CHAPTER 87

Acquired Disorders of Epidermal Keratinization

Anthony C. Chu1 and Fernanda Teixeira2

1Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, UK

2Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, UK

Acquired ichthyosis

Definition and nomenclature

Acquired ichthyosis is a condition that arises in adulthood but is clinically and histopathologically similar to hereditary ichthyosis vulgaris. It is rare, and should raise the suspicion of an associated internal disease, particularly malignancy, endocrinopathy, some infections, autoimmunity or a reaction to medication [1].

Introduction and general description

Acquired ichthyosis usually arises in adult life and clinically resembles hereditary ichthyosis. It is not, however, inherited but is associated with a systemic disorder.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Acquired ichthyosis is a rare condition. There are no available data on prevalence.

Age

Acquired ichthyosis occurs mainly in adulthood but acquired ichthyosis in children with systemic disease has been reported [2].

Associated diseases

See Box 87.1

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of acquired ichthyosis is not fully understood; it differs according to the entity with which it is associated.

In cases associated with diabetes, it is supposed that the changes in the skin are due to structural abnormalities in proteins resulting from non-enzymatic glycosylation [23, 24]. However, well-controlled diabetics can also show ichthyotic changes, and for these, an abnormal host immune response has been proposed, probably against components of the granular cell layer [10]. The same hypothesis has also been advanced to explain acquired ichthyosis associated with autoimmune disorders [17], whereas those cases associated with tumours seem to be due to secretion by neoplastic cells of transforming growth factor α (TGF-α), which may exert a mitogenic action on keratinocytes [25].

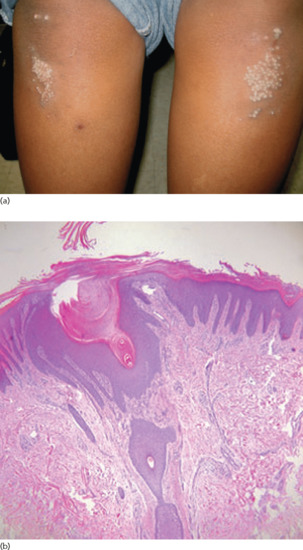

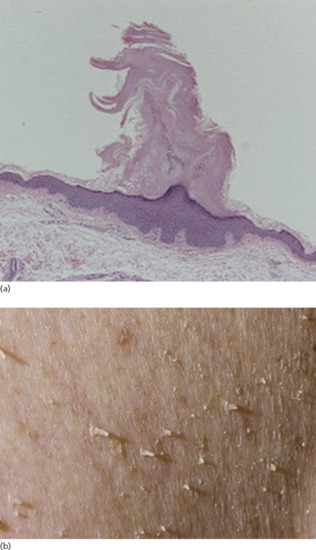

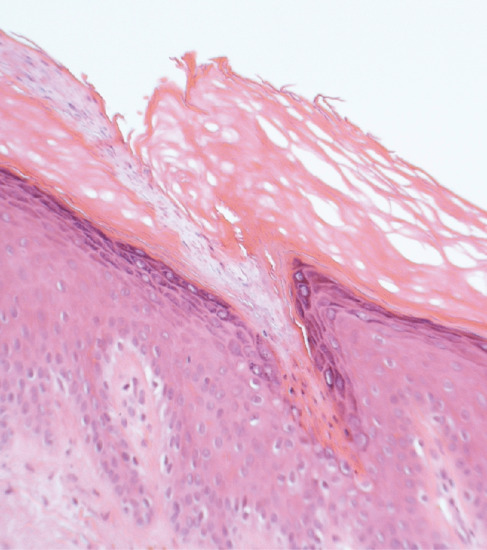

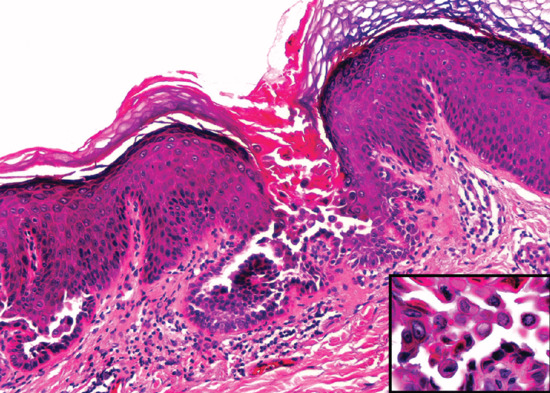

Pathology

Histologically, the epidermis shows compact hyperkeratosis with a thinned or absent granular cell layer.

Environmental factors

Living in a hot and humid climate may hide the clinical manifestations of filaggrin deficiency [26]. Severe xerosis mimicking acquired ichthyosis can be observed in atopic individuals who immigrate from very humid atmospheres such as South-East Asia to Europe. In their home country, xerosis is not evident but the low humidity in Europe may precipitate an ichthyotic change in the skin.

Clinical features

History

The onset of acquired ichthyosis is typically sudden with initial involvement of the lower limbs but it may then generalize.

Presentation

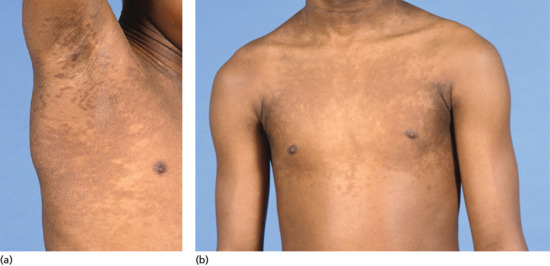

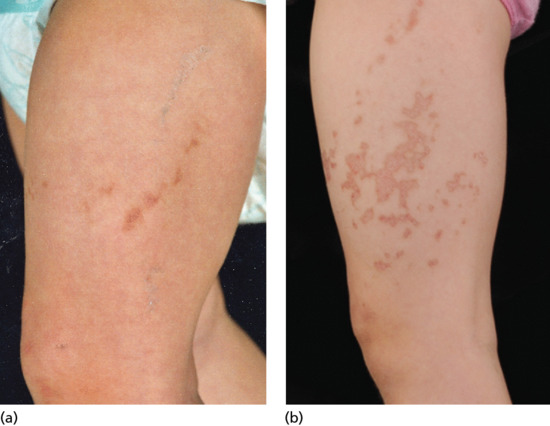

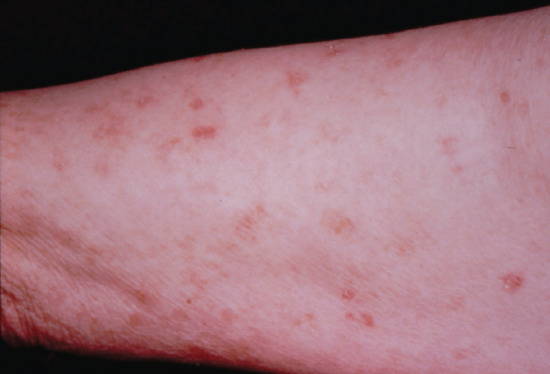

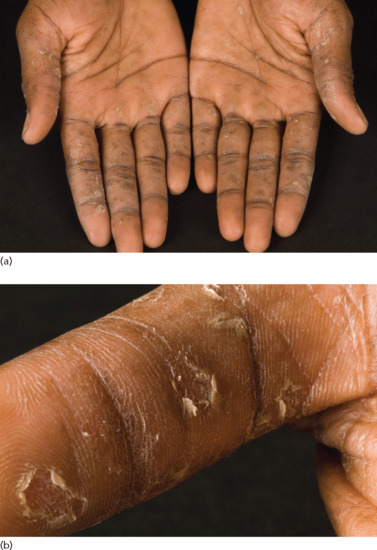

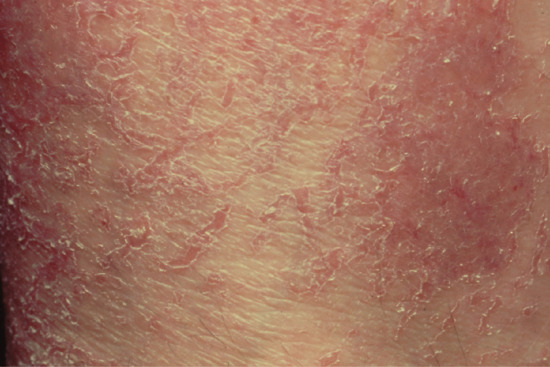

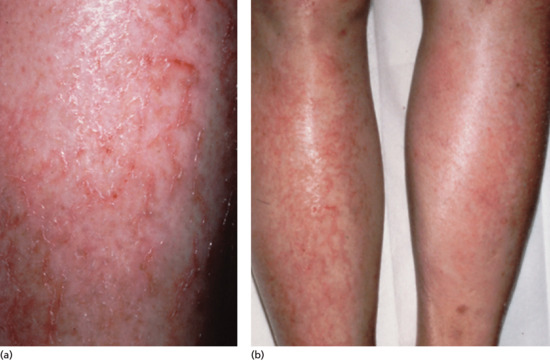

Symmetrical dark thick scaling appears on the legs in a pattern likened to the skin of lizards. The arms and trunk can also be involved, especially the back (Figure 87.1), but flexures are spared, due to the higher humidity in these areas. The face is unaffected in most cases, probably due to the size and number of its sebaceous glands, but the scalp shows abundant fine scales. Pruritus can be pronounced. There may be palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, with fissures that can become infected [1].

Figure 87.1 Acquired ichthyosis secondary to lymphoma.

Differential diagnosis

- Xeroderma.

- Asteatotic eczema.

- Atopic eczema.

- Drug eruptions.

- Hereditary ichthyoses.

Disease course and prognosis

Acquired ichthyosis may improve with successful treatment of the underlying disease or cessation of the responsible drug.

Investigations

The diagnosis of acquired ichthyosis is made clinically and confirmatory tests are unnecessary. Once the diagnosis has been made, a careful search for an underlying cause should be undertaken, with particular care not to overlook the possibility of occult malignancy, especially lymphoma. In addition to a full history, clinical examination, chest radiography and a detailed drug history should be obtained. Appropriate investigations should be performed to identify other potential causes.

Management

The primary aim in the management of acquired ichthyosis is to identify the underlying cause of the disorder. Its treatment can lead to improvement of the dermatosis.

Treatment of the acquired ichthyosis is symptomatic and involves the use of retinoids and keratolytic agents.

First line

Topical retinoids, particularly tretinoin and tazarotene, reduce the cohesiveness of keratinocytes [27].

Second line

Beta-hydroxyacids (salicylic acid) help to disaggregate the corneocytes.

Third line

Alpha-hydroxyacids (lactic or glycolic acids) produce loosening and desquamation of corneocytes, when applied twice daily. Urea 10–20% is an excellent humectant. Propylene glycol as a 20% preparation in aqueous cream hydrates the stratum corneum.