A Heinkel He 59; the Luftwaffe’s first multipurpose torpedo bomber.

KAPITÄNLEUTNANT FABER REMAINED CONVINCED of the validity of maintaining a naval air service despite a general disinterest by the naval staff, who considered capital ships to be the pre-eminent weapon and aircraft merely a reconnaissance tool. Faber was made a head of department within the Reichsmarineamt Air Transport Section, while also acting as a member of the Air Peace Commission established by the Reichswehr to liaise with the Inter Allied Aeronautical Control Commission tasked with overseeing the disarmament of all German aerial forces and root out any transgressions of the Treaty terms. Nevertheless, he firmly held the six aircraft that he had managed to spirit away beyond the reach of Allied observers, and by 1921 had fifteen trained pilots included within the Reichsmarine ranks; a paltry number, though important for the maintenance of any hope of resurrecting a naval air arm.

At this juncture the seaplane ace and one-time commander of Zeebrugge’s naval air station Leutnant Friedrich Christiansen, credited with thirteen victories, encouraged covert development of a maritime aircraft by a man whose name would soon to be synonymous with Luftwaffe air power, Ernst Heinkel. Born in Grunbach, Baden- Württemberg, Germany, Heinkel had long harboured a fascination with flight as the future of transportation, and after constructing his own aircraft in 1911 went on to work at Albatros, playing a major role in the design of the Albatros B II reconnaissance and trainer aircraft. After leaving Albatros he worked as chief designer and technical director of the Hansa-Brandenburg company, creating land- and seaplanes from 1914 onwards. It was through this work that he first co-operated closely with Christiansen, who approached Heinkel as one of the Navy’s finest ‘aces’ for the development of faster and more manoeuvrable seaplanes than those already in service.

By 1921 Heinkel had been appointed head designer of the recently re-established Caspar-Werke, owned by former naval plot Karl Caspar, and Christiansen approached him to encourage the design of a small floatplane capable of being launched by submarine. In the Pacific, the Japanese-American arms race had begun, and both parties were interested in advanced German aeronautical designs, which also provided a means to circumvent Versailles restrictions, as the actual construction of these licensed designs could take place outside German territory. The Japanese naval attaché in Berlin, Araki Jirō, had already ordered illegal aircraft designs from Heinkel during 1921 (the HD 25 and HD 26 biplanes), while Christiansen successfully negotiated the construction of a seaplane named the ‘Caspar U 1’ for the US Navy (USN). This cantilever biplane was capable of being stored within a submarine-borne cylindrical container, reassembled in just over a minute on the surface and launched by catapult. Two U 1 prototypes were bought by the USN in 1922 for successful trials, in turn prompting the German Navy to purchase a single U 1 for its own tests. This was the first naval aircraft ordered since the imposition of the Versailles Treaty, and an important indication that perhaps naval aviation still garnered some interest within the upper echelons of the Reichsmarine. A second, improved design, the HS 1, was made for construction by the Swedish Navy, though arguments with Caspar over design rights led Heinkel to depart the company and establish his own design bureau, followed by a construction company, Heinkel-Flugzeugwerke, in a rented ex-naval hangar at Warnemünde. Heinkel concentrated on design work, his prototypes hidden in sand dunes near his construction hangar and out of sight of inspectors, while larger-quantity production took place at the Svenska AB Aero Works in Sweden. During 1924 Heinkel received orders for catapult aircraft, shipborne fighters and floatplanes from the Imperial Japanese Navy. After Heinkel once again warned the Japanese authorities of the ban on aircraft construction in Germany, the Japanese assured him that, as erstwhile enemies from the First World War and members of the Allied inspection commission, they would warn him of any pending inspections, allowing incriminating material to be secreted away. The Reichsmarine was already negotiating secretly with their Japanese counterparts to exchange technological information, which was also proving immensely beneficial to the reconstruction of the German U-boat service.1

Meanwhile, Faber had also begun the first small naval pilot training course in Stralsund during 1922 as part of the II Abteilung der Schiffsstammdivision Ostsee, a second intake being trained during the following year. In January 1923 French and Belgian troops occupied the industrial Ruhr region after the Weimar Republic announced its inability to meet expensive reparations payments demanded by the Versailles Treaty. Turmoil and the complete collapse of the German economy immediately followed, fuelling rage within Germany at the foreign ‘invaders’ and moving large tracts of the population to the political right wing. Faced with such aggression, the military also girded themselves for potential future conflict. As well as having accumulated nearly 100 million Marks in ‘black funds’ by the illegal sales of ships due to be scrapped under the terms of the Versailles Treaty, they took a portion of a secret ‘Ruhr Fund’ established by the German Cabinet without parliamentary knowledge to bolster the military beyond treaty limits. The Navy’s share amounted to 12 million gold Marks and, along with other small boosts to research and development, the Reichsmarine invested in Faber’s tiny maritime aviation unit, ordering the purchase of ten Heinkel HS 1 floatplanes from the Swedish Navy. Faber had even been granted a small staff of four men, and his office had been given its own designation of ‘AII1’ by the head of the Reichsmarine, Admiral Hans Zenker, responsible for all naval aeronautical issues. Faber’s AII1 office remained responsible for providing an air defence consultant for each major naval station and maintaining an up-to-date archive of reference material on all matters related to naval aviation; attempting to keep aerial matters in the minds of the Reichsmarine officers still otherwise rooted in fleet strategic thinking.

In the interim, the illegal monetary fund provided direct support for aircraft manufacturers Heinkel, Junkers, Dornier and Rohrbach (the latter two having established major aircraft plants in foreign countries), and for the purchase of the Caspar Works in 1926, which continued to develop commercial aircraft bearing an uncanny resemblance to fighter, bomber and reconnaissance types in use by other air forces. Among the designs thus developed was the prototype of the huge Do X ‘flying ship’, created by the Swiss subsidiary of Dornier; a twelve-engine giant larger even than the famous Boeing Clippers of Pan American, and planned to meet the requirement for a patrol seaplane capable of landing and refuelling at sea. Only an unacceptably low service ceiling made it necessary to abandon this design. The Dornier company had already produced a smaller, twin-engine flying boat which entered production designated the Do J Wal (Whale). The Wal was a highly successful design, used frequently by explorers and on the marine mail routes, crewed by three and capable of carrying up to ten passengers. It was powered by two piston engines mounted in tandem in a ‘push-pull’ configuration in a central nacelle on a parasol wing. The aircraft’s maiden flight took place on 6 November 1922 in Italy to circumvent treaty restrictions. Most of its production was also carried out in Italy until 1931, when the Wal began to be produced in Germany. The militarised version, designated Do 15, carried a crew of between two and four in an open cockpit in the forward part of the hull and had a bow-mounted moveable machinegun, augmented by one or two others amidships. The aircraft was soon on order for the naval air forces of Spain, Argentina, Chile and the Netherlands.

The illegal monetary boost also established the ‘civilian’ firm Severa (Seeflugzeug-Versuchsabteilung, or Seaplane Research Unit) for the development of naval aircraft types and pilot training at Norderney and Kiel-Holtenau. Founded in conjunction with the newly established government-sponsored national airline Deutsche Lufthansa A.G at an annual cost of 1.25 million Marks, Severa provided refresher courses for battle-experienced observer and pilot officers of the last war and trained new officer recruits as observers in a private naval aviation school created at Warnemünde. The ‘Communication Experimental Command’ located in the same facility also developed highly successful radio equipment for future military aircraft. Under the cover afforded by the newly established German Commercial Flying School (Deutsche Verkehrsfliegerschule, or DVS) for ‘civilian’ aircrew, the Warnemünde centre began training observers as well assuming responsibility for all boats and ships for use by naval aviation units. Between 1925 and 1926 Severa spearheaded development of seaplanes and their armament, slowly accumulating airfields and seaplane bases from which to expand its training regime, most notably the ‘Seaplane Testing Station for the United German Aviation Companies’ at Travemünde, headed by Kaptlt. Hermann Moll (retired). Officially, Severa was concerned with commercial flights and the transport of target drones for use by antiaircraft artillery units still permitted in the peacetime German military. However, these target flights simultaneously enabled the training of observers in reconnaissance techniques for use with the fleet. An average of only six pilots and observers were trained annually, though this still represented a genuine revival of the naval air arm. Naval flying schools were finally established at Warnemünde in October 1928 for the training of both pilots and observers, each course lasting for two years and hosting twenty-seven students in each intake. Aircraft testing was carried out at Rechlin and Travemünde.

An interesting distinction within the early German Air Force as opposed to others was that the observer was the commander of the aircraft, generally outranking the pilot. Therefore, their training was both varied and comprehensive as they were able to assume the duties of any other crewmen. They were trained pilots to ‘C’ standard, denoting 150 flying hours as pilot, before beginning observer training which included navigation by day and night, blind-flying techniques, gunnery and bomb-aiming. This high pre-war standard produced decidedly skilled aircraft commanders, but was relaxed after the outbreak of war in 1939, when the rule of the observer being senior officer was dropped and training was reduced incrementally over the years that followed as losses mounted on all fronts and the demand for replacements grew.

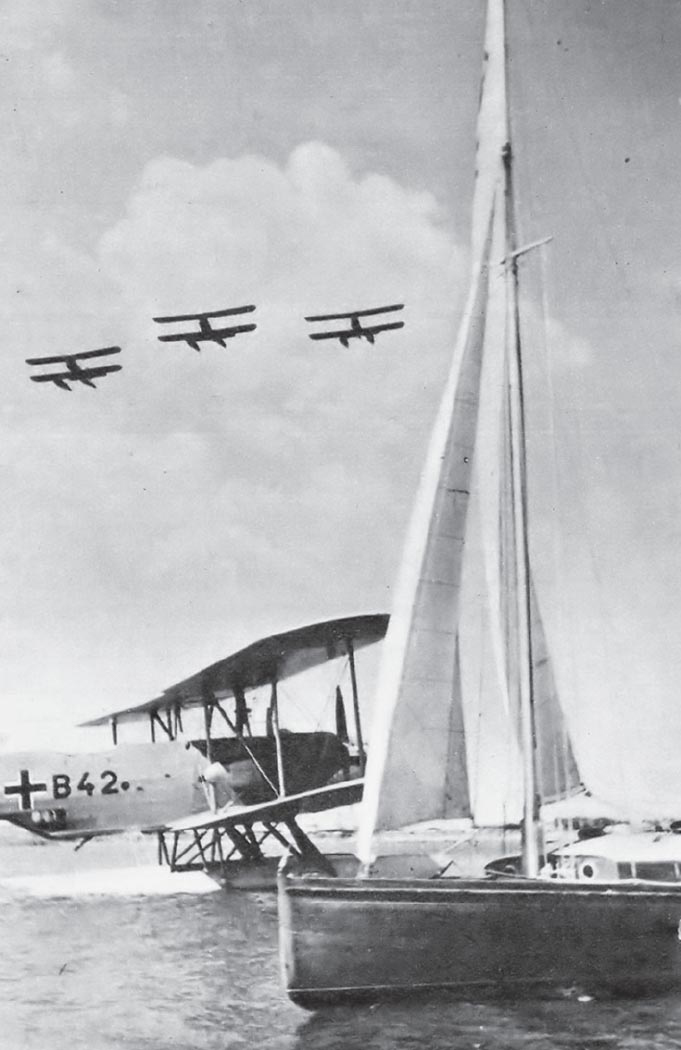

In 1929 Heinkel developed the HD 42 biplane for use with the covert military-training DVS. Its fuselage was a welded steel-tube truss and the engine cowling used lightweight metal, but the rest of the fuselage was fabric-covered. Equipped with floats, the HD 42 was sold to the Swedish Navy, which provided positive operational feedback. The aircraft was subsequently redesignated He 42 and secretly provided to the small naval air units disguised as the DVS.

In the wider sphere of Germany’s air forces as a whole, facilities for the covert training of pilots and observers had been established outside Germany’s borders. By 1926, with the strong support of Gen Hans von Seeckt, Chief of the General Staff, an agreement had been reached with Russia for training to take place at Lipetsk near Moscow, and in smaller centres within the expansive landscape of the Ukraine. Fifty Fokker D XIII aircraft were subsequently shipped by steamer from Stettin to Leningrad and then overland to the flying school. Within Germany’s borders, the number of private flying schools had blossomed, as had Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. pilot training centres, and by the end of the 1920s the German Air Sports Association (Deutscher Luftsportverband, or DLV) numbered over 50,000 members spread throughout various clubs. During 1930 the Nazi Party’s SA (Sturmabteilung, colloquially known as ‘brownshirts’, the paramilitary arm of the Nazi Party) established a flying branch, and the SS followed suit during the following year; both were Nazi Party-sponsored organisations and counted as auxiliary ‘police’ units when convenient for international observers. During 1932 the National Socialist Flying Corps was also established as a semi-civilian counterpart, though it was not regarded as a Party organisation despite its title, and in September 1933 the ‘Flieger SA’ and SS were absorbed into the DLV as a whole. Gliding, unrestricted by the Versailles Treaty, was also strongly promoted, with Hptm. Kurt Student of the Air Technical Branch organising courses in glider instruction, allowing fundamental aeronautics to be taught to prospective military pilots. Future fighter pilot Winfried Schmidt followed this path:

In 1933 I had the opportunity to fly with gliders, which pleased me a lot. The next year I joined a private aviation club, soon included in the Luftsportverband (LSV), created at that period to become the basis for the new (and still secret) Luftwaffe. In this club I was quickly promoted to flying powered aircraft. Still as civilians, we flew the Klemm 25. This aircraft was so light and slow that we were not authorised to start if the weather was too windy!2

The airline Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. was an important part of Germany’s aerial revival. Founded in Berlin on 6 January 1926, the company was the result of a merger between the small Deutscher Aero Lloyd airline (formed in 1923 by co-operation between shipping companies Norddeutscher Lloyd and Hamburg America Line) and Junkers Luftverkehr, the in-house airline of the Junkers aircraft company, both of which were virtually crippled with heavy debts and required the support of government funding. The merger was planned to reduce that required level of monetary assistance, and coincided with the lifting of restrictions on commercial air operations previously imposed by the original terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The Paris Air Agreement of 1926 relaxed restrictions on German aviation, cancelling technological limits on the quality of German commercial aircraft and allowing the construction of airships once more. In return, the Weimar government agreed to halt the subsidising of civilian aeroclubs. However, sturdy limitations remained on the training of military personnel:

Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring pictured at the first inspection of the newly created ‘Richthofen Geschwader’.

The German Government shall take suitable steps to ensure . . . That members of the Reichswehr or Navy may not, either individually or collectively, receive any instruction or engage in any activities in connection with aviation in any form.

That, as an exceptional measure, members of the Reichswehr and of the Navy may, at their own request, be authorised to fly or to learn to fly as private persons, but only in connection with amateur aviation and at their own expense. The German authorities shall grant them no special subsidies or special leave for the purpose.

It is to be understood that these exceptional authorisations shall . . . exclude all training in flying of a military character or for a military purpose.

Such authorisations may be granted up to a maximum of thirty-six. This maximum may only be reached in six years as from January 1, 1926, with the proviso that not more than six authorisations may be granted in any one year . . . Members of the Reichswehr and of the Navy who hold a pilot’s licence issued before 1 April 1926 may continue to act as pilots if they do not exceed the maximum number of thirty-six. These thirty-six pilots, who may not be replaced and whose names shall appear on a special list, are not included in the number of pilots referred to in the above paragraphs.

Nevertheless, as an exceptional measure, fifty police officers may be given aeronautical training and hold a pilot’s certificate. It is agreed that these pilot’s certificates will not be issued to the police officers to enable them to engage in aviation, but solely to enable them to acquire the technical knowledge required for the efficient supervision of commercial aviation.3

Though the ban on military aviation remained in place, a large measure of Germany’s air sovereignty had been restored, and many members of the military were covertly transferred to legitimate commercial flying schools. Lufthansa’s saleable route network expanded rapidly, soon to include the world’s first night passenger flights (necessitating long-range and ‘blind-flying’ training that would serve future bomber crews well), all under the auspices of the former managing director of Junkers Luftverkehr, the half-Jewish veteran observer of the Imperial Air Force, Erhard Milch.

During the 1920s and 1930s the Reichsmarine deliberately avoided joint aerial exercises or discussions on strategy and tactics with the German Army. Memories lingered of Army control over aircraft production during the First World War that had rendered naval squadrons unable to meet demands for modern machines, as did fears of the absorption of naval aviators into the Army.

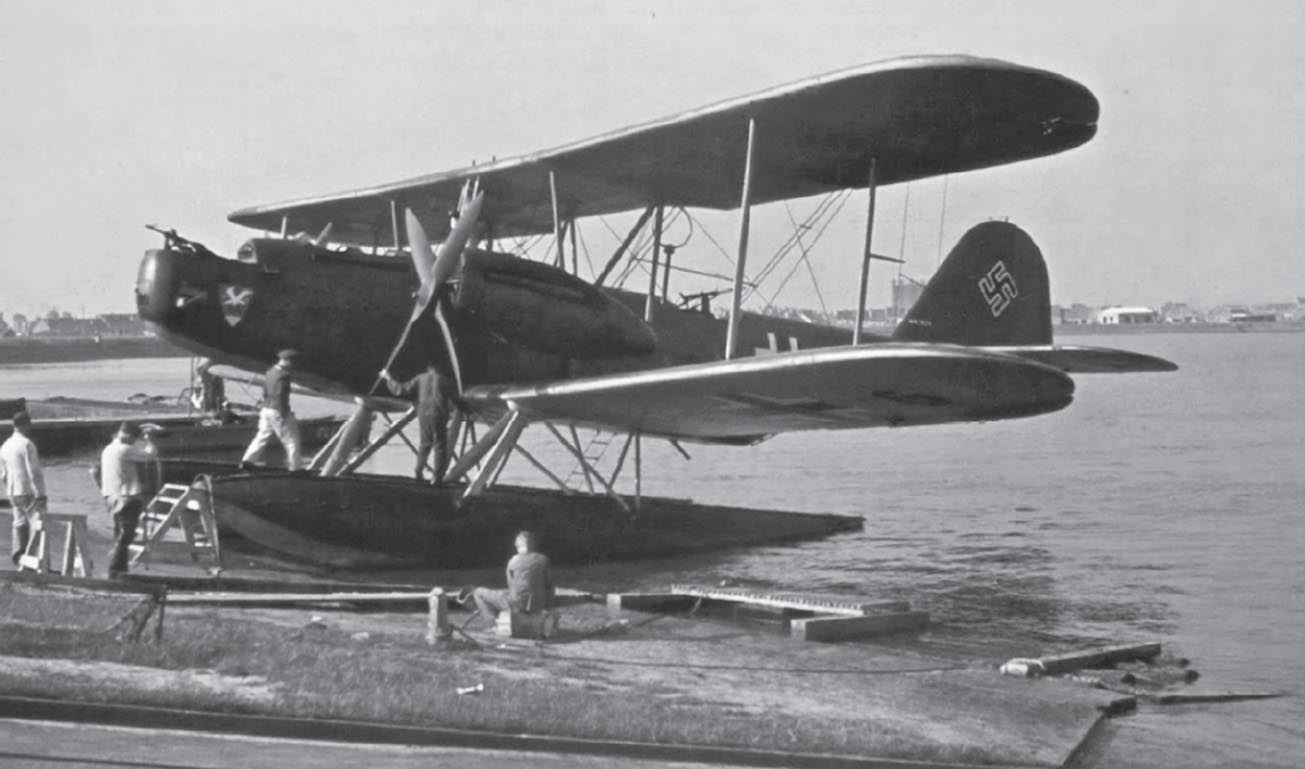

The Heinkel He 60, a successful two-seater reconnaissance aircraft initially designed for shipboard use.

However, by this time Faber was no longer involved as the head of AII1. He was transferred briefly to the post of navigation officer aboard the cruiser Medusa on 10 April 1923, until moved in June to the post of Referent Inspektion Torpedo-und Minenwesen, Kiel. There, his expertise was put to good use as he assisted in the development of air-launched torpedoes and mines. He was replaced at AII1 by Kaptlt. Hans Ritter (a former naval pilot), who was in turn superseded by Kapitän zur See Rudolf Lahs on 1 April 1928; the latter was a former torpedo-boat officer of no aviation experience. The office had increased dramatically in size and lay under the umbrella of the ‘Naval Transport Division’ commanded by Kapitän zur See Walter Lohmann, chief of the Naval Maritime Transport Department (Seetransportabteilung der Marine) and the man who had been tasked with both the accumulation of the naval ‘Black Fund’ and its distribution.

The AII1 office was expanded and renamed with Lahs’ assumption of command, now designated Gruppe BSx and sprouting a number of suboffices, many headed by men who would later become major luminaries within the Luftwaffe:

Military and Tactical: K.K. Hans Ferdinand Geisler (transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933)

Training: Oblt.z.S. Wolfgang von Gronau (replaced by Kaptlt. Ulrich Kessler, the latter transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933)

Technical: K.K. Joachim Coeler (transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933, replaced by K.K. Hans Siburg who also transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933)

Intelligence: Lt.z.S. Werner Bartz (replaced by K.K. Beelitz, a former Zeppelin officer).

During 1928 Lohmann was forced to resign from his post after it became publicly known that he had also poured money into various non-military ventures to bolster the dwindling secret fund. His ventures ranged from the Berliner Bacon Company (attempting to wrest the lucrative British bacon market from Danish firms) to a firm attempting to raise sunken ships by encasing them in ice. However, it was involvement with the Phoebus Film Company, which collapsed financially in August 1927, that compromised him. Lohmann’s stake in the company was revealed by investigative journalist Kurd Wenkel, though, somewhat paradoxically, it was not Lohmann’s backing of rearmament that scandalised the journalist, but rather the fact he had been influencing the film company to make increasingly nationalistic features supporting the burgeoning right-wing political parties.4 However, the cessation of Lohmann’s activities forced only a brief delay in the establishment of new business fronts behind which the military could continue its secret work. New Commander-in-Chief of the Reichsmarine, Admiral Erich Raeder himself pressed Chancellor Hermann Müller and the Reich Defence Minister, Wilhelm Groener, for authority to continue and was given the green light.

During the summer of 1929, clandestine naval air training was reorganised on Groener’s orders, the Defence Minister being intensely involved in secretly rearming the Weimar Republic. He informed Fleet Command on 1 September that:

The Coastal Air Section which had been guided by the Navy was dissolved in the latter part of April for considerations of internal foreign policy. The Navy has been able to make a contract with a private air company, the Luftdienst G.m.b.H., whereby the Navy will hire aeroplanes at a fixed hourly rate. The company has rented the (naval air) installations at Holtenau and Norderney . . .The Luftdienst G.m.b.H. personnel are available only for duties which can be considered permissible in terms of the Paris Agreement of 1926 (target flight, towing of targets). For all other duties, that is especially for gunnery observation and for the direction of naval guns, naval personnel are to be assigned to the aeroplanes as observers.5

Erich Raeder, Commanderin- Chief of the Kriegsmarine until 1942 and champion of an independent naval air arm, though he perhaps never truly appreciated its potential.

Only eight aircraft were to be available at any given time, although the new directive guaranteed that 3,000 flying hours were to be available at a price to the Navy of 4.53 Reichsmarks per hour; additional hours available at 70 Reichsmarks. The hours were divided between three separate stations: Baltic, 950 hours; North Sea, 1,550 hours and Naval Command, 500 hours. While at face value the limitations appeared undesirable to the naval air service, they yielded more flying hours than had ever been available previously, and helped established a small but well-trained cadre around which to continue developing the service branch. By the summer of 1930, despite complaints from the British and French embassies at the apparent German abrogation of previous agreements, the Reichsmarine was able to select and train a small number of air cadets annually.

On 20 September 1929, Kapitän zur See Konrad Zander, a career naval officer and former torpedo-boat commander from the First World War, took command of Gruppe BSx, which was subsequently renamed Gruppe LS. His official title was Director of the Air-Protection-Group, Naval Command (Chef der Abteilung Luftverteidigung der Marineleitung), and as such he brought his considerable energies to bear on refining the training regime already established for the small naval aviation wing. He lengthened the training period for new pilots from six months to a year, and that of observers from a single year to two. Zander concentrated on refining the training itself to achieve greater efficiency per Reichsmark spent, and succeeded in no small measure. He also created training courses for flight engineers, radio operators and ground crew personnel, further underlining the Navy’s desire for a genuinely autonomous service, separate from the growing strength of the developing air force. In January 1931 the first formalised regulations for the co-operation of fleet and naval air units were issued; the aircraft were referred to as ‘motor tenders’ to disguise their true nature.

Zander was relocated to the post of Inspector of Torpedo and Mine Affairs in October 1932, though he would later figure prominently in the continuing development of the naval air service. Former U-boat commander Fregattenkapitän Rudolf ‘Ralph’ Wenninger took his place, and by the time of Zander’s exit a multipurpose aircraft for the dropping of bombs, mines and torpedoes, the Heinkel He 59, had been developed alongside the He 60 reconnaissance/fighter floatplane.

A large, twin-engine biplane with a crew of four, the He 59 was constructed under the cover of being a maritime rescue aircraft, but in fact it was a versatile reconnaissance bomber capable of operating from both land and water. The aircraft possessed high endurance, an ample bomb load and powerful armament, and demonstrated dependable seaworthiness. The initial prototype, the He 59A, flew in September 1931 with a wheel undercarriage, but subsequent versions were all fitted with floats, beginning with the He 59B-1, of which sixteen were built, one being taken to Lipetsk in Russia for testing in January 1932. The subsequently improved He 59B-2 was the first model placed into major production. The first sixteen were built by Walter Bachmann’s aircraft production firm based in Ribnitz, which specialised in seaplanes. A glazed nose that had been provided for the bombardier was replaced by a smaller glazed bomb-aimer’s position, and all-metal construction was employed.

The Dornier Do 18, an improvement on the previous Wal that was used to provide long-range reconnaissance during the early years of the war.

The He 60 single-engine, two-seat biplane reconnaissance aircraft was intended for launch by shipboard catapult, and the original prototype flew in 1933. However, the 660hp BMW V1 engine was found to be underpowered for the heavy airframe, resulting in sluggish handling. A second prototype equipped with a 750hp version of the same engine offered no significant improvement, so the final production model, the He 60C, reverted to the original powerplant. Aircraft were delivered for training purposes during 1933, and the next year the type began to equip front-line units, including on-board aircraft of Bordfliegerstaffel 1./BoFl. Gr.196. The He 60 was of similar mixed construction to the He 59. Both types were designed in 1930 by the talented engineer Reinhold Mewes, who had accompanied Heinkel on his departure from the Caspar Works.6

The Reichsmarine had also begun testing dive-bomber designs, and Kiel’s Deutsche Werke had constructed a prototype shipboard catapult, the K1, under Ernst Heinkel’s direction. Heinkel had already developed a catapult for the Japanese Navy which had been successfully installed aboard the battleship Nagato, and his new construction was fitted aboard a small scow for testing purposes (designated Schleuderprahm 11). It propelled an He 60 successfully into the air during trials in Travemünde. An improved catapult model, K2, was the first to see active use. Heinkel himself had overseen the catapult’s successful operation on 22 July 1929, when an He 12 mailplane was launched from the liner SS Bremen on its record-setting maiden transatlantic run, a 110-kilometre flight to New York Captain Joachim von Studnitz and wireless operator Willi Kirchhoff. Lufthansa subsequently installed a K2 aboard their catapult ship Westfalen within the North Sea, where it was used in conjunction with a Dornier Wal flying boat.

While this progress was gratifying, the Achilles Heel of German maritime aircraft operations would later prove to be the torpedo to be carried into action. In 1934 the Reichsmarine were latecomers in developing a 45cm aerial torpedo after purchasing the patents of the Horten Naval Torpedo from Norway, short-sightedly reasoning that there was little naval application for a torpedo of that diameter, as opposed to the 53cm version found aboard surface ships and U-boats. Manufactured by the German firm ‘Eisengießerei und Maschinen-Fabrik von L. Schwartzkopff’, the LT (‘Luft Torpedo’) F5 entered service with the maritime flying units, carried by the He 59.7 The 650kg weapon had limited drop-parameters, requiring the carrying aircraft to not exceed 75 knots (140km/h) airspeed and be at a height of between 15 and 20m from sea level. A minimum water depth of more than 23m was required for the torpedo’s initial drop, which negated all effectiveness in shallow coastal waters such as found on Great Britain’s North Sea coast. With a range of 2,000m and maximum speed of 33 knots, the torpedo carried a 200kg Hexanite explosive warhead. However, the marked lack of co-operation between the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe frustrated the testing of the design, and it was spectacularly unsuccessful, as the Luftwaffe would soon discover in action in Spain. It is difficult to say whether the Torpedo Experimental Institute (TVA) and the Kriegsmarine’s own Torpedo Department simply lacked the initiative to concentrate on developing the torpedo, or whether they were preoccupied by the G7 steam and electric models for U-boat use which, ironically enough, also suffered from major design flaws that rendered them almost completely unreliable. For its part, the Luftwaffe still failed to see the true value of the aerial torpedo, believing that the same results were achievable using less-costly bombs equipped with different fuse combinations. Their reasoning was also, no doubt, fuelled by the thought that such an approach would also lessen the need for specialised torpedo training on the behest of the Reichsmarine, which they jealously believed could diminish their hold on maritime air operations. However, with its shortcomings not yet evident, plans were instituted to amass a stockpile of 600 LT F5 torpedoes by 1939. In the event, war began with a stock of fewer than 100 and only five to ten new models being produced each month.

Nonetheless, Zander’s groundwork had set the Naval Air Service on firm footing for the moment when Hitler assumed power in 1933 and made German rearmament a matter of the highest priority. The majority of militarily advanced countries included air power within both the navy and army; each arm of service responsible for its specialised training requirements. Perhaps the most notable examples of these were the Japanese, American and French armies and navies. Great Britain, on the other hand, had established an independent air service in 1918; the Royal Air Force, created by an amalgamation of the British Army’s Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. Other commonwealth countries such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand subsequently followed suit, as did Egypt, Brazil and Finland. Göring’s desire for a similarly independent service posed significant problems for Raeder’s navy.

It has been consistently held by all the larger navies that naval components, whether surface ships, submarines or air forces, must be controlled by a single commander-in-chief, and for this reason naval air forces must be an integral part of the navy. In Germany, Air Force General Göring and his circle had made the repeated assertion: ‘Everything that flies belongs to us!’ Such a concentration could have advantages in engine development, general flight training, and industrial expansion, but the proponents of the Göring thesis apparently could not realise that the employment of aeroplanes and air forces in land warfare is totally different from their employment in naval warfare. On land, the attack and defence will be predicated on the principles of land warfare, and hence the pilot must be a master of the methods and tactics of land warfare. Naval warfare requires men, machines, and tactics especially fitted to the techniques of sea combat, only here the requirements are more difficult to fill, since the element of water is so utterly different from the element of earth. The resulting tactics and methods are so different that only flyers trained in the tactics of naval warfare and trained in the ways and idioms of the sea can be really useful in naval operations.8

Furthermore, Raeder noted that one of the primary advantages offered by naval-trained pilots and crew was the facility offered by long-range reconnaissance; far beyond the visual reach of surface craft and U-boats.

A single observer’s report often changes the whole position of his commander-in-chief. A prime essential in such a reconnaissance report, therefore, is its accuracy . . . Such reports are the result of extensive training and long experience . . . Accordingly, up to 1933 our naval flyers had been trained with these things especially in mind and had become familiar with naval doctrine by living constantly within the Navy.9

On 8 January 1933 the new Reichswehr Minister, von Blomberg, had amalgamated both the Army and Naval flying staffs into the Reichswehr under the cover name ‘Luftschutzamt’. However, at the end of the month Hitler was appointed to the post of Chancellor, and in turn also selected a man to assume the newly created post of Reich Minister for Air; officially tasked with the maintenance and expansion of German civilian aeronautics, but in reality primarily concerned with the continued development of the air force as an independent branch of military service. Hermann Göring, a former fighter pilot and holder of the Pour le Merité, was the man appointed to take charge, and he threw himself into the role with vigour. Göring had distinguished himself as both a pilot and the last leader of Jagdgeschwader 1, the unit made famous by its original commander, Baron Manfred von Richthofen. In 1922, after meeting Hitler for the first time, he joined the Nazi Party, and by 1933 he had already commanded the SA to considerable effect, been named Interior Minister of Prussia and President of the Reichstag. The Göring of the mid-1930s was not the same person who, as a child, had railed against the discipline of his boarding school until removed from it, as a teenager had scaled peaks in the Alps, and as an adult had been credited with shooting down twenty-two enemy aircraft during the First World War. Arrogant, highly intelligent and ruthless, Göring was shot in the leg in the failed 1923 ‘Beer Hall Putsch’, in which the Nazis had first attempted to seize power, and subsequently became a morphine addict following surgery, remaining so for the rest of his life. His post-First World War weight gain escalated, and by the time that the Nazis had achieved power he was corpulent and frequently ridiculed for his vanity, outlandish costumes and narcissism. However, his political acumen was considerable, and initial popularity with the Führer assisted his consolidation of both political and, with command of the new Luftwaffe, military power. The vainglorious Göring would soon become the bane of the German Navy as he worked tirelessly to bring everything that flew within Germany under his control, his personal animosity towards the aristocratic head of the Reichsmarine, Erich Raeder, compounding an already bitter struggle for ownership of Germany’s aerial forces.

The two-man crew of an He 60 preparing to board their aircraft.

Raeder was almost the polar opposite of Göring. Born in Schleswig Holstein to an authoritarian headmaster and his wife, daughter of a royal court musician, the young Raeder was taught to value thrift, cleanliness, discipline and the fear of God above all else. Entering the Imperial Navy at the age of 18, he rose rapidly in rank due to his diligence and application, including two years on the staff of Prince Heinrich of Prussia. Although he was deemed aloof and even ‘cold’ by those closest to him professionally, his undoubted aptitude for naval leadership led him to serve as Chief of Staff to Admiral Franz von Hipper, a proponent of the creation of a ‘balance fleet’ centred on battleships that would serve as a deterrent to the risk of war with Britain. This theory never left Raeder, who rose to command the Reichsmarine in October 1928 and steered its rebuilding programme in that direction. Punctilious, diligent and a devout Christian, Raeder was singularly unequipped to deal with the nature of political manoeuvring that would dominate the Third Reich in both civilian and military matters, and his opposition to Göring over matters of a naval air arm was doomed to failure from the outset.

Of all the men close to Hitler, however, Göring was the one with whom I had my most violent battles . . . While he might have been a brave and capable flier in World War One, he lacked all the requisites for command of one of the armed services. He possessed a colossal vanity which, while amusing to some, and pardonable if it had been associated with other more significant qualities, was dangerous because it was combined with limitless ambition.10

Though the newly created Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM, Reich Air Ministry) comprised barely more than Göring’s personal staff, Blomberg relinquished control of the combined Army and Navy flying staffs and ordered the incorporation of the Luftschutzamt into new Ministry. This could arguably be considered the birth of the Luftwaffe, as all aerial components now rested under the control of Hermann Göring. He, and those senior officers who assisted in the establishment of the Luftwaffe (all of them former Army pilots or staff), maintained that the art of flying remained of primary importance to prospective pilots and crew; specialist training, such as that required for nautical operations, was a secondary consideration. This distinction would have wider ramifications on the entire future of what had seemed a promising German naval air service. At the creation of this new independent branch of service, the newly appointed staff included an office designated Abteilung 1 and headed by Oberst Eberhard Bohnstedt, with Fregattenkapitän Rudolf Wenninger as his Chief of Staff. The office was further subdivided into two subsections: L1 (Army) and L2 (Navy), prescient observers being able to discern future Luftwaffe control over all air activity. A conference held during December between the Naval Staff and the Air Ministry failed to reach accord on the boundaries of control over naval air units, as each side issued opposing directives entrenching their own positions. Coincidentally, on the other side of the hill, the Royal Navy found itself in a similar position until 1939, when the Fleet Air Arm (established by the RAF in 1924 to encompass aircraft carried aboard ship) was returned to Royal Navy control. The RAF’s Coastal Command, responsible for maritime patrols, suffered from severe disregard until as late as 1943, being neglected in favour of purely land-based and aerial doctrine.

On 22 January 1934 the Naval Staff issued a proposal that the Luftwaffe be composed of three parts: Operational Air Force, Army Air Units and Naval Air Units. Of these only the first would remain under the singular authority of the Reich Air Ministry, while the latter two would be commanded by officers of the respective service, with material and men provided by Göring’s ministry. For the naval aviation unit, an officer designated Führer der Marineluftstreitkräfte (F.d.Luft, Commander of Naval Air Forces) would be appointed by Göring and transferred to the command of the Fleet. The proposal was ignored and answered with a counter-initiative.

While the controversy of control continued, Göring, with former Lufthansa executive Erhard Milch appointed his deputy, speedily continued to consolidate the power of the fledgling air force, and the Luftwaffe came into being as an independent air force on 15 May 1934, albeit still under the camouflage required by its contravention of the Versailles Treaty. With the Minister frequently absorbed by his political appointments, it often fell to Milch to organise the distribution of increased though still covert aircraft production, and he vehemently opposed the allocation of any bomber or fighter units to the navy. Interestingly, from the 1934-35 production schedule of a planned 4,021 aircraft, the majority were trainers, obviously with the rapid expansion of the air force in mind, closely followed by land-based aircraft.

Elementary Trainers — 1,760

Operational Type (Land) — 1,714

Miscellaneous (including experimental bomber types) — 309

Operational Types (Coastal) — 149

Communications — 89.11

Pre-war Heinkel He 59 overflying one of Germany’s capital ships during exercises in the North Sea. (James Payne)

Reinhard Hardegen photographed here later in his career as a highly successful U-boat commander, still wearing the Luftwaffe Observer’s badge following pre-war service in both 1./Kü.Fl.Gr.106 and 5./Bo.Fl. Gr.196.

Nevertheless, by December 1933 Raeder was able to muster two squadrons as part of his naval strength: Seefliegerstaffel Holtenau (cover-name ‘Luftdienst e.V.’) and Seefliegerstaffel List (cover name ‘Deutsche Verkehrsfliegerschule GmbH, Zweigstelle List’). Furthermore, the navy controlled the training schools Seefliegerschule (pilot school) Warnemünde I and II (cover name ‘Deutsche Verkehrsfliegerschule GmbH, Warnemünde’), Beobachterschule (observer school), Warnemünde and the Bomberschule See (maritime bomber school) in Bug near Rügen, as well as the testing facility Seeflugzeugerprobungsstelle (S.E.S) in Travemünde. Interestingly, one of the early officer cadets (Offizieranwärter) of the Crew 33 that received training at Warnemünde was Reinhard Hardegen, who qualified first as an observer and later a pilot, serving in the naval air arm until 1939 and his transfer to the U-boat service.12

On 1 April 1934, Göring established six regional Luftwaffe commands; Luftkreis I – VI. Outwardly, they were to control civilian aviation throughout Germany disguised as Gehobenes Luftamt, but in reality they allowed the founding of a co-ordinated Luftwaffe command structure. In Kiel, Luftkreise VI was founded, its geographic location making this office responsible for co-operation with the navy. At the head of the regional Luftkreiskommando VI was the returning Konteradmiral Konrad Zander (designated Inspekteur der Marineflieger), transferred to the Luftwaffe and promoted Generalmajor in March 1935. Under his remit were all flying units, ground organisation and air defence of the German coastal areas, as well as taking charge of all ships and boats that had been used by the German Commercial Flying School (DVS) at Warnemünde, which now operated under the office of Luftzeuggruppe VI (See). Zander was immediately subordinate to Göring as Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief in every respect. However, regarding training, equipment, maintenance of both personnel and materiel, and shipboard and carrier aircraft units, Zander was referred to the corresponding departments within the Kriegsmarine chain of command. His Chief of Staff was named as Fregattenkapitän Otto Stark. On 1 July the new post of Führer der Marineluftstreitkräfte (F.d.Luft, redesignated Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte on 27 August 1940) was commissioned in Kiel. Its purpose was to facilitate proper liaison between air force and navy as officer in command of the flying units. Initially a post subordinate to Zander, and thus two steps from Göring, in wartime the F.d.Luft was tactically subordinate to the Kriegsmarine’s Fleet Command (Flottenkommando) and was occupied at the outset by Oberst Hans-Ferdinand Geisler, a veteran of the First World War naval squadrons before transfer from the Reichsmarine to the Luftwaffe in 1933.

Meanwhile, on 11 January 1935, naval command placed before Göring the following proposal for the effective training of officer observers (who also served as the on-board commanders of the aircraft) drawn from the navy for service in the naval air forces:

Three years’ normal officer’s training;

Three years’ experience at sea as Leutnant and watch officer aboard small vessels;

Three years’ command with naval air units as an observer.

After the final three years, 20 per cent of these men could volunteer for service with the Luftwaffe, while the remaining 80 per cent would return to the navy, all naval aviation units’ senior officers to be drawn from the ranks of the men who opted for Luftwaffe service. Göring received the proposal without comment, as the unveiling of the new Wehrmacht would soon take place and he had already outmanoeuvred his naval counterpart.

Raeder later submitted an amended proposal regarding the training of observers for naval aviation units, asking that 100 per cent of observers in such units be naval personnel. This was to be the objective by 1940, though in the intervening period a shortfall of fully trained men would be assuaged by naval officer cadets beginning observer training immediately following their final officers’ examinations. The Reichsmarine would make good the loss of personnel by their transfer to the Luftwaffe by recruiting an additional 140 officer cadets every year.

However, this proposal also failed to meet with Luftwaffe approval, and a counter-proposal was similarly refused by Raeder. Regardless, the Luftwaffe expanded its training syllabus to include aspects of naval warfare essential for any meaningful contribution to naval aviation. In a co-operative spirit, the Reichsmarine founded a small staff of instructors to provide specialised training to existing combat units in naval tactics, ship recognition and the basic principles of naval strategy. The aerial exercises over German coastal waters that followed were conducted primarily by Lehrgeschwader Greifswald (Greifswald Training Wing) and a Staffel of III./ KG 157; the former commanded by Major Hans Jeschonnek, who would later become Chief of Luftwaffe Operations Staff in 1938. The Heinkel crews of Oberst Dr Otto Sommer’s III./KG 157, based in Delmenhorst, were the first operational Luftwaffe crews to receive training in flying over sea areas, their He 111B and H bombers being the first to be equipped with extra flotation gear within the wings to provide buoyancy in the event of an emergency ditching. However, while this development may have appeared favourable to the Reichsmarine, in effect it served to highlight to Göring the capability of his Luftwaffe in dealing with naval aviation, relegating a separate naval air arm yet further into the backwater of military priority.

During 1934 the rate of Luftwaffe rearmament had increased under Milch’s effective administrative leadership, in what became known as the ‘Rhineland Programme’, which called for a total of 4,021 aircraft to be manufactured in Germany between the beginning of January 1934 and the end of September the following year. This formidable projected total included eighty-one He 60s and twenty-one Dornier Do 15 long-range reconnaissance aircraft, fourteen He 51W and twelve He 38 fighters, and twenty-one He 59 multipurpose aircraft for naval aviation. Four improved Dornier Do 18 flying boats were also planned to be built. An improved design based on the original Wal, the Do 18 retained the high wing, metal hull and push-pull engines in tandem. The power was boosted by the use of Junkers Jumo 250 engines, and general aerodynamics and handling were improved. However, by the outbreak of war the Do 18 was found to be virtually obsolete. Underpowered and vulnerable to enemy fire, it was still used in some quantity owing to the lack of a suitable long-range reconnaissance replacement aircraft for the Küstenflieger.

Almost predictably, the programme failed to keep pace with plans, not least of all due to engine production lagging behind the manufacture of airframes, though by March 1935 three new units were able to be formed from delivered aircraft: Küstenaufklarüngsstaffel (Coastal Reconnaissance Squadron) 1./126 at List, Küstenaufklarüngsstaffel 2./116 at Nordeney and Küstenjagdstaffel (Coastal Fighter Squadron) 2./136 at Kiel- Holtenau.13 During October a revised production schedule, Lieferplan Nr.1, was enacted, which would produce a total of 462 naval and 200 naval training aircraft.

Finally, in March 1935, Hitler revealed to the world Germany’s rearmament and the existence of an independent Luftwaffe. Ex- Reichsmarine officer Oberstlt. Ulrich Kessler, commander of the Fliegerwaffenschule, Warnemünde, witnessed the immediate prelude to the announcement.

[Kessler] had been travelling with British Air Vice-Marshal Sir John Salmond, who had been visiting Germany as a representative of Imperial Airways to study the German Lufthansa Air Line and particularly training in blind landing (the Lufthansa had been training many English pilots in blind flying) . . . One day Sir John and the British Air Attache, then Col Don, paid an official visit to Göring, with [Kessler] acting as interpreter. Sir John and Göring discussed the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty, with Göring complaining especially about the ban on military aviation. Sir John pointed out that in this respect Germany had been granted equality in theory in December 1932, to which Göring replied with some heat that Germany had not needed that other nations grant her moral equality, that what she had been waiting for fifteen years was real equality. ‘Now.’ he added, ‘he had been building up a little Air Force of his own.’ [Kessler] hesitated to translate this latter statement, but Göring insisted. ‘A little one?’ was Sir John’s reply, to which Göring said, ‘Well, I would call it little.’ Göring thereupon promptly notified Hitler that he had let the cat out of the bag, and public announcement followed the same day.14

Göring was named Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief (Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe), subordinate to the head of the Armed Forces. Those units previously disguised as flying clubs or police formations — the latter generally comprised of SA paramilitaries — were handed over officially to the strength of the Luftwaffe. Beneath the expansive Luftwaffe umbrella were flak units and, eventually, parachute, infantry and even armoured formations.15 The naval aircraft units also passed into this all-pervasive realm, including all naval officers and men who had so far received air force training. (Although exact figures are unknown, it is thought to have been approximately eighty officers, including at least twenty-seven from Crew 33 and thirty-six from Crew 34.) They were released by Raeder for Luftwaffe service as pilots and observers, and included within the Luftwaffe’s personnel, organisation and supply branches in the vain hope that their attachment could engender a greater understanding of naval interests in aerial matters. To that end, Raeder personally wrote to each senior naval flier who was being transferred, urging them to always remember the naval perspective in their future endeavours. Retired and reserve naval officers were also recalled for posting to administrative offices within the Luftwaffe ground staff, and during 1935 forty officers ranging in rank from Leutnant zur See to Konteradmiral were transferred to the Luftwaffe.

Meanwhile, the Reichsmarine was renamed the Kriegsmarine by Hitler and embarked upon its own expansion plan; building vessels allocated to increasing the size of Raeder’s surface fleet and U-boat strength, though the latter initially remained a poor relation to the former. The original plans of Raeder’s drive for a new, balanced fleet included the construction of two aircraft carriers, recorded on 11 November 1935 in the overall construction proposal.16 These would be Germany’s first dedicated aircraft carriers since the initial interest in converting Ausonia at the end of the last war. Building such a ship from the keel up was a hitherto unexplored area of Geramn naval development, and 36-year-old Naval Chief Architect Dr Wilhelm Hadeler was obliged to begin his planning virtually from scratch. He chose as his original models the British Courageous-class carriers and the Japanese Akagi which would later take part in the raid on Pearl Harbor. Two German engineers were part of a delegation that toured HMS Furious during Britain’s ‘Navy Week’ in 1935, photographing her sister-ship Glorious during the same event. Of more use was an official Japanese tour of Akagi granted to a small group of naval architects at Sasebo Navy Yard during the same year, blueprints of both Akagi and Soryu being handed over before the Germans departed.

Hitler authorised the construction plans of the two carriers, given the budgetary and construction designations ‘A’ and ‘B’ and to be included in the fiscal years 1936 and 1938 respectively. The intended commissioning year was to be 1939; ‘A’ was scheduled to be commissioned on 1 April 1939, and ‘B’ on 1 October. A further two carriers were also added as a later product of the ‘Plan Z’ naval rearmament scheme authorised in early 1939, but this never gained traction before the outbreak of war and swiftly altered priorities.

The Deutsche Werke Kiel AG was awarded the contract for carrier ‘A’ on 16 November 1935, though construction was delayed because the shipyard was already working to capacity, with the battleship Gneisenau, the heavy cruiser Blücher, four destroyers and four U-boats filling the slipways that teemed with workers. The carrier’s keel was finally laid on 28 December 1936 in Slipway 1, from which Gneisenau had been launched twenty days previously. Carrier ‘B’ had been awarded to Krupp’s Germania shipyard. The machinery contract was issued on 11 February 1935, and construction of the ship itself following on 16 November. However, construction of this vessel was delayed even further, and the keel was not laid until the second half of 1938, after the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen had been launched. Building of ‘B’ then proceeded at a deliberately slow pace to capitalise on potential experience gained during the building of ‘A’, the hull of which was launched on 8 December 1938.

Meanwhile, with the assumption of Luftwaffe control over naval aviation, Raeder was compelled to request the continued establishment of naval air squadrons, and was promised twenty-five, totalling 300 aircraft, during 1935. The original proposal included three mixed groups of coastal aircraft (each with a squadron of short- and long-range reconnaissance and general-purpose aircraft), two ships’ aircraft groups with two squadrons, three mixed groups of carrier-borne aircraft (each with a squadron of fighter, general-purpose and dive-bomber aircraft), and three coastal fighter squadrons. Apart from the fighter and carrier-borne units, the rest were to consist entirely of He 60 short-range reconnaissance, Do 18 longrange reconnaissance and He 59 multipurpose aircraft. At the right time, the He 60 was scheduled to be replaced as ships’ reconnaissance aircraft by the He 114, and later the Arado Ar 196; the Do 18 by the Ha 138 that was in development (later known as the BV 138) as a long-distance flying boat, and the He 59 by the improved He 115 as a general-purpose aircraft. Although early trials of the Heinkel He 115 V1 had been a spectacular failure, Heinkel chief test pilot Friedrich Ritz stating baldly that ‘The bird was cursed with absolutely terrible flight characteristics’, continued development resulted in a fine aircraft that was popular with naval aviators. The air bases at List, Hörnum, Nordeney, Wilhelmshaven, Kiel, Grossenbrode, Bug auf Rugen, Warnemünde, Swinemünde, Nest and Pillau were all used during the build-up phase; carrier aircraft were based at Bremerhaven and Holtenau.

This plan would enable the Luftwaffe to form Gruppen, each containing constituent parts of a Jagdstaffel (a fighter squadron of approximately twelve aircraft), Fernaufklärungsstaffel (long-range reconnaissance squadron) and a Mehrzweckstaffel (multipurpose squadron), under the control of the Gruppenstab (Group Staff Unit). Three such Gruppen would in turn form a Geschwader (See) (naval combat wing). By October 1936 it was planned to have two autonomous naval Geschwader, though the target production required was never fully attained.

Nonetheless, even this proposed strength was soon deemed inappropriately small for the needs of the Kriegsmarine, particularly in view of potential war against Great Britain and France. Fast aircraft would be required for reconnaissance duties both to the east and west, and Raeder and his staff firmly believed that the Luftwaffe’s thinking remained rooted in continental warfare, and that it was therefore unable, or unwilling, to fulfil naval requirements. As he saw it, a strong independent naval air arm was the only solution, and during April the following year Raeder requested an increase to sixty-two squadrons totalling approximately 800 aircraft, many of which were specified as high-performance types with wheel undercarriages for attacks against naval targets and enemy naval bases.

Pre-war photograph from Seeflieger magazine showing an He 59 in Kiel harbour while a flight of He 60s pass overhead.

Only fast aircraft can be used for long-range reconnaissance in the Channel; flying boats cannot stand up to fighter defence on account of their low speed and lack of manoeuvrability. They are open to enemy attack for about two-thirds of their journey. Requirements are the same both as regards the patrol of the east coast of England and that of the Gulf of Finland (Leningrad).

For offensive operations against naval targets, against English or French bases and mercantile ports, including those on the west coast of England and the Irish coast, bomber formations of Luftwaffe Luflotte 2 are by all accounts to be provided. It is doubtful, however, whether bomber formations of the operational Air Force, which are used for large-scale massed attacks on special concentrations at the front, could be released at any given time for such special tasks. It is imperative that the Navy should be in a position to deal, at least in part, with such tasks.17

Raeder asked for six long-range bomber squadrons to be attached to the naval air service for the purposes of minelaying, with the incumbent specialist training required. In total he wanted:

Twenty-five general-purpose squadrons (He 115)

Nine flying boat squadrons (Do 18)

Three long-range reconnaissance aircraft squadrons (wheeled)

Six long-range bomber squadrons (wheeled)

Seven ship-borne squadrons (small floatplanes)

Twelve carrier squadrons (fighters, dive-bombers, torpedo bombers).

The new request met with Göring’s agreement in principle to realise such a plan by 1942, within the framework of existing prearranged Luftwaffe expansion. The issue of operational control of the naval air arm had yet to be finalised, the Luftwaffe being content to solidify the chain of command ‘later’ in a memorandum despatched to Raeder by Generalmajor Albert Kesselring, Luftwaffe Chief of Staff. In the interim the Luftwaffe established a command specifically for naval operations, Luftwaffenkommando See, and placed it under Kriegsmarine tactical command. Raeder felt this also insufficient, though his assertion that the Kriegsmarine should have a say in developing the aptitude of naval fliers was, in turn, unacceptable to Göring. An impasse had already been reached which would never truly disappear during the years that followed.

Heinkel He 59B ashore on a seaplane base hardstanding for replenishment.

Close co-operation between the three branches of the Wehrmacht had already been formalised in published military doctrine by the end of 1935. One of the most influential officers of Göring’s small staff was Generalleutnant Walther Wever, an outstanding former army staff officer who had been transferred to the Reich Air Ministry on 1 September 1933 as Office Chief, and was soon elevated to Chief of the Air Command Office; in effect a de facto Chief of Luftwaffe General Staff.18 It was he who oversaw the creation of Regulation 16: The Conduct of Aerial War’ (Die Luftkriegführung), which was eventually issued in 1935. Regulation 16 encouraged wide flexibility in the use of Luftwaffe assets, listing strategic bombing, air superiority and the direct support of Army and Navy operations as principles upon which the air forces should be employed.

Air Force/Naval Co-operation.

Should there be no maritime co-operation possible, the air force will be able to use its strongest forces available in air operations.

The primary targets of the air force in this environment are the enemy fleet and air units. This will degrade his ability to execute naval operations.

The air force can also support the navy by carrying out operations against enemy ports as well as against his import and export.

These attacks may not always be carried out in co-ordination with naval operations, but have to be in co-operation with naval objectives.

Only a part of the air force will be used to carry out naval operations, and then secure means of communication have to be established between navy and supporting section of the air force.

The operations of the army, navy and air force have to be co-ordinated in such a manner that maximum overall effectiveness is achieved.

However, an important distinction between Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine co-operation as opposed to that with the Army lay in the fact that at no point did Regulation 16 advocate aerial units being placed directly under Kriegsmarine control. This is in contrast to Army co-operation, in which it was stated that:

Direct co-operation with and direct support of the Army are missions primarily of those units of the Luftwaffe which are allocated to and assigned under Army control for reconnaissance and air-defence purposes. The types of forces in question include reconnaissance, anti-aircraft artillery, aircraft reporting and, if the current situation on the ground requires and the overall situation permits, fighter forces.

On 1 October 1936 the Luftwaffe reorganised its composite units and Luftkreiskommando VI stood at the following strength with newly-created Küstenfliegergruppen (coastal aircraft groups) created by the renaming of Seefliegerstaffeln. Each of the new Gruppen comprised three Staffeln; the first a short-range tactical reconnaissance squadron, the second longrange reconnaissance and the third multipurpose. The vast majority were commanded by former naval officers (denoted by an *):

Befehlshaber im Luftkreis: General der Flieger Konrad Zander* (also Inspekteur der Marineflieger until 1 April 1937)

Chief of Staff: Oberst Hermann Bruch*

Führer der Marineluftstreitkräfte: Oberst Hans-Ferdinand Geisler* (Kiel)

Küstenfliegergruppe 106: Oberstleutnant Ulrich Kessler* (List/Sylt)19

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 1./Kü.Fl.Gr.106: Hptm. Wolfgang Bühring*, Heinkel He 60

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 2./Kü.Fl.Gr.106: Major Axel von Blessingh*, Dornier Do 18 (and depot ship Hans Rolshoven, later transferred to the Seenotdienst)

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 3./Kü.Fl.Gr.106 Major Hans-Arnim Czech*, Heinkel He 59 (Had returned from temporary duty on mission to the Japanese Navy to train as an aircraft carrier pilot aboard the Akagi and to study the Japanese aircraft industry).

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 1./206: Hptm. Hermann Busch*, Heinkel He 60 (Nordeney)

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 2./206: Hptm. Joachim Hahn*, Dornier Do 18 (Kiel-Holtenau relocated to Nordeney, 1 July 1937)

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 3./206: Hptm. Hans Hefele*, Heinkel He 59 (Kiel-Holtenau, relocated to Nordeney, 1 February 1937)

(All units of Küstenfliegergruppe 206 were subordinated to external staffs; no command unit was ever created)

Küstenaufklärungsstaffel 1./306: Major Friedrich Schily, Heinkel He 60 (Nordeney)

(Likewise, raised without a command unit)

Küstenjagdgruppe 136: Major Georg-Hermann Edert* (Jever)

All squadrons equipped with He 51 floatplanes for coastal fighter protection.

Küstenjagdstaffel 1./136: Oblt. Hans Hans Busolt (Kiel-Holtenau) (former Army officer)

Küstenjagdstaffel 2./136: Hptm. Werner Restemeyer (Jever)

Küstenjagdstaffel 3./136: Oblt. Hannes Trübenbach (Kiel-Holtenau, relocated to Sarz 1 November 1936)

Also, the Bordfliegerstaffel 1./BFl.Gr.196 had been created; a catchall squadron from which shipborne aircraft and crews were drawn, the remainder being stationed ashore and taking part in coastal reconnaissance and, later, anti-aircraft missions.

Bordfliegerstaffel 1./BFl.Gr.196: Hptm Heinrich Winner*, Heinkel He 42 and He 60 (Nordeney, relocated to Wilhelmshaven, 1 January 1937)

Logistically, Zander controlled the following supply units:

Luftzeuggruppe VI (See) Kiel (responsible for ships and boats used in support of naval aviation), established 1 April 1934;

Luftzeugamt (See) Travemünde, established 1 October 1936;

Luftpark (See) Holtenau, established 1 October 1934;

Luftpark (See) Nordeney, established 1 October 1934;

Luftpark (See) Swinemünde, established 1 January 1936;

Luftpark (See) Tönning, established 1 April 1936;

Luftpark (See) Ribnitz, established 1 February 1938;

Luftwaffen-Munitionsanstalt Diekhof, established 1 June 1934;

Luftwaffen Munitionsanstalt Hesedorf, established 1 May 1937.

The aircraft with which the naval air force was equipped had all been under development during the years of Versailles restrictions, and plans for the expansion of the Luftwaffe’s maritime component were now well under way, albeit not without hindrance from the Reich Air Ministry. However, even at this early stage the Luftwaffe was about to taste action for the first time, and among those units to be blooded were seaplanes of a hastily assembled squadron. The Aufklärungsstaffel See/88 (AS/88) was attached to the Condor Legion and despatched to wage war in Spain.