CHAPTER 93

Other Acquired Disorders of the Pilosebaceous Unit

Roderick J. Hay1, Rachael Morris-Jones1 and Gregor B. E. Jemec2

1Dermatology Department, King's College Hospital, UK

2Department of Dermatology, Roskilde Hospital; and Health Sciences Faculty, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Pseudofolliculitis

Definition and nomenclature

Pseudofolliculitis is an inflammatory follicular and perifollicular foreign-body reaction.

Introduction and general description

Pseudofolliculitis is an inflammatory follicular and perifollicular foreign-body reaction to hair trapped beneath the skin surface as may occur from penetration or retraction of the cut ends of hair into the skin following shaving or as the result of disturbed hair growth following plucking or waxing. Areas particularly affected are those most frequently shaved including the beard, pubic areas and lower legs.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Pseudofolliculitis of the beard area is very common, with reportedly up to 80% of African males being affected.

Age

After puberty.

Sex

Males are most commonly affected.

Ethnicity

Men of African descent are particularly predisposed.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Inflammation results either from the hair being cut too short, so that it may retract into the follicle and then directly penetrate the follicle wall, or from hair left to grow for a few days after being cut or shaved, such that the hairs curve backwards and penetrate adjacent skin [1, 2]. Curly hair is more liable to both of these aberrations, so that the condition is very common and more severe in those with tightly coiled hair [2]. Genetic predisposition is an important factor [3].

Skin folds or irregularities due to scarring may allow ingrowth of straight hairs. Any shaved surface in either sex may be affected, but the male beard area is naturally the most common. Both plucking [4] and waxing [5] of hair, particularly on the limbs in women, commonly lead to pseudofolliculitis. Cut nasal hairs may act similarly [6]. Pseudofolliculitis is particularly troublesome in the Armed Forces, where strict grooming standards demand clean shaving [2]. The exact prevalence is not known, although between 45% and 83% of African American men are thought to be affected [2]. Pseudofolliculitis has also been reported as an adverse drug reaction to oral minoxidil [7].

Pathology

Penetration of aberrant cut ends of the hair into the follicle or surrounding tissue results in acute inflammation, microabscesses and foreign-body giant cell granuloma formation.

Causative organisms

Coagulase-negative staphylococci may sometimes be grown from the lesions but the condition is not primarily infective but rather a foreign-body inflammatory reaction.

Clinical features

Presentation

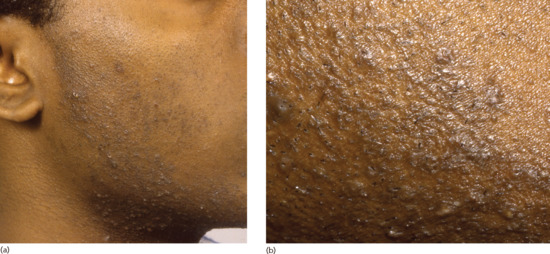

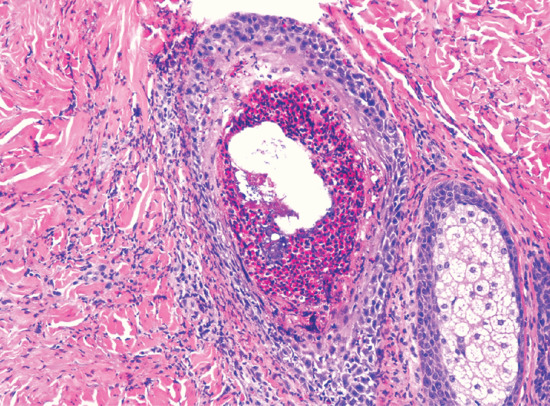

The condition typically manifests as multiple small papules and pustules on shaven skin, particularly in the beard area. The skin of the neck and over the jaw is most commonly affected, although the cheeks may also be involved (Figure 93.1a,b). Papules may be large and may scar; keloid formation and hyperpigmentation may ensue. It is generally possible to identify some penetrating hairs but they may not be visible in all cases. Where there is clinical doubt, it is sometimes possible to extract a coiled hair using the tip of a sterile needle. The clinical appearance may lead to significant distress. The diagnosis is usually obvious. In cases where sites other than the beard area are affected, a history of shaving, plucking or waxing should help to clinch the diagnosis.

Figure 93.1 (a,b) Pseudofolliculitis barbae showing typical distribution (a) and close-up view (b).

Differential diagnosis

Bacterial folliculitis including sycosis barbae and dermatophytosis.

Complications and co-morbidities

Pseudofolliculitis, particularly of the beard area, can result in hypertrophic or keloid scarring.

Disease course and prognosis

Pseudofolliculitis is a chronic condition with a relapsing and remitting course. Avoiding shaving can allow the skin to recover, otherwise intermittent treatment may be required. Permanent hair removal at high-risk sites may be appropriate in selected cases.

Management

The only certain cure is to stop shaving/waxing for a minimum of 4–6 weeks, to allow the inflammation to settle and allow the hairs to grow sufficiently long that ingrowth will not occur. Resumption of shaving or waxing will often, however, lead to relapse [2]. Studies examining the frequency of shaving have demonstrated that shaving 2–3 times per week rather than daily reduced papule and ingrowing hair numbers [7]. Lifting out re-entrant hairs with a needle is helpful but tedious: brushing with an abrasive sponge or toothbrush to ‘release’ the hair is less effective but quicker. Hair should be left about 1 mm long. This may be achieved by adjustment of individual shaving technique, or by specially designed razors [8] or electric clippers. Plucking should be avoided. Some relief is possible with topical steroid–antimicrobial combinations combined with intensive use of emollients. Hair removal with chemical depilatories or topical eflornithine hydrochloride cream may be helpful for some patients, and there is evidence that the combination of eflornithine and laser is better than laser epilation alone [9].

Folliculitis keloidalis

Definition and nomenclature

Folliculitis keloidalis is a chronic inflammatory process involving principally the hair follicles of the nape of the neck and leading to hypertrophic scarring in papules and plaques.

Introduction and general description

Although this relatively common chronic follicular inflammatory dermatosis characteristically involves the nape of the neck (Latin: nucha), it may extend into the scalp; for this reason, the term folliculitis keloidalis is preferred to folliculitis keloidalis nuchae; in order to avoid confusion with keloid formation in association with acne vulgaris, the term folliculitis keloidalis is preferred to acne keloidalis.

Epidemiology

Age

Folliculitis keloidalis occurs in males after puberty and is most frequent between the ages of 14 and 25 years.

Sex

Males are most commonly affected.

Ethnicity

Most common in individuals of African descent.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

This chronic inflammatory condition mainly occurs in black males. A study from Nigeria reported that 9.4% of all patients attending a dermatology out-patient department had folliculitis keloidalis [1]. Many patients have or have had significant acne, and a patient with previous hidradenitis has been reported [2]. No specific organism has been firmly implicated in the aetiology but Staphylococcus aureus may commonly be isolated from swabs from affected skin [3]. Although friction from the collar is often incriminated, the evidence is unconvincing [3]. An association between frequent haircuts (at <2 week intervals) has been documented in older boys attending high school [4]. This finding and the observation of foreign-body granulomas surrounding fragments of hair has led to the suggestion that the process begins with penetration of cut hair into the skin as in pseudofolliculitis. However, no evidence of this was found on a detailed histological examination [5]. Associated keloids in other sites seem not to have been reported, and the process is regarded more as hypertrophic scarring than as true keloid formation.

Pathology

The most frequent histological findings include chronic perifollicular inflammation, disappearance of sebaceous glands, destroyed follicles, lamellar fibroplasia and acute inflammation around degenerating follicular components. Serial sections may show a foreign-body reaction to hair and follicular remnants. The pathological findings seen in early lesions, perilesional skin and clinically normal skin suggest that antigens from follicular organisms such as Demodex, bacteria or other skin flora stimulate an inflammatory reaction which then destroys the sebaceous glands and follicles with resultant scarring [5].

Causative organisms

Staphylococcus aureus may be isolated from skin swabs but it is uncertain whether this organism can be implicated as a primary pathogen.

Clinical features

Presentation

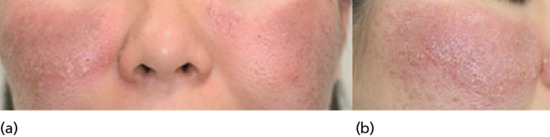

Follicular papules or pustules, often in irregularly linear groups, develop on the nape of the neck just below and within the hair line (Figure 93.2). Less often, they extend upwards into the scalp. The early inflammatory stage may be inconspicuous, and the patient may be unaware of the condition until hard keloidal papules develop at the sites of follicular inflammation. The papules may remain discrete or may fuse into horizontal bands or irregular plaques. In other cases, the inflammatory changes are persistent and troublesome, with undermined abscesses and discharging sinuses. The condition is extremely chronic and new lesions may continue to form at intervals for years.

Figure 93.2 Folliculitis keloidalis of the nape of the neck. (Courtesy of Dr Ian Coulson, Burnley General Hospital, Burnley, Lancashire, UK.)

Disease course and prognosis

The condition usually becomes chronic with permanent keloidal scarring.

Investigations

Skin swabs can be taken if bacterial infection is suspected.

Management

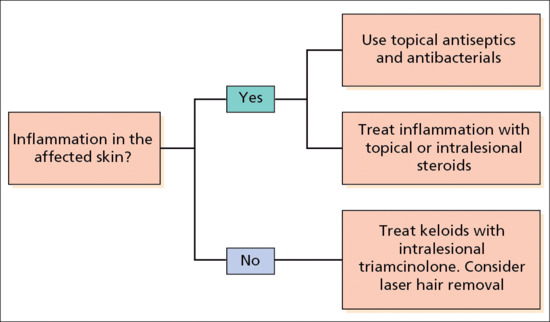

Bacterial infection should be treated if present; antiseptics may reduce further or secondary infection. No evidence-based reviews of therapy options are available. Close shaving of the hair on the nape of the neck and occipital scalp should be avoided. Intralesional or potent topical corticosteroids may reduce scarring and inflammation [5]. Oral corticosteroids prescribed for another condition helped in one severe case but long-term treatment is unlikely to be justified [2]. In general medical treatment is disappointing and, in troublesome cases, the affected area may be excised and grafted or excised and allowed to heal by secondary intention. Laser-assisted hair removal with the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser led to significant improvement after five treatments in 16 patients with acne keloidalis [6]. The laser causes miniaturization of the hair shafts, which is thought to reduce subsequent inflammatory episodes. See Figure 93.3 for an approach to managing the individual patient.

Figure 93.3 Treatment algorithm for folliculitis keloidalis.

Necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis of the scalp margin

Definition and nomenclature

Necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis is a rare and poorly understood chronic scarring follicular dermatosis characterized by necrotizing inflammation of follicles close to the scalp margins and resulting in multiple small round varioliform scars [1]. It has historically been termed acne necrotica varioliformis.

Introduction and general description

This uncommon condition is characterized by a necrotizing folliculitis which appears in crops primarily along the frontal hairline and which is responsive to acne treatment.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is rare.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Early lesions are characterized by a dyskeratotic follicular epithelium with associated spongiosis. A prominent lymphocytic perifollicular and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate is also seen. As the lesions progress, more widespread necrosis appears involving the follicular epithelium, epidermis and dermis, and often containing fragments of hair. Bacteria are often seen in the stratum corneum.

Causative organisms

Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes have both been implicated but their role, if any, is uncertain. Staphylococcus aureus can sometimes be cultured from more advanced lesions.

Environmental factors

Aggravation in summer has been reported [1].

Clinical features

Presentation

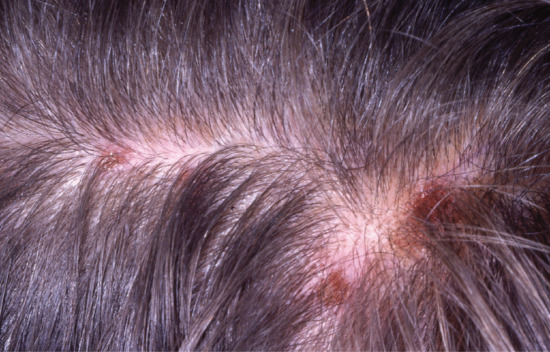

Some patients experience mild pruritus but usually the disease onset is insidious with the appearance of papules in the frontal hairline or, more rarely, the seborrhoeic areas of the skin. Some soreness may be associated with the evolving reddish-brown papules which gradually umbilicate, developing focal areas of necrosis with crusting over the course of weeks, ultimately leaving depressed varioliform scars (Figure 93.4).

Figure 93.4 Varioliform scars at the scalp margin secondary to necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis.

Differential diagnosis and co-morbidities

Emotional disturbance has been described as associated.

Investigations

Careful culturing to establish whether S. aureus is present.

Management

Papulonecrotic tuberculid (see Chapter 27) and tertiary syphilis (see Chapter 29) should be excluded. Other potential differential diagnoses include repetitive excoriation, folliculitis decalvans, eczema herpeticum, pyogenic bacterial folliculitis and molluscum contagiosum [2, 3, 4].

In scalp folliculitis, the lesions are typically distributed throughout the scalp, and are smaller, usually more numerous, non-scarring and more pruritic (see later).

Scalp folliculitis

Definition and nomenclature

A non-scarring chronic superficial folliculitis of the scalp that is typically characterized by multiple minute, very itchy pustules distributed throughout the scalp and which has been attributed to a reaction to the presence of microorganisms, in particular Propionibacterium acnes.

Introduction and general description

Scalp folliculitis is a relatively common chronic relapsing complaint in which multiple minute itchy pustules form in the scalp. Because of the itch, secondary excoriation and crusting is common (Figure 93.5). It has received very little recent attention by researchers. The best description comes from a report by Hersle et al. in which they presented their findings in 40 patients (30 males), whom they re-examined a mean of 8.3 years after they had first presented with scalp folliculitis [1]. Histologically, there was a neutrophilic folliculitis without necrosis; bacteriologically only the usual resident microflora of the scalp were detected, with P. acnes being the most frequently isolated organism. They found P. acnes within the pustules but not on the overlying skin surface of three patients whom they investigated.

Figure 93.5 Scalp folliculitis with secondary excoriation.

Very similar reports had been made previously by Montgomery and by Maibach [2, 3]. Montgomery described a virtually identical clinical picture in 25 patients with up to 100 pustules confined (except in one case) to the scalp. He unfortunately used the term acne miliaris necrotica to describe these patients, even though necrosis is not seen; confusingly, others have used the latter term as an alternative for mild acne necrotica varioliformis (necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis, see earlier), which has a different distribution and results in scarring. For these reasons, these terms are best abandoned. Maibach recognized the entity in 1967 and attributed it to P. acnes (formerly called Corynebacterium acnes), as have other authorities since.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Unknown but relatively common.

Age

Onset in third and fourth decades.

Sex

Male to female ratio 3 : 1.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Neutrophilic folliculitis without necrosis.

Causative organisms

Putative role of P. acnes.

Disease course and prognosis

In all 40 patients reported by Hersle et al., there was still an active, recurring non-scarring folliculitis a mean of 8.3 years after first presentation, although seven had had temporary remissions [1].

Management

There is little information on whether topical preparations such as tar shampoos might be of benefit. Low-dose tetracycline appears to be of some benefit but topical corticosteroids do not help [1].

Actinic folliculitis

Definition and nomenclature

Actinic folliculitis is a rare photodermatosis of unknown aetiology characterized by the development of pruritic monomorphic follicular papules and pustules appearing on photo-exposed sites several hours to days after sunlight exposure.

Introduction and general description

Actinic folliculitis is a rare photodermatosis of unknown aetiology characterized by the development of pruritic monomorphic follicular papules and pustules appearing on the face, neck, arms and/or upper trunk several hours to days after sunlight exposure. It normally resolves within 10–14 days. Cultures for microorganisms are negative. Histologically, there is a superficial neutrophilic folliculitis with an admixture of lymphocytes [1].

Epidemiology

Age

Actinic folliculitis has been described in young to middle-aged adults of both sexes.

Sex

Males and females are equally affected.

Pathophysiology

Environmental factors

Exposure to sunlight.

Clinical features

Presentation

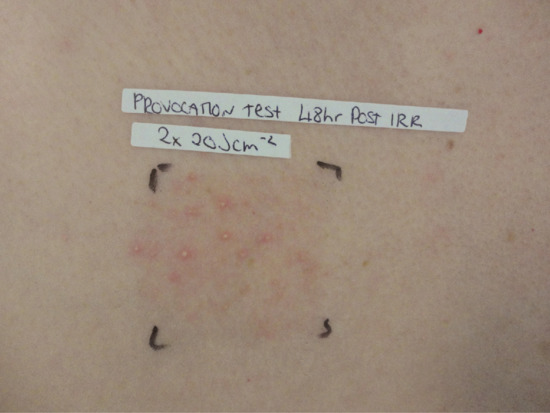

Monomorphic follicular papules and pustules erupt over the face, neck, upper arms, shoulders and/or upper chest following as little a few hours of sun exposure [2]. A recent report describes lesions on the back, upper chest and shoulders occurring annually after the first sun exposure of the year [3], confirmed with provocative phototesting. There may be a burning sensation or pruritus at the onset, resolving within 10 days [4, 5]. Another report describes itchy pustules and papules on the lower face resolving within 4 days [6]. The mechanism is unknown.

Differential diagnosis

Polymorphic light eruption, miliaria, papulopustular rosacea, photoaggravated acne vulgaris.

Disease course and prognosis

It may recur annually over many years and is usually worse at the beginning of the summer.

Investigations

A follicular provocation test can be performed to support the diagnosis (Figure 93.6).

Figure 93.6 Follicular pustules on the anterior chest 48 h after irradiation with broadband UVA in a patient with actinic folliculitis.

Management

Photoprotection with behavioural modification, hats, clothing and high factor sunscreen may be beneficial. Standard acne therapy is ineffective, but severe cases may respond to isotretinoin [2, 6]. UVB phototherapy may provide useful desensitization.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis

Definition

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis is a dermatosis of poorly understood aetiology affecting principally the chest, shoulders and upper arms of young black men. It is characterized by a disseminated low-grade spongiotic dermatitis involving the infundibula of multiple adjacent follicles. It manifests clinically as sheets of small monomorphic pruritic papules [1].

Epidemiology

Age

Begins in childhood or in adult life.

Sex

Mainly males.

Ethnicity

Mainly patients with black skin.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Histologically, inflammatory changes are confined to the infundibular portion of the follicles with spongiosis and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate.

Causative organisms

No infective agent has been identified.

Clinical features

Presentation

A widespread eruption of small monomorphic follicular papules on the trunk and limbs sparing the flexures (Figure 93.7). Itch is often but not always present. Occasionally pustules develop. It tends to be persistent or may relapse periodically.

Figure 93.7 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis.

Management

It is generally poorly responsive to treatment including potent topical corticosteroids [2]. Psoralen photochemotherapy [3] and isotretinoin [4] have each been reported to be helpful in individual case reports.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

Definition

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an uncommon cutaneous reaction pattern characterized by infiltration of the pilosebaceous follicles by large numbers of eosinophils. Three different forms are recognized: classical, immunosuppression-associated and infantile.

Introduction and general description

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an uncommon inflammatory cutaneous reaction pattern of poorly understood aetiology, which is characterized by infiltration of the pilosebaceous follicles by large numbers of eosinophils. The classical adult form, Ofuji disease, is predominantly facial and is reported principally from Japan [1, 2]. Immunosuppression-associated eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is strongly associated with HIV infection and is more often extrafacial [3]. Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, which has also been termed infantile eosinophilic pustulosis, would seem to have little in common with the adult forms and is described separately later.

Epidemiology

Age

Classical and immunosuppression-associated disease typically occur in young adults.

Sex

It is seen five times more frequently in men than in women.

Ethnicity

The majority of classical eosinophilic pustular folliculitis patients have been reported from Japan.

Pathophysiology

The cause of the immune dysregulation in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is not understood. Immaturity or suppression of the immune system appear to be important, although this has not been demonstrated in the classical adult form. A large number of hypotheses including hypersensitivity reactions to Malassezia spp., Demodex spp. or sebaceous gland derived lipids have been proposed [1]. Various chemotactic factors have been detected in the fluid of the pustules, which are sterile, and it has been suggested that they may serve to localize excessive circulating eosinophils [4].

There are several reports of the condition erupting during pregnancy [5–7].

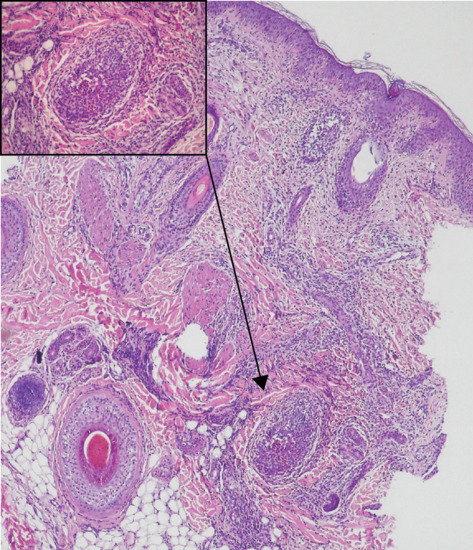

Pathology

The follicular inflammation is characterized by heavy infiltration of the outer root sheath and sebaceous gland by eosinophils accompanied by scattered mononuclear cells and neutrophils (Figure 93.8). This is best detected by serial horizontal sectioning of biopsies of fresh unexcoriated papules or pustules. Perifollicular and perivascular infiltration by eosinophils is also seen. In immunosuppression-associated eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, the inflammation may be more diffuse [3].

Figure 93.8 Histopathology of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis showing dense accumulation of eosinophils within the follicular canal. (Courtesy of Professor Luis Requena, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain.)

Mild to moderate peripheral blood eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients [1, 2, 8] with classical type and in up to 50% with HIV-associated eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, which usually occurs when the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mL [9].

Genetics

There is no known genetic predisposition.

Clinical features

Classical adult eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

This is a chronic relapsing disease in which crops of sterile follicular papules and pustules coalesce into inflammatory annular plaques with peripheral expansion and central clearing. It takes 7–10 days for the inflammation to subside before the cycle repeats itself a few weeks later [3]. The face is the commonest site of involvement (Figure 93.9a,b): in a review of 91 Japanese cases, the face, trunk and extremities were involved in 88%, 40% and 26%, respectively [8]. Pustular inflammation of the palms and soles may be seen in up to a fifth of cases, even though follicles are not present in palmoplantar skin. This may cause diagnostic confusion with palmoplantar pustulosis [10]. The trunk and the upper outer arms are also frequently involved, legs and scalp occasionally. Widespread involvement has occurred [11].

Figure 93.9 (a,b) Classical eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: well-defined, dark erythematous plaques with numerous pustules and crusts involving the cheeks. (Reproduced from Ramdial et al. 1999 [5].)

The inflammatory plaques may reach 3–5 cm in diameter before subsiding to leave slight pigmentation. Lakes of pus and erosions are sometimes seen. Itch is frequent and may be severe but is not invariable. Patients are systemically well. The overall course is chronic with new crops of lesions repeatedly reappearing in affected areas, although a few cases have entered spontaneous remission.

Immunosuppression-associated eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

This has been reported predominantly in association with HIV and AIDS [1, 9, 12, 13] (see Chapter 31). It differs in a number of respects from the classical form. It is not restricted to the Japanese and pruritus is typically much more intense. The pustular element is often not as prominent and clustering into plaques is not a characteristic feature [1]. Facial skin is less commonly involved. The clinical signs may be subtle, sometimes with just scattered follicular papules or excoriations (Figure 93.10), and multiple biopsies may be required to confirm the diagnosis.

Paradoxically, eosinophilic pustular folliculitis may first develop after the CD4 count starts to rise with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), in which case it may be accompanied by the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

Figure 93.10 Immunodeficiency-associated eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in 32-year-old woman with HIV infection: view of anterior chest. (Courtesy of Professor Luis Requena, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain.)

Management

A comprehensive review of the various treatments showed that no treatment is consistently effective, and treatment has to be tailored to the individual patient [12]. Systemic corticosteroids are usually but not always helpful; potent topical corticosteroids are sometimes of some value. Topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus have also been advocated [14].

Dapsone is effective in some cases and may be the drug of first choice [15, 16].

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used in Japan for the classical form: in a review of published Japanese cases nearly 80% were reported to have responded to indometacin [8]. A proposed mechanism of action of oral indometacin is that it interferes with prostaglandin D2 induced chemotaxis by down-regulating expression of CRTH2 (chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule) on the surface of eosinophils [17].

Other reported therapeutic options include minocycline, isotretinoin, itraconazole, cetirizine, metronidazole and colchicine [8]. UVB therapy was helpful in six HIV-associated cases [18], although maintenance treatment was required.

Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

Definition and nomenclature

Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an inflammatory pustular disorder of infants associated with cutaneous and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

Introduction and general description

Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an inflammatory pustular disorder of infants associated with cutaneous and peripheral blood eosinophilia. It was first reported in 1984 by Lucky et al. [1]. It is characterized by recurrent outbreaks of non-infective pustules containing eosinophils on the scalp of infants. In the majority of cases, the condition commences before the age of 6 months and remits by the age of 3 years. In two thirds of cases, body areas other than the scalp are affected. The cause is unknown. It was originally considered and is still generally termed a folliculitis, but in a substantial number of cases no follicular involvement has been found [2, 3].

Epidemiology

Age

Average age at presentation is 6 months [4].

Sex

More common in boys (male to female ratio 4 : 1).

Associated diseases

A case of HIV-associated infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis has been described in an infant [5]. It has also been associated with hyper-IgE syndrome and atopic disease [6].

Pathophysiology

Pathology

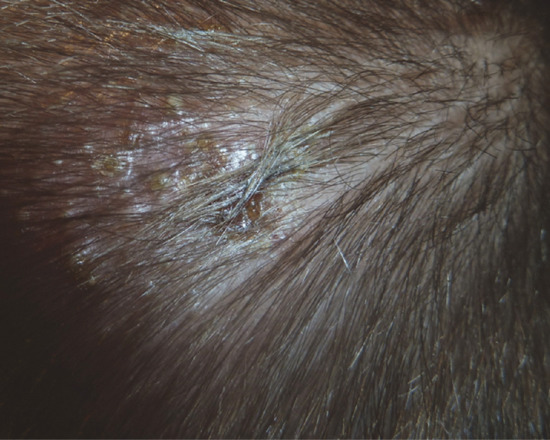

Tzanck smear shows an abundance of eosinophils. Biopsy shows an intense follicular polymorphonuclear and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure 93.11). Hair follicles were identified in only 63% of biopsies in a large case series [2].

Figure 93.11 Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis with dense infiltrate of eosinophils, spongiosis and microabscess formation within the follicle (inset). (Reproduced from Alonso-Castro et al. 2012 [7].)

Causative organisms

Bacteriology is usually negative.

Genetics

It has been reported in brothers [3].

Clinical features

Presentation

It is characterized by recurrent crops of itchy sterile pustules, which recur over several months or years. The sterile pustules develop on the scalp predominantly (Figure 93.12), but lesions may occur at other sites such as the face. Children may develop axillary, inguinal or cervical lymphadenopathy [7]. Pustular lesions resolve spontaneously without scarring [8].

Figure 93.12 Sterile pustules in the scalp of a 23-month-old boy with infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. (Reproduced from Alonso-Castro et al. 2012 [7].)

Disease course and prognosis

This is a self-limiting disease in which spontaneous resolution usually occurs from 3 months to 3 years of age.

Differential diagnosis

Other neonatal and infantile pustular eruptions which should be considered in the differential diagnosis are shown in Table 93.1.

Table 93.1 Differential diagnosis of infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

| Diagnosis | Incidence | Site | Lesions | Onset | Duration | Peripheral eosinophilia | Tzanck smear | Histology |

| Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis | Rare | Scalp, trunk (± hands, feet) | Vesicles, pustules, crusts | Birth or later | Cyclical outbreaks for 3 months to 5 years | During outbreaks in some patients | Eosinophils | Eosinophilic spongiosis; subcorneal pustules; eosinophilic folliculitis |

| Erythema toxicum neonatorum | One-third of neonates | Face, trunk, limbs | Macules, vesicles, pustules | Birth−72 h | Resolves within 1 week | Up to 15% | Eosinophils | Eosinophilic folliculitis; subcorneal eosinophilic pustules |

| Transient neonatal pustular melanosis | 4–5% black infants; 0.1–0.3% of white infants | Neck, trunk, thighs, palms, soles | Vesicles, pustules, pigmented macules | Birth−24 h | Resolves within weeks | May occur | Neutrophils, occasional eosinophils | Neutrophilic intracorneal and subcorneal pustules |

| Infantile acropustulosis | Rare; mainly in black males | Hands, feet (± scalp, face, trunk) | Pruritic papules, vesicles, pustules | Neonatal period or later | Lesions last 7–10 days, crops recur for 2 months to years | May occur | Neutrophils, occasional eosinophils | Subcorneal pustules containing neutrophils; occasional eosinophils |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Rare | Scalp, flexures | Papules, pustules, vesicles, crusts | Birth or later | Varies depending on systemic involvement | No | Histiocytes | Infiltrate of Langerhans cells; Birbeck granules on electron microscopy |

From Buckley et al. 2001 [3] reproduced with permission from Wiley.

Investigations

Tzanck smear, culture for bacteria and fungi, HIV test and IgE levels.

Management

Because the condition is self-limiting, treatment is not usually indicated; however, with particularly recalcitrant or extensive disease dapsone may be helpful [8].

Heterotopic sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots)

Definition and nomenclature

Fordyce spots are heterotopic sebaceous glands (i.e. not associated with hair follicles) which are located on mucosal surfaces or glabrous skin of the lips, oral mucosa or genitalia.

Introduction and general description

These common asymptomatic but readily visible skin and mucosal lesions easily attract the attention of both patients and physicians. Traditionally considered to be ectopic sebaceous glands, they should be considered as within the spectrum of normality.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Fordyce spots on the lips and buccal mucosa are common from an early age and increase in prevalence with age. Fordyce spots were found in 1% of Swedish newborns [1]. The prevalence rises with age: oral or labial lesions were observed in 8% of a large cohort of preschool Brazilian children [2] and in 95% of a large cohort of adult Israeli Jews [3].

Sex

Vulval Fordyce spots are very common in women, with reported rates of 75–95% [4]. Fordyce spots on penile or scrotal skin were incidental findings in 9% of 400 Polish men who sought advice about other genital abnormalities [5].

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Fordyce spots are essentially sebaceous glands in which the duct is connected directly to the overlying epidermal or mucosal surface rather than into a hair follicle. They contain similar lipids to follicle-associated sebaceous glands [6, 7].

Clinical features

Presentation

Fordyce spots manifest as multiple smooth, creamy white to yellow well-demarcated papules which may, however, coalesce into irregular plaques. They are usually 1–2 mm in diameter but may be larger and are slightly to moderately elevated above the skin or mucosal surface. They develop most commonly on the vermilion of the upper lip (Figure 93.13a), the buccal mucosa (Figure 93.13b) or the labia minora (Figure 93.13c). Advice is, however, most likely to be sought by adolescents or young men with prominent penile or scrotal involvement (Figure 93.13d).

Figure 93.13 Fordyce spots on the vermilion of the upper lip (a), buccal mucosa (b), labia minora (c, courtesy of Dr Ekaterina Burova, Bedford Hospital, UK) and penis (d).

Clinical variants

Heterotopic sebaceous glands may be located in the coronal sulcus of the penis to either side of the frenulum and in this location have been referred to as the glands of Tyson [8]. They are normal structures and require no treatment.

Sebaceous glands are found within the tubercles of Montgomery on the areola of the female breast. Typical Fordyce spots on the areolae have, however, been described in a man with coexistent labial and penile lesions [9].

Differential diagnosis

- Leucoplakia.

- Human papillomavirus infection.

- Post-herpetic changes.

Investigations

In cases of doubt, a biopsy will provide the diagnosis.

Resources

Patient resources

http://www.dermnetnz.org/acne/fordyce.html (last accessed August 2015).

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia

Definition

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia presents as scattered clinically obvious flesh-coloured to yellowish papules resulting from hypertrophy of sebaceous glands.

Introduction and general description

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia is characterized by a benign proliferation of sebocytes within normal pilosebaceous units in hair-bearing skin (cf. Fordyce spots). It is most commonly seen in adults but may manifest in the neonatal period due to the passage of maternal androgens across the placenta.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Unknown but not uncommon.

Age

Middle-aged or elderly people.

Associated diseases

Immunosuppression in transplant recipients may predispose to sebaceous hyperplasia [1, 2].

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The whole pilosebaceous unit is enlarged compared with normal adjacent skin but otherwise appears normal [3].

Genetics

Familial cases presenting at a young age suggest the possibility of a genetic component [4].

Clinical features

Presentation

Insidious in onset, sebaceous gland hyperplasia presents as scattered asymptomatic flesh-coloured to yellowish-pink, often umbilicated papules measuring 1–3 mm in diameter (Figure 93.14). Lesions are occasionally confluent, producing a yellowish hue to the skin. They are seen especially on the forehead, temples and cheeks, but may occur on the upper trunk as well. Their main clinical significance is that they may be mistaken for other disorders presenting with facial papules such as basal cell carcinoma.

Disease course and prognosis

Persistent but asymptomatic.

Investigations

In cases of diagnostic doubt, biopsy will rule out neoplasm or other disorder (see Box 93.1 for differential diagnosis).

Figure 93.14 Sebaceous gland hyperplasia on the cheek of a 42-year-old man.

Management

First line

Cosmetic camouflage may be used.

Second line

If requested and appropriate, some physical treatments such as gentle cautery, cryotherapy or trichloroacetic acid can be used. Pulsed dye and 1450 nm diode lasers have also been advocated [5, 6].

Third line

Oral isotretinoin has been reported to be of considerable benefit in extensive sebaceous gland hyperplasia [7]. A therapeutic trial of oral isotretinoin may help to differentiate between sebaceous hyperplasia and multiple early basal cell carcinomas in transplant recipients, and may avoid multiple biopsies if there are many lesions.

Cyproterone actetate in combination with a combined oral contraceptive preparation has also been used with benefit to induce regression of sebaceous hyperplasia in females [8].

Photodynamic therapy using aminolaevulinic acid has also been shown to be useful for shrinking lesions of sebaceous hyperplasia [9].

References

Pseudofolliculitis

- Garcia-Zuazaga J. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Review and update on new treatment modalities. Military Med 2003;168:561–4.

- Alexander AM. Pseudofolliculitis diathesis. Arch Dermatol 1974;109:729–30.

- Dilaimy M. Pseudofolliculitis of the legs. Arch Dermatol 1976;112:507–8.

- Khanna N, Chandramohan K, Khaitan BK, et al. Post waxing folliculitis: a clinicopathological evaluation. Int J Dermatol 2014;53:849–54. .

- White SW, Rodman OG. Pseudofolliculitis vibrissa. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:368–9.

- Liew HM, Morris-Jones R, Diaz-Cano S, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae induced by oral minoxidil. Clin Exp Derm 2012;37(7):800–1.

- Daniel A, Gustafson CJ, Zupkosky, PJ, et al. Shave frequency and regimen variation effects on the management of pseudofolliculitis barbae. J Drugs Dermatol 2013;12(4):410–18.

- Alexander AM. Evaluation of a foil-guarded shaver in the management of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis 1981;27:534–42.

- Xia Y, Cho S, Howard RS, et al. Topical eflornithine hydrochloride improves the effectiveness of standard laser hair removal for treating pseudofolliculitis barbae: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;76(4):694–9.

Folliculitis keloidalis

- Salami T, Omeife H, Samuel S. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in Nigerians. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:482.

- Vasily DB, Breen PC, Miller OF. Acne keloidalis nuchae: report and treatment of a severe case. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1979;5:228–30.

- George AO, Akanji AO, Nduka EU, et al. Clinical, biochemical and morphologic features of acne keloidalis in a black population. Int J Dermatol 1993;32:714–16.

- Khumalo NP, Jessop S, Gumedze J, et al. Hairdressing is associated with scalp disease in African schoolchildren. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:106–10.

- Sperling L, Homoky C, Pratt L, et al. Acne keloidalis is a form of primary scarring alopecia. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:479–84.

- Esmat SM, Abdel RM, Abu OM, et al. The efficacy of laser-assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol 2012;22(5):645–50.

Necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis of the scalp margin

- Kossard S, Collins A, McCrossin I. Necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis: the early lesion of acne necrotica (varioliformis) J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:1007–14.

- Stritzler C, Friedman R, Loveman A. Acne necrotica: relation to acne necrotica miliaris and response to penicillin and other antibiotics. Arch Dermatol Syphil 1951;64:464–9.

- Zirn JR, Scott RA, Hambrick GW. Chronic acneiform eruption with crateriform scars. Acne necrotica (varioliformis) (necrotizing lymphocytic folliculitis). Arch Dermatol 1996;132:1367–70.

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:1–37.

Scalp folliculitis

- Hersle K, Mobacken H, Möller A. Chronic non-scarring folliculitis of the scalp. Acta Dermatovenereol 1979;59:249–53.

- Montgomery H. Acne necrotica miliaris of the scalp. Arch Dermatol Syphilol 1937:36:40.

- Maibach H. Scalp pustules due to Corynebacterium acnes. Arch Dermatol 1967;96(4):453–55.

Actinic folliculitis

- Beukers SM, Van Doorn MBA, van Santen MM, Starink TM. Actinic folliculitis, a rare sunlight-induced dermatosis. Ned Tijdschr Dermatol Venereol 2010;20:122–5.

- Veysey EC, George S. Actinic folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:659–61.

- LaBerge L, Glassman S, Kanigsberg N. Actinic superficial folliculitis in a 29 year old man. J Cut Med Surg 2012;16:191–3.

- Verbov J. Actinic folliculitis. Br J Dermatol 1985;113:630–1.

- Nieboer C. Actinic superficial folliculitis; a new entity? Br J Dermatol 1985;112:603–6.

- Norris PG, Hawk JL. Actinic folliculitis – response to isotretinoin. Clin Exp Dermatol 1989;14:69–71.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol 1979;115:174–5.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J 2008;14(11):11.

- Ravikumar BC, Balachandran C, Shenoi SD, Sabitha L, Ramnarayan K. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:75–6.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. Drugs Dermatol 2004;3:434–5.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

- Nervi SJ, Schwartz RA, Dmochowski M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:285–9.

- Ofuji S. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Dermatologica 1987;174:53–6.

- Lee WJ, Won KH, Won CH et al. Facial and extrafacial eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a clinical and histopathological comparative study. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:1173–6.

- Takematsu H, Tagami H. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Studies on possible chemotactic factors involved in the formation of pustules. Br J Dermatol 1986;114:209–15.

- Mabuchi T, Matsuyama T, Ozawa A. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with pregnancy. J Dermatol 2011;38:1191–3.

- Kus S, Candan I, Ince U, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji's disease) exacerbated with pregnancies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20(10):1347–8.

- Gutierrez HI, Carrillo MJ, Pestana S, et al. Ofuji's disease and pregnancy. A report of a case. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2006;74(3):158–63.

- Katoh M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol 2013;40:15–20.

- Rajendran PM, Dolev JC, Heaphy MR, Maurer T. Eosinophilic folliculitis: before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1227–31.

- Lankerani L, Thompson R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2010;86:190–4.

- Nunzi E, Parodi A, Rebora A. Ofuji's disease: a follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15:107–8.

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2004;5:189–97.

- Soeprono FF, Schinella RA. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;14:1020–2.

- Rho N-K, Kim B-J. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: successful treatment with topical pimecrolimus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;32:108–9.

- Malanin G, Helander I. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji's disease): response to dapsone but not to isotretinoin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20:1121.

- Steffen C. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji's disease) with response to dapsone therapy. Arch Dermatol 1985;121:921–3.

- Satoh T, Shimura C, Miyagishi C, et al. Indomethacin-induced reduction in CRTH2 in Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji's disease): a proposed mechanism of action. Acta Dermatol Venereol 2010;90:18–22.

- Buchness MR, Lim HW, Hatcher VA, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: treatment with ultraviolet B phototherapy. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1183–6.

Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

- Lucky AW, Esterly NB, Heskel N, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol 1984;1:202–6.

- Taïeb A. Infantile eosinophilic pustular “folliculitis” in infancy: a nonfollicular disease. Pediatr Dermatol 1994;11:186.

- Buckley DE, Munn SE, Higgins EM. Neonatal eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001;26:251–5.

- Hernández-Martín Á, Nuño-González A, Colmenero I, Torrelo A. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy: a series of 15 cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:150–5.

- Ramdial PK, Morar N, Dlova NC, Aboobaker J. HIV-associated eosinophilic folliculitis in an infant. Am J Dermatopathol 1999;21:241–6.

- Boone M, Dangoisse C, André J, Sass U, Song M, Ledoux M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in three atopic children with hypersensitivity to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Dermatology 1995;190:164–8.

- Alonso-Castro L, Pérez-García B, González-García C, Jaén-Olasolo P. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in infancy: report of a new case. Dermatol Online J 2012;18:10.

- Taieb A, Bassan-Andrieu L, Maleville J. Eosinophilic pustulosis of the scalp in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:55–60.

- Garcia-Patos V, Pujol RM, Moragas JM. Infantile eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Dermatology 1994;189(2):133–8.

Heterotopic sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots)

- Flinck A, Paludan A, Matsson L, Holm AK, Axelsson I. Oral findings in a group of newborn Swedish children. Int J Paediatr Dent 1994;4:67–73.

- Vieira-Andrade G, Martins-Júnior PA, Corrêa-Faria P, et al. Oral mucosal conditions in preschool children of low socioeconomic status: prevalence and determinant factors. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:675–81.

- Gorsky M, Buchner A, Fundoianu-Dayan D, Cohen C. Fordyce's granules in the oral mucosa of adult Israeli Jews. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986;14:231–2.

- Michajłowski I, Sobjanek M, Michajłowski J, Włodarkiewicz A, Matuszewski M. Normal variants in patients consulted in the dermatology clinic for lesions of the male external genitalia. Cent European J Urol 2012;65:17–20.

- Lynch PJ, Margesson LJ. Skin-colored and red papules and nodules. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph C, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology, 3rd edn. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2008:195–215.

- Monteil RA. Fordyce's spots: disease, heterotopia or adenoma? Histological and ultrastructural study. J Biol Buccale 1981;9:109–28.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Lessin SR, Leyden JJ. Neutral lipid composition of Fordyce's granules. Br J Dermatol 1989;121:669–70.

- Hyman AB, Brownstein MC. Tyson's “glands”: ectopic sebaceous glands and papillomatosis penis. Arch Dermatol 1969;99:31–6.

- Errichetti E, Piccirillo A, Viola L, Ricciuti F, Ricciuti F. Areolar sebaceous hyperplasia associated with oral and genital Fordyce spots. J Dermatol 2013;40(8):670.

- Lee JH, Lee JH, Kwon NH, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of patients with Fordyce's spots. Ann Dermatol 2012;24:103–6.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia

- Salim A, Reece SM, Smith AG, et al. Sebaceous hyperplasia and skin cancer in patients undergoing renal transplant. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:878–81.

- De Berker DAR, Taylor AE, Quinn AG, et al. Sebaceous hyperplasia in organ transplant recipients: shared aspects of hyperplastic and dysplastic processes? J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:696–9.

- Kumar P, Barton SP, Marks R. Tissue measurements in senile sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:397–402.

- Grimalt R, Ferrando J, Mascaro JM. Premature familial sebaceous hyperplasia: successful response to oral isotretinoin in three patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:996–8.

- Ahassi D, Gonzalez E, Anderson RR, et al. Elucidating the pulsed-dye laser treatment of sebaceous hyperplasia in vivo with real-time confocal scanning laser microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:49–53.

- No D, McClaren M, Chotzen V. Sebaceous hyperplasia treated with a 1450 nm diode laser. Dermatolog Surg 2004;30:383–4.

- Gollnick H, Orfanos CE. Front facial picture of a lady with familial nevoid sebaceous hyperplasia before and after treatment with isotretinoin. In: Wilkinson DS, Mascaro JM, Orfanos CE, eds. Clinical Dermatology. The CMD Case Collection. Stuttgart: Schattauer, 1987:350–2.

- Zouboulis CC, Rabe T. [Hormonal antiandrogens in acne treatment.] J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2010 Mar;8 Suppl. 1:S60–74.

- Richey DF. Aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Dermatol Clin 2007;25:59–65.