This book is about the Staffordshire Potteries: how it became one of the most distinctive industrial districts in the world and how you can find your ancestors there.

North Staffordshire is rightly proud of its industrial heritage. For almost 300 years from the mid-1700s, this isolated community on the western edge of the Peak District became a microcosm of the Industrial Revolution. Working with the simplest of tools and raw materials, often in wretched conditions, a skilled and industrious workforce produced objects of great beauty that were admired and desired around the world. Their efforts secured for Britain a pre-eminent place in a key industry that had previously been thought of as unprofitable, or reliant on royal patronage or Far Eastern expertise.

The processes and skills required were extraordinary. The factories, or potbanks, with their distinctive bottle ovens turned out ceramic wares of every shape and description from domestic utility items and fine bone china, to decorative tiles, sanitary ware and building materials, and later on specialized industrial products such as electrical insulators. But this innovation and creativity came at a cost. Working conditions in the potbanks were often grim, and the bottle ovens – along with the area’s other staple industries, mining and steelmaking – heavily polluted the environment, with consequent impacts on health.

It was not a promising start. A visitor to the area in the Middle Ages would have found a few farmer potters eking out a living on the sides of the windswept hills. They would tend their farms during the summer and spend the winter months fashioning butterpots to use in their dairies and crude domestic items to sell in the local markets. But slowly and surely a body of expertise began to accumulate. Driven by the values of the Midlands Enlightenment – a conviction that science and technology should be applied to improve the human condition – pottery entrepreneurs such as Josiah Wedgwood began to apply inventions and discoveries to improve their wares. Some of these innovations were of their own making, others came from far and wide. In doing so, they turned what had been a craft into an industry with a worldwide reputation.

While names such as Wedgwood, Josiah Spode, Thomas Minton, John Astbury, John Doulton and Enoch Wood are credited with laying the foundations of the pottery industry in Staffordshire, many of the most talented people are known only to history. For hours on end, year in year out, these unknown craftspeople (both men and women) toiled in the potbanks producing some of the most exquisite creations ever made by human hand. It is these people we set out to find when we embark on the search for our Potteries ancestors, and we can be proud of them too.

That this distinctive heritage has tended to be overlooked is due, at least in part, to the Potteries being its own worst enemy at times. In the nineteenth century, civic rivalry between the six Pottery towns continually held the district back, denying it the momentum and influence it deserved. A municipal building boom within the rival towns led to a proliferation of town halls, market halls, theatres, libraries, schools of art, mechanics institutes and public parks far greater than the relatively modest population warranted. Often these public baubles were elaborately decorated with locally produced ceramic tiles and other adornments. Many of these buildings have been lost but a significant proportion still survives, making a visit to the city a feast for the amateur photographer and the architectural historian alike.

More than any other city in the country, Stoke-on-Trent came to be defined by what it made. The ceramic industry’s grip on the area was immense – hence the name ‘the Potteries’ – giving it the greatest concentration on a single product of any industrial centre in Britain. At the industry’s height before the Second World War, more than 2,000 bottle ovens punctuated Stoke-on-Trent’s skyline. Emerging without any form of masterplan, there seemed to be at least one potbank on every street, interspersed with workers’ housing (often of very low quality), like drones around the queen bee. It was a dramatic landscape, captured most evocatively in the novels of Arnold Bennett, the Potteries’ most famous son. And the fall, when it came, was equally dramatic.

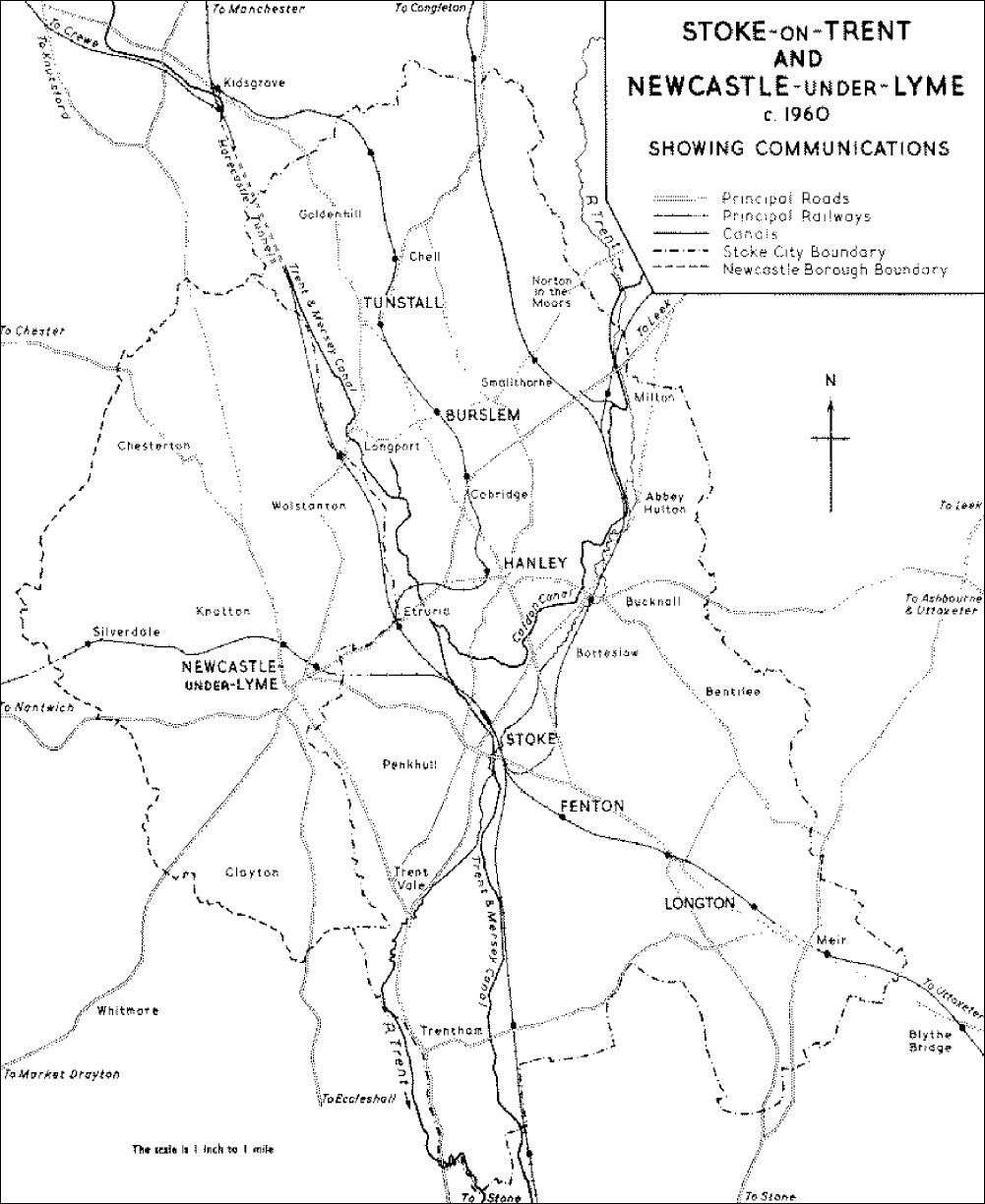

Environs of Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme, c. 1960. ( Victoria County History)

When the economic tide turned, taking the pottery jobs abroad, the blow dealt to Stoke-on-Trent was severe and for a while appeared almost fatal. In other industrial cities redundant factories, warehouses and mills have been repurposed: after lying derelict for a while, regeneration efforts have seen them converted into offices and flats, breathing new life into the original fabric. But no one can live or work in a bottle kiln. The potbanks were levelled in their hundreds, ripping the heart out of the communities they served. Probably no urban landscape in Britain has changed more dramatically in the last 100 years than that of the Potteries. Today, the area is bouncing back, led by a new wave of pottery entrepreneurs such as Emma Bridgewater, as well as focusing on high-tech manufacturing industries and services.

The Potteries is an area with a resilient working class, industrious entrepreneurs, a strong reforming tradition and a rich cultural heritage. For family historians this means that we may find our ancestors in many settings and across all social and religious groups. While, in all likelihood, they will be living in a small terraced house in Burslem or Hanley, do not be surprised if your ancestor turns out to be a Methodist preacher, a performer in one of the many theatres, a school teacher, or a train driver on ‘The Knotty’ (North Staffordshire Railway (NSR)). Even working in the potbanks they are likely to have been highly skilled.

North Staffordshire was, and in many senses still is, a land in-between. Ever since the Romans first cut Ryknield Street linking Derby and Chester, people have been hurriedly traversing the area on their way to somewhere else. Although only 40 miles from major conurbations, historically the Potteries identified neither with the textile-based economy of the North-West, nor with the metal-bashing economy of the West Midlands. The harsh landscape of the Staffordshire Moorlands, to the east, and the lush arable land of the Cheshire plain, to the west, were equally alien.

Unusually among British cities, Stoke-on-Trent is what geographers call ‘polymorphic’. Rather than a single historic settlement that grew out radially over time, the city of Stoke-on-Trent was formed through the amalgamation of a number of smaller towns that had gradually coalesced. There were six of these towns, running more or less in a line from north to south: Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton. The city itself is relatively young, federation having been achieved only in 1910. It was the need for a collective moniker for an area that had long been a single economic (though not administrative) unit that led to the name ‘the Potteries’ (the term was in use as early as 1802). Stokies, as the locals call themselves, have a strong sense of identity that even today often owes more to the constituent towns than the city as a whole.

For the family historian, then, research in ‘the Potteries’ has to take into account this multi-layered picture. While the primary focus in this book is the modern city of Stoke-on-Trent, on occasion the discussion necessarily moves down a level to consider the circumstances of the six constituent towns. At other times, the focus shifts up to address North Staffordshire as a whole. Two districts frequently mentioned are Newcastle-under-Lyme, the historic borough town on the city’s western fringe, and the Staffordshire Moorlands, a rugged hinterland to the north and east. Stoke-on-Trent – and therefore our ancestors who lived there – had close links with both these neighbours and therefore it makes sense to include them in a family history guide such as this.

As a late arrival on the national scene, Stoke-on-Trent is a constituent part in some of the jurisdictions used by family historians and is the defining entity in others. Much of the modern city was originally accounted for by the ancient parish of Stoke-upon-Trent (now generally known simply as Stoke to distinguish it from the city of Stoke-on-Trent). The relevant jurisdictions in relation to aspects such as civil registration, the Poor Law, local government and legal matters are described at appropriate points in the text.

View of the Potteries, 1926. (Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons)

One of the pleasures of family history is that every story is unique. Every family will have followed its own winding road and left its own trail, and generalizations have limited value. Nevertheless it is useful to highlight some of the key issues and themes the family historian is likely to encounter in the search for their Potteries ancestors.

Firstly, researchers have the facilities of an excellent archives service at their disposal. Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives Service (SSA) is recognized as one of the best performing and most professional in the country, and is the home to world-class collections. As the name suggests, it is a shared service funded jointly by Staffordshire County Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council. The archives are split between sites at Stoke-on-Trent and Stafford, with search rooms at both locations, and as a researcher you may need to travel between one and the other to find the sources you are looking for. Fortunately, the SSA is investing heavily in digitization and many of the key sources, including parish registers and wills, are available online. The SSA’s facilities and how to access them are described more fully below in the sections on Principal Archives and Sources and How To Use This Book.

Sooner or later, you are almost certain to encounter Nonconformists in your family tree. North Staffordshire had a strong Nonconformist tradition. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists (also known as Independents) all flourished. Methodism was particularly strong: John Wesley visited the area frequently and the region even spawned its own sub-branch of Methodism, called Primitive Methodism, in the early 1800s, and members were known for their huge open air meetings.

But the circumstances of the time mean there may be problems in tracing our Nonconformist ancestors. Firstly, the persecution experienced by many dissenters (a term that includes also Roman Catholics), particularly during the second half of the seventeenth century, gave rise to a reluctance to keep written records. Often a minister would retain the church registers for safe keeping and take them with him when he moved on. The independent nature and lack of a formalized and centralized structure in Nonconformist churches made systematic record keeping difficult to impose. There was considerable variation in the way records were kept, even within the same denomination. Thus, only a fraction of the records have survived and in certain cases not all surviving records have been deposited with the Archive Service.

Most likely there will be pottery industry workers in your tree as well. Given how quickly (in historical terms) businesses come and go, in general it can be difficult to find details of ancestors who worked for private firms. The size and longevity of the main pottery businesses mean that the surviving company records are better than in many other sectors. Documents such as apprenticeship papers, wages and salaries books, and employment contracts can throw light on our ancestors’ working lives. On the other hand, there were so many pottery businesses – many of which were short-lived and never made a name for themselves – that it may not be possible to find occupational details. Similar variation applies in North Staffordshire’s other principal industries – coal mining, iron and steel, and railways – and it is a matter of luck as to what survives.

Migration is another common theme. Like other towns during the Industrial Revolution, the Potteries grew by drawing in workers from elsewhere. So at some stage Stokies are likely to find that their heritage leads back to other areas. Most likely, these ancestors did not move very far, however. Unlike the industrial cities of the North and Midlands, migration in North Staffordshire was highly localized. In 1851, only around 19 per cent of the population of Burslem was born more than 30 miles from the town. This is low by national standards: in some industrial towns only a quarter of the population was native born. Rural Staffordshire, Shropshire, Cheshire and Derbyshire were the most likely locations, as well as movement within the Six Towns. Immigration was also relatively low. Around 10 per cent of the Burslem population was born outside England and Wales in 1851, the majority (8 per cent) being from Ireland.

North Staffordshire is served by a diverse range of archives, several of national and international significance. In common with public archives elsewhere, these face two major, and in some senses interrelated, challenges. On the one hand, there is the shift towards digital access and delivery, while at the same time an increasing strain on archive services in the wake of public sector cutbacks. Several archives are reviewing their service provision, amending opening hours and/or closing certain facilities as a result. For these reasons, no information is given here on aspects such as opening hours or cost of services; you should check each organization’s website for details before visiting. While information about online resources and collections is as up-to-date as possible, this too may be subject to change.

The main archives referred to in this book are listed below. The entries here merely summarize the services available and the main classes of archives held. Further details, including full postal addresses, are provided in Appendix 2 and specific references are made throughout the text.

www.staffordshire.gov.uk/archives

The records and archive service covering the historic county of Staffordshire, which is funded jointly by Staffordshire County Council and the City of Stoke-on-Trent. Archive collections and series relating to North Staffordshire are split between the Stoke-on-Trent City Archives (STCA) at Hanley Library, Stoke-on-Trent, and Staffordshire Record Office (SRO) at Stafford. In addition, the SSA manages the William Salt Library (WSL) in Stafford, a specialist local history library (www.staffordshire.gov.uk/salt). The former Lichfield Record Office (LRO), which was operated by the SSA, has now closed and its collections have been transferred to the SRO. The move is the first stage of a centralization and modernization programme that will see the SRO, LRO and WSL collections brought together under one roof at a new site to be called the Staffordshire History Centre in Stafford.

Stoke-on-Trent City Archives grew out of the Horace Barks Reference Library at the City Central Library, which was named after a former Lord Mayor. Its records include parish registers, poll books and electoral registers, Poor Law records, newspapers and trade directories, and the records of local government, health and education. Its collections relating to the pottery industry are of national and international significance, and include the archives of industry pioneers and major businesses such as Wedgwood, Minton and Spode. The Search Room computers allow free access to commercial and other genealogy websites for library users, as well as a variety of additional resources.

The SSA has published guides to some of its record series, which may be downloaded from its website; these are referenced here individually at appropriate places in the text. As well as the SSA’s own collections, its online catalogue Gateway to the Past, www.archives.staffordshire.gov.uk, covers the archival collections of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery (PMAG), and is explained in greater detail below. Several specialist websites relating to the SSA’s collections are also available:

•Staffordshire Name Indexes (SNI), www.staffsnameindexes.org.uk: A series of online indexes compiled from SSA records. Subjects include apprentices, canal boats, jurors, police officers, prisoners, workhouses and wills.

•Staffordshire Place Guide, www.staffordshire.gov.uk/leisure/archives/history/placeguide: A finding aid for information on Staffordshire parishes. Information is summarized under various headings, with direct links to the online catalogue.

•Staffordshire Past Track, www.staffspasttrack.org.uk: Allows users to explore Staffordshire’s history through photographs, images, maps and documents, using a range of easy to use search tools.

•The Sutherland Collection, www.sutherlandcollection.org.uk: Contains records and papers relating to the estates of the Leveson-Gower family, Dukes of Sutherland.

Other notable collections and sources for North Staffordshire research are:

Keele University, Specialist Collections

www.keele.ac.uk/library/specarc/collections/

The University holds a number of specialist collections relating to individuals, families and organizations associated with North Staffordshire. Among these, the Local Collection comprises around 5,000 books, plus pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals and directories, and publications by the Staffordshire Record Society and Staffordshire Parish Registers Society.

http://midland-ancestors.uk and http://midland-ancestors.shop

Now known as Midland Ancestors, the organization was previously the Birmingham & Midland Society for Genealogy and Heraldry (BMSGH), and is the main family history society (FHS) for researchers with interests in Staffordshire and other Midlands counties. North Staffordshire Family History Group, based in Stoke-on-Trent, is one of several branches affiliated to the Society. Through the indexing and transcription work undertaken by its volunteers, the Society is now a major data provider in its own right. It operates a series of indexes, several of which contain data not available elsewhere. Many datasets are available as downloads or on CDROM. There is also a specialist Midland Ancestors Reference Library in central Birmingham.

www.staffordshire.gov.uk/libraries

Now relocated within the new Castle House Civic Hub, the Library holds genealogical resources and a local history collection relating to the historic borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme.

A collaboration between Staffordshire’s register offices and family history societies to transcribe the original, locally held indexes of births, marriages and deaths back to the start of civil registration in 1837. Has good coverage for North Staffordshire.

Under licence from the SSA, parish registers for Staffordshire are available online in the Staffordshire Collection at Findmypast. Approximately 200 parishes are covered, including all those within North Staffordshire. Coverage comprises entries for baptisms, marriages and burials from the beginning of the registers through to 1900, and includes digitized images of the original registers. In addition, the Staffordshire Collection covers probate records and marriage allegations and bonds (both with digitized images) issued through the Consistory Court of Lichfield, previously held at LRO. Findmypast is available by personal subscription or free of charge at the SSA search rooms and in Staffordshire libraries.

The Staffordshire Record Society (SRS) originated in 1879 as the William Salt Archaeological Society. It publishes books and transcriptions of records on the history of the county under the title Collections for a History of Staffordshire (sometimes abbreviated here to Collections), some of which are of particular relevance to family history.

As well as providing a guide to genealogical records, this book discusses the history of the Potteries and the surrounding area. It is only possible to sketch the region’s rich history in a volume such as this. Thus, the presentations provide snapshots around particular themes rather than exhaustive accounts. The subjects have been chosen in order to better understand how our North Staffordshire ancestors lived and to enable us to interpret the records they left behind.

If you wish to delve further into the Potteries’ fascinating past, a whole variety of sources is available. Staffordshire’s first historian was Dr Robert Plot, keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, who travelled throughout the county before publishing his Natural History of Staffordshire in 1686. It has been reprinted several times since. Antiquarian Walter Chetwyd, who lived at Ingestre Hall near Stafford, wrote a history of Pirehill hundred, which covered Newcastle-under-Lyme and what became the Potteries, in the 1680s. It remained unpublished until the early twentieth century, when it was published by the SRS.

An early publication, part directory and part history, is The Staffordshire Potteries Directory: An Account of the Pottery Manufacture, published in 1802 (available at www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk). The first to attempt a comprehensive account of the area was Simeon Shaw in his book History of the Staffordshire Potteries, published in 1829 (reprinted in 1900). This was followed by John Ward’s The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent, which was first published in 1843 and republished in 1969. Robert Nicholls updated and expanded Ward’s account in his book The History of the City of Stoke-on-Trent & the Borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme, published in 1931.

A mid-twentieth-century perspective is provided in Ernest Warrillow’s A Sociological History of the City of Stoke-on-Trent (1960, republished by Ironmarket, 1977). A more personal history, quoted several times in the text here, is Charles Shaw’s When I Was A Child, an evocative account of growing up in the Potteries in the mid-nineteenth century which is said to have inspired Arnold Bennett’s writings. Digitized versions of many of these early publications can be found online, for example, through the Internet Archive (www.archive.org), Hathi Trust (www.hathitrust.org) and Project Gutenburg (www. gutenberg.org).

In the modern era, John Gilbert Jenkins’s Stoke-on-Trent: Federation and After (Staffordshire County Library, 1985), The Making of the Six Towns by Cameron Hawke-Smith et al. (1985) and Alan Taylor’s Stoke-on-Trent: A History (Phillimore, 2003) are key reading. Also of note is the thought-provoking and beautifully illustrated The Lost City of Stoke-on-Trent by Matthew Rice (Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2010), which surveys the city’s rapidly disappearing industrial heritage. Gateway sources for the specific themes covered are indicated in each chapter.

Each of the Six Towns, as well as some outlying localities, has its own historical account: GENUKI Staffordshire pages provide lists by parish (www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/STS/parishes). Newcastle-under-Lyme is especially well documented. Although it has now ceased trading, Churnet Valley Books for many years published a huge array of local history titles for North Staffordshire, some of which are still available through bookshops.

The Staffordshire History website has links to various organizations and resources for local history across the county, including indexes to the former Staffordshire History Journal which ceased publication in 2013 (www.staffshistory.org.uk). Keele University’s Centre for Local History publishes the specialist journal Staffordshire Studies (www.keele.ac.uk/history/centreforlocalhistory). The Centre is home to the Victoria County History (VCH) of Staffordshire, a long-running project to compile the definitive history of the county: Volume 8 covers the Potteries and Newcastle-under-Lyme and can be read for free online (www.british-history. ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol8). Midland History is an academic journal, available on subscription, but certain articles are free to download (search at www.maneyonline.com). The History West Midlands website publishes popular history articles by the region’s leading historians (www.historywm.com).

Steve Birks’s Potteries.org website is an essential resource for the Potteries historian (www.thepotteries.org). The design is old-school and a logical structure conspicuously lacking but delve in and you will find a cornucopia of interesting material on the history of the area. Local historian Fred Hughes has a regular column in the Sentinel newspaper and blogs about Stoke-on-Trent history (https://fredhughesblog.wordpress.com). Most districts have their own local history society (sometimes more than one); website addresses are given in Appendix 2 or contact the nearest Staffordshire community library.

The Six Towns Collection, the local studies collection at the STCA in the City Central Library, Hanley contains books, reports, pamphlets and other items relating to the city. Key items from this collection are on the open shelves in the STCA Search Room, with early books and many pamphlets held in store.

This book aims to provide a comprehensive guide to genealogy resources for tracing your family history within the Potteries and the surrounding area. It is not intended as a general ‘how-to’ guide. The reader is assumed to be familiar with the basic approaches and processes for genealogical research: the main focus here is how to further and apply this knowledge within the specific context of North Staffordshire. For the beginner, there are numerous excellent guides and tutorials that will help you to get started. Who Do You Think You Are?: Encyclopedia of Genealogy by Nick Barratt (HarperCollins, 2008), Tracing Your Ancestors by Simon Fowler (Pen & Sword, 2011) and Tracing Your Ancestors from 1066 to 1837 by Jonathan Oates (Pen & Sword, 2012) all provide useful introductions. Periodicals such as Family Tree and Who Do You Think You Are? magazine have ‘getting started’ guides (www.family-tree.co.uk/how-to-guides and www.whodoyouthinkyouare magazine.com).

The Gateway to the Past website is the online catalogue of Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent Archives.

Many general sources, such as censuses, parish registers, and civil registration indexes are now readily available online. While these are addressed, the book also encourages you to go further and deeper, seeking out sources that you may not have considered previously. Only by digging down into the lives of our ancestors will we be able to understand how they lived and worked within the extraordinary place that is the Potteries. Hence, there is, hopefully, something for the beginner and the experienced researcher alike.

Where relevant, references are given to original sources within the catalogues of the archives concerned. Not all of the individual catalogues are online, so if you are unable to locate a reference given in the text it may be necessary to check with the repository directly.

The catalogue referred to most frequently is that of the Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives Service, known as Gateway to the Past, which can be found at the following web address: www.archives.staffordshire.gov.uk. This contains descriptions of the holdings of five organizations managed by the Archives & Museums Service: Staffordshire Record Office (SRO); Stoke-on-Trent City Archives (STCA); William Salt Library, Stafford (WSL); Staffordshire County Museum at Shugborough; and Shire Hall Art Gallery, Stafford. The Gateway to the Past catalogue allows searches to be made in a number of ways, for example, by title, free text, document reference, and for the results to be filtered by various criteria. The references given in this book relate to the DocRefNo (Document reference number) field.

Within the text, original archive references according to this system are given in square brackets [ ]. For example, document reference number [Q/RLv] within the SSA catalogue is ‘Victuallers and Alehousekeepers Recognizances’. In cases where the repository is not mentioned explicitly, the reference will include the archive’s abbreviation. Thus, the above example may also appear as [SRO: Q/RLv] clarifying that this record series is held at Staffordshire Record Office rather than at any of the SSA’s other sites. The referencing is highly sensitive and spaces are required within the reference codes where given in the text.

Computers are meant to make our lives easier but as we know this is not always the case. The Gateway to the Past catalogue is a fine example. It can be difficult to use, crashes frequently and searches often fail to retrieve the relevant information even though the entries are in the catalogue. An alternative means of searching, which is often more successful, is to access via The National Archives (TNA) Discovery catalogue which links to archive databases across the country (http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/). In compiling this book, Discovery was regularly able to identify records held by the SSA that its own catalogue was unable to retrieve. To use this method, select Discovery’s ‘Advanced Search’ option, then click ‘Search other archives’ and type ‘Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives’ or one of its sub-divisions (SRO, STCA, WSL, etc.). Then enter document references or other search terms in the main search fields. If you wish, the results can be downloaded as a spreadsheet for easier viewing.

Website addresses generally appear in the text in conventional brackets ( ) and in bold, e.g. (www.staffspasttrack.org.uk). For the sake of brevity, only addresses that are referenced once (or on a few occasions) are written in full. General sources, such as main repositories and commercial websites, are given in the lists above and in the Directory in Appendix 2.