting a neurologist about increasingly severe headaches he suffered a fatal brain aneurysm during the actual examination.

As a young man, Stuart had been embarrassed if people found out that his mother was the famous “L. M. Montgomery” and he kept this a secret during his training. Mid-life, as a very busy doctor who was pestered by people interested in his mother, he sometimes revealed resentment of the burdens that being her son had placed on him. To a few, he expressed an annoyance that she had expected such perfection from her children. When pressed to comment on her shortcomings, he named her “pride” and her tendency to worry, but he clearly admired and loved her. There was a profound bond between him and his mother, and he spoke of the deep affection that she engendered in everyone who knew her. Shortly before his death, he reflected that in a long career practising and teaching medicine he had probably saved only five or six babies that no other doctor could have—a small contribution to the overall “sum of human happiness,” he said, compared to his mother’s enormous one through her life and her novels.

Stuart and Ruth achieved what his mother had wanted all her life—a home that was always open to friends and guests and young people (some of whom Stuart had delivered). He and Ruth adopted three children, and they cherished their “chosen children” as much as Matthew and Marilla loved their own little “Anne.”

At his funeral, the large chapel was filled beyond overflowing with medical colleagues, friends, and patients. Everyone remembered Stuart’s storytelling ability and his keen sense of humour, and lamented the passing of a man who, like his mother, was a unique and unforgettable personality.

Luella Macdonald came to the last part of her life—a life filled with unimaginable difficulties and personal tragedy—as a very strong and philosophical woman who had transcended bitterness. She was a woman of much intelligence and intellectual curiosity, and a plucky soul as well. She was well-read and wise, funny and frank. She said what she thought, and she met everything head on. She recovered from two serious strokes in her early retirement years and resumed a full and active life after learning to drive and speak all over again.

Luella had raised her two children by herself, taking a job in an aircraft factory to support them, and her tales of her struggles were heart-rending. At times, she had nobody to watch the children, and no money to hire help. She did her best to “child-proof” the house and left the children locked in it while she worked. Her eyes moistened as she described how the children would cry when she left in the morning. In an era before government social assistance and enforced child support, she said there were many abandoned or widowed women (and fathers who had lost their wives) who had to make choices like hers: leave your children without proper supervision—or go without food.

Luella retained a soft spot in her heart for Chester all her life, despite the way he had treated her. She thought of him as someone to be pitied, and she had come to the opinion that there had been a genetic problem from the beginning. She believed that when he came into life, defeat was already sitting there, just waiting to knock him about. She said there were “signs of compulsive lying from time to time.” She picked up many negative feelings from him about his father, but “never about his mother.” He “had a brilliant mind but somewhere along the line nothing happened to give him any direction for living.… he was a ‘mucker,’ ” she said. When I asked her if the rumours I had heard that Chester had taken his own life were true, she said she didn’t know, and then added, sorrowfully but without bitterness, that it would “have been the honourable thing to do—he brought lots of misery into the world, to lots of people.” Misfortune pursued some of Chester’s first family into the next generation, and Luella’s account of the tragedies (accidental death, alcoholism, mental illness, homicide, and suicide) are too terrible to detail. Luella was proud that her daughter, also named Luella, became a nurse, and she spoke of her daughter and grandchildren with great affection.

According to Mr. Justice Douglas Latimer, the Crown Attorney for Halton County from 1968 until his retirement, Joy Laird became the best legal secretary in the entire area. If she had been able to afford the study of law herself, he said that she would have been an excellent lawyer. He described her as very hard-working, reliable, and smart, with a wonderful memory. In her adult years she had a serious no-nonsense demeanour, but she also enjoyed socializing, and had a quick and ready wit. She had an excellent manner with clients, and she mixed regularly and easily on a social basis with the most influential families in the area. She had excellent taste and brought class and natural dignity to the position she occupied.

Joy began her career with the Dale and Bennett law firm in Georgetown, the oldest in the area, as secretary to Sybil Bennett, a very prominent lawyer (the first female Q.C), and a second cousin of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett. Sybil Bennett thought so highly of Joy—who kept the firm running when the partners were otherwise occupied—that she purchased Joy’s first car for her as a gift. When the Dale and Bennett law firm was put up for sale, Joy Laird, then a senior secretary in the firm, called Douglas Lattimer and urged him to buy it, which he did the year before he was called to the bar in 1972. She all but ran the firm until he graduated and could take over. The firm then became Dale, Bennett, and Latimer.

Justice Latimer said that Joy, twelve years his senior, knew everyone in the entire surrounding community, from the poorest to the wealthiest. Because everyone knew, respected, and trusted her, people brought their business to the firm. When he became Crown Attorney for Halton County and left the law office, Joy followed him, remaining his loyal secretary until her retirement. He could not praise her enough, and joked about how she had told him that if he ever made a mistake, to blame it on “his secretary,” because people would forgive a secretary but not the lawyer himself. Joy, he said, did not make mistakes—she was a perfectionist and a professional in every way.

Joy Laird never married, despite many would-be suitors. She was a very private person, and no one knew that she nursed a memory of her early and only love, Stuart Macdonald. She treasured the scores of letters Stuart had written her over a long period, as well as Stuart’s 1939 medical pin. Because she had been unable to afford further education, she borrowed Stuart’s advanced math and other textbooks from St. Andrew’s, working through them for self-education. She kept every clipping about him or his family, as well as his pictures of him as a gymnast at St. Andrew’s and then at the University of Toronto, performing on the high bars. But the memory of their young romance died out in the community, and she never mentioned it to anyone. Only after knowing her for many years did I begin to piece things together. My most unnerving experience was being taken to her beautifully decorated bedroom to be shown something, and to see, in a prominent place, a near life-size, incredibly realistic doll, fully dressed, looking like a real baby. It was introduced as a doll that had belonged to the Brown children, who had been killed in the radial train accident in Norval.

Joy never knew how strongly Maud had opposed her romance with Stuart. She died in 2003, the year before Volume 5 was published, giving the full story of Maud’s antagonism to Joy’s family.3

In a drive through Norval a few weeks before his sudden death in 1982, Stuart pointed out Joy’s childhood home and volunteered that his mother had been completely wrong about her—that Joy had been a very nice young woman, no matter what her father did. Stuart remarked with considerable irony that his mother should not have held other families to standards that her own family could not meet. He added bitterly that his mother should have invited Joy into their Norval and Toronto homes to see if she would fit in, and this would have enabled their romance to either go ahead or fall apart naturally. He still felt sadness and shame that he had not had the courage to insist that his mother get to know Joy before condemning her. His mother’s health problems, his own busy career, and impending war brought such trauma into their lives that other personal concerns fell aside, and then he met the lovely Ruth, a trained nurse, and married her.

Joy Laird cared for and supported her aging and much-loved mother all her life. She also cared for her father and her feckless, alcoholic brother until their deaths. Mercifully, she never knew that Maud had called her “that bootlegger’s spawn” in her journals (October 23, 1936), but those bitter words were seared painfully in Stuart’s mind. He knew that his mother wanted him to publish her journals eventually, as a record of her life, but those words were responsible for his keeping his mother’s journals under wraps until the end of his life. He felt embarrassment that his mother had said what she did; and he worried that people might believe his mother’s assessment of Joy.

The publication of Maud’s final journal in 2004 brought shock to the community where Joy lived. No one had imagined that “Mrs. Macdonald” had felt as she did about Joy Laird. Norval people who had been Joy’s lifelong friends— Mary Maxwell, the wife of Canon Maxwell of the Anglican church in Norval, and Joan Brown Carter, the postmistress of Norval for many years and an amateur historian—told a very different story about Joy, as did Joan Carter’s youngest daughter, Kathy (who grew up as Joy’s godchild, and thought of her as a second mother).

Kathy Carter Gastle, who was mayor of the town of Halton Hills from 2000 to 2003, remembered the Laird home as a very happy place where people were always welcome. The house was spotless and well-decorated, and Joy’s mother was a kind and cheerful woman, and a splendid cook who liked young people.

Kathy Carter grew up looking through her godmother’s scrapbooks. She heard a great deal about Stuart Macdonald from Joy as a fondly remembered childhood chum. Although Kathy never actually met the fabled Stuart Macdonald, he was a fixture in Joy’s stories of her own childhood. Joy had always loved children, and took her position as godmother to Kathy Carter very seriously, giving her many advantages, such as special trips that she would not otherwise have had as a youngest child in a large family. They were as close as mother and daughter until Joy’s death. At the end of her life, Joy gave Kathy a red silk pouch full of the school crests from Stuart’s letters, which she had carefully clipped off each letter before she destroyed the letter itself.

The community did not look down on the Laird family, and after Maud’s Norval journals were published, people wondered over the malice directed at them. Perhaps when Maud complained about the fact that she couldn’t imagine where Ewan’s salary went, she may have suspected that Ewan—like many other respectable men wanting their “nip”—dropped in to pick up the occasional refill for his cough syrup from Lou Laird’s little “Blue Room.” Maud gave Ewan drinks of her own homemade wine, but she would not have sanctioned his patronizing Lou Laird. Perhaps she worried that her sons were being corrupted by Lou’s liquor, too.

In Jane of Lantern Hill, Maud disapproves of parents meddling in their children’s love matches. But the writer of fiction had an objectivity that the mother of sons did not. As Maud once told Violet King, writers have no special immunity to human frailty and folly.

When William Arthur Deacon wrote about her books with such lofty contempt, and elbowed her out of the CAA executive, he deprived Maud of doing public service in the world of letters, as well as the celebrity status she had worked hard to achieve.

Deacon lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1977 after long service as literary editor of The Globe and Mail, from 1936 until 1961. In an unfinished manuscript about his influential career, he wrote, “Uniquely among Canadians, Miss Montgomery understood the minds and hearts of adolescent girls, about whom she wrote in a manner completely acceptable to them.” He observed that her books were popular in Japan, and he couldn’t resist remarking that this resulted in Japanese girls writing the literary editor of The Globe and Mail (e.g., Deacon himself), asking to put them in touch with Canadian pen-pals. Patronizing to the end, he added: “The P.E.I. Branch of the I.O.D.E. has shouldered this problem [italics added].”

Readers of Maud’s journals and this biography will ponder over what ultimately brought her to such a sad end. Would different choices have enabled this gifted woman—who wrote books that have brought joy to so many adults and young people all around the world—to find more satisfaction in her own life? Maud herself was addicted to asking “what if?” (see her journal entry of November 25, 1933). In her final years, she began to suspect that she was the author of much of her own misfortune, and she combed her journals for clues. But she was equally given to quoting the Persian poet, Omar Khayyam:

The Moving Finger writes, and, having writ,

Moves on; nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.