‘We all of us need to be free, yet not add to the burden; and if you need my voice, it is there, and I will help you find yours’

Cris Williamson1

How can you have the one of the biggest-selling independent albums in the United States and still be virtually unknown? In these days of multimedia, social media and 24/7 entertainment news platforms it seems incredible that any act can be overlooked by the mainstream, yet that’s exactly what was happening to pioneering lesbian singer-songwriter Cris Williamson and countless other women in the music industry in the 1960s and 1970s. Today we’re used to female artists controlling their own careers – just look at the phenomenal success of Madonna, Rhianna, Lady Gaga and Beyoncé – but in a record industry presided over by men, women were unlikely to get anywhere unless they submitted to what their male overlords wanted (or were convinced that the public wanted). Unless you were in an all-girl vocal group or were a flaxen-haired folk singer, you simply were not going to get signed. Yes, there were exceptions, but by and large if you did not play the game you did not get the all-important exposure. No mainstream record company was going to take a punt on someone like Williamson.

Julie Felix had done it, but she had to move to London to find support. Britain was more open to the idea of women having a musical career on their own terms and it was easier to establish a fan base via TV, radio and the press there than it was in America. In America, you were unlikely to build up anything other than a local following unless you could attract big money via a management deal or by signing to a major label. Joan Baez had the look the bigger companies wanted, but she had a mind of her own and that marked her out as a troublemaker. She did land a contract, but with the independent Vanguard label, not one of the majors; when her boyfriend Bob Dylan signed to a label two years later, it was to the mighty Columbia, then in the middle of a massive expansion programme that would see it establish its own pressing plants and distribution arms in other countries and eventually become part of the biggest music conglomerate in the world. No matter, her albums charted and her mix of traditional folk and political awareness served as a blueprint for many in the Women’s Music movement; when Baez admitted that she had a physical relationship with a woman when she was 19, her position as the patron saint of Women’s Music was assured. ‘If you swing both ways you really swing. I just figure, you know, double your pleasure,’ she revealed. The affair ‘was lovely and lasted a year,’ she added, although she continued ‘I’ve been men-oriented since’.2

Janis Ian, who was just 15 years old when she scored her first chart hit, had done it too. ‘Society’s Child’, which she wrote and recorded when she was still only 14, reached Number 14 on the Billboard chart. Although she did not come out until 25 years later, Bill Cosby perceived that she was a lesbian and spread the word, resulting in her being ostracised from mainstream television.3 Undaunted, she kept recording and, in 1975, hit the big time again with her Top Three single ‘At Seventeen’ and the album Between the Lines. In 1989, six years after her divorce from filmmaker Tino Sargo, she met Patricia Snyder, an assistant archivist at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University. Ian, who publicly came out in 1993 with the release of her album Breaking Silence, married Snyder in Toronto on 17 August 2003.4

‘We always had freedom, but, in many cases, we did not really know it,’ says Cris Williamson. ‘Women often felt they needed “permission” to be free. Women – myself included – began to examine and re-examine many of the ways in which we had lived our lives, many of the beliefs we’d come to espouse. Some of these beliefs and ways of living were handed to us by our mothers and fathers; that’s the way it’s always done, one generation engendering another.’ Born in South Dakota, Williamson was influenced by ‘every musician I heard, every book I read, every play and movie I’d seen, every person I met, every stone unturned. I truly am made of everything I’ve encountered. Life itself inspires me every blessed day, from the smallest thing to the biggest feeling. It never goes away and never ceases to amaze me.’

Williamson ‘s album, The Changer And The Changed, remains one of the best-selling independent releases of all time, with sales in excess of a million copies, and the label that issued it – Olivia Records – spearheaded a country-wide movement that would help to change the way women were treated in the music industry. Olivia was set up by a group of 10 women from Washington DC in 1974 as a lesbian/feminist collective ‘in which musicians will control their music and other workers will control their working conditions. Because we intend to avoid the male-dominated record industry we are setting up a national distribution system that will get our records out to large numbers of women all over the country.’5 Olivia’s journey began with a fundraising 45 featuring Meg Christian’s cover of the Goffin-King song ‘Lady’ backed with Cris’ ‘If It Weren’t For The Music’; the disc made the collective around $12,000, enough to fund the recording of Meg Christian’s debut album I Know You Know and to invest in some of their own studio equipment. Yoko Ono, who had been recording music with a distinctly feminist bent for a number of years, approached the collective to suggest that they collaborate on a project, however the women at Olivia declined. ‘The image that we were projecting was that we had our own music and vision,’ co-founder Judy Dlugacz told Jennifer Baumgardner for her book F ‘em!: Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls. ‘I think we weren’t smart enough at the time to realise that Yoko could have been a good thing’.6 Cris had form when it came to independent releases: her first three albums (issued one a year between 1964 and 1966) had been put out – along with a 45 – on Avanti Records of Sheridan, Wyoming, a label created specifically for her. ‘I thought it a good idea for us to invent a women’s record company,’ says Williamson, ‘And so we did, along with a distribution system, all of which served the women well. We stopped struggling, trying to fit ourselves in a structure that didn’t want us in the first place and created a structure that did, and wanted so much what we had.’ Still going strong, to date Williamson has released around 30 albums, several as part of a duo with folk singer, songwriter and producer Tret Fure.

Women had always had to battle to have their voices heard. In the UK (thanks mostly to the huge loss of life during the First World War) women over 30 were grudgingly given the vote in 1918. The nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1920, gave some women there the right to vote, but God help you if you had the misfortune to be poor, black, female and live in Alabama: you would not be able to exercise your right until 1965. In France and Italy, you had to wait until 1945 and in Portugal 1976. In Saudi Arabia women were not offered the opportunity to vote until December 2015; even today in Brunei no one can vote at all.

The Civil Rights Movement provided the perfect training ground for a newly emergent feminist movement, then popularly known as Women’s Lib. Traditionally, women had always been confronted with more prejudice and more walls to break down than men, and this was no different in the male-centric, misogynistic record industry, where female artists had always struggled to have their voices heard on their terms. The Women’s Liberation Movement was intent on changing the world for the better, and women wanted to dance to the beat of their own life-affirming, woman-centric songs. ‘Looking back upon it all, I believe all movements lead to more movements, more freedom, because not just one struggle can encompass all of the ways in which people feel enslaved,’ Williamson explains. ‘You just have to shine where you are, in the time you have, and do all you can to make it better for everyone’. Here was a chance to redefine how women – whose contributions to culture were so often marginalised – were seen in the music industry, and it was a chance, too, for women from different countries and different cultures to band together and support one another. Female musicians and technicians would no longer have to beg at the table for crumbs: they were going to create their own supportive and nurturing industry. No longer would the face on the front of the album jacket be an industry-standard pretty girl who could sing a bit but who had been signed because her look would give teenage boys something to knock one out to. They would not use sex to sell their products. In the new world of Women’s Music, talent and original thought would come first; if you had something to say, at last you could say it. This was music of healing, of solidarity and of independence.

Educator and women’s rights activist Madeline Davis could have had no idea that her song ‘Stonewall Nation’ (released as a 45 in 1971) would become recognised as the very first LGBT anthem. A founding member of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier (the first gay rights organisation in Western New York), Davis began her musical career singing in choirs before performing solo in coffee houses around Buffalo and in New York City, Seattle, San Francisco and Toronto. She began writing LGBT-themed music in the mid-1960s, while leading jazz-rock band The New Chicago Lunch and, later, her own Madeline Davis Group. In 1972, the year after ‘Stonewall Nation’, Davis taught the first course on lesbianism in the United States; that year she became the first openly lesbian delegate at the Democratic National Convention, held at the Miami Beach Convention Centre in Florida, where she delivered a powerful and moving speech challenging politicians to fight for equal rights for LGBT people. Although active in the Women’s Music scene, it was more than a decade before Davis produced her first album of lesbian-themed music, the 1983 cassette-only release Daughter of All Women, a seven-track collection of original songs, included a re-recording of ‘Stonewall Nation’. Ten years after that, she co-authored the book Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, the first written history of Buffalo’s lesbian community, and in 2009 she was honoured as the Grand Marshall of that year’s Buffalo Pride.

All-female bands like the G.T.O.s, Fanny and the horn-led Isis (who played a residency at the Continental Baths, the infamous New York venue where Bette Midler and Barry Manilow got their first breaks), took a crack at smashing through that glass ceiling, but although each was signed to a ‘proper’ company, none of them managed it. Fanny came closest, although their breakthrough chart single ‘Butter Boy’ (about member Jean Millington’s brief affair with Bowie) peaked just as the band split. ‘They were one of the finest fucking rock bands of their time,’ David Bowie told Rolling Stone magazine in 1999. ‘They were extraordinary: they wrote everything, they played like motherfuckers, they were just colossal and wonderful, and nobody’s ever mentioned them. They’re as important as anybody else who’s ever been, ever; it just wasn’t their time.’7 Jean and David remained friends: she sang backing vocals on Bowie’s ‘Fame’ single and went on to marry his guitarist, Earl Slick. Jean’s sister (and co-founder of Fanny) June went on to work with Cris Williamson and appears on The Changer And The Changed.

‘I think the world would have been different if bigger companies had been involved,’ says pioneering lesbian folk singer Alix Dobkin. ‘The mainstream didn’t know about us and didn’t care about us and didn’t pay any attention to us, so there was really no choice other than to do it ourselves. I really wanted a major label, but I couldn’t get one for one reason or another – usually my own doing. I wanted to have too much control over the product … I wasn’t about to entrust the precious lesbian, feminist exciting image I had discovered for myself into the hands of these guys.’8

During the early years of the Women’s Music movement, concerts were small and often held in village halls, gay centres or church basements. They were advertised by word of mouth, by cheaply produced handouts or for free on the few radio stations that had LGBT-friendly shows. Concerts were organised by volunteers, and performers often played for free. Organisers provided crèche services, ensured that venues had wheelchair access and even provided sign language interpreters, in an effort to make sure that these shows were as open and inclusive to as many women as possible. Margie Adam (born in 1947 in Lompoc, California) one of the pioneers of the Women’s Music movement, insisted on all-women crews during her performances and for her tours, creating a safe space for women performers and their audience as well as work for female technical crews.

‘There was a difference between the early lesbian artists and the gay male artists because the lesbian artists had the women’s movement to buoy them up,’ says Patrick Haggerty of Lavender Country. ‘It meant that their music was more widely available. There was an outlet for women’s music, but there was not an outlet for gay men’s music, in fact it was very difficult for us to make it in any kind of significant way, even in the gay community.’

Cris Williamson explains:

Women needed our music where others did not, so they had to have it. Ginny Berson [concert promoter, educator and co-founder of Olivia Records] was instrumental in the early Olivia days, organising by asking – at a concert, for example – if anyone would want to help us get the music out by going to radio stations and record stores, or have listening parties for women to introduce them to this music. Women would volunteer to do it with no previous skills most likely, but a deep desire to help women.

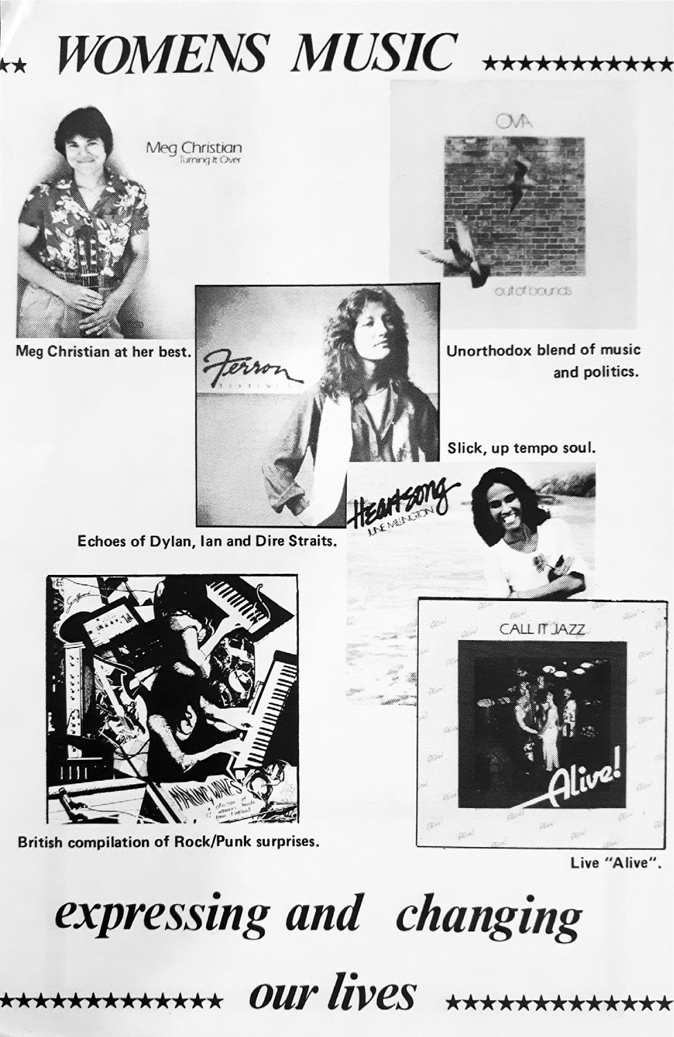

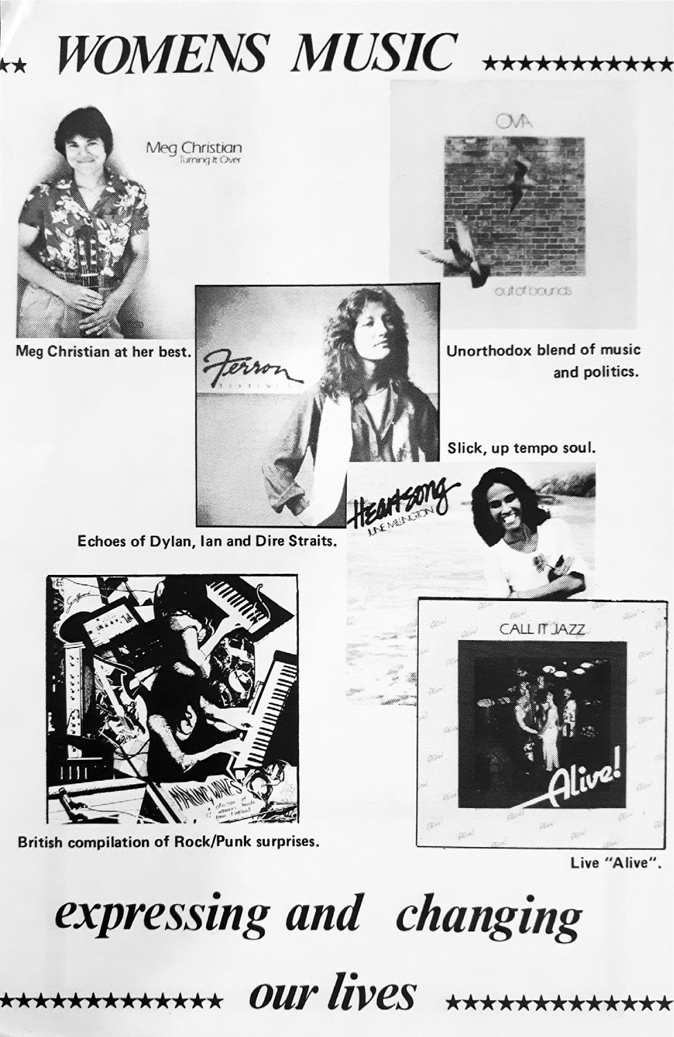

Women’s Music flyer, c. 1982

Women in the States were the first to curate women-only cultural events, set up women-only run record companies and to encourage other women to learn how to fill the technical and managerial roles in the recording industry, but even within the confines of this female Utopia there were problems. Radical feminist musicians disagreed with some venues that allowed men to attend their concerts, and some Women’s Music festivals prohibited men, trans people or even male children over a certain age from attending. ‘It was important, especially in those early days, to find women of like-mind who were making their way, making music and art of all kinds,’ Williamson adds:

I think it was echo-location of sorts: sending out signals, and hoping for return, just to know where you were in the scheme of things, or that you were, and that your music mattered an awful lot to other women, and men, too, if they were open to listening, open to witnessing strong women in the house. Being heard, appreciated, loved, helps any artist to grow and further, because she can believe in herself, in her own mystery, her own Self. This was true for me. I was received and passed on as a treasured thing. And still this is true, and still I am inspired.

But as the movement flourished, costs rose: more people wanted to attend so larger venues had to be hired; press advertising was essential to sell tickets to fill the larger venues and the pressing and distribution of records only added to the ever-spiralling costs. Former volunteers wanted (and deserved) to be paid for their time, and artists who were now selling records would no longer play for free (and why should they?) Women’s Music was a victim of its own success, and as it became bigger and more influential, the old co-operative or collective ideal was subsumed by a more straightforward business model. Suddenly there were bosses, albeit female ones, to answer to in a field that had once been anti-boss, anti-capitalist.

With these rising costs making it harder and harder for new acts to break through, Women’s Music festivals became the way to discover new artists. They were also huge social events, where hundreds of women, many of them lesbian or bisexual, could meet, socialise and support each other. Women’s Music festivals began in earnest in June 1974 when Margie Adam, Meg Christian and Cris Williamson co-headlined the first National Women’s Music Festival, which took place in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, but the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, started by young musician Lisa Vogel and her friends in 1976, quickly became the world’s premier space for women’s music, and provided a platform for artists from the internationally acclaimed Laura Nyro, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Tracy Chapman, Jill Sobule, Sia, the Indigo Girls and many others to lesser-known acts Bitch and Tribe 8.

‘Festivals were a place women could gather together in the summer, somewhere, be together, camp if they wished, eat together, and listen to their artists make the music they’d come to know and love,’ says Williamson. ‘Only a few festivals maintained their success. There were once producers in each and every major city and some towns in between, and we all went there, did shows, shared profit and loss together, but the music got there and was presented to mostly women audiences.’

The New York-born, Philadelphia-raised daughter of Jewish Communist Party members, Alix Dobkin was a stalwart of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival from its inception through to the 1990s. She grew up in a musical home listening to everything and anything. ‘Broadway show tunes were a great influence,’ she reveals, ‘and folk music of course, folk music from all over the world,’ which included the music of Soviet Russia found in The Workers Songbook. By the time she was in her early 20s, she was working as a professional folk singer playing the Greenwich Village scene alongside artists such as Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan:

The Village scene was wonderful; it was a great, supportive, welcoming community – especially in the very beginning when we all shared stuff. It was just epic. We met regularly and we hung out and we sang and we shared new songs – it was very exciting. I came from Philadelphia, which had a very active folk scene, and that was also a very caring, supportive community. I had lesbian friends in Philadelphia, and I knew of people like Frances Faye [the lesbian singer, born Frances Cohen, who began her recording career in 1936], but I didn’t have much to do with the gay scene in the Village. The Village really had several, very different artistic scenes; there was jazz, there was the whole gay scene and the folk scene.

For a while, Dobkin was married to Sam Hood, owner of the famous Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village – the place where Dylan would get his big break – but by the early 1970s she was in a relationship with photographer, radio presenter and co-founder of the radical women’s quarterly magazine Dyke, Liza Cowan. After a succession of knock-backs from major companies, she decided to strike out on her own. ‘I wanted to record, like everybody else, and I wasn’t having any success,’ she admits. ‘I didn’t have any success at Columbia and I didn’t have any success at Elektra, and so I had to do it myself. Judy Collins set up appointments for me because she liked my music. She set up an appointment for me with someone at Elektra – a Vice President or something.’ The meeting didn’t go to plan. ‘I said, “Well, okay, but I have to have women musicians,” and he said “fine, no problem,” and then I told him that I had to have a woman producer and that was “fine, we’ll find one”.’ However, when she told the label executive that she needed to have control over her own image, things suddenly became less genial. ‘“Who do you think you are?” he shouted. So that’s why I didn’t get the contract with Elektra. Thank God!’

In 1973, with flautist Kay Gardner, Dobkin produced Lavender Jane Loves Women; two years later she followed that up with Living With Lesbians. At around the same time as Lavender Jane Loves Women was released, a group of women musicians allied to New York’s Lesbian Feminist Liberation group got together to produce A Few Loving Women, a collection of original songs sold to raise money for the cause. There had been feminist recordings before: in 1972 the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band joined forces with the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band and issued the split album Mountain Moving Day, but Lavender Jane Loves Women and A Few Loving Women were the world’s first explicitly by-lesbians-for-lesbians albums.

Dobkin and Gardner met at the Manhattan Women’s Centre: adopting the name Lavender Jane for their group they advertised in the lesbian press for other women to play music with (and for), and made their live debut at the Women’s Centre in August 1973. Once they were joined by bassist Patches Attom, their album was recorded just two months later. Dobkin quickly became part of the burgeoning Women’s Music scene on America’s East Coast, releasing five further albums. ‘I guess there was a gap: none of the music out there really satisfied me in terms of my feminism and lesbianism. So yes, there was a gap that I needed to fill, so I wrote the songs and adapted them to satisfy that.’ Musician and producer Gardner (born in Freeport, New York in 1941) later became involved in establishing the Acoustic Stage venue at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. An accomplished choral arranger and composer, and early advocate of sound healing, in 1978 she co-founded the New England Women’s Symphony. Kay Gardner died of a heart attack at her home in Bangor, Maine in 2002.9

Alix Dobkin has performed widely around the world and for many years was an advocate of women-only space, performing only for women and appearing regularly at women’s music and lesbian festivals. ‘There is a lot of humour; it’s the Jewish side of me – you laugh or you cry. Plus it’s so funny. A lot of this stuff is funny. I learned from Woody Guthrie about that; he has great humour and Dylan has great humour, and, of course, the Broadway musical – the humour and the very subtle literary rhymes. There are all kinds of wonderful ways to get the message across. Music is wonderful but it has always been a vehicle for my politics.’

Cris Williamson says:

I remember thinking I had no political ideas. I had ecological ideas, ideas about the protection of the Earth, the air, the water – but were those ideas political? Some of my fans early on certainly questioned me about them, saying, for instance: “What does water have to do with Feminism?” Now we know, more than ever, that water and its protection is certainly a political and a social issue. I felt free in those days, and in these times as well, to speak my mind, my heart, my soul, and to offer up these thoughts in the shape of music that was palatable, and easily retained. I, like many around me, was making myself up as I went along. The Women’s Movement helped us immeasurably by encouraging us to be as we were, to stop trying to fit ourselves in an old mould, and create new models of strength and courage that we could then pass on to society. These new models of behaviour, of Feminist political thinking have penetrated society, like water dripping upon a stone. There is pride in this: in being whoever you are, as you are, and being happy in this world on your own merits.

For many women, especially for lesbian musicians, the growing Women’s Music circuit offered more than just the chance to play their songs; it was a space to breathe. Says Dobkin:

They were family, and it was my tribe. It was like finding your home, somewhere where, finally, you were the centre. You were important, and we only found that together. For lesbians this was the only place that we were really important, so it was very exciting. We were charged up by it. It was the most exciting period in my life. It was absolutely thrilling to me, as someone who values originality and uniqueness above everything else to be confronted with this goldmine, this field of possibilities. I knew that whatever I wrote about my life was going to be original; nobody had ever written about it before. Now that’s quite something for an artist, to realise that whatever you did would be the first. That’s pretty amazing. That’s what knocked me out and inspired me, and it was the same when lesbianism met feminism: both had existed for millennia, but never had they combined before we came along, and that was so powerful.

Maxine Feldman had written what we now think of as the earliest openly lesbian single, ‘Angry at This’ (styled ‘Angry Atthis’; Atthis was one of Sappho’s many lovers), and debuted the song live whilst performing at the lesbian bar The Corkroom shortly before the Stonewall Riots in 1969 (she recorded the song in 1972).10 Feldman, who described herself as a ‘big loud Jewish butch lesbian’ long before she began recording, had been performing since the early 1960s, occasionally finding her coffeehouse bookings refused as she was ‘bringing around the wrong crowd’.11 For a time she worked at Alice’s Restaurant (made famous by the Arlo Guthrie album and film of the same name) in Massachusetts before she moved to Los Angeles. ‘I went to California and wrote my first lesbian song, “Angry Atthis” in May 1969,’ she revealed. ‘I wrote it in about three minutes, in a bar in LA. Before Stonewall we had Mafia-run bars where you were a fourth-or fifth-class person. It was the only place for dykes to meet; we didn’t have festivals, or women’s bookstores.’12

In 1976, two years after she shared a stage in Manhattan with Yoko Ono and Isis,13 Feldman wrote the song ‘Amazon’, which was quickly adopted as a lesbian anthem and was used to open the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival every year; in 1986 Feldman gave the rights to the song to the festival. Considered too political by the larger Women’s Music labels, in 1979 she signed with the tiny Galaxia Women Enterprises and released her sole album, Closet Sale. She had opened her own successful Oasis Coffeehouse and performance space in Boston which she used to showcase new talent, but unfortunately her own health problems caused her to stop performing. By now living as a man (using the name Max, but confiding in friends that they were too old for surgery),14 Feldman passed away in Albuquerque on 17 August 2007, survived by their partner Helen Thornton. Ironically, in 2015, after it had run for 40 years, the international feminist music event the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival chose to close for good rather than be forced to admit trans performers and audience members: the festival had been facing criticism over its stance for a number of years, since trans attendee Nancy Burkholder was ejected from the site in 1991. In recent years, high-profile acts including the Indigo Girls had withdrawn their support for the festival and its ‘womyn born womyn’ policy. How would organisers have coped with Max Feldman, their benefactor, if they had still been performing?

In Britain, Women’s Music followed a different path: artists were more interested in performing and protesting than recording, and there were no women-run record companies anyway. If British acts did record anything, then more often than not the result was a cheaply put-together cassette with a photocopied insert sold at gigs to help fund the rental of the hall and the PA system. There were some exceptions, but even those that managed to get a record out had to fund the entire operation themselves and handle their own distribution (basically selling copies at concerts, through bookshops or by mail order) and advertising – which meant producing your own flyers or paying for a small ad in Gay News or lesbian monthly Sappho, just about the only publications which would take an advert anyway. Virginia Tree, a Birmingham-based lesbian musician had previously recorded with the psychedelic rock group Ghost (under her original name Shirley Kent), but in 1975 issued her own (and only) album, Fresh Out. Put out on her own Minstrel Records label, Ginny and her partner soon found the promotion and distribution of the record to be a headache; shortly after the album, a well-received collection of romantic love songs, was reviewed in Sappho she decided to sell her company and all of the remaining copies of the disc. The record was reissued, with two extra tracks, in 1987 as Forever A Willow, credited to Shirley Kent and again in 2000 under its original title.

Six-piece feminist rock band the Stepney Sisters played almost 50 benefits, conferences and festivals during their 18 months together. The band started out as friends from York University who had been sharing a squat in Stepney, London. Intent on forming an all-woman rock band, the members were predominantly straight, although two of them became involved in lesbian relationships during their time in the group and the band were often mocked for being ‘middle-class lesbians’. The group was championed by feminist magazine Spare Rib and concerts were easy to come by, however their final gig was marred when headline act Desmond Dekker failed to turn up and the women were faced with a barrage of abuse from the predominantly male audience. ‘It was ridiculous really because it wasn’t like most bands who have to struggle and bend over backwards to get work,’ member Marion Lees told Spare Rib. ‘We didn’t have the material or the experience, but before we knew what we were doing we had a lot of gigs’.15

Born in 1950 on the island of St Kitts, Joan Armatrading immigrated to England with her family in 1958. In 1970, while in the touring company of Hair, she met Guyana-born lyricist Pam Nestor and the two women began collaborating. Together they wrote around 100 songs, several of which would feature on Armatrading’s debut album, Whatever’s for Us (Cube, 1972). Yet that would be their only release. Originally intended as the work of a duo, Cube decided instead to promote Joan as a solo singer and, quite literally, airbrush Pam out of the picture. The album didn’t sell, and fights with their management and label over this new direction caused the two women to end their partnership soon afterwards. Joan signed to A&M records, releasing her next album, Back to the Night, in 1975, but it was her third album, 1976’s Joan Armatrading which catapulted the singer into the UK Top 20 and produced her first hit single, ‘Love and Affection’.

Despite a media campaign by her record company aimed at breaking her in the States – ‘we decided to do whatever we could to bring the name and talent of Joan Armatrading home,’ CEO Jerry Moss told Billboard, ‘so we went on a formidable campaign to achieve this’16 – massive sales did not follow: only one album (Me, Myself, I) went Top 30 and only one single (‘Drop the Pilot’) graced the Billboard Top 100. The problem, it seemed, was that she was difficult to categorise, although lazy comparisons were often made to other black women who played guitar. Praised by critics for ‘writing the kind of material that jumps out at you and twists your emotions,’17 the radio play she (and the label) needed did not follow. Armatrading spent the next few years building a loyal fan base in the UK and a cult following in the US, and the occasional hit single – ‘All the Way From America’ and ‘Me Myself I’ in 1980; ‘When I Get it Right’ in 1981 and ‘Drop the Pilot’ in 1983 – helped cement her reputation. Although she liked to keep her private life just that, in 2011 she married her long-time partner Maggie Butler.

Although the UK saw a smattering of folk-inspired singer/songwriters like Armatrading achieve success, Women’s Music didn’t really come alive until punk and new wave saw all-female bands like the Slits, the Bodysnatchers, the Raincoats and Girlschool achieve a level of notoriety. Successful all-female groups challenged the macho norm, and highly visible woman-led bands such as X-Ray Spex, The Pretenders, the Selecter and Siouxsie and the Banshees brought sexual equality into Britain’s homes – although few if any of these particular women were either lesbian or bisexual. The chief difference between Women’s Music in the US and the UK is that in Britain it did not exist in its own bubble. There was no Women’s Music circuit: women were simply part of what was happening and played the same venues as male bands. That many of the women becoming involved in music in the UK were untrained meant that their music was more raw, more urgent. In America, the early stars of the Women’s Music movement had come up from the folk scene: in Britain – thanks to punk – girls who picked up electric guitars were automatically musicians, and they brought ideas of social justice, of socialism and feminism with them. The music they made may not have always been pretty, but it was undeniably compelling.

‘We believe all women are natural musicians,’ Jana Runnalls and Rosemary Schofield of the London-based lesbian feminist band Ova told Gay Community News, ‘and that one of the purposes of being a performer now is to encourage women to make the connection between their personal/political lives and music’.18 Jana (formerly Jane) and Canadian-born Rosemary met in London in 1975, fell in love and started a romantic and creative partnership playing contemporary folk songs and songs Runnalls wrote herself. Beaten up and forced out of their North London squat in a homophobic attack, they found a place to live with members of the Gay Liberation Front in Brixton. With encouragement from their new-found, politically active friends, the pair started to use their music as a vehicle to express women-and lesbian-positive ideas.

Ova became a fixture of Britain’s nascent Women’s Music scene, and the band continued until the pair split up in 1989. During their time together they released four albums, established their own recording studio (like Olivia, the duo helped to train women engineers and producers along the way) and toured extensively around the UK, in Europe and in the US. The duo often found that their own radical brand of feminism was at odds with what other people assumed audiences wanted. On tour in the States, for example, they were told ‘by one very well-intentioned and supportive label not to record angry songs because anger doesn’t sell over here’.19

There was also a strong following for Women’s Music in Germany, where the scene was supported by its own magazine, Troubadora, and record label Troubadisc. Although established women’s acts such as Alix Dobkin, Cris Williamson and Ova dominated, German women had their own acts in The Flying Lesbians, Witch is Witch, Imogen Schrank, Bitch Band #1, and Nichts Geht Mehr. As the Flying Lesbians themselves declared, on the sleeve notes of their debut album Battered Wife: ‘we are lesbian and feminist and make rock music for women, but we are not professionals. We women are beginning to make our own music and to say in our own lyrics what we are; this is an important part of women’s culture.’

Holly Near’s career in music and political activism began at just eight years old, when she appeared in a talent contest organised by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Appearing in school plays and recitals kept her involved with music, and in high school she sang with folk group the Freedom Singers. After school she moved to Los Angeles, studying musical theatre and political science at UCLA. Whilst there, she attended a concert by singer and political activist Nina Simone, and it was Simone’s ability to fire up her audience that inspired Holly to think seriously about a career in music. ‘My parents loved music and ordered records from various catalogues. These precious packages arrived like gifts from the heavens. I listened to singers creating in many different styles – Lena Horne, Mary Martin, Mahalia Jackson, Patsy Cline – also folk artists like The Weavers.’20

Spotted by a talent agent when appearing in a university showcase, Near found herself with an agent before she had finished her studies and in 1968, aged just 19, she embarked on her professional career. As an actress she appeared in a number of US TV shows and, of course, in a stage production of Hair, before she became involved with the anti-Vietnam War movement and, through her political activism, in the world of feminist and Women’s Music. ‘I had already been expressing political beliefs in my work with the anti-war movement,’ she makes clear, ‘So that part wasn’t new. But the expansion of my understanding of what it means to be female added a new dimension and since there was a substantial amount of sexism in the anti-war movement, it became necessary to create some distance in order to think clearly about feminism and how my understanding of feminism was changing my music.’

Like Alix Dobkin, she found that major record companies wanted her to change her style: to be less political and more ‘pop’. Undaunted, in 1972 she founded Redwood Records, intent on issuing politically aware recordings from around the world and probably the first independent, artist-owned record company set up by a woman: pretty good going for a 23-year-old. Working from her parents’ dining table, Near’s experience would inspire Olivia, Ladyslipper (a feminist collective based in North Carolina that has produced the Catalog and Resource Guide of Music by Women since 1976), Sisters Unlimited (based in Atlanta, Georgia and created to press, market and distribute albums of songs by the feminist writer Carole Etzler, creator and producer of a series of radio dramas entitled Women of Faith) and every Women’s Music label that came after. ‘Most of the record company executives and/or managers with whom I met knew there was something worthy of attention, but it didn’t sit completely right with them,’ Near explains:

Some said the lyrics were too outspoken, some said there was not enough element of submission in my voice … and I’m sure I was also stubborn. I didn’t want to take anyone’s advice for fear they were messing with my “art” – although the fact is that sometimes it is good to take advice from people who have a different perspective. So somewhere in all of that, I decided to record my own album. In the process I discovered I needed a label, a tax ID, a way to mail out orders for the record – all those practical things. And before I knew it, I had the beginnings of a record company.

In 1975, the year that she played the second National Women’s Music Festival in Illinois, Near joined Meg Christian, Cris Williamson, Margie Adam, comedian Lily Tomlin and others at a fundraiser in LA; a year later, Christian, Williamson, Adam and Near embarked on Women On Wheels, a seven-city tour of California and the first major tour undertaken by feminist and lesbian artists in the US. That year she came out as lesbian and for several years was involved in a relationship with Christian. She says,

I didn’t know at the beginning that I was moving towards what became known as “Women’s Music”, I didn’t know at first that many people saw me as pioneering that work along with other feminist artists. But once we were able to articulate it, once we gave it a name – the name was first coined by Meg Christian, actually – then that gave us all a calling card. Sections of the women’s movement and the lesbian feminist movement began to flock to the songs, to the concerts. It was one way that women got out of the house, out of the bars, out of their smaller worlds was to come to concerts and meet other like-minded women who were all singing together. It was a very exciting time. In the same way young people gathered to challenge the constricting lifestyles of the 1950s by listening to Janis Joplin or Tina Turner or Bob Dylan, women were finding us and the collective energy gave women the courage to discover themselves more fully. In order to keep up to the emotional demand that was pouring out of this discovery, I had to work hard to keep ahead of the tsunami. I understood early on that feminism for me was not just about white women with guitars. My work in the left had educated me in the arenas of class, race, and international policy so I brought all of that to the table. Everything I knew up to that moment was poured into the songs.

With her media presence and large following, Near became the most visible lesbian singer in the US and, with her deep understanding of the way the system works, she engaged a Hollywood-based PR company to promote her and her work, the company that handled actors Jane Fonda and Alan Alda. One of the first things they did was secure her a guest spot on Sesame Street. ‘When I go on these TV shows I won’t walk right out and say, “Hi; I’m a lesbian feminist”,’ she told Gay Community News. ‘I walk out and smile and talk about growing up on a farm, sing a country love song and say “see you next year”. Hopefully they’ll think that the music is pretty and the next time they go in to a record store they’ll buy it. Then they’ll get an earful!’21 ‘Holly is the most political of all of the women in the movement, of all the old crew anyway,’ says Alix Dobkin. ‘She brought her listeners with her when she discovered the Women’s Music movement. She was inclined to be a bit more showbiz because that was her experience, she has always done great work and has made a huge contribution. Holly was the most political, and I was the most lesbian!’

‘I would not have become the artist I am today had I not crossed paths with feminist and lesbian feminist artists,’ Near reveals. ‘I am so grateful I turned towards them. We were trying to understand how we would think if we became more “woman identified” and how would that inform our music. I could not have done this kind of critical thinking alone or in isolation.’

Regular headliners of many a Women’s Music festival, the Grammy Award-winning Indigo Girls (Amy Ray and Emily Saliers) began performing together while still in high school in Decatur, Georgia. Both out lesbians, although they have never been involved with each other romantically, they released their first self-produced album, Strange Fire, in 1987 before signing with Epic Records the following year. After releasing nine LPs with major record labels, including two US Top 10 albums, in 2009 they resumed self-producing albums, issuing them through their own IG Recordings label via Vanguard Records.

With a career that stretches back more than 40 years, Ferron is a long-established part of the Canadian and North American folk scenes. Born Deborah Foisy on 1 June 1952, Ferron made her professional debut in 1975, playing at a benefit for a Vancouver-based feminist publishing house, the Women’s Press Gang. Issuing her first album two years later (on her own Lucy Records label), it would take almost two decades of well-received folk club gigs and privately-released records before a major company – in the guise of Warner Bros. – finally noticed the woman that Suzanne Vega, the Indigo Girls and countless others were citing as a major influence and ‘an important artist within folk and feminist circles’.22 Coming off the back of the success of new folk singers like Vega and Tracy Chapman, Warner thought they had a hit on their hands when they signed her. ‘This could be the album that breaks Ferron into the mainstream,’ said Warner’s Brent Gordon, talking about her major label debut, 1996’s Still Riot.23 Yet despite being praised by her bosses at Warner Bros. for her creativity and musicianship,24 it would be her only record for the label. Initially contracted to produce three albums over seven years, Ferron’s deal was terminated early and by 1997 she was once again putting out work on her own Cherrywood Station label. ‘Warner Bros. didn’t know what to do with my voice,’ she told interviewer Douglas Heselgrave,25 Although she had been out all of her adult life, she could not understand why the media constantly referred to her as a ‘lesbian singer-songwriter’ rather than simply ‘singer-songwriter’:

I was thought of only as a lesbian singer. I can remember that the New York Times listed Driver as one of the top albums of 1994. I was on a plane flying home when I first read it. I was so happy, but I couldn’t tell the guy in the seat next to me about it because under the photo of me was the caption “lesbian singer-songwriter”. Perhaps, they felt that I would have taken it as a sign of disrespect if they had not said “lesbian”, but they didn’t understand that this was not what I was selling. I was selling a way of thinking – a way of getting through a knot in your life.26

The company had worked hard to break Ferron via radio, but although she picked up plenty of airplay in California, it did not translate into sales, and the break with Warner Bros. would have massive repercussions. As well as holding the rights to Still Riot, the company had also taken over ownership of her previous two albums (which they reissued in remixed form). ‘Warner Bros. came along with a deal that broke me at the knees. I ended up losing the rights to my work. I don’t think they did anything really awful on purpose. They just do what corporations do: they eat small things. They eat minnows, and for a minute, I was a minnow.’27

It took her several years to recover from the experience. Although she continued to perform and record, Ferron also began to teach (at the non-profit Institute for Musical Arts) and to write poetry. In 2008 she released Boulder, an album of songs produced by long-time fan turned musical collaborator Bitch, with guest appearances by Ani DiFranco, the Indigo Girls and others. Queer writer, producer and performer Bitch (originally of the duo Bitch and Animal), who became friends with Ferron when they met on the Women’s Music circuit, also produced Ferron’s 2013 album Lighten-ing and the accompanying hour-long documentary film Thunder. Bitch (born Karen Mould in 1973), who more recently has been working under the name Beach, had toured with DiFranco, the Grammy Award-winning folk singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist (born in Buffalo, New York in 1970). DiFranco released her albums through her own independent label, Righteous Babe, built a devoted following through constant touring and saw the return when nine of her albums made the Billboard Top 50. Although for most of her career she self-identified as bisexual, since giving birth to her daughter in 2007 (and subsequently marrying her partner, music producer Mike Napolitano) she prefers not to talk about her sexuality in such fixed terms. ‘I think I was in my early twenties when I was having relationships with women. I’m in my early forties now. I’ve done a lot more talking about it, funnily enough, than doing it,’ she told interviewer Kathleen Bradbury in 2012.28 She’s certainly not the first artist to discover that sexuality can indeed be fluid.

‘One of the things that I’ve always prided myself on is in making public mistakes and being accessible,’ says Alix Dobkin. ‘It’s more honest; it resonates. When songwriters ask me to tell them about how to write songs I say that “if you want me to be interested in your song then send me something only you could have written”. I don’t want to hear any convention, I don’t want to be able to sing along with it the first couple of times I hear it, I’m not interested in that. It has to be original, and if you’re really honest then it will be original, because everybody is original. If somebody writes from their own true spirit, from their true soul then it’s going to be original. That’s what I’m interested in, not something that everybody else has done.’

‘Of course there is no way to predict how (signing to a major label) would have turned out,’ Holly Near adds. ‘It could have been wonderful, it could have been a disaster. But this is how my life turned out and it has been full of surprises, challenges, gifts, failures, successes – and music.’