The southwestern region of Colorado is quite different in appearance and feeling from elsewhere in the state. Politically, it’s an anomaly: the unique conjunction of four states – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona – in an area known as the Four Corners. Geographically, it’s the boundary between two geologic provinces: where the Southern Rockies bump up against the 130,000-sq-mile (340,000-sq-meter) Colorado Plateau, a mile-high uplift carved by wind and water into mazelike canyons, crumbling mesas, and ebony-hued volcanic crags. But most of all it’s a meeting place of cultures, both ancient and modern, with roots reaching far back into prehistory.

People have hunted, gathered, and farmed on the mountains, river valleys, and mesa tops of southwestern Colorado for thousands of years. Nowhere is this more evident than at Mesa Verde National Park, which, since 1906, has preserved 4,400 archeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings, built by the ancestors of today’s Pueblo people, between AD 550 and 1300, atop a verdant mesa in the Mancos Valley. Thousands more sites lie on the adjoining Ute Mountain Ute Reservation and the surrounding Great Sage Plain. Mesa Verde National Park, Hovenweep National Monument, and Canyons of the Ancients National Monument are all part of the longer Trail of the Ancients, a scenic byway that winds through the Four Corners, visiting Indian reservations, museums, parks, archeological centers, and miles of extraordinary scenery.

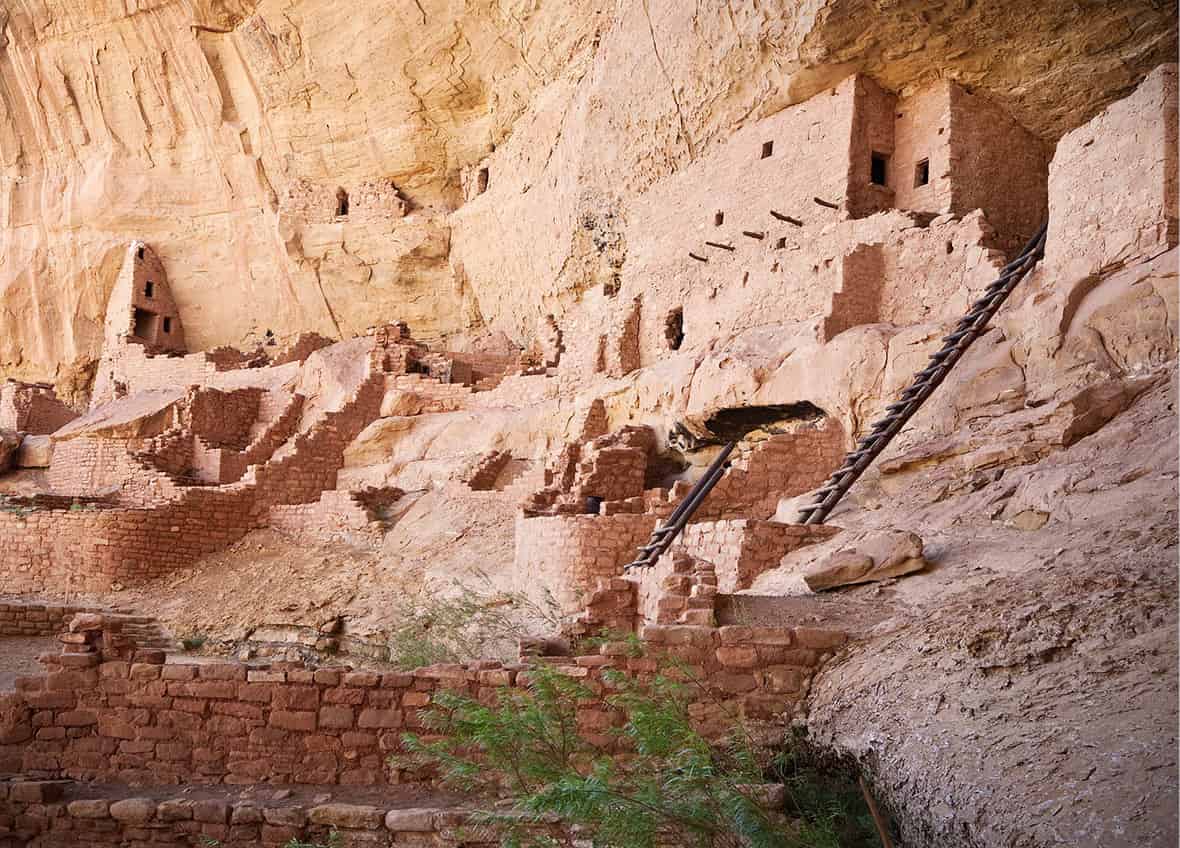

Cliff House at Mesa Verde National Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Anasazi Heritage Center.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Cortez

The trail begins in the small ranching and farming town of Cortez 1 [map], a convenient base for exploring the area and well supplied with visitor facilities. Your first stop should be the Cortez Cultural Center (25 N. Market Street; tel: 970-565-1151; www.cortezculturalcenter.org; Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, Indian dances 7pm Mon, Wed, Fri), run by the University of Colorado. Housed in a 1909 historic building in the frontier-style downtown, the center has a museum, art gallery, and gift shop and is a great place to get oriented to the area. Newly expanded, its museum has interpretive exhibits on the Basketmaker and Ancestral Pueblo people who lived in the Four Corners for 1,300 years, as well as some of the area’s best interpretation of the contemporary Navajo and Ute Mountain Ute tribes, whose reservations lie to the south. Cultural presentations between Memorial Day and Labor Day include Native American storytelling and lectures, dances, and day tours to archeological sites.

Ancient dwellings

Foremost among the archeological sites in the area is, of course, Mesa Verde National Park 2 [map] (tel: 970-529-4465; www.nps.gov/meve; year-round). Mesa Verde was the first national park to be set aside to preserve the works of mankind and remains a favorite with visitors, who regularly vote it America’s top national park. Mesa Verde lives up to the hype. In few places in the Southwest do the works of man blend with a natural landscape of such beauty and rich resources. Moreover, it’s a large park – some 54,000 acres (22,000 hectares) spread over the fingerlike Chapin and Wetherill mesas – and there’s a lot more here than Cliff Palace, which was discovered in 1888 by the Wetherill brothers.

Far View Lodge

If you want to splurge on a luxurious hotel room and a special dinner while visiting Mesa Verde National Park, Far View Lodge might just be the place (tel: 800-449-2288; mid-April–mid-Oct, reserve well ahead). Located across the street from the visitor center, the lodge looks like a plain motel from the outside, but don’t judge too quickly. Every room has an extraordinary view of the San Juan Basin as well as a private balcony where you can enjoy the drama of the sudden summer thunderstorms that sweep across the desert. The Metate Dining Room has equally stunning views. The restaurant serves New Southwest cuisine featuring elk, bison, trout, and other local delights – definitely a cut above standard park fare.

For starters, there are numerous mesa-top pithouses – the semi-subterranean homes of the Basketmakers, the ancestors of the Ancestral Pueblo people who began to congregate in above-ground pueblos in the 700s. There are traces of fields, too, where residents once grew large quantities of corn, beans, and squash. Standing in the cliff dwellings, you can just make out the chiseled toeholds in the vertical cliffs, where people once climbed up to their fields and down into the canyons to hunt mule deer, rabbits, and other game. Mesa Verde’s success stemmed largely from the people’s skill in using all of the resources of their land and in their adaptation of new technologies, such as agriculture, basketweaving, and pottery, learned through contact with people from the south.

Long House, the second largest cliff dwelling at Mesa Verde, was occupied for about a century by 150−175 people.

Aramark Parks and Destinations

Still, you have to wonder, what would it be like to spend a particularly snowy January here? Despite Mesa Verde’s pronounced southward tilt and abundance of moisture, winter night-time temperatures, even in a south-facing pueblo, can’t have been comfortable. Visit here in winter, and you’ll find out. Although Cliff Palace, Balcony House, and the ruins along the 12-mile (19km) Wetherill Mesa Road are closed, the Ruins Road on Chapin Mesa is kept clear year-round. Chances are you will have many of the ruins all to yourself.

This is when Spruce Tree House A [map], the park’s second largest ruin, located behind Park Headquarters and Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum B [map] (daily Apr–Oct 8.30am–6.30pm, Nov–Mar 9am–5pm), comes into its own. Warm and dry under the overhang in winter, you can linger in this lovely side canyon in the park’s best-preserved and most accessible ruin, watching rufous-sided towhees scratching in the duff below pinyon pines laden with snow. The spirits of the Ancestral Pueblo people feel close at hand. You can easily imagine them, robed in warm cloaks of hide and feathers plucked from domesticated turkeys, anxiously observing the movements of the sun, moon, and planets for signs of the winter solstice and warmer days ahead. At the time of writing, Spruce Tree House is closed for geological tests due to safety concerns following a rockfall in 2015. An overlook near the museum offers superb views, however. Be sure to check out the museum before leaving. It’s a great place to view distinctive black-on-white pottery, bone and wood tools, yucca sandals and clothing, and other Ancestral Puebloan artifacts.

Tip

In summer, try to sign up for the 9am tour of Cliff Palace, the first tour of the day. You will avoid tour bus crowds, and the relative quiet awakens the imagination about life here centuries ago.

Far View

In summer, stop first at Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center C [map] (tel: 970-529-4465; open year round, May–Sept 7:30am–7pm, Oct and Mar, 8am–5pm, Nov–Apr 8:30am–4:30pm), 15 miles (24km) beyond the park entrance, to buy tickets for hour-long, ranger-led tours of Cliff Palace and Balcony House ruins on Chapin Mesa and Long House on Wetherill Mesa.

Fact

Tour tickets for all three ruins at Mesa Verde can be purchased in person up to two days in advance. They are also available from Morefield Ranger Station (May–Sept 5pm–8:30pm); Colorado Welcome Center in Cortez (May–Sept 8am–6pm, until 5pm rest of the year); and Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum (limited numbers available).

Note that advance planning is essential as this park is remote and very popular. Those hoping to do the Chapin Mesa tours and the 90-minute tour of Long House D [map], the park’s second largest cliff dwelling, in one day (not recommended) should plan their time carefully. It’s a 45-minute drive to less developed Wetherill Mesa from the visitor center, on a winding road with stops at Long House, Two Raven House, Badger House Community E [map] and Kodak House F [map], so named because Gustaf Nordenskiold, the Swedish archeologist who worked with Richard Wetherill, stashed his camera nearby. Visitor facilities at Badger House and Step House were badly burned in the 2000 Pony Fire, which swept across Wetherill Mesa. Recovery will take decades. For those interested in bicycling in the park, bikes are permitted on all public roads except Wetherill Mesa Road. However, 5-mile (8km) Long House Loop, formerly a tram route, has been redesignated as a bicycle route.

Visitors at Balcony House, Mesa Verde.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Another early archeologist (and later park superintendent), Jesse Walter Fewkes, named Far View (elev. 7,700ft/2,350 meters), one of a number of mesa-top pueblo communities that used Mesa Verde between AD 900 and 1300. From here, 100-mile (160km) vistas take in Ship Rock, the Chuska, Lukachukai and Carrizo mountain ranges, and the Monument Valley Upwarp on the Navajo Reservation, south of the San Juan River. Sleeping Ute Mountain marks the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation to the west. To the northwest are the Abajo and La Sal mountains adjoining Arches and Canyonlands national parks in Utah. And to the northeast are the La Plata Mountains, one of several ranges in the San Juan Mountains, near Durango, an alternative base for travelers in this area.

Mesa Verde architecture displays little of the elegant construction that characterizes the great houses and kivas at Chaco Canyon, to the south, which was abandoned long before these cliff dwellings were built. But as Chacoans began to move to the northern San Juan area, it seems logical that some of that culture’s architectural ingenuity would have influenced Mesa Verdean masons. Cliff Palace G [map] is justifiably celebrated for its beauty and harmonious construction, and, as at Chaco, the effort that went into its planning suggests that these were public buildings for use by the whole community.

The minimal number of hearths and burials tells archeologists that Cliff Palace was occupied by a small population. Some were almost certainly priest astronomers who left behind red calendar markings on the smooth plastered interior of one of the tower kivas. These are no mystery to contemporary descendants of pueblos like Santa Ana in New Mexico. Ritual leaders continue to use such markings to monitor the skies and plan annual crop ceremonies around the solstices.

On the other side of the mesa, Balcony House H [map], a rare east-facing structure, has several shallow basins pecked into the floors of its rooms – also thought to be associated with astronomical observation. Like Cliff Palace, Balcony House is divided down the middle by a wall, suggesting a social division of some kind among its 50 estimated residents. A small pueblo, a dizzying 600ft (180 meters) above the canyon, Balcony House has an intimacy that will linger in the memory long after you leave Mesa Verde. The children won’t forget it, either, as they scale ladders and squeeze through tunnels to enter and exit the pueblo.

As many as 5,000 people may have lived at Mesa Verde during the Classic or Pueblo III era (AD 1100–1300). In the Pueblo II era (AD 900–1100), the region was part of a vast trading network bringing items from as far away as Mexico and the Mississippi Valley for redistribution at Chaco Canyon. When Chaco collapsed, the people of Mesa Verde became more insular, perhaps in an effort to protect the attractive resources in their homeland and avoid the same fate as their neighbors to the south.

Exploring Cliff House.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Defensive measures?

Archeologists are unsure why Mesa Verdeans began to build their pueblos in alcoves in the canyon walls in the 1200s. Some think that worsening drought and diminishing firewood and other natural resources forced the people to use creative new ways of survival. Cliff dwellings were well suited to the protected canyons of the Four Corners. They made good use of solar energy, and springlines seeping through the porous sandstone cliffs into the back of the alcoves offered a ready water source. People living there were hidden from view but could still climb to the mesa tops to work fields and travel into the dense pinyon-juniper and oak forests of the canyons to hunt and gather.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the cliff dwellings were used to defend the population against an external danger, perhaps the burgeoning population on the Great Sage Plain or incoming Utes, Navajos, and Apaches vying for Pueblo lands. No mass deaths have been found at Mesa Verde, but there are signs of ritual violence throughout the Four Corners. As a 24-year drought settled in, and powerful ceremonies failed to bring rain, one can imagine the despair that must have gripped the people of the Four Corners as the land that had always supported them failed. By 1300, Mesa Verde was empty. Today, some 24 pueblos, including the Hopi villages in Arizona, and Zuni, Acoma, and the Rio Grande pueblos in New Mexico, trace their ancestors to Mesa Verde.

Exploring the Four Corners

As increasing numbers of people moved to Mesa Verde in the 1100s, space was clearly at a premium. Mesa-top sites at the head of narrow canyons in the northern San Juan region, which offered water, agricultural land and good places to build multistory pueblos, quickly began to fill up. Soon, people were spilling out all across the Four Corners in search of suitable places to live. A number of these sites have been restored and are open to the public. Often undeveloped, they offer a chance to escape the crowds at Mesa Verde and learn more about the people who once lived in the Four Corners.

Where

The spot where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet is preserved as Four Corners Monument Navajo Tribal Park (daily; charge). Navajo and Ute vendors sell foods and crafts at booths near the flapping flags of the survey marker.

A case in point is Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park 3 [map] (tel: 970-565-3751, ext.330 for reservations for half-day or full-day group tours; http://www.utemountaintribalpark.info; open seasonally), which adjoins Mesa Verde on the south. The Weminuche Ute who live on this small reservation are one of seven Ute hunter-gatherer bands that were living in the Four Corners by the 1400s. Forced onto a small reservation in southern Colorado in 1873, Chief Ignacio and 11 other Ute leaders were persuaded to lease Mesa Verde to the government for 10 years to protect it from pothunters. The Utes lost that land permanently in 1906, when President Theodore Roosevelt created Mesa Verde National Park. In 1911, the government took another 14,000 acres (5,700 hectares) from the Utes, including Balcony House. The part of Mesa Verde that remained under Ute control was set aside as a tribal park in the 1960s.

Today, the Ute Nation and the National Park Service work closely together to protect archeological sites, and in summer, for a fee, Ute Moutain Utes offer guided backcountry tours to sites in the tribal park. Easy half-day tours (9am−noon; 1−4pm tours by special arrangement) take in Ancestral Pueblo petroglyphs, scenic lands, Ute pictographic panels, geological land formations, and surface sites. The more demanding full-day tour (9am−4pm) visits four well-preserved canyon cliff dwellings in Lion Canyon, reached by a 3-mile (5km) hike and climbing ladders to the cliffs. To sign up, call or stop at the tribal park visitor center/museum. Check-in time is 8.30am for a 9am departure. Gas up and be prepared to drive your own car across the reservation: 40 miles (64km) for the half-day trip and 80 miles (130km) for the full-day excursion. You should wear a hat, good shoes, and sunscreen, and bring plenty of water and a lunch; these are not available on the tour. Gas, food, and lodging are available at Towaoc and nearby Cortez.

Archeology center

Several other archeological sites near Cortez make good day trips. Don’t miss the attractive Anasazi Heritage Center 4 [map] (27501 Highway 184, Dolores; tel: 970-882-5600; www.blm.gov/co/st/en/fo/ahc.html; daily Mar–Oct 9am–5pm, Nov–Feb until 4pm; charge), 10 miles (16km) north of Cortez, off CO 184. The Anasazi Heritage Center’s museum will be a surprise to those accustomed to the dated exhibits often found at national parks. It was built by the Bureau of Reclamation to house 2 million artifacts that were excavated from the nearby Dolores River Canyon before it was lost forever under McPhee Reservoir. More than a million artifacts from excavations in the Four Corners have been deposited here, making it the single best research center in the area.

Operated by the Bureau of Land Management, the center has an impressive museum that will appeal to children and adults alike. Interactive exhibits offer a variety of ways to understand why archeology is important. Large photographs show step-by-step excavations of nearby sites. Computers allow you to make a virtual tour of an ancient pueblo. Smaller artifacts are located in drawers and can be opened and examined. You can even try your hand at grinding corn using a metate (grinding stone) and mano (hand stone). Pueblo women spent hours doing this each day. It’s not as easy as it looks.

The Anasazi Heritage Center is the headquarters for 164,000-acre (66,000-hectare) Canyons of the Ancients National Monument 5 [map], located to the west on Cajone Mesa. This BLM-managed national landscape monument contains the highest known density of archeological sites in the nation – 6,000 so far, and some areas have more than 100 cultural sites per square mile – spanning 10,000 years of use. It remains largely unknown and undeveloped, so it’s important to stop at the Heritage Center (for more information, click here) and pick up information on visiting. The monument incorporates one previously excavated and restored site: Lowry Pueblo National Historic Landmark, a 40-room pueblo, with eight kivas and a rare great kiva that archeologists believe must have served as a ceremonial center. To reach Lowry, turn west onto County Road CC at the south end of Pleasant View and drive 9 miles (14km) to the site on CR 7.25. Booklets for the self-guided wheelchair accessible trail are available at the trailhead.

CO 10 continues south through the monument. It’s a lonesome place, with views across the Four Corners and south to Monument Valley. You can hike almost anywhere, but this is not a place for the uninitiated. It’s easy to get disoriented. If you want to hike, your best bet is 6-mile (10km) Sand Canyon Trail, a one-way route from the monument south to Road G in McElmo Canyon. Although it’s rugged, this is a popular trail, attracting some 17,000 hikers each year.

Dominguez and Escalante ruins

The Anasazi Heritage Center in Dolores is located next to the Dominguez and Escalante ruins, named for the two friars who became the first Spaniards to travel through the region in 1776, while looking for a route between Santa Fe, New Mexico and Monterey, California. These ruins are small but significant. The four-room Dominguez Ruin, built in AD 1123, contained the burial place of a female of high status who was interred with a variety of grave offerings, including 6,900 turquoise, jet, and shell beads and a unique shell-and-turquoise frog pendant.

The larger Escalante Ruin, at the top of the hill, was built in 1129 by Chaco immigrants and is one of the northernmost of Chaco’s many outliers. It was reoccupied by Mesa Verdeans in 1150, then again in 1200.

Crow Canyon

Research in Sand Canyon has been carried out for a number of years by Crow Canyon Archaeological Center 6 [map] (23390 Road K, Cortez; tel: 800-422-8975; www.crowcanyon.org; daily by reservation), a private institution located near Sand Canyon Pueblo, a few miles west of Cortez. Ongoing excavations here have established that 420-room Sand Canyon Pueblo, at the northern end of the trail, was one of the largest pueblos to be occupied in the final decades of occupation of the Mesa Verde region. It has 100 kivas and 14 towers. Fieldwork at the smaller Castle Rock Pueblo, at the southern end of Sand Canyon Trail, revealed that the occupation there ended with a battle – one of the best documented examples of warfare from the ancient Southwest.

One of the many cultural sites at Canyons of the Ancients National Monument.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

If you’ve ever wanted to know what archeology is like on the ground, this is the place to find out. You can make a reservation to participate in the ongoing dig at Sand Canyon or accompany staff to a variety of archeological sites in the area. Longer residential courses include Cultural Exploration programs with leading Pueblo scholars and hands-on activities, such as weaving and ceramics with American Indian artisans.

Primitive camping on monument roads is permitted at Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, but it has no developed camping facilities. However, there is an excellent little campground at nearby Hovenweep National Monument 7 [map] (tel: 970-562-4282; www.nps.gov/hove; daily), one of those delightful, unexpected parks that remain relatively undiscovered.

Pueblo building, Canyons of the Ancients National Monument.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Six 12th- and 13th-century Mesa Verde–style buildings, built in unusual round, square, and D-shaped towers, line the rim of Little Ruins Canyon at this small national monument, between Blanding, Utah and Cortez, Colorado. Two short rim trails lead from the attractive visitor center and campground to Square Tower Group, Hovenweep Castle, and other structures used by prehistoric farmers.

River of sorrows

Although drought led Ancestral Pueblo people to abandon the Four Corners, the area around Cortez now supports numerous ranches and small farms. They raise bumper crops of beans, an important staple for ancient Pueblo people. Farming on this scale in the Cortez area is relatively recent. It was made possible by irrigation water brought onto the Great Sage Plain by the damming of the Dolores River, the “river of sorrows,” named by early Spanish explorers. Finish your tour by turning right on CO 141, just beyond Dove Creek, and following the pretty Dolores River as it winds north into the redrock country of western Colorado. CO 141 eventually reaches Naturita, the start of the spectacular Unaweep–Tabegauche Scenic Byway, which continues to Whitewater, just south of Grand Junction.

There’s nothing sorrowful about this pleasant scenic byway, which passes through verdant mountains and soaring redrock canyons carved by the Dolores and San Miguel rivers. In the 1800s, these remote canyons were a favored hideout for cattle rustlers from Utah. One of these places, the evocatively named Sewemup Mesa, is one of the most pristine ecological environments in western Colorado, encircled by 1,000ft-high (300-meter) Wingate cliffs. The clifftops are home to peregrine falcons and golden and bald eagles, which fish the Dolores River from high ledges.

Road through Mesa Verde National Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Uravan

Until it closed, Uravan 8 [map] was a major producer of uranium, radium, and vanadium for the nuclear industry, processing 42 million lbs (19 million kg) of uranium and 220 million lbs (100 million kg) of vanadium between 1936 and 1984. A $70 million Superfund cleanup project is stabilizing the tailings above the old Joe Jr Mill. In 1888, the Montrose Placer Mining Company built a 13-mile (21km) hanging flume in the side of Dolores Canyon to bring water from the San Miguel River for gold processing at Mesa Creek Flats. Abandoned three years later, the disintegrating wooden flume can still be seen high above the river rapids.

Fact

Just south of Uravan, The Nature Conservancy’s South Fork of San Miguel River Preserve, below dramatic 14,000ft (4,270-meter) Wilson Peak, protects some of the most important streamside habitat in the Upper Colorado Basin.

CO 141 then turns away from the Dolores River, exiting at Whitewater on the northern end of the verdant Uncompahgre Plateau, a great place for hiking, mountain biking, camping, and four-wheel-drive explorations. At Gateway, the road passes through magnificent Unaweep Valley, with red rocks on the west and high mountains composed of 1.7-billion-year-old rocks on the east. Ranches and farms abound. Watch for the pullout for Unaweep Seep Research Natural Area, an important breeding ground for rare Nokomis fritillary butterflies. For anyone who loves canyons and mountains, this pretty spot will seem like heaven on earth. A New York capitalist, Lawrence Driggs, evidently thought so, too. Between 1914 and 1918, he hired local stone masons to construct a hunting lodge on 320 acres (130 hectares) of land near Gateway, using water from West Creek. The Driggses moved here in 1918 and stayed just a few weeks. The ruined mansion now sits abandoned in a pasture in the huge new Gateway Canyons development. This Southwest-style, greenbuilt planned community, spearheaded by Discovery Channel founder John Hendricks, is providing infrastructure, jobs, and recreation opportunities for outdoor lovers in this historic area just south of Grand Junction.

The Utes

Once nomadic, two remaining bands of Ute Indians live on reservations on Colorado’s Western Slope: The Ute Mountain Ute, near Cortez and the Southern Utes, near Ignacio.

The Utes, from the Spanish word yuta, were named by the first Spaniards to trade with them in Taos, New Mexico, around 1610. They call themselves the Nuche, or The People, and speak the same Uto-Aztecan language as the Aztecs, Hopis, Comanches, Paiutes, and Shoshones. They may have entered northwestern Colorado from the Great Basin – or, as some Utes believe, northern Mexico – between 500 and 800 years ago. Like their Archaic forebears, they were consummate hunter-gatherers. They began farming informally after entering the canyon country of western Colorado, possibly after mingling with Fremont Indians in the area.

By historic times, there were six Ute bands in Colorado. The Mouache band’s territory included the eastern Rockies, the San Luis Valley, and northern New Mexico, where they mingled with the Kapote band. The Weminuche lived in the canyon country of the Four Corners. These three bands are known as the Southern Utes. The Kapote and Mouache bands now occupy the Southern Ute Reservation, east of Durango. The Weminuche live on the more traditional Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, south of Cortez.

The largest Ute bands occupied northwestern Colorado and were known as the Northern Utes. Chief Ouray’s band – the Tabegauche or Uncompahgre Utes – lived in the Gunnison and Uncompahgre valleys, where they hunted atop 10,000ft-high (3,050-meter) Grand Mesa and wintered near Montrose and Delta. North of the Tabegauche were the Parianuc or Grand Valley Utes, who lived along the Colorado River, and the Yampa band, who lived in the Yampa River Valley.

These two bands were renamed the White River Utes after Nathan Meeker established an Indian agency in Meeker. Tragedy struck when, in an effort to get Utes near Craig to take up farming, Meeker plowed up their horse racetrack, triggering a fist fight; Army involvement; the massacre of soldiers, Meeker, and eight of his men; and the taking of white women as hostages. This crisis led to the White River Utes and Chief Ouray’s band being forced to move to the bleak Uintah Basin of east-central Utah in 1880 – a landscape with so few resources it was said even the birds wouldn’t fly over it.

The Mouache and Kapote bands, led by chiefs Severo and Buckskin Charley, were forced to become farmers after accepting land allotments on the Southern Ute Reservation in 1863 – an activity scorned as women’s work by the skilled hunters. Chief Ignacio and the Weminuche band held fast to a traditional way of life for decades, living in tents on the undeveloped Ute Mountain Ute Reservation until well into the 1930s.

Today, Utes have bowed to the inevitable and taken up Anglo pursuits, such as farming, ranching, construction, tourism, gaming, and motel-keeping. Even so, traditional Ute gatherings still take place. Chipeta Day, for example, is held every September at the Ute Indian Museum, south of Montrose, on Ouray’s old farm, where his second wife Chipeta and her stepbrother John McCook are buried. It includes dancing, food, traditional beaded handicrafts, movies, silent auctions, and other activities. All three reservations still perform the Bear Dance every spring, a multiday event that celebrates the end of winter, a transition signified by a bear waking up from hibernation.

Chief Severo and family, c.1885.

Library of Congress

Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde.

Getty Images