Walter Storp, former naval officer in the Reichsmarine before transfer to the Luftwaffe at the rank of Oberleutnant in 1935. Storp’s KG 30 Ju 88 hit HMS Hood in September 1939, but the bomb bounced off. Storp survived the war at the rank of Generalmajor, credited with 435 combat missions.

By this time, the unexpected arrival of Spitfires from Edinburgh’s 603 Sqn scattered the attacking bombers as they gave chase. Storp’s Junkers was hit by machine-gun fire, stopping his port engine and killing rear gunner Ogfr. Kramer. Further strikes disabled the elevators, after which the Junkers crashed into the sea near the coast at Port Seton; the first German aircraft brought down over Britain in the Second World War. Storp was thrown clear by the impact, and he and his two surviving crew, Fw. Hans Georg Heilscher and Hugo Rohnke, were picked up by the fishing boat Dayspring and taken ashore as prisoners. Storp gave the fishing boat’s captain, John Dickson Snr, his gold ring as a token of gratitude for their rescue. Glasgow’s 602 Sqn also arrived, ignoring an unidentified twin-engine aircraft sighted three miles from the scene of the action to intercept three distant aircraft, which turned out to be a trio of naval Skuas on a training flight from Donibristle. Retracing their path, they approached the previously unidentified aircraft, which was now identified as a Junkers. It was commanded by Pohl, who continued to circle while observing the attack. Bullets hit the port wing as Pohl hurriedly sought cloud cover but was outpaced by the pursuing Spitfires. As they attempted to climb away, the Ju 88’s cockpit was struck again by machine-gun fire, killing pilot Fw. Werner Weise and rear gunner seventeen-year-old Gefr. August Schleicher, and wounding the radio operator, nineteen-year-old Uffz. Kurt Seydel. Fuel tanks were soon ruptured and the starboard engine damaged, and Pohl was forced to ditch near a trawler that he fervently hoped would be the Luftwaffe Seenotdienst boat Fl.B213, based in Hörnum and positioned for the purpose of rescuing crews shot down during the raid. However, the trawler was British, and Pohl and his radio operator were pulled aboard, where the latter died of his wounds. Pohl had received wounds to his face and was later transferred to a military hospital in Edinburgh Castle before incarceration in Grizedale Hall. Although Weise’s body was never recovered, Schleicher’s was found, and both he and Seydel were later given military funerals as RAF pipers played Over the Sea to Skye as a lament. Nearly 10,000 people lined Edinburgh’s streets for the funeral procession of the two German airmen, 603 Sqn’s chaplain, the Reverend James Rossie Brown, delivering a moving eulogy and later personally writing to their families in Germany to assure them that their sons had been buried with full military honours. A pair of wreathes were placed on the airmen’s graves at Portobello Cemetery, reading: ‘To two brave airmen from the mother of an airman’, and ‘With the deep sympathy of Scottish mothers’. The dehumanising effect of war had not yet touched this part of Scotland.

The Edinburgh funeral procession of seventeen-year-old Gefr. August Schleicher and nineteen-year-old Uffz. Kurt Seydel killed over the Firth of Forth, 16 October 1939.

As Pohle was being shot down, the fourth wave of Ju 88s attacked HMS Mohawk in an inbound Scandinavian convoy escort, bombs from Lt. Horst von Riesen’s Junkers bursting close alongside and sending lethal flying splinters scything through crewmen. Machine-gun fire from the bombers’ gunners added to the casualties, and the ship’s first lieutenant and thirteen men were killed. The captain, Cder Richard Frank Jolly, was mortally wounded in the stomach but stayed at his post until HMS Mohawk reached its berth in Rosyth, where he suddenly collapsed, dying five hours later.22

In total, HMS Southampton, Edinburgh and Mohawk had all been damaged, and sixteen Royal Navy men were killed and forty-four injured for the loss of two Luftwaffe aircraft, albeit crewed by the Staffel’s senior officers. One of the Junkers of the third wave to attack was chased at low level over the centre of Edinburgh by Spitfires, but escaped, although stray bullets from the engagement hit a building under refurbishment and wounded a painter in the stomach.

The following day four KG 30 Ju 88s on an armed reconnaissance mission (German terminology for ‘shipping harassment’) over Scapa Flow, led by the newly promoted Gruppenkommandeur I./KG,30, Major Fritz Doench, attacked the unseaworthy and partly stripped obsolete battleship HMS Iron Duke, lying in the Flow as guardship only days after the sinking of HMS Royal Oak by Günther Prien’s U47. Two 500kg bombs hit the dilapidated ship, which was severely damaged and forced to beach in Ore Bay with a heavy list to port and one rating killed. A single Junkers piloted by Oblt. Walter Flaemig was brought down in flames by anti-aircraft fire from Rysa Little, crashing at the mouth of Pegal Burn on the Isle of Hoy. Only wireless operator Uffz. Fritz Ambrosius survived. He released the upper escape hatch and was dragged away by the slipstream, still clutching the release handle. Although he was able to open his parachute as the aircraft plunged to the rocks below, he sustained serious injuries because his parachute had caught fire and he landed heavily. He spent a month in hospital after his capture. A second wave of KG 26 Heinkels also attacked the beached ship as workmen of the salvage firm Metal Industries Ltd were engaged in pumping out the vessel and patching the hull, but the bomb run was inaccurate and they failed to hit anywhere near the target.

While the losses suffered by X.Fliegerkorps were considered relatively acceptable, there was growing Luftwaffe concern over the comparatively heavy casualty rate suffered by squadrons operating the Do 18, at that time the only available long-range reconnaissance aircraft. Ten had been lost since the beginning of the war, and construction of a more robust replacement aircraft was once again prioritised, the Dornier being considered extremely vulnerable to enemy air attack. To underline the point, on 17 October 8L+DK of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 had been shot down by Gloster Gladiators of 607 Sqn. Tasked with shadowing enemy shipping following an early-morning search mission for a missing Ju 88 of I./KG 30, Oblt.z.S. Siegfried Saloga reported a ‘light cruiser’ some 125nm east of Sunderland, which they later misidentified as the Polish destroyer Grom, whereas it was actually HMS Juno. A second Dornier was ordered to join Saloga, and at 1240hrs three Gladiators of 607 Sqn were sent off from Acklington to see off both Do 18s. At approximately 1330hrs they engaged Saloga’s aircraft. The flying boat was damaged, and retired quickly towards the east, eventually having to ditch 35nm east of Berwick less than a quarter of an hour later, stalling as it flared for alighting and crashing into the sea. Flight mechanic Uffz. Kurt Seydel was killed, while Saloga, pilot Uffz. Paul Grabbert and radio operator Oberfunkmaat Hillmar Grimm abandoned the aircraft in their liferaft, which proved to have been pierced by gunfire. The swimming Germans were later pulled from the sea by the crew of HMS Juno.

In the meantime, Saloga’s earlier contact report triggered the despatch of six He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 from List at 0957hrs on an armed reconnaissance of the area Flamborough Head-Aberdeen, along with an additional three equipped with bombs. At 1020hrs they were followed by thirteen He 111s of KG 26, which took off from Westerland and headed for the area under the scrutiny of the He 115s. At 1507hrs two He 115s of the Bombenkette found and attacked HMS Juno six sea miles north of Berwick, dropping four SC250 bombs without result. The Heinkel floatplanes were later attacked by the Gladiators of 607 Sqn, but the combat was inconclusive. The KG 26 bombers failed to located Juno and returned to their airfield.

Increased numbers of He 115s were arriving at Küstenflieger squadrons, though they were still incapable of carrying torpedoes into action owing to the F5’s deficiencies. Furthermore, their potential vulnerability to determined enemy defence was soon made glaringly apparent during a badly fumbled operation mounted in co-operation with X.Fliegerkorps on 21 October. Convoy FN24 from Methil to Orfordness was reported steaming north of Flamborough Head, and MGK West requested and was immediately granted permission to co-ordinate an air attack. Ten He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 were armed with bombs and prepared for the raid, and the initial attack wave was increased to include three Ju 88s of 1./KG 30. As the two aircraft types had vastly different capabilities, takeoffs were staggered to allow the Heinkels to arrive on target first, followed shortly by the faster Junkers bombers. However, the plan misfired badly, as the Ju 88s outpaced the slower floatplanes and arrived well in advance, delivering their bombing attacks and retreating at equally high speed. By the time the Küstenflieger were within sight of the target, at 1545hrs, RAF Spitfires of 72 Sqn and eleven Hurricanes of 46 Sqn were on protective patrol, alerted by the previous attack.

The Heinkels flew into heavy defensive fire, and their loose formation was soon broken up by the British fighters, each of the floatplanes attempting emergency manoeuvres against the more agile fighters. Within minutes four had been shot down. Oberleutnant zur See Heinz Schlicht and his two crewmates, Lt. Fritz Meyer and Uffz. Bernhard Wessels, were brought down into the sea, their aircraft crashing five miles off Spurn Head, Yorkshire and killing all on board. The crew’s bodies were carried by the tide until they were washed ashore at Mundesley and Happisburgh, Norfolk, and they were buried on 2 November. A second Heinkel, commanded by Oblt.z.S. Albert Peinemann, crashed while attempting to ditch after being severely damaged by the attacking fighters. Pilot Uffz. Günther Pahnke and Peinemann were both slightly injured, but radio operator Uffz. Hermann Einhaus was unscathed, and all were rescued by a British merchant ship. The following day their abandoned Heinkel was examined by the crew of a Do 18, who landed alongside before sinking it with gunfire. A third crew, led by Oblt.z.S. Günther Reymann, was also taken prisoner after an emergency alighting by pilot Fw. Rolf Findeisen, who was badly injured and admitted to hospital after being put ashore on British soil.

The fourth Heinkel brought down was piloted by Uffz. Helmuth Becker, who was killed in combat with Spitfire K9959, piloted by Australian Flt Lit Desmond Sheen of 72 Sqn.

Just nineteen days after his 22nd birthday . . . Des later described that battle as ‘Really good fun; as exciting a five minutes as anything you could wish for’.

‘A’ Flight was scrambled at 2.15pm, and ‘B’ Flight’s Blue section was put on readiness. Green section, led by Des in Spitfire K9959, was scrambled at 2.30pm. He and Flying Officer Thomas ‘Jimmy’ Elsdon were ordered to proceed to Spurn Head, and soon sighted a loose formation of 12-14 aircraft, which they identified as Heinkel He 115 three-seater floatplanes.

Des and Elsdon intercepted the formation about 15 miles south-east of Spurn Head. As the Spitfires neared, the three enemy subsections ‘split up and employed individual evasive tactics of steep turns, diving, climbing and throttling back’.

Des ‘fired all I had at one of them’, attacking from ‘dead astern’, at about a hundred yards’ distance. Then: ‘as I closed on my He 115, its rear gunner attempted to put me off my aim by blazing away with his weapon, but I soon silenced him. The next burst may have killed the pilot, for the Heinkel started to fly very erratically, and with this I turned away to look for another target.’23

The Heinkel broke away and later ditched near the Danish ship Dagmar Clausen, Oblt.z.S. Gottfried Lenz having been wounded by the Spitfire’s bullets, and Uffz. Peter Großgart was rescued by the neutral steamer and returned to Germany two days later.

The disaster of 21 October was referred to by Raeder in conference with Hitler two days later, as Raeder attempted once more to urge greater naval control of such aerial operations or, at the very least, enhanced cooperation between Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe forces.

The attack by He 115s in the coastal waters off southern England resulted in the loss of four aircraft; this area therefore appears unsuitable for attacks. The C-in-C Navy declares that conclusions have already been drawn from this experience, namely that the anti-aircraft defences are apparently very strong along the southern part of the coast of England. The C-in-C Navy asks that no measures be taken as rumoured — for instance, that combined operations over the sea are being considered — for it is absolutely necessary to train and operate naval aircraft in closest co-operation with naval forces. The Führer declares that there is no question of such measures.24

However, the entire event played further into the hands of the Luftwaffe elements that wanted to wrest control of maritime operations from the Kriegsmarine. On 15 November Göring ordered the reduction of the Küstenflieger to just nine long-range reconnaissance and nine multipurpose Staffeln. He strongly requested that Raeder withhold the slow seaplanes from enemy coastal operations, noting that the Luftwaffe was supposed to be the authority of activity over open sea if no fleet operations were taking place.

The grievous losses did little for the moral of Küstenfliegergruppe 406, the Kommodore Obstlt. Karl Stockmann complaining bitterly about the effectiveness of his seaplanes and requesting, unsuccessfully, that at least one Staffel be converted to Fw 200 bombers. Instead, his staff unit was diverted to responsibility for the formation of a new long-distance reconnaissance unit, the Transozeanstaffel under the command of Major Friedrich von Buddenbrock, previously of the F.d.Luft Ost staff. During August 1939 Hermann Göring, as Minister for Air, had ordered that all Lufthansa seaplanes be placed at the disposal of Luftwaffe command. Although he recommended the continuation of transatlantic passenger flights until the eve of war, the few available transocean Lufthansa aircraft operating in conjunction with catapult ships in the Atlantic were ordered back to Germany via Spain shortly after hostilities began, the catapult ships being directed to dock in neutral Las Palmas. By 15 September 1939 the Luftwaffe had authorised the formation of the Transozeanstaffel, and the first pair of former Lufthansa Do 26 flying boats, Seeadler and Seefalke, alighted at Friedrichshafen for transfer onwards to Travemünde in September. Four other Do 26s either in trials or under construction were soon added to the specialised Staffel, which was completed by the addition of three large Lufthansa Blohm & Voss Ha 139 floatplanes named Nordneer, Nordwind and Nordstern, and two smaller Dornier Do 24s. The catapult ship Friesenland was used for the operation of the Ha 139s, docked in Travemünde and made ready for exercises in January 1940. While the Staffel was still in its gestation, its personnel were subject to posting to units already in combat, aircraft commander/observer Hptm. Rücker being ordered by F.d.Luft to transfer to KG 26 on 10 January, leaving only a single observer officer on strength until the arrival of Kriegsmarine Oblt.z.S. Heinz Witt, though Witt was qualified as an observer and not as an aircraft commander. Buddenbrock subsequently complained to Generalmajor Hans Ritter as Gen.d.Lw.Ob.d.M., asking how the Transozeanstaffel was to reach operational readiness with such a shortage of observer commanders.

In reality, none of the Transozeanstaffel aircraft would be combat ready for several months, as they were being adapted from civilian to military use with the assistance of engineers from Dornier and Blohm & Voss. This entailed the fitting of machine guns, bomb-carrying gear and accompanying ballast to the erstwhile civilian aircraft, which was not without its difficulties. Not until February 1940 did MGK West request their immediate despatch to the covert German naval base inside Soviet Russia, Basis Nord, for the purpose of North Atlantic reconnaissance. The small Kriegsmarine outpost had been established at the small fishing port of Zapadnaya Litza, 120km west of Murmansk in the Motovsky Gulf. However, the aircraft were deemed unready, as trials were ongoing to establish the operational radii available to the various aircraft using the less fuel-economical water take-offs necessitated by the rather primitive facilities at the Soviet port. The results were disappointing. Naval command estimated that the ‘range for Ha 139 aeroplanes is 2,500km, for Do 26 aeroplanes 3,000km, i.e. just barely enough for the flight from North Base to Germany’. The MGK request was subsequently refused, and Buddenbrock’s Staffel would not see action until April 1940, during the invasion of Norway.

Meanwhile, in October 1939, the dislocation of naval air units caused by transfer of individual Staffeln from east to west as Poland approached collapse prompted a wholesale reorganisation of the Küstenfliegergruppen, most individual Staffeln being renumbered while Küstenfliegergruppe 306 was disbanded and two entirely new Gruppen formed. While Küstenfliegergruppe 106 remained unchanged, the following exhaustive reorganisation took place:

Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 was disbanded.

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became the core of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406, with some men and equipment distributed elsewhere as reinforcements.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 was reorganised:

Stab became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 306;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by former 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 was reorganised:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 806, replaced by former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806, replaced by former 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406, replaced by new Staffel, 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 was disbanded, replaced by renumbered 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, consisting solely of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, was disbanded when 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 was redesignated 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906. However, the decision was taken on 1 November to re-form the Küstenfliegergruppe with three Staffeln raised from scratch: 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, plus Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 606. However, although this unit was originally destined for purely maritime operations and equipped with seaplanes, a fresh caveat was placed upon Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, requiring that it be re-equipped with Dornier Do 17 bombers with land undercarriages. Under the command of Obstlt. Hermann Edert, the new squadrons would be considered a land-based Kampfgruppe; a standard bomber formation. A single bomber of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, 7T+CH, was kept in readiness at all times for maritime operations, the remainder eventually alternating between land and sea missions, though the latter became less prevalent with each passing week once the Küstenfliegergruppe was operational.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 was disbanded:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 906;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906. Not until 1 January 1940 did Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 begin to re-form, 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 being created in Kiel-Holtenau, equipped with He 59s rather than their previous He 60s. In July 1940 Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 was formed in occupied Stavanger, and 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 following three years later in Tromsø.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 was created in Dievenow:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr.806 from former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr.506;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 from former 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 from former 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 built from scratch.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 was created in Kamp:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Kamp) from former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 60);

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Nest) from former 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 60/ He 114);

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Pillau) from former 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 (Do 18); 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Norderney) from former 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 59).

There was no respite from operations while this organisational upheaval was taking place, and the aircraft continued to fly. On 22 October six German destroyers carried out a sortie against merchant shipping in the Skagerrak as part of a general Kriegsmarine initiative to consolidate control of the North Sea approaches to the Baltic. Multiple reconnaissance flights mounted by the naval air arm revealed numerous steam trawlers in the Dogger Bank and Hoofden areas, thought likely to be British or working in conjunction with Allied intelligence-gathering. Channel lights continued to burn brightly along the British coast, as they did in Dutch waters, in addition to the remains of one of the unfortunate He 115s shot down during the botched attack on Convoy FN24 and Seydel’s Do 18 drifting twenty miles east of Hartlepool. The destroyers seized two neutrals west of Lindesnes, one Swede and one Finn, carrying contraband to England, while fourteen other neutrals were stopped and released.

However, the reconnaissance demands were stretching the naval air arm to exhaustion. At the end of October MGK West flatly informed SKL that there were insufficient aircraft available to cover the tasks allocated effectively. Each large-scale operation that was mounted resulted in exhaustion of the available crews, rendering them ineffective on the following days. Only the Do 18 was suitable for long-range missions, the numbers having been reduced by the ten lost during the previous month and the receipt of only three replacement aircraft. The He 115 was increasingly coming into use as a medium-range multipurpose aircraft, but its limitations too had been starkly illustrated by the disastrous raid on Convoy FN24. Admiral Saalwachter, in conjunction with F.d.Luft West, estimated that a total of 378 naval aircraft would be required to provide the essential operational number of 126 in readiness at any given time. The total available to them at the end of October was listed at eighty-five machines.

The resultant staff conference between the two services served only to see the Reich Air Ministry recommend that three of the twelve multipurpose squadrons either at readiness or forming be transferred to Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps. Raeder, of course, rejected the proposal, reminding Göring in a letter of the original agreement of naval air strength reached during the previous spring. Nonetheless, the letter did not better his cause, and naval air strength continued to dwindle through attritional loss and gradual diversion towards standard Luftwaffe use.

Consequently, during the first week of November Raeder’s staff issued a fresh directive to MGK Ost and West (with a copy sent to Generalmajor Ritter), in which they outlined the employment of naval air formations during what they termed the ‘struggle against Britain’. Bearing in mind the aircraft types available, they ordered concentration on open sea reconnaissance, confining combat missions to anti-submarine actions and opportunistic attacks on small enemy surface vessels. Torpedoes were only to be used in favourable weather conditions that offered ‘good tactical possibilities’. Minelaying, too, was only to be undertaken in optimal weather conditions, and only then in close co-operation with X.Fliegerkorps.

The German Luftmine (LM) mine series, developed by the Kriegsmarine, eventually consisted of five different series of sea mines, designated LMA, LMB, LMC, LMD and LMF. All were influence mines designed primarily for dropping from aircraft by means of large parachutes. Both the LMA and LMB were ground mines, while the remaining three were moored. The LMA mine was developed between 1929 and 1934, though due to its relatively low charge weight (300kg of hexanite) it was not extensively used and manufacture discontinued early in the war. The LMB mine was developed during the same period and was of similar construction, carrying 705kg of hexanite explosive and therefore of slightly larger dimensions.

The LMC mine was an experimental model, development of which started in 1933. A moored mine designed to be laid from aircraft such as the He 59, development was discontinued when it became apparent that the He 59 would not remain in combat operations. The work thus far completed on the LMC was instead transferred to the LMD, which could be laid by any mulitpurpose aircraft. The LMD was intended to have the same general dimensions as the LMB mine, but, once again, development was stopped in 1937 and transferred to the LMF, a cylindrical moored influence mine with a warhead carrying 290kg of hexanite, designed for aircraft use but first deployed by S-boats in 1943. During 1940 the Luftwaffe also began developing aerial mines separate from the Kriegsmarine, ending in the creation of the Bombenmine (BM) series.

The minelaying instructions to X.Fliegerkorps marked one of the few occasions on which there had been unity in Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe thinking. At the outbreak of war the SKL had wanted to delay the instigation of aerial minelaying until sufficient aircraft and stocks of LMA and LMB mines were available to mount a concerted minelaying offensive that would cause major problems for British countermeasures. However, a review of mine production and availability led naval planners to opt instead for the immediate commencement of aerial minelaying to augment the thick barrages already sown off the English coast in dangerous inshore missions carried out by destroyers, S-boats and U-boats. Despite opposition from the Luftwaffe, who favoured accumulating a larger stockpile before starting minelaying, and thus striking one major blow rather than many smaller ones, the Küstenflieger launched their inaugural minelaying missions in November. Instructions were issued that included the use of He 59 aircraft to lay LMA mines between the moles of British harbour entrances.

On 20 November He 59s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 laid mines in the Thames Estuary and near Harwich as the start of operations codenamed Rühe (Silence). Of the nine aircraft despatched, five turned back because of navigational difficulties, as each mine needing to be dropped precisely where planned. During the nights of 22 and 23 November there was further minelaying, by aircraft of Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and 906, which dropped them in the Thames River and estuary as well as at Harwich, in the Humber, in the Downs and, in an effort to disrupt supply of the British Expeditionary Force in France, in the approaches to Dunkirk Harbour. Between 20 November and 7 December five missions were flown on which forty-six LMA and twenty-two LMB mines were dropped.

The results were almost immediate. At approximately 2100hrs on 21 November HMS Gipsy was sunk while departing Harwich for a North Sea patrol, in company with four other destroyers. A single seaplane had been sighted flying low offshore, but as there was a Short Sunderland seaplane base nearby, no guns were fired. The intruder was finally identified as an He 59 by searchlights from Landguard Fort, but they were ordered to be doused to allow the quick exit of the five destroyers from harbour. Fighters were belatedly scrambled from nearby RAF Martlesham Heath, but failed to intercept the minelayer, which had dropped two LMAs, and at 2123hrs HMS Gipsy detonated one of them, breaking in half and sinking in shallow water, killing twenty-eight men. The destroyer’s captain, Lt-Cdr Nigel J. Crossley, died of severe wounds six days later. The steamer SS Hookwood was also sunk in the Thames Estuary, near the Tongue light vessel, while travelling from Blyth to Dover on 23 November. Two crewmen were killed.

In fact the magnetic mine offensive had begun to fail as early as 22 November, when an He 115 of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 was fired upon by an anti-aircraft machine-gun team near Shoeburyness. Evidently startled by the sudden barrage, the Heinkel’s crew dropped their LMA mine and hastily departed. The parachute mine landed in the mudflats of the estuary, its descent being observed and the mine pinpointed. The Royal Navy summoned specialists Lt Cdrs John Ouvry and Roger Lewis from HMS Vernon, and alongside British Army explosive experts they waded out to the exposed mine that night, and by the following day had defused it. The weapon’s secrets were subsequently revealed after close examination ashore, and countermeasures soon put into place which would nullify the advantage given by the magnetic mine. Nonetheless, the fact that British engineers were feverishly working on an answer to the magnetic mine only spurred Raeder to demand yet more vehemently that the Luftwaffe also begin minelaying in earnest before the opportunity passed.

On the night of 5 December several aircraft were lost on minelaying missions. By this stage He 115s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 had also joined the operations, and aircraft S4+BL crashed on take-off from Nordeney after the flaps were retracted at insufficient altitude, the aircraft flipping over, destroying its LMA payload and killing the radio operator and observer. Only the pilot, Uffz. Rose, was rescued. A second He 115, S4 +EL, was also lost from the Staffel while flying across the Wash to Sheringham, when it collided with the Chain Home radio location mast at West Beckham. The stricken Heinkel narrowly missed the Sheringham gasholder and finally crashed on to the beach a short distance from Sheringham lifeboat station at 0315hrs, killing all three crewmen. Two more He 59s were completely written off during that night’s operations. The port engine of M2+VL of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 caught fire shortly after take-off from Borkum and the aircraft crashed, losing its LMB mine at sea, killing three of the crew and leaving gunner Uffz. Wolf badly injured, and M2+OL of the same Staffel crashed on Borkum’s North Beach and was later found in 4m of water with all four crewmen dead.

A third He 59 made an emergency landing near Schiermonnikoog and was later towed by Vorpostenboote V801 and V805 back to Borkum, and another of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 was damaged by a strongly running swell after making an emergency landing near Ameland. The aircraft was recovered, but suffered further damage to the starboard float during retrieval by the Seenotschiff Hans Rolshoven. Preliminary Kriegsmarine investigations established that, other than the collision over Great Britain, the remaining losses and damage were predominantly caused by the inclement weather conditions and the resultant icing, and perhaps also by the overloading of the aircraft necessitated by the mission task. Ice within the seaplane bases had become a major issue, and by 17 December the increasingly severe winter caused all further operations to be cancelled.

Nine days previously, a conference between the Naval Staff and F.d.Luft West, Generalmajor Coeler, had taken place to review progress of the aerial minelaying. Coeler stated that the He 59 had proved itself ‘exceptionally suitable’ for such operations, able to carry two LMA or one LMB mine as far as the Downs, River Thames, Dunkirk, Calais and the Humber. The smaller He 115 had also performed well, being capable of carrying a single LMA or LMB mine as far as Southampton. However, in his view the minelaying operations had placed a disproportionately heavy strain on both personnel and material. The necessity of laying mines accurately, the long approach flights, exacting navigation requirements, bad weather conditions, seven to eight hours blind flying at night and frequent heavy overloading of aircraft all demanded the highest crew efficiency.

The regrettable losses which have occurred lately are mostly due to heavy overloading of the aeroplanes, the difficulties encountered in night takeoffs and to weather conditions (icing). British anti-aircraft defence at night has so far only been slight. F.d.Luft West believes that use of fighters over the Thames area would be of little use. Balloon barrages, on the other hand, which the British are apparently planning to put up, would be quite a hindrance.25

Since accurate navigation was essential for successful minelaying operations, Coeler planned to begin training specialist navigators for the various target areas. In turn, the Naval Staff encouraged Coeler to use ‘all available means’ to lay mines in English waters as quickly as possible, since it was to be expected that British anti-aircraft and antimine defence would only grow stronger. A projected output of 120 newly produced aerial mines was expected for December, although portions of this number were to be held in reserve for Luftwaffe operations in the Firth of Forth and the Clyde, which the Kriegsmarine hoped would take place towards the end of December. For his part, Göring had also pledged to place the training of crews of the operational air force who had been chosen for minelaying operations under Coeler’s direct control.

Ironically, it was Coeler’s determined drive to undertake aerial minelaying that further reduced the standing of the Seeluftstreitkräfte in the eyes of the operational Luftwaffe. With minelaying seaplanes grounded by bad weather, only land-based aircraft were capable of continuing the fight. Subsequently, in January 1940, Göring ordered Coeler to ‘take all necessary steps’ to develop aerial minelaying by the operational Luftwaffe. The Luftwaffe had long harboured misgivings about naval air units conducting minelaying, seeing it as their sole prerogative. Correspondingly, alongside the production of LMA and LMB mines, aircraft specifically adapted for minelaying were also to be built: the first Gruppe of He 111H-4s was to be operational by March, followed shortly thereafter by a second, and there were future plans for the use of Do 217s, Ju 88s, Fw 200s and He 177s.

On 17 January, following renewed and protracted negotiations with the Luftwaffe, General Staff SKL recorded a lengthy War Diary entry entitled ‘Promotion and further development of aerial mining’.

In this special province the F.d.Luft West is placed directly under the Commander-in-Chief, Luftwaffe, to make suggestions with regard to the further development of the apparatus as well as the training of the specialised personnel, and in so doing work in direct conjunction with the offices concerned belonging to the Luftwaffe General Staff. Within the scope of this special assignment, F.d.Luft West has under his command;

1, 7. Staffel, KG 26

2. one Staffel of I. Gruppe, KG 30

3 (later, after formation) 1. Staffel, KG 40.

(At present as experimental and training formations, at the same time to clear up undecided questions with regard to aerial mine warfare.)

A course for aerial minelaying personnel is being arranged at the Luftwaffe Ordnance School (Naval Air) at Dievenow. Three minelaying bomber wings are to be formed later. The Naval Staff welcomes the concentration of training of the aerial minelaying units under F.d.Luft West, whose main tasks — maritime reconnaissance, occasional bombing of naval targets, aerial mine warfare against short-range targets, and operations against merchant shipping — must remain unaffected by the assumption of the new duty and be ensured by suitable arrangements.

The Air Force General attached to Commander in Chief, Navy, considers that no weakening of the naval air formations in favour of the aerial minelaying formations is to be expected. Effects on personnel are at present slight, so that no detrimental effects of any consequence to the personnel situation are to be feared.

Marinegruppenkommando West, too, welcomes the fact that F.d.Luft West has been entrusted with the formation and training of the minelaying squadrons because of his experience, and considers this command the best guarantee that these formations will operate in close conjunction with MGK West and will participate in other naval operations. Three commands will have to co-operate in the future conduct of air operations against Great Britain:

F.d.Luft West: maritime reconnaissance and occasional bombing of naval targets, attacks on merchant shipping, aerial mine warfare against shortrange targets;

X. Fliegerkorps: bombing of naval forces at sea and in port, also harbour installations, attacks on merchant shipping;

Minelaying Air Corps: Aerial mine warfare along the entire coast of Great Britain and in her harbours.

Marinegruppenkommando West in so doing draws special attention to the fact that mine warfare by air and surface forces is the same, and that minelaying operations by naval forces must be kept up continuously and carefully synchronised. They consider the appointment of a General, Luftwaffe, to MGK West as the representative of the Commander-in- Chief, Luftwaffe, a serviceable solution to the question of close cooperation; he will direct the operations of the X.Fliegerkorps and Aerial Minelaying Corps on behalf of the Commander-in-Chief, Luftwaffe after adjusting them to the requirements of naval warfare by issuing operational instructions.

Reorganisation of the Staff of the Commander, Naval Air, has already commenced, with a view to such an organisation. The Commander, Naval Air’s former Chief of Staff, Oberst. [Hans-Arnim] Czech, takes over the minelaying formations, Oberstleutnant [Hans] Geisse will take over the duties of the latter. The Naval Staff considers that it is quite a feasible proposition to carry out the organisation as suggested by MGK West. With regard to operations by aerial minelaying formations, MGK West takes the view — in fundamental agreement with Naval Staff — that mine warfare carried out by air forces off the more distant coasts of England, especially on the west and south-west coasts, should not be commenced until it can be done suddenly, simultaneously and on a large scale, since by this means, the greatest — and in conjunction with the other means of naval warfare perhaps even decisive — effect, can be attained.

In the Group’s opinion, aerial minelaying operations should be limited to the area formerly considered, perhaps extended to the east coast from Dover to Newcastle, until the aeroplanes and aerial mines necessary for the large-scale operation are ready.

It is not yet possible to give a final verdict on the question of whether it was correct to use the aerial mine for the first time as early as November 1939, i.e. at a moment before a sufficiently large number of mines and mine-carrying aeroplanes were available. The fact remains that the aerial mine was used on the south-east coast of England and that its existence thereby became known to the enemy. Patrol flights and defensive patrols, attacks on our airfields, preparation of fighter formations, and erection of numerous balloon barrages on the east coast clearly show that the enemy is conscious of the danger threatening him and has resolved on large-scale countermeasures.

Naval Staff, in agreement with MGK West, considers that, since the dropping of mines from aeroplanes on the east coast has been begun and detected by the enemy, we should now continue this with all the means at our disposal, following up our former objective in the conduct of offensive mine warfare in the North Sea, namely that of making the east coast of England and its ports impassable until any merchant traffic is completely suspended.

Conditions on the west coast of England are different. Although the enemy must also be expecting the dropping of mines from aeroplanes in this area, he will probably — in the endeavour to protect the east coast ports which are particularly endangered and at the same time to protect the interior from air raids — first build up his main line of defence on the east coast with fighters, searchlights, anti-aircraft batteries and balloon barrages. He will not set to work on the effective defence of the west coast until the east has been protected, possibly not even until the western ports are actually threatened with attacks by aerial mines.

Under these circumstances it seems best to leave the aerial mining of the west coast and its important ports and bays until a moment when the stock of mines and the number of suitable mine-carrying aeroplanes will enable the execution of a large-scale minelaying offensive or continuous minelaying operations on the enemy west coast.

By the beginning of February the Luftwaffe’s minelaying specialty unit had been expanded, and Coeler was ordered to create 9.Fliegerdivision, Oberst Czech being appointed his Chief of Staff and Operations Officer. Operationally subordinated to the Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe (Ob.d.L.), and administratively to Luftflotte 2, the new unit was charged with responsibility for all future aerial minelaying, and comprised all of KG 4, Gruppe III./KG 26, Staffel 7./KG 26, I./KG 30 and Gruppe I./KG 40. Before long, 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 was requested to be transferred to Coeler’s new command. Raeder refused, citing operational necessity, but in the end only managed to retain temporary control of Küstenfliegergruppe 106.

Meanwhile, the onset of winter and a steady drain of casualties forced Coeler to suspend minelaying activities by the Küstenflieger, and the last mission of 1939 was completed on 17 December. During the following weeks Göring used his privileged position within Hitler’s inner circle to persuade his Führer to appoint the operational Luftwaffe as the sole aerial minelaying agency. Despite Raeder informing Hitler of the Kriegsmarine’s viewpoint on the matter, and imminent minelaying plans on 23 February — issuing orders to MGK West that day to resume minelaying by the formations with Küstenflieger units ‘as it sees fit’ on the assumption of the Führer’s agreement — Hitler ordered all naval aircraft minelaying to cease in a memorandum to SKL just three days later, the task henceforth being removed from the Kriegsmarine’s sphere of activity. Göring’s machinations had borne fruit, although Hitler was once more swayed to change his mind by Raeder in conference during early March, following British press announcements that they had developed a successful countermeasure to the magnetic mine. With the support of Jodl as OKW Chief of Staff, Raeder pointed out that mine production was steadily increasing, allowing immediate commencement of a fresh aerial minelaying offensive. He was adamant that swift action was necessary before such countermeasures could be widely introduced.

Gruppenkommandeur I/KG 30, Major Fritz Doench (right) and two of his pilots photographed in March 1940.

Naval enquiries to the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff showed that, as of 15 March, ten He 111H-4 aircraft were ready for minelaying use, this number expected to increase to twenty-five within ten days and thirtyone by the beginning of April, thus equipping an entire Gruppe. A total of fourteen Ju 88s of the ‘Storp’ Staffel (1./KG 30) would be brought up to Gruppe strength during the first half of April, rendering two complete Gruppen in readiness as mine-carriers. By 1 May the 9.Fliegerdivision would have three mine-carrier groups (two groups of He 111H-4 and one group of Ju 88s). In the meantime, three Staffeln were available for immediate mining operations: Hptm. Gerd Stein’s He 111-equipped 7./ KG 26 (Stein was the former commander of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906), Oblt. Walter Storp’s Ju 88s of 8./KG 4 (Storp having transferred from KG 30 and begun training his Staffel for minelaying at the beginning of March), and the He 115s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506. Despite disagreements between OKM and the Reich Air Ministry regarding the efficacy of the magnetic mines themselves, by mid-March there was a stock of 268 LMA and 286 LMB mines, each total expected to increase by a further 350 by the end of April.

Generalmajor Joachim Coeler, F.d.Luft West and commander of 9.Fliegerdivision.

Between 2 April and the German attack on the Low Countries and France on 10 May 1940, six minelaying missions were mounted off south-eastern England and the French Channel ports in conjunction with (and under the control of) Coeler’s 9.Fliegerdivision. In total, 188 mines were laid, though they accounted for a meagre seven ships sunk, totalling 14,564 tons. Ultimately, Felmy’s original vision of a concerted lethal campaign using huge numbers of mines had been undermined by Raeder’s determination to use available stocks as quickly as possible and, while the Küstenflieger had been originally tasked with continuing minelaying in advance of the ground assault in the west, on 12 March the task was once again made the sole domain of Coeler’s forces by order of Göring himself.

Away from the problems of jurisdiction over aerial minelaying, in conference with F.d.Luft West, SKL had also pressed for the commencement of aerial torpedo missions to provide operational experience for crews, particularly during bright, clear nights. Coeler requested that the relevant instructions be issued, and on 9 November 1939 SKL delivered a directive that all naval air force units be permitted full use of weapons against darkened ships sighted west of longtitude 3°E, proposing night patrols by torpedo-carrying aircraft on particularly bright nights. The aircraft of X. Fliegerkorps, on the other hand, were only permitted (from January 1940) to attack darkened vessels within 30 miles of the British coast, owing to what the Kriegsmarine perceived as their inferior maritime navigational training and potential confusion of targets.

Despite the loosening of Küstenflieger constraints on torpedo use, there were few successes with this temperamental weapon, the first being on 18 December, when an He 59 of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 torpedoed and sank the 185-ton steam trawler Active off Rattray Head. The vessel’s cook, George Watt, was killed in the sinking, which marked the first successful use of an aerial torpedo in the Second World War. Twice during early November He 59s had scrambled to intercept enemy destroyers; the first time failing to make contact, and on the second launching a single torpedo which completely missed its target. During the morning attack, approximately 70 miles east of Lowestoft, the He 59 released a torpedo at the Polish destroyer Blyskawika from a range of 1,000 yards off its port bow. The torpedo track was visible to lookouts, and was avoided by course alteration as anti-aircraft guns opened fire, driving the slow-moving seaplanes away. Following this failure and the obvious shortcomings of the F5 weapon, Hitler ordered production stopped as of 28 November, until improvements could be made. A stock of seventy-six F5 torpedoes remained, while modifications were tested to improve performance and also allow their use by the faster He 115s.

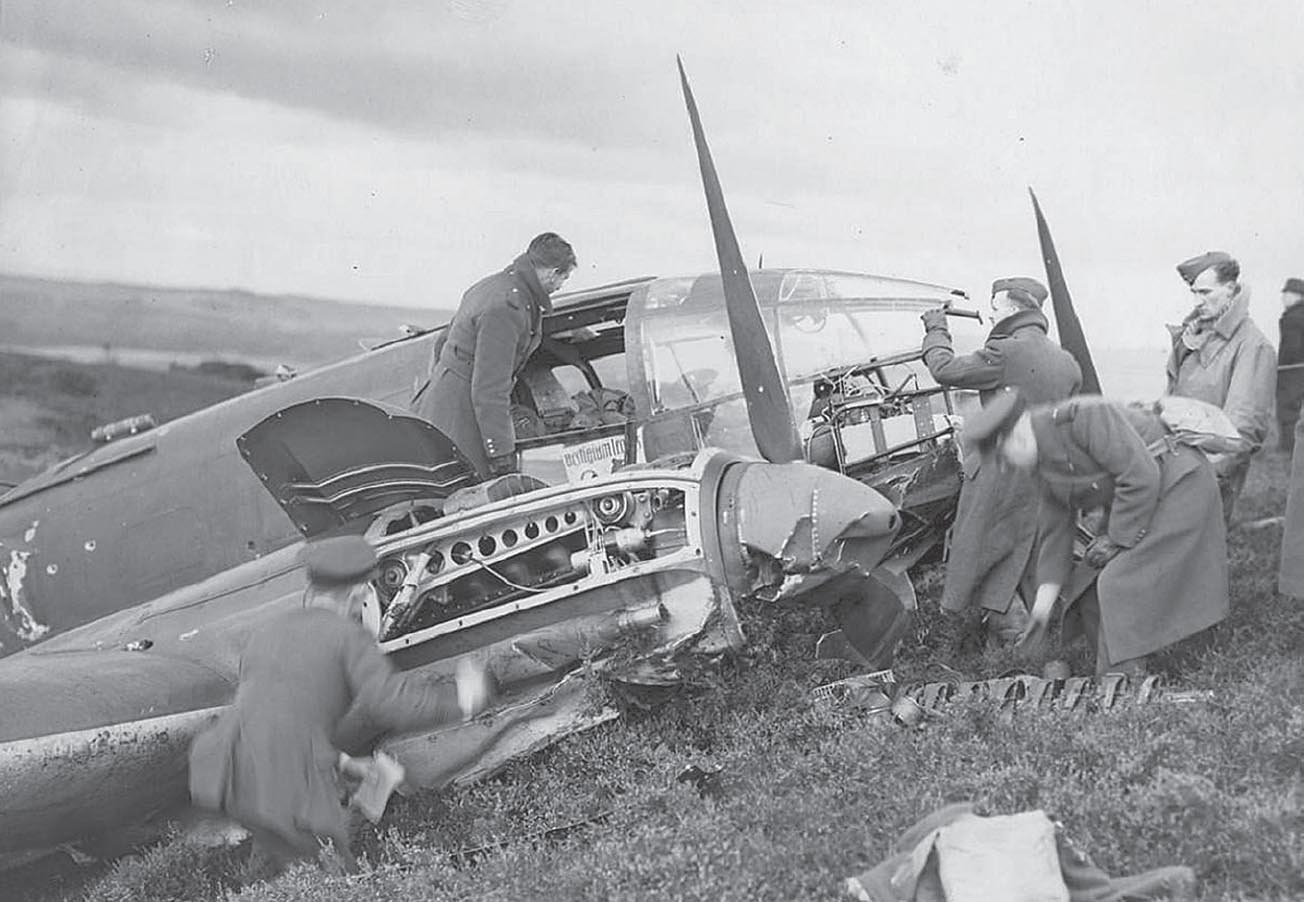

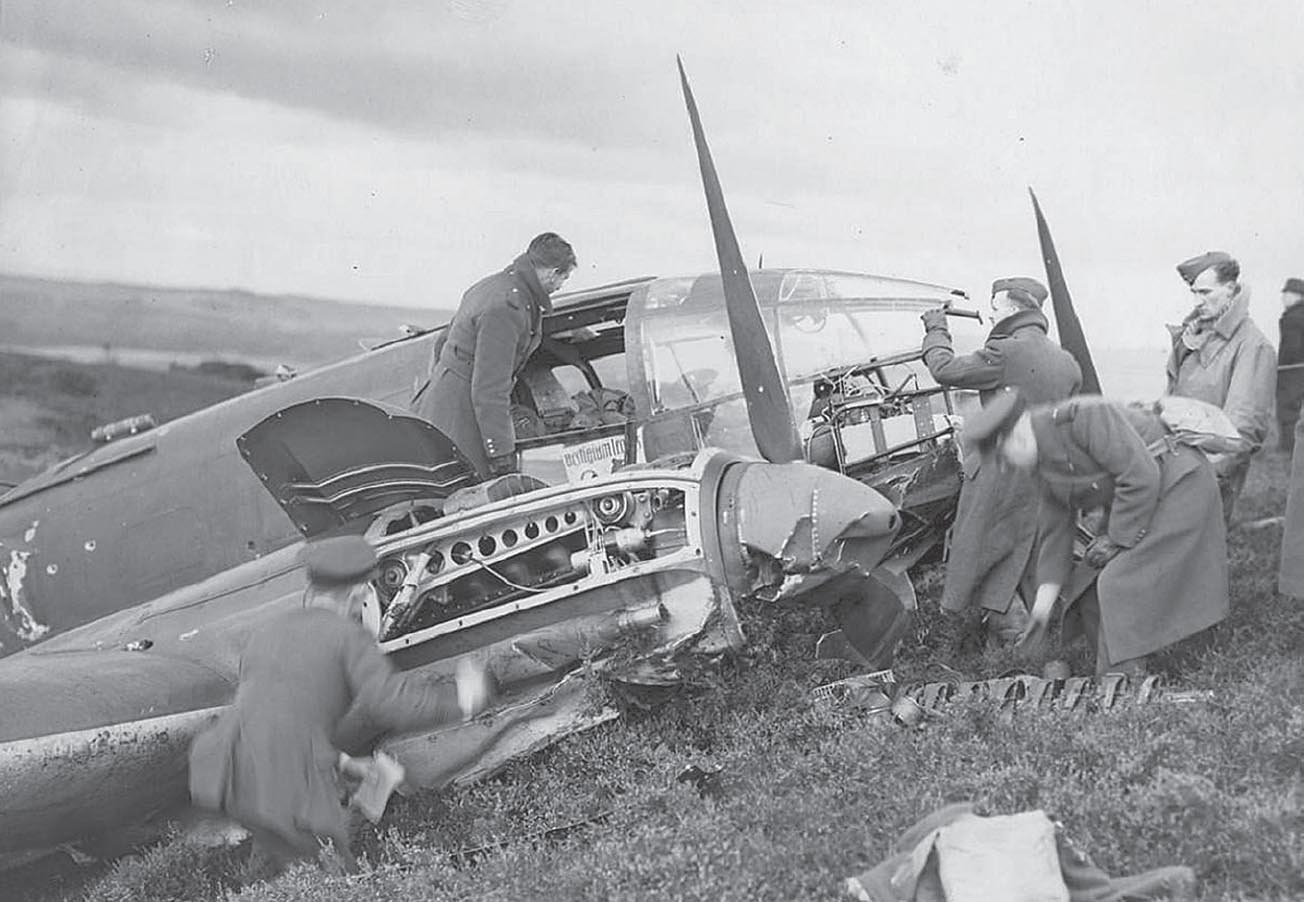

The wreck of the Heinkel He 111 1H+JA of Stab./KG 26 shot down near Humbie, Scotland, on 28 October 1939; the first German aircraft to be brought down on mainland Britain since the war had begun. Leutnant Adolf Hiehoff (observer) and Uffz. Kurt Lehmkuhl (pilot) were captured, the latter wounded in the back by two bullets from pursuing Spitfires. Both Uffz. Gottlieb Kowalke (flight engineer) and Gefr. Bruno Reimann (wireless operator) were killed.

During November, Küstenflieger losses mounted steadily through enemy action, accidents, mechanical failure and at least one incident of friendly fire, in which a Bf 110 damaged a Do 18 of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 returning from patrol and misidentified as British. Although there were no casualties the Dornier was compelled to make a forced alighting, later being recovered by the ship Hans Rolshoven and repaired. On 29 November SKL recorded in its War Diary a ‘black day for the Naval Air Force’, with five of the seventeen Do 18 reconnaissance aircraft shadowing light naval forces and a convoy in the Shetland-Bergen passage lost. All five belonged to Küstenfliegergruppe 406. Two were shot down by British aircraft, both crews being rescued and interned in Norway, and a third was also interned after coming down with engine failure near Mandel, Norway. The fourth was forced to alight near the Faeroes after losing a propeller in stormy weather; all four men were rescued by the Danish coastguard vessel Islands Falk and interned. The final Dornier crashed into the sand dunes at Hörnum in darkness, killing all on board. Two Do 18s of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 were also badly damaged that same day after colliding in the darkness.

On Christmas Eve Raeder approved the despatch of a teletype to Luftwaffe command regarding the operational readiness of the Naval Air Arm. Within its text he urged the upgrading of the Küstenfliegergruppen, and stressed the potential unsuitability of the obsolete Heinkel He 111J undergoing trials for maritime operations. One had been written-off at Kamp after failure of the starboard engine immediately following takeoff on 27 November, a second at Dievenow on 14 December, and a third had crashed on 5 January.

1. The freezing of the naval air bases on the North Sea coast makes sea reconnaissance over the main theatre of war impossible. Land-based groups (Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 with He 111J aeroplanes) cannot be used as substitutes, since these aeroplanes are so antiquated they cannot be made serviceable in less than three months. The Air Force General attached to the Commander-in-Chief, Navy, reported that use of the He 111J aeroplanes for operations over the North Sea cannot be endorsed owing to technical deficiencies.

2. Immediate replacement of the He 111J aeroplanes of Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 with He 111H or P aeroplanes, later on with Ju 88s, is imperative, since otherwise the tasks set by the Führer cannot be carried out. This request is not based on the limited ice period, but mainly on the need to increase the fighting power and speed of our naval reconnaissance aeroplanes.

The He 115 and Do 18 are in every respect inferior to all British types of aeroplanes which have so far been encountered over the sea (Blenheims, Wellingtons).26

The Dornier Do 26 flying boat ‘Seeadler’ during its pre-war service with Lufthansa; one of the civilian aircraft impressed into the Luftwaffe to form the Transozeanstaffel, commanded by Major Friedrich von Buddenbrock. Flying overhead is a Dornier Do 18.

As if to underline his second point, Do 18 8L+CK of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 was shot down on 27 December by a patrolling Hudson of 220 Sqn, making an emergency descent on to the sea. Hptgfr. Josef Reitz was killed by the Hudson’s gunfire. Aircraft commander Lt.z.S. Dietrich Steinhart, Hptfw. Schmidt and Uffz. Czech were all rescued by the Swedish steamer Boden and landed in Gothenburg, where they were interned until January 1940. Theirs was the final loss suffered by the naval air units in 1939.

At sea, aircraft of the Bordflieger Staffel had also suffered casualties. Three Arados had been damaged aboard Gneisenau; one by mishandling while being hoisted aboard after descent, two others by storms encountered on 29 November after sailing in company with sister ship Scharnhorst, the light cruiser Köln and nine destroyers to patrol the area between Iceland and the Faeroe Islands. The Gneisenau group was intended to draw enemy forces away from pursuit of the ‘pocket battleship’ Admiral Graf Spee, which was under increasing Royal Navy pressure while on its successful Atlantic raiding voyage. The group encountered the British auxiliary cruiser HMS Rawalpindi which, hopelessly outgunned, bravely turned to fight and was sunk in forty minutes. However, both German battleships suffered the effect of heavy seas and high winds while returning to Germany, all three Arados carried aboard Scharnhorst being considerably damaged.

The object of the Royal Navy’s attention far to the south, the Admiral Graf Spee, had been on a commerce-raiding mission since the outbreak of war, having departed Germany on 21 August. Under strict instructions to avoid combat with enemy naval units, Kapitän zur See Hans Langsdorff had used his single Arado Ar 196A-1 seaplane to advantage, finding targets and also successfully avoiding enemy warships by the use of highly effective aerial reconnaissance. Commanded by Oblt.z.S. Detlef Spiering and flown by Flugzeugführer Uffz. Heinrich Bongards, the aircraft suffered a cracked engine block following a reconnaissance flight on 6 October and was inoperative for several days while the five on-board support personnel fitted a spare engine.

The difficulties of operating a catapult aircraft at sea were many, enemy interference being the least of the aircrew’s concerns. If, once aloft, on-board navigation in the vast expanses of the ocean was imprecise, any planned return rendezvous of ship and aircraft could be foiled, leaving the aircraft stranded. Even once contact had been re-established, all but the calmest sea rendered floatplane alightings difficult. Oberleutnant Helmut Mahlke was observer aboard the He 60 floatplane of 1./BFl.Gr. 196 carried aboard the ‘pocket battleship’ Admiral Scheer during its 1938 voyage into the Mediterranean, his pilot being Lt. Köder.

In order to put down safely we usually had to ask the Scheer for the ‘duck-pond.’ This she would produce by performing a sharp 30-degree turn to port; the turbulence of her wake would smother the heavy swell to create a relatively calm patch of water within her turning circle. And if the duck-pond wasn’t sufficient, we had to resort to the landing mat. As its name suggests, the landing mat was just that: a small rectangular mat of reinforced canvas that would be paid out from a swinging boom on the port side of the ship forward, and streamed on the surface of the water close alongside. For a pilot, landing on the mat was the ultimate test. It was so narrow that he could not afford to be more than a metre off the centreline if the aircraft was to be recovered intact. A few more centimetres to the right and the starboard wingtip would be smashed against the side of the ship. A few more centimetres to the left and the port float would miss the landing mat and the machine might be lost altogether.27

Reconnaissance missions by Spiering and Bongards from Admiral Graf Spee resumed on 22 October, though the Arado’s propeller was damaged soon afterwards while the aircraft was being hoisted back aboard ship. Once repaired, on 9 November, following a further reconnaissance flight, a crack was once again discovered in the engine block at exactly the same place as previously. As there was no second spare engine, the crack was bordered with a steel band and cemented together to enable the aircraft to fly once more, albeit with less than optimal performance. Spiering led the aircraft on further flights before radio failure on 2 December rendered communication with the ship impossible and necessitated an emergency landing at a prearranged rendezvous point. During this touchdown the Arado’s port float was damaged, gradually filling with water and threatening to capsize the battered aircraft before Langsdorff’s ship arrived to retrieve it. After further repairs, more reconnaissance flights were made until, on 11 December, a succession of hard alightings split the engine block completely, beyond the scope of on-board repair. The aircraft was ordered to be dismantled.

Two days later, on 13 December, the Royal Navy hunting party of HMS Exeter, Ajax and Achilles found Graf Spee off the River Plate, Commodore Harwood immediately attacking. Despite heavy damage to the British ships, Graf Spee was hit by seventy shells and suffered thirtysix men killed and sixty more injured, including Langsdorff, who was wounded by shell splinters while on the bridge. Pilot Uffz. Bongards and mechanic Ogfr. Hans-Eduard Sümmerer were both killed during the exchange of fire, and the partly dismantled aircraft was set on fire and completely burnt out.

Within four days the much-storied scuttling of Admiral Graf Spee took place in the River Plate estuary, and the remaining members of Bordfliegerkommando 1./BFl.Gr. 196 from the heavy cruiser were interned in Argentina. Of those, three successfully returned to Germany by June 1940, including Oblt.z.S. Spiering. Following his return, Spiering was transferred to the Luftwaffe, promoted Hauptmann on 1 March 1942, and transferred to KG 26, the Luftwaffe’s torpedo group. Appointed Staffelkapitän to 7./KG 26, he was listed as missing in action after his Ju 88A-4, 1H+AR, was lost during an attack on Allied ships near Syracuse on 27 July 1943.