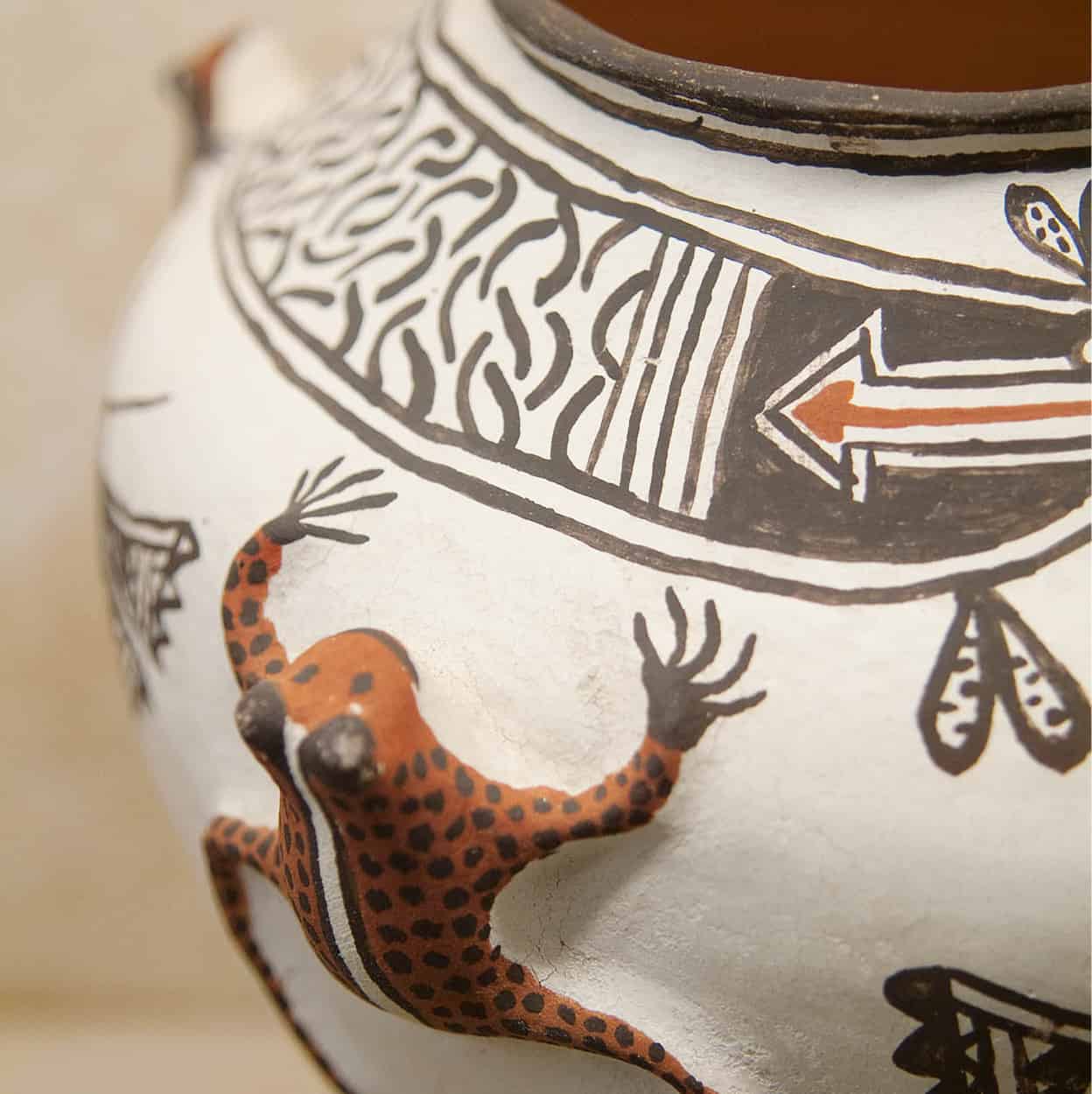

Colorado’s least developed region, its northwestern corner, has begun to be discovered. This is due, in part, to cyclical oil, gas, uranium, and coal mining booms that have periodically swelled the population and led to the construction of good highways and rail links. But mostly it’s because of the presence of Dinosaur National Monument and the growth of recreation in the gorgeous Colorado red rock canyons surrounding Grand Junction (pop. 59,778), the main shopping center for the region and a logical base for explorations.

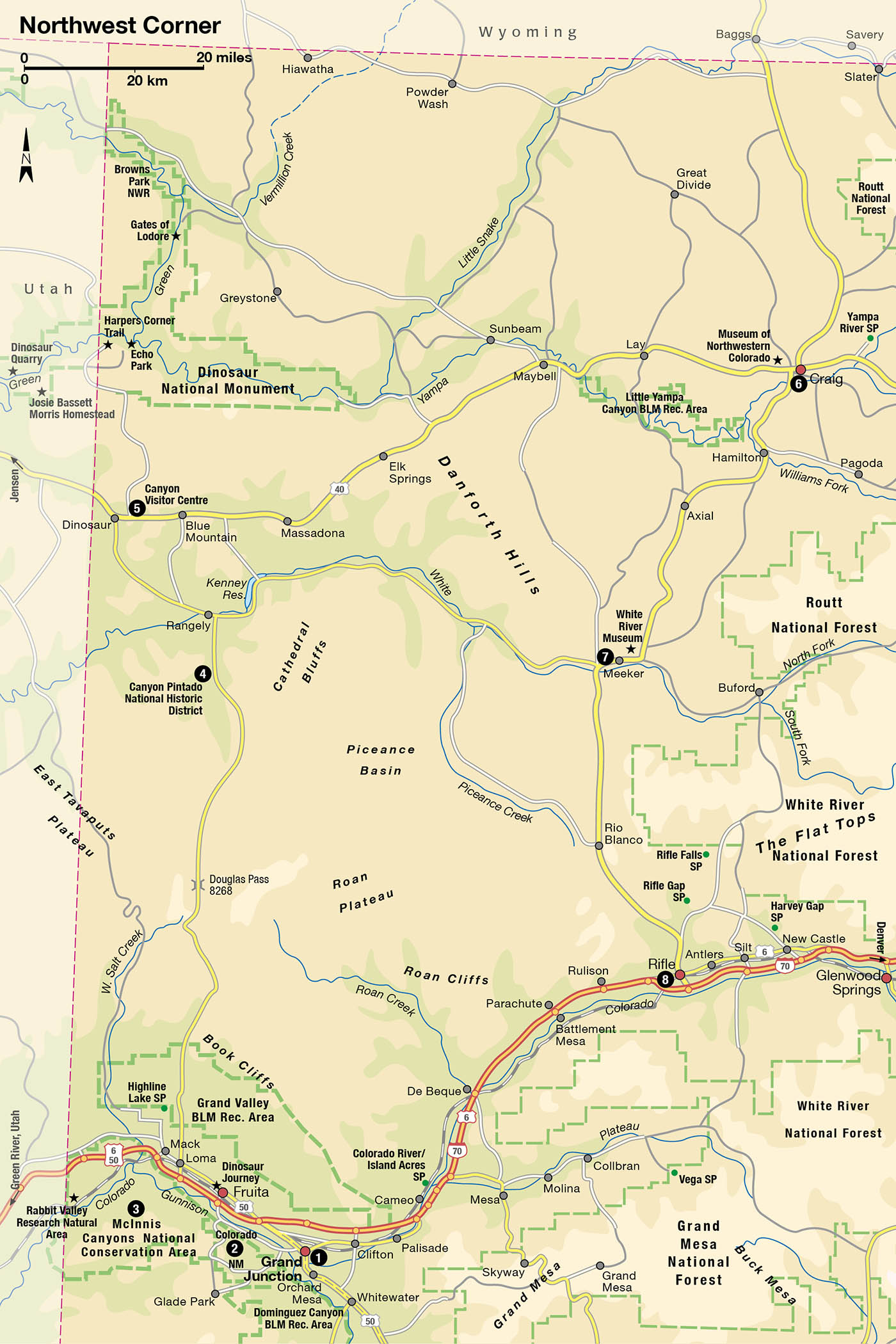

Junction, as locals call it, is located just north of the confluence of the Colorado and Gunnison rivers, in the majestic Grand Valley. With its valley setting, the forest-clad Rockies to the east, and the mile-high Colorado Plateau to the west, Junction has one of the loveliest settings of any city in the Southwest. To the north is Interstate 70 closely paralleling the imposing facade of the Book Cliffs. To the south is the Uncompahgre Plateau, the only place apart from the Continental Divide where two rivers – in this case the Uncompahgre and Dolores – divide and flow east and west, respectively.

Colorado National Monument.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

On its northern end, the orange sandstone of the Uncompahgre Uplift has been carved by wind, water, and ice into vertical cliffs, monuments, and headlands that offer endless possibilities for recreation in Colorado National Monument and adjoining McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area.

Fishing in Grand Mesa National Forest.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Recreation is also plentiful on the 500-sq-mile (1,300-sq-km) forested volcanic plateau known as Grand Mesa, 35 miles (56km) east of Grand Junction. An outdoor-lover’s paradise, 10,000ft-high (3,000-meter) Grand Mesa is the largest flat-topped mountain in the world. Its cool forests, 200 sparkling lakes and numerous backcountry trails beckon to hikers, campers, and fishermen all summer, when temperatures in the valley reach 100°F (38°C). In winter, “The Mesa,” as it’s called, becomes a haven for cross-country and downhill skiing, snowmobiling, and other snow sports at Powderhorn Mountain Resort, and is a popular place for weekend getaways at rustic lodges with views all the way to the farmlands of the Uncompahgre and Grand Valley.

Located on the banks of the Colorado River, Grand Junction itself grew up around the railroad in 1881. It has been known as a commercial center ever since. Early settlers capitalized on the ready irrigation water and planted peach and apple orchards and vineyards, which today still thrive in the pretty suburbs of Clifton, Palisade, and Fruita. Grand Junction’s loveliest bed-and-breakfasts are located in these leafy communities, where you can spend lazy days strolling and bicycling, wine tasting, fruit picking, and admiring the spectacular cliffs surrounding the valley.

Sadly, Grand Junction 1 [map] itself, squeezed between I-70 on the north and the Colorado River on the south, seems to be losing the fight with urban sprawl. New housing developments and miles of “big box” superstores, chain hotels, and restaurants on the wide avenues leading from I-70 have given the city a nondescript Anytown-USA appearance. That’s a pity because there’s lots to see and do in this historic city, once you get your bearings.

Book Cliffs, near Grand Junction.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Grand Junction

Start in the restored historic downtown, near the railroad station. In 1963, Junction received nationwide acclaim for its Downtown Shopping Park, an attractive, five-block Main Street redevelopment that features restored historic brick buildings housing shops, galleries, and the city’s best restaurants, breweries, and cafés. One of the highlights of the downtown is its innovative Art on the Corner project, which was launched in 1984 and features lifesize sculptures on annual loan to the city from local artists. A stroll along the tree-lined, curving streets makes for a fun art walk on a warm summer evening.

When Exxon dropped a multimillion-dollar oil-shale extraction project in nearby Parachute in 1984, Grand Junction fell on hard times, with nearly 15 percent of its homes vacant by 1989. But the city has worked hard to improve amenities, which has had a positive effect on its cultural institutions. The restored 1923 Avalon Theatre (645 Main Street; tel: 970-263-5700; www.avalontheatregj.com) is the linchpin of the Downtown Shopping Park, hosting plays, concerts, and other entertainment throughout the year. Mesa State College, founded in 1925 and located halfway between I-70 and downtown, is a four-year liberal arts college. It is home to the stylish Western Colorado Center for the Arts, otherwise known as the ART Center (1803 N. 7th Street; tel: 970-243-7337; www.gjartcenter.org; Tue–Sat 9am–4pm; charge, Tue free), where you’ll find historic and contemporary works by Western artists and special exhibitions all year.

Junction’s main cultural institution, the Museum of Western Colorado, is the largest museum between Denver and Salt Lake City. It has three branches. Downtown’s Museum of the West (462 Ute Avenue; tel: 970-242-0971; www.museumofwesternco.com; May–Sept Mon–Sat 9am–5pm, Sun noon–4pm, Oct–Apr Mon–Sat 10am–4pm, closed Sun) is an accessible, modern museum featuring a one-room schoolhouse, a uranium mine, Indian pottery, guns, and many other exhibits (look for the one on Alferd Packer, the infamous “Colorado Cannibal”).

Colorado National Monument.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

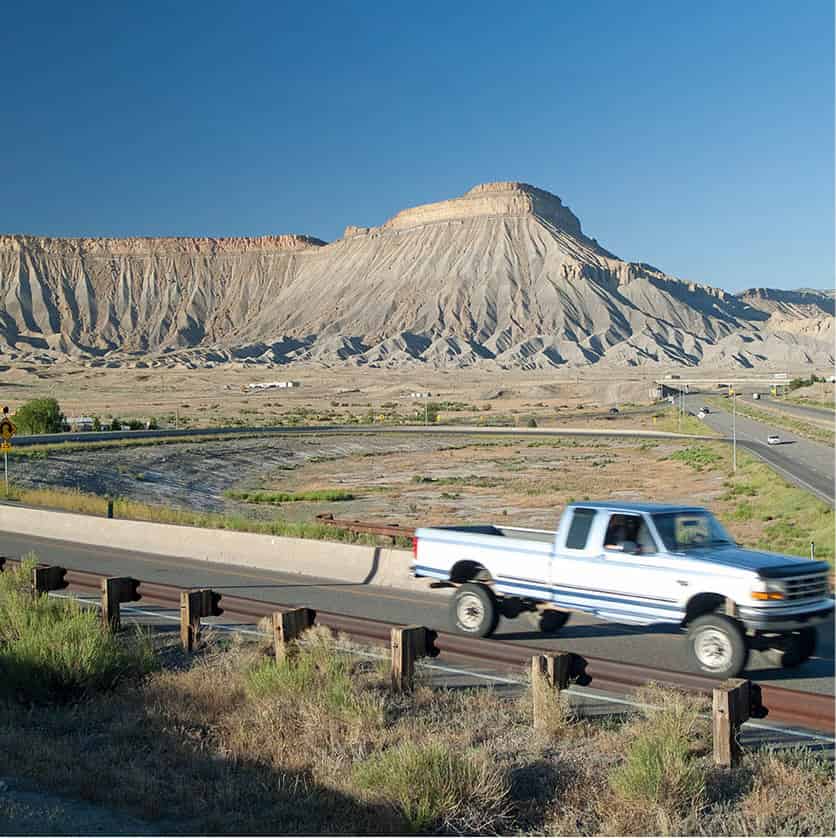

McKee Springs petroglyph, Dinosaur National Monument.

iStock

East of town, in Clifton, is the Cross Orchards Historic Site (3073 F. Road; tel: 970-434-9814; Apr–Oct most Thu–Sat 9am–4pm). This branch of the museum is living history at its best, recreating traditional farm life in one of Colorado’s largest apple orchards. Exhibits include a blacksmith shop, a bunkhouse, a barn and packing house, and the historic orchards, where you can buy fruit in fall. Living history demonstrations take place daily between April and October, and there are numerous special events, including arts and crafts workshops and displays of traditional farming methods.

The most popular branch of the museum for children is Dinosaur Journey (550 Jurassic Ct, Fruita; tel: 970-858-7282; May–Sept daily 9am–5pm, Oct–Apr Mon–Sat 10am–4pm, Sun noon–4pm), west of town, in Fruita. Dinosaur Journey has a strong novelty feel, with its TV-generation exhibits and half-size robotic Dilophosaurus, Utahraptor, Apatosaurus, and other dinosaurs. But it is also perfectly located to teach kids about real-life paleontology. Just up the street, at the east and west entrances to Colorado National Monument, are Riggs Hill and Dinosaur Hill, where paleontologists from the museum conduct ongoing fossil digs. Rabbit Valley Research Natural Area, 24 miles (39km) west of Grand Junction, is another area rich in dinosaur bones.

Kids

If you have kids who love dinosaurs, they may enjoy a 1- to 3-day Dinosaur Dig excursion to the Mygatt-Moore Quarry with Dinosaur Journey to dig for bones with a paleontologist. For information and reservations, tel: 888-488-DINO, ext. 212 on weekdays.

Colorado National Monument 2 [map] (tel: 970-858-3617; www.nps.gov/colm; daily June–Sept 8am–6pm, Mar–May, Oct–Nov 9am–5pm, Dec–Feb 9am–4pm) is the top scenic drive in Grand Junction. From the west entrance at Fruita, 23-mile (37km) long Rimrock Drive winds onto 2,000ft (6,000-meter) high red rock cliffs on the south side of Grand Valley and is one of the most popular scenic mountain bike rides in an area famous for its biking. More than a dozen scenic vistas offer views of the Colorado River, Grand Junction, the Book Cliffs, Grand Mesa, and the eroded headlands, monument rocks and odd-shaped hoodoos of the monument. This landscape “felt like the heart of the world” to pioneer John Otto, who lived alone in the wild canyons. Otto built miles of trails through the area and helped get it set aside as a monument in 1911. He served as the park’s first caretaker until 1927.

Campers can either spend the night in the park’s pleasant 80-site campground near Saddlehorn Visitor Center (be warned: it gets busy), or turn south at East Glade Park Road and drive to a BLM campground within the 123,400-acre (49,938-hectare) McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area 3 [map] (2815 H. Road, Grand Junction; tel: 970-244-3000; www.blm.gov/co/st/en/nca/mcnca.html). Designated in 2000, McInnis Canyons (formerly known as Colorado Canyons) is an extraordinary resource for Junction visitors and residents alike. You can hike a variety of trails in 75,500-acre (30,554-hectare) Black Ridge Canyons Wilderness (the sandstone arches of Rattlesnake Canyon are particularly memorable); mountain bike to Moab, Utah, on 137-mile (221km) Kokopelli’s Mountain Bike Trail; and raft the canyons of the Colorado River from Loma Boat Launch through lovely Ruby and Horsethief Canyons to Westwater Canyon, Utah.

Browns Park

Browns Park is 80 miles (130km) northwest of Craig, via a rough road that crosses a swing bridge over the Green River into Browns Park National Wildlife Refuge. The valley was a rendezvous point in the 1820s and 1830s, where mountain men traded with Comanche, Ute, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Navajo hunters. Homesteaders arrived in 1873, and by the 1880s, the valley’s isolation attracted outlaws like Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch (for more information, click here), who used it as a remote hideout. The 44-mile (71km) section of the river between Little Hole Boat Launch and Little Swallows Canyon has Class I flatwater, several hiking trails, and free campgrounds. Private whitewater river trips through Dinosaur National Monument are by lottery permit only. Annual deadline for applications is February 1.

Take your time making the three-hour drive along the winding scenic highway from Fruita through the Book Cliffs and Piceance Basin to reach Dinosaur National Monument, one of the best-kept secrets in the National Park System. On your way, look out for wild horses running in the Piceance Basin, part of several herds in the area managed by the Bureau of Land Management. Also of interest is the Canyon Pintado National Historic District 4 [map], which preserves the entrancing rock art left behind by Fremont Indians who lived in this river valley more than a thousand years ago. At Rangely, SR 139 joins SR 64 and enters an austere desert landscape of pale crumbly shales weather-blasted by erosion. Oil and gas are the mainstays of this hot, dusty town of see-sawing oil derricks, oversized trucks and cowboy hats, where the only water in sight is the Kenney Reservoir on the White River, just north of town.

Geo-scientists measure cracks and stability in the rock containing the dinosaur bone beds, Dinosaur National Monument.

iStock

Blink and you may miss tiny Dinosaur, 18 miles (29km) north of Rangely, gateway to the Colorado side of Dinosaur National Monument. Your first stop should be the Colorado Welcome Center at Dinosaur (101 E. Stegosaurus Avenue; tel: 970-374-2205), at the junction of SR 64 and US 40, where staff will help you use your time wisely and pass on priceless insider tips on good places to take photos, view wildlife, hike little-known trails, and even hang-glide – a popular sport on the cliffs above the serpentine canyons of Dinosaur. Canyon Visitor Center 5 [map] (4545 E. US 40, Dinosaur; tel: 970-374-3000; www.nps.gov/dino; May–Oct daily9am–5pm, Apr–May Sat-Sun 9am–5pm, closed in winter) is 2 miles (3km) east of the junction, on US 40, at the entrance to the Canyons section of the monument and has information and an audiovisual program on the park. Note: there are no dinosaur bones on the Colorado side of the park; they are all in the Utah section (see below).

Remote and inaccessible, the Yampa River, which flows west to join the Green River in Echo Park in what is now Dinosaur National Monument, was a mystery to most early Americans. Fremont Indians and Utes had wandered there for centuries. The Spanish Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776 had passed to the south, through the fertile Colorado River valley, site of present-day Grand Junction, searching for a cross-country route to California from New Mexico. Fur trapper William Ashley was the first American to run the Green River in 1825, when rapids nearly destroyed his hide-covered bullboats.

Where

Northwestern Colorado and northeastern Utah are part of the huge Dinosaur Diamond Scenic Byway, which includes Riggs Hill, Dinosaur Hill, and Rabbit Valley Research Natural Area in Fruita, and, of course, Dinosaur National Monument.

But it wasn’t until 1869 and 1871, when Major John Wesley Powell ran the length of the Green and Colorado rivers in the first government survey of the region, that Americans glimpsed the treasures at the heart of Colorado’s wild canyonlands. The expedition passed through a lovely red-walled canyon on the Green River that Powell named the Gates of Lodore. Later, the men camped at a huge river bend, where the Yampa joined the Green River and snaked around an 800ft (240-meter) high sandstone wall shaped like a ship’s prow. The distinctive formation (later dubbed Steamboat Rock) magnified the sound of the men’s voices. Powell called it Echo Canyon.

Yampa River Canyon

In 1928, A.G. Birch, a reporter for the Denver Post, decided to take a trip down the Yampa River. For three weeks, headlines such as “Expedition to Risk Death in Wild Region” and “Post’s Expedition is Nearing Perilous Trip Down Canyon” captivated readers following Birch’s adventures in the rugged, almost unknown Colorado canyon country bordering Utah and Wyoming.

“There is nothing like the Yampa River Canyon that I have ever seen,” he told his readers. “Imagine seven or eight Zion canyons strung together, end to end; with Yosemite Valley dropped down in the middle of them; with half a dozen ‘pockets’ as weird and inspiring as Crater Lake; and a score of Devil’s Towers plumbed down here and there for good measure – then you will just begin to get some conception of Yampa Canyon.”

Birch’s message was clear. The canyons of northwestern Colorado merited national park status. The National Park Service took note, sending out surveyors who concurred with Birch that the area was worthy of inclusion in the park system. How to accomplish this during the lean years of the Depression was another matter. Finally, in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt quietly added 200,000 acres (81,000 hectares) of Colorado canyon country to the nearby Dinosaur National Monument.

Eighty-acre (32-hectare) Dinosaur National Monument had been set aside in 1915 to prevent the wholesale removal of an important quarry of dinosaur bones that had been found embedded in the fossil-rich Morrison Formation in 1909. But although the desert rocks surrounding the Colorado River in northeastern Utah held numerous dinosaur fossils, there were none deep in the billion-year-old canyons in northwestern Colorado, where the main features were extraordinary scenery, historic ranches, and abundant wildlife.

Wall of Bones

If you have kids, you’ll want to visit the Dinosaur Quarry on the Utah side of the monument first, then perhaps return to the Colorado side to spend time at the Canyons. The Dinosaur Quarry is a 45-minute drive from Dinosaur, 7 miles/11km north of Jensen, Utah, so plan accordingly.

The Dinosaur Quarry’s central exhibit is its Wall of Bones, which contains 1,500 bones of 10 different dinosaur species, including Camarasaurus, Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, and Dryosaurus, first discovered here in 1909 by Carnegie Museum paleontologist Earl Douglass. Since then, excavations have uncovered more than 2,000 bones of dinosaurs embedded in the Morrison Formation. This is probably just a fraction of the number of dinosaurs that were entombed here when a catastrophic river flood wiped them out 150 million years ago. The clay rocks of the Morrison Formation may have yielded dinosaur treasures but they have unfortunately proven very unstable for structures, and in 2006, the Dinosaury Quarry was forced to close for safety reasons. In 2009, the Park Service received $13.1 million in stimulus funds to create the attractive new Quarry Visitor Center (tel: 435- 781-7700; daily May–Sept 8am–6pm, Sept–Dec 9am–5pm). The former visitor center now houses the Quarry Exhibit Hall (May–Sept 8am–5:30pm; limited access by vehicle caravan from the visitor center rest of the year), which is supported by 70-ft steel micropile columns that extend into the clay formation and keep the Wall of Bones stable. During visitor center hours in summer, regular shuttle bus takes visitors from the visitor center to the exhibit hall, ¼ -mile (0.4km) away.

This part of the monument sits on the Green River, below Split Mountain, a huge tilting, geological anticline with a plated profile that looks oddly like a stegosaurus (it’s easy to get dinosaurs on the brain here). Geology is a big part of the story of Dinosaur. The park displays 23 different geological formations, the most complete geological record of any national park. That tops even the Grand Canyon.

The 22-mile (35km) Tilted Rocks Scenic Drive offers a closer look at Split Mountain and the Green River, both of which have campgrounds for hikers and river runners. Signs of human occupation can be seen all along this easily accessible road. A prehistoric rock shelter that was used by Paleo-Indians as long ago as 7,000 BC can be viewed at the start of the scenic drive; it has many examples of Fremont Indian art. At the end of the road, in Cub Creek, you’ll find the fascinating Josie Bassett Morris Homestead. Morris was a pioneer who spent her early years in Browns Park, just north of Dinosaur park, and knew Butch Cassidy. She moved to Cub Creek a year before Dinosaur became a national monument and was well known locally. When she died in 1964, her homestead became part of the expanded park.

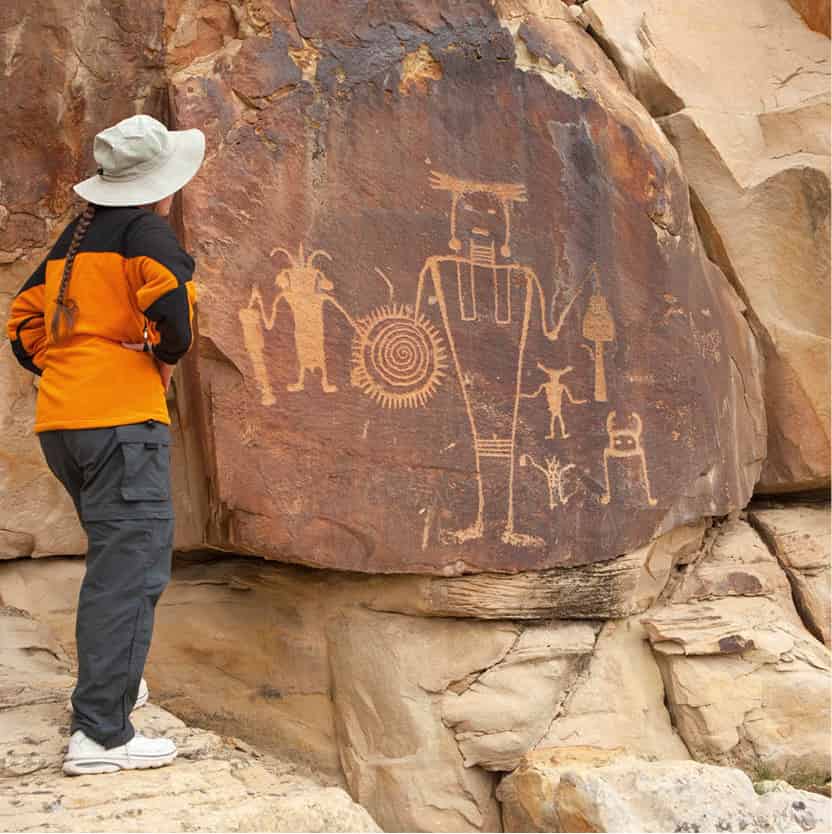

Pottery at the Museum of Western Colorado.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Canyon country

Morris wasn’t the only homesteader drawn to Dinosaur’s spectacular river canyon setting. In the early 1900s, Ralph Chew, originally from Blackburn in Lancashire, England, built a ranch on a tributary of the Green River, close to Echo Park, in the Canyons section of the park. The Chew family continues to ranch in Dinosaur, but the historic ranch, including a well-preserved chuck wagon, log cabins, and corrals, is now part of the park and can be seen along the rugged, 13-mile (21km) drive down to Echo Canyon. The Chew Ranch is one of the highlights of the 23-mile (37km) Harpers Corner Scenic Drive to Harper’s Corner in the eastern section of the park. It’s easy to see what drew the Chews, the Mantles, the Ruples, and other early ranchers: a sense of space, abundant grass, reliable water, and plenty of game, from elk to deer to jackrabbits.

Hopi Kachina dolls at the Museum of Western Colorado. The dolls are not toys for children, but are effigies that embody the masked spirits of the Hopi tribe.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

If you’re here in summer and you have a four-wheel-drive, high-clearance vehicle, plan on spending at least one night in the popular campground at Echo Park, where history and landscape are at their most beguiling. This is one of the most beautiful canyon settings in the Southwest and a perfect place to tune into the ancient rhythms of rock, sky, and river. Gentle breezes on the river brush across your face at night as you sleep, and rangers offer nightly skywatching and campfire talks, and morning hikes through the cottonwoods along the river. Next day, drive the Yampa Bench Road, east of Echo Park, which has a number of sights, including historic cabins, river views and the Mantle Ranch, still a private holding here. Before leaving, continue to the end of the Harpers Corner Scenic Drive and hike the 2-mile (3km) Harpers Corner Trail for views of Whirlpool Canyon and the massive Mittens Fault in the Weber Sandstone.

The fight for Echo Park

Throughout the 1940s, out-of-the-way Dinosaur National Monument remained a well-kept secret, but in the early 1950s the park found itself at the center of a major controversy over government plans to construct huge dams at Echo Park and Split Mountain. The Sierra Club and more than 70 other environmental organizations formed an unprecedented alliance and successfully defeated the irrigation project. Many people still recall that their introduction to Dinosaur came through a flurry of outraged magazine and newspaper articles aimed at saving the park’s canyons from immersion under a huge reservoir.

Backed by respected Western writers Bernard de Voto and Wallace Stegner, landscape photographer Philip Hyde and newly named “environmentalists” like the Sierra Club’s David Brower, Dinosaur became the poster child for a growing anti-development struggle in America. Nationwide support for saving wild lands in Dinosaur paved the way for the landmark 1964 Wilderness Act. Outdoor lovers came out to run the rivers they had saved and to camp at Echo Park, but the victory at Dinosaur was overshadowed in 1962 by the flooding of Glen Canyon, north of Grand Canyon, “The Place No One Knew,” a defeat that cast a long shadow over the environmental movement. Dinosaur returned to obscurity. For another generation, it was just a park of old bones.

Wild West

Finish your tour by returning to Grand Junction through the eastern portion of the Piceance Basin. You can take the fast route on US 40 to Craig 6 [map], a major coal-mining town. The main attraction in town is the interesting Museum of Northwestern Colorado (590 Yampa Avenue; tel: 970-824-6360; www.museumnwco.org; Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat 10am–4pm; free), which displays one of the West’s largest collections of cowboy and gunfighter memorabilia.

A more scenic drive crosses the heart of the basin on SR 64, following the route of the pretty little White River, through Rangely to Meeker 7 [map]. Meeker (pop. 2,493) is a small, quiet, historic town surrounded by national forest, making it a popular outdoor-lover’s getaway. It was named for a naive but well-intentioned missionary named Nathan Meeker, who came to the White River Ute Indian Agency in the 1870s. Meeker’s plan to teach the Utes how to farm was met with stiff resistance from the tribe, whose beliefs taught them to live in harmony with what nature provided and forbade tilling the soil as a desecration of Mother Earth. The cultural clash ended tragically when Meeker plowed up the tribal racetrack, an important social area for this horse-loving people, and he and eight others were murdered, along with several soldiers. Unfortunately, their actions played right into the hands of government officials who, despite the intervention of Chief Ouray, used the massacre to justify removing the Utes from Colorado, thereby opening the way to white settlement.

You can learn more about this sad story at the White River Museum (565 Park Street; tel: 970-878-9982; www.meekercolorado.com/museum.htm; daily Apr–Nov 9am–5pm, Dec–Mar 10am–4pm; free) in Meeker, housed in an old log-cabin army barracks in the center of town. On the opposite side of the plaza is the Victorian-era Meeker Hotel & Café (560 Main Street; tel: 970-878-5255), built in 1896 and still going strong today. This hunting lodge−style hotel’s illustrious guest list includes Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt, Gary Cooper, Billy the Kid and, more recently, former vice president Dick Cheney, who, like many outdoorsmen, enjoyed hunting and fishing in White River National Forest.

SR 13 heads south for 39 miles (63km) to the small town of Rifle 8 [map], where you can pick up I-70 and return to Grand Junction or turn south to pick up the Grand Mesa Scenic Byway. A short detour to Rifle Falls State Park (5775 SR 325; tel: 970-625-1607, 5am–10pm) offers one of the most delightful surprises on this tour. Exiting from nearby mountains, East Rifle Creek has created a lush year-round riparian oasis in a dry land, where water from the creek spills over a limestone cliff in the park, creating three waterfalls. In 1910, the waterfalls were used to power Rifle Hydroelectric Plant, the first in Colorado. A brief stroll takes you to the base of the falls, then a short, steep climb leads to the top. Rifle has a year-round campground that makes the perfect place to cool down before heading back to the sizzling Grand Valley.

Rifle Falls State Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications