Chapter 4

Retrofits: Finding and Renovating a Compact House

No discussion of compact houses would be complete without a look at the wide range already in existence.

Bungalows, Cape Cod cottages, ranch houses, and other types of small homes that predominated housing development in the twentieth century can be found in ready supply across the country. And these houses are ripe for retrofits, with solid bones but infrastructure, appliances, technology, and decor in need of updating.

Renovating a compact house, rather than building a new one, has great appeal for many people of different backgrounds, lifestyles, and incomes. A renovation can be less expensive overall, or at least in the long term, as you can live in a home while you’re renovating it. It also allows you to use sweat equity to your advantage. If you’re working with a historic home, you may be eligible for special low-cost mortgages, grants, and home-improvement loans to restore the house. And a renovation has a smaller carbon footprint than a new house, simply because it doesn’t require as much in the way of new materials.

How we organize and assign interior space in our homes has changed over time to reflect current lifestyles and technologies. Formal living rooms are disappearing in favor of family rooms. Areas that have limited function, such as hallways, are vanishing. Kitchens are larger and offer seating for noncooking guests. Houses have more bathrooms, and master baths are not uncommon. You won’t find many of these features in older homes, but there’s no reason to assume that they can’t have them. When you’re thinking about renovating a particular house, you have to think about how the space was intended to function, how it does function, how you want it to function, and what is possible, in terms of redesigning the interior spaces to make the home function as you’d like. Design, structure, ergonomics, style, energy efficiency, sustainability, and technology all play a role here.

Good design reflects contemporary ideas. That is, good design is current in its awareness of materials, techniques, technologies, and notions of how we use our living spaces. And while good design is independent of style — it can be neo-Bauhaus, Federalist, midcentury-modern chic, or what have you — it is highly personal and driven by the use patterns of the individual household. Instead of any preconceived ideas of what constitutes a good home today, good design approaches the concept of “home” afresh each time. And that allows you to look at an existing house with fresh eyes and decide for yourself whether it has the potential to be a comfortable, beautiful, easy-to-live-in home for you.

Advantages of Retrofitting versus Building New

- The utilities are already on-site: water, sewer, electric, gas, Internet, cable TV, and so on. This saves both time and money.

- Most existing houses have mature landscaping and established lawns. With new construction, you’ll need professional landscaping, which can be expensive and takes a long time to come into its own. A good shade tree takes from 20 to 30 years or more to mature to a useful size.

- Often you can live in a house while it’s being renovated. (For this to work you have to be able to tolerate some degree of construction chaos for an extended period of time.)

- Renovating a house is usually less expensive than building a new house, especially if you’re at all handy and can do some of the work yourself. The more work you can do yourself (sweat equity), the less it will cost for the same square footage compared with new construction.

- If character is your thing, older houses have it. Whether it’s the warm patina of age or the discriminating details of a certain period, older houses have earned their character in a way new houses are hard put to match. It’s really hard to fake the aging process.

- From an environmental standpoint, renovating an existing house makes a lot of sense. It requires less in the way of new materials and allows you to recycle a lot of the existing materials and infrastructure.

Restoration versus Remodeling versus Repurposing

In just about any real estate market today, you can find housing in a range of styles, square footages, and ages. Of course, they’re also in various states of disrepair and outdatedness. But if you’re up for a renovation project, you can get a great deal on what can become the home of your dreams. Whatever the type of housing you’re looking at, there are three possibilities for renovation: restoration, remodeling, and repurposing.

Dollar Houses

Many communities — particularly in declining urban areas — have programs to help homeowners turn abandoned or deteriorated houses back into viable homes. These houses, sometimes called “dollar houses,” are often city owned and are offered to buyers for a nominal fee, with the agreement that the buyer will refurbish the house and bring it up to current building codes. The programs usually require that the buyer place money in escrow at the time of purchase to cover the costs of the renovation, and they may impose a time limit for the period of renovation. They may also require that the owner occupy the home for a certain number of years after the renovation. All these requirements notwithstanding, many communities with dollar-house programs also offer grants and low-interest loans to help owners renovate these houses.

Restoration

Restoration entails renovation with a sense of historical architectural correctness. The degree of correctness varies depending on the homeowner and community. While there are purists, insisting upon absolute historical correctness can lead to uncomfortable houses. A historically correct 1940s kitchen, for example, simply couldn’t meet modern needs. Intelligent restoration celebrates what was good about the past and updates or disregards what was not good. The eclecticism of elements in the marriage of old and new gives the homeowner the best of both worlds.

As a general rule of thumb, restorers keep the exterior of a home historically correct and upgrade interior utilities and appliances to current standards. In particular, they’ll focus on remodeling bathrooms and kitchens and, since older homes are notoriously short on storage space, adding more closets and shelving. Depending on how close they want to stick to the historical standard, restorers may consider upgrades as radical as removing walls to open up interior spaces, adding windows to bring more natural light into the home, or putting a swimming pool in the backyard.

Throughout America many towns and cities have designated historical districts, where homes and other buildings are usually all of an equal age and stature. Any renovations in such a district are usually required to adhere to a certain standard of historical correctness, as decided by a historical review board, though the regulations vary in their strictness. Those that lean toward being very strict may dictate the building materials residents can use and even the colors they can paint their exterior trim. Some people think of historical review boards as an infringement on their individual liberties and freedoms; others view them as a guide to correct restoration. However you may feel about the review boards, buying a home in the neighborhoods they supervise can be a profitable investment; homes in historical districts can sell for 10 to 20 percent more than homes just outside those districts.

Many historical districts have established preservation associations that offer help and advice about construction, reconstruction, and zoning within the district and also act as a social group for like-minded homeowners. Some even hold classes dealing with renovation issues of plumbing, carpentry, electrical wiring, and so on.

Remodeling

Remodeling is similar to restoration in some ways but is not encumbered by the constraints of historical correctness. You have far more design freedom in remodeling a house. You can use contemporary materials without the need to disguise them as historically correct materials. You will not be required to have utilities buried underground or enter the home from the rear of the property, as is required in some historical districts, and you’ll be free to add solar panels or other outdoor equipment wherever it is most efficient. And you can add on to your home in whatever way you wish, building out porches or decks or adding rooms.

Repurposing

As the name implies, repurposing means redesigning an existing structure for a new purpose. You might, for example, purchase a shop, church, or other commercial space, and repurpose it as a living space. This concept has become especially popular in urban areas, where old factories or office buildings, which generally encompass lots of open space, are often redesigned as loft apartments.

Some repurposing involves converting a space into two or more units, with one devoted to living and the other a storefront, workshop, or studio. This kind of repurposed housing is popular with artists, architects, craftsmen, and tradesmen who want to live near their work area. In an urban area, a repurposed multistory building usually designates the first floor as commercial space and gives over the upper floors to living space. Some such buildings even incorporate roof decks with hot tubs and potted gardens. This arrangement works well. The commercial space is easily accessible at ground level. The living space is above this with the bedrooms on the higher floors, where the air is fresher. This removes the living space from the commotion of the street level. And rooftop gardens create an isolated oasis even in the midst of a city.

Preservation Resources

If you’re interested in home restoration and preservation, look up the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP). This organization is dedicated to quality restoration and preservation of America’s architectural treasures. It supports not just early colonial architecture but a cross-section of historically important structures from colonial times through current times. The NTHP also supports organizations that endeavor to preserve historical neighborhoods or communities.

Before You Begin

Before you begin house hunting, make a list of what you want from a house, distinguishing between needs and wants. Needs are nonnegotiables; for example, you might need three bedrooms, more than one bathroom, and a roomy kitchen. Wants are more flexible; you might like to have a master bathroom, or you might prefer to have four bedrooms, so that you can have a separate guest room. But know what you want and need before you start looking at houses. That way you will not get caught up in the excitement of a new and interesting property. Remember that it is the job of a good real estate agent to get you excited about whichever property you’re looking at.

If you’re planning on doing the renovation work yourself, you’ll also want to have some idea of the limits of your skills. Then you can determine the scale of renovation you’re interested in and capable of tackling.

If you’re planning to take out a loan to purchase the home, you might also consider getting preapproval from a bank for a mortgage. Then you’ll know your price range. Keep in mind that you’re planning a renovation here, and you need to take into account the cost of the renovation work. You may be able to roll the renovation costs into your mortgage, especially if you’re planning on hiring contractors who can give you written estimates; talk to a bank officer about this possibility. Regardless, you’ll need to estimate the cost of renovation and add it to the cost of the home before you can ascertain the true and full cost of your home renovation.

House Hunting

So you’re thinking about buying and renovating a house. This poses an important question: what are the criteria to use when evaluating a house? In a lot of cases, comparing houses is like comparing apples to oranges. This house has a porch, and that one a garage. This one is 1,400 square feet, and that one 900. This one has a nicely landscaped yard; that one has a beautifully updated bathroom; the other one needs a complete rehabilitation of the kitchen, but it’s a lot cheaper.

To compare houses at the most basic level, it helps to break down the numbers to common values. Let’s examine some of the factors.

Comparing Cost and Value

The first step is to establish the cost and projected value of a property. Start by surveying at least six houses (ten is better) in the same area that are selling within a narrow price range. This seems like a lot of footwork, but after you do it you will have a clearer idea of what you can purchase for your dollar in the area. Remember, all real estate values are local. Always compare properties that are in the same neighborhood or area.

Then chart the houses so you can compare features and how they affect price. Set up a spreadsheet listing the following for each of the properties:

- Price

- Location

- Condition

- Number of rooms

- Number and condition of bathrooms

- Number of bedrooms

- Kitchen (eat-in or not?) and condition of appliances

- Outbuildings (garage, etc.)

- Square footage of living space

- Attic

- Cellar

- Porch, deck, or patio

- Size and condition of yard

- Benefits/drawbacks of location

- Cost per square foot of living space

Now it’s time to evaluate the potential value of each property. There are, of course, intangibles — your emotional reaction to the style and setting of the property, the fact that you know (or loathe) the neighbors, and so on. But for the purposes of comparison, it’s best to stick with financial factors. These figures will work together with the intangibles to determine your decision. You’ll want to know three things:

- The projected highest selling price for the home when renovated

- The cost to bring the house up to that value

- The projected value per square foot of renovated living space

The projected maximum resale value is a parameter for your decision, not an actual limit to your work. It simply tells you the highest value your home can have as a strictly financial asset. And keep in mind that houses do have limits to their value, no matter how much work you put into them. For example, if you’re surveying houses selling for $150,000 to $200,000 in a certain neighborhood, you’ll want to know that even the freshest-looking house in that neighborhood won’t sell for more than $275,000. There are exceptions — such as if a successful high-tech firm moves to town, or gold is discovered underfoot — but generally such limits hold true.

The projected renovation cost is similarly a parameter, not a limit. You may decide to do less or more work to any particular house. This figure is simply an objective guideline for the purpose of comparison.

And now it’s time for that comparison. Add the projected renovation costs (to bring the house up to its maximum value) to the purchase price for each property. Note that figure alongside the projected maximum value. Then compare the figures for all the properties (you can even convert them to ratios if that’s helpful). The results of your comparison should tell you which houses have the most potential value to gain from renovation.

Comparing Sweat Equity Value

If you’re planning on doing some of the renovation work yourself, or building sweat equity, you will want to compare the potential sweat equity value for each property. For the sake of this discussion, let’s say you’ve narrowed down your choices to two houses with the same purchase price and are trying to choose between them. House A needs a new kitchen and bathroom, and House B needs a new driveway. Let’s say the materials you would need for a new kitchen and bathroom in House A would cost about $8,000 total. Adding labor costs, a contractor might give you an estimate of $16,000 for the work. The old driveway of House B needs to be removed, a new base put down, and then the driveway repaved; a contractor might give you an estimate of $15,000 for the work.

If you plan to use contractors for both projects, House B might be a better choice simply due to the fact that the renovation would cost less. But now let’s factor in sweat equity. If you’re handy, you could do the kitchen and bath renovation in House A yourself and cut the cost by half. But if you don’t own excavation equipment, a dump truck, and a paving machine (and who does?), you probably wouldn’t be able to tackle the driveway rehab at House B. Based on these facts, House A seems the better choice.

Comparing Value by Square Footage

Another way to compare houses is to compare the value per square foot at the time of purchase price and at maximum resale value. To calculate these numbers you simply divide first the purchase price and then the maximum resale value by the number of square feet of the house.

You could then calculate the percentage of return per square foot. Let’s say you bought a house at $99 per square foot and sold it for $127 per square foot. That is a difference of $28 dollars per square foot. In a 1,000-square-foot house that you purchase for $100,000, that represents a gain of 28 percent. A large property might return more dollars in equity, but a smaller property might return a much higher percentage of equity. So don’t be seduced by the idea that bigger is always better. Given that the smaller property would take less time to renovate and requires a smaller initial investment, it could actually be the better investment.

Other Considerations of Value

There are a number of factors to take into consideration that go beyond the basic finances of a house:

Your timeline. If your time is unlimited, taking several years to complete a project may not be a problem. Tradesmen choreographed to work in unison can get the job done very quickly. The first way is less expensive and slower; the second, more expensive (but usually quicker).

Your abilities and skills. Redoing a house takes a broad array of skills: carpentry, plumbing, electrical, drywall, painting and trim work — not to mention design skills, record keeping, scheduling, some light bookkeeping, and communicating with subcontractors and building supply stores. You do not have to know everything, but you do need to be willing to learn as you go. This might entail making mistakes that will have to be corrected.

Time available. If you work 50 to 60 hours a week, you may not have the time to undertake a house redo by yourself. And you may have other commitments on your time (friends, family, kids, etc.) as well. These are important concerns and may determine if the project gets finished or not. You don’t want to find that after you have completed the project, no one, not even your kids, is speaking to you.

Your finances. A shoestring project needs a lot of your effort. Having a big budget allows you the luxury of watching someone else do the grunt work. There may be a mix of the two approaches that is right for you.

Your tenaciousness. Many people with the dream of redoing a house run out of steam before they finish. It’s important to schedule in downtime to recharge your batteries. A little downtime is better than burning out.

Your flexibility and willingness to work. How long can you live with the disruption and dirt of working on a property? This boils down to enjoyment or the lack thereof. If you find it personally rewarding to work with your hands, your project might be a labor of love. If you hate that kind of work, it could be a painful experience best left to others. I find saving time at the end of each working day to clean up well makes living with construction more tolerable.

Local building codes and ordinances. These may change from town to town and affect how you rehab a house. People generally do what they can themselves and hire others to do what they can’t. The exception would be where local zoning requirements are involved. Many municipalities require that public gas service, city water service, and electrical breaker panels be installed by licensed tradesmen. Further, many municipalities require that all work done on rental or commercial properties be done by licensed tradesmen.

Building regulations in historical districts. Homes in designated historical districts sometimes have stringent parameters guiding any renovation work. You can check in with the local historical review board or municipal building department to find out about such regulations. (And see page 181 for more on historical districts.)

Renovation: A Case Study

A few years ago I decided it was time to sell my old house and move on to a new project. I was living in a historical district in the inner city of Allentown, Pennsylvania. I had lived there for more than 20 years, and over that time I had, as a contractor, built a number of summer cabins and houses and refurbished a number of older houses, from colonial fieldstone farmhouses to gingerbread Victorians to contemporary condos.

The challenge was, what would I do now? I had always been interested in redoing a 1950s-era house (usually described as midcentury modern) and decided this might be a good time for it.

Finding a House

I started by making a wish list of the features I would like in this house:

Small. I was living in 1,400 square feet at the time, but as an empty nester, smaller seemed better. I thought something in the range of 1,000 square feet would do it.

Two bedrooms plus an office. I wanted a master bedroom, a guest bedroom, and a home office. Though there are various ways to fit a home office into small spaces, this probably meant that I was looking for a three-bedroom home.

One floor. This is an idea I would not have considered ten years ago, but now that I was an aging pre–baby boomer, it seemed a legitimate concern.

Good bones. I was looking for a house that had “good bones” — that is, it was structurally sound — but needed a total cosmetic redo and updating. It takes a little practice to look beyond the cosmetic to the structure underneath, but it’s important. Without major demolition and rebuilding, a house with “bad bones” can never be brought up to the standard of one with a good basic structure.

Three-car garage. I was looking for a three-car garage: two for cars and one for my travel trailer and camping gear. When I began my search this seemed like an absurd possibility. Small midcentury houses have, at best, a one-car garage. (But I got lucky.)

Small yard. I wanted a yard, but not a large one. The idea of spending a lot of time cutting grass doesn’t appeal to me — been there, done that. I also wanted a space for a garden. Around a half acre seemed ideal for my needs.

Good resale value. I wanted a house that would maintain its value. I know that a small house, in good condition, will always have appeal as a starter house. A young couple just starting out will naturally mature into several kids, and that’s when good schools become an issue. So, though I don’t myself have kids at home, I narrowed my search region to one of the best school districts in my area.

Fixer-upper. Choosing a small house that needed work would allow me to buy without a mortgage. With no mortgage, and fixing it up out of pocket, I would have a good degree of financial flexibility.

That Old House Character

It is sometimes impossible to duplicate the details and materials found in older houses. I once owned a bungalow-style house that used chestnut trim throughout, on window and door trim, baseboards, the paneling in the dining room, and the wainscoting in the kitchen. The straight-grained chestnut wood had aged over the years to a rich, dark color that imparted a warm, homey feel to the house. I loved it. I would wholeheartedly recommend chestnut trim in just about any house. But since the blight of the early part of the last century, chestnut wood has not been available. Unless you buy it from a salvage yard (and it’s rare to find it there), the only way to get that chestnut character in a house is to buy a period house. Staining new woodwork simply does not yield the natural depth of character that real chestnut does over time.

I looked for a little more than three months. I finally found a small ranch house, just under 1,000 square feet. It was built in 1949, had been purchased by its current owner in the mid-1960s, and was in dire need of work. It sat on a half-acre-plus lot with some nice mature shade trees and room for a garden plot. There was a back porch and a three-car garage. One bay of the garage had a 12-foot-high door and could house a 30-foot trailer; another bay had an auto-service pit and a furnace and could be heated whenever necessary. Inside the house, the bathroom had not been updated since the house was built and had serious rot issues around the tub. The kitchen had been redone in the 1960s and showed it. The interior of the house was covered with dark, cheap, early-1960s plastic-coated paneling. The floors were covered with orange wall-to-wall carpeting with lots of stains. But under the carpeting I found red oak flooring. The carpet pads had fused to the floor finish, but I knew that any residue could be sanded off fairly easily and the floors would refinish beautifully. The windows were original and leaked cold air badly; they’d have to be replaced with something more efficient.

The foundation was poured concrete, with a large I beam running the length of the house. There was no cracking in the foundation and no evidence of flooding in the cellar. The heating system was an oil-fired hot-water baseboard system, about 15 years old. The house had large eave overhangs that would shade the interior in the summer while allowing the sun in during the winter. The water was public, the sewage private (though I’m told public sewage is on its way). The septic system and drain field (which was all but plugged with solids) dated from the original construction of the house and would need to be replaced.

Making a Renovation Plan

When I first saw the home, I had been assured that a lot of demolition work would be necessary to repair the walls and structure. I measured the house carefully and began to redesign it on paper. I would carry pencil and sketchbook around with me and make notes whenever ideas struck me. But you never know what you’ll find when you begin a renovation project, and I got lucky. When I removed the old paneling, I found underneath it thick (five-eighths-inch) drywall with a finish coat of plaster, all intact. There were virtually no cracks in any of the walls. They were in great shape.

The demolition process provided an insight into the quality the original builder had put into the house. In the postwar 1950s, new housing generally was built fast and cheap to meet the demands of a vigorous market and the limited funds of young families. Many new houses in that era were purchased through the GI Bill, with no money down and very reasonable interest rates. Many builders sacrificed quality to produce the largest houses for the dollar. But the builder of this house was producing quality construction when it was not the popular trend.

I decided to rethink the reconstruction with an eye to keeping as much of the original interior as was practical. I wanted to make a point of respecting the quality work of the original builder, while obliterating all the bad remodeling that had been done in the late 1960s. My new plan was to maximize the living space without changing the footprint of the house. I had four primary goals:

Open up the interior. This home was a typical 1950s ranch: a number of small rooms interconnected with doors. I wanted to open the space up and make it more accessible.

Add closet space. Like most houses built in this era, the house seriously lacked closet space.

Demolish the bathroom and rebuild it from the studs out. This was probably the worst room of the house. A half century of mold and rot had destroyed it.

Redesign and rebuild the kitchen. The kitchen was essentially a Pullman layout: long and narrow with a central walkway. I liked the layout, but the fixtures and appliances represented the worst of past remodeling. I planned to rip out most of it and install new floor and wall tile, cabinetry, appliances, plumbing, insulation, wiring, and so on.

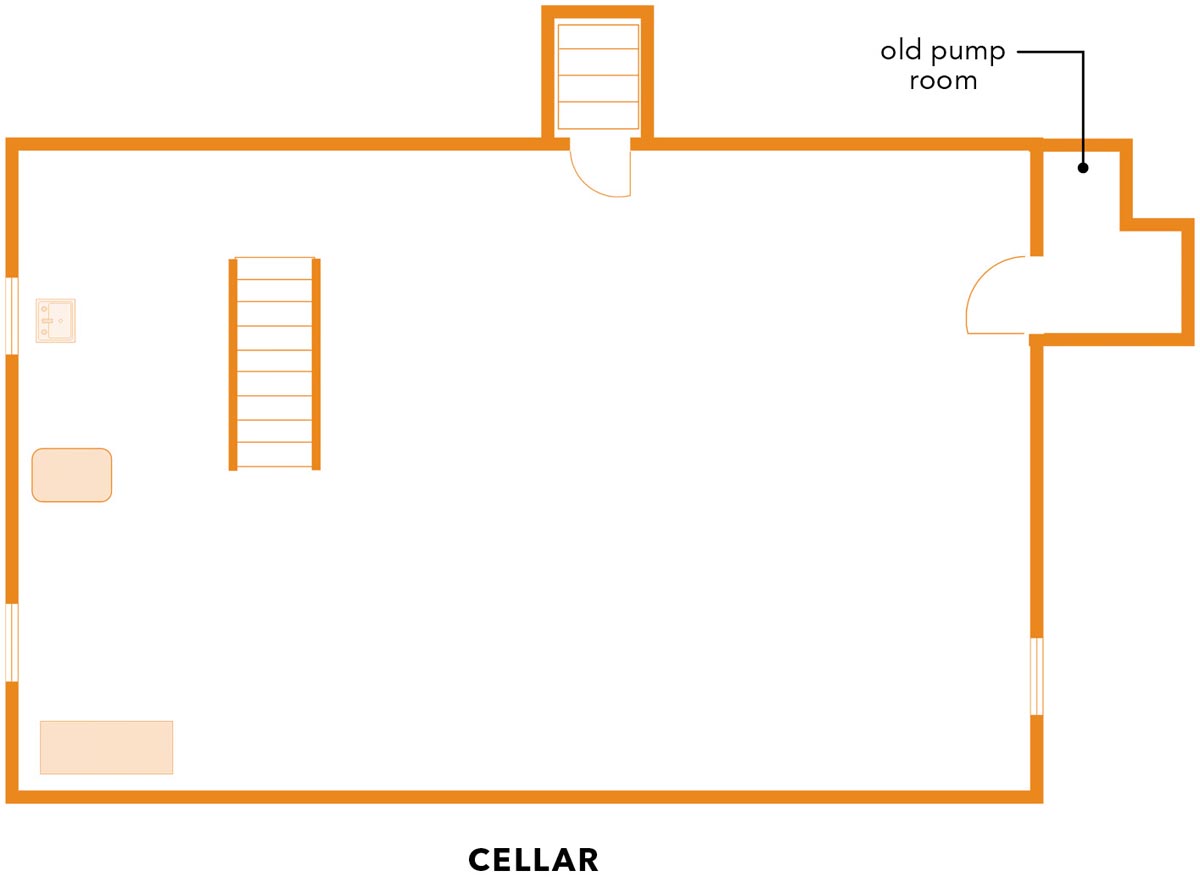

With the demolition and rebuilding work greatly reduced from what I had expected, I had extra funds, which I directed toward extending the living space by enclosing the porch and finishing the cellar.

The southeast-facing porch ran the length of the house. I decided to enclose the space and convert it to a sunroom, adding insulation, baseboard heating, Berber carpeting, energy-efficient windows, a combination wood-and-coal-burning stove, and a powder room with a toilet and sink. The extra heat from the stove and the solar gain from the windows can be directed into the house to supplement the winter heating. It has since become my favorite space in the house. I start my day there each morning with coffee and end it there by the fire on cold winter nights.

The cellar was a blank slate, housing only the furnace, fuel oil tank, and laundry sink at one end and an unused pump room at the other. The bulk of my uncommitted funds would go here. My plans for this space included the following:

- A family room with a wet bar with a sink, small refrigerator, microwave, and two-burner induction cooktop; a woodstove and baseboard heat; and Berber carpeting; along with a full bathroom with a large spa tub and a two-person sauna

- General storage space

- A pantry for the storage of canned goods

- A washer and dryer near the laundry sink

- An area devoted to a fly-tying bench (I love to fly-fish)

- A combination wine cellar and root cellar in the former pump room (a cast-concrete-walled room that was completely underground)

The original house had 912 square feet of living space. With my renovations, I added 708 square feet of living space in the cellar. The sunporch added another 323 square feet. With these modifications, 912 square feet became 1,943 square feet without expanding beyond the existing footprint of the house.

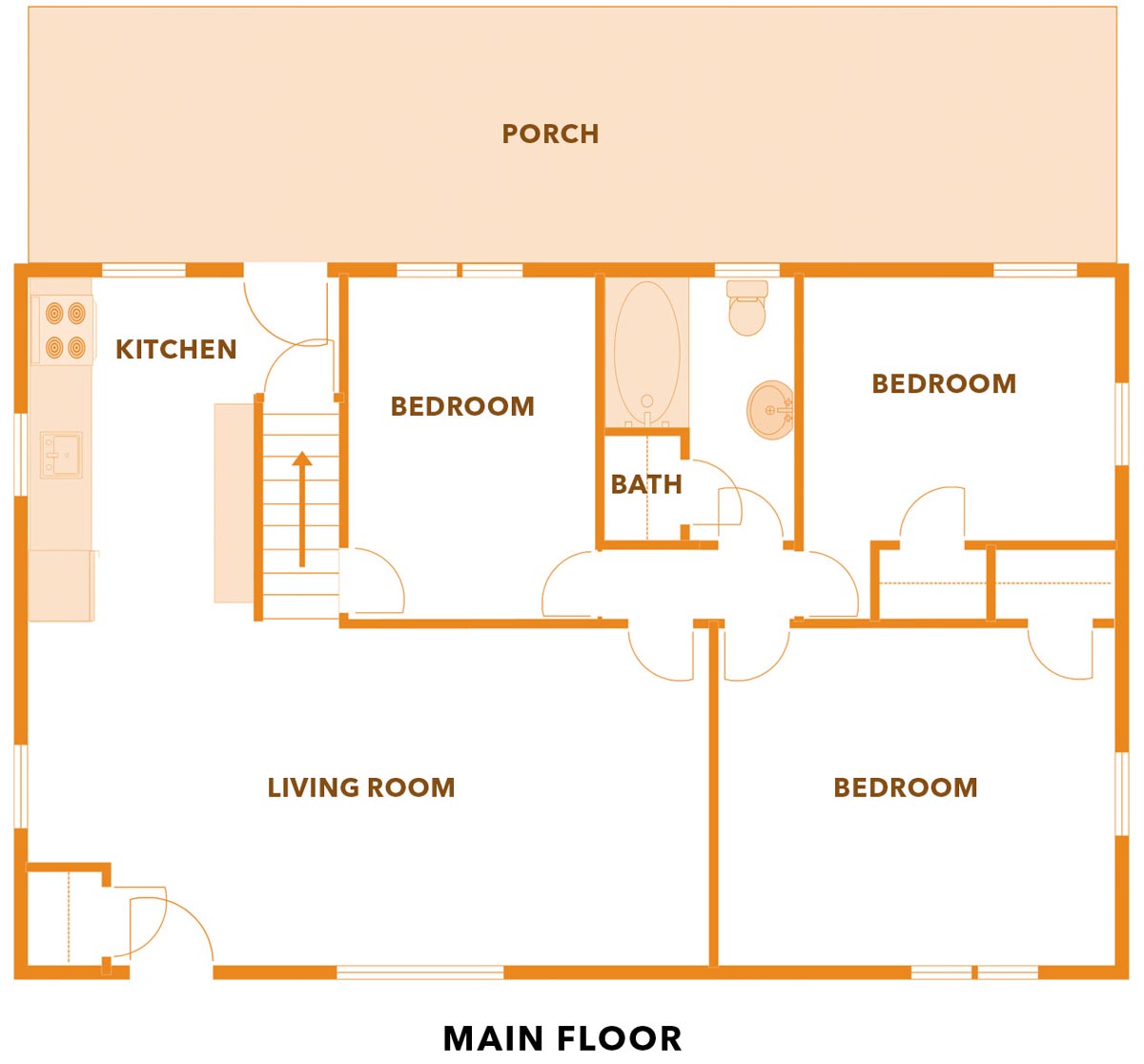

On the following pages you’ll find “before” and “after” floor plans for the little ranch house. Following them are “before” and “after” plans for some other compact houses I’ve renovated.

Converting Cellars to Living Space

One common way to increase the living space in a compact home is by repurposing the cellar. A modern finished cellar can house an in-law apartment, a family/game room, a studio or workshop, or what have you. Whatever the choice, you’ll likely want to install a bathroom.

In the past, one common problem with cellar bathrooms was getting the wastewater into the sewer system. Thankfully, great advances have been made in “flush-up” systems. Modern flush-up systems consist of a small plastic chamber installed below the cellar floor that contains a pump and operating system that pump bathroom waste into the sewer system. These systems are equipped with ventilation equipment, so no smells enter the living space. Many also function as sump pumps; they are fitted with a valve that allows any groundwater that rises up or seeps into the cellar to drain into the unit and be pumped into the sewer system.

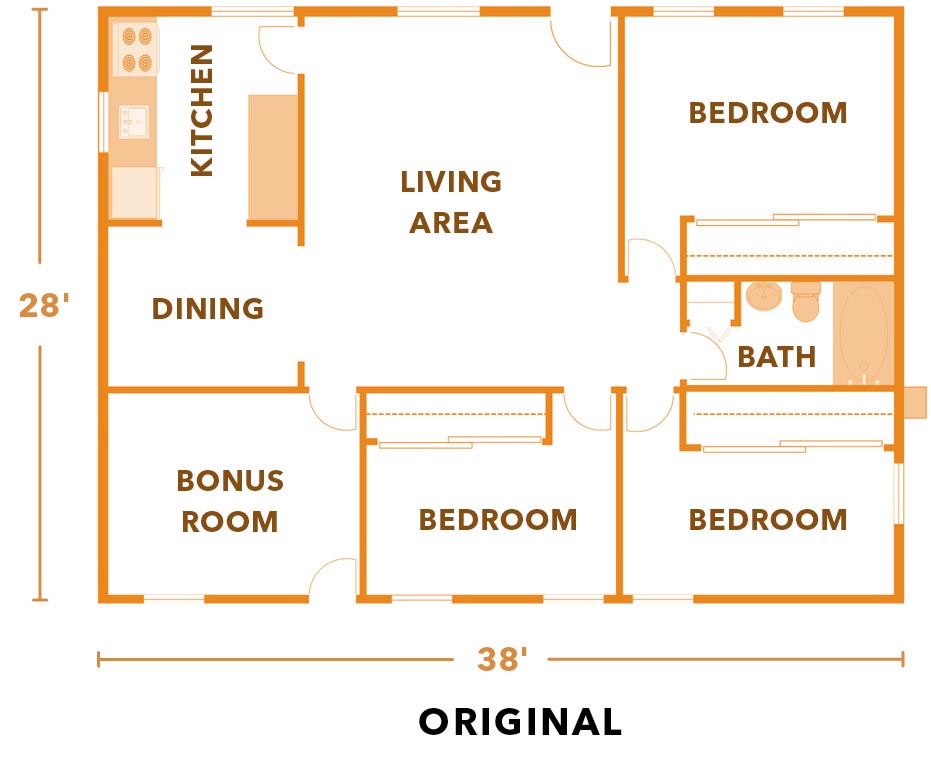

Original Floor Plan

The ranch home was structurally sound but sorely in need of stylistic, mechanical, and functional updates. The kitchen was outdated and inefficient, while the bathroom had lost the battle against rot and mold. Closet space was inadequate, and the unfinished basement had long been neglected.

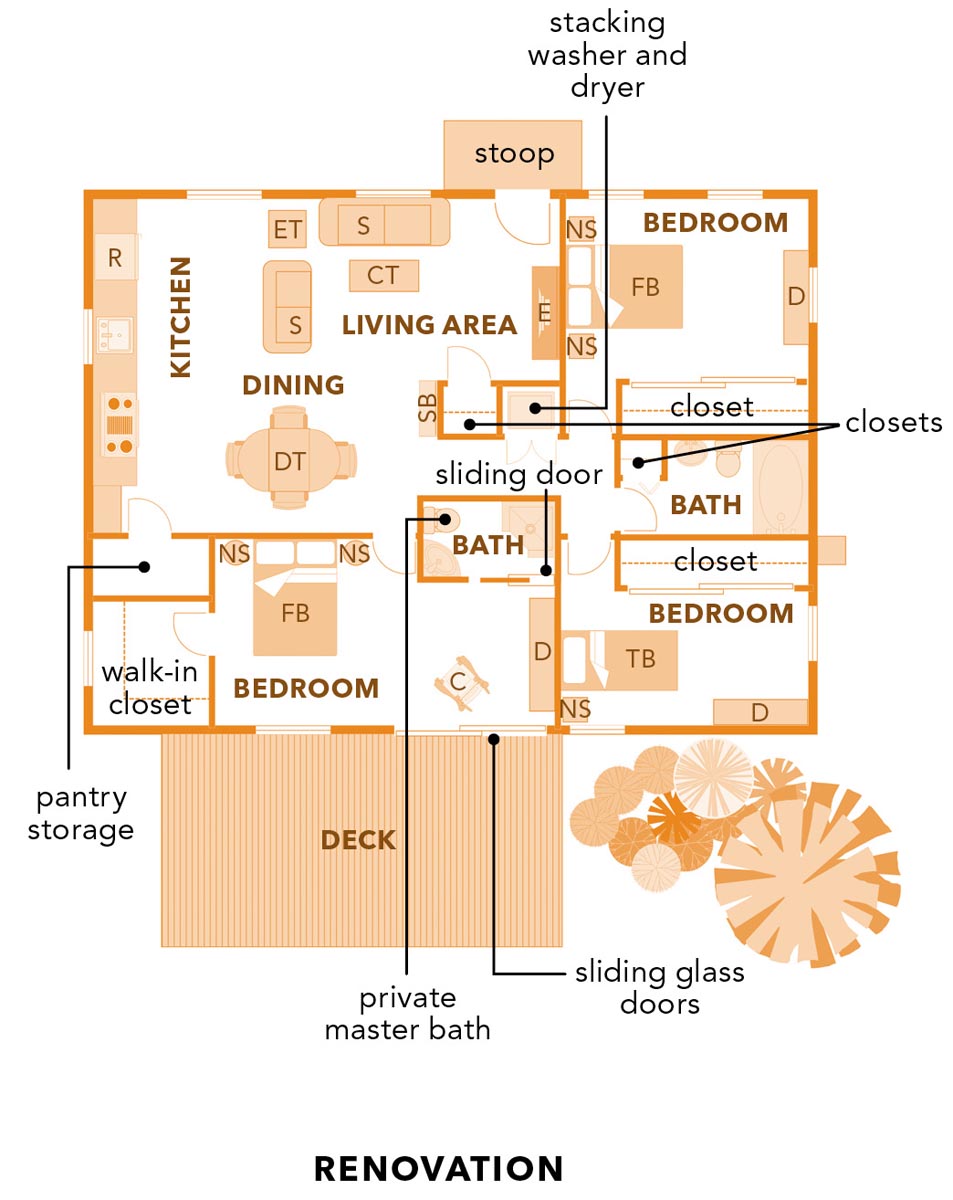

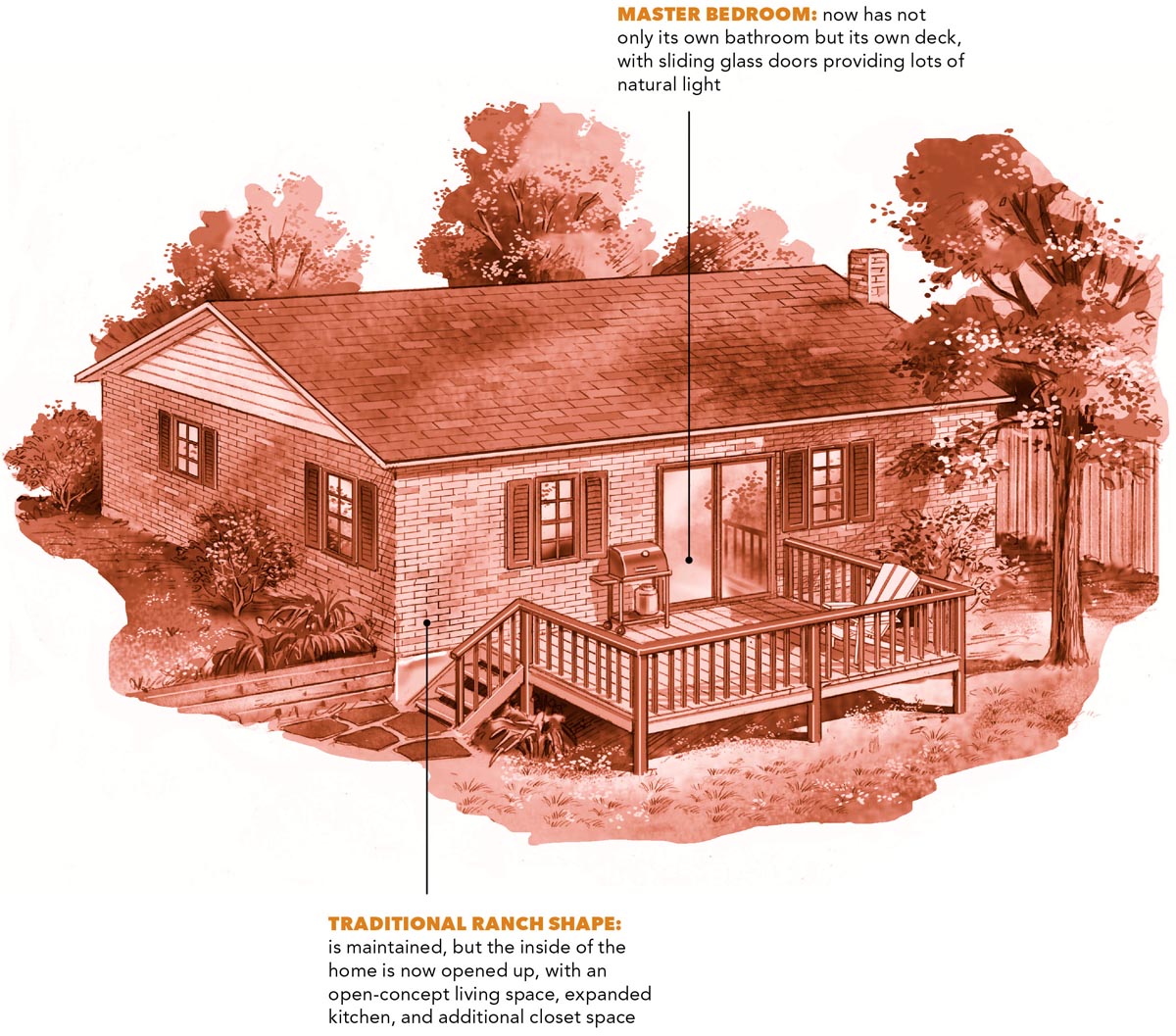

Final Floor Plan

By enclosing the porch, adding a deck, and finishing the basement, the renovation more than doubled the living space in the house, turning it into a spacious, comfortable home with an easy transition from indoors to out.

The bathroom, gutted and rebuilt, occupies the same space but is now modernized and functional, and it has been joined by another full bathroom in the basement (making that space excellent guest quarters) and a half bathroom on the sunporch (for cleaning up after gardening, fishing, and other grubby endeavors).

The kitchen, slightly redesigned, is up-to-date and easy to use, and it now features an eat-in table. A home office is tucked into the basement, along with a wet bar and wine/root cellar.

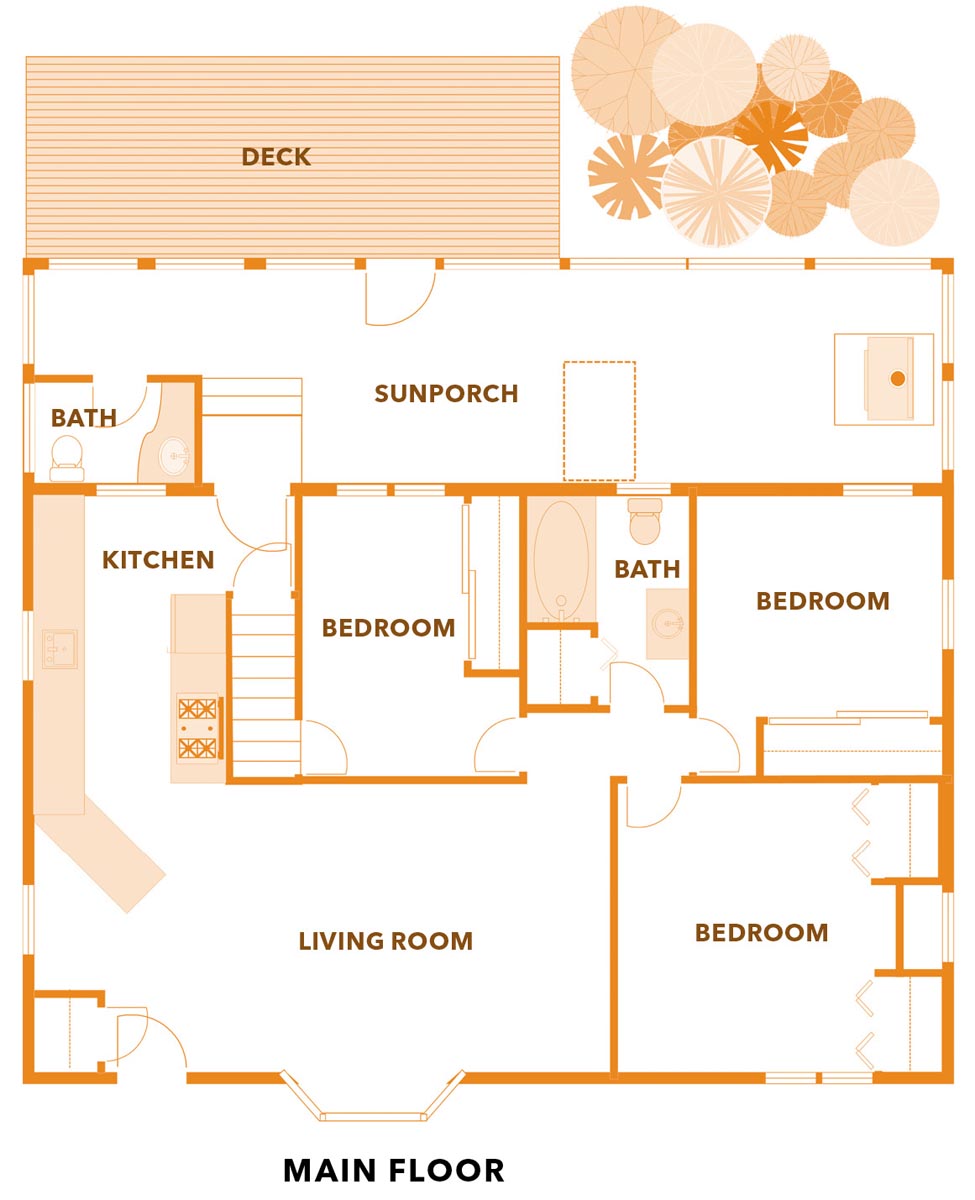

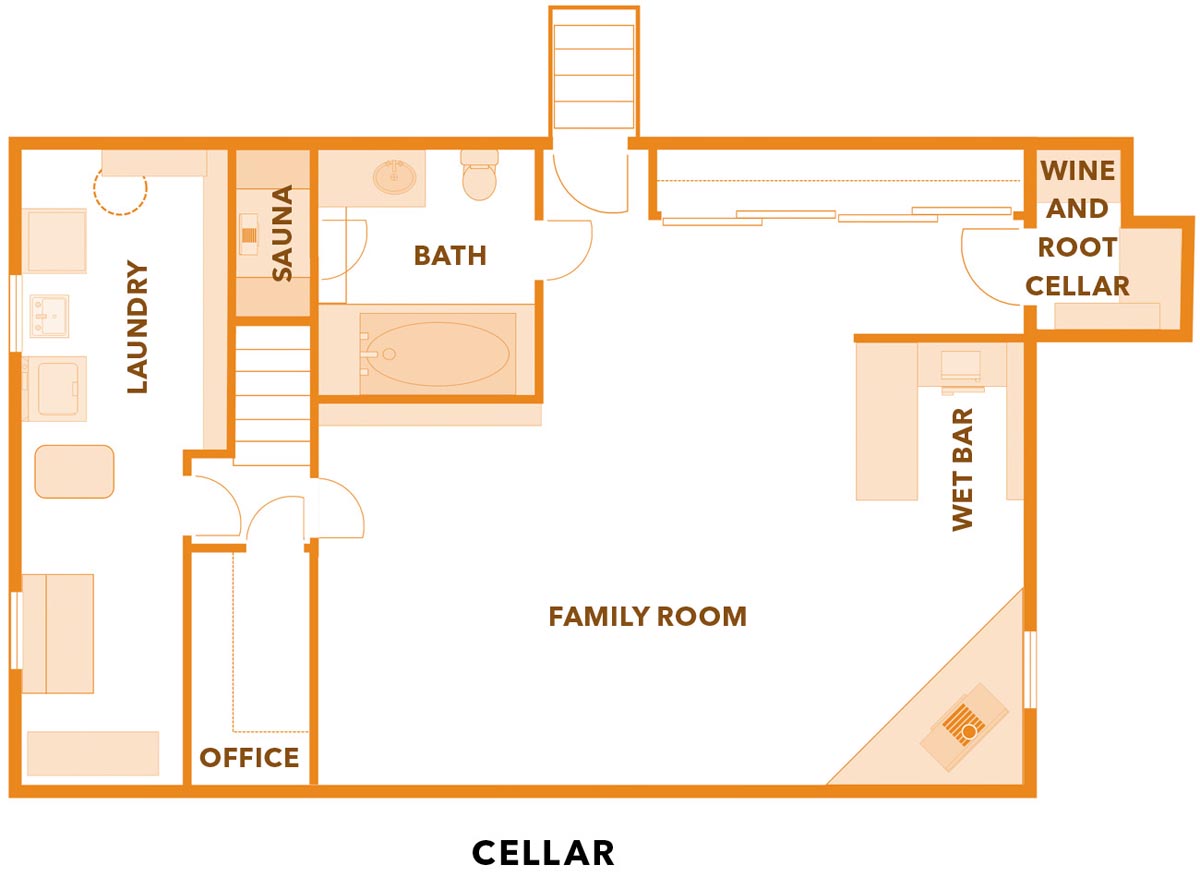

Ranch House Renovation

This ranch house had been built in 1933. As a brick house it was structurally strong but very dated. The interior was divided into a number of small rooms, and it felt cramped. We renovated the home to reflect a better use of space and contemporary housing needs.

Features

- 1,066 square feet

- 3 bedrooms

- 1 full and 1 three-quarter bathroom

- Open-concept living space

- Deck

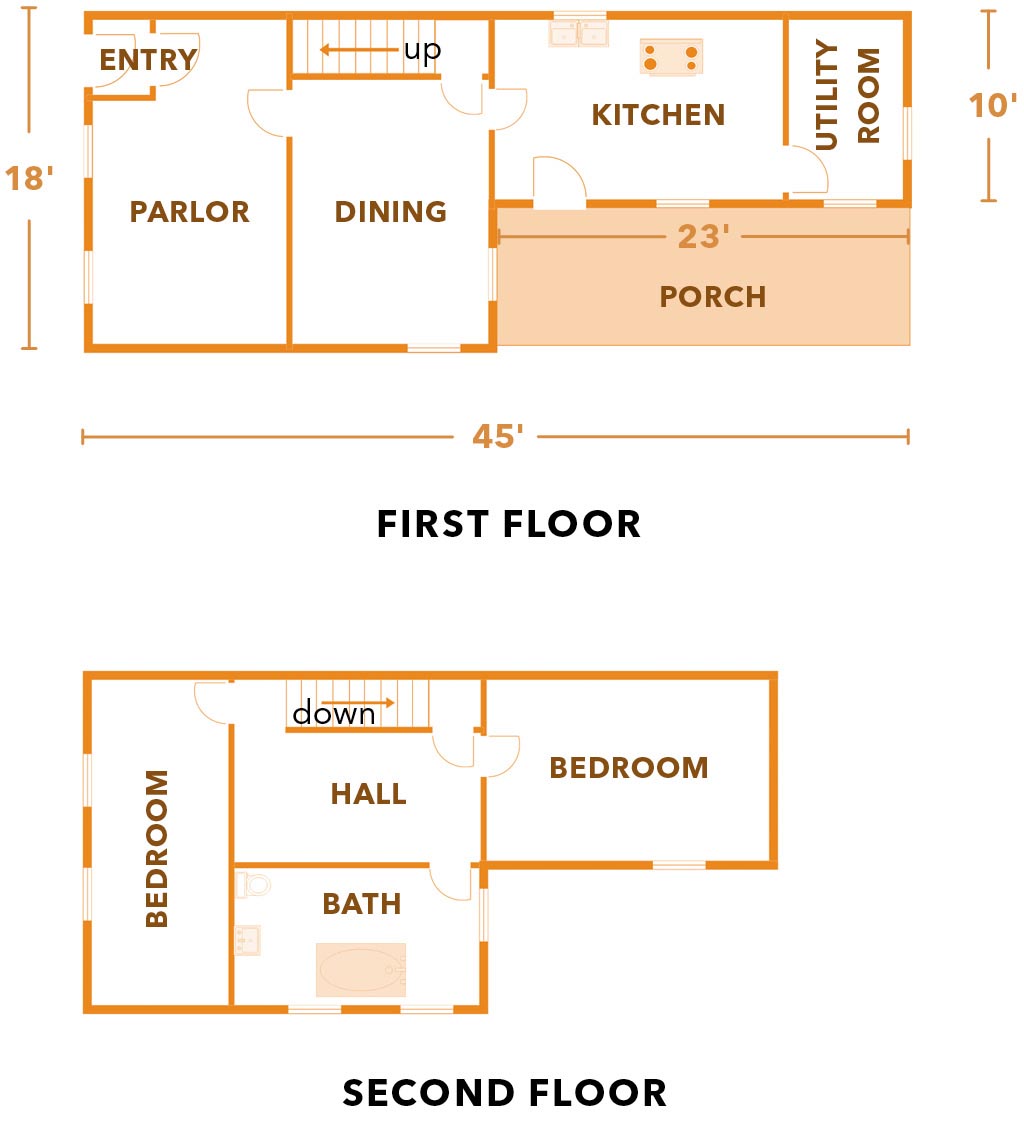

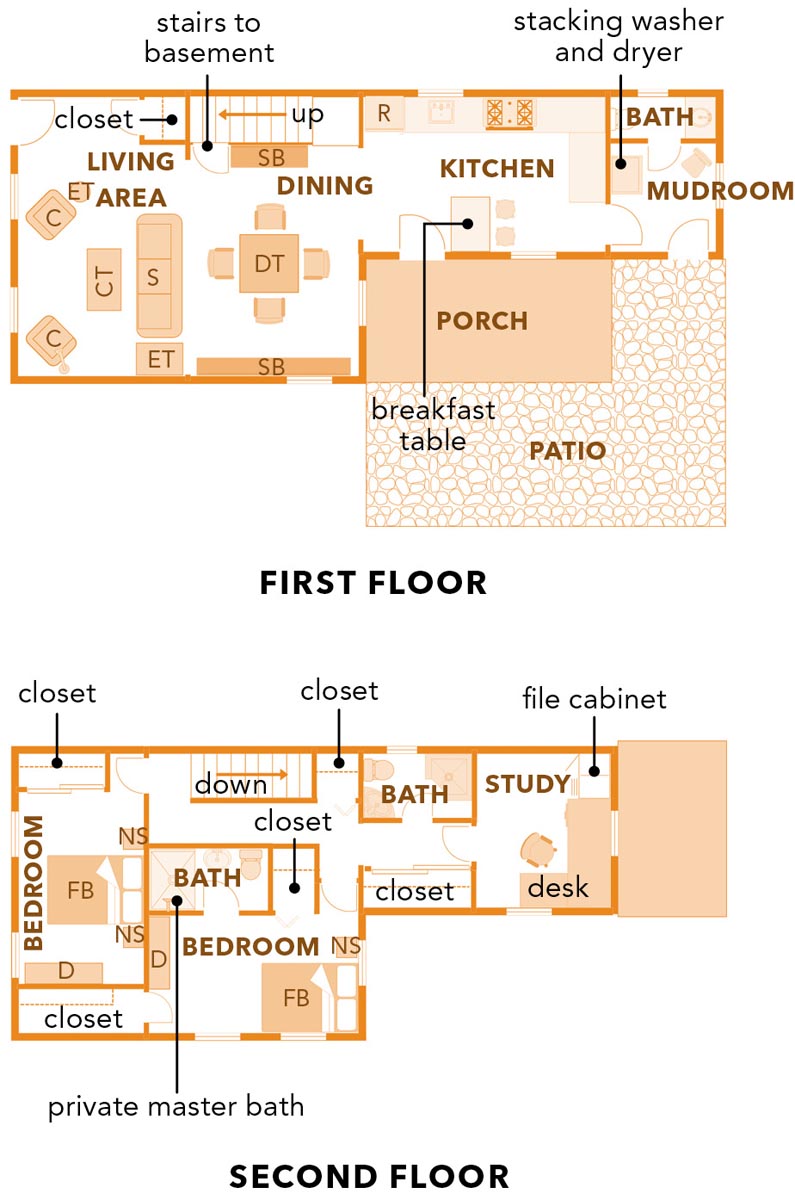

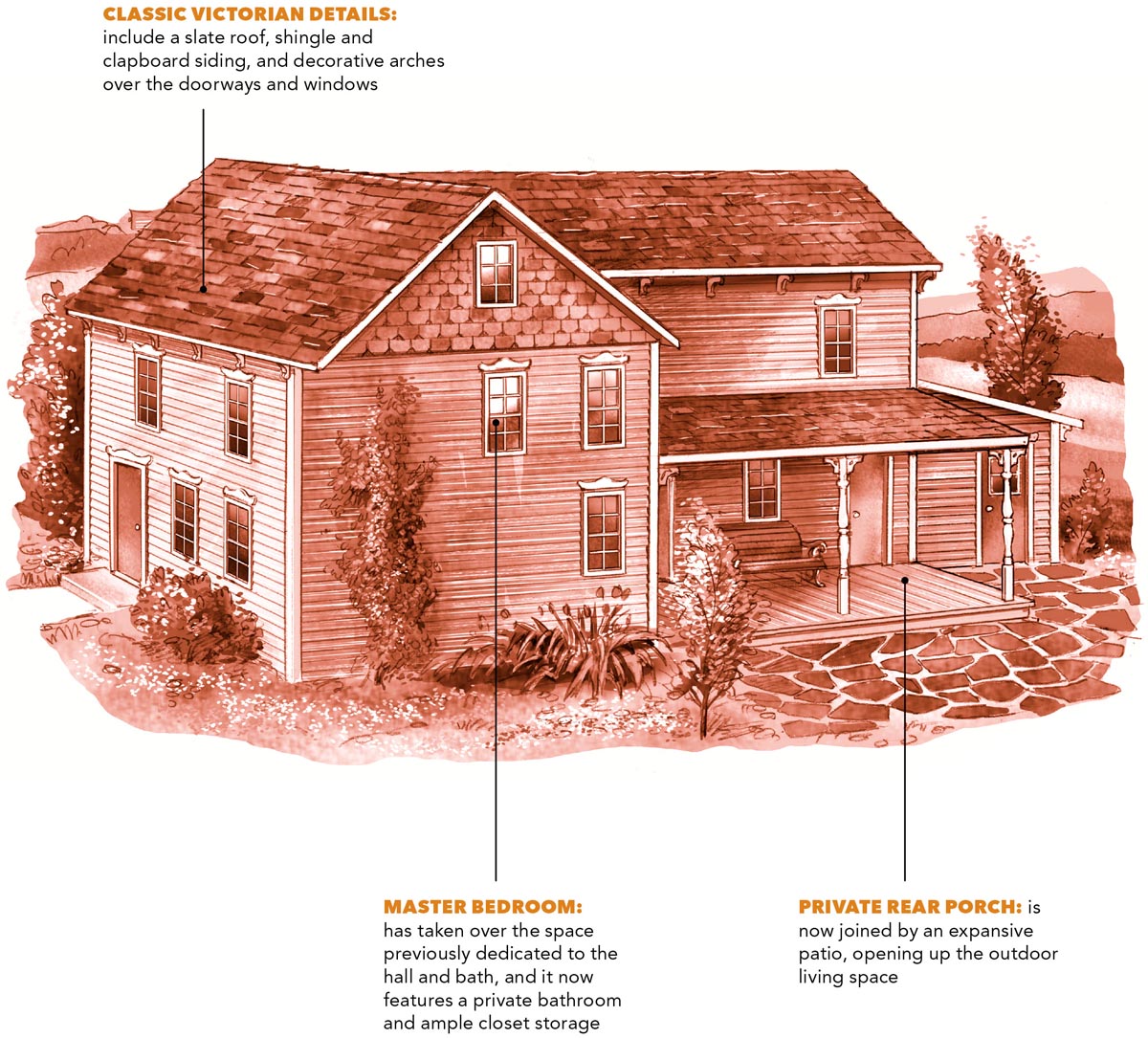

Victorian Renovation

This gingerbread Victorian home, built in 1896, was very dated, with both the kitchen and bathroom inadequate by modern standards. The project was a complete redo: the wiring, plumbing, and heating replaced, kitchen and bathroom gutted, new roof installed, floors refinished, clapboards replaced, and painting inside and out. When we were done, the homeowners had the house painted as a classic five-color Victorian.

Features

- 1,176 square feet

- 2 bedrooms

- 2 three-quarter and 1 half bathrooms

- Patio

- Porch

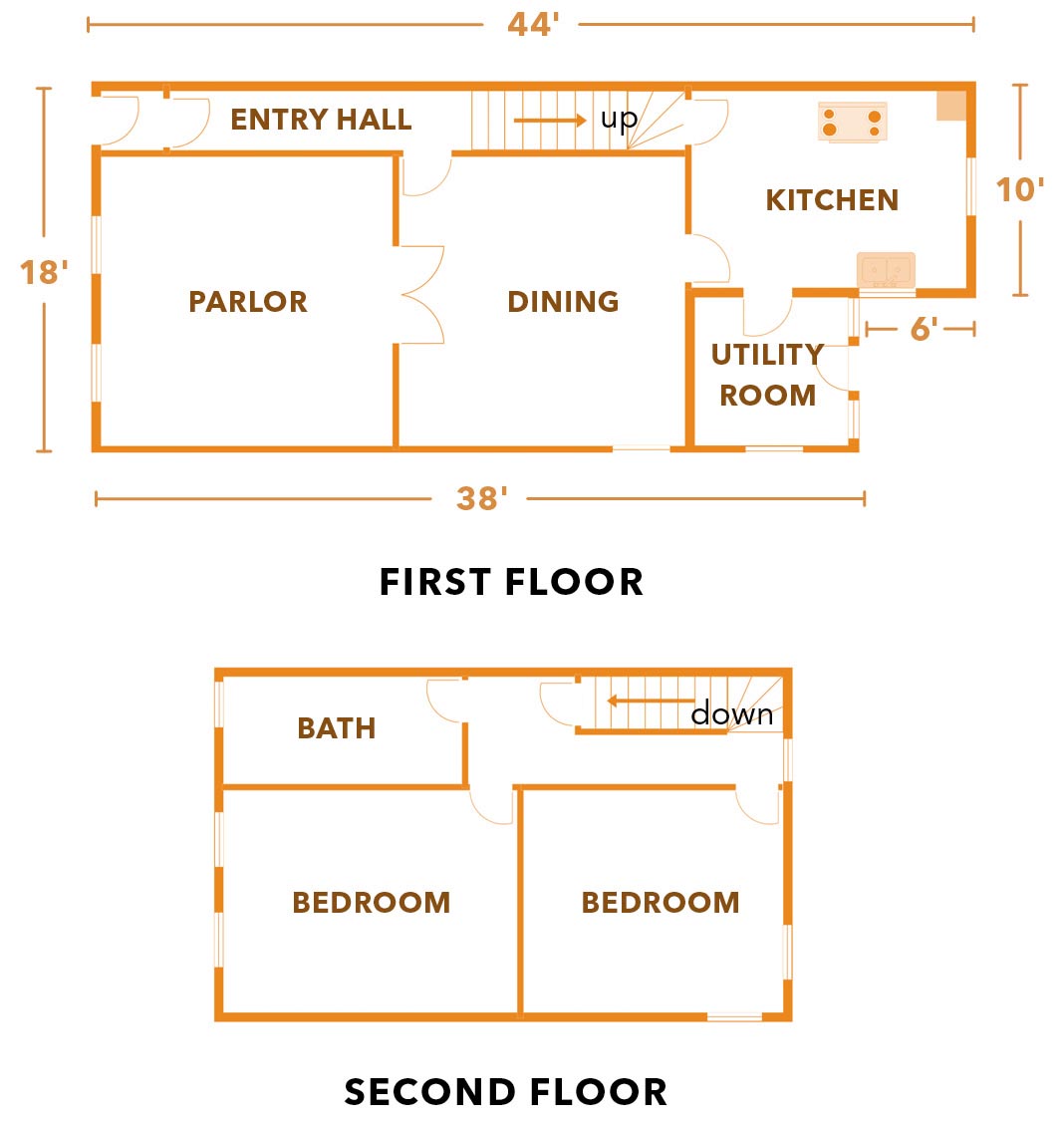

Row House Renovation

This brick row house, on a small city lot, was a condemned property, with 23 code violations filed against it, that the homeowners purchased for one dollar. It was a top-to-bottom redo, including wiring, plumbing, heating, kitchen, bath, flooring, walls, roof, and siding.

Features

- 1,276 square feet

- 1 bedroom

- 1 full and 1 half bathroom

- Open-concept living space

- Second-floor reading room

- Porch

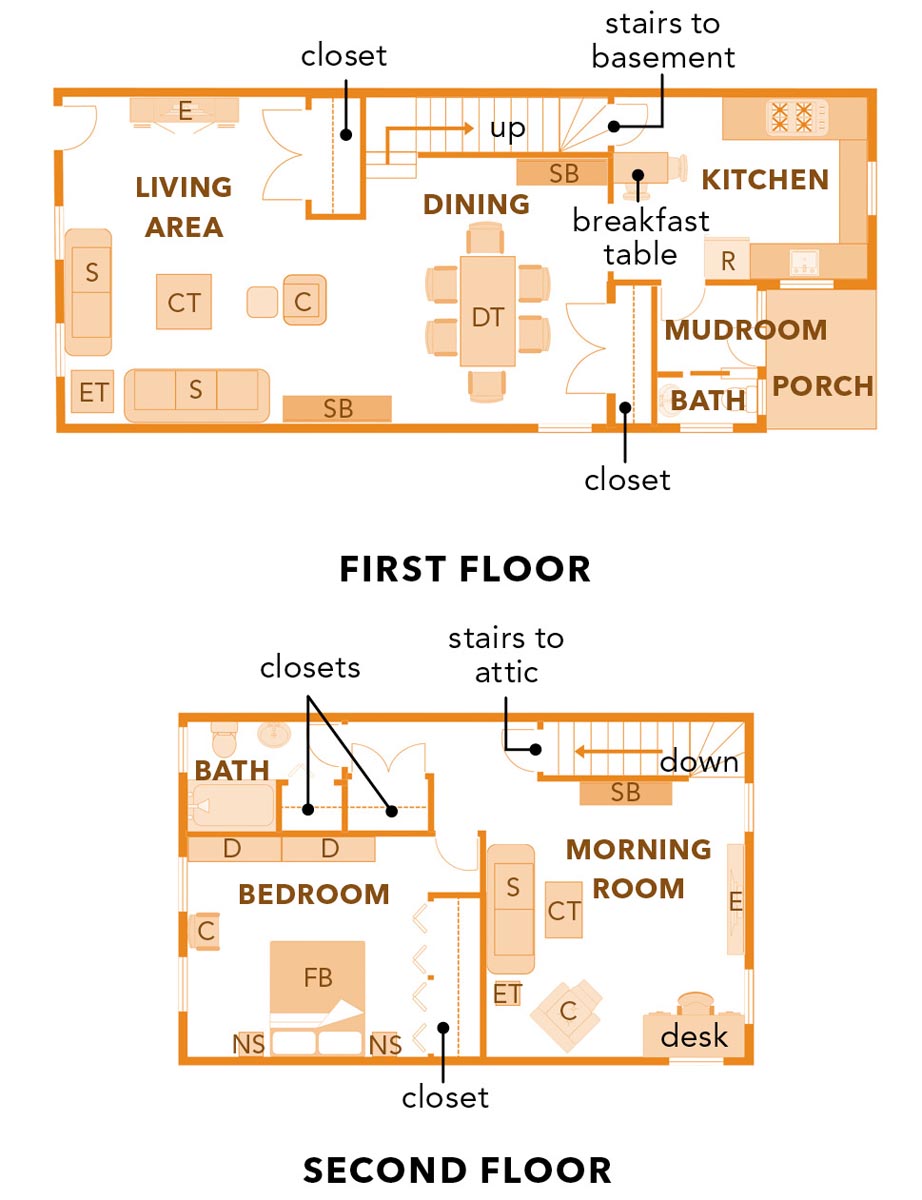

Farmhouse Renovation

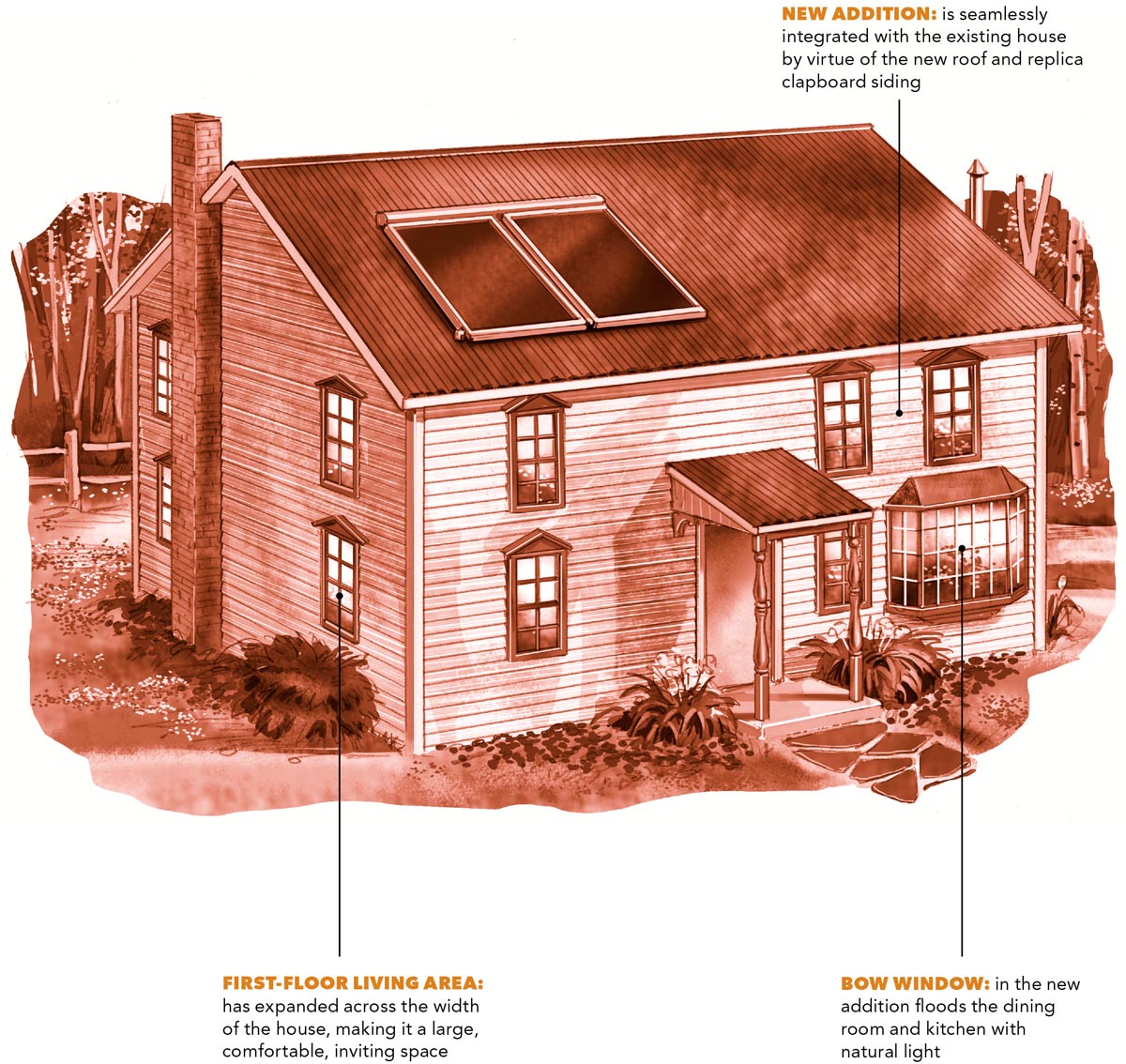

This frame farmhouse was built in the 1880s and was in dire disrepair. The plaster walls were in bad shape and had to be torn down; new drywall was hung. We replaced the entire plumbing and heating systems to bring them up to modern standards. And we designed a new addition with a country kitchen on the first floor and a master bedroom suite on the second floor.

Features

- 1,400 square feet

- 4 bedrooms

- 2 full and 1 three-quarter bathrooms

- Woodstove

- Solar hot water