CHAPTER 11

The final curtain

During our centenary year, I realised that Pretoria Boys High was seen as the sort of school others would like to emulate, not necessarily because we were better in terms of the typical benchmarking criteria but rather because of the kind of boys we produced.

One of the top independent schools with whom we had an exchange, and a good deal of contact in other spheres, quite unexpectedly decided to discontinue the exchange. The headmaster, a personal friend, said it was not about the sporting results of the final exchange, in which we beat them pretty comprehensively, but rather the fact that his council felt the contact was not a good marketing exercise for them, as our boys outshone theirs in every respect. I was sad that the exchange ended but very proud of our boys.

‘Boys High is the best school in the world’ – this mantra is one of the first things new boys learn when they arrive at Boys High. Those who taught them firmly believed it, as did I. I had inherited something special that I had not actually encountered before, or to the same extent, in other schools. It sounds a bit Harry Potteresque, but there was a magic and a passion for the school and all it stood for.

I had the privilege of visiting top schools around the country and the world, and, despite my obvious bias, I was able to compare what we did and what we produced with arguably some of the best. Overseas tours created other opportunities to see, to a degree, how we matched up with some of the world’s top schools. For this reason, I would like to recount some of my experiences in this regard.

Before my appointment, the only overseas tour that Boys High had ever undertaken was a hockey tour to the UK during the 1970s. Over the years, I had become aware that overseas tours had become more the rule than the exception in independent schools. However, I was critical of this, as I believed it came down to spending a great deal of money on the relatively few pupils whose parents were wealthy enough to let their children undertake these tours.

In 1996, I was approached by a group of enthusiastic rugby parents who believed that we were due to have a very good team the following year and pleaded with me to consider the possibility of a tour to England. Without going into detail, I eventually capitulated (in the end I had to, as they had cleverly asked if I would manage the side). Given my misgivings, my agreement came with a number of provisos, which would become the policy for all future tours, whether sporting or cultural: no boy could be omitted on the grounds of lack of resources; the tour had to be completely self-financing; the money had to be raised by the parents’ committee; and the school had to benefit from the tour to the tune of 10 per cent of all money raised. There was also to be a special budgeted item for pocket money to ensure that all students had the same amount to spend. These rules were strictly enforced, although pocket money was impossible to police.

The following year, 23 boys, four staff members and a wonderful contingent of parents set off on a five-match tour over two weeks to the UK. All our opponents were top independent schools – Harrow, Merchant Taylors’, St Paul’s (London), St Joseph’s (Ipswich; they had just won the Sevens title) and Oundle.

Harrow was our first game and in many ways the most interesting of our stops, largely because for many years there has been a tenuous but somewhat romantic link between our two schools. Both are referred to as the School on the Hill, and Boys High uses two of Harrow’s songs: ‘Forty Years On’ (used extensively by the Old Boys) and ‘500 Faces’, the new boys’ song. Both have become very much part of the Boys High DNA and are sung with great gusto and emotion.

Interestingly, Harrow was unaware of this perceived link. After the match, the staff, heads and the boys had dinner together (I allowed our boys to have a beer as the Harrow boys had this as a matter of course) and the function ended with the two teams singing ‘Forty Years On’. It is a beautiful school with an amazing tradition, yet the difference between our two schools was summed up by our head prefect, Nick Ferreira, as our coach departed from Harrow. He sat next to me and made a comment that I shall never forget: ‘Sir, they were there but we are there.’

All the schools we visited were very impressed with our boys, to the extent that St Joseph’s offered an annual rugby scholarship that lasted for about four years. In spite of all five schools being independent, all the headmasters envied my perceived freedom. They found themselves under great pressure from education authorities, governors and parents. The head of St Paul’s confided over a long dinner that while his school was top of the league table, they could only go one way and that was down, and that was more than his job was worth.

I was fortunate enough to stay with the headmasters at all five schools, and so was able to get a real insight into their thinking, leadership and educational philosophies. As an aside, we won all our games, and both adults and boys had a wonderful time.

An annual rugby festival for schools had been started in Dubai, and each year a school from each of the Test-playing nations was invited to participate. We were invited in 2000 as the South African representative. A parents’ committee was mobilised, our rules for overseas tours were implemented, and off we went. I decided to accompany the tour at my own expense. On arriving home one evening from work, I found a posse of parents at our home. They had come to present Cherry with a plane ticket so she could join the tour as well.

We won all three games against schools from Ireland, Scotland and England. I was, once again, able to compare our boys (and indeed our parents) to those of top schools worldwide, and it confirmed my view of our world-class status.

A rugby tour to Argentina, Uruguay and Chile followed in 2003. This came about because one of our parents lived in Chile. As a former South African military attaché to Chile and the national rugby coach, he was able to set up a superb tour. I was invited to go along as a back-up staff member, as coach Paul Anthony and three of our top players had to return home before the tour ended due to Craven Week commitments. The games were tough and were played mainly against boys older than ours.

Our fifth and last game, in Santiago, was played under my tutelage. We played out of our skins and had probably the best game of the entire tour. Jason Kyte as stand-in captain and Bill Schroder as stand-in coach have never allowed those who left us for greater things to forget that game, its result and how we did our bit to improve the tour’s statistics!

Not to be outdone, the hockey fraternity asked whether they could undertake a tour to Singapore and Malaysia in 2005. The parents invited Cherry and me to accompany the tour as their guests. It was a real privilege to spend ten days with such a wonderful group of parents, staff and boys. The facilities and playing surfaces in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur were magnificent, particularly those belonging to designated sports schools. It was a highly successful tour both on and off the pitch.

The final tour that I was involved in was the first-ever overseas cricket tour planned for England. I was not supposed to be a part of it, but sadly our professional coach, Denis Lindsay, was diagnosed with cancer shortly before the tour and I was asked to take his place, certainly not as coach but as the manager. It was to be a six-match tour, pitting our cricketers against top schools, including Eton and Harrow, and ending up playing Bishops at Charterhouse School.

The tour was another opportunity to measure Boys High against the top schools in the UK, if not the world. Cricket-wise we were unbeaten; the closest game was against Harrow, with the result in the balance when rain stopped play. It was a special day for the boys as one of our most illustrious cricketing Old Boys, Eddie Barlow, spent the day with us and had a braai with the two teams in the evening. Sadly, Eddie was already wheelchair-bound but was quite happy to chat to the boys from both teams throughout the day. He died in the UK not long after the tour, and we were most privileged to be asked to host a memorial service at Boys High in his honour, as well as to have some of his ashes sprinkled on Hofmeyr Oval, as they were at WHPS (Waterkloof House Preparatory School, his prep school) and at his beloved Newlands. The match against Bishops was also a fairly close game, with the respective captains being Chris Morris, who now plays for South Africa, and Craig Kieswetter (for Bishops), who ended up playing in the England one-day side. Another one of our boys on the tour was Simon Harmer, who has also played for South Africa.

Rugby tour to England, 1997: staff and boys outside Rugby School, in front of the statue of William Webb Ellis.

Eton College, looking across to the main school and the 15th-century chapel. An exchange programme between Boys High and Eton was established in 2006.

Another highlight of the tour was spending a few days at Eton College, in Windsor. We went there directly from Heathrow airport, arriving earlier than expected. We disembarked from our coach and stood around waiting for our hosts as the Eton boys were changing periods. No one acknowledged our presence as they walked past in their distinctive uniform of white tie and tails, which dates back hundreds of years. Many of the boys who passed us had far longer hair than we would have allowed, and one of our boys turned to me and said, ‘Gee, sir, Mr McBride would have a ball at this school.’ Craig McBride was one of my young deputies who was particularly tough on boys whose hairstyles did not conform to our standards.

Eton has 25 houses and our boys were billeted across the campus. I was hosted in Villiers House where the housemaster, Tom Batty and his wife, Lee, were particularly kind and hospitable. Tom and I discussed the possibility of a boy from Boys High spending a term at Eton, with some form of reciprocity. We discussed the concept with Tony Little, then headmaster of Eton, who approved the proposal and allocated funds to convert a storeroom into a small bedroom.

Our first Eton scholar, Alistair Heald, joined us for the summer term in 2007. Apart from the cost of airfare and pocket money, Eton College covered all other expenses such as uniform and tuition fees. As I write this 12 years later, the scheme is still in place.

On the morning of our match against Eton, I made the boys attend service in the school chapel, which was built at the command of Henry VI in the mid-15th century. We all trooped off in our formal attire and were immensely moved and impressed by the service and the whole atmosphere, but even more impressed were our hosts that we attended the service. This resulted in my having quite a lengthy conversation with the headmaster, as he and the staff who attended the chapel service could not stop talking about the delightful manners and smart appearance of our boys.

Eton had a similar number of boys to Boys High, but the pupil-teacher ratio there was far more favourable. In spite of a more intimate house system and the fact that all boys were boarders, it appeared that we were ahead in terms of holistic education and pastoral care. The vast majority of the staff were purely academic teachers and had little or no contact with the boys. This job fell on the shoulders of the already stretched housemasters and the relatively few staff who were involved in sport and non-sporting extracurricular activities.

Academically and historically, we were never going to match the education provided by Eton, particularly as it became more relevant and modern. Eton has many critics, of course, who view its traditional offering as anachronistic and trapped in a bubble of non-relevance. Similarly, Boys High, some 500 years younger, has been accused of being elitist and lacking in relevance. However, there is no need to throw the baby out with the bathwater simply to be relevant according to certain standards. There are values and standards that transcend time.

The other memory I have of our stay at Eton was of an elderly master, pedalling furiously, academic gown blowing behind him, on his way from the school building to the cricket oval, where our match was in progress. I heard him asking for me so I stood up to greet him. He was the son of a very famous Old Boy of ours, Rex Welsh, a Rhodes Scholar and brilliant jurist who, I was told, should have been South Africa’s chief justice but had been overlooked because of his liberal leanings. Mr Welsh just wanted me to know that his father had spoken fondly of his old school. We exchanged addresses, but sadly neither of us kept in touch after an initial bit of correspondence. He was then in his 90th term at Eton (30 years) and must have been close to retirement.

The night before our last game, at Charterhouse, I developed an excruciating pain in my left leg. The following morning, one of our parents, who was a radiologist, expressed concern that I might well have contracted deep vein thrombosis from all the flying and bus trips. I must also add that Cherry had joined us halfway through the tour, which in terms of my developing problem was an absolute godsend.

We tried to get a scan done through the National Health Service (NHS) hospital in Guildford but they were unable to assist, so we decided to continue on to London after the game as I was due to meet a large group of Old Boys. Because I was in such pain, the Old Boys came to our hotel in Russell Square, and with the help of painkillers and bit of alcohol I managed to survive until about 11 pm, when I had literally to be carried to our room as I was unable to walk.

I hardly slept that night, and at dawn Cherry phoned Ian Hay, an Old Boy, doctor and friend, for help. He was out of town but suggested we telephone for an ambulance and get me to the nearest hospital, which duly happened. At the nearby University College Hospital, I was given morphine for pain. I was about to have the required scan when all patients, other than those critically ill, were told to leave as bombs had been detonated in Tavistock Square and in the Russell Square underground station. The hospital had to be cleared so as to be available for casualties. Cherry ‘stole’ a set of crutches and a wheelchair and we sat in the foyer for hours as the casualties were brought in and we tried to get some form of assistance.

Eventually, Ian Hay managed to arrange for a scan at his paediatric private hospital and a bed at the Wellington, part of the same hospital group, next to Lord’s cricket ground. I was hospitalised for six days. My first visitor was an Old Boy, Bernard Kantor, the managing director and cofounder of Investec, who moved Cherry from our Russell Square Hotel to a boutique hotel in Mayfair, as Russell Square had been closed off because of the terrorist attack. Fortunately, the team was not out and about at the time but had been due to take the Tube from Russell Square that morning. They were due to leave that night, much to the relief of many anxious parents back home.

Fortunately, we had excellent travel insurance that covered not only the enormous hospital bill but also all of Cherry’s taxi fares, phone calls back to South Africa and ultimately our return business-class flight, as it was on that basis only that I was discharged from hospital. As a result of this experience, Bernard Kantor became a good and generous friend to us and to the school. Once again, the support of the Old Boys turned out to be so special. Investec was one of the corporate sponsors of the Nelson Mandela 90th Birthday Tribute concert in Hyde Park in 2008, and we were invited as VIP guests to that amazing occasion. It certainly was worth the pain previously endured.

After 42 years in the teaching profession, the start of 2009 heralded the final year of my career. It was a year in which we experienced exceptional generosity – generosity of spirit, generosity of love and warmth, generosity of gratitude, and generosity in the number of thoughtful gifts and tributes that we received. It was a year in which so many occasions caused me to reflect on a long and privileged career and to recall nostalgically the wonderful life lessons learned from my interactions with so many different people. It was also a year in which I started to think about life in retirement and what I could still do to make a worthwhile contribution in some way. It was a year in which an incredible journey ended but another one began.

The establishment of a world-class museum to preserve and showcase the rich heritage of Pretoria Boys High was something I had hoped to achieve prior to my retirement. I wanted it to become part of the hidden curriculum for boys as they entered the school. To achieve this, I needed someone to organise the displays and a curator to bring it to life. John Illsley, the author of our highly acclaimed centenary publication, was the obvious choice, but as head of history, second master and with all the other manifold roles he filled he would never find the time. So I gave him another illegal sabbatical, but this time for only a term.

The result was exactly what I had hoped for, and the ideal curator, Keith Gibbs, was appointed to make the museum an integral part of the school. Keith was an Old Boy, a former master and someone whose love for the school was incomparable, and he proudly hosted and guided hundreds, if not thousands, of boys, Old Boys and friends of the school through his domain. I was given the privilege of opening the completed museum.

Dr Niel van der Watt and his brilliant music department gave us many hours of wonderful music during the year and were always present at the farewell functions. Special highlights included giving Cherry and me an additional night for the annual Café Concert, to which we could invite our friends, extended family, special guests and other VIPs.

The annual Four Schools concert was dedicated to Cherry. Niel set the beautiful school prayer, which I had read every Friday for 20 years, to music and presented us with the original manuscript. All the Old Boys’ branches around the country held farewell dinners in our honour. The Cape Town dinner, held at Kelvin Grove, was attended by about 200 Old Boys. Trevor Quirk was the master of ceremonies, and he presented us with a farewell gift of a trip with Rovos Rail in the Royal Suite, arranged by Noel Durie, an executive of Rovos Rail. Farewells in Port Elizabeth, KwaZulu-Natal (held at Kearsney College), Mpumalanga and Limpopo followed, and the Limpopo Old Boys presented us with a gift of an eight-day holiday in the Kruger National Park and a framed artwork done by a local artist.

A farewell function was planned for London in the magnificent office complex of a legal firm in which Peter Rogan, head prefect in 1967, was the senior partner. I had attended an Old Boys’ function there previously and was looking forward to Cherry’s seeing it, as the offices overlooked the Tower of London, had a great view of Tower Bridge and backed onto St Katharine Docks. A month prior to the London function, which was scheduled for the last week of the mid-year holidays, I began to experience considerable pain in my right hip. Medical opinion was unanimous that the only solution was a hip replacement. My surgeon, however, was confident that we would still be able to make the trip.

I was determined to break the world record for hip-replacement recovery, the result of which was that about ten days before departure my new hip slipped out of its socket. I was rushed back to hospital, filled with morphine, and the surgeon slipped it back into place in theatre in about two minutes. He was adamant, however, that flying to the UK was out of the question. I was devastated, but it was my own fault. I wrote a speech that was read out at the function. I learned the lesson that at 64 years of age you should not show off and attempt to defy medical science.

As the year progressed, the various sports and house dinners all had a farewell flavour. Two of my most cherished gifts were a First XV rugby jersey with the number 23, duly framed with the inscription ‘Our greatest fan’, and a framed First XI cricket cap, presented at the annual cricket dinner. Both gifts have pride of place on my study wall.

I was also made an honorary Old Boy of Waterkloof House Preparatory School, having served on their council for eight years. They also subsequently made me a ‘Friend of WHPS’ – a highly prized honour. WHPS is a unique preparatory school that reminded me much of my early teaching career at WPPS. My one unfulfilled dream as head of Boys High was to have even closer contact with WHPS, to share not only our facilities – WHPS is located close to Boys High – but also our farm school, Maretlwane. I was also made a friend of Grey College at a function in Bloemfontein following our annual fixture.

Receiving a First XV rugby jersey at a farewell function arranged by the Boys High rugby fraternity at the end of the 2009 season. Abram Shalang, the long-serving groundsman, is appropriately in the foreground.

The Old Boys’ Association directors held a special dinner for us, while John Illsley and Gail Bloemink arranged a dinner in the Sommerville Pavilion for as many of the governors whom they could trace who had served with me over 20 years, together with their wives. All the chairmen who had served during my term – Brian Southwood, Antony Melck, Chris Irons, Terry Sharman and Gavin Beckwith – made flattering speeches. They had obviously forgotten some of the incidents over which I had given them sleepless nights.

Another amazing occasion was a dinner with 19 out of my 21 head prefects. It was orchestrated yet again by John Illsley, assisted by Jason Webber, and they arranged it without my knowing anything until a few days before the event (needless to say, Cherry was party to this as she had to ensure my diary was free). Only two former head prefects were unable to attend: Tassi Halka, who was unable to get leave from the NHS in the UK, and Francois Viljoen, whose ten-year reunion was to be a few weeks later and who could not make the trip twice from the United States. Two of the attendees, Neil Cutting and Greg Fisher, made the trip especially for this weekend from the UK and the USA, respectively. This occasion was so special that I would like to name all the attendees:

Neil Cutting (1990)

Anton Lategan (1992)

Greg Fisher (1993)

Ian Koller (1994)

Robert Schmikl (1995)

John Smit (1996)

Nicholas Ferreira (1997)

Trevor Bannatyne (1998)

Mark Grondel (2000)

Thomas Rundle (2001)

Devon Light (2002)

Douglas Saxby (2003)

Robert Ferguson (2004)

David Clark (2005)

Dane Blignaut (2006)

Adam Rundle (2007)

Jason Webber (2008)

Kyriacos Floudiotis (2009)

Matthew Currie (2010)

Drinks in the Mulvenna Room were followed by a superb dinner in a neighbouring restaurant, where we were given a jeroboam of red wine specially bottled by Guy Webber, an Old Boy and uncle of Jason. The bottle was signed by all 19 head prefects and presented in a beautiful glass-topped box made for the occasion and accompanied by a written message from each of them. What was kept a closely guarded secret was that they would all attend assembly the next morning, and virtually every one of them played a part in it, with Neil Cutting, Anton Lategan, John Smit and Nic Ferreira paying the major tributes. Cherry attended the assembly at their request, as she was very much part of the tributes, but characteristically refused to sit on the stage with all of us. This was a very emotional assembly and a highlight among all the farewells for us both.

A farewell dinner in honour of Cherry and me brought together 19 of the 21 head prefects (1990 to 2010) from my time at Boys High.

The next farewell function was a special assembly at Pretoria High School for Girls. We were very touched by the variety of gifts they presented to us, and I told the girls of the special relationship that existed between our two schools and the friendship that I had enjoyed with the three headmistresses – Anne van Zyl, Alison Kitto and Penny McNair – during my 20 years at Boys High.

I told the girls a story about an arrangement I inherited when I came to Boys High. My predecessor, Malcolm Armstrong, and Anne van Zyl alternated in giving one another lifts to various meetings and functions. When Anne van Zyl suggested we retain the status quo, I told her I preferred to drive so I would take her. I knew she was a strong feminist, and so I said tongue-in-cheek that I did not really trust female drivers.

A couple of months later, Rhodes University, as a promotional exercise, invited heads from around the country to spend a day at the university. Both Anne and I were invited, and on the given day were required to be at Lanseria airport at 6 am to fly to Grahamstown in a Learjet. We were met by a charming uniformed woman who served us coffee and croissants, after which she ushered us onto the plane. We did not see her again until we had been in the air for about 40 minutes. She again offered us something to drink and then gave us a weather report, estimated time of arrival and the weather on the ground in Grahamstown.

I was most impressed by her knowledge and complimented her on the fact that she seemed to know more about the aircraft’s performance than any flight attendant I had previously encountered. With a grin, she rejoined that she was not, in fact, a flight attendant but rather the pilot, and that we were flying on autopilot for a few moments while she popped into the cabin to see if we needed anything.

On our arrival, Anne van Zyl spent the whole day telling our colleagues from around the country (many of whom were long-standing friends) how my chauvinism had come back to bite me. While I would not be driven by a woman, I had no choice but to be flown by one!

The girls loved the story, and I also told them about the ‘No fat chicks’ drama and how the last time I had spoken at their school was to apologise for the chauvinistic behaviour of my boys. They loved that too, but I did not tell them about the girls’ response.

As the year neared its end, the parents’ association hosted an open-invitation cocktail party in the Abernethy Hall, which was beautifully decorated for the evening. Cherry and I were piped in, and we were amazed at the hundreds of parents who had chosen to attend. There was a rolling slide show of highlights from the past 20 years, not that we had an opportunity to appreciate it or the brilliant catering as we had queues of parents wanting to chat, offer thanks and say goodbye.

Cherry and I were called to the stage, where Bryce Blum, the chairman of the parents’ association, presented us with a Boys High rose. Then two women, dressed as flight attendants, appeared on stage with a set of very smart suitcases. We were delighted with such a suitable gift, but to our amazement it was in fact not the main gift; we were presented with a cheque for a considerable sum, which was to be used for travel, hence the suitcases. This gift was so substantial that we were able to undertake an item from our bucket list, namely, a Mediterranean cruise – not once but twice over a couple of years.

Arguably the most difficult for me was the final farewell assembly. A large group of matrics attended, although they had finished their examinations a good few weeks earlier. They wore school uniform in most cases, with some having returned from their matric holidays for the occasion. John Illsley very graciously delivered the main tribute, and I was presented with the picture of the school given to all retiring head prefects and long-service members of staff.

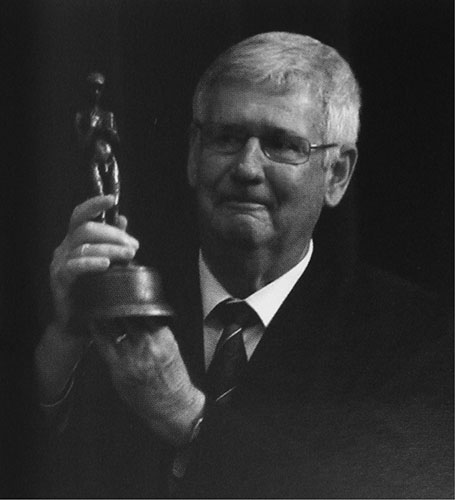

Receiving my ‘Oscar’ at the final assembly. The statuette is a bronze facsimile of the figure on the dome of the school, specially sculpted by Guy du Toit for the occasion.

The head prefect, Matthew Currie, presented me with a book in which boys from each form in each house had written tributes and messages. All the houses had done this exercise over the previous term during their tutor periods, and John, hopefully with a bit of help, had chosen the best ones and had included these with a photograph of all 50 tutor groups of 2009. To this day I have never been able to read through it to the end as I find it too emotional.

The deputy head prefect, Jordan Leppan, then presented me with my own ‘Oscar’, which was a facsimile of the figure on the dome of the school but the same size as Hollywood’s Oscar statuette. It was specially cast in bronze by Guy du Toit, the sculptor who did the bronze version of the original. With a number of favourite musical items and a reading of the school prayer for the last time, I struggled (and failed from time to time) to get through my farewell speech to the school.

The final farewell function, held the following night, was the staff dinner, attended by the full academic and administrative staff. It was an evening that Cherry and I will always remember. While this was officially the end of the formal farewells, throughout the holiday period staff and boys popped in to our home or to my office as I tried to clear out 20 years’ worth of happy labour. We were very tired, but so grateful for all that so many boys, staff and parents had done for us.