8 Why Do Some Planets Have Rings?

Whenever we draw pictures of planets, there is usually at least one with a ring around it. This is actually the way it is in space—some planets have rings; others don’t. Alas, only the four biggest planets in our solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—have rings. The four small planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—are ringless.

Why some planets have rings and others don’t is a mystery. Perhaps rings are made when a moon comes too close to a planet and is torn apart by the planet’s gravity. Perhaps two moons ran into each other and both were blown to bits, forming a ring of debris. Or maybe the rings are leftover stuff that never became a moon when the planet was first forming.

The planet with the most spectacular set of rings is Saturn, a planet that is dramatically different from ours. Earth is solid—it’s made of rock. Saturn, though, is a big ball of hydrogen and helium, which are incredibly light gases. We use helium to fill party balloons. In fact, Saturn’s the only planet in the solar system with a density less than that of water. That means if you had a bathtub big enough, Saturn would float. It would, of course, leave a ring.

The first person to see Saturn’s rings was the amazing Galileo. He pointed a fairly small telescope at Saturn in the year 1610. And what he saw were what looked like handles sticking out either side of the planet. What was even stranger was that a couple months later, Galileo pointed his telescope at Saturn again, and the handles had disappeared. Galileo apparently said, “My glass has deceived me!”

What really happened is that Saturn had changed its position so that the flat rings had tilted up and Galileo was seeing them from the edge, like looking at a dinner plate from the side. Saturn’s rings were so thin that they seemed to disappear when viewed with Galileo’s small telescope. What could they possibly be made of?

As it turns out, the rings of Saturn are made of snowballs, ranging from about the size of your fist or your head to the size of a house. Billions of ice particles float around Saturn like the aftermath of a big snowball fight. They’re spread out around the planet in a thin sheet that’s hundreds of thousands of kilometers across but less than a kilometer thick.

The rings of Saturn are the most organized snowstorm in the solar system. Up close, you can see right through them. And if you were floating among all those snowballs, it would be easy to stick your head above them and see right across the whole system. What a sight that would be!

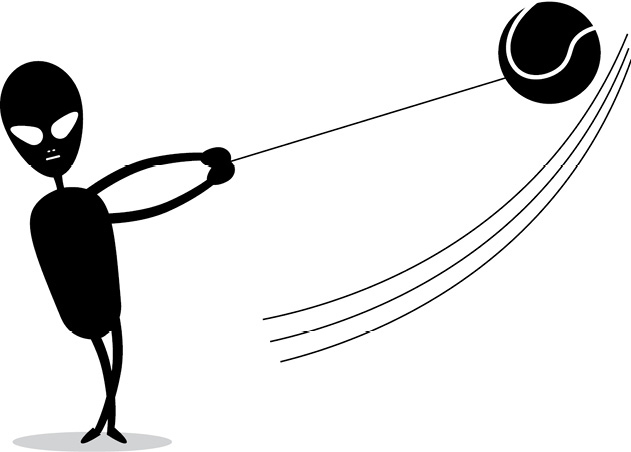

You might be wondering why the rings of Saturn circle the middle of the planet. You can find out why that is by using a tennis ball—any soft, unbreakable object, actually—and a long string.

Tie the ball to the end of the string and hold it straight out in front of you so the object is dangling just above the ground. The ball represents a ring particle, and the string is the planet’s gravity. You’re the planet! Think of your head as the North Pole and your feet as the South Pole.

All planets spin, but Saturn rotates very fast, twice as fast as Earth does, to be exact. So spin your body around on one spot while holding the end of the string out in front of you. Watch how the ball at the end of the string swings around with you. It’s trying to fly away, but the string pulls it back, the same way that ring particles are trying to get away from a planet but gravity pulls them back. The faster you go, the higher the ball rises, but it won’t go any higher than your arm holding the string, because that is where they can get the farthest away from the center of your body while spinning around. That’s why the middle of a planet—its equator—is where rings are always found.

If you want to find out why rings don’t rotate around the North or South Poles of a planet, hold the ball straight over your head. Now spin your body around the same way you did before. Maybe don’t let the ball go, though—you’ll probably get hit in the head!

When Saturn was becoming a planet, it formed from a huge cloud of gas and dust that was rotating like a flying disc. The stuff that was above and below the equator fell inward and became part of the planet itself. The stuff around the middle circled as fast as it could, but it wasn’t drawn all the way into the planet. Instead, it remains circling around, caught in this gravitational tug-of-war.

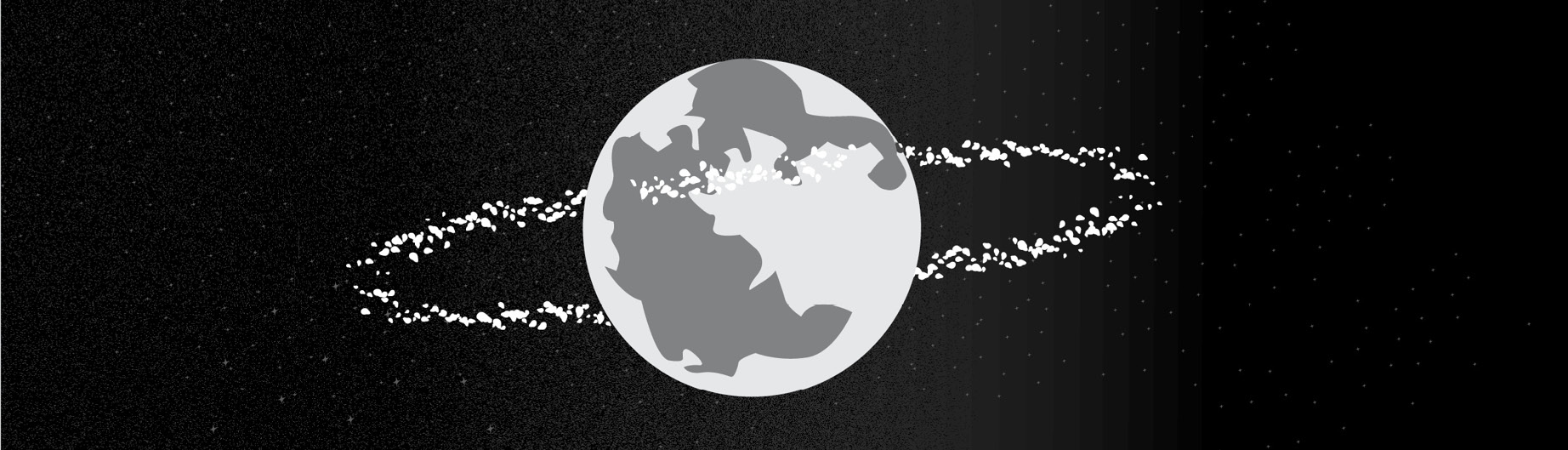

The Earth doesn’t have a ring today, but it did when it was younger. Billions of years ago, long before there was any life on our planet, scientists believe that a very large object, as big as the planet Mars, struck the Earth with a glancing blow.

The force of the impact almost ripped the Earth apart. A huge piece of our planet was sheared off and thrown into space, along with what was left of the object that hit it. For millions of years after this collision, an enormous ring of dirt and debris surrounded the Earth. Eventually, these ring particles clumped together into a ball.

That ball grew into what we now see as the moon. Hard to believe that the peaceful object that hangs so serenely in our night sky had such a violent beginning. Because our moon is far enough away from us, it isn’t torn apart by Earth’s gravity. But had the moon spiraled toward the Earth for some reason or formed much closer to the Earth than it is now, it would have been torn apart by our planet’s tides, and we would have had a lovely ring system. In fact, it might even have been more spectacular than Saturn’s—the moon is so large, it would supply a lot of material to spread out in a ring.

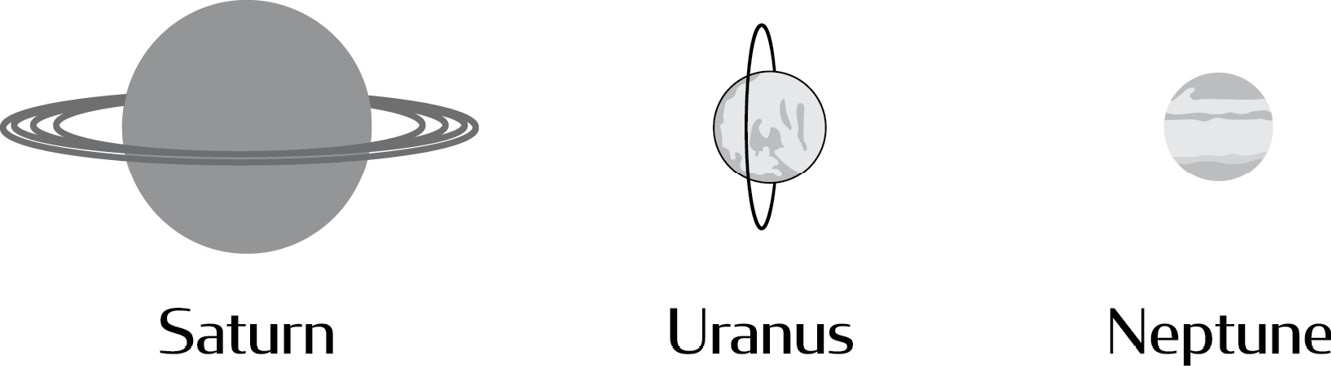

Amazingly, the rings that surround the four largest planets in our solar system are all different. Saturn’s are made of ice and are very bright and wide. The rings around Uranus and Neptune are thin and dark, like pieces of charcoal, and they’re arranged in long, thin lines with little moons running between them. The one around Jupiter is orange but barely visible. That ring is thin and made of dust that continually blows out of volcanoes on one of Jupiter’s moons, forming a kind of smoke ring around the planet.

Still, the award for the weirdest rings in the solar system goes to Uranus. It has North and South Poles like the other planets, and it turns on its axis like the rest, but for some unknown reason, the planet is lying on its side. It’s as though the planet fell over and is rolling around the sun like a bowling ball. Uranus is the only planet that does this, and, oddly enough, its moons and rings go around the same way, circling the planet’s equator.

So, the Earth once had a ring, which became our moon, and the rings around the other planets are all different from one another. That suggests rings form for different reasons. You can get a ring if a big object hits a planet, like the one that struck the Earth long ago. Rings might be leftover material from when the planet was forming, stuff that did not become a moon, or they can form when moons collide with one another. We know for sure that big planets have lots of moons. Jupiter has seventy-nine moons going around it, and Saturn has more than sixty. That creates a lot of opportunities for some of those moons to run into one another and get blown to bits, or for one of those moons to wander in too close to a planet, where the gravity of the planet will tear it apart and turn those pieces into a ring.

No one knows how long rings last. Perhaps they gather together into moons like the Earth’s ring did, or maybe they eventually spiral into the planet and disappear. Recent data from a spacecraft called Cassini, which flew right between Saturn and its rings, found a “rain” of ring particles constantly falling into the planet. Scientists calculated that at that rate, the rings of Saturn will eventually disappear… in about 100 million years. That might mean that planets without rings are too small and don’t have enough gravity to hold on to them, such as Mercury or even Venus, which has neither a ring nor a moon and has never been hit by something large. Or their rings might have disappeared over time.

Whatever the reasons, rings are among the most beautiful and mysterious objects in our solar system, so we’re lucky we’ve got some in our backyard.