Voter Turnout and Participation in Other Political Activities

The C-SNIP Panel Survey collected information on two forms of political participation. One measure was derived from how active each student reported being in three different activities: contacting an elected official about an issue, participating in a march or protest, and working for a political campaign at any level of government (including student government campaigns). For each type of activity, students were asked to rate how many times they had participated over the previous year: “never,” “once,” or “more than once.” Participation in these activities was coded as the sum of the three activity scales.

A second measure of political participation was based on each student’s self-reported voter turnout in the 2004 presidential primary. Voting is similar to the other political activities described above in that each of these acts is motivated by the individual’s desire to influence the government. However, voting is treated separately in this analysis because it is the only behavior that allows citizens to have a direct voice in selecting their leaders. Moreover, despite declines in voter turnout over the past fifty years, voting differs from other political activities because it is the least costly and most widely participated in political act in the United States (Verba et al. 1995, 51).

Non-Political Civic Activity: Participation in Voluntary Membership Organizations

In total, this analysis accounts for seven different types of voluntary civic group affiliations: charitable and voluntary service; leadership and civic training; groups that "take stands on political issues or current events”; partisan groups; student government; student publications such as newspapers; and speech clubs and teams (e.g., forensics, debate). For each of these types of organizations, students were asked to rate how active they were on a 0-3 point scale, ranging from "not at all active” to "very active.” Participation is coded as the total amount of organizational activity in which each student engaged (i.e., the sum of the seven 0-3-point scales).

These voluntary civic organizations may from time to time engage in politically relevant activities. For example, members of the university’s student government might lobby the state legislature to provide more resources to the university, or a service organization dedicated to helping the homeless might lobby the local government to provide more shelters. Nonetheless, it is important to underscore that the act of participating in one of these voluntary civic organizations is distinct from engaging in one of the political activities described above. As discussed in Chapter 2, voluntary civic associations may be politically relevant. However, they are not classified as political activities because they do not directly influence the processes of governance (i.e., they do not involve citizens explicitly attempting to directly affect decisions made by the government or determine who is selected to run the government by influencing electoral outcomes).

Trends in Civic Participation across Activities

The data in Table 3.1 show that C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents participated in political activities far less frequently than in voluntary civic organizations. Overall, 5 percent of students reported that they had not participated in any voluntary civic membership organizations during high school, compared with 44 percent who claimed that they had not participated in any political activities. This trend continued into the first year of college, where 35 percent of students reported not participating in any voluntary organization activities, compared with 68 percent who reported not participating in any political activities.

Participants in the C-SNIP Focus Group Study provided a similar picture of the gap between political and non-political civic participation. When asked to describe the civic participation in which they had engaged during their first year of college, the vast majority of the activities mentioned by the focus group participants were non-political in nature. The one notable exception to this trend, however, was voting. Many of the focus group participants spontaneously mentioned that they had voted in the 2008 presidential primary, and the vast majority of participants reported that they had voted when specifically asked whether they had. As mentioned in a previous section, the majority of the focus group participants also reported that they had attended (or had attempted to attend) the large rally staged by Senator Barack Obama on February 13,

2008. The prevalence of voting and engagement with the 2008 primary elections makes sense, given the close proximity of the Wisconsin primary to when the focus groups were conducted and the broad appeal of the Obama campaign among young people.

Engagement with the 2008 election aside, what explains the sizeable gap between political participation and participation in voluntary civic organizations in these two student populations? A likely explanation for why these students are not politically active is because they are not politically engaged. For example, in the C-SNIP Panel Survey, subjects were asked, "In general, which do you think is the better way to solve important issues facing the country, through political involvement (for example, voting, working for political candidates, and the like) or through community involvement (for example, volunteering in the community, and the like)?” Students vastly preferred community involvement to political involvement in both high school (77%) and during their first year of college (72%).1 Not surprisingly, political engagement and political participation are related to each other. Students who cited "community involvement” as their preferred mode of civic activity were less active in political activities both in high school (t = -2.07, p = .04) and during their first year of college (t = -2.03, p = .05).

This said, while this student population was politically apathetic, it still adhered to civic-minded norms (for similar findings, see Zukin et al. 2006). For example, while political disengagement correlates with low levels of political participation, panel study respondents were equally likely to participate in voluntary civic organizations in high school (t = -.17, p = .87) and during the first year of college (t = -1.12, p = .27), regardless of whether they cited “political involvement” or “community involvement” as their preferred mode of civic expression. Moreover, when asked in wave 2 of the panel study, “How important do you think it is for people like you to be active and interested in politics and current events: very, somewhat, not very, not at all?” 91 percent of the respondents said that civic participation was somewhat or very important.2 In short, the C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents understood the virtues of participating in civil society. They did not, however, see politics as a desirable venue for such activity.

The focus group participants offered a similar assessment of the gap between political and non-political activity. A number of students mentioned that they were less engaged with politics than with non-political matters. These two comments especially illustrate this attitude:

I’m not exactly really involved in a politically affiliated group as far as, like, a party goes, but I do feel like it’s important to at least represent yourself in a number form [sic] with like humanitarian kind of things.

The reason I don’t get involved in a lot of these political groups, is I think it’s, like, really bureaucratic and not that effective. And as much as I care about it, I really don’t want to, you know, walk around posting fliers or handing out stickers or [sit] in a booth at whatever event. It seems, like, really boring, really boring.

In a similar vein, some students mentioned that they felt unqualified or unprepared to participate in political activities. As one student put it, “We don’t talk about political activities, because we don’t know about anything.” Or, as articulated in this exchange between the moderator and two participants:

MODERATOR: And how about the more political activities?

PARTICIPANT 1: I wish I could get involved in more. It’s just kind of overwhelming at first. There’s just so much stuff going on and stuff, so I’m interested in politics and stuff and even, like, the other side of politics. I don’t know. Hopefully, next year I’ll be a little bit more involved with that.

PARTICIPANT 2: I like to know what other people think about it, but I don’t know anything about it, so I feel stupid.

Low levels of political participation, engagement, and efficacy are not very surprising, given the relatively young age of the populations examined in the C-SNIP studies. As shown by the high number of politically inactive students reported in Table 3.1, these young people did not have extensive prior experience participating in political activities before coming to college.3 In contrast, the vast majority of the students in the study did have some form of prior experience participating in non-political civic activities—that is, only 5 percent reported that they had not participated in any civic organizations before coming to college, compared with 44 percent who reported that they had never participated in political activities before coming to college. Past patterns of civic behavior are meaningful because civic participation, like any other form of behavior, is habitual (Brady et al. 1999; Burns et al. 2001; Fowler 2006; Gerber et al. 2003; Plutzer 2002; Putnam 2000; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995). Since the students examined in this study did not gain extensive experience participating in political activities during high school, it is not surprising that they were not very active in or engaged with politics during their first year of college.

Trends in Civic Participation over Time

A second notable trend in Table 3.1 is that this population of students was less civically active during the first year of college than in high school. Data from the focus groups lead to a similar conclusion. When specifically asked to compare how civically active they had been in high school with how active they had been during their first year of college, the vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they had been more active during their high school years.

One explanation for this marked drop in participation between high school and the first year of college is that the first year of college is a period of significant transition in one’s life. After leaving home and family for college, young people are forced to adjust to a new and very different lifestyle as independent adults. Consequently, participation in civic activities should be expected to become less of a priority when a person needs to spend his or her time and energy learning how to navigate a new town, make new friends, learn how to study, and the like. Existing research in the fields of higher education, psychology, and political science offer support for this hypothesis. The transition to college has been documented to be a stressful and life-changing process as the student leans how to find his or her place in a new social and academic environment (Boyer 1987; Compas et al. 1986; Cutrona 1982; Takahashi and Majima 1994; Teren-zini et al. 1994). Moreover, studies have shown that civic engagement and participation drop during times of transition and relocation (Putnam 2000, 204).

Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey also offer evidence in support of this hypothesis. For example, in the first and second waves of the study respondents were asked, "How much free time have you had during the average week to participate in the types of organizations you answered questions about at the beginning of this survey: a lot of time, a moderate amount of time, very little time, or no time at all?” Survey participants reported having significantly less free time to dedicate to civic participation during their first year of college than they had in high school (t = -19.22, p < .01). Respondents were also asked, "Generally speaking, how much would you say that you know about politics and current events: a great deal, some, or not much?” Comparing the responses to this question given during the first and second waves of the survey shows that the students felt they were more informed about politics and current events during high school than they had been during the first year of college (t = 7.28, p < .01). In the first and second waves of the panel survey students were also asked, "How many days per week, on average, have you read or watched the news to learn about politics and current events?” Compared with their habits during high school, this population consumed significantly less news about politics and current events during the first year of college (t = -7.36, p < .01).

Do these measures help explain the participation gap between high school and the first year of college? Logically, we would expect that people with less free time would be less civically active. Time is a resource that is requisite for participation in civil society (Putnam 2000; Verba et al. 1995). However, the results in Table 3.2 show that available free time does not correlate with how civically active these students chose to be during their first year of college. The data do show, however, that political knowledge and news media usage are highly correlated with all three forms of civic participation. For this reason, declines in knowledge and media use between high school and the first year of college help explain declines in civic participation over this same time period.

TABLE 3.2 Free time, political knowledge, media use, and patterns of civic participation during the first year of college (correlations)

|

Civic activities |

Free time |

Knowledge about politics and current events |

News media usage |

|

Participation in voluntary civic organizations |

.05 |

.32*** |

.24*** |

|

Participation in political activities |

.05 |

.31*** |

.30*** |

|

Voter turnout (2004 presidential primary) |

.05 |

.22*** |

.20*** |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey. ***p < .01.

The idea that civic participation becomes less of a priority as people transition to life on their own at college was also a pervasive theme in the focus groups. Statements such as these were typical throughout the sessions:

In the beginning of the year, I was just kind of stressed with school and getting used to everything here, and I didn’t really pay attention to any of that kind of stuff.

I felt for the first, maybe first, semester, I was completely removed.

I stopped reading the news. I was just figuring stuff out and became busy. . . . [I]n addition, . . . a large part of my political involvement was, like, you know, talking with my family at dinner.

So mixing that up in a new environment [at college], it really caused me to do a lot less.

At the beginning of the year when we first got here, they had a club fair, but I was just so busy meeting people that I didn’t really think of it then.

While civic disengagement is a satisfying explanation for the drop in participation between high school and college, an additional explanation is the prevalence of service learning opportunities in American primary and secondary schools. These programs lower the costs of civic participation by providing prepackaged opportunities for students to become active. Moreover, the programs can raise the costs associated with not participating, because participation is often mandated as a requirement for graduation or course credit. Such programs became increasingly popular at the time that the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants were completing elementary and secondary school. On the federal level, these programs started receiving support when President George H. W. Bush enacted the National and Community Service Act of 1990, which created the Commission on National and Community Service (Public Law 101-610). The commission’s main duty was to create and support service learning programs. President Bill Clinton extended federal support for service learning programs by reauthorizing the National and Community Service Act under the National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993 (Public Law 103-82). This legislation merged a number of different agencies focused on civic involvement into the Corporation for National and Community Service. The act also established Learn and Serve America, a program that supports service learning programs.

In response to actions taken on the federal level, the American states have increased their commitment to providing service learning opportunities to school-age children. This has especially been the case in the State of Wisconsin, where 72 percent of the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants attended high school. For example, the state’s Department of Public Instruction established the Cooperative Educational Service Agency to promote service learning programs and to act as a liaison between schools and the federal Learn and Serve America program. The state also allows school districts to "require a pupil to participate in community service activities in order to receive a high school diploma” (Wisconsin Statute 118.33).

In summary, the populations studied in this book completed primary and secondary school as service learning education was growing in popularity across the United States. Moreover, the vast majority of the students had attended high school in a state where service learning is a requirement for graduation. Participating in mandatory service learning programs likely led these students to take part in an abnormally high number of activities during high school because civic activities are easier to engage in when opportunities to act are arranged for you or if sanctions are placed on those who choose not to participate (Olson 1965; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995). On entering college, these students no longer had built-in incentives to participate. Consequently, it is not surprising that participation levels fell after leaving high school.

The focus group participants corroborated the notion that civic participation was easier to engage in during high school because it was required or because structured opportunities were provided. A number of participants made comments such as these:

[I’m] a lot less involved now, I guess, just because in high school it was much more convenient, because it was either before or after class, so you’re already right there. It was just more of a clear-cut commitment.

I miss the structure. I think it’s in a way hurt me. Like, I have a lot of free time, and I don’t know what to do with it.

I think during high school I put more time into it only because I was in government class and we had hours required for that.

In a related vein, a number of students in the focus groups also appeared to be using their time at college to take a break from the civic participation requirements they were obliged to fulfill in high school.

I guess I kind of lost motivation for it. It used to be a mandatory part of my life to volunteer and be a part of things for school or other organizations. But now it’s, like, up to me, and I’d rather not.

I was student council president and stuff like that. I actually had a class hour dedicated to filling out forms and talking to people higher up than me, going and talking to everyone in their school and stuff. And I had to organize one volunteer thing a month and stuff like that. So I was very happy to get rid of all that and have time off from that.

I haven’t done as much this year, but I think it’s more like for my first year, I’m a freshman, and so I just, like, want to get settled in and not have to worry about that stuff as much. I figure I could do it later if I wanted to.

|

TABLE 3.3 The effect of civic talk on participation during the first year of college (regression analysis) |

in voluntary civic |

organizations |

|

Matched |

Unmatched | |

|

(1) |

(2) | |

|

Civic talk |

.81** |

.86*** |

|

(30) |

(.18) | |

|

Participation in voluntary civic organizations |

.22*** |

.25*** |

|

during high school |

(.03) |

(.02) |

|

Constant |

1.67 |

.78 |

|

(1.76) |

(1.20) | |

|

Adjusted R2 |

.13 |

.18 |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Model Type: Ordinary least squares (Imai et al. 2007c).

Note: Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044.

*p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? Survey Evidence

Participation in Voluntary Civic Organizations

To what extent does civic talk influence how active a person chooses to be in civil society? I begin to answer this question with a regression analysis of how active the C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents were in voluntary civic organizations during their first year of college (Table 3.3). To assess the effect of the matching data pre-processing procedure, the table presents results for both the matched and unmatched data sets. Also, to increase the precision of the analysis, each model controls for how active subjects had been in voluntary civic organizations during high school, before they engaged in civic talk with their roommate (i.e., a lag of the dependent variable), as well as for how the dormitory assignment process was executed (i.e., a fixed effect for each dormitory; these coefficients are omitted from the table because none were statistically significant).

Columns 1 and 2 of Table 3.3 show that subjects who engaged in civic talk with their randomly assigned roommates were more likely to participate in voluntary civic organizations during their first year of college. Substantively, the matched data set (column 1) shows that participation rates among subjects who engaged in civic talk were 38 percent higher than that of subjects who did not engage in civic talk (an increase from 2.1 to 2.9 on the voluntary organization participation scale).4 The estimated civic talk effect in the unmatched data set (column 2) is 45 percent (an increase from 2.0 to 2.9 on the voluntary organization participation scale), indicating that the influence of civic talk would have been overestimated if the matching process had not been applied to this analysis.5 Moreover, closer comparison of the civic talk coefficients in columns 1 and 2 shows that the matched data set produced a larger standard error. This shows that the matched data set produced a less certain, and therefore more conservative, estimate of the civic talk effect.

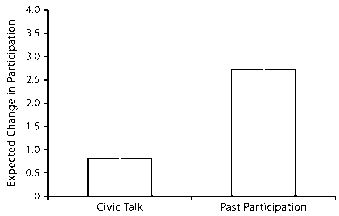

FIGURE 3.1 Comparing the effects of civic talk and past participation on participation in voluntary civic organizations during the first year of college

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. Figures are based on the matched data regression analysis in Table 3.3. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of participation in civic organizations estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means. The effect of past participation is calculated by comparing the estimated levels of participation for subjects who had average levels of prior experience with those who had the maximum level of prior experience, all other factors in the model held at their means.

To understand the magnitude of the effect that civic talk has on participation in voluntary civic organizations more clearly, Figure 3.1 compares the effect of civic talk to the effect of having participated in voluntary civic organizations in high school before engaging in civic talk in college (the lagged dependent variable). These results illustrate that, while the effect of civic talk is statistically significant, it is not as substantively large as that of prior participatory experience. In fact, the results in Figure 3.1 show that the effect of engaging in civic talk is less than half of the effect of having above average patterns of prior participatory experience. More detailed discussion of how the effect of civic talk compares with other antecedents of civic participation is taken up in Chapter 7.

Participation in Political Activities

While civic talk has a significant effect on participation in voluntary civic organizations, the results in Table 3.4 show that such conversations have a less reliable influence over whether a person participates in political activities. Comparing columns 1 and 2, we see that civic talk did not have a statistically significant effect on how politically active subjects were during their first year of college, regardless of whether the matched or unmatched data were used.

What explains this difference between participation in voluntary civic organizations and participation in political activities? The less reliable influence of civic talk on political participation is likely caused by the fact that the C-SNIP population is not politically active or engaged. As documented in Table 3.1, only 35 percent of the subjects reported that they did not participate in any voluntary civic organizations during their first year of college, while 68 percent reported that they did not participate in any political activities that year. Also recall that, with regard to their sense of political engagement, C-SNIP participants vastly preferred community involvement to political involvement as a means to solve important policy issues. Moreover, students who cited community involvement as their preferred mode of civic activity were less active in political activities, both during high school and during the first year of college. Keeping this in mind, it makes sense that civic talk has a less reliable influence on participation in political activities. If an individual is not willing to engage in an activity, influence from his or her social environment will likely have little effect on his or her behavior (Verba et al. 1995). This notion will be examined in greater detail in Chapter 5.

TABLE 3.4 The effect of civic talk on participation in political activities during the first year of college (regression analysis)

|

Matched (1) |

Unmatched (2) | |

|

Civic talk among roommates |

-.02 |

.05 |

|

(.09) |

(.07) | |

|

Participation in political activities |

.37*** |

.35*** |

|

during high school |

(.04) |

(.02) |

|

Constant |

.55 |

.50 |

|

(.76) |

(.46) | |

|

Adjusted R2 |

.24 |

.21 |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Model Type: Ordinary least squares (Imai et al. 2007c).

Note: Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044.

*p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

TABLE 3.5 The effect of civic talk on voter turnout during the first year of college (regression analysis)

|

Matched (1) |

Unmatched (2) | |

|

Civic talk among roommates |

.31t |

.45*** |

|

(.19) |

(.14) | |

|

Participation in political activities |

14** |

.10** |

|

during high school |

(.06) |

(.05) |

|

Constant |

-2.11 |

-.61 |

|

(2.20) |

(1.01) | |

|

Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) |

1,283 |

1,407 |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Model Type: Logistic regression (Imai et al. 2007d).

Note: Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). AIC is twice the number of parameters in the model, minus twice the value of the model’s log-likelihood. This diagnostic statistic is presented for logistic regression models throughout the book because the Zelig statistical computing package in R (Imai et al. 2007a) does not produce an R2 statistic for logistic models. Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044. tp = .12; *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

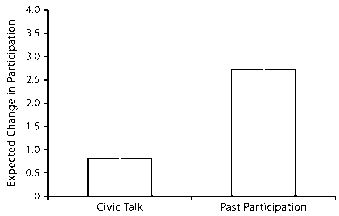

FIGURE 3.2 Comparing the effects of civic talk and past participation on voter turnout during the first year of college

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. Figures are based on the matched data regression analysis in Table 3.5. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the likelihood of voter turnout estimated among individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means. The effect of past participation is calculated by comparing the estimated levels of participation for subjects who had average levels of prior experience with those who had the maximum level of prior experience, all other factors in the model held at their means.

Voter Turnout

Table 3.5 provides an analysis of the effect of civic talk on voter participation. In this analysis, participation in other political activities is used as the measure of past experience because a sizeable portion of this student population was not eligible to vote before coming to college. In contrast to the relationship between civic talk and participation in other political activities, the results show that civic talk had a positive effect on voter turnout. Looking at the results from the matched data set in column 1, subjects who engaged in civic talk were 7 percentage points more likely to have voted in the 2004 presidential primary.6 The effect of civic talk on turnout increases to 11 percentage points if the unmatched data are used.7

Mirroring the analysis presented in Figure 3.1, Figure 3.2 compares the effect that civic talk had on voter participation to the effect of having engaged in political participation in high school, the lagged dependent variable used in the analysis presented in Table 3.5. Compared with the 7 percentage point boost in turnout in 2004 due to civic talk, the estimated increase in turnout due to past participatory experience is estimated to be 15 percentage points. However, after taking the uncertainty about these estimates into account, the data show that civic talk and past experience participating in political activities had the same magnitude of effect on the likelihood of turning out to vote.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? Focus Group Evidence

In line with the quantitative survey data, each of the focus group sessions showed that there is a meaningful relationship between civic talk and civic participation. However, most of the participants were not explicitly aware of this relationship. At the end of each focus group, participants were directly asked whether engaging in civic talk with their roommates had an effect on how civically active they were. The modal response was no; the most common explanation offered for why these students chose to participate in civic activities was their own internal interest and motivation. A number of focus group participants made statements such as, "My choices were because of my own choices,” "If I’m going to involved, I’ll just, like, do it myself,” and "Because what [my roommate] does seems really boring to me, I don’t want to get involved.” In a related vein, other participants stated that they felt that their roommates did not have an effect on them because they did not agree with their roommates’ views on politics and current events. As one student summarized, "We both have different opinions, and I’m going to do what I want; she’s going to do what she wants. So . . . we don’t really influence each other so much.”

In thinking about why many of the focus group participants did not see the causal link between civic talk and civic participation, it is worth noting that directly asking people whether their social environment has an influence on how they behave may be a biased method for measuring the effect of civic talk. This is the case because human beings tend to attribute positive behaviors to their own qualities (and, conversely, negative behaviors to their environment). This is an example of what social psychologists refer to as the "self-serving motivational attribution bias” (see, e.g., Bernstein et al. 1979; Bradley 1978; Lau and Russell 1980; Reifenberg 1986; Ross and Fletcher 1985). For example, studies show that when asked to explain the grades they received, high-achieving students cite their hard work and intelligence, while students attribute low grades to external factors such as the difficulty of the test or "bad luck” (Bernstein et al. 1979; Reifenberg 1986). Thus, since civic participation is generally seen as a positive behavior in which to engage—recall that 91 percent of the C-SNIP

Panel Survey respondents said that civic participation was important— it is not surprising that most of the focus group participants wanted to attribute their civic participation to their own desires rather than to the influence of their social environment.

This said, while the modal focus group participant did not explicitly acknowledge the link between civic talk and civic participation, a vocal minority of focus group participants did report that discussing politics and current events with their roommates had a direct effect on how civically active they were during their first year of college. For example, participants in each of the focus groups mentioned that engaging in civic talk caused them to become more interested in politics and current events. Other students mentioned that talking about the state of the environment with their roommates caused them to become more conscious about recycling and energy conservation. Other participants reported that their roommates had reminded them to vote in the 2008 presidential primary. One student even reported that he felt he might have caused his roommate to shift his choice in the primary election from a Republican candidate to Barack Obama.

In addition, before being directly asked whether civic talk with their roommates influenced how civically active they were during the first year of college, many of the participants in the focus groups indicated that this was the case without explicitly saying so. For example, many of the focus group participants reported that either they or their roommates had asked the other to get involved in a civic activity. Based on the proximity of the focus group sessions to the 2008 presidential primary election in Wisconsin, the most commonly mentioned events that roommates encouraged each other to go to or attended together were the Obama rally on February 13, 2008, and the presidential primary election. A number of participants also reported that they had attempted to persuade their roommates in some way about politics and current events. Again, based on the proximity in time of these groups to the 2008 presidential primary in the Wisconsin, most of the persuasion discussions were about the election and the candidates.

Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter is to document the causal relationship between civic talk and participation in civil society. Using quantitative panel survey data, in concert with qualitative focus group data, the evidence shows that civic talk can have a causal influence on how citizens participate in the processes of self-governance. This is the case even after accounting for how civically active subjects were before they engaged in civic talk, arguably one of the best measures of an individual’s predilection to participate in civic activities.

While civic talk has a meaningful effect on civic participation, however, it is essential to underscore that the results of this study do not suggest that sociological explanations of civic participation are a substitute for individual-level explanations. On the contrary: The C-SNIP data show that, depending on the act in question, the effect of civic talk on civic participation can be less than that of having prior participatory experience. The focus group data also show that while civic talk has an effect on how active individuals are in civil society, most people are not explicitly aware that this relationship exists. Instead, the majority of people attribute their patterns of behavior to their personal attributes instead of to the nature of their social context. Thus, the results presented in this chapter show that, to understand how contemporary participatory democracy functions, both social-level and individual-level antecedents of civic participation need to be considered. Neither factor on its own is a sufficient explanation of why an individual chooses to participate in civil society.

It is also important to note that while the main purpose of this chapter is not to assess how the influence of civic talk varies under different conditions, the results lend themselves to some initial conclusions. Both C-SNIP studies show that civic talk has a larger and more reliable effect on behavior in which individuals are predisposed to engage. For example, because the subjects in the study were not politically active or engaged, civic talk had no detectable influence on whether they participated in political activities. This question of how the relationship between civic talk and civic participation varies under different circumstances will be addressed in greater detail in Chapters 5 and 6.

In addition, while the evidence presented in this chapter shows that there is a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation, it does not show why this is the case. That is the subject of the next chapter.

Why Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation?

[My roommate] was voting on the primary day and I, like, wasn’t really planning on it just because I felt like I didn’t really know enough. I mean, I knew, I guess; I knew enough. But I was just, like, "No. I don’t even want to.” But she encouraged me to, and I did.

I feel a lot more interested. I really didn’t talk much politics in high school with anybody, and coming here, it’s, like, "Holy cow!

We’re in the capital [city of Wisconsin], and everyone talks about politics all the time where I’m living.” So I think I’ve gained interest from talking to people.

—C-SNIP Focus Group Study participants

The previous chapter presented evidence of the causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey show that civic talk increased participation in voluntary civic organizations by 38 percent. These same data show that civic talk also increased the likelihood of turning out to vote by 7 percentage points. The positive effect of civic talk on civic participation appears, however, to be contingent on the individual’s motivation to participate. For example, the C-SNIP Panel Survey shows that civic talk had little effect on participation in political activities such as protesting, contacting elected officials, and political campaign work. This appears to be the case because the student population examined in this study is not politically active or engaged. Evidence from the qualitative focus groups led to the same conclusion.

While the previous chapter shows that there is a meaningful relationship between civic talk and civic participation, talk in and of itself cannot be what is driving individuals to participate. Talk about politics and current events must be generating other forces that encourage us to act. Therefore, the next logical step in this analysis is to determine what these other forces are. In this chapter, evidence from the C-SNIP Panel Survey and Focus Group Study are used to show that when we talk about politics and current events with our peers, we are asked by them to participate in civil society. These data also show that civic talk makes us more engaged with politics and current events.

Why Do We Participate in Civic Activities?

In attempting to answer why civic talk causes civic participation, it is necessary to ask why people choose to participate in civic activities in the first place. With this knowledge, we can determine what types of evidence are needed to assess why conversations about politics and current events lead individuals to participate in civic activities.

The simplest answer to this question is that the decision to participate is determined by the costs and benefits associated with participating. If the benefits outweigh the costs, a person is more likely to choose to participate (Downs 1957; Olson 1965; Verba et al. 1995). One of the most prolific articulations of this argument appears in Anthony Downs’s analysis of voter turnout in An Economic Theory of Democracy (1957). Downs shows that an individual decides whether to vote by comparing the costs associated with voting (e.g., time and energy) to the potential benefit of his or her vote being the decisive one in the election. On that basis, Downs concludes that voting is an irrational act, since even in small electorates any one vote is unlikely to be decisive. Mancur Olson offers a similar argument in his seminal examination of interest-group politics, The Logic of Collective Action (1965). He shows that individuals are more likely to contribute their time and money to an interest group if they receive selective benefits (i.e., excludable benefits that are only given to those who contribute to the group) to offset the costs associated with participation. Without such inducements, we have an incentive to “free ride” in the hope of receiving the public (i.e., non-excludable) benefits of interest groups’ lobbying without having to incur the costs associated with contributing to the effort.8

While the calculus of deciding whether to participate in civil society can easily be distilled down to a question of costs and benefits, it is necessary to dig deeper and ask what factors determine how costly and how beneficial it is to engage in civic activities. The extant literature on civic participation suggests four factors that drive the costs and benefits associated with civic participation: resources, civic engagement, recruitment, and norms.9

To illustrate how resources might help explain the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, consider the various factors that determine whether a person decides to vote. Information about the candidates and the issues at stake in the election is the most basic resource that this person would need to decide whether to vote (Popkin 1995). This is the case because when such informational resources are readily available, the act of voting becomes less costly. For example, the task of deciding who to vote for is easier if you already know the policy positions of the candidates in the race. Moreover, information can make the task of voting more beneficial. Information allows voters to cast their ballots for candidates who best support their preferences. Thus, if the candidate a voter selected wins an election and faithfully pursues the policy agenda on which he or she campaigned, this is beneficial to the voter.

Individuals can obtain civically relevant information from a number of sources. For example, our hypothetical voter could gather information by monitoring the news media, attending political rallies, sifting through pieces of direct mail sent by candidates and interest groups, and the like. However, this individual might also obtain information through conversations about politics and current events with the members of his or her social network (Conover et al. 2002; Downs 1957; Huckfeldt et al. 2000; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995; Lazarsfeld et al. 1968; McClurg 2003; Popkin 1995; Walsh 2004). One benefit associated with seeking information in one’s social network is cost reduction. For example, talking about the current election over coffee with a friend is an easier way for an individual to obtain information than taking the time to read a newspaper. In addition to being lower in cost, obtaining information from our peers is likely to be enjoyable. For example, an individual is more likely to enjoy discussing politics over a dinner out with friends than going to a candidate’s rally filled with strangers.10

Being civically engaged—having an interest in politics and current events and a sense of political efficacy—also motivates civic participation. This is the case even after accounting for how rich in resources a person is (Verba et al. 1995). Consider our hypothetical voter again. Regardless of how much information this person has on the campaign and the candidates, this citizen is unlikely to vote if he or she is not interested in politics and current events or if he or she does not feel that his or her vote will matter (Verba et al. 1995).

Civic engagement makes voting and other forms of civic participation easier to engage in largely by increasing the benefits associated with participation. For example, because any one vote is rarely decisive in an election, the tangible benefits of voting are largely non-existent (Downs 1957). However, if individuals are imbued with a strong sense of civic engagement, they will nonetheless find psychological satisfaction in voting because they are fulfilling their sense of civic duty. Moreover, because of their interest in politics and sense of political efficacy, the civically engaged among us are less likely to be concerned about the costs associated with participating in civic activities. For example, the opportunity cost of lost time at work in order to vote is likely to be perceived as less severe by individuals who are interested in politics and current events.

As with information, civic talk could increase an individual’s level of civic engagement. For example, talking about politics and current events in an informal social setting could lead an individual to learn about and become more interested in participating in civic activities (McClurg 2003). Extant research also shows that experiences in the family and in the school help solidify the political interest and efficacy that individuals carry with them for the rest of their lives (see, e.g., Verba et al. 1995). Perhaps interactions in collegiate peer groups, such as those documented in the C-SNIP data sets, do the same.

Even the most engaged and resource-rich individuals among us will be more likely to participate in civic activities if they are mobilized by someone else to act (Gerber and Green 2000; Nickerson 2008; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995). Consider our hypothetical voter again. This individual will be more likely to vote if he or she is motivated to do some by someone else (Gerber and Green 2000; Nickerson 2008; Rosen-stone and Hansen 1993).11 Recruitment is effective at eliciting civic participation because it makes the process of taking action less costly. For example, if a political party volunteer offers to give you a ride to the polls, the task of voting becomes much easier for you. Moreover, in some circumstances recruitment might affect the benefits associated with civic participation. For example, if a religious leader asked his or her parishioners to vote, those individuals might feel obliged to do so to maintain the benefit of membership in good standing in the church.

Existing research suggests that the face-to-face style of recruitment that one would expect to arise out of peer networks may be especially effective at eliciting civic participation (Brady et al. 1999; Gerber and Green 2000; Godwin and Mitchell 1984; Klofstad 2007). For example, through an experimental study of voters in New Haven, Connecticut, Gerber and Green (2000) show that door-to-door neighborhood canvassing is more effective at stimulating voter participation than less direct methods such as phone calls and pamphlets sent through the mail. In a similar vein, Brady and his colleagues (1999, 157) hypothesize that "recruiters who have a close relationship to their prospects should have two advantages: They are more likely to have information about the activity potential of the target and more likely to have the leverage that makes acquiescence to a request probable.” Their analysis offers support for this hypothesis; recruitment to participate in political activities was estimated to be 28 percent more effective if the target was already acquainted with the recruiter.

Social Norms

Finally, social norms—"beliefs about which behaviors are acceptable and which are unacceptable for specific persons in specific situations” (Michener and DeLamater 1999, 64)—can have a powerful effect on individual behavior (Crandall 1988; Festinger et al. 1950; Latane and Wolf 1981; Mendelberg 2002; Michener and DeLamater 1999; Putnam 2000; Schachter 1959). For example, consider once again a hypothetical voter who is fully stocked with resources, engagement, and recruitment. This individual is already going to be quite likely to vote but will be even more likely to do so if he or she adheres to civic-minded norms. For example, Putnam (2000) shows that Americans were more civically active when norms of social trust and reciprocity were more prevalent in society. Such norms, he argues, lead individuals to be integrated into events and issues outside their own personal sphere. In other words, pro-civic norms make civic participation more beneficial, since the individuals that adhere to them feel the need to contribute to wider society. Moreover, when norms dictate that civic participation is a necessary activity in a society, violating those rules by failing to participate is costly to the social deviant (e.g., one experiences "cognitive dissonance”—a sense of psychological discomfort— over having violated the norm).

Norms are especially germane to the study of civic talk among peers because, along with the family and the school, the peer group is one of the most important transmitters of social norms that an individual encounters during his or her lifetime (Beck 1977; Dawson et al. 1977; Michener and DeLamater 1999; Silbiger 1977; Walsh 2004). Findings from the field of social psychology suggest why this is the case. Research by Latane and Wolf (1981) on social impact theory shows that social influence is stronger when the socializing agent is close and sustained—what they term "immediate”— the way a peer group is. In a similar vein, Festinger and his colleagues (1950, 163) show in their seminal examination of social interaction in a student housing unit at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that "it is through the small face-to-face groups that many attitudes and ideologies which affect our behavior are transmitted.” Thus, because social networks are typically composed of close and sustained social relationships, they can be expected to have normative influence on their members. If peers transmit civic-minded norms during civic talk discussions, looking for these norms in peer networks might help explain how civic talk leads individuals to participate in civic activities.

Why Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? Survey Evidence

RESOURCES

To see if the transfer of informational resources occurs among peers, C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents were asked, "How many times have your roommates given you any information about how to become active in politics and current events: often, sometimes, rarely, or never?” On average, students reported exposure to such information somewhere between "never” and "rarely” (an average of .4 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "never” to "often”).

ENGAGEMENT

Increased civic engagement as a consequence of civic talk was first measured by asking, "Thinking about how interested you were in politics and current events before you came to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has talking with your roommates increased your interest in politics and current events: very much, somewhat, not that much, or not at all?” On average, students reported enhanced engagement somewhere between "not at all” and "not that much” (an average of .7 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "not at all” to "very much”). A second measure of civic engagement is based on each student’s level of political efficacy, measured with the survey question, "How much would you agree or disagree with this statement: ‘People like me don’t have any say about what the government does’: strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree?” On average, students reported that they neither agreed nor disagreed with the idea that they do not have a say in what the government does (an average of 3.4 on the 1-5 scale ranging from "strongly agree” to "strongly disagree”).

RECRUITMENT

Peer-to-peer recruitment was measured by asking, "How many times have your roommates asked you to participate in an event or organization related to politics and current events: often, sometimes, rarely, or never?” On average, students reported enhanced engagement somewhere between "never” and "rarely” (an average of .3 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "never” to "often”).

SOCIAL NORMS

While norms are rules of social conduct, they typically are not formally codified. This leaves us in danger of misusing the concept as a "garbage can” to explain a host of different phenomena that may or may not actually be attributable to norms. Therefore, to develop a multidimensional picture of the potential impact of norms on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, this analysis uses two different measurement strategies: behavioral modeling and civic-minded attitudes.

Norms are often learned by observing and modeling the behavior of others (Crandall 1988; McClurg 2004; Michener and DeLamater 1999). Accordingly, one measure of norms used in this analysis is the individual’s perception of his or her peers as measured by the question, "How active and interested do you think your roommate is in politics and current events: very, somewhat, not very, or not at all?” Under the assumption that individuals learn how to behave by observing the actions of others, this measure serves as a proxy for civic norms by capturing how civically active an individual’s roommate is. On average, students reported that they thought their roommates were "not very” to "somewhat” active (a mean of 1.4 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "not at all” to "very”).

A second measure of norms focuses on attitudes rather than behaviors. This measure was calculated as each respondent’s response to the question, "How important do you think it is for people like you to be active and interested in politics and current events: very important, somewhat important, not very important, or not at all important?” The expectation is that if an individual begins to feel that civic participation is important as a consequence of engaging in civic talk, he or she may feel pressure to become more active in civil society. On average, respondents felt that civic engagement and participation is somewhere between "somewhat” and "very” important (a mean of 2.3 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "not at all” to "very”).

TABLE 4.1 Explaining the civic talk effect (correlations)

|

Causal mechanisms |

Civic talk among roommates |

Participation in voluntary civic organizations |

Political participation |

Voter turnout |

|

Resources |

.38*** |

.15*** |

.09*** |

.10*** |

|

Engagement Interest in politics and current events |

.45*** |

.13*** |

.10*** |

12*** |

|

Political efficacy |

11*** |

14*** |

!4*** |

11*** |

|

Recruitment |

.31*** |

.16*** |

12*** |

.09*** |

|

Norms Perceived activity/interest level of roommate |

40*** |

.03 |

-.01 |

.07*** |

|

Perceived importance of civic participation |

.18*** |

20*** |

.22*** |

.16*** |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey. ***p < .01.

Basic Correlations

If resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms help explain how civic talk influences us to participate in civic activities, these factors should correlate with both the amount of civic talk occurring in the peer network and the amount of civic participation in which a person engages. The results in Table 4.1 support this expectation. Civic talk correlates with information transfers, increased psychological engagement with politics and current events, enhanced political efficacy, instances of recruitment, and the acceptance of pro-civic norms. In turn, resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms correlate with higher levels of civic participation. Some of these correlations are not extraordinarily large, but they are all positive and statistically significant.

The only exception in Table 4.1 is the perception of how active and interested one’s roommate is in civic activities. These results show that students who engaged in civic talk became aware that their roommates were active and interested in civic activities, which makes sense. If someone you know frequently discusses a certain topic, it is safe to assume that he or she is interested in that subject. However, knowing that their roommates are active and interested in civic activities appears to have little influence over how active students are in civil society. This suggests that behavioral modeling is not likely to be a mechanism that governs the relationship between civic talk and civic participation.

Multivariate Analysis: "Explaining Away" Civic Talk with Causal Mechanisms

The correlations listed in Table 4.1 are necessary evidence for resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms to be viable explanations of the civic talk effect. If there are no bivariate statistical relationships among these four factors, civic talk, and civic participation, it is unlikely that they are acting as the mechanisms that cause individuals to translate talk into action. However, to validate these findings with more sufficient evidence, it is useful to turn to a multivariate analysis.12 To test whether resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms help explain the civic talk effect, measures of these concepts were added to the regression analyses presented in Chapter 3. The goal of adding these variables to the model is to “explain away” the civic talk effect. If resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms explain how we translate discussions about politics and current events with peers into civic participation, the civic talk coefficient should drop in value after these variables are added to the model. This will only occur if resources, engagement, and recruitment account for the variance in civic participation that was once accounted for by civic talk.13

The result of this analysis on participation in voluntary civic organizations is presented in Table 4.2. The results show that resources, engagement, recruitment, and civic-minded norms help explain the civic talk effect. For each causal mechanism, the civic talk regression coefficient drops in value after adding the causal mechanism variable to the analysis. However, unlike the civic talk coefficient, the lagged dependent variable coefficient is not affected when the causal mechanism variables are added. As anticipated, then, in this analysis the addition of resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms accounts only for the variance once explained by civic talk.

Closer examination of the causal mechanism coefficients in Table 4.2 gives us greater insight into how individuals translate civic talk into civic participation. Moving from the left to the right in the table, adding resources to the analysis in column 2 led to the second-largest drop in the value of the civic talk coefficient (15 percent). However, the direct effect of resources on participation in voluntary organizations is uncertain, since the resource coefficient is not statistically significant. Column 3 shows that adding interest in politics and current events to the analysis only led to a 5 percent drop in the value of the civic talk coefficient. Moreover, the interest coefficient itself is not statistically significant. The efficacy measure of civic engagement (column 4) also led to a 5 percent decline in the civic talk coefficient. However, unlike interest, the efficacy coefficient is statistically significant. Adding the recruitment measure to the regression analysis in column 5 led to the largest decline in the value of the civic talk coefficient (17 percent). Moreover, the recruitment coefficient itself is statistically significant. Finally, adding civic-minded norms in column 6 only caused a 6 percent decline in the value of the civic talk coefficient. However, the coefficient is statistically significant, showing that norms have a more stable relationship with participation than do resources and interest in politics and current events.14

|

TABLE 4.2 Explaining the effect of |

civic talk |

on participation in |

voluntary | |||

|

civic organizations during the first year of college (regress |

ion analysis) | |||||

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) | |

|

Civic talk among |

.81** |

.69* |

.77** |

.77** |

.67* |

.76** |

|

roommates |

(.30) |

(33) |

(.31) |

(.31) |

(33) |

(.32) |

|

Participation in voluntary |

22*** |

.22*** |

.22*** |

.21** |

.22*** |

.21*** |

|

civic organizations |

(.03) |

(.03) |

(.03) |

(.03) |

(.03) |

(.03) |

|

during high school | ||||||

|

Causal mechanisms | ||||||

|

Resources |

.23 | |||||

|

(.20) | ||||||

|

Engagement | ||||||

|

Interest in politics |

.06 | |||||

|

and current events |

(16) | |||||

|

Political efficacy |

.26** | |||||

|

(.11) | ||||||

|

Recruitment |

.50* | |||||

|

(25) | ||||||

|

Norms (perceived |

.72*** | |||||

|

importance of |

(.23) | |||||

|

civic participation) | ||||||

|

Constant |

1.67 |

1.66 |

1.65 |

.94 |

1.53 |

-.15 |

|

(176) |

(178) |

(176) |

(1.85) |

(174) |

(1.88) | |

|

Adjusted R2 |

.13 |

.13 |

.13 |

.14 |

.14 |

.15 |

|

Percent change in |

-15 |

-5 |

-5 |

-17 |

-6 | |

|

civic talk coefficient | ||||||

|

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey. | ||||||

|

Model Type: Ordinary least squares (Imai et al. 2007c). | ||||||

Columns: (1) Base model. (2)-(6) Base model with addition of individual causal mechanisms as indicated within the body of the table.

Note: Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). The matched data set is used in this analysis (see Appendix C). Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044.

*p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Table 4.3 applies the same style of analysis to the case of voter turnout. Again, the results show that adding the four causal mechanisms helps explain the effect of civic talk on civic participation. In fact, the causal mechanism variables appear to do a better job of explaining the relationship between civic talk and voter turnout. The average reduction in the civic talk coefficient is 19 percent in the analysis of voter turnout, compared with 10 percent in the analysis of participation in voluntary civic organizations.

TABLE 4.3 Explaining the effect of civic talk on voter turnout during the first year of college (regression analysis)

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) | |

|

Civic talk among |

. 311 |

.23 |

.19 |

.28 |

.27 |

.29 |

|

roommates |

(.19) |

(.21) |

(.19) |

(.18) |

(.18) |

(.19) |

|

Participation in political |

14** |

14** |

14** |

.13** |

14** |

.12** |

|

activities during |

(.06) |

(.06) |

(.06) |

(.06) |

(.06) |

(.06) |

|

high school Causal mechanisms | ||||||

|

Resources |

.17 (.12) | |||||

|

Engagement | ||||||

|

Interest in politics and current events Political efficacy Recruitment Norms (perceived importance of |

.19* (.11) |

.19*** (.07) |

.16 (.17) |

.32* (.16) | ||

|

civic participation) | ||||||

|

Constant |

-2.11 |

-2.12 |

-2.18 |

-2.67 |

-2.16 |

-2.87 |

|

(2.20) |

(2.20) |

(2.21) |

(2.29) |

(2.19) |

(2.19) | |

|

Akaike’s information |

1,283 |

1,282 |

1,280 |

1,276 |

1,283 |

1,278 |

|

criterion (AIC) | ||||||

|

Percent change in |

-26 |

-39 |

-10 |

-13 |

-6 | |

civic talk coefficient

As with Table 4.2, closer examination of each column in Table 4.3 gives greater insight into how each of these causal mechanisms functions. Moving from left to right in the table, adding informational resources in column 2 reduced the civic talk coefficient by 26 percent. However, the information coefficient is not significant. In column 3, adding interest in politics and current events to the analysis led to the largest decline in value of the civic talk coefficient (39 percent). Moreover, the interest coefficient meets a minimal standard for statistical significance. The direct influence of political efficacy on voter turnout (column 4) is also statistically significant. However, efficacy has far less of an effect on the civic talk coefficient (a 10 percent decline in value) than interest in politics and current events. Adding recruitment to the analysis in column 5 leads to a 13 percent decline in the value of the civic talk coefficient. However, the recruitment coefficient is not statistically significant. Finally, as in the analysis of voluntary civic memberships, adding norms to the analysis in column 6 led to only a 6 percent decline in the voter turnout civic talk coefficient. However, the norms coefficient is statistically significant, showing that norms have a more systematic impact on voter turnout than resources or recruitment.15

Differences between Voluntary Civic Organizations and Voting

All four causal mechanisms offer some level of explanation of the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. However, in the case of participation in voluntary organizations, recruitment plays the largest and most consistent role in explaining this relationship. In contrast, civic engagement carries more of the explanatory load for voter turnout.

This difference makes sense considering the uniqueness of the vote as a civic act. Since the probability that any one vote will affect the outcome of an election is small (Downs 1957), very few tangible benefits are associated with voting. Consequently, a prospective voter must be motivated by a sense of civic engagement to see the benefit of participating. In contrast, participation in the voluntary civic organizations examined in this study (i.e., student groups) comes with tangible benefits. For example, students receive social (i.e., "solidary”) benefits because they get to socialize with each other as they participate in student organizations. Participation in voluntary student organizations also allows individuals to build their resumes. Thus, it makes sense that being recruited to participate in this form of civic activity caries more explanatory weight than being civi-cally engaged.16

These figures are commensurate with national samples of college students: see, e.g., Harvard University Institute of Politics 2000.

This question was not asked of students in the high school questionnaire.

This lack of experience is sometimes legally mandated, as in the case of the right to vote being extended at age 18.

This and other substantive interpretations of regression coefficients presented in this book were calculated with the setx and sim procedures in the Zelig package for R (Imai et al. 2007a, 2007b). Unless otherwise indicated, throughout this book all other factors included in the analysis are held at their means when calculating such estimates.

This said, it is worth noting that the matching procedure did not drastically affect the results; the civic talk effect was statistically significant regardless of whether the matching procedure was used. Since the procedure worked correctly by significantly improving the similarity between individuals who did and did not engage in civic talk (see Appendix C), this could mean one of two things (or both). First, the use of panel data and random assignment of roommates, on their own, could have reduced the biases that are assumed to exist in studies of social networks. Alternatively, the small differences between the matched and unmatched results could indicate that biases thought to be present in social network studies are not as virulent as critics believe they are.

While the significance of the civic talk coefficient falls just below the 90 percent confidence threshold, the expected increase in turnout is estimated to be significant at the 95 percent level (see Figure 3.2).

Again, it is worth noting that the matching procedure did not drastically affect the results. See fn. 7 for an explanation of why this is the case.

For example, if an environmental interest group successfully lobbies for clean air legislation, everyone can enjoy the benefits of cleaner air regardless of whether they contributed to the cause.

Three of these factors—resources, engagement, and recruitment—make up Verba and colleagues’ (1995) "Civic Voluntarism Model.” Using survey data on the participatory habits of American citizens, Verba and his colleagues found that each of these three factors has an independent effect on the likelihood of becoming civically active.

Otherwise stated, and as discussed in Chapter 2, the political content we get from conversations with our peers is typically a "byproduct” of social interactions based on non-political goals such as socializing.

In fact, Rosenstone and Hansen (1993) show that about 50 percent of the drop-off in voter turnout in the United States between the 1960s and the 1980s was caused by declines in face-to-face mobilization, such as neighborhood canvassing, by the political parties.

The perceived activity/interest level of one’s roommate was omitted from this analysis because this variable does not correlate significantly with how active one chooses to be in most civic activities (see Table 4.1).

Campbell and Wolbrecht (2006) use the same technique to explain the relationship between greater numbers of women serving in elected office and greater levels of political engagement among female adolescents. As a germane side note, Campbell and Wolbrecht find that the mechanism that links these two phenomena together is political discussion within the family.

These results hold if all of the causal mechanism variables are added to the model simultaneously.

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Model Type: Logistic regression (Imai et al. 2007d).

Columns: (1) Base model. (2)-(6) Base model with addition of individual causal mechanisms, as indicated within the body of the table.

Note: AIC is twice the number of parameters in the model, minus twice the value of the model’s log-likelihood. Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). The matched data set is used in this analysis (see Appendix C). While the significance of the civic talk coefficient in column 3 falls just below the 90 percent confidence threshold, the expected increase in turnout is estimated to be significant at the 95 percent level (see Figure 3.2). Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044. tp < .12; *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Again, these results hold if all of the causal mechanism variables are added to the model simultaneously.

A related explanation is that the measure of civic engagement used in this analysis is interest in politics and current events. Since the voluntary civic organizations assessed in this study are largely a-political, it makes sense that interest in politics and current events has less of an effect on participation in voluntary civic organizations than on voting.

and the like. A few focus group participants also reported that they or their roommates had explicitly mentioned how to become involved in those activities.17

This phenomenon is considered in more detail in the section on evidence of recruitment gathered in the focus group sessions.