CHAPTER 95

Acquired Disorders of the Nails and Nail Unit

David A. R. de Berker1, Bertrand Richert2 and Robert Baran3

1Bristol Dermatology Centre, Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol, UK

2Brugmann – St Pierre and Children's University Hospitals, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

3University of Franche-Comté, Nail Disease Centre, Cannes, France

ANATOMY AND BIOLOGY OF THE NAIL UNIT

Structure

Gross anatomy [1, 2–5]

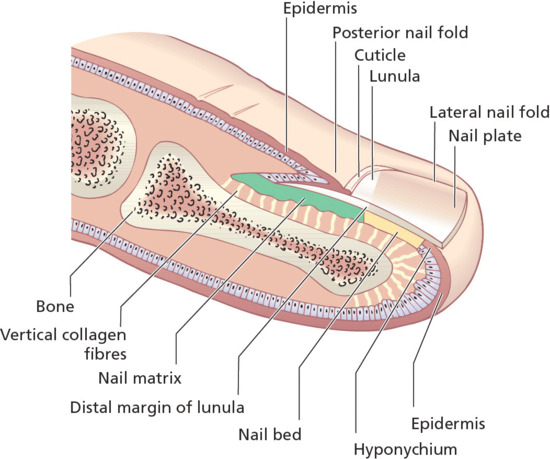

The component parts of the nail apparatus are shown in Figure 95.1. The nail is firmly attached to the nail bed; it is less adherent proximally, apart from the posterolateral corners. Approximately one-quarter of the nail is covered by the proximal nail fold, and a narrow margin of the sides of the nail plate is often occluded by the lateral nail folds. Underlying the proximal part of the nail is the white lunula (half-moon lunule); this area represents the most distal region of the matrix [6]. It is most prominent on the thumb and great toe and may be partly or completely concealed by the proximal nail fold in other digits. The reason for the white colour is not known [7, 8, 9]. The natural shape of the free margin of the nail is the same as the contour of the distal border of the lunula. The nail plate distal to the lunula usually appears pink, due to its translucency, which allows the redness of the vascular nail bed to be seen through it. The proximal nail fold has two epithelial surfaces, dorsal and ventral; at the junction of the two, the cuticle projects distally onto the nail surface. The lateral nail folds are in continuity with the skin on the sides of the digit laterally, and medially they are joined by the nail bed. Some authorities term the lateral nail fold and adjacent tissue lateral to the nail fold the nail wall.

Figure 95.1 Longitudinal section of a digit showing the dorsal nail apparatus.

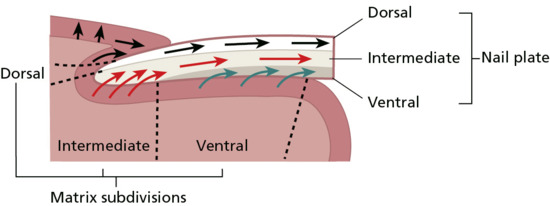

The definition of the nail matrix is controversial [10]. There is common acceptance that there is a localized region beneath the proximal nail which produces the major part of the normal nail plate. For those who consider this the sole source of nail it is termed simply the matrix, or germinal matrix. However, there is some evidence that other epithelial parts of the nail unit also contribute to the nail plate, and these are then also attributed matrix status (Figure 95.2). The matrix can be subdivided into dorsal (the ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold), intermediate (germinal matrix or matrix) and ventral (nail bed) sections. The nail bed is also termed the sterile matrix and its role in the production of the nail is unclear. Although it appears that the nail plate may thicken by up to 30% as it passes from the distal margin of the lunula to the end of the nail bed [3], this is not associated with an increase in cell numbers and may represent compaction of the nail from distal tip trauma rather than nail bed or nail plate production [11]. The situation may change in disease, where the nail bed changes its histological appearance to gain a granular layer [12] and may contribute a false nail of cornified epithelium to the undersurface of the nail [5]. The gap beneath the free edge is known as the hyponychium.

Figure 95.2 Direction of differentiation and cell movement within the nail apparatus.

When the attached nail plate is viewed from above, two distinct areas may be visible: the lunula proximally and the larger distal pink zone. On close examination, two further distal zones can often be identified: the distal yellowish-white margin and immediately proximal to this the onychodermal band [13]. Histologically, it is defined as the most distal attachment of cornified epithelium to the undersurface of the nail and has been termed the nail isthmus [14]. As such, it is structurally significant for the adherence of the nail plate to the nail bed. Once breached, as in conditions such as psoriasis, separation of the nail bed from the nail plate can be progressive.

Microscopic anatomy [15]

Nail folds

The proximal nail folds are similar in structure to the adjacent skin but are normally devoid of dermatoglyphic markings and pilosebaceous glands. There is a normal granular layer. From the distal area of the proximal nail folds, the cuticle adheres to the upper surface of the nail plate; it is composed of modified stratum corneum and serves to protect the structures at the base of the nail, particularly the germinal matrix, from environmental insults such as irritants, allergens and bacterial and fungal pathogens.

Nail matrix (intermediate matrix)

The nail matrix produces the nail plate in the absence of disease (see Figure 95.2). The basal compartment of the matrix is broader than the same region in normal epithelium or in other parts of the nail unit, such as the nail bed [10]. There is no granular layer, and cells differentiate with the expression of trichocyte ‘hard’ keratin (K31–40 and K81–86) as they become incorporated into the nail plate, alongside normal epithelial keratins [15, 16, 17]. During this process, they may retain their nuclei until more distal in the nail plate. These retained nuclei are called pertinax bodies. Apart from this, the detailed cytological changes seen in the matrix epithelium under the electron microscope are essentially the same as in the epidermis [18, 19].

The nail matrix contains melanocytes in the lowest three cell layers and these donate pigment to the keratinocytes. The presence of 6.5 melanocytes per millimetre of matrix basement membrane can be used as a guide to a normal matrix melanocyte population [20]. The appearance of melanocytes separate from the basement membrane distinguishes them from those found in the nail folds, which are primarily basal [21]. Unlike melanocytes in the proximal nail fold and most other sites, nail matrix melanocytes do not express human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A/B/C antigens [21]. Matrix melanocytes are further distinguished from those elsewhere by their failure to produce melanin in normal circumstances in white people. This can change, with melanotic streaks presenting in local inflammatory, naevoid or neoplastic disease. In non-white people, brown streaks are common and are almost universal in Afro-Caribbeans by the age of 60 years.

Langerhans cells are detectable in the matrix by CD1a staining, and the matrix appears to contain basement membrane components indistinguishable from normal skin [22].

Nail bed

The nail bed consists of epidermis with underlying connective tissue closely apposed to the periosteum of the distal phalanx. There is no subcutaneous fat in the nail bed, although scattered dermal fat cells may be visible microscopically.

The nail bed epidermis is usually no more than two or three cells thick, although there may be tongues of epithelium that extend obliquely down. The transitional zone from living keratinocyte to dead ventral nail plate cell is abrupt, occurring in the space of one horizontal cell layer; in this regard it closely resembles the Henle layer of the internal root sheath of the epidermis [23]. Nail bed cells do not have any independent movement, and it is yet to be clearly demonstrated whether they are incorporated into an overlying nail plate as it grows distally [24]. The process of nail bed keratinization has been likened to that seen in rat tail epidermis, possibly being affected by pressure changes. The loss of the overlying nail results in the development of a granular layer, which is otherwise present only in disease states [11, 25, 26].

The nail bed dermal collagen is mainly orientated vertically, being directly attached to the phalangeal periosteum and the epidermal basal lamina. Within the connective tissue network lie blood vessels, lymphatics, a fine network of elastic fibres and scattered fat cells; at the distal margin, eccrine sweat glands have been seen [1].

Nail plate

The nail plate comprises three horizontal layers: a thin dorsal lamina, the thicker intermediate lamina and a ventral layer from the nail bed [4]. This is not always apparent with normal light microscopy using routine stains, where the nail demonstrates a transition between flattened cells dorsally and thicker cells on the ventral aspect. Electron microscopy shows squamous cells with tortuous interlocking plasma membranes [18, 19]. At high magnification, the contents of each cell show a uniform fine granularity similar to the hair cuticle [23]. Nail plate thickness can be measured in health and disease using ultrasound or optical coherence tomography [27].

The nail plate contains significant amounts of phospholipid, mainly in the dorsal and intermediate layers, which contribute to its flexibility. The detectable free fats and long-chain fatty acids may be of extrinsic origin. For further details of these and other histochemical changes in the components of the nail apparatus, see these more detailed texts [8].

Nail biology

Genes influencing the presence or absence or malformation of nails have been sought in connection with inherited abnormalities of the nail unit. The role of these genes in normal nail embryogenesis or production are difficult to determine, but it is clear that when there are mutations in the R-spondin genes and others influencing the Wnt signalling pathway, nail loss or reduction occurs. This first became evident from mutations seen in the R-spondin4 gene in a family with an autosomal recessive pattern of anonychia [28]. More subtle forms of nail dysplasia can be attributed to defects of Frizzled6 which in common with R-spondin4, enhances the Wnt signalling pathway and is found in inherited nail dysplasia [29]. In claw differentiation in knock-out mice, it is associated with expression of keratins K86, K81, K34 and K31; two epithelial keratins, K6a and K6b: all keratins with significance in nail formation and biology. Primary abnormalities in the Wnt signalling itself are also associated with inherited nail dysplasias such as Schöpf–Schulz–Passarge syndrome (Wnt10a) [30]. Mutations in other genes such as LMX1B are associated with multisystem disease such as nail–patella syndrome [31] which may have overlap with elements of Wnt signalling.

Keratin represents 80% of nail mass and its distribution and differentiation is pivotal. One classification of keratins is to divide them into ‘soft’ epithelial keratins or ‘hard’ trichocyte keratins (K31–40 and K81–86). The latter are characteristic of hair and nail differentiation, where their high sulphur content is responsible for their rugged physical qualities. This is matched by the resistance of trichocyte keratins to dissolution in strong solvent.

Keratin distribution in the nail and associated epithelium has been studied in adult [14, 15, 16], infant [17] and embryonic [32] digits. Immunohistochemistry of the epithelial structures of the normal nail demonstrates that the suprabasal keratin pair K1/K10 is found on both aspects of the proximal nail fold and to a lesser degree in the matrix. However, it is absent from the nail bed. This is reversed when there is nail bed disease, such as onychomycosis or psoriasis, where a granular layer develops and K1/K10 becomes expressed at corresponding sites [23]. The nail bed contains keratin synthesized in normal basal layer epithelium, K5/K14, which is also found in nail matrix. An antibody marking the epitope characteristically associated with keratin expressed in the basal layer is found throughout the thickness of the nail bed, but only basally in the matrix [26].

K6/K16 is identified in the nail bed but not the germinal matrix [16]. This is as proliferation is not a prominent feature. The nail bed has very low rates of proliferation [10, 33], and it may be that K6/K16 more precisely illustrates a loss of differentiation, often associated with proliferation in skin but representing the resting state of nail bed epithelium.

The location of K6/K16 is reflected in the localization of the features of pachyonychia congenita. In this group of autosomal dominant disorders, there is thickening of the nail plate attributed to disease of the nail bed in variants of the disease attributed to abnormalities in each of these keratins [34, 35].

Trichocyte keratins 31, 34, 81, 85 and 86 have all been demonstrated immunohistochemically in the nail unit [15, 16]. Proximally, these do not extend onto the ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold, sometimes described as the dorsal matrix and distally their expression is limited to a margin taken as corresponding to the lunula. Their distribution appears to define a matrix consistent with the classic description of the germinal matrix.

Blood supply [1]

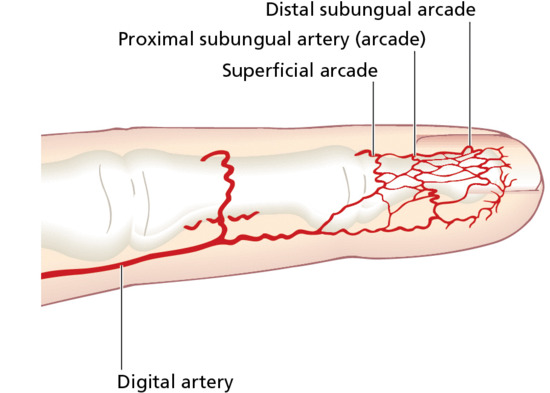

There is a rich arterial blood supply to the nail bed and matrix derived from paired digital arteries, a large palmar and small dorsal digital artery on either side. The palmar arteries are supplied from the large superficial and deep palmar arcades [2]. The main supply passes into the pulp space of the distal phalanx before reaching the dorsum of the digit (Figure 95.3). Distally, the arteries are extremely tortuous and coiled, which allows them to be distorted without kinking to occlude supply. There are two main arterial arches (proximal and distal) supplying the nail bed and matrix, formed from anastomoses of the branches of the digital arteries. In the event of damage to the main supply in the pulp space, such as may occur with infection or scleroderma, there may be sufficient blood from the accessory vessels to permit normal growth of the nail. At a microvascular level, there are three patterns. Within the matrix, vessels are longitudinal with helical twisting. The axis becomes more longitudinal in the nail bed without the tortuosity – a pattern that is also seen in the distal proximal nail fold. This orientation is reflected in the appearance of splinter haemorrhages. In the digit pulp, vessels follow the pattern of the dermatoglyphics [3]. Nail vessel videomicroscopy can be used as part of a dynamic and anatomical modelling process establishing the parameters of blood flow and vessel anatomy [4].

Figure 95.3 Arterial supply of the distal finger.

There are many arteriovenous anastomoses beneath the nail – glomus bodies – which are concerned with heat regulation. Glomus bodies are important in maintaining acral circulation under cold conditions: arterioles constrict with cold but glomus bodies dilate [5]. These occupy the subdermal tissues and increase in number in a gradient towards the distal nail bed [6].

Nail growth and morphology

Clinicians experienced in observing the slow rate of growth of diseased or damaged nails are apt to view the nail apparatus as inert, although it is biochemically and kinetically active throughout life. In this respect, it differs from most hair follicles, which undergo periods of quiescence as part of the follicular cycle.

Cell kinetics

The kinetic activity of the matrix has been examined using many techniques. These include immunohistochemistry, autoradiography and direct measurement of matrix product (i.e. nail plate) by ultrasound [1], micrometer or histology.

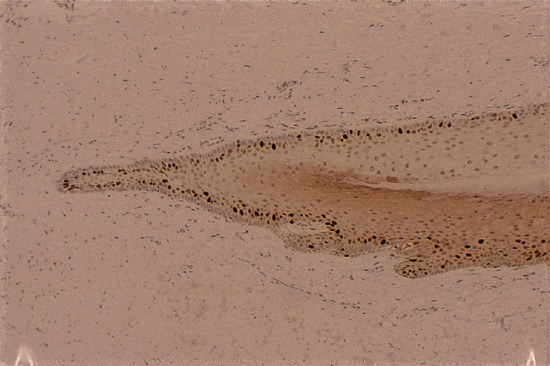

There is a broad basal compartment of proliferating cells in the matrix, which can be detected immunohistochemically with antibodies to proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Ki-67 (Figure 95.4); both antigens are associated with proliferating cells [2]. The matrix is also the site of maximal inclusion of tritiated thymidine if injected into the peritoneum of squirrel monkeys and followed subsequently by autoradiography [3]. Although there was some inclusion of thymidine into the nail bed, Zaias and Alvarez [3] interpreted the findings as indicating that the nail bed had no role in the creation of the nail plate. Norton [4] drew a similar conclusion from work with live human subjects where labelled thymidine and glycine were injected locally to act as markers of proliferating and metabolically active keratinocytes, and both primarily labelled the matrix.

Figure 95.4 Proliferating epithelial cells of the matrix and ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold, staining with the antibody MIB-1.

However, the earlier work of Lewis [5] suggested on histological grounds that the nail plate is a trilaminar structure originating from three separate matrix zones: the dorsal matrix (ventral aspect of proximal nail fold), intermediate matrix (germinal matrix) and ventral matrix (nail bed). In support of this, Johnson et al. [6, 7] demonstrated that 21% of the nail thickness is gained as it passes over the nail bed, implying that the nail bed is generating this fraction of the nail plate. De Berker et al. [2] noted that the increase in nail thickness did not coincide with corresponding increases of nail plate cells. This challenges the interpretation that nail thickens over the nail bed because of a contribution from underlying structures. An alternative explanation may be appropriate, such as compaction arising from repetitive distal trauma. Others have also debated this issue [8] and, although the nail bed may have a significant contribution to make in disease [9], the evidence for its contribution at other times is conflicting.

Nail morphology

Why the nail grows flat, rather than as a heaped-up keratinous mass, has generated much thought and discussion [10, 11–14]. Several factors probably combine to produce a relatively flat nail plate: the orientation of the matrix rete pegs and papillae; adherence to the nail bed; the direction of cell differentiation [15]; and moulding of the direction of nail growth between the proximal nail fold and distal phalanx [16]. Containment laterally within the lateral nail folds assists this orientation, and the adherent nature of the nail bed is likely to be important. In diseases such as psoriasis, the nail bed can lose its adherent properties, exhibiting onycholysis. In addition, there may be subungual hyperkeratosis. These combined factors make psoriasis the most common pathology in which up-growing nails are seen. Onychogryphosis is characterized by upward growth of thickened nail. In this condition, the nail matrix may become bucket-shaped and the effect of the overlying proximal nail fold is lost.

Linear nail growth [17, 18, 19]

During the 20th century, many studies were carried out on the linear growth of the nail plate in health and disease; these have been reviewed [20, 21] and are listed in Tables 95.1 and 95.2 [22]. Most of these studies have been performed by observing the distal movement of a reference mark etched on the nail plate over a fixed period of time; this may well correlate with matrix germinative cell kinetics but there is no direct proof that it does. However, studies on nail growth in psoriasis, and its inhibition by cytostatic drugs [23, 24], suggest that cell kinetics and linear growth rate do have a direct correlation.

Table 95.1 Physiological and environmental factors affecting the rate of nail growth.

| Faster | Slower |

| Daytime | Night |

| Pregnancy [25] | |

| Right-hand nails | Left-hand nails [27] |

| Youth, increasing age | Old age [18, 27, 30] |

| Fingers | Toes [31] |

| Summer [18] | Winter or cold environment [32, 33] |

| Middle, ring and index fingers | Thumb and little finger [28, 31, 34, 35] |

| Male gender | Female gender [27, 35] |

| Minor trauma/nail biting [26, 27] |

Table 95.2 Pathological factors affecting the rate of nail growth.

| Faster | Slower |

| Psoriasis [36] Normal nails [23] Pitting Onycholysis [37] Pityriasis rubra pilaris [21, 38] Etretinate, rarely [39] Idiopathic onycholysis of women [37] Bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma [13] Hyperthyroidism [28] Levodopa [40] Arteriovenous shunts [28] |

Finger immobilization [41] Fever [42] Beau's lines [43] Methotrexate [24], azathioprine [24], etretinate [39] Denervation [44] Poor nutritionKwashiorkor [45] Hypothyroidism [28] Yellow nail syndrome [13] Relapsing polychondritis [46] |

Fingernails grow approximately 1 cm every 3 months and toenails at one-third of this rate.

NAIL SIGNS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE

It is important for clinicians to understand and accurately describe nail findings if they are to communicate effectively with their colleagues. Signs fall into categories of shape, surface and colour.

Nails: abnormalities of shape

Clubbing

In clubbing, there is increased transverse and longitudinal nail curvature with hypertrophy of the soft-tissue components of the digit pulp. The nail can be ‘rocked’ and in causes associated with cardiopulmonary disease there may be local cyanosis.

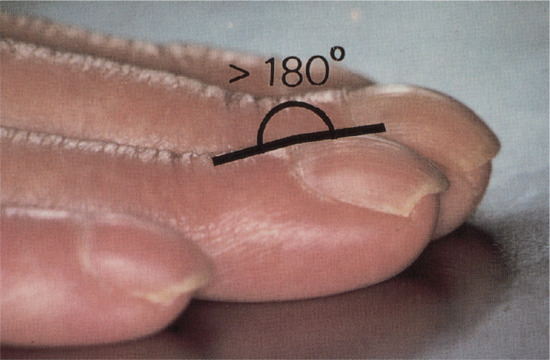

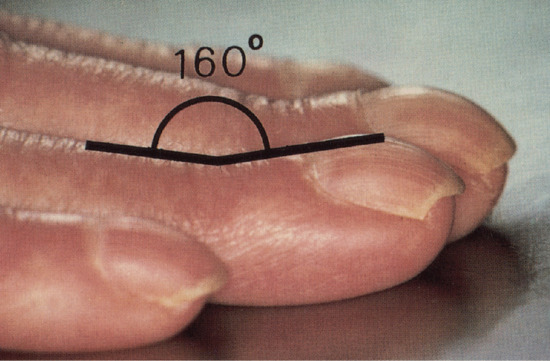

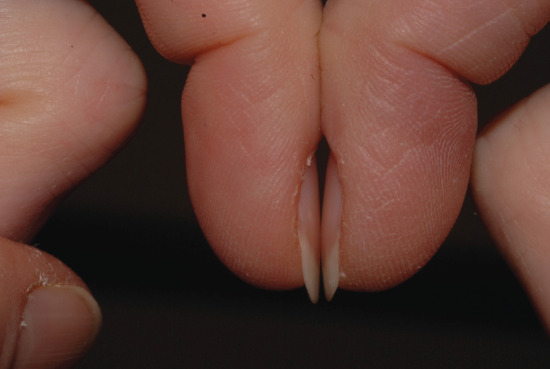

There are three forms of geometric assessment that can be performed. Lovibond's angle is found at the junction between the nail plate and the proximal nail fold, and is normally less than 160°. This is altered to over 180° in clubbing (Figure 95.5). Curth's angle at the distal interphalangeal joint is normally about 180°. This is diminished to less than 160° in clubbing (Figure 95.6). Schamroth's window is seen when the dorsal aspects of two fingers from opposite hands are apposed, revealing a window of light, bordered laterally by the Lovibond angles (Figure 95.7). As this angle is obliterated in clubbing, the window closes [1]. Assessment of clubbing at the bedside shows poor agreement between examiners [2] in milder cases and there are problems in using firm morphometric analyses that do not lend themselves to routine clinical practice [3]. Ultrasound criteria for diagnosis can also be used [4].

Figure 95.5 Clubbing: Lovibond's profile sign. The angle is normally less than 160° but exceeds 180° in clubbing.

Figure 95.6 Clubbing: Curth's modified profile sign.

Figure 95.7 Schamroth's window is seen clearly in this image of normal nails.

Clubbing appears to be related more to increased blood flow through the vasodilated plexus of nail unit vasculature than to vessel hyperplasia, although MRI studies have also implicated hypervascularity [5]. Altered vagal tone and microvascular infarcts have also been implicated [6, 7]. Mutations in the HPGD [8] and SLCO2A1 [9] genes have each been linked to pachydermoperiostosis (primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy), of which clubbing is a component (see below and chapter 154): their gene products are involved in prostaglandin metabolism and prostaglandin transmembrane transport, respectively, suggesting that prostaglandins may be important. Other factors such as bradykinin and serotonin or reactive factors associated with hypoxia could have relevance.

The list of diseases associated with clubbing has a pattern where chronic inflammation of the bowel and lung are seen with or without precipitating infection. Some of these diseases can be clustered, with tuberculosis associated with underlying fibrotic lung disease or HIV, all of which are found to have independent associations [10]. Vascular causes can be associated with central cyanotic ischaemia, as in heart disease, or local factors such as the unilateral soft-tissue changes of hemiplegia [11]. An isolated subungual tumour located within the mid-proximal zone of the subungual space can displace the nail unit upwards in a form similar to clubbing. However, some of the other features are typically lacking, such as the fluctuant quality of the proximal nail and nail fold [12]. This can be included in the category of pseudoclubbing which arises from local pathology such as osteolysis of the tip of the digit seen in systemic sclerosis.

Clubbing is a component of secondary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy as well as of pachydermoperiostosis: in both, a subungual lymphocytic infiltrate may be found and, with this, some associated fibrosis which may ultimately create reactive bone changes and osteoarthropathy. In the primary genetic form, pachydermoperiostosis, there is arthritis and subperiosteal new bone formation affecting the long bones. The secondary form has many of the same benign associations as isolated digital clubbing but is much more strongly associated with malignancy, particularly bronchial carcinoma.

A list of conditions associated with nail clubbing is given in Table 95.3.

Table 95.3 Causes of nail clubbing.

| Cause | Comment |

| Asbestosis | Clubbing is found in about 40% of those with asbestosis |

| Thoracic carcinoma | Includes carcinoma of bronchus, pleura, lymphosarcoma, mediastinal lymphoma and metastatic disease in the lung arising outside the thorax |

| Cystic fibrosis | This is acquired in adolescence or early adulthood. It can be used as a predictive factor for clinical progression of disease |

| Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis | Clubbing is an indicator of disease morbidity |

| Mesothelioma | Clubbing is found in about a third of those with mesothelioma and may in some instances be associated with the asbestosis which is a predisposing factor |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Clubbing can be an association with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in both children and adults |

| Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation | Can be found associated with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia |

| Sarcoidosis | Clubbing can be a local manifestation of sarcoid within the distal digit or a feature of pulmonary involvement |

| Cyanotic heart disease | Typically a patent ductus arteriosus or septal defect |

| Infective endocarditis | Clubbing can reverse when the infection is resolved |

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | Associated with a shunt that gives rise to breathlessness and cyanosis |

| Carcinoma of the oesophagus | Usually associated with the pattern seen with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | May be seen with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy |

| Laxative abuse | It is not clear whether clubbing resolves if laxative abuse stops |

| Liver disease | A range of liver diseases is implicated. When treatment is a liver transplant, the clubbing has been seen to reverse |

| Chronic parasitic infestation | Examples include dysentery caused by Trichuris trichiuria |

| HIV | In one observational study, 37% of HIV patients had clubbing. The mean duration of the HIV was 4 years |

| Tuberculosis | Pulmonary tuberculosis is often associated with other diseases in turn associated with clubbing, such as HIV or coexisting lung disease |

| Thyroid disease | The distinction between thyroid acropachy, pachydermoperiostitis and clubbing is not always clear in reports |

| Lupus erythematosus | A rare association |

| POEMS syndrome | Found in 70% of patients with this rare syndrome of polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy and skin changes (see chapter 148) |

| Hemiplegia | Typically associated with other soft-tissue changes in the hemiplegic hand |

| Subungual tumour | An isolated subungual tumour can create the shape of a clubbed digit, although the rocking of the proximal nail may be absent |

Koilonychia

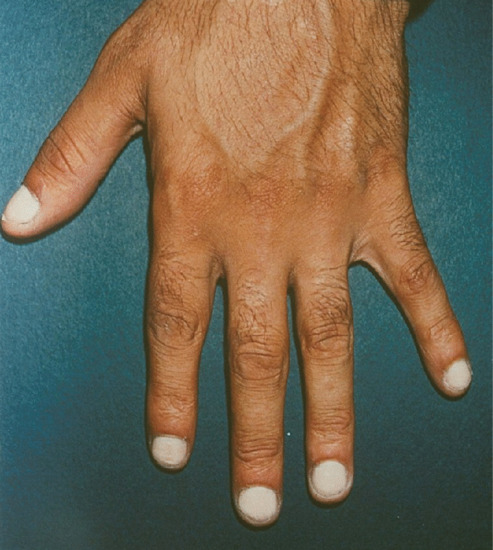

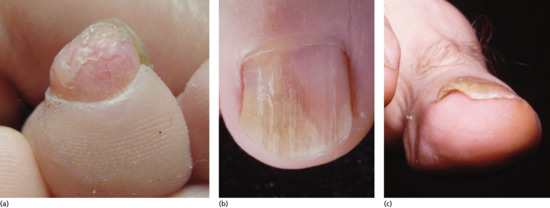

In koilonychia (Greek: koilos, hollow; onyx, nail), there is reverse curvature in the transverse and longitudinal axes giving a concave dorsal aspect to the nail (Figure 95.8) [1]. Fingers and toes may be affected, with signs most prominent in the thumb or great toe.

Figure 95.8 Koilonychia. This image is of congenital koilonychia in a young girl.

Koilonychia is common in infancy as a benign feature of the great toenail, although in some infants its persistence may be associated with a deficiency of cysteine-rich keratin [2] in trichothiodystrophy. The most common systemic association is with iron deficiency [3] and haemochromatosis, although the majority of adults with koilonychia demonstrate a familial pattern, which may be autosomal dominant [4]. In dermatoses such as psoriasis and dermatophyte infection, nail bed hyperkeratosis may push the nail up distally to produce a spoon-shaped nail. In mechanics, softening of the nail from contact with oil may be a factor [5], and in hairdressers, permanent wave solutions may be causal [6].

Pincer nail

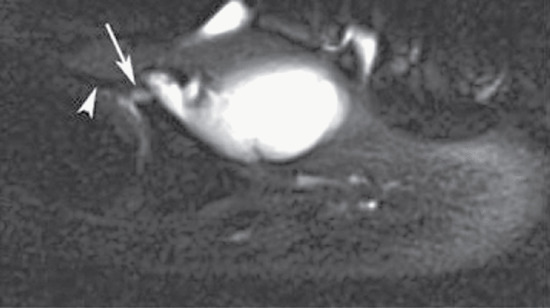

Pincer nail describes a dystrophy where nail growth is pitched towards the midline, combined with increased transverse curvature. It presents in three patterns [1, 2, 3]. Probably the most common is in association with psoriasis, where the thumbs and big toes are the most likely to be affected, although the pattern is not as organized and symmetrical as that seen in the inherited version. In the latter, there is often a gradient of involvement, radiating from the thumbs and big toes outwards, which progresses with time (Figure 95.9). The third variant is the individual nail which develops a pincer deformity. In this instance, careful imaging and surgical exploration should be undertaken to exclude an isolated space-occupying lesion beneath the matrix [4, 5, 6].

Figure 95.9 Pincer nail.

Pain may arise due to embedding of the pincer nail in the lateral nail folds and nail bed, which becomes most pronounced distally. Imaging can be helpful. Treatment is usually by surgery to relieve the pain. In the toes, it is usually best to perform a lateral ablation of the most embedded margin. This will sometimes lead to a shift of the nail such that the other side no longer embeds. If both sides require ablation, the dimensions of the toenail may mean that it is better to ablate the entire matrix rather than to leave a central zone of nail. The alternative of corrective surgery in toes has less chance of success, although successful case series are reported. When treating the thumbs or fingers, the chance of success with corrective surgery is higher and the cosmetic and functional handicap of ablation may not be acceptable. Again, a lateral ablation may be adequate, but more complex procedures entail altering the alignment of the matrix [2, 7, 8], level of the nail bed [9] and addressing any midline hypertrophy of the distal phalanx. Some surgeons advocate a combination of reconstruction and ablation [10]. Nail braces rarely produce long-term benefit, although promising outcomes have been reported [11].

Anonychia

Anonychia is the absence of all or part of one or several nails [1]. It may be congenital, acquired or transient. The underlying genetic abnormality of the congenital form has recently been identified as a mutation in the R-spondin4, Frizzled6 or Wnt10a genes (see above: nail biology), which play a part in Wnt signalling within the cell [2]. There may be a biological interaction with the underlying phalanx in embryogenesis (see Chapter 69) [3].

Acquired forms are due to scarring of the nail matrix. This can arise through burns, surgery or trauma, or be due to inflammatory dermatoses such as lichen planus where the entire nail matrix is scarred and lost [4]. Similar scarring can occur in variants of epidermolysis bullosa, with irreversible nail loss (Figure 95.10). The transient variant is due to nail shedding. This can occur due to an intense physiological or local inflammatory process, in the absence of scarring.

Figure 95.10 Anonychia: nail loss in a 50-year-old man with dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Nails: abnormalities of nail attachment

Nail shedding

Nails can be lost through different mechanisms as follows:

- Complete loss of the nail plate due to proximal nail separation extending distally [1] is called onychomadesis and is a progression of profound Beau's lines. This may reflect local or systemic disease and in the latter may result in temporary loss of all nails.

- Local dermatoses such as the bullous disorders and paronychia may cause nail loss. Generalized dermatoses may be manifest, for example toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and severe/rapid onset of pustular psoriasis. Scarring of the nail unit is seen in lichen planus and following TEN, which may both provoke nail loss.

- Trauma is a common cause of recurrent loss and may reflect the nature of the activity, such as football, or some underlying abnormality of footwear [2] or foot mechanics. It is often associated with subungual haemorrhage [3]. In the long term, athletes often develop thickened dystrophic nails matching a history of recurrent shedding. More severe trauma can result in a degloving event removing all tissue from the end of the phalanx.

- Temporary loss has also been described due to retinoids [4], and to large doses of cloxacillin and cephaloridine during the treatment of two anephric patients [5].

- Onychoptosis defluvium or alopecia unguium describes atraumatic, familial, non-inflammatory nail loss [6]. It may be periodic and associated with dental amelogenesis imperfecta.

- Nail shedding can be part of an inherited structural defect, most obviously in epidermolysis bullosa [7], although at times the diagnosis may be occult [8].

Onycholysis

Onycholysis is the distal and/or lateral separation of the nail from the nail bed [1] and can be graded [2]. Psoriatic onycholysis can be considered the reference point for other forms of onycholysis and is typically distal, with variable lateral involvement. Isolated islands of onycholysis present as ‘oil spots’ or ‘salmon patches’ in the nail bed: at the border of onycholysis, the nail bed is usually reddish-brown, reflecting the underlying psoriatic inflammatory changes. All the common causes are associated with diminished adherence of the nail to the nail bed as a primary (idiopathic) or secondary event: the latter include trauma, fungal infection, eczema, drug reactions and photo-onycholysis [3].

Idiopathic onycholysis

This is a painless separation of the nail from its bed which occurs without apparent cause. Overzealous manicure, frequent wetting and cosmetic ‘solvents’ may be the cause but may not be admitted by the patient. There may, however, be a minor traumatic element, as the condition occurs rather more often in persons who keep their nails abnormally long. Maceration with water may also be a factor [3]. It must be distinguished from other causes of onycholysis (see later). The affected nails grow very quickly [4].

The condition usually starts at the tip of one or more nails and extends to involve the distal third of the nail bed (Figure 95.11). Persistent manicure is attempted to remove the debris which accumulates within the onycholytic space, and this can result in a crescentic margin of onycholysis matching the onychocorneal band and appearing similar in all involved digits. Pain occurs only if there is further extension as a result of trauma or if active infection supervenes. More often there is microbial colonization of a mixed nature, including Candida albicans and several bacteria, of which Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common. If the condition persists for several months, the nail bed becomes dark and irregularly thickened. The condition is mostly seen in women and many cases return to normal after a few months. The longer it lasts, the less likely is the nail to become reattached, due to keratinization of the exposed nail bed.

Figure 95.11 Onycholysis: idiopathic type.

Management [5]

Cut away as much as possible of the loosened nail and apply a topical steroid preparation containing broad spectrum antimicrobials effective against both yeasts and bacteria. Reattachment is slow, and the loosened nail should be recut several times if necessary. Some authorities still recommend 4% thymol in chloroform (not available in the US) as a means of preventing infection and further maceration of the nail bed; however, 2% thymol is often as strong as the patient can tolerate and is usually effective. Where antimicrobial therapy is needed for Pseudomonas, gentamicin eye drops can be useful. Drying under the onycholytic nails with a hair-dryer has been advocated in order to desiccate the environment in which Pseudomonas would otherwise grow. Soaking the fingertips several nights a week in vinegar or sodium hypochlorite solution (Milton) for 5 min can be useful to prevent recurrence. Domestic vinegar is between 3 and 9% acetic (synonym: ethanoic) acid. At the higher strength it can be irritant, especially if the area being treated is already sore. A dilution of 4 parts water to 1 part vinegar is likely to avoid risk of irritancy. Milton is 1% sodium hypochlorite. A 0.25% solution is suitable for wound care, which means a dilution with 4 parts water to 1 part Milton.

Secondary onycholysis

There are many causes of onycholysis [5–8]. Psoriasis, fungal infection, dermatitis and trauma are amongst the most common. Thirty per cent of psoriatics with nail involvement will have onycholysis, with toenail involvement more common than fingernails [9]. Onycholysis occurs in general medical conditions, including impaired peripheral circulation, hypothyroidism [8], hyperthyroidism [9], hyperhidrosis, yellow nail syndrome and shell nail syndrome. Minor trauma is a common cause, and many occupational cases are due to trauma [10]. Immersion of the hands in soap and water may be considered traumatic, as also may the use of certain nail cosmetics. It has also been described after the application of 5% 5-fluorouracil to the fingertips where it can be used therapeutically for warts [11]. There is a condition of hereditary partial onycholysis associated with hard nails [12]. Photo-onycholysis (Figure 95.12) may occur during treatment with psoralens, demethylchlortetracycline and doxycycline [13, 14], and rarely other antibiotics. This is sometimes associated with cutaneous photosensitivity (see Chapter 24). Drugs such as retinoids [15] and cancer chemotherapy can also be implicated, with taxanes eliciting nail changes in between 19 and 44% of patients, depending on the chemotherapy regimen [16]; cooling the hand with a specialized glove has been demonstrated to help diminish or delay onset of these adverse effects [17, 18].

Figure 95.12 Photo-onycholysis with a uniform pattern of discoloured onycholysis in the midline.

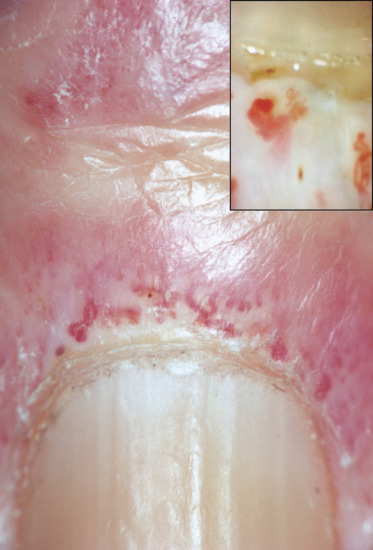

Pterygium [1]

The term pterygium describes the winged appearance achieved when a central fibrotic band divides a nail proximally in two (Figure 95.13). However, the fibrotic tissue may not always grossly alter the nail and can extend from the lateral nail fold as well as the more typical proximal nail fold. A large pterygium may destroy the whole nail.

Figure 95.13 Nail pterygium due to lichen planus.

An inflammatory destructive process precedes pterygium formation. There is fusion between the nail fold and underlying nail bed and matrix. The fibrotic band then obstructs normal nail growth. Superficial abnormal vessels may be seen and there are no skin markings. It most typically develops in trauma or lichen planus and its variants, including idiopathic atrophy of the nail [2] and graft-versus-host disease [3]. It can also occur in leprosy, where it may represent scarring secondary to neuropathic damage and secondary purulent infection [4].

Ventral pterygium

Ventral pterygium (Figure 95.14) or pterygium inversum unguis [1, 2] occurs on the distal undersurface of the nail, with forward extension of the nail bed epithelium dislocating the hyponychium and obscuring the distal groove. Causes include trauma, systemic sclerosis [2, 3], Raynaud phenomenon, lupus erythematosus, familial subungual pterygium [4] and infections [5]. The overlying nail may be normal, but adjacent soft tissues can be painful.

Figure 95.14 Ventral pterygium due to allergy to formaldehyde nail hardener.

Changes in nail surface

Longitudinal grooves

Longitudinal grooves may run all or part of the length of the nail in the longitudinal axis, and need to be distinguished from ridges which are proud of the nail surface [1]. Grooves may be full or partial thickness.

The median canaliform dystrophy of Heller [2] is the most distinctive form (Figure 95.15) [3]. The author has seen it in children under 10, but the literature is potentially misleading due to the confusion between midline transverse ridging of habit tic and true canaliform dystrophy [4]. The nail is split, usually in the midline, with a fir-tree-like appearance of ridges angled backwards. The thumbs are most commonly affected and the involvement may be symmetrical. The cuticle may be normal, as distinct from the cuticle in habit tic deformity (‘washboard nails’). After a period of months or years the nails often return to normal, but relapse may occur [5] and a ridge may replace the original defect. Some patients give a definite history of trauma [1] and rarely the disorder can be attributed to oral retinoids [6]. Although familial cases have been recorded, the majority of cases are sporadic and of unknown cause [7].

Figure 95.15 Median canaliform dystrophy of Heller.

Tumours (e.g. viral warts, myxoid cysts, periungual fibromas) pressing on the matrix, or a proximal nail fold pterygium, may produce a longitudinal groove.

Transverse grooves and Beau's lines [1, 2]

Transverse grooves may be full or partial thickness through the nail. When they are endogenous they have an arcuate margin matching the lunula. If exogenous, such as those due to manicure, the margin may match the proximal nail fold and the grooves may be multiple as in washboard nails associated with a habit tic [3]. When multiple, it may be difficult to distinguish a habit tic from psoriasis. Transverse grooves may occur on isolated diseased digits (trauma, inflammation or neurological events) [4] or may be generalized, reflecting an acute systemic event such as a drug reaction [5], myocardial infarction, measles, mumps or pneumonia. If there is a systemic cause, they are usually referred to as Beau's lines [2]. They arise through temporary interference with nail formation and become visible on the nail surface (Figure 95.16) some weeks after the precipitating event. The distance of the groove from the nail fold is related to the time since the onset of growth disturbance. The depth and width of the groove may be related to the severity and duration of disturbance, respectively. In many cases, grooves are seen on all 20 nails but are most prominent on the thumb and great toenail, and are deeper in the midline of the nail. Full-thickness grooves can be associated with distal extension of the plane of separation of the nail plate. This can lead to nail loss, termed onychomadesis.

Figure 95.16 Beau's lines present as transverse grooves in the nail matching the proximal margin of the nail matrix and lunula.

Nail pitting

Nail pitting presents as punctate erosions in the nail surface. Individual pits may be shallow or deep, with a regular or irregular outline. The individual pits of psoriasis are said to be less regular in form and in overall pattern than those of alopecia areata, but this is not always the case. When numerous, they appear randomly distributed upon the nail surface or have a geometric pattern. The latter may cause rippling or create a grid of pits. Mild pitting may also occur in association with different patterns of eczema, but is usually more subtle or localized than psoriatic pitting. Extensive pitting combined with other surface irregularities results in the appearance of trachyonychia. An isolated large pit may produce a localized full-thickness defect in the nail plate termed elkonyxis, which is found in reactive arthritis, psoriasis and following trauma.

Histologically, pits represent foci of parakeratosis, reflecting isolated nail malformation [1, 2] and are present in the fingernails of about half of psoriatics with nail involvement.

Trachyonychia

Trachyonychia presents as a rough surface affecting all of the nail plate and up to 20 nails (20-nail dystrophy) [1, 2]. The original French term was ‘sand-blasted nails’, which evokes the main clinical feature of a grey roughened surface (Figure 95.17). It is mainly associated with alopecia areata [3], psoriasis and lichen planus, although the most common presentation is as an isolated nail abnormality. In the isolated form, histology shows spongiosis and a lymphocytic infiltrate [4] of the nail matrix. It may present at birth, as a self-limiting condition in childhood or as a more chronic problem in adulthood. There is some response to potent topical, locally injected and systemic steroids, but this may be temporary.

Figure 95.17 Trachyonychia: roughened surface of up to 20 nails.

Onychoschizia (lamellar dystrophy)

Onychoschizia is also known as lamellar nail dystrophy and is characterized by transverse splitting into layers at or near the free edge (Figure 95.18) in fingers and toes, especially in infants [1]. There is a subtle distinction between the static features, such as types of split, and the subjective experience of having brittle nails. Usually these characteristics coincide, although clinicians and patients may prefer to use one term over the other. The different features can be assessed within a scoring system [2]. Variants include splitting at the lateral margins alone and multiple crenellated splits at the free edge. It is seldom associated with any systemic disorder, although it has been reported with polycythaemia [3], HIV infection [4] and glucagonoma [5] and has been referred to as a ‘syndrome’ [2].

Figure 95.18 Onychoschizia (lamellar splitting).

Scanning electron microscopy illustrates the tendency of the lamellar structure of the nail to separate after repeated immersion in water [6], although case–control studies show that occupation is not a major determinant of the condition [7]. However, efforts at retaining hydration (gloves, emollient and base coat with nail varnish) may help reverse clinical changes. Biotin has been used as systemic therapy, but the evidence for its efficacy is weak [8].

Beading and ridging

Beading and longitudinal ridging of the nails are common minor nail surface abnormalities which become more prominent with age (Figure 95.19). They are not an indication of disease.

Figure 95.19 Longitudinal ridging of the nail.

Changes in nail colour [1–7]

Alteration in nail colour may occur because of changes affecting the dorsal nail surface, the substance of the nail plate, the undersurface of the nail or the nail bed.

Nail plate pigmentation

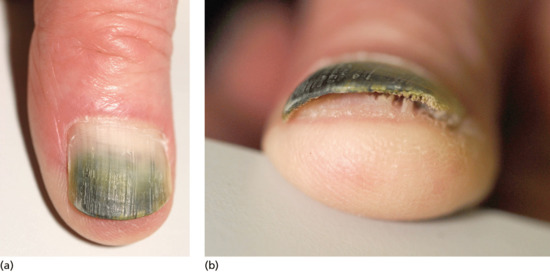

Exogenous pigment on the upper surface is easy to demonstrate by scraping the nail. If the proximal margin of the pigment is an arc matching the proximal nail fold, this is a further clue confirming an exogenous source. Nicotine is a typical pigment with the ‘quitters’ nail, which demonstrates the cessation of smoking and nicotine-free fingers for 2 months. Henna and spray tan are other common causes. Where there is onycholysis, the ventral surface of the nail can also become pigmented (Figure 95.20) and the most common instance is the green colour seen from colonization with Pseudomonas (Figure 95.21).

Figure 95.20 Orange pigmentation of onycholytic toenail due to orange dye from work-boots.

Figure 95.21 Green pigmentation of onycholytic fingernail due to Pseudomonas.

Nail colour can be changed by the incorporation of pigment into the nail plate, most commonly in the form of melanin produced by matrix melanocytes during nail formation. This produces a brown longitudinal streak the entire length of the nail. In white people this is abnormal and requires thorough assessment and, in some instances, biopsy. In darker-skinned people it is a common normal variant. The incorporation of heavy metals and some drugs into the nail plate via the matrix can also alter nail colour, such as the grey colour associated with silver or the grey-blue discoloration due to antimalarials or phenothiazines.

Loss of nail plate lucency

Nail colour may also be affected by alterations in the normal cellular and intercellular organization, such that there is loss of normal lucency. The disruption of normal nail plate formation by disease, chemotherapy, poisons or trauma can result in waves of parakeratotic nail cells or small splits between cells within the nail. Both make the nail less lucent and produce the white marks of true leukonychia (see later). Transmission electron microscopy suggests that there is a change in keratin fibre organization, which might provide an intracellular basis for altered diffractive properties. This disruption may occur at nail formation or subsequently in the case of fungal nail infection, where discoloration may start distolaterally rather than via the matrix.

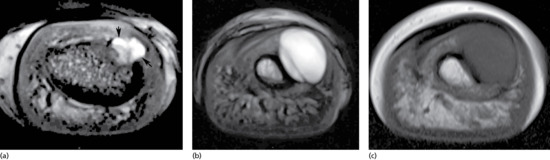

Subungual disturbances

Subungual hyperkeratosis as from dermatophyte infection or psoriasis may also change the apparent colour of the nail.

Subungual haemorrhage produces a variety of colour changes ranging from bright red to black. Splinter haemorrhages result from leakage of blood from nail bed capillaries and may be due to local trauma or to microemboli, classically from infective endocarditis.

Nail bed changes

Vascular abnormalities can affect apparent nail colour as in blue nails from cyanosis and bright red nails from carbon monoxide poisoning. In addition to such generalized vascular changes there can be localized changes, as seen with nail bed tumours. The increased vascularity of a glomus tumour in comparison with the surrounding nail bed may be the sole method of determining its location.

Dermoscopy can be very helpful in the assessment of nail plate pigmentation and underlying nail bed changes [7].

Leukonychia

True leukonychia

This is a white discoloration of the nail attributable to matrix dysfunction; it occurs in a variety of patterns [1, 2].

True hereditary leukonychia

In this rare condition, the nails are milky porcelain white. If the whole of the nail plate is affected it is called total leukonychia (Figure 95.22) [3]. In subtotal leukonychia, the proximal two-thirds are white, becoming pink distally. This is attributed to a delay in keratin maturation, and the nail may still appear white at the distal overhang.

Figure 95.22 Total leukonychia.

Transverse leukonychia (Mees’ lines) reflects a systemic disorder, such as chemotherapy or poisoning [4], or systemic infection [5] affecting matrix function. The 1–2 mm wide transverse band is in the arcuate form of the lunula and is analogous to a Beau's line, with which it is occasionally found.

Punctate leukonychia comprises white spots of 1–3 mm diameter attributed to minor matrix trauma (e.g. manicure) (Figure 95.23); it is also seen in alopecia areata. The pattern and number of spots may change as the nail grows. With longitudinal leukonychia, there is a parakeratotic focus in the matrix, sometimes attributable to Darier disease or a small tumour. Striate leukonychia is a term used in different settings. It could be argued to occupy the middle ground between the marks of Mees’ lines and punctate leukonychia being reported in both alopecia areata and chemotherapy.

Figure 95.23 Punctate leukonychia.

Apparent leukonychia

Here, changes in the nail bed are responsible for the white appearance [1, 2]. Nail bed pallor may be a non-specific sign of anaemia, oedema or vascular impairment. It may occur in particular patterns which have become associated with certain conditions.

Terry's nail is a term used to describe nails which are white proximally and normal distally and is attributed to cirrhosis, congestive cardiac failure or diabetes [3]. Nail bed biopsy reveals only mild changes of increased vascularity.

Half-and-half nails describes nails where there is a proximal white zone and distal (20–60%) brownish sharp demarcation, the histology of which suggests an increase of vessel wall thickness and melanin deposition. It is seen in 9–50% of patients with chronic renal failure and after chemotherapy (Figure 95.3).

It is unclear whether the variant Neapolitan nails, where there are bands of white, brown and red, is a version of half-and-half or Terry's nails, or a feature of old age.

Muehrcke's paired white bands are parallel to the lunula in the nail bed, with pink between two white lines. They are commonly associated with hypoalbuminaemia, the correction of which by albumin infusion can reverse the sign. They have also recently been reported following placement of a left ventricular assist device in a patient with congestive heart failure [4].

Colour changes due to drugs and chemicals [1]

There are a number of colour changes which can be caused by drugs. Yellowing of the nail is a rare occurrence in prolonged tetracycline therapy, which can also produce a pattern of dark distal photo-onycholysis, Topical 5-fluorouracil may also cause yellow nails: the whole nail is affected and returns to normal when the drug is discontinued [2, 3]. A bluish colour, is seen with mepacrine (quinacrine) [4], the nails fluorescing yellow-green or white when viewed under Wood's light. Normal nails show slight fluorescence of violet-blue colour. Hydroxyurea has been reported to result in blue lunulae [5]. Chloroquine may produce blue-black pigmentation of the nail bed [6]. Other antimalarials may produce longitudinal or vertical bands of pigmentation on the nail bed or in the nail [7].

Hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin in the nail and nail bed has been noted in children after 6 weeks of treatment with doxorubicin (adriamycin) [9, 10]. Other similar cytotoxic drugs may cause a variety of patterns of increased pigmentation [1]. However, in AIDS, longitudinal melanonychia may be seen in untreated cases [11, 12] as well as in those receiving zidovudine [9, 13].

Argyria may discolour the nails slate blue [8], and inorganic arsenic may produce longitudinal bands of pigment or transverse white (Mees' lines).

Yellow nail syndrome

The nails in yellow nail syndrome are yellow due to thickening, sometimes with a tinge of green possibly due to secondary infection with Candida or Pseudomonas. The lunula is obscured and there is increased transverse and longitudinal curvature of the nail plate with and loss of cuticle (Figure 95.24). Occasionally, there is chronic paronychia with onycholysis and transverse ridging [1]. The condition usually presents in adults, but may occur as early as the age of 8 years [2]. It does not appear to run in families [3]. Some of the clinical features may overlap with lichen planus [4], although the latter does not have the other systemic features normally seen in this syndrome.

Figure 95.24 Yellow nail syndrome.

The feature nail changes are usually accompanied by lympho-edema [5] at one or more sites and by respiratory or nasal sinus disease. The nails grow at a greatly reduced rate: 0.1–0.25 mm/week for fingernails compared with the lowest normal rate of 0.5 mm/week. All 20 nails may be involved, although often a few are spared. Histologically, in the nail bed and matrix, dense fibrous tissue is found replacing subungual stroma, with numerous ectatic endothelium-lined vessels [6]. A foreign-body reaction has been noted [7]. It has been suggested that obstruction of lymphatics by this dense stroma leads to the abnormal lymphatic function found in the affected digits in some [8] but not all [9] cases.

The oedema is variable and may affect the legs, face or hands and occasionally it is universal. In some instances, the oedema has been shown to be due to abnormalities of the lymphatics, either atresia or, in some cases, varicosity [10]. Other cases have normal lymphatics, suggesting that a functional rather than an anatomical defect may be present [11], or that perhaps only the smallest lymph vessels are defective. Although the nail changes may draw attention to the underlying lymphatic abnormality, they are found only in a minority of patients with congenital abnormality of the lymphatics. Recurrent pleural effusions have been noted [12, 13]. Chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis may also occur [12]. The condition may be associated with an increased incidence of malignant neoplasms [10, 14, 15]. Other associations include d-penicillamine therapy [5] and nephrotic syndrome [16].

In hypothyroidism and AIDS [17] there may be yellow nails, but it is debatable whether these represent yellow nail syndrome or simply the discoloration of nail associated with retarded growth [18]. There does not appear to be an inherited element in spite of original reports [19, 20].

Nail features can fluctuate enormously over time. Attempted treatments include oral and topical vitamin E, oral zinc, prednisolone and the treatment of chronic infection at other sites [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. There is debate as to whether itraconazole is of value as treatment. The drug has been demonstrated to increase the rate of longitudinal growth, but an open trial in eight patients demonstrated that half gained no benefit with respect to nail changes [26]. It is reported that results are better when itraconazole or fluconazole are combined with oral vitamin E [27]. Many authorities achieve about a 50% resolution rate, but it is not clear how much of this is part of the natural time disease course [28].

Red lunulae

Erythema of all or part of the lunula may affect all digits, but is usually most prominent in the thumb. Duration of the change will depend on the cause. When associated with cardiac failure, it may follow the course of management of the cardiac disease. When due to a subungual tumour such as a myxoid cyst or glomus tumour, it will remain until the tumour is removed. Inflammatory connective tissue causes may also result in a fluctuating course. Erythema is less intense in the distal lunula, where it can merge with the nail bed or be demarcated by a pale line, and can be obliterated by pressure on the nail plate. The appearance can fade over a few days. A single report of histological features failed to reveal vascular or epidermal changes [1]. Dotted red lunulae have been reported in psoriasis and alopecia areata, but otherwise the list of associations is so broad that it is unconvincing [2].

The exception to this is a red lunula seen in a single digit. In this setting, it often indicates a local disturbance of vascular flow, which is most likely to be a benign tumour. Glomus tumours and subungual myxoid cysts are the most common [3] and the colour may vary between blue and red.

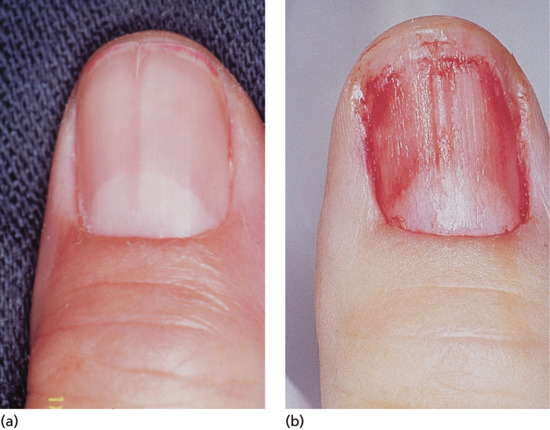

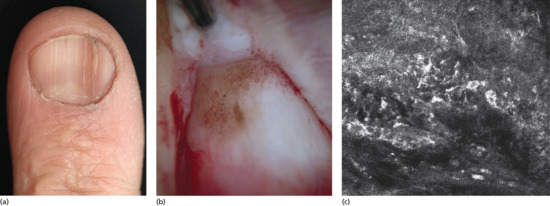

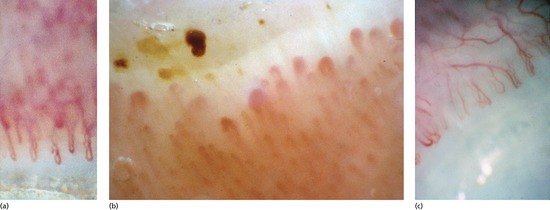

Longitudinal erythronychia (Figure 95.25)

Figure 95.25 (a) Longitudinal erythronychia. (b) The longitudinal ridge in the nail bed corresponds to the groove on the undersurface of the nail plate.

A longitudinal red streak in the nail can have several causes [1, 2]. All will have a corresponding band of thinned nail plate as part of the defect. The effect of this is a strip where blood in the underlying nail bed is seen more easily not only because the nail plate is thinner but also because blood pools in the underlying nail bed capillaries as a result of reduced compression by the overlying nail. Splinter haemorrhages may lie longitudinally within the strip. Such strips of thinned nail arise because of focally reduced proliferation within the matrix. This can be due directly to matrix pathology or may be secondary to focal pressure on the matrix with secondary loss of function.

The matrix pathology includes a spectrum of epidermal disorders. The most common are lichen planus and Darier disease, where thin longitudinal red streaks may terminate at the free edge with a split. In Darier disease, there may be a small subungual keratosis [3]. Acantholytic dyskeratotic naevus and warty subungual dyskeratoma [4] may both represent localized forms of Darier disease. Longitudinal erythronychia is also a component of acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf in which there is both clinical and pathological overlap with Darier disease.

Pressure on the matrix may be exerted by any of the full range of dermal tumours as well as tumours of the bone and cartilage that arise from the distal phalanx.

For instances where no primary disease can be identified to explain erythronychia affecting multiple nails the descriptive term ‘idiopathic polydactylous erythronychia’ has been proposed [5].

Baran and Perrin have coined the term ‘onychopapilloma’ to describe the isolated benign warty distal nail bed lesions found in association with longitudinal erythronychia for which no underlying cause can be identified [6]. The papilloma is a secondary element, given that it is found distally in the nail bed while the cause lies proximally within the matrix. However, there is a category of this disease where the matrix disease remains unclear and the distal papilloma represents the identifiable entity. Isolated longitudinal erythronychia needs careful assessment, however, as a similar clinical presentation can be due to conditions such as Bowen disease [6] or basal cell carcinoma [7] of the matrix. Biopsy may be warranted if the erythronychia is observed to change.

Not all causes of longitudinal erythronychia conform to these rules. This is particularly the case where there are multiple red streaks associated with a dermatosis and additional nail changes. It can be a feature of lichenoid diseases of the nail unit, discoid lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis and a number of other diseases where there is patchy nail atrophy. It can be difficult to decide whether histology is needed to ensure a benign diagnosis or one with no systemic implications. A narrow band (approximately 2 mm) that is not changing over 12 months or more with no other elements of the history or examination to cause concern would normally mean that continued monitoring alone would be sufficient management.

Splinter haemorrhages

Splinter haemorrhages represent longitudinal haemorrhages in the nail bed conforming to the pattern of subungual vessels [1–4]. They are most frequently seen in the distal nail bed and on the fingers of the dominant hand, reflecting trauma as the cause. In dermatological practice, they are often found in association with psoriasis, dermatitis and fungal infection of the nails. As they occur under so many conditions, their importance as a sign of disease is often exaggerated. Focal pathology may also represent a cause, as in longitudinal erythronychia and onychomatricoma (see above).

Large numbers of proximal haemorrhages with no obvious traumatic origin may indicate a systemic cause [5], such as bacterial endocarditis, antiphospholipid syndrome [6] or medication [7]. Nail bed psoriasis may dispose to splinter haemorrhages in the most used digits. Unilateral splinter haemorrhages may arise after arterial catheterization on the involved side. Examination under oil with a dermoscope may reveal greater detail.

TRAUMATIC NAIL DISORDERS

Nails may show signs of acute trauma, scars following acute trauma or chronic repetitive trauma.

Acute trauma

Acute trauma is classified with respect to severity, ranging from a small haematoma to digit amputation (Table 95.4) [1].

Table 95.4 Classification of acute nail trauma. (From Van Beek et al. [1].)

| Type | Effect | Therapy |

| I | Small haematoma associated with a small break in the nail bed | Fenestration of nail over the haematoma |

| II | Large haematoma with significant nail bed injury | Remove nail in order to identify site and nature of subungual damage |

| III | Large haematoma, nail plate displaced | X-ray may reveal fracture of terminal phalanx, usually in association with nail bed laceration which requires resorbable 6/0 suture |

| IV | Severe crush injury | Avulsion needed to reveal matrix, with multiple lacerations requiring careful reconstruction |

| V | Amputation of tip of digit, may include parts of matrix | If tip can be retrieved, it should be used as a graft. Otherwise nail bed from other sites may provide autologous grafts |

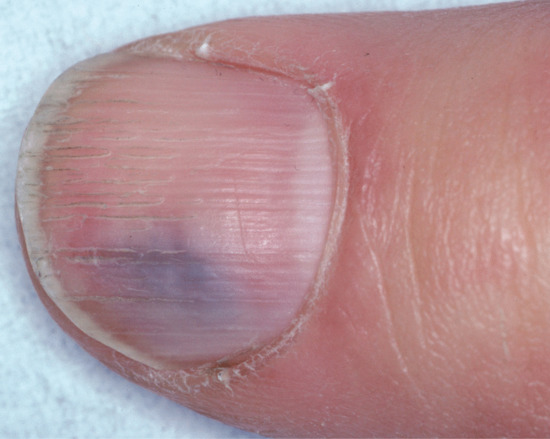

Subungual haematoma [1, 2]

Subungual bleeding is a common sign. It may present as a feature of acute trauma, with pain due to the recent event in combination with pain arising from the pressure exerted by the subungual accumulation of blood. A haematoma arising within the matrix will be incorporated into the nail plate [3]. Where the haematoma is associated with acute trauma, there is usually pain and the diagnosis is obvious. However, with less extreme trauma, a haematoma may not develop immediately and may be painless. This is most common in the toes and may give rise to clinical uncertainty as to whether it represents early subungual melanoma. A history of traumatic sporting hobbies is useful, and signs of symmetrical nail trauma and inappropriate footwear all indicate trauma as the cause of the appearance. Dermoscopy will nearly always resolve the situation [2, 4], but if it does not, making a small punch in the surface of the nail may reveal old blood as the source of pigment. Malignancies can bleed and so confirmation of blood does not refute the possibility of a tumour; however, as an isolated finding in the absence of other clues, this test should be sufficient to obviate the need for surgical exploration. An alternative is to score a transverse groove in the nail at the proximal margin of the pigment and observe over a few weeks as the discoloration grows out. If pigment continues to spread proximal to the groove, surgical exploration is warranted.

The only treatment that can be offered is to relieve the pressure, and if dealt with soon after the injury this can be done by puncturing the nail, for instance with a hot pointed implement, cautery, small drill or punch biopsy. This procedure will relieve pain and may save the nail. The possibility of an underlying fracture must be considered for larger haematomas [1].

It is stated that if more than 50% of the visible nail is affected, the nail plate should be removed. However, there is evidence to challenge this rule. A comparison between two groups of children having exploration and repair or trephination alone showed fewer complications in the latter group and considerably less investment in medical time [5]. A literature review failed to find clear evidence for avulsion [6].

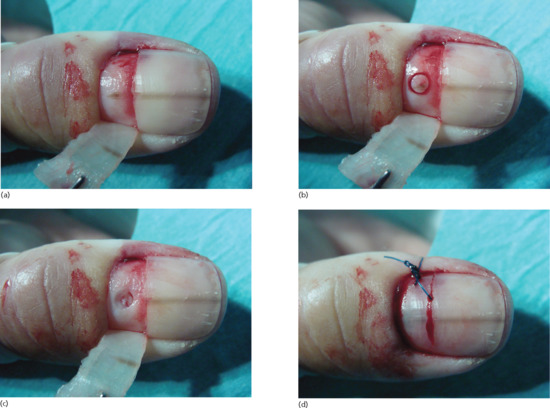

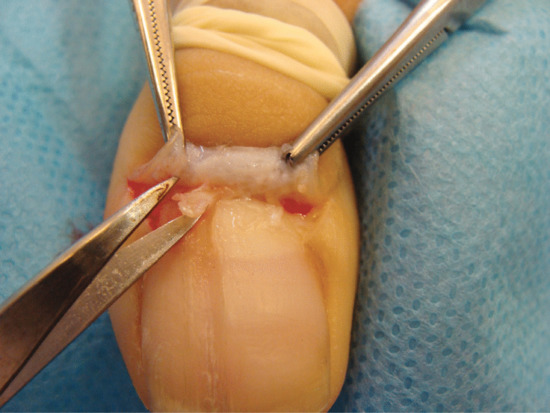

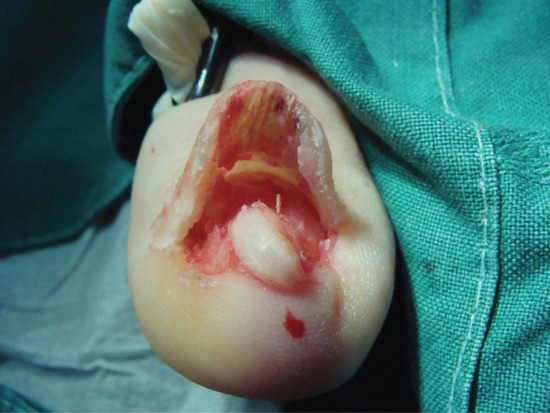

Nail bed laceration

The nail bed may be lacerated by incisions, crush and avulsion injuries. In simple injuries there is displacement of the nail plate. Initially, the nail bed damage should be assessed by avulsion, and then the nail can be replaced after any necessary nail bed repair has been performed. The nail plate can be used as a useful splint [1]; a small window for drainage of blood and exudate is made in the nail [2]. More complicated injuries may require flap or graft reconstructions and, in some instances, vascularized composite nail grafts are used with microvascular anastomoses. When the wounds arise from crush injury, fracture is relatively common. If the distal tuft has been fractured to leave fragments of bone dispersed in the soft tissues, long-term morbidity may be prevented if these are removed [3].

Delayed trauma

The most common kind of chronic deformity following an acute injury is a split nail or reduction in the length of the nail bed with consequent overcurvature of the tip of the nail.

Cure of a split nail deformity is difficult, with only a modest chance of success [1]. Sometimes, there is an associated pterygium. Treatment entails excision of the nail bed and matrix scar and, in the case of a pterygium, a split-skin graft or part of the nail plate may be placed on the ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold to help prevent recurrence of the pterygium. It is important to keep the wounded aspects of nail bed or matrix separate from the overlying nail fold after surgery, and this is often best done by returning the nail plate after soaking it in antiseptic during the procedure.

If treatment is required for a shortened distal phalanx with nail bed changes, there are two choices [2]: the entire nail can be phenolized, or a V–Y advancement flap can be performed based on two neurovascular pedicles.

Chronic repetitive trauma

Chronic repetitive trauma may take several forms. Some have been considered in other sections detailing transverse ridges produced by a habit tic (Figure 95.26), the canaliform dystrophy of Heller (Figure 95.27) and chronic paronychia (Figure 95.28).

Figure 95.26 Transverse ridges resulting from habit tic.

Figure 95.27 Median canaliform dystrophy of Heller affecting distal portion of nail plate; the enlarged lunula and transverse ridging seen proximally reflect chronic trauma.

Figure 95.28 Chronic paronychia.

Nail biting

The nail plate, periunguium and nail bed are all subject to nail biting and picking. Although fingers are most commonly involved, rarely toenails are also bitten [1]. Nail biting produces distinctive features, which are found in 60% of children, 45% of adolescents and 10% of adults [2]. The majority of moderate nail biters have no associated psychiatric disorder [3]. Focal abnormalities, such as viral warts, are often a complication, whether as a cause or as a result of the Koebner effect after biting. Severe damage may be associated with self-mutilating disorders such as Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Dental problems can arise due to nail embedded in gums or between teeth [4].

The nails are typically short, with up to 50% of the nail bed exposed. The free edge may be even or ragged. Surface change may include splitting of the nail into layers or a sand-papered effect, and the nail may acquire a brown longitudinal streak [5]. The most aggressive nail biting (onychotillomania/onychophagia) can produce subungual haemorrhage, strips of nail loss, with residual spurs or loss of the entire nail (Figure 95.29). Onychotillomania may be allied to parasitophobia when the patient picks off pieces claiming that they contain parasites [6]. A rough and irregular nail and nail fold may result with haemorrhage in the nail fold also. Many fingernails are involved. Oral pimozide may be beneficial [7].

Figure 95.29 Nail biting can be extensive, with damage to the nail folds and nail plate causing subungual haemorrhage.

Trauma followed by secondary infection involving the matrix may make nail loss permanent or result in pterygium formation. The nail folds are sometimes bitten in addition to, or as a substitute for, the nail. This can lead to bleeding and chronic paronychia with acute infective exacerbations. This in turn may lead to nail plate damage or ridging and nail fold scarring. In cases associated with infection, osteomyelitis of the terminal phalanx can develop [8, 9]. Subjects will sometimes deny nail biting and attribute the appearance to a disease that stops nail growth. Transverse grooves scored proximally in the nail plate will confirm that the nail is growing by moving distally with time. In aggressive nail biting, the groove may be eroded from the surface.

Trauma is sometimes inflicted by other nails, with pushing back of the proximal nail fold as part of a habit tic (see above). This results in serial transverse ridges and depressions running up the midline of the nail, associated with loss of the cuticle (see Figure 95.29). In more conscious forms of self-damage, sharp instruments are used to produce dermatitis artefacta of the nail unit, and the nail fold is commonly preserved [10].

Management

Treatment is often unsuccessful and cure relies largely on the motivation of the patient. Where the patient acknowledges an element of self damage, they may comply with the use of paper surgical tape as a dressing over the tip of the digit 24 h a day for 2–3 months. This needs to be replaced several times a day in some instances. In the first month, it may be helpful to combine the tape with moderate potency topical steroid to suppress any inflammation. Ensure there is no infection prior to this. Local antiseptics and antimicrobial ointments may help settle the infection secondary to nail unit damage. Antiseptics or treatments with the most bitter taste are often prescribed in the belief that this will discourage biting. This is seldom the case. Antidepressants [11] and behavioural therapy [12] have been used with some success in limited studies.

Damage from nail manicure instruments

Metal instruments, such as a nail file or scissors, wooden or plastic orange sticks, or nail whitener pencils may create acute or chronic injuries in the nail area. Onycholysis may result from using the sharp point for cleaning under the nail plate. Nails, however, are best cleaned with a nail brush and soap, because overzealous manicure, pushing back the cuticles, may result in white streaks across several nails. Cleaning around the nail with contaminated instruments may lead to acute or chronic paronychia. According to Brauer and Baran [1], it is not advisable to cut or clip the nail plate, as this produces a shearing action that weakens the natural layered structure and promotes fracturing and splitting. An emery board is preferred for shaping the fingernail by filing from the sides of the nail towards the centre.

Trauma from footwear

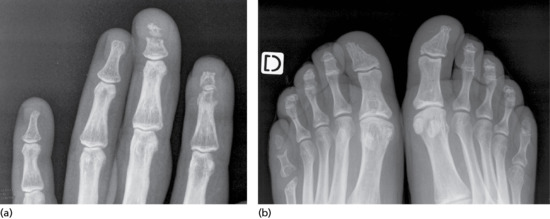

Onychogryphosis and nail hypertrophy [1–5]

Onychogryphosis is an acquired dystrophy usually affecting the great toenail, which is thickened, yellow and twisted. It is most commonly seen in the elderly often made worse because of difficulties in self care of the feet [1, 2, 4]. Trauma and biomechanical foot problems may, however, precipitate similar changes in middle age or earlier.

At one time, onychogryphosis was known as ostler's nail, because some cases could be traced to injury caused by a horse trampling on the foot of the ostler. Competitive sport is a more contemporary cause. The injury, once sustained, is aggravated by footwear. As the nail becomes longer and thicker, damage from footwear becomes progressively more important. Nail hypertrophy implies thickening and increase in length, whereas onychogryphosis implies curvature also.

Some cases of nail hypertrophy are intrinsic, and this applies especially to toenails other than the nail of the great toe. The nail becomes thick and circular in cross section instead of flat, and thus comes to resemble a claw.

In onychogryphosis, one or more nails become greatly thickened (Figure 95.30) and, with neglect, increase in length, becoming curved like a ram's horn (Figure 95.31). The nails of the great toes are most often involved, but no toenail is exempt. It is possible that the nail plate distortion produced by chronic untreated onychomycosis may be partly responsible for onychogryphosis at a later stage. In extreme cases, the free edge may press on or even re-enter the soft tissues of the foot.

Figure 95.30 Early onychogryphosis of the left great toenail.

Figure 95.31 Severe onychogryphosis resulting from neglect.

Treatment of onychogryphosis and nail hypertrophy may be either radical or palliative. Radical treatment consists of surgical removal of the nail and matrix and is recommended in those with good circulation (Figure 95.32). Palliative treatment requires regular paring and trimming of the affected nails, usually by a podiatrist using nail clippers and a file or mechanical burr. The thickened nails are extremely hard and trimming is difficult. Other causes of thickened nails include psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, Darier disease, fungal infections, pachyonychia congenita, congenital ectodermal defects and congenital malalignment of the great toenails [6].

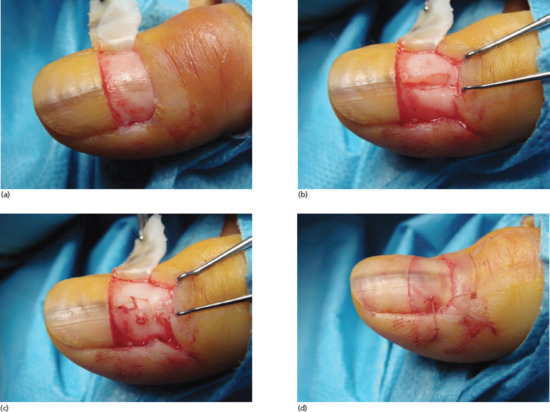

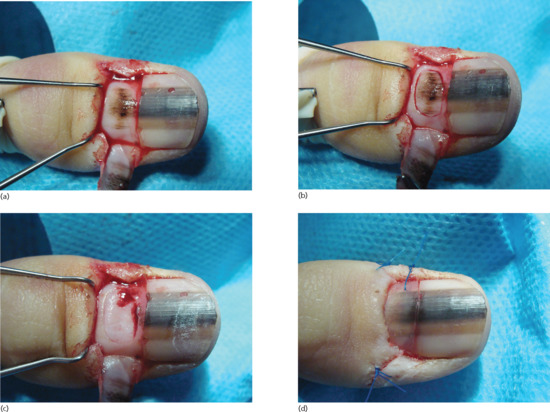

Figure 95.32 (a–c) Onychogryphosis is often best treated with ablation of the nail matrix.

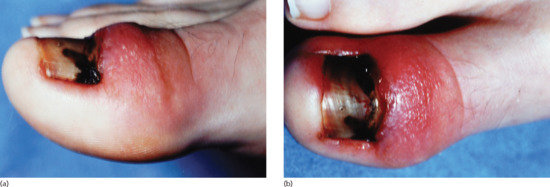

Ingrowing toenail [1, 2, 3]

The nail can ingrow on any of its four margins, although lateral ingrowing is the most common pattern and is usually found on the big toe. The soft tissue at the side of the nail (lateral nail fold) is penetrated by the edge of the nail plate, resulting in pain, inflammation and, later, the formation of granulation tissue [4]. Infection is not typically associated, although the combination of pain, redness and swelling with ooze will dispose to treatment with antibiotics. Penetration of the nail fold is often caused by spicules of nail at the edge of the nail plate which have been separated from the main portion of the nail. The great toes are those most often affected. The main cause for the deformity is lateral compression of the toe due to ill-fitting footwear, and the main contributory cause is cutting the toenails in a half-circle instead of straight across. Anatomical features, such as an abnormally long great toe and prominent lateral nail folds, are important in some cases. Sport, with the toe impacting on the inside of the shoe through kicking or other movements, can be a contributory factor.

Nail can embed in the proximal nail fold when there is disturbance of nail growth, usually through trauma. This results in dislodging of the nail upwards with a new nail growing beneath. The proximal aspect of the old nail then impacts on the ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold and this creates the same features of inflammation, ooze, swelling, redness and pain as seen when the lateral nail fold is affected. Proximal nail ingrowing is known as retronychia and is self-limiting over a matter of several months as eventually the older nail is shed. During that time, nothing effectively relieves the problem and avulsion is the treatment of choice. The replacement nail usually grows back without any problem [5].

In infancy, ingrowing toenail most commonly occurs before shoes are worn and is associated with crawling, ‘pedalling’ or wearing undersized ‘jumpsuits’ [6]; acute paronychia may be associated. Rarely, it is congenital [7] and even familial [2]. In children, ingrowing is commonly distal rather than lateral. Management is conservative in most instances, with topical steroid and antiseptic preparations. Surgery is occasionally required [8].

Clinical features

The first symptoms are pain and redness, shortly followed by swelling and pus formation. Granulation tissue then forms and adds to the swelling and discharge. More severe infection may follow (Figure 95.33a,b). There is seldom any difficulty with diagnosis. Excess nail fold granulation tissue can also be a feature of amelanotic melanoma and reactions to medications such as retinoids, ciclosporin, antiretroviral drugs and chemotherapy [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15].

Figure 95.33 (a,b) Ingrowing great toenail complicated by proximal ingrowing (retronychia).

Management (see Nail surgery section)