6

The End of the Beginning

The Atlantic Battleground

DURING THE AUTUMN OF 1940 the SKL had requested that air bases be established at Lorient and Saint-Nazaire, to support U-boats deployed on the French Atlantic coast. Demonstrating the acidity that relations between the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe had reached, the Luftwaffe General Staff replied that inspections had yielded ‘no facilities there suitable for the construction of air bases’, adding that there was no guarantee that any more suitable places would be found within the vicinity. Nonetheless, operational Luftwaffe and naval air units were moved to the Atlantic coastal region during the latter half of 1940.

Dönitz had been expecting Luftwaffe co-operation since his U-boats first began sailing from the French Atlantic ports, hoping for aerial reconnaissance to augment the already effective information gathering of B-Dienst, the Kriegsmarine’s radio intelligence service. On 14 August 1940 he had noted in the B.d.U. KTB that KG 40 was to fly reconnaissance in the U-boats’ area of operations off the North Channel from that date onward, but that little had come of it. The Luftwaffe continually claimed a lack of available aircraft, and only single flights were occasionally made, and they provided reconnaissance reports of dubious value. By November Dönitz was appealing strenuously to both MGK West and Nord for reconnaissance aircraft to patrol regularly both north-west of Scotland and to the west of Ireland, and on 16 November he obtained agreement from Generaladmiral Saalwächter at MGK West. However, the immediate reconnaissance of the North Channel area was only partly carried out, because Do 26 P5+EH, which had been despatched by the Transozeanstaffel, crashed immediately after launching. Based in Brest and supported by the catapult ship Friesenland, the Dornier suffered engine failure after being catapulted from the ship, and plunged into the water, killing all six crewmen.1 Furthermore, nearly all of the BV 138s of Küstenfliegergruppe 406, based in Brest, were grounded for an expected two months owing to technical faults that had come to light since their active deployment. Without their assistance, in heavy weather during the first two days of December, U-boats closed on Convoy HX90 and managed to sink eleven of its forty-one ships. Although this was a significant success (though over-claimed as eighteen ships sunk by the commanders involved in the confused melée), the U-boats soon lost contact, frustrated by escorts, bad weather and the limited range of vision permitted by a U-boat’s low conning tower. In his War Diary entry for that day, Dönitz lamented the lack of supporting aerial reconnaissance:

The major thing was to establish contact. This couldn’t be done:

a) by the boats themselves . . . or,

b) by aircraft of which unfortunately only a very few were available:

One Fw 200 from KG 40 Bordeaux, two BV 138s from Brest, Gruppe 406.They did not make contact.

The situation therefore remained obscure during the day. This operation shows up the gaps which inevitably result from warfare with so few U-boats . . . But it is equally clear that these gaps can be very effectively filled, as far as making contact goes, by using aircraft. Even a few isolated reports would be of greatest value. But there are only two BV 138s from Küstenfliegergruppe 406 available for this task and one Fw 200 from KG 40, which is used for this purpose by arrangement with the Gruppe. Success is correspondingly small: they did not make contact.2

It was a theme that had been regularly voiced both by Dönitz and his naval superiors since before the war. Even the reverse use of U-boats to guide aircraft to targets had failed, as evidenced by Kaptlt. Wolfgang Lüth’s attempt to have the 10,350-ton New Zealand Shipping Company merchant MV Orari finished off by Luftwaffe attack. Lüth had hit the motor vessel in the stern with one of his last two torpedoes, fired south-west of Ireland at 2046hrs on 13 December as he made his way back to Lorient after over a month at sea. As it was impossible to use the U-boat’s deck gun owing to bad weather, the damaged freighter was free from further interference, and wallowed onwards at reduced speed. Lüth followed for six hours while transmitting beacon signal and weather reports for a planned KG 40 Condor mission during the early morning. With no other U-boats in the area, Dönitz was enthusiastic about the opportunity to consolidate co-operation with the Luftwaffe with a success to which a U-boat had made a major contribution, and to test the practicability of calling up aircraft by means of U-boat reports. Although KG 40 undertook to despatch an aircraft, its take-off was delayed until 1100hrs, which meant that the aircraft would be unable to reach the target before 1400hrs. Meanwhile, Lüth reported that U43 was forced to break away and continue its return passage owing to a dangerously low level of lubricating oil. The plan was stillborn, and Orari’s crew managed to cover the torpedo hole with tarpaulins and reach the Clyde, where they began repairs that returned the ship to service in March 1941. Dönitz was disappointed and frustrated:

In an image captured by a military photographer using a long-distance lens, an He 59 of the Seenotdienst rescues the downed crew of a Bf 110. By the time this photograph was taken the rescue service’s previous neutral colour scheme had been replaced with military camouflage and markings.

I very much regret this failure of my plan, especially as every individual success attracts the attention of the authorities which would be concerned in the organisation of a large-scale co-operation and proves its practicability better than theoretical exposition can. Co-operation is necessary.3

Once again, Dönitz summarised the aerial reconnaissance requirements of his U-boat service within the B.d.U. War Diary, and submitted a copy as a memorandum to Raeder’s office in Berlin.

The war has shown that the tactics of operating several U-boats together against a convoy are correct and lead to great success. In all cases, however, the first contact with the convoy was a matter of chance. The convoy approached a U-boat. In other cases, when this did not come off, the boats were at sea for days to no purpose. Time was wasted in the operations area. Full use of the U-boats against the enemy is not being made because of the lack of any form of reconnaissance.

B.d.U. is aware that Naval War Staff has been advocating the necessary reconnaissance with the Luftwaffe Ops. Staff for a long time. B.d.U.’s views on co-operation with the Luftwaffe are as follows:

a) The U-boat is of little value for reconnaissance. Its radius of vision is too small. It is too slow to be able to cover a large sea area in a short space of time, and we have insufficient numbers to attempt to do so. To use them for this purpose also wastes their fighting power. The U-boat can achieve much more if it does not have to hang around for weeks waiting for its prey to turn up, but, by means of previous reconnaissance, can be directed to the area where the enemy actually is. Every service arm has its own means of reconnaissance — except the U-boats.

b) By the use of long-range reconnaissance, the Luftwaffe can provide us with clear and definite information as to the whereabouts of the enemy, and can thus provide operational control with data on which to base the disposition of the U-boats.

c) The Luftwaffe can also support immediate U-boat operations by flying exhaustive reconnaissance of the area in which the boats are disposed, by reporting the valuable targets immediately and thus ensuring that enemy units within range are actually attacked, and that no enemy formations pass through the area occupied by U-boats without their even detecting them because of their small visual range.

d) But potential co-operation between aircraft and U-boats does not end simply with reconnaissance. The aircraft should shadow by day until the boats reach the enemy, bringing up the boats by using beacon signals; if contact is lost, it can be regained by aircraft after first light of the next day, etc. It is therefore a question of the closest tactical co-operation for a single co-ordinated operation.

e) The performance of these missions will in no way restrict or hamper normal air attacks against merchant shipping. In fact, it can only be an advantage to the U-boats if these aircraft attack and sink and damage ships, worry, divert and scatter the enemy. The areas in which the U-boats are stationed offer good prospects of success for aircraft attacks, because the U-boats occupy the busiest shipping areas. Aircraft attack need not be limited even if the U-boats are in the immediate vicinity. The only thing which the aircraft must not do is to attack submarines. Experience has shown that the danger of mistaking enemy submarines for our own U-boats is too great to permit the aircraft to attack, even if it is certain that it is dealing with an enemy submarine.

f) The best thing would be to discuss this form of co-operation directly with the Luftwaffe units concerned and try it out in practice. But in order to foster genuinely effective co-operation it is necessary: 1) to have sufficient forces; 2) to have a clear ruling as to command and control.

Once a convoy has been sighted, the subsequent co-operation — such as shadowing by an aircraft making beacon signals — must be controlled by the man who is directing the convoy operation, though this will not encroach upon the tactical leadership of the Luftwaffe Officer commanding the air unit engaged. This means that B.d.U. must decide where reconnaissance is to be flown and how many aircraft are to be used in each case, and have the available means at his disposal if a unified and rational method of co-operation is to be achieved. Close co-operation has so far been carried out with the following units:

a) Küstenfliegergruppe 406 Brest, which is tactically subordinate to MGK West. Their long-range BV 138 aircraft are, however, grounded for about two months because of technical defects.

b) KG 40 Bordeaux. No official contact. A degree of co-operation achieved by personal agreements. Type Fw 200. At present, generally only about one aircraft out by day.

c) Luftflotte 5 flies reconnaissance of a certain area from time to time by special request. So far only carried out once. Recently requested again but refused because of lack of available aircraft.4

Pilot and observer aboard a Dornier Do 17, both wearing standard-issue Luftwaffe steel helmets.

Mindful of Dönitz’s recommendations, and somewhat chastened by Hitler’s previous directive that heavily favoured Luftwaffe control of naval air operations, Raeder had fresh memoranda prepared for another meeting with the Führer, scheduled for 27 December 1940, as the tempo of operational flying was reduced by poor weather. Within its text, Raeder pushed for a small list of imperatives: the return of Küstenfliegergruppe 606 to Kriegsmarine tactical control, responsibility for aerial torpedo operations to rest with the Kriegsmarine, the intensification of Atlantic aerial reconnaissance in support of U-boat operations, and permission to use naval air units in strikes against enemy warships. To support his application on behalf of the U-boat service, Raeder despatched Dönitz to a meeting with General Jodl to present his observations in person. The meeting was both constructive and convivial. Dönitz asked for a daily reconnaissance sweep by twelve Fw 200s, and Jodl, in turn, raised the matter directly with Hitler.

Although most of the Kriegsmarine requests were treated with consideration by the Führer, perhaps indicating the loss of prestige that Göring had suffered within the halls of OKW as a result of the Luftwaffe’s failure to destroy the BEF at Dunkirk and the RAF over Britain, few concessions were granted. On 6 January 1941 a directive was issued by the Führer that ordered I./KG 40 (Fw 200) to be assigned to the Kriegsmarine to operate directly under B.d.U. control; something that had already been promised by the Luftwaffe since August 1940 but never delivered upon. Göring was instructed to bring the squadron to a strength of twelve Condors, maintaining that number ‘if necessary by assigned additional aeroplanes of type He 111’. Hitler also, however, confirmed the transfer of the Ju 88s of Küstenfliegerruppe 806 to Luftwaffe control and attachment to Luftflotte 3.

While Hitler’s directive demonstrated that the importance of aerial reconnaissance to Dönitz’s U-boat service had been acknowledged and accommodated, little else was given to Raeder and the Kriegsmarine. Nonetheless, Hitler’s decision signified a leap forward for the U-boats, albeit one that still required technical hurdles to be overcome before truly bearing fruit. The rate of Condor serviceability was extremely low, as the civil aircraft’s airframe was not up to the rigours of operational military service over the Atlantic. However, while Dönitz was justifiably pleased, Göring was far less so, as it transpired that Hitler’s decision had been made while the Luftwaffe chief enjoyed one of his many holidays in Paris. Not having been consulted, Göring was furious at what he saw as an attempt to subvert part of his domain once again to Kriegsmarine control. The Luftwaffe chief immediately summoned Dönitz from the Paris B.d.U. office to his own headquarters train, lying in a siding at La Boissière le Déluge, between Paris and Dieppe. This was the first meeting of the two men, and Göring attempted alternately to persuade and threaten Dönitz to return KG 40 to Luftwaffe control.

Over coffee he heaped upon the Admiral remarks that Dönitz described in his report as ‘distinctly unfriendly.’ ‘You can be sure of one thing,’ Göring snapped, ‘As long as I live, or until I resign, your Grossadmiral Raeder will never get a fleet air arm.’ Pointing out that he, Göring, was ‘the second man in the state,’ he threatened that even if Dönitz should somehow get his hands on KG 40 he would not be likely to find replacements for its long-range aeroplanes. ‘I need Fw 200s too,’ he shouted, ‘and it’ll serve you right!’5

They parted as what Dönitz later described as ‘bad friends’. The matter remained unchanged, and I./KG 40 was retained by U-boat headquarters, though obviously the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe’s intractable dispute over operational control continued. The former protocols of spring 1939 were completely abandoned by Göring due to what he had termed the ‘urgencies of war’.

Although the Fw 200 was a stopgap measure, it had already begun to prove its worth within the Atlantic battleground. By the end of 1940 KG 40 had been credited with sinking 800,000GRT of enemy shipping, though this estimate was far higher than the reality. Nevertheless, it was a notable start to Atlantic missions, and had cost the loss of only two aircraft thus far. The first had been on 20 August, when Oblt. Kurt-Heinrich Mollenhauer’s Fw 200C-2, F8+KH of I./KG 40, crashed into Faha Ridge, Mount Brandon, County Kerry, Eire, during a meteorological mission made in dense fog. Most of the crew suffered broken limbs, but recovered and later became the first internees in Camp Curragh, County Cork. The second loss was the Fw 200 flown by Oblt. Theophil Schuldt, Staffelführer of 2./KG 40, which crashed off the Irish coast for unknown reasons during another meteorological mission. The pilot’s body and that of meteorologist Regierrungsrat Dr Johannes Sturm were washed ashore some time later.

Bernard Jope of KG 40. A veteran of the Spanish Civil War he was awarded the Knight’s Cross on 30 December 1940 following the destruction of SS Empress of Britain.

The most successful single attack had taken place on 26 October, when Oblt. Bernhard Jope attacked the 42,348-ton liner SS Empress of Britain seventy miles north-west of Donegal Bay. The liner was returning from transporting troops to Suez via Cape Town, carrying 224 military personnel and civilians plus a crew of 419 men. Jope sighted the ship and immediately dived out of the cloud cover on a strafing and bombing run, dropping six bombs, two of which hit (the ship’s master reported five). The first bomb exploded in the main lounge, which immediately caught fire and sent dense clouds of black smoke spreading throughout the ship’s enclosed areas. Although the liner’s speed was increased and exaggerated zig-zagging undertaken, a second bomb struck as Lewis gunners returned fire, hitting the Condor several times before the attack was over. The fire aboard Empress of Britain rapidly spread, overwhelming all efforts by the crew to contain the blaze. Captain Charles Havard Sapworth gave the order to abandon ship at 0950hrs, only thirty minutes after the first attack. Most of the crew and passengers were picked up by the destroyers HMS Echo and ORP Burza, and the anti-submarine trawler HMS Cape Arcona, which also recovered an apparently substantial quantity of gold bullion being transported from South Africa. A skeleton crew remained aboard to fight the blaze that raged throughout the day and night, the ship floating on an even keel but gutted by the inferno, with its hull plates visibly glowing red. The only hope of salvage now seemed to be if the flames died out of their own accord. However, it was not to be. The stricken ship was sighted by Kaptlt. Han Jenisch in U32 and finished off by torpedoes, though the nearby destroyers remained unaware of the U-boat’s presence and believed the explosions to have been caused by the fire reaching the fuel oil bunkers.6 Almost miraculously, considering the machine-gunning by Jope’s Condor and intensity of the ensuing blaze, only twenty-five crew members and twenty passengers were lost.

Jope, a veteran of bomber missions during the Spanish Civil War as a member of K 88, returned successfully to Bordeaux-Mérignac and was feted for the achievement of seriously damaging the second largest ship operated by Britain, and the largest ship to be sunk by U-boat in the war. Mentioned in the Wehrmachtberichte of 29 October, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross on 30 December 1940.

With little by way of aerial opposition within the Atlantic, by the end of 1940 the Condors of KG 40 harvested a deadly toll of enemy shipping sunk or damaged. Indeed, between August and February 1941 the unit claimed over 343,000 tons of ships sunk. Even allowing for wishful thinking and the resultant over-claiming, it was a remarkable success. During December all available KG 40 aircraft were used to fly reconnaissance for the approach of the cruiser Admiral Hipper, returning from an Atlantic raiding voyage to Brest Harbour for routine maintenance, and this forestalled any co-operative U-boat reconnaissance for several days. However, after Hipper’s departure from Brest on 9 February 1941, five Fw 200s of I./KG 40 attacked Convoy HG53 in cooperation with the U-boat U37, which had already struck, sinking two ships, and was providing position reports for both the Luftwaffe and the Admiral Hipper, which was in the vicinity of the Azores at that time. Led by Hptm. Fritz Fliegel, the Condors bombed and sank the 2,490-ton SS Britannic, carrying 3,300 tons of iron ore from Almeira, the 1,759-ton SS Jura with 2,800 tons of pyrites, the 967-ton Norwegian freighter Tejo, carrying wine, and the 2,471-ton Dagmar I, on a voyage from Malaga for the Clyde with 1,100 tons of oranges and oxide. Between them, the destroyed merchant ships lost twenty-seven men. The steamer Varna was also heavily damaged. Its entire crew was rescued, although the ship did not finally sink until 16 February. In return, Fw 200 F8+DK, flown by Oblt. Erich Adam, was hit by anti-aircraft fire and damaged, breaking away to crash-land in Moura, Portugal. The crew sabotaged the abandoned aircraft and were briefly interned while trying to escape in civilian clothes in the Safara area. Transported to Moura, they were placed in the Grande Hotel before repatriation to Germany. Attempts to bring the Admiral Hipper into action against HG53 failed, though the cruiser sank a straggler on 11 February. Instead, Hipper abandoned the chase and attacked Convoy SL64, sinking seven of its nineteen ships. For the first time a capital ship, U-boat and aircraft had successfully cooperated against an enemy convoy, demonstrating the potential of joint Kriegsmarine-Luftwaffe operations.

The wreckage of Oblt. Erich Adam’s KG 40 Condor F8+DK which crash landed in Portugal before being blown up by its crew who were briefly interned before repatriation to Germany.

Thus-far unidentified Luftwaffe Leutnant who served as pilot during weapon testing for the Heinkel He 115. His personal photo album provides a unique glimpse into the behind the scenes development of the Luftwaffe maritime force, including his role as pilot of an He 115 in the film ‘Kampfgeschwader Lutzöw’. (James Payne)

However, although KG 40 was garnering obvious success against merchant shipping, Dönitz was unsatisfied with the level of co-operation between the aircraft and his U-boats. The method by which sighting information was relayed to individual U-boats was extremely ponderous, as the aircraft could not communicate directly by radio with the U-boats themselves owing to a lack of equipment and trained personnel, and differing radio procedures. The reporting aircraft would shadow while transmitting long-wave homing signals via a trailing aerial, these being picked up by U-boats and retransmitted by short signal to B.d.U., who plotted the various beacon signals and attempted to eliminate navigational errors before retransmitting a corrected position to the U-boats at sea. This procedure took valuable time, the aircraft frequently having then shifted location or departed owing to a lack of fuel if operating at extreme range. Additionally, location of convoy traffic itself was difficult for the Luftwaffe crews. In a typical mission to the sea area west of Ireland, a Condor possessed enough fuel to stay on station for approximately three hours before forced to return. During this time crewmen would be sweeping the sea with binoculars, the aircraft tending to fly at about 500m altitude, which allowed a search radius of around twenty kilometres in bright clear weather; frequently not the case in the Atlantic.7

Filming of the Heinkel He 115 scenes for the film ‘Kampfgeschwader Lützow’ 100 kilometres west of Warsaw in August 1940. The aircraft used was an He 115 B1/C, probably BH+AM that was being used for torpedo trials at Travemünde and was later lost in a bad landing on 28 December 1942 while serving with Küstenfliegergruppe 906.

Also, apart from the lack of available dedicated reconnaissance aircraft, which were frequently diverted to special bombing missions, it appeared that the British were re-routeing their convoys further to the north, pushing the intercepting U-boats towards Iceland. Aircraft of KG 40 based at Bordeaux could only effectively cover the southeastern corner of this most northerly U-boat disposition, even if the long-range Condors departed from France and flew a circular route to land in Stavanger or Aalborg for refuelling. Dönitz reasoned that KG 40 could therefore really only provide information on shipping traffic in the southern sector, at that time patrolled only by Italian boats of the newly created BETASOM command, and for whose fighting value Dönitz harboured little respect.

Immediate co-operation with our own boats is not possible. This state of affairs is unsatisfactory. There are considerable difficulties involved in the transfer of the whole Gruppe to Stavanger and Aalborg, and the advantages to be gained by such a move are outweighed by the many disadvantages which would result. The matter must be discussed with the Commanding Officer of the Gruppe as soon as possible.8

At a discussion between Dönitz and Major Petersen of I./KG 40 on 13 February, in which Dönitz requested that some aircraft be permanently relocated to Norway, it was concluded that a transfer of I./KG 40 was impossible at that point in time and unlikely to be made before the spring, as bad weather frequently hampered the operational effectiveness of the Scandinavian airfields. Dönitz therefore requested, via Petersen, that the Luftwaffe develop facilities at both Stavanger and Rennes to enable such operations in the future, while individual aircraft would begin to use the circular route, refuelling in Norway before making a return flight the following day. The threat posed by these returning Fw 200s was very much recognised by the British Admiralty.

Enemy air attacks are being carried out in bad weather on ships and ports on the East coast with comparative immunity owing to the inability of our aircraft to take off to counter them. C-in-C Rosyth urges that the enemy bases on the coast of Norway should be bombed. A Blenheim is to patrol over Stavanger Aerodrome nightly from 23 February in order to endeavour to keep Fw 200 aircraft from taking off during dark hours.9

On 19 February Bernhard Jope’s Fw 200 was on armed weather reconnaissance near the Hebrides, before landing in Stavanger, when his crew sighted Convoy OB287 eighty miles north-west of Cape Wrath. Jope attacked through rain showers and, ignoring a pair of towed barrage balloons, dropped three bombs on one ship, two of which missed astern and the third hit the quarterdeck, and three on another, one a direct hit on its boiler room, which exploded. However, through lack of fuel he was unable to linger and transmit beacon signals for the benefit of U-boats, and despatched his sighting report and co-ordinates before heading via Fair Island to Stavanger.

Behind him, Jope left the 5,642-ton SS Gracia sunk, all forty-eight crewmen being rescued, and the 5,559-ton Royal Fleet Auxiliary tanker SS Housatonic still afloat but with its back broken and settling into the sea. Eighty survivors, some injured, one of them critically, were taken aboard HMS Periwinkle, which soon lost contact with the drifting wreck in a snowstorm. Last reported afloat during the course of the following day, the tanker was not seen again.

Alerted by Jope’s radioed report, Dönitz quickly moved available U-boats south of Iceland to intercept, while the Condors continued to attack.

Convoy OB287 was attacked this morning for the third day in succession in the North West Approaches . . . SS [sic] Scottish Standard, St Rosario and D.L. Harper are reported to have been damaged in the attacks today and yesterday. All attacks were made on the flanks or stragglers by single aircraft appearing suddenly from clouds or snowstorms. The escort was quite unable to cover the entire convoy and [HMS] Wanderer reports that continual escort (air) during daylight is essential if similar cases are to be avoided. It had been suggested that ASV [air-to-surface-vessel radar] transmissions might assist enemy aircraft to find convoy, and these were stopped after the dawn attacks this morning with subsequent immunity.10

Both the SS St Rosario and SS Rosenborg had been damaged by bombs on 20 February, the D.L. Harper also being damaged and sustaining a leak in its bunker. The 6,999-ton motor tanker Scottish Standard had been hit by Jope on his return trip to France from Stavanger during the following day, and abandoned by its crew. Jope reported two ships hit, one damaged and the second, estimated at 3,000 tons, destroyed by a hit in the boiler room and subsequent explosion. Jope then circled the convoy and transmitted beacon signals for the benefit of approaching U-boats. In his after-action report he maintained ‘it was possible to calculate the exact position of the convoy by dead reckoning’. However, at B.d.U. it was found that the Focke-Wulfs’ combined navigational reports of the convoy’s location were so vague that U-boats were unable to make contact, and the chase was finally abandoned by the evening of 21 February.11

Greater success was achieved following a sighting report of OB288 south-east of Lousy Bank, made by an Fw 200 returning from Stavanger. The position report enabled U73 to make contact and guide other U-boats, which collectively sank nine ships. Between 25 and 27 February Günther Prien’s U47 made contact with OB290 in the North Channel, and in a reciprocal operation, guided both other U-boats and Fw 200s of I./KG 40 to the convoy, where the Condors sank eight ships. It was a distinct high point in operations by the Condors, but subsequent attempts over the following two weeks to bring U-boats into action against convoy traffic sighted by the Fw 200s failed. The frustration of the situation at B.d.U. can be seen in Dönitz’s War Diary entries:

2 March: One of the two aircraft detailed for reconnaissance to the North returning to Stavanger, reported a convoy at 1030 in AM 2920 (inexact). The course was given as west, only after further enquiry. The position was improved by the report of a bombed steamer in AM 2991. This position was assumed to be correct.

3 March: Aerial reconnaissance saw nothing of the convoy. It is questionable which position the aircraft has in fact reached, with the uncertain fix. It is still possible that the area to the south of the reconnaissance lines is covered. It is also possible that the convoy carried out an evasive movement after the air attack on 2 March, probably followed by one to the north . . . The situation strengthens suspicion to a conviction, that the convoys react to air attacks by greatly altering course — a course which must have seemed obvious to the English, with the development of cooperation between aircraft and U-boat. In this connection, therefore, KG 40 is only to attack isolated vessels; convoys though are to be shadowed unobserved, if possible, and not attacked. A lamentable, but necessary restriction. It remains to be seen how such questions should be decided after the statement of the Fliegerführer Atlantik under C-in-C Luftwaffe. Whether an unobserved shadowing is altogether possible with the large Condor aircraft also remains to be seen.

4 March: The Condor returning from Stavanger reported a convoy putting out in AM 2554, course 3000 at 0900. The composition is the same as that of the convoy of 2 March. It is possible that this is the same convoy, which, owing to the especially unfavourable weather conditions, has been lying practically hove to. The convoy cannot now be reached before darkness . . .

5 March: The reconnaissance lines did not bring any success up to the hours of darkness. Up to now, all attempts to operate on aircraft reports have remained without success (except in the case U73 and U96 on 22 February). The reasons are as follows:

a) Insufficient reliability of aircraft positions. A deviation of 70 nautical miles on 20 February must be attributed to the D/Fing of U96. In addition, it may be suspected that on this, and the days following, the aircraft positions were incorrect, the radio interception reports correct.

b) With the former method, the aircraft reports only gave one position, and the course given might only be that steered at the time.

c) For the most part, the U-boats detailed for operations could not intercept the target until the next day. During this long interval the first report will have decreased in reliability. Also, the uncertainty resulting from this cannot be compensated for, even by the operation of a wide U-boat rake.

Another method of co-operation must therefore be found in order to obtain a more exact position and course of the target from the reports of several U-boats in succession. Until this has been tried out there will be no more U-boat operations undertaken on aircraft reports. In spite of this, aircraft reconnaissance is important in the area not covered by U-boats.

Ordered for KG 40’s operations:

a) Routine flights daily, with at least two aircraft if possible, reconnaissance west and north-west of Ireland.

b) Take off at intervals of one to two hours on the same flying route.

c) Convoys are the target. These are to be reported as quickly as possible (for the time being giving just course and speed). Contact is to be maintained as long as fuel supply allows.

d) The second, and all following aircraft, fly to the convoy reported by the previous aircraft and make their own complete reconnaissance report according to paragraph c). The report of the first aircraft can be checked by that of the second. Each aircraft must therefore report according to his own navigation, regardless of the report sent by his predecessor.

e) Convoys may be attacked until further notice.

Lunch break for the He 115 pilot during the filming of ‘Kampfgeschwader Lützow’. The one-piece summer flight suit (Flieger-kombi für Sommer) manufactured in a heavy brown/white flecked cotton and a long diagonal zip fastener from waist to shoulder was standard issue to Luftwaffe crew. (James Payne)

By March 1941 the aircraft of I./KG 40 had reverted to Luftwaffe control once more. After intense lobbying of OKW by the highest echelons of the Luftwaffe, Hitler issued a new order on 28 February, in which the Luftwaffe was given domain over the lion’s share of naval aviation, stating baldly that there were no plans for the establishment of a separate naval air arm. Although reconnaissance over the North Sea in areas north of 52°, the Skagerrak and exits of the Baltic Sea, and ASW flights between Denmark and Cherbourg remained the preserve of the naval air service, Norwegian coastal reconnaissance and over the North Sea in areas including Shetland, the Orkney and Faroe Islands were to be handled by the Luftwaffe, by a newly created position designated Fliegerführer Nord (Norwegen) (Commander Air North, Norway, subordinate to Luftflotte 5). The Kommodore of KG 26, Oberst Alexander Holle, was appointed to this post in Stavanger, his men of Stab/KG 26 also forming the Fliegerführer staff and leaving KG 26 without a Staff flight. Hermann Bruch was in turn moved from F.d.Luft and appointed Kommandierender General der Deutschen Luftwaffe in Nordnorwegen on 21 April, headquartered in Bardufoss, Norway, acting as Fliegerführer Nordnorwegen. In Bruch’s place as F.d.Luft came Obstlt. Friedrich Schily, pre-war Kommandeur of Küstenfliegergruppe 506.

The English Channel south of 52°N was also made the domain of the Luftwaffe, except for the protection and reconnaissance for convoy traffic. More importantly for Dönitz’s U-boats, control of Atlantic reconnaissance and aerial cover for convoy traffic was transferred firmly to the Luftwaffe once more. However, Göring was ordered by OKW to establish a new post of Fliegerführer Atlantik (Commander Air, Atlantic, subordinate to Luftflotte 3), who would control reconnaissance missions for B.d.U., meteorological flights, support for Kriegsmarine surface forces within the Atlantic and such offensive operations against maritime targets as were agreed between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Hitler also ordered establishment of the post of Fliegerführer Ostsee (Commander Air Baltic) in preparation for the Führer’s cherished Operation Barbarossa and the invasion of the Soviet Union. This new office would provide reconnaissance services for the Kriegsmarine within the Baltic Sea, particularly for BdK (Befehlshaber der Kreuzer, Vizeadmiral Hubert Schmundt), FdM Nord (Führer der Minensuchboote Nord, Kapitän zur See Kurt Böhmer) and FdT (Führer der Torpedoboote, Konteradmiral Hans Bütow based in Helsinki, Finland).

In France, the veteran former naval officer Obstlt. Martin Harlinghausen was appointed Fliegerführer Atlantik, with his headquarters in the grand requisitioned Château de Kerlivio at Brandérion, fourteen kilometres west of Lorient. While the removal of most of the naval air units back to Luftwaffe command was far from ideal for the Kriegsmarine, at least in Harlinghausen they had an efficient and experienced exnaval officer with whom to deal. Dönitz later described him as ‘a man of exceptional energy and boldness’, and the two men endeavoured to create a good working relationship.12 Harlinghausen also articulated to Dönitz the independent operational doctrine with which his command would operate, his two central tasks being the reconnaissance reports locating convoys which could be attacked by U-boats, predominantly the domain of the long-range Fw 200, and attacks by shorter-range aircraft on enemy shipping nearer British coastal waters.

Released in 1941, ‘Kampfgeschwader Lützow’ followed a fictitious bomber squadron in its attack on Poland and subsequent operations against British shipping within the English Channel. The power of cinema propaganda was well harnessed by Joseph Goebbels, serving to both boost civilian morale and attract recruits.

Nonetheless, Raeder gave vent to his extreme disappointment at the reversal of Hitler’s previous decision, and the fact that none of his recommendations had been accommodated at all. Yet, despite a clearly worded memorandum, his last attempt at avoiding the ‘serious limitations and dangers which will result from this for naval operations’ was in vain, and the Luftwaffe reorganisation was undertaken during March. Correspondingly, Raeder saw the writing on the wall for his service, and during 1941 stepped up the channelling of Küstenfliegergruppen naval officers into the U-boat service. By the end of March 1941 most Küstenfliegergruppen had been detached from naval command, and the hierarchy of maritime aerial units changed dramatically once more.

Küstenflieger Command

Gen.d.Lw.b.Ob.d.M. (General der Flieger Hans Ritter)

F.d.Luft (Obstlt. Friedrich Schily)

Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 (Nordeney)

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 (Perleberg), Ju 88

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 (Hörnum), Do 18

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (Nordeney), Do 18

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (Hörnum), BV 138

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 (List), BV 138

1./BFl.Gr. 196 (Wilhelmshaven), Ar 196

Fliegerführer Ost (Aalborg), Obstlt. Axel von Blessingh

Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (Aalborg)

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (Thistedt), He 59, He 115, Ar 196

4.B.Flg.Erg.St. (Thistedt), Ar 196, He 114

Operational Luftwaffe Command Maritime Units

Luftflotte 2, Generfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring

IX.Fliegerkorps

Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 (Schiphol)

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 (Barth), Ju 88

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 (Schiphol), Ju 88

Luftflotte 3, Generfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle

Fliegerführer Atlantik (in co-operation with B.d.U. and MGK West)

I./KG 1 (Amiens-Glisy), He 111

Stab/KG 40 (Rennes), Ju 88 A

I./KG 40 (Bordeaux-Mérignac), Fw 200

3./KG 40 (Bordeaux-Mérignac), Fw 200

4./KG 40 (Bordeaux-Mérignac), He 111

5./KG 40 (Bordeaux-Mérignac), Do 217

III./KG 40 (Brest-Lanveoc) Maj. Walther Herbold, He 111

3.(F)/123 (Aufklärungsgruppe 123), Ju 88, Bf 110

Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 (Do 17Z-2)

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606

Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 (Brest)

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 (Hourtin), He 115

5./BFl.Gr. 196 (Cherbourg), Ar 196

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 (Brest), He 115

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (Brest), He 115

Luftflotte 5, Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff

Fliegerführer Nord (in co-operation with MGK Nord) Generalleutnant Alexander Holle

Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (Stavanger)

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 (Trondheim), Do 18

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 (Stavanger), He 115

1.(F)/120 (Aufklärungsgruppe 120), Ju 88

1.(F)/124 (Aufklärungsgruppe 124), Ju 88

X.Fliegerkorps, General der Flieger Hans Geisler

1./(F) 121 (Catania), Hptm. Arnold Klinkicht, Ju 88D-1

2./(F) 123 (Catania), Oblt. Gerhard Sembritzki, Ju 88D-1

2./KG 4 (Comiso), Oblt. Hermann Kühl, He 111H

5./KG 4 (Catania), Hptm. Heinrich Stallbaum, He 111H

KG 26 ‘Löwen’ (Stavanger-Sola) Oberst. Alexander Holle, He 111H

I./KG 26 (Stavanger-Sola and Aalborg), Obstlt. Hermann Busch, He 111H

II./KG 26 (Comiso), Hptm. Robert Kowalewski, He 111H

III./KG 26 (Le Bourget), Maj. Viktor von Lossberg, He 111H

IV./KG 26 (Lübeck-Blankensee), Maj. Franz Zieman, He 111H, Ju 88 A

KG 30 ‘Adler’ (Eindhoven), Obstlt. Erich Bloedorn, Ju 88A

I./KG 30 (Eindhoven), Hptm. Heinrich Lau, Ju 88A

II./KG 30 (Gilze Rijen), Hptm. Eberhard Roeger, Ju 88A

III./KG 30 (Gerbini), Hptm. Arved Crüger, Ju 88A

IV./KG 30 (Ludwigslust), Maj. Martin Schuman, Ju 88A

LG 1 (Catania), Oberst. Friedrich Karl Knust, Ju 88A-4

I./LG 1 (Krumovo), Hptm. Dipl.Ing. Karl Vehmeyer, Ju 88A-4

II./LG 1 (Catania), Maj. Gerhard Kollewe, Ju 88A-4

III./LG 1 (Catania), Hptm. Bernhard Nietsch, Ju 88A-4

IV./LG 1 (Tronsheim-Vaernes/Bardufoss), Hptm. Erwin Röder, Ju 87B

The most dramatic development, besides nearly all maritime air units being removed from naval control, was the movement of advance elements of Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps to the Mediterranean, Luftflotte 5 assuming direct control of operations in the area vacated by the Fliegerkorps’ departure. The units listed above are Geisler’s maritime strike units; X.Fliegerkorps also included fifty-three Bf 109 and fifty-five Bf 110 fighters, one hundred and sixty-four Ju 87 Stukas and seventysix Ju 52 transport aircraft. The Luftwaffe Mediterranean initiative was in support of Italy’s failing war in North Africa. After months of border skirmishes, on 13 September 1940 four divisions of the Italian Tenth Army based in Cyrenaica, Eastern Libya, had advanced into the British protectorate of the Kingdom of Egypt in Operazione E. The advance initially covered one hundred kilometres in four days, halting at Maktila, near Sidi Barrani. Five fortified encampments were constructed by the Italians as they awaited reinforcements, demonstrating a remarkable lack of offensive momentum. On the night of 7 December a vastly outnumbered British and Commonwealth force, well supported by the RAF and RN, launched Operation Compass, originally envisioned as a five-day limited operation to push the Italians back to the Libyan border, but culminating in the battle of Beda Fomm, which ended on 7 February with the virtual destruction of the Tenth Army.13 The British, led by Gen. Richard O’Connor, had advanced to the shores of the Gulf of Sirte, and stood poised to end the threat of Axis forces in Libya entirely had O’Connor been permitted by his superiors to continue onward and take Tripoli. It was at that moment that Churchill made a monumental blunder and ordered the advance stopped, the captured territory to be held by minimal forces and the bulk of troops redeployed to Greece.

A Dornier Do 18 shot down by British aircraft which filmed its sinking. The lightly armed Dornier proved highly vulnerable to enemy aircraft.

Hitler, on the other hand, ordered a small German land force despatched to Libya, commanded by Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel, his formation named the Deutsches Afrika Korps. Geisler’s incoming Fliegerkorps was on hand to provide support, and his responsibilities had been spelt out in Führer Directive 22, issued on 11 January 1941:

X.Fliegerkorps will continue to operate from Sicily. Its chief task will be to attack British naval forces and British sea communications between the western and eastern Mediterranean.

In addition, by use of intermediate airfields in Tripolitania, conditions will be achieved for immediate support of the Graziani Army Group [Tenth Army] by means of attack on British port facilities and bases on the coast of western Egypt and in Cyrenaica.

The Italian Government will be requested to declare the area between Sicily and the North African coast a closed area, in order to facilitate the task of X.Fliegerkorps and to avoid incidents with neutral shipping.

Geisler’s expanded instructions made X.Fliegerkorps responsible for the initial engagement of Royal Navy fleet units, especially those at Alexandria, attacks on enemy shipping in the Suez Canal (including minelaying) and within the Straits of Sicily, while also preparing for possible deployment against targets in the Ionian and Aegean Seas. Geisler established his headquarters in the San Domenico Palace Hotel at Taormina, a seaside resort town at the foot of Monte Tauro, within sight of the brooding Mount Etna, and was ready for operations by 10 January. During the following day, X.Fliegerkorps had their mission parameters expanded to include attacks on British supply dumps and ports where incoming materials were being offloaded in Cyrenaica and western Egypt. Aircraft were to stage these attacks through forward airfields in Tripolitania in support of scattered Italian ground forces dug in to halt the British advance to Tripoli, which was the planned disembarkation port for Rommel’s troops. During February Geisler’s mission was expanded once more to include flying escort for German troop and supply convoys from the Italian mainland to North African ports. At a time when the Luftwaffe was already being stretched in western Europe, and the shadow of war with the Soviet Union loomed, it had already become involved in the dreaded ‘war on two fronts’.

During January 1941 the airfield at Catania became the principle Luftwaffe base and main terminus for flights to and from North Africa. Among the first X.Fliegerkorps aircraft to arrive were Ju 87s of StG 3, Bf 110s of ZG 26 and bombers of LG 1, KG 4 and KG 26. The Heinkels of Major Helmut Betram’s II./KG 26 spearheaded the deployment of that unit, based initially in Catania before moving to the airfield at Comiso, seventy-seven miles to the south-west and soon to be one of the major staging points for attacks on Malta. Harlinghausen accompanied the KG 26 aircraft to Sicily, and was thus absent from the French office of Fliegerführer Atlantik, while among the new arrivals were Oblt. Josef Saumweber, Helmut Lorenz and Friedrich Müller of 1./KGr.126, who had helped pioneer the use of torpedoes by He 111s while based at Lanveoc-Poulmic. They and their crews, along with two others led by Georg Linge and Rudolf Schmidt, were transferred en masse to 6./KG 26 to become the first cadre of Geschwader torpedo pilots. A torpedo workshop was established at Comiso by technicians attached to 4.Flughafenbetriebskompanie, II./KG 26, equipped with the few airborne torpedoes stockpiled after Göring had petulantly demanded that the six held by Fliegerfuhrer Atlantik and the five with F.d.Luft in Stavanger be given up and flown by Ju 52 to Comiso.

Raeder forcefully argued that the loss of torpedoes for Küstenflieger aircraft rendered naval warfare against Great Britain unsustainable, and in conference with Hitler demanded the release of torpedoes to the Küstenfliegergruppen that were trained in their use, alongside the establishment of He 111 torpedo squadrons to be placed under F.d.Luft command. Striking while the iron was hot, he also pleaded for improved modern reconnaissance aircraft types for assisting U-boat warfare and the increased use of aerial mines off the western English ports, especially in the Firth of Clyde. Hitler merely asked Jodl, as head of OKW, to investigate these requirements, pointedly stating that ‘matters of prestige’ remained outside his decision-making powers. However, on 26 November Göring maintained his order to put a block on the use of aerial torpedoes, instead to be amassed for operations against the British Mediterranean fleet and the ports of Gibraltar and Alexandria, though these two ports were subsequently deemed too shallow for torpedo attack. He also ordered the establishment of his own air torpedo group, raising further objections from Raeder, who once again asked for the torpedo embargo to be lifted, maintaining that Germany could not release its pressure on British coastal convoy traffic in the interest of maintaining the naval blockade. He remained adamant that aerial torpedoes could only be successfully used by specially trained personnel who were, in his view, men from the Kriegsmarine. His objections were, however, overruled.

On 10 January, before the X.Fliegerkorps torpedo aircraft were cleared for service, other units made their Mediterranean combat debut. Convoy traffic bound for Malta from both Gibraltar and Alexandria had converged on the island in the British Operation Excess, both convoys arriving successfully after fighting through unsuccessful Italian air and naval attacks that cost two Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 torpedo aircraft. From the formidable Royal Navy escort forces, only the destroyer HMS Gallant of Force A suffered major damage, when her forward magazine was detonated after striking a mine near Pantellaria, the ship being towed stern-first to Malta with sixty-five crewmen killed and fifteen injured.

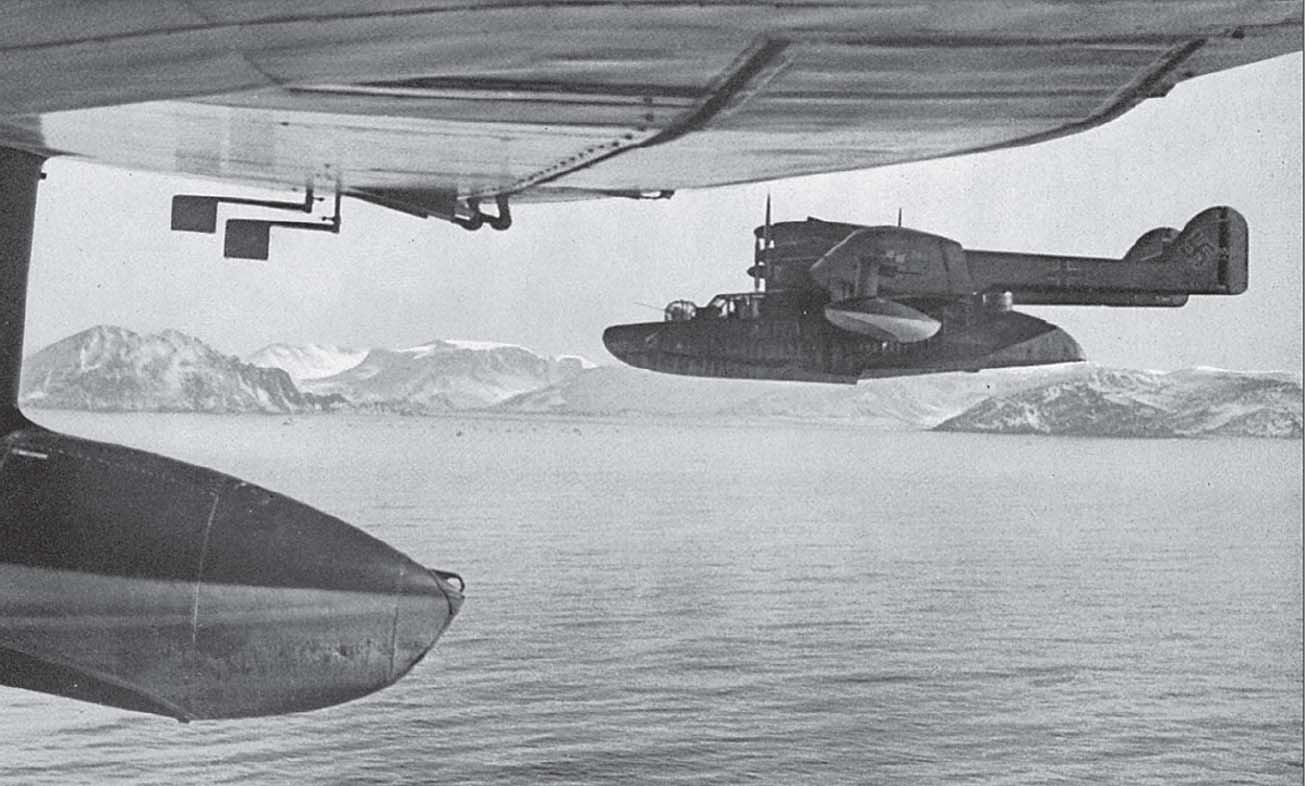

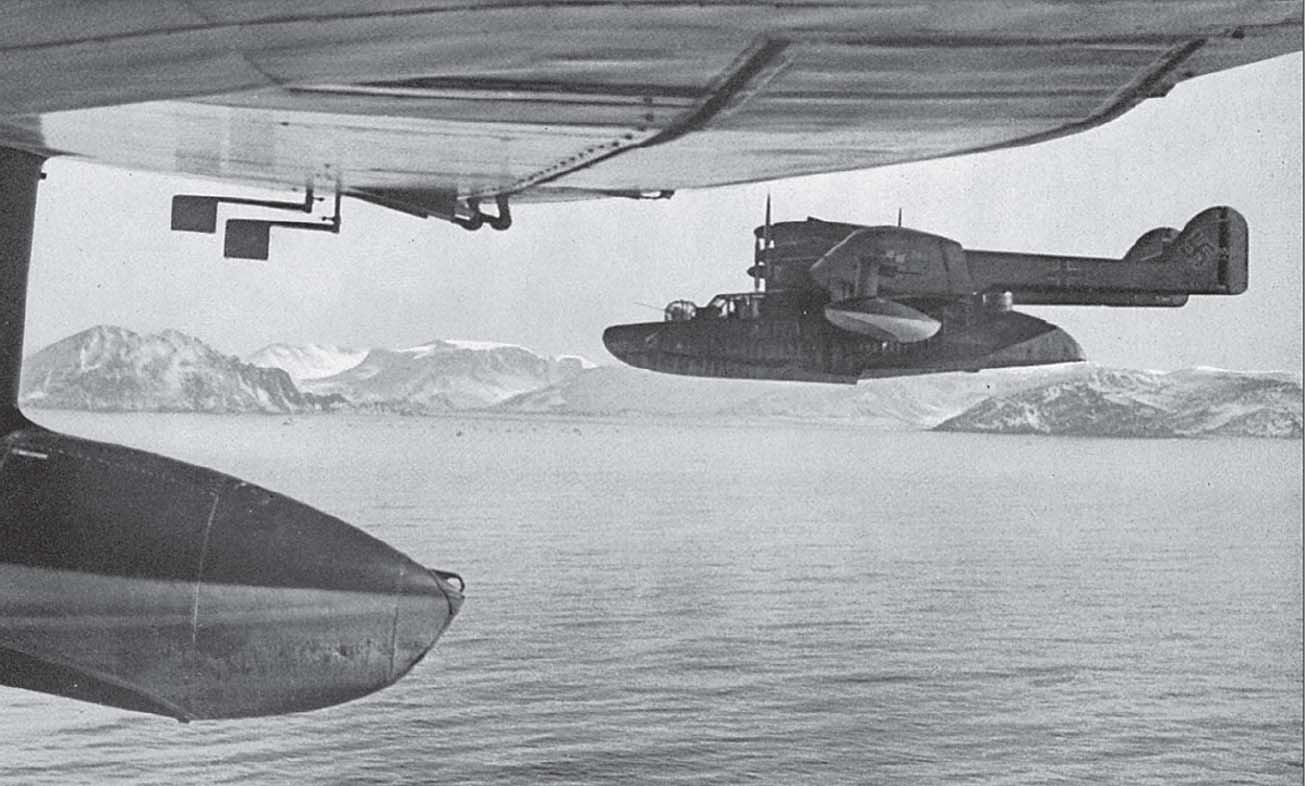

The Blohm & Voss BV 138 was initially beset with design flaws but soon proved a reliable and rugged aircraft, this particular one belonging to Küstenfliegergruppe 706.

However, later that same day X.Fliegerkorps mounted its first successful attack on the ships of Force A, which comprised the battleships HMS Warspite and Valiant, the destroyers HMS Nubian, Mohawk (towing Gallant to Malta), Dainty, Greyhound, Griffin and Jervis, and the carrier HMS Illustrious. Fleet Air Arm Fairey Fulmars from Illustrious shot down a shadowing Italian aircraft, and two torpedoes later launched at low level by SM.79s were dodged by HMS Valiant. However, the Fulmars, which had descended to wave-top level to engage the Italian bombers, were surprised by the arrival of eighteen KG 26 He 111s and forty-three Ju 87s escorted by ten Bf 110s. HMS Illustrious continued launching Fulmar and Swordfish despite being the focus of the German attack, the British crew watching Ju 87s diving from an altitude of 12,000ft. The pilots delayed the release of their bombs to the last moment, bringing their aircraft lower than the height of Illustrious’ funnel as they pulled their Stukas out of the dive. HMS Warspite was lightly damaged by a bomb, and Illustrious was struck by five direct hits and one that failed to explode, as well as a near miss that disabled the rudder. The bombing continued throughout the day, the Luftwaffe being joined by Italian Ju 87s. Lehrgeschwader 1 despatched three Ju 88s against the damaged carrier, but they were intercepted and driven off by Hurricanes from Malta, jettisoned their bombs and turned tail to run. Illustrious finally reached the relative safety of Malta at 2130hrs, with 126 dead and 91 wounded aboard.

Shortly after noon today air attacks commenced on the Battle Fleet, which was covering the westbound convoy into Malta. Dive bombers, high-level bombers and torpedo aircraft were employed. Five of the bombers were Ju 87 with German markings; these attacked with great determination and skill, suggesting German personnel. This was the first really large-scale air attack to which the Fleet had been subjected. Illustrious was hit with six bombs and proceeded to Malta with severe damage and casualties, steering by engine. Sixteen of her aircraft were destroyed, but the remainder landed at Malta. Fulmars shot down six Ju 87s and two S.79s and damaged others.14

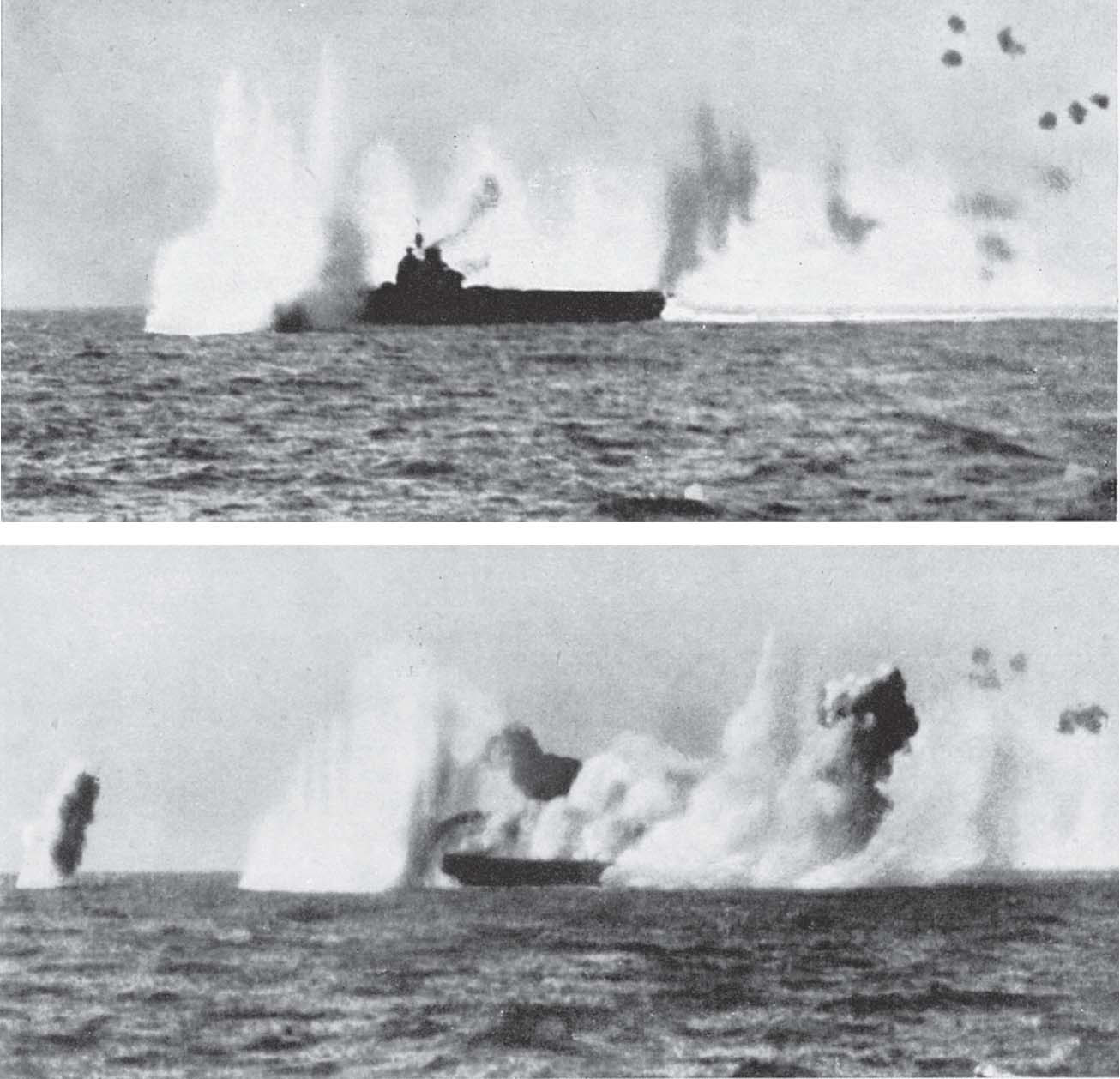

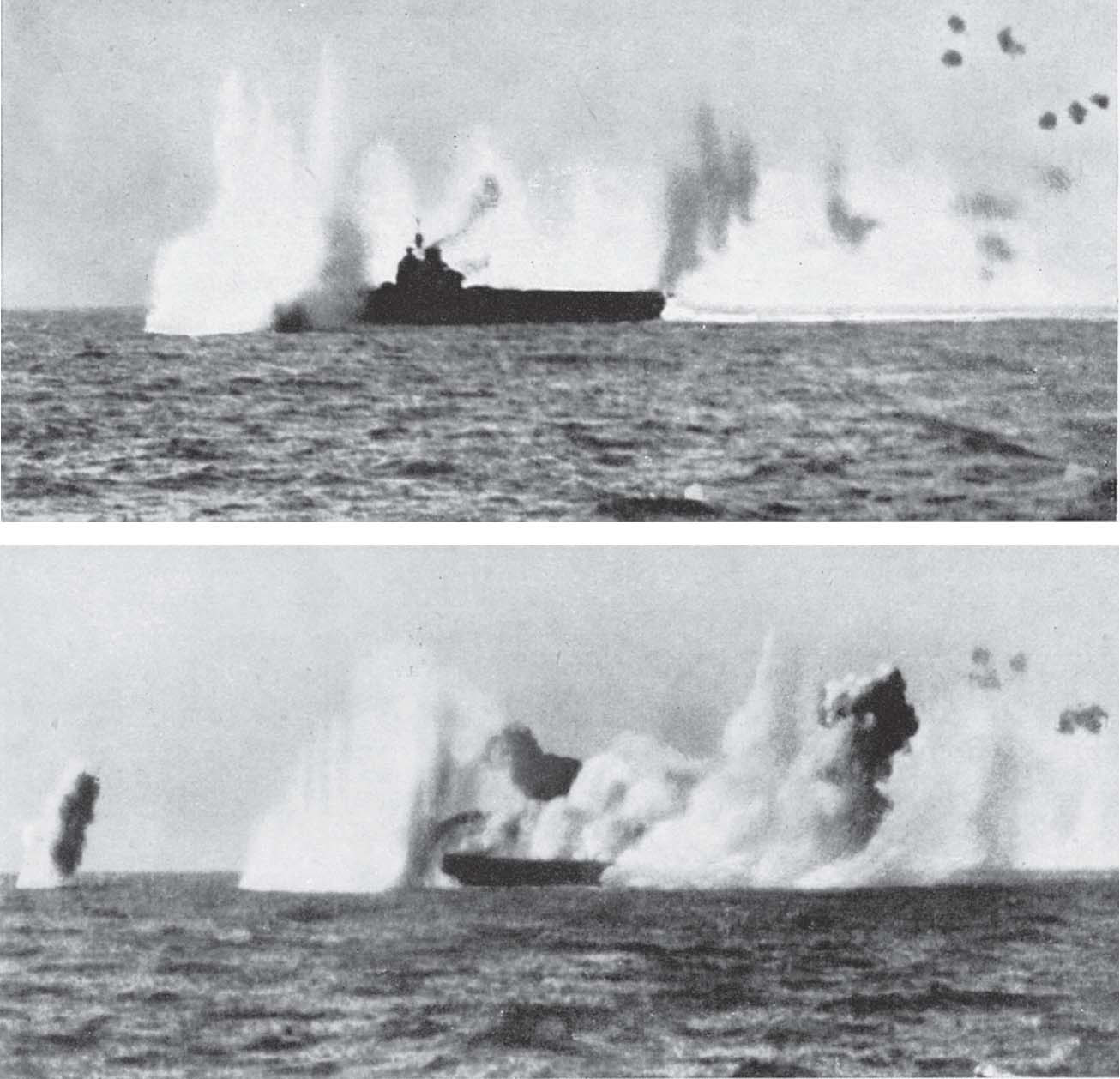

Two photographs that show the devastating attack on HMS Illustrious in January 1941 as the Luftwaffe moved into the Mediterranean.

The German debut had yielded success, but at some cost. In addition, Wellington bombers attacked Catania Airfield on the night of 11 January. Six Heinkels of II./KG.26 were destroyed or damaged, plus two Ju 88s of III./LG 1. Further attacks by the Ju 88s against Illustrious as she lay stationary in Malta’s Grand Harbour failed to inflict further damage, but five German aircraft were lost following the attack on 16 January. One collided with an Italian aircraft and was completely destroyed, two others were written off after serious damage from defending Fulmar fighters and anti-aircraft fire caused them to crash-land back at Catania, one reached the Sicilian coast and crashed near Pozallo after suffering heavy flak damage, and the fifth was shot down by a Fulmar; pilot Oblt. Kurt Pichler, observer Fw. Willi Strauchfuss, radio operator Fw. Heinz Kopecz and gunner Fw. Hermann Busch were all subsequently posted as missing in action.

A Junkers Ju 88 photographed from the ground during the attack on HMS Illustrious in Malta’s Grand Harbour, 16 January 1941. (Leighton John Edward)

Meanwhile, Maj. Helmut Bertram, former Staffelkapitän 5./BFl.Gr. 196 and now Gruppenkommandeur II./KG 26, took part in the first KG 26 raid mounted against the Suez Canal. The new German arrivals hastily assembled an attack against reported convoy traffic, as an early attempt to sink ships within the Canal could, according to Geisler, not only potentially block the vital Allied transit route, but also demonstrate the capabilities of the Luftwaffe both to the enemy and to their Italian ally.

The Regia Aeronautica granted the Luftwaffe use of the airfield at Benina, near Benghazi, as a forward staging post for operations within the eastern Mediterranean and against North African land targets. However, they instantly perceived that little co-operation was forthcoming from their newly arrived allies, a tangible air of assumed superiority accompanying the Luftwaffe into their new battlefield. Two Ju 88s of the reconnaissance Staffel 1.(F)/Aufkl.Gr. 122 landed at Benina at dawn on 15 January, their arrival unannounced to the Italian authorities and counteracting a standing Italian order for daylight operations only from the airfield. The Junkers had been tasked with a reconnaissance sweep of the Suez Canal to locate the convoy for Heinkel bombers that would follow shortly. Nine aircraft from KG 26 flew to Benina the following day, led by Bertram and with Harlinghausen as observer aboard the Heinkel commanded by Hptm. Robert Kowalewski, an ex-Reichsmarine officer and long-term friend of Harlinghausen.15

The Luftwaffe Seetankschiff Clara, one of a small number of tankers launched to supply Luftwaffe maritime bases with fuel rather than compete with the needs of the Kriegsmarine. Clara was constructed under orders from the RLM during 1938 and entered service in 1941 in the Baltic and North Sea.

The two Ju 88s took off at first light to begin their search. In the first, 7A+FH, pilot Obfw. Hermann Peters attempted to take to the air in strong wind, overshot the runway and collided with a parked Italian SM.79 Sparviero bomber. Both aircraft were destroyed, and all four German crew died in the resultant blaze.16 The second Ju 88 fared better, but reported no trace of the convoy before diverting to land on the Italian controlled island of Rhodes to refuel. A third Ju 88 despatched on 17 January also failed to make contact.

Instead, Harlinghausen ordered one of the Heinkels in Benina to be emptied of bombs, and the aircraft subsequently arrived over Alexandria in good weather and reported shipping in the Canal, approaching Suez from the south. The remaining eight Heinkels departed between 1800 and 1830hrs, expecting to return by 0400hrs the following morning. However, the raid was a disaster. Only a single Heinkel returned, commanded by Lt. Werner Kaupisch, who had suffered engine trouble and jettisoned his bombs east of Alexandria. Strong winds caused delays to the other returning aircraft sufficient to cause fuel starvation. While Italian authorities ordered extra airfield lights to be switched on to aid navigation as sand storms began forming over the desert in Marmarica, radio communication was received that two of the seven remaining Heinkels had missed Benina in the abysmal visibility and been forced to ditch. Of the other Heinkels, one crew baled out and the remainder were forced to land. Italian ground forces formed rescue parties to search for survivors.

Harlinghausen had divided the force in two to sweep the waterway’s eastern bank in opposite directions near the reported convoy position. The northbound Heinkels, led by his aircraft, sighting nothing. After reaching Port Said and reversing course they finally detected merchant ships hove-to offshore, though a hurried attack failed and the Heinkel crews faced a daunting return journey at their aircrafts’ maximum range. In violent winds and a blinding sandstorm, Kowalewski was forced to belly-land his fuel-starved bomber in the desert, successfully bringing it to a halt among the endless wind-scoured sand dunes. Harlinghausen, Kowalewski and their crew set fire to the aircraft before beginning the 280-kilometre walk to Benghazi. The blackened remains of the aircraft were sighted by searching Italians after daybreak, but no trace of Harlinghausen or the Heinkel crew was seen. After four days, Lt. Werner Kaupisch, who had joined the hunt in the sole surviving Heinkel, finally found them and landed on the flat sand to pick up the exhausted men and return them to Benina.

Of the other Heinkels that had made emergency landings, three crews were taken prisoner by British and Australian troops, among them Maj. Bertram, who, as commander of the aircraft flown by Lt. Hans Folter, had put down out of fuel to the west of Tobruk. The four-men crew had been captured twenty miles east of Fort Maddalena after a gruelling march in the desert. Bertram was soon replaced in command of II./KG 26 by Kowalewski.17

The German disaster caused some small measure of satisfaction among the Italian officers of V Squadra Aerea (5th Air Fleet), who regarded the Germans as having been difficult and unwilling to accept local knowledge from the regionally experienced Italian airmen. The Luftwaffe operation had been hastily put together and poorly planned and executed. Designed to show German efficiency in action, it had instead betrayed the Luftwaffe pilots as ignorant of desert flying conditions and guilty of overconfidence. The conditions in which the German crews found themselves were completely alien, even for veterans of the fighting in western Europe. On hot days, the temperature inside the glazed cockpits of Luftwaffe bombers could reach 70° Celsius, and, navigating amidst the barren wastes of a desert landscape, the Luftwaffe men had been guilty of recklessness. General Francesco Pricolo, Chief of Staff of the Regia Aeronautica, suggested in a letter to X.Fliegerkorps that:

The incidents that have occurred on this flight are predictable due to the worsening weather conditions, and resulted in painful human losses and material damage, which perhaps could have been prevented if greater contact was made with the local air force commands. They could have provided valuable advice derived from long experience acquired in the particularly difficult desert environment. I wish to communicate the above fact to this Liaison Office, in order to obtain the collaboration between the air forces of the Reich and Italy that is required for every aspect in an evercloser manner with the greatest mutual interest.

Away from the Mediterranean, the Küstenflieger on the Atlantic coast had also suffered losses due to a mixture of enemy action and accidents. On 23 January an He 115B-2 of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 crashed in poor visibility south of Brest, and two days later, over the Bay of Biscay, He 115 M2+KH, under the command of Lt.z.S. Hans-Dieter Fürl, failed to return from its mission, no trace of the aircraft or crew being found. Although its fate remains unknown, three Blenheim VIs of 236 Sqn, Coastal Command, led by Flt Lt Malcolm Robert McArthur, were flying an anti-Condor patrol when they encountered and engaged an He 115, though no ‘kill’ was claimed.

While patrols by the shorter-range aircraft continued relentlessly, Dönitz remained vexed by the lack of successful co-operation between the long-distance aircraft of KG 40 and his U-boats. Aside from the difficulties of untested aircrew over the sea, B.d.U. was also engaged in a tug-of-war over the few available KG 40 units with MGK West, wanting them for scouting for fleet, Sperrbrecher and minesweeping operations. Despite this, the relative success of independent attacks by Fw 200s against merchant ships had clearly registered with the Allies. Churchill’s fear of British strangulation at the hands of U-boats and aircraft was foremost in his thinking during the first half of 1941.

We must take the offensive against the U-boat and the Focke-Wulf wherever we can and whenever we can. The U-boat at sea must be hunted, the U-boat in the building yard or in dock must be bombed. The Focke-Wulf, and other bombers employed against our shipping, must be attacked in the air and in their nests.18

Instructions were issued to Bomber Command on 9 March 1941 to concentrate their main operational effort against targets posing a threat to British merchant shipping. While most of this energy was directed against industrial plants manufacturing U-boat components, construction yards and U-boat harbours themselves, the aircraft of KG 40 were also targetted.

During March 1941 only three merchant ships were sunk by I./KG 40, which, although having twenty-one Condors on strength, could muster an average of only six or seven serviceable machines during the course of the month. The Gruppe had, however, expanded to four Staffeln, three operational and one training, while a further two Gruppen were being formed. In January 4./KG 40, equipped with He 111s and commanded by Hptm. Paul Fischer, became operational, and the following May two further Staffeln were established, flying the Do 217. Fischer’s Heinkels were replaced by Do 217s during June, and the three Dornier Staffeln were brought together as II./KG 40 under the command of Hptm. Wendt Freiherr von Schlippenbach. During March III./KG 40, commanded by Maj. Walter Herbold, was created, flying He 111H-3s owing to the lack of available Condors, but in training at Lüneberg until July, whereupon it transferred to Fliegerführer Atlantik based in Cognac.

The battleship Gneisenau photographed in the North Sea alongside a lowflying He 111. Kriegsmarine-Luftwaffe cooperation seldom reached a level enabling effective inter-service operations.

As part of Bomber Command’s initiative, a bombing raid on Bordeaux-Mérignac by twenty-four Wellingtons on the night of 12 April destroyed two Condors, a pair of He 111s and a Do 215, and badly damaged hangars and airfield buildings. That same night Stavanger-Sola Airfield was also bombed, one Wellington being brought down by ground fire and crashing into the roof of a bakery, where it exploded. This destruction of grounded aircraft was followed by the first Condor confirmed as shot down by an enemy fighter when, on 16 April, Flt Lt Bill Riley’s Bristol Beaufighter of 252 Sqn Coastal Command attacked Oblt. Hermann Richters’s Fw 200C-3, F8+AH, and sent it plunging into the sea in flames off the Irish coast, killing the entire crew. On the following day Oblt. Paul Kalus’ 1./KG 40 Condor, F8+FH, was posted missing, and the body of an airman was washed ashore in the Shetlands over a month later. Yet another Condor was lost when Oblt. Ernst Müller of 3./KG 40 and his crew ditched off Schull Island, County Cork, and were interned. The final casualties of the month were suffered on 29 April, when Oblt. Roland Schelcher of 1./KG 40 was also shot down off the Shetlands by flak from Royal Navy ships, causing the loss of the entire crew. On the balance sheet that no longer favoured the Germans, KG 40 sank eight merchant ships during April.

Increased reconnaissance flights in support of B.d.U., comprising three Fw 200 Condors and three He 111s (4./KG 40) in the air simultaneously, the former from Bordeaux and the latter from Stavanger and Gardemoen Airfield near Oslo, were scheduled to begin from 25 April, but ‘technical difficulties’ delayed their instigation. U-boats had been specifically moved to the area to be covered by the aircraft from Stavanger, but without eyes in the sky they struggled to find the enemy. Furthermore, when the delayed flights began, two days later than originally scheduled, the two Fw 200s spearheading the mission were damaged on their outward passage while attacking a merchant ship, forcing them to break off the action and return to base. They had not followed their briefing instructions to avoid actual combat. The Heinkels completed a journey of over 3,000 kilometres from their Norwegian airfields to land at Vannes, carrying only two 250kg bombs, a route that would be followed repeatedly until July 1941.

However, aerial reconnaissance by I./KG 40 had distinctly failed as far as B.d.U. was concerned. The tenor of his war diary entry for 28 April displayed his opinion of the usefulness of Fliegerführer Atlantik:

U123 made contact at 0106 with an inward-bound convoy in AL 2326 . . . Radio message to U123: attack permitted, continue to shadow . . .

Air reconnaissance was requested for the area in which the convoy had been reported. The aircraft sighted various groups of destroyers and a convoy in AE 8932. It consisted of five ships, strongly escorted, and was inward bound. U143 was informed accordingly. The reconnaissance aircraft did not on the other hand succeed in picking up U123’s convoy, which proves how inadequate a reconnaissance with few aircraft is even against a reported target.

Kapitän zur See Hans-Jurgen Reinecke, Staff Operations Officer in SKL between 1938 and 1941, later charged that a major difficulty in cooperation between U-boats and aircraft was the Luftwaffe’s unwillingness to attack a convoy’s escort and thereby leave the merchants to be torpedoed by U-boats. Göring’s desire for ‘headlines’ led him to send his aircraft in to wage a tonnage war, attacking merchants and frequently scattering a convoy while U-boats were depth-charged by unchecked escort ships and unable to keep pace with the departing merchants. If they had indeed attacked in concert, bombers could have dealt with the escort while the U-boats concentrated on the slower merchants, potentially harvesting a far greater toll than that achieved, even against the hard-hit Arctic convoys.

On the other side of the coin, Fliegerführer Atlantik had also experienced frustration, as on at least one occasion an aircraft transmitted detailed and accurate bearings of convoy traffic while shadowing, only to learn later that B.d.U. had no U-boats within the area at all, a fact of which neither Harlinghausen nor his staff had been made aware.

In the meantime, aircraft of the Küstenflieger and maritime units of the operational Luftwaffe continued to wage war against British shipping within the North Sea. The winter of 1940-41 had been considerably milder than the previous one, and the icy period in which seaplanes could not function had been relatively short. The increased number of Küstenflieger units that had converted to land-based aircraft also rendered them operational within the parameters of normal weather considerations. However, Luftwaffe demands in attacking land-based objectives led to the more frequent use of such maritime units over British soil. Both 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 were used in raids on Britain under the command of 9.Fliegerdivision, and suffered casualties in trained naval aviators. Staffelkapitän Hptm. Walter Holte of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 and his crew were killed on 21 February when their Ju 88A-5 crashed near Noordwijkerhou in The Netherlands during a planned raid on London, and on 14 March another of the Staffel’s Ju 88A-5s was lost during a bombing raid on Glasgow. Oberleutnant Hildebrand Voigtländere-Tetzner’s aircraft was intercepted by Spitfires of 72 Sqn, and its starboard engine erupted in flames when Flt Lt Desmond Sheen attacked in bright moonlight.

As I opened fire I could see my tracer bullets bursting in the Junkers like fireworks . . . when I turned in for my next attack I saw that one of the Hun’s engines was beginning to burn, but just to make quite sure of him I pumped in a lot more bullets, then I had to dive like mad to avoid ramming him.

The Junkers spun into the sea off the Northumberland coast in flames. None of the occupants survived.

Other Küstenflieger crews brought down were luckier. On 17 February Do 17Z-3 7T+JL of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 was shot down near Windsor by American-born Sqn Ldr James ‘Jimmy’ Hayward of 219 Sqn. His unit was operating the first Beaufighter nightfighters when he attacked the Dornier as it returned from bombing London; Lt.z.S. Rolf Dieskau and his crew survived the attack and were captured. Oberstleutnant Joachim Hahn’s Küstenfliegergruppe 606 began to convert to the Ju 88 during early 1941, and was flying the new aircraft operationally by March. Following this conversion, the inevitable shift to full Luftwaffe control that Göring had pursued since July 1940 was completed in May 1941, when Küstenfliegergruppe 606 was officially redesignated Kampfgruppe 606, with an operational strength of sixteen Ju 88s.

With enemy fighter aircraft posing a growing threat to Küstenflieger daylight operations, more missions were planned for the hours of darkness. These, however, not only lowered operational efficiency on all but area-bombing raids, but also did not necessarily make the task any less dangerous. On the night of 18/19 May Hahn’s Ju 88s took part in a raid against convoy traffic reported north-west of Ireland, and lost four aircraft. Hauptmann Rolf Beitzke, Staffelkapitän of 2./KGr. 606, was shot down by flak near Falmouth and crashed into the sea, only the body of gunner Fw. Richard Pape later being washed ashore. Oberleutnant Günther Hitschfeld’s aircraft, 7T+AH, crashed into the top of a hill near Yelverton in Devon, tearing off both propellers and the lower gondola before the shattered Ju 88 careered to a halt in the bottom of a valley. Although the cause of the crash remains unclear, the aircraft’s tailplane had received at least one hit from an 0.303 bullet. Hitschfeld and all three of his crew were killed, their bodies being recovered from the wreckage and interred in Sheepstor Churchyard. Oberleutnant Helmut Eiermann’s Junkers crash-landed at Lannion upon its return, having suffered extensive damage. Eiermann had already survived being shot down during Weserübung, when his Do 17 was hit by flak from a Norwegian MTB on 17 April 1940 and he had forced-landed north-east of Arendal. This time he was not so fortunate. Both he and gunner Gefr. Max Schwarzer were killed in the crash, and the two survivors were both injured. The final loss to Kampfgruppe 606 was Lt.z.S. Werner Neudeck of 2./KGr. 606, whose Ju 88 crashed six kilometres west of Thierry Harcourt after its fuel supply was exhausted. Neudeck was killed and the remaining crew injured, wireless operator Uffz. Heinrich Jänchen later dying of his wounds. A final Ju 88, flown by Oblt. Peter Schnoor of 3./KGr. 606, belly-landed at Lannion, but the aircraft was later repaired and returned to action. In return, Convoy HG61 reported being bombed by German aircraft northwest of Ireland at 0016hrs on 19 May, but suffered no damage.

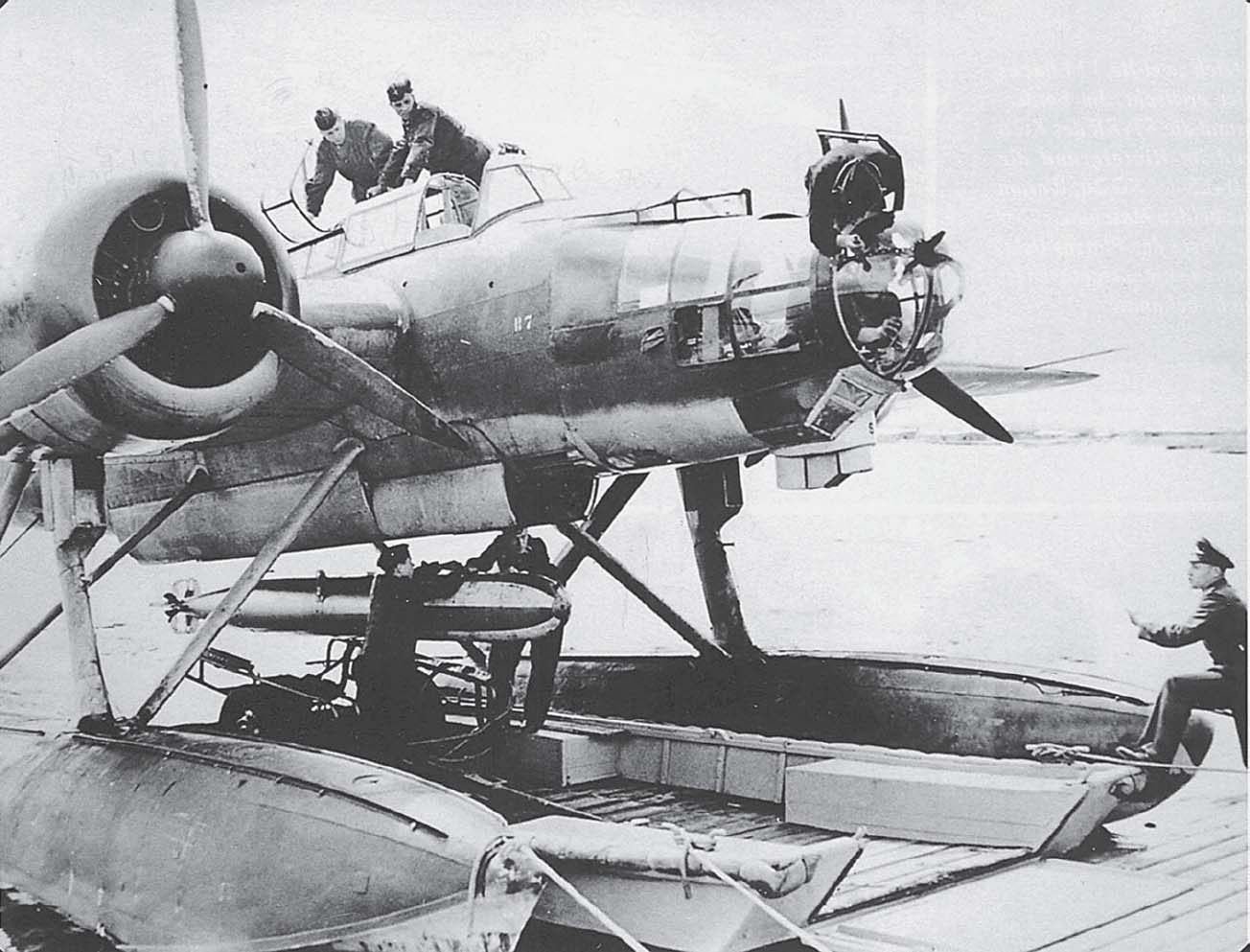

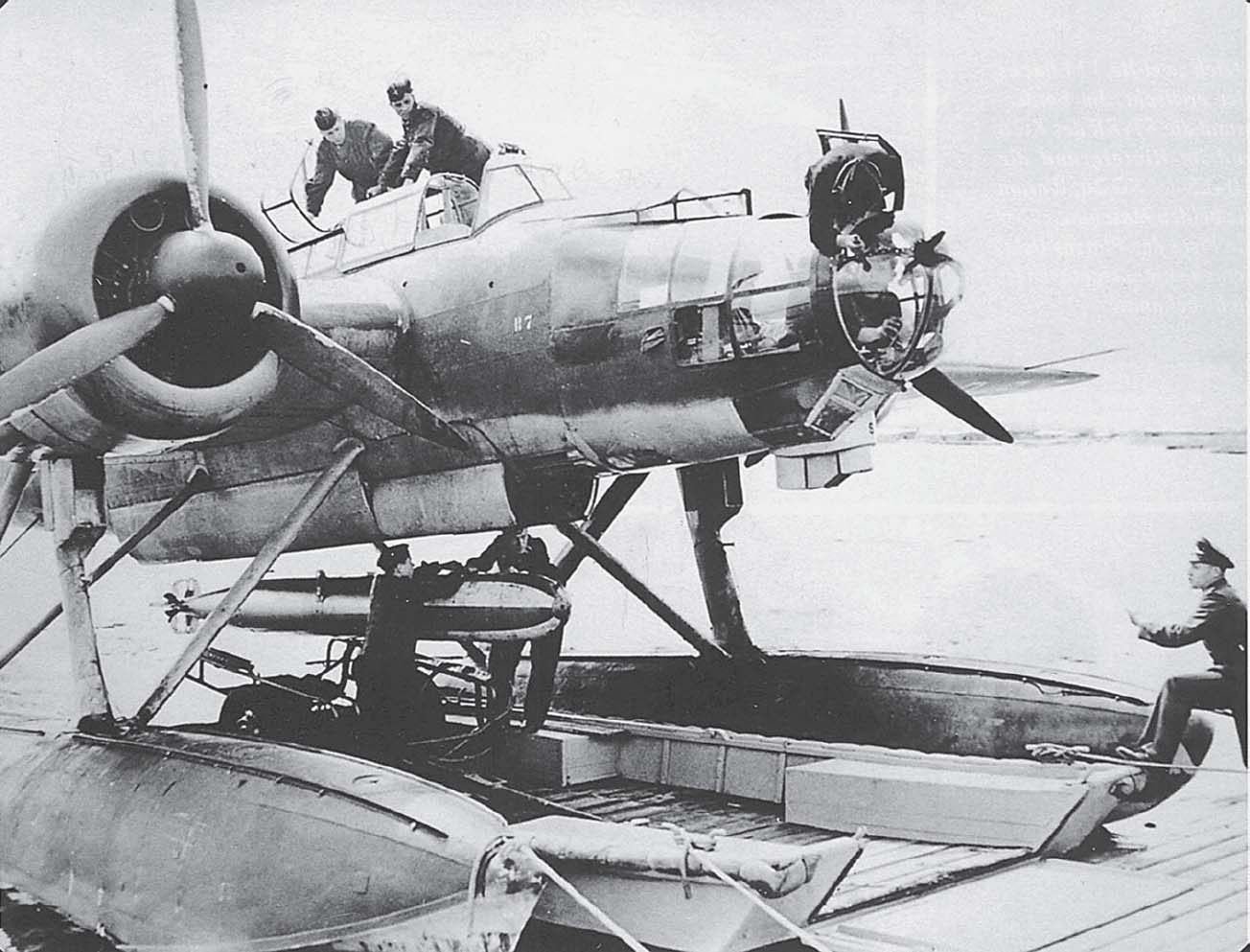

An He 115 being loaded with a practice F5 torpedo, its dummy warhead denoted by the striped paintwork. The bomb bay doors obvious in this photograph allowed internal stowage of the torpedo.

Far to the east during that same day, the battleship Bismarck slipped her moorings at Gotenhafen and headed for the Danish Straits, shepherded by Luftwaffe aircraft including Ju 88s of I. and II./KG 30. Shortly thereafter, the battleship was joined by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. Aboard Kapitän zur See Ernst Lindemann’s Bismarck was Flottenchef (Fleet Commander) Admiral Günther Lütjens and his staff of over sixty men. The two heavy ships were beginning Operation Rheinübung, an Atlantic sortie to pillage the Allied merchant convoy routes. Once beyond the range of Luftwaffe cover they were shadowed by the Royal Navy before they fought the Battle of the Denmark Strait on 24 May, in which HMS Hood was sunk, leaving only three survivors. However, Bismarck had already taken damage during the brief action which forced her to break away from her planned course and head towards France, where the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were already undergoing repairs in Brest Harbour following their own successful raiding voyage. Instead, Bismarck headed for the larger dockyard at Saint-Nazaire. Two large concrete mooring blocks had been built for Bismarck’s use in Brest’s outer harbour, but Saint-Nazaire was the only shipyard capable of accommodating the battleship. Luftlotte 3 was informed of Bismarck’s movement by MGK West at 1600hrs on 24 May, Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle hurriedly reinforcing Fliegerführer Atlantik within two days with extra bomber Gruppen: I./KG 28 in Nantes and the pathfinder force KGr. 100 at Vannes (both He 111), and I./KG 77 (Ju 88), II./KG 54 (He 111) and III./KG 1 (He 111) all based at Lannion. While the Prinz Eugen peeled off to continue the planned raiding voyage, Bismarck was harried by British forces, their pursuit aided by oil leaking from the battleship’s ruptured hull. While Dönitz formed two U-boat patrol lines to set up a potential ambush of the pursuing Home Fleet ships, Göring issued orders on 25 May for Fliegerführer Atlantik to provide the fullest possible support for the incoming Bismarck, and Harlinghausen ordered all aircraft under his command to be brought to immediate readiness. However, though the aircraft numbers available to him were impressive, eventually totalling 218 committed to cover Bismarck, the vast majority of the hastily added units had no experience of maritime warfare and navigation, let alone in the squally weather conditions sweeping across the North Atlantic as a low-pressure front from the north-west bought violent storms.

The Fw 200 Condors of KG 40 became a mainstay of U-boat support work, though not without significant inter-service difficulties.

Condor reconnaissance by a single aircraft of I./KG 40 on 26 May detected HMS Rodney and four destroyers travelling in formation, but sighted no other ships, as the Focke-Wulf was at the absolute limit of its range and only briefly on station. Bereft of air cover at such distance from friendly shores, Bismarck was attacked that same evening by Swordfish of HMS Ark Royal, which attacked with torpedoes between strong rain squalls and disabled the battleship’s steering.

While Bismarck was heading toward destruction, Harlinghausen had allocated three Fw 200s, seven Ju 88 reconnaissance aircraft, forty-two Ju 88 bombers, twenty-nine He 111s and fifteen He 115s to the task of supporting the approaching ship. The Condors, eight Ju 88s and ten He 115s took off on their armed reconnaissance flight in the darkness at 0307hrs, the Fw 200s sighting heavy British forces steaming from Gibraltar to cut off the disabled Bismarck’s retreat. As the aircraft transmitted beacon signals for distant U-boats, B.d.U. was notified of their position. Eight Ju 88s of KGr. 606 took off in the early morning, and five of them were able to detect direction-finding signals that were being steadily transmitted by Bismarck until 0845hrs. An hour later they arrived at the scene of Bismarck’s last stand, as she was engaged by two heavy ships and two lighter units. The Ju 88s delivered a hasty and unsuccessful spoiling attack on a pursuing cruiser, frustrated by ‘Gladiator aircraft’, probably confusing Ark Royal’s Swordfish for the biplane fighter. Unable to outrun or outmanoeuvre its pursuers, Bismarck was finally cornered and sank at 1101hrs, disabled by gunfire and scuttled by the German crew as they abandoned ship.19

During the final battle the Admiralty recorded HMS Cossack and Norfolk coming under attack by ‘land-based aircraft’ from 1000hrs, though the bombers achieved nothing. Within the hour Bismarck had been sunk. Of the crew of 2,221 men, only 114 survived. Eighty-five were rescued by HMS Dorsetshire and twenty-five by HMS Maori, until lookouts aboard Dorsetshire reported sighting a possible periscope and the two British ships broke off their rescue mission and returned to the main body of Force H. Three other men were later found by U74, which arrived at the scene of the battle but had been unable to assist Bismarck in high seas that prevented torpedo use. A German Vorpostenboot later rescued a further two. The Bismarck had carried four Ar 196 aircraft of Bordfliegerkommando 1./BFl.Gr. 196 and their associated crews and technical personnel, numbering four Kriegsmarine observer officers, four NCO pilots and ten technical personnel.20 Of these, only 26-yearold technician Mechanikerobergefreiter Ernst Kadow survived, rescued by HMS Dorsetshire. One of the Arados had been made ready to catapult in the last-ditch defence of the Bismarck, but a torpedo hit below the catapult station had disabled the pressurised air system and the aircraft could not be launched. With the ship moving at speed and waves up to ten metres high it was impossible to lower any aircraft into the water, and the prepared Arado was later pushed overboard into the sea.

Luftwaffe attempts to intercept and attack Force H as it withdrew were unsuccessful, many of the German crews being unfamiliar with nautical navigation and completely failing to locate their targets, while occasional bomb runs mounted by single aircraft missed their mark. A further plan to despatch a concerted attack by 150 bombers at dusk was abandoned, as contact with the Royal Navy force had been lost. It was briefly regained by an He 115 of Küstenfliegergruppe 406, which reported the ships’ course ‘no longer determinable’ in fading light, at the aircraft’s range limit and sailing beneath low cloud through drifting squalls. The following day an Fw 200 regained contact at 0750hrs and sixty-three aircraft mounted staggered attacks on the retreating British. The Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet requested urgent fighter escort, and Hurricanes, Hudsons and Blenheims were rapidly scrambled to assist.21 None had arrived before HMS Norfolk came under attack at 0915hrs and was damaged by splinters from near-misses. HMS Ripley, Tartar and Mashona were also attacked, evading through a combination of full speed and rapid course changes, although the Mashona was hit at 0924hrs by a Heinkel of I./KG 28, the bomb penetrating the port hull abreast of the fore-funnel and exploding in No.1 Boiler Room. Badly holed, the ship listed heavily, and all unnecessary gear was thrown overboard to save her. However, after forty-five minutes the ingress of water could not be stopped, and Mashona’s list increased in the Atlantic swell. The order was given to abandon the destroyer and, during a temporary lull in the air attacks, HMS Tartar picked up survivors before the battered ship was finished off with gunfire from the freshly arrived HMS Sherwood and HMCS St Clair, finally capsizing and sinking. Sid Dobing was aboard the ‘Tribal’-class HMS Mashona when the Luftwaffe attacked.

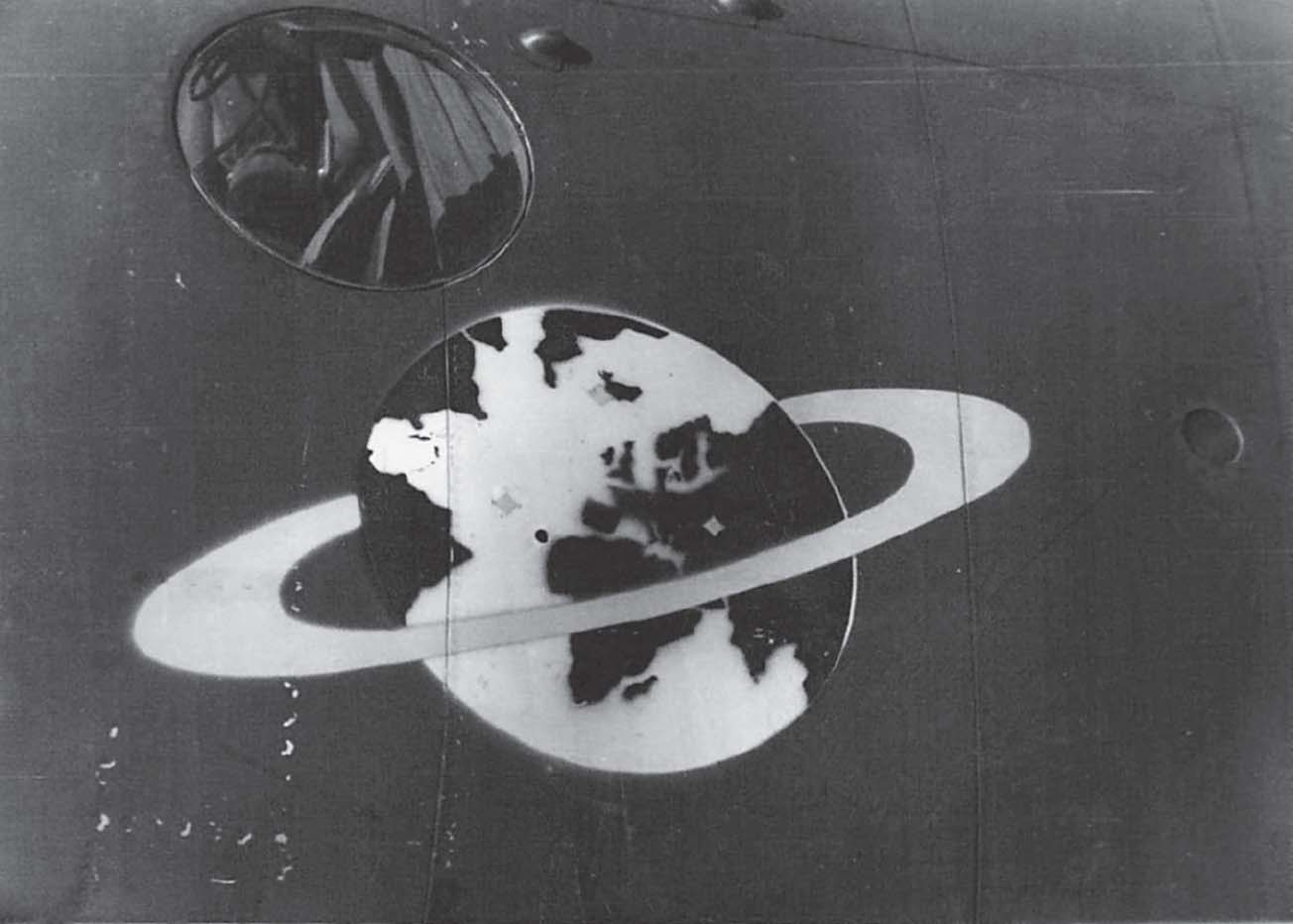

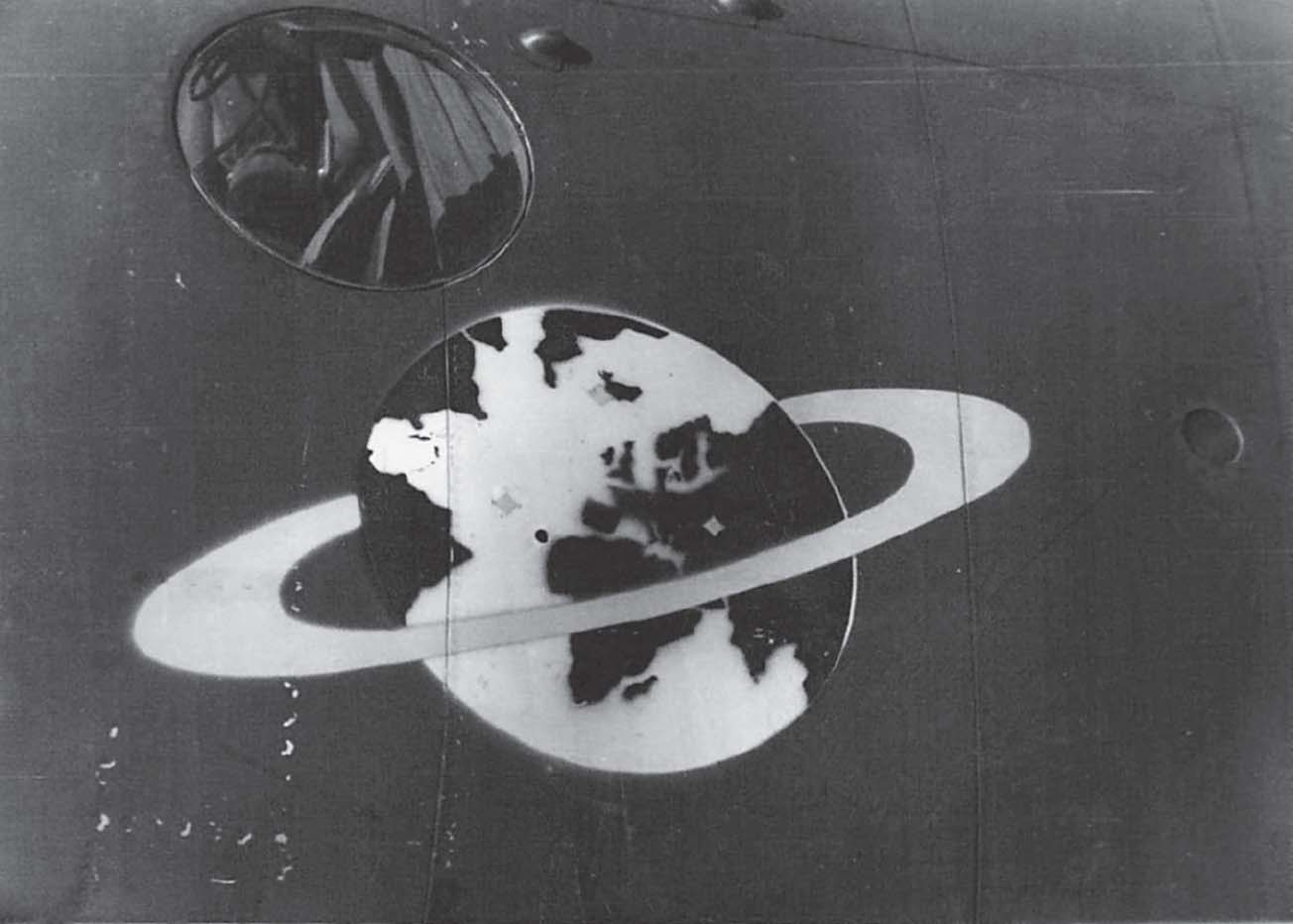

The emblem adopted by KG 40’s long-distance bombers.