10 How Big Is the Earth?

Compared to a human being, the Earth is enormous. If twenty million people (almost half the population of Canada) held hands with their arms stretched out, they would reach around it once. If you wanted to walk all the way around the planet, you would have to cover 40,074 kilometers. It would take two years of nonstop walking, twenty-four hours a day, to make the trip. That’s quite the hike!

The Earth looks flat to us because we’re so small and stuck on its surface. If you hold a big ball, like a basketball or volleyball, right up to your eye and look at the edge, the ball doesn’t look as round. The only people who get to fully appreciate the roundness of the Earth in person are astronauts who fly high above it in space.

Today, we take seeing the Earth from space for granted. But it wasn’t always this way. It took many scientific minds and centuries of technological innovation to get us to where we are. One of those early science pioneers was a man named Eratosthenes, who worked in the great library of Alexandria in Egypt more than two thousand years ago. He made the first accurate measurement of the Earth, not only proving that the Earth was round but also showing how big it was. The most amazing part? He did it all with just a stick.

One day in June, Eratosthenes was in his hometown, Syene, along the Nile River in Egypt. As he passed by a water well, he did what we all do when we pass a well: he looked down to see the water at the bottom. Not only did he see the water, he saw a reflection of the sun, which meant that at that moment, the sun was straight overhead.

Now, I’m not sure that walking by that well was an accident, because he did this at exactly noon on June 21, the summer solstice, the one day of the year when the sun is at its highest point in the sky. If the Earth were flat, then at noon on June 21, Eratosthenes would have been able to see the sun at the bottom of every water well throughout the world, because sunlight falls straight down from the sky. But if the Earth were round, he’d only see the sun in one well at a time and only when the sun was directly above each one.

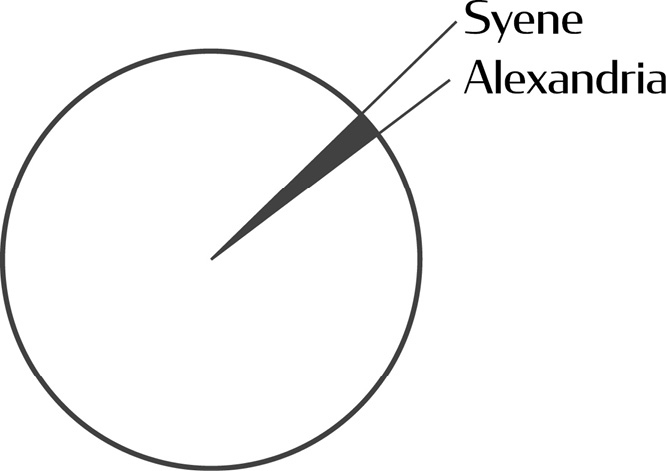

So Eratosthenes reasoned that if he could measure the angle of the sun at another well at the same time on the same date, he could tell how far around the curve of the planet he was… and, by a simple calculation, figure out the size of the Earth.

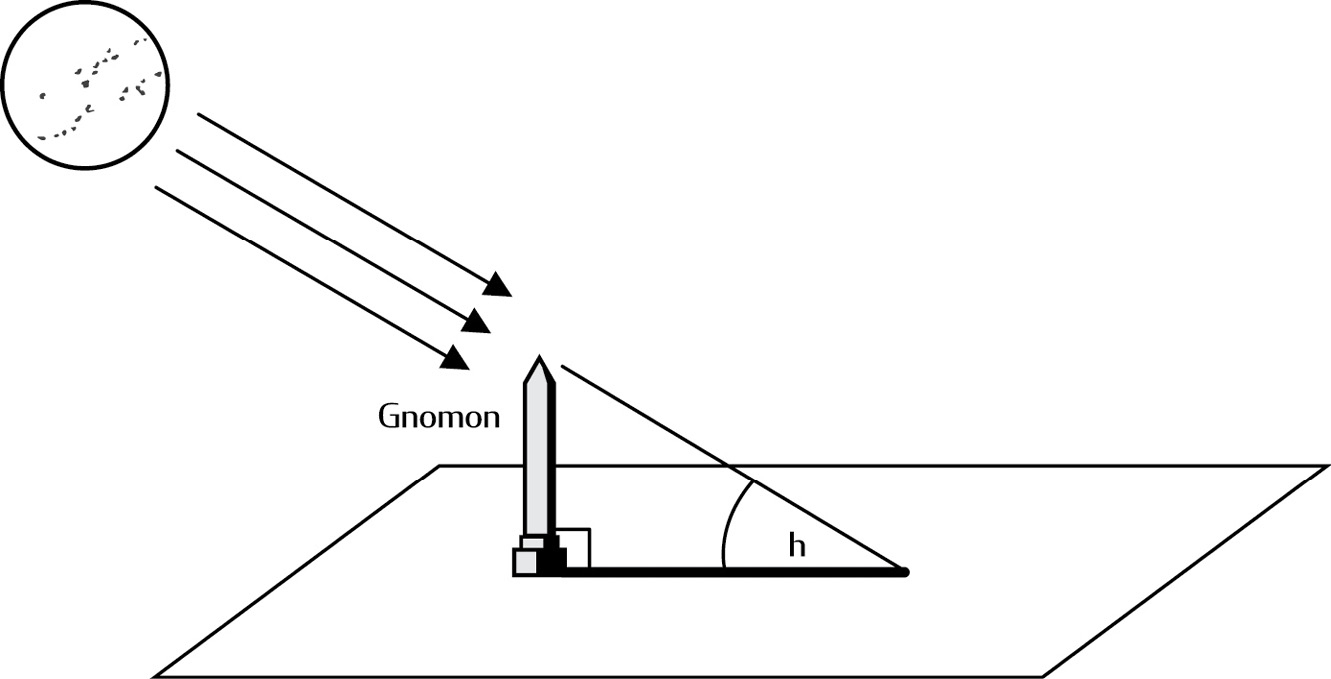

Eratosthenes waited a year to do the measurement. Just before noon on June 21 the following year, he stepped outside the library in Alexandria, several hundred kilometers north of his hometown. There was no water well to see the sun in, so to find out whether the sun was straight overhead, he used a stick. Not just any stick, but a very special one called a gnomon—it’s like a sundial that measures the angle of the sun in the sky.

Right before noon, he put the gnomon on the ground and waited for the sun to pass overhead. If the shadow of the stick disappeared entirely at noon, it meant that the Earth was flat—end of experiment. But of course, the shadow didn’t disappear. As the sun passed overhead, the shadow shrank to a little sliver, but it never completely went away. When Eratosthenes measured the angle of the shadow, it was seven degrees. It wasn’t much, but it proved that the Earth was curved.

What Eratosthenes had measured was a thin slice of a circle, like a piece of pie. Seven degrees is about one-fiftieth of a circle (a circle has 360 degrees). That meant that the distance between the towns of Syene and Alexandria was about one-fiftieth of the distance around the Earth. He knew how far apart the two towns were, so he just multiplied that by fifty.

In ancient Greece, length was measured in units called stadia—as long as a stadium, or about two hundred meters. (The stadium was where people gathered to watch races, just as we still do today.) Eratosthenes figured that the Earth had a circumference of two hundred fifty thousand stadia, which translates to roughly fifty thousand kilometers. The actual distance around the Earth is forty thousand kilometers, so he was pretty close!

Eratosthenes was the first person we know of to get a sense of how large our planet really is. Imagine what went through his mind more than two thousand years ago, realizing that the world was round and that it was far bigger than what anyone knew at the time. The ancient Greeks didn’t know that North America, South America, Australia, and Antarctica existed, because ships at that time could not cross the oceans.

Later, other civilizations built upon the discoveries of the Greeks. In 1000 AD, a Muslim mathematician named Al-Biruni found a new way to measure the curvature of the Earth by sighting along the ground to the top of a mountain. Using trigonometry, the branch of mathematics involving triangles, Al-Biruni was able to calculate the distance to the center of the Earth and, from that, figure out the planet’s size.

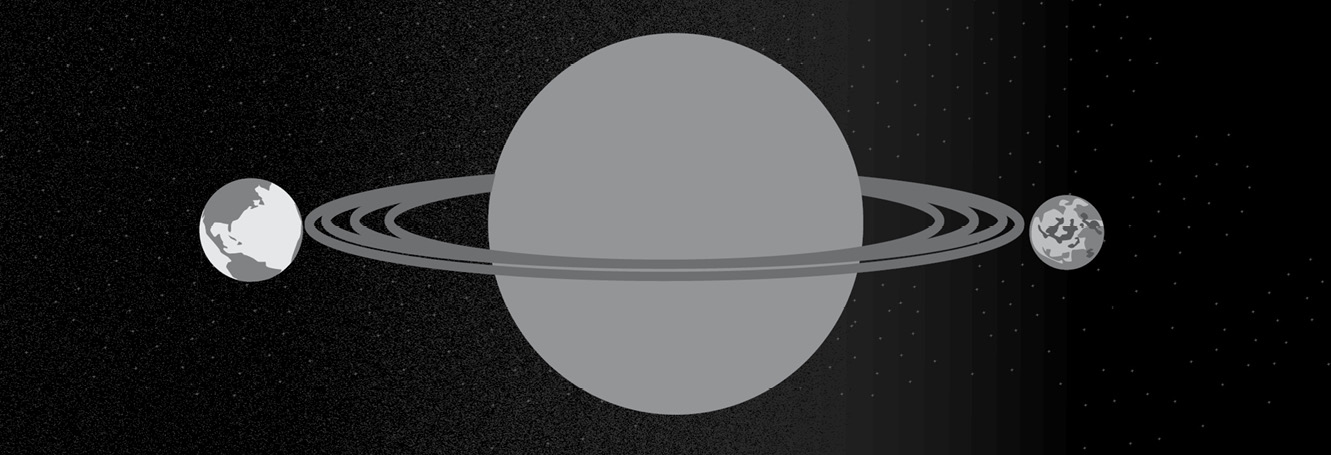

Despite how far we’ve come since Eratosthenes, we need to keep things in perspective. Although the Earth seems big to us, it is actually small as planets go. Just look at the Earth compared to Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system. A thousand Earths would fit inside Jupiter. And if we could place the Earth at one side of Saturn’s rings, the moon would be on the other side.

Most planets that have been found orbiting other stars in the universe are big, like Jupiter and Saturn. Our planet may be small, but it is the only one we have!