CHAPTER 44

Urticarial Vasculitis

Elena Borzova1 and Clive E. H. Grattan2

1Russian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, Russian Federation

2Norfolk and Norwich University HospitalNorwich; St John's Institute of Dermatology, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Definition and nomenclature

Urticarial vasculitis is a rare disease characterized clinically by urticarial lesions with histological evidence of leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Clinicopathological correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Introduction and general description

Urticarial vasculitis is a rare disease characterized by continued wealing associated with histopathological evidence of leucocytoclastic vasculitis [1]. If associated with systemic involvement, urticarial vasculitis can lead to substantial morbidity [2]. Distinguishing between hypocomplementaemic and normocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis is important since the former may have multisystem involvement, including nephritis, whereas the latter usually runs a benign and, ultimately, self-limiting course. Urticarial vasculitis is a complex dynamic process with incompletely understood pathophysiology [3]. The diagnosis relies on a lesional skin biopsy and can be challenging in clinical practice for both clinicians and histopathologists [4, 5]. A thorough laboratory work-up is essential in patients with urticarial vasculitis in view of potential multisystem involvement and the possibility of identifying associated diseases relevant to its pathogenesis [4]. Successful management of urticarial vasculitis can be difficult and includes antihistamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral corticosteroids, antimalarials and immunosuppressive agents [5, 6] Recently, biological agents have been used in the treatment of urticarial vasculitis [7].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The lifetime prevalence of urticarial vasculitis has not been studied but may be in the region of 0.025% (estimated as 5% of the estimated prevalence of chronic urticaria). It is a rare disease that occurs in about 1–20% of patients presenting with a chronic urticarial illness [2, 5, 8]. The use of different diagnostic criteria has resulted in considerable variation in the reported frequencies of urticarial vasculitis in patients with chronic urticarial disease [5].

Age

Urticarial vasculitis occurs with peak incidence in the fourth decade of life [9, 10]. The incidence of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS) peaks in the fifth decade [11, 12]. Both forms are rare in children [13].

Sex

Women are more often affected than men [9, 10, 14].

Ethnicity

Ethnic predisposition to urticarial vasculitis is unknown; it has been reported in white people [10, 14] and Asian populations [15].

Associated diseases

Several diseases are associated with urticarial vasculitis [4, 6, 16] although it is unknown whether these represent causality or coincidence.

Common associations with urticarial vasculitis are attributed to connective tissue diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus [17] and Sjögren disease [18]. Chronic hepatitis B and C are frequent associations [10, 19] although other infections such as infectious mononucleosis [20] and Lyme borreliosis [21] have been also linked. Serum sickness represents an acute form of urticarial vasculitis [6].

Urticarial vasculitis has been reported in association with haematological disorders (essential cryoglobulinaemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenia) and malignancies (Hodgkin lymphoma, acute non-lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, immunoglobulin A (IgA) myeloma) [6, 10, 22]. An association between urticarial vasculitis and adenocarcinoma of the colon has also been described in a single case report [23].

Although urticarial vasculitis has been reported in Schnitzler syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome and Cogan syndrome [6, 24] it now accepted that the histopathological changes seen in Schnitzler syndrome [25] and other autoinflammatory syndromes should be regarded as a neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis (NUD) rather than vasculitis (see Chapter 45). Muckle–Wells syndrome is a genetic autoinflammatory disorder characterized by recurrent wealing, fever, arthralgia and sensorineural deafness [26]. Cogan syndrome is characterized by a constellation of interstitial keratitis, audiovestibular disturbance and systemic vasculitis [27]. This can be seen in around 10% of cases and may involve the large vessels, appearing as Takayasu-like vasculitis involving the aortic valve but also the coronary arteries and small vessels of the kidneys.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of urticarial vasculitis is incompletely understood mainly due to great interpatient variability and the scarcity of sequential histological studies of disease development and progression. Several factors are thought to be of pathogenic importance in this disease, including circulating immune complexes, complement activation via the classical pathway, mast cell activation, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, endothelial cell activation and damage as well as inflammatory cell infiltration, neutrophil karyorrhexis and fibrin deposition [2, 3, 28, 29].

Urticarial vasculitis affects predominantly postcapillary venules in the superficial dermis. The vascular endothelial damage is thought to be mediated by circulating immune complexes [29]. Deposition of IgG and IgM and C3 within and around the vessel wall and at the dermal–epidermal junction is a common feature [1, 10, 14].

Hypocomplementaemia in urticarial vasculitis is consistent with complement activation via the classical complement pathway caused, presumably, by circulating immune complexes [16, 29]. Patients with HUVS usually have IgG autoantibodies directed against the collagen-like region of C1q and low levels of C1q [2].

A spectrum of autoantibodies has been observed in urticarial vasculitis including antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens [17], antiphospholipid [24] and antiendothelial antibodies [30]. Skin autoreactivity to patient's serum has been reported occasionally in urticarial vasculitis [31] although there has been no systematic study to ascertain how commonly this occurs. The pathogenic importance of these observations is unclear and further research may elucidate their clinical relevance.

Mast cell activation is thought to occur early in the formation of vasculitic lesions [28] This is associated with the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor-α [28]. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist are also increased in the serum of patients with urticarial vasculitis [7].

The mechanisms of activation and damage of endothelial cells in urticarial vasculitis are poorly understood. Microscopically, endothelial cell involvement is characterized by swelling and necrosis [5, 32]. Endothelial cell activation is reflected by upregulation of cell adhesion molecules [3, 28]. In vasculitis, endothelial cell activation is known to result in the loss of anticoagulant and fibrinolytic properties, thereby leading to fibrin deposition and fibrinoid degeneration of the affected vessels [33]. Also, activation of endothelial cells contributes to the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the perivascular infiltrate. Unresolved questions remain as to whether this activation is caused by antiendothelial antibodies, complement activation or transmigration of inflammatory cells.

The dynamic nature of the inflammatory infiltrate has been reported [28, 34]. In serial biopsies from a patient with exercise-induced urticarial vasculitis, eosinophils were the first cells recruited at 3 h, followed by neutrophil predominance at 24 h [28]. Histological studies have shown extracellular deposition of eosinophil peroxidase and neutrophil elastase [28]. Neutrophil-rich infiltration with leucocytoclasis is a common feature. Lymphocytes are thought to be the predominant cells in the perivascular infiltrate in the lesions older than 48 h [2, 34]. The true relevance of lymphocytic infiltration to the vasculitic process needs to be clarified further [35].

Predisposing factors

There are few hard data on predisposing factors in urticarial vasculitis (see Genetics and Environmental factors later).

Pathology

Classical histopathological features of fully developed urticarial vasculitis are: (i) endothelial cell damage and swelling and loss of integrity of the vessel wall; (ii) fibrin deposits in the affected postcapillary venules; (iii) neutrophil-predominant perivascular infiltrate with leucocytoclasis; and (iv) erythrocyte extravasation [5, 36, 37]. However, all of these features may not be present, thereby causing diagnostic uncertainty. Furthermore, the well-recognized continuum of histological changes between urticaria and urticarial vasculitis [36, 38, 39] may contribute to uncertainty over diagnosis.

Immunoglobulin G, IgM and/or C3 within or around the vessels of lesions is seen more often in patients with hypocomplementaemic than normocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis [10]. Immunoglobulin deposits can also be detected at the dermal–epidermal junction [14]. Some authors argue that 70% of patients with immunoglobulin deposition at the dermal–epidermal junction develop glomerulonephritis [40].

There may be eosinophil predominance in normocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis, whereas patients with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis have neutrophil-rich perivascular infiltrates [41] and dermal neutrophilia [10].

Lymphocytic predominance in perivascular infiltration is often seen in skin biopsy specimens from lesions older than 48 h [2, 34]. Lymphocytic vasculitis is not a common feature in urticarial vasculitis [35] and the histological diagnosis in these cases should be based on the histological evidence of vessel damage with fibrinoid degeneration [5].

Genetics

The genetic basis of urticarial vasculitis is largely unknown. It is not known to be familial but the concordance of HUVS was described in identical twins [42]. Recently, homozygous mutations in DNASE1L3 encoding an endonuclease have been identified in two families with autosomal recessive HUVS [43].

Environmental factors

Potential causes include drugs, infections and physical factors. Drugs implicated in the development of urticarial vasculitis include cimetidine, diltiazem, procarbazine, potassium iodine, fluoxetine, procainamide, cimetidine and etanercept [5, 6, 16]. Infections include hepatitis B and C, infectious mononucleosis and Lyme disease. Rarely, the disease is caused by physical factors such as exercise and exposure to sun or cold [16].

Clinical features

History

In some cases, infection or drug intake may precede the onset of urticarial vasculitis. Patients complain of recurrent weals which are typically painful rather than itchy, lasting longer than 24 h and leaving residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 44.1) [2]. Patients often complain about fatigue, malaise or fever associated with weals [6].

Figure 44.1 Urticarial vasculitis lesions resembling weals of chronic spontaneous urticaria. These sometimes fade leaving bruising.

Presentation

In some patients, weals in urticarial vasculitis are indistinguishable from those in chronic urticaria. Recent evidence suggests that urticarial vasculitis may be an underlying process in 20% of patients with clinical presentations of chronic urticaria resistant to treatment with antihistamines [8]. In addition to weals, other cutaneous signs in urticarial vasculitis may include livedo reticularis, Raynaud phenomenon and very occasionally bullous lesions [5, 6, 29]. Angio-oedema frequently occurs [2].

Joint involvement is common; usually arthralgia and joint stiffness and, rarely, arthritis or synovitis [6, 9, 29]. Patients with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis may present with gastrointestinal features including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, intestinal bleeding or diarrhoea [29]. Some patients develop transient or persistent microscopic haematuria and proteinuria [10]. Pulmonary symptoms may include cough, dyspnoea or haemoptysis [44] and occasionally the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis has been detected on lung biopsy in these patients [16]. The pulmonary involvement tends to be more severe in smokers [16]. Other clinical presentations may include adenopathy, splenomegaly or hepatomegaly [6]. Rare neurological (pseudotumour cerebri, optic nerve atrophy) or ocular (episcleritis, uveitis, scleritis, conjunctivitis) manifestations may occur [16]. Of interest, a few case reports suggested a distinct association of cardiac valvulopathy, Jaccoud arthropathy with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis [45].

Clinical variants

Hypocomplementaemic disease tends to be more severe than normocomplementaemic disease [24]. It remains unclear whether there is a transition between these clinical variants over time [2]. Therefore, serial testing of serum complement levels over time is important for distinction between normocomplementaemic and hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis.

Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome is a distinct clinical syndrome identified in about 5% of patients with urticarial vasculitis [2] with the following diagnostic criteria: (i) biopsy-proven vasculitis; (ii) arthralgia or arthritis; (iii) uveitis or episcleritis; (iv) recurrent abdominal pain; (v) glomerulonephritis; and (vi) decreased C1q or presence of anti-C1q autoantibodies [24]. Not all systemic features are required to make a diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

In clinical practice, it may sometimes be difficult to differentiate lesions of urticarial vasculitis from urticaria when some of the characteristic histopathological features of vasculitis are not present in the skin biopsy [36].

The continuum of histological changes between urticaria and urticarial vasculitis has been well recognized and confirmed by a series of patients with intermediate histological features [36]. This suggests that there may not be a clear-cut histological distinction between these two conditions. Therefore, the concept of minimal diagnostic histological criteria for urticarial vasculitis has been introduced [5]. Some authors suggest that leucocytoclasis and/or fibrin deposition with or without erythrocyte extravasation may be sufficient for diagnosis in difficult cases [5]. The difficulties in differential diagnosis between urticaria and urticarial vasculitis experienced by clinicians and histopathologists reflect an existing gap in our knowledge of skin pathology in these two conditions and warrants further research.

The detection of some histopathological features of urticarial vasculitis may be difficult due to the limitations of the existing methodologies. For example, endothelial damage is better assessed by electron microscopy and may be challenging to detect on routine histology. The representation of affected vessels in skin biopsy depends on the focal plane of the section through the vessel [46]. Thus, careful examination of several sections from the same biopsy specimen may help to identify the affected vessels. Further development of diagnostic approaches may enhance the accuracy of the diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis in difficult cases.

Classification of severity

Severity of urticarial vasculitis varies from mild to life-threatening; there is no established consensus on the severity grading. A patient-reported urticarial vasculitis activity score (UVAS) has been recently developed for research applications [7]. Patients with cutaneous involvement only are considered to have milder disease. Patients with severe urticarial vasculitis present with hypocomplementaemia, systemic involvement or treatment-refractory disease. HUVS is at the very severe end of the spectrum [2].

Complications and co-morbidities

Patients with urticarial vasculitis may present with renal involvement (microscopic haematuria or proteinuria) at disease onset or later in the disease course but it rarely progresses to renal failure. Renal biopsy may reveal glomerulonephritis [16]. Patients with urticarial vasculitis, who have deposits of immunoglobulins or complement at the dermal–epidermal junction on direct immunofluorescence, are more likely to develop glomerulonephritis [39].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is considered as a life-threatening late complication of urticarial vasculitis [2].

Connective tissue diseases and haematological malignancies are common co-morbidities in urticarial vasculitis [6] (see disease associations later). In some patients, urticarial vasculitis can be the first presentation of these diseases while in others urticarial vasculitis can present in the context of these diseases. Chronic viral infections (hepatitis B and C) are other important co-morbidities in urticarial vasculitis.

Disease course and prognosis

In most patients, urticarial vasculitis is a self-limiting disease but in some it may last for years [5]. Patients with normocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis limited to the skin tend to have a benign disease with a good prognosis. Conversely, hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis is associated with a more severe course and more frequent systemic involvement [2]. The most severe course is described for HUVS with a high risk for the development of systemic lupus erythematosus [12, 24]. In HUVS, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or laryngeal angio-oedema can be a life-threatening complication [2].

Prognosis in urticarial vasculitis depends on the presence of systemic involvement. Systemic involvement may occur early on although late-onset complications have been described. In some cases, urticarial vasculitis may precede the onset of haematological or connective tissue disorders. More than 50% of patients with HUVS develop systemic lupus erythematosus [12].

Table 44.1 Diagnostic work-up in urticarial vasculitis

| Initial work-up | Extended work-up (dependent on clinical presentation) |

| Lesional skin biopsy (diagnostic) | Direct immunofluorescence studies of skin biopsy |

| Full blood count | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | CH50, anti-C1q antibodies |

| Biochemical profile | Cryoglobulins |

| C3, C4 complement components (serial testing) | 24-h urine protein and creatinine clearance Serum protein electrophoresis |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Chest X-ray, lung function tests |

| Antiextractable nuclear antigens | Assessment of visual acuity and slit lamp examination |

| Hepatitis B and C serology | |

| Circulating immune complexes | |

| Urinalysis | |

Investigations (Table 44.1)

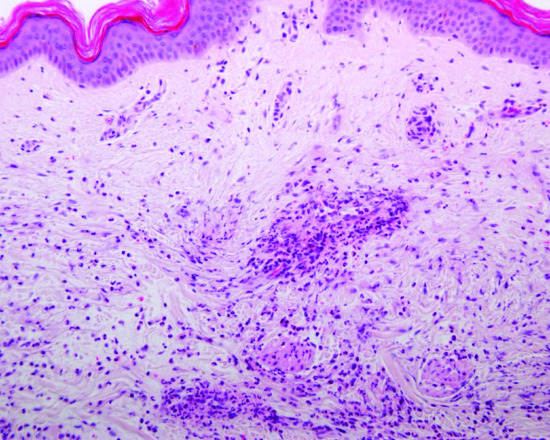

Lesional skin biopsy is the cornerstone of the diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis (Figure 44.2). Several skin biopsies may be required for the confirmation of the diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis [5]. Routine use of direct immunofluorescence on frozen tissue is not recommended unless HUVS is suspected.

Figure 44.2 Urticarial vasculitis – histopathology of lesional skin typically shows a heavy mixed infiltrate within and around blood vessels with predominant neutrophils, leucocytoclasia and evidence of structural vasculitis of postcapillary venules associated with fibrin deposition (H&E, high power).

All patients with urticarial vasculitis should undergo a laboratory work-up consisting of full blood count, blood biochemistry and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Urinalysis and liver function tests are essential in laboratory work-up for systemic involvement. Transient or permanent microscopic haematuria or proteinuria can be observed. In the case of abnormal urinalysis, 24-h urine protein and creatinine clearance should be checked. Complement profile (CH50, C3, C4 and anti-C1q antibodies) is important for differentiating between normocomplementaemic disease and HUVS. Antibody screen in patients with urticarial vasculitis should include antinuclear antibodies, antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor and circulating immune complexes. Testing for hepatitis B and C is important.

The extent of the laboratory work-up should be guided by the patient's history and presentation. For example, suspicion of pulmonary involvement should trigger a work-up including chest X-ray and lung function testing. If eye involvement is suspected, ophthalmic examination should be performed.

Management

Management of urticarial vasculitis is mostly based on case reports, small patient series and a few open-label, non-controlled studies. There is no general agreement on a stepwise approach to the treatment of urticarial vasculitis; however, some guidance can be derived from published experts' opinions and experience [5, 6, 44].

In general, the first line treatments for urticarial vasculitis include H1 antihistamines and NSAIDs [6, 44] (Table 44.2). For non-responders, dapsone 75–100 mg/day, colchicine 1.0–1.5 mg/day and/or hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/day can be used as second line treatments [6, 44]. In unresponsive patients, corticosteroids (prednisolone at doses of 40 mg/day or more) can then be considered for short-term management [5, 6, 44]. However, their prolonged use should be avoided in view of their toxicity. For severe refractory cases, immunosuppressive agents (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, etc.), ciclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil may be beneficial [6, 16, 44, 47].

Table 44.2 Therapeutic algorithm in urticarial vasculitis

| First line treatments | Second line treatments | Third line treatments |

| Non-sedating H1 antihistamines | Dapsone | Azathioprine |

| Colchicine | Ciclosporin | |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Hydroxychloroquine | Mycophenolate mofetil |

| Short trials of corticosteroids | Methotrexate | |

| Intravenous immunoglobulins | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | ||

| ?Interleukin antagonists | ||

| ??Omalizumab |

From Black 1995 [5], Soter 2000 [6] and Berg et al. 1988 [44].

Other approaches such as intravenous immunoglobulins, methotrexate, intramuscular gold and plasmapheresis have also been used [48–51].

Recently, several biological therapies have shown promise for urticarial vasculitis in anecdotal reports or small series. Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) was beneficial in one case [52] and an open-label study demonstrated the efficacy of canakinumab (humanized anti-IL-1β) [7]. A patient with urticarial vasculitis associated with cutaneous lupus erythematosus was treated with anti-IL-6 (tocilizumab) with favourable outcome [53]. A case of normocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis showing a partial response to omalizumab (anti-IgE) has recently been reported [54]. Integration of biological agents into the management protocol for urticarial vasculitis in the future may help overcome the issue of toxicity associated with the use of conventional treatments for urticarial vasculitis, especially long-term oral corticosteroids.

The choice of treatment should take co-morbidities and disease associations into account. For example, patients with urticarial vasculitis with systemic lupus erythematosus may respond to dapsone [16]. Treatment of hepatitis C led to the suppression of urticarial vasculitis [19]. Stratification of patients in terms of systemic involvement and prognosis may facilitate more targeted and individualized treatment approaches in the future.

At present, there is a strong need for double-blind placebo-controlled studies to evaluate the efficacy of conventional and novel therapeutic approaches to urticarial vasculitis. This may be achievable by collaborative multicentre and multidisciplinary efforts given the rarity and complexity of this disease. From a clinical perspective, a consensus on the management of urticarial vasculitis is much needed and would harmonize the treatment approaches to this rare condition.

Resources

Patient resources

- http://www.vasculitisfoundation.org/education/forms/urticarial-vasculitis/ (last accessed November 2015).

References

- McDuffie FC, Sams WM Jr, Maldonado JE, Andreini PH, Conn DL, Samayoa EA. Hypocomplementemia with cutaneous vasculitis and arthritis. Possible immune complex syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1973 May;48(5):340–8.

- Wisnieski JJ. Urticarial vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2000;12:24–31.

- Mehregan DR, Gibson LE. Pathophysiology of urticarial vasculitis. Arch Dermatol 1998 Jan;134:88–9.

- O'Donnell B, Black AK. Urticarial vasculitis. Int Angiol 1995;14(2):166–74.

- Black AK. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Dermatol 1999;17:565–9.

- Soter NA. Urticarial venulitis. Derm Ther 2000;13:400–8.

- Krause K, Mahamed A, Weller K, Metz M, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in urticarial vasculitis: an open-label study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:751–4.

- Tosoni C, Lodi-Rizzini F, Cinquini M, et al. A reassessment of diagnostic criteria and treatment of idiopathic urticarial vasculitis: a retrospective study of 47 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34(2):166–70.

- Aboobaker J, Greaves MW. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1986;11(5):436–44.

- Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE. Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26(3 Pt 2):441–8.

- Schwartz HR, McDuffie FC, Black LF, Schroeter AL, Conn DL. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: association with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1982;57(4):231–8.

- Buck A, Christensen J, McCarty M. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2012;5(1):36–46.

- Martini A, Ravelli A, Albani S, De Benedetti F, Massa M, Wisnieski JJ. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome with severe systemic manifestations. J Pediatr 1994;124(5 Pt 1):742–4.

- Sanchez NP, Winkelmann RK, Schroeter AL, Dicken CH. The clinical and histopathologic spectrums of urticarial vasculitis: study of forty cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;7(5):599–605.

- Lee JS, Loh TH, Seow SC, Tan SH. Prolonged urticaria with purpura: the spectrum of clinical and histopathologic features in a prospective series of 22 patients exhibiting the clinical features of urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56(6):994–1005.

- Venzor J, Lee WL, Huston DP. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2002;23:201–16.

- Asherson RA, D'Cruz D, Stephens CJ, McKee PH, Hughes GR. Urticarial vasculitis in a connective tissue disease clinic: patterns, presentations and treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1991;20(5):285–96.

- Alexander EL, Provost TT. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren's syndrome: a reflection of vasculitis and association with anti-Ro(SSA) antibodies. J Invest Dermatol 1983;80(5):386–91.

- Kelkar PS, Butterfield JH, Kalaaji AN. Urticarial vasculitis with asymptomatic chronic hepatitis C infection: response to doxepin, interferon-alfa and ribavirin. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;35(3):281–2.

- Wands JR, Perrotto JL, Isselbacher KJ. Circulating immune complexes and complement sequence activation in infectious mononucleosis. Am J Med 1976;60:269–72.

- Olson JC, Esterly NB. Urticarial vasculitis and Lyme disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:1114–16.

- Highet AS. Urticarial vasculitis and IgA myeloma. Br J Dermatol 1980;102(3):355–7.

- Lewis JE. Urticarial vasculitis occurring in association with visceral malignancy. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70(4):345–7.

- Grotz W, Baba HA, Becker JU, Baumgärtel MW. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: an interdisciplinary challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106:756–63.

- Lipsker D. The Schnitzler syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5:38.

- Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle–Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50(2):607–12.

- Van Doornum S, McColl G, Walter M, Jennens I, Bhathal P, Wicks IP. Prolonged prodrome, systemic vasculitis and deafness in Cogan's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60(1):69–71.

- Kano Y, Orihara M, Shiohara T. Cellular and molecular dynamics in exercise-induced urticarial vasculitis lesions. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:62–7.

- Gammon WR. Urticarial vasculitis. Dermatol Clin 1985;3:97–105.

- D'Cruz DP, Wisnieski JJ, Asherson RA, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus and urticarial vasculitis. J Rheumatol 1995;22(9):1669–73.

- Athanasiadis GI, Pfab F, Kollmar A, Ring J, Ollert M. Urticarial vasculitis with a positive autologous serum skin test: diagnosis and successful therapy. Allergy 2006;61(12):1484–5.

- Jones RR, Eady RA. Endothelial cell pathology as a marker for urticarial vasculitis: a light microscopic study. Br J Dermatol 1984;110(2):139–49.

- Hunt BJ, Jurd KM. The endothelium in health and disease. In: Hunt BJ, Poston L, Schachter M, Halliday A, eds. An Introduction to Vascular Biology: from basic science to clinical practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002:186–215.

- Zax RH, Hodge SJ, Callen JP. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Serial histopathologic evaluation demonstrates the dynamic nature of the infiltrate. Arch Dermatol 1990;126(1):69–72.

- Guitart J. “Lymphocytic vasculitis” is not urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59(2):353.

- Monroe EW. Urticarial vasculitis: an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;5(1):88–95.

- Carlson JA. The histological assessment of cutaneous vasculitis. Histopathology 2010;56:3–23.

- Jones RR, Bhogal B, Dash A, Schifferli J. Urticaria and vasculitis: a continuum of histological and immunopathological changes. Br J Dermatol 1983;108(6):695–703.

- Phanuphak P, Kohler PF, Stanford RE, Schocket AL, Carr RI, Claman HN. Vasculitis in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1980 Jun;65(6):436–44.

- Chen K-R, Carlson J. Clinical approach to cutaneous vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9(2):330–7.

- Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B, Gibson LE, Rogers RS 3rd. Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38(6 Pt 1):899–905.

- Wisnieski JJ, Emancipator SN, Korman NJ, Lass JH, Zaim TM, McFadden ER. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome in identical twins. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37(7):1105–11.

- Ozçcakar ZB, Foster J 2nd, Diaz-Horta O, et al. DNASE1L3 mutations in hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(8):2183–9.

- Berg RE, Kantor GR, Bergfeld WF. Urticarial vasculitis. Int J Dermatol 1988 Sep;27(7):468–72.

- Palazzo E, Bourgeois P, Meyer O, De Bandt M, Kazatchkine M, Kahn MF. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome, Jaccoud's syndrome, valvulopathy: a new syndromic combination. J Rheumatol 1993;20(7):1236–40.

- Chen K-R. Histopathology of Cutaneous Vasculitis, Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vasculitis. Dr Luis M. Amezcua-Guerra, ed., InTech, 2011, http://www.intechopen.com/books/advances-in-the-diagnosis-and-treatment-of-vasculitis/histopathology-ofcutaneous-vasculitis (last checked by the author, April 2015).

- Worm M, Sterry W, Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis. Br J Dermatol 2000;143(6):1324.

- Handfield-Jones SE, Greaves MW. Urticarial vasculitis – response to gold therapy. J R Soc Med 1991;84(3):169.

- Stack PS. Methotrexate for urticarial vasculitis. Ann Allergy 1994;72(1):36–8.

- Staubach-Renz P, von Stebut E, Bräuninger W, Maurer M, Steinbrink K. [Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Successful therapy with intravenous immunoglobulins.] Hautarzt 2007;58(8):693–7.

- Alexander JL, Kalaaji AN, Shehan JM, Yokel BK, Pittelkow MR. Plasmapheresis for refractory urticarial vasculitis in a patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Drug Dermatol 2006;5(6):534–7.

- Botsios C, Sfriso P, Punzi L, Todesco S. Non-complementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra. Scand J Rheumatol 2007;36(3):236–7.

- Makol A, Gibson LE, Michet CJ. Successful use of interleukin 6 antagonist tocilizumab in a patient with refractory cutaneous lupus and urticarial vasculitis. J Clin Rheumatol 2012;18(2):92–5.

- Kai AC, Flohr C, Grattan CE. Improvement in quality of life impairment followed by relapse with 6-monthly periodic administration of omalizumab for severe treatment-refractory chronic urticaria and urticarial vasculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014;39(5):651–2.