Promoting health and vigor

Promoting health and vigorEver wrecked a tree or shrub by pruning it? The pruning fundamentals in this book can keep you from repeating the mistake. Knowing the basics boosts the beauty of your garden and helps your plants survive and thrive. Here are some of pruning’s many benefits:

Showcasing beautiful bark

Showcasing beautiful bark

Increasing flowering

Increasing flowering

Increasing yields from fruit trees and berry bushes

Increasing yields from fruit trees and berry bushes

Controlling size

Controlling size

Guiding growth

Guiding growth

Managing a view

Managing a view

Mending damage

Mending damage

Eliminating hazards

Eliminating hazards

Pruning helps keeps woody plants healthy. Proper pruning can also enhance the natural pattern of growth of a shrub or tree, improve flowering and fruit set, and control its size. Sometimes you can prune out growth as preventative medicine or to eliminate a disease. Young or old trees and bushes may have problems that pruning can solve.

Q I have some tree and shrub plantings that grew well for a while, but now they don’t look as good. Can pruning get them growing again?

A If a shrub or tree is beginning to show symptoms of age but is not quite ready to retire, pruning can restore vitality. Although you may be tempted to chop back every old plant to stimulate new growth, this doesn’t always work. It is risky on large old shade trees. Broadleaf evergreens and conifers are also unlikely to benefit from severe beheading. Even if young and vigorous, a drastic slashing of a spruce or pine tree can prove fatal.

Yet some plants respond well to drastic, carefully considered techniques. In some regions of the country, certain roses (even old ones) may flower best only if you cut them back nearly to the ground each spring. And clematis, shrubby cinquefoil, hydrangea, lilac, and honeysuckle all seem to benefit from occasional drastic pruning. A young, forked tree can often be shaped into a strong, straight specimen by cutting off one of the forks and staking the other. In time, the crook in the stem will straighten.

Most berry-producing ornamentals, on the other hand, such as cotoneaster and viburnum, need little or no pruning. Older trees and bushes prefer rejuvenation by light and frequent pruning.

SEE ALSO: Pages 100–101 for renewing old shrubs.

Q I’m confused about what I should remove to keep my plants strong. Can you give me some basic guidelines for pruning my trees and shrubs?

A In general, regular pruning that begins early in a plant’s life is less of a shock to the plant and also always looks better than a full-scale attack with shears and saw. For instance, orchardists renew the bearing wood on their fruit trees gradually by removing some older branches each year. This method is also best for bush fruits such as blueberries and gooseberries. The bearing is uninterrupted, regrowth is moderate, and the bush or tree suffers no serious setbacks. The same is true for ornamentals.

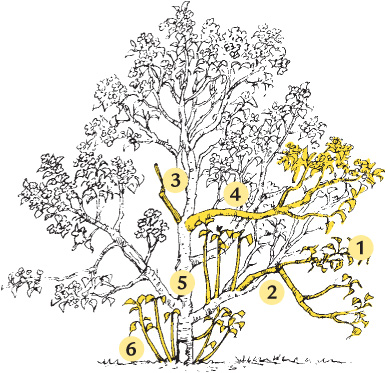

To maintain healthy plants, remove (1) diseased growth, (2) branches too close to ground, (3) dead branches, (4) crossing and rubbing branches, (5) water sprouts, and (6) suckers.

Q What steps should I take to prune for a healthier tree?

A If you see that a plant is struggling, step in to help.

1. Get rid of obvious problems first. Unlike injured animals that heal and repair, wounded trees wall off damage and grow parts in new places. To promote tree health, prune dead or damaged branches to just outside the branch collar (see page 62) on the trunk or on a main limb.

2. Eliminate stems, twigs, and branches that are diseased or infested with borers, scales, and other insects. Burn debris or bury deeply so the problem won’t spread.

3. Remove suckers, or little trees, sprouting from the trunk or the roots. These deplete a tree’s energy. If you allow them to grow, they will spoil your tree’s appearance and turn it into a large bush. Unchecked suckers growing from the wild rootstock of a grafted fruit, shade tree, or rosebush can crowd out the desirable part of the plant.

4. Bark damage occurs when the branches of trees, especially deciduous ones, rub against buildings or other branches. To remedy, snip off offending limbs at a side branch or at the branch collar as soon as you see them. If you do nothing, branches may suffer bark damage, which invites infection and can lead to tree loss.

5. Remove water sprouts (branches growing straight up, often from old pruning scars) as soon as they form. These branches weaken a tree and cause ugly growth that is difficult to deal with later.

6. Deal with like-size adjoining trunks with bark squeezed in the crotch between them by removing one of the trunks. A weak crotch can mean a cracked or broken trunk later on in the tree’s life.

7. Prune fruit trees for increased air circulation and sunlight. Too-warm or too-cool temperatures and high humidity may lead to problems. You can prevent these by removing superfluous branches to admit moving air and light into the tree’s interior.

Q I just moved from Boston to Miami. Will that change the way I prune?

A Gardeners in warmer parts of the country and in tropical and semitropical climates can do more severe pruning than those in cooler areas (except on conifers). Fast regrowth almost always follows a major pruning job in warm climates, while in the North, the soft, new growth may not completely harden before autumn frosts begin. Winter injury results, and a tree, already weakened by abnormal pruning and regrowth, may be damaged permanently or killed outright.

Q How do I know if my trees and shrubs need to be pruned?

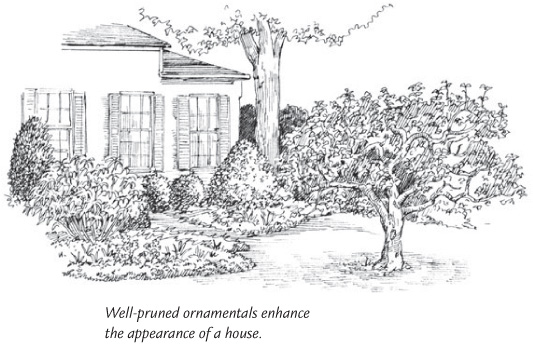

A Pruning is both art and science. Maintaining an appealing landscape in proportion to your house is as important as keeping your plants healthy and strong. That’s where directing plant growth through smart pruning comes in.

New plants grow so slowly that they usually need little pruning the first few years. Suddenly, though, they begin to grow rapidly, and soon they become too large. Ask yourself:

Are the proportions right?

Are the proportions right?

Do the shapes complement each other?

Do the shapes complement each other?

Some landscapers like their work to look finished the day they put in the plants. To accomplish this they use more and bigger plants than necessary, meaning that after a few years, everything is crowded. When this occurs, remove the extras instead of cutting them back.

Pruning for appearance involves much more than just controlling plant size. It also means keeping evergreens and flowering shrubs well proportioned, removing sucker growth from the bottoms of trees, and taking off limbs or blooms that detract from a plant’s appearance. Prune in relation to the rest of the planting, the house, other buildings, walks, and walls. Keep your plantings attractive but not so showy that they hide or detract from your home. The landscape should look nice from both inside and outside the house.

Q My evergreens have grown so tall that they block my view of a neighboring pond. I don’t want to cut them down, so what can I do?

A Gardeners prune for many reasons, from improving the health and productivity of plantings to manipulating an entire view. Create sight lines by limbing up particular trees, thus opening distant views for your pleasure. Conversely, you can block ugliness from sight with a dense evergreen screen.

SEE ALSO: Limbing Up, page 64.

Q What mistakes can pruning help correct?

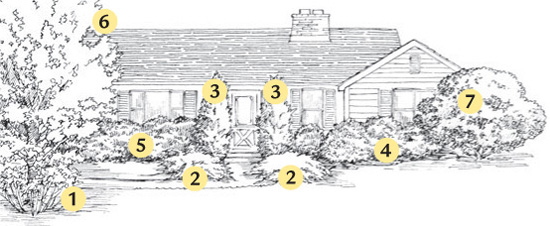

A Among these problems are (1) improper placement of shrubs, (2) spreading evergreens that crowd a path, (3) doorway plantings that have grown too large, (4) foundation plants that crowd each other, (5) foundation plantings that hide windows, (6) a shade tree in front of and too close to the house, and (7) flowering shrubs that hide rather than frame the house.

Q Is there a rule of thumb for training and shaping trees and shrubs?

A Let nature guide you, and prune to enhance your plant’s natural form. To avoid making major pruning mistakes when training a young tree, study its mature shape in a picture, a neighbor’s yard, or a public garden.

Let trees that grow in a pyramidal or columnar form keep their lower branches. Spreading and rounded trees look better and are more useful as shade trees if you remove their bottom limbs. Prevent limbs of weeping deciduous trees from flopping on the ground.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Some horticultural names give you a clue about a plant’s growth habit. When you see ‘Fastigiata’, ‘Columnare’, or ‘Erecta’, you can be sure the tree will take on an erect, upright form. ‘Pyramidalis’ indicates a cone shape. ‘Globosa’, like globe, naturally indicates a round shape. ‘Nana’ means dwarf, and ‘Pendula’ refers to a hanging or weeping growth habit.

Q Can pruning change the long, thin shape of a dog-wood that I planted under some oak trees?

A Thinning the oaks’ canopies to let more light reach the dogwood might help. Light conditions and growing space affect a tree’s mature form. Trees grown in full sun and open space are fuller with more branches, leaves, flowers, and fruits than their shaded counterparts because sunlight is the main source of a tree’s food and energy. Shaded trees have less exposure to sunlight, thus fewer leaves to manufacture food. Trees growing in crowded conditions tend to shade each other out. Growth tends to be narrow and stretched upward toward the sun. Find out whether your trees and shrubs need full sun or if they will tolerate some shade.

Q Do I need to prune my ornamental crab apple?

A It depends. If your goal is a tree with a full, handsome crown, you may need to do very little to keep it looking great. Prune sparingly, removing only damaged or weak wood, branches that are crossing or rubbing others, and the occasional branch that shoots off in an odd direction. Many varieties become beautiful specimens with very little intervention. If enjoying flowers is your primary goal, prune right after the flowers fade.

SEE ALSO: Flowering Trees, page 94.

Good pruning respects a tree’s natural shape, including the distinctive shapes of the trees listed here. Do you recognize your tree’s shape below?

Columnar

Columnar European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus ‘Columnaris’)

Columnar sugar maple (Acer saccharum ‘Newton Sentry’)

Dawyck European beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Dawyckii’)

Fastigiate Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra ‘Fastigiata’)

Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra ‘Italica’)

Pyramid arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis ‘Pyramidalis’)

Sky Pencil Japanese holly (Ilex crenata ‘Sky Pencil’)

Skyrocket juniper (Juniperus scopulorum ‘Skyrocket’)

Some colonnade-style apples (Malus ‘Scarlet Sentinel’,

M. ‘Golden Sentinel’, M. ‘Maypole’, M. ‘Northpole’,

M. ‘Crimson Spire’, M. ‘Emerald Spire’, M. ‘Scarlet Spire’, M. ‘Ultra Spire’)

Upright English oak (Quercus robur ‘Fastigiata’)

Upright European beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Fastigiata’)

Upright mountain ash (Sorbus aucuparia ‘Fastigiata’)

Upright white pine (Pinus strobus ‘Fastigiata’)

Pyramidal

Alder (Alnus spp.)

American arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis)

American holly (Ilex opaca)

Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum)

Black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), when young

Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)

English holly (Ilex aquifolium)

Larch (Larix spp.)

Spruce (Picea spp.)

Sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana)

True cedar (Cedrus spp.)

Turkish filbert (Corylus colurna)

Upright yew (Taxus cuspidata)

Rounded

Cornelian cherry dogwood (Cornus mas)

European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus)

Fox Valley river birch (Betula nigra ‘Little King’)

Japanese hemlock (Tsuga diversifolia)

Japanese maple (Acer palmatum)

Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa)

Red buckeye (Aesculus pavia)

Round-leafed European beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Rotundifolia’)

Sargent crab apple (Malus sargentii)

Umbrella catalpa (Catalpa bignonioides ‘Nana’)

Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense)

Basswood (Tilia americana)

European beech (Fagus sylvatica)

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) with age

Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis)

Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum) with age

Live oak (Quercus virginiana)

London plane tree (Platanus × acerifolia)

Saucer magnolia (Magnolia × soulangiana)

Sweet birch (Betula lenta) with age

White oak (Quercus alba)

Golden weeping willow (Salix × sepulcralis ‘Chrysocoma’)

Weeping Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis ‘Pendula’)

Weeping European beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Pendula’)

Weeping Higan cherry (Prunus subhirtella ‘Pendula’)

Weeping katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum ‘Pendulum’)

Weeping larch (Larix decidua ‘Pendula’)

Weeping Norway spruce (Picea abies ‘Pendula’)

Weeping white pine (Pinus strobus ‘Pendula’)

Weeping willow (Salix babylonica)

Vase-Shaped

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) when young

Japanese zelkova (Zelkova serrulata)

Kwanzan flowering cherry (Prunus ‘Kwanzan’)

Paperbark maple (Acer griseum) with age

Valley Forge American elm (Ulmus americana ‘Valley Forge’), a cultivar resistant to Dutch elm disease weeping vase

Q My river birch clump has gorgeous peeling bark, but you can’t see it when the tree’s in leaf. How can I show off the texture of the bark?

A Try cutting off limbs at the base of the tree (known as limbing up or basal pruning, page 64). In addition to showing off the bark, removing lower limbs opens up living or planting space under large trees, frames views, and lets light into dark spots.

TREES WITH COLORFUL OR STRIKING BARK

These handsome trees are good candidates for limbing up.

Lacebark elm (Ulmus parvifolia)

Lacebark pine (Pinus bungeana)

London plane tree (Platanus × hispanica)

Madrone (Arbutus menziesii)

Paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

River birch (Betula nigra)

Snakebark maple (Acer capillipes)

Stewartia (Stewartia spp.)

Q Will pruning help my camellia to produce larger flowers?

A If you remove some of the buds, you’ll get fewer blooms but each one will be larger. This technique is called disbudding. Camellias are frequently disbudded in late August and September to increase flower size and quality. To accomplish this, leave one bud per terminal, though this may differ according to the age, size, and type of camellia you’re disbudding.

SEE ALSO: Page 116 for disbudding roses.

Q Do I prune my ‘Liberty’ apple tree the same as my ornamental crab apple?

A Yes and no. With either tree, you’ll want to remove dead and damaged wood. Prune your apple — and other trees grown primarily for edible fruits — to ensure a plentiful harvest. Take off a couple old limbs each year. That way, you can renew the fruit-bearing branches in six to eight years. Remove water sprouts, those upright, vigorous-growing branches that cause unwanted shade and are usually unproductive. Also remove the extra fruits when your tree sets too many. Thinning fruits makes the remaining ones grow bigger and better.

SEE ALSO: Pruning Fruit Trees, pages 213–266.

Q Help! My trees and shrubs are overwhelming the house. Can pruning help me control their size?

A A good planting connects the house to the land, provides an attractive setting, and gives the yard a finished look. Although it’s always best to grow trees and shrubs that mature to a suitable size, pruning helps keep too-big plants in check. For example, hemlock or arborvitae trees that might otherwise grow 40 to 80 feet tall can be maintained as a much shorter hedge by regular shearing. Pruning may be necessary for large trees and bushes that crowd power lines, driveways, sidewalks, or buildings.

Q Are there ways to control size without pruning?

A Yes! Consider these alternatives to pruning to reduce the time and cost of maintenance:

Read labels and buy plants that mature to the desired size for a particular location. Consider varieties of fruits, evergreens, and shrubs that are labeled dwarf. Even these may require some control or they’ll eventually outgrow their space.

Read labels and buy plants that mature to the desired size for a particular location. Consider varieties of fruits, evergreens, and shrubs that are labeled dwarf. Even these may require some control or they’ll eventually outgrow their space.

Plant fruits or ornamentals in large tubs placed on a patio, deck, or terrace. Confining the roots helps limit plant size, so you won’t have to prune as much.

Plant fruits or ornamentals in large tubs placed on a patio, deck, or terrace. Confining the roots helps limit plant size, so you won’t have to prune as much.

Q I planted a climbing hydrangea near a tree, a few feet from the trunk where I want it to grow. How do I get the vine off the ground and up the tree?

A Guiding plant growth takes some pruning and patience. For your climbing hydrangea (H. anomala subsp. petiolaris), take some long stems and tie them loosely to the tree with string. You may have to do this in more than one place on the trunk, depending on the length of the stems you’re attaching. Remove the twine once the rootlets begin to attach themselves to the trunk. Climbing hydrangea also makes a lovely mounding ground cover. To control its spread, cut back wayward stems when dormant.

Q Can early training increase the life span of a tree?

A You can sometimes prevent injury by pruning for a strong structure early in a tree’s life. This task is especially important if you want to grow brittle-wooded trees such as willows and silver maples. Strong limbs usually connect to trunks at angles greater than 45 degrees and less than 90 degrees and have no included bark (bark wedged inside where the branch attaches). If your tree has included bark, narrow crotches can promote limb failure. When your tree is young, you can remove branches with skinny V-crotches or use spreaders to widen them.

SEE ALSO: Training Shade Trees, page 80.

Q Last winter an ice storm tore some limbs off a willow. Do we have to take it out?

A If the trunk and most limbs survived, then try to improve the tree’s looks with pruning. Prune off broken limbs at the branch collar soon after the injury occurs. Jagged stubs give disease-causing pathogens easy access to a tree. Disease weakens a tree and makes it susceptible to pest infestations, which may lead to even more problems. You may have to wait a few years until the tree recovers some vitality to reshape it. Do that during dormancy, and never remove more than 25 percent of the canopy in any one year (10 to 15 percent is better).

Q We installed creeping junipers in our front-entry beds. Now the branches cover more than half the front path. What should I do?

A Safety first; you don’t want to hurt yourself or your visitors! Cut back the junipers so family and friends can walk unobstructed on the path. If you don’t want to keep up with the pruning, consider moving them to a larger space and replacing them with a less vigorous ground cover.

Pruning for safety is also necessary around power lines, windows, doors, and wherever damaged limbs or trunks endanger the well-being of people and your home. Never prune around electrical or utility lines yourself; contact your utility or municipality or hire a qualified arborist.

Q How can I reduce the chance of a tree falling on my house?

A Some fast-growing, brittle trees such as silver maple (Acer saccharinum) and tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) have thick crowns that develop a sail-like wind resistance, making them poor candidates for surviving high winds intact. You can improve the odds for these and similar trees by removing limbs with narrow crotch angles and selectively thinning the crown to reduce wind resistance.