It is from the truths, the facts, and the solid ground of life that Catch-22 sprouted. And while, under Joseph Heller's masterful touch, great fiction blossomed, still this fact/fiction dependent relationship is undeniable. The following pages show how these forces play with and against each other.

The characters of Catch-22 are strong and unique and independent, but many of them owe the seeds of their very existence to the also strong and unique and independent men of the 340th Bomb Group.

Now, introductions are necessary . . .

“. . . when Yossarian climbed down the few steps of his plane naked, in a state of utter shock, with Snowden smeared abundantly all over his bare heels and toes, knees, arms and fingers, and pointed inside wordl essly . . .” (p. 225)

“Yossarian was a lead bombardier who had been demoted because he no longer gave a damn whether he missed or not. He had decided to live forever or die in the attempt, and his only mission each time he went up was to come down alive.” (p. 29)

DECORATIONS

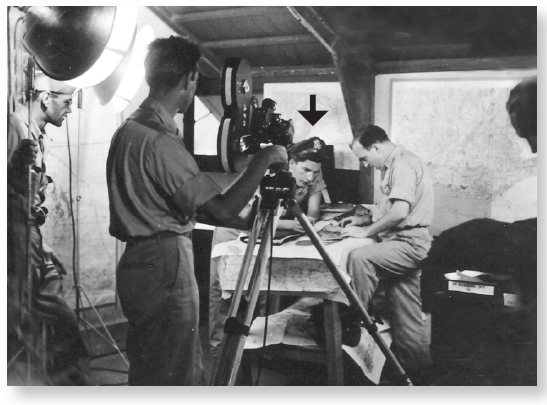

Heller with 9th Combat Camera crew.

THE TRUE STORY • BY ROBERT D. KNAPP

“One warm evening I decided to take a spin—we were encouraged to fly as often as possible. Well, I took off, carelessly forgetting to check the gasoline tank. Airborne, I tried a few figure eights and rolls when suddenly I spotted an airplane in the river below me, with its tail sticking up above the water. I circled around looking for the pilot, and then I spotted him with his head on the side of the cockpit, obviously in pain.

I was about to head back to the base to report the accident when suddenly I ran out of gas! I went into a stall and spun into the river right along side the other plane. Fortunately I was not injured seriously. I suffered a broken nose and few facial body cuts, but no major damages. I managed to get out of my plane and wade over to the other pilot whose name was Kennedy, a man who shared my hanger. I pulled him out of his plane and carried him to a nearby road where I hailed a passing car. Our Good Samaritan drove us to the city hospital.

In a few weeks, we completed our courses and were commissioned as 2nd Lt's. Getting those wings had to be one of my proudest moments.”

— Fly Low and Slow, Robert: The Men of the 57th (1979)

DECORATIONS

|

|

“General Dreedle had wasted too much of his time in the Army doing his job well, and now it was too late.” (p. 212)

“. . . Yossarian . . . taking off all his clothes after the Avignon mission . . . right up to the day General Dreedle stepped up to pin a medal on him.” (p. 99)

“General Dreedle's nurse was chubby, short, and blond. She had plump dimpled cheeks, happy blue eyes, and neat curly turned-up hair. She smiled at everyone and never spoke at all unless she was spoken to. Her bosom was lush and her complex i on clear. She was irresistible, and men edged away from her carefully . . . She was succulent, sweet, docile and dumb, and she drove everyone crazy but General Dreedle.” (p-213)

THE TRUE STORY • BY BILL CHAPMAN

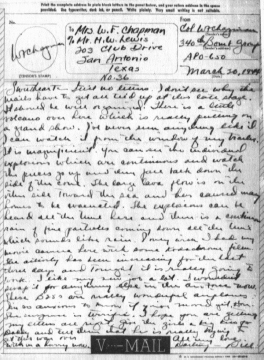

“I assumed command of the 340th Bomb Group, flying B-25 Mitchell Bombers on 16 March 1944. Five days later I faced quite a shock. The best firsthand description is in the following V-Mail letter to my wife:

March 20, 1944: Sweetheart—Still no letters. I don't know why the mails have to get all tied up at this late stage. It should be well organized. There is a little volcano over here which is putting on a grand show. I've never seen anything like it. I can watch it from the window of my trailer. It is magnificent. You can see the individual explosions which are continuous and watch the pieces go up and then fall back down the side of the cove. The large lava flow is on the other side toward the sea and has caused many homes to be evacuated. The explosions can be heard all the time here and there is a continuous rain of fine particles coming down all the time which sounds like rain. I only wish I had my movie camera here with some Kodachrome film. The activity has been increasing for the last three days and tonight it is really going to work. I like my new job a lot. I wouldn't swap it for anything else in the Air Force now. These B-2Ss are really wonderful airplanes. I'm anxious to know if you've moved yet, Hon. The suspense is terrific. I hope you are getting my letters all right. Give the girls a big kiss for Daddy and tell them that he is really trying to get this over with in a hurry now. All my love, Darling—Bill.

The shock came about 5:30PM on 21 March when Mt. Vesuvius erupted violently 15-20,000 feet high. The wind from the northwest blew hot ash and debris over our airdrome (Pompeii) covering everything to a depth of 18-20 inches. It crazed the plexiglas in the aircraft canopies, ruined the canvas control surface and dented some of the metal surfaces, making all eighty-seven B-25s unflyable. The men were not certain if they would be mummified by morning or not. We started evacuation to Guendo, near Salerno, on the 22nd.”

“Colonel Cathcart had courage and never hesitated to volunteer his men for any target available. No target was too dangerous for his group to attack.” (p. 55)

“Colonel Cathcart was infused with the democratic spirit: he believed that all men were created equal, and he therefore spurned all men outside Group Headquarters with equal fervor. Nevertheless, he believed in his men. As he told them frequently in the briefing room, he believed they were at least ten missions better than any other outfit and felt that any one who did not share this confidence he had placed in them could get the hell out. The only way they could get the hell out, though, as Yossarian learned . . . was by flying the extra ten missions.” (p. 57)

“Colonel Cathcart was conceited because he was a full colonel with a combat command at the age of only thirty-six; and Colonel Cathcart was dejected because although he was already thirty-six he was still only a full colonel.” (p. 185)

DECORATIONS

|

|

Chapman in the pilot seat of a B-25—note cigarette holder.

Chapman receiving Distinguished Flying Cross from General Knapp

THE TRUE STORY • BY JIM COOPER

“On August 24, 1979, exactly 1900 years had passed since Vesuvius blew up with what is now known as the most destructive eruption in recorded history. The city of Pompeii, Italy, near the bay of Naples, disappeared completely. It is almost impossible for us to imagine the horror and panic of such a catastrophe. Yet there are many Air Force service men from World War II who have a very good idea of the lethal power of Vesuvius!

It all began quietly enough in March 1944. Our Bomb Group, the 340th, and other Air Force groups were stationed around the base of Vesuvius, engaging in bombing Italy. Our airfield, near Pompeii, was bulldozed out of the lava and ash deposited 19 centuries before. Pilots returning from missions day or night could easily find our airstrip by locating Vesuvius! In daylight the white wisps of smoke rising from its cone, and a red glow at night from the crater, made an easy landmark.

Two other officers and I drove a jeep up the mountain as far as the road went. We then walked to the top. The terrain was rough and quite ugly. We were amazed at the raw, jagged and awesome appearance of the volcano's cone. From fissures, a slow bubbling red flow of lava, while not threatening, persisted slowly toward the outer rim.

A few enterprising native children were dipping out small globs of lava on sticks, pressing small Italian coins into the soft but quickly hardening liquid stone, and charging a dollar. This was our first trip to the top.

Two days later there appeared to be more smoke than usual coming out of Vesuvius, and at night there was an obvious red glow at the top that had not been evident before. The next morning we returned to the top. This time we had to pick our way around and over swollen streams of molten stone. You could walk on the spongy, black surface of the fast cooling lava but underneath was a deep red glow. As these streams struck trees or bushes, there was a match-like spurt of flame, then the tree or twig simply disappeared with a little puff of smoke.

We were still not alarmed, for the slowly advancing streams seemed to pose no serious problem for the farms and villages further down the mountain.

The falling debris . . . ashes, cinders of great size, and acrid smoking clinker, made the wearing of helmets mandatory. Natives living on the higher elevations of the mountain in villages and farms streamed down the volcano side taking refuge in churches, where there was much wailing and praying. There were some small villages, farms and vineyards destroyed. Vesuvius was erupting!

In the dark before dawn we couldn't assess our damage, but it became quite clear when morning arrived. Every airplane was riddled with gaping jagged holes in wing and fuselages. Ashes were built up to the top of the landing gear. For those sleeping in tents, it had been a frightful night. In their tattered and sieve-like condition, tents were no protection.

Our planes were thus ruined, and with a volcano of indeterminate length raging above us, a quick decision to evacuate was ordered. As quickly as possible we fled as the Pompeians had done 19 centuries before. Only in our case we fled in trucks and jeeps, going down the coast for many miles to an area that had once been a Greek colony, and where still stood a Greek temple . . . Paestum.

The irony of it all was that the Axis Powers had been trying to put us out of business for a long time. But what they had not been able to do in many months, Vesuvius accomplished in one night.”

FROM CATCH-22

The chaplain felt his face flush.

“I'm sorry, sir. I just assumed you would want the enlisted men to be present (for prayers) since they will be going on the same mission.”

“Well, I don't. They've got a God and chaplain of their own, haven't they?”

“No, sir.”

“What are you talking about? You mean they pray to the same God we do?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And He listens?” (p. 191)

DECORATIONS

THE TRUE STORY

BY ROBERT B.

MARINO, DOC

MARINO'S SON

“I made contact with Mr. Heller through his literary agent. I asked him if my father was the flight surgeon mentioned in his book. He stated he was. I also related a story my father told me. Whenever a new group of flight crews returned from their first missions, there would be a line out in front of the medical tent. ‘Doc, it's dangerous up there, you've got to get me out of here.’ In fact, my father stated that several members threatened him with bodily harm if he didn't act favorably on their transfer requests. This was truly Catch-22!”

THE TRUE STORY • BY FRED DYER

“My most memorable mission? I could hardly forget the one on July 17, 1943, over the Herman Goering Division at Randazzo, Sicily, when I got shot down. On this mission we got hit by ack-ack approaching the target at thirteen thousand feet. I was number three in the box. We had a big hole in the right wing as if an 88 mm shell had gone right through it, the nose was blown off, the right engine was running away and all the engine controls were ineffective. We kept on going over the target and managed to drop our bomb load at six thousand feet. We could see the rest of the formation heading for home. The airplane wasn't flying very good by this time and we kept losing altitude. At twenty-five hundred feet it was time to bail out. John Falwell, my copilot, Pete Cusintine, the engineer, and I got out. One crewmember went down with the plane. John, Pete and I landed in a burned over wheat field and managed to evade capture. One other crewmember was captured. We had apparently landed in the midst of a tank battle between the German troops and the British 51st Highland Division. Later on that afternoon we were picked up by a tank of the 51 st Division and taken to their field headquarters where we spent the night listening to shells whistle over. We talked to one British major who had been in the Middle East for three years at that time. What a battle-hardened, tough outfit this was. After a week's odyssey we finally got back to Hergia, Tunisia. That was my twelfth mission.”

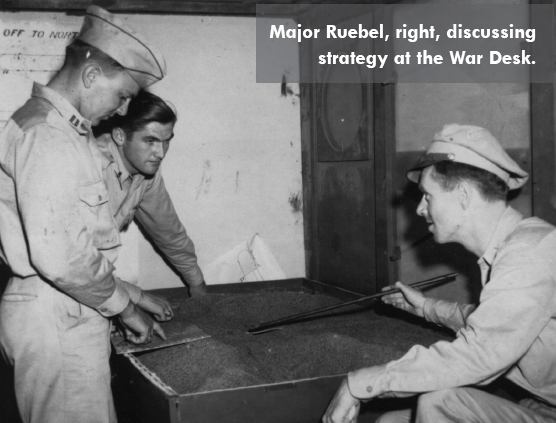

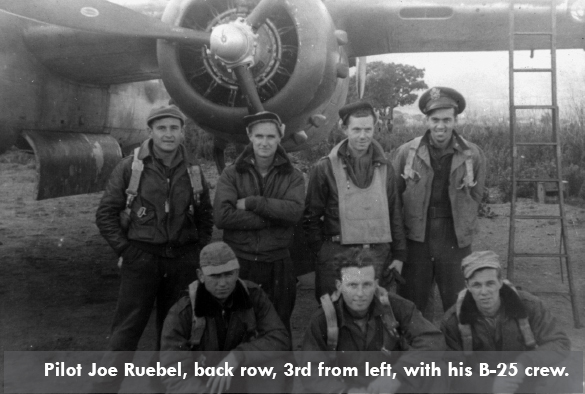

THE TRUE STORY • BY JOE RUEBEL

“A seldom mentioned occupational hazard encountered in the air war over Italy was the outside temperature at B-25 bombing altitude in the wintertime. The gauge in the aircraft often indicated an outside air temperature reading of -50 degrees. As this reading was the bottom of the scale on the gauge, the actual temperature might have been lower.

Unfortunately, any provision for crew comfort was eliminated with thoroughness and efficiency which couldn't have been better designed by the enemy. First, all B-25s delivered to this group by the depot had had the hot air heaters removed. This was presumably to decrease the danger of fire in the event of a hit by bullets or flak. Congealed crew members returning from a particularly gelid mission have been heard to wish wistfully that they’d been shot down in flames. Second, B-25s were designed to fly at the warmer medium altitudes and thus the crews did not require electrically heated flying suits, in the opinion of those responsible for equipping said crew members. Leather, sheepskin-lined flying clothes were available. In the opinion of most of us, these served admirably to keep the cold inside the garments. This was especially true of the boots. We were surprised when we removed them after landing to find that feet weren't solidly encased in ice. Add to this discomfort the fact that the garments were very bulky, and when combined with the extra underclothes, the Mae West, and the flak armor, the result was about as immobile as any combat-ready medieval knight.

One cold winter morning, I walked into Group operations to give Major George Wells, the assistant Group operations officer, any assistance he might need. George was responsible for planning and briefing the day's mission, which happened to involve bombing a bridge in Yugoslavia. He also happened to be scheduled to lead the mission. George and Fred Dyer, the other assistant, led the group in a number of missions and this was the first time the group was to fly over that country. Being first over a new country entitled one to a small degree of bragging rights, so I was mildly shocked when George offered to step aside to let me lead the mission. The surprise was instantly followed by suspicion. A short investigation revealed the motive. The upper air charts showed a free air temerature of -50 degrees. ‘Nice try, George.’ About that time Fred came in and went through the identical routine. A somewhat resigned Wells was about to accept the inevitable when in walked Lt. Colonel Earl Young. Earl was temporarily assigned to a headquarters with a fighter defense mission that was no longer required, and had wrangled an assignment to combat operations. He had flown some missions with us and, being an experienced officer, was perfectly capable of leading a formation. Three pairs of eyes met. Communication was perfect. I barely had the invitation out of my mouth when he accepted with an alacrity and gratitude which, fleetingly, made me feel a little guilty.

The poor guy returned about four hours later, and spent about that much time thawing out by wrapping himself around the red hot stove in Operations. He didn't seem to even notice the pungent odor of burning clothes, or show any inclination to move away from the stove. We've been in touch many times for over 42 or so years and he has yet to fail to bring the matter up. Sad to say, it seems that people's values seem to change. He no longer seems grateful for the opportunity to lead the formation.

By then Colonel Chapman had concluded that, regulations or not, the crews—in particular the bombardiers— could not operate at anywhere near peak efficiency under such conditions. Somehow he arranged to obtain enough heaters to install in the lead aircraft. As might be expected, bombing accuracy did indeed improve. Equally predictable was the fact that no unexplainable instances of aircraft fires occurred, and as far as I know no one in the responsible area of authority ever showed the slightest interest in the subject of unauthorized aircraft heaters.”

THE TRUE STORY • BY GEORGE WELLS

“I have known a few exceptional bombardiers but none were in the same league with Vincent Myers, better known to us as ‘Chief’ Myers. Here was a bombardier who seemed to have no equal. With the conversion to the Norden bombsight early in 1944, we increasingly took on the more difficult ‘pinpoint’ targets rather than the easier to hit ‘area’ targets. It was during this transition that Chief's real capabilities surfaced. He became the leader of the lead bombardiers. On one series of thirteen missions together, he, on each one of them, got direct hits on the most difficult of the pin-point targets—the twenty foot wide rail bridge from over two miles away. He was just amazing in his ability to hit a target even when the defenses were intense. He was fearless without equal, but this does not imply he was recklessly brave—he just had more calm fighting ability than the rest of us.

He was a very human person who got fun out of life. Once things were a little duller than usual on a stand-down day due to weather, and Chief talked Fred Dyer and Cal Moody and me into having a flare gun battle with the British Army Liaison Officer and his assistants. Have you ever seen a flare hit a tent? To say the least— we were lucky we didn't start a fire we couldn't control or hurt someone. It was also fortunate Chapman was gone for the day.

On another occasion, after having arranged for the British Liaison Officer to go on his first combat mission, a ‘milk run,’ Chief and I took down the British tent while he was on the mission and marked his gear for ‘Next of Kin.’ Thank heavens he returned safely. We did help him put his things back together again.”

Below: Wells, Myers, and Leonard Kaufman, Squad Commander of the 489th, February 28, 1945.

THE TRUE STORY • BY GEORGE WELLS

“Having been a Field Artillery officer prior to becoming a pilot in the Air Corps, I continued to wear my garrison cap as I did in the Field Artillery. I wouldn't wear the earphones (head set) over the outside of the cap, which would crush the crown. A crushed garrison cap in the Air Corps was the ‘in thing,’ the mark of a pilot. Well, I had a brand new garrison cap when I left for overseas with a real good military appearance. It had a great Field Artillery look but not an Air Corps look. When I joined the 488th Squadron I didn't wear it much, but when I did, I received a lot of kidding. In late April, 1944 I got a chance to fly down to Alexandria and Cairo for a week's rest with two other officers and five enlisted men. Homer Howard and I rotated on each leg of the flight from pilot to copilot position. On the second leg I was in the pilot's seat with my headset on and my great garrison cap sitting on the top of my head over the headset. By this time we were over the desert and it was very hot in the B-25 (no air-conditioning). We had opened the two sliding side windows in the cockpit to suck some of the heat out. I had been flying the plane for 11-12 hours and I turned it over to Homer in the copilot's seat. As I leaned to the left my cap just flew straight out the small opening. Some Arab must have found a beautiful cap and the guys never let me forget the consequences of my refusal to accept ‘The Crushed Hat’.”

“Jerre Cover was an absolute gentleman through and through. He was older than most of the other men, fifty-ish. He had grey hair, even at that time, with a face that was tan and deeply lined. He was more of a father figure than a military figure to the men. He was lean, alert and a tough cookie.”

—Forrest Wells and Bill Chapman

FROM CATCH-22

“Major___de Coverly was a splendid, aweinspiring, grave old man with a massive leonine head and an angry shock of wild white hair that raged like a blizzard around his stern, patriarchal face. His duties as Squadron Executive Officer did consist entirely . . . of pitching horseshoes, kidnapping Italian laborers, and renting apartments for the enlisted men and officers to use on rest leaves, and he excelled at all three.” (p. 130)

“When the Germans left the city, I rushed out to welcome the Americans with a bottle of excellent brandy and a basket of flowers. The brandy was for myself, of course, and the flowers were to sprinkle upon our liberators. There was a very stiff and stuffy old major riding in the first car, and I hit him squarely in the eye with a red rose. A marvelous shot! I got him in the eye with an American Beauty rose. I thought that was most appropriate. Don't you?” (p. 241)

BOOK CHARACteRS & MEN OF THE 340TH

JOHN YOSSARIAN

He was the best man in the group at evasive action, but had no idea why.

(Joseph Heller's “wishful incarnation”)

Yossarian was a lead bombardier who had been demoted because he no longer gave a damn whether he missed or not. He had decided to live forever or die in the attempt, and his only mission each time he went up was to come down alive. (p. 29)

“A nearby tent . . . was the tent of a friend, Francis Yohannon, and it was from him that I, nine years later, derived the unconventional name for the heretical Yossarian. The rest of Yossarian is the incarnation of a wish.”1

“At a reunion years later Francis Yohannon told us that Heller had used his name for the character Yossarian. Heller used the first part of his name and combined the last part with the fact that he was, by birth, Syrian.”2 (Catch-22's Yossarian was Assyrian.)

Captain John Yossarian sprang from the mind of Joseph Heller. He took with him Heller's thoughts, his mannerisms, his creativity and unconventionality and, perhaps, even his appearance. They shared a devil-may-care attitude, a logical outlook, a quirky nature, and an irreverent, quick humor. Indeed, Joseph Heller birthed Yossarian.

In an article that she published for The New York Times Book Review, writer Barbara Gelb once described her friend, Joseph Heller. “For twenty years now, I have managed to overlook his frequent sulkiness, his gluttonous table manners and his tendency to growl ‘No’ before he even knows what the question is. I have stayed on good terms with him largely because I relish his aberrant sense of humor and his skewed way of looking at life — an outlook he insists has changed little since he wrote Catch-22.”

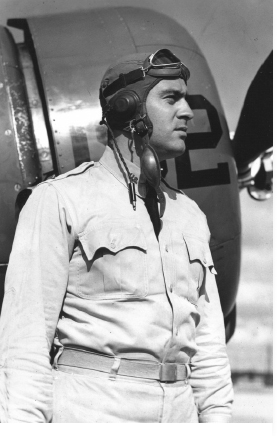

GENERAL DREEDLE

Wing commander with nubile nurse and captive son-in-law

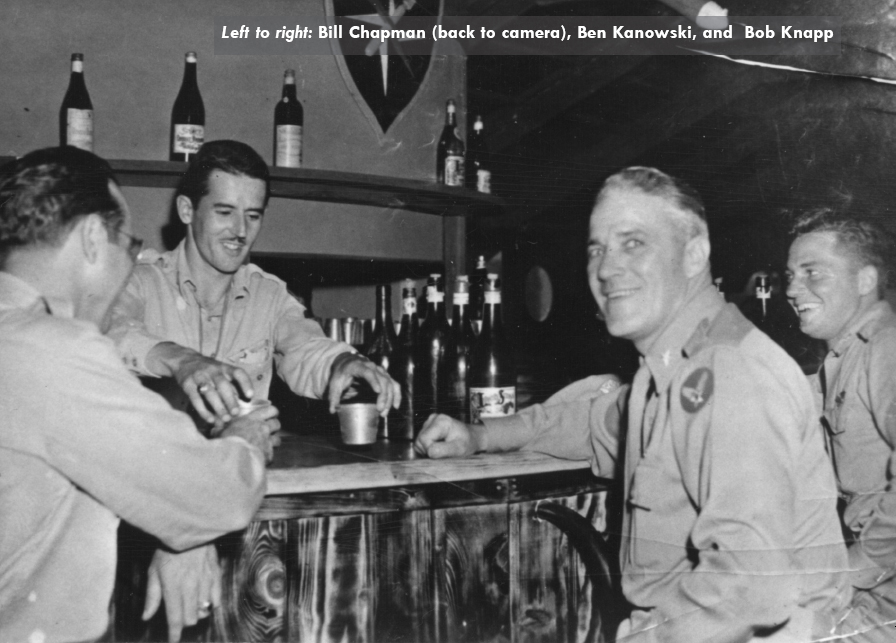

(General Robert D. Knapp)

General Dreedle, the wing commander, was a blunt, chunky, barrel-chested man in his early fifties. General Dreedle had wasted too much of his time in the Army doing his job well, and now it was too late. (p. 212)

Brigadier General Robert D. Knapp was, indeed, older than his men. He was born in 1897; his pilot's license #185 was signed, years later, by Orville Wright who, with his brother Wilber, lived three houses away from young Knapp for a few months while working on their fledging airplane. He served in World War I, he flew in the border war against Pancho Villa, he barnstormed across the country trying to get Americans interested in aviation, he flew the first airmail route from Montgomery, Alabama and New Orleans, Louisiana. These events occurred before most of the men he commanded in World War II had even been born.

But Knapp himself was a man who was born to fly. There was nothing he would rather do. As well, this was a man who was born to lead. Yes, he had spent much of his life doing his job well. What greater confirmation than to be so highly respected by the men under his command, “his boys.”

Knapp had a son, Robert D. Knapp, Jr. who also entered World War II. When Knapp, Jr. became a second lieutenant he also became his father's aide de camp. Patterning on Lt. Knapp, Jr., Heller loosed his intense creativity in developing Colonel Moodus, changing him into a son-in-law in Catch-22 who General Dreedle delighted in keeping miserable. Here is where Heller and Knapp parted company. General Knapp and his son stayed on the serious course of dealing with this war.

General Knapp had become a bit of a legend. His life was a history book for facts, a Jack London novel for fiction, and a dash of Will Rogers for easy humor.

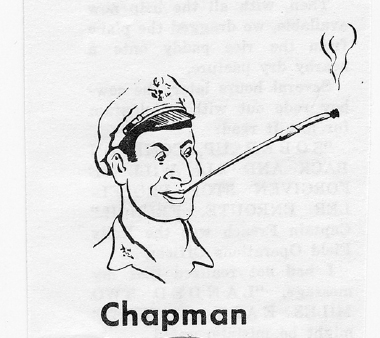

Bomb Group commander who calculated day and night in service of himself.

(Colonel Willis F. Chapman)

Colonel Cathcart was a very large, pouting, broad-shouldered man with close-cropped curly dark hair that was graying at the tips and an ornate cigarette holder that he purchased the day before he arrived in Pianosa to take command of his group. He displayed the cigarette holder grandly on every occasion and had learned to manipulate it adroitly. Unwittingly, he had discovered deep within himself a fertile aptitude for smoking with a cigarette holder. As far as he could tell, his was the only cigarette holder in the whole Mediterranean theater of operations, and the thought was both flattering and disquieting. (p. 185)

Here's what George had to say about Colonel Cathcart — and Colonel Chapman.

Heller made many traits, appearance and personality comments about Cathcart, the character he drew from Colonel Chapman — some are very true and some are very wrong. But the one that fits him the most is the one about Col. Chapman when he walks up to the front of the room on his first meeting with the combat crews and told us we were now going to “fly straight and level for some minutes from the Initial Point to the target,” and in his hand was this long Zeus cigarette holder. I didn't smoke so I wasn't pleased with this new colonel.

Well, that colonel went on to become a great leader and made the 340th Group outstanding. It became a leader in hitting pinpoint targets. His several-minute bomb run, straight and level, gave the bombardiers (even average ones) time to determine wind conditions, find the target, set the sight, and hit the target. Some of Heller's words are right on; others are completely wrong. Colonel Chapman was a top tactician with a very innovative mind. He took us from being an average group to one that could fly great formations with a large number of planes, one that could get the combat job done without problems, one with ground crews as well as aircrews doing the job successfully without complaint. The people understood the need and did all the jobs gladly, with competence, thanks to Colonel Chapman. I really don't see many incidents apply to Colonel Chapman in Heller's book, but the descriptions fit so correctly on a number of things like size, cigarette holder, and a number of the positive adjectives.3

One morning at Group breakfast, immediately after the new commander's arrival, the 340th HQ staff all popped out Colonel Chapman-style cigarette holders that they had flown in from Rome. Deputy Group CO Lt. Colonel “Mac” Bailey and voluptuous Red Cross gal Dita Davis instigated the joke.

Cartoon of Chapman with cigarette holder drawn by Captain Jack C. Mair, pilot, 489th.

MAJOR__DE COVERLEY

Everyone was afraid of him and no one knew why.

(Major Charles Jerre Cover)

Each time the fall of a city like Naples, Rome or Florence seemed imminent, Major_de Coverly would pack his musette bag, commandeer an airplane and a pilot, and have himself flown away, accomplishing all this without uttering a word, by the sheer force of his solemn, domineering visage and the peremptory gestures of his wrinkled finger. A day or two after the city fell, he would be back with leases on two large and luxurious apartments there, one for the officers and one for the enlisted men, both already staffed with competent, jolly cooks and maids. A few days after that, newspapers would appear throughout the world with photographs of the first American soldiers bludgeoning their way into the shattered city through rubble and smoke. Inevitably, Major_de Coverley was among them, seated straight as a ramrod in a jeep he had obtained from somewhere, glancing neither right nor left as the artillery fire burst about his invincible head and lithe young infantrymen with carbines went loping up along the sidewalks in the shelter of burning buildings or fell dead in doorways. He seemed eternally indestructible as he sat there surrounded by danger, his features molded firmly into that same fierce, regal, just and forbidding countenance which was recognized and revered by every man in the squadron. (pp. 130-131)

About the actual event, Heller relates:

On June 4, 1944, the first American soldiers entered Rome. And no more than half a step behind them, I think, must have come our own squadron's resourceful executive officer, for we received both important news flashes simultaneously: the Allies had taken Rome, and our squadron had leased two large apartments there, one with five rooms for the officers and one with about fifteen rooms for the enlisted men. Both were staffed with maids, and the enlisted men, who brought their food rations with them, had women to cook their meals.4

George gives us his view on “de Coverley.”

Now here is a good example of copying name and actual actions by a real person in the book. The 488th squadron executive officer was Major Charles J. Cover. You can't get much closer in a name and position and rank and still call it fictitious. Cover was medium height, not tall. His face could be called craggy as in Catch-22. Cover was a fine older gentleman to us people in the squadron. (Cover was born in 1896 and would have been all of 48 years old.) Very well liked. He had dignity but was not fierce. He seemed old to us, was splendid, slightly stern face and maybe a slightly patriarchal face. I recall that he did play a lot of horseshoes. He did arrange for barbers who were from Italy. He had arranged for an apartment in Italy to be used by the enlisted men on short rest trips. He was well liked by members of the squadron.5

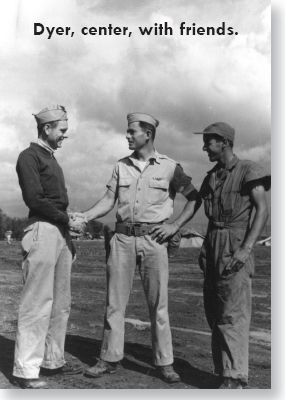

CAPTAINS PILTCHARD AND WREN

Joint squadron operations officers who flew endlessly andfearlessly.

(Capt. Fred W. Dyer and Capt. George L. Wells)

Captain Piltchard and Captain Wren, the inoffensive joint squadron operations officers, were both mild, soft-spoken men of less than middle height who enjoyed flying combat missions and begged nothing more of life and Colonel Cathcart than the opportunity to continue flying them. They had flown hundreds of combat missions and wanted to fly hundreds more. Nothing so wonderful as war had ever happened to them before, and they were afraid it never would happen again. (p. 144)

About this reference, George says:

Dyer and I were both captains until late 1944. Dyer was Piltchard and I was Wren. Less than middle height (Dyer was 5’9” and I was 5’7”) we both did like to fly a lot and we became better by flying more. Dyer and I would go up and fly in two planes on each other's wing. Many times on down days or when we weren't on a mission, we would fly in heavy weather conditions in formation — practice single engine in formation. We flew the planes in practice under various types of conditions to fully understand its performance as well as its limitations. We really set the tone for combat in the 340th. What we both did was to (1) eliminate the basis for bellyaching by the combat crews due to any concern over the B-25's performance even when heavily damaged or due to fear for oneself while in combat, and (2) set an example by flying additional missions without having to do it — and never picking a mission because it was considered a milk run; in fact, we did the opposite — the more challenging [the mission], the more we competed with each other.6

Everyone was always very friendly toward him, and no one was ever very nice; everyone spoke to him, and no one ever said anything.

(Chaplain James H. Cooper)

It was love at first sight. The first time Yossarian saw the chaplain he fell in love with him. (p. 7)

“Fred, Lou and I flew this flight to show the combat crews that the new H model B-25s could fly and land on a single engine, which was of major importance. note we each have a prop at standstill.” — George Wells

“A.T. Tappman — Group Chaplain. Of course Chaplain Tappman is a comical joining of title with a name. The real chaplain was James Cooper. There is a tie in Heller's use of the name Tappman for a Group level officer to the name Chapman also at Group level.”7

Fictional Chaplain Tappman and counterpart Chaplain Cooper both lived alone in a spacious tent in the woods a goodly distance from the squadron encampments and Group Headquarters.

. . . he toyed unfamiliarly with the tiny corncob pipe that he affected self-consciously and occasionally stuffed with tobacco and smoked. (p. 265)

Maj. Fred Dyer (9Z), Lt. Col. Lou Keller (6P), and Maj. George Wells (8r) after practicing single-engine maneuvers in the B-25.

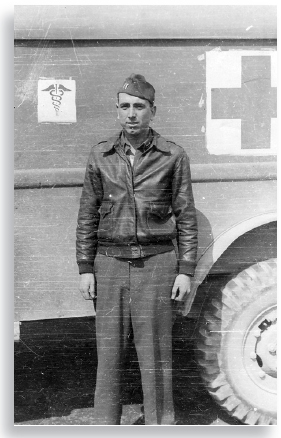

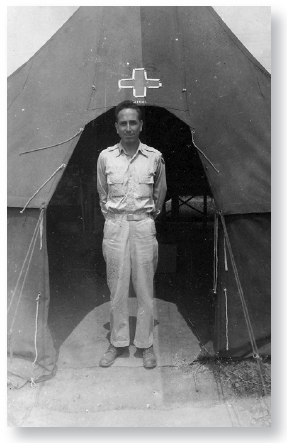

DOC DANEEKA

A neat and clean hypochondriac whose idea of a good time was to sulk.

(Captain Benjamin J. Marino, MD)

Doc. Daneeka had been drafted and shipped to Pianosa as a flight surgeon even though he was terrified of flying. He felt imprisoned in an airplane. In an airplane there was absolutely no place in the world to go except to another part of the airplane . . . (p. 41)

. . . get McWatt to put my name on his flight log again so I can draw my flight pay without going up in a plane.

“I don't know why they want me to put in four hours flight time every month in order to get my flight pay. Don't I have enough to worry about without worrying about being killed in an airplane crash too?” (p. 174)

Yossarian would persuade McWatt to enter Doc. Daneeka's name on his flight log for training missions or trips to Rome . . . (p. 174)

“You're dead, sir.”

“It's true, sir,” said one of the enlisted men. “The records show that you went up in McWatt's plane to collect some flight time. You didn't come down in a parachute, so you must have been killed in the crash.”

“Gee, I guess he really is dead,” grieved one of his enlisted men in a low, respectful voice (still standing next to Doc). “I'm going to miss him. He was a pretty wonderful guy, wasn't he?”

“Yeah, he sure was,” mourned the other. “But I'm glad the little fuck is gone. I was getting sick and tired of taking his blood pressure all the time.” (p. 335)

The military doctors drew flight pay by logging in flight time, often in the night hours. As the war progressed the rules were bent a bit with the realization that this was too dangerous to expose doctors to when their skills were so needed on the ground. So their names were sometimes logged in on a flight that their bodies did not accompany. Joseph Heller delightedly embellished on that fact with this episode of Doc supposedly having been killed in McWatt's plane.

Our flight surgeon was Captain Benjamin W. Marino. Heller's description of him is close. He did seem sad and was a recluse. We used to say when you went to see him all you got was an aspirin. Most people can adapt to the situations they find themselves in during their life, but Dr. Marino couldn't find much in his daily life, during the war, to please him.8

“He was compassionate and caring. The men laughingly swore that Marino delivered more Italian babies than the number of soldiers he cared for.”9

THE SOLDIER IN WHITE

No sound at all came from the soldier in white all the time he was there.

The people got sicker and sicker the deeper [they] moved into combat, until finally in the hospital that last time there had been the soldier in white who could not have been any sicker without being dead, and he soon was. (p. 165)

A bombardier in the 489th, Hal Lynch, witnessed an event so stirring that it embedded itself deeply within his memory and stayed with him for the remainder of his long life. In 2002 he transferred this experience to paper as he penned the following:

During World War II my B-25 medium bomber group was stationed on the beautiful Island of Corsica, a French possession in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Our dirt runway bordered the sea. On a clear day the island of Elba to the east was clearly visible. In October of 1944 I witnessed a most remarkable scene from the center of that dirt runway. It happened to be a special occasion, the recognition of our group for its year of service in combat in the European Theater of Operations. During this year many men in the group had been killed or were interred in Italy or had gone down at sea.

Thus a memorial service was planned. A temporary platform, facing the sea, had been constructed on the runway. Dignitaries from the 12th Air Force and from the United States Congress had been invited to be a part of the tribute. Our 57th Bomb Wing Commander, Brigadier General Robert D. Knapp, had been asked to serve as the main speaker.

On that memorable day in 1944 a 12th Air Force general opened the program with a short speech, given while facing the dignitaries, with his back to the Tyrrhenian Sea. And then General Knapp was introduced.

He walked to the microphone, glanced at the dignitaries, and then turned his back to them and faced the sea. For the next twenty minutes the general spoke to his men, the men who had been lost in Italy or in the sea. He apologized to them for his part in sending them into combat — for not being a better leader, a closer friend. And then in a throbbing voice, he told the men he would never forget them and he would never allow our nation to forget them — that he would try to repay them for their great sacrifice by living beyond himself in the years ahead.

The general never did look back at the dignitaries on the platform. In fact, he had probably forgotten they were there. This was a private moment. He was alone with his men. When he completed his tribute he walked away from the platform, heading in the direction of his favorite B-25 parked at the end of the runway

I realized that I had been part of an unforgettable experience. I had always accepted the fact that General Knapp was a great leader, but on that beautiful day on Corsica I realized that he was more than a great leader. This outstanding man was also an inspiration to all who knew him.10

MAJOR DANBY

“It must be nice to live like a vegetable, he conceded wistfully.”

“A cucumber or a carrot.”

(Major Joseph W. Ruebel)

. . . the gentle, moral, middle-aged idealist.

. . . “I'm a university professor with a highly developed sense of right and wrong, and I wouldn't try to deceive you. I wouldn't lie to anyone.”

“What would you do if one of the men in this group asked you about this conversation?” [Yossarian asked.]

“I'd lie to him.” (p. 434)

That's Joseph W. Ruebel, our Group Operations Officer. Chief, Dyer and I worked for him, he was our immediate boss. Joe Ruebel was a great boss with a great personality. Everyone liked him. He was thorough at his job and was a gentle and modest man. He did let us three influence combat tactics decisions because all three of us had so much more combat experience then he did.

Chief and I tented with Joe when we moved up to Group Headquarters.11

HUNGRY JOE

He crumbled promptly into ruin every time he finished another tour of duty, followed by ear-splitting nightmares.

(Joseph Chrenko, Pilot)

Every time Colonel Cathcart increased the number of missions and returned Hungry Joe to combat duty, the nightmares stopped and Hungry Joe settled down into a normal state of terror with a smile of relief. Yossarian read Hungry Joe's shrunken face like a headline. It was good when Hungry Joe looked bad and terrible when Hungry Joe looked good. (p. 54)

“In Yohannon's tent also lived Joe Chrenko, a pilot I was especially friendly with who later, in several skimpy ways, served as the basis for the character Hungry Joe. In that tent with them was a pet dog Yohannon had purchased in Rome. In my novel I turned the dog into a cat to protect its identity.”12

Heller's 7 th mission. To Cecina, Italy.

Heller: [Just] Hungry Joe. His real name is Joe Chrenko and he now [1975] is an insurance agent in New Jersey.

Playboy: Hungry Joe is the one who has screaming nightmares in his tent. Did Chrenko also run around Rome claiming to be a Life photographer so he could take pictures of naked girls?

Heller: Only once.

Playboy: Did he complain about the way you portrayed him in the book?

Heller: His only complaint is that I didn't use his last name. He feels it would have helped his insurance business.13

LUCIANA

“All right, I'll dance with you,” she said, before Yossarian could even speak.

“But I won't let you sleep with me.”

“Who asked you?” Yossarian asked her.

“You don't want to sleep with me?” she exclaimed with surprise.

“I don't want to dance with you.” (p. 152)

“That's just what happened to me in Rome. Luciana was Yossarian's vision of a perfect relationship. That's why he saw her only once, and perhaps that's why I saw her only once. If he examined perfection too closely, imperfections would show up.”14

Milo had been caught red-handed in the act of plundering his countrymen, and, as a result, his stock had never been higher.

(Benjamin Kanowski, Pilot & Mess Officer)

“What's your name, son?” asked Major___de Coverley.

“My name is Milo Minderbinder, sir. I am twenty-seven years old.”

“You're a good mess officer, Milo.”

“I'm not the mess officer, sir.”

“You're a good mess officer, Milo.”

“Thank you, sir, I'll do everything in my power to be a good mess officer.” (p. 134)

Ben Kanowsky is considered the character that Heller based Milo on. His function was to try to obtain, by trade or purchase, food (greens, eggs, etc.) for our enlisted and officers’ mess tents. Heller took gross liberties with this character. Ben also had an inventive mind and did work on some ideas for the group. One of these ideas involved firing chaff ahead of the element to increase defense against ack-ack (flak), anti-aircraft artillery.15

HAVERMEYER / CHIEF WHITE HALFOAT

(Major Vincent Myers)

He had grown very proficient at shootingfield mice at night with the gun he had stolen from the dead man in Yossarian's tent.

His bait was a bar of candy . . . (p. 30)

Havermeyer was the best damned bombardier they had, but he flew straight and level all the way from the IP to the target, and even far beyond the target until he saw the falling bombs strike ground and explode in a darting spurt of abrupt orange that flashed beneath the swirling pall of smoke and pulverized debris geysering up wildly in huge, rolling waves of gray and black. Havermeyer held mortal men rigid in six planes as steady and still as sitting ducks while he followed the bombs all the way down through the Plexiglas nose with deep interest and gave the German gunners below all the time they needed to set their sights and take their aim and pull their triggers or lanyards or switches or whatever the hell they did pull when they wanted to kill people they didn't know. (p. 29)

There is no doubt Havermeyer is Capt. Vincent Myers (“Chief” Myers). Catch-22's description of him: Lead bombardier. Best one in the group. Flew straight and level over the target, never missed, used candy to bait mice and then shot them. But Heller didn't make the character an Indian. Heller used Chief Myers’ Indian background in the character Chief White Halfoat. Chief and I flew a lot of missions together as lead pilot and lead bombardier. Chief and I were the best of friends and always flew together whenever we could. We tented together for over a year in combat so I knew him as well as or better than anyone else in the group. If there was a tough target or one hard to find we, as a team, flew a large number of them. Chief was a gentleman and a great and loyal friend, father, and husband during and after the war. Chief was the best bombardier in the Group by far, and the bravest bombardier I ever knew. In fact, in my opinion, I think he was one of, if not the, best in WWII.

When the Norden bomb sight (excellent for pinpoint targets such as bridges) replaced the Mark IX bomb sight (good for area targets but not pinpoint), orders were given for the five-minute bomb run. Straight and level with no evasive action. No one ever took Chief to task, as mentioned in Catch-22 for flying straight and level over the target, but he would want us to hold it a few seconds longer after Bombs Away before the break away to give our vertical cameras a better chance of getting a picture of the target area for results.

Chief did shoot at mice a couple of times while in the 488th to try to keep them away from his candy ration, and he was a good shot.16

Chief White Halfoat was out to revenge himself upon the white man. He could barely read or write and had been assigned to Captain Black as assistant intelligence officer.

Handsome, swarthy, Indian from Oklahoma with a heavy, hardboned face and tousled black hair. A half-blooded Creek from Enid. (p. 43)

Again, this is Chief Myers. He was every one of those words except he was a half-blooded Comanche from Apache, Oklahoma.

Chief did have an incident with Gen. Knapp's MOE (a lieutenant) at a rest hotel on the northeast coast of Corsica on a Saturday night. Chief's notoriety as a Golden Gloves champ was well known. Sometimes a man likes to show his masculinity by talking tough to such a person as Chief. There was a small band playing music on this Saturday night in late 1944 at the hotel. The aide pushed Chief too far and Chief hit him, picked him up and tossed him into the musician's drum. This may be the connection to Halfoat, on many occasions, hitting Gen. Dreedle's son-in-law, Col. Moodus. (Counterpart General Knapp's son, Robert Knapp, Jr.) Again, Heller created a name, Col. Moodus, most likely drawing upon one close to that of a 340th officer, Cal Moody, the group navigation officer.17

COLONEL MOODUS

(Lt. Robert D. Knapp, Jr.)

Colonel Moodus was General Dreedle's son-in-law, and General Dreedle, at the insistence of his wife and against his own better judgment, had taken him into the military business. General Dreedle gazed at Colonel Moodus with level hatred. He detested the very sight of his son-in-law, who was his aide and therefore in constant attendance upon him. He had opposed his daughter-'s marriage to Colonel Moodus because he disliked attending weddings . . . (p. 36)

“War is hell,” he declared frequently, drunk or sober, and he really meant it, although that did not prevent him from making a good living out of it or from taking his son-in-law into the business with him, even though the two bickered constantly. (p. 212)

“I was back at 57 th Wing Headquarters on schedule. I rounded up a crew, which now included Bob Jr. (General Knapp's son, Lt. Robert D. Knapp, Jr.) — new 2nd Lieutenant — as my Aide,”18 confirmed Bob Knapp.

DOUGLAS ORR

(Douglas Orr, Bombardier/Navigator)

“You [Yossarian] really ought to fly with me, you know. I'm a pretty good pilot, and I’d take care of you.”

“Will you fly with me?”

Yossarian laughed and shook his head. “You'll only get knocked down into the water again.”. . .

Orr did get knocked down into the water again when the rumored mission to Bologna was flown, and he landed his single-engine plane with a smashing jar on the choppy, wind-swept waves tossing and falling below the warlike black thunderclouds mobilizing overhead. He was late getting out of the plane and ended up alone in a raft that began drifting away from the men in the other raft and was out of sight by the time the Air-Sea Rescue launch came plowing up through the wind and splattering raindrops to take them aboard. Night was already falling by the time they were returned to the squadron. There was no word of Orr . . . (p.310)

“Orr?” cried Yossarian.

Washed ashore in Sweden after so many weeks at sea! It's a miracle. “Washed ashore, hell!” Yossarian declared, jumping all about also and roaring in laughing exultation at the walls, the ceiling, the chaplain and Major Danby. “He didn't wash ashore in Sweden. He rowed there! He rowed there, chaplain, he rowed there.”

“Can't you just picture him?” he [the chaplain] exclaimed with amazement. “Can't you just picture him in that yellow raft, paddling through the Straits of Gibraltar at night with that tiny little blue oar —”

“With that fishing line trailing out behind him, eating raw codfish all the way to Sweden, and serving himself tea every afternoon —” (pp. 438-439)

Douglas Orr was the only character in Catch-22 who retained his own name. While returning from a mission, bombardier/navigator Douglas Orr's aircraft was downed over the Mediterranean. Orr and the rest of the crew barely had time to throw out the rubber raft, with its little blue oars, and grab their jungle kits. They began paddling towards Tunisia and after twelve hours, guided by Orr, the raft reached land behind enemy lines. The Stars and Stripes newspaper reported how these shipwrecked fliers, still led by Orr, took cover in the tall brush. At one point they encountered a herd of goats, which they milked and then slept with for warmth. They walked for four days, wore out their shoes on the rugged terrain, and eventually had the good fortune of making contact with an advance British patrol.19

In Heller's autobiography, he reveals that he based Orr's character also on a pilot named Edward Ritter who shared Heller's tent. Again, two personalities have merged. Ritter was a “tireless handyman,” building the elaborate fireplace with a mantel in their six-man tent, assembling their gasoline stove, and creating a washstand out of a bomb rack and a flak helmet. Just like Orr, Ritter also had a penchant for ditching in the water and crash-landing safely on land without losing a single crewman:

Remarkably, through all his unlucky series of mishaps the pilot Ritter remained imperviously phlegmatic, demonstrating no symptoms of fear or growing nervousness, even blushing with a chuckle and a smile whenever I gagged around him as a jinx, and it was on these qualities of his, his patient genius for building and fixing things and these recurring close calls in aerial combat, only on these, that I fashioned the character of Orr in Catch-22.20

MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR

(Major Major and Capt. Randall C. Cassada)

Major Major Major Major had had a difficult time from the start . . . (p. 81)

Major Major had been born too late and too mediocre. Some men are born mediocre, some men achieve mediocrity and some men have mediocrity thrust upon them. With Major Major it had been all three . . . (p. 82)

It was still more frustrating to try to appeal directly to Major Major, the long and bony squadron commander, who looked a little bit like Henry Fonda in distress and went jumping out the window of his office each time Yossarian bullied his way past Sergeant Towser to speak to him about it [the dead man in his tent]. (p. 22)

He is Randall C. Cassada and he was a captain and squadron commander when I arrived in the squadron. Heller says, “Major Major Major Major (the squadron commander) was long and bony — looked a bit like Henry Fonda in distress” (p. 22), a description that fits Cassada. And like Major Major Major Major he also played basketball once in a while and was withdrawn by nature. Didn't talk much. In the Group there was also another officer named Major Major, upon whose name Heller drew. The squadron was, in my opinion, the best in the Group. Most of the people who ended up in key jobs came from the 488th. That movement of key people alone justified the fact that the 488th was the top squadron in the top Group in the top Wing in World War II. So Cassada must have been doing something right.”21

THE DEAD MAN IN YOSSARIAN'S TENT

(The Dead Man In The Tent)

Mudd was the unknown soldier who had never had a chance, or that was the only thing anyone ever did know about all the unknown soldiers — they never had a chance. They had to be dead. And this dead one was really unknown, even though his belongings still lay in a tumble on the cot in Yossarian's tent. (p. 107)

Originally Yossarian bunked with Orr and “The Dead Man” who died before he even got there.

The sad story of “The Dead Man in Yossarian's Tent” was based in truth. A soldier had reported in, had been sent on a mission, and had been shot down and killed before his orders had even arrived. He — actually, his belongings — remained in the tent until the red tape cleared “him” for return to the States.

That story of the dead man in the tent, it's sort of factual. He was shot down before his orders came in. He just lay around until the red tape caught up. Then we post-dated his orders, and got him out of there. The human mind is funny. You reach a point where it shuts things out. We thought it was funny, where's your buddy, and all there was, was an empty bunk. People were put in a position of doing things they didn't want to do.22

Heller, like Yossarian, also had a vacant cot in his tent until pilot Ritter claimed it. This cot had belonged previously to a bombardier named Pinkard, who, on a mission over Ferrara, was shot down and killed.

KID SAMPSON

Bill Simpson, Pilot

. . . preparedfor any morbid shock but the shock McWatt gave him [Yossarian] one day with the plane that came blasting along the shore line with a great growling, clattering roar over the bobbing raft on which blond, pale Kid Sampson, his naked sides scrawny even from so far away, leaped clownishly up to touch it at the exact moment some arbitrary gust of wind or minor miscalculation of McWatt's senses dropped the speeding plane down just low enough for a propeller to slice him half away. . . .

Even people who were not there remembered vividly exactly what happened next. (p. 331)

George Wells says about this:

Now this is what I think Heller did: He took two actual incidents — one, the only plane on a non-combatant flight to crash into a mountain and two, a mid-air collision that cut most of the tail off of one of the planes. The only person killed in that plane was the tail gunner, who was cut right out of the tail and never heard of again. Heller tied these two incidents in with an actual name, pilot Bill Simpson. In Catch-22 there is a character named Kid Sampson described as blond-pale-scrawny, who was cut in half by McWatt's low-flying plane that McWatt crashes into a mountain to pay for his miscalculation. He combined that incident with a mission that saw pilot “Dobbs who ‘zigged’ when he should have ‘zagged,’ skidded his plane into the plane alongside, and chewed off its tail. His wing broke off at the base, and his plane dropped like a rock and was almost out of sight in an instant. There was no fire, no smoke, not the slightest untoward noise. . . . It was over in a matter of seconds.” (pp. 368–369)

Heller may have drawn on Simpson, who piloted the plane that cut the tail section off of the other plane, and who was also very young, blond, and scrawny, and made him pay for slicing the tail gunner out of the plane by having him crash into the mountain.23

TARANTO

Taranto

. . . the alert sounded suddenly at dawn the next day and the men were rushed into the trucks before a decent breakfast could be prepared, and they were driven at top speed to the briefing room and then out to the airfield, where the clitterclattering fuel trucks were still pumping gasoline into the tanks of the planes and the scampering crews of armorers were toiling as swiftly as they could at hoisting the thousand-pound demolition bombs into the bomb bays. Everybody was running, and engines were turned on and warmed up as soon as the fuel trucks had finished. (p. 224)

Intelligence had reported that a disabled Italian cruiser in dry-dock at La Spezia would be towed by the Germans that same morning to a channel at the entrance of the harbor and scuttled there to deprive the Allied armies of deep-water port facilities when they captured the city. For once, a military intelligence report proved accurate. The long vessel was halfway across the harbor when they flew in from the west, and they broke it apart with direct hits from every flight that filled them all with waves of enormously satisfying group pride until they found themselves engulfed in great barrages of flak that rose from guns in every bend of the huge horseshoe of mountainous land below. Even Havermeyer resorted to the wildest evasive action he could command when he saw what a vast distance he had still to travel to escape, and Dobbs, at the pilot's controls in his formation, zigged when he should have zagged, skidded his plane into the plane alongside, and chewed off its tail. His wing broke off at the base, and his plane dropped like a rock and was almost out of sight in an instant. (pp. 368-369)

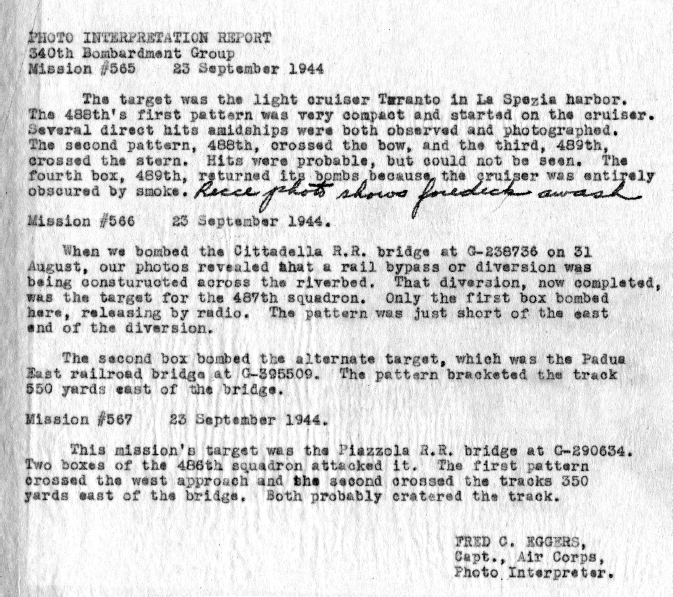

The following three photographs and two documents chronicle the astounding success of the rise and fall of the Italian cruiser, Taranto.

Top photo: What the bombardier saw from 11,000 feet and how he demolished this pinpoint target.

Bottom photo: The official photo of the bombing as it occurred.

Official interpretation of the technical details of the direct hits.