Do radical pruning only when vines are dormant. That’s true even for vines with the rankest growth that can withstand the hardest cutback.

Do radical pruning only when vines are dormant. That’s true even for vines with the rankest growth that can withstand the hardest cutback.Vines and ground covers are useful additions to home landscaping. Some plants can be used for both purposes: vining ivies, woodbine, and honeysuckle, for instance, also make useful ground covers. You can keep most of them looking good and under control with minimal care. The care and pruning of each is similar.

Vines do not grow quickly to just the right height and then stop growing and look nice forever after. Nor does a ground cover exist that will spread over a lawn within a few weeks, stay neat, and stop growing at the edge of flower beds, without ranging into the vegetable garden or the neighbor’s putting green.

Some vines, such as wisteria and climbing hydrangea, are hardy, woody plants. A few vines have roots that are hardy and tops that are not. Tender vines, such as star jasmine, often grow this way in the North but are entirely perennial in the South. Some, such as grape, develop large trunks when very old; others, like ivy, have thin, wiry stems and can trail over brick walls. Some small, woody bushes such as creeping junipers and prostrate rosemary make good ground covers.

Q What are some different ways that I can use vines in my landscape?

A Vines as blinds. Some people grow vines to disguise a rainspout, telephone pole, or other unsightly object. Twining vines such as variegated kiwi, star jasmine, and wisteria are ideal for this purpose because they are vigorous growers. Just remember to keep the vine well groomed and to prune it to keep it within bounds. Otherwise, the cover itself can become unattractive, defeating the purpose of improving the site’s appearance.

Vines as hedges. In areas where a hedge would take up too much valuable space, vines make a good substitute. Install a woven-wire fence with well-spaced and well-braced posts and plant tight-growing vines along its length. In a few years, you’ll have an effective barrier. Shear occasionally to keep the plants confined to the fence.

Q Do vines with edible fruits need special pruning?

A You must prune more precisely when your vines are growing food, and give them proper growing conditions. Most food plants, including grapes (Vitis spp.), dew-berries (Rubus spp.), and kiwis (Actinidia spp.), need plenty of sun, so never allow the vines to become thick and overgrown. Because grapes and berries produce best only on year-old wood, you should cut away all wood older than that every year if food is your primary interest.

SEE ALSO: Pruning Bush Fruits, Brambles, and Grapes, pages 267–294.

Q It seems as if most woody plants need some early training. Is that also true of woody vines?

A Some early pinching and snipping adds considerably to the general appearance of most vines. Form a mental image of how you want yours to look in its prime, then prune it that way. For example, wisteria is an attractive flowering vine, but it can also be pruned into an equally beautiful shrub or small tree.

Q When’s the best time to prune vines?

A When in doubt, prune woody vines when they are dormant. Clip off stray shoots and dead or diseased wood in any season.

Q I just planted a passionflower vine. Do I need to prune it?

A Potted vines need little to no pruning when you plant them, unless you need to trim a broken stem. If you’re planting a bare-root, woody vine — that is, one with a hard, woody stem — you should cut the top back by about 25 percent, to a bud, on planting day. This early pruning will promote branching while slowing top growth until new roots can supply enough energy to support the growth, resulting in a more vigorous vine. Of course, carefully follow all the other proper planting procedures regarding location, planting depth, watering, fertilizer, and soil.

Q My sweet autumn clematis grows like crazy and needs cutting back. When’s the best time to prune it?

A The time varies according to what you’re doing. Follow these tips:

Do radical pruning only when vines are dormant. That’s true even for vines with the rankest growth that can withstand the hardest cutback.

Do radical pruning only when vines are dormant. That’s true even for vines with the rankest growth that can withstand the hardest cutback.

Trim during the growing season. After the vine has reached the height and width you want, most of your pruning will consist of snipping back any growth that goes beyond those limits. Specifically, shape spring bloomers right after flowering and late-season bloomers when dormant, in late winter or early spring.

Trim during the growing season. After the vine has reached the height and width you want, most of your pruning will consist of snipping back any growth that goes beyond those limits. Specifically, shape spring bloomers right after flowering and late-season bloomers when dormant, in late winter or early spring.

Promptly remove dead and damaged wood. Occasionally thin out some old wood to keep the vine from choking itself. Also, prune out any part of the vine that has been hurt by winter damage, been eaten by insects, or shows signs of disease. Don’t neglect this chore, or eventually you will be faced with a major, tedious job.

Promptly remove dead and damaged wood. Occasionally thin out some old wood to keep the vine from choking itself. Also, prune out any part of the vine that has been hurt by winter damage, been eaten by insects, or shows signs of disease. Don’t neglect this chore, or eventually you will be faced with a major, tedious job.

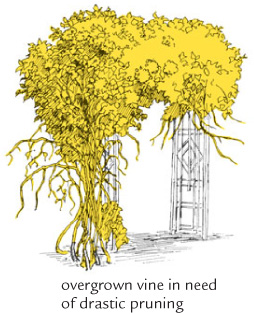

Q How do I rejuvenate an overgrown vine?

A Radical pruning is justified when a vine has gotten completely out of control, grown way beyond its bounds; no longer looks healthy and attractive — and the prospect of going in and removing all the deadwood is over whelming.

1. Cut back the whole plant but leave a few young stalks (year-old spurs are best), if there are any, growing near the main stem. Most vines are extremely resilient and will bounce right back.

2. When the vine begins to send up new shoots, clip off most of them, leaving only three or four of the most vigorous. These will grow rapidly, and soon you will have a full-sized, healthy new vine.

Q When should I renew an overgrown wintercreeper?

A The best time is very early in the spring, while the vine is still dormant, so regrowth can start soon after.

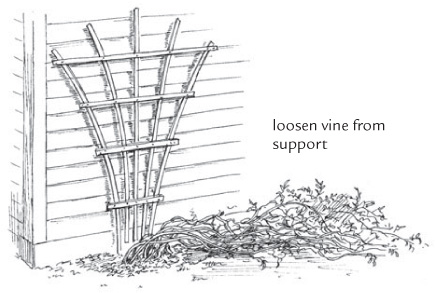

Q We want to paint our house, which has a trellised magnolia vine growing up on one side. Can we cut the vine to the ground to get it out of the way?

A No. If you want to save the plant, plan your project for early spring or late fall, when the pruning will be least harmful. If you must do the job in midsummer, keep the cutting to the barest minimum to prevent a lot of late-summer regrowth.

1. Unless the vine is very stiff and brittle, cut off just enough to loosen it from its support and lay it down carefully on the ground.

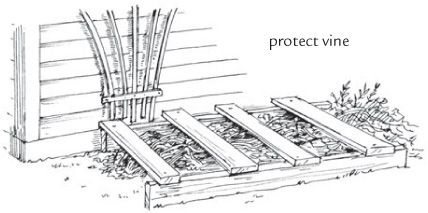

2. Protect the vine while you work, and don’t pile any materials on it. Put a corral of boards or bricks around it, or lay a tarp loosely over it — anything that prevents you from trampling it.

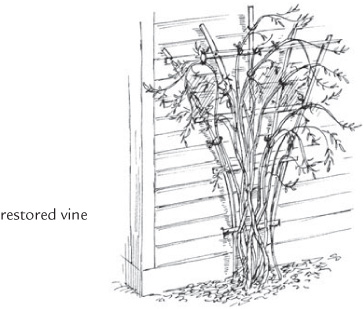

3. Return the vine to its upright position as soon as the job is finished and tie it to its support until it anchors itself.

Q Do I need to know how vines grow in order to prune them?

A Yes. The need for pruning often depends upon the way a vine grows and especially how it climbs. Some clinging vines, for instance, grow so heavy that their tendrils can’t support them. For more details about specific vines, see the lists at right and the Plant-by-Plant Pruning Guide, page 311.

Ramblers. Some so-called vines, like climbing and rambling roses (see page 121), produce long canes that should be tied to or interlaced with a trellis for support.

Ramblers. Some so-called vines, like climbing and rambling roses (see page 121), produce long canes that should be tied to or interlaced with a trellis for support.

Twiners. Many vines, such as honeysuckle and morning glory, twine around a post or wire and wind their way upward.

Twiners. Many vines, such as honeysuckle and morning glory, twine around a post or wire and wind their way upward.

Clingers. A few vines cling, holding on in several different ways. Some attach themselves by springlike tendrils; grapes and clematis grow in this fashion. Vines with tendrils need something to wrap around and are not too adept at climbing stone and brick walls. Virginia creeper and Boston ivy are better at that. They hang on with small sucker disks that attach firmly to a hard surface. Climbing hydrangea, wintercreeper, and English ivy can also cling to smooth surfaces, but instead of the sucker disks, they grip with many small rootlets.

Clingers. A few vines cling, holding on in several different ways. Some attach themselves by springlike tendrils; grapes and clematis grow in this fashion. Vines with tendrils need something to wrap around and are not too adept at climbing stone and brick walls. Virginia creeper and Boston ivy are better at that. They hang on with small sucker disks that attach firmly to a hard surface. Climbing hydrangea, wintercreeper, and English ivy can also cling to smooth surfaces, but instead of the sucker disks, they grip with many small rootlets.

Ramblers

Fourth of July rose (Rosa ‘Wekroalt’), climber

Lady Banks rose (R. ‘Lady Banks’), thornless rambler

Memorial rose (R. wichuraiana), rambler

Prairie rose (R. setigera), climber

Twiners

American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens)

Five-leaf akebia (Akebia quinata)

Kadsura (Kadsura japonica)

Kiwi (Actinidia spp.)

Magnolia vine (Schisandra propinqua)

Silver lace vine (Fallopia baldschuanica)

Star jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides)

Trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Wisteria (Wisteria spp.)

Clingers

Boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata)

Clematis (Clematis spp.)

Climbing hydrangea (Hydrangea petiolaris)

Cross vine (Bignonia capreolata)

Grape (Vitis spp.)

Ivy (Hedera spp.)

Passionflower (Passiflora caerulea)

Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans)

Virginia creeper (Parthnocissus quinquefolia)

Wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei)

Q If I plant ivy to green up the walls of my house, will it need much pruning?

A Yes, so don’t do it! Vines that cling to smooth surfaces grow well with little training, support, or other care on brick and stone structures in climates where they are perennial. They are not a good choice for wooden buildings like yours because they hold moisture, thus rotting the wood and making painting projects difficult. If you really want a woody vine near the entry, a trellis planted with clematis and a climbing hybrid tea rose would be better than English ivy or Boston ivy. For easy maintenance, hinge the trellis at the base and set it 4 to 6 inches from the wall to protect your home.

Q What do I need to know to grow twining vines such as kiwi, star jasmine, and silver lace vine?

A The twining vines can wind their way up wires, trellises, and water spouts. They are not good choices for planting to cover walls or brick buildings, but they make ideal screens on porches and fences. Some vines twine from left to right; that is, counterclockwise as you look down at them — bittersweet and Chinese wisteria, for example. Others, such as honeysuckle and Japanese wisteria, twine from right to left (clockwise).

Q My husband and I would like to grow wisteria on our house. How often should we prune it?

A Asian wisterias are extremely vigorous, too vigorous to grow on a trellis attached to your house. Instead, try Kentucky wisteria (Wisteria macrostachya), a lovely, showy but less robust vine. The cultivar ‘Clara Mack’ produces bloom clusters up to 14 inches long. If you like Japanese wisteria, grow it on a sturdy pergola by one of your doors, where the flowers can dangle in spring, and prune it annually.

Q Would growing wisteria on wires attached to the house make it easier to prune?

A Yes. For wisteria and other heavy vines, wires are stronger, and you can install brackets to hold them. No matter what you plan to train the vine on, always space it about 6 inches away from the wall to allow for good air circulation. Set out vines at least a foot from the support to give them room to expand.

Q How do I train a big vine such as wisteria to grow on our house?

A Once you have a sturdy support, follow these steps:

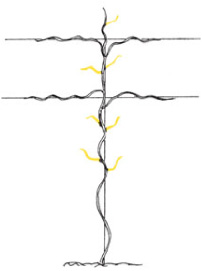

1. Establish a framework. While the vine is growing to the desired height, take time to train side branches (to reduce crowding, allow about 1½ feet between them). Tie them at intervals to the wires. Once the main leader reaches the height you want, chop off the top or train it to one side.

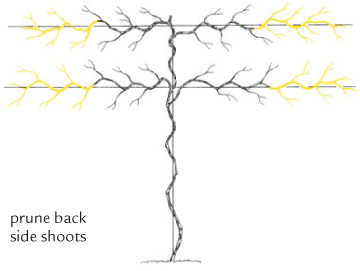

2. Prune back side shoots. Keep your plant in bounds and encourage bushy growth by cutting back horizontal-growing stems by about half. Do this in early to midsummer, while the wisteria is actively growing. Main branches can also be shortened by about half, but it’s better to do this more substantial pruning in late winter.

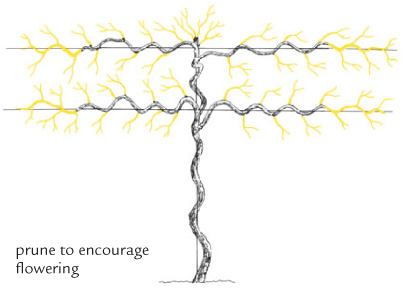

3. Prune to encourage flowering. Once you train the vine to the height and shape you want, confine all major pruning to winter or early spring, before growth starts. Cut back all shoots to four or five buds and remove suckers that appear at the base, particularly on grafted plants. Don’t fertilize, as this leads to lush foliage at the expense of flowers. (If your wisteria still doesn’t bloom after years of this regimen, consider root pruning — see page 68.)

Q My clematis isn’t blooming. What am I doing wrong?

A You probably pruned at the wrong time. You need to know the blossoming habit of your clematis (see the next answer). Also make sure to plant clematis where it will receive sufficient sunlight and to provide proper care in the form of regular watering, fertilizing, and liming if needed. If the plant is still shy, judicious pruning may help your plant grow better and begin to bloom.

If you’re starting from scratch, here’s how to encourage the most blooms. In the first year after planting, keep your clematis cut back to about 2 feet high to balance growth and encourage stem development at the base and branching. The next year your clematis may reward you by growing thick and blooming all the way up a trellis or post. If base shoots fail to develop the first year, you may need to keep the plant pruned short for a second growing season.

Q When do I prune my clematis?

A It depends upon which clematis you grow. Clematis fall into three pruning groups:

Group A (or 1) blooms in early spring on old wood (last year’s stems) and needs little pruning to keep it in shape. To keep the plant small, prune out flowering shoots right after blooming. Don’t cut into very old wood because it may not resprout. This group includes species such as Clematis alpina and C. montana.

Group B (or 2) blooms on old and new wood, with a flush of large flowers in late spring or early summer and a lesser display later on. In early spring, remove dead, weak, or damaged shoots to a pair of vigorous buds. Train stems that are left to the support. Old-fashioned ‘Nelly Moser’ is in Group B, along with ‘The President’, ‘Duchess of Edinburgh’, ‘Belle of Woking’, and ‘Mrs. Cholmondeley’.

Group C (or 3) blooms later, in summer or fall, on new growth. To keep these shapely, in early spring prune the plant hard to about 12 to 18 inches high, taking off last year’s growth. A popular example is sweet autumn clematis (C. terniflora) — ‘Comtesse de Bouchard’, ‘Gipsy Queen’, ‘Ville de Lyon’, and ‘Mme. Edouard Andre’ — and Jackman clematis (C. jackmanii).

Q I don’t like where my clematis is growing. Can I move it without hurting it?

A If you ever have to move a fragile clematis vine, pruning will make the job easier and more likely to be successful. In early spring, cut the vines to within a foot or two of the ground. Dig all around the plant roots, and move the entire root-ball — soil and all — disturbing the roots as little as possible. On an older plant, the root-ball may be nearly the size of a bushel basket. If you manage to save most of the roots, and if the vine has been cut back, survival is practically assured.

Q Are special considerations needed when pruning clematis in a cold climate?

A In cold climates, clematis need protection. Prune to get the vine off the trellis, lay them on the ground, and cover them for winter. Work carefully to salvage as much of the vine as possible. In the spring, reattach and prune away winter injury.

Choose a variety that blooms on the current season’s growth, because even if it is covered, a hard winter may kill the vine to the ground. Avoid pruning in late summer or fall.

Q My trumpet creeper has gotten so big that I’m afraid it’s going to pull over the pergola where it grows. What can I do?

A Pruning won’t harm your vine, so give that a try before you resort to digging it out. Trumpet creeper is a clinging vine. Some clingers (bignonia, clematis, passiflora, grape) grow with small tendrils that grasp wire, trellises, or other plants. Others (trumpet creeper, English ivy, climbing hydrangea, Boston ivy) have small sucker disks or rootlets, known as holdfasts, which clamp onto brick, stone, or concrete. Some clinging vines have vigorous tendrils and can support a great weight; others require occasional pruning or the weight of the vine will become too much for the tendrils to bear. Snip away large masses of dangling green, in any case, for a better appearance.

Q Do I have to prune cotoneaster?

A Woody ground covers such as cotoneaster usually need very little care, which is one of the main reasons we plant them — to avoid mowing steep or unsightly places. Occasionally, though, it’s necessary to remove competing weed and brush growth or to cut out dead or damaged parts. Shear or clip plants that grow along paths, terraces, steps, and borders as needed to keep them within bounds.

Q My ivy is taking over. How do I control it?

A Some woody ground covers such as ivy, Virginia creeper, and bittersweet are rank growers that need frequent attention unless they have lots of room to spread. Pinch back modest plantings or use shears, an edger, or your lawn mower as needed. Install metal or plastic edging, bricks, or stone to save time. Chop back large masses when they get badly overgrown; the plant will renew itself in short order. If you have trouble keeping aggressive ground covers or vines under control, consider replacing them with less vigorous spreaders.

A FEW GOOD WOODY GROUND COVERS

Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

Climbing hydrangea (Hydrangea petiolaris)

Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Cotoneaster (Cotoneaster spp.)

Heath (Erica carnea)

Heather (Calluna vulgaris)

Ivy (Hedera spp.); avoid H. hibernica and H. helix cultivars

Juniper (Juniperus spp.)

Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Memorial rose (Rosa wichuraiana)

Trumpet vine (Campsis radicans)

Virginia creeper, woodbine (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)