CHAPTER 36

Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Anthony C. Chu

Hammersmith HospitalImperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, UK

Definition and nomenclature

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is the name given to a group of clinically similar papulosquamous dermatoses, the underlying pathogenesis of which is only just beginning to be unravelled. They initially present with erythematous hyperkeratotic perifollicular papules which tend to coalesce into plaques but may progress to erythroderma, particularly in adults. The distribution, age of onset and speed of onset differ markedly between patients and these differences have been used to classify PRP into a number of clinically distinct subtypes.

Introduction and general description

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a papulosquamous dermatosis of unknown cause. PRP was first described by Claudius Tarral in 1828 and given its present name by Besnier in 1889 [1]. It has been divided into five clinical types by Griffiths [2] and a sixth type related to HIV infection has been described more recently [3].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is an uncommon condition which was estimated to occur in less than 1 in 5000 patients presenting to a large dermatology centre in the UK [4].

Age

The rare familial form of PRP starts in early childhood. The acquired forms of PRP have a bimodal age distribution with peaks in the first and fifth decades [4].

Sex

It shows an equal sex incidence.

Ethnicity

It shows no racial predilection.

Associated diseases

Although there have been a number of case reports of PRP in association with a variety of solid tumours including carcinoma of the larynx, colon, kidney and lung [5, 6], PRP is not generally thought to be associated with an increased incidence of malignancy.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris has been described in association with various autoimmune diseases including systemic sclerosis and autoimmune thyroiditis [7–9], though the paucity of such reports suggests that a causal link is unlikely.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of PRP is unknown. The rare genetic form has been linked in some pedigrees to gain-of-function mutations in the CARD14 gene, an activator of nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [10]. Such mutations appear to be rare in sporadic forms of PRP [11]. Streptococcal superantigens have been implicated in children with sporadic forms of PRP [12, 13]. PRP has also been associated with HIV infection [3].

Pathology

The histological features of PRP are not pathognomonic and change with the evolution of the disease. They do, however, allow discrimination from psoriasis and other causes of erythroderma.

The skin shows hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging. Ortho- and parakeratosis may alternate in the skin and the follicles may show foci of parakeratosis in the perifollicular shoulder. There may be patchy or confluent hypergranulosis. Dermal capillaries are dilated but are not tortuous as seen in psoriasis. Acantholysis may be present, often restricted to adnexal epithelium [14]. There is a sparse lymphocytic dermal infiltrate but no neutrophils (Figure 36.1).

Figure 36.1 Histopathology of pityriasis rubra pilaris: follicular plugging, acanthosis with exaggerated follicular shoulders, spotty parakeratosis and mild upper dermal inflammatory infiltrate.

Genetics

The familial form of PRP is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Recent studies have mapped PRP to 17q25.3 which overlaps with the PSOR2 susceptibility locus for psoriasis. Using candidate gene screening, investigators have identified heterozygous gene mutations in CARD14 which encodes the caspase recruitment domain family, member 14. CARD14 is an activator of NFκB signalling, which is implicated in inflammatory diseases [10].

Clinical features

History

The more common generalized sporadic forms (types I and III) tend to have an acute onset. The rare familial form of PRP (type V, see later) generally has a slow and gradual onset.

Presentation

Patients typically present with well-defined salmon-red or orange-red dry scaly plaques, which may coalesce and become widespread. Typically islands of normal skin are present, the so-called ‘islands of sparing’. The disease often starts on the scalp before spreading down over the rest of the body. Some patients may become erythrodermic. Pruritus may be present in the early stages of the disease.

On the elbows, wrists and the backs of the fingers, characteristic follicular hyperkeratosis may be present – ‘nutmeg grater’ papules. Palms and soles may become thickened and fissured with an orange discoloration. In type IV PRP, the disease is largely limited to the extremities.

Clinical variants

Six clinical variants have been described [2, 3].

Classical adult-onset PRP (type I)

This is the most common and recognizable form, representing some 50% of all cases. It affects the sexes equally with highest incidence between 40 and 60 years of age. The eruption usually starts without obvious precipitating factors as an erythematous slightly scaly macule on the head, neck or upper trunk. Further macules appear within a few weeks and at this stage the rash may be mistaken for seborrhoeic dermatitis. The true diagnosis becomes apparent with the appearance of a profusion of erythematous perifollicular papules, each with a central acuminate keratotic plug. Follicular lesions are initially discrete but then coalesce to form groups of two, three or more. Irritation is initially absent, but may be pronounced as the disease spreads (Figure 36.2a).

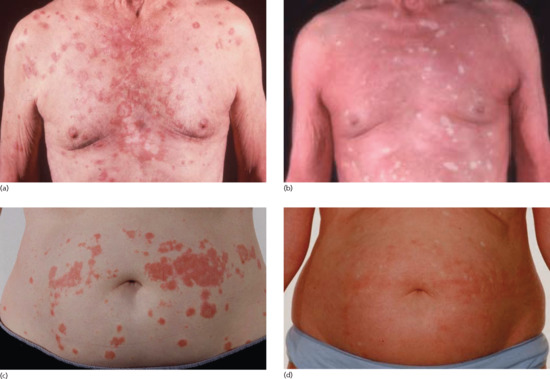

Figure 36.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP): (a) classical adult-onset, type I; (b) classical juvenile-onset, type III; and (c) circumscribed juvenile-onset, type IV. Note: ‘islands of sparing’ in erythrodermic type I PRP (a), orange-red erythema with cephalocaudal downward extension in type III PRP (b), and prominent ‘nutmeg-grater’ keratotic follicular spines in type IV PRP (c).

Interfollicular erythema appears and the follicular lesions are gradually submerged in sheets of erythema of a slight orange hue, which typically spreads from the head to the feet. The face becomes uniformly erythematous and mild ectropion may follow (Figure 36.3a). Prolonged erythema may give rise to peripheral oedema and, in the elderly, may precipitate high-output cardiac failure. The scalp shows diffuse bran-like scaling. Erythroderma frequently develops within 2–3 months (see Figure 36.2a). In most cases, sharply demarcated islands of unaffected skin 1 cm in diameter remain as a helpful diagnostic sign (‘island of sparing’). Circumscribed islands of deeper erythema are also sometimes seen.

Figure 36.3 Classical adult-onset PRP: (a) confluent orange-red erythema on the face and neck with prominent ‘islands of sparing’; (b–d) prominent erythema and scale on the dorsa of the hands and wrists with marked orange-yellow palmoplantar keratoderma; (e) thickening of the nails, subungual hyperkeratosis and splinter haemorrhages.

The palms and soles become hyperkeratotic and yellow (Figure 36.3b–d). The nails are thickened and discoloured distally, showing splinter haemorrhages, but unlike psoriasis there is no dystrophy of the nail plate and pitting is minimal [15] (Figure 36.3e).

Untreated, type I PRP does eventually resolve in an average of 3 years in the majority of affected patients (see Disease course and prognosis).

Atypical adult-onset PRP (type II)

This is a much more chronic form, which may last many years. The scaling is rather more variable than in type I PRP: although perifollicular scale and palmoplantar keratoderma are both features, many patients show eczematous features and the keratoderma is coarser than in other types. The rapid progression of inflammation from the head down towards the feet as occurs in type I PRP does not occur and erythroderma is less common. It accounted for 5% of cases in a large series [4].

Classical juvenile-onset PRP (type III)

Type III is the most common childhood form of PRP and is considered to be the counterpart of type I PRP but with an onset between the ages of 5 and 10 years [16] (Figure 36.2b). This form of PRP usually undergoes spontaneous resolution in 1–2 years. Some patients with type III PRP may evolve into type IV PRP and vice versa [16]. Recurrence of type III PRP in later adult life has been reported [17].

Circumscribed juvenile PRP (type IV)

This type represented about 25% of cases of PRP in the series cited earlier [4]. It occurs in prepubertal children, usually under 12 years of age [16]. Commonest features are well-circumscribed plaques of erythema and follicular hyperkeratosis occurring on the elbows and knees (Figures 36.2c and 36.4a,b). Scattered erythematous scaly macules may be present on the trunk and scalp. Palmoplantar keratoderma may be observed (Figure 36.4c–d). The prognosis of type IV PRP is uncertain but there have been reports of the disease remitting in teenage years.

Figure 36.4 Juvenile-onset circumscribed PRP may persist into adulthood, as here: (a,b) circumscribed areas of hyperkeratosis over the elbows and knees may not show prominent follicular hyperkeratosis; (c,d) there may be prominent involvement both of the dorsa of the hands and feet and of the palms and soles.

Atypical juvenile PRP (type V)

This chronic childhood type accounted for a further 5% of cases [4]. Familial PRP is most often of this type, which may be genetically heterogeneous and may be difficult to distinguish from ichthyoses and erthyrokeratoderma [18]. Type V PRP may be present at birth or start in early childhood with erythema and hyperkeratosis. Follicular hyperkeratosis is a prominent feature and keratoderma is common. Scleroderma-like changes have been described in the hands and feet.

HIV-related PRP (type VI)

This form of PRP became apparent with the onset of the HIV epidemic [3, 19]. It tends to resemble type I PRP and to be resistant to treatment. It may, however, respond to antiretroviral therapy. Spontaneous remission without treatment has been reported in one patient after 2 years [19]. Some patients develop elongated filiform keratoses on the face and trunk. An association with truncal conglobate acne has been noted [3, 19].

Differential diagnosis

Dermatoses with erythema and follicular hyperkeratosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis. These include:

- Psoriasis (Table 36.1).

- Erythrokeratoderma variabilis.

- Sézary syndrome and other T-cell lymphomas.

- Other forms of erythroderma.

Table 36.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) and psoriasis compared

| PRP | Psoriasis | |

| Scalp scaling | Furfuraceous | Adherent |

| Palmoplantar keratoderma | Constant | Less common |

| ‘Islands of sparing’ | Characteristic | Less common |

| Nail pitting and salmon patches | Absent | Common |

| Nail growth rate | Moderate increase | Marked increase |

| Epidermal cell turnover | Moderate increase | Marked increase |

| Munro microabscesses | Absent | Characteristic |

| Seronegative arthropathy | Rare | Common |

| UVB phototherapy | Poor response | Good response |

| Topical corticosteroids | Limited response | Good response |

| Methotrexate | Variable | Good |

| Tumour necrosis factor α blockade | Variable | Good or excellent |

| Interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23 blockade | Probably excellent | Excellent |

Type IV PRP shares many clinical features with keratosis circumscripta.

Complications and co-morbidities

Dependent oedema and risk of high-output cardiac failure in erythrodermic patients are well recognized.

Disease course and prognosis

Disease course and prognosis depends on the type of PRP. Classical adult PRP (type I) may progress from limited disease to erythroderma in a matter of weeks (Figure 36.5a–d) but eventually clears spontaneously in the majority of affected patients [2] (Figure 36.6a–f). In a review of 46 patients seen before the era of systemic retinoids or biological agents, resolution was observed in 80%, of whom half had cleared by 3 years [20]. Spontaneous resolution after as long as 20 years has been reported [21] but in some patients it may persist indefinitely [2] (see Figures 36.5 and 36.6). Classical juvenile PRP (type III) typically runs a shorter course with remission in an average of 1 year [2]. Atypical PRP (types II and V) are chronic diseases but are usually more limited in extent than types I and III. The prognosis of circumscribed juvenile PRP (type IV) is uncertain but may last indefinitely (see Figure 36.4).

Figure 36.5 Evolution of type I PRP: (a,b) progression over 4 months from limited seborrhoeic dermatitis-like rash on the upper trunk to erythroderma in an elderly man; (c,d) progression over 4 weeks from limited inflammation on the trunk and limbs to erythroderma in 53-year-old female.

Figure 36.6 Resolution of type I PRP: (a,d) erythrodermic PRP at presentation 6 months after initial onset in a 60-year-old male: note ‘islands of sparing’ and dramatic oedema of lower extremities; (b,e) significant improvement over ensuing 12 weeks with acitretrin therapy; (c,f) complete resolution and off therapy 18 months after presentation.

Investigations

Diagnosis is made on clinical features and supported by histology. No other tests are indicated.

Management

This is a rare disease for which there have been no large controlled trials of treatment interventions: recommendations are thus based on case reports, small series and retrospective reviews. In a disease in which spontaneous resolution is the norm, claims of treatment success must be balanced against this. Patients who are erythrodermic may need intense supportive care to prevent hypothermia, electrolyte imbalance, protein loss and sepsis.

In a review of 40 patients with PRP (36 with classical adult type I disease), 14 showed a marked clinical improvement (≥75% reduction in baseline severity) without recourse to systemic or phototherapy. Only three patients appeared to derive benefit from various forms of phototherapy (partial response only). Nineteen patients received acitretin alone of whom five showed a marked and five a partial response. Three patients were reported to have shown marked responses to methotrexate (one in combination with acitretin) [22].

In a systematic review of the response of PRP type I to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, the authors felt able to attribute either complete (n = 10) or partial (n = 1) responses to infliximab, adalimumab or etanercept in 11 of 15 eligible cases [23]. It should be noted that the majority of patients continued either acitretin or methotrexate when TNF antagonist therapy was introduced. Selective reporting bias is inherent in such an analysis but the review does suggest that these agents may be more effective than standard systemic therapy.

Several case reports of dramatic responses to the anti-interleukin (IL) 12/IL-23 antibody, ustekinumab, have been reported. This agent suppresses activation of the NF-κB pathway, which is known to be overactive in individuals with familial PRP. Marked improvement within 4 weeks of commencing treatment has been reported in a patient with familial PRP in whom a CARD14 mutation was demonstrated [22] and in several sporadic cases. It may be that this agent will become the agent of choice but further evidence of its efficacy in this disorder is needed.

Emollients should be applied liberally and form an important part of management for treating dry skin and restoring barrier function in all patients with PRP. Topical corticosteroids may provide symptomatic relief in patients with pruritus but have no long-term effect on the course of PRP. Topical calcipotriol and topical tazarotene have both been advocated for type IV PRP but the evidence of efficacy is based on very small numbers [29, 30].

If systemic therapy is warranted, acitretin at a dose of up to 50 mg/day should be considered. Alternatively, methotrexate in doses of up to 20 mg once weekly may be considered. Responses are not as good as those seen with psoriasis: combination with acitretin has been advocated [31].

Ustekinumab may prove to be more effective than other agents and, from preliminary evidence, it may be appropriate to consider this agent in preference to anti-TNF agents for severe type I PRP when acitretin or methotrexate have failed or cannot be used [24, 25–27, 28]. In these circumstances, however, TNF-α antagonists may also be considered.

Anecdotal case reports of benefit have been claimed for narrow-band UVB phototherapy [32] and, in a total of three severe cases recalcitrant to other systemic therapy, extracorporeal photochemotherapy [33, 34]. These interventions may be considered where systemic therapy cannot be given.

Resources

Further information

- Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris, the Dowling Oration, by Dr Andrew Griffiths, 2003 http://www.prp-support.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Griffiths-Dowling-Oration-2003.pdf (last accessed April 2015).

Patient resources

- PRP Support Group http://www.prp-support.org/wp/ (last accessed April 2015).

References

- Besnier E. Observations pour server a l'histoire clinique du pityriasis rubra pilaire (pityriasis pilaris de Devergie et de Richaud). Ann Dermatol Syphilol 1889;10:253–87.

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: the problem of its classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:140–2.

- Auffret N, Quint L, Domart P, Dubertret L, Lecam JY, Binet O. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:260–1.

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol 1980;5:105–12.

- Batinac T, Kujundzic M, Peternel S, Cabrijan L, Troseli-Vukic B, Petranovic D. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in association with laryngeal carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:e917–19.

- Vitiello M, Miteva M, Romanelli P, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: was it the first manifestation of colon cancer in a patient with preexisting psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:e43–4.

- Stamatis G, Chiolou Z, Stefanaki C, Zakopoulou N, Rigopoulos D, Kontochristopoulos G. Pityriasis rubra pilaris presenting with an abnormal autoimmune profile: two case reports. J Med Case Rep 2009;3:123.

- Frikha F, Frigui M, Masmoudi H, Turki H, Bahloul Z. Systemic sclerosis in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris. Pan Afr Med J 2010;6:6.

- Gül U, Gönül M, Kiliç A, et al. A case of pityriasis rubra pilaris associated with sacroiliitis and autoimmune thyroiditis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:889–90.

- Fuchs-Telem D, Sarig O, van Steensel MA, et al. Familial pityriasis rubra pilaris is caused by mutations in CARD14. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:163–70.

- Li Q, Chung H, Andrews J, et al. CARD14 mutations in familial and sporadic pityriasis rubra pilaris: activation of NF-kappaB. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:S56.

- Mohrenschlager M, Abeck D. Further clinical evidence for involvement of bacterial superantigens in juvenile pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP): report of two new cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2002;19:569.

- Ferrándiz-Pulido C, Bartralot R, Bassas P, et al. Acute postinfectious pityriasis rubra pilaris: a superantigen-mediated dermatosis. Acta Dermosifiliogr 2009;100:706–9.

- Howe K, Foresman P, Griffin T, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:270–4.

- Sonnex TS, Dawber RPR, Zachary CB, et al. The nail in adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a comparison with Sézary syndrome and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15:956–60.

- Allison DS, El-Hazary RA, Calobrisi SD, Dicken CH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:386-9.

- Hong JB, Chiu HC, Wang SH, Tsai TF. Recurrence of classical juvenile pityriasis rubra pilaris in adulthood: report of a case. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:842–4.

- Vanderhooft SL, Francis JS, Holbrook KA, et al. Familial pityriasis rubra pilaris. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:448–53.

- Blasdale C, Turner RJ, Leonard N, Ong EL, Lawrence CM. Spontaneous clinical improvement in HIV-related follicular syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol 2004;29:480–2.

- Griffiths WAD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris – a clinical and laboratory study [MD Thesis]. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1976.

- Abbott RA, Griffiths WAD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris type 1 spontaneously resolving after 20 years. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:378–9.

- Eastham AB, Femia AN, Qureshi A, Vleugels RA. Treatment options for pityriasis rubra pilaris including biologic agents: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150:92–4.

- Petrof G, Almaani N, Archer CB, Griffiths WAD, Smith CH. A systematic review of the literature on the treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris type 1 with TNF-antagonists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e131–5.

- Foo SH, Rowe A, Maheshwari MB, Abdullah A. The challenge of managing pityriasis rubra pilaris: success at last with ustekinumab? Br J Dermatol 2014;171 Suppl. S1:155.

- Feldmeyer L, Hohl D, Gilliet M, Conrad C. Pityriasis rubra pilaris treated with ustekinumab. J Invest Med 2014;62:723.

- Di Stefani A, Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Chiricozzi A, Costanzo A, Chimenti S. Long-term ustekinumab treatment for refractory type I pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Dermatol Case Rep 2013;7:5–9.

- Wohlrab J, Kreft B. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with ustekinumab. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:655–6.

- Eytan O, Sarig O, Sprecher E, van Steesel, MAM. Clinical response to ustekinumab in familial pityriasis rubra pilaris caused by a novel mutation in CARD14. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:420–1.

- Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. Topical treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:675–8.

- Karimian-Teherani D, Parissa M, Tanew A. Response of juvenile circumscribed pityriasis rubra pilaris to topical tazarotene. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:125–6.

- Dicken CH. Treatment of classic pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:997–9.

- Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Mann DJ, Wasserman J, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris sensitive to narrow band ultraviolet B light therapy. J Drugs Dermatol 2009;8:270–3.

- Hofer A, Mullegger R, Kerl H, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for the treatment of erythrodermic pityriasis rubra pilaris. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:475–6.

- Haenssle HA, Bertsch HP, Emmert S, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for the treatment of exanthematic pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol 2004;29:244–6.