27 Why Isn’t Pluto a Planet?

Pluto used to be called a planet. Now it’s called a dwarf planet. So what happened?

When you hear the word “planet,” you probably think of Mars, Venus, or the Earth—planets that are made of rock. Maybe you think of giant Jupiter or beautiful Saturn—huge balls of gas hundreds of times bigger than Earth. You might even imagine the bluish-green worlds of Uranus and Neptune, which are also made of gas.

But the oddball planet out there beyond Neptune is a tiny, frozen world—Pluto! Named after the Roman god of the underworld, it’s a dark place, so far away that the sun is just a small, distant star in the sky. Daytime on Pluto would seem like early evening just after sunset on Earth. That also makes Pluto cold—colder than anyplace you can imagine.

This little ice world is very small. You could drop the whole planet onto the Canadian prairies and it would fit between the cities of Calgary and Thunder Bay. And it’s very far away. All the other planets, including the Earth, go around the sun in almost perfect circles. But Pluto follows a noticeable ellipse, which is sort of a football-shaped orbit. It’s also a very big orbit. One year (or one orbit) on Pluto is 248 years on Earth. In fact, Pluto hasn’t even gone around the sun once since we discovered it.

Not only that, Pluto’s football-shaped orbit is so lopsided it crosses the orbit of Neptune. Don’t worry, they won’t run into each other because the other weird thing about Pluto’s orbit is that it’s tilted on an angle—it goes above and below the other planets, as well as in and out.

When Pluto was discovered about ninety years ago, it was thought to be the only planet of its kind. But since then, many other icy planets very much like Pluto have been found in the same region of space. That’s why people are saying Pluto shouldn’t be called a planet at all.

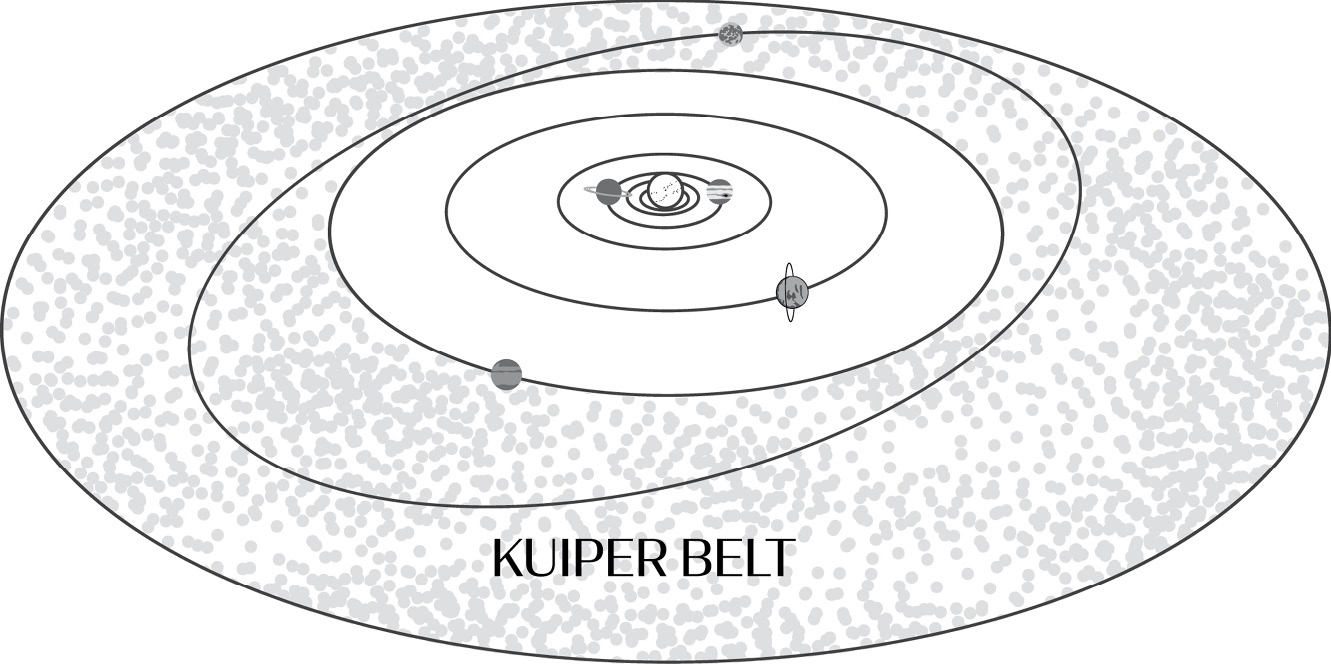

There are thousands of snowball objects surrounding our solar system in a huge swarm called the Kuiper Belt, named after Dutch American astronomer Gerard Kuiper. These ice worlds are believed to be leftover stuff from the giant cloud of gas and dust that formed all the planets and moons billions of years ago. That makes them really interesting to study because they haven’t changed much in all that time. Looking at these snowballs is like looking at the past, to a time before the sun was even born.

Pluto sits right in the middle of the Kuiper Belt. If Pluto remained a planet, we would have to classify all the other icy objects in the Kuiper Belt as planets as well. Can you imagine trying to remember the names of thousands of planets? That’s why Pluto was renamed a dwarf planet, which means a celestial body that still goes around the sun and may have moons, but is small and part of a swarm of other, similar objects. We can think of Pluto as king of the dwarves!

Most planets are fairly easy to spot in the night sky. They tend to be a little brighter than the stars, and if you watch them for a period of time—say, over a couple of weeks or a month—they change their position. They seem to wander among the stars, which is what the word “planet” actually means “wanderer.”

But Pluto, small and so much farther away than the other planets, is not very bright. It looks just like a dim star, even in a telescope. And because it’s so far away from the sun, it moves very slowly, which is why Pluto was the last planet to be discovered. And doing so wasn’t easy.

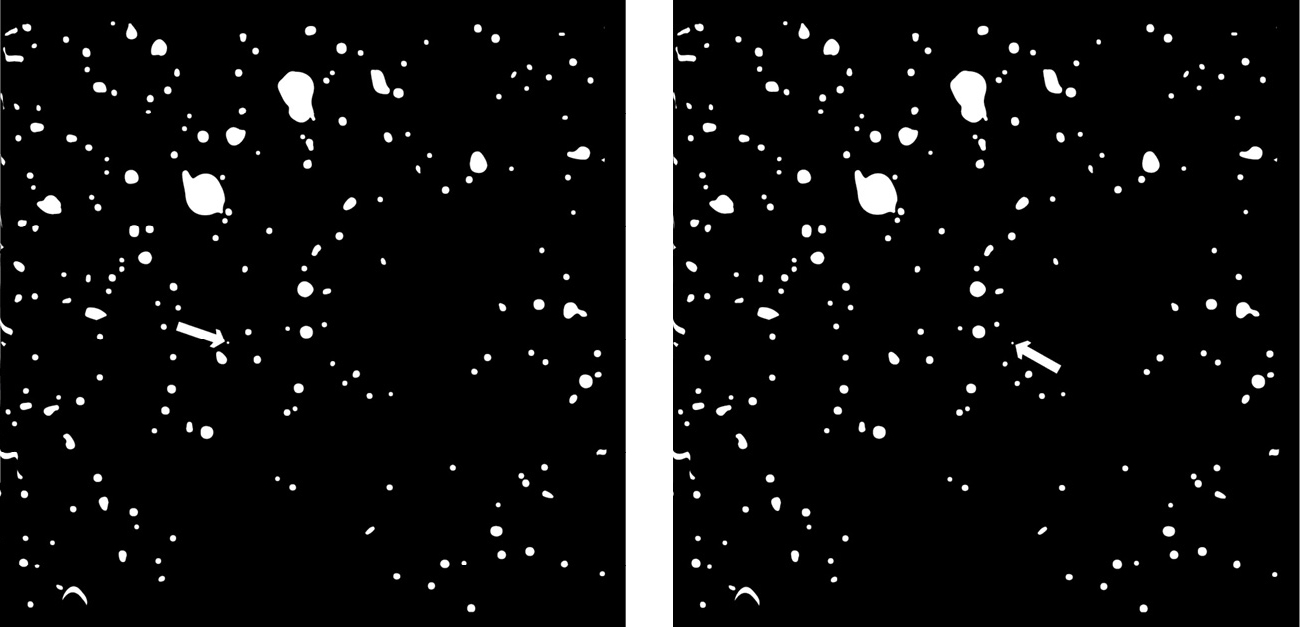

Can you tell the difference between those two photos below? Notice the little arrows—they point to the only dot that is in a different position.

That is exactly how a young astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930. He used a small telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona to take pictures of the sky, then he compared his photos to old pictures of the same areas of sky that had been taken before. While flipping back and forth between old and new pictures, he saw what looked like a star that had moved. It took Clyde about seven thousand hours before he finally spotted the tiny little wanderer beyond Neptune, now known as Pluto.

Only one spacecraft has ever visited Pluto. The New Horizons probe, about the size of a piano, took nine years to cross the solar system, then whizzed by the dwarf planet in one day in 2015. But what a day it was!

It’s cold out there on the edge of the solar system, six billion kilometers away from the sun. A warm day on Pluto is about 230 degrees Celsius—below zero! The New Horizons probe confirmed Pluto’s small size. The planet is only about two-thirds the size of our moon.

Pluto has a moon called Charon that’s half as big as it is. Usually, a moon goes around a planet, but Charon is big enough that both it and Pluto go around each other like a pair of figure skaters. So, in a sense, Pluto is actually a double planet, with two parts to it spinning around each other. Both Pluto and Charon are made mostly of ice—two snowballs circling each other in deep space. Four other little moons around Pluto—Hydra, Styx, Nix, and Kerberos—are much smaller and look like they were chipped off of something bigger. Maybe they were!

Pluto has an atmosphere, but you would choke if you tried to breathe the air. It is made of methane, which is a natural gas we also have on Earth. Imagine air made of the same stuff that cooks hot dogs on a gas stove. The atmospheric methane gives the air on Pluto a blue color. Under that blue sky are steep-sided mountains as high as the Rockies, but they’re made of ice—three kinds, to be exact. There is frozen water, like we have here on Earth. That forms the ground and mountain peaks. Then there’s methane ice that freezes out of the air. When it first forms as frost, it’s bluish white, but after the sun shines on it for a while, it turns reddish brown. Finally, there’s nitrogen ice.

Never heard of it?

Take a deep breath. You just breathed in nitrogen. That’s right, our air is mainly nitrogen gas with some oxygen in it. On Pluto, it’s so cold, our air would freeze and turn into snow. But don’t try to make a snowman out of nitrogen snow. It won’t stay together. Even though it’s white and frozen, it moves like thick pudding. A snowman would quickly drip down and become flat. That’s why there are huge flat plains of nitrogen ice all over Pluto’s South Pole.

After passing Pluto, New Horizons continued farther out into the Kuiper Belt and passed by a much smaller icy world called Ultima Thule, which turned out to be shaped like a snowman! It’s a strange place out there at the edge of the solar system. The spacecraft will eventually leave our solar system altogether to wander among the stars of the Milky Way for billions of years. Its trip has been worth it, though—after Pluto turned out to be such an interesting world, some astronomers suggested it be turned back into a full planet.

The problem of whether Pluto is a true planet or not comes down to how we define what a planet is. We used to think planets were like the Earth—big balls that orbit the sun. Then we found that there are also small things going around the sun, and we called them asteroids and comets. Then we found Pluto and discovered it’s a snowball and there are lots of little snowballs out there with it. So what do we call it? Is it a planet or something else?

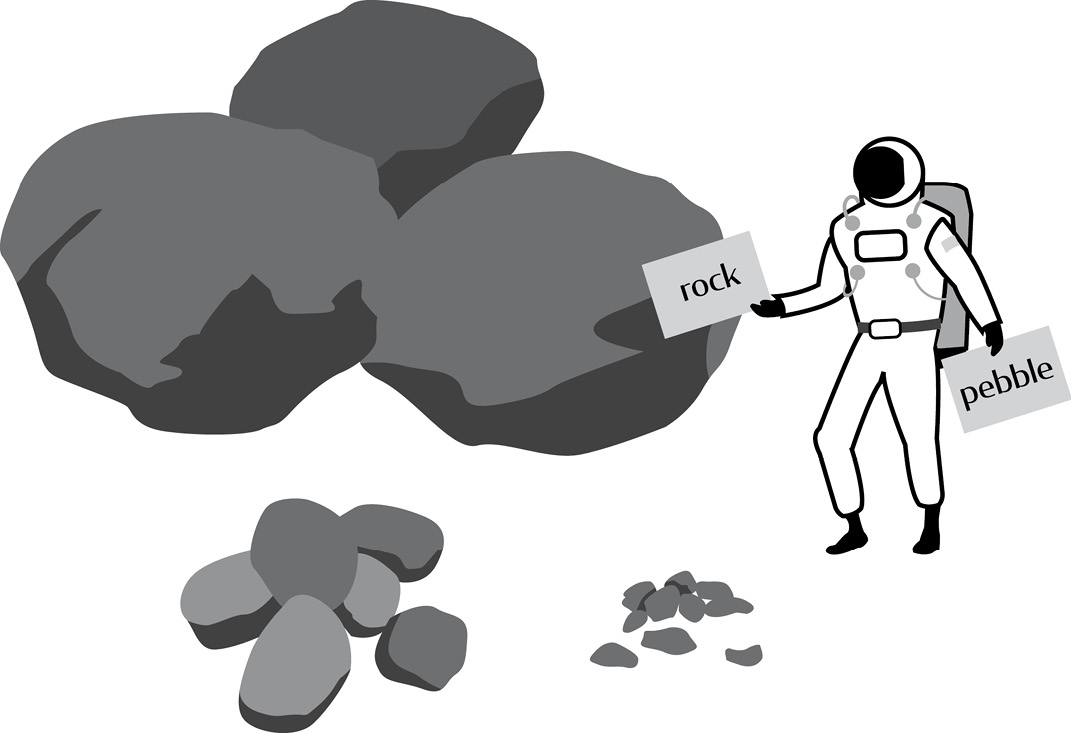

Think of it this way. Collect a bunch of different rocks and lay them out according to size. Now, which ones do you call rocks, which ones do you call pebbles, which ones do you call stones, and which ones are boulders? When objects are different sizes, each of us has our own idea of what to call them. And that’s the issue facing astronomers.

Astronomers think there could be two hundred dwarf planets wandering around our solar system. Pluto is one of four named dwarf planets among the Kuiper Belt of icy objects. But others have already been spotted out in the same region and given names, such as Sedna, Quaoar, and Eris (which is actually larger than Pluto). New dwarf planets are being discovered all the time, so there are hundreds of others out there that have yet to be named.

And not all of them are among the snowballs beyond Neptune, either. One dwarf planet, Ceres, rests in the asteroid belt that sits between Mars and Jupiter. Found in 1801, Ceres is simply a really big asteroid, big enough to be considered part of the family of dwarf planets, which makes those who study it happy.

So what’s the final word on when to call something a dwarf planet versus a fully fledged planet? Anything in the solar system that is very large, has pulled itself into a round ball, and that follows its own orbit around the sun should be called a planet. But if it’s small and round and part of a group of other objects that share a path around the sun, it’s a dwarf planet.

Clearly, our definition of planet has changed a little bit over the years to acknowledge both the big ones and little ones, and dwarves are the new kids on the block. It might seem a little confusing to have names change, but that’s how science works. As we learn new things, we add them to our knowledge base. In space science, we’re still learning about our place in the universe. There’s a whole lot out there that we haven’t discovered yet, so let’s get into space and find out more.