CHAPTER 59

Cutaneous Mucinoses

Franco Rongioletti

Section of Dermatology, Department of Health Sciences (DISSAL), University of Genoa, Genova, Italy

Introduction and general description

The cutaneous mucinoses are a heterogeneous group of disorders whose main characteristic is abnormal mucin deposition in the skin [1]. Mucin or protein–hyaluronic acid complex is a normal component of the dermal extracellular matrix produced in small amounts by fibroblasts. It is a jelly-like amorphous mixture of acid glycosaminoglycans (formerly called acid mucopolysaccharides) that are repeating polysaccharides forming a complex carbohydrate. The acid glycosaminoglycans may be fixed on both sides of a protein core (proteoglycan monomer) as in the case of dermatan sulphate or chondroitin-6-sulphate and chondroitin-4-sulphate, or they may be free as in the case of hyaluronic acid, which is the most important component of dermal mucin.

Mucin is capable of absorbing 1000 times its own weight in water, thus playing a major role in maintaining the salt and water balance of the dermis. However, in disease conditions, mucin is increased and since it holds water (hygroscopic), the dermal connective tissue is oedematous. Mucin may be seen on haematoxylin and eosin stains as a light blue stained material between collagen bundles;however, to highlight these changes special stains are usually needed such as Alcian blue at pH 2.5 (negative at 0.4), colloidal iron and toluidine blue at pH 4.0. Furthermore, mucin is hyaluronidase sensitive and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) negative [2].

Mostly for experimental research, monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies have been used to detect heparan sulphate proteoglycans, the three isoforms of hyaluronan synthase, and the CD44 surface receptor for hyaluronate [3–5]. The pathogenesis of increased mucin deposition in pathological states is unclear. It has been postulated that serum factors such as cytokines and/or immunoglobulins may induce upregulation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis. Cytokines that may play a role in the process include tumour necrosis factor α and β, interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and transforming growth factor β [1]. A decrease in the catabolic process of mucin degradation could also be involved. Many of the cutaneous mucinoses show increased levels of polyclonal or monoclonal immunoglobulin (i.e. scleromyxoedema, pretibial myxoedema, papulonodular mucinosis of lupus erythematosus).

In Chinese Shar-Pei dogs, known for their distinctive features of deep wrinkles, mucin deposition in the skin is a typical condition considered to be a consequence of a genetic defect in the metabolism of hyaluronic acid [6].

The cutaneous mucinoses are divided into two groups: primary (idiopathic) cutaneous mucinoses in which the mucin deposit is the main histological feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions; and secondary mucinoses in which histological mucin deposition is only an additional finding and secondary phenomenon (Box 59.1). Primary mucinoses can be divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses. The former includes lichen myxoedematosus (LM) (generalized and localized), reticular erythematous mucinosis (REM), scleredema, mucinoses in thyroid disease, papular and nodular mucinosis in connective tissue diseases, self-healing cutaneous mucinosis, cutaneous focal mucinosis and myxoid cyst, while the latter include Pinkus follicular mucinosis and urticaria-like follicular mucinosis. Systemic manifestations associated with mucinoses include monoclonal gammopathies in scleromyxoedema and scleredema, diabetes or infections in scleredema, hyperthyroidism in pretibial myxoedema, hypothyroidism in generalized myxoedema and lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis or scleroderma in papular and nodular mucinosis in connective tissue diseases.

PRIMARY MUCINOSES

DERMAL MUCINOSES

Lichen myxoedematosus (papular mucinosis)

Definition

Lichen myxoedematosus is a comprehensive term to define a chronic, idiopathic cutaneous mucinosis characterized by lichenoid papules, nodules and/or plaques due to abnormal dermal mucin deposition and a variable degree of fibrosis and fibroblast proliferation in the absence of thyroid disease. Two clinicopathological subsets are included: (i) a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form (also called scleromyxoedema of Arndt–Gottron) with a monoclonal gammopathy and systemic, sometimes lethal, manifestations; and (ii) a localized papular form which does not have systemic implications. Occasionally, patients with LM have overlapping or atypical features and fall between scleromyxoedema and localized LM (Table 59.1) [1].

Table 59.1 Classification of lichen myxoedematosus with diagnostic criteria.

| Scleromyxoedema | Localized variants of lichen myxoedematosus | Atypical forms of lichen myxoedematosus |

| Generalized papular eruption and sclerodermoid features | Papular eruption (or nodules and/or plaques due to confluence of papules) |

|

| Microscopic triad (mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis) | Mucin deposition with variable fibroblast proliferation and absent fibrosis | |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | Absence of monoclonal gammopathy | |

| Absence of thyroid disorder | Absence of thyroid disorder | |

Subtypes:

|

Scleromyxoedema

Definition and nomenclature

Scleromyxoedema is the sclerotic variant of LM characterized by a generalized papular eruption on a sclerodermoid background, mucin deposition, increased fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis and monoclonal gammopathy [2]. It has systemic implications.

Epidemiology

Scleromyxoedema is a rare disease that usually affects adults between the ages of 30 and 80 years. The mean age of patients is 59 years. The illness has no ethnic or sex predominance and has rarely been reported in infants and young children [2].

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of scleromyxoedema is unknown. Some cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α and β, interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and transforming growth factor β and/or polyclonal and monoclonal immunoglobulins and other unidentified factors in the serum of affected patients may induce upregulation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis from fibroblasts. Although monoclonal paraprotein has been considered pathogenic, the stimulation of fibroblasts occurs even after the removal of the paraprotein. In addition, paraprotein levels usually do not correlate with the severity of disease, disease progression or the response to treatment [3–6]. Finally, case reports documenting the development of scleromyxoedema following a cutaneous granulomatous reaction after intradermal hyaluronic gel injections [7] or after breast silicone implantation [2] may suggest a type of autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants.

Pathology

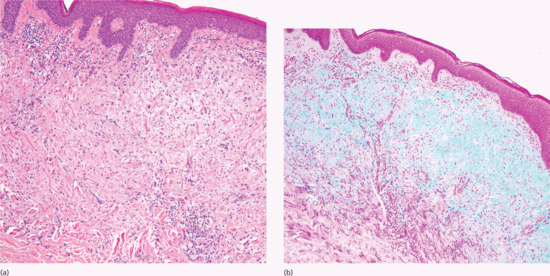

Scleromyxoedema is characterized by a triad of microscopic features: (Figure 59.1a): (i) a diffuse deposit of mucin composed mostly of hyaluronic acid in the upper and mid-reticular dermis confirmed with an Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 (Figure 59.1b) or an iron colloidal stain and hyaluronidase digestion; (ii) an increase in collagen deposition; and (iii) a proliferation of irregularly arranged fibroblasts [8]. The epidermis may be normal or thinned, the hair follicles may be atrophic and a slight perivascular superficial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is often present. The elastic fibres are fragmented and decreased in number. Very recently, an interstitial granuloma annulare-like pattern has been described [9]. In addition to skin involvement, mucin may fill the endocardium, the walls of myocardial blood vessels as well as the interstitium of the kidney, lungs, pancreas, adrenal glands and nerves. Lymph node involvement may occur [10].

Figure 59.1 (a) Scleromyxoedema. The typical triad of microscopic features with diffuse dermal mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation and fibrotic collagen. (b) Increased dermal mucin stained with Alcian blue at pH 2.5.

Clinical features

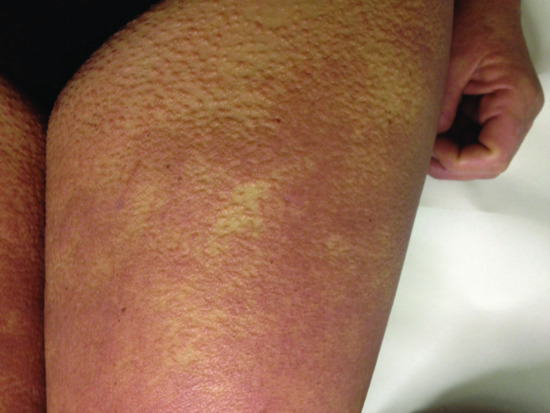

The typical skin features are those of a widespread eruption of 2–3 mm, firm, waxy, closely spaced, dome shaped or flat-topped papules involving the dorsal aspect of the upper limbs, head and neck region, upper trunk and thighs (Figures 59.2, 59.3 and 59.4) [1, 2]. Papules often are arranged in a strikingly linear pattern; the surrounding skin is shiny and thick (i.e. sclerodermoid in appearance). Rarely, non-tender nodules may develop. The glabella typically is involved with deep longitudinal folding that gives the appearance of a leonine face (Figure 59.5). Deep furrowing is also evident on the trunk, shoulders and limbs (Shar-Pei sign) (Figure 59.6). Erythema, oedema and a brownish discoloration may be seen in the involved areas; itching is not uncommon. Eyebrow, axillary and pubic hair may be sparse. Mucosal lesions are absent. As the condition progresses, erythematous and infiltrated plaques develop with skin stiffening, sclerodactyly and reduced mobility of the mouth and the joints of the hands, arms and legs. Over the proximal interphalangeal joints, a central depression surrounded by an elevated rim (due to the skin thickening) is referred to as the ‘doughnut sign’ (Figure 59.7). Telangiectasia and calcinosis are lacking but Raynaud phenomenon may rarely occur.

Figure 59.2 Scleromyxoedema. Widespread eruption of closely spaced papules on the back of the hand.

Figure 59.3 Scleromyxoedema. Papules on the thigh.

Figure 59.4 Scleromyxoedema. Papules behind the ear.

Figure 59.5 Scleromyxoedema. Deep longitudinal erythematous folding on the forehead (leonine face).

(Courtesy of D. Metze, MD, Munster, Germany.)

Figure 59.6 Scleromyxoedema. Deep furrowing on the shoulders and back (Shar-Pei sign).

Figure 59.7 Scleromyxoedema. ‘Doughnut sign’ on the proximal interphalangeal joints.

Differential diagnosis

These are listed in Table 59.2.

Table 59.2 Differential diagnoses [11].

| Disease | Differences from scleromyxoedema |

| Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) |

|

| Scleredema |

|

| Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis |

|

Complications and co-morbidities

Systemic implications are listed in Table 59.3.

Table 59.3 Systemic implications of scleromyxoedema [2, 13].

| Systemic implications | Type | % |

| Haematological | Monoclonal gammopathy (>immunoglobulin G lambda) Myeloma, Hodgkin and non–Hodgkin lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinaemia, myelomonocytic leukaemia [2, 12, 13] |

100 (diagnostic criterion) Rare |

| Neurological | Carpal tunnel syndrome, peripheral sensory and motor neuropathy, central nervous system symptoms (memory loss, vertigo, gait problems, stroke, seizures, psychosis, dermatoneuro syndrome) [14, 15] | 30 |

| Rheumatological | Arthralgias/arthritis, inflammatory myopathy and fibromyalgia [2,13, 16, 17] | 25 |

| Cardiovascular | Congestive heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, heart block, and pericardial effusion | 5–22 |

| Pulmonary | Obstructive or restrictive lung involvement [18] | 17–35 |

| Gastrointestinal | Dysphagia [13] | 3–60 |

| Renal | Acute renal failure [19, 20] | Rare |

Disease course and prognosis

The prognosis of scleromyxoedema is variable. Scleromyxoedema follows a chronic, progressive and sometimes unpredictable course [2]. Involvement of the central nervous system, heart, kidney or progression to overt myeloma worsens the prognosis. The main causes of death include dermatoneuro syndrome (scleromyxoedema with concomitant fever, convulsions and coma), cardiovascular complications and haematological malignancies [2]. Septic complications are mostly linked to melphalan therapy that is now less commonly used [13]. In a recent case series, five (23.8%) of 21 patients had died, whereas 12 were alive with disease and four alive without disease after a mean follow-up period of 33.5 months [2].

Investigations

In addition to skin biopsy, serum and electrophoresis with immunofixation is mandatory. Thyroid function test results are normal. Findings of other laboratory test are usually normal, except in cases of specific extracutaneous symptoms where the internal organs affected should be evaluated. There is little value in imaging studies, although high-resolution cutaneous ultrasonography may become a useful diagnostic and disease activity monitoring tool for skin thickening.

Management

There is no evidence to support any specific definitive treatment for scleromyxoedema because of the rarity of the disorder with a limited number of case reports along with the lack of randomized controlled trials and the incomplete aetiopathogenetic understanding of the disease. In addition, significant toxicity, including death, often associated with some therapies such as melphalan, make therapeutic choices more difficult (see Table 59.2). Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (alone or in combination with other drugs) has gained widespread acceptance as the first line therapy for both skin involvement and extracutaneous manifestations, and especially for acute deterioration of the clinical condition with neurological symptoms [2, 21, 22]. Although remissions persisting for a few months to 3 years after cessation of intravenous immunoglobulin infusions have been reported, the response is not permanent and maintenance infusions spaced out to every 6–8 weeks are required [23]. Thalidomide (or lenalidomide) and/or systemic steroids are considered the second line of treatment, more often in combination with intravenous immunoglobulins than as monotherapy [24–28]. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation can be considered as a third line of treatment [29]. The association of bortezomib and dexamethasone targeting plasma cell dyscrasia has been suggested for recurrences after autologous stem cell transplantation and also for dermatoneuro syndrome [30, 31].

Table 59.4 First, second, third line and optional treatments of scleromyxoedema.

| First line | Second line | Third line | Additional therapies |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | Thalidomidea (lenalidomide) | Autologous stem cell transplantation | Medical Oral retinoids Ciclosporin A Interferon α Hydroxychloroquine Chemotherapeutic agents

Physical Plasmapheresis PUVA, UVA1 Electron beam Extracorporeal photochemotherapy |

| Systemic corticosteroidsb | Bortezomib plus dexamethasone |

aCombination therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin better than monotherapy.

Localized lichen myxoedematosus

Introduction and general description

In localized LM, patients have small firm waxy papules (or nodules and plaques produced by the confluence of papules) confined to only a few sites. There are no sclerotic features, no paraproteinaemia, no systemic involvement and no association with thyroid disease. Localized LM is classified into four subtypes: (i) acral persistent papular mucinosis; (ii) discrete papular lichen myxoedmatosus; (iii) cutaneous (papular) mucinosis of infancy; and (iv) nodular lichen myxoedmatosus [1].

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence rates of the variants of localized LM are unknown as they are rare diseases. Both sexes are equally affected in discrete papular LM. A female predominance (female : male ratio of 3 : 1) has been noted in acral persistent papular mucinosis.

Pathology

In localized LM, the histological changes are less characteristic than in scleromyxoedema. Mucin accumulates in the upper and mid reticular dermis, fibroblast proliferation is variable and fibrosis is not marked and may even be absent. In acral persistent papular mucinosis, mucin accumulates focally in the upper reticular dermis (sparing a subepidermal zone) and fibroblasts are not increased in number (Figure 59.8a, b). In cutaneous mucinosis of infancy, the mucin may be so superficial as to look as if it were ‘enclosed’ by epidermis [1, 8] but mucin deposition may also occur in the reticular dermis.

Figure 59.8 (a) Microscopic features of acral persistent papular mucinosis. Focal mucin accumulation in the upper dermis sparing a grenz zone without fibroblast proliferation. (b) Mucin stained with colloidal iron.

Clinical features

In acral persistent papular mucinosis, multiple ivory to skin-coloured papules develop exclusively on the dorsal aspect of the hands and extensor surface of the distal forearms (Figure 59.9) [32, 33]. Discrete papular LM presents with reddish, violaceous or skin-coloured papules, 2–5 mm in size, numbering from just a few to hundreds and affecting the trunk and limbs in a symmetrical pattern (Figure 59.10) [34]. In cutaneous (papular) mucinosis of infancy, firm opalescent papules appear on the upper arms, neck and trunk [35]. Nodular LM is characterized by multiple nodules on the limbs and trunk, with a mild or absent papular component [36]. Localized lichen myxoedematosus may be observed in association with HIV infection, exposure to toxic oil or l-tryptophan, or hepatitis C virus infection. Localized cutaneous mucinosis resembling LM or plaque-like mucinosis after joint replacement and familial forms of papular mucinosis have also been reported [37–39]. Whether they are distinct entities or atypical and/or familial forms of localized LM is, however, still unclear.

Figure 59.9 Acral persistent papular mucinosis. Multiple skin-coloured papules on the dorsal aspect of the hand.

Figure 59.10 Discrete papular lichen myxoedematosus. Mucinous skin-coloured papules on the trunk.

Differential diagnosis

Histological examination of the skin helps to distinguish localized LM from several papular eruptions that have a similar appearance, such as granuloma annulare, lichen amyloidosus, lichen planus and other lichenoid eruptions, and eruptive collagenoma.

Disease course and prognosis

Localized lichen myxoedematosus in all its variants runs a chronic but benign course in the absence of systemic involvement. Progression to scleromyxoedema has never been proven.

Management

Localized LM is a benign condition that often does not require any therapy (a ‘wait and see’ approach). Many treatments have been tried including dermabrasion, CO2 laser, electrocoagulation, topical and intralesional corticosteroids or hyaluronidase injections, oral retinoids and psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA) with variable results. Topical calcineurin inhibitors [40] may be of some benefit. However, spontaneous resolution may occur, even in the setting of HIV-associated cases [41].

Reticular erythematous mucinosis

Definition and nomenclature

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is a rare, chronic primary cutaneous mucinosis characterized by a persistent reticular macular erythema or erythematous papules and plaques in the midline of the back or chest.

Epidemiology

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is a rare disease that has been described worldwide in patients with different ethnic backgrounds. It affects predominantly middle-aged women, although men and children are not spared [1].

Associated diseases

In general, REM is not related to systemic diseases. However, certain disorders, especially malignancies (e.g. haematological, breast, lung, colon) and thyroid dysfunction have been sometimes associated [1, 2]. Autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and also HIV infection have been anecdotally reported in patients with REM [2].

Pathophysiology

The aetiopathogenesis is unclear. Viral diseases and immunological disturbances have been implicated. The fibroblasts of patients with REM exhibit an abnormal response to stimulation by exogenous interleukin [3].

Predisposing factors

Although REM has been considered a photoaggravated disorder, the role of sunlight is actually controversial [1]. Oral contraceptives, pregnancy, menses, heat, X-ray therapy and perspiration have been also implicated to promote or exacerbate REM [2]. Familial cases suggesting a genetic predisposition have been reported [4].

Pathology

Interstitial deposits of mucin are seen in the upper dermis, along with a perivascular and, at times, perifollicular T-cell infiltrate with variable deep perivascular extension. There is slight vascular dilatation. The epidermis is typically normal. Usually, direct immunofluorescence is negative, but, rarely, granular deposits of immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin A and C3 have been seen at the dermal–epidermal junction [5].

Clinical features

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is characterized by erythematous macules and indurated papules or plaque-like lesions with a reticular configuration and lack of scale or other surface changes in the midline of the chest (Figure 59.11) or back. Atypical areas such as the arms, abdomen, face and legs are occasionally involved. The lesions are occasionally pruritic.

Figure 59.11 Reticular erythematous mucinosis in the midline of the chest and abdomen.

Differential diagnosis

There may be significant overlap between REM and lupus erythematosus tumidus. Both conditions show clinical and histological similarities, lack immune serological abnormalities, respond well to antimalarials and resolve without residual lesions. However, patients with lupus tumidus who do not exhibit reticulate-patterned lesions on the midline, are strongly photosensitive, have a higher rate of immune reactants on direct immunofluorescence, have a higher tendency to recur and occasionally present with other clinical manifestations of lupus [6]. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and pityriasis versicolor involve the central chest, but they have associated scale and different colour, as has confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot–Carteaud.

Disease course and prognosis

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is a chronic disease that, if untreated, has a prolonged duration. The lesions may clear spontaneously, even after 15 years.

Investigations

In general, REM is not associated with abnormal laboratory tests.

Management

Antimalarials (e.g. hydroxychloroquine) are the first line of treatment and they generally result in improvement or healing of the lesions within 1–2 months [7]. Relapses are not uncommon. Results from other therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, oral antihistamines, tetracycline, ciclosporin and pulsed dye laser are quite variable [2, 8, 9]. Despite the potential for an exacerbation, successful results with UVB and UVA1 irradiation have been reported [10, 11].

Scleredema

Definition and nomenclature

Scleredema is a symmetrical diffuse progressive non-pitting swelling and induration of the upper part of the body caused by a thickened dermis and deposition of mucin. Types of scleredema adultorum are listed in Table 59.5.

Table 59.5 Types of scleredema adultorum.

| % Of total | Characteristics | |

| Diabetic | 25–50 | Slowly progressive, non-resolving course Occurs in patients with poorly controlled, insulin-dependent diabetes |

| Non-diabetic | 25 | Idiopathic |

| 25–50 | With preceding febrile illness (poststreptococcal) and complete resolution in months to 2 years | |

| 10–20 | Associated with monoclonal gammopathy including multiple myeloma and slowly progressive, non-resolving course | |

| Anecdotal | Associated with miscellaneous conditions (e.g. HIV, internal malignancies, autoimmune disorders, etc.) |

Introduction and general description

Scleredema is a rare condition characterized by a non-pitting induration of the upper part of the body, associated with diabetes or with a history of infection or blood dyscrasia [1].

Epidemiology

Scleredema is rare and occurs in patients of all ages and ethnic backgrounds. The age distribution varies with the different subtypes. Among patients with diabetes, scleredema has been diagnosed in 2.5–14%. The form that is associated with diabetes is more prevalent in men (10 : 1), while other forms are seen more commonly in women (2 : 1) [2, 3].

Associated diseases

Scleredema can be divided into a diabetic and non-diabetic type (see Box 59.1). The former is considered the most common type accounting for 25–50% of cases. It occurs mainly in obese middle-aged men with poorly controlled insulin-dependent diabetes [3, 4]. The non-diabetic form includes an idiopathic type; a post-infective type with acute onset, usually following a streptococcal upper respiratory infection but also influenza, measles, mumps, chickenpox, cytomegalovirus, diphtheria, encephalitis and dental abscesses; a monoclonal gammopathy-associated type; and a type associated with anecdotal miscellaneous conditions such as autoimmune disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, anaphylactoid purpura), internal malignancies (malignant insulinoma, gallbladder carcinoma, carcinoid tumour, pituitary–adrenocortical neoplasms), exposure to organic solvents and HIV infection [2, 5, 6].

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis is unknown. An increase of type 1 collagen synthesis by dysfunctional fibroblasts has been demonstrated in the affected skin. In diabetic scleredema, the accumulation of collagen may be due to irreversible non-enzymatic glycosylation of collagen and resistance to degradation by collagenase. Alternatively, excess stimulation by insulin, microvascular damage and hypoxia may induce the abnormal synthesis of collagen and mucin. Streptococcal hypersensitivity, injury to lymphatics and paraproteinaemia may also play a role.

Pathology

The epidermis is not involved. The dermis is 3–4 times thicker than normal. The collagen fibres appear swollen and are separated by wide spaces. Acid mucopolysaccharides are found in the fenestrated spaces with special stains. However, negative staining does not exclude the diagnosis. The subcutaneous tissue is also involved with fat being replaced by coarse collagen fibres. A slight perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate may be seen but it is uncommon [7]. Fibroblast proliferation is absent. Mucin also accumulates in skeletal muscle and the heart.

Clinical features

Scleredema is characterized by firm non-pitting oedema and induration that typically begin on the posterior neck and spread to the upper back (Figure 59.12), shoulders and scalp. Erythema and a peau d'orange appearance of the skin are commonly observed. The hands and feet are characteristically spared. Unusual cases with limited site involvement have been reported [8]. Depending on the involved sites, patients often complain of a movement restriction comprising limited body mobility and facial expressions, or difficulties in mastication and articulation.

Figure 59.12 Scleredema in a diabetic patient with firm non-pitting oedema and induration on the upper back, neck and shoulders on erythematous background.

Differential diagnosis

In contrast to systemic sclerosis, scleredema is not associated with sclerodactyly, Raynaud phenomenon, nail fold capillary changes or serum autoantibodies. Additional differential diagnoses include myxoedema, amyloidosis, lymphoedema, cellulitis, dermatomyositis, trichinosis and oedema of cardiac or renal origin.

Complications and co-morbidities

Systemic involvement in scleredema is not frequent. Extracutaneous complications (in all forms) include serositis, dysarthria, dysphagia, myositis, parotitis, hepatosplenomegaly and ocular and cardiac abnormalities [9].

Disease course and prognosis

Prognosis is largely dependent on the underlying aetiology. Post-infectious scleredema runs a benign course because it is self-limiting in duration and resolves spontaneously within 6 months to 2 years. Scleredema associated with diabetes or monoclonal gammopathy runs a chronic and disabling course with little tendency to remission. Rarely death may occur when internal organs are involved.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations are useful for detecting an underlying disorder. A recent infection should be excluded (with throat swab culture and antistreptolysin titres). Fasting blood glucose or glycosylated haemoglobin measurements and serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation should be obtained. Ultrasonography can be performed to evaluate skin thickness at baseline and after treatment while magnetic resonance imaging may be useful for determining the extent of disease progression due to better soft-tissue contrast than ultrasound evaluation [10].

Management

The therapy of scleredema is quite difficult and has limited success. At present, no effective treatment is known for this disease. For patients with disabling manifestations, initial treatment with phototherapy is suggested as first choice (grade of recommendation: weak). UVA1, PUVA and narrow-band UVB have all been found to be effective [11, 12]. Therapy is unnecessary for scleroderma associated with streptococcal infections because it resolves spontaneously. In patients with associated conditions, the disorder can resolve or improve if treatment of the primary disease is successful. In patients with scleredema-associated multiple myeloma, therapy targeting the plasma cell dyscrasia such as bortezomib may be effective [13]. Some but not all patients with diabetes-associated scleredema appear to improve with better glucose control. Other therapies that have been tried, with reduced patient numbers and overall limited success, include immunosuppressive agents such as ciclosporin A and methotrexate, high-dose penicillin, corticosteroids (local, intralesional and systemic), tamoxifen and allopurinol [14]. Electron-beam radiotherapy and extracorporeal photopheresis may also give some improvement [15, 16]. Intravenous immunoglobulin seems to be a promising therapy [17]. Patients with motion or respiratory disability should be referred to a physical therapist for musculoskeletal rehabilitation.

Myxoedema in thyroid diseases

Localized (pretibial) myxoedema

Definition and nomenclature

Localized (pretibial) myxoedema is an infiltrative dermopathy due to mucin deposition, usually arising on the shins. It is one of the signs of hyperthyroidism, especially of Graves disease [1].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Localized (pretibial) myxoedema is found in 1–5% of patients with Graves disease, but in up to 25% of patients who have exophthalmus. Women are affected more often than men (3 : 1) with a peak of incidence at age 50–60 years [2].

Pathophysiology

The demonstration of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor protein expression by normal dermal fibroblasts suggests that thyroid- stimulating hormone receptor antibodies may stimulate the production of mucin from these cells. Some cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α and γ interferon secreted by T helper 1 lymphocytes activated by thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antigen could also induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis from fibroblasts. Fibroblasts from the dermis of the lower extremities have been found to be more sensitive to this factor than are fibroblasts from other areas of the body [2–5]. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor antibodies, trauma, tobacco and lymphatic obstruction may also play a role.

Pathology

Histopathology reveals hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging, acanthosis and sometimes papillomatosis. The reticular dermis, particularly the mid to the lower part, shows separation of collagen bundles by large quantities of mucin. A perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and an increase in mast cells may be found with normal or increased number of fibroblasts. Elastic fibres are reduced in number [2].

Clinical features

Pretibial myxoedema is one of the signs of Graves disease (along with goitre, exophthalmus, thyroid acropathy, and high circulating levels of long-acting thyroid-stimulating hormone). Less commonly, it has been described with Hashimoto thyroiditis and in patients with no past or present history of thyroid dysfunction. It is characterized by bilateral thickening and induration of the skin on the shins and dorsa of the feet. There are four main clinical variants: diffuse non-pitting oedema (43%) (Figure 59.13); plaque type (27%); nodular (18%) (Figure 59.14); and elephantiasis (5%) (Figure 59.15) [2, 6]. The lesions can vary in colour and may exhibit a characteristic orange peel appearance and texture due to prominent hair follicles. The toes, thighs, upper extremities and face can be involved (Figure 59.16) [7]. Overlying hyperhidrosis or hypertrichosis may be associated.

Figure 59.13 Pretibial myxoedema with diffuse non-pitting oedema and plaque-like lesions on the legs.

Figure 59.14 Pretibial myxoedema of nodular type.

Figure 59.15 Elephantiasic pretibial myxoedema.

(Courtesy of B. Cribier, MD, Strasbourg, France.)

Figure 59.16 Localized myxoedema on the preradial area. Note the orange peel appearance.

(Courtesy of S. Verma, MD, Vadodara, Gujarat, India.)

Differential diagnosis

In addition to lichen simplex chronicus and hypertrophic lichen planus in which mucin is lacking, pretibial myxoedema should be differentiated from obesity-associated lymphoedematous mucinosis seen in patients without thyroid disease [8].

Disease course and prognosis

Apart from the appearance, associated morbidity is usually not severe, except for patients with elephantiasis who are less likely to have remission. Entrapment of peroneal nerves by mucinous connective tissue may cause foot drop or faulty dorsiflexion.

Investigations

Thyroid-stimulating hormone is abnormally low and long-acting thyroid stimulator antibodies are elevated in 50% of patients with Graves disease.

Management

The initial treatment includes minimizing risk factors, such as reducing weight, reducing tobacco use and normalizing thyroid function. However, therapy for the associated hyperthyroidism does not improve the cutaneous lesions and, often, localized myxoedema develops after treatment has been instituted. Severe myxoedema is most often encountered in patients with longstanding untreated Graves thyroid disease. The first line of pharmacological therapy is medium to high potency topical corticosteroids applied under occlusive dressings or delivered by intralesional injection (grade of recommendation: weak) [2, 9, 10]. For the severe elephantiasic form, rituximab, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins and octreotide with and without surgical shave removal have been tried with some benefit in uncontrolled case reports [11–13]. Usually, skin grafting is followed by relapse. The use of compression stockings and gradient pneumatic compression is useful as it improves lymphedema. Localized myxoedema may clear spontaneously (on average after 3.5 years) [14].

Papular and nodular mucinosis in connective tissue diseases

Definition

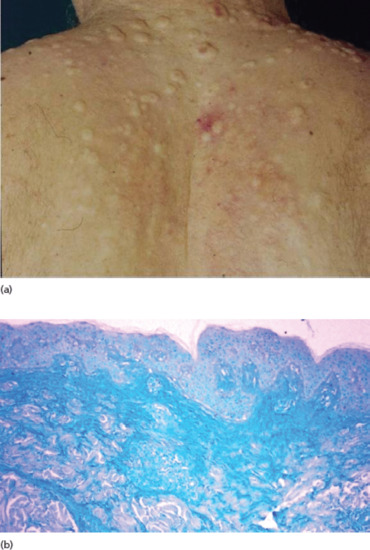

A distinctive cutaneous mucinosis characterized by skin-coloured papules, nodules (Figure 59.17a) and plaque-like lesions on the trunk and upper extremities may accompany or even antedate a connective tissue disease, mostly lupus erythematosus (cutaneous lupus mucinosis) and rarely dermatomyositis or scleroderma [1].

Figure 59.17 (a) Papular and nodular mucinosis in connective tissue disease. (b) Abundant mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis (Alcian blue stain).

Epidemiology

Cutaneous lupus mucinosis occurs in 1.5% of patients with lupus erythematosus in the fourth and fifth decades of life, with a predominance of adult males in Asian patients and females in Caucasian cases [2].

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis is unknown but increased glycosaminoglycan production by dermal fibroblasts stimulated by some cytokines or immunoglobulins, or an abnormal immune response linked to human leukocyte antigens HLAB8 and HLADR3 haplotypes have been suggested [1, 2].

Pathology

Histologically, mucin is abundant throughout the dermis and sometimes subcutaneous fat (Figure 59.17b), occasionally in association with a slight to moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. The epidermal changes of lupus erythematosus are absent or mild, but a positive lupus band is seen on direct immunofluorescence [1, 2].

Clinical features

The clinical course may or may not be related to the underlying connective tissue disease activity. Usually, patients with lupus erythematosus who develop papular and nodular mucinosis have systemic disease in about 75% of cases, but discoid and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus may also be associated with it. Periorbital mucinosis is an unusual presentation [3]. Cutaneous mucinosis in dermatomyositis usually follows the myositis and is characterized by erythematous nodules and plaque-like lesions on the trunk [4]. The development of papular and nodular mucinosis has also been associated with scleroderma both the systemic and the cutaneous form [5].

Management

Therapy of papular and nodular mucinosis is the same as for the connective tissue disease. However, the evolution of the mucinoses does not always follow the course of the underlying disease. Sunscreens, topical or intralesional corticosteroids, and oral antimalarials can be effective in cutaneous lupus mucinosis. Systemic corticosteroids and oral tacrolimus are used for resistant cases [6].

Self-healing cutaneous mucinosis

Definition

A self-healing mucinosis affecting young people with transient cutaneous lesions and mild inflammatory symptoms.

Introduction and general description

Self-healing juvenile cutaneous mucinosis is a rare disease of unknown aetiology occurring in young people (from 13 months to 15 years of age) characterized by transient cutaneous lesions and sometimes mild inflammatory symptoms [1].

Pathophysiology

Abnormal mucin production and fibroblast proliferation are suggested to be secondary to a reactive or reparative response to chronic antigenic stimulation, as can occur in viral infection or inflammation.

Pathology

Histologically, papular lesions show mucin deposition with mild inflammation and a small increase in fibroblasts while nodules show deep mucinous areas associated with bands of fibrosis, multiple capillaries, fibroblastic proliferation and gangliocyte-like giant cells in the subcutis consistent with nodular or proliferative fasciitis [2].

Clinical features

Self-healing cutaneous mucinosis is characterized by the following criteria: (i) acute eruption of multiple papules, sometimes in linear infiltrated plaques, on the face, neck, scalp, abdomen and thighs; (ii) mucinous subcutaneous nodules on the face with periorbital swelling and on periarticular areas of the limbs which sometimes are the predominant lesions (Figure 59.18); (iii) systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgias, weakness and muscle tenderness in the absence of paraproteinaemia, bone marrow plasmocytosis and thyroid dysfunction; and (iv) spontaneous resolution in a period ranging from a few weeks to many months (usually from 2 to 8) [1]. It has also been described in adults [3].

Figure 59.18 Self-healing cutaneous mucinosis. Mucinous subcutaneous nodules and papules on the periarticular areas of the hand in a child.

Management

Despite the worrying presentation, the disease heals spontaneously and aggressive therapy should be avoided.

Cutaneous focal mucinosis

Definition

Cutaneous focal mucinosis is a benign localized form of cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Introduction and general description

Cutaneous focal mucinosis is a benign localized form of cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Epidemiology

Cutaneous focal mucinosis occurs in adults of either sex but it has also been reported in children [1].

Pathophsiology

Cutaneous focal mucinosis is a reactive lesion in which trauma may act as a trigger [1].

Pathology

The histology is essential for diagnosis and shows a diffuse ill-defined dermal accumulation of mucin, sparing subcutaneous tissue, with normal or slight increase of fibroblasts and absence of inflammation [1, 2]. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts are the predominant cell type, with occasional admixed factor XIIIa-positive dendritic cells. The epidermis may be normal or hyperplastic, sometimes forming a collarette. Additionally, absence of elastic fibres without increased vascularity is seen.

Clinical features

Cutaneous focal mucinosis presents as an asymptomatic solitary skin-coloured papule or nodule, sometimes with cystic appearance, that can occur anywhere on the body (Figure 59.19) or in the oral cavity, but not in proximity to the joints of the hands, wrists or feet [1]. Occasionally, cutaneous focal mucinosis has been reported as a soft fibroma-like polyp or a plaque-like lesion [2, 3]. Multiple lesions have been rarely described [4].

Figure 59.19 Cutaneous focal mucinosis. A solitary whitish papule with cystic appearance.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis is with angiomyxoma, a benign neoplasm which is larger (size over 1 cm), and shows subcutaneous involvement by mucin and increased vascularity [5].

Complications and co-morbidities

Contrary to other forms of primary mucinoses, cutaneous focal mucinosis is not usually related to systemic manifestations. Anecdotal associations with hypothyroidism and myxoedema or other forms of mucinoses such as scleromyxoedema and REM, and with antitumour necrosis factor α therapy, have been described [4, 6].

Management

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice and relapse is uncommon.

Digital myxoid (mucous) cyst

Definition

Digital myxoid cyst is a benign ganglion cyst of the digits.

Epidemiology

Women are affected more than twice as often as men.

Pathophysiology

There are two varieties of lesion: ganglion type derived from joint fluid and synovial cells, which is located over the joints; and myxomatous type, derived from dermal-based fibroblasts, which is located between the interphalangeal joints.

Pathology

Histopathological features show a large deposit of mucin-containing stellate fibroblasts, some vascular spaces and multiple clefts. The overlying epidermis is acanthotic laterally and more atrophic centrally. Transepidermal elimination of mucoid material may be seen.

Clinical features

It is a translucent dome-shaped soft or fluctuant 3–10 mm nodule with or without visible semi-transparent contents located on the dorsal skin on or near a distal interphalangeal joint of the finger in middle-aged patients (Figure 59.20) [1]. Cysts may also be found on the toes. The surface may be smooth or verrucous. Subungual and multiple forms have been reported [2]. Clinical and radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis is common. Grooving of the nail may associate or even precede the cyst itself by up to 6 months [3]. Antecedent trauma has been documented in a small minority of cases. A connection of the ganglion cyst to the underlying joint can be shown by means of magnetic resonance imaging [4]. Puncture or biopsy results in the drainage of viscous mucin from the cyst.

Figure 59.20 Digital myxoid cyst. A translucent dome-shaped nodule on the distal interphalangeal joint of the finger.

Management

None of the existing treatments is consistently successful. Digital myxoid cyst can be excised but relapse is not uncommon and many dermatologists tend to favor more conservative treatments such as multiple needling or aspiration followed by steroid injection, sclerosant injection, cryotherapy, infrared coagulation or CO2 laser [5].

FOLLICULAR MUCINOSES

Mucin accumulates in the epithelial hair follicle sheaths and sebaceous glands in two primary (idiopathic) distinctive clinical disorders: Pinkus follicular mucinosis and urticaria-like follicular mucinosis [1]. Follicular mucinosis can also occur as a histological epiphenomenon most often seen in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (see Chapter 140) and other skin diseases [2].

Pinkus follicular mucinosis

Definition and nomenclature

Pinkus follicular mucinosis is an uncommon inflammatory disorder, apparently not linked with lymphoma, that has a predilection for children, and for adults in the third and fourth decades of life [1].

Pathophysiology

It is far from clear why dermal-type mucin is deposited selectively within an epithelial structure. Although follicular keratinocytes have been considered to be the source of the mucin, an aetiological role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms has been proposed. A reaction to persistent antigens such as Staphylococcus aureus has also been considered [1]. Familial cases suggest a genetic predisposition [3].

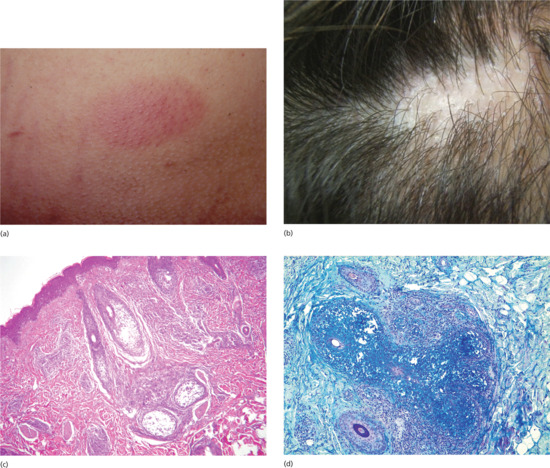

Pathology

Mucin accumulates within the follicular epithelium and sebaceous glands causing keratinocytes to disconnect from each other (Figure 59.21c, d). In more advanced lesions, the follicles are converted into cystic spaces containing mucin, inflammatory cells and altered keratinocytes. A perifollicular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and eosinophils is seen. The differentiation between Pinkus follicular mucinosis and mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis is very difficult and there is no single reliable criterion. Although the existence of primary follicular mucinosis has been questioned, as it has been considered as an ‘indolent’ localized form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, clues in favour of a primary form are the young age of the patient, a solitary lesion on the head or neck and the absence of histological features of epidermotropism or atypical lymphocytes [4, 5]. Clonal T-cell rearrangement is not always useful to differentiate the two types. In these cases, clinical follow-up is mandatory.

Figure 59.21 (a) Pinkus follicular mucinosis. A sharply demarcated erythematous plaque with follicular prominence. (b) Alopecic plaque in follicular mucinosis. (c) Mucin accumulates within the follicular epithelium and sebaceous glands causing keratinocytes to disconnect. (d) Follicular mucin stained with Alcian blue.

Clinical features

Pinkus follicular mucinosis presents as an acute or subacute eruption characterized by one or several sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with follicular prominence (Figure 59.21a), scaling and alopecia (Figure 59.21b) [1, 5]. Nodules, annular plaques, folliculitis, follicular spines, acneform eruptions and alopecia areata-like presentation [6] have also been described. A second type which is characterized by a more generalized chronic form in a slightly older age group, with larger and more numerous plaques on the extremities, trunk and face, is probably best regarded as a follicular mucinosis associated with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma rather than a primary condition.

Management

There is no specific treatment for Pinkus follicular mucinosis [3]. A wait and see approach should be considered as many cases heal spontaneously in 2–24 months. Topical, intralesional and systemic corticosteroids, topical retinoids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical bexarotene, imiquimod, dapsone, antimalarials, indometacin, minocycline, oral isotretinoin, interferon α-2b, photodynamic therapy and UVA1 phototherapy have been reported to be of benefit on an anecdotal basis [7–9].

Urticaria-like follicular mucinosis

Definition

A follicular mucinosis presenting with a cyclic eruption of urticaria-like lesions on the face on a ‘rosaceiform or seborrhoeic’ background.

Introduction and general description

This is a very rare cyclic eruption of urticaria-like lesions that occurs primarily on the head of middle-aged men [10] in the absence of systemic manifestations.

Pathology

On histopathological examination urticaria-like follicular mucinosis presents with mucin deposition inside the hair follicles associated with a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Rearrangement of T-cell receptors is more frequently polyclonal and it is not decisive in the differential diagnosis.

Clinical features

Urticaria-like follicular mucinosis presents with recurrent pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of the face and neck on a ‘rosaceiform or seborrhoeic’ background. As lesions resolve, red macules persist for a few weeks. Hair-bearing regions may be involved, but neither follicular plugging nor alopecia is seen. The diagnosis is usually delayed since the dermatitis is often misinterpreted as urticaria, seborrhoeic dermatitis, rosacea or lupus tumidus before a biopsy is taken.

Management

Urticaria-like follicular mucinosis has a good prognosis although it may last up to 15 years. Therapy is difficult. Antimalarials and dapsone have been reported as beneficial [10].

SECONDARY MUCINOSES

Secondary cutaneous mucinoses include all those entities in which mucin deposition simply represents an additional histological finding and not the main feature (see Box 59.1) [1].

References

Introduction and general description

- Rongioletti F. Mucinoses. In: Rongioletti F, Smoller BR, eds. Clinical and Pathological Aspects of Skin Diseases in Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional and Deposition Disease. New York: Springer, 2010:139–52.

- Warner TF, Wrone DA, Williams EC, Cripps DJ, Mundhenke C, Friedl A. Heparan sulphate proteoglycan in scleromyxedema promotes FGF-2 activity. Pathol Res Pract 2002;198:701–7.

- Tominaga A, Tajima S, Ishibashi A, Kimata K. Reticular erythematous mucinosis syndrome with an infiltration of factor XIIIa+ and hyaluronan synthase 2+ dermal dendrocytes. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:141–5.

- Chang LM, Maheshwari P, Werth S, et al. Identification and molecular analysis of glycosaminoglycans in cutaneous lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. J Histochem Cytochem 2011;59:336–45.

- Rongioletti F, Barnhill R. Deposition disorders. In: Barnhill R, Crowson N, Magro C, Piepkorn M, eds. Dermatopathology, 3rd edn. New York, McGraw, 2010.

- Docampo MJ, Zanna G, Fondevila D, et al. Increased HAS2-driven hyaluronic acid synthesis in Shar-Pei dogs with hereditary cutaneous hyaluronosis (mucinosis). Vet Dermatol 2011;22:535–45.

Primary mucinoses

Dermal mucinoses

Lichen myxoedematosus (papular mucinosis)

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2006;25:100–4.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:66.

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, Heymann WR. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:493–7.

- Harper RA, Rispler J. Lichen myxedematosus serum stimulates human skin fibroblast proliferation. Science 1978;199:545–7.

- Ferrarini M, Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, et al. Scleromyxedema serum increases proliferation but not the glycosaminoglycan synthesis of dermal fibroblasts. J Rheumatol 1989;16:837–41.

- Yaron M, Yaron I, Yust I, Brenner S. Lichen myxedematosus (scleromyxedema) serum stimulates hyaluronic acid and prostaglandin E production by human fibroblasts. J Rheumatol 1985;12:171–5.

- Rongioletti F, Cattarini G, Sottofattori E, Rebora A. Granulomatous reaction after intradermal injections of hyaluronic acid gel. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:815–16.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol 2001;23:257–67.

- Rongioletti F, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Scleromyxedema with an interstitial granulomatous-like pattern: a rare histologic variant mimicking granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:1084–7.

- Delyon J, Bézier M, Rybojad M, et al. Specific lymph node involvement in scleromyxedema: a new diagnostic entity for hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy. Virchows Arch 2013;462:679–83.

- Nashel J, Steen V. Scleroderma mimics. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:39.

- Chan JC, Trendell-Smith NJ, Yeung CK. Scleromyxedema: a cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome associated with thymic carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:e27–9.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:37–43.

- Rongioletti F, Hazini A, Rebora A. Coma associated with scleromyxoedema and interferon alfa therapy. Full recovery after steroids and cyclophosphamide combined with plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:1283–4.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato–neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 2012;39:508–17.

- Pomann JJ, Rudner EJ. Scleromyxedema revisited. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:31–5.

- De Simone C, Castriota M, Carbone A, et al. Cardiomyopathy in scleromyxedema: report of a fatal case. Eur J Dermatol 2010;20:852–3.

- Le Moigne M, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Bonnetblanc JM, et al. [Clinical characteristics, outcome of scleromyxoedema: a retrospective multicentre study.] Ann Dermatol Venereol 2010;137:782–8.

- Lee YH, Sahu J, O'Brien MS, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis-like acute renal failure associated with mucopolysaccharide accumulation in renal vessels in a patient with scleromyxedema. J Clin Rheumatol 2011;17:318–22.

- Loggini B, Pingitore R, Avvenente A, et al. Lichen myxedematosus with systemic involvement: clinical and autopsy findings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:606–8.

- Blum M, Wigley FM, Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema: a case series highlighting long-term outcomes of treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:10–20.

- Rey JB, Luria RB.Treatment of scleromyxedema and dermatoneuro syndrome with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:1037–41.

- Bidier M, Zschoche C, Gholam P, et al. Scleromyxoedema: clinical follow-up after successful treatment with high-dose immunoglobulins reveals different long-term outcomes. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:408–9.

- Sansbury JC, Cocuroccia B, Jorizzo JL, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant scleromyxedema with thalidomide in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:126–31.

- Efthimiou P, Blanco M. Intravenous gammaglobulin and thalidomide may be an effective therapeutic combination in refractory scleromyxedema: case report and discussion of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008;38:188–94.

- Horn KB, Horn MA, Swan J, et al. A complete and durable clinical response to high-dose dexamethasone in a patient with scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:S120–3.

- Lin YC, Wang HC, Shen JL. Scleromyxedema: An experience using treatment with systemic corticosteroid and review of the published work. J Dermatol 2006;33:207–10.

- Brunet-Possenti F, Hermine O, Marinho E, et al. Combination of intravenous immunoglobulins and lenalidomide in the treatment of scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:319–20.

- Bos R, de Waal EG, Kuiper H, et al. Thalidomide and dexamethasone followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for scleromyxoedema. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1925–6.

- Cañueto J, Labrador J, Román C, et al. The combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone is an efficient therapy for relapsed/refractory scleromyxedema: a rare disease with new clinical insights. Eur J Haematol 2012;88:450–4.

- Fett NM, Toporcer MB, Dalmau J, et al. Scleromyxedema and dermato–neuro syndrome in a patient with multiple myeloma effectively treated with dexamethasone and bortezomib. Am J Hematol 2011;86:893–6.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A, Crovato F. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: a new entity. Arch Dermatol 1986;122:1237–9.

- Callaly EL, Mulligan N, Powell FC. Multiple painless papules on the wrists. Diagnosis: acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM). Arch Dermatol 2007;143:791–6.

- Concheiro J, Pérez-Pérez L, Peteiro C, Labandeira J, Toribio J. Discrete papular lichen myxoedematosus: a rare subtype of cutaneous mucinosis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:e608–1.

- Podda M, Rongioletti F, Greiner D, et al. Cutaneous mucinosis of infancy: is it a real entity or the paediatric form of lichen myxoedematosus (papular mucinosis)? Br J Dermatol 2001;144(3):590–3.

- Ogita A, Higashi N, Hosone M, Kawana S. Nodular-type lichen myxedematosus: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol 2010;17;2:195–200.

- Scheidegger EP, Itin P, Kempf W. Familial occurrence of axillary papular mucinosis. Eur J Dermatol 2005;15:70–2.

- Haught JM, Serrao R, English JC 3rd. Localized cutaneous mucinosis after joint replacement. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1399–400.

- Gómez-Bernal S, Ruiz-González I, Delgado-Vicente S, Alonso-Alonso T, Rodríguez-Prieto MÁ. Plaque-like cutaneous mucinosis after joint replacement. J Cutan Pathol 2012;39:562–4.

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:530–2.

- André Jorge F, Mimura Cortez T, Guadalini Mendes F, Esther Alencar Marques M, Amante Miot H. Treatment of acral persistent papular mucinosis with electrocoagulation. J Cutan Med Surg 2011;15:227–9.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis

- Rongioletti F, Merlo V, Riva S, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: a review of patients characteristics, associated conditions, therapy and outcome in 25 cases. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:1207–11.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lien MH, Fenske NA. Reticular erythematous mucinosis – a review. Int J Dermatol 2012;51:903–9.

- Izumi T, Tajima S, Harada R, Nishikawa T. Reticular erythematous mucinosis syndrome: glycosaminoglycan synthesis by fibroblasts and abnormal response to interleukin-1 beta. Dermatology1996;192:41–5.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Tourlaki A, Marchini M. Reticular erythematous mucinosis occurring in a brother and sister. Dermatology 2006;212:385–7.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol 2001;23:257–67.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, Rebora A, Parodi A. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol 2010;20:797–801.

- Kreuter A, Scola N, Tigges C, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Clinical features and efficacy of antimalarial treatment for reticular erythematous mucinosis: a case series of 11 patients. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:710–15.

- Rubegni P, Sbano P, Risulo M, Poggiali S, Fimiani M. A case of reticular erythematous mucinosis treated with topical tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:173–4.

- Mansouri P, Farshi S, Nahavandi A, Safaie-Naraghi Z. Pimecrolimus 1 percent cream and pulsed dye laser in treatment of a patient with reticular erythematous mucinosis syndrome. Dermatol Online J 2007;1;13:22.

- Amherd-Hoekstra A, Kerl K, French LE, Hofbauer GF. Reticular Erythematous Mucinosis in an atypical pattern distribution responds to UVA1 phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;28:672–3.

- Miyoshi K, Miyajima O, Yokogawa M, Sano S. Favorable response of reticular erythematous mucinosis to ultraviolet B irradiation using a 308-nm excimer lamp. J Dermatol 2010;37:163–6.

Scleredema

- Venencie PY, Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Scleroedema: a review of 33 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:128–34.

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006;35:355–9.

- Lewerenz V, Ruzicka T. Scleredema adultorum associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a report of three cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:560–1.

- Rongioletti F, Ghigliotti G, De Marchi R, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses and HIV infection. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:1077–80.

- Morais P, Almeida M, Santos P, Azevedo F. Scleredema of Buschke following Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory infection. Int J Dermatol 2011;50:454–7.

- Oyama N, Togashi A, Kaneko F, Yamamoto T. Two cases of scleredema with pituitary–adrenocortical neoplasms: an underrecognized skin complication. J Dermatol 2012;39:193–4.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol 2001;23:257–67.

- Ioannidou DI, Krasagakis K, Stefanidou MP, et al. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke presenting as periorbital edema: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;65(2 Suppl. 1):41–4.

- Miyares FJ, Kuriakose R, Deleu DT, El-Wahad NA, Al-Hail H. Scleredema diabeticorum with unusual presentation and fatal outcome. Indian J Dermatol 2008;53:217–19.

- Kurihara Y, Kokuba H, Furue M. Case of diabetic scleredema: diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging. J Dermatol 2011;38:693–6.

- Xiao T, Yang ZH, He CD, Chen HD. Scleredema adultorum treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol 2007;34:270–2.

- Yüksek J, Sezer E, Köseolu D, Markoç F, Yıldız H. Scleredema treated with broad-band ultraviolet A phototherapy plus colchicine. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2010;26:257–60.

- Szturz P, Adam Z, Vašk V, et al. Complete remission of multiple myeloma associated scleredema after bortezomib-based treatment. Leuk Lymphoma 2013;54:1324–6.

- Lee FY, Chiu HY, Chiu HC.Treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with allopurinol incidentally improves scleredema diabeticorum. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:e115–17.

- Stables GI, Taylor PC, Highet AS. Scleredema associated with paraproteinaemia treated by extracorporeal photopheresis. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:781–3.

- Bowen AR, Smith L, Zone JJ. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke treated with radiation. Arch Dematol 2003;139:780–4.

- Aichelburg MC, Loewe R, Schicher N, et al. Successful treatment of poststreptococcal scleredema adultorum Buschke with intravenous immunoglobulins. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:1126–8.

Localized (pretibial) myxoedema

- Doshi DN, Blyumin ML, Kimball AB. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Clin Dermatol 2008;26:283.

- Fatourechi V. Thyroid dermopathy and acropachy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;26:553.

- Ai J, Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Autoimmune thyroid diseases: etiology, pathogenesis, and dermatologic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:641.

- Smith TJ, Hoa N. Immunoglobulins from patients with Graves' disease induce hyaluronan synthesis in their orbital fibroblasts through the self-antigen, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:5076.

- R.S. Douglas, S. Gupta. The pathophysiology of thyroid eye disease: implications for immunotherapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2011;22:385–90.

- Rapoport B, Alsabeh R, Aftergood D, McLachlan SM. Elephantiasic pretibial myxedema: insight into and a hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of the extrathyroidal manifestations of Graves' disease. Thyroid 2000;10:685.

- Verma S, Rongioletti F, Braun-Falco M, Ruzicka T. Preradial myxedema in a euthyroid male: A distinct rarity. Dermatol Online J 2013 15;19:9

- Rongioletti F, Donati P, Amantea A, et al. Obesity-associated lymphoedematous mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol 2009;36:1089–94.

- Engin B, Gümüşel M, Ozdemir M, Cakir M. Successful combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treatment of severe pretibial myxedema. Dermatol Online J 2007;13:16.

- Takasu N, Higa H, Kinjou Y. Treatment of pretibial myxedema (PTM) with topical steroid ointment application with sealing cover (steroid occlusive dressing technique: steroid ODT) in Graves' patients. Intern Med 2010;49:665.

- Heyes C, Nolan R, Leahy M, Gebauer K. Treatment-resistant elephantiasic thyroid dermopathy responding to rituximab and plasmapheresis. Australas J Dermatol 2012;53:e1–4.

- Felton J, Derrick EK, Price ML. Successful combined surgical and octreotide treatment of severe pretibial myxoedema reviewed after 9 years. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:825–6.

- Dhaille F, Dadban A, Meziane L, et al. Elephantiasic pretibial myxoedema with upper-limb involvement, treated with low-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012;37:307–8.

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DD, Pond GR. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:438.

Papular and nodular mucinosis in connective tissue diseases

- Rongioletti F, Smoller BR, eds. Clinical and Pathological Aspects of Skin Diseases in Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional and Deposition Disease. New York: Springer, 2010:146–7.

- Goerig R, Vogeler C, Keller M. Atypical presentation of cutaneous lupus mucinosis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013;6:37–40.

- Morales-Burgos A, Sánchez JL, Gonzalez-Chávez J, Vega J, Justiniano H. Periorbital mucinosis: a variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus? J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:667–71.

- del Pozo J, Almagro M, Martínez W, et al. Dermatomyositis and mucinosis. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:120–4.

- Van Zander J, Shaw JC. Papular and nodular mucinosis as a presenting sign of progressive systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:304–6.

- Sugiura K, Tanahashi K, Muro Y, Akiyama M. Cutaneous lupus mucinosis successfully treated with systemic corticosteroid and systemic tacrolimus combination therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:e200–2.

Self-healing cutaneous mucinosis

- Cowen EW, Scott GA, Mercurio MG. Self-healing juvenile cutaneous mucinosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:S97–100.

- Barreau M, Dompmartin-Blanchère A, Jamous R, et al. Nodular lesions of self-healing juvenile cutaneous mucinosis: a pitfall! Am J Dermatopathol 2012;34:699–705.

- Sperber BR, Allee J, James WD. Self healing papular mucinosis in an adult. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:121–3.

Cutaneous focal mucinosis

- Kempf W, von Stumberg B, Denisjuk N, Bode B, Rongioletti F. Trauma-induced cutaneous focal mucinosis of the mammary areola: an unusual presentation. Dermatopathology (Karger) 2014;1:24–8.

- Nebrida ML, Tay YK. Cutaneous focal mucinosis: a case report. Ped Dermatol 2002;19:33–5.

- Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Isobe T, Aikawa Y, Tsuboi R. Plaque-type cutaneous focal mucinosis. Int J Dermatol 2011;50:896–8.

- Duparc A, Gosset P, Lasek A, Modiano P. [Multiple lesions of focal cutaneous mucinosis: a side-effect of anti-TNF alpha therapy?] Ann Dermatol Venereol 2010;137:140–2.

- Misago N, Mori T, Yoshioka M, Narisawa Y. Digital superficial angiomyxoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32:536–8.

- Rongioletti F, Amantea A, Balus L, Rebora A. Cutaneous focal mucinosis associated with reticular erythematous mucinosis and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:656–7.

Digital myxoid (mucous) cyst

- Li K, Barankin B. Digital mucous cysts. Cutan Med Surg 2010;14:199–206.

- Bessis D, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple cutaneous myxoid cysts with transepidermal elimination. Br J Dermatol 2008;159:988–90.

- Lin YC, Wu YH, Scher RK. Nail changes and association of osteoarthritis in digital myxoid cyst. Dermatol Surg 2008;34:364–9.

- Bermejo A, De Bustamante TD, Martinez A, Carrera R, Zabía E, Manjón P. MR imaging in the evaluation of cystic-appearing soft-tissue masses of the extremities. Radiographics 2013;33:833–55.

- Lonsdale-Eccles AA, Langtry JA. Treatment of digital myxoid cysts with infrared coagulation: a retrospective case series. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:972.

Follicular mucinoses

- Rongioletti F, Smoller BR. Clinical and Pathological Aspects of Skin Diseases in Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional and Deposition Disease. New York: Springer, 2010.

- Mir-Bonafé JM, Cañueto J, Fernández-López E, Santos-Briz A. Follicular mucinosis associated with nonlymphoid skin conditions. Am J Dermatopathol 2013 (epub ahead of print).

- Weir G, Burns E, Fraga G, Aires D. Familial follicular mucinosis: a case letter. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:e291–2.

- Alikhan A, Griffin J, Nguyen N, Davis DM, Gibson LE. Pediatric follicular mucinosis: presentation, histopathology, molecular genetics, treatment, and outcomes over an 11-year period at the Mayo Clinic. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:192–8.

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:15–19.

- Muscardin LM, Capitanio B, Fargnoli MC, Maini A. Acneiform follicular mucinosis of the head and neck region. Eur J Dermatol 2003;13:199–202.

- Schneider SW, Metze D, Bonsmann G. Treatment of so-called idiopathic follicular mucinosis with hydroxychloroquine. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:420–3.

- Parker SR, Murad E. Follicular mucinosis: clinical, histologic, and molecular remission with minocycline. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:139–41.

- Heyl J, Mehregan D, Kado J, Campbell M. A case of idiopathic follicular mucinosis treated with bexarotene gel. Int J Dermatol 2014;53:838–41.

- Cinotti E, Basso D, Donati P, Parodi A, Rongioletti F. Urticaria-like follicular mucinosis: four new cases of a controversial entity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e435–7.

Secondary mucinoses

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol 2001;23:257–67.