CHAPTER 2

The accidental teacher

Towards the end of my final year at school, I was offered a bursary from Old Mutual to do a BA degree, majoring in English and psychology. On graduation I would be given a position in personnel management (known as human resources today). I was not really sure, at that stage, what I wanted to do as a career, although this did seem to fit my leaning towards something to do with people. I was given a day off school to visit the Old Mutual offices, where I was royally treated by the personnel manager and his staff.

While my university fees would be paid, I still needed to pay for accommodation, and I would have to find a part-time job for pocket money and other expenses, as my mother was unable to assist in any significant way.

Some of my masters suggested that I apply for housemaster positions (called ‘stooging’), but this would have had to exclude high schools, as I would be younger than most of the boys in their matriculation year and probably some in Standard 9 (Grade 11) as well. I had great support from Rondebosch, and was fortunate that there were five primary schools in the southern suburbs that had boarding departments, so there was a chance that there might be a vacancy for an assistant housemaster.

I was lucky. After a rigorous interview with the headmaster of SACS Junior, I was offered a position for one year. I would be given free accommodation and all meals (except during school holidays), and in return I would do duty once a week and one weekend in four, as there were three other masters. If required, and if it fitted into my university programme, I could be asked to assist with some sport once or twice a week, which I was more than happy to do. In addition, I would be paid a small allowance that would largely solve my pocket-money problem. The school was also close enough for me to be able to walk to varsity – what good fortune!

The final assembly had taken place, I had handed over the leadership baton to my successor, the final examination had been written – and seemed to go reasonably well, considering how little work I had done in preparation for it – and goodbyes were said over a few days. I was staying with a friend in Rondebosch. A significant number of my friends had been balloted to do national service and were going to have a holiday before going to the army. I had not even qualified for the ballot because of my age, so I did not even need to apply for deferment or exemption to go to university.

However, there was no matric holiday for me, as I needed to make some money and had been given a holiday job in the village management board office at Great Brak River, where we always spent Christmas. A couple of my close school friends spent a few days with me at the beach before I started work, which was great. The work was unbelievably boring, though, and the greatest skill I learned was making tea – morning tea, lunchtime tea and afternoon tea for the secretary (he was the boss) and the other staff. I learned that these breaks were sacrosanct: the office door was closed for the prescribed period and potential clients had to wait outside. I started smoking again because that was what everybody did with their tea.

During this period my senior certificate (matric) results arrived by post and they were dreadful – three C’s (English, Afrikaans and history), two D’s (mathematics and Latin) and one E (physical science). This gave me a second-grade pass, which still enabled me to go to university. My raw score was above 860, which was the cut-off total for a matriculation exemption, as it was then called. Thankfully, Old Mutual did not ask for a copy of my results, otherwise their only interest in me would have been as someone to serve tea, at which I now had considerable experience.

During the second week in January, I went back to Cape Town, looking tanned, healthy but very young to commence my first stint as a housemaster. Little did I know that it was to be a way of life, in one capacity or another, for 35 years of my life. The boarding house – JE de Villiers House – was quite modern. I had a big bedroom-cum-study on the top floor and shared a bathroom with another master. Two of the staff were young teachers at the school, and the other, who became my mentor and friend, was a senior education student at the University of Cape Town (UCT), worldly-wise and very naughty.

Neither of us had transport (I was still only 17 years old) although my colleague had a driver’s licence. The Foresters Arms, which we frequented, was within easy walking distance and we had a lift up to the UCT campus most days. Our problem was, however, when we needed to go further afield. On a number of occasions, we bluffed one of the masters to allow my friend to use his car for emergencies. He would pick me up outside the gates and we had wheels for the evening.

I learned a great deal from the example set by the headmaster and his wife, who also doubled as the superintendent and matron of the boarding house. One of his aphorisms, which has stayed with me all my professional life, was, ‘You may be a boy’s friend but never his pal’. I must have passed that on to countless young teachers over many years – it was so simple but true.

Time sped by during my first year out of school. I enjoyed university life to the full and, having friends in nearly all the residences, took part in some of their less glorious activities. I discovered that, politically, I had leftist leanings, and became a fairly active member of the National Union of South African Students (Nusas). Nusas was a thorn in the flesh of the apartheid government, as its membership was open to non-white students from universities such as Fort Hare.

I realised that my bursary from Old Mutual and my accommodation at SACS might be compromised if I became too politically active, so I spent more time working to understand the ideology and being supportive of a few friends than being a proper activist. I often wondered whether this was cowardice, expedience or common sense, and I was to have the same thoughts later in the 1970s as a teacher in the state system with a young family.

These activities, together with my duties at SACS, didn’t leave much time for academic studies, but I convinced myself that last-minute cramming would do the trick. How wrong I was. Having spent more time in the Foresters Arms, the Pig and Whistle, the Grand Hotel in the city centre and the Clifton Hotel (when we could borrow a car) than I had in the lecture rooms at UCT, I failed my major (English) and so failed my first year. Consequently I lost my bursary, with the added complication that I would have to pay the first-year fees back when I had the resources.

This was a wake-up call for me, as there was no way that I would be able to stay on at UCT without financial assistance. I turned to Mr Clarke for advice. After a heavy confession session, which I think he found vaguely amusing, I realised he knew more about me than I imagined. He suggested that I apply for a teaching bursary, as he felt that I would be a good teacher. If my application was successful, I could stay on at university provided that I didn’t repeat the mistakes of my first year. I would, however, have to repay the four years of the bursary in service.

I decided to take his advice. At the time, getting such a bursary was as easy as plucking an apple off a tree. It was an example of how the apartheid system favoured young white men. In spite of an abysmal academic record, I received a bursary and my career as a teacher began by mistake, so to speak. Apart from my big role in all of this, I am forever grateful to everyone who contributed to my failing my first year at UCT. It allowed me to embark on what would turn out to be a wonderful and fulfilling career.

The teaching bursary required two teaching majors, so I chose English (again!) and history, with psychology as a third major. Fortunately, SACS were able to retain my services as they had no member of staff needing accommodation and the other student billet was filled by another friend who was taking subjects similar to mine, which proved beneficial to us both.

The other great news was that, as I had just turned 18, I was eligible to get my driver’s licence, which I did after a few lessons from one of my mother’s friends in Worcester in my mother’s Morris Minor. A very tired and uninterested official administered my driving test. While we drove around the block, he asked me if I could parallel-park. I replied in the affirmative, although parking was still my driving Achilles heel. He nodded, told me to pull up in front of the offices we had just left, and asked me to follow him. Five minutes later, I was a licensed driver.

On returning to my mother’s flat, another surprise awaited me. Without telling me, a cousin had suggested to my mother that she should upgrade to a Morris 1000, and a hire-purchase deal had been made that she could just afford. Provided that I could cover all the petrol and service costs of the Minor, I could have it for Christmas. I had a bursary to stay on at UCT, I had accommodation and a stipend giving me pocket money, and I had wheels. What more could an 18-year-old ask for?

My second year at university passed without much incident with a good balance of academic time, hostel duties and a fairly extensive, fun-filled social life. My little car managed to get us to wherever we wished to go, although carrying four passengers did make going up the hill to UCT a slow and laborious process. Taking passengers was a financial necessity, as everyone contributed to the cost of petrol for both business and pleasure.

The only indignity I suffered occurred twice a week when one of the girls in our class swept by in her boyfriend’s Jaguar, giving us an imperious wave as we laboured up the hill. I hated that moment, as I was quite keen on her, but if cars were to be the yardstick by which she measured her affections, I had no chance.

The other opportunity that my car afforded me was an introduction to District Six. Somehow, I was told about an immigrant from the UK who had a car-repair shop in District Six and serviced cars while you waited. It was said to be the least expensive car service in Cape Town. I went to see him, we became friends, and for the following few years he did all the repairs and servicing I needed.

While waiting for my car, I used to wander around District Six, and over time I met some of the fascinating people who lived in this vibrant, somewhat run-down suburb. There were gangs and drug dealers, but I never felt unsafe as I walked around and talked to the residents. Muslims, Christians and Jews alike lived together, worked together, laughed and had fun together.

A few years later, in 1966, the government declared District Six to be a ‘whites only’ area, and from 1968 started removing people by force to the Cape Flats some 25 kilometres away. By 1970 the demolition of houses and properties began, including my friend’s garage. By 1982, apart from a few religious buildings, District Six was a tract of open land.

This disgraceful episode of social engineering had a major impact on my life and shaped my social and political philosophy. During this period, I became friendly with a young man of my age who lived in District Six but who worked at UCT as a technician and as a result was studying – most probably illegally – towards some degree. I visited him at his home on a number of occasions, but we were unable to travel on a train or bus together or even to sit on the same bench at the station – another example of the evils of apartheid. I lost touch with him once I graduated, which I now very much regret.

The year, unfortunately, did not end on a particularly good note. I was devastated by the assassination of President John F Kennedy, one of my heroes. I also received the news from the headmaster of SACS Junior that both my student friend and colleague and I would not be able to return as housemasters the following year, as he had two new members of his teaching staff who had requested accommodation. The good news, however, was that I passed all four of my subjects and could move confidently into my next year.

Academically, the highlight of the year was undoubtedly the lectures conducted by the renowned Professor Jack Simons on Comparative African Government and Law. Both the subject matter and Professor Simons’ knowledge were fascinating, and his daily welcome to the members of the police’s Special Branch sitting at the back of the class was something we all looked forward to. I think Professor Simons was a banned person in those days; presumably he was allowed to lecture but probably had his material carefully checked.

I am not sure if the visitors thought they were in the lecture room incognito, but they stuck out like caricatures of typical police spies. The professor would welcome them warmly and assure them that there was nothing contentious in his lecture that day, and they were welcome to leave and enjoy a cup of coffee in the student union. This would be met with roars of laughter and derisive comments as we all watched these gentleman cringe and sink lower in their seats.

My two obvious challenges for 1964 were where to live and how to make some money to make living possible. I contacted all the boarding schools, both primary and senior, for a possible assistant housemaster post, but to no avail. With university lectures only starting in March, and not having to return to Cape Town for the start of the school year as in the past, I was offered a job on a wine farm owned by friends of my mother’s in the Rawsonville area.

The job was for two and a half months, and was well paid. With food and accommodation thrown in, I managed to build up quite a substantial sum, which considerably eased my financial situation. The job was physically tough but I learned quickly. It was grape-harvesting season. Together with a local farm lad, probably a year or two older than I was, I was positioned on the back of a big truck. We had to ‘catch’ the enormous baskets filled with grapes that were brought in an endless flow by the pickers, empty them into the truck, and then toss the baskets back.

Until I developed the right technique, I spent most of the first few days on my back in the bed of the truck covered with sticky grapes, bleeding profusely from scratches from the heavy baskets – much to the amusement of the other workers. The trick was not actually to catch the basket, but rather to guide it as it flew up towards you, empty it virtually in flight, and then catch it when empty. Once I mastered this, the aches and pains subsided, and I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the farm.

As with my visits to District Six, I found that I enjoyed the company of my coworkers, learned a great deal about their lives as farm labourers, and even enjoyed the odd ‘dop’ (tot) of the cheap wine they were given at the end of the working day. The practice of part-payment for labour with alcohol – the dop system – has been severely criticised by labour practitioners, but I have no doubt that it still continues. As my friendship developed with some of my coworkers, I was told by my employers that it was not appropriate for me to visit them or become too friendly, as I was a white boy and they were coloured. It was not an unfamiliar admonition in the mid-1960s, but it was something I found difficult to accept.

On returning to Cape Town for the start of the academic year, I was invited to live with a school friend and his sister for a couple of months while their parents were on an extended overseas trip. This was an absolute lifeline. My friend was taking some of the same subjects as I was, as he too was studying to be a teacher, so we did academic work together as well as having a great deal of fun in our ‘off time’, which seemed to be more considerable than our ‘on time’. Why was it that I did not seem to be able to learn from my past experiences?

My next billet was with family friends who had a student pad in Vredehoek. They, too, were extremely good to me, and the subsidised living, together with some sport coaching at SACS Junior and some tutoring of boys there who were battling with English, helped to keep some money in the kitty and get me through the year relatively comfortably.

In August, I was contacted by the headmaster of Western Province Preparatory School (WPPS) and offered a ‘stooge’ position for 1965, which I accepted with alacrity. Little did I realise then the significant role my association with WPPS would play in my life, and that I would be involved there for the next five years.

Western Province Prep (known fondly in Cape Town and beyond as ‘Wet Pups’) was, and still is, an independent prep school, feeding mainly Bishops Diocesan College, St Andrew’s College (Grahamstown, now Makhanda) and, to a lesser extent, Rondebosch Boys’ High. It had a junior primary department from Sub A (Grade 1) to Standard 2 (Grade 4) and a senior school from Standard 3 (Grade 5) to Standard 6 (Grade 8). With a commitment to academic excellence, classes seldom if ever exceeded 22, and there were two classes in each standard. These numbers were maintained throughout my five years there, as they enabled the school to be financially sustainable and yet to provide the holistic education and individual attention unique to a few preparatory schools across the country.

The school attracted an interesting cross-section of South African society – obviously all white in those days. While alumni of the feeder schools made up a large section of the intake, there were many rural boys, quite a few who were Afrikaans-speaking, and a smattering of Cape Town high society, including the son of a hereditary knight, the son of a peer of the realm and the son of Italian royalty. The school is an Anglican Church school and has an Anglican chaplain, while the Bishop of Grahamstown presides as the Visitor to the school. Equally interesting was its eclectic mix of staff members, most South African but with a sprinkling of fascinating, well-qualified teachers from the UK.

My first two years at WPPS (1965 and 1966) were stooge years during which I was required to do various duties as could be fitted in with my university commitments. One of those was to assist with the Sub A’s and B’s (Grade 1’s and 2’s), who were almost a separate part of the school. While I was never very good with the little guys, watching the teachers in that department at work was an eye-opener. They are a special breed and do wonderful work. So-called news time, when the little boys were required to provide snippets of usually family news, could be particularly revealing. On one occasion a six-year-old told us all that his mother was so angry with her chauffeur that she would not allow him to sleep in her bed that night. One of their favourite hymns was the well-known ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’, except the first lines became ‘All things bright and beautiful, all teachers [instead of creatures] great and small’ – very apt, as one of their teachers was about five foot three, another about six foot three, and a third enormous in girth. A fourth teacher, a lady who assisted them for physical education, on one celebrated occasion issued all the little boys with tennis balls and then yelled at the top of her voice, ‘Leave your balls alone – I will tell you when to pick them up.’ The instruction reverberated across the entire school campus, much to the amusement of staff and boys alike. It took months for her to live this incident down.

As the master on duty, once a week I was required to supervise breakfast and lunch (the entire school had lunch) as well as dinner, evening prayers and lights out. Weekend duties were relatively easy, although Sundays for those who were not excused after sport on Saturday was quite a long day. We walked the boys to church (our chapel church was Christ Church in Kenilworth – quite a long walk) and were encouraged to take the boys out for a picnic lunch to the beach or the mountain. Fortunately, this duty occurred at most only twice per term, so it was not too bad. I coached rugby as well, and in my second year was asked to take over the swimming coaching. As well as having free board and lodging, I was paid for all additional duties, so for the first time since leaving school I was in quite a sound financial position.

It was during these two years that I had the privilege of interacting with, and learning from, the most amazing teachers and human beings. I also realised the value of having some real eccentric characters on a teaching staff. They are the ones that the pupils remember with great affection, and who make a great impression on their developing personalities.

Miss Dorothy Saint Hill had been at the school for close to 20 years. She was a fearsome character but with a heart of gold. The first thing she taught me was never to pour my own tea at break in the staffroom. She had been pouring all staff members’ tea for 20 years, never forgetting the amount of milk and sugar required, and woe betide those who tried to sidestep the system.

She was an outstanding English teacher and adored the boys – although she didn’t like to show it. She enjoyed the company of the male teachers but was firmly entrenched as the senior woman on the staff, and made sure all her female colleagues understood that. She loved a party, and after a few gin-and-tonics and glasses of wine the tough façade crumbled and she was great fun.

Her male counterpart, in terms of longevity and seniority, was Peter MacPherson, a legend at the school. Also unmarried, his life revolved around his boys, his cricket team, his adventure camps, athletics, boxing and mathematics. Peter’s favourite watering hole was the Vineyard Hotel, and as stooges we were required to accompany him there from time to time. As WPPS was an Anglican school, he felt justified in using a quotation from the scriptures, which exhorted the workers (perhaps the disciples) to ‘join the others in the vineyard’. Out of context it may well have been, but who could ignore an instruction from the Bible and from Peter MacPherson?

One of the most eccentric and memorable characters was James McIntosh MA (Cantab) from the UK, who spent a few years at WPPS. James had been a member of the Cambridge Union and, as such, a debater par excellence, an experienced and well-read history teacher but above all a great character. His love of history, all things English and cricket was only surpassed, I think, by his love of gin, but this was well controlled during the working day.

The school had recently purchased a lovely old house called Glenifer, located a block away, which it was hoped would provide accommodation for a number of staff members, including stooges. James was offered a suite of rooms there, which he enjoyed as it gave him more privacy. His only concern was that he was going to be overtaken by the ‘creeping death’, as there were bits of damp in the old house.

Wherever James went, he carried a large leather bag. We assumed it contained exercise books that he was marking, but when it accompanied him to the Vineyard, our curiosity got the better of us and we asked what it contained. It contained a bottle of gin, a Confederate flag and a cricket ball, as well as other inconsequential bits and pieces. We never understood the purpose of the flag, but the gin was in case of unexpected eventualities, and the cricket ball was a defensive weapon in case someone tried to molest him on the way to and from the Vineyard. He could not drive, so his almost daily trips to the hotel were on foot.

We, as dutiful stooges, accompanied him on occasion, and there were few that ended without incident. The most memorable one was when we returned to the staff dining room after a particularly long pre-dinner session. Our dinner was congealed and inedible, and the sight of it made James unplayable. He climbed on a chair and head-butted a rather valuable-looking glass lamp that hung above the table, resulting in a bad cut to his head, shards of glass all over the table and plenty of blood. We cleaned the room (and James) as best we could, mindful of the fact that the room served as the staffroom during the day and the headmaster met the full staff there every morning before classes began. We did a good job; the only thing missing was the light fitting, the loss of which, it was assumed, was due to the high jinks of the stooges.

James certainly was high-maintenance, but he made an impact and was warmly remembered by boys and staff alike.

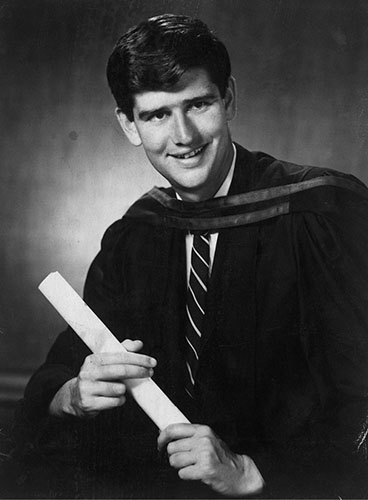

To my great relief, and I am sure to the surprise of others, I graduated at the end of 1965 with what must have been one of the worst BA degree passes ever at UCT. I then did the Secondary Teachers’ Diploma in 1966, a prerequisite for teaching in a state school. There were very few useful or interesting components to that course, although I did enjoy the practice teaching that we had to do in both English (at Rondebosch and Lansdowne High) and Afrikaans (at Hoërskool Groote Schuur).

Graduating with a BA from the University of Cape Town, 1965.

As I was about to start applying for teaching positions, the headmaster of WPPS offered me a permanent post and said that the board of governors would buy me out of my bursary obligation to the Cape education department, the only stipulation being that I would have to teach at WPPS for three years. While mulling over this offer, I received a communication from the South African Defence Force (SADF) to say that I had been balloted and that my call-up would only be deferred if I were to continue studying or had a full-time position.

The headmaster suggested that he contact the SADF to discuss my situation, and before I knew it, he had secured a complete exemption. I never understood how he achieved this, nor did he ever tell me. I was fairly sure that I would not make a career out of teaching junior school but felt obligated – and happily so – to accept the WPPS offer for three years.

The following three years were extremely happy and fulfilling on a personal and social level, although professionally I realised with increasing certainty that primary-school teaching was not my forte. I moved into Glenifer with three other young single masters, two of whom were stooges. I taught English and Latin to the Standard 6 (Grade 8) level and was heavily involved in the extracurricular programme.

In spite of being a poor swimmer, I ran the swimming and became a reasonably competent coach. As our swimming became more successful and WPPS became a force to be reckoned with in primary-school swimming, a new pool was built and the sport improved dramatically. We won leagues and individual galas during this period, and a number of our boys achieved provincial selection. I was also heavily involved in rugby, and ultimately coached the First XV.

Western Province Prep School swimming team (winners of a Western Province junior school gala).

We were fortunate to have talented sportsmen among our stooges, including an international swimmer and first-league rugby players, one of whom became a Springbok full-back a few years later. These men added immeasurably to the coaching and profiles of the various sports.

The cultural side of school life was strongly emphasised, with music and choirs being particularly strong. It was fascinating to see how tough 12- and 13-year-olds, with bloodied knees and bruises, were transformed into angelic choristers in maroon cassocks and white surplices in the choir at Christ Church on Sundays. There was also a strong emphasis on outdoor pursuits, and camping trips and hiking excursions were enjoyed by many.

One of my housemates, a very talented academic and sportsman, used to have long and somewhat inane conversations with a girl he had met and whose company he obviously enjoyed. The rest of us could not help overhearing these conversations, as the communal telephone was located in the lounge that we shared. Some of the rubbish he spoke was amusing as he described us to her, with my claim to fame being that I was a member of the ‘Worcester landed aristocracy’. I got off lightly, though, as one of my colleagues was described as a good-looking guy but with the handicap of having a tormenting rectal itch for which he had to spend vast sums of money on a product called Soothe.

He went out with her every now and then but never brought her home, so we never met the voice on the other end of the telephone. He had mentioned that her parents lived in Great Brak River, where I had spent all my childhood holidays and still went for Christmas.

My housemate finished his stint of teaching at WPPS and went overseas to further his studies at Oxford, and I went to Great Brak for Christmas. There, I met a gorgeous bikini-clad girl on the beach, and when I introduced myself she asked me whether I was a member of the Worcester landed aristocracy, as she recognised my name. She was the voice on the telephone. Her name was Cherry Melvill. The fates seemed to have brought us together.

We were young, both only 20 years old, and we had so much fun together. We were kindred spirits. I immediately recognised her strong personality and her warmth. Over the years, our bond grew only stronger and stronger.

Cherry and I leaving Christ Church, Kenilworth, 22 June 1968.

Living together was not an option in those days, so we decided to take the plunge and became engaged, with a view to getting married in June 1968. Cherry worked as a secretary/receptionist for a veterinary practice in Rondebosch and earned more than I did as a first-year teacher – R120 per month after tax. Her parents had returned to Rhodesia and were struggling financially, and my mother had retired and had moved to a retirement centre on a very small pension. Neither family could finance a wedding, and nor could we.

The headmaster and his wife, the staff and many parents seemed to find this all very romantic and exciting (as did we), and so our wedding-to-be became their wedding-to-make-happen. Glenifer was divided so that we could live in one side and the bachelors in the other. Christ Church was booked, and the chaplain was to marry us. Although it was at the start of the school holidays, the choir would sing. The reception was to be held in the school hall; the catering and the cake were donated, and everything seemed to fall into place.

Because of my peculiar family circumstances, we had to accommodate my father and his third wife at the wedding, so we decided to have a morning wedding, and planned the reception as a pre-lunch drinks and snacks so that there would be no set tables and place settings, and people could mill around, thus avoiding any awkwardness and embarrassment. Wedding presents and assistance of various kinds started arriving before the invitations went out, and we eventually found that we had to invite everyone who had helped in whatever way. So, it became quite a large WPPS wedding; there were more WPPS parents and staff than family and friends, but they had adopted us so we adopted them.

Our wedding day, 22 June 1968, was a beautiful Cape Town winter’s day, and saw the most perfect wedding and the start of a marriage and special partnership that lasted 50 years. Unbeknown to Cherry, I had been saving a bit every month and was able to book a honeymoon venue on the Wild Coast. We pulled away from the front of the school with the obligatory smelly fish in the engine, clacking cans and streamers attached to the bumper, and lipstick slogans all over the car.

As we turned the corner, we saw one of our guests, a parent whom we did not know all that well, flagging us down. We stopped and soon realised that she had had quite a bit to drink and was clutching something under her coat. She asked if we could take her home as her husband had left without her. I refused, but Cherry dutifully got out and climbed into the back seat (it was a two-door car). I slipped as low as I possibly could behind the steering wheel, as it must have looked as though we were setting off on our honeymoon with my mother-in-law beside me and my bride in the back.

The next moment, the woman turned to Cherry and produced from under her coat an open bottle of the champagne we had served. I deposited her as soon as I could, and after regaining my sense of humour, we had a good laugh about the incident.

The last 18 months of my contract at WPPS passed quickly and happily. We loved our house, although it was sparsely furnished, and as we both worked were able to enjoy the odd treat. My colleagues, Cherry’s employers and our many friends among the parents were exceptionally kind to us. What struck me was that the parents befriended us with no agendas; we never felt that there were ulterior motives to their friendship, and we remained friendly with many of them long after we left the school.

We both decided that, from a career point of view, we would move on at the end of the contract period, and I was totally upfront with the headmaster as I moved into the final year. I tried to analyse what it was about primary-school teaching in general, and independent primary-school teaching in particular, that made me decide to move on, in spite of the wonderful treatment we had received at WPPS. Although not a great academic myself, I felt a lack of intellectual stimulation, and the immaturity of the boys irritated me at times.

I decided to embark on a postgraduate Bachelor of Education (BEd) degree, which was offered as a part-time degree for serving teachers. A number of my friends and colleagues were doing it, and it certainly was more challenging than the compulsory diploma year, which we all had to do but which was a bit of a waste of time.

I also found that there was a tendency among the teachers, particularly among the men, to have favourites. While I was never aware of any unacceptable behaviour or relationship issues, with the wisdom of hindsight and experience, I think there may have been fertile ground and opportunities for unhealthy relationships to develop. On the positive side, I have a firm belief that primary-school teachers are very special people and that teaching at that level is indeed a vocation that I feel is often not appreciated as it should be.

There was no road-to-Damascus experience that made me want to become a teacher. In many regards, I was the accidental teacher. One thing I did know from early on, though, was that whatever career I chose, it would have to do with people. Once I started teaching, I also realised that I loved guiding and leading people. The fact that I did well at WPPS, in spite of its being a primary school, and the leadership opportunities I got there made choosing a career in teaching a no-brainer.

In the next few years, I was extremely lucky in the promotion breaks that came my way at regular intervals. As will be seen from my various career moves, I seemed to make them at the least opportune times! Cherry became pregnant, and our first baby was due one month after having moved to a new school and a new home – not clever, but we believed we would cope. New challenges lay ahead as I accepted a post at SACS for January 1970.