4 The Bosun Mine

In the aftermath of the California gold rush of 1849, a particular western North American version of industrial capitalism evolved in the hardrock mining camps of the American West. Well-established by the early 1880s not far south of British Columbia in the Coeur d’Alene district of Idaho, this hardrock mining complex readily crossed the border when, late that decade, silver-lead (galena) ores were found along Kootenay Lake. In 1891, it reached the Slocan. With it came more than a century’s experience with industrial capitalism, and much particular experience with mining and shipping in isolated, mountainous terrain. With it, too, came the institutions, services, and equipment required to support these activities. Tucked-away valleys, virtually unknown to the outside world, could be transformed almost overnight into thriving mining camps because analogous developments were not far away.

In the Slocan, as in other mining camps, prospectors made the early finds, but the promising claims they staked were soon in the hands of companies that employed managers to develop mines and foremen to oversee miners working for wages. Telegraph lines, steamboats, and railways, all quickly introduced, established essential connections with the larger world. Machinery for mining and concentrating ore, almost all of it manufactured in the US, was available. So were the tensions inherent to industrial capitalism. With the miners came a militant union—the Western Federation of Miners (WFM)—formed out of labour strife in Butte, Montana, in the 1880s, hostile to the capitalist system, and involved in several protracted and violent strikes in American mining camps. From the mine owners’ perspective, the WFM was a union of dynamiters and thugs; they formed mine owners’ associations, and hired Pinkerton detective agents to infiltrate the union.

American miners and capital dominated the early years of Slocan mining, but the American presence diminished as more miners from eastern Canada and western Europe arrived and British capital began to invest in Slocan mines. Most of the principal American mining magnates turned down the Slocan, judging its small and fractured veins inadequate to support major mines. There was room for British investment, and the Slocan began to attract an edge of the vast flow of capital leaving Britain in the two decades before World War I. British capital and management, usually administered from London, were superimposed on an essentially American mining complex in a remote, mountainous valley thousands of miles away.

Such, briefly, is the background of the Bosun Mine discovered on my grandfather’s property above Slocan Lake in the summer of 1898. It, like the ranch, was named after the Bosun, who had followed my grandfather from the Cowichan Valley to the Slocan. Throughout much of its erratic life, its owners were British. They managed a western North American silver-lead-zinc mine in the middle of my grandfather’s farm that, in its own curious way, was also a product of industrial capitalism and of exported British capital. Side by side on the same narrow terrace overlooking Slocan Lake were two very different economies, values, and ways of life. I have considered the farm and its ways. Here I provide my grandfather’s account of the discovery and early development of the Bosun Mine, and other, shorter accounts of its later development and management. I then offer some concluding comment.1

The discovery of the Bosun Mine followed directly from the discovery of the Fidelity, a mine just off my grandfather’s property to the northeast. Writing in the late 1940s, my grandfather described these beginnings as follows:

After I had bought my land I had had a most disagreeable shock. I found that my land was largely covered by two mineral claims that belonged to the hotel keeper, Jim Delayney of the Grand Central Hotel [in] New Denver. This would prevent me from getting the title to my land and I had to buy him out. These claims were pure “wildcats.”2 Not a bit of work had been done on them. Delayney wanted $700.00, and although I wanted nothing whatever to do with mining I had to buy them.3

Then a strange thing happened. Some people in Silverton had “grubstaked” a young American named Frank Byron.4 Byron had had no luck and was returning on the very last day of his grubstake when he came on a tree that had been up rooted. There was some rock thrown up, Byron struck it with his pick and saw galena ore. Just a little picking and he had exposed a whole lot of ore—lead carbonate with galena. Byron staked the ledge, naming it the Fidelity in tribute to his faithfulness in staking it for his partners as well as himself. (He could have waited a day or two, and then staked it for himself alone.)

A little work showed up a very promising ledge with a fine showing of ore. We were working away clearing land when the excited Byron came across the clearing to tell us of his great discovery. He certainly was excited. It was evident to me at once that this discovery would have a very great effect on the value of my two claims.

Byron pointed out just about where the new strike was and the direction in which he thought it was heading. I knew that one of my claims must be very near.

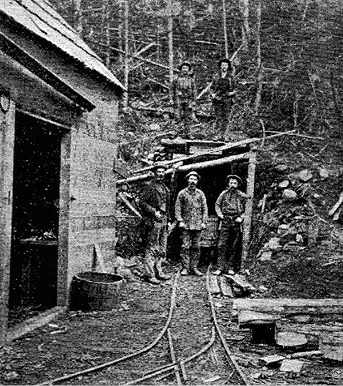

This strike caused a great deal of excitement. Only a very little work showed up a good strong, though not large vein wonderfully well situated for cheap development. All sorts of people flocked to see it and all thought it looked very promising. Poor Frank Byron nearly went crazy with excitement. He and his partners put on a small crew and their first work turned out well. They had as much as nine inches of solid galena showing and the values in silver were very good.5 A trail was made to connect with the New Denver trail and we all went up to look at the new mine. They built a cabin close to the workings and I supplied them with vegetables of course. There were about eight men there including Byron.

A man named Benedum, who was an assayer in Silverton, came up and experted the property. He made an estimate of the value of ore in the little hummock of mountain where the ore stuck out, if only the streak hung on. This talk sent Byron nearly crazy with excitement. His head swelled almost visibly. He was positively insulting to various mining men who tried to open up negotiations to buy the mine. “He had no time to talk with pikers.” He hired horses and galloped about as if his time was tremendously valuable.

They borrowed money from the Bank and put on more men. I went up one evening with a few vegetables for the cook and went to see the showing of ore. It was 28" across and practically solid galena in one place, but it was very much narrower a little lower down. They had put in two shots and were just about to shoot. I left as I had to bring up some more supplies next morning. Next morning the fine showing of ore was gone. There was only a streak of ore, from one to two inches wide. Such is mining in the small rich veins of the Slocan.

They worked with frantic haste and little judgement. They had ore that netted them about $80,000 but owed the bank $10,000 by spring. Then they leased the property to some good Cornish miners. These men did good work but had no luck. They sunk a pretty deep shaft but got hardly any ore and quit in disgust.

My grandfather, however, held two mining claims adjacent to the Fidelity, and was legally required to do development work. Although he had come to the Slocan to farm, these claims and the Fidelity discoveries drew him toward mining.

I got an old fellow who lived at the Galena Farm and who was a bit of a surveyor to find out the exact boundaries of my claim, the Tyro, and [when] we found that it was very near to the original strike of the Fidelity I hunted the mountain to find any indication of the vein. We found some rather likely looking quartz and very soon uncovered what looked like a vein. I did the assessment work, $200.00 for the two claims that I held on this showing. We got out a good deal of quartz but no ore, and the quartz tended to pinch out as we got further in. Altogether it was hard work for no encouragement. I got busy again with my garden and put in another very busy winter with the team.

When it was time to do another lot of assessment work, I got old Mr. Bartlett to make a careful survey of the workings of the Fidelity to determine the course of the vein as closely as possible. Bartlett did a very good job. We decided the direction of the vein pretty accurately, and where it should enter my claim as closely as possible. Then I got one of the best prospectors around, Ed Brennan, to work with me and put him in charge. He decided to make an open cross cut just below where the vein should enter my ground. We started at the very stake that Mr. Bartlett had set up. He worked east and I dug west. We dug an open ditch through the wash, which averaged about two feet deep. Just before the noon hour Brennan began to find “slick enside,” that is rock that has been in the wall of a vein and still shows traces of the pressure and grinding that it has gone through. I had to go to town that afternoon but I hurried back and there was Brennan with several pieces of lead carbonates (decomposed galena). After a bit more hard work, we began to show up the ledge right in place, and next day we had a very nice little showing of galena ore. It certainly was exciting work and we both felt tremendously pleased.

C. T. Cross, the rather prominent business agent in Silverton, advised me to get the owners of the Fidelity to put a price on their property; then I would do the same for mine. We would put the property in his hands and then we could probably make a fairly good sale. We had done this and though I might have liked to try developing the prospect myself, I was bound by this agreement and decided not to ask Mr. Cross to modify it. My price was $7000.00 cash down [$7,500 in most accounts].

Mr. Sandiford, an elderly Englishman from Lancashire, had come out to look for mines for an English syndicate, the North West Mining Syndicate. He had been foreman of a mine in Serbia. A carpenter by trade, he was a shrewd and capable old boy, very self assured and boastful by nature. Sandiford came up to see the showing and almost at once wanted to know the price. I referred him to Mr. Cross and the deal went through.6 We had dug two more holes in the wash farther down, and in each found the vein running strong and true with a little ore showing. Sandiford put men to work on the lower showing with the most astonishing results. The ore body got wider and wider the deeper they got. At ninety feet deep there was four feet of practically solid galena. “I knewed she was there,” old Sandiford would say to all comers, and certainly plenty of people came up to see the bonanza.

Initially, the Bosun Mine, owned in London and managed by W. H. Sandiford, was a huge success. My grandfather reported: “They took out an astonishing amount of ore for the little development required. Sandiford opened up the mine in quite good style. In fact it was very simple to anyone who understood mining. They started at the lower levels, and as soon as the wagon road (less than half a mile) was built, began to ship fine galena ore in great quantities. The very first year they paid for the mine and a dividend to the shareholders.”

The British Columbia Mining Record reported even more enthusiastically:

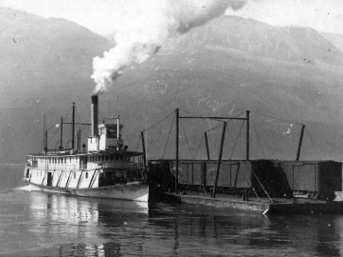

On July 4, active development began under the new company, and although employing only a few men at first, the force has been steadily increased until to-day [August 1899] it numbers over 30. Within two months of making the payment, and three of the commencement of operations, while still in the initial stage of development, shipments were begun, the first car leaving the mine [by barge on Slocan Lake] on September 6, to be followed by five others the same month, making a total of 120 tons for September, or a value of considerably more than the original cost of the property. From that time to this there has been no diminution in the productive capacity of the mine, the output being consistently maintained in the neighbourhood of 100 tons a month. In all, 9,000 tons have been shipped to date, having a net value of over $60,000, a record, I venture to assert, unprecedented in the history of mining in the Slocan and in all probability of the whole province.7

The North West Mining Syndicate built a wharf on the shore of Slocan and a short wagon road to the mine. The lake steamer, pushing a barge with several boxcars, would put in at the wharf, load the boxcars with ore, and take them, probably, to Slocan City, to which the CPR had recently opened a spur line. From there, Bosun ores went to smelters in Chicago; in Omaha, Nebraska; and even in Antwerp, Belgium. Many of the miners were put up in the two-storey log house my grandfather had just built.8 He wrote:

The opening of the Bosun Mine gave a great lift to New Denver. The town seemed at last to have a definite payroll at the back of it. To facilitate the opening up of the mine, I let the miners board at the big log house. What rough manners they had and what an amount of spitting on the floor. They used foul language so habitually that they could hardly swear; they simply had nothing worse than ordinary talk to hurl at an enemy. They were a good hearted lot, full of fun, and loved to josh each other. Cleverley did the cooking and did very well indeed.9 Even the miners did not kick, and they are desperately hard to please.

The initial success of the Bosun Mine attracted wide attention, not least for the quality of its management. The British Columbia Mining Record ended an article on the mine on this note:10

This article would be incomplete without a reference to the unique position in which the North West Mining Syndicate and its shareholders stand when compared with other companies similarly situated. Soon after the first annual meeting the directors were able to announce, with pardonable pride, the declaration of a 20 per cent dividend as a result practically of the first year’s operations. This encouraging condition of affairs was due to several causes, a brief analysis of which might serve as an object lesson to our companies who have made a failure and then attributed it to the country.

To begin with, the company under consideration has an experienced London board, composed not merely of thorough business men, but those who have had to deal with mining ventures in other parts of the world, and therefore know precisely what they are about in this instance. Secondly, and of quite equal importance, is the fact that they are not burdened with a capital so vast as to be entirely unmanageable and out of all proportion to the scale of their operations. The third factor which contributed to their success is the unlimited confidence which they reposed in their local representative, Mr. W. H. Sandiford, who had full power to act for the company in any emergency which might arise. To his foresight and judgment, acquired during some twenty-five years’ varied experience in every quarter of the globe, they owe a large measure of praise, and if there is one gratifying feature about the whole connection it is to know that his services to the country have been fully recognized by the directors and substantially acknowledged; a most excellent precedent for other companies who wish to achieve like success.

Less than a month later the Silverton Miners’ Union closed the Bosun, demanding that men employed underground should be guaranteed a minimum of $3.50 for eight hours of work. This strike, following a provincial law that reduced the hours of underground work from ten to eight hours a day, and the mine owners’ decision to reduce wages from $3.50 to $3.00 a day, shut down all the Slocan mines for the better part of a year. More serious in the longer run, the Bosun’s richest ores were near the surface, and their zinc content increased with depth. The Bosun was becoming a zinc mine. Its ores were heavily penalized by North American smelters, while the cost of shipping to Belgium became prohibitive. Nor is it clear that the manager, W. H. Sandiford, was as effective as the London board and local mining writers assumed. My grandfather painted another picture:

Sandiford was comic at first in his good fortune and very shortly tragic. He had been brought up a good Methodist, but now he quickly developed a drinking habit. His very boastful nature rendered him an easy mark for people who sponged upon him. He swallowed flattery as a cat goes for cream and could take it by the shovel full. Mrs. Sandiford was a very fine old lady, with far more sense than her husband ever had. It must have been terrible for her to watch him going to the dogs. Worse still, their son Charlie came out (very shortly after I had brought my wife).11 Charlie was a fine, fresh looking boy, and we both took great liking to him when he first came up to visit us after his arrival.

No young fellow could have had a better chance. He was well educated and very pleasing, with plenty of brains and not as boastful as his old dad. Both of the old Sandifords were tremendously proud of him, and he was made engineer to the mine and other properties which Sandiford was developing. The foolish old man started him off drinking also, and before long they were regular soaks. Men who wanted a job at the mine used to buy a bottle of whisky and give either of the Sandifords a drink or two and some flattery, and then almost certainly land the job unless the bookkeeper, Bob Thompson, took a hand, as he occasionally did, when the deal was too raw.

Whatever the accuracy of this assessment, Mr. Sandiford retained the confidence of the board in London. After the strike was settled, the Bosun reopened and remained in operation for most of the next three years, during which it was consistently among the Slocan’s principal shippers. According, however, to the British Columbia Mining Record, by September 1902 the London board was considering closing it.

The third ordinary general meeting of the Bosun Mines Limited was held in London last month. The Chairman, after paying a high tribute to the efficiency of the manager, Mr. Sandiford, explained that although the condition of the mine was excellent, it had been considered expedient to discontinue operations for a period, as the decline in lead and silver prices and the fact that the company was obliged to pay the miners a higher rate of wage, left little if any margin of profit. Recently, however, a considerable deposit of zinc-bearing rock had been encountered, and spelter [zinc alloy] being at present in great demand, it was hoped that the mine might soon again be worked. It was further stated that Mr. Sandiford had offered to accept a reduction of salary until operations were resumed, while the board agree for the meantime at least to waive their fees.12

A more definitive closing came late in 1903. The roughly 1,100 tons shipped from the Bosun that year was mostly zinc. In the hope of reducing shipping costs, the company had considered treating zinc ores at the mine, but had not succeeded in doing so. In these circumstances, the Bosun was unprofitable. There would be no shipments from it for the next fifteen years. Sandiford and his wife remained in the manager’s house for a year, then moved to Victoria. (My grandfather said that Charlie drank himself to death and Sandiford “went insane and died in the Westminster Asylum still boasting of the Bosun mine.”) A caretaker remained at the mine.

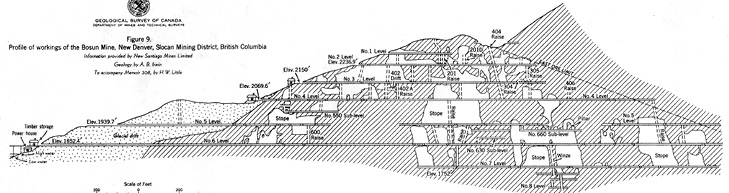

Little more than three years of work had produced a narrow industrial landscape composed largely of shattered rock from six adits (tunnels). It rose abruptly from a wharf at the lake, crossed a fairly level terrace with my grandfather’s farm on either side, and carried on several hundred feet up a mountainside—the visible record of thousands of hours of underground work. Underground were six adits, one of them almost 1,300 feet long.13

Although the Bosun Mine was closed, the company directors were still considering how to handle its zinc ores. At its sixth ordinary general meeting, in London in September 1905, they reported and recommended as follows:

Owing to the difficulties of mining conditions in British Columbia … it has long been apparent that no favourable results from working the mine would be expected without smelting at the mine itself, or mechanically concentrating the ore before shipment. The cost of a smelting plant, and the fact that the supply from one mine alone could not be sufficient to work a separate smelting plant, renders the former idea impracticable. Your directors, therefore, have been giving much attention to the possibility of concentrating the ores. There have been difficulties, however, as to erecting a concentrating plant entirely for one mine, both as regards providing for the cost and sufficiency of ore supply; but an opportunity has arisen of considering amalgamation with a neighbouring mine which has a concentrating plant now in course of erection.

As a result of somewhat prolonged negotiations, your directors have the pleasure to announce that they have concluded a provisional agreement with the Monitor and Ajax Fraction, Ltd., whereby in consideration of a certain number of shares in this latter company [26,000 ordinary shares of 1 pound each, and 6,666 deferred shares of 1 shilling each] the Bosun Mines, Ltd., will hand over its mines and property to the Monitor and Ajax Fraction, Ltd. By these means the Bosun and Monitor and Ajax interests will be worked together, and the shareholders of the Bosun Mines, Ltd., will obtain the benefit of the use of a concentrating plant.

The mines and concentrating plant of the two concerns are immediately adjacent to each other, and can be worked as one concern under the best conditions for economy, and your directors, believing this proposed arrangement to be in the best interests of the company, and as giving a probability of leading to good results, ask the general meeting to ratify the agreement.14

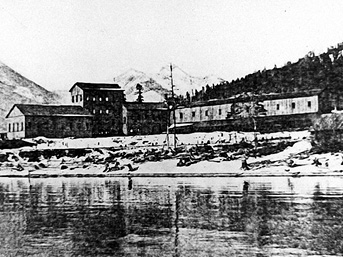

The Monitor and Ajax Fractions were just above Three Forks, close to the CPR spur line from Nakusp, and some ten rail miles from Rosebery. The Bosun was four miles away by water. All their ores carried high proportions of zinc. With a closed mine on their hands, no other option on the table, and no other information available to them, the London shareholders ratified the sale. Work proceeded rapidly on a large concentrating mill in Rosebery, while at the Bosun’s large bins were built at the wharf, and a gravity tramway built to the upper adits. Large volumes of zinc ore, some of it recovered from the mine dumps, could now be shipped to Rosebery. A year after the consolidation, the British Columbia Mining Record reported enthusiastically:

The Monitor and Ajax Fraction, Ltd., an English company operating in the Slocan district and owning the Monitor mine near Three Forks, and the Bosun mine near New Denver, and a recently completed concentrating mill at Rosebery, is planning to develop the mines named on a systematic scale. Both contain large quantities of zinc, which, under present conditions, is not favorable to active operations so the company is not mining just now. Certain improvements, found advisable, have been made to the concentrating plant, which is stated to be now working smoothly and making an average recovery of 95% of the lead 89% of the silver and 81% of the zinc content of the ore treated. During the two months it has been running when the district was visited lately, about 1,900 tons of ore had been put through the mill. Ore bins have been built on the waterfront of the Bosun property, Slocan Lake, and a gravity tramway to the mine constructed. This provision for shipping admits of the old dumps of ore being sent to the mill at Rosebery, for scows carrying four railway cars can be quickly loaded and the ore be thus cheaply conveyed to the mill. These shipping bins have a total capacity of about 400 tons and the cars can be filled from them in less than half an hour. Some development work was done last summer at the Bosun, this consisting of the extension of three adit tunnels, in each of which ore was encountered.15

Behind these plans were many untested assumptions, the most basic that the concentrating mill would work and be regularly supplied with ore. Neither proved valid. The mill did not solve the technical problem of separating zinc ores. The Monitor and Ajax Fractions closed, and in 1910 a forest fire destroyed their buildings. The Bosun did not reopen. Expected custom work did not materialize. A large concentrating mill in Rosebery stood unused and empty. Ordinary shares in the Monitor and Ajax Fraction Ltd. became virtually worthless.

Only well into World War I, and in response to high, wartime prices for silver, lead, and zinc, would the mine again become interesting. In November 1917, an American mining company, the Rosebery–Surprise Mining Company, acquired the Bosun, the Monitor–Ajax, and several other mines, as well as the concentrating mill in Rosebery. It improved the mill, and aggressively reopened the Bosun, employing some sixty-five men there through much of 1918.

The Rosebery–Surprise Mining Company operated the Bosun for a decade, during most of which the mine returned a modest profit. At any given time it employed some twenty to thirty men, and in most years shipped more than a thousand tons of ore, initially to the Rosebery concentrator where the problem of zinc ores was somewhat mitigated by high metal prices. In 1923, however, the problem was solved at the Sullivan concentrator in Kimberley, and two years later the Trail smelter, equipped with the new selective flotation technology, accepted all silver–lead–zinc ores without penalty. The Rosebery concentrator closed; Bosun ores were rerouted to Trail. At the mine, the upper workings were leased and their dumps gone over for discarded ore. The company worked the adit just above the lake, now almost 3,500 feet long, and below it, more than sixty-five feet below the surface of Slocan Lake, opened another level in 1927. These lower workings continued to show narrow veins of galena (silver–lead) ore.

In 1928 the Rosebery–Surprise Mining Company sold the Bosun Mine, which it must have considered largely worked out, to Colin Campbell, a businessman in New Denver. He managed the mine for a year, then, when a stope on the lowest adit was worked out, and with the prospect of another still lower adit beyond his means, turned the mine over to leasers and sought a buyer.

A report by the Minister of Mines described the mine:

The mine has been opened up by six adit-tunnels and one level 100 feet below the No. 6 (or lowest) adit-level. This No. 7 level is approximately 75 feet below the surface of the lake and the vein has been drifted on for some 500 feet. During 1929 a small stope in the east end of No. 7 was mined by the owner and a total of 958 tons of milling-ore was shipped to the Trail smelter. The average grade of the ore shipped has been reported as: silver, 60 oz. to the ton; lead, 20 percent; zinc, 25 percent.

The stope from which the above shipment was made played out, and in order to provide further ground for stoping operations it will be necessary to sink a shaft and start the development of a No. 8 level. This new development work has not been undertaken, efforts having been made to dispose of the property to a company which could handle the necessary development programme with considerably less risk than would be the case were the risk assumed by one man. Since August 1st, when C. J. Campbell discontinued mining operations, leasing parties are jigging the old dumps of the mine and making a product that has assayed 82 oz. silver, 22 per cent lead, and 23 per cent zinc when shipped to the Trail smelter. The remaining leasers are working underground, re-treating the old stope-fill and where possible mining any ground that is accessible and of a grade good enough to ship.16

A year later, as metal prices collapsed and the Depression deepened, all Slocan mining companies laid off their men and closed down. A little leasing continued at the Bosun and elsewhere, but the primary economy of the Slocan Valley had virtually come to a halt.

When the Bosun Mine closed down in 1930, its ore was almost gone, although leasers worked it intermittently for the next fifty years. In October 1956, there were reports that leasers had hit six to eight inches of clean ore running just over one hundred ounces of silver to the ton.17 As late as the early 1980s, one of the dumps by the lake was being picked over, and sacks of ore shipped to Trail. When the highway (BC 6) that crossed an adit began to cave in, the Department of Highways poured in many loads of ready-mix and stopped up the entrances to the adits. The hole where a stope broke the surface was filled in. Trees began to grow on the dumps. The Bosun Mine had come and gone, its best years 1898 to 1899, its early life short, and a measure of order established only during a long decade after 1917.

The records reveal almost nothing of the miners or of their working conditions, though my father once said that there probably was so much salvageable ore on the dumps because angry miners chucked it there. On the other hand, the records provide a fair picture of the changing ownership, management, and productivity of the mine as capital reached aggressively into a corner of the Slocan Valley, there to create an industrial slice through the middle of my grandfather’s farm.

The early mine was owned in England, managed indirectly by a board in London, and on the ground by a manager (Sandiford) appointed by the board. For all the vaunted experience and “precise knowledge” of the business and mining men who comprised the board, they knew next to nothing of British Columbia, nor of western North American hardrock mining, nor of the particular geology of the Bosun. Although the board was, in principle, the centre of calculation of the whole system, in fact it had little information to work with, and what it had came from the mine manager who, like most managers, couched reports to his superiors as favourably as possible. The board had little choice but to trust Sandiford; moreover he had recommended the purchase of the Bosun, and its initial development was spectacular.

The Bosun’s story, however, was common in the Slocan: rich ore, close to the surface and easily worked, then declining yields with depth. Nor was the board equipped to deal with silver ores with a high percentage of zinc, a smelting problem that, at the beginning of the twentieth century, was unresolved throughout North America. Probably Sandiford was neither as good as the board nor as inadequate as my grandfather thought he was; the problem was the mine, its ores attractive enough to draw speculative English investment, but not to sustain it.

The scheme to sell the Bosun to Monitor and Ajax Fraction Ltd. was even more risky. It made some abstract sense from afar: an integrated system comprising a concentrating mill built to handle zinc ores, and mines nearby known to be heavy zinc producers. But the mill hardly worked and the mines did not ship. Under English management, the Bosun was profitable for only a few initial months. Overall, the North West Mining Syndicate and Monitor and Ajax Fraction Ltd. were the means by which a good deal of English capital was transferred overseas and lost. Its residue was in the effects of wages paid and goods purchased, in idle mine workings, and in a large, empty, concentrating mill in Rosebery.

The Rosebery–Surprise Mining Company that purchased the Bosun in 1917 may have been better managed—it is impossible to know from the records at hand—and certainly benefited from higher metal prices and accessible smelting. Prices for silver, lead, and zinc, pushed up by the war, remained relatively high through the 1920s. Moreover, the problem of zinc ores was solved by 1925, when such ore could be shipped to Trail, not far away. There seems a certain shrewdness in the Rosebery–Surprise operation, particularly the decision to sell in 1928 when prices were robust and the mine appeared to be nearing the end of its life. In fact, by 1928 when C. J. Campbell bought the mine, the Bosun’s years were largely over, less because of the Depression, decisive as it was for a time, than because there was little left to mine. In a span of just over thirty years, during barely half of which the Bosun was an active mine, industrial capital had plucked a valuable resource, removing it permanently from the valley.

Richard White, a prominent American environmental historian, has argued that a mania of late-nineteenth-century railroad construction in the American West resulted in far more miles of track than were needed; in fortunes for a few railroad barons, often at the expense of the companies they ran; in abnormally low commodity prices (because of the glut of primary resources coming on market); and in settlements on difficult land where pioneers faced only hardship.18 He holds that there were alternatives, and that the American West did not have to be developed as rapidly as it was. There was an opportunity, he suggests, for a very different outcome.

Such a claim had long preoccupied my grandfather. In general, he thought different outcomes were possible, but only if cooperation replaced greed, and if wise, centralized planning replaced reckless speculation (see chapter 6). He thought British Columbia had built far too many miles of railroad, and had surveyed and opened up far too much land for settlement before older areas were adequately populated and developed. He advocated the public ownership of most of the means of production. But he was a booster of mines. He had long argued that undeveloped mining claims should be taxed more, and developed claims less. Moreover, for purposes of taxation, owners should assign their claims an assessed value, after which anyone willing to pay this price plus 5 percent could purchase them.

In these ways, undeveloped claims held as speculations—the curse, as he saw it, of any mining district—would come on the market, and low taxes would encourage their development. As a farmer who had intended to supply the mines, it was in his interest to support them. At the same time, he believed in the public ownership of the means of production and, partly by this means, in a cooperative society. Yet in all his political writings I find no direct reference to the nationalization of mines. Perhaps he recognized how difficult this would be, partly because the whole ethos of the speculative mining rush that had developed the modern Slocan contradicted his managed, cooperative vision, partly because the small, rich, uncertain Slocan mines, of which the Bosun is a good example, were particularly poor candidates for nationalization. Moreover, in the 1930s, when these issues came most insistently to the fore, all the Slocan mines were closed.