CHAPTER 86

Psychodermatology and Psychocutaneous Disease

Anthony Bewley1 and Ruth E. Taylor2

1Department of Dermatology, Barts Health NHS Trust, London; and Queen Mary College of Medicine, University of London, London, UK

2Department of Liaison Psychiatry, Barts Health NHS Trust, London; and Queen Mary College of Medicine, University of London, London, UK

Introduction

What is psychodermatology?

The links between the mind and the skin have long been recognized. The skin has been described as the mirror of the mind, and so it is not surprising that the interface between dermatology and psychiatry (’psychocutaneous medicine’ or ’psychodermatology’) is emerging as a specific subspeciality of dermatology. Psychodermatology is an increasingly recognized and important branch of dermatology. It encompasses disease that involves the complex interaction between the brain, the cutaneous nerves, the cutaneous immune system and the skin. Patients with psychocutaneous disease are often variably managed as dermatologists struggle, in general dermatology clinics, to meet the complex needs of these patients. Most patients with psychocutaneous disease are reluctant to attend purely psychiatric clinics. For these reasons, over the last few decades, the sub-specialty of psychodermatology has emerged to address the clinical–academic needs of this group of patients.

Skin–psyche interactions may be any of the following:

- Primarily cutaneous disorders that can be substantially influenced by psychological factors, e.g. psoriasis.

- Primary psychiatric disease presenting to dermatology health care professionals (HCPs), e.g. delusional infestation, body dysmorphic disorder.

- Psychiatric illness developing as a result of skin disease, e.g. depression, anxiety or both.

- Co-morbidity of skin disease with another psychiatric disorder, e.g. alcoholism.

Psychodermatology multidisciplinary teams

Though patients often present to the dermatology department, dermatologists will usually need the support of a variety of colleagues in managing patients with psychodermatological disease. For these patients, there is increasing evidence that a psychodermatology multidisciplinary team (MDT) can improve outcomes [1,2]. Specialists who make up a psychodermatology MDT (Box 86.1) require dedicated training in the management of patients with psychocutaneous disease. Such training is not always readily available, but national and international groups are now becoming pre-eminent in meeting the training needs of the psychodermatology MDT, as well as championing the clinical–academic development of the subspeciality (Box 86.2).

Models of provision of psychodermatology services

There are several models of how psychodermatology services are delivered, all of which are compatible with a psychodermatology MDT. These include:

- A dermatologist who refers to a psychiatrist or psychologist as a clinical adjacency.

- A dermatologist who refers to a psychiatrist or psychologist who is in a remote clinic (who will be able to support and supevise decisions taken by a dermatologist).

- A dermatologist who has a psychiatrist sitting in the clinic at the same time. Patients are seen by both specialists concurrently.

- A dermatologist who has a psychologist as a clinical adjacency (psychologists rarely sit in on clinics with dermatologists or psychiatrists).

Classification

Classification of psychodermatological disease is useful, but more complicated than it may first appear [1]. The American Psychiatric Association has published the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders 5 or DSM-5 [2]. The aim of the DSM manual is to provide general categorizations and diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders. These manuals are tools for HCPs and do not represent a substitute for expert clinical opinion. The World Health Organization's International Classification of Disease 10 or ICD-10 offers a general classification of all disease rather than specifically psychiatric/psychological disease [3]. ICD-11 is due for publication [4].

Psychological co-morbidities of chronic skin disease and the ’golden rules of psychodermatology’

Psychological stress is an integral cause of skin disease either as an initiating or an exacerbating factor leading to increased disease morbidity (see Chapter 11). It is therefore essential that the skin condition is treated concomitantly with the psychological co-morbidities (or the psychiatric/psychological aetiology). Part of the ’appropriate treatment’ of concomitant psychiatric/psychological disease is the assessment of risk and suicidality that should be in one's mind for every dermatology consultation. Treating the skin disease without treating the psychiatric/psychological disease makes no sense and yet a lot of training in dermatology makes little reference to the treatment of psychological disease. This leads to the golden rules of psychodermatology:

- Exclude organic disease.

- Appropriately assess and treat the dermatological disease at the same time as appropriately assessing and treating the psychological disease.

The following four discussions of different diseases illustrate the principle.

- Atopic eczema. The complex biopsychosocial realities of living with atopic eczema are clear (see www.atopicskindisease.com for useful information; last accessed August 2015). Atopic children and adolescents show more anxiety, handle situations less well and are provoked to anger more readily. In school and college, the psychosocial issues of mixing in peer groups and making personal relationships may be blighted by feelings of stigmatization and disfigurement. Stress makes atopic eczema worse [1]. Psychotherapies have a part to play in the holistic (skin and psychosocial) treatment plan.

- Psoriasis. Psoriasis is much more than a skin disease. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of patients with psoriasis show changes in the brain in response to ’disgust’ images [2]. Anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation are more common than in patients with eczema, acne or alopecia [3]. Depression is particularly significant and may remain undetected but is important because patients need to be treated holistically in order to improve [4]. Many patients indicate that stress has triggered the onset of the skin disease, but the latent period between a significant life stress and the onset or exacerbation of psoriasis has been difficult to assess. The response to phototherapy in highly worried individuals was almost half that of those who were deemed to have low worry and was constant for disease severity, disease duration, gender, age and skin type [5].

- Chronic urticaria. Chronic spontaneous urticaria has a significant effect on quality of life. It is significantly associated with depression, dysthymia and anxiety. Psychological factors may be prominent at the onset and contribute to disease progression, and negative coping may be associated with exacerbations [6].

- Alopecia areata. There has always been a strong anecdotal belief that the onset and recurrence of alopecia areata is related to stress and major life events [7]. Management of the grieving process and the psychosocial implications of living with hair loss is very much part of managing the patient's disease. Individual case reports continue to record success with individual psychotherapy, or use of antidepressants, either imipramine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and not always in the presence of clinical depression [7].

Stigmatization, visible differences and coping strategies

The word stigma referred originally to a mark or brand on Greek slaves, distinguishing them from those who were free. The term describes the situation of an individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance. The stigmatized individual is normal until abnormalized by societal views. These events may occur early, for example in those afflicted by congenital skin problems, or later in individuals with an acquired visible difference. But stigma is not just confined to the alterations in the visible body. Stigmatization may be an issue following individual behaviours and social factors such as substance abuse and unemployment. Or stigmatization may be associated with psychiatric disease. In addition there are the population prejudices of ethnicity and religion.

Some common situations where stigma may be encountered by patients include the following.

- Physical visible differences: congenital naevi (e.g. port-wine stain), acquired visible differences such as vitiligo, widespread inflammatory skin disease, surgical or post-traumatic visible differences.

- Behavioural and social factors: alcoholism and substance misuse, imprisonment.

- Psychiatric disease and learning disabilities.

- Race and religion.

Stigmatization in later life may present a different perspective because the patient has become a physical stranger to themselves. This is most striking and obvious in those who have developed disfiguring facial scarring, but is also as valid for the patient with a late-onset dermatosis or those who suffer the odour of hidradenitis suppurativa. Patients who experience stigmatization often refer to the guilt and shame that inhibits them from seeking help.

Stigma in psychiatry

Some people may hold a negative image of those with mental illness [1]. As with skin disease, there is a traditional stereotyping from historical attitudes towards psychiatric patients. HCPs who do not work with psychiatric patients may be inexperienced in accommodating the needs of this group. The importance in reducing the impact of stigmatization [2] is better understood in relation to social exclusion theory, which holds that:

- Humans possess a fundamental motive to avoid exclusion from social groupings.

- Much social behaviour attempts to improve the chances of inclusion.

- Negative effect (including loneliness and depression) results when a person does not or cannot achieve a desired level of social inclusion [3].

The measurement of stigma in dermatology and psychiatry has tended to rely on general measures of mental health with depression and anxiety scores, but also with psychometric measures of self-esteem such as the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. This has been used to assess stigmatization in psoriasis and eczema as well as mental illness. Furthermore the stigma scale for mental illness [4], developed to examine discrimination, disclosure and potential positive reactions to mental illness, demonstrated that stigma scale scores were negatively correlated with global self-esteem. Interventions in dermatological stigmata are concentrated on firstly the reduction in visibility, and secondly psychological-based approaches to forestall stigmatization.

Help for the stigmatized begins with information control from both physician and family. Self-help and contact with patient advocacy groups can be invaluable, such as Changing Faces in the UK (Box 86.3). A tolerant and informed grouping allows the expression of the normal developmental skills of the individual. Methods to change entrenched reactions within society to physical and psychological difference are more difficult to evaluate.

Disability, quality of life and assessment in psychodermatology

Quality of life (QOL) is defined as an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad-ranging concept, affected in a complex way by the person's physical heath, psychological state, level of independence and social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment. Dermatologists increasingly understand that physical disease and QOL are intimately, but not linearly, associated. Patients with skin disease are often very clear that their disease has an impact on their lives. This impact may be huge or relatively minor. The amount of skin disease, though, does not correlate with the extent of psychosocial co-morbidity; nor does greater disease extent and longevity necessarily correlate with a lower QOL.

Managing patients holistically means that clinicians must be able to assess how the patient is feeling and what the impact of their disease is on their QOL. Assessments may be unstructured following Socratic question principles, or may be validated and reproducible tools (Box 86.4). There is a growing interest in cumulative QOL assessments (i.e. lifetime QOL).

There are some very short screening tools; for example the generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) two-question screen. If a patient answered affirmatively for either of the following questions, further assessment may be important.

- Question 1 During the past 4 weeks, have you been bothered by feeling worried, tense or anxious most of the time?

- Question 2 Are you frequently tense, irritable and having trouble sleeping?

These questions are used extensively in research, but are becoming increasingly important in everyday dermatology practice as they offer a standardized snapshot of patient psychosocial well-being (some research results also include scores of disease extent). There is an increasing recognition that it is not just the life of the patient affected by a skin disease, but also the lives of family, partners, carers and loved ones who are often affected by the patient's journey through treatment. Assessing the impact of disease on partners and family is crucial to the well-being of the patient. There is a growing interest in cumulative QOL scoring and meta-analyses of QOL tools.

DELUSIONAL BELIEFS

Introduction and general description

A true primary delusion is a false, unshakeable belief that arises from internal processes in a patient, which are not amenable to logic and are out of keeping with the person's educational and cultural background. Primary delusions can be an isolated phenomenon (a monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis such as delusional infestation) or part of a broader psychosis (e.g. schizophrenia). A secondary delusion more commonly occurs with affective disorder and the delusion is secondary to the mood (e.g. a nihilistic delusion in severe depression may influence the patient into believing that his/her skin is rotting away). The intensity with which a delusional belief is held may be varaible. Delusional infestation, for example, may arise as an overvalued idea, and this somewhat less intensely held belief may be more amenable to negotiation and reason [1].

Delusions of infestation

Introduction and general description

Delusional infestation (DI) is an uncommon, but very disabling, condition where the patient is convinced that s/he is infested with a mite, parasite, bacteria, worm, insect, virus or animate material [1]. As this is a delusional disorder, the patient will hold this belief unshakeably and very often tenaciously. The patient believes wholeheartedly that s/he is infested even though no infesting organism or material can be found by clinicians. Although delusions are usually unshakeable and fixed, a few patients present with an overstated ideation of infestation (i.e. the patient believes that it is possible rather than unshakeably convinced that s/he is infested despite all evidence to the contrary). Patients with DI will usually present to dermatologists and be extremely reticent about seeing psychiatrists; they will frequently consume large amounts of resources having often seen a wide range of HCPs whilst remaining unengaged with treatment [2]. Some special forms of DI exist:

- DI as a shared delusion (folie à deux, etc.). Family members, carers and friends may believe that they too are infested, or delusionally share the belief of the individual who is presenting with DI. This is common.

- DI by proxy. Patients complain that their child, pet or friend is infested despite all evidence to the contrary.

DI may be primary (no underlying cause is found) or a secondary (to concomitant organic or psychiatric disease). Approximately half of patients presenting with DI will have secondary DI. The condition is usually a monosymptomatic delusion in that most patients hold no other delusional beliefs (as in, for example, schizophrenia). Occasionally patients may have other delusional ideations (usually when the DI is secondary to a co-morbid psychotic disease). Most patients can ’see’ the infestation but some remain uncertain whether what they see is actually the infesting organism or some other material. Patients are often isolated and have lived with their disease for a long time. Many fail to be engaged with HCPs, as the latter may try to reason that the disease is ’all in their head’. However, patients’ lives are extremely disabled by their disease and they often find themselves unemployed, in debt (e.g. some patients, in an attempt to rid their home of the infesting organisms, repeatedly buy new furniture and carpets), isolated (as loved ones may become more and more exasperated) and distraught (many patients go to great lengths to wash or clean their bodies).

The terms used prior to DI are now inappropriate as they refer to ’phobias’ (DI is a delusional not a phobic disorder) and ’parasitosis’ (DI patients present with a range of infesting organisms and animate material, not just parasites).

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

These are unknown, but estimated at 17 per million people per year, although this is probably an underestimate.

Age

Delusional infestation can occur at any adult age but the peak incidence is said to be in 50-year-olds. It is rare in children although shared delusions in children of patients with DI have been reported.

Sex

The occurrence of DI is probably equally distributed in the sexes (as affected men present to clinicians much less with this disease than women), but is reported to occur in a ratio of male : female 1 : 2.5.

Ethnicity

Delusional infestation is found in all ethnicities.

Associated diseases

For diseases associated with secondary DI see Table 86.1.

Table 86.1 Diseases associated with or causing delusional infestation (DI).

| Primary DI | DI secondary to organic disease | DI secondary to psychiatric disease |

| No underlying disease | Substance abuse (Figure 86.1) Alcohol Recreational drugs Prescribed medications, e.g. anti-parkinsonian medication such as ropinerole Infections Tuberculosis HIV Endocrine disorders Thyroid disease Cancer Tumours Haematological cancer Chronic or acute liver disease Renal failure Metabolic disease Vitamin B12 deficiency Autoimmune disorders Systemic lupus erythematosus Multiple sclerosis Brain disorders Cerebrovascular disease Parkinson disease |

Schizophrenia Bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms Borderline personality disorder Anxiety disorder |

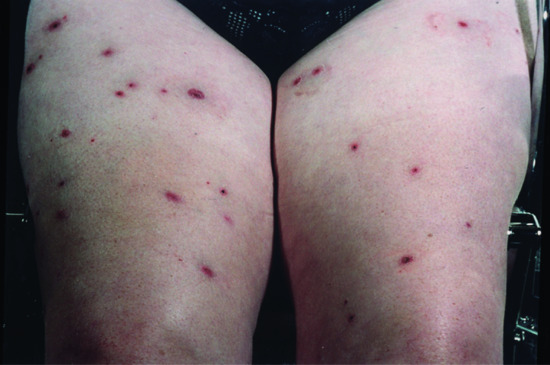

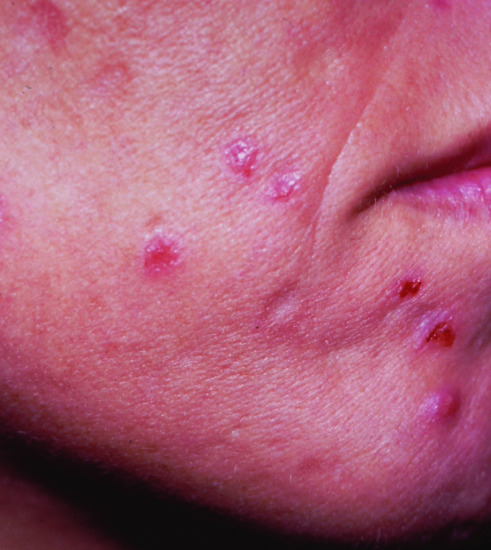

Figure 86.1 Excoriations in delusions of parasitosis in an amphetamine addict.

Pathophysiology

Many patients describe an initiating event. This can be a real insect bite, a misinterpretation of a real perception (an illusion) or a true hallucination (sensory experience in the absence of a sensory stimulus). Rather than dismissing the misinterpretation of an infestation, altered reasoning may occur (which may have a genetic and/or neurological basis), which leads the patient to believe there is a true infestation. Functional MRI in DI patients indicates that there may be abnormailities in the cortical and mid-brain areas associated with the interpretation of perceptions [3]. The involvement of the dopaminergic mid-brain structures and the therapeutic efficacy of antipsychotic D2-dopamine antagonists may indicate dopaminergic dysfunction in DI. For patients with DI secondary to organic disease, there is often a reason why brain function may be compromised (Table 86.1).

Predisposing factors

There may be a genetic predisposition for patients with primary and DI secondary to psychiatric disease. Patients with DI may be more likely to be socially isolated.

Pathology

Skin biopsy is best avoided except to exclude other cutaneous differential diagnoses. Histology (if it is taken) shows cutaneous excoriations or external trauma at various stages of the healing process.

Clinical features

History

The diagnosis of DI is usually not difficult and is initially considered following the history alone. Patients present with a belief that they are infested by an organism or animate material. They will often describe itching, biting, burning or crawling sensations on the skin that may be localized or generalized. These sensations may be intermittent or, more often, persistent and disabling. Patients often make great effort to prove the infestation (see section on the ’specimen sign’) [4].

Presentation

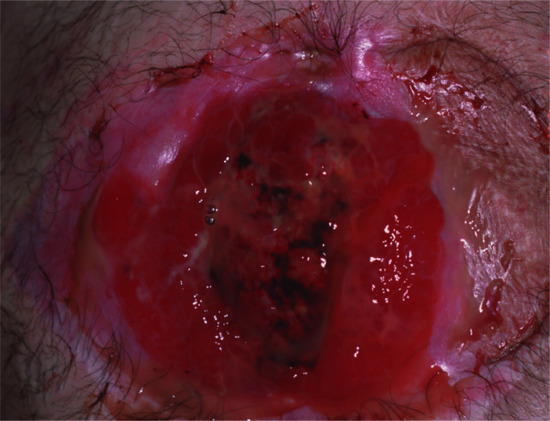

It is crucial that HCPs carefully examine the skin of patients with suspected DI for several reasons [2]. Firstly, it is important to check for a genuine infestation. Secondly, it is important to exclude differential diagnoses of DI and to look for clinical evidence of secondary causes of DI. It is essential for the patient to experience the clinician checking for an infestation, thereby confirming that his/her symptoms are being addressed. On examination, patients often have localized or generalized excoriations, erosions and sometimes ulceration. These skin changes are produced in an attempt to extricate the organism, usually with the fingernails, but occasionally nail files, scissors, needles, penknives, tweezers and nail clippers. Some patients go to much greater lengths to eradicate the perceived infestation by using surgical implements, handicraft knives and chemical corrosives (Figure 86.2). These can inflict significant damage. Occasionally there are no physical signs at all, but the patient will still maintain that the infestation is present and the itching/biting/stinging sensations are there.

Figure 86.2 Patient with delusional infestation. The marks on the legs are where the patient applied elastic bands to stop the ’worms’ from travelling up his leg beneath the skin.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include:

- A genuine infestation.

- Causes of generalized pruritus (see Chapter 0).

- Immunobullous disease (usually this is easily distinguished from DI by the clinical picture).

- Organic disease that leads to secondary DI.

Complications and co-morbidities

Coexistent affective disease (anxiety, depression or both) is common in patients with DI. Assessing psychosocial co-morbidities is important. There is a considerable (but not fully charted) risk of suicide in patients with DI. Bacterial superinfection of excoriations and irritant dermatitis (e.g. from the patient's own use of cleansing agents) are common. Some patients create severe ulcers and extensive erosions from attempts to eradicate perceived organisms.

Disease course and prognosis

The crucial step in managing patients with DI is engagement of the patient [5, 6]. As with all psychodermatology disease, HCPs should treat the skin and the psychological disease concurrently (the ’golden rules’). Psychodermatology specialist centres are probably the best places to treat patients with DI, and most psychodermatologists will try to commence a treatment plan on the first appointment. Treatment is usually continued for several months until the delusion has settled. Patients at this stage will tell clinicians that the infesting organisms have ’gone’. Treatment of substance abuse and co-morbid affective disease may be necessary. Treatment may be slowly withdrawn a few months after the delusion has disappeared [6, 7], but recurrence of DI symptoms may occur in up to 33% of patients (especially those who have not managed to control recreational drug and alcohol abuse). Reported adherence to medication is good once engagement of the patient is established [6], but this may be in specialist centres with extensive experience of managing patients with DI. The prognosis in these centres is favourable, with up to 75% of patients responding to treatment. Suicide is always a risk in patients with DI, and clinicians must be aware of local services to which suicidal patients can be referred urgently [8].

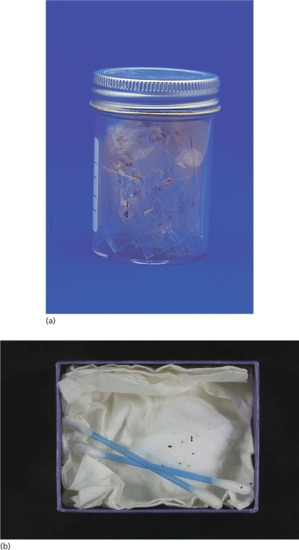

Investigations and the ’specimen sign’

Patients with DI will usually be keen to prove their infestation. Many will bring along specimens of the organisms that they believe are infesting them (Figure 86.3). This used to be called the ’matchbox sign’, but more recently clinicians have recognized that patients may have access to sophisticated equipment and may bring along hi-tech audio or computer images of material they have themselves analysed. This has been termed the ’specimen sign’ [4]. It is imperative that these specimens are taken seriously and carefully reviewed by clinicians. Skin debris and specimen material may be analysed for human pathogens by microscopy in the local microbiology laboratory. A catalogue of normal results will assist the patient in understanding that the clinician understands the patient's experience and continues to seek and exclude a genuine infestation. Patients may repeatedly canvas clinicians to take skin biopsies to prove the infestation, and be unsatisfied with biopsies that fail to show a genuine infestation. Otherwise, investigations may be led by the clinical picture. A pruritus screen is undertaken routinely in some centres, but investigations that are informed by the clinical picture are usually acceptable. Assessment of coexistent affective disease and suicidality is imperative and careful assessment of recreational drug and alcohol usage is important.

Figure 86.3 (a) Container brought in by a patient with delusional parasitosis. (b) ’Specimen sign’ for delusional infestation.

Management

Engagement of the patient is crucial in the management of DI [9]. HCPs must develop a sympathetic, understanding approach to the patient. It is usually futile to try to dissuade patients of the validity of their infestation. Instead it is better to let the patient know that you understand the difficulties that they are experiencing, and that you have successfully looked after patients with a similar disease. The enormity of patient experience is often halfway to engaging the patient with appropriate treatments.

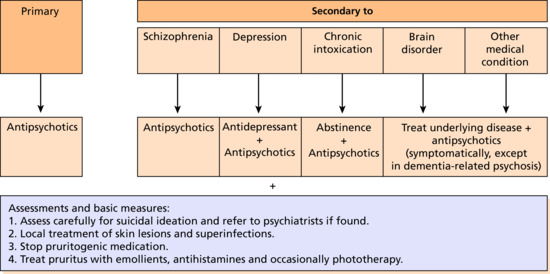

Research in DI is difficult and very few randomized controlled clinical trials exist. Evidence tends to come from case series and is eminence based rather than evidence based. The choice of antipsychotic medication is often based on patient age, co-morbidities and lifestyle rather than any direct comparison of efficacy. Most psychodermatologists now avoid pimozide due to its cardiotoxic risks. Instead, most recommend atypical antipsychotics as the first line of treatment, together with treatment of the skin and any co-morbid affective disease (Figure 86.4).

Figure 86.4 Management algorithm for delusional infestation. (From Lepping et al. 2014 [9].

Reproduced with permission of Wiley.)

Many patients will accept medication to help their distress even though it is not directed at the eradication of the ’parasites’. If broached in terms of using a medication that ’has helped others before’ and ’getting started to help in some way’ or ’to help with the sensations in the skin’, psychotropic medication may be commenced in the dermatology clinic by experienced physicians [10]. Management is ideally effected with close liaison between dermatology and psychiatry. It is mandatory to refer to a psychiatrist immediately if there is any indication of risk of suicide. Adherence to medication is actually very good once the patient is engaged with medication, as is the prognosis.

First line

There is only one (fairly poor) randomized controlled clinical trial of pimozide versus placebo. However, atypical antipsychotics are probably more effective and have a better side effect profile than conventional antipsychotics [6]. The antipsychotic rispiridone is both a dopamine blocker and a serotonin antagonist and has proved of further use in doses of 1–8 mg per day [7]. Olanzapine has a higher affinity as a serotonin blocker than a dopamine antagonist and can be effective in surprisingly small doses.

Resources

Patient resources

- Mind: www.mind.org.uk.

- Samaritans: www.samaritans.org.

- Skin Support: www.skinsupport.org.uk.

- (All last accessed August 2015.)

Olfactory delusions

Introduction and general description

Olfactory reference syndrome (ORS) is one of several unique primary psychiatric disorders that present to dermatologists. Published descriptions of ORS date back to the late 19th century and cases have been reported across the globe. The term ORS was coined by Pryse-Phillips [1] who described the condition as follows: ’The association of an “intrinsic” smell hallucination and a “contrite” reaction in the absence of a history of preceding depression’ (though anxiety and depression may be a consequence of ORS). ORS is probably a spectrum of different disease presentations and there remains some discussion about its classification. Patients may present with a true delusional and hallucinatory illness, but some may present as part of a body dysmorphic disease or obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).

Characteristically, the smell in ORS is described as being emitted from the patient – that is intrinsic as opposed to extrinsic (commonly described by patients with temporal lope epilepsy or schizophrenia). The term ’contrite reaction’ has been described in more recent literature as a ’preoccupation with body odour’ where patients may become sensitive to ideas of reference (e.g. people holding/scratching noses or opening windows), excessively wash themselves and change clothing, become socially withdrawn and in some cases suffer mild depression [2]. Hallucinations of various types occur as part of many disease processes, in ORS, however, the hallucination is olfactory only. It is accepted that persistent preoccupation with body odour may be seen in certain psychiatric illnesses or may be associated with organic brain injury and such disorders must therefore be excluded when diagnosing ORS [3, 4].

Much dispute has surrounded the classification of ORS [5]. This is largely due to the presence of the primary symptoms in other conditions. Most regard ORS as a delusional disorder. Since the behaviours that describe the contrite reaction are commonly seen in obsessed patients, the question has arisen as to whether or not ORS is in fact a variant of OCD. Much of the published literature is in the form of case reports, which makes this investigation more difficult; however, particular patterns have emerged and young males without any concurrent psychiatric disorder have been identified as the most frequent presenters.

Epidemiology

This is a rare condition, which is more common in young male adults (male : female 4.5 : 1), and occurs in all ethnic groups. Associated diseases include:

- Depression.

- Obsessive–compulsive disorders.

- Body dysmorphic disease.

- Dementia.

- Temporal lobe epilspsy.

Pathophysiology

Olfactory reference syndrome is poorly researched and the pathophysiology is not understood [6]. There are some clues, though, from case reports. Some patients with ORS present at the onset of dementia, and some cases are precipitated by dopaminergic medication for Parkinson disease. There are some patients who present with ORS as part of other psychiatric diseases.

Clinical features

Patients will usually present with a long history of experiencing an unpleasant smell from a specific part or from all over their body [7]. The smell is almost always unpleasant and may be faecal, putrific, sweaty, metallic or acrid. Patients will usually go to great lengths to cleanse themselves of the smell and will reject any suggestion that the smell is not experienced by other people. Some patients have organic brain disease. Some patients will also have features of body dysmorphic disease, OCD or both.

Box 86.5 lists the proposed criteria for diagnosing ORS [8].

Differential diagnosis

There are a number of possible differential diagnoses:

- A genuine body odour.

- Trimethylaminuria (fish odour syndrome): the patient has a genetic amino acid metabolic syndrome caused by abnormalities of the production/function of the ezyme flavin containing mono-oxygenase 3, which leads to the build up of trimethylamine (TMA) in body fluids. The ability to smell TMA objectively is genetic and variable. Urine analysis for TMA (usually compared to TMA oxide) is helpful to establish the diagnosis.

- Temporal lobe epilepsy (olfactory hallucinations are common).

- Other organic brain disease: dementia, Parkinson disease, brain tumour.

Investigations

Urinalysis should be used to exclude trimethylaminuria. Clinical examination and then appropriate neurological investigations should be performed as indicated.

Management [7–9]

Management is informed by case reports and case series only. Treatment of underlying body dysmorphic disease or OCD is the prime objective for some patients; treatment of any causative neurological disease is a similar priority.

Morgellons syndrome

In 2001, a biologist whose 2-year-old child developed sores on the skin discovered that the multicoloured fibres coming from her child's lesions were undiagnosable by the many physicians she consulted. The Morgellons were described by Sir Thomas Browne in 1674 in a population from Languedoc [1], one of whose characteristics was the development of a hairy back. Nevertheless this name was coined to entitle a syndrome, set up a research foundation, raise funds and generate vast media and Internet interest.

The phenomenon comprises:

- Sensations of crawling, stinging and biting under the skin.

- Sores that do not heal.

- Fibre-like filaments, granules and crystals that appear on or under the skin lesions (Figure 86.5).

- Joint and muscle pain and fibromyalgia.

- Debilitating fatigue.

- Cognitive dysfunction, poor concentration and memory.

Figure 86.5 Sample of the fibres that a patient with Morgellons disease brought to clinic.

Many dermatologists point to the commonalities between this constellation of symptoms and patients with DI [2]. Even so, an examination of Internet websites shows that patients who live with Morgellons are very sure that this is not the case and that ’Morgellons’ disease, as yet unrecognized, really does exist. The Morgellons Foundation has suggested that Lyme disease is to blame as well as agricultural filamentous yeasts, but the US Center for Disease Control has set up an independent study to evaluate the phenomenon, and has concluded that there is no objective evidence for ’unexplained dermopathy’ [3–5]. Treatment responses to pimozide and risperidone have been recorded, together with treatment of the skin with topical antiseptics, systemic antibiotics and (sometimes) phototherapy.

Resources

Patient resources

- Morgellons UK: www.morgellonsuk.org.uk.

- Skin Support: www.skinsupport.org.uk.

- (Both last accessed August 2015.)

OBSESSIVE AND COMPULSIVE BEHAVIOUR

Introduction and general description

Studies of obsessive–compulsive behaviour in dermatology outpatients estimate that OCD is present in up to 25% of patients, but this may include some with body dysmorphic disorder [1, 2]. However, excluding this group there were still up to 15% who have other obsessive–compulsive behaviours such as [1, 2]:

- Body dysmorphic disorder.

- Lichen simplex chronicus.

- Nodular prurigo.

- Skin picking disorder.

- Acne excoriee.

- Trichotillosis.

- Onychotillomania and onychophagia.

- Health anxieties.

General principles of treatment

- An empathetic, supportive approach from HCPs is essential.

- Try to find out why the patient has the ’habit’.

- Never attempt the tell the patient that it is ’all in their head’ or that they ’need to snap out of it’.

- Psychotherapy can produce significant improvement. CBT alone has improved some patients, although the management of underlying personality difficulties may require the specific skills of a psychotherapist.

- Habit-reversal programmes may be useful. These can be accessed online or via self-help material.

- SSRIs can be helpful. Usually patients need be encouraged to start treatment with explanations that the benefit will only start to be realized after 4–6 weeks. Higher doses may be necessary but maximal recommended doses must not be exceeded. Clomipramine and doxepin have been reported to work as well.

- The A-B-C model of habit disorders – Affect regulation, Behavioural regulation and Cognitive control – makes use of all modalities to help patients conceptualize and manage skin picking behaviours.

- Treatment is always based on appropriate treatment of the skin together with treatment of the associated psychological disease.

- Complex disease is best managed by a psychodermatology MDT.

- Second and third line treatments should be initiated by a psychodermatology MDT or through appropriate specialists.

Body dysmorphic disorder

Introduction and general description

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is characterized by a preoccupation with a real or an imagined defect in physical appearance, or if there is a slight physical anomaly, concern is out of proportion to the anomaly. There is a spectrum from patients with overvalued ideas to those whose beliefs are held with delusional conviction. The defect that the patient experiences may seem trivial to objective assessors, but for the patient it is a major focus of their consciousness [1, 2].

Body dysmorphic disorder is surprisingly common, occurring in 1–2% of the general population [3]. It is more common in patients seeking aesthetic and cosmetic surgery [4]. There is a high degree of co-morbidity with mood disorders, OCD and social phobia. This is a difficult group of patients to treat; one of the main obstacles being that most patients lack insight and will not accept psychiatric treatment or referral. Patients may have ideas of reference (believing that their ’defect’ has been noticed by others and believing that other people's behaviour has been modified after witnessing the ’defect’). BDD is very disabling for the patient, and for those around them, since the focus on their perceived defect seems illogical but is also unshakeable. Co-morbid affective disease is common, as is suicidal ideation (up to 25% of patients will act on their suicidal ideation) [1]. Patients are therefore best seen in a joint psychodermatology clinic where possible. There are screening tools for HCPs to identify patients with BDD (especially for those patients seeking cosmetic surgery as the surgery may not address the primary BDD pathology).

Epidemiology

Gender

The female to male ratio is approximately 2 : 1 but this is likely to be evolving (male aesthetic concerns are approaching those of women).

Age

Body dysmorphic disorder often starts in adolescence but may affect any age group. It is often linked to low self-esteem (hence the preponderance of adolescent patients). Younger patients may have a better prognosis, in that relative dissatisfaction with appearance may be a relatively normal experience in this age group and may be self-limiting. HCPs need to be more worried when patients have severe symptoms, such as social avoidance and co-morbid mood disturbances (see Boxes 86.6 and 86.7).

Ethnicity

This disorder occurs in all ethnic groups.

Associated diseases

The following co-morbidities may be seen:

- Chronic skin picking.

- Depression may occur in 60% with a lifetime rate of up to 80%.

- Social phobia, that is fear of a negative impact (37%).

- Substance abuse (40%).

- Deliberate self-harm.

- Avoidant personality disorder.

- Anorexia nervosa patients very frequently have a degree of BDD.

- Suicide.

Pathophysiology [1,3,5]

Theories suggest that sufferers from BDD have self-defeating thoughts, cognitive distortions and destructive beliefs about themselves and their appearance. The development of selective processing of emotional information about body image, physical appearance and interpersonal contact may be related to anxiety disorders and social phobia. BDD patients exhibit more perfectionist thinking and maladaptive attractiveness beliefs, and it is assumed that these are aetiological rather than symptomatic. It has been suggested that childhood abusive experiences may result in body dissatisfaction, bodily shame, low self-esteem and body image distortion. Neurobiological theories relate BDD to acquired brain abnormalities and parietal lobe function. Neurochemical and psychopharmacological evidence suggests that abnormal serotonin metabolism also contributes to BDD. By contrast, social and cultural influences are assuming an increasing importance in personal bodily appearance due to the perceived concepts of beauty, and the quest for perfection, currently prominent in media-driven societies. These pressures shape the attitudes of both women and men. Women have traditionally been driven to view and treat themselves as objects whilst men are pushed towards an often unattainable body image, the Adonis complex of muscular perfection.

Clinical features

Patients with BDD may present with symptoms according to their gender. Women may present with a focus on the skin of the face, breasts, nose and stomach, whereas men may present with concerns about hair (usually thinning), nose, ears, genitals and body build. Facial symptoms are common, but patients with BDD may perceive ’defects’ affecting any part of the body. Concerns about hair (too much, too little or hair in the ’wrong’ place) are common. Some authors indicate that when patients find defects affecting the genital and (in women) breast area, HCPs may need to ask about sexual abuse. Patient's focus on their perceived defect is notoriously tenacious.

Patients will often behave in the following ways:

- Socialize poorly.

- Have a difficult relationship with mirrors (having to ’brace themselves’ to look in a mirror or avoiding mirrors completely).

- Pick at their skin.

- Hide their ’defect’.

- Have very persistent and intrusive thoughts about their perceived ’defect’.

- Repeatedly seek help from different HCPs (’doctor shoppers’).

- Repeatedly attend for cosmetic or aesthetic surgery.

Uncommonly, the delusional type of BDD gives rise to familial BDD where a parent imposes a delusional idea upon a child who in turn develops BDD or, even more rarely, the patient believes that their child has a bodily defect – BDD by proxy.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with BDD [6, 7] is variable, but good, when treated by dedicated BDD teams.

Investigations

Body dysmorphic disorder is a clinical diagnosis, but objective assessments of severity and screening tools do exist.

- Assess for potential suicide risk and refer where necessary.

- Assess for any underlying abuse (physical and mental abuse in a vulnerable adult/child).

- Assess for underlying psychiatric disease (depression, anxiety or both).

- Acknowledge genuine skin disease (e.g. hair loss or skin pigmentation changes).

- Investigate skin changes appropriately (this may mean no investigations at all or may mean appropriately investigating a differential diagnosis).

- Ask about substance abuse.

- Investigate any underlying psychiatric disease appropriately.

There are a number of scales (Box 86.6) and screening questions (Box 86.7) for the assessment of BDD.

Management

These treatments are in addition to the general approach to management outlined at the beginning of this section.

First line

Treatment of the skin

As always patients with psychodermatological disease need to have their skin and their psychological disease treated concurrently. Appropriate treatment of the patient's skin will facilitate engagement of the patient – but it is appropriate treatment rather than inappropriate surgery, which may not satisfy the patient's expectations. From the outset it is important to treat the psychological disease whilst addressing the perceived skin disease. Often there are some skin changes (however minimal) and acknowledging these changes rather than dismissing them will facilitate patient engagement.

Education for patients and their friends and family

There are excellent patient support books and organizations (see Resources).

Psychopharmacological treatments

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CBT are the treatments of choice. Fluoxetine [8], fluvoxamine and citalopram are the best-studied SSRI agents, but recent evidence suggests that all SSRIs are probably effective. Higher dosing regimens than those used for depression are usually required. Patients should receive a trial of 12–16 weeks before efficacy is assessed [9]. If one agent fails another should be substituted, as some patients idiosyncratically respond more favourably to one agent over another. Interestingly, SSRIs appear to be more effective than antipsychotic agents, despite the fact that BDD may sometimes be a delusional disorder. Only about 20% of delusional BDD patients will become free of their delusional thinking with SSRIs however. But, in delusional patients with BDD, the intrusiveness of the thoughts and distress will diminish sufficiently, such that many patients will be able to resume some social and vocational functioning. CBT may be used in conjunction with SSRIs or independently of SSRIs [10].

Talk therapies

There are various CBT techniques that can be used in the management of BDD [10, 11], although there are no trials comparing the different CBT techniques in a randomized, controlled clinical setting. Supportive psychotherapy can be helpful in patients with overvalued ideas and who are not truly deluded, but it is very time consuming and emotionally demanding. Patients with BDD are often poor communicators and difficulty with interpersonal relationships may be one of the central, crucial and earliest features of this disorder. The physician undertaking supportive psychotherapy has to be patient and realize that further skilled directive intervention will eventually be needed from psychiatrists or clinical psychologists. BDD patients are often poor attendees at clinics, but the consultation may in some cases be the only opportunity that a patient has to talk to another human being, which is a reflection of the isolated life these patients often lead. The dermatologist's essential role is to recognize the problem and sympathetically steer the patient on the correct path to help. Narrative therapy addresses the sociocultural causes that may establish beliefs, in this case about the body. The change process in narrative therapy involves helping patients replace these influences by more preferred stories about their problems and lives. Single case studies have been encouraging.

CBT has been shown to be effective in the management of patients with BDD, but trials are often open labelled or uncontrolled. There are a few randomized controlled clinical trials that clearly demonstrate the benefit of CBT, though the numbers of patients in these trials is small.

Second line

Antipsychotics

The evidence that antipsychotics are beneficial for patients with BDD (even those with delusional BDD) is sporadic and based on case studies only. It is very difficult to run controlled clinical trials with antipsychotics in patients with BDD. Although the evidence is not robust, there are some patients who will need to be treated with (usually newer atypical) antipsychotics such as risperidone, aripiprazole and others. These medications need to be initiated and monitored by specialists with extensive experience of their usage.

Resources

Patient resources

- Mind: www.mind.org.uk.

- OCD-UK: www.ocduk.org.

- Phillips KA. The Broken Mirror: Understanding and Treating Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Skin Support: www.skinsupport.org.uk.

- (All last accessed August 2015.)

Lichen simplex chronicus and nodular prurigo

Introduction and general description

Lichen simplex describes characteristic localized skin thickening in response to repeated rubbing and scratching (see Chapter 83). In some instances a minor initiating event, such as trauma, infection or an insect bite, precipitates episodic insistent scratching and rubbing. Irresistible itching is the major complaint, and scratching the chronic accompaniment. In the majority of patients, however, it is the response to anxiety, OCD or an irresistible, persistent itch [1]. Nodular prurigo is more generalized and complex (see Chapter 83). Many authors believe that nodular prurigo patients fall into two categories: atopic patients (see Chapter 0) and patients who are chronic skin pickers (see below).

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Lichen simplex chronicus and nodular prurigo are both common, occurring in between 1% and 10% of the population depending on the report.

Age

Patients probably represent two populations: an early-onset atopic group with a mean age of 19 years, and a later, non-atopic group with a mean age of 48 years. The earlier onset group consists of both men and women, but the older group is predominantly female.

Sex

These diseases are more common in women.

Ethnicity

All ethnicities are found, although Afro-Caribbean and oriental patients are slightly more commonly affected.

Clinical features

Regular rubbing and pressure on the skin produces characteristic thickened, coarsely grained papules and nodules with hyperpigmentation (Figure 86.6). The classic sites of involvement are within easy reach, particularly on the nape and sides of the neck, elbows, thighs, knees and ankles. These areas may be in varying stages of evolution, from early, small, violaceous papules with surface excoriations to chronic areas that present as hyperkeratotic plaques with pigment changes, described as ’dermatological worry beads’. Affected areas are more often localized, and patches of lichen simplex chronicus affecting the vulval or scrotal skin are very common [2]. Scratching or rubbing is carried out using either the hands, back of nails or knuckles, and sometimes with the use of a convenient instrument such as a hairbrush or pen. The actions may be subconscious but more often patients engage in conscious episodes of scratching, which continue until the pruritus is relieved and is replaced by soreness and pain. The change from itch to pain is quite sudden and this abrupt cessation has been described as ’orgasm cutanée’.

Figure 86.6 (a) A patient with nodular prurigo. (b, c) Close up of noduar prurigo.

Complications and co-morbidities

Most authors have commented on the relationship of emotional tension to bouts of scratching. Patients are usually described as stable but anxious individuals [3], whose reactions to stress are relieved by habitual behaviour such as rubbing. Aggression and hostility related to anxiety caused by emotional disturbance may lead to itching. There is considerable evidence that habitual scratching sets up neurotransmitter changes in the brain that act as temporary ’stress busters’. Habitual scratching is often opportunistic (i.e. when the patient can get to the skin) but may become ’addictive’ and so potentially out of control. The freqency of scratching episodes often increases with perceived stress.

Management

There are a number of treatments in addition to the general approach to management outlined at the beginning of this section [5–8].

Skin picking disorder

Epidemiology

Incidence

This disorder occurs in 2% of dermatology patients, but the majority of these have pathological picking associated with atopic and other cutaneous diseases. Skin picking disease in the absence of cutaneous inflammatory disease is rarer but still common [1].

Age

There are two peaks of occurrence: (i) in adolescence and early adult life [2, 3]; and (ii) in middle-aged women. Any age can be affected, although it is rarer in younger children.

Gender

Females are more commonly affected than males.

Ethnicity

Any ethnicity can be affected.

Clinical features [4]

The lesions differ from other artefactual disorders as those who suffer admit to an urge to pick and gouge at their skin (Figure 86.7). There may be an initial reluctance to own up to the self-damage but patients are usually willing to discuss the picking as a ’response to stress’. Any area may be affected. The average duration of disease before presentation is up to 10 years. Patients spend up to 3 hours per day picking, thinking about picking or resisting the urge to pick. These bouts can be ritualized to a set time and place, often the bathroom, frequently at bedtime. Although these activities are usually executed fully consciously, rarely a fugue or trance state can be apparent. Lesions may be quite deep, extending into the dermis, and are more commonly distributed within reach of the dominant hand. Older lesions show pink or red scars, some of which may be hypertrophic. Chronic lesions may also show atrophic scars, which merge and are eventually seen as linear, coalescent areas. Lesions appear at all stages of development and may number from a few to several hundred. Concealment behaviour, for example make-up and clothing, is present in 65% of chronic cases and active avoidance of social situations found in 40%. Up to a quarter of patients may increase alcohol, tobacco or recreational substance habits to counter the burden of disease.

Figure 86.7 (a,b) Facial picking disorder.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to exclude excoriations caused by generalized pruritus, bullous disorders (such as pemphigus) and linear excoriated lesions, which may be the presenting signs of lichen planus or lupus erythematosus. Rarities such as mucinoses that cause scarring are usually distinguishable entities. Another differential is acne excoriée (see separate section).

Complications and co-morbidities [5]

Pre-existing skin disease (e.g. atopic eczema or acne) is very common, as are psychosocial co-morbidities. There may be precipitating psychological events such as divorce, bereavement, abortion or separation. Depression and/or anxiety are often found. Family members with chronic disease is also a common finding.

Complications may include:

- Cellulitis, bacteraemia and septicaemia.

- Scarring.

- Anxiety, depression and guilt.

- Rarely, self-mutilating amputation of a body structure (e.g. breast).

- Suicidal ideation.

Management [6–9]

Acné excoriée

Introduction and general description

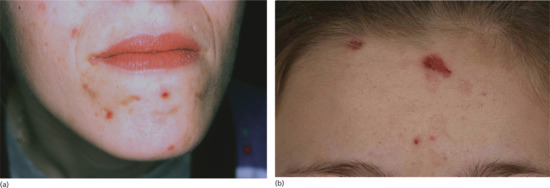

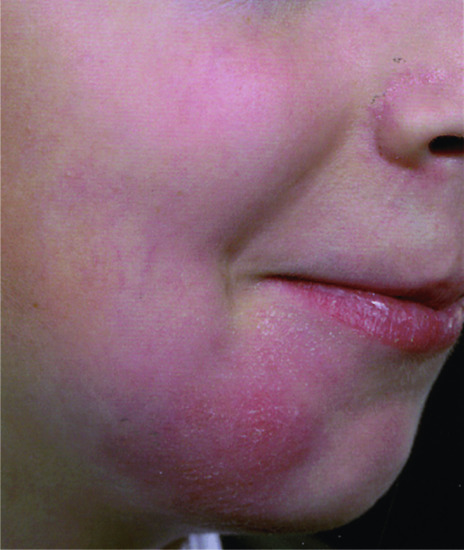

There are few patients with acne who can resist squeezing skin lesions. Brocq described acne excoriée particularly in adolescent girls under emotional stress, who picked and squeezed acne lesions [1]. Although some patients develop these lesions after picking acne, most had no acne at all. The condition should be considered a variant of skin picking disorder with the lesions largely confined to the face (Figures 86.8 and 86.9) [1–3].

Epidemiology

Acne excoriée is usually seen in young (often white) women [3], with a second peak in women in their thirties.

Clinical features [4]

The clinical lesions resemble those of chronic excoriations (Figure 86.8b). They are found predominantly around the hairline, forehead, preauricular cheek and chin areas. Extension to the neck and occipital hairline is common. Chronic lesions characteristically show white, atrophic scarring with peripheral hyperpigmentation. Lesions are picked as a ritual, apparently as a response to itch or throbbing. The lesions are excoriated until ’emptied’. There are usually some acneform lesions, at least when the disease first appears.

Figure 86.8 Acne excoriée. (a) Habitual scarring lesions of the cheek and chin. (b) Lesions on the forehead.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include the facial picking disorder (where there are no acneform lesions originating the picking habit), trigeminal trophic syndrome (see Chapter 84) and dermatitis artefacta.

Figure 86.9 Acne excoriée.

Management [5–8]

Trichotillomania/trichotillosis

Introduction and general description

The term trichotillomania.was first used by Hallopeau in 1889 and is derived from the Greek thrix (hair), tillein (pull out) and mania (madness). Current thinking is that the term trichotillosis is more accurate as the condition is not a ’mania’ but more of an OCD spectrum disorder. Diagnostic criteria that have been cited include:

- Recurrent pulling out of one's own hair resulting in hair loss.

- An increasing sense of tension immediately before pulling out the hair or when attempting to resist the behaviour.

- Pleasure, gratification or relief when pulling out the hair.

- The disturbance is not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

- The disturbance provokes clinically marked distress and/or impairment in occupational, social or other areas of functioning.

Many subdivide patients into younger and older groups and those with dissociative symptoms [1]. Patients with an earlier onset with limited progression usually have a better prognosis. Recalcitrant, obsessive and focused hair pulling is usually found in older women, and patients may deny their hair pulling. Automatic hair pulling is also found, and some patients pull their hair in a dissociative or fugue state.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

This is commoner in children and college students (rates of 0.6–3% have been reported). Overall, later and more severe trichotillosis is not common. Cosmetic hair pulling (eyebrows, etc.) is extremely common, but most do not fulfil diagnostic OCD criteria.

Age

There appear to be two distinct populations: those who present in childhood, mainly between the ages of 5 and 12 years, and more chronic cases who present as adults but who started hair-pulling activities in adolescence or early adult life [2]. The number of affected children may be seven times that of adults and there is evidence of a bimodal distribution with peaks in the preschool years and in adolescence [3]. Preschool children are more likely to be boys (62%), although after this older boys and male adolescents make up only 30% of the group. This early-onset group, usually aged between 2 and 10 years, show benign, self-limiting behaviour and most are probably suffering a habit disorder, perhaps as an extension of hair twirling activity and childhood stress. The adolescent group are much more likely to be female, with ratios of up to 3.5 : 1. In adults there is greater psychopathology and a distinct female preponderance, usually 4 : 1, but this is most evident in the oldest group (F : M 15 : 1).

Ethnicity

Trichotillosis is found in all ethnicities.

Associated diseases

The aetiology of trichotillosis is not fully understood, but seems to be related to the following [4]:

- Underlying anxieties.

- Depression.

- Underlying BDD.

- Psychosocial triggers.

- Family dysfunction (common).

- Other cutaneous ’habits’ such as nail biting and nail pulling.

- Deliberate self-harm ’cutting’, etc.

- Eating disorders.

- Rarely substance abuse.

Familial predisposition is fairly common and successive generations of patients with trichotillosis have been described. It is always worth considering the (rarer) association with emotional or sexual abuse.

Clinical features

Most patients relate that the trichotillosis is a compulsion that is irresistible and that leads to a short-lived sense of relief or release when hair has been pulled out. But the relief usually leads rapidly to a sense of guilt and hopelessness. The habit is often hidden from the partner/close family and the hair loss is usually covered up. Patients may describe a sense of control over their body/psychosocial situation that is briefly facilitated by their hair pulling habits. Some describe pulling hair in a fugue-like state and having no control over the episodes of hair pulling.

Hair pulling and plucking is commonest from the scalp. Some patients select an apparently abnormal hair by feel or texture and extend it into an adjacent area. Most pull hair from the vertex, but temporal, occipital and frontal hair loss in children may be more obvious on the side of manual dominance. The hair loss may be minimal, commonly a solitary patch, but visible hair thinning may progress to virtual total depilation, significantly so in adult women. The hair pulling activity is usually not as a response to any skin symptoms but is either a conscious, deliberate act or more often a subconscious act, almost in some children being part of a hypnogogic (dream-like) state. Some patients may have incomplete awareness until the pattern has been established. The eyelashes, eyebrows, facial and pubic hair may also be primarily affected. Children will also pluck eyebrows and eyelashes (Figure 86.10) but adults almost exclusively pluck hair on the torso. Two-thirds of adults pulled hair from two or more sites and one-third from three areas. Involvement of a second area began after an average of 8 years. Body and pubic hair plucking, commoner in males, may become a ritualized activity done either alone or as a conjugal activity and can indicate a personality or psychotic disorder. Hair is plucked from the scalp on average two to three times per day and daily from other areas. The duration and frequency of activity is variable but adults in general have longer and more frequent activity. Children tend to manipulate hair at times of leisure, for example watching TV, when tired and in the evening. Adults have a more conscious, structured activity, initially seeking thicker or distorted hair and then progressing to larger areas, taking more and more time over the activity. This may become similar to a compulsion with elaboration of the rituals using instruments such as tweezers. The more frequent the plucking episodes, the greater the body image dissatisfaction and the more likely the patient will suffer depression and anxiety. There are similarities and overlap with BDD in some cases.

Figure 86.10 Childhood trichotillomania showing eyelash involvement with hair loss and broken-off hairs. This child also had scalp involvement.

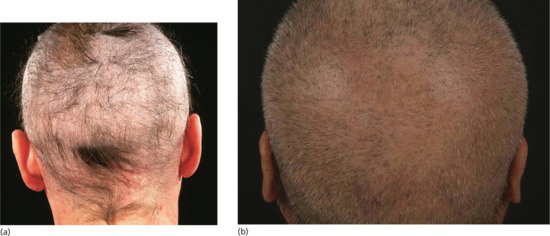

On examination, there are often areas of hair loss together with areas of hair regrowth (stubble and longer hairs) (Figure 86.11). This pattern may involve the eyebrows and eyelashes. There is occasionally frank scarring from where the habit has been repeated incessantly and the follicle has scarred. The patterns of plucking activity are centrifugal from a single starting point or linear, in wave-like activity. In extreme cases, the centrifugal pattern removes all hair except the most difficult to access, namely that on the occiput. This shows as a ’tonsure pattern’ or ’Friar Tuck’ distribution. Patients use wigs, hair weaving, false eyelashes and semipermanent use of hats and scarves to disguise the defects. Chronic folliculitis of the neck, chin, chest, pubic areas or thighs as a result of plucking activity may also be the presenting complaint.

Figure 86.11 Adult trichotillomania. (a) Extensive hair loss with a preserved tuft over the occiput. (b) Patient with hairs at different lengths.

Children may pluck the hair, or stroke or suck the hair root before chewing and swallowing the remainder. The hair root alone may be eaten (trichorhizophagia) as a secretive activity and in a few patients the whole hair is eaten (trichophagia). Patients who eat more hair tend to swallow the longer strands and a very small percentage develop gastrointestinal bezoars.

Complications and co-morbidities

- Scarring hair loss.

- Folliculitis.

- Keloid formation.

- Trichobezoar. This name is derived from the Arabic word badzahr, meaning an antidote or counter-poison (cf the Harry Potter stories). It also relates to the hardened contents of the fourth stomach of the Syrian goat, much prized as a cure for many diseases. Bezoars are ball-like aggregations of vegetable or fibre-like materials in the stomach and small intestine (Figure 86.12). The true incidence of trichobezoar is unknown. It is seen almost exclusively in girls and young women. It is rare but its importance is that morbidity is high with chronicity and severe complications, which can lead to death. Longer hair is more likely to become enmeshed into a ball by the action of peristalsis, and this then becomes too large to leave the stomach via the pylorus. The larger the ball, the more likely it is that gastric atony will develop, leading to symptoms of nausea, indigestion, bloating and pain. The hair ball may eventually completely fill the stomach. Although the condition is very rare, it should be considered in children with trichotillosis who present with a combination of any of the following: abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and foul breath. More common is the parental threat to their children that ’if you keep chewing your hair, eventually you'll have a hair ball in your stomach’.

- The Rapunzel syndrome [5]. This describes a trichobezoar with a tail that extends at least to the jejunum; sufferers are highly likely to have gastrointestinal obstructive symptoms. In a review of 27 cases, which included only one male, the mean age at presentation was 10.8 years. Most patients ingested their own long hair although cases have been recorded of bezoar by proxy where another person's hair has been eaten by the patient. In this group 37% had abdominal pain, 33% nausea and vomiting, 26% obstruction and 18.5% developed peritonitis. The hair ball can have a tail as long as 195 cm. The tail may also be broken up into numerous segments distributed throughout the small bowel. Recurrent Rapunzel syndrome has been reported [5]. Life-threatening intestinal obstruction necessitates surgical intervention.

Figure 86.12 Gastric trichobezoar on barium contrast examination showing a lace-like pattern of the mass of hairs.

Investigations

The diagnosis is usually clinical [6]. Scalp biopsy is rarely necessary unless clinicians need to distinguish trichotillosis from scarring alopecia. Trichomalacia is seen as deep distortion and curling of the hair bulb. In severe damage there is intraepithelial and perifollicular damage. Trichoscopy/dermoscopy has been reported as being very helpful in the presence of a corroborating history (broken hair shafts, hairs of different lengths, traumatized hair shafts).

Management

These treatments are in addition to the general approach to management outlined at the beginning of this section.

Onychotillomania and onychophagia

The compulsive habits of nail picking (onychotillomania) and nail biting (onychophagia) have been shown to be common in children and adolescents [1]. The aetiologies suggested include stress, imitation of family members and transference from the thumb sucking habit. Nail biting is usually confined to the fingernails, but nail picking, especially in adults, may involve all digits. Damage to cuticles and nails causes paronychia, nail dystrophy and longitudinal nail scarring [2]. In chronic cases, there is an association with trichotillosis. Compulsive biting, tearing or picking with instruments such as scissors, knives or razorblades may lead to permanent destruction.

Onychotillomania may be a feature of developmental problems in children and is a component of self-destructive behaviours in the Tourette and Prader–Willi syndromes. In adults, chronic nail biting is most commonly an isolated, self-destructive habit, which may respond to cognitive behavioural training [3]. It is also common as a compulsive action as a part of OCD, not always at times of stress. Rarely, onychotillomania is a manifestation of a major depressive disorder that has a suicide risk. Self-induced anonychia of the toenails was produced by one man who plucked out his nails with pliers rather than suffer recurrent paronychia from previously crushed toes.

Health anxieties

Introduction and general description

Health anxieties are irrational fears that are out of proportion with objective reality, and overwhelmingly distort everyday life. They can be regarded as obsessional fears. Dermatology patients may present with focused anxieties about the development of a variety of cutaneous diseases. Predominant cutaneous anxieties (or phobias) can be divided into:

- Anxieties of contamination, e.g. dirt phobia, germ phobia, wart phobia.

- Fear of malignancy, e.g. cancer phobia, mole phobia.

- Others, e.g. blushing, sweating.

- General health anxieties.

Dirt, infection and wart phobias [1]

These are OCDs where the patient has an overwhelming fear of contamination or infection of the skin or body. Hand washing leading to dermatitis is common, but up to 10% will admit to compulsive body washing also. The precipitating factors are fears of dirt and contamination from others who have been infected with real organisms (e.g. meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA) or those who might have been (e.g. those recently discharged from hospital). Situational exposure in work to dirt and waste may initiate the fear. Hand washing may occur up to 100 times per day and compulsive showering and bathing 10–20 times daily. Irritant dermatitis that does not resolve with adequate advice should prompt inquiry, not only about washing compulsions but also checking behaviours.

Mole and cancer phobias [2, 3]

This is an OCD where the patient has an overwhelming fear of developing cancer and may stray into delusional disease. A dislike of moles and freckles may be a manifestation of BDD but for most patients who repeatedly demand mole examinations, and sometimes excision, there is an underlying cancer phobia. It occurs in response to various stimuli. For example, the patient may have had a malignant lesion removed and need constant reassurances. Or there may have been malignancy or death from melanoma in family or friends, or concern repeatedly triggered by media, medical or family pressure. It is an excessive response to disease, often related to anxiety. Patients present regularly and acutely to a screening clinic or primary care physicians. They may demand removal of some or all of their moles or even attempt self-surgery. Mole phobia by proxy is not uncommon in parents who worry about their children and their moles to such an extent that normal play activities and family holidays are curtailed because of concerns about sun exposure. Unless the primary pathology (the OCD/anxiety disorder) is addressed, the condition is likely to continue.

Other anxieties and phobias [4]

Topical corticosteroid phobia occurs, predominantly about skin thinning and to a lesser extent stunting of growth in children.

Management [5]

These treatments are in addition to the general approach to management outlined at the beginning of this section.

EATING DISORDERS

Introduction and general description

Eating disorders are considered primarily as psychiatric illnesses that have significant physical complications. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and a third group called ’eating disorders not classified’ are particularly common among young women and are increasing in incidence.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia

Introduction and general description

For anorexia nervosa to be diagnosed, the following criteria must be found:

- An inability to maintain a normal or minimum weight for age and height coupled with an intense fear of gaining weight; the body mass index (BMI) is less than 17.5 kg/m2.

- A distorted perception of weight, size and body configuration.

- Amenorrhoea.

Bulimia nervosa is defined by the following:

- Recurrent and compulsive overeating episodes (binge eating).

- Recurrent and inappropriate compensatory behaviour in order to avoid gaining weight; these include induced vomiting and abuse of diuretics and laxatives.

- Binge eating and weight reduction behaviours occurring at least twice per week for 3 months.

- Self-esteem affected by weight and body configuration.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Anorexia nervosa now has an incidence of up to 1% and bulimia up to 5% of the general population [1]. Reviews suggest a lifetime prevalence of 2.2%, with over half the cases not detected initially in the health care system. The annual prevalence is about 0.3% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia, although this may be higher in women aged 15–24 years [2]. The incidence is 270 per 100 000 person years in this group of younger women compared to 8 per 100 000 person years in the group of women as a whole.

Age, sex and race

Anorexia occurs earlier in life, usually in adolescence, whilst bulimia has its peak in the later teens and early twenties. The majority of sufferers are young women; the proportion of men being 1 : 20 though there is increasing evidence that this is moving closer to 1 : 5. White races predominate in published studies. The prevalence in Afro-Caribbean and Asian women is rare. It is commoner in industrialized societies and much more frequent in those of high social class.

Clinical features

Cutaneous co-morbidities [3]

There are a number of skin problems commonly found in sufferers of anorexia and bulimia:

- Xerosis and pruritus.

- Russell's sign (knuckle pads from chewing the skin overlying the knuckles) (Figure 86.13).

- Nutritional disease:

- Pellagra.

- Dermatitis enteropathica.

- Anaemia and hair loss secondary to iron deficiency.

- Cutaneous microvasculature:

- Raynaud phenomenon.

- Acrocyanosis and perniosis.

- Hair abnormalities:

- Hypertrichosis.

- Hair loss.

Figure 86.13 Russell's sign: callosities of the knuckles from manual forced vomiting in bulimia.

Psychodermatological co-morbidities

- Self-injurious behaviours [5].

- Trichotillosis.

- Severe onychophagia.

- Fabricated dermatitis.

- Suicide; the risk is much higher than in the normal population [6].

- Substance abuse.

- BDD [7].

Investigations and management

Dermatologists should suspect anorexia nervosa when presented with these suggestive signs, particularly in an underweight girl. A simple screening questionnaire is helpful for detecting eating disorders (Box 86.8). Eating disorders are largely undetected in the community. Patients not resistant to the suggestion of specialist care should be referred to a psychiatrist. Dermatologists may be able to help with advice about treatment of skin manifestations.

PSYCHOGENIC ITCH

Psychogenic pruritus

Introduction and general description

Pruritus is a multifactorial symptom. Dermatological, neurological, iatrogenic illness and internal disease are well-recognized causes [1] (see also Chapter 83). The propensity for individuals to sense itch after psychological provocation by pictures of insects, rashes and watching other subjects scratching demonstrates the ready ability of simple measures to induce psychosomatic pruritus. Misery and colleagues have proposed diagnostic criteria for psychogenic pruritus [2]. There are three compulsory criteria:

- Localized or generalized pruritus sine material.

- Chronic pruritus (>6 weeks).

- Absence of a somatic cause.

Localized or generalized psychogenic itch may begin as a stress response [3]. Patterns of itching and scratching may predominantly occur during periods of relaxation or non-occupied time. Pruritic episodes may be unpredictable in onset and present with abrupt and sudden termination. The quality of itch may be unusual, described as crawling, stinging or burning. Sites of predilection in two-thirds of subjects were the legs, arms and back. Localized itching may lead to generalized body itch within a short time. In some individuals, intense scratching can induce a feeling of pleasure which may be related to the release of opioids centrally.

Patients with psychogenic itch may go on to develop [4, 5]:

- Nodular prurigo.

- Depression (about 30%).

- Anxiety and depression (10% for out-patients and 20% for in-patients).

Management [6–10]

Treatment of psychogenic itch is best seen as concurrent treatment of itch sensations at the same time as treating the underlying or associated psychosocial co-morbidities.

FACTITIOUS SKIN DISEASE

Introduction and general description

Doctors usually believe what the patient tells them. The unwritten contract of the consultation process is that the patient will relate the details of the illness as truthfully as they see it and respond to the physician's questions as openly as possible, neither deliberately hiding nor distorting the facts. The physician makes these assumptions in assessing the combination of signs and symptoms of the illness. Some patients may exaggerate or minimize symptoms. Patients may misattribute causation on the basis of experience, culture and a need to place the illness in a context. They may have mistaken beliefs because of advice from other medical or, increasingly, media- or Internet-inspired sources. These consultation behaviours are common and do not constitute a fabrication, although if persistent this conduct can alienate a clinician's objectivity.

Clinical deception refers to a spectrum of illness that lies in a continuum depending on the level of intention to deceive at the time of the act, and the motivation for the induced illness. The definition of factitious behaviour is not completely clear since the level of intention may vary, but for the dermatologist the definition by DSM-5 includes:

- A Falsification of physical or psychological signs and symptoms, or induction of injury or disese, associated with identified deception.

- The individual presents himself or herself to others as ill, impaired or injured.

- The deceptive behaviour is evident even in the absence of obvious external rewards.

- The behaviour is not better explained by another mental disorder such as a delusional disorder or another psychotic disorder.