ON 28 MAY Lance Corporal Koimate reported that the Japanese had called at Tenaru and Lunga and at Mamara plantation, farther to the north. They had some sort of landing craft and had stayed only a few hours at each place, but they had fired many rounds from rifles and automatic weapons and killed a considerable number of cattle. The enemy could, and probably would, cause alarm and despondency along the coast. I wondered how my force would react, for now it was no longer a matter of just sitting and waiting. Our “splendid isolation” had been broken at last.

I shall never forget Koimate’s message, which a light touch by Michael Forster at Kira Kira has fixed in my mind. Forster claimed he had sighted a “light blue” plane over San Cristobal. But then, he had been at Oxford, and no doubt regarded the light blue of my alma mater as being an appropriate enemy color!

Late the next afternoon we heard tremendous bombing from Tulagi. After all the reports had been collated, it appeared that twenty-four planes had taken part in the raid, which was repeated later that evening. Gavutu was in flames, and over the top there was a huge pall of black smoke, which indicated burning fuel. The Jap searchlights were in action during the later raid, but there was very little reply from their ack-ack; this may have been owing to a shortage of ammunition, as no vessels had been to Tulagi for the last two or three days. There was no damage to our planes.

The people of Paripao had been in a nervous state ever since we had arrived, and a dispute soon developed over the cutting of a branch of the almond tree that was being used as a lookout post. Nut trees, which produced a salable crop, were jealously guarded in the Solomons: compensation was demanded, and hot words had been exchanged before I got to the scene. I went down and managed to reach a settlement with them, after much plain language had been spoken and several villagers had expressed a desire to go over to Nggela to see the Japanese. They were all scared stiff that my presence there would inevitably cause the enemy to wreak vengeance on them; they were quite convinced that the Japs would call at Aola in a day or two and march straight up to Paripao.

Perhaps their fear was well founded, perhaps not; in any case, to steady them I said I would pay another visit to Aola, just to make sure everything was all right. I was also impatient to hear further news of the heavy raid on Tulagi. The next day, therefore, I went down to Aola. All was well, but Sergeant Andrew and his faithful rear guard also needed cheering up.

I got the news from the latest Nggela patrol. Macfarlan’s estimate of twenty-four planes was disputed by Bingiti, who said that a lot of the noise during the first raid was caused by ack-ack, and that his lads had seen only five Catalinas. Most of the Japanese fuel oil and gasoline stores on Gavutu and Tanambogo had been badly damaged, however, and the causeway joining the islands had been severed. One of the Japanese antiaircraft gun pits had been burnt out. It was confirmed that there were three guns on Gavutu; the same number on Tanambogo; one on Makambo, where the gun crew were the only inhabitants; and four on Tulagi. The best description I could get of these guns, after cross-examining the scouts very carefully, was that the barrels, as measured by one scout during the night, were six feet long, and the shells were the size of small beer bottles. My guess was that they were three inches in diameter. None of us had ever seen an ack-ack gun.

The only ship to visit Tulagi Harbor for two weeks had been a small sloop armed with small guns, which had called on 26 May and left that night. No Kawanisis had been staying the night for some time, except one that had holed its bottom on a reef near Gavutu. I was amused to hear that the main Jap radio set was in the ruins of the Tanambogo mess, where the RAAF had had theirs. It was also reported that the Japs had unfortunately found a few more rifles that the RAAF had left on Nggela, and that they had again been on Savo with a machine gun asking the locals about the white men on Guadalcanal. The soldiers said that they would be coming to look for them in two weeks’ time. I did not like the sound of that.

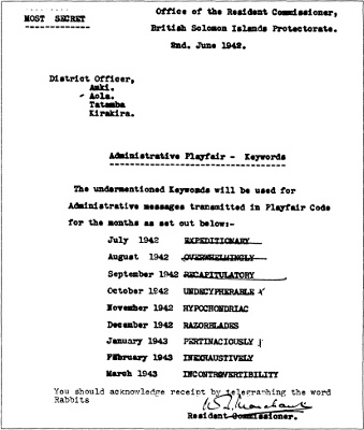

The vital words.

The first of June was somewhat less than glorious. I sent out 240 code groups of good stuff, but it rained steadily in the afternoon and we missed a good raid on Tanambogo. A small cutter, Christine, arrived from Nggela with more AIF employees; her bosun told me the Japs were very concerned over their losses of diesel oil and gasoline in the last few days. In spite of this, three Kawanisis had begun regular operations again. Bingiti’s Nggela watch, and Andrew’s reporting center at Aola, were working well. The latter sent me up summaries of what was collected; if it was important enough to require more detail, the reporter was brought up, or I went down to Aola. I was very careful about this, as there had been a tendency afoot to use information as an excuse to be sent to Paripao, where they could check that I was still on the island; that wasted my time, and besides, such men were dangerous.

The following day I held an inquiry into the shortage of rations at the goldfields police post at Koilo. Lance Corporal Tagathagoe, who was in charge, had been extremely careless, and I had no alternative but to teach him a lesson and make him pay the value of the shortage. Another lad had nearly been captured by the Japanese at Tenaru, then had compounded the problem by running away, when he should have stayed close at hand to report what the Japs were doing. If I discharged him, which was what he deserved, he would be quite likely to desert to the enemy. I therefore gave him six months’ imprisonment and employed him on lookout duties. Discipline was a very worrying problem under such conditions.

I had decided to take a chance and give all the headmen, and my own staff, their next three months’ pay: silver was extremely heavy to carry, and payment of advance wages was very good for morale. I spent two or three days typing the pay sheets; our mobility would be increased if that work were over and done with.

It rained solidly most of the time. There was little wind, and there were no gaps in the fall of rain between our lookout and Tulagi, so our observation suffered. I was very busy anyhow, trying to pack up as many of the office papers as possible: we might have to be on the move, and I wanted to reduce what we had to carry to an absolute minimum. We heard several raids on Tulagi and on 4 June saw a big fire, which we hoped meant that the fuel oil was burning. The results of the bombing must have been good, for even through the rain a pall of smoke could be seen over Tulagi and Tanambogo for several days. Following this, however, there was a lull in our bombing, which lasted almost a week.

At Paripao, spare hands had been busy building a henhouse and planting more vegetable gardens. The food supply for the hefty policemen, who normally got at least a pound of rice and an eight-ounce tin of meat every day, was bad, and it would get worse. I had a small quantity of rice, and quite a lot of tinned stuff, but I was already eating a lot of sweet potatoes and taro. The hens would give us eggs, and occasionally provide our teeth with exercise, but to the policemen a chicken was a meal for only one!

I had long since consumed my usual smoking tobacco, and F. M. Campbell had sold me three blocks of Derby plug. It would have been difficult to drive a nail through them! Besides, the stuff was strong enough to make a donkey hiccough. The locally grown tobacco was of excellent quality, but it was usually badly cured, and the islanders twisted it into a huge plait as long and as thick as a man’s arm. I used some to dilute the Derby plug. It wasn’t exactly “my smoke,” but it was better than an empty pipe.

The charging engine was beginning to pack up, and I had to decarbonize it at last. It was filthy inside, but fortunately it did not take very long to scrape off the tarry deposit of carbon. I had to send down to Ruavatu to get some valve paste for the two valves to make a proper job of it, and when the engine was all put together again it had the decency to work more smoothly.

I was getting anxious about the nonarrival of new code words promised by Bengough, so when on 7 June a messenger arrived from Aola to say that the Gizo had been sighted I was so impatient that I tramped down through the mud and collected the vital words and a lot of official mail. After the rude exchanges of messages that had occurred from time to time, it was a pleasant surprise to get a note from the resident commissioner telling me that our “Tulagi gossip column,” as Macfarlan called it, was highly appreciated in the proper quarters. A less encouraging note instructed us not to send more than twenty or thirty code groups at one time, as it had been confirmed that the Japanese could find out our positions provided there was a certain length of signal. (I expected that their direction-finding equipment had located me by now anyhow, but I felt happier the less I was on the air.) Before going back to Bengough, the Gizo had to take the new code words to Forster on San Cristobal, then return to Aola. This route would give her the maximum cover from the coastline. We worked out departure and arrival times and warned them to keep very close to the schedule.

Sergeant Andrew told me that they had been so busy the last ten days they had not even had time to catch any fish, and had been living entirely on sweet potatoes. So, early next morning, we walked along to the back of Ruavatu plantation, where I shot a bullock and cut it up into quarters. Half went to Aola and the rest to Paripao, with a joint for the missionaries at Ruavatu.

I got back to Paripao at 1000; the lookout reported that all was quiet. Bingiti had reported that, owing to the size of the Tulagi garrison, the Japs had rations for only two or three weeks. I spent some time speculating on what their next move would be. Whether they had landed on Guadalcanal because they were seeking food, or whether for a more sinister purpose, remained to be seen.

That morning I had a signal from Rhoades, which at the time struck me as rather humorous, though now I cannot see why. It ran something like this: “Japs again at Savo complete with one machine gun and tin hats, enquiring for whereabouts of white men on Guadalcanal. Said they would go there in two weeks’ time—stop—Japs also at Tenaru and Kookoom joy riding on horses Friday last—nearly caught police boy.” What made me laugh was the image of the Japs, riding after my unfortunate constable. Lever’s would have been disappointed with the performance of their horses!

Shortly after breakfast on 10 June, there was another jolly good raid, which must have caught the Japs unawares. Just then I happened to be interviewing two of Bingiti’s scouts, who had brought the pleasing news that the earlier raids had caught many Japanese out of their slit trenches; two hundred had been killed, and their wounded completely filled the aid station. I hoped the postmortem information on these raids would be of use.

I still had great trouble with the indispensable charging engine, which seemed to be developing an asthmatic cough. Daniel thought there might be water in the benzine, so we tried filtering it through my bush hat. (The hat had been “acquired” from the RAAF; it didn’t look awfully military, but it was far better than the brown homburg in which I had returned from Australia.) The filtering brought about a great improvement, and the hat survived.

As regards a uniform, I had one pair of drab shorts, but my khaki shirt, after repeated washing, had faded to a very pale canary yellow. I tried dyeing it with coffee and tea, but they didn’t give it much color. Then I tried soaking it in a muddy solution of red earth; this was more successful, but it made the shirt very scratchy to wear, and the color did not last very long. I was all right for long hose, and my last pair of shoes and one pair of gym shoes were still holding out. When on the move I had a leather belt and a short-nosed .38 pistol, which someone had left behind at Aola. I also had a Webley .45 that I had picked up somewhere, but such a cannon was not made for bush walking.

When I was about to go to Aola I had sent one of the scouts down to the Bokokimbo River, far below the Paripao ridge, to see if there were any river fish worth eating. As there were so many good fish in the sea, the coastal people rarely fished in rivers. My researcher returned with a very handsome beast, which weighed about six pounds: it had large, horny scales, similar to the tarpon’s, and it was slightly flattened, like a bream. When cooked it had fairly firm flesh and a good taste. This was the first river fish that I or most of the scouts had ever had; we all felt that we wouldn’t mind eating it again, and hoped it could be caught farther inland. Life was pretty tedious, but it could have been worse.