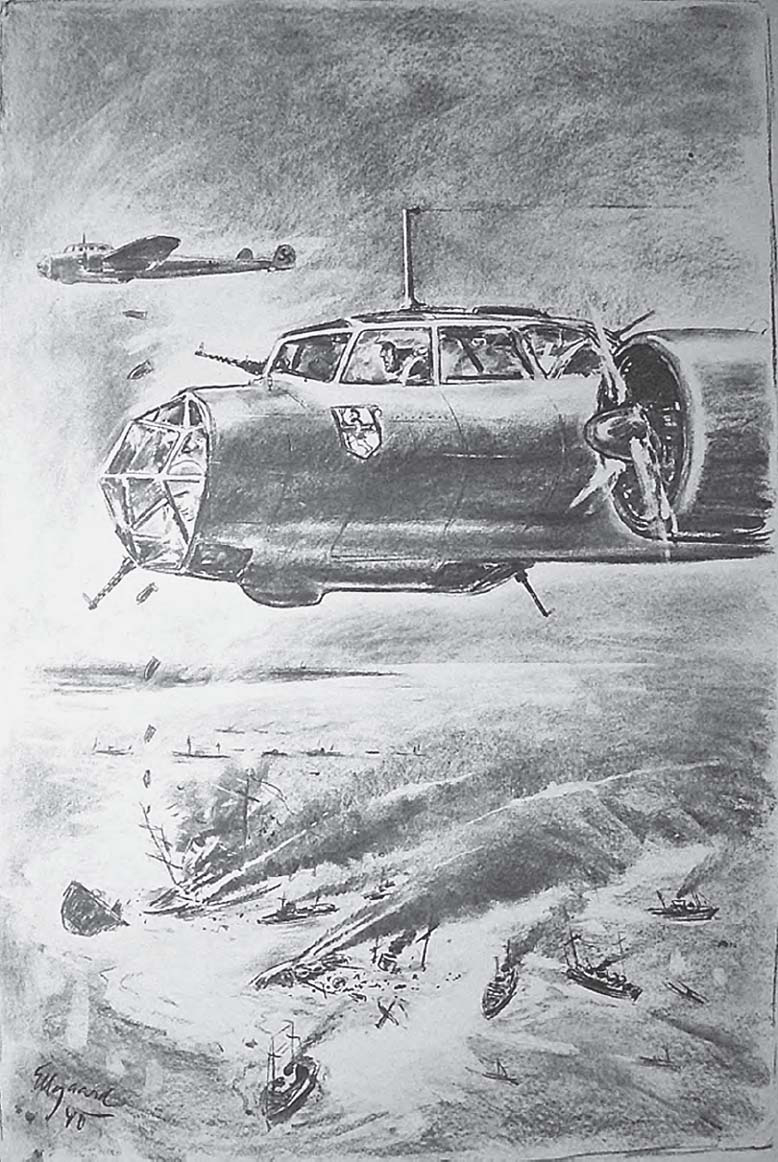

A rather fanciful German war artist’s impression of Dornier Do 17 bombers over British shipping near Dover. Küstenfliegergruppe 606 re-equipped with these wheeled bombers in late 1939, considered a land-based ‘Kampfgruppe’ thereafter.

THE NORTHERN EUROPEAN WINTER of 1939/1940 was the coldest on record for over one hundred years, caused by arctic air currents from the Siberian interior that lasted from mid-December 1939 through to March 1940. Northern Germany was particularly affected, with recordsetting conditions that clogged harbours with thick ice and frequently rendered seaplane bases inoperative. Emphasis was instead placed on the Küstenflieger’s few available wheeled aircraft and those of the operational Luftwaffe.

Air reconnaissance and proposed reconnaissance of lights [minelaying] along the enemy south-east coast had to be abandoned because of the weather. Since air reconnaissance by the Naval Air Force is frequently prejudiced or rendered impossible by ice, X.Fliegerkorps has already taken over as much of the air reconnaissance over the North Sea as possible. The previous tacit agreement on this was expressly confirmed by the Commander-in-Chief, Air Force, in the following tele print:

Until further notice X.Fliegerkorps will, in direct agreement with Naval Group Command West, take over as many reconnaissance assignments over the North Sea as possible, if Commander-in-Chief, Navy’s reconnaissance forces are not adequate. X.Fliegerkorps will make the decisions regarding Operations.1

The conversion of Küstenfliegergruppe 806 to the Heinkel He 111J continued to be fraught with difficulties, as the type was plagued with problems, particularly regarding its inefficient powerplant. Four were lost or severely damaged due to engine failure between 27 January and 8 April 1940, and another two collided after landing, while taxiing to their dispersal areas. By the beginning of February the conversion period had been completed and twelve aircraft were declared operational at Sagan- Küpper, and another twenty at Kiel-Holtenau, five machines being held in reserve at Nordhausen. However, towards the end of the previous year the obvious shortcomings of the obsolete Heinkel had prompted both 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 to continue using He 59s, He 60s and He 114s when possible, alongside the landplane bombers, to enable both operational missions and training to continue amidst repetitive breakdowns and malfunctions. With 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 temporarily attached to the staff of Küstenfliegergruppe 906 for Heinkel He 111 conversion (and its place taken by 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906), those crews still operational continued to mount patrols over the Skagerrak and North Sea, hunting for enemy submarines and intercepting merchant ships with a Prize Crew carried aboard the He 59s. On the last day of December 1939 the strength of Küstenfliegergruppe 806 was reported by F.d.Luft Ost as:

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806: five crews operationally ready; two He 111s and one W 34 in service; ten He 111s and one W 34 out of service.

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806: eight crews operational, including two trained in blind flying; four He 60s, two He 114s, six He 111s and one W 34 in service; one He 114, four He 111s and one W 34 out of service.

(Attached) 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906: nine operational crews; three He 60s, three He 114s, five He 59s and two W 34 in service; one He 60, one He 114 and four He 59s out of service.

The small Junkers W 34 was a single-engine passenger and transport aircraft developed during the 1920s, and thereafter used as a training aircraft or pushed into active service as a stop-gap measure, armed with ventral and dorsal machine guns and capable of carrying six 50kg bombs. It was used in both training and combat roles by the Küstenfliegergruppe, though as early as December 1939 it was decided that no responsible command could assign the type to maritime operations. Nevertheless, it remained a useful training aircraft, although not without peril, as on 30 January, when the W 34L TY+HL of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806, involved in blind-flying exercises at Holtenau, crashed from a height of only 20m after the engine had been insufficiently warmed-up before takeoff. Pilot Obfw. Murswiek and Uffz. Helmut Niklas were killed, and another pilot in training, Uffz. Emil Podstufka, and wireless operator Ogfr. Karl-Rudolf Holz were both severely injured and later succumbed to their wounds.

In the meantime, the conversion of Küstenfliegergruppe 606 to the Dornier Do 17 proceeded more smoothly, though presumed pilot error caused the loss of Uffz. Georg Lindauer’s aircraft only 400m from the beach at Deep after it crashed into the sea during exercises, killing the entire crew. Flying practice also caused the loss of Scharnhorst’s 1./ BFl.Gr. 196 Ar 196A-2 T3+NH, flown by pilot Uffz. Hans Ritter and commanded by observer Lt.z.S. Heinz-Paul Steudel. Ritter crashed while performing a low-altitude turn in the Schillig Roads off Wilhelmshaven, and the aircraft immediately submerged, killing both men. Their bodies were recovered by a vessel of the Wilhelmshaven Hafenschutzflottille and later returned to Scharnhorst.

The Staffel provided a final escort for the two dead before they were transferred to their home towns. Three officers and one NCO attended the funerals.2

The Arado wreck was subsequently located by Hafenschutzflottille vessels using mine-detection equipment, recovered by crane and taken ashore by the tug Hermes for its valuable metals to be salvaged. The destroyed Arado had originally joined Scharnhorst on 13 February 1940, as one of two Ar 196s, T3+HH and T3+NH, accompanied by a total of three crews attached the battleship’s complement who came aboard the next day. Staffelkapitän Hptm. Gerrit Wiegmink transferred to the battleship as senior flight officer, while the three crew commanders/observers were naval officers: Oblt.z.S. Jürgen Quaet-Faslem, Oblt.z.S. Peter Schrewe and Lt.z.S. Steudel. Quaet-Faslem had joined the Reichsmarine in the late 1920s, serving in the naval air arm since his days as a Fähnrich. In 1942 he would transfer to the U-boat service and later command U595, which was sunk on its maiden patrol on 14 November 1942. Captured by the United States Navy, Quaet-Faslem was described as ‘among the less pleasant of the U-boat captains so far encountered. He was bitter, taciturn, and barely civil, and the hatred in his eyes was apparent to all who talked to him.’3 Peter Schrewe had also enlisted in the Reichsmarine, though in April 1934 as an officer cadet. He too transferred to U-boats in 1942, being in command of U537 when it was sunk with all hands in the Java Sea on 10 November 1944. All three pilots, Obfw. Kroll, Uffz. Hans Ritter and Uffz. Ludwig, were Luftwaffe personnel, as were the seven technical support crew.

Following the death of Steudel and Ritter, replacement aircraft T3+KH was brought aboard Scharnhorst on 11 March, crewmen Lt.z.S. Ernst-Joachim von Kuhlberg and Oblt. Gerhard Schreck following within a fortnight.

A rather fanciful German war artist’s impression of Dornier Do 17 bombers over British shipping near Dover. Küstenfliegergruppe 606 re-equipped with these wheeled bombers in late 1939, considered a land-based ‘Kampfgruppe’ thereafter.

As new Ar 196A-2s were taken on strength with the Bordfliegerstaffel during March 1940, its last He 42, Sd+CC, and last three Ar 196A-1s were taken out of service, while the Staff took control of small W 34 BB+MR from F.d.Luft purely for transportation purposes. The shorebased aircraft of the Bordfliegerstaffel flew periodic reconnaissance and ASW missions from Wilhelmshaven, as well as intercepting encroaching RAF Blenheims as they probed German defences along the North Sea coast, where the bombers of Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps continued to mount harassing attacks on merchant shipping.

Increasing numbers of fast Ju 88s had been declared operational with KG 30, a second operational Gruppe having been formed around a cadre taken from the Ju 88 training unit (Lehrgruppe 88) and declared operational early in December 1939, and III./KG 30 following during January in the same fashion. A newly established Geschwaderstab under the command of Obstlt. Walter Loebel (previously the commander of I./KG 26), brought KG 30 to its full complement and parity with Heinkel-equipped KG 26. Henceforth, Geisler ordered the Heinkels of the ‘Löwen’ Geschwader KG 26 to concentrate their efforts primarily on merchant shipping, leaving the Ju 88s of the ‘Adler’ Geschwader to attack the Royal Navy. During February a new unit designated Kampfgruppe 126 (KGr.126) was established from III./KG 26, under the command of former Küstenflieger Hptm. Gerd Stein; charged with minelaying while simultaneously conducting operational tests of the Heinkel He 111 bomber in the role of torpedo carrier.4

Although weather conditions frequently curtailed flying, sporadic operations were still mounted, resulting in steady casualties both among merchant shipping targets and the maritime bombers themselves. As the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet had now temporarily abandoned Scapa Flow for the distant anchorage of Loch Ewe, Luftwaffe maritime strike forces switched their attention to shipping off the Scottish coast.

On 9 January armed reconnaissance was carried out between the Thames and Kinnaird Head, and over the course of the day aircraft successfully attacked unescorted merchant shipping. The 689-ton steamer SS Gowrie was sunk four miles east of Stonehaven, all crewmen being rescued, followed by the 1,985-ton SS Oakgrove twelve miles SE by E of the Cromer Knoll Light Vessel, sending 2,900 tons of iron ore to the bottom and killing its Master, William Duke Falconer.5 The 1,103-ton coastal freighter SS Upminster was also severely damaged further south, off Cromer, sinking the next day. Master Alfred Hunter, Able Seaman James Stubbs and Able Seaman William Robertson Young were all killed. Survivors described how the two Luftwaffe aircraft ‘swooped down and attacked us first with machine guns and then with bombs’.6 The British cargo ships SS Northwood and SS Reculver, the trawler Chrysolite and the Danish steamers SS Ivan Kondrup and Feddy were also damaged by further attacks along the east-coast shipping lanes. Misty weather prevented RAF fighter defences from establishing contact with the German bombers, though Fw. F. Pfeiffer’s Ju 88 of 2./KG 30 came down near Sylt after being hit by anti-aircraft fire.

In Berlin, Raeder’s staff were enthusiastic about the attacks against merchant shipping off the British coast, reasoning that they were ‘highly suited for the intimidation of enemy and neutral ships alike’, particularly when mounted in conjunction with ongoing minelaying. Throughout January X.Fliegerkorps continued its operations along the east coast, and harvested a grim tally of ships sunk or damaged, both in convoy and sailing independently. Attacks against Scapa Flow were less successful in the face of heavy anti-aircraft defences, and hampered in at least one case the icing of a Ju 88’s bombsight during an attempted dive-bombing attack. However, the enthusiasm among Kriegsmarine officers was noticeably lacking among their Luftwaffe counterparts, who considered the assault on mainland Britain to be their highest priority.

The Naval Staff attaches great significance to these most gratifying successes on the part of the Air Force and considers operations by X.Fliegerkorps in support of naval warfare as often as possible of great importance. Since the Luftwaffe itself seems to attach little value to the results obtained, the Luftwaffe General Staff is being informed of the Naval Staff’s opinion.7

The Luftwaffe had ample reason to share the Kriegsmarine’s gratification at the results of the anti-shipping missions mounted in the North Sea. On the other side of the hill, RAF Fighter Command was feeling overstretched and unable to keep pace with the demands placed upon it for protection of merchant shipping along Britain’s east coast. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding considered that the primary responsibility of Fighter Command was the protection of aircraft factories and London against the threat of massed bomber attacks. He believed that the protection of mercantile traffic at sea lay within Coastal Command’s sphere of responsibility, although he had willingly included four planned fighter squadrons allocated to Trade Defence, yet they were not scheduled to begin formation until the financial year beginning April 1940.

Dowding in no way denied the use of his fighters to protect the vulnerable shipping, but he agreed with a joint political memorandum issued by Lord Stanhope and Sir Kingsley Wood during June 1939 that, in the event of war and enemy air attacks on east coast merchant shipping, Fighter Command would be unable to provide effective protection unless the ships were routed close inshore, and even then they considered it unlikely that sufficient warning could be given to launch a successful fighter interception. The existing Radio Direction Finding (RDF) system did not, as yet, detect low-flying bombers, and the likelihood of it providing effective assistance to fighters operating more than five miles offshore was slim. Likewise, aerial defence of the remote anchorage at Scapa Flow remained problematic to Fighter Command, stretching its meagre resources to the absolute limit.

Dowding was forced to move several squadrons nearer the coast and further from the industrial centres thought likely to be the target of the Luftwaffe before long. Four Fighter Command squadrons under formation, 235, 236, 248 and 254 Sqns, were temporarily transferred to Coastal Command in lieu of the planned Trade Defence units; a situation with which neither Dowding nor his counterpart in Coastal Command, Air Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, were particularly pleased, as both wished to retain the squadrons permanently, Dowding as a nucleus for the fixed creation of Trade Defence which he believed was likely to be made solely his responsibility in the near future, and Bowhill for long-range maritime reconnaissance. Nonetheless, the squadrons were equipped with Blenheims and transferred to coastal operational airfields during February 1940. Unfortunately for the protection of merchant shipping, apart from 254 Sqn the remainder were generally used for maritime reconnaissance and escorting naval operations, rather than for their planned purpose.

The harassment of British trawlers by X.Fliegerkorps in the North Sea continued, though not without Luftwaffe losses at the hands of Dowding’s fighters. On 3 February Heinkels of KG 26 attacked shipping off the north-east coast and faced defensive fire from Royal Navy ships as well as interception by RAF fighters. Heinkel 1H+FM of II./KG 26 was detected by the Danby Beacon Chain Home base on the North Yorkshire Moors at 0903hrs, sixty miles out to sea. Three Hurricanes of 43 Sqn, based at Acklington, intercepted after the Heinkel, commanded by observer Uffz. Rudolf ‘Rudi’ Leushake, had already attacked a trawler. Flight Lieutenant Peter Townsend led the Hurricanes into a fierce counterattack, killing Leushake and damaging the starboard engine. A second attack by Fg Off Patrick Folkes caused further damage and mortally wounded mechanic and ventral gunner Uffz. Johann Meyer in the stomach. Further attacks hit wireless operator and dorsal gunner Uffz. Karl Missy in the leg, which was later amputated, and forced the Heinkel to crash-land on a snow-covered field, coming to rest near the farm cottages at Bannial Flat Farm, Whitby. It was the first enemy aircraft to crash on English soil. Missy and pilot Fw. Hermann Wilms were captured, and had to be protected from an angry mob of locals by being held in the nearby farmhouse until removed under guard for hospital treatment. Theirs was the sixth Heinkel of KG 26 lost to enemy aircraft during 1940, and the eleventh since war had begun.

Two merchant ships were sunk that day; one unidentified vessel east of Farne Islands and the Norwegian SS Tempo off St Abbs Head, but for the loss of three Heinkels. As well as Leushake’s, aircraft, 1H+HL of 3./KG 26 was shot down by Fg Off John Simpson of Acklington’s 43 Sqn while attacking shipping south-east of the Farne Islands, Lt. Luther von Bruning and his crew all being killed. Simpson last saw the Heinkel trailing smoke as it disappeared into a bank of sea mist before crashing in Druridge Bay.

Feldwebel Franz Schnee’s Heinkel, 1H+GK of 2./KG 26, was also shot down by 43 Sqn, Sgts Frank Carey and Ottewill brought it down it off the Northumberland coast as it attacked a small convoy. Flight mechanic Uffz. Willi Wolf was killed by the machine-gun fire and both engines were disabled, forcing pilot Obfw. Fritz Wiemer to ditch the He 111 approximately fifteen miles off Tynemouth. It sank in a little over a minute, leaving the crew bobbing in their kapok lifejackets until they were rescued by the trawler Harlech Castle and landed in Grimsby. Air gunner Uffz. Karl-Ernst Thiede was badly wounded as he was taken aboard, and subsequently died of his injuries. Another crew member suffered a broken leg during the crash. Although the Germans had managed to discard personal papers and the like before being picked up, owing to a major oversight by one of the captured Germans a signals table was found in one of the airmen’s pockets, giving wireless frequencies, recognition signals and call signs for use by KG 26.8

That same day, three Ju 88s from 2./KG 30 took off from Westerland and attacked ships of the 5th Minesweeping Flotilla operating in the Moray Firth. Under air attack during drifting snow flurries fifteen miles north of Kinnaird Head, HMS Sphinx was hit by a single bomb that exploded in the forward structure, causing extensive damage and rapid flooding. HMS Harrier attempted to take the minesweeper in tow, but failed due to the deteriorating weather conditions, and Sphinx finally capsized. The upturned hull drifted ashore two miles north of Lybster. Fifty-four men had been killed in the first loss of a Fleet Minesweeper during the Second World War. In return, the Ju 88 belonging to the Staffelkapitän of 2./KG 30, Hptm. Heinz-Wilhelm Rosenthal, was brought down by ground fire.

During late January and early February, German aerial reconnaissance reported the frequent presence of numerous unidentified fishing vessels and apparently neutral ships in the area of the Dogger Bank. Unsure of their purpose or identity, MGK West planned to send the 1. Zerstörerflottille to launch a surprise stop-and-search operation against what were strongly suspected to be enemy trawlers reporting German shipping and aerial movements. Originally scheduled for the night of 26/27 January, the operation, codenamed Wikinger, was postponed owing to adverse weather conditions, and did not begin until 22 February, when Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt, flying the pennant of flotilla commander Fregattenkapitän Fritz von Berger, Z4 Richard Beitzen, Z13 Erich Koellner, Z6 Theodor Riedel, Z3 Max Schultz and Z1 Leberecht Maass sailed at midday, carrying additional boarding parties for the searching and possible seizure of suspect vessels. Initially, the Luftwaffe had been asked to provide fighter cover for the departing destroyers, though communication problems resulted in no fighters making an appearance. There were, however, other German aircraft on operations.

During the previous day Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps had planned further missions against merchant shipping along Britain’s east coast, the Heinkels of KG 26 being ordered to attack any targets of opportunity between the Orkney Islands and Thames estuary. Anything outside of this specific operational region was deemed off-limits for this mission. The morning flights originally scheduled were cancelled owing to bad weather, and the first aircraft did not take off until 1745hrs that evening; two Staffeln departing Germany; 4./KG 26 to fly against targets between the Thames and Humber estuaries, and 6./KG 26 to concentrate on shipping further north.

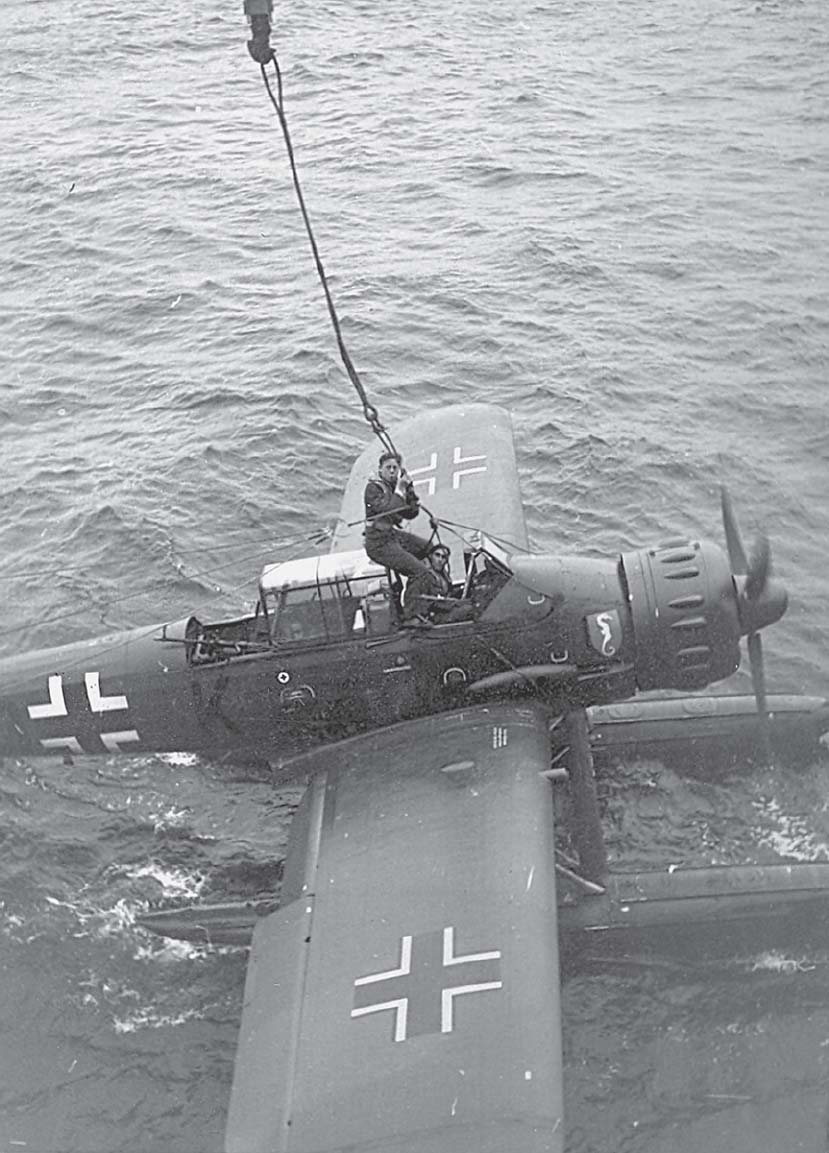

Luftminen being prepared for loading aboard an He 111.

The He 111 bombers of 4./KG 26 left from Neumünster Airfield. Among the first to become airborne was 1H+IM, piloted by Fw. Jäger, who took a northerly course until he was over the island of Sylt, where he banked left and followed a heading of 241 degrees out over the dark North Sea. Shortly after 1900hrs Jäger’s crew detected a wake on the sea below them, with an indistinct shadow preceding it. Although they did not know it, they had reached the six German destroyers travelling in line-ahead formation to the north-west, producing a bright wake as they ran at high speed along the mine-free passage ‘Weg I’, a six-mile-wide gap in the defensive ‘Westwall’ minefield that protected the German Bight. The aircraft, in turn, was heard and then sighted by lookouts aboard the leading ship, the Friedrich Eckoldt, flying at an altitude of only 500-800m and passing overhead without incident, but failing to show any of the agreed recognition signals dictated by protocol. Although it displayed no hostile intent, the aircraft turned and passed over a second time, still unidentified by the Kriegsmarine sailors below.

Jäger and his observer, Fw. Schräpler, were convinced that they had contacted a single freighter, the ship itself at no time being clearly sighted and showing no identification signals even after a second pass, but he remained hesitant to attack as the Heinkel had not yet reached its designated target area. The tension was broken when the second and third ships in line, the Richard Beitzen and Erich Koellner, fired several 20mm warning shots at the aircraft that they now suspected to be a British reconnaissance flight. Aboard the Heinkel, Fw. Döring immediately returned fire using his ventral machine gun. Only at the last moment did lookouts aboard the tail-end ship, the Max Schultz, report the aircraft as carrying German markings, but the destroyer’s brief and urgent radio message on the communal wavelength was ignored. Aboard the Max Schultz, Oblt.z.S. Günther Hosemann reported definitely having seen the aircraft’s markings, and firmly identified it as German in the flash of the warning shots, though others remained sceptical. At 1943hrs the Max Schultz detected the aircraft approaching for a third time from astern, emerging from a cloudbank with the moon directly behind it. A brief radio message was sent: ‘Flugzeug ist gesichtet worden in der schwarzen Wolke des Mondes’ (aircraft detected in the black cloud in front of the moon) as Jäger began his bomb run at an altitude of 1,500m, convinced by the gunfire that their target was hostile.

Four bombs were dropped. Two impacted the sea immediately behind the Leberecht Maass, the third hit the destroyer between the forward superstructure and funnel, and the fourth missed completely. Although there was no visible smoke or flame, the crippled destroyer slowed and veered to starboard, signalling for assistance from its flotilla-mates, but as other destroyers steered to render aid they were ordered back into formation lest they run on to the flanking German minefields. The lead ship, the Friedrich Eckoldt, slowly approached the Leberecht Maass to investigate the damage visually as rescue equipment and towing gear were made ready. When it was only 500m away, the still-unidentified aircraft returned for a second bombing run thirteen minutes after its first. Two out of another four bombs hit the damaged destroyer, a huge fireball blowing upwards from the second funnel as the ship was enveloped in thick smoke until the gentle breeze dispersed the choking cloud. Aboard the Friedrich Eckoldt, horrified observers saw that the Leberecht Maass had been broken in two, both bow and stern jutting out of the water as she sank in 40m of water. Above them, the Heinkel crew broke away and headed west, only at that moment sighting the shapes of accompanying ships below them.

The remaining destroyers steamed slowly towards the wreck and its survivors swimming in the frigid North Sea water. The Erich Koellner stopped engines in order to drift toward survivors swimming between the two parts of the wreck, with boats swung out to begin the rescue, along with those lowered from the Friedrich Eckoldt and Richard Beitzen. Suddenly, at 2004hrs, another huge explosion was observed, lookouts aboard the Richard Beitzen confusingly reporting a fresh air attack, though there had been no sighting of aircraft. The Theodor Riedel, only 1,000m from the explosion, was heading towards the fireball when its hydrophones detected a submarine contact to starboard, causing fresh confusion among the German destroyers. Fearing a British submarine attack, the Theodor Riedel ran down the contact and dropped four depth charges, which exploded too close to the ship’s hull and jammed the rudder, causing the ship to run in lazy circles until manual control was established. The remaining destroyers continued their rescue operation until a lookout aboard the Erich Koellner also reported a submarine sighting. Flotilla commander Berger ordered all rescue operations to be halted immediately, and for the submarine to be hunted to exhaustion, at that point establishing that the Max Schultz was no longer answering radio calls. The Erich Koellner had not even cast off one of her own boats, which was being readied to rescue men from the water. It remained tethered to the destroyer, and was dragged under its stern as it increased speed to engage the ‘enemy submarine’. The Erich Koellner’s captain then attempted to ram a sighted ‘submarine’, but it appears to have been the drifting bow of the Leberecht Maass. Meanwhile, it seems that the hapless Max Schultz, which was stubbornly remaining silent, had had the misfortune to hit a mine recently laid in ‘Weg 1’ by the British destroyers HMS Intrepid and Ivanhoe nearly two weeks previously, though none of this was apparent at the time.9 Confused and hurried messages from the scene were relayed to MGK West, and onwards to SKL, where the scale of the disaster began to unfold:

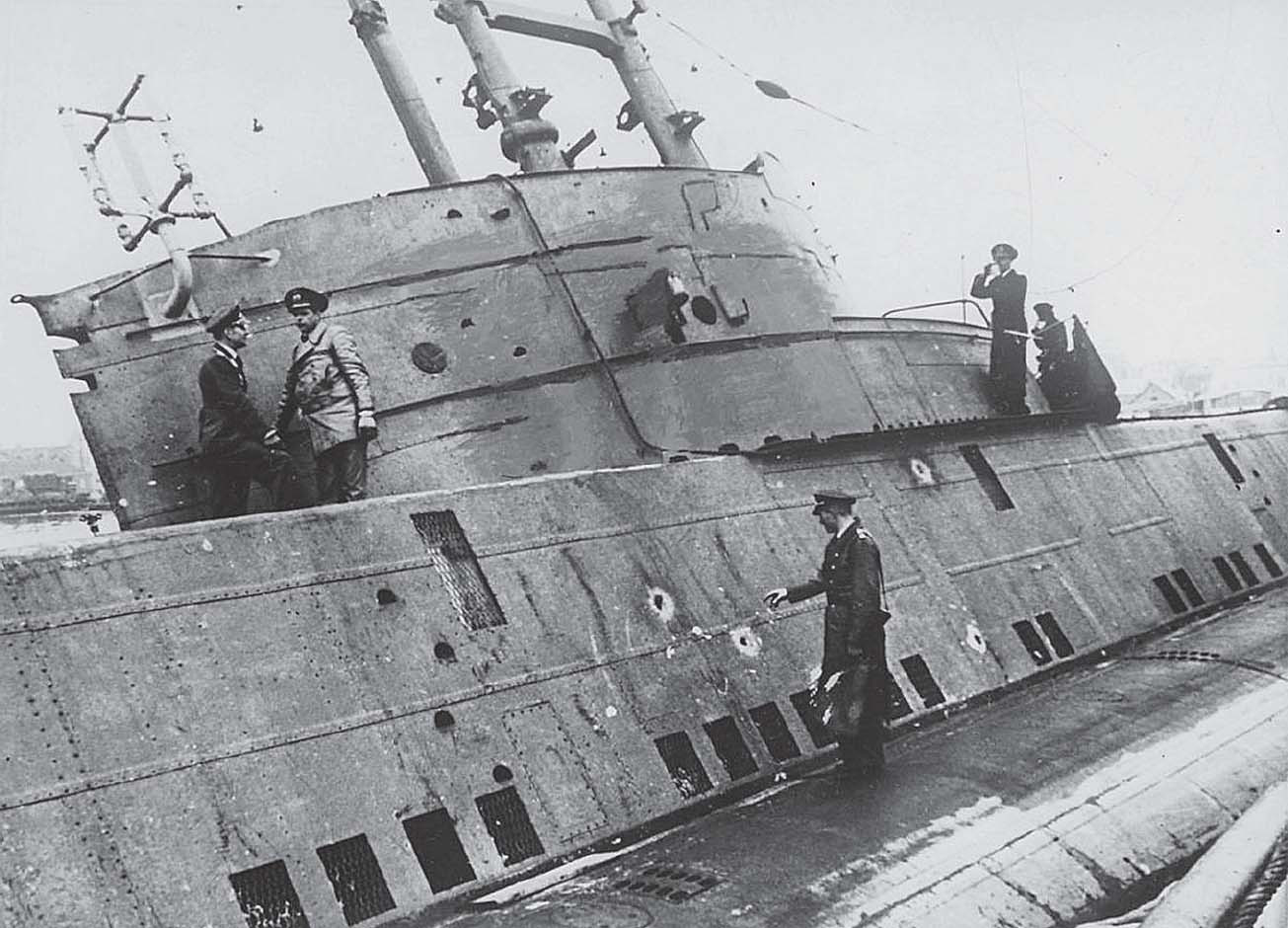

The destroyer Leberecht Maass, accidentally sunk by a KG 26 Heinkel due to chronic miscommunication between air and naval units at every command level.

2018hrs: ‘The Leberecht Maass sunk in grid square 6954, lower left quadrant.’ (This spot lies on ‘Route 1’ more than ten miles from our own nearest minefields in the declared area.)

2050hrs: ‘The Max Schultz also missing. Probably submarine.’

Group West left it to the Commander’s discretion to break off the operation and at 2215hrs informed the flotilla that patrol boat V803 had been sent to search for survivors. Commander, 1.Zerstörerflottille, called off the operation and put in to Wilhelmshaven in the early hours of 23 February. Close investigation should reveal the full facts about the loss of the two destroyers. Pending the result of an examination of ‘Weg 1’ for enemy mines, it is at present assumed that both destroyers were torpedoed by an enemy submarine.

However, doubts swiftly followed as to the cause of the two destroyers’ loss, as SKL recorded later that night, after Jäger had landed and reported sinking a ship fifty kilometres from the actual scene:

KG 26 reported attacks on the British coast and the following incident:

About 2000hrs spotted armed, darkened steamer of 3,000 to 4,000 tons, course 300°, near Terschelllng Bank. Several attacks were made from 1,300 metres. One hit was scored on the forecastle, two hits amidships, ship caught fire and sank. No further observations due to darkness. Light anti-aircraft and machine-gun fire from the ship.

(Margin note: Is this the sinking of the Leberecht Maass and Max Schultz?) The attack on a steamer near Terschelllng Bank is most regrettable and contravenes the regulations issued to the Luftwaffe for the conduct of war on merchant shipping. Air attacks at sea are permitted only in a strip thirty miles wide along the British coast. Closer investigation has been ordered.

At 2036hrs Berger ordered the remaining four destroyers to retreat after recovering the boats that had been left for survivors while they hunted an imaginary submarine. However, most survivors had died of hypothermia in the freezing water during the 25-minute chase of the phantom submarine. Only sixty of the 330 crew members of the Leberecht Maass were rescued, and none of the 308 men from the Max Schultz. A single man was also posted as missing from the Erich Koellner. The planned sailing of a Vorpostenboot to hunt for survivors was curtailed by heavy fog, and no more were found. Later, as if to compound the Wehrmacht’s misery, at 0032hrs a returning He 111 banking low over the island of Borkum from the west was misidentified as British and shot down by Kriegsmarine flak gunners at Holtzendorff’s battery.

The early variant Heinkel He 111J with which Küstenfliegergruppe 806 was equipped and which soon proved obsolete and particularly unsuited for maritime operations.

The ‘Wikinger’ disaster was investigated by a commission of mixed Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine officers, chaired by Generalmajor Coeler, who was considered ideal because his office was unconnected with the events, and including Kapitän zur See Helmuth Heye (former Kriegsmarine Liaison Officer to Göring between 16 March 1938 and April 1939, and current commander of the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper) and Obstlt. Loebel of KG 30. By early March the committee had established the facts and identified a catastrophic breakdown in communications between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine as the root cause of the disaster, including the following timeline of notifications and notification failures that had occurred on the day:

12:18: X.Fliegerkorps sent a teletype message to MGK West that KG 26 will operate against coastal shipping south of the Humber between 1930hrs and 0000hrs. MGK West failed to inform the ‘Wikinger’ destroyers of the aerial operation, and failed to inform X.Fliegerkorps of the destroyers’ movements.

12:35: MGK West wasted an opportunity to rectify this when it sent two radio messages to the destroyers in the North Sea; the first with meteorological information, the second with notice of a British bomber that had been shot down nearby, mentioning nothing of KG 26 operations.

Between 13:00 and 15:00: MGK West contacts the ‘Seeluftstreitkräfte’ to request reconnaissance aircraft for the destroyers’ path (impossible due to ice conditions at the seaplane bases), and to the ‘Jagdfliegerführer Deutsche Bucht’ for air cover during the afternoon and the next morning, when they were expected to return from the Dogger Bank. Neither of these two headquarters was in contact with X.Fliegerkorps, and therefore the bomber crews remained ignorant of German destroyer operations.

16:15: To protect the bombers on their way over the East-Frisian Islands and the coastline, X.Fliegerkorps sent a teletype message to MGK West to request removal of barrage balloons and ask that naval flak batteries be notified of the bombers’ operation (which evidently still failed to safeguard the returning aircraft near Sylt).

17:00: MGK West requested X.Fliegerkorps to prepare covering bombers for the next morning to assist the expected return of the destroyers if possible. This message aroused the curiosity of X.Fliegerkorps’ Chief of Staff, Major Harlinghausen, who had received no notification of destroyers operating in the North Sea that night.

17:35: Major Harlinghausen called MGK West to ascertain whether the Kriegsmarine was operating destroyers in the same area as KG 26 bombers. Although the potential for accidents soon became clear, bomber crews were already on the runways and exercising radio silence, and therefore received no notification. The Kriegsmarine likewise made no radio signal concerning the matter to Berger, at sea.

The enquiry rightly concluded that the attacks on the Leberecht Maass could only be attributed to Jäger’s aircraft. It noted:

This night attack was the first which this crew had ever undertaken. Experience with this kind of operation, including recognising and determining a target, was also lacking. It was only their second-ever night flight over sea, and as such they suffered from lack of experience in managing navigational data. The crew of the aircraft were not informed of the possibility of encountering German vessels . . . In every case, a continuous and extensive briefing of the higher staffs appears necessary. There are no complaints about the conduct of the aircraft or the destroyers.

While SKL accepted the enquiry’s findings, Admiral Alfred Saalwachter at MGK West was extremely defensive, replying to Raeder that it was impossible to brief every vessel under his control of air operations, and noting that the Heinkel had indeed disobeyed standing orders in attacking a ship outside of its operational zone, especially one not firmly identified. Though not without some validity, Saalwachter’s complaint appears more likely to be an officious attempt to deflect blame from exceedingly poor staff work. A furious Hitler himself issued his own directive on the matter, in which he demanded ‘flawless reciprocal briefing’ of command elements on movements on land, sea and air within the same operational area, and also requested the tightening of regulations regarding recognition signals.

While North Sea operations by X.Fliegerkorps continued, the Royal Navy had gradually bolstered its anti-aircraft defences of Scapa Flow with an eye to the Home Fleet returning to the strategically positioned anchorage. Satisfied that enough measures had been taken, Admiral Forbes ordered HMS Valiant and Hood under escort by six destroyers to re-enter Scapa Flow on 7 March, followed soon thereafter by other heavy units. Luftwaffe reconnaissance flights soon detected the Royal Navy vessels, and SKL pressed for attacks to be mounted in order to render the Orkneys militarily untenable once more. German planning for the invasion of Denmark and Norway was already well advanced, and the return of heavy forces to the Orkneys threatened an already thinly stretched naval assault and supply plan that extended along almost the entire length of the Norwegian coast. Raeder and his Staff also correctly surmised that the continuing concentration of major naval forces in Scapa Flow could possibly presage a landing on Norway under the guise of support for Finland’s ongoing struggle against the Soviet Union.

An armed reconnaissance flight over Scapa Flow was mounted by three Ju 88s of 2./KG 30, although iced windows prevented firm identification or attempted attack on ships below, and SKL even doubted whether the crews’ navigation had accurately placed them over Holm Sound. Scrambled Hurricanes of 111 Sqn chased the Junkers and shot down Oblt. Frithjof Sichart von Sichartshoff’s aircraft forty miles east of the Orkneys, the entire crew being lost and reported in Germany as missing in action.

Despite this failure, SKL requested that a major air attack be mounted as soon as weather conditions permitted. They railed against the Luftwaffe having sent only three aircraft, ‘since in this case the anti-aircraft fire can concentrate on the small number of attackers’, and strongly advised that bombing be mixed with mines laid in the Sound, though the latter request was ignored by the Luftwaffe. The raid was finally mounted on 16 March, after a weather reconnaissance flight confirmed conditions acceptable though still subject to rain and snow showers. Eighteen Ju 88s of KG 30, led by Kommodore Major Fritz Doench, were assigned the task of dive-bombing the heavy ships at anchor, while sixteen He 111s of KG 26 bombed ground defences and the islands’ airfields. Although five aircraft were forced to abort due to technical problems, the remainder began their attack at 1950hrs.

The bombers approached virtually undetected via a roundabout route that swept wide over the North Sea at low altitude, only ascending once they had made landfall. The Ju 88s split into small groups and dive-bombed through a fortuitous break in the drifting cloud cover. In total the German fliers claimed two definite hits on a battleship, one hit on either a battleship or battlecruiser, another hit each on an identified battle cruiser and heavy cruiser, and two near misses on capital ships, close enough to assume that some measure of damage was inflicted. A total of 140 SD50 fragmentation bombs and two bombloads of incendiaries was dropped by the KG 26 Heinkels on Hatston Aerodrome and the hamlet of Brig o’ Waithe on the road between Kirkwall and Stromness, as well as on blockships in Skerry Sound, damaging cottages and cratering the airfield at Hatston with eight holes 800 yards from the hangars. At Brig o’ Waithe, 27-year-old road labourer James Isbister was killed, the first British civilian killed by German bombs of the war, and seven others were injured.

When the bombs started to fall James Isbister was at home with his wife Lily and baby son Neil, who now lives in Kirkwall. Across the road a bomb blew apart the house occupied by Mrs Isabella McLeod. James ran to her aid but collapsed a few feet from his own front door, struck down by a shower of shrapnel. The attack was over in minutes, and although others were injured, including Mrs McLeod, who crawled from the shattered remains of her home, James Isbister was the only fatality.10

Heavy fires were left behind by the Heinkels as they retreated out to sea, no attempt having been made to bomb the oil storage tanks at Stromness. No aircraft were lost to enemy action, though Uffz. Werner Mattner and his crew crash-landed on the Danish Baltic island of Lalaand near Magelundgaard Farm. Following a serious navigation error, the crew mistook the island for Sylt in the early morning darkness and belly-landed on flat pasture after exhausting their fuel. Escaping from their aircraft and no doubt realising their mistake, they set fire to the cockpit and were quickly arrested. However, their internment by Danish authorities did not last long. Of the other aircraft, several reported being fired upon by German warships, though it was later found to have been gunnery practice carried out by ‘Schiff 36’, the auxiliary cruiser Orion, soon to depart on its maiden raiding cruise into the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

The results of the attack on the anchored ships, while not insignificant, were well below German assumptions. HMS Norfolk suffered a single near miss to starboard and was hit by one bomb on the port side quarterdeck abaft ‘Y’ turret. It passed through the main and lower decks and exploded in the ‘Y’ shell room, holing the ship below the waterline and causing extensive flooding. In addition, the ‘X’ and ‘Y’ magazines were intentionally flooded as a precaution against ammunition exploding. Three midshipmen and a warrant engineer were killed, and four officers and three ratings wounded. Although the steering gear was damaged, the ship was later able to steam at 10 knots for repairs at the Clyde. HMS Iron Duke was also damaged once again by a near miss, but it made little difference to what was essentially a depot hulk.

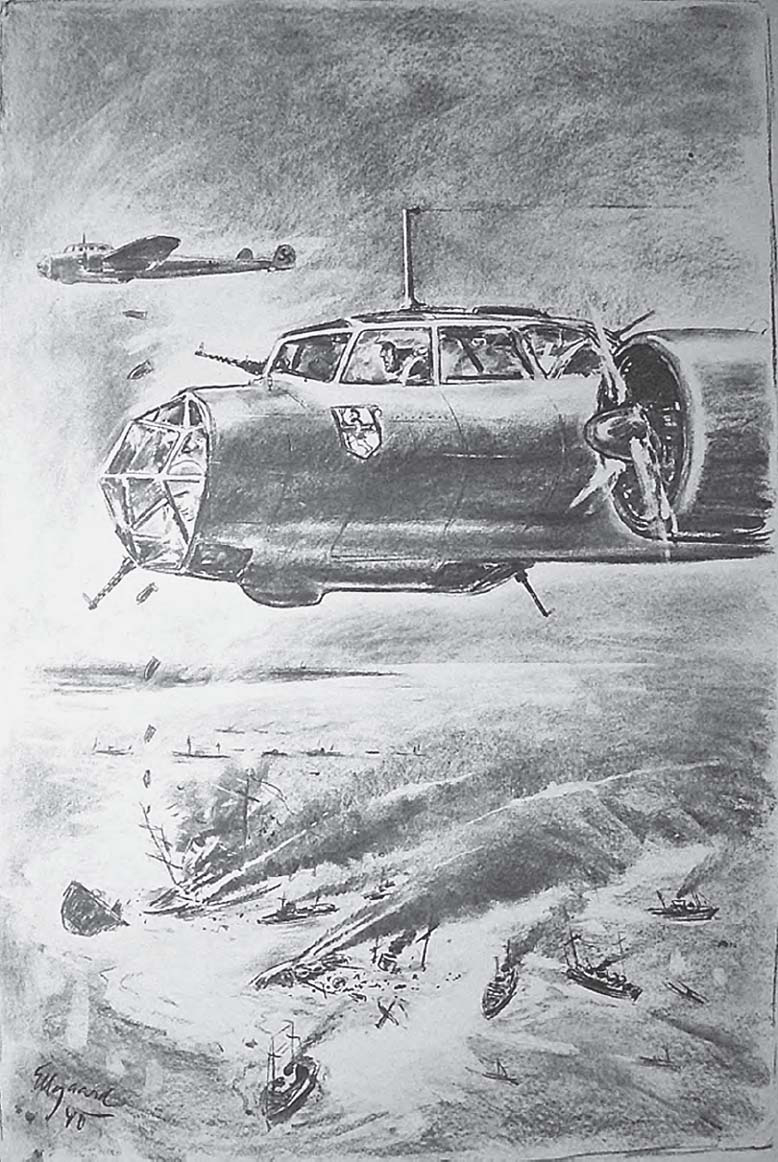

Recovering an Arado Ar 196 of the Bordfliegerstaffel. The officer observer sits astride the canopy to ensure that the steel lifting hawser is firmly attached. (James Payne)

The X.Fliegerkorps has achieved excellent results in the successful attacks on Scapa. The detailed results cannot be checked for the present. According to available reports there is no doubt of some severe and some moderate damage to battleships or heavy cruisers. The ship hit by two 1,000kg bombs must be claimed as out of action for some time. (The Admiralty admits slight damage to one ship only.) The unexpected inadequacy of fighter and anti-aircraft defence in Scapa during the attack is surprising, since it allowed our formation to carry out their attack without losses. It cannot yet be foreseen whether the British Home Fleet, with the knowledge of the severe threat from the air to this base once more confirmed, will now avoid Scapa as a permanent anchorage and move again to the ports and bays of the west coast.

In the interest of the conduct of warfare in the North Sea and of bringing German forces out into the Atlantic, every endeavour must be made to render it unpleasant for the British naval forces to stay in the Orkneys base, which represents a very severe flank threat to the Shetlands-Norway area.

Naval Staff regrets that we did not succeed in using the aerial mine on Scapa at the same time as the bombing attack. This might possibly have given rise to further great successes.11

However, within days B-Dienst reports of Royal Navy capital ships putting to sea from Scapa Flow, coupled with an address to the House of Commons by Chamberlain in which he described the raid as a failure, with only one warship damaged, gave rise to serious doubts at SKL about the actual results claimed by the Luftwaffe. Again they pressed Göring for permission to lay mines in Scapa Flow using the Küstenflieger, but were rebuffed once more. Instead, Heinkel He 111H-4s of ‘Stein’ Staffel made ready to undertake minelaying missions against the Orkneys, but were prevented by increasingly bad weather. The Kriegsmarine chafed at their enforced inactivity while Britain came closer to effectively countering the threat of magnetic mines permanently. With U-boat and surface forces tied down by preparations for Operation Weserübung, the Küstenflieger were considered the only offensive naval units available now that ice had begun to clear from the seaplane bases sufficiently for regularly scheduled operations to resume.

The mixed Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine personnel of the Bordfliegerstaffel operating shipboard aircraft. (James Payne)

The base at Hörnum occupied by Küstenfliegergruppe 406 and 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 became the target of a retaliatory raid by Bomber Command on the night of 19/20 March, though it was not the first attention given to the Sylt Island airfields by the RAF. During December 1939 Bomber Command had experimented with maintaining a standing patrol of Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys over the German seaplane bases during the hours of darkness, with the object of interfering with Küstenflieger minelaying. Bombs had been dropped on both Hörnum and Borkum, targeting lights sighted on the water which the British believed were connected with the launching and landing of seaplanes. On 14 December five bombs were dropped on seaplanes near Rantum, and six nights later six bombs were dropped along lights in Westerland Bay, Sylt, special care being taken to avoid hitting land. However, the first full-scale raid against the base itself was ordered by the British government, who chose the remote Hörnum seaplane station on the southern end of Sylt owing to the lack of civilian dwellings in the vicinity. The anchorage used by the seaplanes was hardly ideal. It was windswept and exposed, experienced large tidal variation and frequently rough seas, and the pack ice that had formed in December was only just releasing its grip on the three jetties and single slipway. Nonetheless, its strategic location made it invaluable to the Küstenflieger, and the British bombing raid was the largest undertaken thus far, and the first specifically against a German land target. Bomber Command’s 4 Group sent eight aircraft from 10 Sqn, seven from 51 Sqn, seven from 77 Sqn and eight from 102 Sqn, while 5 Group despatched twenty Handley Page Hampdens. Three aircraft were forced to turn back with technical trouble and another was unable to locate the target, but the remainder bombed on target. The first aircraft reached Sylt at 2000hrs, beginning the raid that continued at intervals over the following six hours. In total, the British dropped forty 500lb bombs, eighty-four 250lb bombs and 1,260 incendiaries.

A single 51 Sqn Whitley avoided attack by an Ar 196 floatplane belonging to Wilhelmshaven’s 1./BFl.Gr. 196, but was subsequently damaged by the heavy German flak and its tail gunner was wounded.

RAF reconnaissance photograph of Hörnum seaplane base, taken in preparation for the Bomber Command raid of the night 19-20 March 1940.

A second Whitley of the same squadron was caught by searchlights immediately after dropping its bomb load, and successfully shot down by the gunners below. In flames, the aircraft staggered onwards, heading north to the Danish island of Rømø, where it turned out to sea and finally, at 2335hrs, crashed and exploded in the tidal area north of Morsum, Sylt, killing all five crewmen. Despite the RAF’s efforts, little serious damage was suffered at Hörnum, though the base’s infirmary took a direct hit. Numerous parked Küstenflieger aircraft sustained some measure of splinter damage, but all were fully repaired within fortyeight hours, the Naval Staff attributing the lack of British success more to ‘extremely good fortune’ than the effectiveness of flak and fighter defence. The British bombing had been accurate, though the calibre of bombs themselves was poor and insufficient to cause significant damage.

Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps maintained its pressure on merchant shipping for the remainder of March, even two aircraft from the specialised pathfinder unit KG 100 flying to attack shipping in the Thames and Scheldte estuaries, but with no reported success. By their reckoning, KG 26 Heinkels had made approximately 200 attacks on enemy ships within the North Sea, accruing a claimed total of forty-six vessels sunk, amounting to 70,000BRT of merchant shipping. Alongside a further seventy-six ships claimed as damaged, the total was considered ample return for the operational Luftwaffe’s maritime bomber arm. On 6 April 1940 KG 26 Kommodore Oberst. Robert Fuchs was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his Geschwader leadership, the first such award granted to a member of the Luftwaffe’s bomber arm.

During February the Heinkel He 111Js of Küstenfliegergruppe 806 began armed reconnaissance missions over the North Sea, concentrating both on the Skagerrak and along the British east coast. Aircraft of 3./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 transferred to the grass runway of Uetersen Airfield in Schleswig-Holstein, twenty-one kilometres north-west of Hamburg, to provide easier access to its main operational area. During February a flight of seven aircraft on an armed reconnaissance had an inconclusive clash with Blenheims sent to intercept them off the English east coast, but not until 20 March was the first Küstenflieger He 111 brought down as a result of enemy action.

On that day Lt.z.S. Helmut Ostermann’s aircraft, M7+EL, engaged fishing boats sighted off the Dutch coast, which promptly returned fire with anti-aircraft weapons and damaged the Heinkel’s engines. Ostermann and gunner Obfw. Alfred Hubrich were both wounded, and as the bomber lost height its pilot, Fw. Hermann Kasch, had no alternative but to ditch. Distancing the stricken bomber from the fishing vessels, Kasch brought the Heinkel down off the Dutch coast north-west of Waddeneilanden, from where the crew were rescued by Dutch cutter Vier Gebroeders. Taken ashore at Ijmuiden, they were briefly interned until repatriated to Germany on 22 March, classified as shipwrecked mariners.

Engine failure following a fire caused the loss of another of the Gruppe’s Heinkels on 3 April, when Fw. Heinrich Baasch was forced to ditch off Hatter Rev, deep within the Kattegat, during a routine reconnaissance mission. All four crew, led by Oblt.z.S. Werner Beck, abandoned the aircraft in a rubber dinghy, initially refusing assistance from Danish fishing boats in the hope that they would come ashore in Germany. However, the prevailing current took their small dinghy to the eastern side of Samsø Island near Lillballe, where they were subsequently arrested by Danish police and interned for what amounted to only six days.

While Geisler’s Fliegerkorps carried the weight of winter attacks on enemy shipping, work had been completed during March 1940 on technical improvements to the LT F5 torpedo, the upgraded model being designated the LT F5a. These included a major alteration to the rudder, which would finally allow the He 115 to become an operational torpedo carrier, theoretically replacing the outdated He 59. However, the torpedo’s performance remained far from ideal, as the He 115 had to fly as slow and low as possible to stand any chance of a successful launch, despite the maximum launch speed having been increased from the original 75 knots to 140 knots, and drop height from 20 to 50m. Hitler’s restriction on production was lifted, and by the end of March torpedo stocks had risen to 135 modified F5a torpedoes. The interservice bickering and lack of co-operation between the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe is no better demonstrated than by the lack of technical development of this potentially mainstay weapon. The Seeluftstreitkräfte had jealously guarded the results of its original pre-war weapons trials, and the Luftwaffe had provided no assistance in the furnishing of torpedo-launching equipment. Pointless brinkmanship over authority of the naval air arm robbed German maritime aviation of one of its major weapons. The solution was co-operation and compromise, towards which neither service appeared willing to work, and German crews continued to fight with substandard weaponry. Harlinghausen, a veteran of Spanish Civil War torpedo operations and fully aware of the weapon’s potential in his role as X.Fliegerkorps Chief of Staff, was an advocate of establishing a unified aerial torpedo development office, but this single ambition was not actually achieved until 1942.

While the war with Britain at and over the sea had continued unabated since September 1939, the western front facing France had remained static as the ‘Phoney War’ dragged into its eighth month. Yet, as early as 27 September 1939, Adolf Hitler had summoned his military chiefs to the Reich Chancellery and ordered plans to be prepared for the invasion of The Netherlands, Belgium and France to be launched during October. Designed as a single massive blow to the west before Great Britain could fully mobilise, Hitler’s demand was beyond the capability of the Wehrmacht, which was heavily engaged in Poland. Subsequent operational delays finally forced postponement until 1940 of what had become a planned two-part operation; the initial attack against the Low Countries and north-eastern France, known as ‘Fall Gelb’ and the subsequent exploiting drive into the French mainland, ‘Fall Rot’.

While the difficult process of planning this ambitious campaign was still under way, fears of a likely Allied occupation of Norway began to mount in Berlin. Hitler was worried that such an attack by the Allies would halt the crucial import of raw materials, particularly iron ore from mines in northern Sweden, routed to Germany through Narvik and via seaborne traffic that trailed along the neutral Norwegian coast. Raeder fully endorsed Hitler’s point of view, and was convinced that Great Britain would indeed attempt to sever this Scandinavian supply chain, an occupation of Norway also effectively barring Kriegsmarine access to the Atlantic and hindering naval operations within the North Sea. Norway had already begun to display a marked anti-German posture which was heightened by the Soviet Union’s war of aggression against Finland, Stalin’s and Hitler’s representatives having signed the Soviet-German non-aggression pact during August 1939. Raeder firmly believed that political and military pressure from a combination of the Allies and Norway could be applied to Sweden, finally choking mercantile trade to Germany, and possibly even forcing Sweden into the war on the side of the Allied powers. However, Vizeadmiral Otto Schniewind, Chief of Staff at SKL, and his Chief of the Operations Division, Vizeadmiral Kurt Fricke, believed it improbable that Great Britain was planning or even capable of such an operation. Instead they believed a German occupation of Norway to be extremely risky, both strategically and economically. Even if their assessment of Allied capabilities was proved wrong, they reasoned that any British occupation of Norway would probably bring them into opposition with the Soviet Union and result in legitimate German countermeasures that could extend German operational bases to Denmark and Sweden. Furthermore, a German seizure of Norway could remove the country’s neutral territorial waters and its protection of iron-ore shipments that were permitted, by agreement, to use such sea space as a transit route in safety.

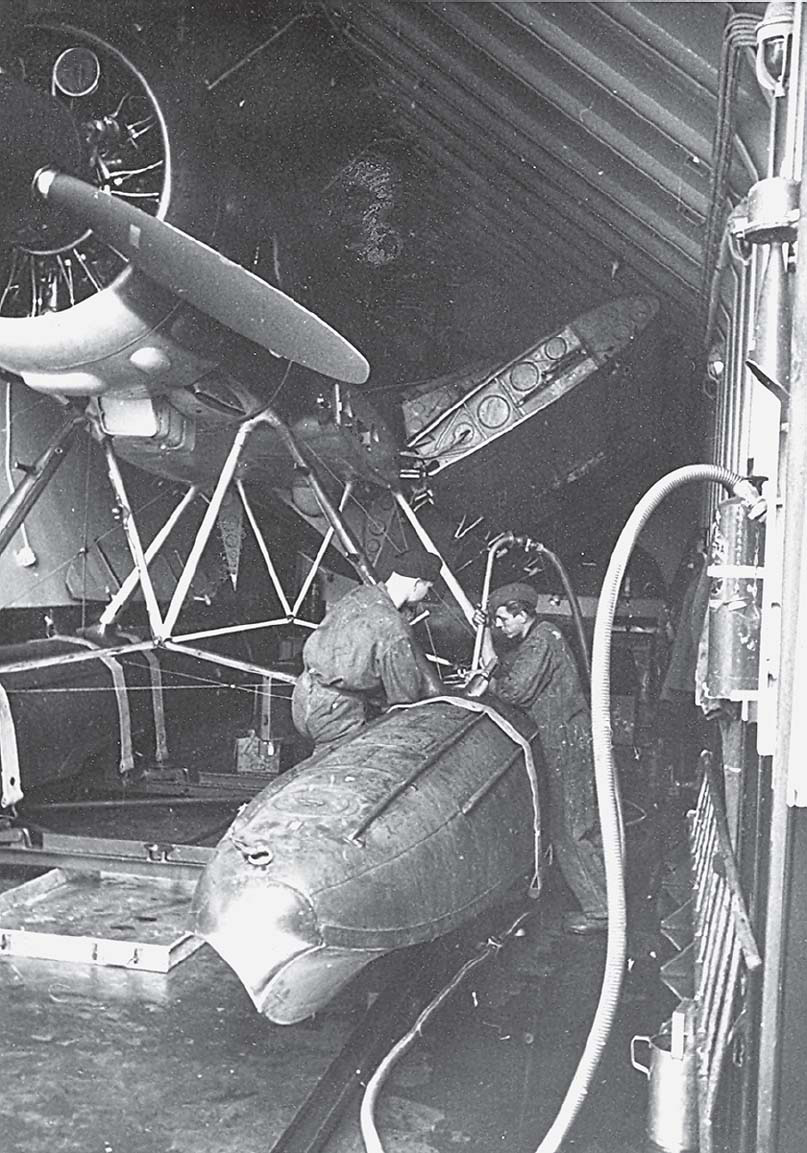

An Arado Ar 196 stowed away with wings folded within its hangar aboard the battleship Tirpitz. (James Payne)

The point of decision came during February 1940, when the Royal Navy ignored Norwegian neutrality and attacked the German auxiliary Altmark, which had moored inside Norwegian territorial waters, and rescued 299 captive British sailors. Hitler correctly believed that the British harboured as much ambivalence toward Norwegian neutrality as he himself did, and subsequently ordered an invasion of Denmark and Norway to take precedence over the invasion of France and the Low Countries. Generaloberst der Infanterie Nikolaus von Falkenhorst was charged with creating the plan and given supreme command of the operation, and on 1 March 1940 the SKL recorded detailed instructions from Hitler on the method by which Norway was to be taken; the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe to ‘bear the weight of the first operation’. The invasion, codenamed Weserübung, was confirmed; Wesertag being set for 9 April 1940.

In this instance, Raeder’s assessment of Allied intentions towards Norway was correct. The Allies had formed plans to neutralise Norway and thus German use of its sea lanes under the guise of an expeditionary force sent to aid Finland in their battle against the Soviets. This land force would reach Finland only after disembarkation in Norway and transit through Sweden, once the relevant permissions had been secured. By landing in Narvik, the all-important Swedish Gällivore iron-ore mines were to be occupied, the stated rationale for such a move being the maintenance of Allied lines of communication to the expeditionary force in Finland.

The small Junkers W 34 was used in both training and combat roles by the Küstenfliegergruppe during the early weeks of war, before it was relegated to training and transport. This particular aircraft crashed in fog in The Netherlands in 1941. (James Payne)

While planning continued, British troops began to be gathered in Scotland while French transport ships assembled in Brest and Cherbourg. However, Sweden refused the Allied application for transit rights to Finland on 12 March, and Finland’s Scandinavian neighbours urged the acceptance of new Soviet armistice terms to end the costly winter war. Bowing to pressure, Finland subsequently sued for peace with the Soviet Union on 13 March, and the pretence upon which the original Allied plan hinged was gone, and its form abandoned. Instead, British and French ships were ordered to begin minelaying along the Norwegian coast, forcing German shipping to sail further offshore and outside the safety of neutral waters, where they could be attacked by the Royal Navy. This was in direct contravention of an agreement signed between Great Britain and Norway on 11 March 1940, by which exports to Germany, even of contraband, were permitted, provided they did not exceed the levels of 1938 trade. Following the successful sowing of minefields, ‘Operation R4’ would then see the landing of the 18,000 British, French and Polish troops on Norwegian soil (those that had already been earmarked for Finland) in response to the predicted German reaction to the Allied infringement upon Norwegian neutrality. Disguising their offensive actions as the defence of neutral Norway, the Allied convoys were scheduled to begin sailing on 8 April.

Concurrently, the Kriegsmarine was fully committed to the largely amphibious invasion of Norway, and as Weserübung forces put to sea in preparation for Wesertag, Allied reconnaissance noted the appearance of German ships moving along the Norwegian coast, speculating that they were attempting a breakout into the Atlantic. On 8 April at 0600hrs the British government informed Norway that they were to begin sowing mines within Norwegian territorial waters; four destroyers already having begun mining Vestfjord an hour before the declaration. Troops of the joint Anglo-French ‘Plan R4’ were readied for landing at Stavanger, Trondheim, Bergen and Narvik, and had already embarked aboard their transport ships in preparation. Although Germany was outwardly outraged, in Berlin there was a certain degree of satisfaction with the Allied announcement. The Western Powers had now flagrantly violated Norwegian neutrality, providing a small measure of public justification for the impending German invasion, which could now be camouflaged as a counter-stroke to the Allies’ activities.

Generalleutnant Hans Geisler was placed in command of aerial forces deployed for Weserübung, X.Fliegerkorps remaining the organisational umbrella beneath which all participating aircraft were placed, including the Heinkel He 115s of 1./ and 2./KüFl.Gr. 506 (eight and ten aircraft respectively), with 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 (ten aircraft) attached (3./Kü.Fl. Gr. 506 remaining in Norderney under command of Küstenfliegergruppe 106). At the peak of the fighting in Norway, X.Fliegerkorps would muster 710 combat aircraft. Geisler delivered briefings to his subordinate commanders on 6 April, after the first naval troop transports had already sailed from Germany.

The three Küstenflieger Staffeln committed to the first wave of Weserübung under the command of Major Heinrich Minner as Gruppenkommandeur Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 were given patrol sectors that covered the North Sea approaches to south-west Norway. Beginning at 0600hrs, 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 was tasked with covering four separate sectors that covered the entrance to the Skagerrak, stretching from Hanstholm in Denmark to Bergen, and 1./ and 2./KüFl.Gr. 506 covering the North Sea as far west as the Orkneys between Bergen and Trondheim. Furthermore, the first Rotte of two aircraft from 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, led by Staffelkapitän Hptm. Lienhart Martin Wiesand, was instructed to fly immediately to Trondheim upon completion of its patrol and find suitable berthing for the incoming seaplanes. The remainder were directed to Stavanger until Trondheim was reported ready. Minner was mindful of the risk of fuel starvation on such extended patrolling, and included in his written orders of the day the warning that:

Navigational difficulties in finding and reaching a landing site must be kept in mind!!

If fuel shortage forces any planned flight path to be aborted, the western part of each patrol sector is of greater importance than the northern. Any premature flight cancellation is to be reported by radio.12

Minner forbade attacks against sighted submarines and merchant ships, as the large commitment of U-boats and troopships provided ample opportunity for mistaken identity, despite the briefing including clear recognition signals to be displayed by all German vessels during Weserübung.

The Luftwaffe’s role in the invasion plan was crucial; they were responsible for reconnaissance and potential naval interdiction, as well as for the transportation of Luftwaffe paratroopers charged with the capture of important airfields. Once German boots were on Norwegian soil, the Luftwaffe would also be responsible for the lion’s share of the major supply operation required by the invading ground forces.

For their part, the Küstenflieger forces not directly involved in the opening of the attack on Norway were primarily charged with reconnaissance and ASW missions over the North Sea and Skagerrak. The logistical difficulties of ground operations along Norway’s rugged coastline also called for the formation of a special seaplane transport Geschwader for Weserübung. Named Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 108 (‘Combat Group for Special Purposes’, or, KG.z.b.V. 108) a single example of the newly operational BV 138A and a small number of Dornier Do 24 flying boats were incorporated into the formation, which consisted mainly of Ju 52(M) floatplanes and He 59s that had been transferred from Norderney’s 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 which handed its elderly Heinkels over as it began converting to the He 115.13 The invasion of Norway also marked the combat debut of Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condors of Hptm. Edgar Petersen’s Fernaufklärungsstaffel (longdistance reconnaissance squadron), soon redesignated 1./KG 40 and in action from 10 April onwards, eight Condors also being brought into service as transports with 4./KG.z.b.V. 107 and 2./KG.z.b.V. 108.

Two days before the invasion began, Küstenfliegergruppe 406 mounted eighteen separate Do 18 long-range reconnaissance missions to the area between the Pentland Firth and Shetland Islands, to discern whether there had been any Royal Navy response to the invasion fleet setting sail from German waters. The British had become increasingly alarmed at the activity reported by its aerial reconnaissances, not only at sea, but also on land as large columns of heavy traffic were detected moving at night with unshaded headlamps along the autobahn that stretched between Hamburg and Lübeck. Desultory bombing attacks were made on the streams of traffic, with little real success. However, at sea, the opposing naval forces had already begun to blunder into one another in poor weather conditions. In rough seas and thick fog. On 8 April the Polish submarine Orzel sank the 5,261-ton German troopship SS Rio de Janeiro of 1.Seetransportstaffel (carrying 313 Luftwaffe troops and flak weapons bound for Bergen), and noted a large number of uniformed soldiers among the wreckage. Norwegian fishing boats and a destroyer came to the surviving Germans’ aid, also noting a startling number of troops, and the Reuters News Agency immediately reported the sinking of a ‘German troopship’ near Kristiansand. South of Oslo, HMS Trident sighted a ‘large laden tanker steaming westward outside territorial waters’. It was the naval tanker Stedingen, carrying Luftwaffe fuel for future operations after the expected capture of Stavanger Airfield, which was the target of a German parachute landing on Wesertag. The tanker’s Master, Kapitän Schäfer, turned to starboard and ran for Norwegian waters when Trident surfaced to fire a warning shot. Two live rounds followed, and the German crew scuttled their ship and abandoned it, Schäfer being taken prisoner as a single torpedo finished off Stedingen. Weserübung was no longer shielded by secrecy.

The unsuccessful Heinkel He 114 floatplane, soon replaced by the far superior Arado Ar 196.

Late on eve of the invasion, Ar 196A-2 6W+BN from the Admiral Hipper, bound for Trondheim and commanded by Oblt.z.S. Werner Tacham and flown by Lt.z.S. Johannes Polzin, inadvertently landed in Norwegian territorial waters near Lyngstad, where the aircraft was seized by the Norwegian torpedo boat Sild and towed into harbour. Both crewmen were interned, though they were subsequently freed by advancing German forces during May. The captured aircraft was to be flown to Britain for examination after the invasion had begun, but was crashed en route. This was not the sole loss to Bordfliegerkommando 196 during Weserübung. Two aircraft aboard the heavy cruiser Blücher were destroyed when the ship was shelled by the 28cm Norwegian guns of Oscarsborg Fortress as she attempted to pass through Drøbak Sound to attack Oslo during early morning darkness on 9 April. Two hits were instantly scored on the ship’s port side, the first hitting the battle station of the anti-aircraft guns’ commander, the second exploding near the aircraft hangar, killing all four of the Luftwaffe technical crew and one of the pilots. Both aircraft were set aflame, one sitting ready on the catapult and the other within its hangar. Although the ship returned fire, the damage had been done. The flames spread, causing sympathetic explosions of stored ammunition and equipment that eventually ruptured several bulkheads in the engine rooms and ignited the ship’s fuel stores. Blücher slowly capsized as the crew and embarked troops for the Oslo assault abandoned ship. The single Arado carried aboard the cruiser Karlsruhe was also destroyed, heavily damaged by a torpedo from HMS Truant that disabled the ship as she sailed from Kristiansand after successfully landing troops following the surrender of the Norwegian garrison. All of the aircraft’s complement were successfully evacuated before the cruiser was scuttled by two torpedoes fired from the accompanying torpedo boat Greif.

A Do 18 of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 was also among the first casualties suffered by the Küstenflieger. Twelve RAF Hampden bombers were despatched during the morning on 9 April to attack German forces at Bergen, but were recalled on account of poor weather conditions. That same afternoon the twelve Hampdens, accompanied by twelve Vickers Wellingtons of 9 Sqn, repeated the attempt, and at dusk attacked the cruisers Königsberg and Köln in Bergen Harbour. Claiming a direct hit and several near misses, the British aircraft turned for home, when Sqn Ldr George Peacock took his Wellington for a second pass over the target area, despite heavy anti-aircraft fire. As he did so, his front gunner, Sgt A.K. Griffiths, opened fire at Lt.z.S. Wolfgang Cohrs’ Do 18, K6+HL, returning from a North Sea patrol, which was hit and shot down in flames. Cohrs’, pilot Oblt. Heinrich de Vlieger, Uffz. Hanz Liesner and Fw. Helmut Suhr all died in the crash.14

Although the cruiser Königsberg had suffered no damage in Peacock’s raid, the following day she was hit and holed by dive-bombing Fleet Air Arm Skuas. Within three hours she had capsized and sunk, her Ar 196A‑2, T3+CH, being carried with her to the bottom. The aircraft’s crew and technicians were taken ashore, and fought as infantry for ten days before they were transferred back to Wilhelmshaven, pilot Uffz. Josef Kampfle being wounded during fighting at the seaplane base in Flatøy.15

At 1030hrs on Wesertag German reconnaissance aircraft sighted the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet west of Bergen, under the command of Admiral Charles Forbes aboard his flagship, HMS Rodney. In anticipation of major British fleet movements, Geisler had kept KG 26 and KG 30 aircraft in readiness for potential interception and, after briskly ordering them into action, forty-one He 111s and forty-seven Ju 88s attacked the Royal Navy capital ships over a period of three hours. The battleship HMS Rodney was hit by an SC500 bomb, which smashed through the upper deck aft of the funnel but did not explode and exited sideways after bouncing off the armoured deck. HMS Glasgow and Southampton suffered minor damage from near misses, one man being killed and four injured aboard the former. The Staffelkapitän of 3./ KG 30, Hptm. Arved Crüger, incorrectly claimed a direct hit on either Southampton or Galatea. The destroyer HMS Gurkha was, however, sunk after leaving the protective umbrella of fire of the other ships to obtain a more advantageous firing position. She was last seen by the attacking aircraft lying stationary and wreathed in smoke, with a severe list to port. Sixteen crewmen were killed before she went down, most of the crew being rescued by HMS Aurora.

The German seizure of Norwegian airfields was of the highest priority, to allow reinforcing troops and equipment to be flown in and also to provide advanced front-line bases for covering aircraft. This objective was largely achieved during the first day. Likewise, the provision of seaplane bases in captured harbours was also realised, aircraft of 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 flying to Trondheim, although the Staffelkapitän of 1./ Ku.Fl.Gr. 506, Hptm. Wiesand, was killed when his He 115 was hit by Norwegian ground fire and made a forced descent in Trondheim Harbour. The remaining aircraft were soon joined by the 2nd Staffel, and immediately began reconnaissance flights covering the North Sea area between Bergen and the Orkney Islands, co-ordinated by Geisler’s staff at X.Fliegerkorps. However, fuel was critically short, the SKL reporting that ‘every aspect of the supply question [was] difficult’. Rail transport to Trondheim from the supply head established in captured Oslo was impossible, and the seaplanes faced short-term grounding unless fuel could be provided.

In Stavanger, which had also been swiftly conquered, 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 arrived late on the first day to also begin operations. A single He 115 was shot down while en route over Trondheim, alighting and being abandoned by its crew before sinking in flames. Ships had arrived in harbour carrying sufficient fuel for four hours’ flying time for the seaplanes of Küstenfliegergruppe 506. The RAF also mounted an attack by two Blenheims on Stavanger Aerodrome and the assembly of seaplanes within the harbour, machine-gunning the aircraft and setting a petrol pump on fire, though causing no severe damage.

It was in Narvik, the most northerly German landing zone, that Allied forces mounted their strongest counterattacks. Although the Wehrmacht had captured the vital ore harbour on the first day, by 13 April all eight supporting Kriegsmarine destroyers and the ammunition ship Rauenfels had been sunk by the Royal Navy. Under increasing pressure from Norwegian and Allied forces, General Eduard Dietl, commander of the 3.Gebirgsdivision and all Narvik forces, was forced to abandon the town and retreat into the hills. Dietl’s forces required fresh supplies of heavy weapons and ammunition if they were to stand any chance of success, and the five long-range Dornier Do 26 reconnaissance aircraft of the Transozeanstaffel were taken off maritime missions and incorporated into 9./KG.z.b.V 108 to operate as transport for heavy material and reinforcements that could not be dropped by parachute.16 Wilhelm Küppers, the radio operator on Do 26V-2 P5+BH, recalled:

During the Norwegian campaign we flew an almost constant round of sorties bringing in anti-tank guns, munitions, mines and mountain troops for Narvik. These flights were combined with reconnaissance along the Norwegian coast. The more perilous moments of any such sortie were the landings on the narrow fjords around Narvik and the subsequent takeoffs. We skirted along neutral Swedish airspace to avoid anti-aircraft fire before diving down almost vertically — almost helicopter-like — for the surface of the water with our engines throttled back. The aircraft had to be rapidly unloaded, but it was amazing what could be achieved with the threat of death so close; we expected naval or artillery fire to come crashing down around us at any moment. Two tons of equipment could be off-loaded under such circumstances — with much sweat and cursing — in under twenty minutes. Take-offs were just as ‘suicidal’, especially in the narrow Beisfjord with its high cliffs. Taxiing out into the middle of the fjord was often done under fire from British ships. Our take-off runs had to be finely judged in order to avoid the cliffs. Engines were run up to full power and we were lucky if we managed to pass more than ten metres over these obstacles. Each successful take-off under such circumstances represented a considerable feat of airmanship for such a large and heavy seaplane weighing up to twenty tons.17

Dietl’s men also desperately needed combat air support, and four He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 flew from Stavanger on 12 April. The aircraft sighted the battleship HMS Warspite, but were driven away by heavy flak, and an attempted attack on the destroyer HMS Ivanhoe was also unsuccessful. With the harbour still in German hands at that point, the aircraft spent the hours of darkness moored, refuelled and ready for the return flight during the following day. However, as they passed over Vestfjord, He 115 M2+EH was shot down by Royal Navy ships, the aircraft commander, Lt.z.S. Joachim Vogler, being taken prisoner and his three crewmen lost.

Interestingly, the Küstenflieger also faced the He 115 in combat, as the Norwegian Ministry of Defence had ordered six He 115Ns for the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service (RNoNAS) on 28 August 1939. Six more had been ordered in December 1939, but delivery was forestalled by Weserübung. The six already in service were spread along the coast, from the naval air stations at Sola and Flatøy in the south to the one at Skattøra Naval Air Station outside Tromsø in the north. At the beginning of the German invasion the single Norwegian He 115 at the seaplane base at Hafrsfjord near Stavanger (numbered F60) was captured by the Germans, but in return two Luftwaffe He 115s were seized soon thereafter by Norwegian forces. One machine from 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 was captured by police officers at Brønnøysund, Nordland, on 12 April, and aircraft M2+FH of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 was taken by an improvised militia unit of Norwegian riflemen at Ørnes in Glomfjord, Nordland, after the aircraft made a forced descent owing to fuel starvation.18 Numbered F62 and F64 respectively and manned by Norwegian aircrews, and they flew several missions against the German invaders. During June F64 successfully flew to Britain, but F62 was recovered by German forces, unserviceable and abandoned at Skattøra after Norwegian evacuation, and later repaired and returned to Luftwaffe service.

With the Luftwaffe wresting local air superiority form the Allies and posing a direct threat to Allied troop landings, the Admiralty ordered cruiser HMS Suffolk, escorted by four destroyers, to proceed towards Skudesnesfjorden and shell Stavanger Airfield. The raid was to be supported by two air strikes; twelve Wellingtons to bomb the airfield before dawn to sow disruption and also illuminate the target area with flames, and a mid-day attack by a dozen Blenheims to suppress potential enemy retaliation. Code-named Operation Duck, the initial Wellington raid never took place, as most of the bombers failed to locate the target in bad weather, while the two that did failed to bomb after observing only damaged hangars and no aircraft. Nevertheless, the surface force met as planned with the submarine HMS Seal, which had been posted as a navigational beacon to the firing area, and Suffolk launched one of its two Supermarine Walrus aircraft to assist in target location.

We approached the Norwegian coast in the dark . . . The normal catapult officer was sick and the chap who was put in charge of the catapult had never done it before, and I thought he was a blinking idiot anyway. We were the first aircraft off and were revving up on the [catapult] and we gave the signal to launch. The ship rolled so that the catapult pointed down to the sea and he dropped the flag and we were fired off straight into the sea . . . it stove in the bottom of the hull and wiped the two wingtip floats off, but we staggered into the air. The other aircraft had a better launch.

We couldn’t establish radio communication with the ship . . . they could hear us, but we couldn’t hear them. Anyway, we were passing through the magnetic bearing of the airfield, it was beautiful clear weather and we could see one aircraft taking off and we were hoping for the best. Then the ship opened fire . . . they fired armour-piercing shells and were hoping to damage the runways. And I looked through my binoculars and I couldn’t see a thing. I could see the airfield but couldn’t see a shot falling anywhere.19

Two Hudson bombers had also been despatched for spotting purposes, one turning back with mechanical problems and the second being plagued by communications difficulties and unable to make radio contact with the cruiser. The pilot did, however, drop his bomb load of incendiaries on the airfield, destroying a Ju 52 of Stab/KG 30 and providing a small conflagration for targeting purposes. With dawn edging nearer, HMS Suffolk opened fire at 0515hrs on 17 April, and over the next forty-nine minutes 217 8in shells were fired towards that airfield at a range of 20,000 yards.

A Junkers Ju 88 of I./KG 30 following a forced landing. The nose insignia displays the plunging eagle of the Geschwader, while the umbrella in crosshairs on the starboard engine indicates the aircraft is from I Gruppe.

Despite the Hudson crew’s best efforts, the shells missed Stavanger-Sola Airfield, overshooting and instead hitting the Sola seaplane base just to the north. The operational readiness of the Küstenflieger aircraft thus far moved to Stavanger was relatively slight, owing to a severe shortage of ground staff and the great demands made both on the available personnel and material. While aircraft attacks had thus far caused little extra disruption, Suffolk’s shellfire destroyed buildings (including the commander’s house), a truck, two fuel stores, four He 115s of 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and three He 59s that had been taken on to the strength of KGr.z.b.V. 108 as transport aircraft. All light and power installations were also disabled, hampering initial German damage control efforts.

However, the British ships were not to escape without retaliation, and reconnaissance aircraft scoured the area for the attackers, a Do 18 of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 sighting HMS Suffolk as the cruiser was west of Haugesund and driving hard for Britain. Geisler’s bombers were swiftly readied and ten He 111s from I./KG 26 spearheaded an attack, eight focussing on Suffolk and the remaining pair attempting to bomb the escorting destroyers. The only damage caused was to HMS Kipling, from two near-misses that cracked engine mounts and disabled the aft torpedoes. Two torpedo-carrying He 115s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 also attempted an attack, but weather conditions prevented them from launching their weapons successfully. Dornier Do 18s maintained contact with the speeding British ships as weather gradually began to clear, until the warships sailed under a virtually cloudless sky, the sun rising to allow excellent visibility to the west in the North Sea.

Fighter cover for the retreating ships had been arranged with Coastal Command, though only two of three planned Blenheims took off, and were soon sent on a wild goose chase against imaginary German destroyers. One of the Blenheims reached Bergen and made a low-level strafing run against He 59D seaplanes of KGr.z.b.V. 108, before being attacked and driven away by a defending Bf 110. Meanwhile, the planned Blenheim noon attack on Stavanger Airfield did take place, destroying a Bf 110C of 1./ZG 76 and a single Ju 52 and killing two Luftwaffe ground crew, though it failed to have any detrimental effect on Luftwaffe retaliation against the ships of Operation Duck as KG 30 added its weight to the attack.