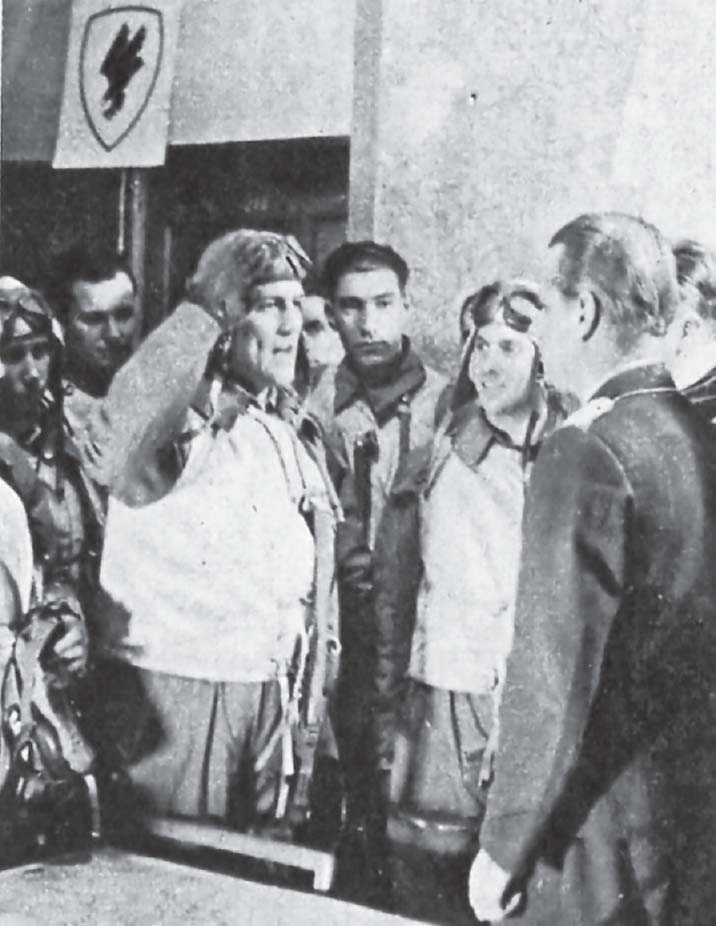

Major Hermann Busch, former commander of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 before taking command of I/KG 26.

Major Hermann Busch, former commander of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 before taking command of I/KG 26.

For the operational Luftwaffe, the strength of their dedicated maritime units at the end of April 1940 amounted to 9.Fliegerdivision and certain elements of X.Fliegerkorps:

9. Fliegerdivision, General der Flieger Joachim Coeler, (Jever)

KG 4, Obst. Martin Fiebig (Fassberg), He 111P

I./KG 4 (Copenhagen-Kastrup), Obstlt. Hans-Joachim Rath, He 111H-4

II./KG 4 (Oslo), Major Dietrich Freiherr von Massenbach, He 111P

III./KG 4 (Lüneberg), Major Erich Bloedorn, He 111P, Ju 88A-1

I./KG 40 (Copenhagen/Kastrup), Major Edgar Petersen, Fw 200C-1

KGr. 126 (Marx), Hptm. Gerd Stein, He 111H-4 3.(F)/Aufklärungsgruppe 122, (Stavanger), Do 17, Bf 110

Luftflotte 5 (Oslo) General Hans-Jürgen Stumpff

X.Fliegerkorps, Generalleutnant Hans Geisler

KG 26 ‘Löwen’ (Trondheim Vaernes), Generalmajor Robert Fuchs, He 111H

I./KG 26 (Trondheim Vaernes), Major Hermann Busch, He 111H

II./KG 26 (Trondheim Vaernes), Major Martin Vetter, He 111H

III./KG 26 (Trondheim Vaernes), Major Viktor von Lossberg, He 111H

KG 30 ‘Adler’ (Westerland), Obstlt. Walter Loebel, Ju 88A

I./KG 30 (Jever), Hptm. Fritz Doench, Ju 88 A

II./KG 30 (Westerland), Hptm. Claus Hinkelbein, Ju 88 A

III./KG 30 (Marx), Hptm. Gerhard Kollewe, Ju 88 A

Ultimately, the outcome of the struggle for Narvik was decided nearly 2,000 kilometres to the south-west. From 5 May, following the Allied evacuation of Namsos, additional air units that had been subordinated to X.Fliegerkorps were withdrawn to Germany alongside elements of KG 30, in preparation for the planned attack in the west. During the night of 9 May the codeword Danzig was issued by OKW in Berlin to all subordinate major commands, signifying the opening of Hitler’s cherished assault on the Low Countries and France, beginning at 0535hrs the following morning. During the night, seven aircraft of 9.Fliegerdivision dropped mines off the Dutch and Belgian coasts: near den Helder, Ijmuiden, Hook of Holland, in the Scheldt, and off Flushing, Zeebrugge and Ostend. Further minelaying operations were also undertaken over successive nights, including the He 115s provided by Küstenfliegergruppe 106, by which time land forces had made significant headway in The Netherlands and Belgium. Meanwhile, both KG 4 and KG 30 attacked shipping off the Belgian and Dutch coasts, claiming notable success against destroyers engaged in Operation Ordnance, the evacuation of Dutch government staff and monarchy, and the small British force that had landed in the Hook of Holland on demolition missions.

A pilot of KG 30 reports to Geschwader Kommodore Oberstleutnant Loebel in a photograph staged for the benefit of a Propaganda Company photographer.

Twelve He 59s allocated to 3./KGr.z.b.V. 108 for Unternehmen Weserübung took part in the invasion of The Netherlands as part of ‘Sonderstaffel Schwilden’; a provisional seaplane unit formed for the purpose and placed under the command of Hptm. Horst Schwilden, Staffelkapitän of 3./KG 26. Schwilden had taken part in the Spanish Civil War as an Oberleutnant pilot with AS/88; he was no stranger to the operation of the large Heinkel floatplanes. The Sonderstaffel’s task was the securing of key bridges in Rotterdam on the morning of the invasion, crucial for the advance of German armour. It carried 120 men of 11./Infanterie Regiment 16, comprising platoons commanded by Lts. Gottbehöde and Fortmann, plus twenty-two engineers from the 2./ Pionier Bataillon 22. The assembled infantry and engineer company was commanded by Oblt. Hermann-Albert Schrader, and the twelve Heinkels approached the Willems Bridge over the River Maas during the early morning assault, splitting into two separate flights of six aircraft to envelop the target from both east and west. The aircraft alighted on the river virtually unopposed, and the troops were disembarked successfully in rubber dinghies. They secured the Willems Bridge amidst crowds of bewildered civilians, and a nearby railway span and the Leeuwen and Jan-Kuiten Bridges were also captured without loss. Four Heinkels were damaged while manoeuvring within the confined waterway and later completely wrecked while stationary on the river during a brief attack by Dutch gunboats. The remaining Heinkels suffered minor damage while being held in readiness to act as ambulance transports for wounded troops. Following the successful operation, the Sonderstaffel was disbanded.25

The decision to withdraw Allied forces from Narvik was not made until 24 May, and until then the battle continued to rage. Fresh Luftwaffe plans were laid to base long-range Ju 88s in Trondheim, capable of reaching the Arctic battleground and of supporting troops struggling on the ground. The Junkers were to be commanded by Major Harlinghausen, freshly awarded the Knight’s Cross on 4 May while still Chief of Staff to X.Fliegerkorps, and now back on operational flying while also holding the newly established office of Fliegerführer Trondheim. The intention also to use the highly effective but short-range Ju 87 dive-bombers remained dependent on the provision of an airfield between Trondheim and Narvik. Meanwhile, the Kriegsmarine also advocated aerial minelaying with the newly developed TMA mines (moored influence mines designed to be laid by U-boat torpedo tube) near the Stroemen Channel in Rombaken Fjord, to frustrate continued Royal Navy gunnery support provided by destroyers and cruisers. At the time of the proposed minelaying operation there were only eight TMAs in existence, and they would have to be transported by He 59s, which would have to touch down on the water to lay their mines. Staff at X.Fliegerkorps enthusiastically backed the idea, requesting that an additional nine mines be dropped in the narrow Stroeman Channel itself, though the dangerously constricted airspace made this suggestion impossible to accommodate.

On 22 May four He 59s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 departed from Copenhagen, each carrying a single TMA mine. One aircraft, 6I+IH, was forced down near Godøy island, Giske, with engine damage, where it was scuttled and the crew rescued. The remaining three He 59s successfully laid their mines and had returned to Copenhagen by 24 May. Encouraged by this success, a further mission was mounted four days later which deposited five more mines at the narrow entrance to the Tjelsund.

The fighting in Norway involved myriad isolated skirmishes between Wehrmacht and Allied forces, also including aircraft of Seenotflugkommando 2, which highlights the difficult distinction between humanitarian and military service within which the Seenot aircraft operated. As a result of action on 15 May, Oblt. der Reserve Wilhelm Branger was taken prisoner as an enemy combatant by Norwegian troops. Earlier that day, Lt. Willi Meier’s He 111H of III./KG 26 had been forced down with engine trouble near Alstahaug during an anti-shipping attack near Narvik, whereupon local Norwegian militia approached and demanded the crew’s surrender. Following an initial German refusal, the militiamen opened fire on the stranded crew, wounding one and forcing the remainder to surrender. The wounded man was taken to hospital in Sandnessjøen, while the others were transported by fishing boat to a makeshift prisoner-of-war camp. Responding to earlier distress calls made by Meier before his forced landing, Branger’s Seenot Heinkel He 59, D-AKUK, arrived some time later and alighted in the bay, whereupon Branger went ashore to discover the whereabouts of the missing bomber and crew. Branger was told by locals that the crew had been captured and moved, the wounded man and possibly other prisoners being held in the nearby town of Sandnessjøen.

The wreck of the He 111 was plainly visible, and, coming under rifle fire from Norwegian militia guards, Branger decided to lift off and proceed instead to Sandnessjøen to liberate the wounded crewman. Alighting at 1730hrs, Branger and an accompanying Uffz., both now armed, went ashore again, walked to the small local hospital and demanded the release of any wounded Germans being held there. Although the chief physician initially refused to comply, he was subsequently ordered to do so in a telephone conversation with the Norwegian police commissioner at nearby Nesna. Meanwhile, as the luckless Branger was preoccupied with the protracted negotiations, the Norwegian naval trawler HMNoS Honningsvåg arrived in the bay, its captain having been ordered to seize the He 59 and capture its crew. Branger and his companion were taken prisoner by a landing party, but the two remaining Unteroffiziers aboard D-AKUK initially refused to surrender. A warning shot from the trawler settled the matter. Branger and his three crewmen were handed over to the Norwegian police. Although D-AKUK was taken in tow, it proved impossible to move, as it had firmly grounded in a low tide. After sustaining damage to its wings and pontoons during the attempts to pull it free, the aircraft was finally dragged out of Leirfjord and sunk three days later.

Seaplanes continued to transport men and equipment to German forces at Narvik, landing in Rombaksfjord to the east of the town itself. This, combined with Ju 52 parachute drops inland, maintained the fighting efficiency of Dietl’s men. A reinforced infantry battalion making its way from Trondheim to link up with the troops in Narvik was also supplied by regular seaplane rendezvous. On the part of the operational Luftwaffe, the crews of the He 111 bombers were handicapped in their battle against Royal Navy forces because they possessed neither the training nor the specialised bomb sights needed for precision naval strikes, and the number of Ju 88s available for dive bombing and reconnaissance remained low as KG 30 steadily relocated to the Western Front. Overly optimistic Luftwaffe reports constantly cited the severe damaging or sinking of capital ships and even aircraft carriers, but without substance, so much so that Kriegsmarine officers stated on record their extreme scepticism at most success reports filed by the Luftwaffe General Staff. To compound their problems, Hurricane and Spitfire fighters were now based at aerodromes north of Narvik and began to take a heavy toll of the unescorted bombers. However, von Falkenhorst short-sightedly demanded that the Luftwaffe continue to concentrate its efforts at Narvik on ground support, rather than re-establishing the air superiority that would allow successful attacks against both the Royal Navy and Allied troops. Backed by the incoming commander of Luftflotte 5, Stumpff, this misdirection of available air power did little to lessen Dietls’ misery, and despite a small number of reinforcements reaching the battle, German forces were expelled from Narvik on 28 May by fresh British forces that had been successfully landed by ship two miles to the east.

The position of Dietl’s Gebirgsjäger was extremely precarious, and consideration was given to a forced march to nearby Sweden for internment as the staffs of X.Fliegerkorps and Luftflotte 5 wrangled over how best to use their available forces. Amid bitter arguments, the Fliegerkorps’ Chief of Staff, Genmaj. Ulrich Kessler, resigned his command at one point in protest at what he considered the woeful and careless misdirection of his men that had resulted in unnecessarily heavy casualties. However, events on the Western Front had already played their part, and on 24 May the British finally resolved to evacuate their troops from Narvik. In truth, the splitting of Allied land forces between fighting for Trondheim and Narvik had already doomed the Allies to overall failure, British planning being muddled as to its actual strategic objective. Although Narvik and its access to Swedish iron ore mines was the prize, Trondheim was perhaps the key to controlling both north and south with its strategic position at the narrow waist of the country. Vacillating between the two objectives robbed both of success, and between 4 and 8 June the Allied troops in Norway were successfully evacuated by sea in Operation Alphabet.

Part of the British withdrawal was sighted by He 115 S4+EH of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 during a reconnaissance over the rugged coastline around Narvik. Following the initial sighting, a probe northward yielded confirmed contact with the battleship HMS Valiant. However, air support hastily summoned from HMS Ark Royal bounced the Heinkel, and it was shot down east of Bodö by Skuas of 800 Sqn FAA. Its pilot, Fdw. Franz Augustat, managed to shake off the pursuing Skuas, but his aircraft had been hit in the starboard engine, and gunner/ wireless operator Uffz. Willi Schönfelder was wounded in the shoulder after firing only a single burst of return fire. Aircraft commander and observer Lt.z.S. Rembert van Delden bandaged the wounded gunner, and the Heinkel staggered back towards Trondheim. With his compass behaving erratically in the northern latitudes, van Delden used his sextant to plot a course, but after an hour they were forced to ditch in the sea with fuel exhausted. Although the aircraft’s radio equipment had been damaged they were successful in transmitting distress calls before they alighted, whereupon the heavy swell ripped the starboard float clean off its struts. Nonetheless, the Heinkel remained afloat, enabling its crew to abandon it in their rubber dinghy after jettisoning anything of potential intelligence value. The three crewmen were in their dinghy only briefly before another of the Staffel’s He 115s, flown by Oblt. Peterjürgen ‘Pitt’ Midderhoff, an experienced air-sea rescue pilot, arrived on the scene as a result of their hurried radio transmissions. Despite the swell, Midderhoff alighted and recovered the stranded crew, although his aircraft’s propeller blades were badly bent by impact with the choppy water as the Heinkel crashed through the peaks and troughs of wind-driven waves. Despite the damage, Midderhoff was able to take off again, using the swell to help catapult the aircraft upward and, after sinking the abandoned aircraft with gunfire, he successfully returned to Trondheim with the rescued crew.26

The day after Midderhoff’s spectacular rescue of the downed Heinkel crew, 10 June, Norway officially surrendered, and the I./KG 40 Focke-Wulf Fw 200 flown by Oblt. Heinrich Schlosser sank the largest ship lost by the British during Operation Alphabet, the 13,241grt armed boarding vessel HMS Vandyck. Schlosser attacked the ship with bombs off Andenes, as it prepared to assist in the evacuation. Direct hits sent the former cruise liner under, killing one officer and five ratings. The remaining twenty-nine officers and 132 ratings took to their boats and rowed ashore, where German troops captured them.27

KG 26 Kommodore Oberst Robert Fuchs photographed aboard one of his bombers. His award of the Knight’s Cross on 6 April 1940 for Geschwader leadership was the first such decoration granted to a member of the Luftwaffe’s bomber arm. (NARA)

The Küstenflieger were heavily involved in supporting the invasion of Norway through reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols, this He 115 of Küstenfliegergruppe 506 being photographed at Trondheim. (Australian War Memorial)

Although the Norwegian campaign was successful, German losses had been severe, particularly to surface ships of the Kriegsmarine. The crisis confronting Raeder and his staff in the face of such depletion had the knock-on effect of halting construction of the carrier Graf Zeppelin completely. Raeder ordered the worked curtailed. The guns were to be removed for use as coastal defence for Norway, as the carrier’s fire-control system was still incomplete, elements having been supplied to the Soviet Union owing to contractual demands included within the 1939 nonaggression pact. On 6 July 1940 the Graf Zeppelin was towed to the Baltic port of Gotenhafen, beyond the likely range of British bombers, and it became a floating storage space for Kriegsmarine hardwood supplies. Construction of ‘B’ had already been stopped on 19 September 1939, the hull later being dismantled and its components used elsewhere.

Nevertheless, by the time Norway had surrendered the Allied Western Front had collapsed, Belgium and The Netherlands had surrendered, and the Dunkirk evacuation of the shattered remains of the British Expeditionary Force had been completed. Göring’s operational Luftwaffe had been tasked with annihilating the cornered enemy trapped against the Channel coast, but had comprehensively failed, and although British losses of men, equipment and ships were heavy, Britain was not yet defeated.

HMT Lancastria, her hull crowded with survivors, sinking off Saint-Nazaire after being hit by bombers of KG 30. This disaster remains one of the world’s worst in terms of its death toll, never properly ascertained, but estimated to have reached at least 3,050 people, possibly as high as 5,000.

Aircraft of both KG 26 and KG 30 had taken part in the attacks against The Netherlands and France, and on 17 June Ju 88s of II./KG 30, which had moved to a forward base at Le Culot, Belgium, bombed shipping gathered at Saint-Nazaire as part of Operation Aerial, the British evacuation of ground forces nearest the French Atlantic ports. The bombers found the heavily-laden 16,243-ton liner Lancastria, requisitioned by the Admiralty for service as a troopship, anchored off the entrance to Saint-Nazaire’s harbour. The liner’s skipper, Capt Rudolph Sharp, a veteran seaman from Liverpool, was held in high regard both by company and crew, and had previously captained the liners Lusitania, Mauritania and Olympic. He had already taken his ship to Lorient, where he was found superfluous to evacuation requirements and redirected onward to Saint-Nazaire, arriving at 0400hrs on 17 June. HMT Lancastria was anchored in twelve fathoms, barely 22m, at Charpentier Roads, near the harbour’s entrance, the ship’s draught being too great to allow it to enter port. While the Lancastria swung lazily at anchor in the turbid water carrying silt from the mouth of the Loire River, Saint-Nazaire was in a state of bedlam, as retreating Allied troops destroyed their heavy equipment and whatever installations might be valuable to the advancing Wehrmacht. British officers of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), acting as embarkation control, boarded Lancastria to assess the number of troops it could accommodate. Sharp was heard to reply ‘3,000 at a pinch’. By midday Sharp and his crew had embarked an exhausted 5,200 dishevelled soldiers and airmen, as well as many British civilians, some of whom had worked for the Fairey Aviation Company in Belgium and had retreated all the way across France. The British destroyers HMS Highlander and Havelock shuttled between shore and ship throughout the day, until attempts to keep track of the number of evacuees were abandoned completely. Finally, packed beyond capacity, Lancastria received clearance to sail for England, but remained at anchor, Sharp and his officers erroneously believing that U-boats posed the most prominent threat, and opting to await an armed escort.

As the Luftwaffe appeared over Saint-Nazaire, Sharp had the ship’s boats swung out in the event of emergency, and at 1557hrs II./KG 30’s Ju 88s attacked Lancastria. Sharp rushed to the bridge, reaching the wheelhouse as four high-explosive bombs bracketed his ship. Two passed through the deck planking. One detonated inside number two cargo hold, packed with at least 800 RAF men, and the other smashed through number three hold, where it released gallons of heavy fuel oil into the water. A third bomb arced directly down a smokestack and exploded in the engine room, while the last missed by mere metres, its blast sufficient to hole the great liner below the waterline.

Dornier Do 26 aircraft of the Transozeanstaffel were used to ferry men and equipment to the beleaguered garrison at Narvik, temporarily attached to the transport group ‘Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 108’.

The Lancastria sank rapidly by the head, listing initially to port before a sudden intake of water rolled the hull over to starboard. Many were trapped inside after the main internal staircase collapsed, and, with KG 30 bombers continuing to strafe the anchorage, neighbouring vessels could not remain stationary long enough to be effectively useful as rescue ships. The ASDIC trawler HMT Cambridgeshire was the most successful, with over 1,000 survivors dragged aboard. Within fifteen minutes Lancastria had rolled back to port, the stern briefly rising above water before it finally went down.

The exact number of dead has never been established, but it is known that at least 3,050 people were killed, estimates variously rising to 4,500 or 5,000 dead. Even without this revised death toll, the horrifying statistic of people killed during the sinking gave the Lancastria the tragic title of the worst British merchant loss in history. Captain Sharp, who survived the ordeal, stated that there was no panic on board, even up to the final moment as the hull slid beneath the sea. In words taken from his report to the Department of Trade:

A Do 26 of the Transozeanstaffel in Hemnfjorden on 13 May 1940.

The spirit of the men in the water was wonderful, they even managed to sing whilst waiting to be picked up. [But . . .] not everyone who had a lifebelt was saved . . . I should estimate that 2,000 were saved by lifebelts and another 500 in boats and rafts, so that 2,500 people were saved out of a total of about 5,500. I lost 70 of my crew of 330.

The loss of life was so shattering that Prime Minister Winston Churchill forbade the publishing of news of the disaster in the English press, clamping a ‘D-notice’ on it. He felt that the country’s morale could not bear the burden of this terrible event. In his voluminous Second World War history he later wrote:

When this news came to me in the quiet Cabinet Room during the afternoon I forbade its publication, saying: ‘The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today at least’. I had intended to release the news a few days later, but events crowded upon us so black and so quickly that I forgot to lift the ban, and it was some years before the knowledge of this horror became public.

Survivors were forbidden under King’s Regulations to mention the disaster. Those killed were listed as ‘missing in action’, leading to the assumption by most bereaved relatives that they had probably died during the bloody retreat from northern France. However, the story of the sinking could not be contained and, after appearing in the New York Times, it finally broke in English newspapers on Friday 26 July 1940, albeit belatedly and quietly. The official report is still sealed until the year 2040 under the Official Secrets Act.28

By the end of the French campaign several maritime bomber pilots had been awarded the Knight’s Cross for their cumulative service since Operation Weserübung. Oberleutnant Werner Baumbach of 5./KG 30 was so awarded on 8 May for his attack on the French Group Z off Namsos, Oberst. Martin Fiebig, Geschwaderkommodore of KG 4, received his on the same day. The following five all received theirs on 19 June: Maj. Fritz Doench, Gruppenkommandeur of I./KG 30; Hptm. Claus Hinkelbein, Kommandeur II./KG 30; Oblt. Franz Wieting, Staffelkapitän 6./KG 30, ‘for noteworthy success against enemy warships and shipping in the North Sea’; Fw. Willi Schultz, 6./KG 30, ‘for hits on Royal Navy surface units off Norway, including the cruiser HMS Suffolk’; and Hptm. Arved Crüger, awarded for his ‘Staffel leadership during Weserübung, the subsequent anti-shipping campaign against the United Kingdom and the invasion of France’.

The naval air arm played little part in the defeat of the Allies’ western forces, instead continuing minelaying and the harassment of shipping, both military and merchant, in the North Sea. By the middle of June the improvised group commanded by Major Walter Schwarz, Gruppe Schwarz, comprising 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 and 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906, both equipped with Do 18 flying boats, was based at Stavanger-Sola (See), ten kilometres south-west of the town on the shore of Hafs Fjord. Previously used by the Norwegian Naval Air Service, the base had an established infrastructure that the Luftwaffe improved further over their years of occupation. The Dornier Do 17s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, based on the nearby airstrip, also formed part of the Gruppe. This forward base increased the range of reconnaissance missions into the North Atlantic approaches, though the ageing Do 18s showed limitations, both in combat and endurance. During June the seaplane tender Hans Rolshoven was based in Stavanger Harbour as support for Gruppe Schwarz, acting as the general communications hub for all naval aircraft operating along the south-west Norwegian coast by means of its powerful radio gear. Gruppe Schwarz was soon reinforced by the Ar 196s of 1./BFl.Gr. 196 and renamed Küstenfliegergruppe Stavanger on 14 June, after Schwarz had departed for Germany and was replaced by Major Karl Stockmann.

The Norwegian seaplane bases also provided support for shipborne aircraft during June, when the Kriegsmarine mounted Operation Juno, a sortie by the battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four escorting destroyers. Their objective was the disruption of Royal Navy forces supporting Allied troops still engaged in the final weeks of fighting in Narvik. While Juno succeeded in sinking the carrier HMS Glorious, two destroyers, one minesweeper, one troopship and an oil tanker, Scharnhorst suffered heavy damage from a torpedo fired by the destroyer HMS Acasta. Badly holed and with forty-eight men killed, Scharnhorst was hounded by British aircraft as she headed first for Norway for emergency repairs, and then south towards Kiel’s shipyards. The battleship’s Ar 196s were flown in continuous combined reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols, and all German U-boats were instructed to avoid the area through which the battleship would pass. During one such patrol, on 21 June, observer Oblt.z.S. Peter Schrewe and pilot Uffz. Gallinat had taken off from Scharnhorst in Ar 196 T3+BH at 0045hrs, alighting at both Trondheim and Bergen for refuelling and brief rest during their extended and exhausting patrol. At 1645hrs they sighted a diving submarine, and dropped two 50kg bombs, which were recorded as landing only 3m from the conning tower. The vessel’s stern rose clear of the water as the boat dived, leaving a vague smudge of an oil slick behind. Estimated as a 1,000-ton submarine, the single deck gun was visible to Schrewe as it dived, and the boat was considered probably damaged by the attack. The Arado subsequently alighted at Stavanger-Sola, where the starboard float was found to be damaged, requiring brief repairs before the aircraft returned to Scharnhorst. In fact they had attacked Kaptlt. Otto Kretschmer’s U99, which had strayed into the area proscribed for U-boats. It had suffered minor damage on what was its maiden patrol from Germany, bound for the Atlantic, and was forced to return to Wilhelmshaven for repairs.

Nonetheless, the small Arado floatplanes based in Norway proved their worth in anti-submarine patrols during July, when they were largely responsible for the surrender of another British submarine, HMS Shark. At around 2215hrs on 5 July, Ar 196 T3+LH, piloted by Lt.z.S. Gerhard Gottschalk, accompanied by wireless operator/gunner Uffz. Gerhard Manjok, sighted Shark running on the surface, recharging depleted batteries while on patrol thirty-five miles west of Feistein, south-west Norway. The midsummer nights were never completely dark at that latitude, and Gottschalk immediately attacked from astern with bombs and machine-gun fire.

At 2210hrs I dived from 800 metres and released the first bomb from 400 metres . . . The bomb hit amidships, just behind the tower. The submarine vanished, but shortly after, the stern reappeared and I attacked again. The boat vanished before I was in a position to release the bomb, though. Again the stern appeared, and this time I dropped the bomb from 400 metres. It detonated on the starboard side of the tower, three metres off and somewhat aft. The submarine was lifted slightly out of the water, sank quickly and then came back up, stern down and with a severe list. It slowly righted itself, but the stern remained deep in the water. The fore end of the submarine was strafed by cannon and machine-gun fire. Eventually the submarine vanished, leaving a large oil patch.29

The Shark was badly damaged and sinking, stern first. Lieutenant Commander Peter Buckley attempted to control the descent using the port motor, the only one still functioning, but succeeded only in draining the already depleted batteries. With little choice, he ordered all the remaining compressed air to be used to blow main ballast, and arrested the descent at a depth of 91m. The submarine began to rise, out of control, and reached the surface at an ungainly angle, where it came under renewed attack. A second Arado had arrived to continue the battle, and the Shark’s crew manned guns and attempted to fight them off. Aircraft T3+GH, piloted by Lt. Eberhard Stelter with Uffz. Helmut Stamp in the rear seat, also dropped its bombs on the stranded submarine and continued circling and strafing, the aircraft being hit by Lewis-gun fire from Shark’s bridge.

Gottschalk’s aircraft was hit in the starboard wing, causing slight damage and forcing a return to base, where he swiftly exchanged it for another machine and returned to the scene, replacing Stelter, who returned to Stavanger. A third Arado, piloted by Oblt.z.S. Junker, had reached the scene, along with two Bf 109s which made repeated strafing passes. In Stavanger, Do 18 flying boats were fuelled and armed so that they might add their weight to the battle.

Aboard Shark, the situation had become hopeless. The final ascent had spilled battery acid into the bilges, creating chlorine gas, while Petty Officer James Gibson was killed by German gunfire and several men had been wounded by the attacking aircraft, including Buckley, who had been hit in the head and legs.30 Under constant fire and with the Dornier flying boats also arriving, led by Major Karl Stockmann (Gruppenkommandeur Küstenfliegergruppe 406) in M2+FK, Buckley decided to surrender.

Junker noticed the sudden cessation of return fire as the Messerschmitts continued their strafing runs, and also saw men aboard the submarine raising their hands and frantically signalling with lights. To forestall any further attacks he impulsively set his Arado down alongside HMS Shark, though the port float had been seriously holed by Lewis-gun fire and immediately took on water as he brought the aircraft to a halt immediately alongside. Junker and his gunner, Oblt.z.S. Gerhard Schreck, jumped aboard the submarine with pistols drawn, while behind them their aircraft drifted away and capsized. The two Germans surveyed the scene aboard the wrecked conning tower, exchanging some words with the injured Buckley, but were unwilling to go below decks and investigate the situation further. Junker successfully communicated with a Do 18, which landed and retrieved both German airmen as well as Buckley and Sub-Lt Robert Barnes, transporting them to Stavanger.

Behind them, the circling aircraft monitored HMS Shark, the British crew now gathered on deck and awaiting the arrival of four minesweepers, which attempted to take control of the stricken submarine and bring her into harbour. Boxed between M1803 and M1805 and underslung to keep her afloat, the submarine was taken in tow by M1806, but began to sink by the stern after the British crew had been removed. The Germans had failed to prevent a surreptitious scuttling of the boat, the departing British crewmen having left the main ballast tank vents slightly open and disabled all pumps. As the Germans were unable to control the sinking submarine, the tow line was hurriedly cut and HMS Shark went down twenty-five miles west-south-west of Egersund.

The likelihood of the submarine being successfully captured intact was, in fact, virtually nil, regardless of its scuttling. German B-Dienst radio interception had detected HMS Southampton and Coventry of the 18th Cruiser Squadron and four destroyers of the 4th Flotilla being despatched from eastern Scottish bases to reconnoitre the area off Skudesnes as a result of Buckley’s distress calls. While aircraft of Luftflotte 5 prepared an interception strike, the minesweepers were ordered to scuttle Shark and return to port, rather than face certain destruction by superior enemy forces; a measure that proved unnecessary. Coastal Command also joined the search for Shark, but found nothing, while the approaching surface forces experienced frequent air attacks that damaged HMS Fame and forced the search to be abandoned.

While the small and nimble Ar 196s were proving valuable for shortrange coastal missions, the limitations of the Heinkel He 111J had impeded operations by Küstenfliegergruppe 806, and the decision was taken to re-equip the Gruppe with the more reliable and versatile Junkers Ju 88. During June all three Staffeln were relocated to the large training airfield at Uetersen for conversion to the new type, a process completed by 10 July. By this stage the so-called Kanalkampf, the concerted Luftwaffe attacks on English Channel shipping, was beginning, as Göring attempted to lure Fighter Command forces into battle over the water in the overture of what became known as the Battle of Britain. The objective was aerial superiority over Britain, either to force Churchill’s government to sue for peace or as a prelude to potential seaborne invasion, something for which the Wehrmacht was woefully unprepared. The operational Luftwaffe’s maritime units, KG 26 and KG 30, had maintained a degree of activity harassing shipping within the North Sea, KG 26 also mining east-coast harbours, but emphasis was now placed on the bombing of British industry and military centres, and eventually changed to night area-bombing as the Luftwaffe failed to break Fighter Command.31

Luftwaffe pilots and Kriegsmarine observers of the Küstenflieger that had taken part in attacks on British shipping off Norway photographed on 2 June following a press conference for foreign correspondents at Goebbels propaganda Ministry in Berlin. Second from left is renowned Stuka pilot Martin Möbus, while at far left is Leutnant zur See Rolf Thomsen of Küstenfliegergruppe 106. He later found fame as the commander of U1202.

On 15 August the maritime strike aircraft of Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps, still part of Stumpff’s Luftflotte 5, were ordered to attack the British mainland from Norway across the North Sea, in concert with simultaneous bombing raids in the south by Luftflotten 2 and 3, based in France and Belgium. In a risky ‘flanking’ attack, sixty-five He 111s of KG 26 from Stavanger, escorted by thirty-five twin-engine Bf 110 heavy fighters, were to bomb airfields in the Newcastle area, while fifty unescorted Ju 88s of KG 30 from Aalborg attacked the No.4 Group Bomber Station at Driffield, Yorkshire. The Bf 110s of I./ZG 76 were provided with extra fuel drop tanks, and flew without rear gunners to minimise weight and extend their range. The Luftwaffe expected to find little or no opposition, but instead blundered into experienced Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons posted to rest and refit in the north of England. British Radio Direction Finding (RDF) had detected the incoming waves of German aircraft while they were still miles out to sea, and the defending fighters were directed to intercept them. Though vastly outnumbered, the nimble fighters were more than a match the unwieldy Bf 110s and slow-moving Heinkels. As the Bf 110s went into their familiar defensive circles, the Heinkels scattered, some dropping bombs to little effect on the British mainland, but most jettisoning them to flee for Norway. In total, KG 26 lost eight Heinkels, ZG 76 seven Bf 110s and KG 30 seven Ju 88s destroyed, though the Ju 88s had better speed compared with the Heinkels and had managed to bomb their allocated target. Many others were heavily damaged, and the attack marked their first and last attempt to bomb mainland Britain from Norway. A decoy flight of He 115 floatplanes to the north failed to draw any of the defending fighters away from the attacking bombers, and not a single British fighter was lost, although twelve Whitleys were destroyed by Ju 88s bombing the No.4 Group Bomber Station at Driffield. The Ju 88s dropped 169 bombs of various calibres on the airfield, also damaging hangars and administrative buildings and killing seventeen RAF ground crew by fragmentation bombs and subsequent low-level strafing. However, the aircraft of X.Fliegerkorps played no further significant part in the Battle of Britain, being relegated to night area bombing from the airfield at Beauvais in France, or reverting to maritime harassment missions within the North Sea. Among those aircraft now relegated to the area bombing of Britain, a steady casualty rate continued to claim experienced maritime fliers misused on such traditional bombing missions. For example, Obstlt. Hans Geisse, Kommodore of KG 40, was shot down and killed over London on the night of 7/8 September 1940 in an He 111H-5, and the following night Maj. Johannes Hackbarth, pre-war Adjutant to Generalfeldmarschall Milch and now Kommandeur III./KG 30, was shot down by 602 Sqn Spitfires after another night bombing raid on London. Ditching his Ju 88 in the sea off the Sussex coast, Hackbarth was rescued and became a prisoner of war. Severely wounded, he had his leg amputated below the knee. He was repatriated on 28 November 1943 and relegated to staff duties.

From 15 September He 111s had even begun dropping LMA and LMB naval parachute mines on land targets, fused to explode either by contact or by a clockwork timer. British Army bomb disposal experts were advised against attempting to defuse any unexploded mines found, instead calling on naval personnel from HMS Vernon, the Royal Navy Mine Warfare Establishment. On 21 September 1940 Lt Cdr Richard Ryan RN and CPO Reginald Ellingworth were killed while attempting to defuse one such mine in Dagenham, East London, as it hung by its parachute on a warehouse in North Oval Road. Both were posthumously awarded the George Cross for bravery.32 In night attacks on London during December, KG 26 was also using the heavy SC2500 ‘Max’ bomb, the largest conventional bomb used by the Luftwaffe, which was carried externally on a specially modified bomb rack. A post-war Allied intelligence report on German explosive ordnance records the huge bomb’s appearance:

Sky blue overall. SC 2500 is stencilled on the body in letters 3 inches high. Two yellow stripes are painted on the body between the tail fins. A few anti-shipping bombs have been found with the following stencilled on the body: Beim Abwurf auf Land nicht im Tiefangriff und nur o.V. (not to be released over land in low-level attack and always without a time-delay fuse). This type is thought to be filled with Trialen 105.33

Leutnant Werner Baumbach receives the Knight’s Cross on 8 May 1940 while a pilot with 5./KG 30. Baumbach went on to become a leading expert in maritime operations, eventually becoming Gruppenkommandeur of I./KG 30 before withdrawn from active service to help develop new bomber designs.

While the operational Luftwaffe’s maritime forces were involved, the seaplanes of the Küstenflieger played no significant role in the fighting for aerial supremacy over Britain. Instead they continued making opportunistic attacks on whatever shipping could be found within the North Sea and English Channel. However, the required concentration of available aircraft against mainland Britain also allowed the Luftwaffe to erode the strength of the naval air arm once again. At the beginning of July Göring suggested that the duties of aerial reconnaissance be once again redistributed, proposing that the operational Luftwaffe handle all reconnaissance duties west of Britain, in the Orkney/Shetland area, within a strip thirty miles wide along the British east coast and in the Channel area south of 53°N, a line bisecting Den Helder and Cromer. The aircraft controlled by the Kriegsmarine would only carry out aerial reconnaissance of the North Sea, German coastal approaches and sea lanes to Norway, also undertaking anti-submarine operations within these areas. Therefore, to reinforce Luftwaffe strength and match its increased responsibility, Göring laid claim to the Küstenfliegergruppe 806 and its new Ju 88s, as well as the He 115s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and 3./Kü.Fl. Gr. 906 for ‘reinforcement of the offensive forces’. All Kriegsmarine personnel already assigned to these groups were to be left in place for the time being. His proposal was forwarded to Raeder:

Under my command, Luftflotte 2 and 3 are carrying out the air offensive against the British Isles from the Belgian-Dutch and the French coast. They are equipped with all means for reconnaissance and thereby assure surveillance of the coastal area occupied by us, as well as of the Channel. I request your agreement to this arrangement so that I can immediately issue all necessary orders. Göring

Göring had already provoked the ire of the Kriegsmarine during June, when he sent what was described as a ‘rude telegram’ (unfortunately no longer extant) to Raeder, regarding the Kriegsmarine’s part of Operation Weserübung. Raeder immediately complained in conference with Hitler, who ordered Göring to apologise personally, and Göring complied. The fresh attempts to subvert naval authority over Küstenflieger units merely antagonised an already tenuous relationship. While internally raging at his opposite number in the Luftwaffe, Raeder tactfully agreed with Göring’s view that all air forces needed to be marshalled for the impending battle against Great Britain. This was largely due to diminishing North Sea convoy targets for offensive Küstenflieger operations, and the fact that air support for Germany’s major surface forces was being rendered superfluous as they refitted and repaired following Weserübung. Yet Raeder also noted that the ‘surrender of naval air force formations to Commander-in-Chief, Luftwaffe, however, will have to depend on the tasks at present also falling to the Kriegsmarine.’34 For, like the operational Luftwaffe, the naval air force had also been forced to reorganise and redeploy following the fall of France and the development of bases along the Atlantic seaboard.

During August 1940 the post of Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte West (F.d.Luft West) was abolished and replaced by the position simply known as Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte (F.d.Luft), which remained the domain of Generalmajor Bruch. The office of F.d.Luft Ost was also to be no more, replaced instead by ‘Fliegerführer Ost’ which was, in turn, incorporated directly within Marinegruppenkommando Ost (MGK Ost) in all operational matters. While Hermann Edert departed the post of F.d.Luft Ost to take command of the Ju 87s of Sturzkampfgeschwader 3, Obstlt. Axel von Blessingh, commander of Küstenfliegergruppe 906 since July, took the chair as the newly appointed Fliegerführer Ost, based in Aalborg with 1./Kü.Fl. Gr. 906 (He 115s) and 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 59s) as his available forces.

The extension of the Küstenflieger’s operational area to the Norwegian regions of Tromsø and Kirkenes also demanded the allocation of additional forces. Raeder estimated that at least three Küstenfliegergruppen and two shipborne squadrons (the latter for submarine chase and escort duties) were required for this area alone. Meanwhile, the desired increase in cooperation between aircraft and U-boats in France would also demand at least one Küstenfliegergruppe and the surviving long-range reconnaissance Do 26s of the Transozeanstaffel. Therefore, Raeder replied to the RLM that, while surrender of Küstenfliegergruppe 806 to Commander-in- Chief, Luftwaffe, would be in order, it would be impossible to hand over any elements of Gruppen 106 or 906, as these would be needed for new tasks arising in the French sector. The surrender of Küstenfliegergruppe 806 was agreed on the conditions that:

1. The arrangement is prompted by the need for joint action from joint operational areas and is based on the fact that there is no operational battle Fleet at present available and consequently no necessity for a close tactical tie-up between air formations and surface forces.

2. Gruppe 806 is only ceded temporarily.

3. Gruppe 806 will continue to be staffed with naval observers.

4. The Luftwaffe undertakes, if so requested by Naval Staff, to use this group for naval air warfare for which it is especially qualified.

5. Combat tasks in the central North Sea will be taken over by the adjacent Luftflotten.

However, this diplomatic approach by Raeder quickly stumbled after a visit by Luftwaffe Chief of Staff Hans Jeschonnek to his Kriegsmarine counterpart Admiral Otto Schniewind on 10 July, after which Schniewind had noted in the SKL War Diary:

The statements made by Chief, Luftwaffe General Staff, reveal that the Luftwaffe aims at the surrender of all naval air forces by the Navy.

Nevertheless, on that day Küstenfliegergruppe 806 was transferred to the control of Luftflotte 3 and redesignated Kampfgruppe 806, part of IV. Fliegerkorps based in Caen-Carpiquet. Inevitably, it was never to return to full naval control, though it did continue maritime operations in British waters and later, during 1942, became a part of bomber group KG 54, which had previously lacked a third Gruppe in its order of battle. In fact, Göring had already also put into play the movement of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 to Luftwaffe control prior to Raeder’s response, the naval chief demanding their immediate return to Kriegsmarine command, and Göring responding with platitudes that merely delayed resolution of the issue.

In Brittany, Brest had begun to become established as one of the preeminent Kriegsmarine bases for U-boats and surface security forces, as well as providing repair facilities for future deployment of major warships, and Generaladmiral Saalwächter at MGK West requested the immediate transfer of maritime air forces to the region. As early as 18 June, four days before the French surrender, the SKL had formulated a directive noted within its War Diary for the aerial support of future U-boat operations from French bases.

The Army’s imminent capture of the French Atlantic coast and the resultant possibility of exploiting the naval and air bases there will entail the great advantage for U-boat warfare in the Atlantic that operations can be supported by air reconnaissance.

For this purpose, utilisation of the bases on the French Atlantic coast by U-boats and coastal patrol formations is necessary. For air operations it is intended to establish a special Fliegerführer under F.d.Luft West and to assign him about one group of He 115s (later Ju 88s) and available Transozean aircraft. It will not be possible at present to assign more forces for this task.

The Luftwaffe General attached to Commander-in-Chief, Kriegsmarine, has been instructed to make the appropriate preparations for the necessary transfers.

A settlement of basic questions regarding joint or simultaneous operations by air forces and U-boats will be arrived at between Befehlshaber der U-boote [B.d.U.] and Führer der Luft. (West). The establishment of a U-boat operational headquarters on the French Atlantic coast appears to be necessary for local cooperation in the operational area between the Fliegerführer to be established there and the operational control of the U-boats (for handing over results of reconnaissance, etc.). B.d.U. will investigate the matter and submit proposals.35

Following the occupation of the Atlantic ports, the head of the U-boat service, Konteradmiral Karl Dönitz, ordered the establishment of new U-boat bases at the existing naval and commercial harbours of Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux. During the afternoon of 26 July Dönitz held a conference with Bruch as F.d.Luft West, regarding the reconnaissance requirements of his U-boats and what aircraft were actually available to fulfil these requirements.

At present there are only four Do 18s [2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106] for reconnaissance from Brest. The range of these aircraft and their small striking power as compared with enemy aircraft makes it possible for them to make reconnaissance flights only as far as about square BE 3000 (approximately 150 West) and in a south-west direction. However, the area North of this is not to be covered, owing to the proximity of enemy air bases, so as to avoid unnecessary losses. This reconnaissance will be flown from tomorrow.

From 29 July there will be Do 17s [Kü.Fl.Gr. 606], three Do 26s [Transozeanstaffel] and later a few He 115s [2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906] available.

These types of aircraft can be used off the North Channel, where the most shipping is to be found at present. Unfortunately, the only U-boat available now for operation against this traffic, e.g. the convoy HX58, is U34.

For this purpose, the Do 17s of Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, under its new commander Obstlt. Joachim Hahn, were moved to the captured airfield at Brest-Lanvéoc. However, rather than becoming available for B.d.U. reconnaissance, the Dornier bombers became embroiled in bombing raids against British aerodromes and cities over the following weeks, under the control of IV.Fliegerkorps for all land-target operations. Luftwaffe plans to convert the Gruppe to He 111 bombers were fiercely resisted by Hahn, who considered the aircraft type unsuitable for the coastal operations for which his unit was originally designed. While the Dorniers were tasked with conventional bombing, Hahn at least insisted that a single aircraft be kept at readiness at all times for maritime work.

During September the tug-of-war between the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe over control of Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 reached absolute boiling point. Between 24 and 29 August Hahn’s Gruppe had taken part in raids on the British mainland, and in response SKL and MGK West issued orders that all attacks against strongly defended mainland targets be immediately stopped in order to retain the unit’s readiness for impending maritime operations. The aircraft were instead reassigned to reconnaissance of the southern Irish Sea and St George’s Channel. However, on 6 September the Luftwaffe liaison officer at MGK West (Generalstabs-Offizier d.Lw. in Stab/Marinegruppenkommanddo West), Oberst. Hans Metzner, telephoned SKL and relayed urgent demands from Göring that Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 take part in Operation Loge, the bombing of London that began on 7 September and would last for seventy-six days; now known more commonly as ‘The Blitz’. The Kriegsmarine, of course, refused.

There then followed an increasing cycle of fractious wrangling over dominion of Hahn’s Küstenfliegergruppe. Oberst. Walter Gaul, a former Reichsmarine officer who had transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1934 and was the Luftwaffe Liaison Officer attached to Raeder’s staff (Chef Verbindungsstelle d.Ob.d.L. beim Ob.d.M.), was informed by Major Torsten Christ, Luftwaffe General Staff Operations Officer, that Göring had unequivocally ordered Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 to take part in the assault on London, and requested the necessary agreement from Raeder to ‘avoid unpleasant friction’. Gaul replied that Raeder’s original orders were to be adhered to, and that Göring was outside of his authority giving commands to a unit tactically subordinate to the Kriegsmarine. Christ countered that as Hahn was a Luftwaffe officer his duty bound him to obey the orders of his superior officer. The discussion broke down completely, both sides being intractable in their opposing standpoints, though Christ somewhat menacingly assured Gaul that Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 would indeed take part in Operation Loge.

Finally, on 7 September, OKW ruled that Hahn’s unit was to obey the wishes of the Luftwaffe Staff, Gaul being given a somewhat rewritten history by officers of Luftflotte 3 of how the original confusion and disagreement had begun:

The Kriegsmarine had transferred Küstenfliegergruppe 606 to Brest. MGK West had given it hardly any assignments in connection with naval operations, so that the Gruppe commander (Hahn) had approached the Luftwaffe and asked about the possibility of taking part in attacks on England. Luftflotte 3 had then taken over this commitment in agreement with MGK West. After a time, SKL had forbidden the operations. This order was not complied with. On Thursday or Friday, Generalfeldmarschall Sperrle had reported to the Reichsmarshall along these lines and also added that it was obvious from the operational reports of Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 that the latter was not at all overloaded with work. He had therefore asked permission to include this Gruppe in his Luftflotte for Operation Loge . . . the Reichsmarschall agreed with the view held by Generalfeldmarschall Sperrle and gave permission to include Gruppe 606 in the operation.36

With the endorsment by Alfred Jodl as OKW Chief of the Operations Staff, there was no more room for Kriegsmarine opposition. Hitler also confirmed that Hahn’s Gruppe would take part in the raids, beginning on 8 September. Although they participated in the bombing of Britain from that point onward, the first truly noteworthy attack carried out by Hahn’s Dorniers was during the early morning of 1 October, when four Do 17s led by Hahn took off from Brest to attack the RAF airfield at Carew Cheriton in Pembrokeshire. Skimming the surface of the English Channel to avoid radar detection, they arrived over the airfield and bombed from an altitude of only 30m. In total, the Do 17s dropped forty 50kg and 240 incendiary bombs before strafing the airfield, after which Hahn led his bombers back to Brest unscathed. They left behind them significant damage, one hanger and a number of buildings being totally destroyed, along with two Ansons. One man, AC2 John Greenhalgh, was killed, and another four ground crew were injured. Oberstleutnant Joachim Hahn continued to mount small and effective operations against the British mainland, and on 21 October he was awarded the Knight’s Cross for ‘meritorious operations against England’, the first to be given to a member of the Küstenflieger.37 During the night of 14/15 November Hahn’s Kampfgruppe also took part in the infamous bombing of Coventry, during which, in the course of 469 separate sorties, the Luftwaffe dropped 394 tons of high explosive, 56 tons of incendiaries and 127 parachute LMB mines.

In return, between the last day of August 1940 and the end of the year, Küstenfliegergruppe 606 lost eighteen aircraft, the majority shot down on missions mounted against Liverpool. From these aircraft, only the crew of 7T+LH emerged relatively unscathed and able to fight again after making an emergency landing near Sizun on 21 September, following battle damage inflicted by British fighters. Leutnant zur See Jürgen von Krause and two of his crew from 7T+EH were captured on 11 October after being shot down by fighters near Anglesey following a raid on Liverpool, though his pilot, Fw. Josef Vetterl, was killed. Likewise, the entire crew of Lt.z.S. Hinrich Würdemann’s 7T+AH survived being shot down and were taken prisoner on 20 October, following another raid on Liverpool. All of the remaining aircrew of those Dorniers brought down were either killed or posted as missing in action; their bodies never recovered.

Meanwhile, within the operational Luftwaffe, Coeler’s 9.Fliegerdivision had been subordinated to Luftflotte 2 and transferred to the newly captured Dutch Soesterberg Airfield. Coeler still controlled minelaying missions, including the use of the He 115s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906, and also had a small number of Fw 200C Condors attached from the complement of I./KG 40. The long-distance Condors were tasked with twelve minelaying missions between 15 and 27 July, resulting in the loss of two of these already-scarce machines. On the night of 20 July Staffelkapitän Hptm. Roman Steszyn was shot down by anti-aircraft fire while heading for the Firth of Forth, when he passed too close to Hartlepool’s defences. Two of the crew were captured, while four, including Steszyn, were killed, his body later being washed ashore in The Netherlands. Four nights later, Hptm. Volkmar Zenker, Staffelkapitän of 2./KG 40, was lost during a mission to lay four LMA mines in Belfast Harbour. The Condor successfully reached the dropping point near Black Head in the early morning darkness. Only three of the mines were successfully dropped, and Zenker opened his throttles to make a slowly climbing turn and attempt to drop the last remaining mine. This second pass was observed by gunners at the Greypoint artillery position, the Condor this time approaching only metres above the sea surface, following a descent made with engines at near idle to reduce noise. The last mine was successfully dropped, but as Zenker applied throttle to climb away once more, both port engines failed owing to an air blockage in their fuel lines caused by his gliding descent. With the aircraft suddenly banking to port and no room to manoeuvre, Zenker feathered both starboard propellers and ditched the Condor. He and only two others, Uffz. Heinz Hocker and Gefr. Lothar Hohmann, successfully escaped the rapidly sinking aircraft, but Fw. Willi Andreas and Uffz. Rudolf Wagner went to the bottom. Heinz Hocker gave the following account of the loss of his aircraft:

Advertisement in the pages of Signal magazine for the Arado Ar 196; ‘The eyes of the Kriegsmarine, protector of the coast and successful hunter of enemy submarines.’

Because of the impact the aircraft was full of water very soon. In the cockpit I saw my comrades Wagner and Andreas in the water, looking for an exit. I swam to the other exit in the back of the fuselage, called my comrade Hohmann and told him to get ready with the dinghy. I pushed open the main door and Zenker swam up to us. We left the aircraft. In pitch-dark night I called together my swimming comrades. I only had a distress signal in a tin and the dinghy which had not yet been inflated. For a very long time we called the missing comrades, but in my opinion they went down with the Condor.

Swimming in the heavy swell, I had to inflate the dinghy, which took me eight hours, as the compressed-air bottle had not been connected to it after its last servicing. Zenker and Hohmann climbed into the dinghy first. In the morning we noticed a steamship on the horizon which was heading for us. I realised that Zenker had exhausted himself, and so I took command. In case of capture we should state that we were a reconnaissance flight. Then I searched through Zenker’s pockets and threw overboard anything which could prove to be suspicious. The ship which came towards us was manned by English soldiers.

The crew stood on deck with their rifles loaded, the officer had a pistol. I shot two red flare signals and threw overboard the pistol and ammunition box before putting my hands up. After being taken on board and searched, the sailors supplied us with rum. I was thankful about that, as I could not take any more.38

The three survivors had been rescued by the ASW trawler HMT Paynter, and were taken to the Olderfleet Hotel, which served as headquarters of the Naval Officer in charge at Larne. Under interrogation, in an effort to keep the Condor minelaying operations secret, Zenker and his men repeatedly claimed to have been the crew of an He 111 engaged in a reconnaissance flight.

The delicate Condor had shown itself patently unsuited to the rigours of minelaying, and the task was extremely unpopular with KG 40 Condor crews, a personal appeal from Petersen to Hans Jeschonnek soon resulting in the Condors being ordered to discontinue minelaying missions. They were reconfigured for their intended role of long-range Atlantic reconnaissance from the airfields at Brest and Bordeaux-Mérignac. From there they scored their first minor success with the damaging of the Norwegian freighter Svein Jarl on 18 August, a straggler from Convoy OA199. Two men were injured in the attack west of Bloody Foreland, but the ship reaching Londonderry and was repaired. One week later another Condor sank the 3,821-ton SS Goathland, sailing from Pepel, Sierra Leone, to Belfast with a cargo of iron ore. Finding the ship 630 kilometres west of Land’s End, the Condor from Brest made three bombing runs which finally sent the merchant ship under, all thirty-six crew successfully abandoning ship in lifeboats and later being rescued, despite the Condor’s gunners strafing on each pass.

An He 60 on the ice. Some floatplanes were equipped with special ice runners allowing operation from frozen surfaces during the Norwegian campaign.

Although it was no longer using the Condors, 9.Fliegerdivision continued its minelaying missions, deploying small numbers of a new acoustic mine from 28 August for which the British initially had no countermeasure. Its secrets were revealed in October, when an unexploded example was retrieved by the British and successfully disarmed. Between 14 September and 30 October Coeler’s unit dropped nearly 1,000 mines of different types in British waters, though exhaustive Royal Navy minesweeping helped prevent the closure of ports.

Trials with torpedo-launching He 111Hs were also under way by the middle of 1940, using aircraft of KGr. 126, which had been based in Marx until July 1940, when it was moved to Nantes. The experienced original Kampfgruppe commander, Hptm. Gerd Stein, had been lost in action after his He 111H-4 failed to return from a minelaying sortie off Boulogne. He was briefly succeeded by former naval officer and Staffelkapitän of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 Major Karl-Heinrich Schulz, but he too was soon out of action, after being injured in an aeroplane crash on 2 July, Major Holm Schellmann taking his place. Like his predecessors, Schellmann had a naval background, having entered the Reichsmarine in 1925 before transferring to the Luftwaffe eight years later.

On 22 July four He 111s of KGr. 126 arrived at Lanvéoc-Poulmic Airfield, which they shared with the recently transferred Dorniers of Küstenfliegergruppe 606. While other aircraft of KGr. 126 dropped their 1,000th aerial mine in British waters four nights later, a feat recognised in the SKL War Diary, in which they praised the unit’s ‘indefatiguable and courageous activity under most difficult weather conditions and against strong defence’, the four aircraft at Lanvéoc-Poulmic were scheduled to begin conducting combat trials of newly developed torpedo-launching gear for the He 111H-4; the external PVC bomb rack modified to carry two torpedoes. An initial planned operation was scrubbed owing to poor weather, and the four did not fly operationally until 28 July. However it was no success, according to the report they filed with KG 40 Staff in Oldenburg, under whose temporary operational control they had passed. While three of the Heinkels returned to their original airfield in Niedersachsen (i.e. Marx in Lower Saxony), the aircraft commanded by Oblt.z.S. Helmut Lorenz remained in Lanvéoc-Poulmic. A scattering of planned missions were scrubbed one after another until the middle of August when, in company with a second new He 111 arrival from Marx (commanded by Oblt. Josef Saumweber, formerly of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706), Lorenz mounted a torpedo mission in the southern entrance to St George’s Channel. Two torpedoes were dropped, one passing ahead and one astern of a targeted merchant ship despite being launched at close range and with only 1 degree separating the two torpedoes’ set gyroscope angles.

The increasingly active Lanvéoc-Poulmic Aerodrome was attacked by Blenheim bombers on 11 August and again two nights later, killing two men and seriously injuring another five, though relatively minor damage was inflicted upon what was still a fairly rudimentary airfield infrastructure. The raids also failed to halt Lorenz’s planned flights. Another mission was launched in the evening of the second Bomber Command raid, dropping two torpedoes which again missed ahead and astern of the targeted vessel. On 16 August an attempted attack on a small trawler west-south-west of The Smalls (wildly overestimated to be a ship of ‘5,000 tons’, as opposed to its actual 294 tons) missed once again, at least one torpedo breaking surface several times before settling on to its course. Lorenz felt that he had conclusively proved that the launch gear was not yet functioning as intended. Kriegsmarine torpedo engineers had arrived at Lanvéoc-Poulmic, and further adjustments were made to the aircraft’s release gear before its next daylight flight, on 19 August. Lorenz was down to his last four torpedoes, and 9.Fliegerdivision had twenty more shipped to the Kriegsmarine torpedo storage facility at nearby Brest, along with parachute mines and the associated tools required for their maintenance. Before these arrived, the last of the available torpedoes were fired in consecutive missions, all of which failed; three out of four being classified as gyro failures, as they circled after launch, and the fourth disappearing completely.

The relatively undeveloped infrastructure of the increasingly cramped airfield at Lanvéoc-Poulmic, as well as bouts of illness suffered by Lorenz, delayed further torpedo operations, and the two KGr. 126 Heinkels were moved to the more-developed Nantes Airfield instead. Not until 8 November was Lorenz active again with his torpedo operations, leading three He 111H-4s of 1./KGr. 126 to Brest-Guipavas in preparation for a mission the following day against convoy traffic in the Irish Sea. Like Saumweber, the last aircraft commander, Oblt. Friedrich Müller was also a former naval officer and a highly-experienced aircraft commander, and the Heinkels lifted off towards the Irish Sea in poor weather conditions, with low cloud and limited visibility. Their journey had not proceeded far from the French coast before a Blenheim Mk.IVF of 236 Sqn, Coastal Command, intercepted them at 1416hrs. Pilot Officer Dugald Lumsden was on independent patrol over the Western Approaches when he sighted the trio of Heinkels and immediately attacked. Lorenz’s wireless operator, Fw. Peter Hermsen, was killed almost immediately when a bullet from the Blenheim hit him in the forehead. As the Heinkels separated and aborted their mission, pilot Fw. Walther von Livonius threw Lorenz’s aircraft into evasive manoeuvres, but bullets ripped into the port engine and shattered cockpit instruments. Flight engineer Flieger Otto Skusa was badly wounded in the leg and, though the Blenheim made no more firing passes, the Heinkel went down into the Bay of Biscay. After the shuddering impact with the sea, the forward half of the Heinkel momentarily submerged before rising back to the surface and allowing the three survivors to escape. Their life raft had been riddled with bullets, and they were soon in the numbing cold of the Biscay water, kept afloat by their kapok lifejackets. After drifting for more than an hour, Otto Skusa was unable to remain afloat, lapsed into unconsciousness through blood loss, and slipped beneath the surface. Finally, their crash having been reported by Kriegsmarine artillerymen on the distant Ile d’Ouessant, a Breguet 521 Bizerte seaplane KD+BC of Seenotflugkommando 1, piloted by Lt. Paul Metges, recovered the two remaining survivors. The He 111 still had some way to go before it became a fully operational torpedo bomber.

During July, as the battle for air supremacy over Britain was poised to begin in earnest, Kriegsmarine commands stretching along the Dutch, Belgian and French coasts were ordered to co-operate closely with Luftflotte 2 and 3, who were to bear the brunt of forthcoming operations, and elements of the Küstenflieger (2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906) were temporarily assigned to air-sea rescue duties to augment the available aircraft of the Seenotdienst. The air-sea rescue service played an important role in the recovery of downed crewmen of both protagonists from the war’s earliest days. With increasing levels of combat over the North Sea and English Channel, the He 59s, painted white, and with large Red Cross markings and no defensive armament, flew an ever-increasing tempo of missions to retrieve airmen stranded at sea, not without considerable risk to themselves. During the early morning of 1 July He 115 M2+CL of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106, under the command of Lt.z.S. Gottfried Schröder, crashed off Whitby through engine failure during a minelaying mission. At first light an He 59 of Seenotflugkommando 3, bearing the civilian registration D-ASAM, departed from Schellingwoude in The Netherlands. It was flown by Uffz. Ernst Otto Nielsen (untrained in night flying and therefore forced to await first light before departure) and commanded by L.t Hans Joachim Fehske. After Fehske had guided the aircraft to the Heinkel’s last reported position by dead reckoning, he instructed Nielsen to approach the British coast in order to attain a firm navigational fix, flying between the coastline and a southbound convoy as they did so. Three Spitfires of 72 Sqn were scrambled to intercept, Flt Lt Edward Graham circling the brightly painted aircraft with brilliant Red Cross markings and the equally bold red-banded swastika of a civilian aircraft on its tail. He was initially undecided, and it took several minutes and the presence of the convoy nearby to convince Graham that the oddlooking Heinkel was hostile. In three separate strafing runs the Spitfires shot it down, noting no defensive fire and no evasive action taken, though Fg Off Edgar Wilcox also recalled seeing the ‘enemy aircraft jettison some small objects which I thought were small bombs’. One of the Heinkel’s engines had been quickly disabled and its radio equipment was smashed, and medical orderly Uffz. Struckmann was shot twice through the legs. After an emergency descent the aircraft began to sink tail-first as all four crew took to their dinghy, to be rescued by HMS Black Swan shortly thereafter. The He 115 crew that had been the object of their search-and-rescue mission were also eventually rescued after twentyeight hours at sea and taken to Grimsby Harbour. Fehske and his crew loudly protested the shooting down of a non-combatant aircraft, though British investigators who examined the wreckage later claimed to find cameras aboard, suitable for use in reconnaissance work.

Eight days later a second plainly-marked Seenotdienst aircraft was brought down. The He 59B-2 of Seenotflugkommando 1, registered D-ASUO, took off from Boulogne and flew via Calais to Ramsgate to look for any of six Messerschmitt Bf 110s shot down into the Channel during a convoy attack earlier in the day. The Heinkel, which approached to within sight of the convoy that was still transiting the Channel, had a covering Staffel of Bf 109 fighters, which was sufficient to convince the leader of a group of 54 Sqn Spitfires flying convoy cover that it was hostile. New Zealander Flt Lt ‘Al’ Deere led his Spitfires into an attack on the German fighters, a melée soon developing in which Deere collided with a Bf 109 flown by Obfw. Johann Illner, both aeroplanes limping away to crash-land safely. Two Spitfires were shot down with both pilots killed, while Fg Off John Allen attacked the He 59 and hit it with a single burst from his machine guns. As soon as the unarmed aircraft was damaged, pilot Uffz. Helmut Bartmann alighted on the sea within sight of the Kent coastline, where its floats became bogged down after running into a thick glutinous sandbank of the Goodwin Sands in the ebbing tide. Before long the Heinkel was taken in tow by the Walmer Lifeboat and beached near the lifeboat station, where its crew was taken prisoner. All four crew members were found to be registered with the International Red Cross, and apparently seized the opportunity to explain the purposes of the Seenotsdienst organisation and attempt to prevent future attacks on what was a humanitarian mission. However, a search of the aircraft’s interior yielded the pilot’s log book, in which Bartmann had recorded convoy positions and directions, justifying British conclusions that the aircraft could not be considered non-combatant. Interestingly, papers belonging to Seenot aircraft D-AGUI were also found that described the rescue of RAF Sqn Ldr Kenneth Christopher Doran on 30 April after his Blenheim IV of 110 Sqn was shot down during a bombing raid on Stavanger Aerodrome, Norway.

30/4./40. Verbal orders 1950hrs, search for Englishmen shot down about 10km west of Stavanger. Weather perfect. Visibility 50km, wind 130° 25km. Start 1952hrs. At 2015hrs oil spots in Grid Ref.3125. Sighted a man drifting in rubber dinghy, beside him a man swimming. We landed beside them 2200hrs. Sea strength 2. The dinghy drifted between the floats and was made fast. Both Englishmen hauled into the machine. The first, who was in the dinghy was slightly wounded on his chin, protested that he did not need first aid. We made him fast to the ‘Tragbahn’. The second was already drowned. Artificial respiration in the machine had no effect. Owing to the rolling of the machine and the heavy load, the stern ladder broke. Took off for return flight at 2055hrs and landed at Stavanger 2110hrs. It turned out later that the rescued Englishman was a Staffelführer, with the rank of major, the other who had been unable to get into the dinghy was his observer [Pt Off F.M.N. Searle].

Note: The companion ladder must be strengthened; that would make it easier to get people on board. Light rubber overalls reaching up to the chest are wanted – at least two per aircraft, as the crew get wet when carrying out rescues and often have a long return flight afterwards.39

A third He 59, D-AGIO, shot down on 11 July in the vicinity of a convoy south of the Devon coast, finally settled the issue as far as the British were concerned, and despite vehement German protests that the Seenotdienst aircraft were protected by articles of the Geneva Convention, on 14 July the British issued Air Ministry Bulletin 1254 in which they declared:

Enemy aircraft bearing civil markings and marked with the red cross have recently flown over British ships at sea and in the vicinity of the British coast, and they are being employed for purposes which His Majesty’s Government cannot regard as being consistent with the privileges generally accorded to the Red Cross. His Majesty’s Government desire to accord to ambulance aircraft reasonable facilities for the transportation of the sick and wounded, in accordance with the Red Cross Convention, and aircraft engaged in the direct evacuation of the sick and wounded will be respected, provided that they comply with the relevant provisions of the Convention.

His Majesty’s Government are unable, however, to grant immunity to such aircraft flying over areas in which operations are in progress on land or at sea, or approaching British or Allied territory, or territory in British occupation, or British or Allied ships. Ambulance aircraft which do not comply with the above requirements will do so at their own risk and peril.

By specifically withdrawing any tacit or implied permission for the Seenotdienst to operate over the North Sea or English Channel combat zones, any perceived protection provided by the 1929 Geneva Convention was technically removed, as it required agreement ‘between all the Parties to the conflict’. On Dowding’s orders the British subsequently declared that, as of 20 July, Seenotdienst aircraft would be shot down without warning.

On that day, as it forecast, He 59 D-AKAR of Seenotflugkommando 4 was intercepted and shot down by Hurricanes of 238 Sqn flying as convoy escort south of the Needles, near the Isle of Wight. The Heinkel was seen to make an emergency descent approximately three miles from the French coast, though it was never found. The body of pilot Fw. Herbert Dengel was later washed ashore on the beach at Mers-le-Bains. The remaining three crewmen were listed as missing in action.

During July the Seenotdienst was officially incorporated into the Luftwaffe as Luftwaffeninspektion 16 (Air Force Inspectorate 16), under the direction of Generalleutnant Hans-Georg von Seidel, the Luftwaffe’s Quartermaster General. On 29 July RLM ordered all Seenotdienst aircraft be armed and painted as normal front-line aircraft. The civil registrations were dropped, the aircraft being given standard Stammkennzeichen (the military four-letter codes) instead. By November they had become fully militarised, being redesignated Seenotstaffeln rather than Seenotflugkommandos. Before completion of the camouflaging of all Seenotdiesnt aircraft, British aircraft began receiving return machine-gun fire from the white-painted Heinkels still carrying Red Cross markings, and more than one merchant ship also reported being strafed by Seenotdienst aircraft.40

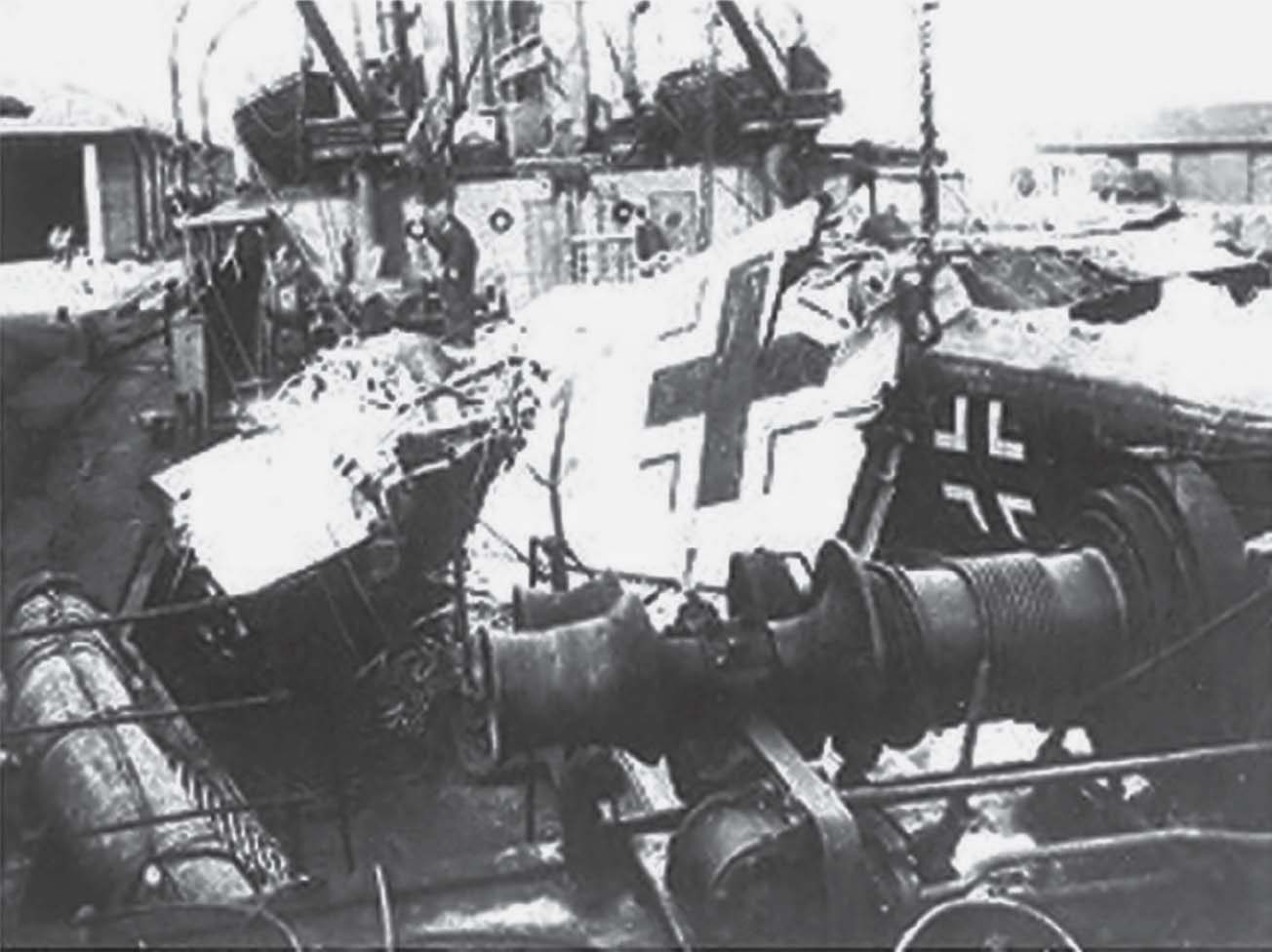

Bordflieger Arado Ar 196s carried aboard capital ships proved their worth many times over, though that of the Scharnhorst also mistakenly bombed Otto Kretschmer’s U99 on 21 June 1940. (James Payne)

Additionally, the British government, and Winston Churchill in particular, were aware that by allowing the rescue of trained aviators who had been shot down at sea they were returning them to action, whereas the fact that downed German aircrew generally landed on British soil, or at least descended in the no-man’s-land of the English Channel, denied valuable manpower to the Luftwaffe. They therefore issued a fresh policy on 26 August regarding all German rescue vessels, which also encompassed the Seenotdienst air-sea-rescue boats.

Sixty-four small vessels marked with the Red Cross and notified by Germans as detailed for rescuing airmen will not be recognised by H.M. Government as entitled to Red Cross protection, and after midnight 30/31 August will be liable to be captured and sunk. Till that midnight these vessels should be dealt with under Article 4 of the Tenth Hague Convention.