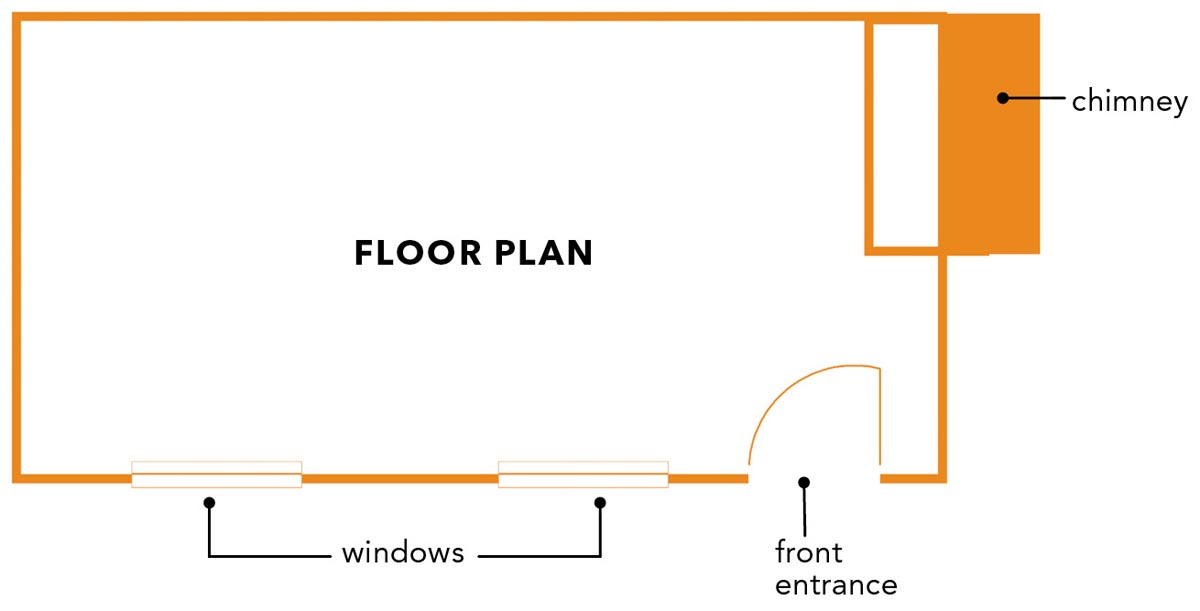

The generic floor plan of a traditional compact home encompasses a rectangular exterior. Ergonomics will guide how the interior is divided into unique spaces — and those divisions will vary depending on personal needs and aesthetic.

This book is about small — that is, small houses. While just a couple of decades ago very big houses were being built at an astonishing rate, the average home size is now shrinking back down. Why? In part, there’s been a stylistic push against the idea of the “McMansion.”

Today’s aspiring homeowners tend to prioritize quality and craftsmanship over size, and they generally allocate their funds accordingly. It’s also true that energy, material, land, and labor costs are rising, and consumers are more aware of the environmental and ecological concerns involved with the construction and maintenance of a home. Given these considerations, building small makes sense.

With the downsizing trend has come increasing pressure to improve the design of the “new” small house. Good home design relies heavily on ergonomics, the science of designing our built environment — from the home itself to its furnishings and appliances — to fit the function, movement, and comfort of the human body. Ergonomics is a particularly important consideration in the design of small spaces. Our satisfaction with a compact home is linked directly to how well the space is designed for our needs and comfort. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at the particular areas of concern in the design of a compact house.

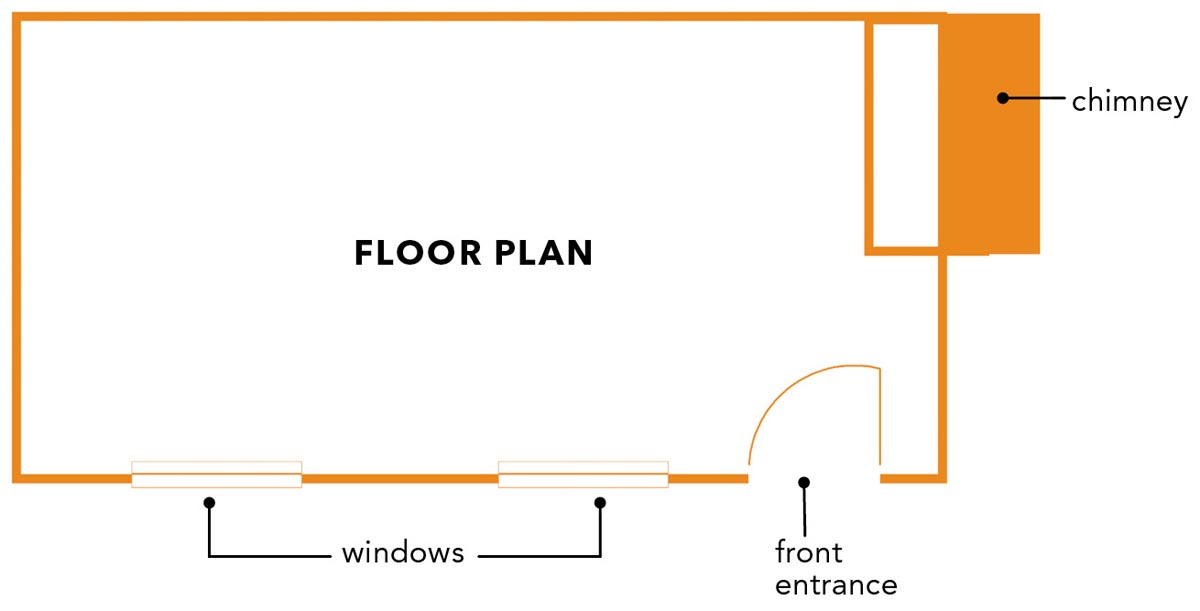

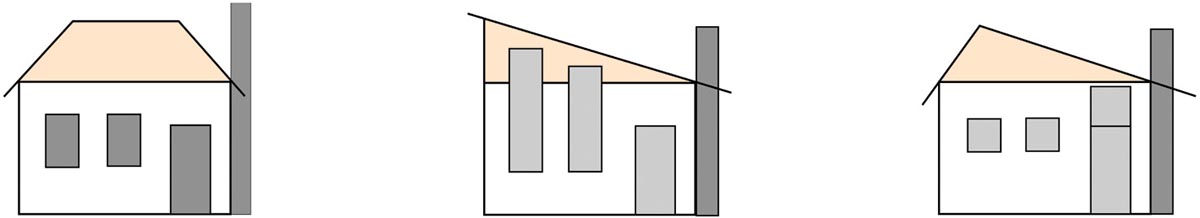

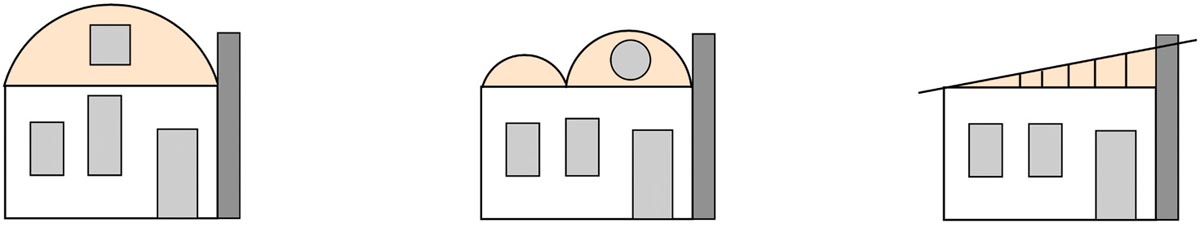

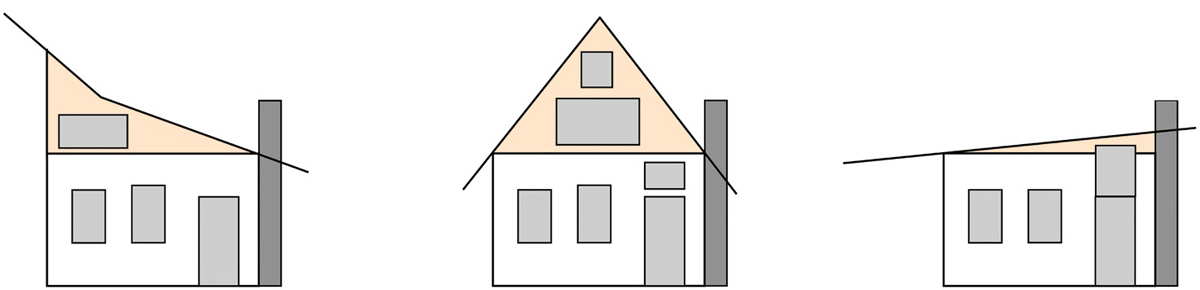

There are two ways to look at a house design: a floor plan and an elevation. The floor plan usually determines the square footage of the building and the relationships among its parts (the kitchen, bathroom, bedrooms, and so on). The elevation is the facade of the house, or what you see from the outside.

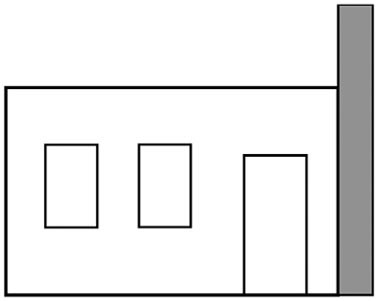

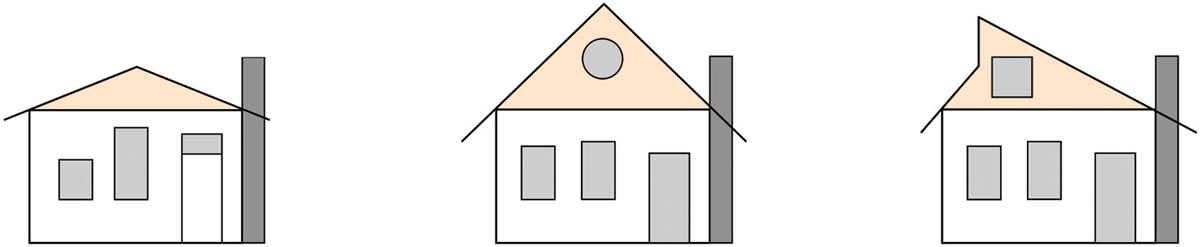

As a general rule, floor plans are about ergonomics, or the ways in which people move in and inhabit the space. Elevations are generally about style. Any small-house floor plan may have a dozen different elevations that would work with it, just as any elevation may work well with a dozen different floor plans. Each pairing of floor plan and elevation yields a unique melding of style and ergonomics.

The generic floor plan of a traditional compact home encompasses a rectangular exterior. Ergonomics will guide how the interior is divided into unique spaces — and those divisions will vary depending on personal needs and aesthetic.

These two concepts — ergonomics and style — begin with the basic structure of the home (the floor plan and elevation) and carry on down through the smallest details. Ergonomics guides the placement and size of the furniture, while style determines the look and character. Ergonomics guides the selection of flooring in the kitchen, while style determines the exact material and color. As design concepts, ergonomics and style are separate considerations, each guided by different concerns and principles. In good home design, however, they are inextricably linked, each shaping the other in the development of a home that suits the particular needs and tastes of the individual homeowner.

The elevation shows the style the designer envisions for the home. But when you’re looking at a plan, keep in mind that the style is mutable; without changing the floor plan, you can significantly change the look of the house.

Varying the roofline and windows yields an almost limitless number of designs, even for a simple rectangular home.

In a home, good design functions on a number of levels, from ergonomics to aesthetics. It should satisfy the social, economic, and stylistic needs of the home’s occupants. In particular, good design is:

Innovative, yet practical. It takes advantage of modern design principles and technology. It is not, however, innovative for the sake of being innovative. The innovation should add to the livability, function, and aesthetics of the house.

Aesthetics. A well-designed house should be beautiful (at least to the home’s occupants).

Understandable. The house should have a human logic. Its spaces should flow naturally from one to the next, and its appliances and layout should allow it to function easily.

Unobtrusive. The house should fit well into its environment and not overwhelm its occupants with furnishings and landscaping. All the components of the house should feel married to one another.

Honest. The house does not make itself seem more innovative, powerful,or valuable than it really is. It has a directness and clarity of thought and expression.

Long-lasting. The design avoids kitschy or fashionable statements, which tend to be short-lived. Good house design should last for years and still be considered tasteful.

Given thorough consideration. The space is designed down to the last detail. No decision about any aspect, from the number of bathrooms to the lighting of the basement to the capacity of the dishwasher, is arbitrary.

Environmentally friendly. Good design minimizes waste and pollution. It allows a house to be environmentally friendly and as green as is practical.

Simple. Less is more. Good design concentrates on the essential aspects of the use and function of the home. The best solution is usually the simplest solution.

When you’re designing a small space, there are some general practices that will make the space work well and be eminently livable. Use these principles to guide the development of your home design, from the overall structure to the individual rooms, always keeping in mind the two main areas of focus: ergonomics and style.

Sometimes you’ll hear the words design and style used interchangeably. They are not the same. Design deals with space, structure, and ergonomics. Design uses a logical structure to tackle problems of organizing living space so that it functions well and meets the needs of its inhabitants. Design is guided by ergonomics, economics (budget), the intended use and function of the space, and the inhabitants’ personal sense of style.

That sense of style, itself just one consideration of the design, is an egocentric, personal aesthetic that guides what a structure looks and feels like. Style arises from our own experiences and creativity. Style determines whether we have a taste for Queen Anne, Bauhaus, midcentury modern, contemporary, or some fusion thereof. While good design determines every facet of a home, style is more a decorative perspective that permeates the structure. Of necessity, good design fuses style with appropriate technology to create a comfortable, functional, practical home. If your taste runs to American colonial, for example, you might furnish your home with chairs and tables of the colonial style, but you’d find a historically correct colonial kitchen almost impossible to work with. The same holds true for utilities and bathrooms — unless, of course, you actually prefer an outhouse.

Especially in a small home, where ergonomics is key to comfortable living, every detail — from the layout of a room to its lighting to its wall color — must serve a purpose. And so your primary objective is to make each detail serve the function of the space. Every aspect of a kitchen, for example, should serve the greater purpose of cooking and serving food. If you want a convivial kitchen, one that invites people to join the cook and share in the meal preparation, then the kitchen must also be designed to function as a gathering place. And from these functions follows the form — from the layout, appliances, seating, and technology down to the atmosphere and aesthetic you want to feel in that kitchen.

This is not to say that a compact home is by nature utilitarian. Far from it. Just ask the Shakers, renowned for the beauty and craftsmanship of their buildings, furniture, and tools — and dogmatic believers in the philosophy of “form follows function.” A home that is highly functional is all the more beautiful for being easy to live in.

Recent years have seen a boom in the design and building of recreational vehicles (RVs). It’s now a very competitive market, with manufacturers vying to outdesign each other in terms of both technology and ergonomics. Since an RV is by nature compact, its components are compact as well, and many of these components translate well in a compact home. And since RVs are popular with an older population, comfort is an important factor in furniture design. So if you’re looking for compact furniture, it may be worth your time to visit a local RV dealer and see the offerings.

I use some RV innovations in my own home. One of my favorites is a telescoping, folding towel rack. In the folded-up position it collapses against the wall and takes up little space. I mounted it on the bathroom wall and use it to hang wet clothes for drying. It also serves to hold extra towels for guests.

To feel comfortable, a home must exude a sense of both space (the ability to move freely and unhindered) and containment (each space’s boundaries and purpose defined). Balancing the two concepts — flow and boundaries — allows a compact home to be comfortable and functional. Here we return to that concept of gestalt: the way in which the spaces work together determines the livability and functionality of the home.

Always start with the structure and, again, ergonomics. A small home should not comprise a series of small, walled-off rooms. But to avoid the feeling of a boxy warehouse — and yes, even a small home can feel too open — some definition of spaces within the home is needed. Not necessarily walls, mind you; a boundary can be as simple as a change in wall color or texture, or a ceiling beam that spans the divide between the living area and the eating area, or a unique tile floor that defines the expanse of the entry. A person moving from one space to the next should be able to see or feel the point of transition.

Each room should also allow appropriate movement within it and into other spaces. From a living room, for example, you may want easy access to the kitchen or eating area — or perhaps even open access, with the living, eating, and kitchen areas open to one another. A bedroom, on the other hand, is more often a private space, enclosed by walls and given its own door, but you’ll want to consider its proximity to the bathroom. If someone waking in the bedroom at nighttime has to cross through the seating area in the living room to get to the bathroom, the bedroom becomes less ergonomic — less comfortable and less easy to inhabit.

One common problem with a small house is the scale of the furniture. Often people who have downsized into a smaller house find that they feel uncomfortable in their new home; it’s hard to maneuver in and feels crowded. The reason? It’s not the reduction in square footage. It’s their furniture — it’s too big. The furniture is scaled to fit a home twice the size of the one they’re now living in. As a result, the people living in the smaller house are uncomfortable and unhappy — and beginning to rethink their move.

Furniture should be scaled to fit the space where it will be used. The idea that furniture has to be large to be comfortable is a common misconception. It is just not true. To be comfortable, furniture needs to be well designed, padded properly, and upholstered with an appropriate fabric. Size is a matter of appropriate scale, not comfort. The problem is that finding smaller-scale furniture can be a bit of a treasure hunt. Most suburban and mall-based furniture stores, being close to developments full of very large houses, stock only large-scale furniture. They are well aware of their market and cater to a certain kind of customer. A better resource for the owner of a compact home is an urban furniture store that caters to the taste and needs of apartment dwellers. Here you will find a very different aesthetic and scale in the furniture.

Housing in many parts of Europe (especially Scandinavia) and Japan is noticeably smaller than the housing we are accustomed to. This means that the furniture is smaller in scale, too. Furniture manufacturers from these countries would be good resources for owners of compact homes.

Of course, here in North America we can find many traditions of smaller houses in our own history. Early colonial through midcentury-modern furniture was scaled to fit small spaces. And if your taste runs to the eclectic, you may find mixing styles very satisfying. For example, Japanese (Zen) minimalism, Scandinavian modern, and American Shaker could all work very well together.

That said, balance spaces with both large and small furnishings. The use of small furnishings alone makes a space seem busy and cluttered. Don’t avoid a couch just because it’s bigger than a chair. A moderately sized couch — or perhaps a loveseat — can become the centerpiece of the living area, with smaller furniture to complement it.

Several summers ago I was in Kyoto, Japan, during celebrations for a Buddhist festival. As part of that festival, most of the ancient Zen teahouses were open to the public. I was profoundly impacted by the minimalist design I saw there. The atriums of the teahouses were usually decorated with a simple low table supporting a porcelain vase with a single flower in it. One primary aspect of the Zen philosophy is that less is more. As the number of objects becomes fewer, the importance of each of the items increases. A single perfect flower is more powerful than all the flowers on the floats in the Rose Bowl Parade. I found I could grasp and appreciate the beauty of a simple flower far better than that of a rose-filled float. This idea can also be applied to living in small spaces.

Rooms should have a focus. They can have a number of elements — windows, window treatments, furniture, artwork, carpeting and floor treatments, and so on — but they should spotlight a primary focus. It might be an interesting Persian carpet or a precious chair inherited from Grandma Ruth. Occupants of the room should be able to recognize the focus, whether because it is the most prominent thing in the room or because it is set off in a way that draws attention to it (on a mantel, for example, or in the center of a seating arrangement). And particularly for a small room, there should be just a single focus. When multiple focal points in a room compete, it makes the room feel unsettling and small.

If the individual elements that we include in our home, such as the colors, textures, furnishings, and artwork, are the words that describe our aesthetic, design is the grammar that organizes this vocabulary into a coherent statement. Words can be just words, but with the right syntax, they can become poetry.

One of the common problems in small spaces that feel uncomfortable and crowded is how they are decorated. Most of these spaces end up too busy, with too many conflicting accents and oversize furniture. Here are a few suggestions to help you build a decorative style that expresses your personal aesthetic in a coherent, sensible, and functional way.

Walls. Start with the walls and work inward. Do you want the walls to be the focus of the room? If not, then an earth tone, neutral color, or pastel would be the appropriate finish. An unobtrusive wall color becomes the palette upon which a more colorful focal point — a richly colored rug, a bright painting, a favorite chair — is displayed. Conversely, furnishings in quiet colors will balance a room whose walls are painted a strikingly rich, warm orange.

Textures. Texture can be as important as color in creating comfortable, engaging, livable spaces. Texture can draw your eye around a space and focus your attention; you will see a textured surface before you see a smooth surface. But as with color, don’t overdo the texture. Restoration contractors will sometimes remove the old plaster from a wall or chimney to expose the brick beneath it. The warm, worn brick makes a good textural accent on one wall, but you wouldn’t want to live with the brick of the whole house exposed; it would become overwhelming and make the home seem smaller than it is.

Window treatments. The style of your window treatments should be dictated primarily by the degree of privacy you need. Privacy is of less concern in the living room of a country house than in, say, a city bedroom. So let privacy be your guiding concern, and then consider whether you want the window treatments to be the focal point of the room or an unobtrusive element.

Flooring. Floors can be tile, hardwood, wall-to-wall carpeting, or area rugs (and certainly other eclectic options exist). Again, ask yourself, what do I want people to see first when they enter this room? A beautiful Persian rug could be the focal point. Then the rest of the decorating in the room has to make this rug the center of interest. Colors that appear in the rug could be repeated or complemented in the colors of the walls, window treatments, or throw pillows. The important thing is that the rest of the room should not compete with this rug for visual attention. Choosing a palette of colors that are analogous to those of the rug will make the room function as a design whole. Then again, if the flooring is not the focal point, it should be of a simple texture and color, so that it won’t compete with whatever you have chosen as the focal point.

Lighting. Your choice of recessed lighting, track lighting, pendants, sconces, accent lamps, or what-have-you (options abound) contributes to the design statement in the room. The primary concern is that the lighting be functional, illuminating areas as necessary: a living room chair needs adequate light for reading, for example, while a bathroom mirror needs lighting set over it, and a kitchen needs good lighting over each work area. Lighting can also be thought of as mood setting, adding to the overall atmosphere in the room.

Furniture. The size of the furniture and the number of pieces in a room are important considerations. Your taste may be antique, eclectic, contemporary, or period; that’s your choice. But as discussed earlier (see page 118), the furniture must be scaled appropriately to the size of the room. In a compact home, that usually means compact furniture. Oversize furniture would make a compact home feel crowded and claustrophobic. Too much furniture in a room would produce the same result. How you arrange the furniture is a question of ergonomics: how will people use the space, and how can the furniture placement make that space comfortable and functional?

Remember: keep it simple. In most things, there’s a natural tendency to evolve from simple to more complex. Knowing this, start out with the simple, allowing your home to naturally evolve into something more complex over time.

Go almost anywhere else in the world — Asia, Africa, Europe, Central America — and the prevalent philosophy in architecture and consumer culture is one of minimalism driven by need and ergonomics. What do we really need to live happy, fulfilled lives? It’s surprisingly less than what most of us currently live with.

Any life coach, Zen master, motivational speaker, or other “good life” cheerleader will tell you that it’s the relationships we treasure, the experiences we navigate, and the mind-set we cultivate that lead to a happy, fulfilled life. And they’re right, of course. But this book is about houses, and so here we’re going to talk about our physical stuff: the tools, furnishings, accessories, and mementos that share our living space and, with any luck, make positive contributions to our lives.

Living well in a small space necessitates a certain prioritization of our belongings. We keep what we need and absolutely love; we lose the junk and the belongings we don’t really use. For some of us such minimalism comes naturally — we have a spare aesthetic in our personal lives and tend not to accumulate belongings. For others, seasonal purging is a welcome relief, offering us a chance to declutter our environment and bring clarity and space to our lives.

In a small home, space is at a premium, and we must use every inch of it with conscious intent. We’ll talk more about space-saving storage and design features later, but the first step is simply to declutter. Evaluate your belongings with a steady, unbiased eye. Get rid of those tools and appliances that you don’t use on a regular basis or, if they perform some irreplaceable but not-often-called-for function, set them aside to put in storage. Pare down your knickknacks and mementos to those that you truly love; if you’re left with an overabundance, consider displaying them in rotation, switching out one set for another every few months. And for more good tips and advice, consult any of the many good books now available on decluttering and simplifying.

The benefit of simplifying is that you’re able to demand good design and high quality from those things you do own. With any luck, that focus will bring all-around greater usefulness, ergonomic function, and enjoyment to your life.

No discussion of the ergonomics of small spaces would be complete without a look at Usonian architecture. The name came from Frank Lloyd Wright, referring to his vision for building affordable, stylish homes for the common people of the United States (U.S.-onian), as an alternative to the term American. This style of architecture was born during the Great Depression and continues evolving, albeit under different names, even today.

In the mid-1930s, breaking from traditional colonial designs, Usonian architecture adopted the Bauhaus concept of “form follows function,” basing home design on the needs of the occupants, which indeed were different from those of homeowners in decades past. Central heating systems, modern kitchens, and storage needs were evolving. Garages and carports were increasingly attached to homes, in contrast to carriage houses, which generally stood some distance from the house (due to the smell of the horses). And, pushing back against Victorian ideals, the Bauhaus movement favored the notion that good design was of itself aesthetically pleasing and didn’t require additional ornamentation.

Usonian houses were built on one level, set on a concrete slab without an attic or cellar. Instead of having a number of small rooms, as was the contemporary fashion, they emphasized an open-concept living space, accompanied by small bedrooms. The kitchen, dining, and living rooms flowed together in one area. The houses were designed to minimize the need for doors and halls.

Many Usonian houses were among the first to utilize what have become standard elements of green architecture. Some made use of radiant floor heating, for example, with heating pipes embedded in the concrete slab. Some were designed with large roof overhangs, which made ventilation possible even in wet weather and, due to the seasonal change in the angle of the sun overhead, blocked midday summer sun from the house while still allowing in midday winter sun. As a result, these houses were naturally cooler in summer and warmer in winter. (Some of the earliest passive solar house designs were Usonian.) Many employed clerestory windows for natural lighting. Most made great use of wood, brick, stone, and other natural building materials and were designed to echo the forms of the local landscape.

Usonian architects also oriented the houses on their lots differently than in the past. They tended to build on odd-size or less desirable lots to keep costs affordable. They positioned houses farther back on the lots to help reduce the noise from automobile traffic on the street. And they relocated and reoriented entrances to accommodate the fact that occupants of the house and visitors would arrive by car.

The lives and lifestyles of Americans were in flux after the Second World War, and this new architecture met the needs of a modern culture. Many of the concepts developed in this architectural style have endured; they are very applicable to the needs of contemporary house design.

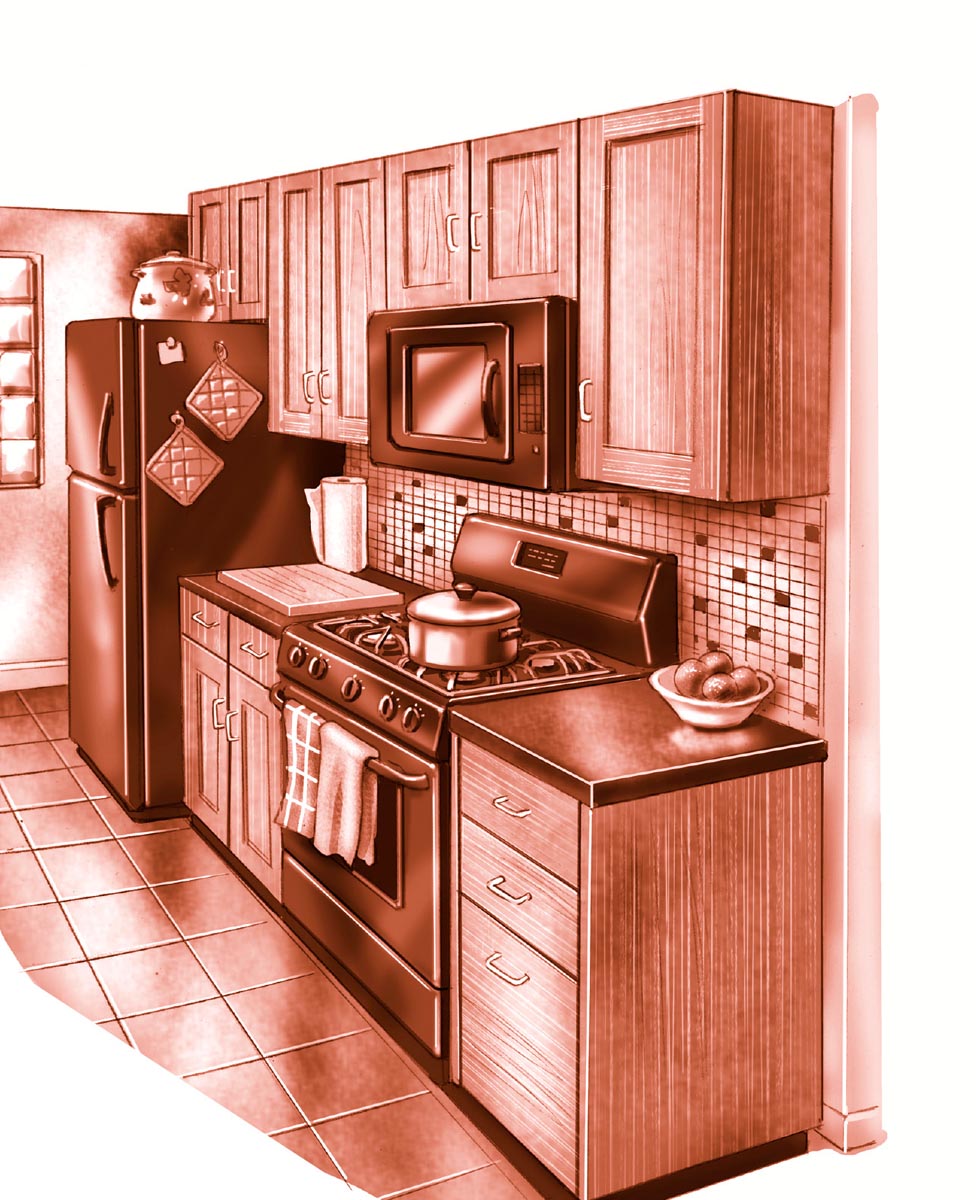

The kitchen is a central place in the modern home, having evolved from a utilitarian space for cooking to a more social space used not just for cooking but also for eating, socializing, homework, and other activities. To serve these expanded functions in a compact home, a kitchen must be designed to fit the specific needs and cooking style of the homeowners.

If you don’t cook much, you can have a very compact kitchen, with a two-burner stove, compact fridge and other appliances, and minimal counter space, like you might find in a hotel suite. If you want a full-size kitchen, spending time up front looking at your options and planning the layout and style will ensure that your kitchen serves you well for years and years to come.

I grew up working in the kitchens of resorts in the Poconos of Pennsylvania and the Catskills and Adirondacks of New York. Though they fed hundreds at a time, these resorts had fairly small kitchens. Most of them were designed according to the classic kitchen “work triangle” philosophy: arranging the stove, refrigerator, and sink in an equilateral triangle, with the smallest practical distance between them. The idea was that the kitchen would be more efficient if the chefs did not have to move around a lot to prepare the meal. Everything they needed — utensils, pots, pans, seasonings — was available in their immediate work space. And everyone had their own station. Prep cooks, sous chefs, and line chefs could work efficiently without interfering with each other. There was an assembly line: the prep people passed the product along to the sous and line chefs, who passed it along to the servers. Chefs were able to produce meals efficiently and without undue fatigue in those kitchens.

Kitchen designers today debate whether the work triangle is an outmoded concept. With the preponderance of new appliances that have become standard (think of the microwave, toaster, coffeemaker, and countertop stand mixer), the fridge, oven, and sink are no longer the only elements in a kitchen. But the philosophy behind the work triangle — that all the primary appliances and workstations should be readily and efficiently accessible to the cook — remains irrefutable, and it becomes especially important in the design of a small kitchen. Which brings us back to the study of ergonomics.

Consider the primary fixtures in your kitchen. Perhaps they are the refrigerator, stove, and sink (the basic elements of the classic work triangle). Perhaps they also include a microwave, a separate cooktop, or some other appliance. For maximum usability, each fixture needs accessible counter space. And ideally, because it’s irritating to keep bumping into people while you’re cooking, any traffic in the kitchen should flow outside the perimeter of the primary-fixture work space (whether it forms a triangle or otherwise).

Keep in mind that the two primary fixtures people most often need to access, even if they are not involved in the cooking, are the refrigerator and sink. If possible, locate these two fixtures toward the outside edges of the work space so that people can get to them without venturing too far into the cook’s domain. The same holds true for the silverware drawer.

Set up the work area around each primary fixture like a station. Just as you’d keep dish soap and sponges near the sink, you’ll want pots, pans, ladles, spatulas, and other stovetop tools near the cooktop. The primary prep station should have ready access to the knives, cutting boards, peelers, measuring cups, mixing bowls, seasonings, and so on. Think about the tasks you’ll do at each station, and outfit each station accordingly. This maximizes usability and efficiency and minimizes time spent rummaging around.

As an example, let’s take a look at my own kitchen. It’s a Pullman-style kitchen, which means it runs in a straight line with a relatively narrow aisle down the middle. Against one wall are the refrigerator, prep station, and stove. The prep station is a simple countertop for cutting, chopping, and so on. Above it is a cabinet that houses seasonings, spices, and condiments. Below it are drawers that contain cutting boards, knives, spoons, vegetable peelers, spatulas, and so on — essentially those things needed to cook or prep food. Below the drawers is a cabinet that holds pots and pans.

The idea is that the food moves along an assembly line, from the refrigerator to the prep area and then to the stove. To the right of the stove is a small countertop for staging the serving of food; the cabinetry above and below this countertop houses serving bowls, serving plates, and so on. Under-counter drawers here store eating utensils, serving spoons, and so on.

Directly across the center aisle from the prep station is the sink. Next to the sink is another prep station with a cutting board, food processor, and large stand mixer. This station is dedicated to any food prep that would involve the sink or baking. Again, there are cabinets and drawers above and below the prep station.

This is a very efficient and compact kitchen layout. And the kitchen is open to the living area, so that the cook can stand at the stove and socialize with people in the living area.

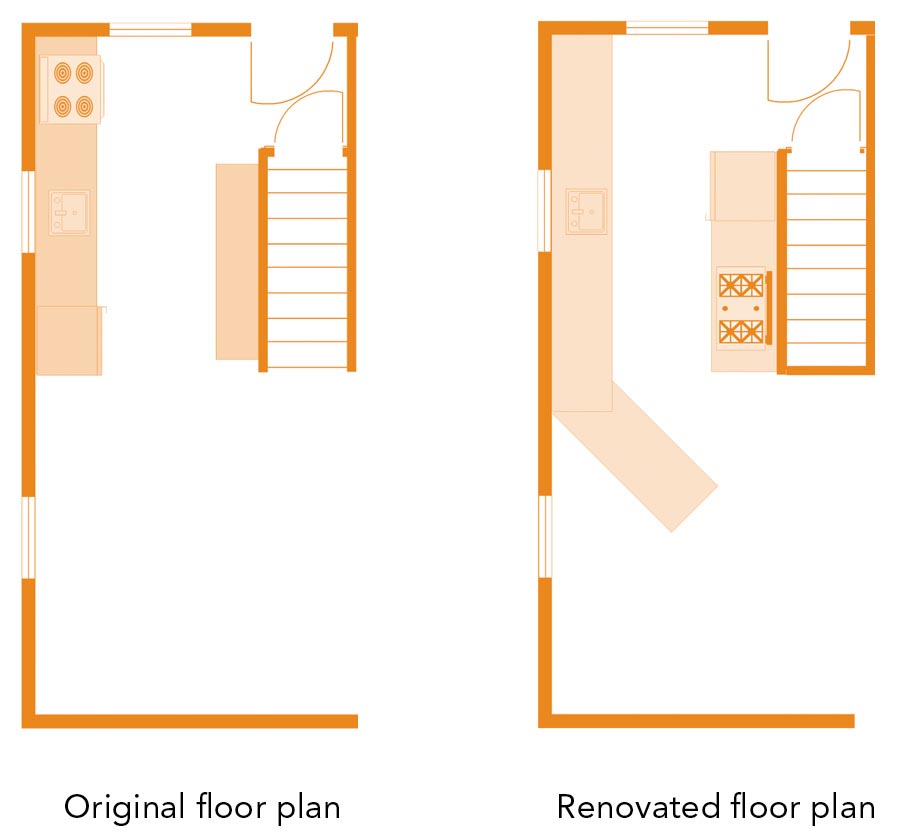

The floor plan: The original Pullman-style kitchen was cramped and hard to work in. The refrigerator, sink, and stove were grouped on one side, with an open countertop on the opposite side. Moving the fridge and stove to the opposite side gave each appliance adequate counter space and created prep stations. With this new setup, cooking is efficient and enjoyable.

Exterior wall: The renovated kitchen features a long expanse of open countertop for food preparation, along with a table that angles out from the wall, allowing diners to sit at both sides without obstructing traffic.

Interior wall: On the inside wall, the stove is flanked by more countertops, with cabinetry above and below housing all the necessary tools for stovetop cooking.

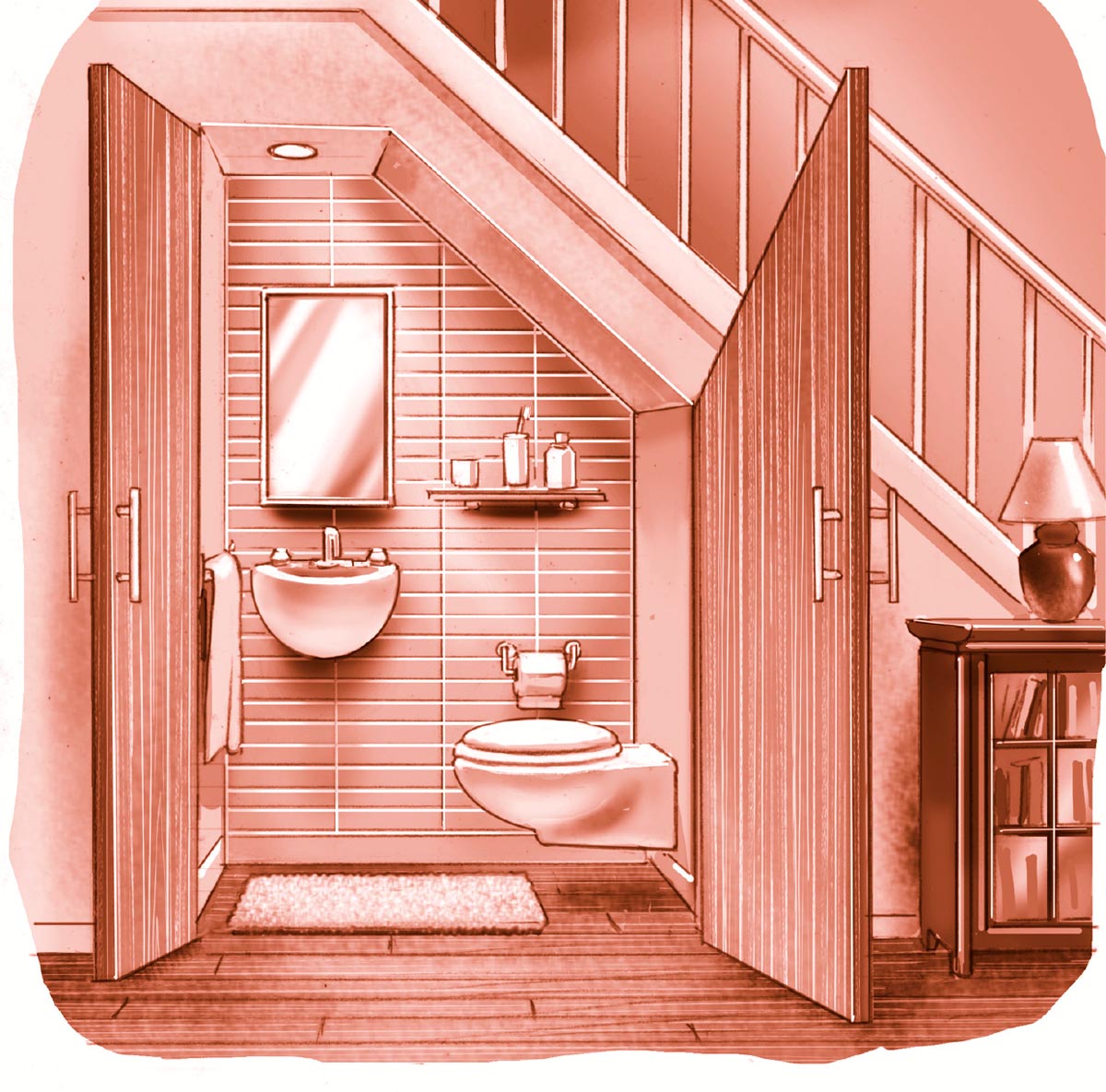

The size and luxury quotient of the bathroom should depend on the priorities of the homeowner. You may want a deluxe bathroom with a spa, rain shower, and double sinks, or you may decide upon a more utilitarian setup with a compact shower, sink, and toilet. You may want two bathrooms, or even three. If you have young children, you may want a tub. If your family spends a lot of time playing or working outdoors, you may want a half bath near the main entrance, so you can wash up easily without tracking in dirt. A micro powder room as part of a mudroom would be a great convenience.

Regardless of your particular priorities, know that you can have a well-appointed bathroom in a very modest footprint. The fast-paced evolution of design for RVs, apartments, and other small living spaces has led to sometimes radical innovation in the bathroom. You can find wall-hung toilets that extend as little as 20 inches from the wall, and sinks that extend as little as 11 inches. Toilet manufacturers are even beginning to make integrated toilet-sink combinations, which are very compact and environmentally friendly to boot, since they use the wastewater from the sink to fill and flush the toilet. In some incredibly compact models, the sink replaces the lid of the toilet’s flush tank. With these compact fixtures, you can convert a space as small as 12 square feet into a half bathroom. That means you could house the bathroom in the space under the stairs or in a small closet. (But note that local building codes vary in terms of how much space they require to be allotted to bathroom fixtures; you’ll want to check with your local building department before you begin to do any real design work.)

Using fixtures designed for small spaces, such as a wall-hung toilet and slim-profile sink, a bathroom can be fit under a staircase or in a space the size of a closet. This micro powder room offers all the amenities of a half bathroom, in half the space.

Of course, size isn’t the only consideration of bathroom design. Ergonomics and style are again the primary guiding principles. Above all else, a bathroom should be easy to use, comfortable, and inviting.

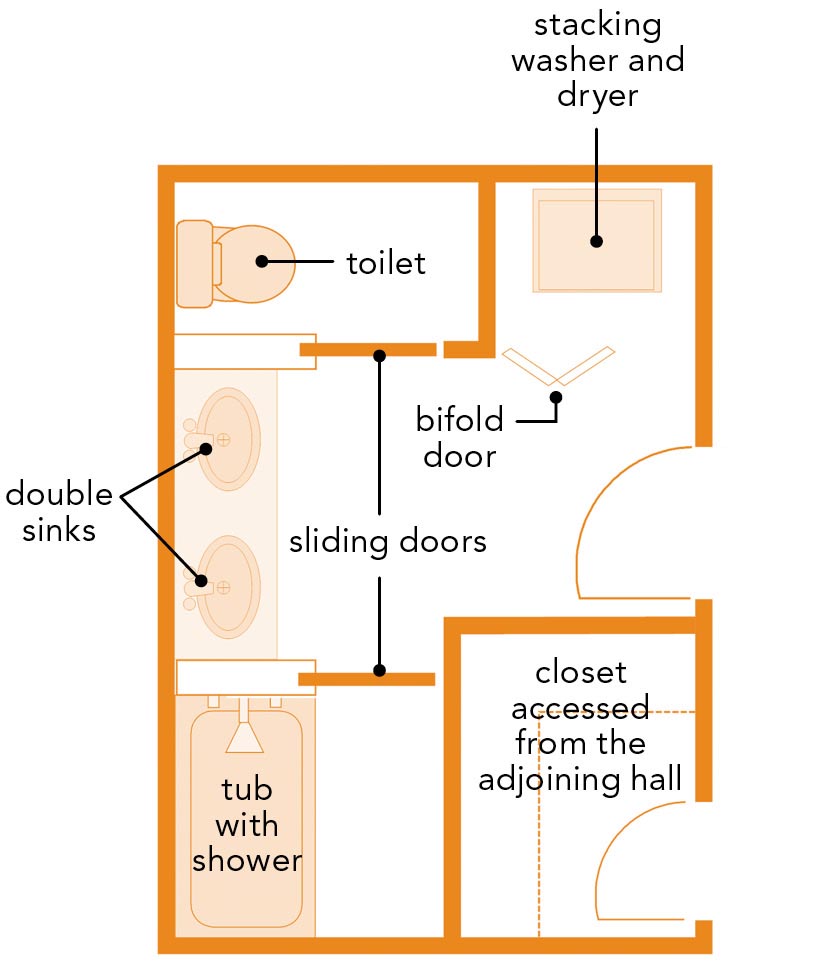

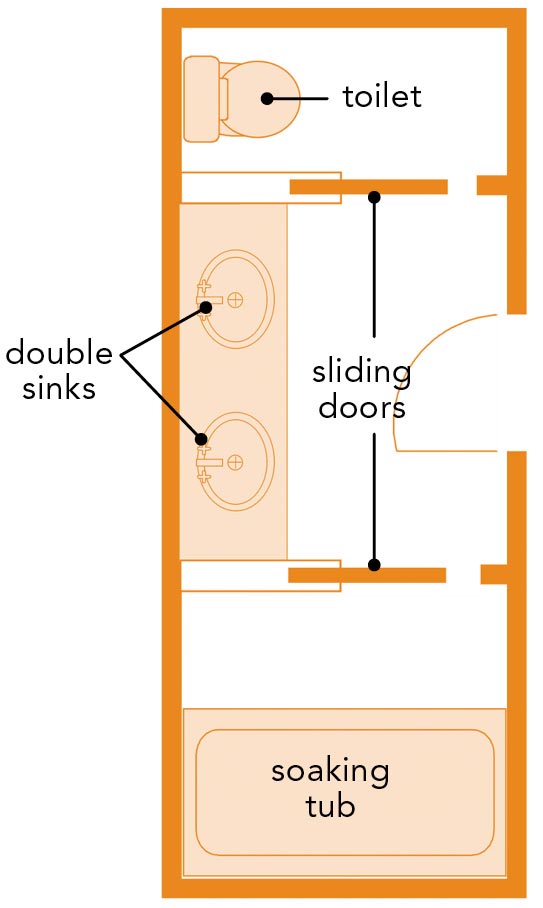

Sometimes it helps to look outside the common expectation to see what other cultures consider to be good ergonomics and style. Take, for example, the Japanese conception of the bathroom. Here in the West we think of a bathtub as something to get clean in. In Japan a tub is for soaking, and you clean yourself before you enter the tub. We place the tub (or shower), the toilet, and the sink in the same room. This setup would be unthinkable in a traditional Japanese bathroom; there, each of the bathroom fixtures would have its own alcove or room. The tub, which would be a soaking tub, would be in a separate area from the toilet, and the sink would be in yet another space. The bathroom would also include a “scrubbing” station, usually a low stool with a shower wand close by: you sit on the stool, scrub yourself with a loofa sponge or scrub brush, and use the handheld shower wand for rinsing. Only after a thorough scrub would you use the soaking tub. The bathroom floors and walls would be tiled with floor drains. Since everyone using the tub is already clean, several family members might use the same water. This would save on both water and the energy to heat it.

The Japanese setup might seem byzantine, but let’s examine it in light of a small house with only one bathroom. The space where you enter the bathroom houses the sink. (This area could also house a stackable washer and dryer.) A door on one side leads to the tub, and a door on the other side to the toilet. I think this seems like a very practical idea, and a good way to extend the use of a single bathroom. Someone could soak in the tub undisturbed, even if someone else needed to use the toilet. Anyone wanting to wash his or her hands could do so without disturbing either the person in the tub or the person using the toilet. With an exhaust fan in the toilet room, a particular social anxiety about using a toilet in the same space as other people could be eliminated.

For sheer convenience, I would recommend a Japanese-style bathroom for at least one of the bathrooms in any home. It’s the epitome of ergonomic design, merging functionality with comfort to enhance the experience of the user.

Like any bathroom, a Japanese-style bathroom can be configured in many different ways. The main point is that the toilet, bathtub, and sink are each in their own space. Entry to each space is usually guarded by a sliding door, for the simple convenience of saving space.

A Japanese-style soaking tub is usually small, deep, and square. It’s a real luxury in any bathroom.

In a compact home, bedrooms are normally modest in size, leaving most of the home’s footprint to the common spaces such as the living room, dining area, and kitchen. “Modest” does not have to negate the possibility of elegance and ergonomics, however. Many of the plans in this book call for a master bedroom with a private bathroom, a modern luxury that is especially appreciated by parents sharing a home with their children. And all of the plans strive for an ergonomic bedroom layout, with ample closet space, good traffic flow, and furnishings arranged with an eye toward usability and style.

The bed is likely to be the main furnishing in any bedroom, and which type goes into which bedroom (or sleeping area) will depend on who will be using the bed, and how often, and how much of the floor space you wish to allot to the bed. A couple will normally prefer a full- or queen-size bed. (A king-size bed is not out of the question, even in a compact home, but it does take up more floor space.) Children may find great delight in a bunk bed. A home office can double as a guest bedroom with a small sofa that converts to a bed when visitors arrive.

If you don’t want to allot any of your home’s footprint to guest quarters, you might think about investing in pullout sofas for your living room. Pullouts have long had a bad reputation for being uncomfortable beds, giving rise to backaches and crabby mornings. But over the past decade or so there have been significant advances in the design of the bedding portion of these sofas. Today they are nearly as comfortable as conventional bedding. Three of the sofas in my house are pullout sofas; this means I can accommodate an additional six people if necessary.

Some of the more unusual, space-saving bed designs include the following:

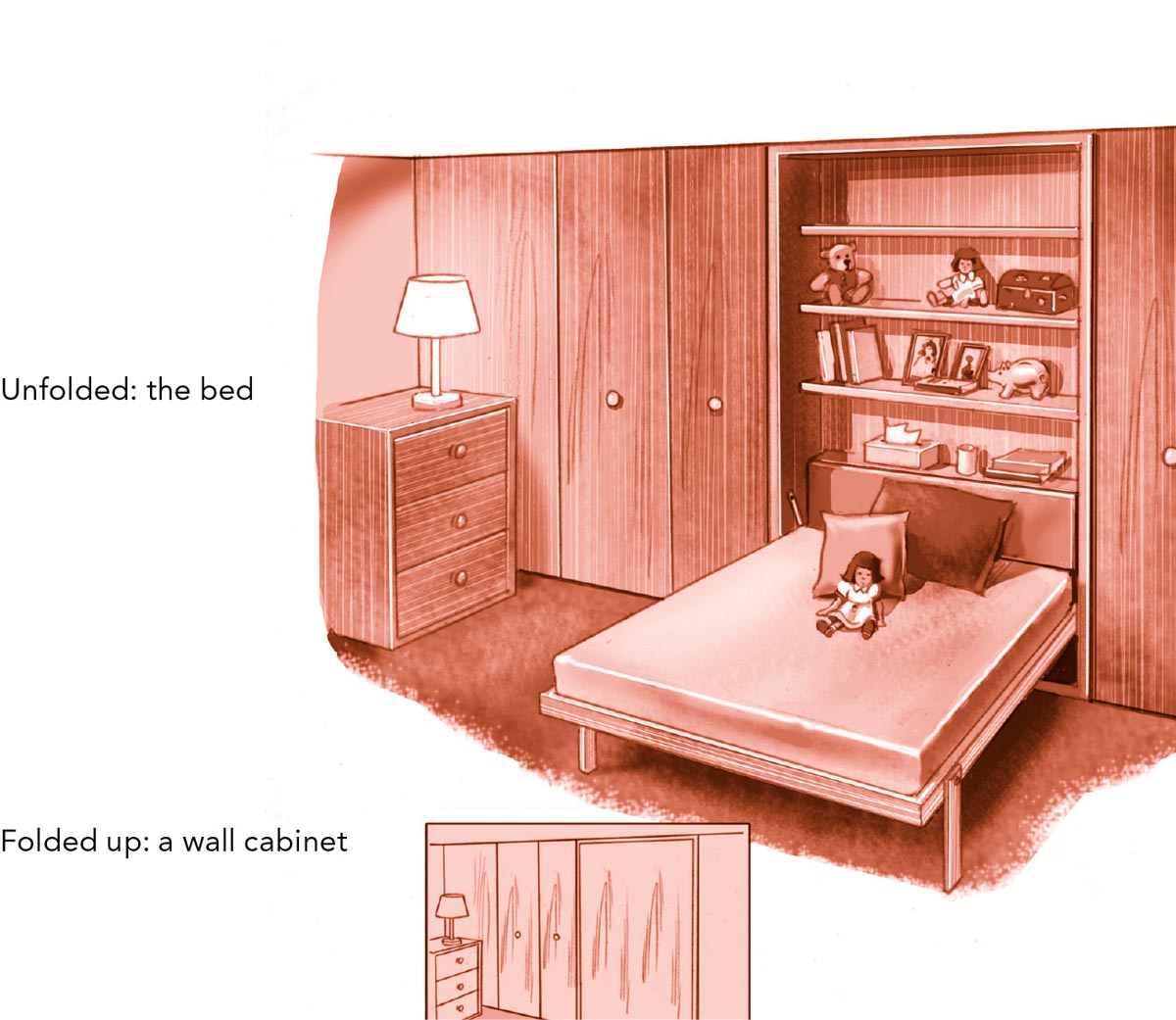

Murphy-style beds. Murphy beds (below) fold up into a wall cabinet of some type, effectively concealing themselves when not in use. They first came into vogue in urban apartments in the 1920s and ’30s. Today they are making a comeback, and they are available in a number of configurations. They can be designed to fold up either from the end or from the side. Some are part of a wall unit that can include dresser or nightstand space. You can even find bunk beds in the Murphy fold-up style.

A traditional Murphy-style bed folds up into a wall cabinet. When unfolded, the cabinet “headboard” may house shelves, lights, or any number of other fixtures.

Even bunk beds are available in the fold-up, Murphy-bed style, and they make great sleeping quarters for visiting kids.

Suspended beds. Some manufacturers are now promoting a bed engineered to be suspended from the ceiling and raised and lowered electronically. In the raised position the bed resembles a shallow rectangular box attached to the ceiling. In the lowered position it appears to be a conventional bed, without a bed frame, resting on the floor. This is a great alternative to the Murphy bed if you have high ceilings.

Trundle beds and daybeds. A trundle bed is defined as a single bed that is housed beneath another bed. The trundle bed is simply pulled out when it’s needed, either to be used on its own as a single bed or to convert the overhead bed into a double bed. This style of bed is ideal for a child’s room (sleepovers, anyone?) or in a guest room. It also works well in a home office, with an overhead daybed. With large throw pillows, the daybed affords a private sofalike space for reading and relaxing, and the trundle bed allows the office to double as a guest room that can accommodate two people.

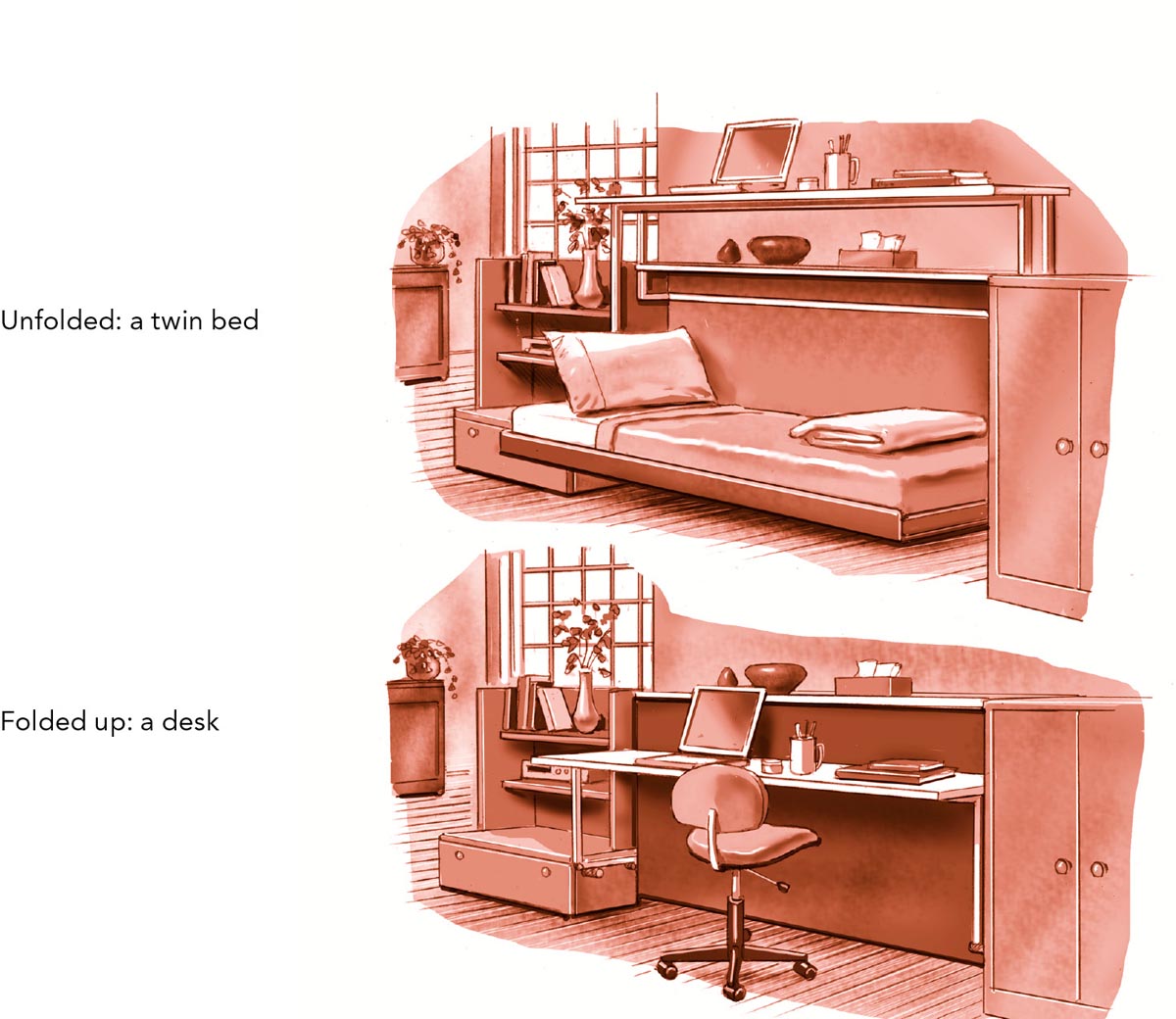

Pullman-style beds. Another bedding innovation that applies itself nicely to small houses is the Pullman-style convertible bed, which was made in numerous variations by the Pullman Company for railway sleeping cars around the world. During the day, passengers could sit on a built-in couch. At night, they could pull up and latch the seat back into a horizontal position over the seat cushion, making a bunk bed. There are versions of the classic Pullman bunk bed available today (they’re especially popular on cruise ships), but you can find convertible beds in all shapes, sizes, and configurations. Many convert from seating to beds, but others begin with anything from desks to shelving that convert to beds (page 135).

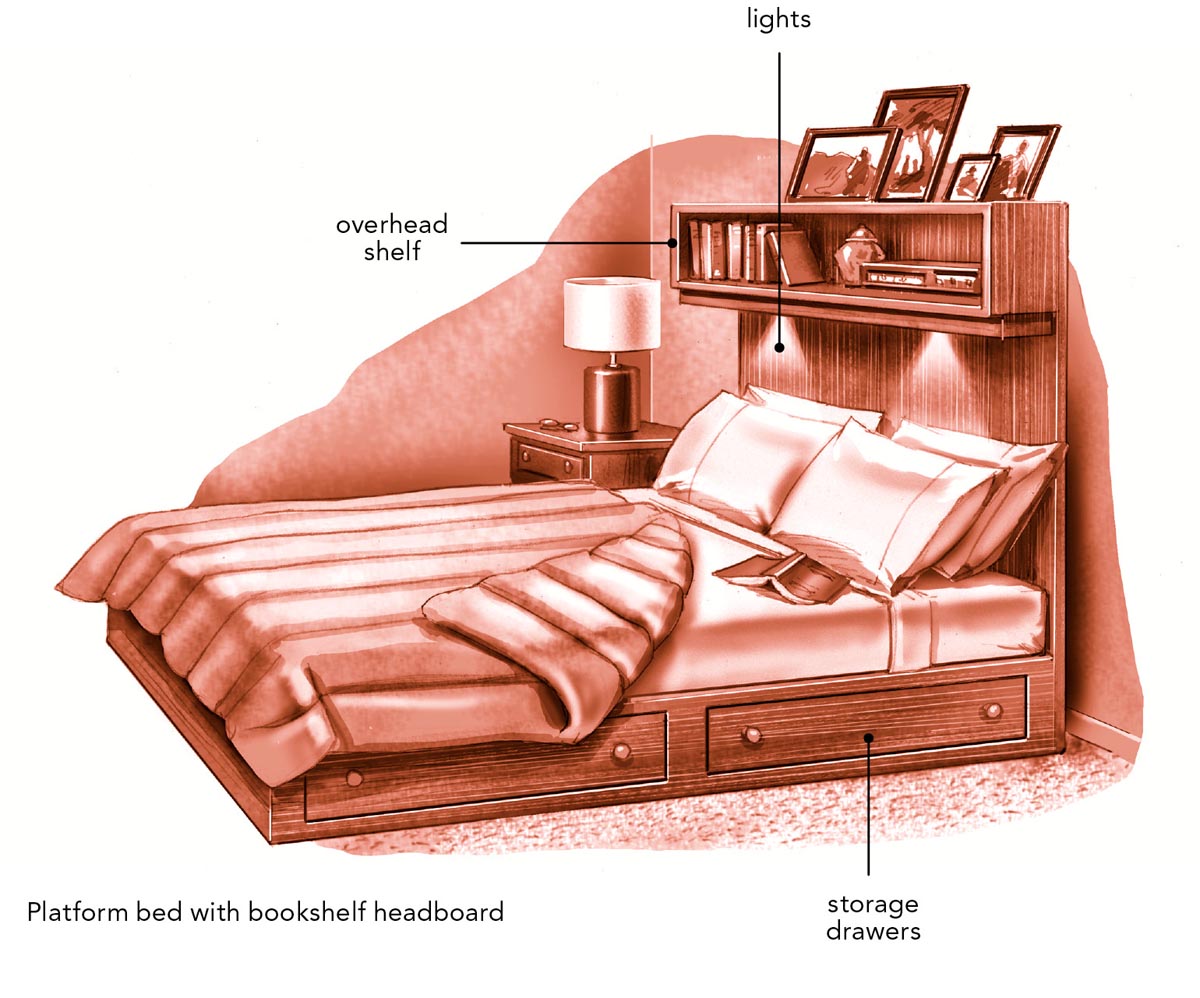

A platform bed can provide multifaceted storage for a compact bedroom. Clothing or other belongings can be kept in drawers beneath the bed, while the overhead shelf is the perfect spot for clocks, cell-phone chargers, and reading material, and it can be fitted with reading lights beneath. (For more built-in storage options, see page 139.)

Some styles of fold-up beds convert from beds to desks or tables. They’re popular in studio apartments, and they work well in a home office that doubles as a guest room.

Modern furniture manufacturers are producing a wide range of convertible beds, such as a stacking version that converts from a couch to a single bed to a double bed.

In a compact house, the dining area is often integrated with, or open to, the kitchen to maximize usability while minimizing footprint. As with the dining area in any size home, a sideboard or hutch is helpful for housing utensils, serving dishes, napkins, and the like — and storing these items in the dining area leaves room for storage of pots, pans, and other cookware in the kitchen. But of primary importance, of course, is the table.

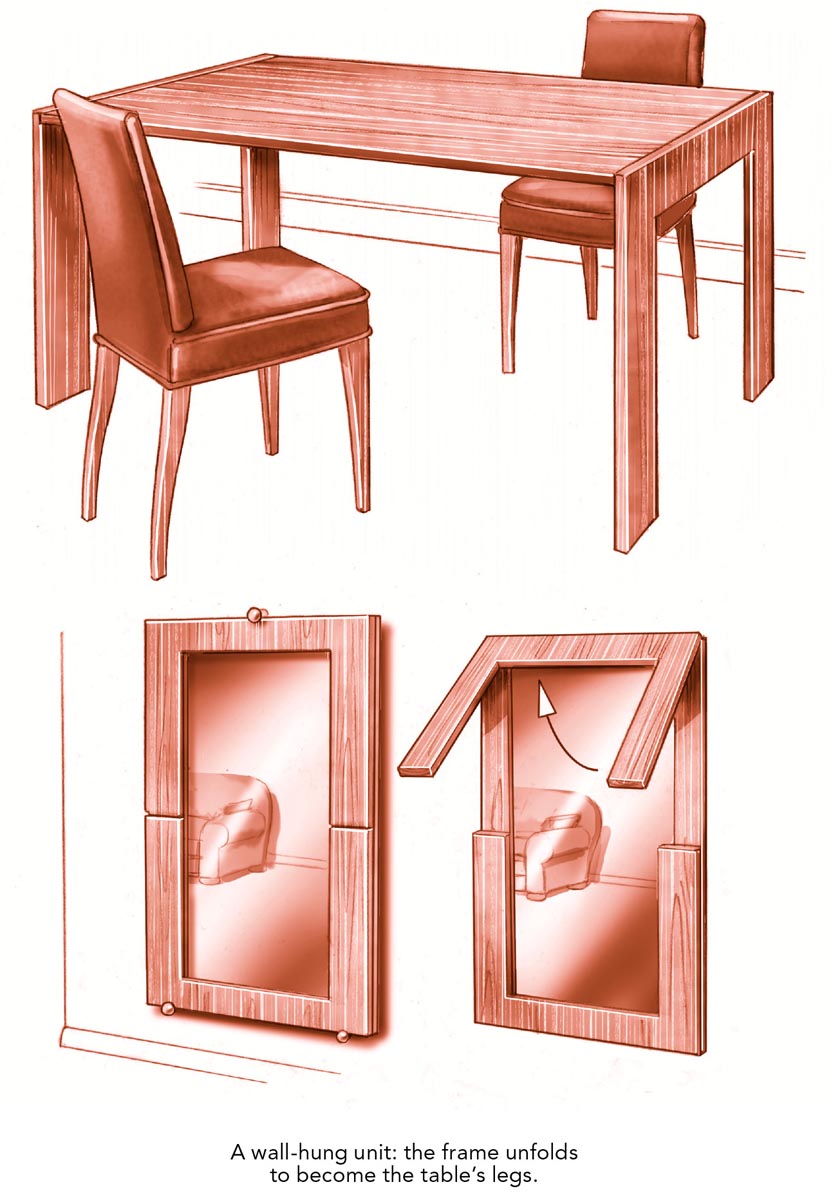

In general, it makes sense to size the dining table for the number of people who will usually be eating at it, but to be able to expand the size of the table to accommodate guests. You might consider a drop-leaf table, with a leaf (or leaves) that folds down against the legs. Or you may prefer an extension table, with removable leaves that can be stored in a closet when they’re not in use. Folding tables are another good option, and we’re not talking here about flimsy card tables that rock like an earthquake when you lean your elbows upon them. You can find sturdy, stylish, modern folding tables from most furniture manufacturers. Some even fold up into chic cabinets that you can hang on the wall in the dining area — the perfect storage solution!

If you occasionally need extra table space, look to the modern folding table, which is portable, sturdy, and compact in storage. Some versions even fold up into a wall-hung unit; the underside of the table could house a mirror, and the frame unfolds to become the table legs.

When you do expand your dining table to accommodate guests, they’ll need chairs to sit in. Like folding tables, folding chairs have come a long way since their card-table days. These are not your grandmother’s folding chairs. Today you can find them in a variety of styles, colors, materials, and finishes. Many are meant for everyday use, not occasional use, so they’re sturdy, comfortable, and stylish. The fact that they fold up is simply a feature that makes them portable.

I once lived in a house with a small second-floor porch. It was a nice spot for reading, up and away from the noise of the street. It also faced east and had beautiful morning light, and I wanted to set it up as a space for weekend breakfasts, but without crowding the porch with furniture. So I set up the porch with patio-style cushioned chairs for reading and relaxing. I then invested in a table and chair set: a double drop-leaf table and four folding chairs that could be stored beneath the table when the leaves were dropped. A shallow drawer under the tabletop could be used to store placemats and utensils. The table was on casters and could be rolled to the side, to function as a side table, when not in use. We would start with breakfast at the table and graduate to the cushioned chairs to read the Sunday paper — elegance and functionality, all in a compact space.

A modernist drop-leaf table is flexible and stylish. With both leaves extended, it serves as a full-size dining table. With one leaf dropped, it’s a small table or desk. You could even drop both leaves and set it against the wall as a console table.

Whether you’re building new or renovating an existing house, storage in a compact home is a high design priority. A cluttered home is neither comfortable nor inviting. We must have space for storing our belongings, and in a compact home the storage solutions often must be clever. The designer must look at every inch of space within the home, from the roof down to the foundation, with an eye toward creating accessible, useful storage.

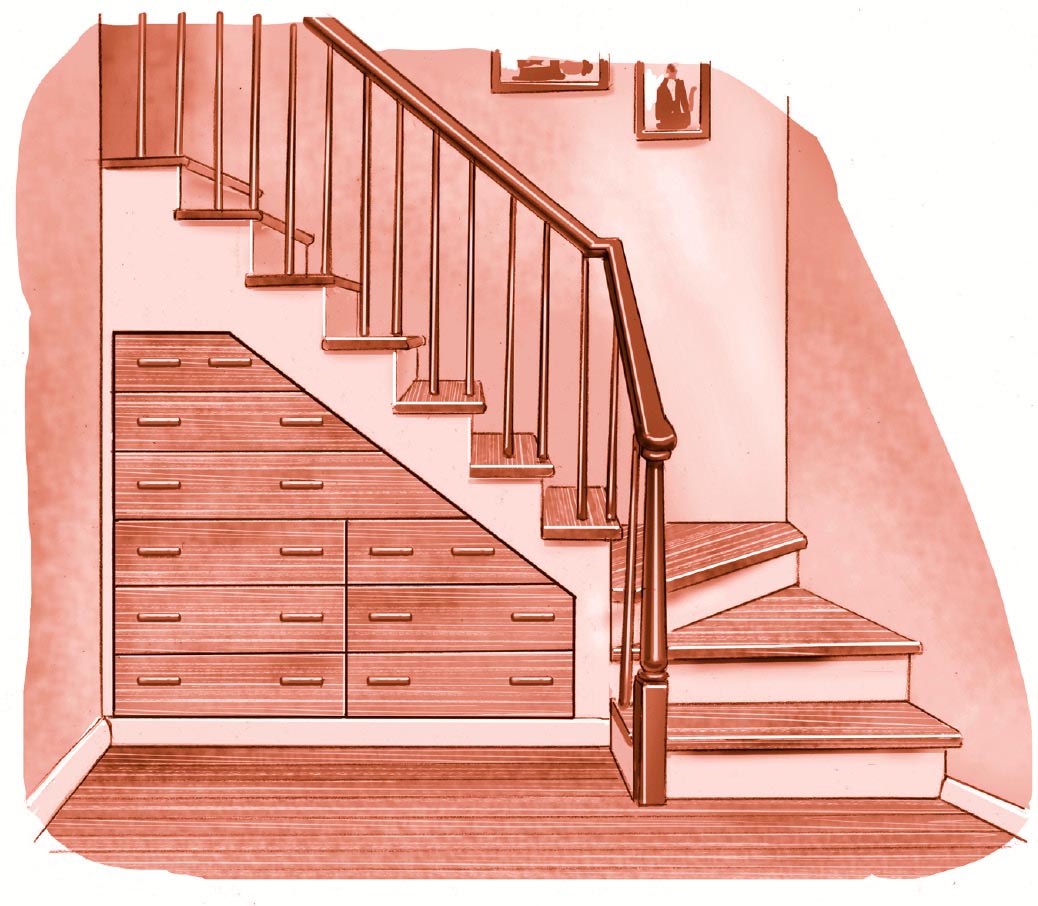

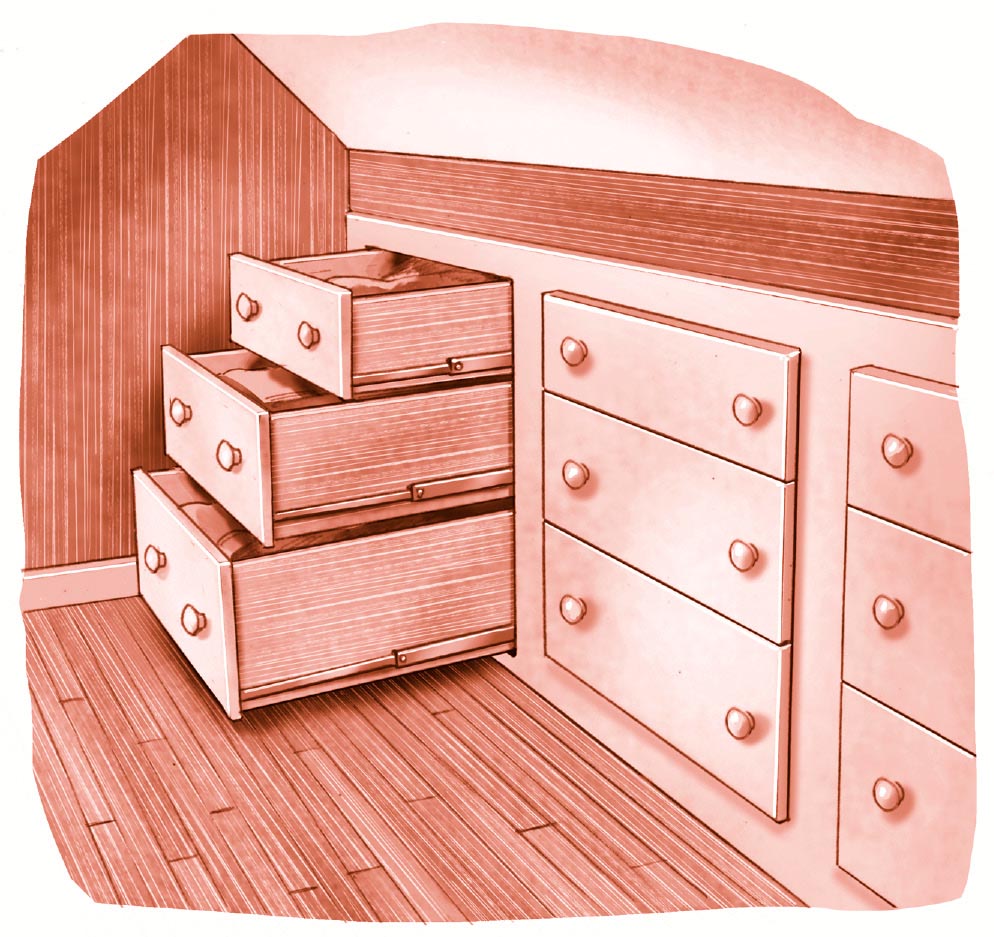

Here is where built-ins can be useful. A house normally holds a surprising amount of unused space. In a well-designed compact home, that space is put to use for storage. The space under a stairwell can become a closet and/or an array of drawers or shelves. In bungalows and cottages, where a low roofline creates sloping ceilings on the second floor, the eaves space — between the outer wall of the second-floor rooms and the exterior wall of the building — can house drawers or cabinets. In any room, for that matter, built-in drawers, cabinets, or shelves are excellent ways to increase storage; narrow shelves can even be seated between studs, which gains a bit of storage space without subtracting it from the footprint of the room. A bedroom built-in storage unit might combine features, with drawers near floor level, a clothes-hanging rod at eye level, and a storage locker above, extending right up to the ceiling.

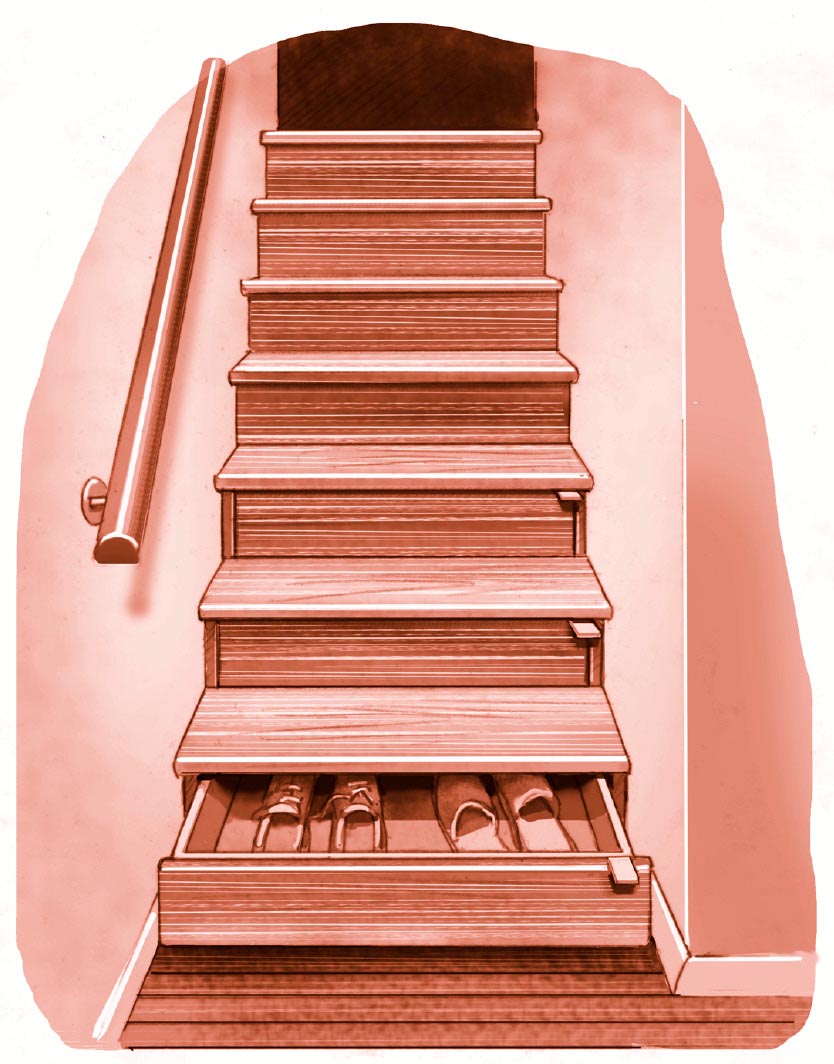

A clever carpenter can reconfigure the underside of each stair step to be a sliding drawer, with a small tab pull on one side. The drawers will be relatively shallow, but there will be a whole staircase of them!

Another way to utilize the underside of stairs for storage is to build cabinets below, whether open or with doors. These cabinets will be deep and irregularly shaped; they can add a funky modern vibe to any living space.

Pull-out drawers fit prettily beneath a staircase, with angled edges to parallel the rise of the steps. The Shakers would approve of the economy and utilization of otherwise wasted space.

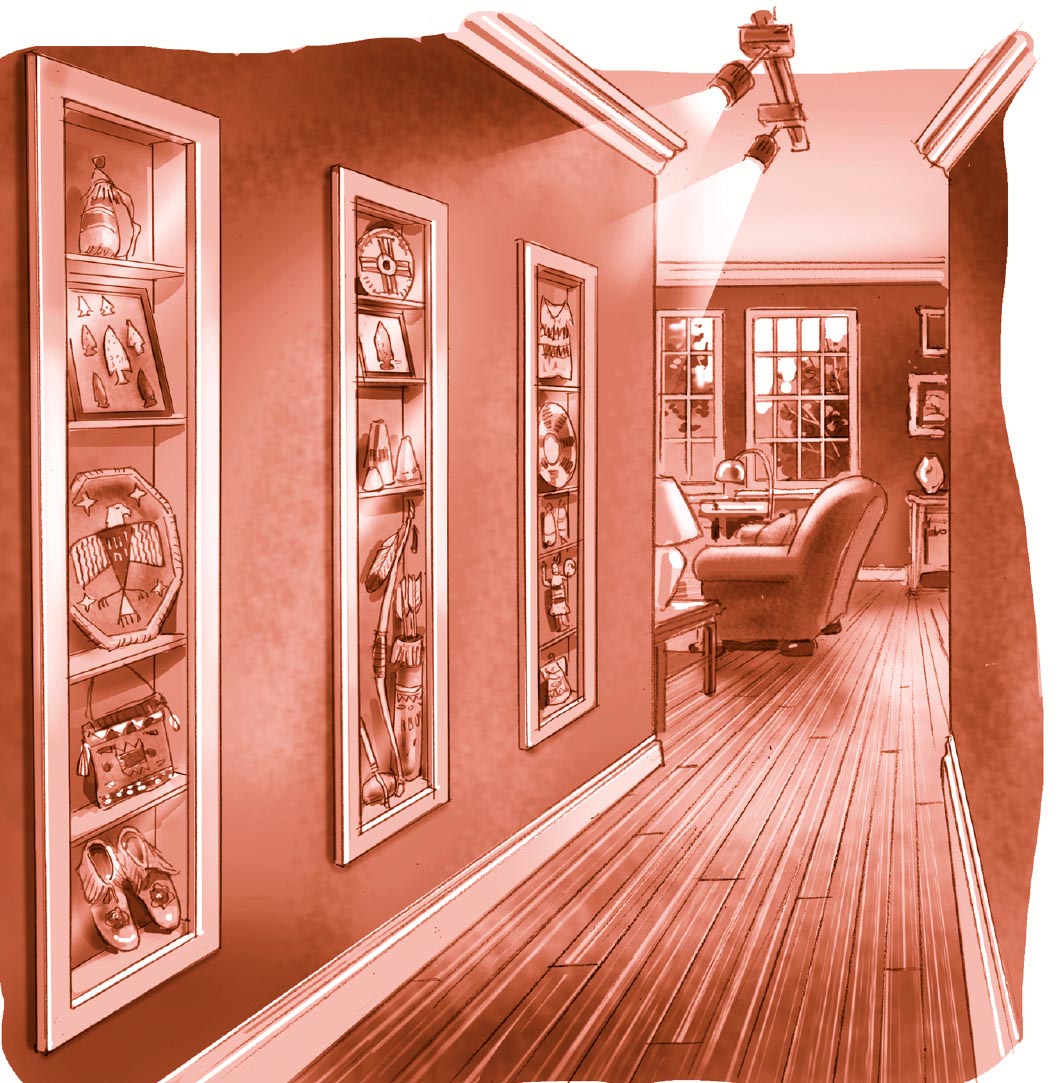

Between-stud shelving is also a good option for storing decorative items in a hallway. If you plan for the cabinets during the construction of your home, you can even arrange to have them wired with interior lighting, to lend a museum-like ambience to their contents.

The shallow, narrow cabinets that can be built between studs, recessed into the wall, make excellent pantry storage in a compact kitchen.

Speaking of cabinets extending up to the ceiling, in traditional kitchen design the cabinets usually do not extend any higher than the average cook can reach, leaving a wide gap between the top of the cabinets and the ceiling. That wasted space can be reclaimed easily by designing cabinets that extend all the way up to the ceiling, or by installing a custom-built set of storage cabinets above the regular kitchen cabinets. Use this upper-level space to contain the tools, serving ware, utensils, and other kitchen gear that you don’t use very often. With a step stool stored nearby, you’ll have ready access to those items whenever you need them, and by utilizing this normally forgotten space you can increase your kitchen storage by about 20 percent.

You can increase bedroom storage similarly by installing cabinets or drawers beneath bed frames. For most people this space is simply a staging ground for dust bunnies, but it’s ideal for storing out-of-season clothing and extra linens. Finished wood drawers are handsome, but a few plastic storage tubs work just as well. I use under-bed storage tubs to store extra sheets and blankets. And at the head of the bed, consider installing a shelf for books, a reading lamp, a clock, your cell phone, and whatever else you like to keep at your bedside (see Murphy-Style Beds). In fact, you could fashion an entire bookshelf headboard, a unique and useful addition to your bedroom decor.

A window seat is an old idea that warrants reviving. Set beneath a wide, often decorative window, with a cushion on its surface, a window seat usually looks quite elegant. And with drawers or a cabinet fitted beneath it, it’s useful storage, too. It’s an ideal spot to sit and read, and it’s also an excellent place to store seasonal bedding, toys, and games.

Of course, the traditional storage space — the closet — remains a fixture for the compact home. If you’re renovating an existing older home, such as a condominium in an older Victorian house, you may find that the closets are tiny, if, indeed, there are closets at all! In these cases especially, organization is key. In recent years closet organization has become an art and a science, and a profitable business for many. A number of companies now offer excellent closet organization tools and design services, but you can plan and install your own closet organization system for a fraction of the cost. To begin, consider what you’ll be storing in the closet and how it can best be assigned to use all the space, from floor to ceiling. Then consider ergonomics. Using every inch of closet space for storage is not very helpful if you can’t identify or access your things when you want them. For myself, I tend to use shelving that has built-in clothes-hanging rails and a lot of clear plastic storage tubs. You may prefer a wall of shoe racks and shelves with woven cotton baskets; a child may do best with a low rack of clothes-hanging hooks and deep open shelves, with the higher spaces saved for clothes to grow into or extra bedding. The point is to design the closet for the user. If your inclinations or needs change over time, well, reorganizing the closet is always an interesting endeavor — and just one more opportunity to purge the excess and simplify your life.

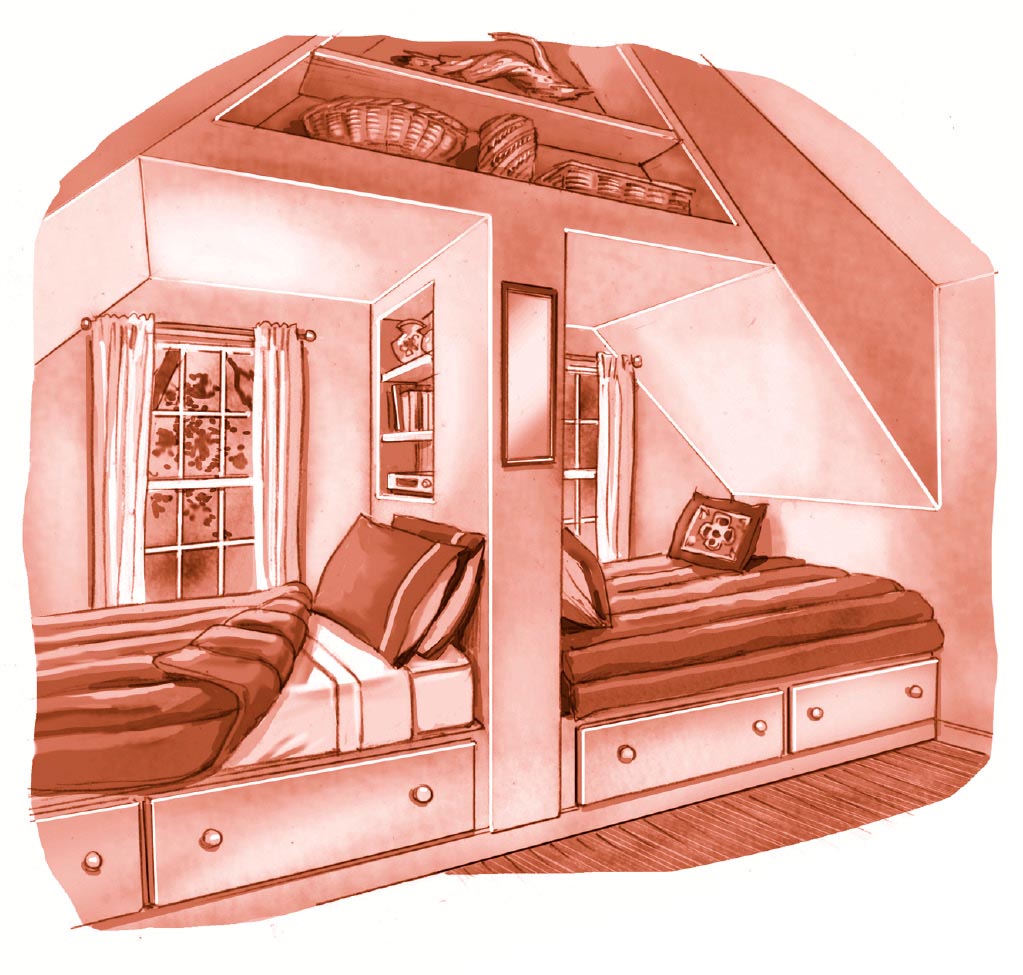

Many small homes, and especially Capes and bungalows, have slanted ceilings in second-floor bedrooms, due to the pitch of a low-slung roof. Built-in drawers, extending into the under-eaves space, are a traditional way to utilize the otherwise wasted under-eaves space.

A bathroom with a sloping ceiling offers an opportunity for built-in storage, and with a skylight set above, it becomes an ideal greenhouse spot, flooding the bathroom with natural light while maintaining privacy from neighbors. If the skylight is operable — that is, it can be opened — it will aid in ventilation as well.

Another clever use of the under-eaves space is built-in bunks, with between-stud recessed shelving at the head of the bed and under-bed drawers. This is a pretty little arrangement for a child’s room or a guest room, with the bunk nooks offering a feeling of coziness and privacy.

An elegant, interesting home makes the best use of its space while also offering private nooks for reading, relaxing, or just getting away from the chaos of family. A window seat is just such a getaway, and because it makes good use of otherwise wasted space, it’s an ideal element of a compact home design.

One way to use small closets efficiently is to think seasonally. I have some very heavy winter clothing that I wear when I plow my driveway, snowshoe, or cross-country ski. Where I live this clothing is only necessary from mid-December through mid-March each year. For the other nine months of the year, I need to store this gear. Here is where clear storage tubs come in handy. I fold up and store this deep-winter clothing and equipment in tubs in the back of a closet, and I exchange them for tubs holding shorts and bathing suits when the snow begins to fall. Plastic tubs are pretty low-tech and not for the chic at heart, but they do work well. You also could use something as simple as zippered plastic clothing bags or as fancy as cedar closets.

The same idea holds true for all other seasonal items. Storing out-of-season gear, from clothes to outdoor furniture, lawn mowers, snowblowers, and so on, not only saves space but protects those items (provided you store them correctly) from the weather, insects and mice, and other factors encouraged by neglect.

Like the window seat, the pocket door is an architectural element you don’t see much anymore. In early American architecture it was traditionally used between the parlor and the dining room, where it could be opened or closed depending on the needs of the family. After a good meal the family and guests could retire to the parlor for coffee, brandy, or dessert and close the pocket doors to the dining room to hide the mess. (In more aristocratic households, this is when the servants would come in to clean up.)

Because pocket doors and other types of sliding doors don’t have a swing radius, they take up little space, which makes them ideal for compact houses. In fact, you’ll see them in use in many of the designs in this book. A sliding door is excellent between children’s bedrooms. It can be opened on a rainy day to turn small bedrooms into a large playroom. And it can add to the magic of pretend play, as it can be the curtain of a star-studded theatrical thriller or the Black Gate of Mordor.

One traditional way to extend a home’s living space is to add a deck, porch, or patio. With the addition of a range of amenities — a table and chairs, lounge furniture, a bar, a grill, an outdoor kitchen, a pizza oven, a fire pit, a fireplace — these outdoor spaces beckon inhabitants outside to enjoy the open air. They make a home seem more welcoming, more spacious, and better integrated with the outdoor environment. (Pergolas and gazebos can serve in the same way.)

Decks, porches, and patios can be part of a budgeted building program. They can be built to function as an outdoor living space at the onset and, when finances allow, later enclosed, insulated, and wired for electricity. In the same way, an open porch can be destined for conversion to a sunporch or screened porch when time and finances allow. Of course, if this kind of expansion is part of the overall house design, then consideration for its final use should be given from the very beginning. For example, if you intend to eventually enclose a patio, you may want to lay the foundation for the eventual enclosure at the outset, so you don’t have to dig up the patio later to put down a foundation with adequate structural support. You may want to embed radiant-heat tubing in the patio floor, with the intent to connect the tubing to the house’s heating system when the patio is enclosed. If you intend to someday enclose a deck, you’ll want to consider how its roofline will intersect with the roofline of the existing house. If you intend to someday enclose a porch, insulating the porch floor will be much easier during construction, rather than retrofitting the floor with insulation.

A sunporch doubles as an elegant open-to-the-outdoors living space and an energy-saving design component. Usually a sunporch is an enclosed, insulated porch with large arrays of windows or glass panels and some type of masonry floor. When oriented correctly — generally to the south of the home — it can function as a passive solar collector, with the masonry floor absorbing the warmth of the sun during the day and radiating that heat back into the home during the night. (A thermostatically controlled duct blower can assist with moving warm air from the porch into the rest of the house.) Of course, provisions must be made for adequate ventilation during the warmer months of the year; operable windows and skylights can help with this, as can deciduous trees, whose leaves block the summer sunlight. Curtains made from greenhouse-grade shade fabrics can also help. These fabrics are usually made from knitted polypropylene yarn and are graded by the amount of shade they provide, from 20 to 80 percent. They are relatively inexpensive, and since they are porous they allow air to circulate and don’t block the ventilation. I made a roll-up shade from an 80 percent shade fabric for one end of my own sunroom, using the hardware from an old bamboo roll-up shade. I mounted it above the windows on the west end of my sunroom, and I roll it down when the afternoon sun is a bit too strong.

When a compact home is paired with a compact yard, you’ll want to make the most of your outdoor space to optimize its functionality. The size of the yard determines how much space you can allot to any particular landscape design item. Big decks mean less space for trees and shrubs. This is not necessarily bad; a big deck offers more outdoor living space and reduces the yard area that needs to be tended. Again ergonomics become important. If you are not a gardener and like to entertain outdoors in the summer, a big deck is a good idea for you. On the other hand, if you love to garden and your kids like playing outside, then you’ll want to maximize the open space in your yard. Good landscape design, like all home design, is driven by the intended use of the space. Figure out how you’ll use the yard, and you’ll be well on your way toward designing it.

If you live in a suburban setting, privacy may be an issue for your outdoor living spaces. Again, figure out how you’ll use the yard, and then examine how the landscaping offers privacy for each of the spaces you’ll use. Where privacy is lacking, you can add living fences (shrubs and the like), wood or PVC fencing, screens, or roll-down blinds. Such features not only enhance the functionality of the outdoor space but also add equity to the property.