25 Do Other Planets Have Weather?

Almost all the planets in our solar system have weather. The only one that doesn’t is Mercury, because, like the moon, it doesn’t have any air or atmosphere. After all, that’s what weather is: moving air. But not all planets have the same type of air that we have here on Earth, so weather on other worlds can be quite different.

We live on a very active planet. Our air is always moving. It swirls around the globe, stirring up the oceans. It blows water, snow, and sand around with such incredible force that it can wipe out just about anything we can build. Tornadoes rip houses apart; hurricanes do incredible damage to entire cities. All that damage is done by air, the stuff you’re breathing right now.

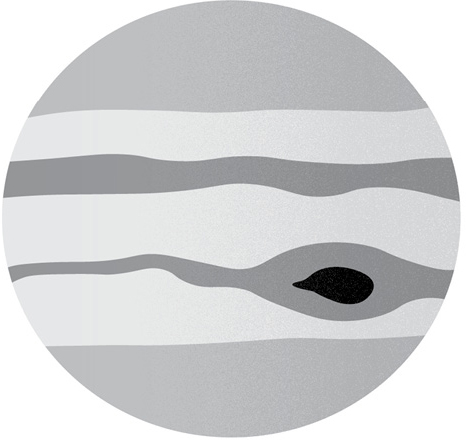

Venus, the second planet from the sun, has much more air than the Earth, with clouds so thick we can’t even see through them. Mars, planet number four, has much less air, but it has very strong winds that produce enormous dust storms that occasionally cover the whole planet. Then there are the gas giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—which are nothing but weather. These huge gas worlds, much farther from the sun than Earth, swirl constantly in endless storms. There is no land, only clouds, and they’re always moving—the weather is always bad. Clouds on Jupiter are thousands of kilometers tall and come in different colors—white, blue, and red. That’s because they’re made of different chemicals, including ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotten eggs.

To give you an idea of just how bad the weather can be on another planet, the Great Red Spot on Jupiter is a storm that has been raging nonstop for as long as we’ve had telescopes to observe it, which is almost four hundred years. This storm was spotted by Galileo when he pointed the first telescope on Jupiter in 1610. The storm is so big it could swallow the entire Earth with room to spare. It makes our hurricanes look tame.

The Earth is heated by the sun, and the sun shines most powerfully on the middle of our planet. As the Earth goes around the sun every year, the North Pole always faces up and the South Pole always points down. That means the sun shines mostly on the equator, and so the middle of the Earth gets more heat than the top and bottom of the planet. This warm air around the equator tries to move toward the cold regions, and as it pushes outward, the cold air at the top and bottom tries to come toward the equator to replace it. And if that isn’t enough, this air is moving around a globe that spins on its axis every day, which really mixes things up!

The same principle of heat works on other planets, except those worlds are either closer to or farther away from the sun than we are, and the gases that make up the air are different. Take Venus, for example. The weather on Venus is pretty gloomy. It’s very hot and totally covered in clouds. There’s not much sunlight down on the ground because so little gets down through the clouds. The clouds themselves are made of sulfuric acid, which would burn your skin when it rains. If it rains at all.

You can’t breathe the air on Venus because it’s made of carbon dioxide, which is a greenhouse gas that traps heat. The average temperature on Venus is more than 450 degrees Celsius. That is as hot as a pizza oven. And it doesn’t matter if it is day or night, summer or winter—the temperature never changes. It’s a nasty, nasty place. You don’t want to go there for a summer vacation.

What happens when we go farther away from the sun, though? The next planet out from Earth is Mars, which doesn’t have very much air, but it does have weather. Mars’s atmosphere is made of carbon dioxide just like Venus’s, but on Mars, that atmosphere is very, very thin. It would be like being on the top of two Mount Everests—very little air to breathe and exceedingly cold.

Even though it’s so cold on Mars, the planet still has four seasons. A summer day on Mars may get to zero degrees Celsius at the equator. The planet has ice caps at the North and South Poles and winds blowing on the surface. White clouds fill valleys in the early morning, and in the afternoon, when the sun heats the surface, the winds start playing with the dust on the ground. One of the robot rovers that landed on Mars in early 2004 captured images of dust devils—little tornadoes dancing across the desert. All that dust blowing around makes the sky on Mars orange instead of blue.

So these three planets—Venus, Earth, and Mars—are all quite different. One is too hot to have much weather, the other is too cold to have extreme storms, and one is just right. Aren’t you glad we live here?

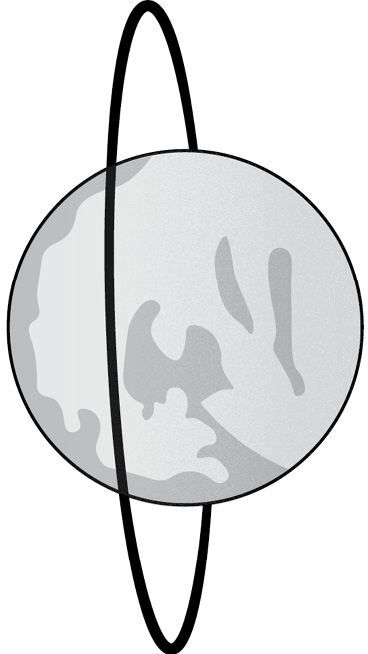

Things get even weirder the farther out in our solar system you go. Uranus is tilted on its side (for what reason, nobody knows)—so for a quarter of the year, its North Pole is aimed at the sun, then for another quarter, its South Pole is aimed at it. And between those times, the sun shines on the equator.

Sound a bit confusing? Hold a pencil in front of your face with the point up. The point represents the North Pole of a planet; the eraser at the bottom is the South Pole. Most of the planets in our solar system have their North Poles pointed in the same general direction we call north. The Earth’s pole is tilted a little, but still more or less upright.

Now turn the pencil sideways to the right, so the point faces a wall. That is the way Uranus is positioned, lying on its side. If your head is the sun, the North and South Poles of Uranus always face the same way in space as it goes around in its orbit. Move the pencil to the left side of your head, and the pencil’s point, or North Pole, will be aimed right at you. Move it around to the right side of your head, and the end with the eraser, the South Pole, will be pointed at you.

This makes for extreme seasons on Uranus, where the top of the planet is heated by the sun for half of its year and the bottom for the other half. And a year on Uranus is eighty-four Earth years long!

Some of the weirdest weather isn’t found on planets, though—it’s on their moons. Titan, a moon orbiting Saturn, is one of the weirdest worlds of weather anyone has ever seen. It’s one of the largest moons in the solar system, and it has a cloudy atmosphere. A robotic probe called Huygens landed on Titan in 2005. It passed through brown clouds, was blown by winds, and touched down on a surface that looked wet. It rains on Titan, but it’s nothing like the rain we get on Earth.

Titan is extremely cold, hundreds of degrees below zero. When it’s that cold, water is frozen solid. In fact, the ground on Titan is made of ice that’s as hard as rock. Titan’s surface is covered with river valleys and what look like shorelines and beaches. There are very large lakes, too—one of them is as large as Lake Superior in Canada. The lakes are filled with rain, but it’s not made of water. Because on Titan, it rains liquid methane, the same stuff we use in gas appliances in some homes.

Pluto is also an ice world with a very thin methane atmosphere. In fact, Pluto is so far from the sun that occasionally its thin methane atmosphere completely freezes, forming snow that falls to the ground. But the snow isn’t frozen water. It’s frozen air.

Imagine the wonders you would see, if only you could brave the bad weather on other planets. You’ll need some special gear and a spacecraft, but what a ride!