CHAPTER 37

Lichen Planus and Lichenoid Disorders

Vincent Piguet1, Stephen M. Breathnach2 and Laurence Le Cleach3

1Department of DermatologyCardiff University; University Hospital of Wales, UK

2St John's Institute of DermatologyGuy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, UK

3Service de DermatologieSatellite Français du Cochrane Skin Group, Hôpital Henri Mondor, France

Definition

Lichenoid disorders are inflammatory dermatoses characterized clinically by flat-topped, papular lesions and histologically by a lymphocytic infiltrate with a band-like distribution in the papillary dermis [1]. Lichen planus is the prototype of lichenoid eruptions, but several skin diseases have a lichenoid tissue reaction and are included here [2, 3]. Graft-versus-host disease, which often presents as a lichenoid eruption, is addressed separately in Chapter 38.

LICHEN PLANUS

Introduction and general description

Lichen planus (LP), the most typical and best characterized lichenoid dematosis, is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease affecting the skin and mucosal membranes, often with a chronic course with relapses and periods of remission. Its prevalence is approximately 0.5% of the population (reviewed in [1]).

Epidemiology

The incidence varies between 0.22% and 1% of the adult population worldwide. LP represented about 1.2% of all new dermatology patients in London and Turin [2], 0.9% in Copenhagen [3] and 0.38% in India [4]. Hypertrophic cases were reportedly to be common in Nigeria [5]. In contrast, oral LP seems to be more frequent with a reported incidence between 1% and 4% of the population [1]. LP is rare in children and commonly affects adults during their fourth to sixth decade. There was an overrepresentation of South Asians in a series of childhood cases in Birmingham, UK [6]. There is no obvious racial predisposition for LP, although a small overrepresentation with patients of Indian subcontinent origin has been suggested at least in oral disease [7]. Familial cases are unusual but have been reported in association with HLA-A3, -A5, -B7, -DR1 and -DRB*0101.

Pathophysiology

Lichen planus is thought to be a T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease, possibly targeting the basal keratinocytes, which can be triggered by a variety of situations, including viruses, drugs and contact allergens.

Immunopathology

The lymphocytic infiltrate of LP is composed of CD8+ T cells with a significant proportion of γ-δ T cells, which is unusual in the skin [1]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies analysing the T-cell receptor genes of the lymphocytes of the inflammatory infiltrate of LP are generally oligoclonal and potentially suggest the presence of autoantigens [2]. Electron microscopy studies and immunohistochemistry of LP demonstrate an increased number of epidermal Langerhans cells [3]. Although autoimmunity is clearly suggested to be central in LP, the exact pathomechanisms are unclear. Gene expression studies of LP have demonstrated an up-regulation of type I interferon-inducible genes and the presence of a specific chemokine signature; CXCL9, the ligand of the receptor CXCR3, was significantly increased in this study [4]. Global genetic studies of microRNAs (miRNA) in LP have revealed dysregulation in a number of miRNAs [5, 6]. Involvement of the Th17 pathway for LP has also been suggested [7]. That LP is thought to be an immunologically mediated disorder [8] is in part due to the fact that a lichenoid eruption may be seen as part of graft-versus-host disease [9–11]. Experimentally, cloned murine autoreactive T cells produce a lichenoid reaction in recipient animals following injection [12]. In LP lesions, T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, accumulate in the dermis, whereas CD8+ T cells infiltrate the epidermis. It has been proposed that CD8+ cytotoxic T cells recognize an antigen (currently unknown) associated with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I on lesional keratinocytes, and lyse them [13–17]. T-cell receptor repertoires are skewed in tissue samples and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with oral LP [2].

The role of chemokines in the pathophysiology of lichenoid tissue reactions has been suggested with regard to recruitment and local activation of cytotoxic TH1 cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells, as well as keratinocytes, express a variety of different chemokines [18–20]. RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted) secreted by T cells may trigger mast cell degranulation with a consequent release of tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which in turn up-regulates lesional T-cell RANTES secretion. Such mechanisms may contribute to the chronicity of T-cell infiltration and clinical disease [21].

Finally, keratinocytes probably contribute to the disease and are also type I interferon producers in LP skin lesions [4]. Keratinocyte-derived cytokines may up-regulate the expression of cell surface adhesion molecules on, and migration by, T cells [22–24]. CD1a+ Langerhans cells and factor XIIIa+ cells are increased in LP [3, 15, 25] and may be involved in antigen presentation to T cells. Activin A – a transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) family member induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and which promotes Langerhans cell differentiation and activation – is increased in the upper epidermis and dermis in LP [26]. Vascular endothelial expression of the adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) is also elevated [15]. Mast cell degranulation [27], and T-cell secretion of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) [28], may contribute to basement membrane disruption, enabling migration of CD8+ T cells into the epithelium. Granzyme B+ T cells have been observed close to apoptotic keratinocytes [29]. Overexpression of bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP-4), another member of the TGF-β family, may contribute to apoptosis of epithelial cells in oral LP through up-regulation of p53, MMP-1 and MMP-3 [30]. Overexpression of MMP-2, membrane type 1 MMP and, especially, MMP-9 may be involved in malignant transformation in oral LP [31]. The role of c-Myc gains and overexpression in malignant transformation has also been established [32]. Myc is a transcription factor that is often dysregulated in cancers. The immune dysregulation and cytokine expression in LP has been reviewed [33].

Causative organisms

Several studies have suggested a role for hepatitis C virus (HCV) in LP, particularly in Japanese and Mediterranean populations [34–39]. This association has also been reported in other countries including the USA, Germany, Italy, Spain and Iran but this is not a consistent observation [40–43]. No association between LP and HCV was detected in France and England or India [44]. The role played by HCV in triggering LP remains unclear. Interestingly, tetramer analysis showed that HCV-specific CD8+ T cells with functional characteristics of terminally differentiated effector cells were identified in close vicinity to HCV (detected by PCR) in lesions of oral LP [45].

Other viruses have been implicated in the pathogenesis of LP, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) [46, 47], human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and HHV-7 [48] and varicella zoster virus [49, 50]. Finally, a number of reports have described the presence of LP after various vaccines. Typically, hepatitis B vaccines have been shown in some patients to trigger LP, often after the second injection of vaccine [51, 52].

Genetics

There may be a genetic susceptibility to idiopathic LP. Familial cases are reported [53–58], and a familial incidence of 10.7% was quoted in one series [56]. LP has also been reported in monozygotic twins [59, 60]. An association with HLA-A3 and HLA-5 has been documented [61], although others found no such association [62, 63], as have associations with HLA-B7 [53], HLA-A28 in Jewish people with LP and carbohydrate intolerance [64], HLA-DR1 [65], HLA-DR10 [66] and HLA-DRB1*0101 [67]. Genetic heterogeneity in LP has led to the suggestion that idiopathic cutaneous, and purely mucosal, LP may each have a different pathogenesis [68]. An association between LP and polymorphisms in CIITA, the MHC class II transactivator, has been reported in a Chinese cohort of LP patients [69]. Another association has been reported between LP and TNF-α gene polymorphisms [70].

Environmental factors

Environmental factors including drugs, contact allergens and others have been potentially associated with LP.

- Drugs. A large variety of drugs has been linked with cutaneous eruptions similar or identical to LP. Often the terms LP-like eruption or lichenoid eruption are used in the context of an adverse drug reaction with features of LP. The list of drugs causing LP and LP-like eruptions has grown steadily and includes several classes, including antimicrobials, antihypertensives, antimalarials, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, diuretics, metals, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and more recently imatinib [71], intravenous immunoglobulin [72], etanercept [72] and adalimumab [73]. These reactions are described in more detail in Chapter 132.

- Dental amalgam. Another putative antigen in oral LP is mercury in dental amalgam [74], however more recent studies do not confirm a clear association between LP and dental amalgam [75].

- Betel nut. Social use of the betel nut is relatively common in India and South-East Asia. The product that is chewed, betel quid, is a mixture of substances, including the areca nut and betel leaf, and is associated with oral LP [76, 77].

- Lichen planus-like contact dermatitis. An LP-like eruption was reported in up to 25% of persons exposed to chemicals found in colour developer. Current automated equipment minimizes contact with these, and LP-like eruptions due to this source are now rare [78]. Two types of reaction were observed – acute (eczematous) and subacute (lichenoid). Patch-test reactions were usually positive to the substituted para-phenylenediamine and were eczematous in nature, but might become lichenoid [79]. LP-like lesions have developed on sites exposed to methacrylic acid esters used in the car industry [78], and more recently from dimethylfumarate, which can be found in sofas [81].

- Miscellaneous. LP has been induced by radiotherapy, and confined to a radiation field [80]. Anxiety, depression and stress are common in patients with LP [83] and may be risk factors for its development [84].

Clinical features

History and clinical presentation

The classic clinical presentation of LP includes primary lesions consisting of firm, shiny, polygonal, 1–3 mm diameter papules with a red to violet colour. More closely, a tracery of thin white lines can be seen on the surface of the lesions, known as Wickham's striae (Figure 37.1) [1]. Papules can be isolated or grouped, in a linear or annular distribution. Typically, a greyish brown pigmentation can be observed in lesions that have resolved due to deposition of melanin in the superficial dermis. Annular lesions are especially common on the penis (Figure 37.2) and rarely may be the predominant type of lesion present, later leading to atrophy [2]. A variant in which groups of ‘spiny’ lesions resembling keratosis pilaris develop around hair follicles (lichen planopilaris) is not uncommon (Figure 37.3). Lichen planopilaris more often forms only a minor feature of the disease, but occasionally this type of lesion may predominate. Co-localization of LP and vitiligo has been reported [3]. LP can affect any part of the body surface, but is most often seen on the volar aspect of the wrists (Figure 37.4), the lumbar region and around the ankles. The ankles and shins are the commonest sites for hypertrophic lesions. When the palms and soles are affected, the lesions tend to be firm and rough with a yellowish hue (Figure 37.5) [4]. A rare, erosive, flexural variant of LP has been described [5]. Linear LP occurring on Blashko's lines can also be observed [6]. Isolated lesions of LP have been reported to involve one or both eyelids [7, 8] or the lips [9–11]. Milia have been recorded in LP [12], and LP was reported as confined to the site of radiation therapy site in one patient [13].

Figure 37.1 Lichen planus. Close up to show Wickham's striae.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Figure 37.2 Lichen planus showing annular lesion on the shaft of the penis.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Figure 37.3 Lichen planopilaris showing hyperpigmented, follicular, ‘plugged’ lesions in the frontal scalp hairline.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Figure 37.4 Lichen planus. Classic eruption on the volar aspect of the wrist.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Figure 37.5 Lichen planus of the palms and feet showing hyperkeratosis and a yellow colour.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Mucous membrane lesions are very common, occurring in 30–70% of cases, and may be present without evidence of skin lesions. They are, however, much less common in black people. The buccal mucosa and tongue are most often involved, but lesions may be found around the anus, on the genitalia, in the larynx and, very rarely, on the tympanic membranes or even in the oesophagus. White streaks, often forming a lacework, on the buccal mucosa are highly characteristic (Figure 37.6). They may be seen on the inner surface of the cheeks, on the gum margins or on the lips. On the tongue, the lesions are usually in the form of fixed, white plaques, often slightly depressed below the surrounding normal mucous membrane, especially on the upper surface and edges (Figure 37.7). Ulcerative lesions in the mouth are uncommon, but may be the site of epitheliomatous transformation (Figure 37.8). There may be striking pigmentation of oral LP in darkly pigmented races [14]. Diabetes is a possible associated disease of oral LP [15, 16], and candidiasis may coexist with LP in some patients.

Figure 37.6 Lichen planus on the buccal mucosa showing a lacework of white streaks.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Figure 37.7 Lichen planus of the tongue showing irregular, fixed, white plaques.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Figure 37.8 Erosive lichen planus of the buccal mucosa.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Pruritus is a fairly consistent feature in LP and ranges from occasional mild irritation to more or less continuous, severe itching, which interferes with sleep and makes life almost intolerable; occasionally, pruritus is completely absent. Hypertrophic lesions usually itch severely. Paradoxically, there is seldom evidence of scratching, as the patient tends to rub to gain relief. Itching at sites without visible skin lesions can occur. Burning and stinging are less common complaints. In the mouth, the patient may complain of discomfort, stinging or pain; ulcerated lesions are especially painful. Great discomfort may be caused by hot foods and drinks.

Clinical variants

Lesions confined to the mouth, or with minimal accompanying skin involvement, are not uncommon [1–6], and account for about 15% of all cases. Mucosal lichen sclerosis/lichen planus overlap syndrome can also be observed [1]. The prevalence of oral LP was 1.5% among the villagers of Kerala in southern India [7], possibly related to chewing tobacco, and ranges between 0.5% and 2.2% in other epidemiological studies [2, 8]. The lesions do not differ from those found in connection with skin lesions, but, being confined to the mouth, may lead to great difficulty in diagnosis. They are often referred first to a dental surgeon. Distinct clinical subtypes such as reticular, atrophic, hypertrophic and erosive forms are well recognized, and more than one type may be present [2]. On the tongue and buccal mucosa, lesions are most likely to be mistaken for leukoplakia and on the gum margin for gingivitis or chronic candidiasis; the latter may coexist. Other conditions that must be excluded are ‘smoker's patches’, which characteristically involve the palate, and white-sponge naevi, in which the mucous membrane is thickened, irregularly folded and feels soft to the touch. These occur mainly on the floor of the mouth and histologically many of the prickle cells in the epidermis are vacuolated. It is important to bear in mind the possibility of a lichenoid drug reaction in patients with oral lichenoid changes (see Chapter 110). Oral lichenoid reactions may be asymmetrical on the buccal mucosa and occur adjacent to dental amalgam fillings. If patch testing reveals mercury allergy, changing to another type of filling may prove beneficial [9–14]. Very occasionally, LP lesions extend to the larynx or oesophagus [15–19]. Oesophageal LP may result in dysphagia and the formation of benign strictures.

In young men, the lesions of LP are sometimes restricted to the genitalia and/or mouth [20, 21]. Genital lesions, which are usually characteristic, may be present on the penile shaft (see Figure 37.2), glans penis, prepuce or scrotum. Ulceration is very unlikely, and syphilis can usually be excluded without difficulty. The presence of buccal mucosal lesions will usually confirm the diagnosis. Circumcision may be helpful in clearing up LP [20].

Lesions on the female genitalia are fairly common [22–29]; they may occur alone, be combined with lesions in the mouth only, or be part of widespread involvement. The clinical presentation of LP of the vulva spans a spectrum from subtle, fine, reticulate papules to severe erosive disease accompanied by dyspareunia, scarring and loss of the normal vulvar architecture. The condition should be distinguished from lichen sclerosus or leukoplakia, but this may be difficult when there is coexisting atrophy or vaginal stenosis. Diagnostic criteria have been proposed recently [30] and include well-demarcated erosions/erythematous areas at the vaginal introitus, the presence of a hyperkeratotic border to lesions and/or Wickham's striae in the surrounding skin, symptoms of pain/burning, scarring/loss of normal architecture, the presence of vaginal inflammation and the involvement of other mucosal surfaces. Histologically, a well-defined inflammatory band involving the dermal–epidermal junction and consisting predominantly of lymphocytes and signs of basal layer degeneration are seen. The association of erosive LP of the vulva and vagina with desquamative gingivitis has been termed the vulvo-vaginal–gingival syndrome (Figure 37.9) [21, 22]. Coexisting vulval lichen sclerosus and lichenoid oral lesions have been described [31].

Figure 37.9 Vulvo-vaginal–gingival syndrome showing (a) vulvitis and (b) gingivitis in the same patient.

(Courtesy of Dr S. Neill, St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Lichen planopilaris

Follicular lesions usually appear during the course of typical LP, but occasionally they predominate and diagnosis may then be difficult. An absence of arrector pili muscles and sebaceous glands, a perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate in the reticular dermis and mucinous perifollicular fibroplasia within the upper dermis with an absence of interfollicular mucin, and superficial perifollicular wedge-shaped scarring are all characteristic features of the histology [1]. Presentation with alopecia of the trunk is recorded [2]. Follicular lesions occurring in the scalp are accompanied by some scaling and are likely to lead to a scarring alopecia (Figure 37.10). Very rarely, the scalp alone is involved. The so-called Graham Little–Piccardi–Lassueur syndrome comprises the triad of multifocal scalp cicatricial alopecia, non-scarring alopecia of the axillae and/or groin, and keratotic lichenoid follicular papules [3–8]. The clinical, histological and immunofluorescence overlap between this syndrome and LP with follicular involvement (lichen planopilaris) suggest that both are variants of LP. Follicular LP must be distinguished by biopsy from keratosis pilaris, Darier disease, follicular mucinosis, lichen scrofulosorum and, in the scalp, from lupus erythematosus.

Figure 37.10 Lichen planus of the scalp leading to large areas of cicatricial alopecia.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a scalp condition that affects elderly women in particular and frequently involves the eyebrows. It has been regarded by some authors as a clinically distinct variant of lichen planopilaris [9] but is considered by most to be a variant [10], and is certainly associated with mucocutaneous LP [11, 12].

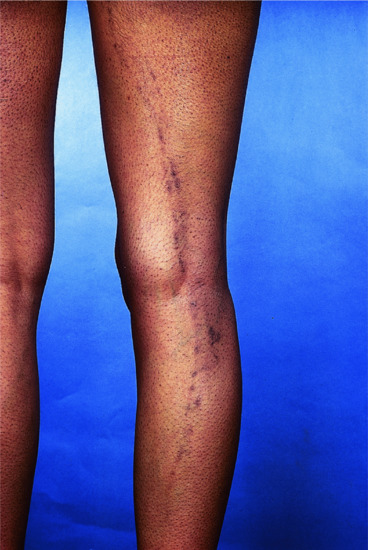

Hypertrophic lichen planus

This usually develops during the course of a subacute attack, but occasionally only hypertrophic or warty lesions are found. They most often occur on the lower limbs, especially around the ankles; venous stasis has been put forward as an explanation (Figure 37.11). The development of hypertrophic lesions greatly lengthens the course of the disease, as they may persist for many years. When such lesions eventually clear, an area of pigmentation and scarring may remain and there is often some degree of atrophy. They must be distinguished from lichen simplex chronicus and lichen amyloidosus (papular). Multiple cutaneous horns overlying hypertrophic LP are recorded [1], as are keratoacanthoma [2, 3] and malignant transformation [4–6] arising in hypertrophic LP, as well as metastatic squamous cell cancer [7].

Figure 37.11 Hypertrophic lichen planus of great chronicity occurring on the lower leg and ankle.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Lichen planus of the palms and soles

Although lesions on the volar aspect of the wrists or at the ankles occur in more than 50% of cases of LP, lesions on the adjacent palms and soles are less common, lack the characteristic shape and colour of lesions elsewhere, and are firm to the touch and yellow in hue (see Figure 37.5) [1]. They may be broadly sheeted or show up as punctate keratoses [2]. Vesicle-like papules are recorded [3]. Itching may be absent. When such changes occur in isolation, diagnosis is very difficult; syphilis, psoriasis, callosities and warts must be excluded.

A rare, very chronic form of LP involves large, painful, indolent ulcers on the sole of one or both feet [4], with gradual, permanent loss of the toenails; there may be secondary webbing of the toes [5]. The sole may resemble lichenified dermatitis or psoriasis rather than LP before the ulcers appear. The onset is insidious and there may be no other evidence of LP, although cicatricial alopecia has been associated in some cases.

Actinic lichen planus

‘Actinic’ or (sub)tropical LP generally occurs in children or young adults with dark skin living in tropical countries; virtually all cases originate from the Middle East, East Africa or India [6–10]. Lesions occur on exposed skin (usually the face) as well-defined annular or discoid patches, which have a deeply hyperpigmented centre surrounded by a striking hypopigmented zone (Figure 37.12). Erythematous actinic LP has been associated with oral erosive LP and chronic active hepatitis [11]. Sunlight exposure appears to be central to the pathogenesis of actinic LP [12], although evidence for photo-induction of lesions in actinic LP is still lacking [13]. Actinic LP may mimic melasma [14]. There is a histological spectrum comprising: a form with features of classic idiopathic LP; an intermediate form (lichenoid melanodermatitis) with foci of spongiosis and parakeratosis; and a more overtly eczematous type [15]. All share striking pigmentary incontinence. Some of these ‘hybrids’ of actinic LP may not be mere variants of LP.

Figure 37.12 Lichen planus actinicus showing well-defined, pigmented, nummular patches on the face.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Lichen planus pigmentosus

This is a pigmentary disorder seen in India or in the Middle East, which may or may not be associated with typical LP papules [16–18]. The macular hyperpigmentation involves chiefly the face, neck and upper limbs, although it can be more widespread, and varies from slate grey to brownish black. It is mostly diffuse, but reticular, blotchy and perifollicular forms are seen [3, 18]. The duration at presentation ranged from 2 months to 21 years in one series [18]. Occasionally, there is a striking predominance of lesions at intertriginous sites, especially the axillae [19, 20]. The mucous membranes, palms and soles are usually not involved, but involvement of mucous membranes has been observed [21]. LP pigmentosus has been anecdotally reported in association with acrokeratosis of Bazex [22].

Annular lichen planus

Although small annular lesions are common in LP, cases showing a few large annular lesions only are unusual. They may be widely scattered, and usually have a very narrow rim of activity and a depressed, slightly atrophic centre (Figure 37.13) [23]. Much less often, the margin is wide and the central area is quite small. Annular lesions are characteristically found on the penis (see Figure 37.2), sometimes associated with lesions on the buccal mucosa. The differential diagnosis includes granuloma annulare. A distinct entity termed annular lichenoid dermatitis of youth [2, 3, 24, 25] has been described, characterized by persistent, asymptomatic erythematous macules and round, annular patches with a red-brownish border and central hypopigmentation, mostly distributed on the groin and flanks, in children and adolescents. Histology reveals a lichenoid dermatitis with necrosis/apoptosis of the keratinocytes limited to the tips of rete ridges.

Figure 37.13 Annular lichen planus.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.)

Guttate lichen planus

Lesions are widely scattered and remain discrete, may be all small (1–2 mm across), or larger (up to 1 cm), and individual lesions seldom become chronic (Figure 37.14). Guttate psoriasis must be excluded as a differentiatial.

Figure 37.14 Guttate lichen planus.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Acute and subacute lichen planus with a confluence of lesions

In these forms, small lesions are widely distributed; where they become confluent, eczema may be simulated. Colour changes may be marked, with individual lesions initially red but progressing rapidly to black as they fade. Successive crops may occur, such that the total time for clearance may be little different from other forms. A small minority clear in under 3 months. Differential diagnosis includes pityriasis rosea in the earliest phase, and eczema later; drug-induced lichenoid eruptions may present in this fashion.

‘Mixed’ lichen planus/discoid lupus erythematosus disease patterns

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and LP are usually considered as distinct entities with characteristic clinical, histopathological and immunopathological features, with basement membrane deposition of IgG in DLE [1, 2]. However, similarities between LP and DLE have been noted. In addition, there have been several reports of patients showing overlapping features of both disorders [3–8]. Chronic atrophic DLE-like lesions on the head, neck and upper trunk may accompany reticular white lesions in the oral cavity, and combinations of lichenoid or verrucous lesions are seen. Eyelid involvement is recorded [9]. The association of extensive generalized LP with subacute cutaneous DLE has also been documented [10].

Bullous lichen planus and lichen planus pemphigoides

Lichen ruber pemphigoides was first described by Kaposi in 1892. Bullous LP and LP pemphigoides were in the past differentiated solely on clinical and histological criteria [1], but can now be differentiated using immunofluorescence (IMF) procedures and immunoelectron microscopy. In bullous LP, blisters arise only on or near the lesions of LP, as a result of severe liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer [3]. Histologically, there is subepidermal bulla formation with typical changes of LP, and direct and indirect IMF are negative [2, 3]. The eruption is usually only of short duration [2]. In LP pemphigoides the LP tends to be acute and generalized and is followed by the sudden appearance of large bullae on both involved and uninvolved skin (Figure 37.15) [4–7]. Occasionally, even in LP pemphigoides, blisters may arise only on the lesions of LP [8]. LP pemphigoides has been precipitated by psoralen and UVA (PUVA) [9] and has evolved into pemphigoid nodularis [10]. An LP pemphigoides-like eruption has been reported to overlap with paraneoplastic pemphigus [11, 12]. In LP pemphigoides, the histology shows a subepidermal bulla with no evidence of associated LP [2]. Direct IMF shows linear basement membrane zone deposition of IgG and C3 in perilesional skin [2, 7]. Immunoelectron microscopic studies reveal deposition of IgG and C3 in the base of the bulla and not in the roof as found in bullous pemphigoid [13].

Figure 37.15 Lichen planus pemphigoides showing large bulla arising on and around the vicinity of lichen planus around the ankle.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Immunoblotting data have revealed that circulating autoantibodies in LP pemphigoides react with an epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of bullous pemphigoid 180 kDa antigen, and also with a 200 kDa antigen detected in bullous pemphigoid [14–18]. It seems that epidermal damage from liquefaction degeneration in LP exposes basement membrane antigens, and a consequent stimulation of autoantibody production. The mean age of patients with LP pemphigoides is lower than that of those with classic bullous pemphigoid, and the course of the disease also tends to be less severe.

Lichen nitidus

Lichen nitidus is a rarer condition than idiopathic LP and is characterized clinically by the presence of pinpoint to pinhead-sized papules, which are usually asymptomatic and flesh-coloured, with a flat, shiny surface. The view that lichen nitidus represents a variant of LP tends to be supported by the fact that early, tiny LP papules may be clinically and histopathologically indistinguishable from lichen nitidus. Immunophenotypic studies also reinforce the association between LP and lichen nitidus [1]. However, some authors favour a separation into two dermatoses because of histopathological differences, or differences in cytokine expression in lichen nitidus [2].

Typical lichen nitidus papules are minute, pinpoint to pinhead sized, and have a flat or dome-shaped, shiny surface. They usually remain discrete, although they may be closely grouped (Figure 37.16). They are found on any part of the body but the sites of predilection are the forearms, penis (Figure 37.17), abdomen, chest and buttocks. The eruption is sometimes generalized [3, 4]. When the palms or soles are involved the changes can be those of a confluent hyperkeratosis resembling chronic fissured eczema, or there may be multiple, distinctive, minute papules [5, 6]. On the palms, the minute papules can become purpuric and may occasionally resemble pompholyx. Such cases may lack lesions of lichen nitidus elsewhere, so a biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis [5, 7].

Figure 37.16 Lichen nitidus showing a close-up of aggregated, pinhead-sized papules.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Figure 37.17 Lichen nitidus showing aggregates of pinhead-sized papules on the shaft of the penis.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Linear lichen nitidus has been described, but is exceptionally rare [8]. The development of lesions along scratch marks is not uncommon. The lesions are flesh coloured or reddish brown. Although intense pruritus can occur [4], the lesions are generally quite symptomless. Nail pitting may coexist with lichen nitidus [9], or the affected nails may appear rough due to increased linear striations and longitudinal ridging [5, 10]. An actinic variant has been documented [11]. Mucous membrane lesions occur occasionally and are much rarer than in LP. Lichen nitidus must be distinguished from lichen scrofulosorum [12], where there are follicular papules grouped in small patches on the trunk, and from keratosis pilaris, where there are horny follicular papules mainly on the extensor surface of the limbs. In cases of doubt, a biopsy usually clarifies the diagnosis. Lichen nitidus has been described in association with Crohn disease, trisomy 21, congenital megacolon [13] and Niemann–Pick disease type B [14].

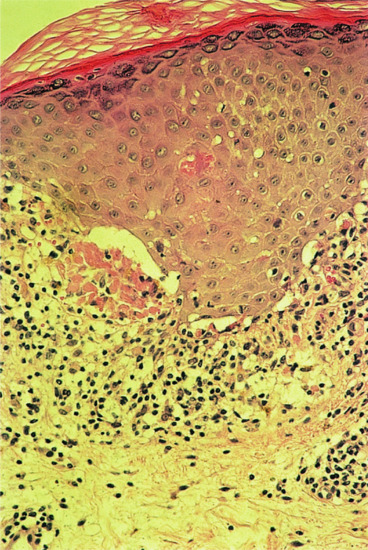

Surprisingly, direct IMF studies in lichen nitidus have given negative results [15, 16]. However, ultrastructural studies have shown identical changes in lichen nitidus and LP [15]. The histology of a typical papule is characteristic. The papule is formed by an intense infiltrate situated immediately below the epidermis and is well circumscribed. The infiltrate consists of lymphocytes and histiocytes and there are often a few Langhans giant cells (Figure 37.18). Sometimes, plasma cells are numerous in the infiltrate [17]. The overlying epidermis is flattened and sometimes there is liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer. The rete ridges at the margin of the infiltrate are elongated and tend to encircle it. Although tuberculoid in appearance, true tubercle formation or caseation never occurs. The histology of a palmar lesion may show a deep parakeratotic plug, which distinguishes it from the palmar lesions of LP [7]. Perifollicular granulomas can occur in spinous and follicular lichen nitidus, which may simulate lichen scrofulosorum [12]. Perforating lichen nitidus has also been described [18]. In its characteristic monomorphic form, lichen nitidus is rare, but lesions of lichen nitidus occurring in association with LP are more common. The age incidence tends to be lower than that of LP. Most cases occur in children or young adults. Familial lichen nitidus has rarely been observed [19].

Figure 37.18 Lichen nitidus. Typical histology showing the focally dense infiltrate containing a few giant cells. Magnification 100× (H&E).

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Nékam disease

The variety of synonyms used implies that there is no complete consensus of agreement about this rare disorder. The great majority of cases are adults between the ages of 20 and 40 years [1], although children are occasionally affected [2]. Nékam disease is characterized by violaceous, papular and nodular lesions typically arranged in a linear and reticulate pattern (Figure 37.19), most marked on the extremities and buttocks, and accompanied by a seborrhoeic dermatitis-like eruption on the face. Nékam's original case was also associated with palmoplantar keratoderma. The individual lesions are erythematous verrucous papules covered by a hyperkeratotic plug that can only be removed with difficulty, revealing irregular indentations and prominent capillary loops [1, 3]. In extensive Nékam disease, the lesions tend to be symmetrical bilaterally, mainly involving the antecubital fossae, extensor forearms, lumbosacral area and buttocks, posterior thighs, popliteal fossae and less commonly the oral cavity and genitalia. Oral manifestations occur in 50% of patients – recurrent aphthous ulcers, larger chronic ulcers or erythrokeratotic papules being the commonest oral features [4]. The nails can become thickened, longitudinally ridged and prone to paronychia [5]. Cases have followed trauma [6] and erythroderma [7]. A limited variant of Nékam disease presenting with erythematous hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on the face, clearing in the summer months, has been described in two young siblings [8]. Histologically, changes are often non-specific and consistent with a chronic dermatitis, but lichenoid features can be seen [1, 3]. Some authors believe that the condition is an unusual variant of LP [1], while others consider it to be a distinct entity [9]. A case of Nékam disease associated with porokeratotic histology and amyloid deposition may also point against the view that Nékam disease is a subset of LP [10]. A possible association of Nékam disease with glomerulonephritis and lymphoproliferative disorders has been commented on [4].

Figure 37.19 Nékam disease. Reticulate keratotic erythematous papules on (a) the volar aspect of the wrist and (b) the dorsum of the hand.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Complications

Hair

Alopecia is uncommon in LP, but most often occurs in small areas on the scalp, producing patches of atrophic cicatricial alopecia (see Figure 37.10) [1–5]. It results from follicular destruction by the inflammatory infiltrate, with scarring. Areas of alopecia may continue to appear, or to extend, for months after the skin lesions have faded. The final result is one of pseudopelade [2, 5]; this is probably best considered as a distinct clinical entity due to a number of independent conditions, of which LP is only one. Lichen planopilaris is more common in women and about half will develop involvement of the glabrous skin, mucous membranes or nails [1]; it may occur in children [3]. Tumid forms of LP follicularis have been described in which clusters of milium cysts and comedones develop [6]. LP pilaris has been reported in association with dermatitis herpetiformis [7].

Nails

Nail involvement occurs in up to 10% of cases, but is usually a minor feature of the disease [8, 9]. The majority of cases present during the fifth or sixth decades. Long-term permanent damage to the nails is rare [10]. Fingernails are more frequently affected than toenails [10], with initial involvement of two or three fingernails before subsequent involvement of the remaining digits. The most common changes are exaggeration of the longitudinal lines and linear depressions due to slight thinning of the nail plate (Figure 37.20). These changes usually occur in the context of severe generalized LP, although skin lesions may not be seen in the vicinity of the affected nail. Elevated ridges may be seen on the nail [9]. Adhesion between the epidermis of the dorsal nail fold and the nail bed may cause partial destruction of the nail (pterygium unguis) (Figure 37.21a). Rarely, the nail is completely shed; there is usually clinical evidence of LP at the base of the nail before shedding. Nails may partially regrow or be permanently lost (Figure 37.21b); the nails of the great toes are the ones most often affected. LP has been shown to cause childhood idiopathic atrophy of the nails [11]. LP of the nails in childhood is rare [12] but may overlap with the condition of twenty-nail dystrophy of childhood (idiopathic trachyonychia); the exact relationship is unclear [13–18]. The rare variant of LP that causes ulceration of the soles is often accompanied by permanent destruction of several toenails. LP of the nail bed may give rise to longitudinal melanonychia [19], hyperpigmentation, subungual hyperkeratosis or onycholysis [9], or changes mimicking the yellow nail syndrome [20, 21].

Figure 37.20 Lichen planus of the thumbnail showing thinning of the nail plate and longitudinal lines.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Figure 37.21 (a) Severe lichen planus of the fingernails showing involvement of the nail fold areas and early pterygium formation.

(Courtesy of the Welsh Institute of Dermatology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.) (b) Severe, destructive lichen planus of the toenails. (Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Mucous membranes

Squamous cell carcinoma developing on oral lesions is uncommon but is a potential danger, especially with ulcerated lesions [22–30], although the incidence varies greatly in different series. Lesions may occur on the lip (Figure 37.22), the buccal mucosa or the gum margin. It has been postulated that the high expression of cyclo-oxygenase 2 reported in oral LP may be of aetiological significance in the development of squamous cell carcinoma [31]. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on cutaneous lesions of LP [32] and ano-genital lesions [33–35] is definitely a rare phenomenon. Cicatricial conjunctivitis [36] and lacrimal canalicular obstruction are recorded [37].

Figure 37.22 Squamous carcinoma on the lower lip developing at the site of lichen planus cheilitis.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Associated conditions

Idiopathic LP has been reported in association with diseases of altered or disturbed immunity, including ulcerative colitis [1–3], alopecia areata [3, 4], vitiligo [3], dermatomyositis [5], morphoea and lichen sclerosus [6], systemic lupus erythematosus [7, 8], pemphigus [7] and paraneoplastic pemphigus [9, 10]. In addition, LP has been observed in association with thymoma [4, 7, 11, 12], hypothyroidism [13], myasthenia gravis [2, 3, 12], hypogammaglobulinaemia [4, 5, 14], primary biliary cirrhosis [15–17], especially in those treated with penicillamine, and primary sclerosing cholangitis [18]. The literature with regard to LP and HCV infection is reviewed in the section on pathogenesis. In Italy, possibly because of a higher prevalence of HBV and HCV infection, patients with LP seem more prone to develop liver disease, including chronic active hepatitis [19, 20]. A high prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies has been documented in patients with HCV-associated oral LP [21]. Elsewhere, the association between LP and chronic active hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis is unusual and probably coincidental [22–24]. Overall, the majority of patients with LP live to old age, despite an association with autoimmunity [25].

LP has also been associated with diabetes [26]. Anecdotally, LP has occurred in patients with Castleman tumours (giant lymph node hyperplasia) [27] or with generalized lichen amyloidosus [28]. LP has been described in certain tattoo reactions, particularly in those areas where there is coexisting mercury hypersensitivity to the injected dye [29, 30].

Disease course and prognosis

Although a few cases evolve rapidly and clear within a few weeks, the onset is usually insidious. In most cases, the papules eventually flatten after a few months, often to be replaced by an area of pigmentation that retains the shape of the papule and persists for months or years. There may be a gradual change in colour from pink to blue to black. The residual pigmentation may be intense, especially in dark-skinned races, or almost imperceptible in fair-skinned individuals. New papules may form while others are clearing. Some papules persist much longer, enlarge and thicken, and develop a roughened surface with a prominent violaceous hue – so-called hypertrophic LP. Such lesions may resolve with atrophy or scarring. More warty lesions are seen occasionally. Areas of pigment loss are described in black South Africans.

Investigations

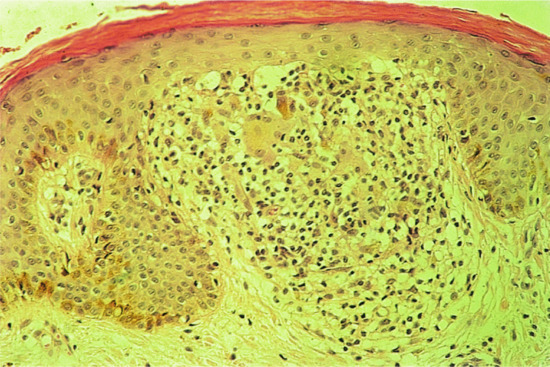

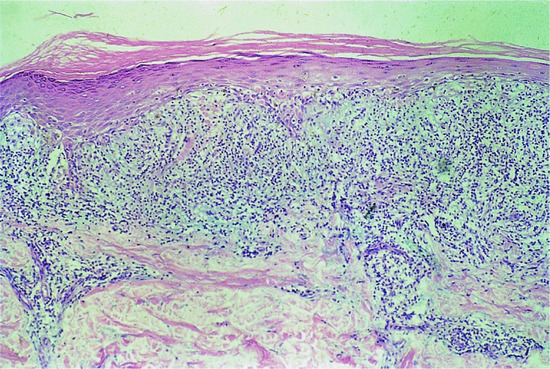

Histology is the most useful investigation to confirm a diagnosis of LP. More recently, the use of dermoscopy has been assessed and found useful in some cases when Wickham's striae can be visualized better with the device (Figure 37.23) [1]. Typical features of dermoscopy images of LP include a network of whitish striae with red globules at the periphery [1, 2]. Histology will be routinely obtained to confirm the diagnosis of LP [3, 4]. The earliest finding is an increase in epidermal Langerhans cells [3], associated with a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, impinging on the dermal–epidermal junction (DEJ). Mild spongiosis is followed by vacuolar alteration and clefting along the DEJ, with accumulation of necrotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) [5]. The characteristic histological changes are best seen in biopsies of fully developed LP papules (Figure 37.24) [6]. The centre of the papule shows irregular acanthosis of the epidermis, irregular thickening of the granular layer and compact hyperkeratosis. The mid-epidermal cells appear larger, flatter and paler than usual [6]. In oral LP, epithelial proliferation is increased [7]. Parakeratosis is rarely found in idiopathic LP, in contrast to some drug-induced lichenoid tissue reactions. A focal increase in thickness of the granular layer and infiltrate corresponds to the presence of Wickham's striae [8]. Degenerating basal epidermal cells are transformed into colloid bodies (15–20 μm diameter), which appear singly or in clumps [9–11]. The rete ridges may appear flattened or effaced (‘saw-tooth’ appearance), and focal separation from the dermis may lead to Max Joseph spaces (Figure 37.25). In older or hypertrophic lesions, the number of colloid bodies is considerably reduced. In ‘active’ LP, a band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, rarely admixed with plasma cells [12, 13], obliterates the DEJ. Epidermal melanocytes are absent or considerably decreased in number [6], while pigmentary incontinence with dermal melanophages is characteristic. When the disease is becoming inactive, the infiltrate, with melanophages, becomes sparser and is arranged around papillary blood vessels, which may show ectasia and surrounding fibroplasia.

Figure 37.23 Dermoscopy image of lichen planus with typical Wickham's striae.

(Courtesy of Dr Alan Cameron, School of Medicine, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.)

Figure 37.24 Typical histology of lichen planus. Magnification 40× (H&E).

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

Figure 37.25 Lichen planus: photomicrograph to show clumps of cytoid bodies. Magnification 100× (H&E).

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

In hypertrophic LP, the epidermis may show a pseudoepitheliomatous appearance with extreme irregular acanthosis. Follicles may be expanded and at times have a cyst-like appearance. The infiltrate may not appear very band-like, but serial sections will usually show foci of basal cell liquefaction and colloid body formation, often around the follicular epithelium. Longstanding cases usually demonstrate coexistent dermal fibrosis adjacent to the inflammatory changes.

In atrophic LP, the epidermis may be greatly thinned almost to the level of the granular layer, although relatively compact hyperkeratosis remains. The rete ridges are usually completely effaced with relatively few colloid bodies. The papillary dermis shows fibrosis and loss of elastica.

In follicular lesions, an infiltrate extends around, and may permeate, the base of the hair follicle epithelium, with follicular keratin plugging (Figure 37.26) [14, 15].

Figure 37.26 Lichen planus: photomicrograph of a follicular lesion. (a) Scanning view. Magnification 20× (H&E). (b) At higher power. Magnification 40× (H&E).

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

In mucosal LP, the epithelium is usually thinned with parakeratosis, although both types of keratinization may be seen [16, 17]. The epithelium may resemble epidermis from the skin, plasma cells may be prominent in the band-like infiltrate, and colloid bodies are fewer than in typical cutaneous papular LP. The erythematous subtype of oral LP is associated with increased cell proliferation compared with the reticular form [18]. Moderate or severe epithelial dysplasia on oral biopsy should probably be regarded as an increased risk for subsequent cancer development [19].

Bullous LP is rare. Blister formation takes place predominantly between the basal lamina and the cytomembranes of basal keratinocytes (i.e. intrabasal) [9], such that there is a wide separation between the epidermis and infiltrate.

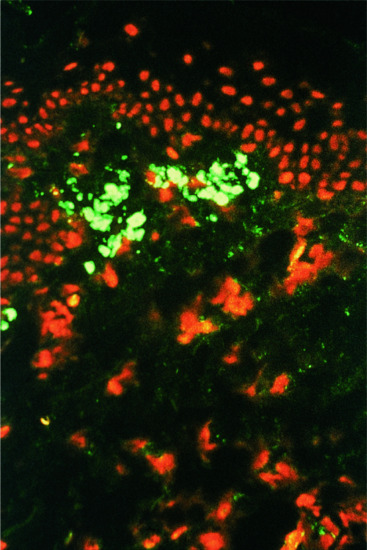

Direct immunofluorescence shows globular deposits of immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 37.27) and occasionally IgG and IgA, representing apoptotic keratinocytes, around the DEJ and lower epidermis, with fibrin deposition at the region of the DEJ [16, 20]. Direct IMF studies may be useful in differentiating LP from lupus erythematosus or LP pemphigoides [21, 22], and can be carried out on routine histological material (23).

Figure 37.27 Lichen planus: photomicrograph of direct immunofluorescence showing the bright fluorescence of cytoid bodies with anti-IgM. Magnification 100×.

(Courtesy of St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, UK.)

A clinicopathological study of lichenoid dermatitis concluded that it was usually possible to provide a specific diagnosis [24]. Occasionally, lichenoid dermatitis can become generalized and clinically mimic an exfoliative dermatitis; such eruptions are usually triggered by drugs.

Benign lichenoid keratoses are usually solitary but may be multiple [25–27], and show characteristic lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes, occasional parakeratosis, and apoptotic bodies in the epidermis without nuclear atypia of keratinocytes. Rarely, the histology may show features of mycosis fungoides [28]. Melanoma may be associated with a lichenoid tissue reaction [29], and melanoma in situ with lichenoid regression may mimic a benign lichenoid keratoses histologically [30].

Management

Treatment of LP can represent a challenge and depends on the localization, clinical form and severity [1]. For cutaneous LP, which can clear spontaneously within 1–2 years, the aim of treatment is to reduce pruritus and time to resolution [2]. Therapeutic abstention is recommended for asymptomatic oral LP. However, painful, erosive LP may need aggressive and long-term treatments [3]. Nail or scalp involvement [4, 5], which may induce scars, genital LP [6] and oesophageal and conjunctival involvement, which may induce strictures and fibrosis, may require rapid treatment to avoid scaring or avoid a fatal course.

The main therapy for LP is corticosteroids. Overall, the level of evidence for treatments used in LP is low [7]. Surprisingly, there is still little evidence for the efficacy of topical or systemic corticosteroids, commonly recommended as first line treatment for LP. Treatment is mainly based on clinical experience. In contrast, for oral LP, there are several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one Cochrane review [7–9]. However, the majority of these trials are small, have used various outcomes and are at high risk of bias. For cutaneous LP, there are only a few small RCTs. No RCT has assessed treatment for genital or nail LP, lichen planopilaris or other lichenoid disorders.

Cutaneous lichen planus

The goals of therapy are to improve itching and reduce time to resolution of the lesions.

First line

Topical corticosteroids are the first line treatment for limited cutaneous LP. The use of very potent corticosteroids is required (clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%) once daily at night until remission. If no evolution is observed after 6 weeks, second line therapy has to be considered. After remission, the optimal length of maintenance therapy is unknown and will be adapted to each patient. For hypertrophic LP, very potent corticosteroids need to be applied under an occlusive bandage. Oral corticosteroids are the first line treatment for widespread cutaneous LP: prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg per day until improvement (usually 4–6 weeks). In a small RCT in which potent corticosteroid cream alone was compared with oral prednisolone (30 mg per day for 10 days) combined with topical corticosteroids, the time to clearing was significantly shorter in the oral prednisolone group (18 weeks versus 29 weeks) than in the topical steroid cream only group. Two patients in the corticosteroid group experienced a severe relapse after treatment withdrawal [10]. After remission, oral corticosteroids should be tapered down slowly.

Second line

An RCT showing a rate of regression or remission at 8 weeks significantly higher with acitretin (30 mg per day for 8 weeks) than with placebo has been published [11]. Considering the side effects of teratogenicity and mucocutaneous dryness, acitretin is used as second line therapy in cutaneous LP. Another second line option is photochemotherapy or phototherapy. In a small trial, PUVA used three times weekly on one side of the body was compared with no treatment on the other side of the body. Clearance was observed on the treated side only in 50% of the patients [12]. In a retrospective series, clearance within a mean of 3 months was observed in 70% of patients treated with narrow-band UVB therapy (13). PUVA phototherapy may also be combined with acitretin but evaluation of this association has not been assessed. Phototherapy can increase the risk of residual hyperpigmentation in dark-skinned patients. Oral corticosteroids in combination with phototherapy are also a possible second line therapy.

Third line

The best level of evidence for methotrexate in cutaneous LP is a prospective series. A complete remission was observed in 14/24 patients at 24 weeks [14]. However, by analogy with other cutaneous diseases, methotrexate can be used as third line treatment for generalized LP. There are four RCTs assessing griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine or sulfasalazine [15–17]. Because of risk of bias in these trials, discrepancies of results between studies for griseofulvin and life-threatening adverse reaction for sulfasalazine, these treatments are not recommended in cutaneous LP.

Oral lichen planus

The aims of treatment are to heal erosive lesions in order to reduce pain and permit normal food intake. Education of the patient should emphasize that oral LP frequently has a chronic course marked by treatment-induced remission followed by relapse [4, 7]. Considering the potential higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma, the need for regular clinical surveillance on a long-term basis has also to be explained [18]. Alcohol and tobacco should be avoided as well as spicy or acidic foods and drinks. Good oral hygiene and professional dental care are recommended.

First line

Topical corticosteroids are the first line treatment for symptomatic oral LP. In two small RCTs comparing topical corticosteroids, higher cure rates were observed in the topical corticosteroids group (80% versus 30% with fluocinonide and 66% vsersus 18% with betamethasone) [19, 20]. In the absence of specific available formulation for oral lesions, super-potent corticosteroids (0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment) can be applied three times daily with a gloved finger on erosive lesions. It is recommended to not drink or eat for 1 h after the application. Alternatively, for widespread, less severe lesions or maintenance therapy, a patient can use a soluble prednisolone tablet 5 mg dissolved in 15 mL water for a mouthwash swish and rinse three times daily. Oral candidiasis is the most frequent complication of this treatment [21]. If no improvement is observed after 6 weeks, second line therapy has to be considered. After remission, the optimal length of maintenance therapy is unknown and should be adapted to each patient. In severe case of erosive LP associated with important eating difficulties and eventual weight loss, first line therapy is oral corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/day) until remission, generally 4–6 weeks. Slow reductions in dose are needed because of the risk of relapse. For popular plaque-like forms of oral LP, topical retinoids can be recommended as first line treatment alone or in association with topical corticosteroids. Three small RCTs compared topic retinoid (retinoic acid 0.05%, isotretinoin gel and tazarotene) with placebo. Improvement or cure rates were significantly higher in the treated group [22–24].

Second line

For erosive LP, if no or insufficient improvement is observed after topical corticosteroids, second line treatment is oral corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/day) until remission, generally 4–6 weeks [21].

Third line

No superiority over topical corticosteroids was demonstrated in the four RCTs comparing oral ciclosporin to topical corticosteroids [8]. No topical formulation is available. Two trials compared tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with clobetasol propionate 0.5%. One found a statistically significant difference favouring tacrolimus [25], while no difference between treatments was observed in the other [26]. An RCT comparing pimecrolimus cream 1% to triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% found no difference between the two treatments [27]. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (ciclosporin, pimecrolimus and tacrolimus) have thus not demonstrated their superiority over topical corticosteroids. Current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labelling states that topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus should not be used to treat premalignant conditions. They have to be used with caution in oral LP due to the inherent risk of malignant transformation.

Several others treatments were assessed in RCTs (curcuminoids, hyaluronic acid, ignatia, purslane, oral lycopene, intralesional injection of the polysaccharide nucleic acid fraction of BCG, thalidomide, Aloe vera gel) [28–34]. A pooled estimate for the mean clinical score of two RCTs comparing topical Aloe vera with placeo was risk ratio 1.34 (95% confidence interval 1.10–1.62) [35, 36] and one RCT comparing Aloe vera gel with triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% found no difference between the groups [37]. These treatments are not recommended for the treatment of oral LP.

Ano-genital lichen planus

Early super-potent corticosteroid treatment (0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment once daily) aims to resolve symptoms and prevent synechiae and scarring of the genital area, although efficacy for the prevention of scars or relapses has not been demonstrated. Hydrocortisone suppositories, foam or cream every other day is used for vaginal localization. Potent corticosteroids can be used daily during the initial phase until symptom resolution [6]. The frequency of application during maintenance treatment and its duration should be adapted according to evolution. Foreskin retraction or removal surgery in uncircumcised men and vaginal dilators in women are used to prevent synechiae formation. Surgery is required after complete resolution of the active lesions if adhesion occurs.

Lichen planopilaris

In order to lessen pain and pruritus, and to avoid irreversible alopecia, first line treatment is potent corticosteroids (e.g. 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment twice daily). In severe cases or in cases of insufficient improvement after corticosteroid ointment, second line treatment is monthly intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (0.5–10 mg/mL) or systemic oral corticosteroids (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) [6, 37, 38].

Frontal fibrosing alopecia

Treatments can be of limited efficacy but several options have been proposed including topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, hydroxychloroquine, topical and oral immunomodulators, tacrolimus and 5α-reductase inhibitors [38, 39].

Nail lichen planus

Evidence for nail LP is based only on retrospective case series and depends on the number of affected nails. The aims of treatment are to reduce pain and avoid irreversible nail scars. Two-thirds of 142 patients treated with intramuscular injection or oral systemic glucocorticoids and/or intralesional injection or topical glucocorticoids during 6 months were cured or had a major improvement [4, 40].

When less than four nails are involved, the recommended treatment is a twice daily application of super-potent corticosteroids (e.g. 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment), or if lesions are more severe, monthly intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (0.5–10 mg/mL) in the periungual sites.

When more than two or three nails are involved, systemic corticosteroids are required. Treatment with oral prednisolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) for 4–66 weeks or intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide injection have been reported. Etanercept has been suggested in a case report [41], although LP-like eruptions can be triggered by tumour necrosis factor antagonists [42].

Severe erosive lichen planus

Systemic corticosteroids are first line treatment [7]. Systemic immunosuppressive agents (e.g. azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate) are used as corticosteroid-sparing agents for patients with erosive or potentially scarring LP requiring prolonged systemic corticosteroids or in disease unresponsive to corticosteroids. Complete remission was obtained following sessions of extracorporeal photochemotherapy in 16 of 19 patients in two prospective series of patients with resistant severe erosive LP [43, 44].

Lichen nitidus

As the disease is often asymptomatic and eventually self-limiting, no treatment is required in most cases. However, fluorinated topical corticosteroid preparations may be recommended if treatment is demanded, for example for lesions on the penis, and can be highly successful [45]. Clearance of generalized lichen nitidus has been described with sun exposure [46], PUVA [47], narrow-band UVB phototherapy [48, 49] and astemizole [50, 51]. Acitretin can lead to a gradual improvement in palmoplantar lichen nitidus [52].

Nékam disease/keratosis lichenoides chronica

The course of the dermatosis is chronic and progressive and very resistant to therapeutic approaches, but has shown a favourable response to photochemotherapy without [53, 54] or with [55] acitretin. Etretinate [56] and photodynamic therapy [57] have been reported to be helpful.

‘Mixed’ lichen planus/discoid lupus erythematosus disease patterns

Both ciclosporin [58] and acitretin [59] can be of benefit in treating LP/DLE overlap syndrome.

Actinic lichen planus

Actinic LP has been treated with acitretin and topical corticosteroids [60] and with ciclosporin [61].

Bullous lichen planus and lichen planus pemphigoides

Some cases require treatment with systemic steroids or azathioprine and fatalities can occur [60]. A combination of corticosteroids and acitretin has been used [61, 62].

LICHEN STRIATUS

Definition and nomenclature

Lichen striatus is a distinctive, usually self-limiting and asymptomatic inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pink or red papules in a linear distribution that develop in the lines of Blaschko. These usually occur as isolated lesions on the limbs in children aged 5–15 years and generally resolve over 6–12 months. Areas of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation may occur and persist for longer. The aetiology is incompletely understood but approximately 40% of cases have a background of atopy. Clustering of cases in families and in winter suggests an infectious agent; potentially, a virus may be involved.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The incidence or prevalence is unknown, but, between January 1989 and January 2000, 115 cases were identified at the Paediatric Dermatology Unit, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy [1].

Age

Over 50% of cases occur in children, usually between the ages of 5 and 15 years, but onset in early infancy and in adults has been reported.

Sex

Females are affected approximately two to three times as frequently as males [1].

Associated diseases

Lichen striatus occurs more often in individuals with atopy; atopy was reported in approximately 43% of cases in a recent series [2].

Pathophysiology

As the condition develops in the lines of Blaschko, which represent embryonic migratory patterns of ectoderm (see Chapter 7), it has been hypothesized that post-zygotic mutation or loss of heterozygosity may lead to cutaneous mosaicism and play a role in its pathophysiology, perhaps predisposing to the effects of an environmental trigger or an infectious agent. The presence of atopy in approximately 40% of cases is therefore intriguing. On the other hand, the resolution of lichen stratus over a period of months in the majority of cases suggests a temporary phenomenon, leading to the proposal of cutaneous antigenic mosaicism and a localized inflammatory T-cell response, again potentially related to viral infection or injury [3].

Pathology

The histological appearances are variable and depend on the stage of disease [3]. Usually, a band-like infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes is observed with associated overlying epidermal change including parakeratosis and hyperkeratosis, resembling lichen planus. The earliest change is intercellular oedema, stretching the tonofilament–desmosome complexes and separating the epidermal cells. Like the spongiosis, acanthosis is variable in degree. Dyskeratotic keratinocytes, like the ‘corps ronds’ of Darier disease, are seen in about 50% of cases. There is often focal liquefactive degeneration of the basal layer. The dermis is oedematous, and the vessels and appendages are surrounded by an infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, which may be quite dense and extend deeply. Scattered lymphocyte cells often penetrate into the epidermis.

Immunohistochemical studies have revealed a predominance of CD8+ T cells compared with CD4+ T cells [3, 4].

Genetics

Familial cases are documented [1, 5, 6], although whether this relates to clustering related to contact with a common infectious agent remains to be determined.

Environmental factors

Possible triggering factors include infectious agents and trauma. For example, in a retrospective case review of 115 cases from Italy, the majority occurred in the cold season, five had prodromal symptoms of viral infection and two had a preceding history of skin trauma [1]. Other reported triggers include varicella infection [7] and measles, mumps and rubella vaccination [3].

Clinical features

History

The onset is usually sudden. Frequently, there are no symptoms, but pruritus may occasionally occur and is more common in adults. The course is variable. The area affected typically reaches its maximum extent within 2–3 weeks, but gradual extension can continue for several months. Spontaneous resolution can be expected within 6–12 months in most cases, but some lesions may persist for over a year [8]. Resolution may be followed by hypopigmentation or more rarely hyperpigmentation [1, 2].

Presentation

The initial presentation is characterized by the sudden appearance of small, discrete, pink, flat-topped, lichenoid papules in a typical linear distribution. In a recent series of 24 patients from Spain, 11 presented with erythematous papules [2]. Occasionally, vesicles are observed, but were present in only two out of 24 patients. The lesions extend over the course of a week or more and rapidly coalesce to form a dull-red to brown, slightly scaly, linear band, usually 2 mm to 2 cm in width, and often irregular. Occasionally, the bands broaden into plaques, especially on the buttocks. The lesion may be only a few centimetres in length or may extend the entire length of the limb, and may be continuous or interrupted (Figure 37.28).

Figure 37.28 Lichen striatus of the inner thigh in a girl aged 16 years. The histological changes were those of chronic eczema.

(Courtesy of Dr R.A. Marsden, St George's Hospital, London, UK.)

The initial lichenoid papules are pink and not violaceous, and show no umbilication or Wickham's striae. The papules may be hypopigmented in dark-skinned people and hypopigmentation was noted at presentation in one-third of 24 cases reported from Spain [2]. Residual persistent hypopigmentation was also noted in approximately 30% of cases in a review of over 190 patients [2]. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is reported less commonly (approximately 7% of 135 reported cases) [2].

The lesions occur most commonly on one arm or leg, or on the neck, but may develop on the trunk [1]. A review of more than 300 cases showed that over 75% occurred on the limbs [2]. The abdomen, buttocks and thighs may be involved in single extensive lesions, but multiple lesions are rare, and bilateral involvement is exceptional. Involvement of the nails may result in longitudinal ridging, splitting, onycholysis or nail loss [1, 9].

Clinical variants

Parallel linear bands or zosteriform patterns have been recorded (Figure 37.29) and extensive bilateral lesions were reported in two out of 24 patients in the series from Barcelona, Spain [2]. The majority of episodes are solitary, but occasionally repeated episodes can occur in different locations.

Figure 37.29 Lichen striatus showing parallel linear bands in a zigzag distribution on the thigh of a 15-year-old girl. Histology showed epidermal hyperkeratosis, focal liquefactive degeneration at the dermo-epidermal junction; upper dermal oedema with chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis. The eruption resolved spontaneously.

Differential diagnosis

Linear inflammatory eruptions that are distributed along Blaschko's lines or show a zosteriform distribution, including linear psoriasis, linear Darier disease, linear lichen planus, linear porokeratosis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus (ILVEN), should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Linear forms of lichen planus and psoriasis can usually be differentiated clinically, even in the absence of typical lesions in other sites, which should always be sought. ILVEN (Chapter 75), in particular, has many clinical and histological features in common with lichen striatus. However, ILVEN is always pruritic and persists despite periods of relative improvement. The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions includes linear vitiligo or nevoid hypomelanosis [2].

Disease course and prognosis

The disease course is variable. The majority of lesions last for at least 6 months and resolve within 1 year, but lesions may last for just a few weeks or persist for several years, both in children and in adults [1, 8]. It may follow a prolonged and/or relapsing course, particularly in adults [1, 10]. Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation may last for years, particularly in darker skin types2. Hypopigmentation may also be the presenting feature in some patients [2]. Lichen striatus presenting in adults tends to be more extensive and symptomatic and may require treatment (see below) [10].

Investigations

Skin biopsy may be helpful.

Management

General principles of management

Usually no treatment is necessary in childhood cases which are largely asymptomatic and typically spontaneously resolve. In patients with troublesome itch (usually adults), topical corticosteroids are the first line of management. However, in resistant cases or when there are concerns over topical corticosteroid-induced skin atrophy, calcineurin inhibitors may be considered. Because of the rarity of the condition, no trials have been performed, but individual case reports and small case series report positive and prompt symptomatic response and rapid resolution of lesions in response to both tacrolimus and pimecrolimus [4, 10, 11]. A single case of a response to photodynamic therapy is reported [12]. Nail involvement may respond to potent steroid cream under occlusion.

References

Definition

- Darier J. Précis de Dermatologie, p. 118. Paris: Masson, 1909.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid tissue reaction. Int J Dermatol 1982;21(4):203–6.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25(4):593–619.

Lichen planus

Introduction and general description

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. Sci World J 2014;2014:742826.

- Depaoli M. [Clinico-statistical data on lichen ruber planus.] Minerva Dermatol 1964;39:166–71.

- Schmidt H. Frequency, duration and localization of lichen planus. A study based on 181 patients. Acta Derm Venereol 1961;41:164–7.

- Bhattacharya M, Kaur I, Kumar B. Lichen planus: a clinical and epidemiological study. J Dermatol 2000;27(9):576–82.

- Daramola OO, Ogunbiyi AO, George AO. Evaluation of clinical types of cutaneous lichen planus in anti-hepatitis C virus seronegative and seropositive Nigerian patients. Int J Dermatol 2003;42(12):933–5.

- Balasubramaniam P, Ogboli M, Moss C. Lichen planus in children: review of 26 cases. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008;33(4):457–9.

- Kumar RR, Hay KD. Demographic analysis of oral lichen planus presentations to Auckland Oral Medicine Clinic from 1999 to 2006. NZ Dent J 2010;106(3):113–14.

Pathophysiology

- Bramanti TE, Dekker NP, Lozada-Nur F, Sauk JJ, Regezi JA. Heat shock (stress) proteins and gamma delta T lymphocytes in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995;80(6):698–704.

- Gotoh A, Hamada Y, Shiobara N, et al. Skew in T cell receptor usage with polyclonal expansion in lesions of oral lichen planus without hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Exp Immunol 2008;154(2):192–201.

- Hasseus B, Jontell M, Brune M, Johansson P, Dahlgren UI. Langerhans cells and T cells in oral graft versus host disease and oral lichen planus. Scan J Immunol 2001;54(5):516–24.

- Wenzel J, Peters B, Zahn S, et al. Gene expression profiling of lichen planus reflects CXCL9+-mediated inflammation and distinguishes this disease from atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128(1):67–78.

- Gassling V, Hampe J, Acil Y, Braesen JH, Wiltfang J, Hasler R. Disease-associated miRNA-mRNA networks in oral lichen planus. PLOS One 2013;8(5):e63015.

- Terlou A, Santegoets LA, van der Meijden WI, et al. An autoimmune phenotype in vulvar lichen sclerosus and lichen planus: a Th1 response and high levels of microRNA-155. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132(3 Pt 1):658–66.

- Shen Z, Gao X, Ma L, Zhou Z, Shen X, Liu W. Expression of Foxp3 and interleukin-17 in lichen planus lesions with emphasis on difference in oral and cutaneous variants. Arch Dermatol Res 2014;306(5):441–6.

- Dutz JP. T-cell-mediated injury to keratinocytes: insights from animal models of the lichenoid tissue reaction. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129(2):309–14.

- Breathnach SM, Katz SI. Immunopathology of cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol 1987;9(4):343–8.

- Liddle BJ, Cowan MA. Lichen planus-like eruption and nail changes in a patient with graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol 1990;122(6):841–3.

- Garcia FVMJ, Pascual-Lopez M, Elices M, Dauden E, Garcia-Diez A, Fraga J. Superficial mucoceles and lichenoid graft versus host disease: report of three cases. Acta Derm Venereol 2002;82(6):453–5.

- Shiohara T. The lichenoid tissue reaction. An immunological perspective. Am J Dermatopathol 1988;10(3):252–6.

- Fayyazi A, Schweyer S, Soruri A, et al. T lymphocytes and altered keratinocytes express interferon-gamma and interleukin 6 in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291(9):485–90.

- Sugerman PB, Satterwhite K, Bigby M. Autocytotoxic T-cell clones in lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2000;142(3):449–56.

- Villarroel Dorrego M, Correnti M, Delgado R, Tapia FJ. Oral lichen planus: immunohistology of mucosal lesions. J Oral Pathol Med 2002;31(7):410–14.

- Kawamura E, Nakamura S, Sasaki M, et al. Accumulation of oligoclonal T cells in the infiltrating lymphocytes in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med 2003;32(5):282–9.

- Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, et al. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2002;13(4):350–65.

- Zhao ZZ, Sugerman PB, Walsh LJ, Savage NW. Expression of RANTES and CCR1 in oral lichen planus and association with mast cell migration. J Oral Pathol Med 2002;31(3):158–62.

- Iijima W, Ohtani H, Nakayama T, et al. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells in oral lichen planus predominantly express CCR5 and CXCR3 and carry respective chemokine ligands RANTES/CCL5 and IP-10/CXCL10 in their cytolytic granules: a potential self-recruiting mechanism. Am J Pathol 2003;163(1):261–8.

- Little MC, Griffiths CE, Watson RE, Pemberton MN, Thornhill MH. Oral mucosal keratinocytes express RANTES and ICAM-1, but not interleukin-8, in oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid reactions induced by amalgam fillings. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28(1):64–9.

- Zhao ZZ, Sugerman PB, Zhou XJ, Walsh LJ, Savage NW. Mast cell degranulation and the role of T cell RANTES in oral lichen planus. Oral Dis 2001;7(4):246–51.

- Shiohara T, Moriya N, Nagashima M. The lichenoid tissue reaction. A new concept of pathogenesis. Int J Dermatol 1988;27(6):365–74.

- Yamamoto T, Osaki T. Characteristic cytokines generated by keratinocytes and mononuclear infiltrates in oral lichen planus. J Invest Dermatol 1995;104(5):784–8.

- Yamamoto T, Nakane T, Osaki T. The mechanism of mononuclear cell infiltration in oral lichen planus: the role of cytokines released from keratinocytes. J Clin Immunol 2000;20(4):294–305.

- Deguchi M, Aiba S, Ohtani H, Nagura H, Tagami H. Comparison of the distribution and numbers of antigen-presenting cells among T-lymphocyte-mediated dermatoses: CD1a+, factor XIIIa+, and CD68+ cells in eczematous dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus and graft-versus-host disease. Arch Dermatol Res 2002;294(7):297–302.

- Musso T, Scutera S, Vermi W, et al. Activin A induces Langerhans cell differentiation in vitro and in human skin explants. PLOS One 2008;3(9):e3271.

- Zhou XJ, Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Seymour GJ. Intra-epithelial CD8+ T cells and basement membrane disruption in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med 2002;31(1):23–7.

- Zhou XJ, Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in oral lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28(2):72–82.

- Ammar M, Mokni M, Boubaker S, El Gaied A, Ben Osman A, Louzir H. Involvement of granzyme B and granulysin in the cytotoxic response in lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35(7):630–4.

- Kim SG, Chae CH, Cho BO, et al. Apoptosis of oral epithelial cells in oral lichen planus caused by upregulation of BMP-4. J Oral Pathol Med 2006;35(1):37–45.

- Chen Y, Zhang W, Geng N, Tian K, Jack Windsor L. MMPs, TIMP-2, and TGF-beta1 in the cancerization of oral lichen planus. Head Neck 2008;30(9):1237–45.

- Segura S, Rozas-Munoz E, Toll A, et al. Evaluation of MYC status in oral lichen planus in patients with progression to oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol 2013;169(1):106–14.

- Lu R, Zhang J, Sun W, Du G, Zhou G. Inflammation-related cytokines in oral lichen planus: an overview. J Oral Pathol Med 2013.