Excavations indicate that coal and ironstone have been mined in North Staffordshire since Roman times. Medieval documents point to mining at Tunstall in 1282, Shelton in 1297 and Keele in 1333, and by 1467 surface coal was being mined and used for firing pottery. Visiting the area in 1686, Robert Plot wrote of coal being gained by ‘footrails’, meaning a sloping tunnel driven into the hillside to follow the coal seam. Some coal was mined in ‘bell pits’, a series of adjacent pits which in section looked like a bell. These early mines supplied diverse industries such as small metal-based trades, breweries, the Cheshire salt industry, glass making and tile making.

Large-scale mining began to take off from about 1750, driven primarily by the growth in the pottery industry, the switch from charcoal to coal in the iron industry and the improved road and canal systems. Innovations such as the steam engine allowed mines to be pumped clear of flood water and coal to be extracted from deeper underground. Previously drainage had depended on gutters being cut and this technique was still being relied upon as late as the 1820s. By 1830 mechanization allowed a depth of 2,000ft to be reached at Apedale Colliery, accessed by an inclined plan and a shaft of some 720ft. The North Staffordshire coal industry began to flourish, with areas such as Silverdale and Tunstall becoming hotbeds of mining activity. At the peak of the industry around 1900 there were about ninety collieries within the North Staffordshire coalfield.

In the late eighteenth century pottery manufacturers had begun to join together to form companies to mine coal for their mutual benefit. One at Fenton Park Colliery was typical, in which the principal partners included Josiah Spode II, Thomas Wolfe and Thomas Minton. The local aristocracy and gentry also played a crucial role. Earl Gower risked his fortune by investing in the canal networks and in mineral extraction. He was one of the main investors in the Trent & Mersey Canal and brother-in-law to the Duke of Bridgewater (who most likely introduced him to James Brindley). In 1833 his son, then 2nd Marquis of Stafford, became the 1st Duke of Sutherland, a family name that would be synonymous with the success of Stoke-on-Trent during the nineteenth century.

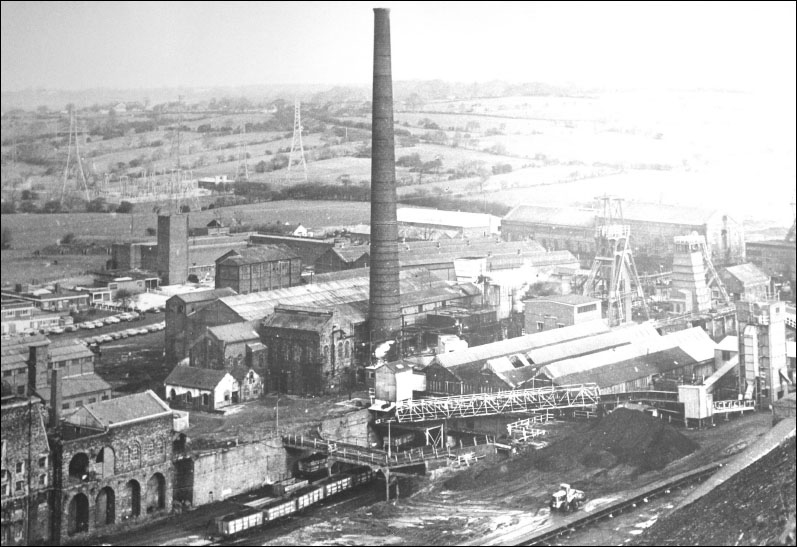

The Chatterley Whitfield Colliery, c. 1930. (Public domain)

Ironstone was being mined at Meir Heath by 1679 and later a furnace was established there. Longton, too, had several ironworks during this period. William Sparrow mined ironstone at Lane End having acquired mineral rights from the Duke of Sutherland. By 1829 his forge was producing more than 1,300 tons of iron a year, mainly for the South Staffordshire nail-making industry. Many such forges were located beside canals since this was the only convenient way of transporting such a heavy product.

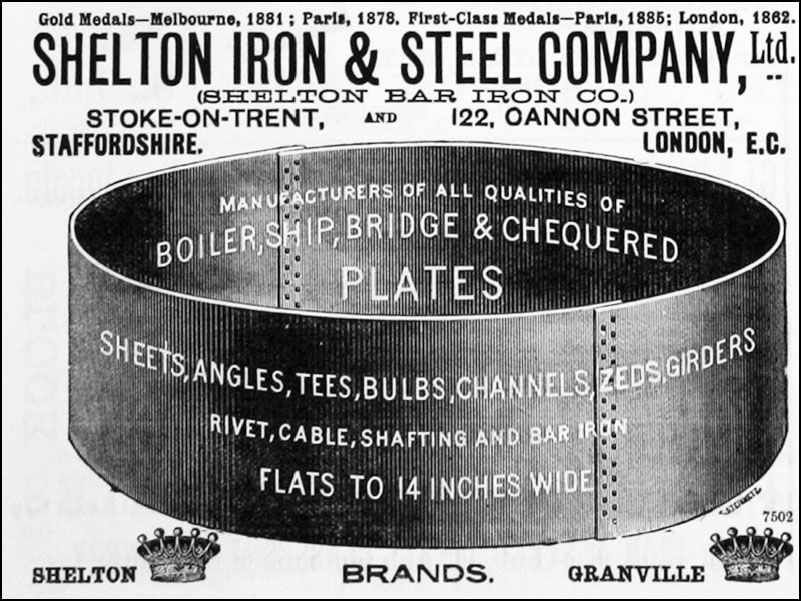

The long recession that ensued in the iron industry following the end of the Napoleonic Wars was eventually reversed in the 1830s with the introduction of the blast furnace. In 1850 Lord Granville (the 5th Earl) established a new works alongside the canal at Etruria, the Shelton Bar Iron Company. Its voracious furnaces were served by a large ring of local pits which included Slippery Lane, Racecourse and Hanley Deep. The Shelton Bar Company went from strength to strength, winning awards at several international exhibitions. By 1888 over 3,000 people were employed at the site and the company continued to expand into the early twentieth century. Apedale and Silverdale also saw the development of large-scale iron and steel works.

This prosperity came at a price, however. Apart from the squalid working conditions (a characteristic of many industries at the time) there was the environmental cost. Mining created huge spoil heaps, known as rucks, which only added to those produced by the pottery industry (‘shard rucks’). In some collieries the waste slack accounted for as much as 75 per cent of the extracted material. Despite the risks, the heaps became favourite playgrounds for generations of Potteries children.

With few controls and constant pressures to maintain productivity, mines offered an extremely dangerous working environment. Flooding, roof collapses and explosions were all commonplace and those working in the mines were constantly aware of the dangers. In July 1860 an accident with a cage led to the deaths of five men at Adderley Green Colliery near Longton, and at Mossfield Colliery in 1889 a massive gas explosion claimed the lives of sixty-four miners. Even worse was to follow at Diglake Colliery, Audley, in January 1895 when a vast underground reservoir of water broke into the workings and threatened the lives of 240 men and boys. In the ensuing horror there were some miraculous escapes, but 77 lives were lost.

The situation improved only gradually. Despite early efforts, including the appointment of inspectors in coal mines, in 1870 over 1,000 lives were still being lost across the country each year in mining accidents. In 1872 the Coal Mines Regulation Act introduced the requirement for pit managers to have state certification of their training. Miners were also given the right to appoint inspectors from among themselves. The Mines Regulation Act, passed in 1881, empowered the Home Secretary to hold inquiries into the causes of mine accidents. It remained clear, however, that there were many aspects of mining that required further intervention and regulation. Casewell (2015) is an index of mining deaths in North Staffordshire 1756–1995: it lists around 4,450 deaths based on newspapers, official reports and burial records. Leigh (1993) describes the history of the North Staffordshire Mines Rescue Service and operations with which it was involved.

Matters were not much safer for those above ground either. With miles of underground workings criss-crossing the Six Towns subsidence was widespread. For example, by comparing historic maps and later photographs it has been shown that Wedgwood’s Etruria factory sunk by about 2.5m. As early as 1844 a Mr Hilton of Union Street, Shelton brought an action for compensation against Lord Granville. By then more than 60 houses in Hanley and Shelton had been damaged by subsidence and over 160 rendered uninhabitable. Hilton’s was a test case brought to scrutinize the accountability of Granville and his agents and the right of local copyholders to be compensated. While admitting that his works had caused the damage, Granville claimed that custom gave him a right to work the mines, without control, as near to the surface as he needed and without giving compensation. The case went on for several years and no compensation was paid.

The pivotal point for coal and steel in the Potteries came in the post-war period. In the steel industry, constant swapping between private and public ownership, combined with chronic under-investment, led to prolonged decline. In the 1960s competition from abroad forced the then British Steel Company to focus on sites with deep-water wharves able to handle huge quantities of imported raw materials. Land-locked Shelton was retained as an experimental facility for a while but finally closed in 1978. The rolling mill was kept on, producing 400,000 tonnes per year, until it too ceased production in 2000.

With many small collieries, deep mining too began to feel the pressure of international competition. Mine closures began in the 1960s with the closure of collieries such as Hanley Deep and Apedale. In the following decades there were many more, although the most productive, including Silverdale, continued to receive new investment. Despite producing over 1 million tonnes annually at its peak, eventually Silverdale too was considered uncompetitive: it closed in 1998, the last deep mine in North Staffordshire. Edwards (1998) and Stone (2007) present historical accounts of Staffordshire’s collieries and coalminers, while Deakin (2004) provides a photographic record of most of the pits that were operating at the time of nationalization in 1947.

The area’s coal mining heritage can be seen at Chatterley Whitfield Colliery, which is acknowledged to be the most comprehensive surviving deep mine site in Britain. Once operated as a commercial museum, it is now run as a charity and accessible on selected open days only (http://chatterleywhitfieldfriends.org.uk). The Northern Mine Research Society is dedicated to the preservation and recording of the mining history of the north of England and has various publications and resources (www.nmrs.org.uk). A useful resource for mines research, the Coal Mining History Resource Centre is no longer maintained but is still available via online archives (https://archive.is/www.cmhrc. co.uk).

Advertisement for the Shelton Iron & Steel Company, 1889. ‘Granville’ was one of its brands. (Public domain)

SSA Guide No. 6 Colliery Records summarizes holdings on collieries within the county. The records of the industry include the pre-1947 colliery company records, sporadic records of individual collieries and the divisional and area records of the nationalized industry after 1947. All of the series may need to be searched for material on individual pits. More general sources such as Ordnance Survey maps, local newspapers, tithe and estate maps, and trade directories may also be useful. Family members may be mentioned in materials relating to mining accidents, such as the Audley (Diglake) Colliery Disaster Fund [STCA: D021 and SD 1023].

The Peak District Mines Historical Society has reproduced lists of mines in Staffordshire from a 1896 publication; it lists both coal (http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/mhn/1896-C1.htm) and metalliferous mines (http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/mhn/1896-C4.htm). The records of the MacGowan Company contain many photographs, maps, plans and manuscripts relating to mining in the area, including the Transactions of the North Staffordshire Institute of Mining & Mechanical Engineers, 1875–1891: see the handlist in the STCA Search Room [SD 1090].

Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives has a limited collection of trades-union records from the Midland Miners Federation [SRO: D4554] and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) [SRO: D4701], including photograph albums of NUM Area Galas from the 1950s [D4554/A/4]. Further records from the NUM Midlands Area: Staffordshire District, 1891–1971 are held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick. Staffordshire University Special Collections has original records from Hem Heath and Silverdale collieries and some National Coal Board records.

A one-time employee of the Chatterley Whitfield Collieries Ltd, William Jack photographed and also collected photographs of North Staffordshire collieries, railways and mineral workings. This collection, now housed at Keele University, comprises typescripts of Jack’s own contributions to North Staffordshire railway and mining history, as well as scrapbooks and minute books of the Chatterley Whitfield Colliery dating from the 1870s to 1926.

If your ancestor was a mine owner or manager, they may turn up in the records of the North Staffordshire Coal Owners Defence Association, North Staffordshire Colliery Owners Association or the North Staffordshire Iron Masters Association, all of which are held at Staffordshire Record Office.

The blossoming of the pottery industry in North Staffordshire is intimately bound up with the growth of canals. Pottery manufacture is a resource-intensive process requiring huge quantities of bulky raw materials, principally clay and coal. The finished products are extremely fragile and so not amenable to long distance transport by horse and cart on unpaved roads. As they expanded their operations, early manufacturers such as Josiah Wedgwood complained that even the short packhorse journey between the potbanks and the nearest navigable rivers resulted in too many breakages, was too costly and took too long.

Although sitting on the Trent, at Stoke the river was too shallow to navigate. The nearest points of access to natural waterways were Winsford in Cheshire, on the River Mersey (leading to Liverpool), and Willington in Derbyshire, on the River Trent (leading to the North Sea). In fact, the Potteries lie on high ground close to the east–west watershed between these two basins. Breaching this watershed by a canal was seen as bringing opportunities to exploit trade routes in either direction.

Schemes to link the Trent and Mersey had been discussed as early as 1717 but surveying work did not begin in earnest until 1758. A pamphlet of 1765 explained the vital importance of such a scheme to the future of the industry. Noting that finished wares had to be transported up to 30 miles to a navigable watercourse, it continued:

The burden of so expensive a land carriage to Winsford and Willington, and the uncertainty of the navigations from those places to Frodsham in Cheshire and Wilden in Derbyshire, occasioned by the floods in winter and the numerous shallows in summer, are more than these low priced manufactures can bear; and without some such relief as this under construction, must concur, with their new established competitors in France, and our American colonies, to bring these potteries to a speedy decay and ruin.

Plan of the Trent & Mersey ‘Grand Trunk’ Canal showing connections to the north and south. (Victoria County History)

The grand idea was to link the Trent, Mersey, Severn and Thames rivers with a system of canals, and the Potteries would be one of the first to benefit. The success of the enterprise was down to two men: Josiah Wedgwood, who secured the patronage and goodwill of the large landowners and politicians; and James Brindley, who masterminded the engineering.

Brindley was born near Chapel-en-le-Frith and set up his own mill in Leek before moving north to tackle an engineering problem at a colliery in Lancashire. His ingenious work brought him to the attention of the Duke of Bridgewater who employed him to build a canal to transport coal from his collieries to Manchester. Wedgwood and his fellow entrepreneurs, who included Earl Gower and John Sneyd, commissioned Brindley to build the Trent & Mersey Canal. An Act of Parliament authorizing its construction was passed in 1766 and Wedgwood himself cut the first sod.

It was clear from the outset that the main obstacle to success would be the Harecastle Tunnel between Kidsgrove and Tunstall. The technical feat of cutting a tunnel of 2,880yd through sandstones and coal deposits was unprecedented at the time. During construction of the tunnel many fossils were discovered which were a great source of puzzlement to Wedgwood. ‘These wonderful works of nature’ were, he said, ‘too vast for my narrow microscopic comprehension.’

The canal was completed in eleven years, opening in 1777, though parts were in use long before. At the time the Harecastle Tunnel was described as the eighth wonder of the world. Brindley did not live to see the fulfilment of his project: he contracted pneumonia while out surveying and died in 1772.

Navigable waterways brought huge benefits to the area. Transport costs dropped dramatically, from 10d. to 1½d. per ton per mile. Yet between 1774 (before the whole stretch was opened) and the arrival of the railway in 1848, the total canal tolls collected increased four-fold.

Wedgwood’s Etruria Works was the first of many new factories to be built along the line of the waterway. Gateways to the canal at Longport, Middleport and Newport all became important manufacturing districts. The original subscribers to the Canal Company received an impressive return for their investment. The benefits were felt in the wider community too. A visitor in 1788 noted that: ‘the value of manufactures arises in the most unthought of places; new buildings and new streets spring up in many parts of Staffordshire where it passes; the poor no longer starving on the bread of poverty; and the rich grow greatly richer’.

Further canals and tunnels were soon needed. The Caldon Canal linked the Churnet Valley to the Potteries and included a feeder reservoir known as Rudyard Lake. The Harecastle Tunnel became a bottleneck and in 1827 a second tunnel was built by another master engineer, Thomas Telford. At 2,926yd, Telford’s tunnel was longer than Brindley’s. It also had a towpath so that horses could be used, rather than having to rely on bargees to walk their heavily laden boats through by lying on their backs (known as ‘legging’).

Although the main purpose of the canals was to link the manufactories with their markets at home and abroad, they also allowed the inflow of raw materials. A canal connection to Newcastle in 1795 provided a direct link to the main source of coal, while other links facilitated the flow of ground flint and stone from corn mills that had been converted to serve the pottery industry.

Dean (1997) maps all of the waterways of the Potteries, showing opening dates and key features, while Davies (2006) records the memories of the last of the boat people who worked the Midlands canals from the 1930s to the 1960s.

The canal age has left a huge legacy of records and archives. The National Archives holds the bulk of the surviving canal company records: minute books, wage books, correspondence, deeds of partnership, bankruptcy orders, canal share certificates and shareholders’ registers, prospectuses, pamphlets, accounts, maps, deposited plans, photographs and surveys, etc. Canal records are archived with docks, road and railway records in addition to many other categories. Relevant authorities include the Board of Trade, Ministry of Transport and the British Waterways Board and its predecessors. TNA Research Guide Domestic Records Information 83 (Canals) gives an overview of the many types of record available. See also Wilkes (2011) and the checklist compiled by the London Canal Museum (www.canalmuseum.org.uk/collection/family-history.htm).

Barges and bottle ovens: pottery manufacturers were heavily reliant on the canals. (Public domain)

The SSA has important collections relating to canals within Staffordshire. SSA Guide to Sources No. 8: Transport Records summarizes the holdings, which are of three main types:

1.Records of the Canal Companies: These cover the initial planning and construction of the canals and their subsequent operation, and may include employee records. They comprise plans, maps, letter books, correspondence (for example, negotiations between canal and railway companies) and other records.

2.Canal Boat Registers and Inspection Reports: An Act of 1795 required vessels using navigable rivers and canals to register with the local Clerk of the Peace; the legislation seems only to have lasted a few years. Where they survive, registers of vessels and applications to register vessels under the Act are found in the Quarter Sessions records. Registers may be consulted at the SRO [Q/Rub/1] with an online index at www.staffsnameindexes.org.uk.

3.Miscellaneous Documents and Correspondence: Documents from non-official sources relating to the canal era, such as letters, diaries, newspaper cuttings, etc.

Cheshire Archives and Local Studies has certificates issued by the Stoke-upon-Trent Registration Authority for canal boats owned by the North Staffordshire Railway Co., 1879–90 [LNW/36]. The Basil Jeuda Collection contains more general material on the NSR’s involvement in canals (see below) [SD 1653].

Prosecutions under the Canal Acts will appear in the Quarter Sessions records. The Staffordshire Quarter Sessions, for example, has a number of convictions of boatmen for wasting water from locks, allowing a boat to hit lock gates and so on. Depositions (witness statements) may have names of canal workers or boatmen if they were accused of theft or other crimes.

Canal people lived an itinerant life: they could have been born, married and buried in three different counties and their children born in yet another. Therefore you may need to search for them across a wide area. Often the boat families made connections to Nonconformist churches such as Primitive Methodists and Salvation Army.

The Waterways Archive at the National Waterways Museum in Ellesmere Port is the national archive for the canal network. Its collections include boat registers, toll and tonnage records, and photographic collections covering canal life. Coverage for the Trent & Mersey Canal is patchy, however. More useful are its indexed transcripts of boat registers (from late nineteenth century) for the Cheshire canals (Chester, Nantwich, Northwich and Runcorn) and those in the West Midlands as far as Gloucester, all of which would have been used by Staffordshire boatmen (http://collections.canalrivertrust.org.uk).

Longport railway station in the early 1960s. (Trevor Ford, courtesy of thepotteries.org)

The Railway Mania of the early 1840s left the Potteries without a railway, although the surrounding towns of Stafford, Crewe, Derby and Macclesfield were all connected to the railway system. The nearest access to the growing national network was at Whitmore, on the Grand Junction Railway (GJR) from Birmingham to Manchester via Stafford and Crewe, which opened on 4 July 1837.

Various schemes were put forward that were eventually amalgamated into a combined proposal with two main lines. The Pottery Line would run from Congleton to Colwich, providing connections with the Manchester & Birmingham Railway and GJR respectively. It was promoted as ‘giving the most ample accommodation to the towns of Tunstall, Burslem, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton, Longton and Stone’. A second route, the Churnet Line, was to run from Macclesfield through Leek, Cheadle and Uttoxeter to join the Midland Railway between Burton-upon-Trent and Derby, thus forming a direct link between Manchester and Derby. A third route from Harecastle to Liverpool had to be abandoned in the face of fierce opposition from the Grand Junction Railway. The only section to be built was the short branch from Harecastle to Sandbach, where it connected into the London & North Western Railway.

The North Staffordshire Railway Company was formed to push forward the proposals, which received parliamentary approval in June 1846. Construction work began three months later with John Lewis Ricardo, Member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent and chairman of the NSR Company cutting the first sod.

Known locally as ‘The Knotty’, the North Staffordshire Railway officially opened to passengers on 17 April 1848, with trains running from a temporary station at Whieldon Grove, Stoke, to Norton Bridge. By 1849 more than 113 miles of track had been laid in North Staffordshire, along with stations, warehouses and sidings. At the heart of the NSR’s little empire was Stoke station, in Winton Square, widely acknowledged as one of the finest examples of Victorian architecture in Staffordshire. Serving also as the headquarters of the NSR Company, the building was designed by H.A. Hunt of London and opened in 1848.

At the turn of the century, the still-independent NSR was enjoying a boom, both in passengers and tons of freight carried. An example was the first-rate service on the Loop Line which ran from Tunstall via Burslem, Cobridge, Hanley, and Etruria to Stoke, continuing along the Derby line to Fenton, Longton and finally to Normacot. It boasted an each-way daily service of fifty trains, running at 15-minute intervals during peak periods.

Serving a relatively small population and being surrounded by larger railways, the NSR was always on a precarious financial footing. Having resisted takeover bids since the 1850s, the decline in railways after the First World War meant ‘The Knotty’ could hold out no longer. In 1923 the NSR was absorbed by the powerful London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company and the name disappeared from the network. Later, like communities across Britain, the area suffered heavily from the Beeching cuts of the 1960s.

Jeuda (1986) is an illustrated guide to the NSR from its creation through to 1923 using photographs from the company’s official archive. The Churnet Valley Railway is a heritage railway that operates steam trains along a part of the NSR’s former Churnet Valley Line.

TNA holds the records of many of the railway companies that existed prior to nationalization in 1947; these are catalogued in the TNA Class RAIL. Many are employment related, including staff registers (the commonest type), station transfers, pension and accident records (which may include date of death), apprentice records (which may include father’s name), caution books and memos. The main series, more than 2 million records in total, is available on Ancestry (search for ‘UK Railway Employment Records, 1833–1963’]. Stoke-on-Trent City Archives has NSR employee records, c. 1898–1950 but it is not clear how these relate to the Ancestry series [SD 1184]. For further information on railway staff records see specialist guides: Hawkings (2008), Hardy (2009) and Drummond (2010).

The SSA has an extensive collection relating to the NSR, much of which is uncatalogued. It includes property deeds, legal papers, maps, timetables and prospectuses and is filed under numerous catalogue references. The Basil Jeuda Collection contains material relating to the NSR throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including the company’s master photographic archive [SD 1288, SD 1416, SD 1688, SD 1698 and D1415, uncatalogued]. The Jack Hollick Collection [Hollick] and Lancefield-Walker Collection [SD 1319, SD 1419] also relate to the NSR. Little of this archive relates to employees, however. The holdings are summarized in SSA Guide to Sources No. 8: Transport Records. Midland Ancestors has the Wages Ledger, 1850–1930 of the NSR’s Canals Department available as a download [BR0001D].

NSR employees may also have worked for the Midland Railway Company, which operated trains in and through the Peak District. The Midland Railway Study Centre in Derby is a specialist archive relating to this company assembled from various collections. The website has a staff index and online catalogue (www.midlandrailwaystudycentre. org.uk).

Inquisitions and assessments for compensation for land acquired by railway companies are in Quarter Sessions records. There may also be references in the personal or estate papers of the families concerned. For example, the Sutherland Papers at the SSA contain details of property of the Duke of Sutherland in Trentham and Barlaston affected by the building of the Pottery Line [D593/H/9/67].

The Library of Birmingham has a major collection of railway material, including over 5,000 books and periodicals, timetables (including Bradshaw’s), maps, architectural drawings and plans, and over 20,000 photographs and postcards of locomotives. It also houses the Wingate Bett Transport Ticket Collection, comprising over 1 million tickets from all over the world.

For centuries the people of the Potteries relied on the sparse network of roads left by the Romans. Their main thoroughfare was Rykeneld (or Ryknield) Street linking Chester and Derby. The route is not entirely clear, but it is believed to have run through Chesterton (site of a Roman fort), Wolstanton, Fenton, Lane Delph and Blyth Bridge. During the medieval period it became common practice for potters to dig clay from the roads to use in their wares, leaving ‘potholes’ on the surface. Severe fines for this offence were imposed after 1604 but did little to quell the practice. Many roads were little more than ancient trackways that connected small villages and hamlets and were used primarily for the movement of livestock.

As the pottery industry developed raw materials from outside the locality were brought in by packhorse. Finished vessels were taken out in the same manner but the condition of the roads resulted in many wares being broken. As the volume of raw materials and products increased carts were used instead but often the local roads were impassable. Extra demands imposed by the growing stagecoach traffic (the main route from London to Carlisle ran through the Potteries) only exacerbated the situation. Something had to be done.

In 1762 local industrialists and gentry petitioned Parliament to be allowed to build a turnpike road from the Liverpool and London Road at Lawton to Stoke-upon-Trent. There it would join the Newcastle to Uttoxeter turnpike which had recently been improved. The petitioners drew attention to the increasing demand for their wares which were being ‘exported in vast quantities’ and the obstacle created by the poor condition of the roads:

This road, especially the northern road from Burslem to the Red Bull, is so very narrow, deep, and foundrous, as to be almost impassable for carriages; and in the winter, almost for pack-horses; for which reason, the carriages, with materials and ware, to and from Liverpool, and the salt-works in Cheshire, are obliged to go to Newcastle, and from thence to the Red Bull, which is nine miles and a half . . .

The burghers of Newcastle objected to this proposal since they stood to lose out by the diversion of carriages and travellers. Parliament passed the Act but with an abridgement of the road at its southern end, meaning it terminated at Burslem instead of proceeding onward to Cliff Bank, Stoke. Turnpiking brought great benefits for the local economy and North Staffordshire was soon criss-crossed by a network of turnpike roads, some new, others improvements of existing routes. The Turnpikes.org website has details of routes as well as information on the gates and tollhouses used to collect tolls from road users (www. turnpikes.org.uk).

The records of turnpikes relate mainly to those involved in establishing and managing turnpike trusts, who were generally drawn from the upper classes. Each trust required its own Act of Parliament, which had to be renewed roughly every twenty years. The Act included a list of the trust’s subscribers, who were effectively shareholders investing in the scheme for a commercial return. These ranged from the local aristocracy and gentry, to prominent landowners, farmers and merchants. Once established, each turnpike trust had to issue regular reports on its activities, which were reported at the Quarter Sessions [SRO: Q/Rut]. Fines imposed on stage-coach drivers for various infringements on turnpikes would also be levied there [SRO: Q/RLb].

The limited nature of the road system influenced the development of the Six Towns as a sprawling, linear conurbation. Houses tended to be built along the line of the roads. The owners of the growing potbanks and mines sought to house their workers within easy travelling distance and built on any available spare land.

Creeping urbanization during the nineteenth century brought the need for short-distance transport options. George Train, an exuberant American, opened the first tramway in the Potteries in January 1862. His ‘street railway’ ran from the Town Hall in Burslem to Foundry Street, Hanley, horse-drawn trams running every hour or half-hour at a fare of 3d. The system encountered technical difficulties and was expensive to operate and although the company remained in operation for twenty years, horse-drawn traction never really took off.

A Potteries Motor Traction bus, c. 1960. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

In 1881 an extension from Stoke to Longton was built as a steam tramway and the following year the original horse tramway line was converted to steam traction. A further extension from Stoke station to West End brought the total length of tramway in operation to 7 miles. For a while the service relied on open-top double-decker trailer cars: these were extremely uncomfortable and were soon replaced by more comfortable single-decker units. People complained that the steam trams showered them in dust and ashes, but they were better than ‘Shanks’s Pony’.

The steam trams, too, were short-lived. The British Electric Traction Company Ltd acquired control of the North Staffordshire Tramways Company in 1896 and despite carrying almost 4 million passengers per year, by the end of the century steam traction had disappeared. In its place was a network of electric tramways that was being developed by the British Electric Traction Company’s subsidiary, the Potteries Electric Traction Company Ltd. Having electrified the existing tramways, from 1899 a number of extensions were added, including from Burslem to Goldenhill through Tunstall (part of the so-called Main Line), and up a very steep gradient from Burslem to Smallthorne. With the extension at its southern end from Longton to Meir, the Main Line now ran for almost 11 miles linking all the Potteries towns.

The first two decades of the twentieth century were the high point for trams in Stoke-on-Trent. By 1919 a new sight could be seen on the roads: motor buses. The City Council paid no regard to the number of operators to whom it issued licences and competition for the Potteries Electric Traction Company’s routes became intense. At the height of the craze in 1924, no fewer than eighty-one bus operators were licensed to enter the city. Many of them concentrated on the tramway’s Main Line from Tunstall to Longton, where the easiest pickings were to be found. In the face of such stiff competition and an unsympathetic council, the writing was on the wall for the Potteries Electric Traction Company. The last tram ran in the Potteries on 11 July 1928.

The Potteries Electric Traction Company was reconstituted as the Potteries Motor Traction Company Ltd and focused on regaining market share. The large number of local independent operators remained a problem, however, and after the Second World War the company decided that the best approach was to buy them out. Accordingly, the bus fleet became extremely mixed during the 1950s and reflected the complete lack of standardization. Smith (1977) provides a comprehensive history of the PMT and Cooke (2009) documents the many passenger vehicles that have been used on North Staffordshire’s roads.

A little-known episode in Stoke-on-Trent’s history is that it once had a car manufacturer. The Menley Motor Company was set up in Etruria Road, Basford by John Riley and Clement Mendham in 1920.

Register of Stoke-on-Trent Drivers and Vehicles Licences, 1910–13. (Courtesy of Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent Archives, SA/MT/1)

The company produced a cyclecar with an air-cooled 999cc V-twin engine. Only sixteen of these cyclecars were made before the company went into liquidation that same year.

The Albert Huxley Collection at the STCA comprises material on the Potteries Motor Traction Company, including drivers’ licences, identity cards and ration books from the Second World War [SA/AH/18-29 and 35-37]. Unwin (2011 and 2013) presents histories of commercial haulage companies operating in North Staffordshire during the mid-twentieth century.

An unusual record series is a list of driver and vehicle licences issued in Staffordshire between 1904 and 1960 [STCA: SA/MT]. It covers both cars and motorcycles, with the driver’s name, address and details of any endorsements and is indexed. The drivers’ licences run until November 1930 and the vehicle taxation registers continue into the 1960s.

The tyre companies Michelin and Dunlop were major employers in the Potteries and were especially important during the Second World War. The STCA has the Michelin archive collections, c. 1905–2013 [SD 1680]. Part of this archive, an index to the Michelin UK staff magazine 1936–51, is available on Staffordshire Name Indexes.

Casewell, Mark, Index to Mining Deaths in North Staffordshire 1756–1995 (Audley & District FHS, 2015)

Cooke, John, A Century of North Staffordshire Buses (Horizon Press, 2009)

Davies, Robert, Midlands Canals: Memories of the Canal Carriers (History Press, 2006)

Deakin, Paul, Collieries in the North Staffordshire Coalfield (Landmark Publishing, 2004)

Dean, Richard, Canals of North Staffordshire (Historical Canal Maps) (M&M Baldwin, 1997)

Drummond, Di, Tracing Your Railway Ancestors (Pen & Sword, 2010)

Edwards, Mervyn, Potters in Pits (Churnet Valley Books, 1998)

Hardy, Frank, My Ancestor was a Railway Worker (Society of Genealogists, 2009)

Hawkings, David T., Railway Ancestors: Guide to the Staff Records of the Railway Companies of England and Wales, 1822–1947 (History Press, 2008)

Jeuda, Basil, Memories of the North Staffordshire Railway (Cheshire Libraries, 1986)

Leigh, Fred, Most Valiant of Men: Short History of the North Staffordshire Mines Rescue Service (Churnet Valley Books, 1993)

Smith, Geoffrey K., The Potteries Motor Traction Co. Ltd (Transport Publishing Company, 1977)

Stone, Richard, The Collieries and Coalminers of Staffordshire (Phillimore, 2007)

Unwin, Ros, North Staffordshire Hauliers, Volumes 1 & 2 (Churnet Valley Books, 2011 and 2013).

Wilkes, Sue, Tracing Your Canal Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians (Pen & Sword, 2011)