‘I give them plenty of things to gossip about. I like rumours circulating about me, but whether or not they’re true – well, that’s another matter’

Marc Almond1

Nothing sells newspapers like a good scandal, and whereas the public seemed not to care which side of the bed you slept on, British tabloids and US sleaze sheets were still obsessed with outing gay and lesbian performers. Reporters and the paparazzi would continue to sniff around Freddie Mercury, Elton John and the Georges like a pack of rabid dogs, camping out on the doorsteps of their London apartments and following their every move, desperate to catch the moment they fell – which, naturally, each one of them would do.

Besides the press, there was another, bigger, barrier to break. Acts relied on radio play for all-important exposure, and no US radio station – outside the college circuit, perhaps – was going to play your record if it were deemed to be too gay. It was a taboo that even openly gay performers were loath to smash. There would be no obviously gay-themed songs from John until he began working with singer and songwriter Tom Robinson, and even then he would struggle with directly referring to his sexuality in song, as Robinson reveals:

The only ‘closety’ thing Elton did, which he apologised to me for at the time, was when he sang the lyrics on “Never Gonna Fall In Love Again”. There was the line “I wish he wouldn’t make me rabid/I wish he wouldn’t turn me on” he just sort of squidged it so it sounded more like “I wish she wouldn’t make me rabid”. He was a bit shame faced about that but had the good grace to apologise and I didn’t mind; I realised that his position in Middle America was such that he, ahem, didn’t want to ram anything down anybody’s throat! Fair play to him, when he made the video for “Elton’s Song”, which was about a schoolboy crush at a public school, it had a younger boy being desperately in love with an older prefect, and it didn’t pull any punches. I think the video itself got banned in America, but I don’t think Elton was at all closeted’.

MTV may have been happy to give circumspect LGBT acts airtime, but in the early years it seemed that they would only do so if you were white, and the battle to win acceptance for black musicians would need to be fought first. During an interview, David Bowie asked presenter (or Video Jockey as they were styled) Mark Goodman outright about the station’s policy towards minorities: ‘I’m just floored by the fact that there are so few black artists featured. Why is that?’ The VJ told him that the station was worried about reaction from ‘some town in the Midwest who would be scared to death by Prince or a string of other black faces’.2 It wasn’t until Walter Yentikoff, then head of CBS, threatened to pull his entire roster from the station that they finally relented and programmed Michael Jackson’s ‘Billie Jean’.

In 1984, Boy George told Rolling Stone magazine that he was bisexual, that his last relationship was with a woman and that he was looking forward to becoming a parent one day. He may have been aping his hero’s stance in the hope for acceptance, but it was still a brave move. His record company (Virgin in the UK, Epic in the US) wanted to keep milking their genderbending cash cow: they were not going to let him sabotage his career quite yet. However, after US televangelist Jerry Falwell took against him, accusing him of being a bad role model and stating that he would ‘disappear as one more fad … like Tiny Tim and a host of other relics,’ George – famous for his waspish tongue – struck back. ‘This illusion that I am promoting homosexuality is obviously rubbish,’ he said. ‘Sex is something that anybody will find out for themselves, and you cannot force somebody to be homosexual’.3 ‘Boy George is the Peter Pan of the androgynous set,’ wrote The Washington Post’s Pamela Sommers. ‘Outfitted in layers of baggy blouses and tunics, his long hair a mass of ribbons, shells and braids, his face made up geisha girl style, he’s the innocent imp, the fey rag doll. Boy George does not threaten, does not challenge, does not – despite his unconventional get-up – exude any sort of sexual allure’.4 It wouldn’t take long for the wheels to come off the wagon.

By the middle of 1986, his life was in such a mess that The Sun claimed, ‘Junkie George has Eight Weeks to Live’. The report, based on stories from his family and friends, claimed that he had developed a serious heroin habit. His publicist, Susan Blond, revealed that she knew the end was coming when trying to get him ready for a live TV show in New York: ‘Because of the drugs he was taking the make-up wouldn’t stick to his face … the anxiety was just too much’.5 In August 1986 Michael Rudetsky, a close friend, was found dead of a heroin overdose in George’s home. The following December, he was arrested for possession.

With help, George cleaned up. The Pet Shop Boys returned him to the American charts in 1993 after a five-year gap with ‘The Crying Game’, his lush, synth-led re-reading of Dave Berry’s 1964 hit, recorded for the movie of the same name, but then he discovered cocaine. In 2006 he was forced to spend five days’ community service cleaning the streets of New York after another arrest for possession and for wasting police time by dishonestly reporting a burglary. In 2009, he was jailed for 15 months for falsely imprisoning a male escort in his Shoreditch flat; he served four months behind bars. The singer had denied the charge, claiming that the victim, 29-year-old Norwegian Audun Carlsen, had stolen photos from his laptop. George admitted handcuffing Carlsen to a wall in April 2007 but said he did so in order to trace the missing property. Carlsen later revealed that the pair had been snorting cocaine.6

Looking back, George feels that prison was ‘a gift’: ‘I went into prison sober. I knew I had a lot of work to do. I’ve worked very hard at getting myself back in shape, getting my career back, getting my self-respect back. I knew it would take time, and it has. But I’m starting to feel the rewards of that work.’7 The pop music chameleon used the experience to re-examine his life and in recent years has reinvented himself almost as many times as David Bowie, with a successful stage musical (Taboo), appearances on hit TV shows (The Voice and The Celebrity Apprentice among them), two volumes of autobiography, and a side career as a respected club DJ. Oh, and he also founded his own dance label, More Protein (with friend and former member of Haysi Fantayzee, Jeremy Healy), which has had hits with Jesus Loves You, E-Zee Possee, Eve Gallagher and George himself. ‘My appetite for self-destruction and misery is greatly diminished,’ he says. ‘I’m not interested in being unhappy.’8

‘My early influences were Charley Pride, Dolly Parton, Garth Brooks, Merle Haggard and all of the old country stuff that my mom and dad listened to,’ country singer Drake Jensen admits:

Then I was introduced to Culture Club: my mother played “Karma Chameleon” constantly and I often make the joke that she played it so much that she turned me gay! She played that song 150 times a day! She bought their Colour By Numbers album and played it so much. I identify a lot with Boy George. I would love to do something with him. That’s my ultimate dream. I don’t even care if it’s music, I just want to go on a dinner date with him and talk about how much of a rebel we both were. He’s taught me a lot: he literally fell flat on his face in front of the whole world and then came back with one of the best songs of his career. When I watched the video for “King of Everything” I was bawling and crying. I’d love to have a conversation with him, just to say: “thank you”. I think that a lot of the fight that was in him, the things he suffered through … I’m very much the same. He and I have a lot in common.’

In 2015, Boy George and Marilyn were reunited, with George producing his friend’s comeback single ‘Love or Money’ the following year, Marilyn’s first new recording in 30 years.

While George was dealing with his own demons, other LGBT acts were also struggling. Marc Almond, who by the mid-1980s had cast off any pretence at being straight or bisexual via recordings with Bronski Beat (on the hit single ‘I Feel Love’/‘Johnny Remember Me’), concerts in support of International AIDS Day and an appearance on the front cover of Gay Times, was almost killed in 1993. His penchant for the seedier side of life, which added such a beautiful sense of debauchery to his records, caught up with him when two of his ‘acquaintances’ tried to throw him from a sixth-floor window. The police arrived to find an injured Almond unconscious on the floor, but instead of pressing charges for attempted murder, he decided to check himself into rehab.9 Like many of his fellow travellers, Almond has faced his own battles with drugs – he suffered from a 12-year long addiction to sleeping pills – and he admits to trying heroin, cocaine, crack, ecstasy and just about every other drug you can think of.10 The clinic Almond chose to clean up in (the Promis Recovery Centre, near Canterbury) had previously treated Elton John and his former manager/boyfriend John Reid. Visage’s Steve Strange spent many years battling heroin addiction, and in 1999 was arrested for shoplifting. It was only after details were dredged up by the newspapers that fans discovered Strange had suffered a breakdown two years earlier and had been ‘prescribed a fierce cocktail of antidepressants and tranquillisers’.11 He passed away from a heart attack on 12 February 2015, just two months after the release of the most recent Visage album, Orchestral.

When Frankie Goes to Hollywood imploded in 1987, Johnson and Rutherford both pursued solo careers, but a long-drawn-out court battle between the members of the band and ZTT put an end to their relationship. ‘It became quite hard,’ Rutherford admits:

Holly wanted to be serious and he obviously had his eye on a solo career – he didn’t want to share the stage with us any longer, and I understand that. It happened so fast and it was so big and every single day was a big day – helicopters here and there, private planes, bottles of champagne, tons of coke … it was pretty amazing but it wore our friendships out. The Liverpool album was done under absolute stress; maybe if we had more time it would have been better, we could have sold another million or whatever. It just wore out.

Paul’s solo career never really stood a chance of taking off. ‘It was an odd period for me because my partner had AIDS. I didn’t have any fight left in me. Things were getting a bit difficult and I could see Island Records [who issued Paul’s solo album Oh World] trying their best but I wasn’t at my best really and I lost interest in my own career because I was too focused on him.’ Holly Johnson helped break another taboo when, in 1993, he admitted that he was living with HIV. Luckily, medical treatment has come a long way since the early 1980s: Holly is still with us and still performing more than a quarter of a century after he first became aware that he was HIV-positive. In 2005, Erasure’s Andy Bell told the press that he too was HIV-positive, having been diagnosed a decade earlier. ‘Being HIV-positive does not mean that you have AIDS,’ he wrote on Erasureinfo.com. ‘My life expectancy should be the same as anyone else’s, so there’s no need to panic.’

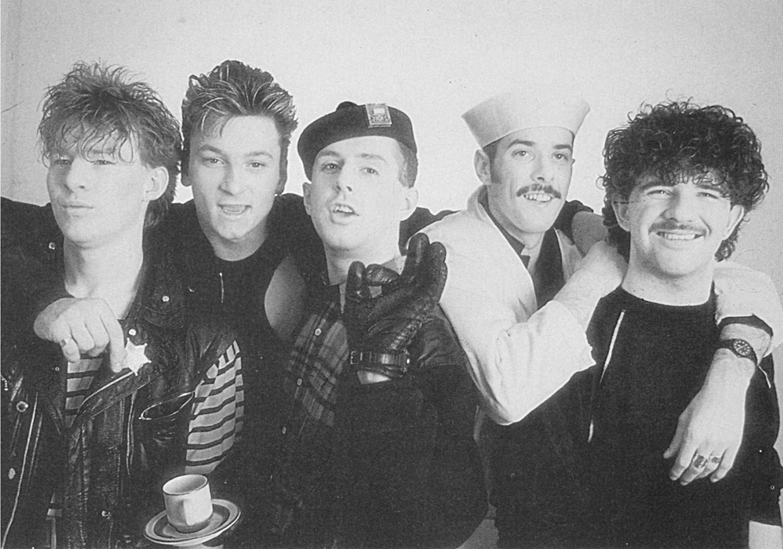

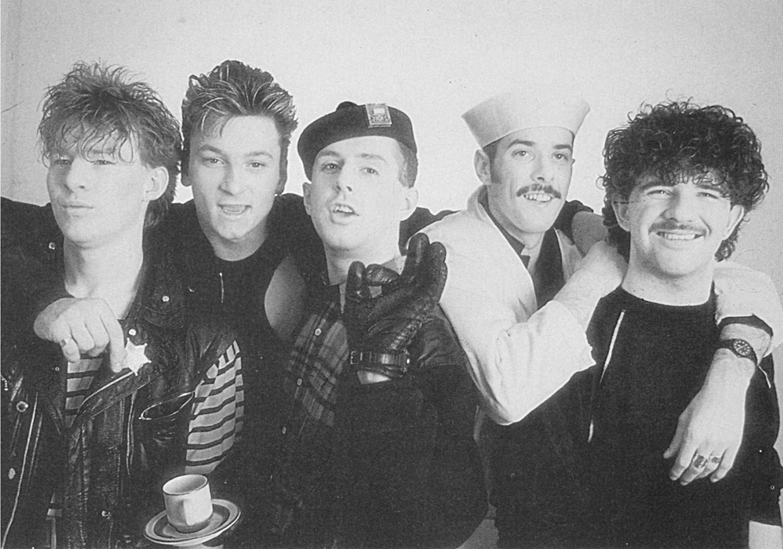

Frankie Goes to Hollywood postcard, 1984

Queen were no longer the draw they once were; by the end of 1983 it looked like it was all over for the former global superstars. After the success of ‘Under Pressure’, their massive hit duet with David Bowie, interest was waning. They still had a healthy fan base in Britain, South America, Australia and the East Asia, but with individual members releasing solo records, the band’s attempt at a disco album (Hot Space) flopping and sales slipping in America the future wasn’t looking too good. Tensions within the group – especially over Freddie Mercury’s relationship with his personal manager Paul Prenter – were at an all-time high. Mercury was a man who clearly enjoyed all of the excess that fame afforded him, and a move to Munich for tax reasons allowed him to take advantage of the city’s gay scene away from the prying eyes of the British media. However, his uninhibited behaviour was causing dissent in the ranks.

At a time when they should have been lying low and regrouping, the band walked into a PR disaster that came close to finishing them off. In October 1984, with a new album behind them (The Works: a Number Two hit in Britain but not even making the Top 20 in the US), Queen were castigated for playing a series of dates in Sun City, South Africa’s notorious racially segregated resort, at the height of apartheid. Elton John, Rod Stewart, Cher and a number of other artists had already taken the money and played there, but Queen faced the world’s opprobrium. The group received criticism in the music press for choosing money over morals, had to deal with the ignominy of a hefty fine from the Musicians’ Union and were included on the United Nations’ register of blacklisted artists.12 Mercury followed this fiasco with his first solo offering. On Mr Bad Guy, the singer continued his flirtation with dance music: ‘There Must be More to Life Than This’ and ‘Man Made Paradise’ had originally been earmarked for Hot Space. Dressed in a sleeve that featured the singer in full clone mode, it sold reasonably well in the UK but bombed in America, only reaching Number 159 on the Billboard album charts. ‘Queen might be in its twilight years,’ wrote Robin Wells in his syndicated World Of Music column,13 but within a month the global music event Live Aid (13 July 1985) would offer the group a platform to help them regain the position they had lost. They would remain global superstars until Freddie succumbed to AIDS on 24 November 1991; Mercury had tested HIV-positive in 1987 but had kept the diagnosis secret from all but his closest friends; however, his last years would be blighted by intrusion from the British media. Photographs of a gaunt and clearly ill Mercury were splashed across front pages, and reporters hung around his London home, desperate to catch him out. In his final statement, issued just the day before he died, he acknowledged the intrusion: ‘Following the enormous conjecture in the press over the last two weeks, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV-positive and have AIDS. I felt it correct to keep this information private to date in order to protect the privacy of those around me. However, the time has now come for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth.’ The press could not get enough: in the wake of Mercury’s death, it was even suggested that Madonna, Elizabeth Taylor and Burt Reynolds had tested positive for HIV.14

In 1991, the duo of Elton and George re-formed, releasing a live version of John’s 1974 hit ‘Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me’, the proceeds of which were distributed among 10 different charities, including those raising funding for AIDS research. The following year both would take part in a concert to celebrate the life of Freddie Mercury; Elton went on to establish his own AIDS Foundation that, by 2012, had raised over $200 million to support HIV-related programmes in 55 countries. In 2005 Elton entered in to a civil partnership with David Furnish (his partner since 1993) that the couple upgraded to full marriage when the law changed in 2014. When they recorded the duet in 1991, George Michael had still to make his sexuality public; after he was arrested by an undercover police officer for being ‘engaged in a lewd act’ in the rest room of a Beverly Hills park in 1998 he had little choice but to ‘fess up.

Although Michael had spent his entire career fronting Wham! in the closet, his homosexuality was no secret to those who knew him – including the band’s manager Simon Napier-Bell. ‘He’s incredibly sensible and incredibly stupid all wound up into one – as most artists are. He’s the cleverest, smartest person …’ Napier-Bell told writer Mark Ellen15 before admitting:

He never meant to be in Wham! in the first place. Wham! was Andrew Ridgeley and never anything else. He wanted to create a group but he never saw himself in it – he was the Svengali and the songwriter, and Andrew and some other guy would be the band. So when he couldn’t find the second person he thought, “I’ll join the group and act the part for him”, it was like a movie. Which is why he was right not to come out at the time, because he wasn’t George – who was gay – but a copycat Andrew.

Wham! famously became the first Western group to play communist China, and Napier-Bell turned Ridgeley and Michael into worldwide stars, with sales in excess of 25 million in just four years. The duo split after a farewell performance in London’s Wembley Stadium in front of 72,000 fans in June 1986 and Michael embarked on his phenomenally successful solo career – his first solo album, Faith, topped the UK, US, Spanish, Canadian and Netherlands charts – although he still did not come out until after his fateful encounter with that undercover officer.

Michael was, as Napier-Bell attested, a reluctant idol who did not deal well with fame and adulation – traits that Frank Sinatra found so abhorrent that he wrote to him in 1990, telling George to ‘loosen up’ and ‘be grateful. You’re top dog on the top rung of a tall ladder called stardom.’16 In the early years, in an attempt to hide his sexuality, he manufactured a relationship with backing singer Pat Fernandez, a lie that was blown out of the water by the waspish tongue of his adversary Boy George. When Michael announced that splitting with Pat had ‘broken his heart,’ the Boy spat back ‘Broke your heart did she? She lived with me for three years and all she managed to break was my Hoover!’17 He would have been much happier simply making music. When he died, on Christmas Day 2016 at his country home in Goring-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, fans were shocked, but those who knew him better were less surprised. He had not been in good health: in 2011 he had nearly died from pneumonia, spending days in intensive care in a Viennese hospital and undergoing a life-saving tracheotomy. The condition damaged his lungs – and his ability to sing – irreparably. His friend and collaborator Sir Elton John took to Twitter to disclose that he was ‘in deep shock. I have lost a beloved friend – the kindest, most generous soul and a brilliant artist.’18

The man who referred to himself as ‘the singing Greek’ was born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou to a Greek Cypriot restaurateur father and his English wife in 1963. With 11 Number One singles under his belt, and worldwide album sales in excess of 100 million, Michael was a genuine superstar. His reaction to being outed was pure genius: instead of hiding away at home waiting for the dust to settle he went on television to admit to his indiscretion, released a single (‘Outside’) with an accompanying video that made a joke of the whole affair and defiantly took a stand against the LAPD, who he – quite rightly – felt had entrapped him. He and long-time partner Kenny Goss had an open relationship, leaving George free to indulge, and although they split up in 2009 they remained close.

George Michael was a dichotomy: an intensely private man who craved sex in public places (he often found ‘diversions’ on notorious cruising ground Hampstead Heath). He was a man who shunned the spotlight but also one whose prodigious drug use saw him take unbelievably stupid risks (such as driving his car into the window of a photographer’s shop) which would invariably end up on the front pages and which, on three occasions, saw him arrested: he would spend a month in prison in 2010 after he admitted crashing his Range Rover while under the influence of cannabis. One British tabloid had two paparazzi permanently stationed outside his London residence in case he screwed up again.19

Michael was, as Elton John pointed out, incredibly generous, donating large sums to charities, giving free concerts for NHS staff, playing benefits for striking miners (he was a strong supporter of LGBT and workers’ rights) and, on several occasions, anonymously handing over cheques worth many thousands to people he encountered who needed help: the day after Michael died, TV presenter Richard Osman revealed that he once gave a couple who were trying to raise the money to pay for IVF treatment £15,000.20 A former student nurse told reporters that he gave her a £5,000 tip when she was working as a waitress to help pay for her tuition.

Even though some of the biggest names in the industry were struggling with their own personal issues, their influence – good or bad – was paving the way for a new generation of musicians to be open about their sexuality. Patrick Fitzgerald, the leader of indie rock trio Kitchens of Distinction, was certainly taking note: ‘It was a rubbish time to come out – the height of AIDS hysteria, and those folk who went on to more commercial success but kept their sexuality secret may have been more astute. I just never thought it was a problem. Don’t care really, wouldn’t have it any other way.’ 21 After his band split, Fitzgerald, who went on to work as a GP before reforming KoD in 2013, recorded under the alias Fruit, issuing the single ‘Queen of Old Compton Street’ – ‘a description of a modern London queen, which he himself is proud to be’ (according to the press releases that accompanied the single) – in 1994. Chris Xefos, of US college radio favourites King Missile (and co-author of their sole hit ‘Detachable Penis’) felt the same: ‘My biggest reason for being out is that I feel I function to my highest potential that way. People get wrapped up in trying to hide it; it’s just easier to be out’.22 Even Neil Tennant, who had resolutely refused to discuss his personal life in the media, came out in an interview with Attitude magazine:

When Bronski Beat came along, I was still assistant editor at Smash Hits. I loved those first few records. I loved the fact that they were gay, and that they were so out about it. It was the whole point of what they were doing. Jimmy Somerville was, in effect, a politician using the medium of pop music to put his message across. The Pet Shop Boys came along to make fabulous records, we didn’t come along to be politicians, or to be positive role models. Having said all that, we have supported the fight for gay rights. I am gay, and I have written songs from that point of view.23

Questions about Suede’s Brett Anderson, whose ‘is he or isn’t he’ posturing echoed that of Freddie Mercury or any number of ’70s camp pop icons, were finally answered in 2005 when he announced that he saw himself as ‘a bisexual man who’s never had a homosexual experience. I’ve never seen myself as overtly heterosexual, but then, I didn’t see myself as gay. I sort of saw myself as some kind of sexual being that was floating somewhere.’24 When guitarist Bernard Butler left Suede (known, for copyright reasons, as The London Suede in the US) he partnered up (musically speaking) with out-gay singer David McAlmont, scoring a hit with the Motown-inspired ‘Yes’ – a song Butler had originally offered to Morrissey. Similar questions have dogged Morrissey since he first became part of public consciousness, yet despite his appropriation of gay imagery and his veiled admission that he had, in fact, had a two-year affair with photographer Jake Walters,25 he has denied being gay: ‘Unfortunately, I am not homosexual. In technical fact I am humasexual. I am attracted to humans. But, of course … not many.’ 26 He has, however, been a long-standing supporter of LGBT artists, and a number of LGBT musicians have gained useful exposure via a support slot at a Morrissey or Smiths concert, including David McAlmont (who supported him in London in 1995), Phranc and Melissa Ferrick.

The self-described ‘all-American Jewish lesbian folksinger’27 Phranc opened for the Pogues on tour in 1989 – but their audience did not always take to her, as her experience in Toronto proved: ‘What’s the way to deal with it when half the audience is screaming at me, calling me a faggot, dyke, queer, every name in the book?’ 28 She had an easier time supporting Hüsker Dü and The Smiths (both in 1986), and she would later support Morrissey after he went solo. ‘My sexuality is no big deal, but I do feel very strongly about it and I feel that there should be positive examples of us out there, gays and lesbians.’ Growing up in Los Angeles, as Susan Gottleib, she came out when she was 17. ‘I was singing in punk bands but I was pretty dissatisfied. With punk you can’t understand the lyrics. I knew I had a lot to say that needed to be understood.’29

Melissa Ferrick began her career singing and playing in coffee houses in New York City but became famous overnight when, at the last minute, she replaced the opening act on Morrissey’s 1991 tour. Signed to a long-term contract with Atlantic Records, Ferrick released her first album, Massive Blur, in 1993. However, like Ferron, Extra Fancy, Steven Grossman and any number of other LGBT artists had discovered before her, her relationship with the major label was destined to be difficult, and she was dropped like a stone when her first two albums did not sell enough copies for the conglomerate. Being sacked was ‘difficult for me in all ways – physically, spiritually, emotionally,’ she later revealed, and she started to drink heavily.30 Sobering up she returned to music, signing with the indie label W.A.R. before, in 2000, founding her own label, Right On Records. In 1998 Ferrick joined Lilith Fair, the concert tour and travelling music festival started by Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan and Vancouver-based independent record label Nettwerk. Hugely successful, Lilith Fair originally took place during the summers of 1997 to 1999 and, although it did not profess to have the same political or feminist stance of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, similarly consisted solely of female artists and woman-led bands. During its initial run, the festival raised $10 million for charity; however, an attempt to revive Lilith Fair in the summer of 2010 was less successful: ticket sales were poor and several dates had to be cancelled. McLachlan and her partners have now abandoned the concept.31

Major labels were still scared of the truth, especially in the US. Known for her confessional lyrics and raspy, smokey vocals, singer-songwriter, guitarist and activist Melissa Etheridge’s eponymous debut album peaked at Number 22 on the Billboard chart, and its lead single, ‘Bring Me Some Water’, was Grammy-nominated. Born on 29 May 1961 in Kansas, when she signed to Island Records in 1986 she was warned by the label to keep her sexuality quiet.32 Despite the demand, she came out as a lesbian in January 1993 at the Triangle Ball, an LGBT celebration of President Bill Clinton’s first inauguration, telling the audience that her ‘sister, k.d. lang has been such an inspiration,’ and that she was ‘very proud to have been a lesbian all my life,’ a move which clearly influenced both the title and the material chosen for her next album. lang, who was also there to celebrate, told the audience that ‘the best thing I ever did was to come out’.33 Etheridge’s 1993’s Yes I Am and the accompanying Top 10 single ‘I’m the Only One’, catapulted her to stardom: the six-times platinum album would spend more than two and a half years in the US album chart. The next few years were busy for Etheridge – duetting with her idol Bruce Springsteen, co-parenting two children with then-partner Julie Cypher (in 2000 the couple revealed that David Crosby was the biological father of both of their kids) and recording successive hit albums. She and Cypher split, but soon after she met actress Tammy Lynn Michaels; the couple took part in a commitment ceremony in 2003, and three years later Michaels gave birth to twins. Despite being diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004 (she made a full recovery), Etheridge kept working, performing at the 2005 Grammy Awards (still bald from her chemo treatment), helping raise funds for victims of Hurricane Katrina and, in 2007, winning an Oscar for Best Original Song for ‘I Need to Wake Up’, from the Al Gore documentary on global warming An Inconvenient Truth. Etheridge and Michaels split in 2010. On 20 June 2016, Etheridge released ‘Pulse’, a song written in reaction to the mass shootings that took place at the LGBT nightclub in Orlando, Florida eight days earlier, which left 49 people dead and 53 others wounded. The Admiral Duncan, one of London’s longest-established gay pubs, was the scene of a nail bomb explosion in April 1999 which killed three people and wounded around 70, but the Pulse attack was the deadliest incident of violence against LGBT people in US history. All money raised from the sale of ‘Pulse’ was donated to Equality Florida, the state’s largest LGBT civil rights organisation.