CHAPTER 29

Syphilis and Congenital Syphilis

George R. Kinghorn and Rasha Omer

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

Syphilis

Definition and nomenclature

Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by the spirochaetal bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. The disease is usually acquired through sexual contact, with the exception of congenital syphilis where the infection occurs through transplacental transmission. Untreated syphilis infection can evolve through several stages, each separated for variable times by periods of latency in which there are no clinical manifestations.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The prevalence of syphilis in a community is determined by the socioeconomic structure of the country concerned, and how that structure functions [1].

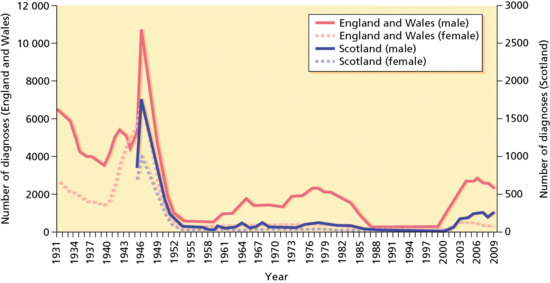

The high incidence of syphilis in World War II peaked as thousands of demobilized men and women returned home to resettle. The period of relative socioeconomic stability of the early 1950s saw a decline in all sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including syphilis (Figure 29.1). Its recrudescence, albeit modest compared with other sexual infections, began in the late 1950s [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Population growth, with a growing proportion of young people in many societies, like increasing population movement, has increased incidence rates more directly.

Figure 29.1 Diagnoses of infectious syphilis made at GUM clinics in England, Scotland and Wales peaked towards the end of World War II, and then fell sharply in the late 1940s. New diagnoses among men rose steadily throughout the 1960s and 1970s, while cases among women remained low. Diagnoses in men declined in the early to mid-1980s, coinciding with an emerging awareness of HIV and the adoption of safer sex practices. Since 2000, there has been a sevenfold increase in syphilis diagnoses among men and a twofold increase among women in England and Wales. Equivalent Scottish data are not available prior to 1945. Northern Ireland data from 1931 to 2003 are incomplete and have therefore been excluded. Data are based on GUM clinic returns. (Data from GUMCAD Public Health England, http://www.hpa.org.uk/gumcad.

© Crown copyright. Reproduced with permission of Public Health England.)

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates in 2008 there were about 36.4 million adults between the ages of 15 and 49 years who were living with syphilis, with an annual global incidence of about 10.6 million cases. Most infections occur in developing countries where the disease has remained a prominent cause of genital ulcer disease in heterosexual men and women, and cause of stillbirth and neonatal morbidity and mortality [3].

The highest rates of infection were reported from the WHO African region with an incidence of 8.5 and 9.4 cases per 1000 and a prevalence of 3.5% and 3.9% for females and males, respectively. Slightly lower prevalence was reported from Latin America and South-East Asia (1.3–1.5 %) and the eastern Mediterranean region (1.2%) [3]. In China, after near eradication of syphilis following a massive control programme during the 1950s, over the last two decades the country has seen a resurgent syphilis epidemic that is particularly prominent among men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSWs) [10, 11].

Eastern Europe experienced a 50-fold increase in reported syphilis cases between 1990 and 1997, with similar increases in the Ukraine, some central Asian countries and the Baltic States. Neighbouring Scandinavian countries have witnessed an increase in imported cases [12, 13]. In North America and the developed countries of western Europe, syphilis remains a major health problem with increases persisting amongst MSM. Cases among MSM have been characterized by high rates of HIV co-infection and high-risk sexual behaviours.

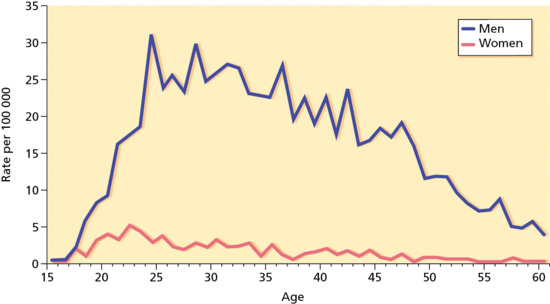

Over the decade 2003 to 2012, diagnoses of infectious syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) made at genito-urinary medicine (GUM) clinics in England increased by 61% (from 1688 to 2713) in men. In contrast, diagnoses in women decreased by 16% (from 317 to 265). In 2012, 2978 cases of infectious syphilis were diagnosed in GUM clinics, 2713 in men (of which 2061 were in MSM) and 265 in women (Figures 29.2 and 29.3) [14]. Countries of western Europe showed a similar trend of syphilis infection, with MSM bearing a disproportionate burden of the infection [15].

Figure 29.2 Diagnoses of infectious syphilis by gender in England, 2003–2012. (Data from GUMCAD Public Health England, http://www.hpa.org.uk/gumcad.

© Crown copyright. Reproduced with permission of Public Health England.)

Figure 29.3 Diagnoses of infectious syphilis by age and gender in England, 2012. (Data from GUMCAD Public Health England, http://www.hpa.org.uk/gumcad.

© Crown copyright. Reproduced with permission of Public Health England.)

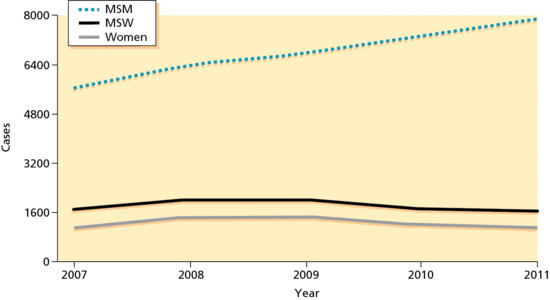

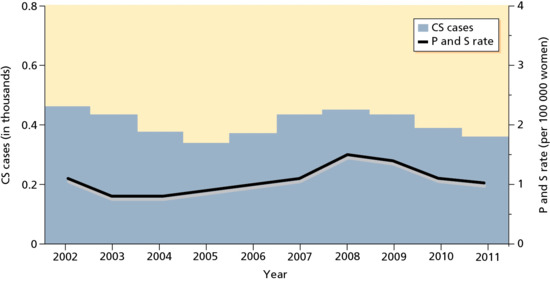

Between 1940, when reporting began, and 1990–2000 the rate declined by 89.7%. The rate in 2011 remained unchanged (Figure 29.4). Overall increases in rates were observed primarily among men. Syphilis remains a major health problem with increases persisting among the MSM group. After persistent declines during 1992–2003, the rate among women increased from 0.8 cases (in 2004) to 1.5 cases (in 2008) per 100 000 population, declining to 1.1 cases per 100 000 population in 2010 and 1.0 cases per 100 000 population in 2011 (Figure 29.5) [16].

Figure 29.4 Reported cases of syphilis by stage of infection in the USA, 1941–2011.

(Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.)

Figure 29.5 Primary and secondary syphilis by sex and sexual behaviour in selected areas of the USA, 2007–2011. MSM, men who have sex with men; MSW, men who have sex with women.

(Courtesy of Central of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.)

Syphilis is not as infectious as some other STIs, and the infected are readily rendered non-infectious by even short courses of antibiotics given for a wide variety of infections – not least for two common STIs, gonorrhoea and non-specific genital infection. However, the growth of penicillin and other antimicrobial resistance amongst gonococci, for example in South-East Asia, but increasingly also in western Europe, and the use of drugs that are less treponemicidal may open the way for a greater prevalence of syphilis [17, 18]. This is happening in a similar manner to the reported azithromycin treatment failures in San Francisco between 2000 and 2004 [19].

Age

Syphilis occurs in sexually active individuals of all ages and is commoner in young adults.

Sex

Although there is marked preponderance of cases in males, this sex difference relates to patterns of sexual behaviour and other social factors rather than to any sex difference in risk of acquisition. It is generally considered that male to female transmission is more efficient.

Ethnicity

The disease occurs in all racial groups.

Associated diseases

Acquired syphilis commonly coexists with other STIs, hence comprehensive screening is advised when syphilis is detected.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Relatively few genes are involved in pathogenesis. It has been postulated that the immunoevasiveness of Treponema pallidum is the result of the organism's unusual molecular architecture. The outer membrane lacks lipopolysaccharide and contains few, poorly immunogenic transmembrane proteins. The highly immunogenic proteins are lipoproteins anchored predominantly to the periplasmic leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane [20, 21]. The T. pallidum repeat protein genes (TPR) occupy 2% of the genome and encode for a group of potential virulence factors, which are targets for strong cellular and humoral responses. The TPR-K proteins demonstrate marked antigenic variation [22].

The dominant immunogen is a 47 kDa membrane lipoprotein, which can induce synthesis of tumour necrosis factor α. Immunoblotting has also shown IgG responses to an antigen of 65 kDa that is shared with non-pathogenic treponemes, and antigens of 44.5, 17 and 15.5 kDa that are specific for T. pallidum.

Histopathology

The fundamental pathological changes in syphilis are the same in early and late disease. They occur in and around the blood vessels in the form of a perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells, accompanied by intimal proliferation in both the arteries and veins (endarteritis obliterans).

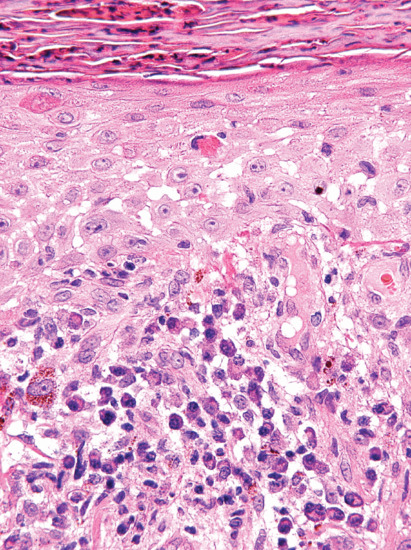

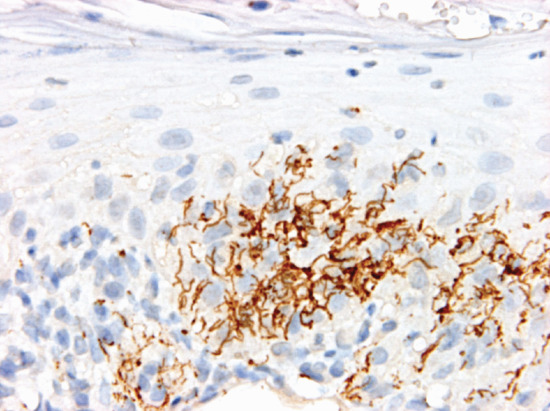

In early lesions, perivascular infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells is accompanied by intimal proliferation in the arteries and veins. This leads to ischaemia and ulceration. Organisms are most numerous in the walls of the capillaries and lymphatic vessels. They can be demonstrated by Levaditi's silver stain, by the fluorescent antibody technique and more recently in a simpler and quicker way by immunohistochemistry with a monoclonal antibody against the spirochaete [23]. The papular skin lesions of secondary syphilis also show endothelial swelling in dermal vessels. In addition, there is often psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with a multifocal interface change associated with lymphocytes and particularly plasma cells (Figure 29.6). Immunohistochemistry for treponema shows numerous microorganisms, which in secondary syphilis tend to be more prominent within the epidermis (Figure 29.7).

Figure 29.6 Secondary syphilis showing psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with spongiosis and interface change with abundant plasma cells.

Figure 29.7 Secondary syphilis. Immunohistochemistry shows numerous spirochaetes within the epidermis.

In late lesions, the characteristic lesion of mucocutaneous surfaces is the syphilitic gumma. Granulation tissue forms with histiocytes, fibroblasts and epithelioid cells. Endarteritis obliterans and necrotic areas are pronounced. Gummata most often originate in subcutaneous tissues and spread in all directions. Spirochaetes are not readily demonstrable in these lesions.

Heubner arteritis occurs in cardiovascular and meningovascular syphilis. It is characterized by lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of the vasa vasorum and adventitia of large and medium-sized vessels. Occlusion of the vasa vasorum results in medial necrosis and fibroblast proliferation. There is associated subintimal proliferation, which leads to luminal occlusion and thrombosis.

Causative organisms

The causative spirochaete of syphilis, Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, was discovered by Schaudinn and Hoffmann in 1905 and originally was called Spirochaeta pallidum.

T. pallidum cannot be grown in the laboratory on any biochemical medium. Not all animals are susceptible to it. The rabbit is commonly used in laboratory studies and as a source of the T. pallidum used in diagnostic tests. T. pallidum cannot be differentiated from those treponemes involved in other forms of treponematosis, nor from Nichol's strain, which was isolated in 1912 from the brain of a patient and kept alive by passage through many generations of rabbits. Another experimental treponeme, the Reiter strain, is said to have been isolated in 1922. In contrast with Nichol's strain, it is avirulent and can be cultivated on a relatively simple medium. Freeze-dried extracts were used for many years in the Reiter protein complement fixation test.

Morphology

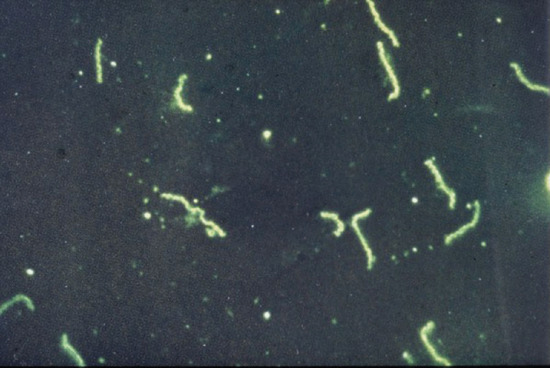

In daily practice, T. pallidum is demonstrated by dark-field microscopy (Figure 29.8). It appears as a pale, white, fine, corkscrew organism with close and very regular coils (Figure 29.9). Its length varies from 6 to 15 μm and its coils from 0.09 to 0.18 μm. There are between eight and 20 coils. As a practical guide, to help differentiate the organism from others like it, there are about seven to eight coils per diameter of a red blood corpuscle. It contains a periplasmic flagellum and is actively motile. The movements of T. pallidum are pathognomonic. It rotates around its long axis and thus appears to quiver and screw slowly backwards and forwards; it shows a highly typical angling movement, forming both acute and obtuse angles. It shows both grace and elegance and these help to distinguish it from other genital or oral spirochaetal organisms. Treponemes can also be demonstrated by the direct fluorescent-antibody method [24, 25], and by rapid immunofluorescent staining (RIS) of smears [26] from lesions (Figure 29.10).

Figure 29.8 Treponema pallidum on dark ground microscopy.

Figure 29.9 Treponema pallidum showing typical morphology.

Figure 29.10 Immunofluorescent image of Treponemal pallidum.

Of the several spirochaetes found in the genital area and requiring differentiation from T. pallidum, the most important are Borrelia refringens and B. balanitidis. Both are thicker than T. pallidum and have fewer and irregular coils. In addition, they move with more fidgety, snake- and eel-like movements. B. gracilis is finer than T. pallidum, with closer coils and a lack of typical movements. It can be found at the gum margins between teeth.

Microbiology

The organism is microaerophilic and has evolved to become a highly invasive and persistent pathogen with little toxigenic activity and an inability to survive outside the mammalian host. It has extreme nutritional requirements due to deficiencies in biosynthetic pathways, and has a narrow equilibrium between oxygen dependence and toxicity. It cannot be cultured on artificial media but it can be propagated in organ culture, such as rabbit testes. It has a slow growth rate, optimal at 33–35°C, with a doubling time of 30–36 h. The organism is similar to, and shares extensive DNA homology with, three other pathogenic treponemes, which cause yaws, bejel and pinta.

Analysis of the genome, which is contained on a single circular chromosome with 1138 kbp, shows that the organism lacks lipopolysaccharide and lipid biosynthesis mechanisms, as well as many metabolic pathways, including, for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, components of oxidative phosphorylation, and for most amino acids and vitamins. It requires D-glucose, maltose and mannose but cannot utilize other sugars [27]. It is able to use exogenously supplied amino acids and is dependent upon serum components such as fatty acids.

T. pallidum initiates an inflammatory response at the site of inoculation and is disseminated during the primary infection. The organism has a surface-associated hyaluronidase enzyme, which may play a role in this process. Phagocytosis by cytokine-activated macrophages, as part of a predominant T-helper 1 (Th1) type early response, aids bacterial clearance and resolution of the primary lesion [28]. Virulent organisms promote the adhesion of lymphocytes and monocytes to human vascular cells, and this is important in immunopathogenesis [29]. As with other organisms that cause chronic disease, T. pallidum has evolved mechanisms for evading immune responses. A Th1–Th2 switch occurs with macrophage suppression caused by prostaglandin E2 down-regulation; however, the molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood [30]. Depressed cell-mediated responses occur during the later stages of syphilis, and a lowered CD4+ lymphocyte count has been reported [31].

Clinical features

Natural history

Stages

The clinical presentation of syphilis is extremely diverse and may occur decades after the initial infection. Syphilis, if untreated, may pass through four stages: primary, secondary, latent and late. The first two stages are contagious. They seldom last more than 2 years and do not exceed 4 years. Latency may last from 5 to 50 years. Only 25–30% of patients present with late, chronic, crippling or fatal manifestations. The frequency of these late manifestations continues to decline, and in many countries they are now rare.

Incubation period

The incubation period of syphilis is generally given as 9–90 days, and varies inversely with the size of the spirochaete inoculum. Typically, most genital primary sores appear 3 weeks after exposure. Enlarged glands appear in one groin after a further week and can usually be detected in both groins 5 weeks after infection. Reactive reaginic serological tests are detectable at 5.5–6 weeks, the macular rash at 8 weeks, papular lesions at 3 months and condylomata at 6 months.

Course of untreated syphilis

Several investigations have helped to elucidate the natural history of untreated syphilis, for example the Oslo study of untreated syphilis [32] and the Tuskegee study [33]. Regarding the first of these, Caesar Boeck believed that no treatment was better than using mercury. He therefore kept some 2000 infectious patients with syphilis in hospital for 1–12 months (average 3–6 months), until all traces of their infection had gone. Gjestland [32] made a follow-up study of 1147 and summarized the findings as follows:

- 24% developed mucocutaneous relapses.

- 11% died of syphilis.

- 16% developed benign late manifestations, usually cutaneous nodules or gummata.

- 10% developed cardiovascular syphilitic lesions.

- 6% developed neurosyphilis.

It would appear therefore that long before the arsenicals and penicillin were introduced at least 60% of people with syphilis lived and died without developing serious symptoms of their infections.

Presentation

Primary syphilis

The primary chancre appears at the site of initial treponemal invasion of the dermis. Initial lesions are papular but rapidly ulcerate. It may occur on any skin or mucous membrane surface and is usually situated on the external genitalia.

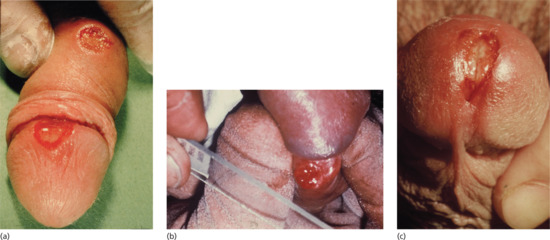

The typical primary sore appears as a regularly edged, regularly based, hard and button-like ulceration measuring up to 1 cm in diameter. Unless secondarily infected, primary sores are not painful. The ulcer is often surrounded by a narrow, red border, 1–2 mm wide (Figure 29.11). This marks the limits of the inflammatory reaction and is most productive of T. pallidum. The lesion may be crusted due to drying of serous exudate. The induration of the ulcer is probably the best known characteristic, but it should be remembered that all lesions in the coronal sulcus of the penis are indurated. ‘Kissing’ ulcers, sometimes hourglass in shape, are not uncommon. About 50% of lesions are atypical and lack one or more of the classic features. If the infection is inoculated into pre-existing lesions such as anal fissures, genital herpes or balanitis, the chancre may assume the shape of these conditions. In most cases, there is only a single chancre. Multiple chancres may appear simultaneously or within a few days of each other. Without treatment, the chancre persists for a period that can vary considerably, but seldom, if ever, exceeds 3 months. As a rule, it heals spontaneously in 3–8 weeks. In about one-third of cases, it leaves a regularly edged, slightly depressed, thin, depigmented, atrophic scar.

Figure 29.11 Penile chancres. (a) Primary syphilis showing chancres on the glans and shaft of the penis. (b) Taking specimens for dark ground microscopy from a penile chancre on the coronal sulcus –. (c) A penile meatal chancre, which may be mistaken for meatitis associated with urethritis.

The appearance of the genital and perianal chancre is followed by swelling of the inguinal lymph nodes, initially unilateral. Maxillary and submental lymph nodes enlarge when infection is in or around the oral cavity. Wherever they appear, the enlarged glands are discrete, rubbery and free from fixation to skin or underlying tissues.

In men, the chancre most usually occurs on the glans penis, near the frenulum or on the underside of the prepuce. Less commonly, the primary lesion appears on the shaft of the penis. If near the hilt, it may be called a ‘condom chancre’. Less common sites are the pubic region or the external urinary meatus where it may masquerade as non-specific urethritis with scanty serous discharge. Lesions are often surrounded by oedema. Subprepucial lesions may be accompanied by some degree of acquired phimosis and in such cases lymphangitis dorsalis penis may occur; it is felt as an indolent ‘string’, some 2 mm in diameter.

In MSM, the anus and rectum may be sites of primary infection (Figure 29.12). Anal lesions may present as an indurated fissure. Pain may be a feature, as may itch and bleeding, especially after defecation. Like genital primary lesions, extragenital sores are accompanied by regional adenitis.

Figure 29.12 Anal lesion in syphilis.

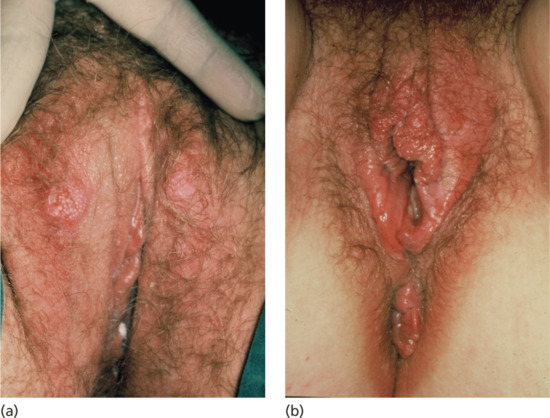

In women, most cases of early syphilis have reached the secondary stage when diagnosed [34]. A chancre is less frequently demonstrated, partly because the primary lesion may be on or in the cervix. The most common sites for a vulvar chancre are the labia minora or majora (Figure 29.13a), around the urethral orifice, on the clitoris or, quite commonly, on the posterior commissure where it may masquerade as an indurated irregular fissure. Surrounding vulval oedema is common (Figure 29.13b). A chancre very rarely occurs on the vaginal wall.

Figure 29.13 (a) Bilateral early chancres of the labia majora. (b) Chancre of the fourchette with surrounding oedema. This patient also had accompanying gonorrhoea, genital Chlamydia and trichomoniasis causing the accompanying vulvo-vaginitis. This illustrates how STIs frequently occur as multiple infections in the same patient.

Extragenital chancres may be found on the lips (Figure 29.14a) as a result of kissing, cunnilingus or fellatio. The indurated ulcer may be surrounded by oedema. Chancres of the tongue and tonsil (Figure 29.14b) and primary lesions of the fingers (Figure 29.15), acquired occupationally or in sexual foreplay, also occur. Other extragenital chancres may follow from nibbling or biting the nipple, ear, neck or arm.

Figure 29.14 (a) Primary chancre of the upper lip showing a typical button-like induration. (b) Primary chancre of the left tonsil.

Figure 29.15 Syphilitic paronychia caused by a primary chancre of the middle finger.

Secondary syphilis

Secondary syphilis is the stage when generalized manifestations occur on the skin and mucous membranes. Serological tests are always positive in immunocompetent persons. Rashes in secondary syphilis have three common features:

- The rashes do not itch.

- The rashes are coppery red.

- The lesions are symmetrically distributed.

The manifestations of generalized treponemal dissemination first appear at around 8 weeks. Constitutional symptoms consist of fever, headache and bone and joint pains that are more pronounced at night. There is wide diversity in physical features although rashes are the commonest feature. They are initially macular and become papular by 3 months. The diverse features of secondary syphilis are discussed in the list below.

- Macular syphilide (roseolar rash) (Figure 29.16). This is the earliest generalized syphilide. It appears as symmetrical, coppery red, round and oval spots of no substance. On the back, the lesions clearly follow the lines of cleavage of the skin. The patients should be examined in daylight as it is easy to overlook an early or fading rash. The roseolar spots do not scale or itch and, being in some patients sparse and evanescent, may pass unnoticed. Roseola is easily overlooked and seldom diagnosed in patients with deeply pigmented skin. When a roseola is fading, it sometimes leaves a pattern of depigmented spots on a hyperpigmented background. Such a leukoderma syphiliticum (Figure 29.17) is most commonly located on the back or sides of the neck and was formerly known as the ‘necklace of Venus’.

-

Papular syphilide (Figure 29.18). The papule is the basic lesion of secondary syphilis. Individual papules seldom exceed 0.5 cm in diameter. Its particular form of presentation can vary widely depending on the nature and colour of the patient's skin, the site affected and the climate, hygiene and clothing. Papular rashes may recur and be punctuated by spells of apparent latency. More usually, early papular rashes are in fact maculopapular and they have an even and generalized distribution all over the body. However, a purely coppery red papular rash, widely and symmetrically distributed, may also be seen.

The typical papule is firm and round, although the largest may be oval. Early papules tend to be shiny, but gradually a thin layer of scale forms and is quickly shed. This is the typical papulosquamous syphilide. Older lesions tend to be more pigmented. In the late phases of a papular syphilide, nummular lesions, 1–3 cm in diameter and covered by massive layers of scales, may closely resemble psoriasis. Because the underlying lesions are exuding serum, the scales are easily removed. Psoriasiform papules of the palms and soles are especially common in black people (Figure 29.19) as are annular and circinate papular rashes. Such rashes may resemble granuloma annulare, annular sarcoid or scaly varieties of tinea.

On macerated skin surfaces and mucous membranes, eroded weeping papules with a tendency to hypertrophy often appear. On the genitals, for example, at the penoscrotal junction, there may be small eroded papules flush with the skin or hypertrophic, coalesced papules (condylomata lata). Such lesions more commonly occur around the anus29.20, groin29.20 and vulva (Figure 29.20a-d). In men, the papules frequently occupy the entire surface of the glans penis, the coronal sulcus and the inner aspect of the prepuce (Figure 29.20e). Partial or complete acquired phimosis is not infrequent in such cases. The free margin of the prepuce may be a circle of tender, fissured (‘split’) papules. In women, in the axillae and beneath the breasts, small, superficial, eroded, lentil-sized (about 0.3 cm) papules are sometimes seen, but more typical are hypertrophic papules, which may affect the adjacent mucous membrane. In the last stages of pregnancy, hypertrophic, coalesced, sodden-surfaced papules may be very pronounced. Later, the papules are more irregularly distributed but show a predilection for certain sites, such as the corners of the mouth (Figure 29.21a), angles of the nose, the palms and soles and body folds such as beneath the breasts or in the axillae. The face is often affected, particularly if the patient has greasy skin. The seborrhoeic areas involved are the same as those involved in acne vulgaris and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Sometimes, the papules form a line along the hair margin, the corona veneris (Figure 29.21a).

Hyperkeratotic lesions of the palms and soles may flake, peel and fissure. Hypertrophic papules between the toes may resemble severe tinea pedis.

Micropapular and miliary eruptions are especially seen late in the second stage, about a year or more after infection. Characteristics of such a lichenoid syphilide include small conical or spinular elements, which tend to be arranged in groups of varying size over the body. A corymbose syphilide is one with a large central papule surrounded by small satellite papules.

- Pustular ulcerative syphilide. This characterized the 16th century epidemic but is now all but unknown. Lesions that most nearly resemble this nowadays are the crusted papule of the scalp where brushing and combing tears papules, which ooze serum and may become secondarily infected. Such lesions, unlike other syphilides, may leave scars. Atypical facial plaques or ulcerated nodules (lues maligna) are more common with coexisting HIV infection [35].

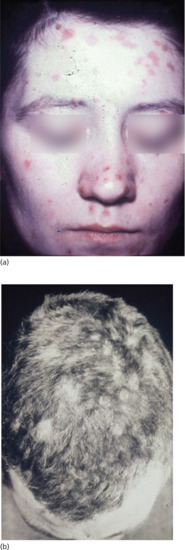

- Syphilitic alopecia. Patchy hair loss is characteristic of syphilis. The hair falls out leaving small, scattered, irregularly thinned, ‘moth-eaten’ patches of semi-baldness (Figure 29.22b). The eyebrows and beard may be affected [36, 37]. Syphilitic alopecia may be accompanied by a more generalized, diffuse alopecia associated with generalized infection and anaemia.

- Nails. Syphilitic paronychia with secondary onychia is sometimes seen in the secondary stage. It has no special characteristics.

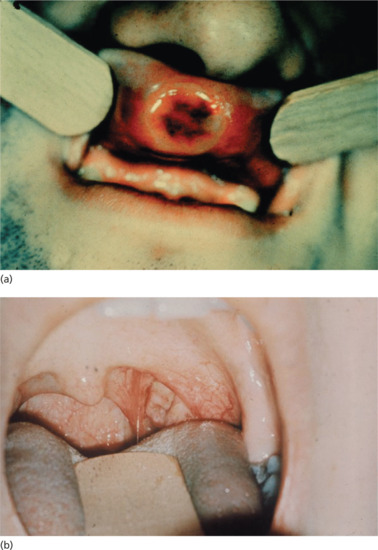

- Lesions of the mucous membranes. On the mucous membranes, the basic papular eruptions are less distinctive, but they tend to be symmetrically distributed. As the surface epithelium dies, it turns grey and forms round or oval mucous patches on the palate or inner aspects of the lips and cheeks (Figure 29.21b). These mucous patches may coalesce to form ‘snail-track’ ulcers although ulceration is not common. Sharply defined, round or oval lesions devoid of dead epithelium may appear on the tongue and may be associated with flattened papillae. Bilateral syphilitic tonsillitis may coexist, as may syphilitic laryngitis associated with eroded papules and hoarseness.

- Generalized lymphadenopathy. This occurs in 50% of secondary syphilis cases. As in the localized lymphadenopathy of primary infection, the nodes are painless, discrete, mobile and rubbery, and vary in size from about 0.5 to 2 cm.

- Neurological involvement. During the secondary stage the central nervous system may be invaded. Abnormalities in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), such as raised cell count and increased protein, can be found in at least 15% of cases [5]. Less often, serological tests are positive in the CSF. The patient may complain of headache only. Occasionally, meningitis may present as paralysis of one or more cranial nerves. Meningomyelitis with paraplegia and double incontinence is rare.

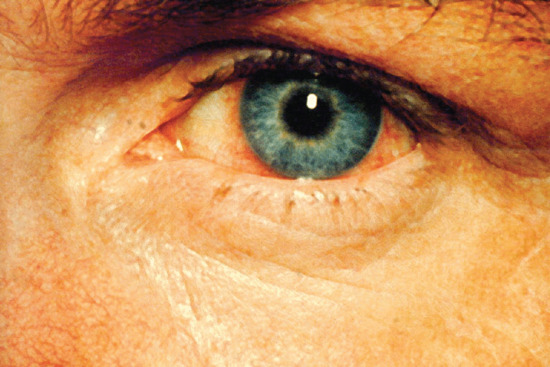

- Other systemic features. Other systemic features of secondary syphilis include panuveitis (Figure 29.23) [38], periostitis and joint effusions, glomerulonephritis, hepatitis, gastritis and myocarditis.

Figure 29.16 Secondary syphilis. (a) Extensive truncal maculopapular rash. (b) Macular rash with lesions following the skin lines of cleavage. (c) Papulosquamous palmar rash. (d) Axillary maculopapular lesions showing a classic coppery colour. (e) Papulosquamous lesions on the sole of the foot.

Figure 29.17 Syphilitic leukoderma showing depigmentation at sites of healed secondary lesions on the neck and upper back.

Figure 29.18 Secondary syphilis showing papular syphilides on (a) the forearms and (b) the trunk.

Figure 29.19 Secondary syphilis showing psoriasiform lesions of the palms.

Figure 29.20 Condylomata lata of secondary syphilis: (a, b) perianal; (c) round the groin; (d) perivulval; (e) on the penile shaft with surrounding depigmentation (with a persistent primary in the coronal sulcus).

Figure 29.21 Oral lesions of secondary syphilis. (a) Split papules at the angle of the mouth. (b) Mucous patches on the buccal mucosa.

Figure 29.22 (a) Papular lesions of the face extending into the hairline. (b) Moth-eaten alopecia in secondary syphilis associated with papular lesions of the scalp.

Figure 29.23 Syphilitic iritis causing circumcorneal injection of the blood vessels.

The lesions of secondary syphilis resolve spontaneously in a variable time period and most patients enter the latency stage within the first year of infection. In some, especially the immunocompromised, primary or secondary lesions may recur.

Latent syphilis

In latent syphilis there are no clinical stigmata of active disease, although disease remains detectable by positive serological tests. In early latency, within 2 years of infection, vertical transmission of infection may still occur, but sexual transmission is less likely in the absence of mucocutaneous lesions. The late manifestations of syphilis subsequently arise, often decades later, in about 25% of those who have latent syphilis.

To establish a diagnosis of latent syphilis, strict criteria are called for. Clinical evidence of active, early, late or congenital syphilis must be absent; the CSF must be normal and a chest X-ray (preferably posteroanterior and left oblique, to view the aorta at a right angle) must also be normal. Positive (reactive) serological tests for syphilis (STS) must be confirmed by examination of a second specimen.

The differential diagnosis may be from biological false positive reactions or from other treponematoses, particularly yaws in immigrants to westernized countries. The presence of a scar of a primary chancre or leukoderma syphiliticum at the back of the neck may be helpful. Yaws is usually acquired by children living in poor rural conditions in the tropics. Presenting in adulthood with positive STS, they may give a history of yaws or chronic sores or bone pains, or they may know of the disease in their family, school or parish. Some have clinical or radiological evidence of old periostitis in their long bones [39]. Much the same may apply to bejel [40].

Great care is called for in assessing immigrant patients. For example, in the UK, one would hesitate to diagnose old yaws in a West Indian immigrant under the age of 60 years. The WHO declared Jamaica free of yaws in 1950, and it has remained free of the disease. On the other hand, yaws has been recrudescing in West African countries for more than 20 years, and the differentiation of latent syphilis from old yaws in immigrants from that part of the world may now present problems.

Tertiary syphilis

After a period of latency of up to 20 years, manifestations of late syphilis can occur. However, screening for syphilis in blood donors and pregnant women has contributed greatly to the prevention of late syphilis. In addition, since the commencement of the antibiotic era, many people with latent and asymptomatic late syphilis have happened to receive penicillin or other treponemicidal antibiotics in circumstances unconnected with syphilis (‘happenstance antibiotic therapy’). Such inadvertent therapy has also contributed to the decline of late syphilis, so that it is becoming rare in many parts of the western world including the UK and USA.

Late skin syphilis appears in two types: the superficial or nodular syphilide and a deeper gummatous syphilide. Transitional forms also occur.

-

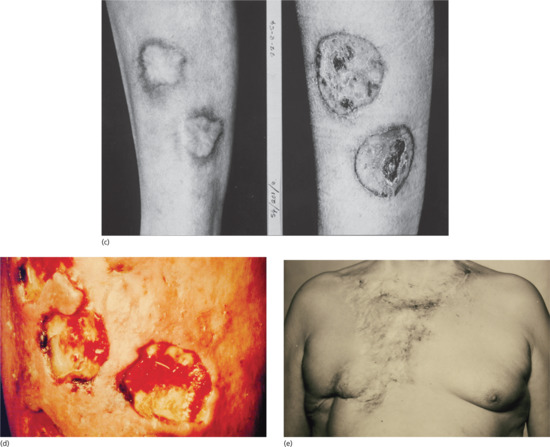

Nodular or tubercular syphilide. The lesions are protruding, firm, coppery red nodules (larger than 0.5 cm diameter) (Figure 29.24a). On dependent limbs, they may be cyanotic. The nodules appear in groups with a tendency to a circinate arrangement – that is, forming interwoven circles and part of circles. As the disease heals centrally, it extends peripherally. The spread does not take place equally in all directions, so that the outline may be horseshoe shaped, tongued, kidney shaped or serpiginous. Some nodular eruptions resemble granuloma annulare or annular forms of sarcoid. Their histology resembles secondary syphilis. In other cases, the abundance of waxy scales gives the eruption a psoriasiform appearance (Figure 29.24b, c). Most frequently, serpiginous nodulo-ulcerative eruptions are covered by massive crusts. Even the smallest ulcers have a punched-out appearance.

Lesions of nodular syphilis can appear anywhere on the body, but favour the extensor surfaces of the arms, back and face. They are symptomless. Where they have spread extensively, smooth, soft, finely wrinkled (‘cigarette paper’) central scarring is a feature. In their early stages, these scars may be pink, but after a year or two they are white. Nodular syphilis spreads slowly but more rapidly than lupus, producing a lesion of similar size in months rather than years.

-

Gummata. The characteristic lesions of tertiary syphilis appear 3–10 years after infection and consist of granulomas or gummata. The granulomas appear as cutaneous plaques or nodules of irregular shape and outline and are often single lesions on the arms, back and face. They have a tendency for central necrosis and ulceration and for peripheral healing with tissue-paper scarring (Figure 29.24d). They most often originate in the subcutis, growing in all directions, into the dermis and epidermis as well as the deeper tissues. Gummata that start in bone or muscle also tend to ulcerate the skin, and their true origin may be difficult to determine. Gummatous changes sometimes take place more superficially with scattered, small ulcerations along the margins. This form is difficult to differentiate from a nodular syphilide.

Gummata are usually painless even when they ulcerate. Their central necrotic tissue may turn into a slimy, stringy mass, and it is this that gives rise to the name ‘gumma’. Multiple gummata tend to coalesce, the bridges of skin between them gradually undergoing necrosis. Such ulcerations offer a wide variety of scalloped and geometrical patterns. A punched-out appearance is characteristic. Gummata vary in size from 2 to 10 cm. They favour the scalp, face, sternoclavicular areas of the chest and lateral calf. Gummata can be extensive, and show healing with tissue paper scarring at their periphery (Figure 29.24e).

Figure 29.24 Skin lesions in tertiary syphilis. (a) Nodular gummata of the arm. (b) Psoriasiform gummata on the neck. (c) Psoriasiform gummata of the leg before (right) and after (left) treatment. (d) Ulcerated gummata on the leg showing wash-leather slough. (e) Extensive gummata of the chest wall showing peripheral healing and scarring.

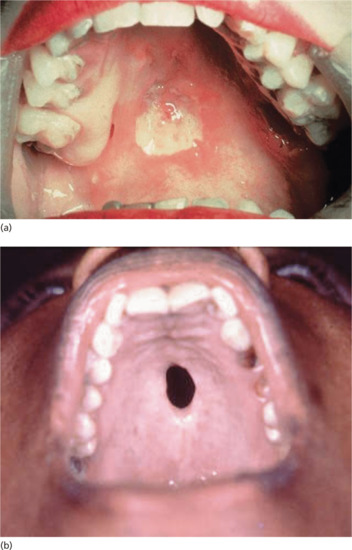

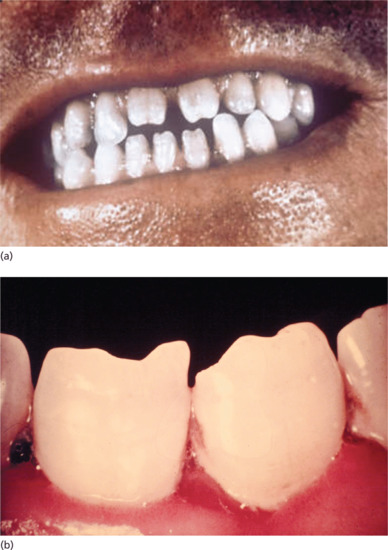

Late mucous membrane lesions not infrequently attack the palate, both the hard and soft, with tissue destruction that may lead to loss of the uvula and scarring or perforation of the hard palate (Figure 29.25). In cases of congenital syphilis, destruction of the nasal septum may also occur, producing a saddle-nose deformity. They may also cause: (i) painless testicular swelling, mimicking a tumour [41]; (ii) portal hypertension and portosystemic anastomoses (Figure 29.26); and (iii) diffuse interstitial glossitis. Late syphilis of the tongue may present with localized or diffuse changes: a solitary gumma or diffuse gummatous infiltration. The latter often passes through a stage of chronic interstitial glossitis with fissuring and, later, obvious leukoplakia with patchy necrosis, sometimes associated with trauma from the teeth (Figure 29.27). In other cases, changes are more superficial, with red, smooth, glazed areas and the loss of papillae. Although sometimes painless, these changes may be accompanied by discomfort on eating hot or acid foods. All the forms of tongue involvement described are recognized as pre-cancerous, so that even after adequate antisyphilitic treatment, regular observation of the patient is an essential element of sound management.

Figure 29.25 Mucosal lesions of tertiary syphilis. (a) Early gumma of the hard palate. (b) Perforated gumma of the hard palate.

Figure 29.26 Visceral lesions of tertiary syphilis. (a) Gumma of the liver causing portal vein obstruction. (b) Portal hypertension with caput medusa caused by hepatic gummata.

Figure 29.27 Chronic interstitial glossitis with bilateral squamous carcinoma.

The serious forms of neurosyphilis such as tabes dorsalis and general paralysis, and cardiovascular syphilis, although detectable earlier, may take 20 or more years to become clinically evident.

The typical lesion of cardiovascular syphilis is aortitis affecting the ascending aorta and appearing 10–30 years after infection. The aortitis may be asymptomatic and detected as dilatation of the ascending aorta on a chest X-ray, often accompanied by linear calcification of the aortic wall (Figure 29.28a), or it may lead to stretching and incompetence of the aortic valve, left ventricular failure or aneurysm formation (Figure 29.28b). Aneurysms may be associated with a variety of syndromes caused by pressure on adjacent structures in the mediastinum, and they may cause sudden death from rupture. Other symptoms include angina pectoris from associated coronary ostial stenosis. Cardiovascular syphilis is more commonly associated with neurosyphilis than with gummatous disease.Neurosyphilis is characterized by a number of heterogeneous syndromes [42, 43]. The differential diagnosis of neurosyphilis covers the whole spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions. The onset can occur weeks or decades after treponemal dissemination.

- Asymptomatic neurosyphilis precedes the development of clinically apparent disease and accounts for one-third of all neurosyphilis. It occurs in 10% of those with latent disease and has a peak incidence at 12–18 months after infection. It reverts spontaneously in 70% of patients.

- Meningeal neurosyphilis usually has its onset during secondary disease and is characterized by symptoms of headache, confusion, nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness and photophobia. There may be focal seizures, aphasia, delirium and papilloedema. Cranial nerve palsies cause unilateral or bilateral facial weakness and sensorineural deafness [44].

- Meningovascular syphilis occurs most frequently between 4 and 7 years after infection. The clinical features of hemiparesis, seizures and aphasia reflect multiple areas of infarction from diffuse arteritis.

- Gummatous neurosyphilis results in features typical of a space-occupying lesion.

- Parenchymatous syphilis appears later and has become rare in its classic forms in the antibiotic era. The peak incidence of general paralysis from parenchymatous disease of the brain used to be 10–20 years after infection. The onset is insidious with subtle deterioration in cognitive function and psychiatric symptoms that mimic those of other mental disorders. As the disease progresses neurological signs develop, including pupillary abnormalities, hypotonia of the face and limbs, intention tremors and hyperreflexia.

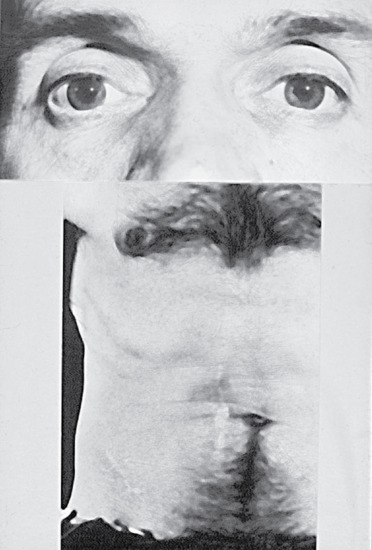

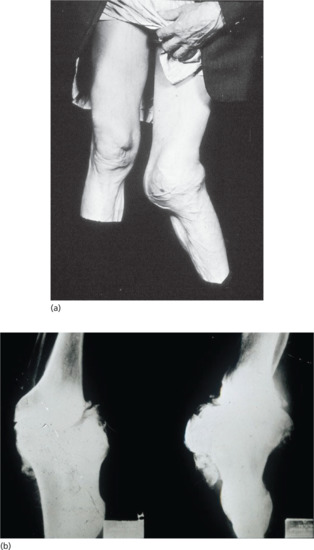

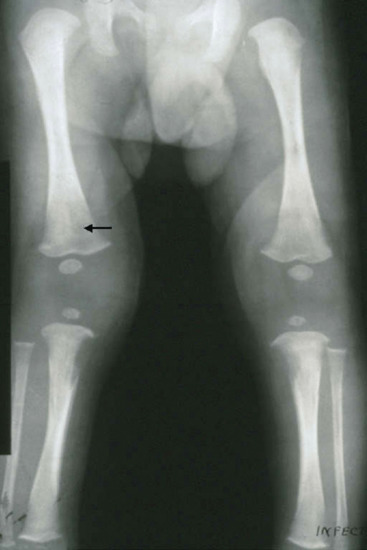

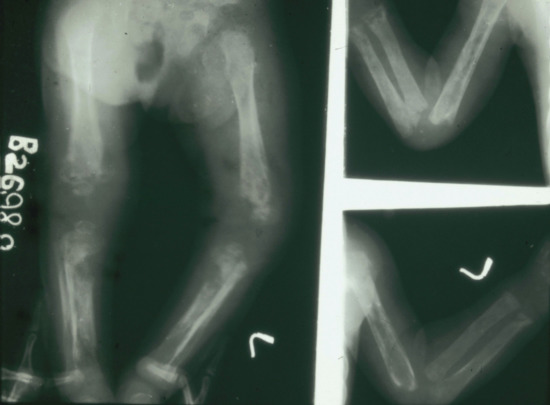

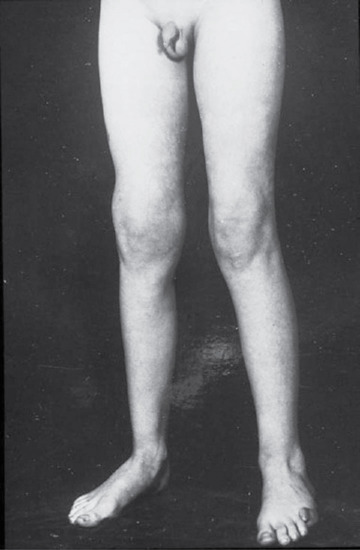

- Tabetic neurosyphilis was the most common form of neurosyphilis in the pre-antibiotic era, with an onset 15–25 years after primary infection. The most characteristic symptom is of lightning pains – sudden paroxysms of lancinating pain affecting the lower limbs. Other early symptoms include paraesthesia, progressive ataxia and bowel and bladder dysfunction (Figure 29.29). Tabes also causes neuropathic (Charcot) joints in the spine, hips, knees (Figure 29.30) and feet. Perforating ulcers of the feet, now much more commonly seen in diabetics, also occur.

Figure 29.28 Cardiovascular syphilis. (a) Chest X-ray showing a dilated aorta with linear calcification in the wall of the ascending aorta. (b) Chest X-ray showing an aneurysmal swelling (A) of the ascending aorta.

Figure 29.29 Neurosyphilis causing Argyll–Robertson pupils of the eyes. The abdomen shows multiple scars after surgical intervention for tabetic crises mimicking acute abdominal emergencies.

Figure 29.30 Tabes dorsalis. (a) Charcot's (neuropathic) joints of the knee. (b) X-ray of Charcot's joints of the knee showing a loss of normal alignment with multiple osteophyte formation.

Clinical variants

There is epidemiological synergy between HIV and other sexually transmitted infections [45]. Syphilis increases the risk of HIV acquisition and onward transmission. HIV infection may alter the natural history of syphilis [46].

In most patients with early HIV infection, the clinical features, serological test results and response to treatment are similar to those in non-HIV-infected persons [47]. With advancing immunosuppression, all of these may be significantly altered. Lues maligna and neurological and ocular involvement [48, 49, 50, 51] have been reported more commonly

Differential diagnosis

Primary syphilis

A wide variety of diseases can affect the genitals and must be considered (Table 29.1). Genital herpes and balanoposthitis have typical clinical features, although they may occur with a chancre. Secondarily infected traumatic sores may look like chancres. Chancroid should be considered, and not only in subtropical areas of the world. Sporadic epidemic outbreaks of clinically modified chancroid have been reported in the UK, Canada and Kenya. Improved techniques for the culture of Haemophilus ducreyi have been widely sought in several countries. The organism appears to be more common as a secondary invader than previously believed. Carrier states in both men and women are described. In general, the lesions described are rarely of the destructive and painful type previously believed to be classic [52].

Table 29.1 Differential diagnoses of primary syphilis in different genital areas

| Genital area | Other STIs | Trauma | Dermatoses | Inflammatory conditions | Drugs | Neoplasia |

| Penile | Genital herpes | ‘Zip injury’ | Lichen planus | Plasma cell balanitis | Fixed drug eruption | Squamous carcinoma |

| Chancroid | Lichen sclerosis | Behçet disease | Bowen disease | |||

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Psoriasis | |||||

| Granuloma inguinale | Balanitis | |||||

| Scabies | ||||||

| HPV infection | ||||||

| Other stages of syphilis | ||||||

| Cervical | Cervical ectopy or metaplasia | Cervical cancer or CIN | ||||

| Anal | HPV infection | Anal fissure | Squamous carcinoma | |||

| Haemorrhoids | ||||||

| Oral | Tonsillitis | |||||

| Behçet syndrome |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, human papillomavirus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

In lymphogranuloma venereum, ‘inflammatory bubo’ may resemble the unilateral and bilateral adenitis of early syphilis. Unlike syphilis, the glands are usually matted, adherent to the inflamed skin and show a tendency to central fluctuation.

Excoriated secondary syphilitic papules in women can be confused with multiple small chancres. Chancre redux is a recurrence of the primary sore at its original site [53]. Tertiary syphilis, tuberculous ulceration, cancer or pre-cancerous dermatoses such as erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease, can occasionally cause difficulty. The papules of scabies on the glans or on the shaft of the penis may arouse strong suspicions. Any lesion at the site of a healed primary has been labeled pseudochancre redux [54].

On the cervix, a chancre may easily be taken for an ‘erosion’ or a cancer [55], especially when suspected syphilis is not the reason for examination.

With a chancre on the lip, the most important differential diagnosis is facial herpes simplex. Apart from the appearance, the recurrent nature of herpes is helpful. Secondarily infected traumatic lesions with oedema may closely resemble a chancre, as may cancer of the lip. Traumatic ulcers of the tongue can sometimes be infiltrated. Behçet syndrome with both oral and vulvar lesions may present a problem. Tonsillar chancres may be mistaken for tonsillitis, glandular fever or Vincent angina. When the accompanying angular or submental adenopathy is painless, syphilis should be seriously considered.

A longstanding whitlow or paronychia ought to lead to examination for both herpes virus and Treponema pallidum. Where epitrochlear or axillary adenitis is painless, serological tests for syphilis (STS) are indicated.

In ‘modern’ societies, all oral and rectal lesions should give rise to a suspicion of possible syphilis. Anal fissures and anal warts, ‘haemorrhoids’, anal discharge and irritation or a finding of some form of sexually transmitted proctitis, for example due to gonorrhoea, herpesvirus or Chlamydia trachomatis, should alert the physician to the possibility of concomitant syphilis [56]. In the rectum, a chancre may be mistaken for a cancer.

Secondary syphilis

The skin manifestations of secondary syphilis are so variable that it must be considered in the diagnosis of all dermatoses that are in any way atypical (Table 29.2). Some of these dermatoses have already been mentioned.

Table 29.2 Differential diagnoses of secondary syphilis

| Other STIs | Dermatoses | Other inflammatory conditions | Drugs | Neoplasia |

| Genital herpes | Seborrhoeic dermatitis | Behçet syndrome | Systemic drug eruptions | Squamous carcinoma |

| Scabies | Pityriasis rosea | Infectious mononucleosis | Stevens–Johnson syndrome | Bowen disease |

| HPV infection | Psoriasis | Angular cheilitis | Kaposi sarcoma | |

| Circinate balanitis (reactive arthritis) | Lichen planus | |||

| Mycoses |

HPV, human papillomavirus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

With a macular rash, drug eruptions must first be considered. The history, itching and lack of adenopathy aid differentiation. Measles and rubella may cause difficulty, but it is pityriasis rosea that is most often called into question. The presence of a herald patch and the collarette of scales distinguish this condition from macular syphilis.

With papular eruptions, many diseases can cause difficulty in diagnosis, and it has to be remembered that people with seborrhoeic dermatitis or psoriasis can also have syphilis. Lichen planus with its shiny, angled, violaceous lesions should seldom cause difficulty. Acne vulgaris and seborrhoeic dermatitis may confuse the unwary, as may impetigo and occasionally leprosy or tuberculosis if the face is affected. In the ano-genital region, condylomata lata have been diagnosed as haemorrhoids and as condylomata acuminata. Balanitis circinata, hyperkeratotic lesions of reactive arthritis and genital herpes may also lead to misdiagnosis.

The micropapular varieties of syphilis can be confused with keratosis pilaris, lichen scrofulosorum, trichophytide and lichen planopilaris. Eruptions of the palms and soles may bear a striking resemblance to psoriasis and scaling mycoses.

With oral lesions, the question of aphthae has first to be considered. The painful nature of the lesions contrasts with syphilis and the aphthous lesions are markedly areolated [57, 58]. Tonsillitis or tonsillar papules with lymphadenopathy may make differential diagnosis from infectious mononucleosis a difficult clinical problem. An accompanying morbilliform rash, perhaps precipitated by the administration of ampicillin, may add to the confusion, especially as the condition is sometimes accompanied by false positive STS.

Tertiary syphilis

Skin reactions to bromides and iodides commonly deceived the physician in the past. On the face, lupus vulgaris, epithelioma and Bowen disease can cause diagnostic difficulties (Table 29.3). Midline granuloma, sycosis barbae, infiltrated forms of rosacea and lupus erythematosus have all been confused with late syphilis. On the trunk and limbs, it can resemble circinate psoriasis, leukaemic infiltrations and mycosis fungoides. On the legs, gummatous ulceration can look very like a venous ulcer. Bazin disease may also be simulated.

Table 29.3 Differential diagnosis of tertiary syphilis in different parts of the body

| Facial | Truncal | Legs |

| Lupus vulgaris | Psoriasis | Chronic venous ulcer |

| Rosacea | Mycosis fungoides | Bazin disease |

| Lupus erythematosis | ||

| Leukaemic infiltrations | ||

| Neoplasia |

Changes in the tongue should not be confused with the congenital deformity of scrotal tongue, when the tongue remains quite soft. Where leukoplakia is associated with interstitial glossitis, or fibrotic nodules, biopsy is necessary to exclude carcinoma.

Prognosis

The cure rates with initial treatment of early syphilis are better than 95%. The long-term outcome of adequately treated cases is excellent. In late syphilis, infection can usually be arrested although some treponemes may persist in less accessible sites (e.g. the eye and nervous system). As long as immune function is normal, this rarely has clinical sequelae. The outlook for HIV-positive and other immunocompromised patients appears to be less assured; however, long-term studies in these patients are needed.

Investigations

The tests used to diagnose syphilis continue to evolve and will vary in different parts of the world according to the laboratory resources available. Microscopic identification of the causative organism is possible in specimens obtained from lesions but requires the availability of dark-field microscopes and experienced operators. Serological testing remains the bedrock of screening in most settings but the choice of tests will vary; enzyme immunoassay (EIA) tests are now the most commonly used screening tests. In developed countries, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based tests are becoming more widely available as are rapid point-of-care tests that can give rapid results on fingerprick specimens.

Dark-field microscopy

Treponema pallidum can be identified from lesions of primary, secondary or early congenital syphilis by dark-field microscopy. In primary syphilis, it makes the diagnosis possible before measurable antibodies appear. In secondary syphilis, it provides immediate confirmation of a clinical diagnosis. The organism has a characteristic morphology and motility, with a sinusoidal profile and a wavelength and amplitude of 1.1 and 0.4 μm, respectively [59].

The sore should be thoroughly cleaned with saline washes and/or saline compresses. A course of oral sulphonamides may be initiated. Where lesions are dry and crusted, it is necessary to scrape with a Volkmann spoon or open scarifier. Suspected secondary lesions almost always require scarifying, and patience is needed if T. pallidum is to be demonstrated. If the lesion is syphilitic, bleeding will not be marked. After scraping, some 5 min should be allowed for red cells to settle so that clear serum can be collected and examined. Special care is indicated when assessing treponemes found in serum from oral lesions. If a suspected primary lesion has been treated with antiseptic or antibiotic remedies or if there is a marked secondary infection of the sore, the examination may not be successful. Repeat testing on two or more consecutive days is advised.

In all highly suspect genital and/or oral lesions where it proves impossible to demonstrate T. pallidum, lymph node puncture material, mixed with injected sterile saline (0.5 mL), should be examined. Any treponeme found will always be T. pallidum.

In women, some 25% of the primary sores occur on or in the uterine cervix. A primary sore may be obvious on examination. In other cases, the cervix is oedematous, enlarged and pale. The suspicion that there is a primary lesion in the cervical canal can be confirmed by dark-field microscopy of material obtained ‘blindly’ from the cervical canal by a platinum loop. T. pallidum has also been demonstrated in material from the apparently healthy cervical canal of named contacts of early syphilis sufferers.

The organism can also be identified by direct immunofluorescent antibody testing where no facilities for dark-field microscopy exist.

In biopsy specimens from late syphilis, or in atypical early lesions, it may be possible to identify the organism using silver stains such as Warthin–Starry preparations or by direct immunofluorescent antibody testing.

Molecular amplification tests

Polymerase chain reaction diagnosis has been based on primers and probes prepared from the 47 kDa gene. After a 40-cycle series of denaturing, annealing and extension, the PCR products can be visualized by electrophoresis or Southern blot hybridization with a 32P-labelled probe and then autoradiography. This technique should be of greatest value in detecting the low numbers of treponemal products in neurosyphilis; it should also be useful in congenital syphilis, in which the interpretation of serological test results may be difficult. Molecular amplification tests have also been successfully used in multiplex systems to investigate the aetiology of genital ulcers [60].

RNA amplification is more sensitive than PCR, and positive results are indicative of living organisms. Reverse-transcriptase PCR uses the 16S ribosomal RNA of T. pallidum as the template.

Molecular diagnosis on lymph node biopsy specimens has been described [61].

Multiplex testing for T. pallidum and other genital ulcer pathogens is available in a few specialized laboratories using their own primers. Although there is no commercial system currently available there is strong evidence to suggest that PCR might play an important role in the near future [62].

Serological tests

Serological tests for syphilis and serological tests for other treponematoses can be divided into reaginic or non-treponemal tests, and specific or treponemal tests. The antibodies detected by the treponemal tests may be further divided into those generated by specific antigens, present only in pathogenic treponemes, and those shared with non-pathogenic treponemes (group antibodies). This distinction has significance in so far as different types of antibody may influence the results of several serological tests. The immune responses in all the treponematoses appear to be the same, and there is no test that will differentiate one treponematosis from another [63]. The sensitivity of the different tests varies according to the stage of the syphilis (Table 29.4).

Table 29.4 Sensitivies of serological tests at different stages of untreated syphilis

| Stage of disease (% positive [range]) | ||||

| Test | Primary | Secondary | Latent | Tertiary |

| VDRL | 78 (74–87) | 100 | 95 (88–100) | 71 (37–94) |

| RPR | 86 (77-99) | 100 | 98 (95–100) | 73 |

| FTA-ABSa | 84 (70–100) | 100 | 100 | 96 |

| TPPAb | 76 (69–90) | 100 | 97 (97–100) | 94 |

| EIA | 93 | 100 | 100 | |

Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA.

aFTA-ABS and TPPA are generally considered to be equally sensitive in the primary stage of the disease.

EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption; RPR, rapid plasma regain; TPHA, Treponema pallidum haemagglutination test; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Standard non-treponemal tests

The non-treponemal tests detect immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies to lipoidal material released from damaged host cells and to lipoidal-like antigens of T. pallidum. There are four tests available that use the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) antigen (consisting of cardiolipin, cholesterol and lecithin) as the principal component. These tests are quantitative and are useful in assessing the response to treatment. Reactivity to these tests does not develop until 1–4 weeks after the chancre appears in primary syphilis. Titres are highest in secondary syphilis. The prozone phenomenon occurs in 2% of sera; undiluted sera give negative results because of antibody excess, the presence of blocking antibodies, or both. The titre slowly declines after the secondary stage, and it may spontaneously become negative in some cases of late latent syphilis and neurosyphilis.

The VDRL slide test is widely used and requires the microscopic demonstration of antigen–antibody flocculations in heat-inactivated serum.

The unheated serum reagin (USR) test is similar to the VDRL test but does not require preheated serum, because the antigen has been stabilized.

The rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) use either charcoal or red paint pigment added to the USR reagent to enhance visualization of the antigen–antibody flocculations. The flocculations are visible macroscopically. This test can be performed in consulting rooms, clinics and laboratories where facilities, experience and personnel are limited.

Treponemal antigen tests

Specific treponemal antibody tests are used for confirmatory testing. They detect antibodies to antigenic determinants of treponemes. They are qualitative procedures and are not helpful in assessing treatment responses. Once positive, they tend to remain positive for life, irrespective of treatment. They are used to differentiate true positives from false positives in the standard non-treponemal antibody tests.

The hunt for a test giving 100% sensitivity and specificity has gone through several stages. In 1949, Nelson and Mayer [64] proved that serum from syphilitic patients contains an antibody that, in the presence of complement, inhibits the normal movements of virulent T. pallidum (specific treponemal immobilizing antibody). For this test – the TPI (T. pallidum immobilization) test – virulent T. pallidum is used (Nichol's strain) obtained from rabbits. The reaction of the treponemes in the presence of the patient's serum is observed by dark-field microscopy. If 50% or more of the treponemes are immobilized, the test is reported as positive; if less than 20% are immobilized, it is negative. In 99% of cases, the result is very clear-cut and specific, probably nearly 100% [65, 66]. The test is time consuming and therefore expensive.

The TPI test becomes positive a few days to a week later than the reagin tests, that is later in the primary stage. In the late stage it is almost always positive, although a negative result may occur. The great importance of the TPI test has been its specificity, making it possible to distinguish biological false positive reaginic reactions from genuine positives.

With early treatment of syphilis, the TPI may become negative. However, if the disease has been untreated for more than 5–6 months, the reaction is likely to remain positive for the rest of the patient's life, despite any later treatment.

The fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test [67, 68, 69] and the FTA-ABS double staining (FTA-ABS DS) test are both indirect immunofluorescent tests. The double stain test employs a fluorochrome-labelled counterstain for T. pallidum and an antihuman IgG conjugate labelled with tetra-methyl rhodamine isothiocyanate to detect antibody in the patient's serum. False positive results may occur in about 1% of sera. Possible causes include technical error, Lyme borreliosis, pregnancy, genital herpes, alcoholic cirrhosis and connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma.

The T. pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA) was first described by Rathlev in 1967 [70]; a variant microtechnique has since gained popularity. In all forms, the TPHA is simple to perform and results are readily reproducible [71]. The test is very sensitive and specific [72, 73]. The microhaemagglutination assay for antibodies to T. pallidum (MHA-TP) detects passive haemagglutination of erythrocytes sensitized with ultrasonicated Nichol's strain T. pallidum. In many laboratories, the TPHA has been replaced by the similar T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) test that uses gelatine particles rather than erythrocytes as the carrier. It is more sensitive than the FTA-ABS test.

Treponemal EIA commercial tests were initially designed as confirmatory tests for syphilis [74]. Serum is added to micro-wells coated with a treponemal antigen. After incubation, an enzyme-labelled antihuman immunoglobulin conjugate and enzyme substrate are added to detect antigen–antibody reaction. The test can be modified to detect specific IgM antibody.

Western blot

Treponema pallidum western blot is available in some research laboratories and has similar sensitivity and specificity to the FTA-ABS test [75]. The presence of antibodies to the immunodeterminants with molecular weights 15.5, 17, 44.5 and 47 kDa appears to be diagnostic for acquired syphilis. When an IgM-specific conjugate is used, the test has value in the diagnosis of congenital syphilis.

Rapid point-of-care tests for syphilis

The resurgence of syphilis worldwide and limited laboratory diagnostic facilities in high-prevalence countries has stimulated the development of rapid point-of-care tests [76]. These can be performed outside a laboratory setting with minimal training and no equipment using a fingerprick blood sample. The tests are simple, are not affected by prozone effects, and can be transported and stored at temperatures <30°C. Their sensitivity is 85–98% and their specificity 93–98%. They are used for targeted screening in resource-poor countries, especially for the screening of pregnant women and other high-risk groups. In developed countries, their use is also being studied in outreach settings with MSM and sex workers and their clients [77].

Guidelines for serological screening

There are many commercial tests in any given format whose performance characteristics vary. Recent studies suggest that a treponemal EIA used as a single test is an appropriate alternative to the combined VDRL/RPR and TPHA screens. It has a higher specificity than the FTA-ABS test. The test also has advantages of automated or semiautomated processing and objective reading of results, and can be interfaced with laboratory computer systems to allow electronic laboratory report generation.

Screening can be performed by either an EIA or the combined VDRL/TPHA test. Positive results are confirmed with a treponemal test of a different type. It is essential to confirm the presumptive serological diagnosis of syphilis on a second specimen from the patient.

Biological false positive reactions

All the tests in use can produce biologically false positive (BFP) results (Table 29.5). Reagins can be found in the blood of most normal people, and it is possible to make tests for reagins so sensitive that a high percentage of positives can be demonstrated. Some apparently healthy persons produce reagins in excess. They are classified as BFP reactors. BFP reactions may be acute or chronic, that is they last less than or more than 6 months. The same occurs in association with acute and chronic diseases (Table 29.5). Persistently low-titre-positive reagin tests with repeatedly negative treponemal tests are the rule in acute BFP reactions. They rarely last more than 3 months. Strongly positive reactions are more common in chronic BFP reactors.

Table 29.5 Biological false positive reagin tests for syphilis in acute and chronic diseases

| Acute | Chronic |

| Infections | Autoimmune diseases |

| Malaria | Dysgammaglobulinaemias |

| Leprosy | |

| Typhus | |

| Viral pneumonia | |

| Infectious mononucleosis | |

| Filiarisis | |

| Trypanosomiasis | |

| Lyme disease | |

| Pregnancy |

The following are among the commonest associations with acute BFP reactions: malaria, leprosy (especially the lepromatous form) [78, 79], typhus, respiratory tract infection (especially viral pneumonia), infectious mononucleosis, active pulmonary tuberculosis, hepatitis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, measles, chickenpox, filariasis, trypanosomiasis, leptospirosis and relapsing fever. BFP reactions are also reported in connection with pregnancy [80] and narcotic addiction.

Chronic BFP reactions are associated with autoimmune diseases and dysgammaglobulinaemia. Chronic BFP reactions may exist for some time and herald the onset of connective tissue disease by some years, for example systemic lupus erythematosus (especially in Rhesus-negative women), polyarteritis nodosa and rheumatoid arthritis [81, 82].

Not all authors agree that the VDRL test is the most likely test to be associated with BFP reactions. One study, which concentrated on the phenomenon associated with dermatological diseases, found that the FTA and FTA/ABS tests most often produced BFP reactions [83]. In some elderly persons, BFP reactions with the FTA/ABS test are associated with connective tissue diseases, and, in addition, with the presence in healthy people of ‘rheumatoid factor’. However, ageing itself may be responsible [84, 85, 86].

A completely new cause of false positive FTA/ABS results was described in 1986 by Hunter et al. [87] at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA. They investigated patients with Lyme disease, and compared their serological findings with specimens from patients with syphilis. Cross-reactivity with the causative spirochaete of Lyme disease could be absorbed without T. phagedenis (reactive arthritis strain).

Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid

Indications for the examination of CSF in syphilis include the following:

- Neurological, ophthalmic or auditory symptoms and signs.

- Other clinical evidence of active infection – aortitis, gumma or iritis.

- Treatment failure.

- HIV infection.

- A non-treponemal serum titre of more than 32 if the duration of syphilis is over 1 year.

- A non-penicillin-based treatment regimen is planned.

Many clinicians consider an examination of CSF unnecessary in early syphilis, but prefer to examine it before discharging the patient as cured after the 1–2 years’ post-treatment follow-up. In untreated asymptomatic late syphilis, a CSF examination should always be done. A normal CSF is by definition an essential prerequisite for a diagnosis of latent syphilis.

The typical CSF findings of neurosyphilis consist of:

- Moderate mononuclear pleiocytosis (10–400 cells/mL).

- Elevated total protein (0.46–2.0 g/L).

- Positive CSF VDRL criteria.

The CSF VDRL test is highly specific and false positive results are rare in the absence of blood contamination. A negative CSF VDRL test does not exclude neurosyphilis, although non-treponemal serological tests usually remain positive in both serum and CSF in such cases.

Reactivity to tests using treponemal antigens, particularly to the FTA/ABS test and/or TPHA test, may be caused by transudation of T. pallidum-specific IgG from the serum of patients with adequately treated disease, and therefore is not necessarily a sign of active central nervous system involvement. On the other hand, non-reactivity of the CSF to these assays in all probability excludes the diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

Management

Current treatment regimens are largely based on over 50 years of clinical experience with penicillin, expert opinion and open clinical studies [88, 89] although there have been some recent randomized clinical trials [90, 91, 92, 93, 94]. Many antibiotics, with the notable exceptions of the aminoglycosides and sulphonamides, have some treponemicidal activity, and their administration for other conditions may abort or modify the natural history of syphilis [95, 96, 97, 98].

Management overview

Parenteral penicillin G is the preferred drug at all stages of syphilis; the preparations used, the dosage and the duration of treatment depend on the clinical stage and disease manifestations. Penicillin remains not only the most effective treponemicide, but it is easy to administer, has few side effects and is relatively inexpensive. Results continue to be excellent for all forms and stages of treponemal disease, and there are no signs that T. pallidum has developed resistance to this antibiotic. Injectable penicillins are generally preferred to oral preparations because of problems of patient compliance and uncertain absorption from the gastro-intestinal tract.

Adequate treatment requires the maintenance of serum concentrations in excess of 0.03 units/mL for at least 10 days. A single intramuscular dose of 0.6 mega units of aqueous procaine penicillin gives an effective serum concentration for at least 24 h; in comparison, a single intramuscular dose of 2.4 mega units of benzathine penicillin G maintains effective levels for about 2 weeks. As this preparation may cause pain on injection, 1.2 mega units are usually given in the upper and outer quadrant of each buttock.

It should be noted that although benzathine penicillin G is recommended first line therapy for most syphilis cases, it is an unlicensed medication in the UK. The unlicensed status of the medicine should be explained to the patient and a record that it is being given with the patient's consent entered in the case notes.

Treatment of late syphilis theoretically may require a longer duration of therapy because organisms are dividing more slowly, but the validity of this concept has not been addressed. The penetration of aqueous procaine penicillin into the CSF (as into the aqueous humour) is poor; that of erythromycin is poorer and that of benzathine penicillin poorest of the three [96]. For treatment of neurosyphilis, high dosages of crystalline benzyl penicillin G, plus probenicid, should be considered. Desensitization of penicillin-allergic patients is recommended.

In patients who are hypersensitive to penicillin, regimens based on tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin and chloramphenicol have all been successfully used to treat syphilis; however, success is less assured than with penicillin. Azithromycin, given in dosages of 500 mg daily for 10 days, or in a single 2 g dosage, has recently been successful, but there are concerns about the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [97, 98].

All patients with syphilis should be offered screening for other sexually transmitted infections and HIV. Serological testing for HIV should be repeated after 3 months in those persons presenting with primary syphilis who initially test negative.

Pregnant women: only penicillin-based regimens have documented efficacy, and desensitization should be considered in those who are allergic. Those women who have had documented treatment for syphilis in the past do not need retreatment in current or subsequent pregnancies so long as there is no clinical evidence of syphilis, and the VDRL or RPR titre is negative. First line treatment is with procaine penicillin G. Alternative drug therapies include erythromycin or azithromycin.

HIV-seropositive individuals: it is recommended that CSF examination be performed in all patients with syphilis who are HIV seropositive. Generally, recommended regimens are the same as those in HIV-negative individuals if CSF examination is normal [47]. Ceftriaxone has been successfully used in a pilot study [91].

Penicillin reactions

Accidental deaths following treatment are very rare and mainly due to anaphylactic shock reactions to penicillin. In addition to early and late allergic reactions and the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction, Hoigne reactions (acute psychotic symptoms due to inadvertent intravenous injection of procaine in procaine penicillin) are recognized. If penicillin is used in patients with a history of allergy, it is advisable to keep the patient under observation for 15–20 min after the injection. An emergency kit should always be available.

Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile reaction that occurs in many patients within 24 h of commencing treatment. It is mediated by cytokines. Headache, myalgia, bone pains and an exacerbation of skin lesions may accompany the fever. It must be differentiated from penicillin allergy. Patients should be advised that it might occur. Symptoms may be controlled by antipyretics. The fever (38–40°C) rarely persists more than 8 h.

In pregnant women the reaction may induce early labour or cause fetal distress. In late neurosyphilis and cardiovascular syphilis, the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction can be more serious and may be associated with life-threatening sequelae. Many clinicians advocate a short course of corticosteroids to lessen its effects in these patients. One such regimen is to prescribe oral prednisolone 30–60 mg daily for 3 days, beginning syphilis treatment 24 h after the first dose.

Follow-up

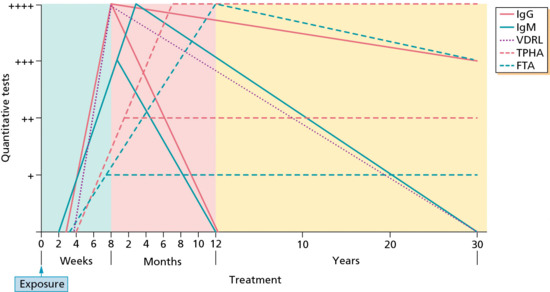

Follow-up for clinical and serological assessment should be done at 3, 6 and 12 months after the completion of treatment in early syphilis (Figure 29.31). Recurrence is due more often to reinfection than to relapse.

Figure 29.31 Typical serological responses at different stages and in response to treatment of syphilis. FTA, fluorescent treponemal antibody; Ig, immunoglobulin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

(Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA, USA.)

Reinfections are more likely during the first year after penicillin therapy. Non-treponemal antibody test titres correlate with disease activity and will usually become negative with time after successful treatment. In some patients, who are described as being ‘reagin fast’, low titre positivity in these tests may persist for life. Apart from up to 25% of patients treated for primary syphilis, the treponemal antibody tests will continue to remain positive after successful treatment.

In late latent or tertiary benign syphilis, a 2-year follow-up is adequate. Quantitative non-treponemal serological testing is repeated at 3 and 6 months, and each 6 months thereafter. Follow-up of cardiovascular and clinical neurosyphilis should be for life.

Treatment failure is suggested by a fourfold increase in titres, less than a fourfold decrease in pretreatment titres within 12–24 months, and the development of symptoms or signs attributable to syphilis. All treatment failures require CSF examination. In cases of serological or clinical relapse, retreatment with double doses is recommended.

In latent syphilis, a 2-year follow-up is adequate. The same applies to late benign syphilis. In neurosyphilis it is usual to repeat the CSF examination every 6 months until the cell count has become normal. There is a slower response of the CSF VDRL criteria and total protein. Retreatment should be considered if the cell count shows an inadequate response or if all of these parameters have not returned to normal by 2 years. In cases of serological or clinical relapse, retreatment with double penicillin doses is recommended. Patients treated for neurological or cardiovascular syphilis should be followed up for many years.

Management of sexual contacts

It is recommended that attempts be made to identify, trace and offer further investigation to at-risk sexual contacts. In early syphilis, these are contacts occurring within 3 months plus the duration of symptoms for primary syphilis, within 6 months plus the duration of symptoms for secondary syphilis and within 1 year for early latent disease. All long-term partners of patients with late syphilis should be offered investigation.

Many clinicians recommend presumptive treatment of all sexual contacts within the 90-day period preceding patient presentation of early syphilis if serological test results are not immediately available and if follow-up cannot be assured.

Resources

Further information

- British Association for Sexual Health and HIV: www.BASHH.org (last accessed June 2014).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): www.cdc.gov (last accessed June 2014).

- Holmes K, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al., eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 4th edn. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.

Patient resources

- BUPA fact sheet: http://www.bupa.co.uk/individuals/health-information/directory/s/syphilis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fact sheet: http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fact sheet: http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-MSM-Syphilis.htm.

- Family Planning Association patient information leaflet: http://www.fpa.org.uk/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-helpsyphilis.

- Medline Plus fact sheet: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/syphilis.html.

- Netdoctor fact sheet: http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/diseases/facts/syphilis.htm.

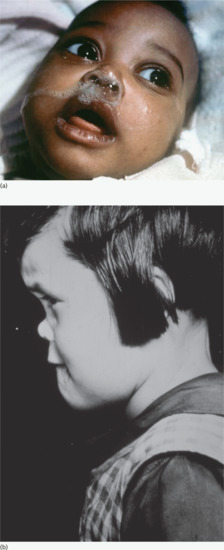

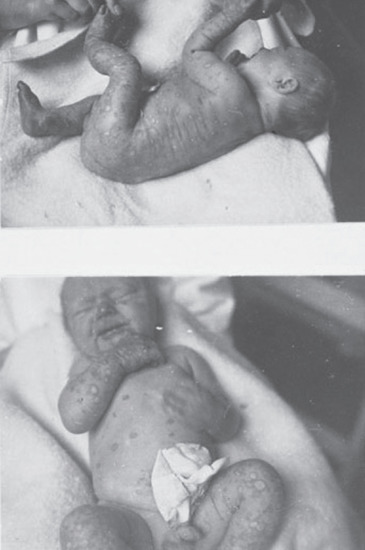

- NHS choices fact sheet: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Syphilis/Pages/Introduction.aspx.