At this book's writing George bears some wounds from being 91 years old, but none of them are from having served in World War II. This is a phenomenal fact given that he, along with Fred Dyer, another pilot from his 488th squadron, holds the unofficial U.S. record, at 102 each, for the number of bombing missions flown in the history of that grim war. Both survived the war but, between them, they had been shot at and hit countless times, blasted by missiles, shrapnel, and gunfire. They survived bailouts and crash landings and lived to fly again and again, more than doubling the required number of missions, first set at 25, then raised to 35, and finally plateauing at 50. Their piloting skills were exceptional, their devotion to duty far exceeded expectations, and their bravery was beyond question.

There is another interesting fact about George. Remarkably, he is the last surviving Air Force member from whom many of the characters in Joseph Heller's classic novel, Catch-22, were loosely drawn. He is George L.Wells and he is, to a degree, also Captain Wren.

George L. Wells, holding his well-worn black book into which he recorded each of his 102 missions.

Sandy-haired and freckled, George, a child of the Depression, was raised in small town USA. Cedar Brook, New Jersey sported a population of less than 300. His family, living about a mile outside of town, fared well for country folk prior to the Depression. He did all of the things boys do — attended school, played ball (especially baseball and soccer), became his 1937 senior class president, graduated, and got a job.

Since his parents could not afford to send him to college, he started working as an apprentice in a print shop for $8.00 a week. After he’d worked for two years, union organizers came in and told him his salary would increase to $16.00 a week if the print shop employees voted to join the union. Of course, the employees voted for it but the print shop, in order to be able to accommodate the increased wages, laid off the last two persons hired, one of whom was George.

In 1939, he was alerted by his older brother, Oliver, that his country was headed for war. On his advice, George joined the New Jersey National Guard and, with war drums beating, his life abruptly reeled into totally unfamiliar territory.

The world's military pot had been simmering but now it was roiling, bubbling, and boiling. Germany, Italy, and Japan were throwing massive logs on the fire with their passion to increase their power and force their expansions at the expense of neighboring countries.

As Adolf Hitler moved into power he promised his country an end to the humiliating conditions caused by World War I. He began re-creating and preparing the German army for a war of conquest. Here was rising a man, unimposing at 5’9” and 150 pounds, with a flattened haircut, a scrap of a moustache, and dead-serious dark eyes. A father-thwarted artist's passion had simmered inside of him but now he was mutating into a fanatical and tyrannical alpha male who, in the ensuing few years, would declare, “Brutality creates respect.” “Go ahead,” he commanded, “kill without mercy. After all, who remembers today the Armenian Genocide.” He was to decree that the Nazi Party “should not become a constable of public opinion, but it must dominate it. It must not become a servant of the masses, but their master!”

Looking eastward, Hitler's empire was to be in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. His goal was the unification of all German-speaking people into one great nation showcased by his created populace of tall, blond, blueeyed, athletically fit Aryans. He wished to eliminate the weak and the medically handicapped, and to racially cleanse the continent. If Hitler were not Hitler, this short, dark-haired man just might have had himself gassed.

His astonishing cunning and deceit in fabricating and justifying his actions allowed him to successfully begin taking control. Der Führer was closing his fist and continuing to force expansion, first to Austria, then Czechoslovakia; eventually Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France would join the long list. With unsuspecting Poland about to be the third recipient of the Nazi's crushing boot, Great Britain and France rose to meet their destiny and declared war on Germany on Sept. 3, 1939. World War II had begun.

In the United States the people favored neutrality. Recovering from the First World War, the democracies of the world craved peace and thus were totally unprepared militarily. As Americans followed the early march of German occupation as it steadfastly bulled forward, they began getting nervous. Gingerly they started the buildup of their own limited military resources.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had first called on the US to supply the Allies with badly needed materials. But now the US focus began to turn homeward. Factories converted from sewing machines to machineguns. As America's men flocked to the armed forces, America's women left the comfort of their homes to step into the vacated places in the plants. Officials soon discovered that women could solidly perform the duties of 8 out of every 10 jobs normally done by men.

Meanwhile, the German armies took on the Big Bear of Russia, who slashed back savagely through its icy weather. With no winter clothing and vehicles ill-designed for such a severe and punishing climate, Hitler's soldiers were crippled and freezing in Moscow's bottom-dwelling temperatures of twenty to fifty below zero.

As the Germans failed in their attempt to capture that capital, Japan suddenly pushed the US into the conflict with its staggering assault on the unaware and unprepared American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The base, attending its daily duties on that island of pineapples and leis, was stunningly dive-bombed by 353 Japanese aircraft. Four US Navy battleships were sunk and four others were damaged, as well as three cruisers, three destroyers, an anti-aircraft training ship, and one minelayer. 2,402 men were killed and another 1,282 wounded.

The shock to the American people was profound. The following day, Dec. 7, 1941, the day President FDR would later refer to as “a date which will live in infamy,” the US declared war on Japan.

FDR called for the immediate and massive expansion of the armed forces. The 20 years of neglect and indifference could not be overcome in a few days. US industry staggered and strained to support its nation's allies with equipment as well as, now, providing for its own military expansion. And American young men and women stepped up to the plate.

When his National Guard Field Artillery Regiment was called to active duty in 1940, George left boyhood behind. Military schooling, advanced pilot training, which included a crash with his instructor that landed him in the hospital for three weeks, and assignments followed. On October 6, 1943 George boarded the Empress of Scotland (the old Empress of Japan) and the following day at 11:40 A.M. this homegrown young man sailed into the unknown. Eight days later they docked at Casablanca, French Morocco and another eight days found him in Algeria, Sicily, Italy, Sicily again, then Italy again. George was transforming from country boy to warrior jet setter.

George's maiden mission was plotted; the assigned drab-green B-25 standing by on the airstrip was primed and heavy with its fearsome bombs loaded, and George's whole being keenly revved in high gear. However . . .

MISSION #1: OCT. 26, 1943

Bomb the town of Terracina, West Coast of Italy.

Oct. 27 Bad weather — mission cancelled.

Oct. 28 Bad weather — mission cancelled.

Oct. 29 Bad weather — mission cancelled.

Oct. 3 0 Bad weather — mission cancelled.

Oct. 31 24 B-25s & Kitty Hawk (P-40s) Fighters. Was #2 in 3rd box of airplanes. After flying to initial point, was called off due to weather. Target had been harbor at Ancona, East Coast of Italy.

Slow, very slow, start . . . . By his fourth mission, however, he had a taste of how his future was going to unfold:

MISSION #4: NOV. 12, 1943

To a Tatoi Airport, Athens, Greece — 48 airplanes from 340th & 48 from 321st & 36 from 310 th, 82nd fighter Wing for support — P-38s, P-39s, P-40s & Spitfires. Never saw so many planes in the air at one time. Weather stopped us from going to original target. Started a run on alternate target on airport at Berat, Albania. The Jerries (Germans) put up flak so thick you could have played baseball on it. All of the oldflyers said it was the most ack-ack they had ever seen. Enemy fighters were diving down on gun crews. The other squadrons dropped their bombs but we couldn't get near the target. As yet I don't know whether we got credit for the mission or not. Had 12 frog (smaller) bombs per plane. Finally got credit for mission.

In June of 1944, somewhat older and infinitely wiser, now battle-accomplished George was moved up to the US Army Air Corps’ 340th Bomb Group based on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, a picturesque region of France. Here, on its airfield that had been scraped out of a briarroot patch parallel to the pristine, water-caressed shore, was where he was to remain until war's end.

This bomb group, the notorious “Unlucky 340th,” was where eventually crossed the paths of Capt. George L. Wells (Captain Wren), Col. Willis F. Chapman (Colonel Cathcart), General Robert D. Knapp (General Dreedle), Lt. Joseph Heller (Yossarian) and other men soon to be immortalized in literature. Here, in this bomb group, was where events began to unfold that would eventually thread their way through the pages of Catch-22.

George had collected five months of hard-earned experience before Col. Chapman took command of the 340th, which was then based at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius in Pompeii, Italy. The original sculptors of this airfield had been British engineers who had whittled it out of a lush grape vineyard.

MISSION #50: MARCH 20, 1944

Led Sqd. flight on target at Perugia, but bad weather made us turn and bomb alternate at Terni. Vesuvius is really acting up and lava is running down the sides of the mountain.

With disbelief and great curiosity, Chapman arrived just in time to experience one very rare and very mammoth volcanic eruption as it hurled and spewed its molten guts directly over their airfield. The thundering, sky-splitting explosion proceeded to bury everyone and everything under a foot and a half of black, basketball-sized rock, clinkers, and ash. It was as if Vesuvius the Magnificent had just been waiting to display its awesomeness. The force of its punch was of such magnitude that bombs and flak seemed the merest of play toys by comparison.

Two months later Joseph Heller arrived, perhaps grateful to miss this scarring event that he would have relished.

Both George and Joe were assigned to the 488th squadron, one of four under Chapman's command. The 340th, in turn, was one of four groups under the leadership of General Knapp, a commander whose military career already had included World War I.

By this time, George Wells knew war. He knew the routine of rising in the early dark of pre-dawn to fill a basin with cold water, wash, shave, and down a cup of coffee with bread, all before hurrying off to the briefing room prior to flying another mission. He knew the sharp metallic crack of the truck tailgate dropping, rattling and clanking open to deposit the officers it had transported from that briefing's coffee to the airstrip in front of a waiting B-25, which, like its crew, had been warmed up. And he knew, as he knew his own heartbeat, the sound, the sight, and the smell of that plane: that B-25 that was both dreaded as the deliverer to death's door, trusted as their dearest friend under unforgiving fire, and worshipped, often as wounded as they were, as their sole means of a safe return home.

Now, so many years later, George also knows every page of Catch-22. Author Joseph Heller's ultimately classic novel (confuting Mark Twain's definition of “a book which people praise but don't read”) was born of those circumstances and took on a life of its own. George quickly recognized this book was his group's life, his life. And, as the pages turned, he vacillated between clenched teeth and an insuppressible grin. This book belongs to the world but, more importantly, it belongs to him and his wartime buddies.

At the opening of the irreverent and farcical Catch-22, Heller sets the stage.

“The island of Pianosa lies in the Mediterranean Sea eight miles south of Elba. It is very small and obviously could not accommodate all of the actions described.” (Catch-22, p. 6)

Almost spot-on. The actual setting for this tale was a mere thirty-four miles southwest of Pianosa on the exquisite island of Corsica. This island with its wild and jagged mountains, its deep, shadow-covered valleys, and its clear, cool mountain streams was formed through volcanic explosions and, while it was geographically closer to Italy, it was a region belonging to France. The island enjoyed a heritage of the temperate climate of the Mediterranean. The days of its coastal summers were hot and dry while slowly arriving winters eased in pleasantly mild and rainy relief, frequently evolving into heavy rainstorms. In spite of its very turbulent past, Corsica seemed created to be a place to enjoy life as pristine, clear waters gently lapped its eastern coastline. This was not a place to be touched by war. But here was where George, Joe, their 340th Bomb Group, and 16 other United States military airfields were located.

The Italian island of Pianosa and the French island of Corsica.

The umbrella 57th Bomb Wing was moved here in April 1944 to give their planes solid striking power at targets farther north. These all were tactical bomber groups whose focuses were Axis positions, resources, and supply lines across those pristine waters in Italy. It was here that all of the action of Catch-22 could take place and here that all the factual action of Heller's Bomb Group did take place.

George's memories are keen as he relates:

Other than placing the Group on that small island, I find the setting very factual. All places mentioned — countries, islands, towns, cities, etc. — are actual places and they did play a part in our group's history. I found no place mentioned that did not. Even the location of targets and the types of targets for those locations are both correct for targets hit by the Group. There is no doubt in my mind that Heller took actual events and actual people to write his story. I think he varied the people used for a particular event on occasion, as well as split some people into two different characters. He uses names at certain times, which are very close to a real person who actually did the thing mentioned. He has also incorporated some events, which took place before he arrived but that he became aware of by word of mouth.

George had become a seasoned warrior by the time he encountered Joe Heller, who was a combat replacement, fresh, eager and, yes, naïve. George, 5’7” and just 24 years old, flew his first combat mission on October 26, 1943, mere months before 5'11 ½” and just 21-year-old Lt. Heller arrived in the Group. But those few months were a lifetime in terms of experience. While each barely knew the other, still they shared, for a momentous period of time, a history together. They shared the adjustment of going from a life of the familiar — family, friends, ball games, the life of the American boy on American turf — to the unfamiliar of guns, war planes, death, and responsibilities not for your friend's missed homework assignment, but for your friend's very fragile life in a very foreign place.

As a pilot, George was keenly aware that he shouldered the lion's share of responsibility for the safety of his entire crew. It was for him to decide the critical timing of almost every movement of his aircraft which affected, as well, the following five formation-flying B-25s in his box of six. It was for him to keep vigilant, use his every left-seat skill to evade gunfire and flak, and demand of his aircraft instant evasive maneuvers after “Bombs Away!” His was the decision, when his plane was riddled and crippled from the accuracy of the anti-aircraft guns manned by the tense and sweating hands of the German foe so far below them, whether his men should bail out with all of the risks that entailed or whether he should risk their lives further by struggling to bring his mortally wounded plane safely home.

Joe also wore a heavy cloak of responsibility. As a bombardier he learned to steel his nerves. This was not a position for the timid. As he sat in his exposed Plexiglas nose cone, in front of, and isolated from, the rest of the crew, he had to focus, with a singularity, on one paramount pinpoint target. When the B-25 made its final turn and veered toward this target, it was Joe, as bombardier, who took complete control and called the shots. Nothing was to distract from his tunnel vision of guiding that aircraft over the target. His bible was the continually drifting cross hairs on his gauge. His sole focus was to accurately drop his bombs on a tiny speck of an objective some hundreds of miles away. If shells were exploding around him and death-dealing flak was ripping through his aircraft's skin, he must not be distracted. The entire crew knew that should they — should Joe, in fact — miss their target, they would be assigned to return on the following day to complete it, this time under even more dire conditions, since the enemy below had been alerted and would be waiting. It was every man's most urgent prayer that the bombs would drop with accuracy and their aircraft could instantly bounce up free of their weight, bank, climb to safety . . . and head home. As Joe glued himself to his bombsight, their lives were put on hold.

Joe Heller's and George Well's wartime experience centered on their crewmates, their leaders, their aircraft, and their surroundings. The island of Corsica was the hub of their universe. Their group was comprised of four squadrons: the 486th, 487th, 488th, and 489th. Heller, Wells, and most, but not all, of the men who surface in some form in Catch-22 were part of the 488th. To better understand the genesis of Catch-22, a very brief history lesson of the 340th Bomb Group and its aircraft is needed.

As the warhorse Bucephalus was to the great Alexander, so the beloved B-25 Mitchell medium bomber was to the 340th Bomb Group. It was the protector of every crewmember who boarded her. The crew bonded tightly with her. They named her Oh! Daddy!, Briefing Time, Poopsie, Black Jack, Jersey Bounce, Kick Their Axis, Vesuvianna, That's All-Brother, Battlin’ Betty, etc. and credited her every accomplishment with small bombs (or in Poopsie's case, small puppies) painted, like Wild West notches on a pistol butt, on her fuselage. They loved and honored her, for she could sustain tremendous damage and still be able to limp home to safety with her cherished crew.

This B-25 was the ideal aircraft for medium altitude daytime attacks on specific targets. The high percentage of pinpoint bombing accuracy maintained by the 340th, 310th, 319th, and 321st Bomb Groups resulted in flying sorties on precisely chosen tactical targets that the higher flying heavy bombardment groups had not succeeded in knocking out. The average lower bombing altitude of from 7,000 to 12,000 feet insured a markedly increased degree of accuracy, but also brought the B-25 into the deadly range of the highly respected and effective German 88mm cannon.

This high-velocity gun was Germany's main defensive weapon against the bombers. The 8.8cm Fliegerabwehrkanone, shortened to Flak, fired a 20.34-pound shell to over 49,000 feet. The weapon was evolved to combat the fact that to hit a moving aircraft flying about 200 MPH at an altitude of one or two miles with a shell was exceedingly difficult. This weapon was designed to fire ahead of the formation and was timed to explode when the planes reached that spot. The explosion would rocket hundreds of slashing, iron shards in all directions. Since the artillery man would have to guess at the altitude of the formation, the cannon shells contained a timer that would allow him to set them to go off at, for example 5,000 feet, or 5,500 feet, and so on. That is why pilots originally employed severe evasive maneuvers, for it kept those feared gunners below guessing as to where to aim their next volley. True to life, Murphy's 10th Military Law states, “Never worry about a bullet with your name on it. Instead worry about shrapnel addressed, ‘Occupant’.”

Heller's descriptions in Catch-22 of the wildly erratic evasive flying maneuvers of Yossarian were wholly accurate in the initial bomb runs. George's personal descriptions attest to that. Knowing they had a deadly gauntlet to run, he had to keep razor alert for the upward snake of smoke trails signifying incoming ack-ack, that dreaded anti-aircraft gunfire. Instantly reacting to this sight, he would roll his aircraft first to the right, then left, up, and then down until within about one-half mile of the target. Then for the next five to ten seconds he would fly unwaveringly straight, his men in gripping focus, tense, alert, with pulses racing and breathing halted, to hit the target. This was the most dangerous time. The bombs would drop and immediately the planes left the target. The remaining five B-25s in this box of six aircraft would be following suit.

While the 340th had a wide variety of targets (airfields, railroads, bridges, road junctions, supply depots, gun emplacements, troop concentrations, marshalling yards, and factories) it was the Brenner Pass, a narrow mountain pass through the magnificent jutting Alps along the border between Italy and Austria, that was their greatest challenge.

Historically this pass was always of strategic importance. At 4,495 feet it was the lowest of the major alpine passes, as well as one of the few in the area. During World War II the Alps impeded the German infantry that was being pushed by the Allies, from reaching the safety of Austria. The only way to cross the Alps was through this mountain pass at Brenner. As well, the pass was the route used by the Germans to funnel supplies down from Austria to their ground troops in Italy. Because of the importance of this pass, the Germans kept it heavily armed with artillery of all kinds.

In November of 1944 the medium bombers were given their most daunting test, one they accomplished with amazing success. It was known as the Battle of the Brenner, an intense focus on this critical rail line between Germany and the Italian battlefront. Targets, ranging into Austria, were the railroad bridges, tunnel entrances, or replacement troop or supply concentrations.

Typically an alpine mission would unfold as follows. The designated target might be the marshalling yards outside the city of Trento. The attack was planned so the bomb drop could be made at high noon. This timing was essential since, for visual bombing, the target must be well seen, and only during the noon hour does the sun shine on the floor of the Brenner Pass. The surrounding high mountains cast their deep, dark shadows during any other period of the day.

The sortie would be accomplished at an altitude of from 100 to 300 feet above the mountain peaks, coming in over the pass, turning immediately on the IP,1 and making the bomb run up the Brenner. Naturally the Axis forces soon recognized this and prepared their defenses along those lines — even to the extent, as it was later learned, of scheduling earlier lunch hours. Obscuring smudge pots were kept burning from 1100 hours each day in strategic areas. In addition, the fierce 88mm anti-aircraft guns were transferred from the floor of the valley to positions high on the mountainside where they could actually fire down upon B-25s that swooped through the pass at low level.

MISSION #95: DEC. 22, 1944

Formation Commander with 489th on target at Lavis on the Brenner Pass line.

Ran into lots of ack-ack and picked up quite a few holes. Really was a cold ride for four and a half hours.

On rare occasions the medium bomber groups were afforded the luxury of anti-flak fighters assigned to attack these enemy gun positions, thereby greatly increasing the odds of US bombing success and safety.

The increasing accuracy of German gunners also led the medium groups to devise their own means of defense against the anti-aircraft fire. For example, the creative use of chaff, strips of metal foil released in the atmosphere from aircraft to confuse radar-tracking missiles or obstruct radar detection, was implemented. Eventually, three to six B-25s were loaded with verboten phosphorous bombs in advance of the main bomb group, with the enemy gun positions as their targets. This ever-increasing determination and creativity reaped rewards.

The B-25s operated during the entire winter months of 1944 from the island of Corsica. This winter was not to be taken lightly at altitude. Mother Nature may have railed against man's weakness for wars by trying to clear her skies with icy, finger-freezing, mind-numbing cold, to which George's 98th mission attests (see page 32).

The B-25s had no heaters so, in the manner of iconic comic illustrator Charles Schultz's Charlie Brown, men layered heavily before venturing up. Had Hitler read and heeded Der Peanuts, perhaps Moscow, in those earlier days, would have been rechristened Hitlersburg.

Victor J. Hancock, of the 445th squadron, describes, in the winter 2010 issue of Men of the 57th, the crew's couture:

First on were your boxers followed by wool long johns. Over those would be the wool trousers, wool shirt and wool sweater. Pull a wool beanie over your head. Silk socks, regular socks, then wool socks. On with fleece-lined pants. Placed over those were combat boots that were placed inside fleece-lined boots. Then they pulled on a flight jacket, over that a heavy leather fleece-lined jacket and on their head a fleece-lined helmet. Hands were covered with silk gloves, over which they placed leather gloves over which they then placed fleece-lined leather gloves.

Now just try to pull out a tissue.

From this Corsican island, in the months of summer, the assault that opened the front in southern France was conducted.

MISSION #68: JUNE 29TH

Flew Formation Commander with 488th Sqd. Target railroad bridge at Cervo, Italy.

I got my first look at French soil today because the target was very close to France. It looks as though we'll soon be working on Southern France.

On D-Day for Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France, it was the B-25 units that were assigned the low-level attack on enemy concentrations. In this type of operation it was not an unusual occurrence for bombs from the higher-flying heavy US bombers to rain down on the B-25 formation. (As George ducked on Valentine's Day, February 14, 1944, “We nearly had bomb hit us.”)

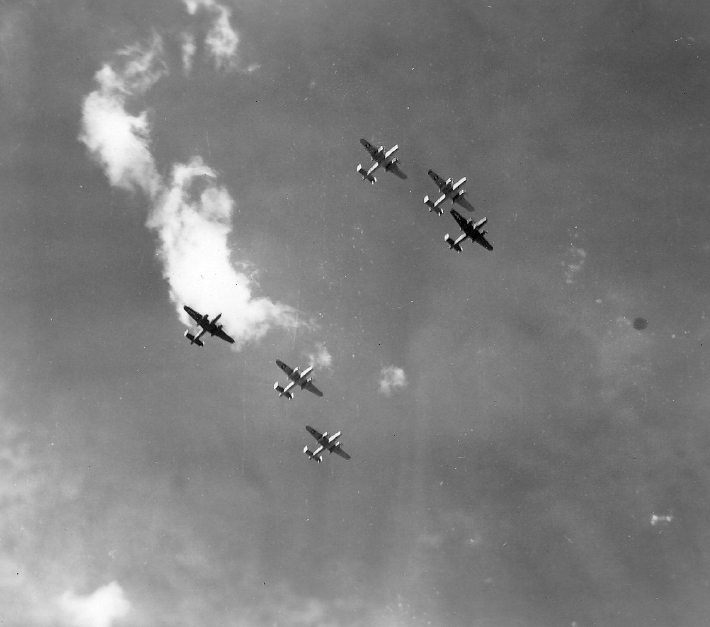

The B-25 group's four squadrons each maintained approximately fifteen assigned aircraft. A normal mission involving the entire group consisted of three participating squadrons, each squadron providing twelve aircraft. The standard formation was boxes of six aircraft in two, tight V formations, the back three dropping a plane's depth below the fore three for visual purposes. Grouping aircraft in this manner provided the most effective defense against enemy fighters by the concentration of firepower.

This same box formation was held throughout the bombing run, five of the aircraft dropping off the lead ship. The lead aircraft in each box was generally the only aircraft containing a bombsight; release of the bombs in the remaining five aircraft was either by visual toggling or radio signal release. The usual armament of a B-25J was four fixed .50 caliber machine guns firing forward, one flexible .50 in the nose, twin .50s in the top turret, two .50s in the waist, and twin .50s in the tail, the stinger.

Each ship carried a crew that consisted of a pilot, copilot, bombardier, turret gunner, radio operator/waist gunner, and tail gunner. The dominant lead ship in each formation bore, as an additional crewmember, a navigator. It was the last ship that generally also carried an additional crewmember, a photographer to document the mission's success or failure.

The pilot, copilot, and bombardier/navigator were officers, while the gunners were enlisted men; each was a critical piece of the puzzle. From front to back, first came the bombardier snugged in the nose of the plane. Above and behind the nose sat the pilot and copilot who, while flying the plane, were continually straining to avoid barrages of flak, simultaneously firing the forward facing guns. The navigator, usually behind the pilot and copilot, was in constant communication with the bombardier. The navigator's job was to guide the plane toward the target, while the bombardier had to release the bombs with flawless timing for a successful mission. In the body of the plane were the bomb bay and the radio compartment. Stationed here were the radio operator and engineer, who both did dual duty as waist gunner and turret gunner. Farther back rode the more isolated tail gunner. At take-off this man would not be in the tail gun turret, but instead would be closer to the body of the plane so that his extra weight would not affect the B-25's sensitive aerodynamics as it lifted off the runway.

On Sunday, January 21, 1945, an accident happened in the Brenner Pass. Because of brutal air turbulence, B-25 formations on a mission were bouncing around violently with great fluctuations in altitude by each of the planes. Two runs on the target and they still could not drop. On the third run, battling both heavy flak and fierce air gusts, the propeller of aircraft 8U, piloted by 1st Lt. William Y Simpson, struck the tail gunner's compartment of aircraft 8P containing S/Sgt. Aubrey B. Porter. Porter was actually cut out of the tail by the prop.

Radio-gunner Jerry Rosenthal, of the 488th, gave the following account: “Porter fell through space without a chute. His chute and part of the 8U's wing came by our tail. The whole thing just missed us . . .” Simpson's plane went down over the target. The pilots of the severely crippled 8P pulled an “aerodynamic miracle” when they eventually were able to safely land their B-25 minus more than half of its tail. And, tragically, its tail gunner. Aubrey B. Porter was never found.

B-25, 8P, missing half of its tail and its tail gunner.

In Catch-22, Heller describes this collision between the two aircraft on a mission. Young pilot, William Simpson, is immortalized as “Kid Sampson.”

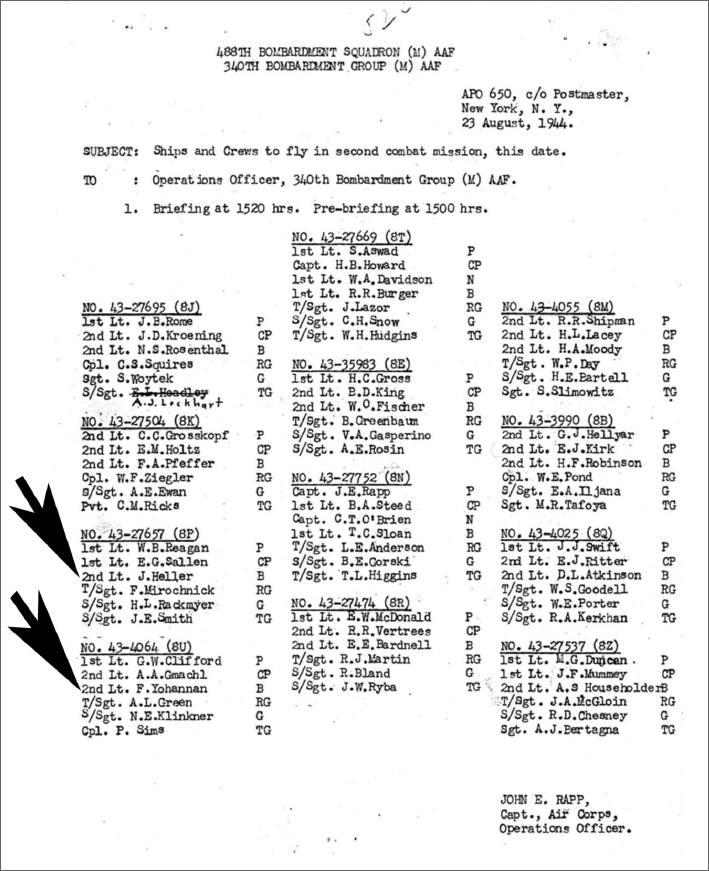

Following is a flight schedule from this same 488th Bomb Squadron for an earlier mission on August 23, 1944 in which the same two aircraft, 8U and 8P, were participating. 8P had 2nd Lt. Joseph Heller as bombardier and 8U carried 2nd Lt. Frances Yohannan, also bombardier, whose name was the inspiration for the name of Catch-22's main character, Yossarian. Aircraft 8U and 8P were flying adjacent to each other in the box just as they were on that fateful Sunday. Only fate decided which day, which people.

Combat mission includes Heller and Yohannon.

As George's crew lifted off for yet another mission, they knew the routine. This mission, from Corsica to the Brenner Pass, was to last approximately 3½ hours. Their aircraft labored with its bomb load of about 5,000 lbs. They threaded their way around known anti-aircraft gun positions trying to avert the piñata-like attacks of those fearful weapons. The sounds had become unwillingly familiar. The staccato ack-ack fire from ground installations was of two types over this target: barrage coming in, and tracking going out. A sudden stop in firing indicated enemy fighters closing in2 and every man aboard would suck in his breath as he frantically scanned the sky for sight of the lethal and rapidly approaching, but still faceless, enemy.

Upon his return to home base, George would pull out his small, black mission book and dependably log each of his 102 missions. This soft and functional diary with white, lined pages measured about 3x4 inches and easily slipped into his shirt pocket. The entries were brief and devoid of emotion. “Mission #57: May 16, 1944. Led my Sqd. Flight on Port of Piombino. Lots of flak but we dove around it and only got two holes.” These daily-abbreviated entries fleshed out the true story of a pilot's circumstances. Entries would show, curiously, how sometimes the most difficult missions were the least storied.

98th Mission — Jan. 28th. Flight leader with 488th on R/R Bridge at Roverto, Italy lots of flak and this was the hardest mission I've had to date due to cold and no oxygen.”

Mission entries record how he flew even when he was very sick from the liver ailment, yellow jaundice.

MISSION #14: DEC. 5TH

Was very sick butflew anyway. Co-pilot for Dean on raid to Aguilla. Bad weather made us bring our bombs back but ran into a lot of ack-ack on coast. Couldn't get left engine out of high blower.

Faithfully, he penned in his mission entry. He flew, as well, when his plane was very sick, returning from one mission with 33 holes in it.

Flew as leader of 2nd element on Pontercorvo Bridge, Italy. My plane had 15 holes in it, seven of which were in the right engine nacelle (cover). The left engine was hit and leaking oil. The right main gear tire had been hit and blown out leaving me with no tire or brakes for the right wheel. Other hits in wing and bombarding compartment. I made a good approach to landing but after I touched the ground, I had my hands full. When I finally got the plane stopped, we were facing the opposite direction! The group lost 2 ships on raid.

I've been sick with yellow jaundice for the past week. Just found out that my plane had 33 holes in the raid on the 14th. The hydraulic system was shot out in the right nacelle.

Again, penning his entry. He flew under conditions that left every plane in his flight suffering from direct hits. The entry was recorded. He flew sick or well, in good weather or bad, occasionally returning from one mission then taking off for another, and occasionally a third that same day. Settled in his tent in the quieting evening hours, he would routinely thumb open his book and, in that very meager space, record those missions.

MISSION #9: NOV. 29TH

Flew copilotfor E. J. Smith. Supposed to bomb Terni but weather kept us from seeing the target. Then weflew to east Coast, we bombed Giulianova, Italy. Bombed bridges and marshallingyards. Ran into a lot of flak as we came off the target. Must have been 105mm because they didn't fire straight up. 33 B-25s unescorted.

MISSION #10: DEC. 1, 1943 — WITH R.M. JOHNSTON

Enemy positions near Casino, Italy. Took off in morning but called back on account of weather. Take off again in afternoon. Johnston couldn't stay in formation and went over target by ourselves! 5,000 lbs of bombs. Did not get credit for mission because bombs were not dropped. Johnston had to go around on coming in for landing. Later got credit. Dec. 3rd.

George, of humble beginnings and unsurpassed optimism, had become the ideal pilot. While his smaller, strong frame fit well in the confines of the B-25, and his talent was patent, it was his mental outlook that was invaluable. Never did he doubt he would return home once the war ended and that unshakable belief blessed him that most rare of gifts: freedom from fear.

We [he and Fred Dyer, Catch-22's Capts. Pilchard and Wren] both did like to fly a lot and we became better by flying more. Dyer and I would go up and fly on each other's wing many times on stand-down days or when we weren't on a mission. We would fly in heavy weather conditions in formation — practice single-engine in formation. We flew the planes in practice under various conditions to fully understand its performance as well as its limitations.

MISSION #101: MARCH 13, 1945

Formation Commander with 488th on Aldeno R/R. Fill in the Brenner Line. Had lots of flak and had an oil line hit in the right engine and had to go on single engine over the target. We had to drop out of formation but we managed to get back OK. This was the 1st medium bomber that has ever returned from the Brenner Line on single engine. We were on single engine for 2 hours. We were able to hold it at around 6,500ft. We were shot at again crossing the Po Valley by 40 and 20 mm. We then had a hard time getting over the mountains between Po Valley and the coast.

We really set the tone for combat in the 340th. What we both did was to tend to eliminate the basis for bellyaching by the combat crews due to any concern over the B-25's performance even when heavily damaged or due to fear for one's self while in combat. We flew additional missions without having to, never picking one because it was considered a milk run. In fact, we did the opposite. The more challenging, the more we competed with each other. We were the best of friends. I used to call him “Fearless ‘Freddie’ Fosdick” after the Dick Tracy comic strip character.

Fred's love of flying combined with a curious and adventurous nature to produce a story — a very short — story.

While I was stationed at Comiso, Sicily, a pile of wrecked remains of over one hundred Me. 109s was discovered. One had been flown by the German ace Molders. His plane had over twenty swastikas painted on the fuselage (Note: Werner Molders was the first pilot in aviation history to claim 100 aerial victories. It paid to be born “Allied” rather than “Axis.” The Luftwaffe, during WWII, far outstripped allied fighters in numbers of recorded kills because of their “fly till you die” policy rather than being rotated elsewhere after a certain number of missions had been completed.) I and two others put a couple of these airplanes back together and flew them. The Me. 109 had a narrow landing gear, which was (according to German sources) notoriously weak. The second time I flew mine, all did not go well. The fact that the oil pressure was calibrated in kilograms/cm. instead of lbs./in. was confusing. On attempting to land, one of the main gears wouldn't go down so, after flying around trying to shake it loose, I eventually landed on one gear and a wing amid a great cloud of dust.

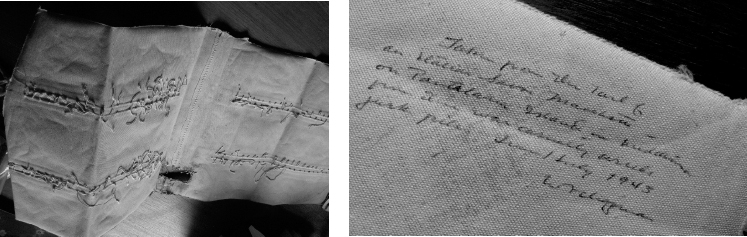

Left: Author's son, Jason, holding skin from 1943 wrecked italian aircraft, 2010.

Below: Coarsely stitched underside of Italian aircraft fabric skin. In the upper corner Bill had written in ink: “Taken from the tail of an Italian Siai Marchetti on Pantilaria Island in Mediterranean from the war casuality wrecks junk pile. June/July 1943. — W.F. Chapman”

We eventually rebuilt the plane and, on the move to Catnip, Sicily, I asked an ex-RAF pilot to fly it to Catania for me. On take-off, he forgot to latch the canopy, which blew open; he ground-looped the plane, wiped out the landing gear, and that was the end of that.3

Pure and simple, both men loved to fly. And Joe, on the sidelines, nimbly massaged George and Fred into Catch-22's very identifiable, quiet and capable Piltchard and Wren. Both men felt, as they trained younger pilots, that men who tell other men how to fight should fight alongside them, as well.

After his historic 102nd mission, Fred, pilot extraordinaire and war-ripened at age 29, was firmly ordered to return home. He had survived three engine losses in combat, uncountable ack-ack holes, a shot-out windshield that resulted in a head wound, and, ultimately, had been shot down, parachuting from a fire-encased aircraft only after ensuring all crew members had safely donned parachutes and jumped first. Bad fortune dropped him in the midst of a tank battle, from which good fortune allowed a rescue by British soldiers.

Fred reflects:

Every mission had its distinct personality or ambiance, so to speak. I think that one has to admit that all were fraught with trepidation. Some had their moments, though; like the time we were returning from a night mission over Battipaglia, Italy; the moon was shining and we could see Stromboli down in the dark waters of the Mediterranean. If German night fighters didn't show up, you had it made. At other times when a mission returned to home base, the formation went into an echelon for landing. Each airplane peeled off at three-second intervals. If you made it this far, the rest was easy; this was a great moment.

Return home he did, probably with an audible sigh, for it was with great reluctance. “I just hate to see this show going on without me in it.”

Go home, they said. That's it. That's enough.

George, too, was ordered home, but his leave was for a 30-day rest.

MISSION #102: COMMAND PILOT WITH 489TH ON MARCH 19TH, 1945

This was the Group's 800th mission. The target was a R/R Bridge at Muhldorf Austria. This should be the last mission I'll fly before going home for a thirty-day leave.

Frederick Wolfin Dyer, Jr., with a chest full of medals attesting to his bravery, skill, and experiences, remained in the Air Force, rising to the rank of colonel while continuously flying all manner of aircraft. This native Coloradan retired after thirty years’ service, having accumulated about 10,000 flying hours. He bought, operated, and eventually sold a successful transmission repair franchise with his eldest son. Then he moved on to the machine design and antique car restoration business. At age 80, three years before he died, Fred and one of his sons climbed Mount Revenue, a 13,000 foot peak twelve miles east of Montezuma. “This guy did not do senior citizen,” his son said. “He just never got there.”

The Box of Six: standard flying formation.