The early 1970s, an era when Colorado’s population was exploding, saw the birth of a bumper sticker fad so unusual that it was written up in Time and Life magazines. Created by Denverite Sandy Glade, the stickers bore the same distinctive green-and-white mountain silhouette as the state’s license plates. The first ones were emblazoned with the single word “NATIVE,” which spoke volumes. Everyone knew what they meant: “I’m not one of those newcomers who come here to jack up prices, pollute our pure Rocky Mountain springwater, take all the parking spaces, and generally “Californicate” our state – so don’t blame me.” Within weeks, new bumper stickers started popping up: “SEMI-NATIVE,” “LOCAL,” “SURVIVOR,” and, yes, “TOURIST.”

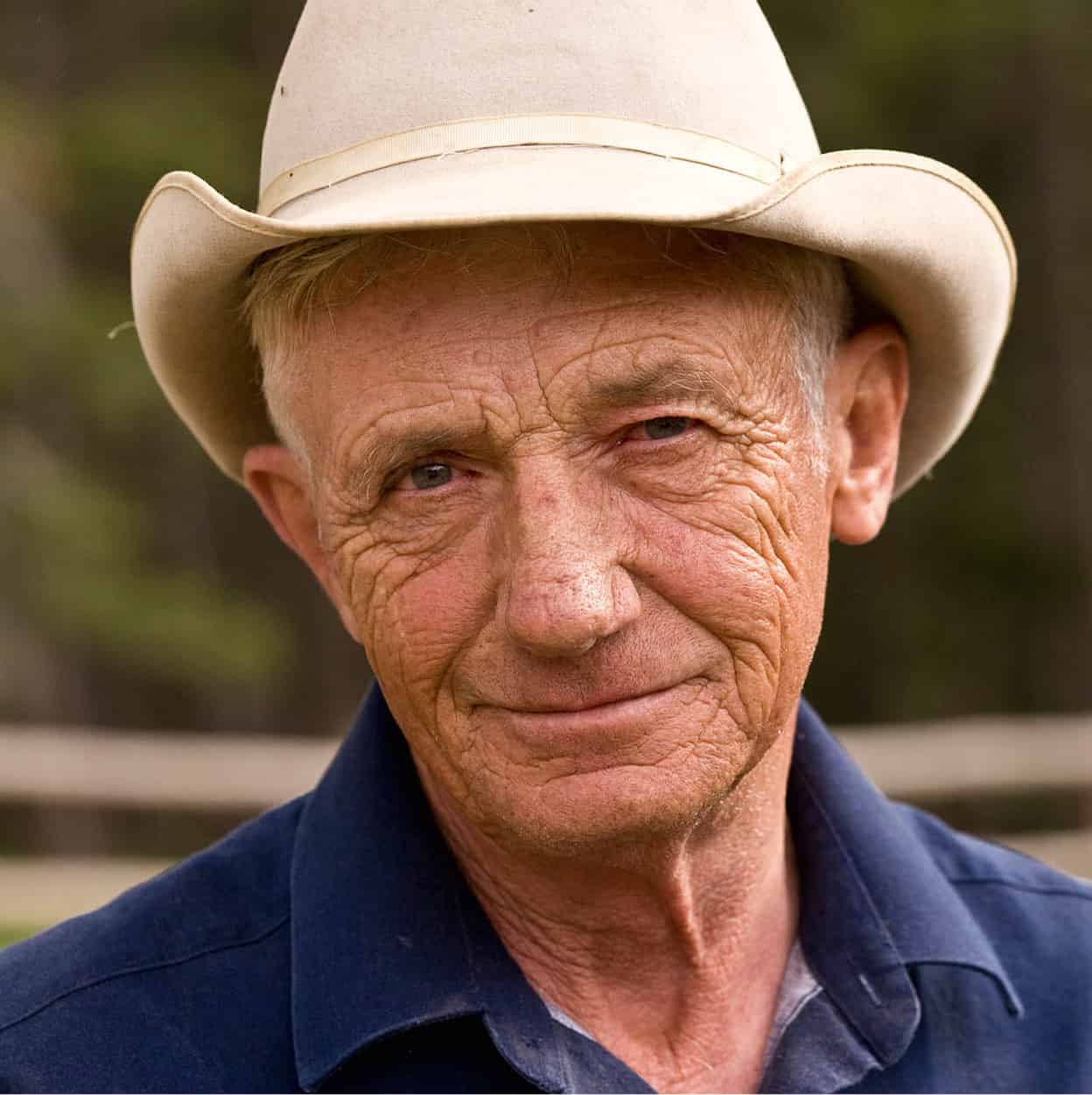

Farmer, Central Rockies.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Since then, the native-versus-newcomer issue has become almost moot, as the state’s population has more than doubled, largely due to the migration of an estimated one million Californians.

Colorado folks are such a diverse lot that it’s hard to generalize about the characteristics that make them Coloradans. Or are they Coloradoans? They can’t even agree which term is correct – just ask the news editors at the Adams State College Coloradan and the Fort Collins Coloradoan. (Merriam-Webster has it both ways.)

Denver’s prominent 19th-century black residents included Barney Ford, a businessman who won the vote for black males in the West, and Aunt Clara Brown, a freed Kentucky slave and laundress who took in needy African Americans.

Coloradans are urban and rural, liberal and ultraconservative, wealthy and poor. Perhaps the best way to define how Coloradans traditionally see themselves is to look at them in the context of the state’s cultural landscape – that is, how they relate to the land and face the challenges of getting along with their neighbors.

Rags to riches to rags

Much about Colorado’s collective self-image is reflected in its legends. Unlike other Western states, you don’t find many cowboys, lawmen, gunslingers, or pioneers in Colorado’s version of its own history. Although cattle ranching has been a vital part of the state’s economy since the 1860s, few residents can name a single rancher, past or present. Colorado heritage is defined by tales of gold and silver prospectors, whose good and ill fortunes are a potent metaphor for many other enterprises, including tourism, land development, and the ski industry.

Cheyenne woman in ceremonial clothing.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Some are ironic stories of losers like Bob Womack, the man who first discovered gold in the Cripple Creek District in 1891. Unable to convince others that his find was anything more than a drunken fantasy, he sold his mining claim for $300. The claim became the El Paso Mine, which produced more than $10 million worth of ore. Womack died broke.

At the other end of the spectrum was Womack’s old drinking buddy Winfield Scott Stratton, a Colorado Springs carpenter who spent his summers prospecting around Cripple Creek. He returned to a claim he had twice previously explored and abandoned, after finding nothing. The third time proved to be a charm. He struck a rich gold vein that became the Independence Mine. He sold his claim for $10 million and spent the remainder of his life as a philanthropist, gifting Colorado Springs with magnificent public buildings, parks, and the finest streetcar system in the state. Upon his death, 11 years after his first gold strike, his will endowed the Myron Stratton Home in Colorado Springs. Named after his father, it was an orphanage and old folks’ home, but one unrivaled in the world for its lavish comforts. The establishment, set on a large, walled estate with lawns and bowers, tennis courts, and a swimming pool, still operates today.

Some Colorado legends are just plain bizarre. Consider the case of Alferd Packer, the Lake City guide who spent a winter snowed in with six greenhorn gold prospectors high in the San Juan mountains – and survived by eating them. He was convicted twice, not of cannibalizing his companions (which wasn’t a crime) but of killing them first. He spent the rest of his life in the old Cañon City Penitentiary, where his separate cabin is now a tourist attraction. To this day, Colorado historians write papers purporting to prove his innocence. Coloradans just love Packer. At the University of Colorado, the student council voted to name a campus cafeteria after him. Trey Parker, co-creator of the raunchy television series South Park, wrote a stage play about Packer that was a hit in Boulder and later became a cult movie. He called it Cannibal: The Musical.

Young Denverite.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

For love or money

The legend that best symbolizes Colorado is that of Horace Tabor and his two wives. Horace, a Leadville grocer, postmaster, and mayor, grubstaked two German prospectors $17 worth of food in exchange for a one-third interest in whatever they found. They struck silver and, five months later, declared a $10,000 dividend for each partner. Horace used his share to invest in other mines around the district, including the played-out Matchless Mine. As the story goes, the seller had “salted” it with a shotgun shell loaded with gold dust, a common fraud at the time. Digging down a few feet revealed one of the richest silver veins in Colorado history, making Horace a millionaire several times over.

Money spelled trouble for Tabor. His wife, Augusta, an austere New Englander uncomfortable with sudden wealth, continued to live frugally and rent rooms in their modest home. Horace liked the seemingly endless supply of money just fine and, at age 50, may have been experiencing a midlife crisis. He promptly fell in love with Elizabeth “Baby Doe” McCourt, a divorcee half his age. Horace and Baby Doe soon moved to Central City, where he lavished her with gifts and flowers to the tune of $1,000 a day. He persuaded a Durango judge to grant him a quick, secret – and illegal – divorce and later married Baby Doe.

Horace Tabor’s bigamy became a problem when he was appointed to the seat of a deceased US Senator from Colorado. What had been viewed in Central City as everyday recklessness – perfectly understandable to anyone who saw the homely Augusta and the beautiful Baby Doe – in Washington DC society was a scandal of monumental proportions. To gain respectability, Horace gave Augusta the lion’s share of his estimated $9 million fortune in exchange for a legitimate divorce.

Ten years passed. Horace built opera houses. Baby Doe lived lavishly. Then came the silver crash of 1893, and virtually overnight they found themselves penniless. The bank foreclosed on the Matchless Mine, cutting off their only source of income. At age 66, Horace took a job shoveling slag at a Cripple Creek mine for $3 a day. To the surprise of everybody who had regarded her as a notorious gold digger, Baby Doe stood by her man. In 1898, Horace was appointed postmaster in Denver, then died the following year.

Baby Doe Tabor spent the last half of her life in Leadville, living in a converted storage shed beside the Matchless Mine and unsuccessfully looking for a way to regain ownership. She died there at age 80, destitute. Four gunny sacks she had left at the local hospital for safekeeping were found to be filled with silks, jewelry, and other treasures from her glory days. As for Augusta, she lived out her remaining years as a wealthy dowager in Pasadena, California.

The moral of the Tabors’ story depends on who’s telling it. What goes round comes round? Spend it while you’ve got it? Never give up? Take the money and run? Whatever meaning one reads into it, the tale seems strangely relevant whenever you visit one of Colorado’s gold rush–era towns, whether it’s now a prosperous city, a posh ski resort, or a ghostly cluster of decrepit log cabins and crumbled stone chimneys still waiting for good times that may never come again.

Have palette, will travel

Throughout the 1800s, as Americans set their sights on expansion west, artists were there, too, recording landscapes that defied the imagination. One of the first was George Catlin, who journeyed west in the 1830s and produced 500 oil paintings that captured the nobility of American Indian cultures. Catlin’s work influenced the young Charles Deas who, in the 1840s, journeyed to the Rockies and painted Long Jakes, a portrait of a fur trapper whose half-wild, half-civilized appearance captured the essence of the frontier.

In the 1870s, Albert Bierstadt attempted to convey in visual terms what Romantic poets like Shelley, Byron, and Wordsworth captured in verse: Nature as a religious experience, offering moral lessons for mankind. Although wildly popular, Bierstadt had his critics. “I believe this atmosphere of Bierstadt’s is altogether too gorgeous,” complained Mark Twain. “I am sorry the Creator hadn’t made it instead of him.”

In the late 1800s, a new fascination with realism emerged. In 1871, English-born Thomas Moran joined the Hayden Survey to Yellowstone. His paintings helped get the park established and paved the way for artists Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, who recorded a frontier way of life that is now all but gone.

Immigrant heritage

As gold and silver mining developed from small one- or two-man diggings into large-scale industrial operations, immigrant laborers were hired to do the dirty work. At first, the majority were Chinese workers, who brought experience from the earlier gold rush in California (Asian Americans living in Colorado today make up just 3.1 percent of the population). Most left because of widespread persecution that culminated in the Anti-Chinese Riot of 1880. Starting as a bar brawl, the incident escalated into a mob of more than 2,000 rampaging through Denver’s Chinatown, burning businesses and lynching at least one Chinese man. After that, mine and railroad jobs were filled mainly by Welsh, Cornish, and Italian workers.

The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas, by George Caitlin.

Public domain

A more lasting impact on Colorado’s cultural landscape came with the trainloads of German-speaking immigrants from the Volga River region of Russia, who began arriving in 1880 and homesteading farms in the northeastern part of the state, growing root vegetables and winter wheat. Within two generations, many of Colorado’s prominent politicians and industrialists were Russian Germans. Their greatest contribution was the introduction of sugar beet farming, one of Colorado’s most important industries from 1900 to the 1960s. Most small farmers moved to the cities and towns of the Front Range during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, but few left the region. Today, white residents reporting German ancestry make up 22 percent of the state’s population.

The largest group by far are Latinos or Hispanics, commonly referred to as “Mexicans” even though their ancestors may have lived in Colorado for generations, and only three-quarters of Latinos in Colorado are actually from Mexico. As small sugar beet farms gave way to big, labor-intensive agribusiness operations, migrant labor crews were brought from Mexico. These “contract families” were encouraged to stay in the region year-round and soon developed large barrios in Denver and elsewhere. Today, one in five Coloradans (and more than one in three Denver residents) is Latino. Cinco de Mayo (May 5), the annual celebration commemorating the end of French rule in Mexico, is one of Denver’s biggest festivals.

The dark side of diversity

Minorities in Colorado have often been met with intolerance, bigotry and even violence. One obvious example is American Indians – the Ute, Navajo, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, and other tribes that inhabited the region for countless centuries. Today, the percentage of American Indians in Colorado is a shade higher than the percentage for the United States overall (1.6 percent) but less than in any other Rocky Mountain state. Why?

On the eastern plains, the prevailing attitude toward Indians in the mid-19th century was expressed by John Chivington, the Methodist minister, political hopeful, and Colorado Militia leader who led the Sand Creek Massacre, in which some 150 unarmed Cheyenne Indians – most of them women and children – were slaughtered in 1862. “It simply is not possible for Indians to obey or even understand any treaty,” Chivington said a few months before the massacre. “I am fully satisfied, gentlemen, that to kill them is the only way we will ever have peace and quiet in Colorado. I say that if any of them are caught in your vicinity, the only thing to do is kill them.”

Nearly a third of the cowboys in the American West were African American.

Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

Because of the massacre, Chivington was court-martialed by the Army but honored with a parade through the streets of Denver and awarded a medal of honor by the territorial governor. Within less than 10 years, all Indians had been removed from Colorado Territory except for the Southern and Ute Mountain people, whose reservations lie along the southwestern state line. Curiously, in 1992 Coloradans elected the first American Indian to serve in the US Congress in 60 years. Republican Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell was not a native Coloradan; like many of his constituents, he moved from California. He represented Colorado from 1993 to 2005.

Chinese miners in the Edgar Experimental Mine near Idaho Springs, about 1920.

Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

By the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had become a powerful force in Colorado. The Denver Post reported that “the KKK is the largest and most cohesive, most efficiently organized political force in the state.” In 1924, riding a wave of anti-immigrant (particularly anti-Mexican) sentiment, Klan leader Clarence Morley was elected governor of Colorado by a landslide. That same year, Klansmen became secretary of state and mayor of Denver, were appointed to the state Supreme Court and seven benches of the Denver District Court, and won a majority of seats in both houses of the state legislature. In the next legislative session, 1,080 Klan-sponsored bills were introduced, but almost all of them were killed in committee by Billy Adams, a Democrat who would later take Morley’s place as governor. Coloradans, it seemed, quickly got fed up with the Klan’s overzealous enforcement of Prohibition laws.

Peach picker in Palisade.

Carol M Highsmith

Molly’s crusade

As with most things Coloradan, intolerance was met with a counter-movement to encourage progressive attitudes, as illustrated by another of the state’s mining camp legends. Thanks to a hit Broadway musical and motion picture, most people in the US know the rags-to-riches story of Margaret “Unsinkable Molly” Brown’s rise from a one-room shack in Leadville to a Denver mansion where she reigned as a leading philanthropist, and how she survived the Titanic disaster. What fewer people realize is that she also campaigned for an Equal Rights Amendment and ran for the US Senate three times – all before women had voting rights in most states. (In 1893, Colorado had become the second state to give women the right to vote and hold office, and the first to do so by amending the constitution in a general election in which only men could vote.) In an effort to encourage racial harmony and understanding, Molly Brown sponsored a Carnival of Nations in 1906, donating funds to representatives of 16 ethnic minorities in Colorado, including American Indians, to build “villages” in a Denver park showcasing their native culture, food, arts, and crafts. The two-week festival was an enormous success, though it has never been repeated.

According to 2014 US Census figures, 37.5 percent of Coloradans have an undergraduate college degree or higher.

In recent years, intolerance and prejudice have occasionally resurfaced. Colorado suffered national notoriety in 1992 when conservative Christian organizations sponsored a ballot measure prohibiting “special rights” for gays and lesbians. Designed to block ordinances such as those adopted in Boulder and Aspen that banned discrimination on sexual preference, the amendment passed with 53 percent of the vote. It prompted a nationwide effort on behalf of the gay community to boycott Colorado tourism, costing the state’s hospitality industry an estimated $40 million. The Colorado Supreme Court eventually ruled the amendment unconstitutional, a decision upheld by the US Supreme Court. Although feelings still run high on both sides of the gay rights issue in Colorado, the boycott had at least one positive impact. The Adolph Coors Company, whose beer had been boycotted by gays as a Colorado symbol, began giving health insurance and other benefits to same-sex partners of employees in 1994 and launched an aggressive campaign to demonstrate its support for gay rights through advertising and donations to gay pride organizations. Coors also sponsors the Colorado Gay Ice Hockey League and funds all three teams in the league.

Meanwhile, much of the above has become moot, because Colorado’s state constitutional ban on same-sex marriage was struck down in the state district court on July 9, 2014, and by the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado on July 23, 2014. As of October 7, 2014, same-sex marriage has been legal in Colorado. In June 26, 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell vs. Hodges that state-level same-sex marriage bans are illegal, and it became the law of the land throughout the United States.

Fly-fishing in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Changing faces

Today, more than four out of five Coloradans live in the Front Range metropolitan areas; updated US census data for the state in July 2015 indicated a 8.6 percent increase in residents from the 2010 census, to an estimated population of 5,456,574. Even there, the cultural climate is contradictory and as changeable as the weather. Colorado Springs, for example, is notorious for its conservatism. Local attitudes are shaped in part by a large military presence and by outspoken fundamentalist religious groups. Just off the interstate, not far from the US Air Force Academy, the Focus on the Family Welcome Center greets travelers with cautions about such errors as sparing the rod and spoiling the child. Even the mansion built by General William Jackson Palmer, the city’s founder, is now owned and occupied by Christian evangelists.

Power politics in the new west

With its soaring Latino population and high-tech growth, the Front Range symbolizes the new politics of the Interior West. Once political flyover territory, the region has played a key role in securing Democratic victories in several previous elections. In 2008, Democratic candidate Barack Obama accepted his party’s presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Denver, and the state was a hotly contested battleground in his re-election in 2012..

The fiery 2010 midterm elections offered a case study in Colorado’s flip-flop politics . Democratic candidate Michael Bennet, appointed to fill the old senate seat of Colorado-born Ken Salazar, secretary of the interior during President Obama’s first term, narrowly beat Ken Buck, a Republican backed by the Tea Party, an anti-government grassroots organization with roots in the 1970s Sagebrush Rebellion. Strong support from college-educated women and Hispanics led to Bennet’s win – a model successfully adopted by the 2012 Obama re-election campaign.

Bennet retained his seat in 2016 unopposed, but Colorado politicians’ tendency to appeal to disgruntled voters is still clear. While Colorado remained Democrat in the hotly contested 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump – eventual victor and advocate of an unmistakeably reactionary rhetoric – won a hefty 44.4% of the vote.

At the other end of the Front Range Corridor, the university town of Boulder is known as a hotbed of left-wing politics and one of the West’s New Age centers. Its top visitor attraction is Celestial Seasonings, an herbal tea empire, and numerous other small family-run outdoor and eco-business enterprises can be found here. Downtown, on the Pearl Street Mall, you’ll find a store that carries only left-wing political books and, a few blocks away, another that specializes in books for lesbians.

It’s a wonder the two cities can exist in the same state. But then, generalizations don’t always hold water. If you visit the Colorado Springs suburb of Manitou Springs, for instance, you’ll find an artist colony regarded as the state’s oldest “hippie” community. In Boulder, on the other hand, the intellectual University of Colorado atmosphere provides fertile ground not only for liberal thought but for such groups as the ultra-conservative America First Party and Soldier of Fortune magazine, which has sponsored clandestine training camps for Third World police officers in the nearby mountains. At a Pentecostal book-burning in Boulder, copies of such New Age tomes as Shirley MacLaine’s Out on a Limb and Barbara Marx Hubbard’s Happy Birthday Planet Earth were pitched into the flames before the event degenerated into a shouting match with protesters.

Skiing fresh powder is a real thrill.

123RF

Environmental politics

Attitudes among urban dwellers, many of whom are transplants from the West Coast, often conflict with those of traditionally conservative old-timers. This is especially true in the realm of environmental protection. Activities such as mining, ranching, and logging have taken a back seat to the recreational use of Colorado’s vast public lands.

The trend was accelerated in 1992 when voters passed a constitutional amendment known as GOCO (Great Outdoors Colorado). The law earmarks proceeds from the Colorado Lottery for “trail construction, the purchase of parks and park enhancement, open space, wildlife and river preservation, and environmental education,” providing more funds for environmental causes than almost any other state. Since its inception, it has awarded more than $917 million in lottery funds for 4,700 projects in all 64 counties in Colorado.

Outdoor sports have become integral to Colorado’s economy, not only promoting year-round tourism but also attracting new residents. Though they are most likely to find employment with high-tech companies along the Front Range, most new residents cite recreation as their top reason for relocating, not jobs. Recreational opportunities range from huge events like the Bolder Boulder Marathon, in which more than 50,000 runners participate, and world-class athletic competitions such as Telluride’s Extreme Ski Week and Durango’s Iron Horse Bicycle Classic, to solitary expeditions into high-mountain wilderness.

Recreation has also spawned a new breed of legendary figures as colorful as any from the gold rush days. Future generations may commemorate such heroes as Friedl Pfeifer, the European ski instructor who in the late 1940s came up with the crazy idea of building Colorado’s first ski slope near a down-and-out mining town named Aspen. Or Neil Murdoch, who invented and popularized the sport of mountain biking while hiding out in Crested Butte under an assumed name, dodging a federal warrant for an alleged drug offense, for 25 years (he has since disappeared).

And then there’s Sandy Glade, still going strong after more than 30 years. Now her line of Colorado bumper stickers numbers more than 50. Still revealing a lot about contemporary Colorado culture, they include “MARATHONER,” “MOUNTAIN BIKER,” “RIVER RUNNER,” “CATCH & RELEASE,” “SKIER” and, perhaps most telling of all, “SAVE AN ELK – SHOOT A LAND DEVELOPER.”