CHAPTER 3

The True Cost of Caring for Our Veterans

THE IRAQ WAR has placed an unremitting burden on our troops in the field. More than half of those who serve are under twenty-four; some are barely out of high school. Many have been required to remain on active combat duty far longer than their original commitment. Of the total number so far sent to Iraq, some 36 percent have been drawn from the National Guard and Reserves—men and women who typically have to leave husbands, wives, jobs, and small children at home.1 While on duty there is no place to get away from the incessant fighting and the constant threat of death.

This group of men and women also contains an unprecedented number who have been wounded or injured and survived.2 The Vietnam and Korean wars saw 2.6 and 2.8 injuries per fatality, respectively. World War I and World War II had 1.8 and 1.6 wounded servicemen per death, respectively. In Iraq and Afghanistan, the ratio is more than 7 to 1—by far the largest in U.S. history. If we include non-combat injuries, the ratio soars to 15 wounded for each fatality.3

In round numbers, this means that by the end of November 2007, some 67,000 U.S. troops had suffered wounds, injuries, or disease in Iraq and Afghanistan. True, some of these non-battlefield injuries would have been incurred even if the individuals had been on peacetime duty. But the American taxpayer will still have to pay the cost of their disability compensation and medical care, regardless of how they were injured. We have estimated that at least 45,000 of the injuries and diseases are directly attributable to the current conflict, based on an analysis of casualties during the five years before and the five years subsequent to the invasion of Iraq. This includes a 50 percent increase in the rate of injuries that occur outside of combat (such as vehicle crashes, aircraft accidents, and other non-battle injuries).4

By August 2007, two thirds of those who were medically evacuated from Iraq were victims of disease.5 Thriving on the troops’ crowded and sometimes unsanitary living conditions, microbial pathogens have caused diarrheal illnesses and acute upper-respiratory infections in Iraq and Afghanistan, similar to diseases seen during the first Gulf War. A number of military personnel have suffered various insect-borne diseases (leishmaniasis, a potentially fatal bloodborne disease transmitted by the bite of a sandfly, has afflicted thousands of U.S. troops), as well as nosocomial infections, brucellosis, chicken pox, meningococcal disease, and Q fever.6 Smaller numbers of servicemen and women have had serious adverse reactions to the anthrax vaccine, antimalaria Lariam pills, and other mandatory medications.

Finding these numbers has not been as easy as it should, because the Defense Department is highly secretive about the true number of casualties. While it reports deaths of servicemen and women from both combat and non-combat operations, the DOD’s official casualty record lists only those wounded in combat. The department maintains a separate, hard-to-find tally of troops wounded during “non-combat” operations, a figure that includes those injured during vehicle and helicopter crashes and training accidents, as well as those who succumb to a disease or physical or mental illness during deployment that is serious enough to require medical evacuation to Europe. (Even this tally does not include troops with non-battle injuries who are not airlifted out.) The military has considerable discretion in defining any injuries as combat-related—and some incentive to label them non-combat because it does not want to credit the enemy with a success. Thus, helicopter crashes that take place at night may not be included (even though it is unsafe to travel during the day) unless it is known with certainty that the craft was shot down by enemy fire. We found this list almost accidentally when the Department of Veterans Affairs published a complete casualty tally on its “Fact Sheet: America’s Wars” in September 2006, which was linked to the full DOD source of data for all combat and non-combat casualties. Since Bilmes published her initial paper in January 2007, the DOD has insisted that the VA use only the combat casualty figures reported on DOD’s main Web site, and the military’s newly reorganized second site makes it difficult to locate and interpret the full casualty report. Despite these efforts at obfuscation, veterans’ organizations have successfully used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain access to the full set of data and to circulate it to Congress and to the public.7

The enormous jump in survival rates we mentioned earlier is a tribute to advances in battlefield medicine, but it has budgetary consequences which the government has consistently failed to anticipate. All veterans, regardless of how their injuries were inflicted, are eligible for disability pensions and other benefits (including medical treatment, long-term health care, pensions, educational grants, housing assistance, reintegration assistance, and counseling). There are large costs, both for providing such benefits and for administering the programs. And underfunding can have serious consequences for the veterans—and even raise long-term costs. Currently, for instance, a combination of understaffing, poorly designed systems, and administrative incompetence has meant that there are frequently glitches in moving veterans off the DOD payroll and onto the VA payroll to obtain disability benefits. Not only do the increased needs of new veterans mean that sometimes they do not get the care they need; often they get served only by crowding out older veterans, who must wait longer—or may never get the care they need.8

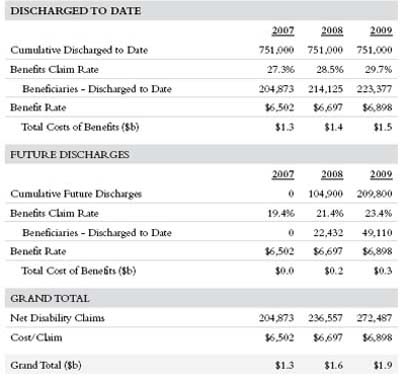

This chapter examines the U.S. government’s capacity to pay disability compensation, provide high-quality medical care, and offer other essential benefits to veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The population of veterans we focus on in this chapter is the 751,000 soldiers who have already served in Iraq and Afghanistan and been discharged. Future cost projections are based on continuing demand from these veterans and projected demand from troops still deployed. (By contrast, chapter 4 examines the total social costs of a small subset of this population—the troops who have sustained serious physical injuries or severe mental illness.)

Most of the sources we employ in our analysis, including the VA’s data, do not differentiate between veterans returning from Iraq or Afghanistan or adjacent locations such as Kuwait. One third of those serving in the Iraq war have been deployed two or more times and many of them have served both in Iraq and Afghanistan, and / or other locations.9 Of course, for the purposes of estimating the long-term cost to the government of caring for veterans, it does not matter where they served. However, the overwhelming majority of the deaths and injuries have been in Iraq—90 percent of those listed as wounded on the Pentagon’s casualty reports.10 We therefore attribute 90 percent of the cost of medical care and disability compensation to the Iraq conflict.

This chapter focuses on the budgetary costs to the United States of providing health care and disability to returning veterans. As the United States continues to place an emphasis on developing the Iraqi military to replace the American presence, it is worth asking what the cost to that country will be of providing medical care and any kind of long-term benefits to Iraqis who are fighting in this war. They will clearly be large—already more than 7,620 Iraqi soldiers have been killed, and many tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers have been wounded (in chapter 6 we address the costs to Iraq and other countries).

Injuries Incurred by U.S. Soldiers in Iraq

AT HOME, WE are witnessing an unprecedented human cost among the veterans who return from Iraq and Afghanistan. More than 263,000 have been treated at veterans’ medical facilities for a variety of conditions. More than 100,000 have been treated for mental health conditions, and 52,000 have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).11 Another 185,000 have sought counseling and readjustment services at walk-in “vet centers.”12 By December 2007, 224,000 returning soldiers had applied for disability benefits. Most of these veterans are providing evidence of multiple health problems. The average claim cites five separate disabling medical conditions (e.g., loss of hearing, skin disease, vision impairment, back pain, and mental health trauma). The least fortunate among our veterans have suffered unimaginable horrors, such as brain trauma, amputations, burns, blindness, and spinal damage. Some have multiple injuries, a condition physicians refer to as “polytrauma.” One in four returning veterans has applied for compensation for more than eight separate disabling conditions.13

Currently, improvised explosive devices, booby-trapped mines, and other types of roadside bombs generate two-thirds of all traumatic combat injuries.14 The blasts create rapid pressure shifts, or blast waves, that can cause direct brain injuries such as concussion, contusion (injury in which the skin is not broken), and cerebral infarcts (areas of tissue that die as a result of a loss of blood supply). The blast waves also can blow fragments of metal or other matter into people’s bodies and heads. Today’s troops wear Kevlar body armor and helmets, which reduce the frequency of penetrating head injuries but do not prevent the “closed” brain injuries produced by blasts. These injuries can result in a diagnosis of “traumatic brain injury” or TBI.

TBI is one of the distinctive injuries of this war, because unlike previous conflicts where the mortality rate from such injuries was 75 percent or higher, the majority of these troops can now be saved.15 Forward surgical teams pack open wounds on the battlefield and the wounded are evacuated to Landstuhl Air Force Base in Germany within twenty-four hours. Veterans who come to VA hospitals for medical treatment say they have been exposed to anywhere from six to twenty-five bomb blasts during their combat experience.

TBI is classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the length of time the patient has lost consciousness and the duration of amnesia following the injury. Moderate and mild patients may suffer symptoms that include cognitive deficits, behavioral problems, dizziness, headache, perforated eardrums, vision and neurological problems. These injuries are different from the kind of concussion or “bruise on the brain” that can heal. Recent studies have shown that TBI inflicted by bombs can lead to permanent damage at the cellular level, even among mild and moderate victims.16 Severe patients can suffer permanent damage that will result in a “persistent vegetative state.” Up to one quarter of soldiers with blast-related injuries die.17

Dr. Gene Bolles, a Vietnam veteran with over thirty years of surgical experience, was chief of neurosurgery at the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany for two years. In a recent interview he had this to say about his experience:

What I saw there…constantly in our intensive care units were these very badly injured young men and women with often only one extremity [left], severe burns, blinded—just severely, severely, injured people. I’ve had soldiers breaking down in tears becoming very emotional as they would tell me some of the things they were seeing and what bothered them. I’ve heard so much of that come from the soldiers it’s taken a while for me to have a good night’s sleep. These were the severest injuries I’ve seen in my career.18

Trapped in Limbo

WHEN OUR SERVICEMEN and women who have suffered mental and physical injuries finally do come home, they face a host of challenges as they try to find timely medical treatment and obtain disability benefits. Returning troops have been caught in a kind of limbo between the Department of Defense, which is responsible for the active duty military (including medical care at military facilities), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which manages medical treatment and disability compensation for service members who have been discharged. The VA is divided into the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), which determines eligibility for, and administers a wide range of, disability-related programs; and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which is responsible for the VA’s hospitals, clinics, and other medical facilities. Despite numerous government studies, task forces, and declarations of intent, the two departments have failed to provide a “seamless” transition for disabled soldiers.

The transition problems entered the public consciousness after the widely reported fiasco at Walter Reed Army Medical Center outpatient facilities, where soldiers awaiting military discharge were kept in squalid conditions. Despite the fact that the hospital was operating at capacity and had experienced an influx of thousands of wounded troops returning from Iraq, the Pentagon had ordered a hold-down on costs and expenses (dubbed “efficiency wedges”) at Walter Reed, because it was slated for eventual closure.19 A nine-member bipartisan commission appointed by Secretary Robert Gates after the conditions came to light issued a blistering report on the situation, saying that the Pentagon had shown “virtually incomprehensible” inattention to maintenance and “an almost palpable disdain” for caring for our veterans.20

The root of the problem at Walter Reed, however, is the awkward, duplicative system by which wounded servicemen and women transition from military to veteran status. Had the patients at the Walter Reed outpatient center transferred into VA facilities, they would have lost all their military benefits and had no income to live on until they could qualify for veterans’ benefits—which could take months or even years. Hundreds of outpatient clinics around the country have veterans trapped in similar circumstances. As Deputy Defense Secretary Gordon England told the Senate Armed Services Committee, “a problem with the transition from DOD to VA is that the disability ratings process is ‘one size fits all,’ the same basic procedures are followed inside the Department and during the transition to the VA for all individuals. The 11% of cases that are those wounded or severely wounded in war are funneled through exactly the same system as the other 89%—the career service members transitioning to retirement.”21

Throughout the process, the burden of securing medical validation and getting the paperwork completed, including a 23-page application, falls primarily to the veteran (unlike systems in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K., where the government effectively accepts the veteran’s claim prima facie). DOD often fails to provide the statistical documentation necessary to move veterans from its payroll and medical care systems into the VA payroll and medical systems. The result is that veterans often need to undergo a second round of medical diagnostic tests in order to qualify for VA disability benefits and medical care.

And many veterans are simply overwhelmed by the volume and complexity of paperwork they need to complete. As Republican congressman Tom Davis III of Virginia put it: “You could put all the wounded soldiers in the Ritz-Carlton and it wouldn’t fix the personnel, management and recordkeeping problems that keep them languishing in outpatient limbo for months while paperwork from 11 disjointed systems gets shuffled and lost.”22

Even some soldiers with serious injuries lose this second battle with the bureaucracy. An e-mail that Linda Bilmes received on February 6, 2007, provides just one example:

Dear Prof. Bilmes,

I saw you on Democracy Now [TV show] on Feb 6, 2007. I have sent many letters and talked to Senate offices. We seem to be getting no where. My Nephew, Patrick Feges, was severely wounded in Iraq, Nov 2004. He had a visit from President Bush at Walter Reed Hospital, Purple Heart from Gov. Perry, but has to this date received NO benefits. He has been working with the VA, but letter after letter does not solve the problems. President Bush can use any numbers describing the wounded or the cost, but nothing is going to solve this problem, if no one is paying attention. Or cares.

Thank you

Kathleen Creasbaum, Patrick’s Aunt

Patrick Feges of Sugarland, Texas, had been walking to the mess hall in Ramadi, in Iraq, when a mortar exploded. The blast severed a major artery and destroyed his stomach. Age nineteen at the time, he was listed in “very critical” condition, treated in four hospitals in three countries over five weeks, and finally received life-saving surgery at Walter Reed. Patrick recovered, although he lost mobility in his ankles and knees, suffered abdominal pain, and could not stand up for long periods. His injuries meant he had to abandon his plan to become a mechanic, but he decided to attend culinary school using the education and compensation benefits he was entitled to receive from the VA. After nineteen months, he still had not received a single penny in benefits and was living at home with his mother, who had taken a second job at night to help support him and his four siblings. (Patrick later received all of his education and retroactive disability compensation, but only after we provided his information to veterans’ advocates Paul Sullivan and Steve Robinson, who intervened with the VA and told Patrick’s story to Newsweek magazine.)23

Despite the media focus on the plight of soldiers like Patrick Feges, a presidential commission, a further commission ordered by Secretary of Defense Gates, and numerous congressional hearings, veterans still face long delays in obtaining disability benefits.

In the remainder of this chapter, we estimate the cost of providing the two primary types of assistance that we provide to our veterans: disability compensation and medical care.

Disability Compensation

THERE ARE 24 million living veterans in America, of whom roughly 3.5 million (and their survivors) receive disability benefits. Overall, in 2005 the United States was paying $34.5 billion in annual disability entitlement pay to veterans from previous wars, including 211,729 from the first Gulf War, 916,220 from Vietnam, 161,512 from Korea, 356,190 from World War II, and 3 from World War I. In addition, the U.S. military pays $1 billion annually in disability retirement benefits.24

Each of the more than 1.6 million troops deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq (and the hundreds of thousands more who are expected to serve before the conflicts are over) are potentially eligible to claim disability compensation from the Veterans Benefits Administration. Disability compensation is money paid to veterans with “service-connected disabilities”—meaning that the disability was the result of an illness, disease, or injury incurred or aggravated while the person was on active military service. Veterans are not required to seek employment nor are any other conditions attached to the program.25

Compensation is granted according to the degree of disability, measured on a scale from 0 percent to 100 percent, in increments of 10 percent.26 Annual benefits range from $1,380 per year for a 10 percent disability rating to about $45,000 for those completely disabled.27 The average benefit is $8,890, although this varies considerably. Vietnam veterans, for instance, average $11,670.28 Veterans who are at least 30 percent “service-connected”29 can qualify for additional benefits such as vocational rehabilitation, housing renovations, transportation, dependent support, home care, and prosthetics. Once deemed eligible, the veteran receives the compensation payment as a mandatory entitlement for life. Should he die, his survivors become eligible for benefits.

There is no time limit on when a veteran can claim disability benefits. The majority of claims are made within the first few years after returning, but many disabilities do not surface until later in life. Veterans are permitted to reopen a claim or file for increases. The VA is still handling hundreds of thousands of new claims from Vietnam-era veterans for post-traumatic stress disorder and cancers linked to Agent Orange exposure.

The process for ascertaining whether a veteran is suffering from a disability, and at what percentage level, is complicated and lengthy. First, the serviceman or woman has to navigate through the disability evaluation process within the military. This begins with a “medical evaluation board” (MEB) assessment, which takes place at a military treatment facility where a doctor identifies a condition that may interfere with a person’s ability to perform his or her duties. If the person is deemed to be unfit for duty, he or she is then referred to a “physical evaluation board” (PEB), which decides if the illness or injury causing the unfitness is linked to military service. Depending on the particular circumstances, a serviceman or woman may then qualify for disability retirement benefits or a lump-sum disability severance payment.30

A veteran must then apply to one of fifty-seven regional offices of the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), where a claims adjudicator evaluates service-connected impairments and assigns a disability rating. The veteran needs to provide evidence of military service records, medical examinations, and treatment from VA, DOD, and private medical facilities. For veterans with multiple disabilities, the adjudicator assigns a composite rating. If a veteran disagrees with the regional office’s decision, he or she can file an appeal to the VA’s Board of Veterans Appeals. Typically, a veteran applies for disability in more than one category, for example, a mental health condition as well as a skin disorder. In such cases, VBA can decide to approve only part of the claim—which often results in an appeal. If the veteran is still dissatisfied, he or she can further appeal it to two even higher levels in the U.S. federal courts.31 One in every eight claims is appealed.

The process for approving claims has been the subject of numerous complaints and Government Accountability Office studies and investigations. Even in 2000, before the war, the GAO identified long-standing problems, including large backlogs of pending claims, lengthy processing times for initial claims, high rates of error in processing claims, and inconsistency across regional offices.32 In a 2005 study, the GAO found that the time to complete a veteran’s claim varied from 99 days at the Salt Lake City office to 237 days in Honolulu.33 In a 2006 study, GAO found that 12 percent of claims were inaccurate.34

The Veterans Benefits Administration has a huge backlog of pending claims, including thousands from the Vietnam era and before. In 2000, the VBA had a backlog of 228,000 pending initial compensation claims, of which 57,000 had been waiting for more than six months.35 At the end of 2007, due in part to the surge in claims from newly injured veterans, the VBA’s backlog was over 400,000 new claims, with 110,000 pending for more than six months.36 The total number of claims, either new or in the process of being adjudicated, exceeds 600,000. The VA has announced that it expects to receive another 1.6 million claims over the next two years.

The VBA now takes an average of six months to process an original claim, and an average of nearly two years to process an appeal.37 By contrast, the private sector health care/financial services industry processes over 25 billion claims a year, with 98 percent processed within sixty days of receiving the claim, including the time required for claims that are disputed.38 Perhaps the most distressing implication of the six-month-long bottleneck in the VA claims process is that it deprives veterans of benefits at the precise moment when—particularly for those in a state of mental distress—they are most at risk of suicide, falling into substance abuse, divorce, losing their job, or becoming homeless.

Some soldiers can use the “Benefits Delivery at Discharge” program to avoid a long spell without benefits. This program allows soldiers to process their claims up to six months prior to discharge, so they can begin receiving benefits as soon as they leave the military. However, the prevalence of extended deployments, the number of second and third deployments, the use of “stop-loss” orders,39 and the resulting unpredictability about when a soldier will be discharged have made it much more difficult to use this program; furthermore, it has not been not available to those in the National Guard.40

The transition from DOD to VA medical facilities is more complicated for seriously wounded veterans. A wounded veteran may receive initial treatment at Walter Reed Army Medical Center before being transferred to a VA facility. The incompatibility between the DOD and the VA paperwork and tracking systems means that these veterans can have a hard time securing the maximum disability benefits at discharge. This tracking and paperwork disconnect not only creates unnecessary problems in moving veterans through the system, but also makes it more difficult to analyze the data on military injuries in medical and other studies.

The Pentagon’s poor accounting system causes yet more problems for veterans. GAO investigators have found that the DOD pursued hundreds of battle-injured soldiers for payment of non-existent military debts. In one instance, an Army Reserve staff sergeant who lost his right leg below the knee was forced to spend eighteen months disputing an erroneously recorded debt of $2,231. This blot on his credit record prevented him from obtaining a mortgage. Another staff sergeant who suffered massive brain damage and PTSD had his pay stopped and utilities turned off when the military erroneously recorded a debt of $12,000 because it neglected to record his separation from the military. In a third case, an Army staff sergeant paralyzed from the waist down received no net pay for the last four months he was in the Army, in payment of a non-existent $15,000 debt. This happened in January 2005; it was not until February 2006 that the sergeant was finally repaid the money. Yet another case stemmed from a soldier who was erroneously listed as absent without leave while she was actually being treated for inoperable shrapnel in her knee. Ironically, these fake debts are often registered because the soldier loses personal equipment (such as body armor and night-vision goggles) after being seriously wounded and evacuated from Iraq. Hundreds of injured soldiers may be in this situation.41

Given the problems that exist now in the system, it is imperative that we consider the demand for benefits that will arise from future veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is difficult to predict the exact number who will claim for some amount of disability, but we know that already 31 percent of the soldiers who have returned have filed claims. We expect that percentage to rise.

The first Gulf War provides a basis for comparison. Certainly, soldiers from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars will qualify for disability based on the same criteria that are used to evaluate first Gulf War veterans.42 Some 45 percent of the veterans of that conflict filed disability claims; 88 percent of their claims were approved at least in part.43 The United States currently pays about $4.3 billion annually in disability payments to veterans of the first Gulf War.44 Some have argued that the claims from that war have been unusually high because those soldiers suffered such high exposure to chemical toxins. But in both Iraq wars, a number of veterans were exposed to depleted uranium used in antitank rounds fired by U.S. M1 tanks and U.S. A-10 attack aircraft. And service members in both Iraq and Afghanistan have been deployed for months on end, involved in severe ground warfare and heavy exposure to urban combat.45 VA psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, winner of a 2007 MacArthur Fellowship for his work among combat veterans, points out that “the mental health toll of the Iraq war is more comparable to Vietnam—except that the soldiers today face a different technological and conceptual environment, and of course the survival rate is much higher.”46

In addition, there is a lag between mental health conditions being diagnosed and the veterans’ ability to file a disability claim for them. To date, the VA has diagnosed 52,000 cases of PTSD, but only 19,000 claims have been filed for it. GAO has reported that it takes one year, on average, for PTSD claims to be filed. It is likely that the number of such claims will grow rapidly from now on. We therefore believe that the number of disability claims from the current conflict is likely to be at least as high as the claims from the first Gulf War, if not higher.

Of the 1.6 million U.S. servicemen and women so far deployed in the Iraq/Afghanistan conflicts, 751,000 had been discharged by December 2007. All are potentially eligible for disability benefits, and by December 2007, 224,000 veterans had applied. Through mid-summer 2007, 90 percent of those applying for disability were approved.47

The estimated costs of providing disability benefits to veterans are immense. To recap, in our conservative scenario, we reached an estimate of $299 billion for disability benefits; in our moderate scenario, the figure was $372 billion. These figures exclude some veterans’ benefits such as private, state, and local health care, disability, and employment benefits for returning veterans. They also exclude the costs associated with veterans’ family members, including compensation and education benefits for surviving spouses and children.

We have assumed in our best case scenario that, on average, compensation will equal that of claimants from the first Gulf War: $6,506. This is a conservative assumption because in the first Gulf War, each veteran claimed for an average of three disabling conditions, whereas this new group of veterans claims for an average of five conditions.48 Furthermore, we already know that the actual rate of serious injuries is much higher than in the first Gulf War.

The realistic-moderate scenario assumes that the average payment per claims is the actual average for new claimants in 2005, which is $7,109.49 This may still be conservative, considering that Vietnam veterans receive an average of over $11,000 and many analysts consider the injuries in this war to be more similar to Vietnam.

Increasing Workload

OF COURSE, THE issue is not simply cost but also efficiency in providing benefits to disabled veterans. The Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans are filing claims of unusually high complexity. To date, the backlog of pending claims from these recent war veterans is 40,000, but the vast majority of servicemen and women have yet to file. That the Veterans Benefits Administration is sympathetic to the plight of disabled veterans should not obscure the fact that the system is already under tremendous strain. If only one fifth of the returning veterans who are eligible claim in a given year, and the total claims reach a rate even comparable to the first Gulf War, the best case scenario for the VA is that the number filing over the next ten years could easily rise to more than 700,000, with almost 75,000 new applicants in a single year (see Table 3.1).50

Table 3.1 Projected Increase in Disability Claims in “Best Case” Scenario

The VBA has more than 9,000 claims specialists, who are required to assist the claimant in obtaining evidence, in accordance with hundreds of arcane regulations, procedures, and guidelines. They must also rate the claims, establish claims files, authorize payments, conduct in-person and telephone interviews, process appeals, and generate various notification documents. They decide the effective date that the veteran is entitled to receive the benefit, since claims are granted retroactively. In other words, these employees play a critical role in whether a veteran can secure his or her benefits.

But currently, the agency faces an enormous staffing problem. According to the VA, new employees need two to three years of experience and training to become fully productive. In May 2007, 40 percent of the claims staff had been employed for less than three years; 20 percent had been there for less than one year.51 Many experienced staffers have been diverted from processing claims in order to train new hires. Moreover, several VBA regional offices still use antiquated IT systems that make it difficult for the specialists to do their job efficiently—forcing them to use unreliable old fax machines to obtain vital documentation from veterans and medical providers.

Proposals to fix this problem that are currently in Congress include funding for 500–1,000 additional administrative staff members to process the claims backlog. But this alone will not reduce the long waiting times that veterans face. At best, a few hundred inexperienced new staffers (assuming they can all be hired quickly) may produce a marginal improvement in claims-processing time, during a period in which the agency faces a huge influx of complex claims. Indeed, it is conceivable that the task of training and integrating a large number of inexperienced people will in the short term actually lengthen processing times, decrease accuracy, and increase the level of appeals. The problem is further compounded by the fact that many experienced VBA personnel will be retiring over the next five years.52

Medical Care for Veterans

THE VA ALSO provides medical care to more than 5 million veterans each year through the Veterans Health Administration. This includes outpatient health care, as well as dental, eye, and mental health care, hospital inpatient and outpatient services at 158 hospitals, 800 community clinics, 136 nursing homes, 209 veterans’ centers, and other facilities nationwide. Medical care is free to all veterans for the first two years after they return from active duty; thereafter, the VA imposes co-payments on certain categories of veterans, with the amounts related to the level of disability and the income of the veteran.53 It is likely that Congress will increase the number of years of free care from two to four or five, a move we strongly support.

The VA has long prided itself on the excellence of care that it offers. In particular, VA hospitals and clinics are known to perform a heroic job in areas like rehabilitation. The medical staff are experienced in working with veterans and provide a sympathetic and supportive environment for the disabled. The VA also plays a major role in educating medical students: 107 of the 126 medical schools in the United States are formally affiliated with a veterans’ hospital, and these hospitals train 20,000 medical students and 30,000 residents each year.54

Given this sterling reputation, the demand for VA medical treatment now far outstrips supply. In 2003, former VA Secretary Anthony Principi announced the decision to ration care based on need and income level. He suspended enrollment of the lowest priority group of veterans (“Priority Group 8”), those who were above a certain income level and not disabled, and increased co-payments and other fees for other groups. This has placed VA health care out of reach for at least 400,000 veterans since then.

Soldiers and other troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan now face long waiting lists—especially in certain specialties—and in some cases simply absence of care. To date, 35 percent of the 751,000 eligible discharged veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan have sought treatment at VA health facilities. This figure comprises less than 5 percent of the total patient visits, but it will grow. According to the VA, “As in other cohorts of military veterans, the percentage of [Iraq and Afghanistan] veterans receiving medical care from the VA and the percentage of veterans with any type of diagnosis will tend to increase over time as these veterans continue to enroll for VA health care and to develop new health problems.”55

The war in Iraq has been noteworthy for the types of physical injuries sustained, especially traumatic brain injuries, but the largest unmet demand is in mental health care.56 The strain of extended deployments, the stop-loss policy, stressful ground warfare, and the uncertainty surrounding discharge and leave have all taken their toll. Some 38 percent of the veterans treated so far—an unprecedented number—have been diagnosed with a mental health condition. These include post-traumatic stress disorder, acute depression, and substance abuse. According to Paul Sullivan, “The signature wounds from the current wars will be (1) traumatic brain injury, (2) posttraumatic stress disorder, (3) amputations and (4) spinal cord injuries, and PTSD will be the most controversial and most expensive.”57

Mental health disorders are extremely costly, both because they require long-term treatment and because those who suffer from them have a greater tendency to develop physical medical problems. Long-term studies of Vietnam veterans have also shown that PTSD leads to worse physical health throughout a veteran’s life.58 According to the Veterans Disability Benefits Commission, PTSD sufferers had the worst overall health scores in the veteran population, and one in three veterans diagnosed with PTSD was permanently incapable of working, classified as “individually unemployable.” The National Institute of Medicine found that while PTSD accounts for 8.7 percent of total disability claims, it represents 20.5 percent of compensation benefit payments.59

PTSD is highly prevalent as a result of multiple rotations into combat, the widespread use of IEDs, and the absence of a defined “front line” in battle. Troops who have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan also talk about the moral ambiguity of seeing combatants dressed as civilians, of not knowing who is friend or foe. Studies have found a strong correlation between the length of time a soldier serves in a war zone and the likelihood of developing PTSD.60 For this reason, we can expect that servicemen and women on their second and third deployment are at high risk. Most of those serving second and third deployments have not yet returned. Moreover, psychiatrists point out that a good many PTSD symptoms—confusion; vertigo; being easily startled; numbness; difficulty in sleeping, concentrating, and communicating—can also be symptoms of traumatic brain injury, and so there is some difficulty and overlap in the diagnoses.

Compared to veterans of earlier conflicts, Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans are far more likely to seek help for mental health distress, in part because of awareness campaigns run by veterans’ organizations and an outreach campaign conducted by the VA itself. There is no reliable data on the length of waiting lists for returning veterans, but even the VA concedes that they are so long as to have the effect of denying treatment to a number of mental health patients. In Psychiatric News for May 2006, Frances Murphy, M.D., then Under Secretary for Health Policy Coordination at the VA, stated that mental health and substance abuse care are simply not accessible at some VA facilities. When the services are available, Dr. Murphy added that in some locations “waiting lists render that care virtually inaccessible.”61

Veterans’ groups have filed a national class action lawsuit against the Department of Veterans Affairs on behalf of veterans and their families seeking or receiving death benefits or disability compensation for PTSD. The plaintiffs estimate that the class includes between 320,000 and 800,000 veterans, a figure they arrive at by multiplying the number of troops deployed by their estimated incidence of PTSD (20–50 percent). The plaintiffs are not seeking financial compensation; rather, they want the VA to acknowledge a number of policy failures. “This isn’t a case about isolated problems or the type of normal delays and administrative hassles we all occasionally experience with bureaucracies,” says Gordon P. Erspamer, the lawyer representing the veterans on a pro bono basis. “This case is founded on the virtual meltdown of the VA’s capacity to care for men and women who served their country bravely and honorably, were severely injured, and are now being treated like second-class citizens. The delays caused by the VA have created impenetrable barriers to relief for thousands of impaired veterans.”62

The administration has followed the same pattern of underfunding for veterans returning from the war that it has followed in financing the war itself. In fiscal year 2006, the VA had to request $2 billion in emergency funding, which included $677 million to cover an unexpected 2 percent increase in the number of patients (half of whom were Iraq and Afghanistan veterans); $600 million to correct its inaccurate estimate of long-term care costs; and $400 million to cover an unexpected 1.2 percent increase in the costs per patient due to medical inflation. In the previous fiscal year, the VA requested an additional $1 billion in emergency funding, of which one quarter was for unexpected needs related to the current conflict and the remainder was to cover an overall underestimation of patient costs, workload, waiting lists, and dependent care.63 The pattern of underfunding noted in 2005, where needs were projected on the basis of data from 2002, before the war in Iraq began, has repeated itself every year of the war. The VA has told Congress that it can cope with the surge in demand, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.64 For FY 2008, the Congress is demanding an additional $3 billion in emergency funding (above the president’s request) for the VA health care system to cope with the rising demand.

As the demand for medical care increases, the already overwhelmed Department of Veterans Affairs may be unable to meet it, particularly in rural areas where the organization has found it difficult to recruit medical staff. Brain trauma units and mental health facilities are experiencing staff shortages, and the VA also needs to expand systems such as triage nursing to help maximize the effective use of scarce medical resources. The quality of medical care is likely to continue to be high for those veterans treated in the new polytrauma centers, but the current state of service means that not all facilities can offer such high quality in a timely fashion.

The budget shortfalls and the testimony of experts like Dr. Murphy suggest that veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, particularly those with mental health conditions, may not be able to obtain the health care they need. These veterans are at high risk of unemployment, homelessness, family violence, crime, alcoholism, and drug abuse, all of which impose an additional human and financial burden on the nation. When the VA does not provide these services, costs are shifted to others; local and state governments provide many of the social services that veterans require, but some are already under tremendous strain and may not be able to cope.

As we discussed in chapter 2, in our best case scenario, we have estimated that the annual cost of providing care to the 48 percent of current veterans who will eventually seek treatment from the VA is $3,500, based on reports that the current cost to the VA of treating veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars is about this amount.65 However, this is almost certainly too low, because the current average bill includes initial visits required to validate a condition (that a veteran needs just to qualify for disability compensation). The cost of those visits is much lower than the cost of treatment. To recap from chapter 2: this scenario assumes that 1.8 million U.S. troops are eventually deployed, and that troop levels fall to 55,000 non-combat soldiers in 2012. Injury rates and other costs are reduced by 50 percent from this point onward. Under this set of assumptions, the U.S. government will pay out $121 billion for veterans’ health care, $277 billion in veterans’ disability benefits, and $25 billion in Social Security disability compensation over the course of their lives. The total long-term costs to the federal government will therefore be $422 billion.

In the realistic-moderate scenario, we use the current average annual cost to the VA of treating all veterans in the system, which is $5,765.66 This scenario assumes that the conflict involves a total of 2.1 million servicemen and women and an active U.S. military presence in the region through 2017. Assuming that the rate of death and injuries per soldier continues at current rates, we estimate that 50 percent of those who enroll in the VA health care (one quarter of all disabled veterans) will continue to use the VA as their lifetime health care provider. Under this set of assumptions, the cost of providing lifetime medical costs to veterans will be $285 billion, $388 in disability benefits, and $44 billion in Social Security compensation, bringing the total long-term cost to the U.S. government to $717 billion.

We have already emphasized that the VA is not the only part of the federal government that will face incremental costs as a result of the injuries and disabilities stemming from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. For instance, many of the injured will be unable to get jobs providing family health care benefits; Medicaid will pick up at least part of the tab. The single, largest number that can easily be quantified is Social Security disability benefits. The combined cost of health care, VA disability, and Social Security disability for our moderate scenario comes to nearly three quarters of a trillion dollars; in the best case scenario, it is still almost half a trillion dollars.

Table 3.2. Total Medical, Disability, and Social Security Disability Costs for Veterans

| Veterans’ Cost (in U.S. $billions) | Best Case | Realistic-Moderate |

| Iraq Medical | 106.4 | 250.1 |

| Iraq Disability | 242.9 | 341.2 |

| Iraq Social Security | 21.7 | 38.4 |

| Iraq Total | 371 | 629.7 |

| Afghanistan/Medical | 14.7 | 34.7 |

| Afghanistan/Disability | 33.7 | 47.3 |

| Afghanistan/Social Security | 3.0 | 5.3 |

| Afghanistan/Total | 51.4 | 87.3 |

| TOTAL COSTS | 422 | 717 |

We should reemphasize that these scenarios are very conservative in several of their key assumptions, for instance, in assuming that only half the returning veterans will eventually seek any medical treatment at all from the VA. Many returning veterans do not have any alternative source of health care, and until this country provides a system of universal care, the VA system will be the only available option. We have also made a leap of faith in assuming that the VA can hire the additional medical personnel required to provide the requisite health care without raising salaries.

We have seen how returning veterans now face a bureaucratic nightmare, including long backlogs in processing claims. But we have also seen that much larger demands will almost surely be imposed on the system. Without a major overhaul of the current system, veterans are virtually guaranteed bigger claims backlogs, longer waiting lists, and a possible diminished quality of medical care. The hundreds of thousands of new veterans who seek medical care and disability compensation in the next few years will overwhelm the system in terms of scheduling, diagnostic testing, claims evaluation, and access to specialists in such areas as traumatic brain injury. Veterans with mental health conditions are most likely to be at risk because of the lack of manpower and the inability of those scheduling appointments to distinguish between higher-and lower-risk conditions.

Nor have we included the cost of increased administrative and medical staff that will be needed to meet the huge demand. There is a tendency in some circles to view such civil servants as part of a bloated bureaucracy. But no agency, public or private, can administer programs of the size we are discussing without incurring substantial administrative costs. The necessary expansion of the VA staff to handle these obligations—between a half and three quarters of a trillion dollars—will themselves reach into the billions, perhaps tens of billions of dollars. Such “overhead” or “transactions” costs typically exceed 10 percent or more of the benefits disbursed, even in well-run private programs—suggesting that the requisite incremental administrative spending may indeed by substantial.67

The budgetary costs on which we have focused here are only part of the overall costs of war. Just as there has been no preparation for delivering the promised benefits to our veterans, there has also been no preparation for paying the cost of another major entitlement program. Formally, the VA’s disability benefits are a “mandatory” benefit—they are not subject to the annual appropriations process. Such expenditures are traditionally labeled as “entitlements.” By contrast, the VA’s medical budget is discretionary, that is, lawmakers appropriate funds on an annual basis. But the country has a moral obligation to provide returning veterans with the medical benefits that have been promised, and it is hard to conceive of the nation walking away from such a commitment. In our analysis, we have projected costs and assumed that Congress will provide the requisite funding. (There are slight differences in our estimates of these medical costs over the period 2007–17 and that of the CBO [in our best case scenario, our estimate is $16.6 billion; that of the CBO is $7–$9 billion]. The major difference lies in the large lifetime costs—going well beyond the next ten years—which CBO’s methodology ignores.)

In any of the scenarios, the funding needs for veterans’ benefits comprise an additional major entitlement program along with Medicare and Social Security. President Bush has frequently spoken out about the funding gap for Social Security. The magnitude of that gap depends on assumptions about wage growth, migration, and life expectancy; but in most scenarios, the consequences of the funding gap are not imminent. By contrast, the Iraq war has created, since 2003, a new, large, and growing entitlement funding gap.

This additional entitlement for veterans’ medical care will place additional strain on the discretionary budget—which is the source of funding for the veterans’ medical system. History suggests that after a war, the public often loses interest in taking care of its veterans. Veterans are likely to lose out again unless we can secure the monies for taking care of them in trust funds.

Veteran’s disability benefits and medical care are two of the most significant long-term costs of the Iraq war. The war—in all of its dimensions—has budgetary costs, but it also has broad social and economic costs. This is especially true of the human toll, which has been borne by our troops. This chapter has focused exclusively on the budgetary costs of caring for veterans. It does not take into account the value of lives lost or decimated by grievous injury. Nor does it take into account the economic impact of the large number of veterans living with disabilities who cannot engage in full economic activities. These economic and social costs may be far greater than the budgetary costs faced by the federal government; they are the subject of the next chapter.