Major Arved Crüger, commander of III./KG 30 as it relocated to the Mediterranean.

GENERAL DER FLIEGER HANS Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps continued its raids against Malta, the unsinkable British aircraft carrier from which Axis supply convoys from Italy to Malta were vulnerable to attack. By 12 January X.Fliegerkorps’ Sicilian presence comprised eighty Ju 88A-4 bombers of LG 1 and twelve Ju 88D-5 reconnaissance aircraft at Catania, eighty Ju 87R-1 dive-bombers of StG 1 and StG 2 at Trapani, twenty-seven He 111H-6 torpedo bombers of KG 26 at Comiso and thirty-four Bf 110C-4 fighters of ZG 26 at Palermo. The damaged HMS Illustrious in Valletta’s Grand Harbour remained a priority target, and though the German Ju 87 and Ju 88 dive-bombers made repeated attempts to sink the carrier, they failed. The heavy bombing inflicted further damage on her and surrounding targets, but the toll taken by defending RAF fighters and anti-aircraft guns was severe, over forty aircraft being shot down between 16 and 19 January 1941. HMS Illustrious survived and was eventually able to slip out of harbour and make her way through the Suez Canal to the US Navy repair yard at Norfolk, Virginia. The cruiser HMS Southampton, however, had been sunk on 11 January; heavily damaged by Ju 87s south-east of Malta, she was scuttled by a torpedo from HMS Gloucester, which had also taken several hits.

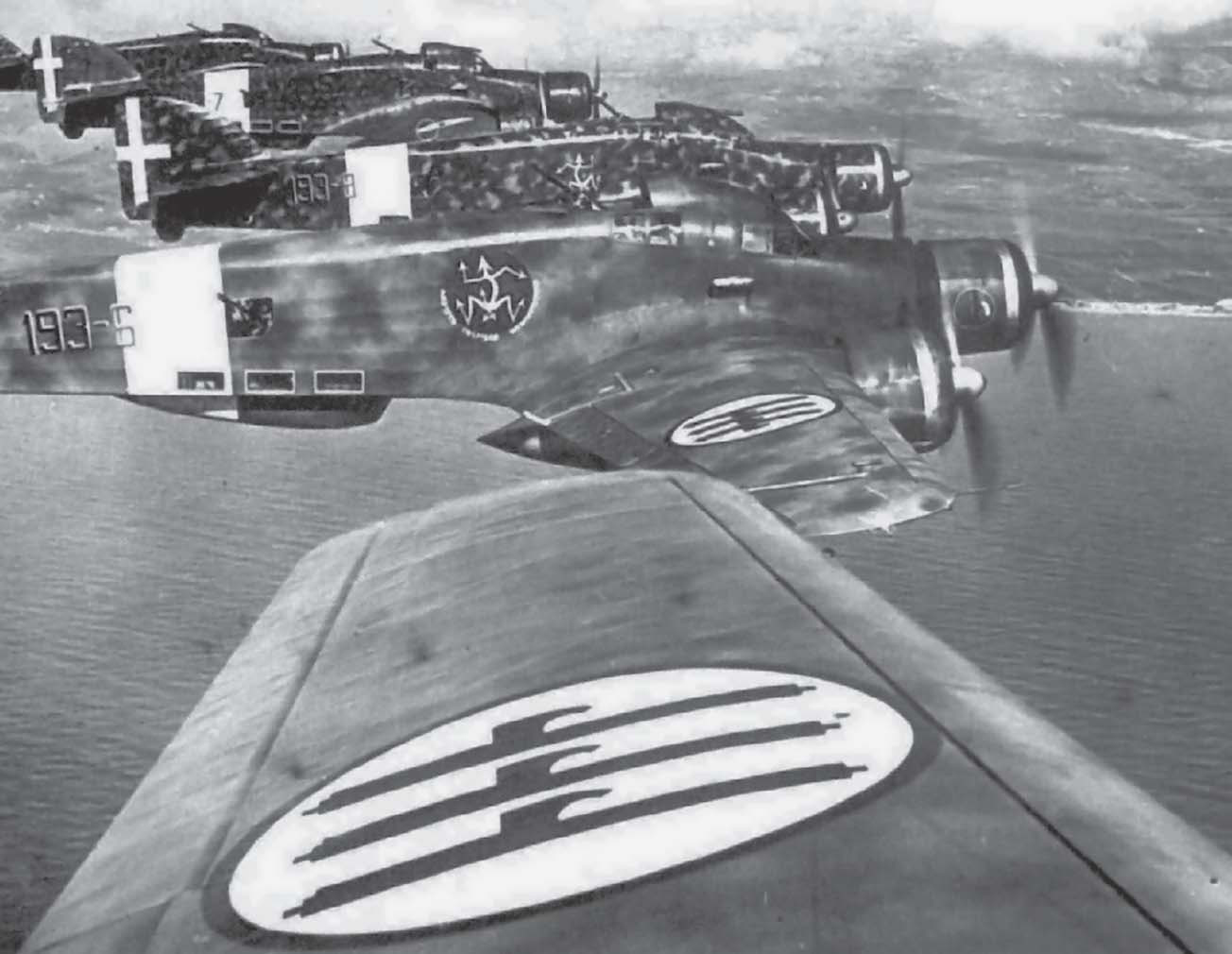

Geisler maintained pressure on the island with all the forces available to him, his bombers and dive-bombers soon coming under the enhanced protection provided by newly arrived Bf 109 fighters. Armed reconnaissance missions were flown along the coasts of Cyrenaica, where, on 19 February, 6./KG 26 suffered its first loss within the Mediterranean when one of the original torpedo bomber pilots, Oblt. Josef Saumweber, flying He 111H-5 1H+MP, was shot down and captured, two of his crew being killed. The mission marked the first use of Luftwaffe torpedo aircraft within the Mediterranean; an unsuccessful attack by sixteen Ju 88s and a torpedo-armed Heinkel Kette on Convoy AC1. The four merchant ships had departed Alexandria, bound for Tobruk and Benghazi, and Saumweber was shot down by heavy antiaircraft fire from the escorting corvette HMS Peony and taken prisoner.

Air-sea rescue for crews forced to ditch in the Mediterranean was the domain of 6.Seenotstaffel, which moved to Syracuse during February, equipped with nine He 59s and Do 24Ns. The rescue aircraft were soon also operating from the Italian seaplane bases at Marsala and Cagliari, and three He 59s were based in Tripoli by April 1941. On 25 February the Ju 88s of 7./KG 30 arrived at Gerbini under the command of Staffelkapitän Oblt. Hans-Joachim ‘Hajo’ Herrmann, who had been awarded the Knight’s Cross on 13 October 1940, during his time as Staffelkapitän of 7./KG 4. The remainder of III./KG 30 followed within the following week, led by Maj. Arved Crüger, who had become Kommandeur during November 1940. ‘Hajo’ Hermann later wrote of Crüger in his autobiography:

Arved Crüger, my Kommandeur, was tall and good-looking, which was why he had been chosen as an aide-de-camp to Emmy Göring [Hermann Göring’s second wife] in Kampen, on the Island of Sylt. We used to joke about him handing her beach robe to her, passing her cooling drinks, until finally it became too much for him and he went to the front . . . [in November 1940]. My Kommodore, Major Bloedorn, became Kommodore of KG 30 and was replaced by . . . Crüger, an excellent pilot, a considerate leader and, above all, a kind man, of whom I was very fond. His leadership was relaxed and informal, but because of the example he set it was positive and conducive of loyalty also.1

By the time of Crüger’s arrival, Herrmann’s Staffel was already in action, subordinated to Oberst. Friedrich-Karl Knust and Stab./LG 1. The newly arrived Ju 88s took part in the heaviest raid on Malta thus far, on 26 February, when every available Luftwaffe bomber hammered the besieged island. The Royal Navy had already been forced to withdraw fleet units from Malta to Alexandria during January, and by the end of March the RAF was no longer able to mount offensive anti-shipping operations from Malta and all bomber units were either withdrawn or destroyed on the ground. It appeared that X.Fliegerkorps had achieved the first of its objectives and asserted domination over the central Mediterranean. Rommel’s gathering forces in Libya could now receive full resupply with little Allied interference.

Despite a disastrous start, missions to the Suez Canal had successfully begun, and aerial minelaying caused periodic closures and resultant delays in Allied shipping of reinforcements and supplies to the Middle East from around the Cape of Good Hope. On 8 May Oblt. Eberhard Stüwe’s Heinkel He 111H-5, 1H+BC, was shot down during a raid on Suez, but he and his crew were successfully rescued by the Seenotdienst and returned to action after ditching at sea. The central Mediterranean convoy route was now regarded by the British as too hazardous until such time as regional RAF and Fleet Air Arm units could be bolstered, and the situation was not helped by having to await the arrival of the carrier HMS Formidable as replacement for the damaged Illustrious. Thus, the Luftwaffe had temporarily tilted the naval balance of power within the Mediterranean. The effect was also felt ashore, despite that Allied defeat of the Italian 10th Army and V Squadra Aerea (5th Air Fleet).

Rather than obey the military maxim of exploiting success, and allowing Allied troops to push on to Tripoli and dispose of Mussolini’s North African empire before Rommel could become established ashore, Churchill had forcefully argued for a diversion of maximum strength to Greece, to which the Greek government agreed on 24 February. The Allies had yet to encounter the forward elements of the Deutsche Afrika Korps, and at that moment denuded their air, naval and ground forces in North Africa by beginning a complex transfer to the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean Sea. Churchill believed that Cyrenaica could be held with minimal forces as a buffer between the Axis and Kingdom of Egypt. Events were to prove him wrong.

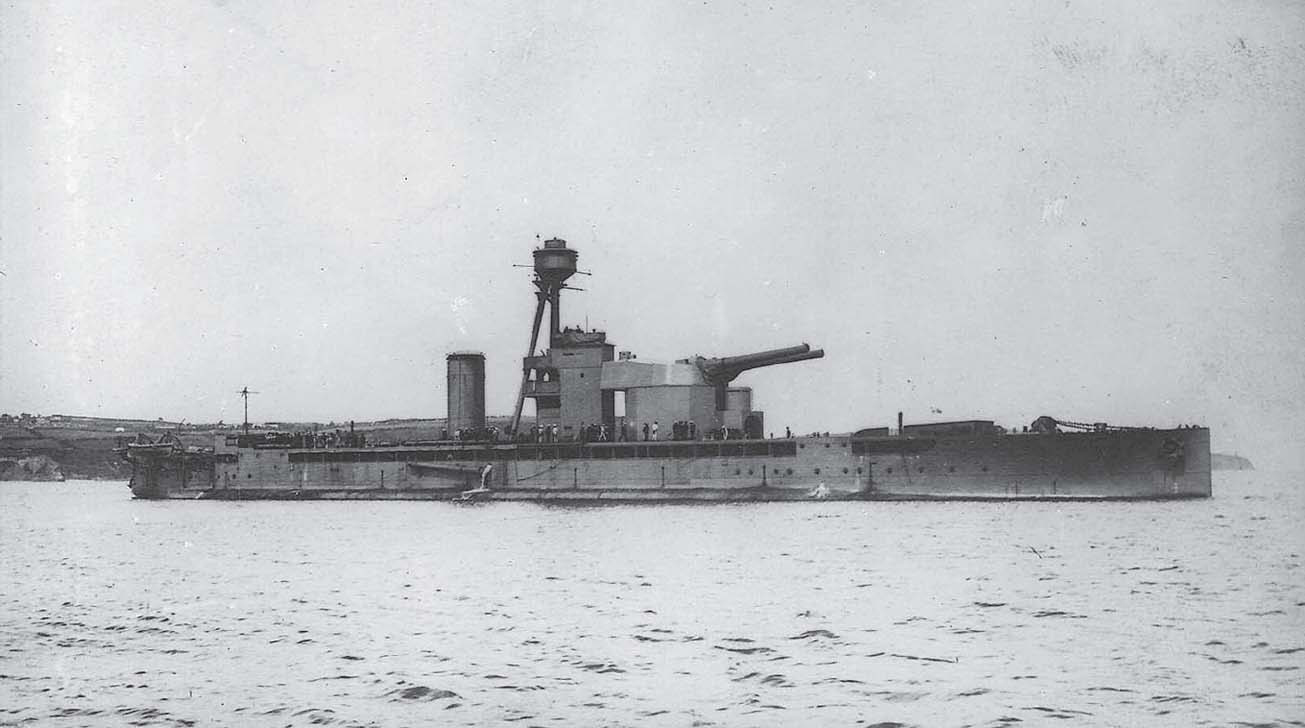

Royal Navy monitor HMS Terror, sunk after damage inflicted by Ju 88s of KG 30 and LG 1 on 23 February 1941, robbing British forces ashore of its bombardment capability that had aided the advances of ‘Operation Compass’.

The harbours at Tobruk and Benghazi, recently captured by the British, came under intense bombardment and mining by X.Fliegerkorps, rendering them virtually useless as maritime transport or supply points. The attacking aircraft frequently refuelled at the well-established Italian Castel-Benito airfield south of Tripoli before their return flights to their Sicilian airfields, while others were beginning to use the Italianoccupied island of Rhodes as a replenishing point. This brought British truck convoys, airfields and troops concentrations into range, and they too came under increasing aerial bombardment. Rommel reached Tripoli on 12 February, ahead of his first combat elements, pushing them immediately into action once they were ashore, supported by elements of X.Fliegerkorps controlled by the newly established Fliegerführer Afrika, the office held by Generalmajor Stefan Fröhlich, former Kommodore of KG 76.2 Although his immediate forces comprised Ju 87 dive-bombers and Bf 110 heavy fighters, he was able to call on the support of the Ju 88s and He 111s when required.

The torpedo-carrying aircraft of KG 26 mounted further operations during February, while Benghazi was frequently raided by the Ju 88s of KG 30 and LG 1, the latter damaging the monitor HMS Terror so badly on 23 February that she later sank while under tow. The 7,300-ton Royal Navy ship had been crucial to the success of Operation Compass, her heavy guns shelling Italian positions during the lightning British advance. Oberleutnant Theodor Hagen, flying L1+GS, claimed to have hit it with two bombs, but in fact both had narrowly missed. Even so, the resulting pressure wave through incompressible water was still enough to fracture the hull, and Terror foundered the following morning. Following the loss of Terror, all Allied ships were withdrawn from Benghazi owing to its inadequate anti-aircraft and fighter protection, reducing front-line supply of British forces solely to overland convoys that straggled to the distant Egyptian border. That same evening the destroyer HMS Dainty was bombed and sunk after leaving Tobruk Harbour during an attack by thirteen Ju 88s of III./LG 1, a single 450kg bomb passing though the captain’s cabin and detonating in the fuel tank. The ensuing blaze spread to stored ammunition, which exploded, killing sixteen crewmen and wounding eighteen before the ship went down. The Luftwaffe had swiftly neutralised the naval support and maritime resupply that had been crucial to the success of the British advance.

In addition, KG 26 flew armed reconnaissance missions to the western Mediterranean, where it is credited with sinking the 3,089-ton British steamer SS Louis Charles Schiaffino, a commandeered freighter formerly of French Algerian ownership. It was hit and sunk by torpedo off the Algerian town of Collo on 25 February by aircraft of II./KG 26, finally signalling the first successful Luftwaffe torpedo operation within the Mediterranean. However, torpedo operations were limited by available stocks, the entire German inventory of aerial torpedoes in March 1941 numbering only thirty-seven. Even so, it was to the eastern Mediterranean that the weight of X.Fliegerkorps was now directed, though ordered to strictly observe the limits of neutral Greek territorial airspace.

From 4 March the bulk of Royal Navy Mediterranean forces were engaged in covering Operation Lustre, the movement of Allied troops from Egypt to the port of Piraeus, Greece, on the outskirts of Athens. Mussolini had begun an ill-advised attempted invasion of the Greek mainland through Albania on 28 October 1940. It was swiftly repulsed, Italian troops being pushed back for months of stagnant winter warfare marked by unsuccessful offensives and counteroffensives. In the meantime, RAF squadrons were despatched to Greece in honour of a declaration of assistance that had been signed in 1939, should Greece be militarily threatened. British infantry also arrived on Crete, enabling local forces to be despatched to the Albanian Front. Churchill had long harboured an obsession with warfare in the Balkans that now spanned both world wars, and, rather than reinforce O’Connor in the desert and bring about an end to Axis power in North Africa, he argued forcefully for the transfer of the bulk of British Mediterranean strength to Greece, this being granted on 22 February 1941.

Hitler was aware of the threat to the Romanian Ploiești oilfields that the RAF now posed, and had already ordered the planning of an invasion of the northern coast of the Aegean Sea, expanded to all of Greece if deemed necessary; Operation Marita. A regular supply from Ploiești was crucial to Germany’s oil reserves, and neighbouring Bulgaria had been pressured into joining the Tripartite Pact on 1 March, allowing the passage of Wehrmacht troops to the Greek border in preparation for Marita, scheduled to begin on 6 April. British regional policy aimed at persuading Turkey and Yugoslavia to join the Allied cause had failed. The Turks remained politically aloof, and Yugoslavia was already under pressure to join the Tripartite Pact, which it finally signed on 25 March. The stage was set for Marita until a group of Serbian nationalist officers overthrew the Yugoslavian government in Belgrade with a coup d’etat on 27 March, subsequently refusing to honour the signed Pact. At first shocked, and then increasingly angry, the Führer hurriedly issued Directive 2 for the Greek invasion plans to be expanded to include a simultaneous attack on Yugoslavia codenamed Operation Strafe (Punishment). Within the Directive, the role of the Luftwaffe was spelt out:

The Luftwaffe will support with two Gruppen the operations of 12th Army and of the assault group now being formed in the Graz area, and will time the weight of its attack to coincide with the operations of the Army. The Hungarian ground organisation can be used for assembly and in action.

The possibility of bringing X.Fliegerkorps into action from Italian bases will be considered. The protection of convoys to Africa must, however, continue to be ensured.

The invasion was still set for 6 April 1941, and major units of X.Fliegerkorps began to shift their attention to the eastern Mediterranean basin in attempts to find and destroy Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy units and convoy traffic of Operation Lustre, which by 2 April had moved the British 1st Armoured Brigade, the 2nd New Zealand Division and the 6th Australian Division from Egypt to Greece. It was planned to bring the 7th Australian Division and Polish Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade as well.

The resultant lull in Luftwaffe pressure on Malta, as Geisler handed responsibility for attacks against the island to the Italian air force, allowed the Royal Navy to create the 14th Destroyer Flotilla, which was based on the besieged island at the beginning of April to restore an offensive naval presence. Subsequent early successes against Axis convoys during that month justified the decision, despite the ships’ vulnerability to Axis air bombardment which, though diminished, continued. The flotilla’s greatest single achievement was the sinking of an entire German supply convoy of five steamers and escorting Italian destroyers off Kerkennah during the early morning of 16 April, for the loss of HMS Mohawk to torpedoes from the Italian destroyer Tarigo.

The Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica war now focused on the east, and on 16 March Hptm. Kowalewski, Gruppenkommandeur of II./KG 26, climbed aboard the torpedo-carrying He 111 flown by Lt. Karl-Heinz Bock of 6./KG 26. In company with a second Heinkel flown by Lt. Rudolf Schmidt, Kowalewski led an armed reconnaissance of the sea area west of Crete, sighting and attacking a Royal Navy group that included the battleships HMS Barham and Valiant. Amidst fierce antiaircraft fire both aircraft dropped their torpedoes perfectly before they were forced to break away out of the range of the enemy guns, claiming two possible but unconfirmed hits on both battleships.

Reported to the Italian Navy, their acceptance of the likelihood that both heavy units had been disabled, and knowledge that HMS Illustrious had been removed from the Mediterranean (without knowing that HMS Formidable had replaced it) contributed to the Italian decision to sail the bulk of the formidable Italian fleet to attack Lustre convoy traffic. The ‘AN’ convoys headed northbound and ‘AS’ southbound, travelling in ballast. The Italian Operation Gaudo was put together following German pressure to mount offensive action against the British shipping between Greece and Egypt, the Supermarina agreeing on the proviso of air support from both the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica. Using one the best-kept secrets of the war, the Allies were forewarned by Enigma decryption, and temporarily suspended Lustre convoying while sailing the British Mediterranean Fleet to engage the enemy. The subsequent battle of Cape Matapan, between 27 and 29 March, was disastrous for the Supermarina. It ended with the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto damaged, three heavy cruisers and two destroyers sunk, and another destroyer heavily damaged before withdrawing. Over 2,300 Italian sailors were killed and 1,105 rescued as prisoners of war, while the Allied forces suffered four light cruisers damaged, two torpedo bombers shot down and three men killed.

A single reconnaissance Ju 88 was sighted as the British recovered survivors, and Admiral Cunningham ordered rescue work curtailed and the fleet withdrawn out of bomber range. A plain-language signal was sent to the Chief of the Italian Naval Staff, advising him of the remaining survivors, estimated to number at least 350, and the hospital ship Gradisca later arrived from Taranto and recovered 160 more shipwrecked men.

Sixteen Ju 88s of III./KG 30 and twelve of II./LG 1 attacked the retreating British, the first sign of the promised Luftwaffe air support, but to little effect. HMS Formidable was narrowly missed by bombs dropped in the face of concentrated anti-aircraft fire. At least one LG 1 Ju 88 was brought down by Fulmars of 803 Sqn, Uffz. Georg Kunz’s L1+EP of 6./LG 1 crashing into the sea, but not before gunner Gefr. Josef Leitermann hit the Fulmar piloted by Sub-Lt A.C. Wallace with return fire, causing enough damage to force it too to ditch into the sea after a failed attempt to land on the carrier’s deck. Both Wallace and Leading Airman F.P. Dooley were rescued by the destroyer HMS Hasty. Kunz, Leitermann, observer Gefr. Fritz Schmidt and wireless operator Uffz. Walter Fischer were likewise rescued, and taken prisoner. Leutnant Alfred PIetch of KG 30 was also brought down, his Ju 88 caught by a Fulmar fighter as it pulled out of its dive and ditching several kilometres from the scene. His location was fixed by ‘Hajo’ Herrmann as the Staffelkapitän flew his aircraft to Benghazi for refuelling, and the crew were later rescued from their dinghy by a Seenotstaffel aircraft.

Major Arved Crüger, leading III./KG 30, claimed three hits on HMS Formidable, which was reported during the following day’s Wehrmachtberichte:

Combat aircraft under the command of Major Crüger successfully attacked a strong English naval force in the afternoon hours of 29 March in the sea area west of Crete. Despite fierce flak and fighter interception they obtained three direct hits on an aircraft carrier. During the air attack a British Hurricane fighter was shot down. All of our aircraft returned to their base.

In recognition of this perceived victory, Crüger was awarded honorary Italian pilot’s wings during April for his service in support of Italian naval forces.

While Matapan had been an unmitigated disaster for the Italian navy, and the desultory retaliation by X.Fliegerkorps achieved nothing, the cumulative effect of constant Luftwaffe missions in the eastern Mediterranean was being felt within the British Admiralty, yielding several claims of merchant ships sunk.

Scale of air attack in Mediterranean is increasing very rapidly. Yesterday AS22 was twice attacked once by as many as thirty Ju 88s. Would it be possible to spare the two heavily armed escort ships Flamingo and Auckland from Red Sea Force?3

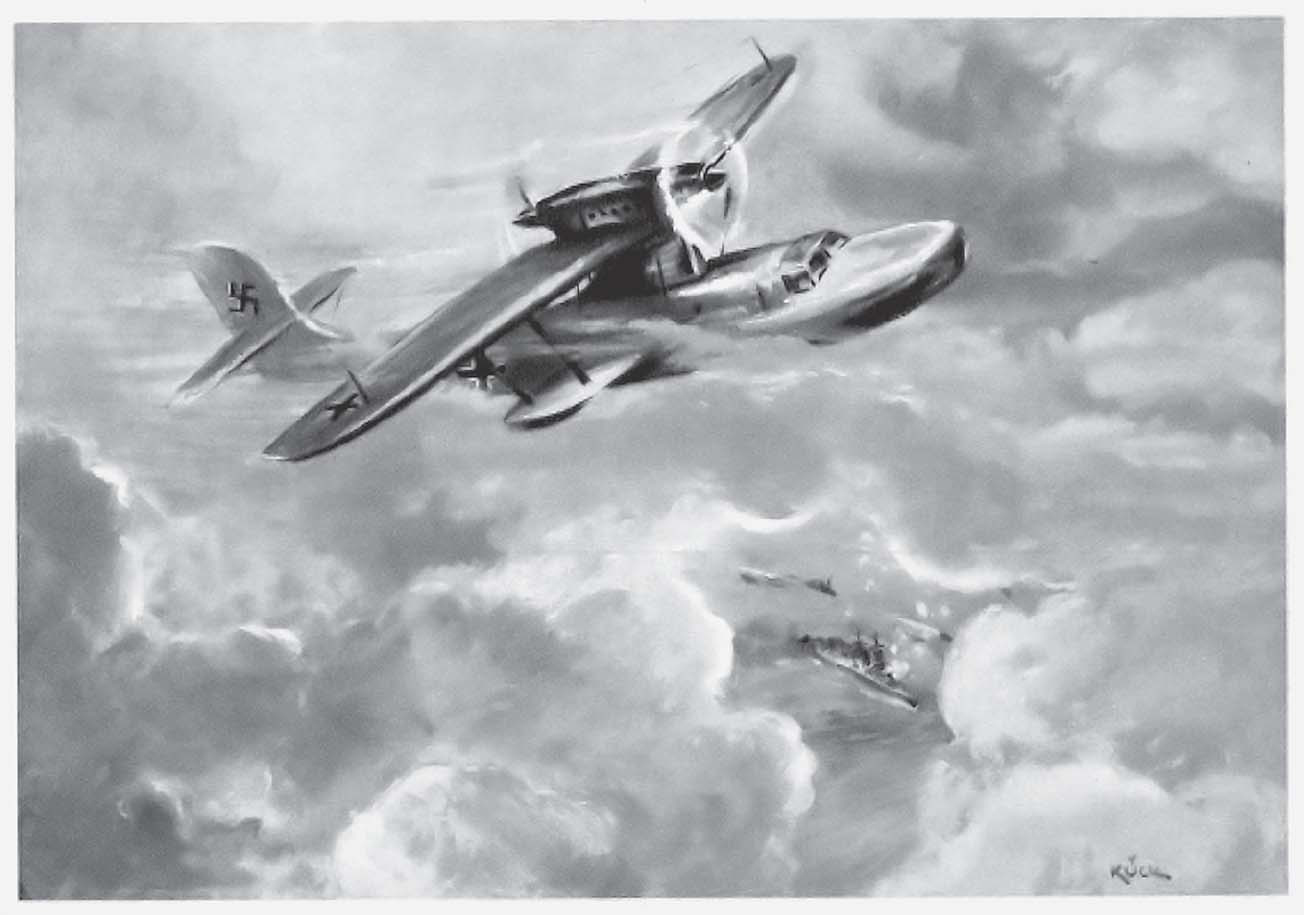

Wartime postcard depicting a successful Do 18 reconnaissance mission.

On 2 April Hptm. Joachim Helbig’s eight Ju 88s of 4./LG 1 attacked convoy AS23 off Gavdo Island, damaging the Greek SS Teti and sinking the 5,324-ton British SS Homefield and 4,914-ton Greek Coulouras Xenos. Salvage parties boarded the two latter ships, but they were both hopelessly wrecked and subsequently scuttled by explosives and gunfire from HMS Nubian from the escort of fast convoy ANF24. This convoy was also attacked twice, the steamer SS Devis being damaged during the first dive-bombing attack by Hptm. Kollewe’s II./LG 1, and on 3 April the 10,917-ton liner MV Northern Prince, carrying ammunition and several thousand tons of powder from Britain for Greek munitions factories, was sunk in the Antikithera Channel north-west of Crete. The ship had taken two direct hits amidships, and began to belch thick smoke as the crew scrambled to abandon ship, fearing the sympathetic detonation of the lethal cargo. Ten minutes later the requisitioned Atlantic liner exploded.

Despite this success, the losses to ‘AN’ convoys were relatively minor, and the planned transfer of men and material from Egypt was successfully completed, setting the stage for the impending battle for Yugoslavia and Greece. Heinkel bombers of II./KG 26 were moved to Foggia Airfield during April, while the Ju 88s of II. and III./LG 1 relocated temporarily from Catania to Grottaglie, fourteen kilometres east-north-east of Taranto, committed to the attack on Yugoslavia and the bombing of land targets. This left Crüger’s III./KG 30 as the sole Gruppe on Sicily, and when Operation Marita opened on the night of 6/7 April, Crüger’s initial target was the Greek harbour at Piraeus, the country’s largest port, which had been used for the transfer of troops during Operation Lustre and was still filled with shipping.

Crüger’s Ju 88s carried a mixed load of mines and bombs. ‘Hajo’ Herrmann later wrote that the assigned weapon load was two mines to each aircraft, but unofficially he took it upon himself to add two 250kg bombs to each of his 7.Staffel bomber’s load. Crüger apparently found the unorthodox weapons load while making a last-minute inspection, and instructed them to be removed, wryly commenting to his subordinate: ‘And try and look a bit happier next time!’ Herrmann gave the order, but, after Crüger had departed, managed to ensure that it was not obeyed. Following take-off, bad weather forced some 8.Staffel aircraft to jettison their mines, as they suffered severe icing while attempting to fly above a Greek mountain range, the clogging ice making it imperative that the aircraft’s weight was immediately reduced. Despite this, most aircraft of KG 30 successfully laid mines across the narrow harbour entrance, Herrmann electing to begin his Staffel’s minelaying run from landward, throttling back to a little above stalling speed and deploying dive brakes before dropping, violently nose-up, to only 300m altitude before the mines were released, whereupon full throttle brought the aircraft back under control and they headed away from the enclosed harbour mouth. Once the mines had been dropped, Herrmann’s Staffel gained height and returned to drop their bombs, beginning the destruction of the port. Their effectiveness was far in excess of what the Luftwaffe had expected. Royal Australian Navy Able Seaman Patrick Bridges was aboard corvette HMS Hyacinth in Piraeus Harbour as the attack developed, and wrote of it in his diary:

Hans-Joachim ‘Hajo’ Herrmann of KG 30.

Sunday April 6, 1941: Mass air attack here tonight. Hit one ship full of TNT, which burnt for four hours then blew up. A sheet of the ship’s side tore through our bridge and killed Lt [Ronald] Humphrey. Ship broke away from the jetty and we had to abandon it. We pulled it back and tied up and then ran the gauntlet through blazing oil and burning ships and magnetic mines with only half a ship’s company.

Monday April 7, 1941: Piraeus is still burning furiously. Sky is black with oil smoke and ammunition and dynamite is still exploding. Both our skiffs are holed. Bridge and boat deck are either wrecked or burnt. Great lumps of steel and shrapnel all over the deck. Drifting wreckage all over harbour. One plane came over to see damage . . . Waiting for raiders now.4

Piraeus harbour after attack by KG 30. At right of this photograph is the burning SS Clan Fraser. The subsequent explosion of its stored TNT cargo sank many other vessels and rendered the harbour unusable by Allied forces for ten days. (Australian War Memorial)

The 7,529-ton SS Clan Fraser was carrying 350 tons of TNT, and a further 100 tons was aboard a lighter moored next to the cargo ship, when three of Herrmann’s unauthorised bombs hit Clan Fraser; one forward, one amidships and one aft. Six crew members were killed and nine wounded as the survivors evacuated the ship. The battered freighter could not be towed from port owing to the danger posed by the new mines strewn across the harbour entrance. The ship burned for five hours, its hull glowing red from bulwarks to waterline, before finally exploding, devastating the entire port and shaking buildings and shattering windows fifteen miles inland in Athens. The sound of the blast was heard as far as 150 miles from Piraeus. Following the initial explosion, fires spread rapidly to other merchant ships, including a second steamer loaded with ammunition, the SS City of Roubaix, which also detonated in a massive fireball, turning the harbour into an uncontrollable inferno. In total, twelve large merchant ships and at least fifty smaller craft were destroyed. Harbour installations and seven of the twelve berths were so severely damaged that Piraeus was completely unusable for ten days, robbing the Allies of the regional port most suitable for large vessels. More than twenty merchant ships in bays adjacent to Piraeus were stranded, as they had been moored awaiting coal and water, and were rendered vulnerable to the air attacks that would soon follow. The Luftwaffe suffered no casualties, though Herrmann’s Junkers was hit by anti-aircraft fire that damaged the port engine and forced an emergency diversion to Rhodes, rather than the longer return to Sicily.

While the majority of X.Fliegerkorps assets were subsequently engaged in supporting the land offensive in Greece and Yugoslavia, Piraeus and its environs, as well as the port city of Volos, were attacked again by bombers of LG 1, III./KG 30 and II./KG 26, sinking further ships. They included the 2,561-ton Greek hospital ship Attiki, which went down in the Doro Channel (the first of six hospital ships sunk by the Luftwaffe during April), and the 8,271-ton MT Marie Maersk at Piraeus, the tanker later being raised and repaired by the Regia Marina.

Disaster soon overwhelmed the Allied Expeditionary Force that had been landed in Greece. Outnumbered and outmanoeuvred by the Wehrmacht, the Allies were pushed steadily back, while Yugoslavia had crumbled almost immediately, surrendering on 17 April. The previous day, the British had bowed to the inevitable and decided to abandon Greece, the seaborne evacuation being codenamed Operation Demon. At that moment in North Africa, Rommel had been on the offensive since 24 March, eventually pushing the inexperienced forces that had been left to hold Cyrenaica back to the Egyptian border, from where O’Connor had launched his brilliant attack a year earlier. The troops that were sorely missed in Libya after being moved to Greece now found themselves in another Dunkirk-style evacuation, made more difficult by Hermann’s devastating success at Piraeus. Beaches and smaller ports were used as embarkation points, small naval vessels and local craft being used to shuttle waiting troops to merchant and naval ships lying stationary offshore. It proved to be a boon to the Luftwaffe, who subsequently attacked without respite, the maritime strike aircraft reinforced by Ju 88 bombers of KG 51 and Stukas of St.G. 1 and 2.5

Almost unbelievably, the British evacuation was remarkably successful; 50,732 men, including some Greek and Yugoslavian troops, were successfully lifted from the Greek mainland between 24 April and 1 May. However, four major troopships were sunk by German air attack: the 3,791-ton MV Ulster Prince, 16,322-ton SS Pennland, 11,406-ton SS Slamat and 8,085-ton SS Costa Rica, as well as the destroyers HMS Diamond and Wryneck and myriad smaller ships. Churchill’s misdirected folly had cost British and Commonwealth forces 12,000 men killed, wounded or missing, and 209 aircraft, 8,000 trucks and all of the Expeditionary Force’s armour and artillery were destroyed, along with mountains of stores and supplies. It had also cost the recently conquered portion of Libya, putting Allied forces once again with their backs to the Egyptian border. Nor was that the end of the calamity overtaking Allied Mediterranean forces.

With mainland Greece and the Aegean Islands now in Axis hands, Crete remained the single Allied possession before the shores of North Africa. The island was defended by only six RAF Hurricanes and seventeen other largely obsolete aircraft, including Gladiators and Fulmars, giving the Luftwaffe virtually complete dominance and enabling the launch of the largest airborne assault yet undertaken; Operation Merkur on 20 May. Commanding the Luftwaffe presence over Crete was General der Flieger Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen’s VIII.Fliegerkorps. Von Richthofen, cousin of the First World War flying aces Manfred and Lothar, had served as a pilot during that conflict, and after joining the new Luftwaffe in 1933 had been a direct subordinate to Ernst Udet in the Technisches Amt (Technical Development Section), with whom he did not get along. Arrogant to the point of bluntness, the conceited von Richthofen became one of the Luftwaffe’s most gifted officers, serving in the Condor Legion, where his once avowed aversion to dive-bombers was thoroughly altered. He became one of the foremost exponents of close air co-operation with ground forces, though he frequently showed little interest in, if not disdain for, Luftwaffe maritime operations. Following his return to Germany during 1938 he had been Geschwaderkommodore of KG 257, later redesignated KG 26, at its home base of Lüneburg.

Oberst Knust’s LG 1 was transferred to von Richthofen’s VIII. Fliegerkorps, I and II Gruppen being deployed to the recently captured Eleusis Airfield near Athens, while III./LG I remained at Benina near Benghazi, from where it supported Rommel’s troops during their advance. Knust also took control of the nine serviceable torpedo bombers of Hptm. Kowalewski’s II./KG 26, though by the launch of Merkur he had been replaced as Kommandeur by Obstlt. Horst Beyling.

The reality of maritime patrols for bomber crews of all nations; the observer aboard and He 111 scouring the horizon for elusive enemy shipping.

Von Richthofen’s available strength return at the beginning of May listed:

StG 2: three Gruppen totalling seventy-one Ju 87s;

LG 1: two Gruppen totalling forty-two Ju 88s;

II./KG 26: of nine He 111s;

KG 2: three Gruppen totalling seventy-seven Do 17s;

JG 77: three Gruppen totalling sixty-one Bf 109s;

ZG 26: three Gruppen totalling fifty-six Bf 110s;

7./LG 2: of four Bf 110s;

4.(F)/Aufkl.Gr. 121: of five Ju 88s.

By 23 May these were reinforced by sixty-five more Ju 87 dive-bombers of StG 1 and StG 77. During the days preceding the opening of Merkur the heavy cruiser HMS York, which had been disabled by Italian explosive motorboats in Crete’s Suda Bay, came under intense bombardment by VIII.Fliegerkorps. She was hit several times by dive-bombing Ju 88s of LG 1, and was later wrecked by demolition charges before the British evacuation.

The torpedo bombers of II./KG 26 launched a number of attempted attacks during the battle for Crete, using the last six operational torpedoes available to them, though none were successful. The sole aircraft torpedo sinkings were achieved by the SM.79s of the Italian 281st Squadriglia. Instead, the Heinkels were more successful with conventional bomb loads, adding their weight to attacks against the Royal Navy north-east of Crete. The Ju 88s of KG 30 were also heavily involved in the attack on shipping around the embattled island, joining LG 1 and the Dornier Do 17s of KG 2 on 22 May in relentless bombing of the Royal Navy Force C of four cruisers and three destroyers that was attacking a seaborne German reinforcement convoy south of the island of Milo, badly damaging HMS Naiad and Carlisle. To reinforce Fallschirmjäger forces on Crete, the Germans despatched convoys of small vessels carrying Gebirgsjäger, immensely vulnerable to enemy naval forces. As the sole escorting Italian torpedo boat Sagittario bravely mounted a torpedo attack while laying smoke, the Luftwaffe pounded the attacking Royal Navy ships, allowing most of the German convoy to retreat successfully. Force C itself was already running short of anti-aircraft ammunition, and under unrelenting attack was forced to break away to rendezvous with the formidable Force A, commanded by Rear Admiral H.B. Rawlings and centred on the battleships HMS Warspite and Valiant, as well as two cruisers and the attached Force D of three cruisers and four destroyers. The ships made contact in the Kythera Channel, where the Luftwaffe found them once more, HMS Warspite being hit by a bomb dropped by a Bf 109 of LG 2 while the destroyer HMS Greyhound was hit twice and sunk. HMS Kandahar and Kingston were despatched to its assistance, the cruisers Gloucester and Fiji providing anti-aircraft support despite running low on ammunition. The commander of Fiji later told Admiral Cunningham that the ‘air over Gloucester was black with’planes’, and Gloucester was hit by several bombs at 1550hrs after exhausting her anti-aircraft ammunition and impotently firing star shells, the only ammunition remaining.6 Badly damaged, she came to a stop with her superstructure shattered and flames spreading throughout the ship. Bombs continued to rain down, preventing HMS Fiji from stopping to pick up survivors, though she dropped life rafts over the side before she was forced to depart. Of the 807 men aboard at the time of HMS Gloucester’s sinking, only 85 survived to be captured by the Germans. The body of Capt H.A. Rowley was washed ashore at Mersa Matruh, Egypt, four weeks later. There was no attempt by the Royal Navy to return after nightfall to search for survivors.7

Meanwhile, two bombs hit the battleship HMS Valiant and another scored a near miss on Fiji as she returned from the scene of Gloucester’s demise, close enough to damage the bottom plates of the hull and bring it to a halt with a heavy list to port. Leutnant Gerhard ‘Fähnlein’ Brenner of 2./LG 1 was among the relay of Ju 88s shuttling between Athens and Kythira Straits to bomb the Royal Navy ships. His first three separate attacks yielded near misses, but his final sortie of the day centred on HMS Fiji, now fringed by a spreading oil slick around her stern. Brenner dived at a steep angle before releasing his bombs, and three impacted on the cruiser, which quickly rolled over and sank, killing 241 men, 523 survivors later being rescued under cover of darkness. It was a victorious day for the Luftwaffe, and Hptm. Kuno Hoffmann, Gruppenkommandeur of I./LG 1, was awarded the Knight’s Cross on 14 June, Oberst Herbert Rieckhoff, Geschwaderkommodore of KG 2, and Gerhard Brenner receiving the same decoration on 5 July 1941.8 On 22 May VIII.Fliegerkorps had flown thirty-eight sorties against Royal Navy groups, launched six torpedoes and claimed ninety-three hits by bombs from Ju 88 bombers, forty-one from Do 17s, one hundred and eleven from Ju 87s, eleven from Bf 110s and five from Bf 109s. That day, von Richthofen lost seven Ju 87s, two Ju 88s, three Bf 110s and one Bf 109, with four officers and twelve NCOs and men missing, four dead, six badly wounded and eight with light injuries.

Although the Royal Navy had prevented the planned seaborne reinforcement of the Fallschirmjäger on Crete by successfully intercepting two troop convoys under inadequate Italian escort, the battle for the island was lost within days, and another evacuation was ordered a week after the first Germans had landed. By this stage the Royal Navy had already taken a fearsome battering at Luftwaffe hands, and it showed no signs abating as the evacuation began on the night of 28/29 May. The island surrendered on the first day of June.

The toll on the Royal Navy during the Cretan battle had been severe, though had the Luftwaffe been willing to bomb by night it would have been greater. Admiral Cunningham had deployed four battleships, one aircraft carrier, eleven cruisers, a minelayer and thirty-two destroyers in the defence of Crete and its consequent evacuation. Of these, air attacks by German and Italian aircraft had severely damaged the two battleships HMS Warspite and Barham and the carrier HMS Formidable, which was hit by bombs and required twenty weeks of repair work. Three cruisers were sunk, HMS Gloucester, Calcutta and Fiji, and five others badly damaged, and six destroyers were lost, with a further seven requiring lengthy dockyard repairs. Approximately 16,500 men had been rescued from Crete, but the British and Commonwealth forces suffered 3,579 men killed and missing, 1,918 wounded and 12,254 captured in another calamitous defeat. Somewhat ironically, as the Cretan disaster was about to unfold, Churchill abruptly issued orders that Rommel must be stopped at all costs and that ‘not only must Egypt be defended, but the Germans have to be beaten and thrown out of Cyrenaica’, presumably by the very troops he had demanded be moved to Greece. The exhausted Admiral Cunningham later ruefully wrote to the First Sea Lord:

There is no hiding the fact that in our battle with the German Air Force we have been badly battered. I always thought we might get a surprise if they really turned their attention to the fleet. No A/A fire will deal with the simultaneous attacks of ten to twenty aircraft.9

The Wehrmacht was triumphant within the Mediterranean. However, the clarity of hindsight tells us that a serious tactical blunder was made almost immediately, when the Reich Air Ministry ordered that the aircraft of Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps which had remained in Sicily be transferred to Greece to undertake operations against British forces within the Eastern Mediterranean. The aircraft of I. and II./LG 1 and II./KG 26 were soon joined by III./KG 30 and the two strategic reconnaissance Staffeln, 1.(F)/ Aufkl.Gr. 121 and 2.(F)/ Aufkl.Gr. 123. Flying from the Athens airfield, they were tasked with hunting Allied naval and merchant ships, attacking ports and coastal installations, mining harbours and waterways, and bombing military installations and RAF airfields within the Nile Delta region. Having exhausted their supply of torpedoes, the KG 26 Heinkels began using some of the marginally larger Italian F200 Whitehead-Fiume torpedoes, bought from the Italian forces and designated ‘LT-F5W’ by the Luftwaffe. These began arriving at Eleusis towards the end of May. The Italian torpedo was 45cm in diameter, weighed 905kg, carried a warhead of 200kg of explosives, had a range of 3,000m, a speed of 14 knots and could be launched by an aircraft travelling at 300km/h, the highest speed yet possible for German aerial torpedoes.

Geisler had successfully argued that the best method of supplying Axis forces in North Africa was via Greece and Crete. With the resultant diversion of Luftwaffe power, pressure on Malta was to be maintained by the Regia Aeronautica. Yet the latter had already failed to prevent a resurgence of the island as a viable military base from which to threaten Rommel’s current lines of supply. Before long, convoys between Sicily and Tripoli were once again under regular British attack. Under orders from Berlin, Dönitz had unwillingly allocated U-boats to the Mediterranean, beginning in September 1941, and although they claimed an initial toll of major Royal Navy ships, including the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battleship HMS Barham, their success was short-lived. None of the boats would ever return to the Atlantic battle, which remained Dönitz’s centre of operational gravity, a loss of experienced men and valuable U-boats at a time when they could still have made a difference in the Atlantic convoy war.

Far from these developments within the Mediterranean theatre, Küstenflieger continued to mount armed reconnaissance missions into the North Sea, predominantly carrying bombs, with occasional sorties by torpedo-armed He 115s when newly produced stocks of the weapon allowed. During the early part of 1941 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 had converted from the antiquated Do 18 to the He 115, and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 was scheduled to convert to the BV 138 flying boat, though this would not be fully completed until the beginning of the following year. Both the first and second Staffeln returned to Norway, 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 being based at Tromsø and 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 at the established seaplane base at Trondheim, occasionally using Stavanger as an alternative location. These Staffeln were administratively controlled by Küstenfliegergruppe 706 at Stavanger. Constant patrolling of the Skagerrak and its approaches had been undertaken alongside offensive sweeps, and MGK Nord issued a communique to OKM on 24 April 1941 which included appreciation of the value of Küstenflieger forces:

In general, it should be noted that, despite low force numbers, all demands for security and reconnaissance, and especially for mining missions, have been fulfilled in an exemplary fashion by Kustenfliegergruppe 706. The achievements of this unit are to be particularly appreciated in the reporting period as well as for the past winter months.10

Oberstleutnant Walter Weygoldt’s Küstenfligergruppe 506 mounted occasional torpedo operations, though stocks of the weapon averaged five at any one time for the entire Gruppe as, although the embargo on their use elsewhere had been lifted, the majority continued to be shipped to the Mediterranean. With such a scarcity, Weygoldt pushed for the conversion of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 to Ju 88s as soon as possible, his He 115s showing severe handicaps in combat with enemy aircraft and suffering heavy losses. Schily had ordered that patrols near the British coast should be mounted only under heavy cloud cover or by night, though an increasing rhythm of effective nightfighter activity still posed a serious threat. During one such nocturnal mission, at 2312hrs on 2 June 1941, Lt.z.S. Friedrich Michael of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 scored a resounding success when he hit an aircraft carrier with two torpedoes in the approaches to the Humber, columns of water being thrown thirty metres into the air by the detonations. The location of the carrier, identified as either HMS Indomitable or Hermes, had been reported earlier that day, after she had been sighted by a Ju 88 of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 during an attack on shipping off the Yorkshire coast that sank the French SS Beaumanoir and its cargo of coal, and damaged the SS Thorpebay. At that moment Küstenfliegergruppe 506 had no torpedoes in stock, so Obstlt. Schily improvised a solution by despatching three crews to the torpedo testing ground at Grossenbrode, where they collected three He 111s carrying practice torpedoes. Once the weapons had been rearmed with live warheads, the aircraft were used to attack the sighted carrier before being returned to Grossenbrode. Buoyed by this success, Schily immediately communicated his congratulations to Küstenfliegergruppe 506.

For the exemplary operational readiness shown today, due to the ongoing missions on the 2nd and 3rd of June, when 10,000 tons [of shipping] were destroyed with the weakest available forces, I commend Gruppe 506 and all military personnel and civilian employees involved.

Special thanks go to Staffel 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, which achieved the success of two torpedo hits under difficult conditions using a new aircraft model, and the likely damaging of an aircraft carrier. May the accomplishments of today be a spur to even greater success.

The Commander-in-Chief of Marinegruppe Nord, Generaladmiral Carls, expressed his gratitude to both myself and my subordinate squadrons, and his special recognition for the achievements made yesterday.

The action was reported in the Wehrmachtbericht as two torpedo hits on a ‘large British warship’. But Michael had actually torpedoed the 7,924-ton SS Marmari, a large freighter commandeered by the Admiralty in 1939 with two others and converted into decoy ships; in this case a plywood-panelled look-alike of HMS Hermes. Known for security reasons as ‘Tender C’, Marmari had been part of Force W, designed to fool German aerial reconnaissance into chasing phantom capital ships. The decoy carrier was disabled while evading Heinkel torpedoes, the hull striking the wreck of the steam tanker SS Ahamo, sunk by mine during the previous April. The Kriegsmarine later despatched Schnellboote S19, S20, S22 and S24 to destroy what they believed to be an incapacitated carrier, and, despite defending fire from an accompanying minesweeper and the sloop HMS Kittiwake, S22 and S24 hit the ship with three torpedoes and sank what they reported as ‘6,000 tons, presumably a Sperrbrecher’.

By April, the build-up of Luftwaffe forces in the Mediterranean Theatre and the east for Balkan missions and in preparation for Operation Barbarossa necessitated refreshment of Luftwaffe Atlantic forces. To that end, 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 relinquished its He 115s and departed from Brittany for Barth and conversion to Ju 88 bombers. It was the final component of Küstenfligergruppe 106 to undergo the change, and with all three Staffeln now operating land-based aircraft the Gruppe commanded by Hptm. Wolfgang Schlenkhoff had its designation officially changed to Kampfgruppe 106 (KGr. 106), though the unit did not immediately pass completely outside Ritter’s responsibility as Gen.d.Lw.b.Ob.d.M. until September. Once all sections had completed the change to Ju 88s, operations by KGr. 106 revolved around the night bombing of Britain. During one such raid on 28 June, Ju 88A-6 M2+CK failed to return, Gruppenkommandeur Hptm. Schlenkhoff and his three crewmen being posted as missing in action. Major Friedrich Schallmeyer took command of KGr. 106 until April 1942, when he was replaced by Maj. Ghert Roth, former commander of Küstenfliegergruppe 406 and intelligence officer at Stab/IX.Fliegerkorps. During September that year KGr.106 was finally redesignated II.Gruppe of the newly formed KG 6. Roth also killed in action when his Ju 88 was shot down on 8 September, during a night mission to Bougie, Algeria. The aircraft of Kampfgeschwader 6 were distributed both east and west, bombing British mainland targets and supporting Army Group North in bombing raids on targets within the northern Soviet Union. Only I./KG 6 transferred to the Mediterranean to continue anti-shipping strikes.

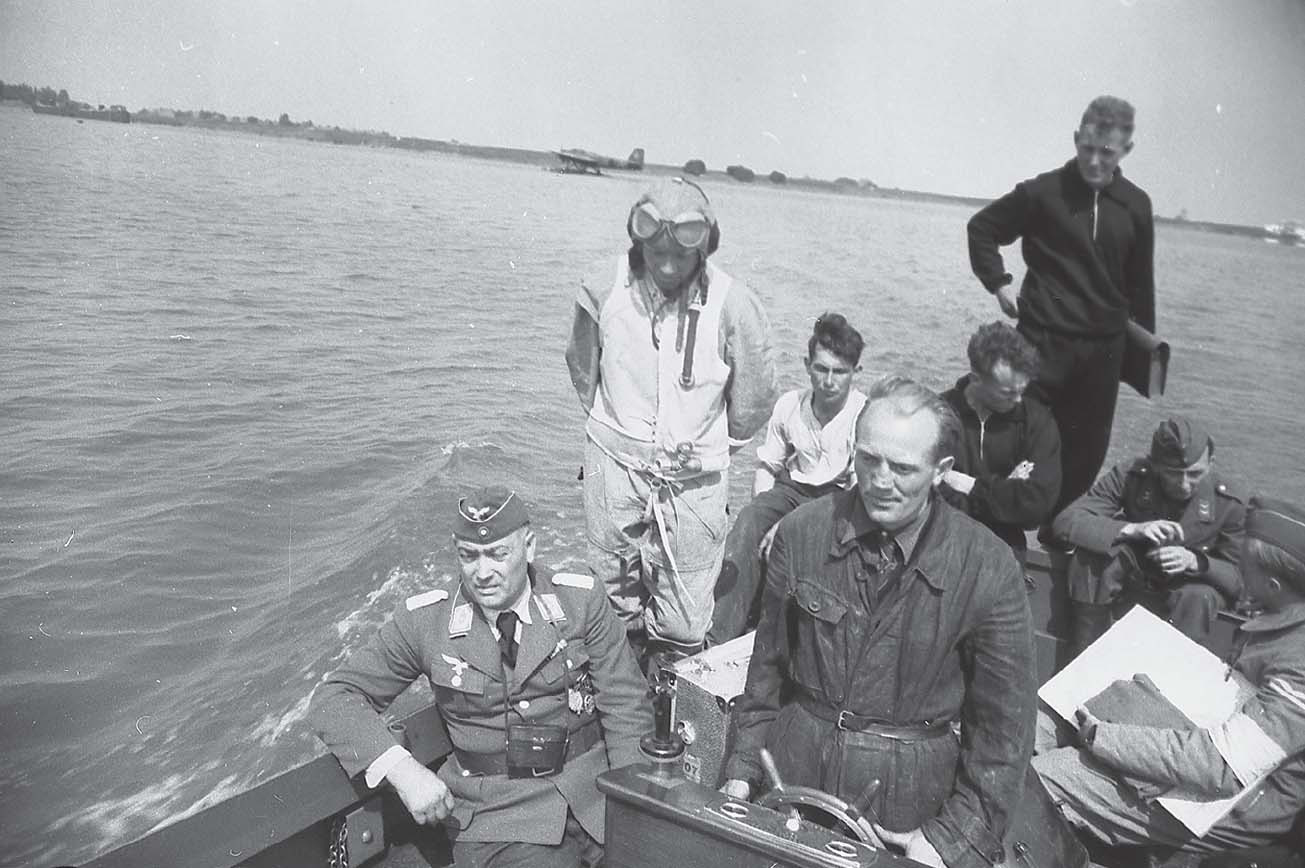

The crew of an He 115 are brought ashore to their Belgian base. (Bundesarchiv)

The Luftwaffe reorganised its western commands during March and April 1941 to assist in the blockading of Great Britain. Theoretically, their purpose was to provide anti-shipping units that could cover the entire coastline stretching from northern Norway to the Franco-Spanish border. This not only observed the strategic goals employed by the Wehrmacht against Britain, but also provided an imperative for the Luftwaffe to absorb further maritime units previously tactically controlled by the Kriegsmarine. On the northern fringe of this realignment of Luftwaffe commands, on 1 April, the post of Fliegerführer Ostsee was occupied by Oberst Wolfgang von Wild, Kommandeur of KGr. 806. Hermann Bruch subsequently moved from the position of Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte on 21 April, to be appointed to the office of Kommandierender Gen.d.Lw. Nord Norwegen (acting as Fliegerführer Nord Norwegen) in Bardufoss, and von Wild stepped simultaneously into his vacated F.d.Luft. role, Maj. Hans Emig taking command of KGr. 806. Initially, von Wild’s Ostsee command comprised only KGr. 806 and the Luftwaffe’s own new maritime reconnaissance element, Aufklärungsgruppe 125 (See), which had been established in Kiel-Holtenau. Two such units were formed during April 1941, with many men transferred to its ranks from existing Küstenflieger units:

Aufklärungsfliegergruppe 125 (See) (Kiel-Holtenau), Obstlt. Gerhard Kolbe.

Stab/Aufkl.Gr. 125 (Kiel-Holtenau), He 60

1./Aufkl.Gr. 125 (Kiel-Holtenau), He 60

2./Aufkl.Gr. 125 (Thisted), He 114

3./Aufkl.Gr. 125 (Holtenau), Ar 95A

Aufklärungsfliegergruppe 126 (See) (Travemünde), Maj. Hans-Bruno von Laue.

Stab/Aufkl.Gr. 126 (Travemünde), He 60

1./Aufkl.Gr. 126 (Travemünde), He 60

2./Aufkl.Gr. 126 (Travemünde), He 60

3./Aufkl.Gr. 126 (Travemünde), He 60

These reconnaissance units initially used the outdated aeroplanes that Küstenfliegergruppen were discarding, and still included a large proportion of Kriegsmarine personnel in their observer role. One such man was Oblt.z.S. Rolf Thomsen, posted to Aufkl.Gr. 125 at its inception. Thomsen’s career is quite indicative of the path many Kriegsmarine officers followed into and out of the naval air service. Having joined the Kriegsmarine in 1936, he as posted as Watch Officer to the minesweeper M89 in April 1938 before transferring to flying training at the Fliegerwaffenschule, Bug, Rügen. From the beginning of the war until September 1940 he served as an observer in 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 before being made 1. Admiralstabsoffizier op. (Seeluftstreitkräfte) on the F.d.Luft staff in Wilhelmshaven. In April 1941 he was appointed an aircraft commander and 1. Admiralstabsoffizier for Aufkl.Gr. 125 for a year, during which he served within the Aegean and Black Sea (as Deputy Commander and 1. Admiralstabsoffizier, Russia) before being transferred to Harlinghausen’s torpedo department as a member of the Staff/ Bevollmächtigen für die Lufttorpedowaffe, while also serving as Adjutant for KG 26. Finally, in April 1943, he returned to the Kriegsmarine and began training for U-boat command. Thomsen later captained U1202, his U-boat being adorned with the crest of the ‘Löwen Geschwader’, and he ended the war decorated with the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves.

At the same time that the two Aufklärungsgruppen were formed, Luftflotte 5 established the post of Fliegerführer Nord in Stavanger from the Staff of KG 26, commanded by Generalleutnant Alexander Holle and responsible for anti-shipping operations, U-boat support and coastal reconnaissance north of latitude 58°N. By the time of Operation Barbarossa, Holle controlled the fighter aircraft of Jagdfliegerführer Norwegen as well as I./KG 26, II./KG 30 and IV.(Stuka)/LG 1. The sea area south of the dividing latitude remained the domain of F.d.Luft, whose assets were grouped around Jutland. During December 1941 Holle’s office was subdivided into three separate commands: Fliegerführer Nord (West) under Oberst Hermann Busch, based in Trondheim and responsible for the southern Norwegian area up to 66° North latitude that ran through the islands of Nord-Herøy and Alsten; Fliegerführer Lofoten, under Oberst Ernst-August Roth, responsible for the area between 66° North and Altafjord; and Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) under Oberst Alexander Holle, based in Kirkenes and responsible for the Arctic area north of Altafjord to Finland.

Stripped to the bone, Raeder’s naval air service was now a shadow of what it had once been, and continued to be further eclipsed in Göring’s reshuffling. On the eve of Operation Barbarossa, Oberst von Wild, as Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte, controlled only the four Staffeln of Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 based at Westerland, three of Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 at Aalborg, and the Bordfliegerstaffel 1./B.Fl.Gr. 196 in Wilhelmshaven. The remainder of the Küstenfliegergruppen were distributed between Luftflotten of the operational Luftwaffe. By the end of June 1941 the Luftwaffe possessed a total of nine torpedo Staffeln:

Within the Atlantic battleground KG 40 remained locked in missions alternating between U-boat reconnaissance and offensive shipping strikes. The Fw 200s continued long-distance reconnaissance, B.d.U. maintaining their primary role as that of shadowing aircraft, bombing attacks being considered a subsidiary task of opportunity. The smaller He 115 and Ju 88 units continued attacks on British coastal shipping and those targets found within the Irish Sea, while the twin-engine Bf 110s of 3./KGr. 123 mounted reconnaissance sorties over the English southwestern coastal area.

The large Condors had begun to encounter heavily-armed Short Sunderland flying boats more frequently, and though they often fought inconclusive running battles, the steady drain of wounded men and damaged aircraft reduced operational levels and corresponding mission frequency. On 17 July Oblt. Rudolf Heindl’s Condor successfully shot down a Whitley of 502 Sqn which was flying as anti-submarine escort for Convoy OB346. Heindl’s wireless operator, Oblt. Hans Jordens, was killed in the exchange of fire, which marked the first confirmed aerial victory for a KG 40 Condor. However, the elation was tempered by the loss of Knight’s Cross holder Hptm. Fritz Fliegel’s Condor, F8+AB, the next day, shot down by anti-aircraft fire from merchant ships of the same convoy. Fliegel’s wing was seen to shear clean away from the fuselage after the aircraft was hit, the entire Condor cartwheeling into the Atlantic with all crew lost; another indication of the relative fragility of the Condor’s airframe. Fliegel had been commander of I./KG 40, and had received his Knight’s Cross on 25 March for the credited sinking of seven ships and damaging of a further six. His was the most senior loss suffered by KG 40 thus far, his place as Kommandeur taken by Hptm. Edmund Daser, former Staffelkapitän of 1./KG 40. The inherent weakness of the Condor was improved somewhat in the upgraded Fw 200C-3, which was structurally strengthened and equipped with better Bramo 323R-2 radial engines. Derivatives of the new variant also had upgraded defensive weaponry and were fitted with a hemispherical dorsal turret, plus enhancements to the ventral gondola that allowed the fitting of a Lotfe 7D gyroscopically stabilised bombsight, based on the extremely effective American Norden bombsight. The Carl Zeiss Lotfernrohr 7 series of sights had been the Luftwaffe standard since the war’s beginning, the 7C being the first to feature gyroscopic stabilisation.

Part of a German newsreel film showing a Condor crewman preparing food during what were frequently gruelling Atlantic patrols.

Robert Kowalewski, a former Reichsmarine officer and highly successful bomber pilot. (Bundesarchiv)

Casualties had indeed been heavy in July. Five days after Fliegel’s death, Obfw. Heinrich Bleichert’s Condor of I./KG 40 was brought down by a 233 Sqn Hudson while attempting to attack Convoy OG69. The Hudson pilot, Fg Off Ron Down, recalled the successful engagement:

Flying above the convoy, at about a hundred feet above the sea, was one of the big Focke-Wulf Condors. We were overhauling him fast. Whether he saw us or not I don’t know, but at four hundred yards I opened up with about five bursts from my front guns, and I could see tracer bullets whipping past the nose of the Hudson in little streaks of light. But he missed us, and his pilot turned slightly to starboard and ran for it, parallel to the course of the convoy . . . Once he put his nose up a trifle, as though meditating a run for the clouds. He must have decided he couldn’t make it and was safer where he was, right down on the sea . . . We drew closer and closer. The Condor began to look like the side of a house. At the end all I could see of it was part of the fuselage and two whacking big engines. My rear gunner was pumping bullets into him all the time. When we were separated by only forty feet I could see two of his engines beginning to glow.11

Bleichert successfully ditched in the sea, all the crew escaping to be captured apart from the on-board meteorologist, who had been shot through the heart by the Hudson’s gunfire. The following day 1./KG 40 Staffelkapitän Hptmn. Konrad Verlohr was posted as missing in action after his aircraft was lost west of Ireland. In return, not a single ship was sunk during July.

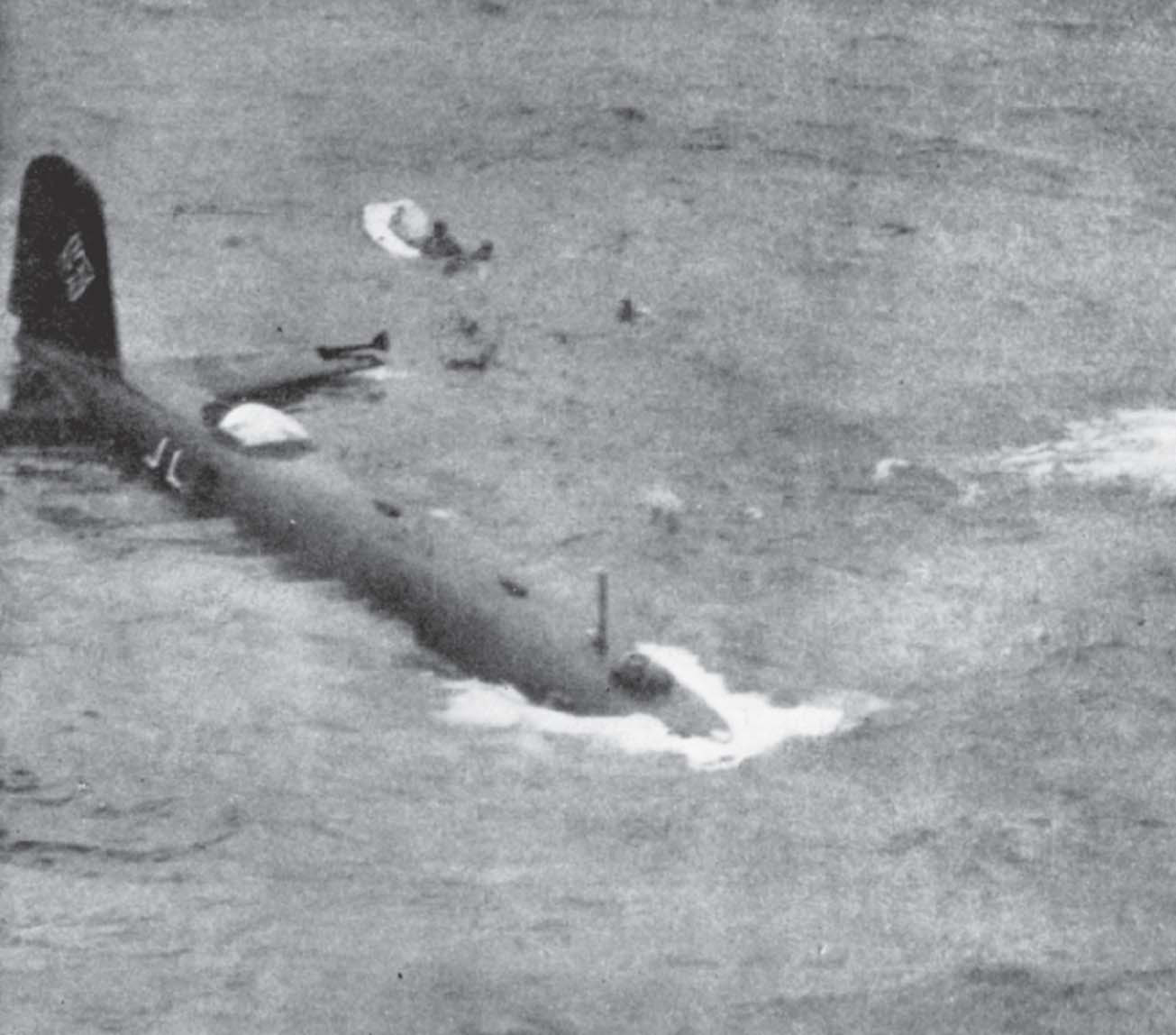

ObFw. Heinrich Bleichert’s Condor of I./KG 40 brought down by a 233 Squadron Hudson while attempting to attack Convoy OG69 on 23 July 1941.

Meanwhile, at Lüneburg during May 1941, II./KG 40 became the second bomber unit (after KG 2) to equip with the Do 217. The Gruppe’s 4.Staffel was originally intended to operate as a torpedo unit, but trials using two Do 217Es on loan from KG 2 as torpedo carriers were initially unsuccessful owing to persistent electrical problems. Some Do 217s had already been taken on the strength of the newly formed II./ KG.40, based at Soesterburg in The Netherlands and Bordeaux, flying conventional anti-shipping bombing strikes from March 1941. The Do 217 had suffered episodic delays during its arduous development process, hamstrung by Luftwaffe command-level obsession with a dive-bombing capability which was only belatedly recognised as utterly impractical for an aircraft of this size, and dropped from the list of requirements by the RLM in mid-1941. Further trials and then tests resulted in the ability of a Do 217E-2/R4 to deliver a single LT F5b torpedo held by a PVC 1006 carrying rack, but the variant was never used in action, the role being allocated instead to Ju 88s, which were much easier to modify.12 Later attempts at modifying a Do 217K-07 to carry four LT F5b torpedoes on underwing racks were made during 1943, but ultimately deemed unsatisfactory and not pursued beyond initial trials.

Another view of Bleichert’s Condor, with OG69 visible in the background. All of the German crew except the onboard meteorologist were rescued.

During the summer of 1941 Petersen was ordered to form an independent ‘Kommando’ from I./KG 40 for transfer to the Mediterranean. There he was to fly anti-shipping strikes over the Gulf of Suez, the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea. Six Fw 200s and nine He 111s, the latter commanded by Hptm. Robert Kowalewski of III./ KG 40, who had previously commanded the torpedo aircraft of II./KG 26, were despatched to Athens during August. Petersen, however, was not destined to remain at this new position for long, as he was posted during September to command the network of Luftwaffe testing sites (Kommandeur Kommando der Erprobungsstellen der Luftwaffe), while concurrently heading the research establishment at Rechlin focussed upon developing the Heinkel He 177 Greif, which was beset by design problems. In his stead as Kommodore KG 40 in Athens came Obstlt. Dr Georg Pasewaldt, previous commander of II./KG 40 and provisional Kommodore until the end of 1941.

‘Kommando Petersen’ flew missions over the Suez and Red Sea area for only a brief period during early September. After that, the Fw 200s returned to Bordeaux and the Heinkels to Soesterberg, from where they had originated. During their brief Mediterranean tenure they achieved no successes, but lost two aircraft. Oberleutnant Horst Neumann’s Fw 200C, F8+GH, crashed into the sea near Cape Sounio after take-off on 5 September, killing all of its crew, and Fw. Werner Titz’s He 111 was shot down by a South African Hurricane of 94 Sqn while engaged in a conventional bombing raid on Abu Sueir, Egypt, on 6 September, the whole crew being taken prisoner.13 However, other units continued to raid the Red Sea approaches to the Suez Canal. The 5,718-ton American freighter SS Steel Seafarer was sunk by a Ju 88 of LG 1 on 5 September. The ship was travelling from New York to Suez, clearly marked as a neutral, with American flags painted on the hull sides, when the aircraft attacked in darkness at 2328hrs. The ship was steaming at 4 knots with navigation lights burning in clear weather, though strong winds had made the sea rough. A single bomb landed squarely, and Master John D. R. Halliday ordered the engines stopped and the crew to abandon ship. As they pulled away in three lifeboats, Steel Seafarer capsized and sank within fifteen minutes of being bombed. Neutral it may have been, but it carried 5,700 tons of munitions for British North African forces, one of many American-flag freighters carrying such cargo under lucrative charter terms from the British government.

The preparation for Operation Barbarossa saw Luftflotten 1, 2, 4 and 5 move east in small components to avoid security breaches during June. Fliegerführer Atlantik thus became the sole dedicated anti-shipping force remaining in the Western Theatre. IX.Fliegerkorps was employed on minelaying as well as night bombing of British land targets, while the aircraft of Fliegerführer Nord and Lofoten were largely confined to scouting within northern latitudes.

The Luftwaffe was an essential component of the ambitious attack in the east, nearly two-thirds of operational bomber Kampfgruppen — thirty-two in total — being deployed between the four committed Luftflotten. The main maritime component of this initial attack would be carried by elements of Generaloberst Alfred Keller’s Luftflotte 1, supporting Army Group North in its advance through the Baltic states towards Leningrad, and the Arctic elements of Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff’s Luftflotte 5 in Norway. Within this latter region maritime missions were co-ordinated by Fliegerführer Kirkenes, Nielsen having established his headquarters at the Kirkenes Airfield, initially as an independent detached unit, but soon subsumed to Stumpff’s command. As well as supporting the ground offensive, Nielsen’s tasks entailed the disruption of the straggling supply links between Leningrad and Soviet terminals on the Arctic Ocean: the harbours at Murmansk (particularly valuable as it was ice-free throughout the year), Kolskiy Bay and Arkhangelsk. The Kirov railway provided the primary link, and attacks against it and shipping within the Soviet ports were of high priority. In this unforgiving Arctic landscape Kirkenes Airfield and that at Banak, at the southern end of Porsanger Fjord and described by Hajo Herrmann as ‘a God-forsaken Lapp village in a treeless, tundra-like area’, were the only two airstrips suitable for his aircraft. Assigned to his command were ten Ju 88s of 5./KG 30 and He 115s and Do 18s of 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 at Banak, thirty-six Ju 87s of IV.(Stuka)/LG 1, ten Bf 109s of I./JG 77, six Bf 110s of Stab/ZG 76, and three Ju 88s of 1./ Aufkl.Gr. 124 at Kirkenes, and a further seven reconnaissance Hs 126s and Do 17s of 1.(H)/Aufkl.Gr. 32 at Kemijärvi and Rovaniemi. Two He 111s and two Ju 88s of a weather reconnaissance section were also attached to his command, along with eleven Ju 52 transport aircraft for internal movement of men and equipment.

Significant casualties were suffered amongst trained maritime pilots and crew by their use in bombing mainland Britain as the tug of war over control of the Luftwaffe’s maritime forces reached new intensity during 1941.

In the Baltic, Fliegerführer Ostsee was committed to the attack on the Soviet Union, guarding the northern flank of Luftflotte 1, all tasks carried out in close cooperation with Kriegsmarine Baltic commands, in particular Vizadmiral Hubert Schmundt as Befehlshaber der Kreuzer based in Helsinki, requiring up to date information regarding any major Soviet fleet movements. While larger bombers penetrated deeply within the eastern Baltic, the smaller aircraft of Aufkl.Gr. 125 flew repeated anti-submarine patrols and convoy escort for coastal supply routes used by German merchant ships. The totality of roles included searching for indications of offensive movement made by the Soviet Baltic Fleet, as well as minelaying, escort duties, bombing Soviet merchant and military shipping and supporting ground forces whenever possible. Oberst Wolfgang von Wild, whose headquarters were at Metgethen in the East Prussian Samland district, had directly under his control: Stab/Aufkl.Gr. 125, Obstlt. Gerhard Kolbe (He 60); 1./Aufkl.Gr. 125, Hptm. Friedrich Schallmayer (He 60); 2./ Aufkl.Gr. 125, Oblt.z.S. Rolf Lemp (He 114); and 3./Aufkl.Gr. 125, Oblt. Kurt Lüdemann (Ar 95A). However, he also exercised tactical command over elements of the two Ju 88-equipped Kampfgruppen recently removed from the Küstenflieger service: KGr. 806, (Maj. Hans Emig) and 1. and 2. Staffeln of KGr. 106. Von Wild’s other resources included Hptm. Karl Born’s 9.Seenotstaffel, comprising a handful of He 59s, two pairs of Do 18s and Do24s, Junkers Ju 52 (M) ‘Mausi’ minesweepers, and the air-traffic-control ship Karl Meyer, which was used as a navigational aid.

Officers and crew of a shore-based Ar 196 Staffel celebrate completion of their 2,600th combat mission.

The ‘Mausi’ had been developed in response to enemy magnetic minefields. A standard Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft was fitted with an external duralumin Gauss loop of 14.6m diameter suspended beneath the fuselage, and a generator powered by a 270hp Mercedes engine in the forward fuselage, the aircraft being classed thereafter as a Ju 52/3m MS. A small number of similarly equipped BV 138C-1/ MS floatplanes and obsolete Dornier Do 23 twin-engine bombers soon became operational, as the method proved effective in action though extremely dangerous. The aircraft flew low above the water surface, typically between ten and thirty metres, and the electric current was sufficient to explode the mines below, which could pose a danger to the aircraft. They generally operated in pairs, and two ‘Mausi’ minesweepers were lost on 26 October in such a mine detonation near Harilaid Island, several crewmen being wounded.

A Junkers Ju 52 ‘Mausi’ minesweeping aircraft, photographed here on the Eastern Front. (Bundesarchiv)

While aircraft of Luftflotte 1 were tasked with devastating Soviet air units and achieving aerial supremacy over the northern sector, Fliegerführer Ostsee intended to attack the Soviet Baltic Fleet both at sea and in harbour with bombs and mines, tie up merchant shipping within the Baltic, and stop traffic through the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal (the ‘Stalin Canal’), primarily by destruction of the lock installations at Povenets on Lake Onega, which were the canal’s highest locks above sea level and comprised seven timber gates named the ‘Stairs of Povenets’. Destroying the canal’s functionality could prevent the Soviet transfer of approximately forty-five submarines, fifteen destroyers and various minelayers from the Gulf of Finland to the Arctic Ocean, where the Kriegsmarine presence was thin at best. Familiarisation flights within the area were undertaken by Fliegerführer Ostsee, assisted by the Finnish Air Force and flying as far as Utti (Kouvola) in preparation for the Barbarossa attack.

On 22 June, the opening day of Barbarossa, most bomber groups were engaged in battering Soviet airfields, though Major Emig’s KGr. 806 flew what was probably the longest single mission made by any Luftwaffe formation when it completed the 1,000-mile round trip from East Prussian airfields to the main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet at Kronstadt, west of Leningrad, to lay twenty-seven LMB mines. Emig’s aircraft achieved total surprise over the Soviet naval base. They were guided by a Finnish liaison officer carried aboard the lead aircraft, the monotony of the landscape and lack of navigational fixtures testing the Luftwaffe aircrafts’ navigation.

The Ju 88s’ final approach from the Ingermanland coast was made at low level, sweeping over Leningrad and reaching Kronstadt from the east. Consequently not a single anti-aircraft shot was fired, as the gunners misidentified the aircraft. Twenty-eight mines were successfully dropped before the Finn guided Emig’s aircraft home via a prearranged air corridor over Finnish territory, landing at the liberated Utti Airfield where the aircraft were refuelled before returning to East Prussia. Despite the extraordinary effort, this initial attempt at obstructing Kronstadt sank only the small 499-ton Estonian ferry Ruhno in the Leningrad Sea Port Canal, killing three men.

The Ju 88s of Major Hans Emig’s Kampfgruppe 806 mounted probably the longest single Luftwaffe mission at the opening of Operation Barbarossa with a 1,000-mile round trip to lay mines near Leningrad.

The Kriegsmarine were also sowing extensive defensive minefields to pen the formidable Soviet naval strength in the eastern Baltic, and Emig’s Ju 88s were thereafter committed to this minelaying drive over the following weeks. Emig’s Gruppe began using Helsinki Aerodrome as a stop-off and refuelling point when engaged in missions to distant northern targets, and urgent work was undertaken by the Finns to extend the runway to 1,500m by demolishing five houses and cutting down surrounding forest.14 Utti had initially proved unsuitable for the German bombers, and after the official entry of Finland into the war on the Axis side on 25 June, four KGr. 806 Ju 88s lifted off from Helsinki Aerodrome and headed for Kronstadt, where they tried unsuccessfully to bomb the Soviet cruiser Kirov, though Emig claimed the ship hit and damaged. Sporadic armed reconnaissance missions were also flown alongside the planned attack on the Stalin Canal launched from Helsinki by KGr. 806 on the night of 27 June.

With his Ju 88 armed with BM1000 ‘Monika’ mines (essentially the LMB mine fitted with a tail unit that allowed dropping without a parachute, in the manner of a conventional bomb), Maj. Emig led the raid, which approached the target in three waves during the early morning hours at extremely low altitude to increase chances of success. Emig successfully dropped his mine, which destroyed the lock gate that he had targeted, but his aircraft was so low that it took the full force of the blast and crashed. Emig and his crew, Observer Obfw. Helmut Rudolf, Wireless Operator Obfw. Heinz Bodensiek, and gunner Obfw. Werner Hawlitschka, were all killed as the Ju 88 ploughed into the ground in flames near Lock Gate Number 3.15 Hauptmann Erich Seedorf, Staffelkapitän of 1./KGr. 806, ordered the two following waves to bomb from an increased height of 100m, and no further losses were reported, though one other Junkers later made an emergency landing at Utti airfield. The Povenets lock installation was damaged by the attack, and by a second one made on 15 July, and boat traffic on the canal was interrupted until 6 August. As each destroyed gate was repaired, the Kriegsmarine requested fresh attacks to maintain the blockade of Soviet naval forces in the Gulf of Finland, and another bombing raid on 13 August kept the canal unserviceable for eleven more days, after which further air attacks on the canal were mounted on 28 August and 5 September. During one of the latter attacks, led by Maj. Wolfgang Bühring, Kampfgruppe 806 used SC1000 ‘Hermann’ bombs with newly designed detonators specifically intended for low-level bombing, and succeeded in completely destroying a lock gate and severely damaging the lock basin itself. However, several Ju 88s were lost through premature detonation of the bombs, and their use was immediately curtailed by the Chief of Luftwaffe Supply and Procurement.16 Finally, on 6 December 1941, in a -37 °C frost, Finnish troops captured Povenets and the southern end of the Stalin Canal. Retreating Soviet troops demolished locks and dams, and water from the watershed lakes began to pour into Lake Onega through Povenets village, which was almost destroyed. The Finnish troops were soon pushed back to the canal’s western bank by fierce counterattacks, while the Soviets held the east, and they remained in these positions until June 1944.

Meanwhile, the former Reichsmarine aviator and Kommandeur of I./KG 54, Hptm. Richard Linke, took command of KGr. 806, which continued anti-shipping operations over the Baltic. On 18 July two Soviet destroyers attempted to attack a small German supply convoy heading for the Latvian port of Daugavgriva. Although the convoy escaped interception, the destroyers were caught within the Gulf of Riga by Linke’s aircraft, hemmed in by the narrows east of Saaremaa island as they raced for the open Baltic. During the ensuing attack the 1,686-ton Serdity was so badly damaged that it was scuttled after the Soviet Navy had spent three days attempting to keep it afloat.

In the Arctic on the opening day of Operation Barbarossa the temperature barely reached 8°C, and cloud, rain, and lack of visibility severely hampered flying operations, and German ground forces did not open their assault toward Murmansk until the Finnish entry into the war. The delayed opening of this three-stage land attack, codenamed Operation Silberfuchs, removed any element of surprise, and although only 120 kilometres separated the German jumpingoff point in Norway from the port of Murmansk, the advance soon stalled in the face of stubborn resistance and excruciatingly difficult terrain. Along the line of the Liza River, halfway between Petsamo and Murmansk, fighting devolved into trench warfare, resulting in little movement until 1944.

Fliegerführer Kirkenes was closely embedded with Wehrmacht ground troops within the Arctic circle, and frequently mounted operations in support of the stalled ground offensive, including the same type of attacks against Soviet airfields that had taken place throughout the front line in the early days of Barbarossa. Principle missions were only vaguely defined by instructions from OKW, but included interdiction of Soviet supply routes and protection of German convoy traffic, the only method by which Kirkenes could be resupplied. Numerically weaker than the Soviet air forces they faced, initial attacks on Soviet airfields, communication lines and power stations were very successful, despite Barbarossa already being three days old by the time the Northern Front was opened.

With no Kriegsmarine surface forces present until the following month, defence of the coastal region fell completely to Nielsen’s air units, which helped to decimate a Soviet amphibious landing at Kutovaya, behind the German front line. Minelaying had begun following an initial reconnaissance flight in the early morning of 23 June, after which eight Ju 88s mined the Kola Bay and Polyarnoye, near Murmansk. More mines were laid immediately before Murmansk during the following day. Although little result was observed from these operations, Soviet minesweepers were kept busy ensuring the entrances to the Arctic harbours were swept. Even so, the Soviets made very little offensive movement in the Arctic Ocean throughout 1941.

On the same day that Murmansk had been mined, and before Finland officially entered the conflict, two He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 carried a Finnish sabotage group of sixteen men on a mission against the Stalin Canal, at that stage still untouched by the bombers of KGr. 806. Operation Shiffaren was carried out with the Finnish soldiers wearing German uniforms, the He 115s taking off from Lake Oulujärviat at 2200hrs on 22 June and then flying a low-level, convoluted route that bypassed Soviet airfields. Once they reached the fringes of the White Sea the two Heinkels turned south and arrived east of the canal, alighting on a lake, where they dropped the saboteurs in rubber boats. While the German aircraft returned under cover of Finnish fighter aircraft, the commando team reconnoitred the canal locks but found them too heavily guarded to attack, deciding that the task could be handled better by Emig’s KGr. 806 instead. The Finns retreated, using their explosives against the Murmansk railway and eventually returning overland to friendly territory by 11 July, having lost two men in skirmishes with Red Army troops.

Two He 115s of Küstenfliegergruppe 406 were used to ferry Finnish commandos that operated against the Murmansk railway in June and July 1941. (James Payne)

Within the Baltic, Fliegerführer Ostsee was heavily involved in supporting the ground attack on Tallinn, Estonia’s seaport capital. The Red Navy destroyer Karl Marx was bombed in Loksa Bight on 6 August, and sank after attempts to keep the stricken ship afloat failed. By the end of August most bomber wings of Luftflotte 1 were being used against Soviet shipping evacuating Tallinn, as well as both military and merchant vessels within the Gulf of Finland and the Bay of Kronstadt, and on the Neva River and the Ladoga Canal. The mass Soviet naval evacuation of Tallinn enabled KGr. 806 to achieve its greatest successes, together with other Luftflotte 1 bomber units including nine He 111s of I./KG 4 and Obstlt. Johann Raithel’s KG 77, which was gravitating towards anti-shipping strikes. Alongside Hptm. Linke’s KGr. 806, I./ KG 77 and III./KG 77, totalling fifty-nine aircraft, attacked and sank the 2,317-ton SS Lucerne, the 1,423-ton Atis Kronvalds, the 2,414-ton Skundra and the 2,250-ton ice breaker Krisjanis Valdemars as they attempted to leave Tallinn. The light cruiser Kirov was damaged, as was the 2,026-ton SS Vironia, a former Estonian ship that had been commandeered by the Red Navy for use as a staff vessel. The Vironia struck a mine from the formidable Juminda barrage intended to pen Soviet ships in the Gulf of Riga. Under severe bombing, the remaining Soviet evacuation fleet changed course and blundered straight into the minefields, where thirty-five ships, including four destroyers and three submarines, were sunk.

The Luftwaffe repeated their attack with additional aircraft from KG 1 and KG 4 the following day, and three more ships were sunk: the 1,270-ton naval navigational and hydrographic training ship Lensoviet and two troop transports, the 3,974-ton Vtaraya Piatiletka and the 2,190-ton Kalpaks. A further three were severely damaged and beached on the Finnish island of Suursaari, and a fourth that was also hit, and beached on Seiskari, offloaded 2,300 of the 5,000 troops she carried before limping onward to Kronstadt, where the captain, wounded in the bombing, was executed for cowardice.

Between the opening of Barbarossa on 22 June and the end of August,Fliegerführer Ostsee had flown 1,775 sorties. Of these, maritime forces had flown: 737 by Aufkl.Gr. 125; 610 by KGr. 806; 15 by Kü.Fl.Gr. 406; and 66 by 1./BFl.Gr. 196. An estimated 66,000 tons of merchant shipping had been sunk, and 17,000 tons so badly damaged as to be considered ‘probables’. In return, von Wild had lost eleven Ju 88s, three Ar 95s, one Ar 196 and five Bf 109s.

During September Fliegerführer Ostsee was reinforced by the arrival in Riga of the fourteen Ju 88s of Hptm. Josef Sched’s 1./KGr. 506, though a planned assault on Leningrad itself, the main target of Army Group North, had been cancelled by OKW. Instead, the city was to be placed under siege, effectively ending Barbarossa maritime operations within the Baltic. The penned Soviet Baltic Fleet would be pounded by conventional bombing and Stukas, including the now-famous attack by Lt. Hans-Ulrich Rudel on the morning of 22 September, when he scored a direct hit on the battleship Marat with an SC1000 bomb.

Following the fall of Tallinn, the conquest of the Ösel (Saaremaa) and Dagö (Hiiumaa) islands, which controlled naval transit to and from the Gulf of Riga, was begun. They were heavily fortified by their Soviet garrison of more than 20,000 men, and two distinct plans had been formulated; Beowulf I, to be launched from Latvia, and Beowulf II from the western coast of Estonia. The Luftwaffe established an ad hoc command for support of the operation, named ‘Luftwaffe Command B’, under Generalmajor Heinz-Hellmuth von Wühlisch, and beneath this umbrella were KGr. 806 and Aufkl.Gr. 125 of Fliegerführer Ostsee, as well as 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906, which was transferred to von Wild’s command, joined by 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 on 21 September.