Writing to his wife in Kansas, General William H. Larimer, the self-proclaimed founder of Denver, blustered that “Everyone will soon be flocking to Denver for the most picturesque country in the world, with fine air, good water, and everything to make a man happy and live to a good old age.”

Colorado State Capitol.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

A natural-born finagler, Larimer had actually claim-jumped a little settlement established in 1858 by a party of Georgia prospectors who found a few flakes of gold in Cherry Creek. Hoping to curry political favor, he named the fledgling town after territorial governor James Denver, unaware that the governor had already resigned. Realizing that the place needed links to the civilized world, he bribed a stagecoach company to establish its headquarters there. Faced with competitors from three nearby settlements, each vying for recognition as the territorial capital, he bought them off with a barrel of whiskey.

Like the gold fields that spawned it, Denver was a gamble. It lacked most of the basic requirements of a city, such as a navigable waterway, and was isolated by hundreds of miles of dry, treeless prairie. Its own gold deposits proved paltry, and when a huge strike was reported at Central City, the town was nearly deserted. A catastrophic fire in 1863, a flash flood in 1864, and Indian hostilities in the late 1860s nearly wiped it out. It seemed Denver’s fate was sealed when the Union Pacific bypassed Colorado in favor of a transcontinental route through Cheyenne, Wyoming. Larimer, failing to become the mayor of Denver or the governor of Colorado, abandoned the place.

Bronco Buster sculpture, Civic Center Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Rail hub

But Denverites were not so easily defeated. They raised funds and donated labor to build their own railroad, the Denver Pacific, which in 1870 was linked to the Cheyenne line. Not long after, the Kansas Pacific reached town, and Denver became the hub of a rail network that stretched in all directions. The railroad brought gold, minerals, and coal to the town’s smelters, agricultural products from the plains, and immigrants from Europe. In 1878, Leadville mines yielded the richest silver strikes in the nation’s history, and Denver once again was at the crossroads of a prospecting frenzy. By 1900, 100 trains a day steamed in and out of Union Station.

We were here, too

The Black American West Museum (3091 California Street; tel: 720-242-7428; www.blackamericanwestmuseum.org; Tue–Sat 10am–5pm) was founded by Paul W. Stewart, who as a child had been told that there were no black cowboys. In fact, nearly a third of cowboys in the American West were black, and when Stewart grew up he met one who had led cattle drives at the turn of the 20th century. To set the record straight, Stewart set about compiling this eye-opening collection of artifacts, oral histories, and documents that tell the story of black Western heroes such as Nat Love (alias Deadwood Dick), mountain main James Bekwourth, as well as other African-American pioneers who became miners, ranchers, military heroes, and millionaires.

Other hardships befell the fledgling city, as the cycle of boom and bust alternately yielded riches and ruins. Through it all, Denver kept its nose to the grindstone, diversifying into light manufacturing, military facilities, aviation, energy and, in recent years, high-tech industries. In 2015, Denver’s estimated population was 682,545, making it the fastest-growing major city in the nation. Ironically, many people are relocating here from California in a kind of reverse migration.

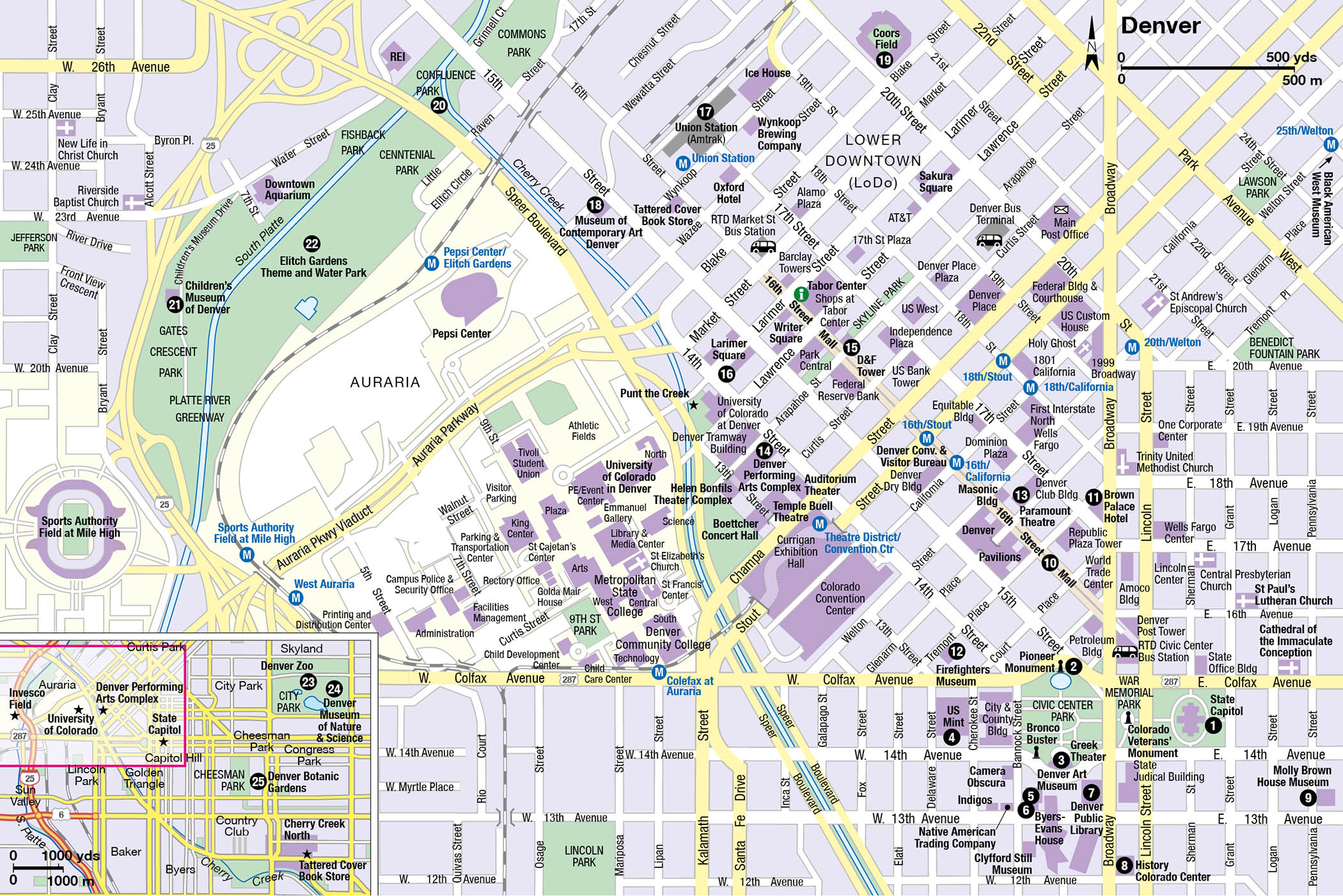

Mile-high sightseeing

Start your tour of Denver at one of the city’s most photographed spots – the 18th step of the Colorado State Capitol [map] (203 E. Colfax Avenue; tel: 303-866-2604; Mon–Fri 7.30am–5pm; free tours every 45 minutes), where a plaque informs visitors that they are standing one mile above sea level. Patterned after the US Capitol, the Colorado State Capitol is built in the shape of a Greek cross, with Corinthian columns, a central rotunda, and other neoclassical features. Construction of the 18-story structure began in 1886 and took 22 years and nearly $3 million to complete. All the stone used in the building – granite, sandstone, marble – was quarried from locations around the state. The crowning glory is the dome, wrapped in gold leaf donated by Colorado miners in 1908.

The dome of the capitol in Denver is covered in real gold leaf.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

The interior is equally impressive, with stained-glass portraits of Colorado pioneers, and murals chronicling key moments in state history. The rose onyx wainscoting is from Beulah, Colorado, and is the world’s entire supply of this rare stone. Four full-time employees are responsible for polishing the ornamental brass railings around the rotunda. From the third floor, you can climb 93 steps to the dome’s observation deck for a panoramic view of the city.

Descend the front steps of the Capitol, pass the red sandstone Colorado Veterans Monument, and cross Civic Center Park. To the far right, the Pioneer Monument 2 [map] commemorates the end of the Smoky Hill Trail, a stage road connecting Denver with the Missouri River. The fountain, which depicts a pioneer mother, a miner, and a trapper, sparked some controversy when it was erected in 1911; a figure of an American Indian that originally topped the piece was replaced with a statue of frontiersman Kit Carson.

On the south end of the park is the lifelike Bronco Buster (1920), a statue by Alexander Proctor. The cowboy Proctor used as a model was arrested for horse rustling after posing for the artist. Nearby, the open-air Greek Theater 3 [map] (1919) is used for a variety of performances and public gatherings; it is adorned with murals by Alan True, whose work is also found in the Capitol. Bracketing the park on the west side is the grand semicircular City and County Building, a government building completed in 1932.

Denver Public Library.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Behind the City and County Building is the United States Mint 4 [map] (320 W. Colfax Avenue; tel: 303-405-4761; Mon–Thurs 8am–3.30pm; free tours by reservation only). One of only two mints in the United States, it churns out $6 million daily in small change, a total of 52 million coins, about 40 percent pennies.

Tip

US Mint tours are by reservation only, but standby tickets due to no-shows and returns are sometimes available on a first-come, first-served basis on the day of the tour. Check at the information booth on Cherokee Street at 7.30am.

About three blocks away, just south of Civic Center Park, is the Denver Art Museum 5 [map] (100 W. 14th Avenue; tel: 720-865-5000; www.denverartmuseum.org; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm, until 8pm on Friday). The original North Building was designed by Gio Ponti in 1971.

The Hamilton wing of Denver Art Museum, designed by Daniel Libeskind.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

The spectacular Frederic C. Hamilton Building, a recent extension, has doubled the size of the museum, creating much-needed space for more than 40,000 works of pre-Columbian, Spanish Colonial, Asian, and modern American and European art. The collection of Western and Native American art is incomparable, with objects representing tribes throughout North America and works by such Western masters as George Catlin, Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and Alfred Jacob Miller. Designed by celebrated Polish-born architect, Daniel Libeskind, the building is covered in 9,000 titanium panels that reflect the Colorado sunshine and recall the peaks of the Rocky Mountains and the geometric rock crystals found in the foothills near Denver.

Another landmark art museum building sits nearby. It houses the 2,000-piece private personal collection of works by famed American Abstract Expressionist artist Clyfford Still, which was bequeathed to the city of Denver by his widow in 2004. The $7 million Clyfford Still Museum (1250 Bannock St; tel: 720-354-4880; Tues–Sun 10am–5pm, until 8pm Fri) which opened in November 2011, consists of a 28,500-sq-ft (2647 sq meter), two-story, poured-concrete building, with a cantilevered lobby leading to open-plan galleries displaying works by Still made between the 1920s and 1979.

Behind the Denver Art Museum is the historic Byers-Evans House Museum 6 [map] (1310 Bannock Street; tel: 303-620-4933; Tue–Sun 10am–4pm; half-hour guided tours), built in 1883 by Rocky Mountain News founder William Byers and later purchased by businessman William Gray Evans. A 30-minute guided tour is preceded by a film detailing the history of these prominent families. Visitor numbers are limited, so arrive early if you haven’t booked in advance. The former carriage house contains the Denver History Museum, which chronicles the development of the city from the gold rush to World War II.

Across the courtyard from the museum is the Denver Public Library 7 [map] (10 W. 14th Avenue; tel: 720-865-1111; www.denverlibrary.org), housed in a distinctive contemporary building designed by architect Michael Graves and Denver firm Klipp Colussy Jenks DuBois. This is the largest library between Chicago and Los Angeles and contains the highly regarded Western History Collection of rare books, maps, and photos. A Western gallery is on the sixth floor; changing exhibitions are on the eighth.

The newly built History Colorado Center 8 [map] (1200 Broadway; tel: 303-447-8679; www.historycoloradocenter.org; Mon−Sat 10am–5pm, Sun noon to 5pm) opened in late 2011, replacing the old Colorado History Museum. State-of-the-art, hands-on exhibits range from Ancient Puebloan artifacts and Plains Indian art to mining equipment and memorabilia belonging to ill-fated silver king Horace Tabor.

It’s a six-block walk through the Capitol Hill neighborhood to the Molly Brown House Museum 9 [map] (1340 Pennsylvania Street; tel: 303-832-4092; www.mollybrown.org; Tue–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun noon–5pm), former home of the celebrated Margaret Brown, survivor of the Titanic disaster and subject of the popular musical and film The Unsinkable Molly Brown. A costumed guide recounts Margaret’s rags-to-riches story as you tour the 1889 Queen Anne–style residence. Never fully accepted by high society, Margaret was self-educated, spoke five languages, and was an avid campaigner for women’s and children’s rights. Ironically, she was never known as Molly during her lifetime. Meredith Willson, the musical’s composer and lyricist, bestowed the name upon her because he thought it would be easier to sing.

The “unsinkable” Molly Brown.

Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

In the early 1980s, a mile-long stretch of 16th Street between Broadway and Market Street was bulldozed to make way for the 16th Street Mall ) [map]. This popular thoroughfare – pedestrian-only except for free shuttle buses – launched the revitalization of downtown Denver. Today, the Mall, which was designed by famed architect I.M. Pei, is one of the liveliest urban spaces in the state. In summer, its shady central boulevard comes alive with bubbling fountains and some 50,000 flowers, and folks lounge on benches and at outdoor cafés or play chess under the trees.

Tip

The small but highly regarded Museo de las Americas (861 Santa Fe Drive; tel: 303-571-4401; www.museo.org; Tue–Sat noon–5pm) south of downtown is dedicated to Latino culture, ranging from Pre-Columbian civilizations to contemporary works.

Starting near the top of the Mall, at 16th Street and Tremont Place, is the glitzy Denver Pavilions, a two-block-square, open-air complex of shops, restaurants, and movie theaters linked by the “Great Wall,” a neon-lit, upper-story marquee that straddles Glenarm Place with its signature DENVER sign.

A block from the Mall is the landmark Brown Palace Hotel & Spa ! [map] (tel: 303-297-3111; www.brownpalace.com), which stands on a triangular lot at 17th and Tremont. The hotel was built by Henry Cordes Brown, a carpenter-turned-entrepreneur who settled in Denver in the 1860s. Brown donated land for the Capitol, then made a fortune selling off his property on Capitol Hill. But he reserved the three-sided pasture where he grazed his cow to build a grand hotel. Designed in Italian Renaissance style by Frank E. Edbrooke, architect of the State Capitol and much else, the hotel was completed in 1892 at a cost of $1.6 million after four years of construction. It was worth every penny. The Palace rivaled the splendor of the finest eastern hotels, impressing guests and residents alike with its red granite and sandstone facade, soaring eight-story atrium, golden onyx pillars, and stained-glass ceiling. Luminaries such as Theodore Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, and Harry Truman were frequent guests. Even if you can’t stay here, don’t pass up an opportunity to see the lobby, join a historical tour (Wed and Sat at 3pm), or enjoy the sumptuous afternoon tea.

The grand atrium of the Brown Palace Hotel, designed by architect Frank Edbrooke and completed in 1892.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

If time permits, consider another detour on Tremont Place for a self-guided tour of the Denver Firefighters Museum @ [map] (1326 Tremont Place; tel: 303-892-1436; www.denverfirefightersmuseum.org; Mon–Sat 10am–4pm). The museum is set in a historic firehouse and displays an array of steam pumpers, fire trucks, and other equipment dating back to the 1860s. Children can try on firefighting equipment and slide down a pole.

The Masonic Building (1889), also by Frank Edbrooke, stands at Welton Street. Gutted by fire in 1985, its stone facade was rescued by erecting a new steel skeleton within. Next door, the Kittredge Building (1891) houses the Paramount Theatre £ [map] (1621 Glenarm Place; tel: 303-623-0106; www.paramountdenver.com), Denver’s only surviving movie palace, which opened in 1930. It’s worth catching a performance, if only to view the Art Deco interior.

Two blocks farther on, a detour to the left leads to the Denver Performing Arts Complex $ [map] (1400 Curtis Street; tel: 720-865-4220; www.artscomplex.com). Encompassing four city blocks and eight theaters, it is the world’s largest center of its kind under one roof – an impressive glass arch 80ft (24 meters) high and two blocks long. Drama, musicals, cabaret, opera, ballet, and concerts are staged here.

Larimer Square.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

At Arapahoe Street the view opens onto distant mountains. On the right is one of the city’s oldest landmarks, the Daniels and Fisher, or D&F, Tower % [map] (1601 Arapahoe St tel: 303-293-0075). Colorado’s first “skyscraper” is 330ft (100 meters) tall – 375ft (114 meters) to the top of the flagpole – and was the highest building west of the Mississippi when it was completed in 1909. Modeled after the campanile in St Mark’s Square in Venice, the tower has its original clockworks, thought to be the largest of their kind in the country. The weights are wound by hand several times a week. The lobby displaying the mechanism is open to the public, and the five floors are home to loft residences and often used for parties, weddings, and corporate events.

Rest in Skyline Park, a leafy plaza rescued from neglect by an ambitious redevelopment plan in 2003. On the next block is the glass-walled Tabor Center, a lively shopping mall with more than 50 retailers and restaurants, wandering entertainers, and a visitor information booth. Opposite is Writers Square, a complex of shops, offices, and apartments built around a central plaza.

Cut through Writers Square to Larimer Square ^ [map], a block of restored Victorian-era buildings on Larimer Street between 14th and 15th streets housing restaurants and shops. The Granite Building at 1228 15th Street stands on the site where General William H. Larimer built his log cabin, using coffin lids for doors. Western legends like Bat Masterson and Buffalo Bill Cody also had Larimer Street addresses at one time or another during their Western sojourns.

On the north side is the square’s trendiest hangout, The Market at Larimer Square, where you can soak in the scene over coffee, pastries, sandwiches, or ice cream. Some of Denver’s best restaurants can be found here, including award-winning Rioja, a top destination for foodies. Horse-drawn carriages depart from the Square for rides along the 16th Street Mall.

LoDo

Anchoring the restored Lower Downtown (or LoDo) on Wynkoop Street is Union Station & [map], built in 1881 and still serving as a railroad terminal. Amtrak runs two cross-country lines through Union Station as well as the weekend Ski Train to Winter Park. Modern restaurants have been added to the wings, but the central waiting room is still a vision from an Edward Hopper painting, with tall-backed wooden benches, overhead reading lights, and arched windows.

The LoDo District

The restoration of Larimer Square in the 1970s started a revitalization movement that culminated some 25 years later with the resurrection of a blighted warehouse district known as Lower Downtown, or LoDo. Encompassing about 25 square blocks from Larimer Street to Union Station, and Cherry Creek to 20th Street, LoDo contains a remarkable concentration of early 20th-century industrial buildings. During its heyday, LoDo was a bustling commercial district full of sprawling warehouses and showrooms that were the forerunners of modern department stores.

Denver was a major rail center, and the warehouses were packed with goods for distribution throughout the West. By the early 1990s, however, LoDo had been all but abandoned – a haven for drug dealers and the homeless that was strictly off-limits after dark. All that changed in 1995 with the opening of the 50,000-seat Coors Field baseball stadium at Blake and 20th streets. Suddenly thousands of people were trooping through LoDo, and their potential custom sparked the regeneration of the neighborhood. Within five years, LoDo went from having no taxpaying residents to about 5,000, a number that has grown steadily ever since. Dozens of bars, restaurants, and brewpubs, as well as some 30 galleries, keep the place buzzing year-round, though summer evenings – when the young and beautiful go club-hopping – tend to be the liveliest.

Next to the station, the 1903 Ice House, a former cold storage plant for the Littleton Creamery, is said to have stored furs and corpses as well as dairy products. The spooky basement level lends credibility to the tale, but otherwise the building sports a smart lobby, a restaurant, and a deli. Across the street, the Wynkoop Brewing Company, Colorado’s first brewpub and a LoDo pioneer, occupies the beautiful turn-of-the-20th-century J.S. Brown Mercantile. Around the corner, at 17th and Wazee streets, is yet another Frank Edbrooke creation, the Oxford Hotel, built in 1891 and embodying all the grand aspirations of Colorado’s silver boom.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Denver * [map] (1485 Delgany Street; tel: 303-298-7554; www.mcadenver.org; Tue–Wed noon–7pm, Thurs noon–9pm, Fri noon–10pm, Sat–Sun 10am-5pm) houses works by modern masters such as British artist Damien Hirst. The building itself is a work of art, a sustainable structure on a former brownfield site that has won gold LEED designation for its sustainable construction. It was designed in 2006 by Tanzania-born David Adjaye, one of Britain’s leading architects, and contains five galleries, a store, a café, and a lecture hall.

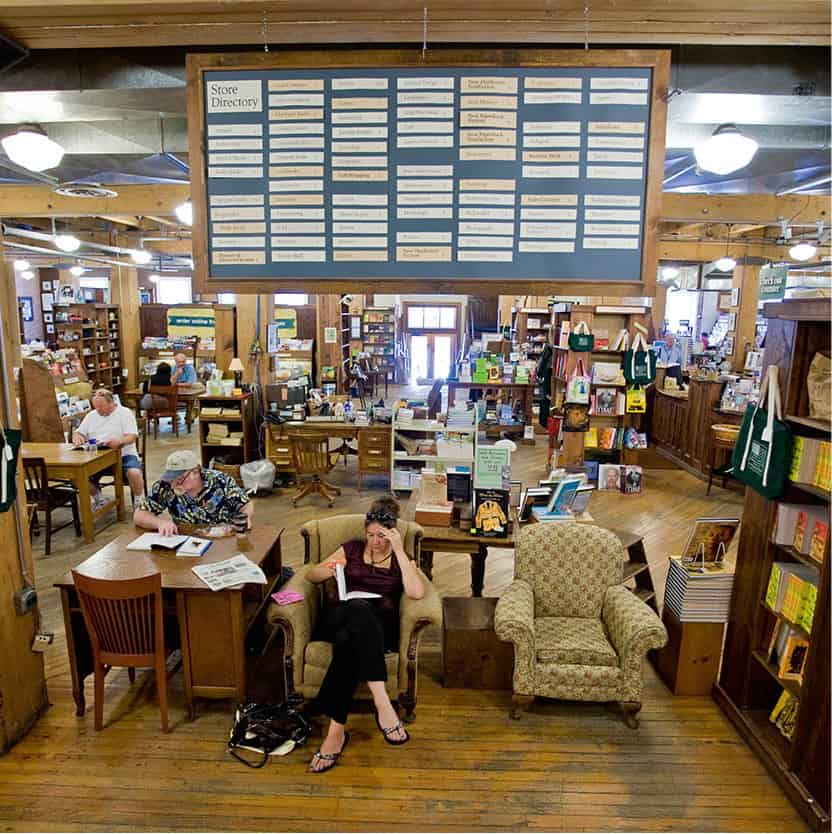

Tattered Cover Bookstore

Denver’s Tattered Cover Bookstore is one of the West’s great independent bookstores. The historic LoDo store (1628 16th Street; tel: 303-436-1070; Mon–Fri 6:30am–9pm, Sat 9am–9pm, Sun 10am–6pm) occupies two cavernous floors of the former Morey Mercantile building. The Colfax Avenue Store (2526 East Colfax Street; tel: 303-322-7727; Mon–Sat 9am–9pm, Sun 10am–6pm) is located in the historic Lowenstein Theater and contains some 150,000 titles, an extensive news stand and reading nooks with comfy chairs. There is now third branch in Aspen Grove (7301 S. Santa Fe Drive, Littleton; tel: 303-470-7047; Mon–Sat 9am–9pm, Sun 10am– 6pm), and branches in Union Station and Denver International Airport. All three branches have cafes. Call for author reading schedules and other information.

On the north side of LoDo is Coors Field ( [map], home of the Colorado Rockies. Opened to much acclaim in the mid-1990s, the $215 million stadium was designed in the spirit of the classic ballparks of the 1940s and 1950s. The Sandlot Brewing Company, owned by the corporate giant that sponsors the park, provides appreciative fans with specialty beers.

A three-block walk from the stadium is the small Japanese enclave of Sakura Square (19th and Larimer streets). During World War II, when people of Japanese descent faced hostility in the United States, Governor Ralph Carr welcomed them to Colorado. A bronze bust honors his memory. The Pacific Mercantile Company, which sells Asian foods and gifts, opened here in 1942. Otherwise, there’s not a great deal of interest for tourists.

The Tattered Cover Bookstore.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

South Platte Valley

Due west of LoDo, where Cherry Creek flows into the South Platte River, is Confluence Park , [map]. Kayakers can often be seen testing the rapids above the confluence, and kayaks can be rented on nearby Platte Street. For decades this stretch of the South Platte was an industrial wasteland – polluted, cluttered with trash, and prone to flooding. A reclamation project launched in the 1970s has worked a marvelous transformation, and today the river front is a popular public space, with some 12 miles (19km) of biking trails, picnic areas, and even wetlands where native species like beaver thrive.

The Children’s Museum of Denver ⁄ [map] (2121 Children’s Museum Drive; tel: 303-433-7444; www.mychildsmuseum.org; Mon, Tues, Thurs, Fri 9am – 4pm, Wed 9am7:30pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm) has interactive exhibits that encourage kids to play the role of storyteller, artist, scientist, and more. An outdoor challenge center gives children an opportunity to try skating, snowboarding, and skiing in safety. Outside the museum is a stop for the Platte Valley Trolley, an open-air streetcar reminiscent of those operated by the Denver Tramway Company in the early 20th century. It follows a scenic route along the South Platte on railroad tracks dating to the 1890s.

Across the river is Elitch Gardens Theme and Water Park ¤ [map] (2000 Elitch Circle, I-25 and Speer Boulevard; tel: 303-595-4386; www.elitchgardens.com; open daily April–Oct, June–Aug 10am–7pm, until 10pm on weekends, hours vary in Apr, May, Sept, and Oct). The park was originally located in northwest Denver, where in 1890 John and Mary Elitch started a “pleasure garden” in an orchard. Moved to a much larger site on the South Platte in 1995, it currently has four steel and wooden roller coasters and eight other thrill rides, including the highest free-fall drop swing in Colorado and a whitewater rafting ride, a 300ft (90-meter) observation tower, a 100ft (30-meter) -high Ferris wheel, and a 10-acre (4-hectare) water park.

The large soda-can-shaped building near Elitch Gardens is the Pepsi Center, a top concert venue and home of the Colorado Avalanche hockey team. Invesco Field, where the Denver Broncos play soccer, is on the opposite side of the river, off I-25.

City Park

With more than 6,200 acres (2,509 hectares) of traditional parks and parkways, including 2,500 acres (1,012 hectares) of urban natural land, more than 300 acres (121 hectares) of parks, designated rivers and trails, and an additional 14,000 acres (5,666 hectares) of spectacular mountain parks, Denver has one of the largest municipal park systems in the United States. One of the oldest is City Park, created in 1881 when 314 acres (127 hectares) of sagebrush were transformed into a sanctuary of green lawns and rose gardens. Denver Zoo ‹ [map] (2300 Steele Street; tel: 720-337-1400; www.denverzoo.org; daily 10am–5pm, extended summer hours) was founded here a few years later. Its first exhibit was an orphaned black bear named Billy Bryan, who was tethered to a tree. Bear Mountain, built in 1918, was the first naturalistic habitat – an enclosure without bars – an idea that wouldn’t catch on at other zoos for another 50 years. Today, the zoo is home to about 3,500 animals representing more than 650 species. Among the zoo’s highlights are the Primate Panorama, a habitat for some 29 primate species, ranging from pygmy marmosets (which weigh as much as an airmail letter) to 600lb (270kg) lowland gorillas; Tropical Discovery, a simulated rain forest; and a pack of Arctic wolves.

On the east side of the park is the Denver Museum of Nature and Science › [map] (2001 Colorado Boulevard; tel: 303-370-6000; www.dmns.org; daily 9am–5pm; charge), the fifth largest natural history museum in the United States. Exhibits cover familiar territory – mummies, meteorites, totem poles, tepees, wildlife dioramas, and much else. Where the museum really excels is in the field of paleontology. Prehistoric Journey, an exhibit on the third floor, chronicles 3½ billion years of life on earth. The highlight is a collection of dinosaur fossils, including an 80ft (24-meter) long Diplodocus and an Allosaurus and Stegosaurus engaged in battle. In the next room is a diorama of a nightmarish creature known as a Dinohyus, nicknamed the “terminator pig,” stalking its prey about 20 million years ago. The museum is also home to the Gates Planetarium, which features daily star shows, and the Phipps IMAX 3D Theater.

Dinosaur exhibit at the Museum of Nature and Science’s Prehistoric Journey.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Denver Botanic Gardens fi [map] (1007 York Street; tel: 720-865-3501; www.botanicgardens.org; daily 9am–5pm, summer until 9pm) is one of the top botanical gardens in the country. It encompasses 24 acres (10 hectares) planted with over 16,000 examples of more than 250 plant species at its York Street gardens and two satellite locations: Chatfield, a picturesque nature preserve along the banks of Deer Creek, and Mount Goliath, which showcases alpine tundra. The Boettcher Memorial Tropical Conservatory is housed in the only major tropical conservatory in the Rockies. For the best view, ascend to the overhead platforms on an elevator disguised as a banyan tree. Plants from all over the world are featured in 30 outdoor gardens, including a Japanese garden with a teahouse and the Monet Garden, with flowers and water lilies inspired by the canvases of French Impressionist painter Claude Monet. Colorado native plants take pride of place in gardens of rare wildflowers, alpine species, medicinal plants used by American Indians, and heirloom varieties brought to Colorado by Anglo pioneers. Special events are held throughout the year, including summer garden strolls and a concert series. WiFi is available throughout the botanic gardens, so you can work online and enjoy the outdoors.

Denver Botanic Gardens.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications