CHAPTER 134

Cutaneous Cysts

John T. Lear1 and Vishal Madan2

1Department of Dermatology, Manchester Royal infirmary, Manchester, UK

2Dermatology Centre, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK

Introduction and general description

The common terms used to describe cutaneous cysts are sebaceous, epidermoid and trichilemmal.

Whist clinical differentiation can be difficult, the histology is distinct and characteristic. Classification is based on the pathogenesis, nature of cyst contents and wall lining. True sebaceous cysts containing oily sebum are seen in steatocystoma multiplex.

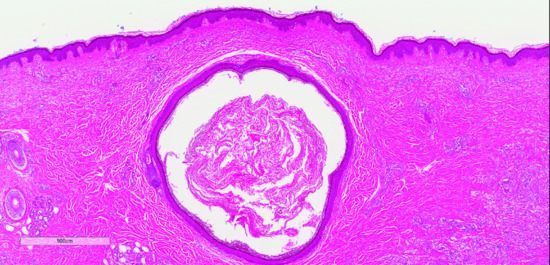

The lining wall of other cysts is keratinous in nature. These keratinous cysts can be either epidermoid (lining identical in its stratification with the epidermis and pilosebaceous duct; Figure 134.1) or trichilemmal (lining resembling the external root sheath of the hair follicle).

Figure 134.1 Histopathology of epidermoid cyst.

Epidermoid cyst

Definition and nomenclature

Cysts containing keratin and its breakdown products which are surrounded by an epidermoid wall.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

These are the commonest cutaneous cysts.

Age

They are most frequently seen in young and middle-aged adults.

Sex

No predilection for either sex.

Associated diseases

Epidermoid cysts are seen in Gardner syndrome (see Chapter 80) which is a variant of familial adenomatous polyposis and naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) (see Chapter 141) [1, 2].

Pathophysiology

The common epidermoid cyst is the result of squamous metaplasia in a damaged sebaceous gland. Many are the result of inflammation around a pilosebaceous follicle. Multiple cysts can therefore be seen in patients with more severe lesions of acne vulgaris. Some may result from deep implantation of a fragment of epidermis by a blunt penetrating injury (inclusion cysts). Those that occur as a part of Gardner syndrome and of the NBCCS are probably caused by a developmental defect.

Clinical features

History

Epidermoid cysts are most commonly seen on the face and upper trunk (Figure 134.2). As they are situated in the dermis they raise the epidermis to produce yellowish, white or skin-coloured, firm, spherical, smooth, elastic, dome-shaped protuberances that are mobile over the deeper structures. They are tethered to the epidermis, and may have a central keratin-filled punctum. The size varies from a few millimetres to more than 5 cm in diameter and the lesions may be solitary but are commonly multiple. They enlarge slowly and may become inflamed and tender.

Figure 134.2 An epidermoid cyst on the cheek.

Traumatic inclusion cysts usually occur on the palmar or plantar surfaces, buttock or knee. A history of penetrating injury may not always be obtained.

Differential diagnosis

Trichilemmal cysts are usually situated on the scalp and do not have a punctum. Lipomas are soft in their consistency. Other benign and rounded dermal tumours (Figures 134.3 and 134.4) may be mistaken for epidermoid cysts, and inflammatory granulomas such as cutaneous leishmaniasis may mimic an inflamed cyst. On rare occasions, metastatic cancers to the subcutaneous or dermal compartments may simulate a cyst.

Figure 134.3 Calcified cyst just below the eyelid margin.

Figure 134.4 Inclusion cyst following trauma to the thumb.

Complications and co-morbidities

Suppuration may occur which may lead to an offensive smelling discharge. Rupture of the cyst wall can give rise to intense inflammation. Cysts that follow acne and have been subject to recurrent inflammation may be difficult to remove completely. Calcification of the contents of epidermoid cysts cannot usually be detected clinically; when it occurs in multiple cysts of the upper part of the trunk it can give a confusing picture on chest X-ray. Dystrophic calcification of scrotal cysts can also be seen. Malignant degeneration of epidermoid cysts has been reported but is rare [3].

Disease course and prognosis

Prognosis is usually excellent.

Investigations

Diagnosis is usually clinical and can be confirmed on excision biopsy.

Management

Uncomplicated cysts may not require any treatment. A cyst that has not recently been inflamed can be dissected out. An inflamed cyst is better incised and drained. Oral antibiotics may be required if signs of infection are present. Inflamed acne cysts may respond to intralesional triamcinolone, thus obviating the need for excision.

Trichilemmal cyst

Definition and nomenclature

Trichilemmal cysts contain keratin and its breakdown products. They are usually situated on the scalp, and their wall resembles external hair root sheath; hence the name.

Introduction and general description

Trichilemmal cysts may resemble epidermoid cysts but are not as common.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

They account for about 5–10% of keratinous cysts seen by surgical pathology services [1].

Age

They are more common in middle age.

Sex

They are more common in women.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

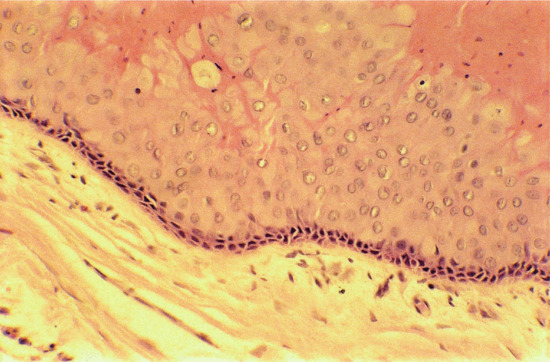

Trichilemmal cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium. There are no distinct intercellular bridges visible among the epithelial cells and they show a distinct peripheral palisading [2]. Individual cells become larger towards the lumen. The keratinization is abrupt with no intervening granular layer. The cyst contents are homogeneous and eosinophilic. Cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous material which on immunohistochemistry is positive for keratin K10 and K17. Calcification of cyst contents can occur in some cases. Rupture of the cyst can lead to foreign body giant cell reaction and significant inflammation making complete excision of the cyst difficult. Proliferating trichilemmal cysts may show gross epithelial hyperplasia of the cyst lining with minimally cystic areas mimicking clinically and histologically a squamous cell carcinoma [3]. True malignant degeneration in scalp cysts is very rare.

Genetics

They may be inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder [3].

Clinical features

Presentation

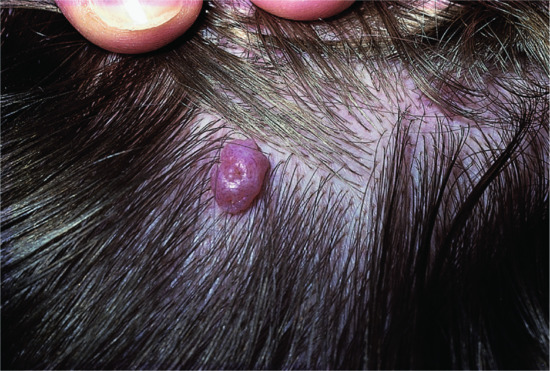

These are usually multiple and occur mainly on the scalp and present as smooth, mobile, firm and rounded nodules (Figures 134.5 and 134.6). Unlike epidermoid cysts, there is usually no punctum. Inflamed cysts may become tender and the cyst wall can rupture following an infection. The cyst wall may fuse with the epidermis to form a crypt (marsupialized cyst), which can occasionally terminate by discharging its contents and healing spontaneously. In contrast, the contents may protrude above the surface to form a soft cutaneous horn.

Figure 134.5 Clinical illustration of typical pilar cyst on the scalp.

Figure 134.6 Pilar cyst showing typical pathological features (see text).

Clinical variants

Proliferating trichilemmal tumours are uncommon solitary, multilobular, large, exophytic masses with a predilection for the scalp in elderly females.

Differential diagnosis

Epidermoid cyst and proliferating trichilemmal cyst.

Investigations

Excisional biopsy.

Management

Uncomplicated cysts can be extirpated with relative ease and usually with an intact cyst wall. Proliferating cysts need to be excised with a margin because they will recur if tissue is left behind.

Steatocystoma multiplex

Definition and nomenclature

Steatocystoma multiplex is an uncommon autosomal dominant condition, which presents as multiple dermal cysts composed of sebaceous gland lobules in their wall and containing sebum; the true sebaceous cysts.

Pathophysiology

Steatocystoma multiplex is most likely to be a genetically determined failure of canalization between the sebaceous lobules and the follicular pore.

Pathology

The cyst is situated in the mid-dermis. The cyst wall is thin and composed of keratinizing epithelium with absence of granular layer (Figure 134.7). In some sections, lobules of sebaceous glands can be seen to form part of the wall or to empty by ducts into the cyst. The contents are oily, and are composed of the unsplit esters (precursors) of sebum. They may contain hairs. Hair roots and, occasionally, sweat glands may be found connected with the cyst, and the whole complex is joined to the epidermis by a short strand of undifferentiated cells.

Figure 134.7 Histopathology of steatocytoma multiplex. A cyst lined by epithelium resembling the sebaceous duct. Mature sebaceous glands are present in the wall.

Genetics

Keratin 17 mutations have been implicated [1].

Clinical features

History

Multiple, smooth, skin coloured to yellowish, compressible dermal papules and nodules are present. Size varies from a few millimetres to 20 mm or more (Figure 134.8). The trunk and proximal part of the limbs are most commonly involved, particularly the presternal area. Lesions may also appear on the face and acral sites [2]. No punctum is usually apparent over the cyst, but there may be widespread comedones. In these cases, differentiation from acne can be difficult. If pricked, an oily fluid can be expressed. Association is with eruptive villous hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita type 2.

Figure 134.8 Multiple skin-coloured cysts of steatocystoma multiplex.

Presentation

Presentation is usually in adulthood with lesions appearing around puberty [3].

Differential diagnosis

Nodular acne, vellous hair cysts.

Complications and co-morbidities

They are usually asymptomatic. Some lesions become inflamed, suppurate and heal with scarring.

Management

First line

The number of cysts makes excision impractical in most cases. Oral isotretinoin may reduce the size of pre-existing cysts or reduce the rate of development of new lesions [4].

Second line

Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of the cysts appears to be effective [5].

Milium

Definition

These are small subepidermal keratin cysts.

Introduction and general description

Milia are isolated or grouped small uniform spherical white papules with a smooth non-umbilicated top.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Milia are quite common at all ages.

Associated diseases

Rombo and Bazex syndromes.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Second-degree burns, epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus, following dermabrasion, in areas of chronic topical corticosteroid-induced atrophy and radiotherapy.

Pathology

Milia that follow blistering can often be traced to eccrine sweat ducts in serial sections. Those at the margin of an irradiated area are usually situated in the distorted remnant of the pilosebaceous duct. The much more common milia of the face are found within the undifferentiated sebaceous collar that encircles many vellus hair follicles. The milial cyst has a stratified squamous epithelial lining with a granular layer. The white milium body is composed of lamellated keratin.

Clinical features

Presentation

Milia are firm, white or yellowish, rarely more than 1 or 2 mm in diameter and appear to be immediately beneath the epidermis. They are usually noticed only on the face, and occur in the areas of vellus hair follicles, on the cheeks and eyelids particularly (Figure 134.9).

Figure 134.9 Milia on the periorbital area.

Clinical variants

Milia en plaque appear as a cluster of milia on an erythematous, oedematous base. These are most commonly seen in the post-auricular area.

Management

First line

Incision of the overlying epidermis and expressing the contents is curative. Recurrence is uncommon. Spontaneous disappearance occurs in many milia in infants.

Second line

Laser ablation or puncturing the milia or electrodessication can be very effective. Topical tretinoin may be effective.

References

Epidermoid cysts

- Juhn E, Khachemoune A. Gardner syndrome: skin manifestations, differential diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010;11:117–22.

- Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dermatol Clin 1995;13:113–25.

- Morritt AN, Tiffin N, Brotherston TM. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in epidermoid cysts: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65:1267–9.

Trichilemmal cysts

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, Arunkumar SP. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci 2013;5:124–8.

- Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol 1976;94:379–90.

- Wilson Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol 1966;94:11–19.

Steatocystoma multiplex

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:475–80.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:396–9.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol 2002;29:152–6.

- Statham BN, Cunliffe WJ. The treatment of steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 1984;111:246.

- Bakkour W, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg 2014;40:658–62.

Epidermoid cysts

- Juhn E, Khachemoune A. Gardner syndrome: skin manifestations, differential diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010;11:117–22.

- Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dermatol Clin 1995;13:113–25.

- Morritt AN, Tiffin N, Brotherston TM. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in epidermoid cysts: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65:1267–9.

Trichilemmal cysts

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, Arunkumar SP. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci 2013;5:124–8.

- Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol 1976;94:379–90.

- Wilson Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol 1966;94:11–19.

Steatocystoma multiplex

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:475–80.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:396–9.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol 2002;29:152–6.

- Statham BN, Cunliffe WJ. The treatment of steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 1984;111:246.

- Bakkour W, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg 2014;40:658–62.