CHAPTER 135

Lymphocytic Infiltrates

Fiona Child1 and Sean J. Whittaker2

1St John's Institute of Dermatology, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

2Division of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Kings College London, London; and St John's Institute of Dermatology, Guy's and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Pseudolymphoma

Definition and nomenclature

This is not a specific disease. Pseudolymphomas are benign lymphoid proliferations in the dermis, which may be difficult to distinguish from a low-grade malignant lymphoma and possibly may rarely transform to a lymphoma in some cases [1, 2, 3]. The term cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia has been suggested and both terms are more commonly used to describe a pathological rather than a clinical appearance. Pseudolymphomas may be of T-cell or B-cell origin. B-cell pseudolymphoma is also called lymphocytoma cutis. T-cell pseudolymphoma may be idiopathic but may also include lymphomatoid drug eruptions, lymphomatoid contact dermatitis and actinic reticuloid. Confusion between pseudolymphoma and lymphoma can easily arise if a biopsy is submitted to the pathologist without an adequate history of recent events such as drug ingestion or scabies infestation.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

These are not established.

Age

It is more common in patients less than 40 years old.

Sex

Localized pseudolymphoma (B-cell pattern) has a female to male ratio of 2 : 1.

Ethnicity

No link with ethnicity has been established.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Both B- and T-cell pseudolymphomas may occur in tattoos as a reaction to certain pigments [4, 5], after vaccination [6], trauma, acupuncture [7] or in association with infections. T-cell pseudolymphomas may arise as a form of adverse drug reaction. The range of causative drugs is wide but includes anticonvulsants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β-blockers, cytotoxics, antirheumatics, antidepressants and many others [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Persistent contact dermatitis may also produce a T-cell pseudolymphoma [13, 14].

Pathology [15-20]

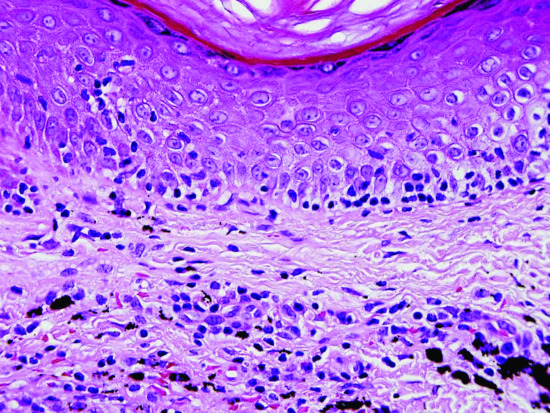

If the distinction between lymphoma and pseudolymphoma is to be made, it is vital to give the pathologist a good clinical history, as the pathological, phenotypic and molecular differentiation is not absolute. A T- or B-cell lymphoid proliferation is present, which is usually nodular in B-cell and nodular or band-like in T-cell proliferations (Figure 135.1). There may be a few mitotic figures but there is minimal atypical cytology. In B-cell proliferations germinal centres may or may not be present, but typically reactive germinal centres have tingible body macrophages. T-cell pseudolymphomas do not usually show significant epidermotropism. Rarely, the lymphoid cells may be very bizarre and resemble mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes seen in vitro during the lymphocyte transformation test [21].

Figure 135.1 H&E-stained section of skin from a patient with a pseudolymphoma with conspicuous tagging of lymphocytes along the basal epidermis, resembling lichenoid mycosis fungoides; tattoo pigment is present in the dermis. Original magnification 400×.

(Courtesy of Dr Alistair Robson.)

Immunophenotypic studies show a normal T-cell phenotype and a mixed κ/λ expression. When germinal centres are present, Bcl-2 is not expressed in B-cell pseudolymphomas [22]. T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin gene analysis usually show a polyclonal pattern, but rarely a monoclonal pattern may be detected, suggesting a neoplastic proliferation. The significance of this finding, however, is unclear at present [23, 24, 25, 26, 27].

Causative organisms

Persistent nodular scabies and arthropod bites may cause a T-cell pseudolymphomatous histology [28, 29, 30], possibly caused by retained foreign material stimulating a persistent antigenic reaction. B-cell pseudolymphomas may be associated with Borrelia burgdorferi [31, 32], Leishmania [33], molluscum contagiosum [34] and herpes zoster [35, 36] infections.

Clinical features

Presentation and clinical variants

B-cell pseudolymphomas usually present as solitary or multiple, itchy or asymptomatic, smooth surfaced or excoriated, dermal papules and nodules, which may also be subcutaneous. T-cell pseudolymphomas present with solitary or scattered papules, nodules and plaques (Figure 135.2), but can also present as persistent erythema, which may develop into an exfoliative erythroderma [37], particularly when caused by drug reactions or contact dermatitis; there may also be persistent lymphadenopathy, low-grade fever and other symptoms including headache, malaise and arthralgia.

Figure 135.2 Multiple nodules and plaques of T-cell pseudolymphoma affecting the face due to a drug eruption induced by co-trimoxazole.

Differential diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis is of cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphoma. Careful clinicopathological correlation is vital in order to distinguish between them. Primary cutaneous, small/medium, CD4-positive, pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma is a rare, but increasingly recognized, provisional subcategory of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It is associated with a favourable prognosis and may have very similar clinical and histological features to pseudolymphoma [38, 39].

Complications and co-morbidities

Reports suggest cases have evolved to lymphoma; however, many of these cases may have been subtle low-grade lymphoma initially.

Disease course and prognosis

If a potential cause is identified it should be removed as soon as possible, but it may take weeks or months for the cutaneous reaction to subside. In the absence of an identifiable cause, pseudolymphomas may be persistent. The diagnosis and prognosis of pseudolymphoma should be guarded, as in a number of cases clear progression from apparent pseudolymphoma to malignant lymphoma has been recorded [1, 2, 3, 23, 40]. This appears to confirm the concept that chronic, initially benign, reactive inflammatory conditions may very rarely progress to frank lymphoma or that these conditions may be low-grade lymphomas initially, which then transform and adopt a more obvious malignant cellular cytology/morphology.

Investigations

A skin biopsy is needed for histology and TCR/immunoglobulin gene rearrangement analysis. Borrelia burgdorfori serology (B-cell pseudolymphoma) should be checked. A patch test may be indicated if lymphomatoid contact dermatitis is suspected. In severe cases of drug-induced T-cell pseudolymphoma, full blood count (FBC) and liver function tests should be checked as eosinophilia and hepatitis may occur.

Management

The suspected cause should be removed. This is easiest in the case of an adverse drug reaction, but it may take weeks or even months for the cutaneous reaction to subside. Drug-induced pseudolymphomas may also present many months or even years after the therapy has been started. There are no randomized clinical trials; all treatments are based on anecdotal reports and small studies. Topical steroids may be given for symptomatic relief of itch and intralesional steroids can be injected into solitary small nodules. Hydroxychloroquine may be used for generalized disease. Treatments for lymphocytoma cutis are discussed later in the chapter.

Patients with extensive cutaneous involvement and systemic symptoms, usually when a causal drug is suspected, may require admission for supportive measures.

Pityriasis lichenoides

Definition and nomenclature

The cause of pityriasis lichenoides is unknown. Clinically, pityriasis lichenoides is divided into two main conditions: pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA or Mucha–Habermann disease). The distinction between PLC and PLEVA is based on clinical morphology and histology rather than disease course. A third, much more rare and aggressive form, febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease (FUMHD) also occurs [1, 2, 3, 4]. Nosologically, pityriasis lichenoides has been considered to be a variant of parapsoriasis and to show overlap with lymphomatoid papulosis (see Chapter 140) [1, 5].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The incidence is not known, although PLC is the most common type. Both PLEVA and PLC last on average 18 months with an episodic course.

Age

It occurs most frequently in children and young adults. A recent large study suggested that PLEVA is the most common pattern in younger children (57% compared with 37% PLC and 6% mixed pattern) [6]. All types are rare in infancy and old age, but PLEVA has been reported at birth [7]. Most cases of FUMHD occur in the second or third decade of life [3].

Sex

In children with PLC there is a male predominance [8] but in adults there is an approximately equal sex incidence [3, 8]. There is a strong male predominance in FUMH (c. 75%) [3].

Ethnicity

Pityriasis lichenoides has been reported mainly from Europe and America, but there is no specific geographical variation in incidence.

Associated diseases

PLC-like lesions have been described in patients with typical features of mycosis fungoides, and identical T-cell clones have been identified in both types of cutaneous lesions from the same patients, which may explain the overlap with ‘parapsoriasis’ [9]. Evidence of T-cell clonality has been detected in most cases of PLEVA and some cases of isolated PLC [8, 10, 11], and in FUMHD [12, 13]. PLEVA has also been reported with an associated lymphoma [14]. These findings suggest that at least some cases represent a cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell lymphoproliferative disease, which may coexist with other primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Reported triggers include medications, such as chemotherapeutic agents, oral contraceptives, astemizole, and possibly herbs in addition to infective (mainly viral) triggers.

Pathology [3, 15, 16]

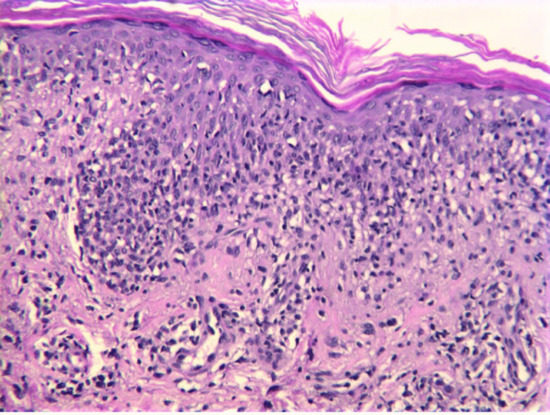

The histology varies with the stage, intensity and extent of the reaction; changes are more severe in PLEVA than in PLC. In early lesions, an infiltrate of predominantly small lymphocytes surrounds and involves the walls of dilated dermal capillaries, which show endothelial proliferation (Figure 135.3). In PLEVA, the infiltrate may be deep, dense and wedge-shaped rather than predominantly perivascular. The epidermis is oedematous, with an interface dermatitis comprised mainly of CD8+ lymphocytes. Some necrotic keratinocytes are generally present, especially in PLEVA. Intraepidermal and perivascular extravasation of erythrocytes is typical. Later, over the centre of the lesion, a parakeratotic scale forms, containing lymphocytic pseudo-Munro abscesses and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Mild cytological atypia can be present. If the reaction is still more intense, as occurs in FUMHD, frank necrosis occurs and the lesion may be difficult to distinguish from other forms of acute necrosis of the skin on histology. In FUMHD there may be marked fibrinoid necrosis of deep vessels with luminal thrombi, partial necrosis of follicles and complete necrosis of eccrine glands.

Figure 135.3 H&E-stained section of skin illustrating a florid lymphocytic infiltrate obscuring the dermal–epidermal junction. There is no cytological atypia. Original magnification 400×.

(Courtesy of Dr Alistair Robson.)

Immunofluorescence studies variably demonstrate IgM, C3 and fibrin in the vessel walls of fresh lesions [15]. Macrophages are increased in number and Langerhans cells are decreased. HLA-DR is expressed by the lymphocytic infiltrate and the overlying epidermis.

There is a histological resemblance to many other conditions, including common inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and resolving eczema. The most important is the distinction from parapsoriasis and particularly (as they may also be clinically similar) differentiation between PLEVA and lymphomatoid papulosis. The most useful distinction from lymphomatoid papulosis is that the latter shows a more pronounced collection of papulonodular lesions with a predominant population of large atypical CD30+ cells (usually CD4+ but occasionally CD8+) whereas atypical CD30+ cells in pityriasis lichenoides are usually few and invariably CD8+ [9]. Cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) and T-cell intercellular antigen 1 (TIA-1) are expressed in both conditions and indicate a proliferation of cytotoxic T cells [17].

Causative organisms

Histological features of an underlying vasculitis in PLEVA suggest an immune complex-mediated pathogenesis. In support of this hypothesis there are many documented cases of infective triggers. Seasonal peaks of onset in autumn and winter [6], and rare familial outbreaks [18], suggest the possibility of an infectious trigger. Numerous potential infectious triggers have been summarized in reviews [3, 16], and include toxoplasmosis [19, 20], cytomegalovirus [21], parvovirus B19 [22, 23, 24], adenovirus [25], Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) [26, 27], herpes simplex [28], varicella-zoster virus [29, 30], HIV [31], measles and MMR vaccines [32, 33], streptococci [34], staphylococci and Mycoplasma infections. In many such reports, there is evidence of seroconversion at the time of onset or of resolution of pityriasis lichenoides when the infective trigger was treated, supporting a causal relationship. Parvovirus B19 genomic DNA was identified in lesional skin in 30% of patients with PLEVA [35]. A therapeutic response of PLC to tonsillectomy in the setting of chronic tonsillitis has been reported [36], as well as responses to antibiotics such as erythromycin [1, 37, 38] or tetracycline [39]. Resolution has also followed pegylated interferon and ribavirin in a patient with hepatitis C infection [40]. In a recent study, human herpesvirus 8 DNA in lesional skin was discovered in 11 (21%) patients with pityriasis lichenoides, but in none of the controls [41].

Clinical features

History and presentation [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 37, 41-44]

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta The eruption develops in crops and consequently appears polymorphic. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, headache, malaise and arthralgia may precede or accompany the onset of lesions. The initial lesion is an oedematous pink papule that undergoes central vesiculation and haemorrhagic necrosis. In the vesicular forms the vesicles may be small or so large that the eruption appears frankly bullous [42]. The rate of progression of individual lesions varies greatly, as does the frequency and extent. New lesions may cause irritation or a burning sensation as they appear, but often they are asymptomatic. The trunk, thighs and upper arms, especially the flexor aspects, are chiefly affected, but the eruption may be generalized. Lesions of the palms and soles are less common, and the face and scalp are often spared; erythematous or necrotic lesions of the mucous membranes may be present. Lesions heal with scarring, which may be varioliform. PLEVA in pregnancy carries a potential risk of premature labour if there are mucosal lesions in the region of the cervical os [43].

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease In the acute ulceronecrotic form there is high fever and large necrotic lesions (Figure 135.4); new crops may continue to develop over many months. About 50–75% of cases occur in adults, with a fulminating course that may even be fatal [1, 2, 44, 45]. General malaise, weakness, myalgia, neuropsychiatric symptoms and lymphadenopathy occur, with non-specific serological markers of inflammation such as raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein; there may be serological evidence of associated viral infection.

Figure 135.4 Crusted necrotic and ulcerative plaques in a young man with febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica The characteristic lesion is a small, firm, lichenoid papule 3–10 mm in diameter, and reddish brown in colour (Figure 135.5). An adherent ‘mica-like’ scale can be detached by gentle scraping to reveal a shining brown surface – a distinctive diagnostic feature. Over the course of 3 or 4 weeks, the papule flattens and the scale separates spontaneously to leave a pigmented macule, which gradually fades. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation may occur, and is occasionally persistent, but scarring is unusual in PLC. The body site distribution is the same as for PLEVA but an isolated acral form may occur [46, 47, 48]; segmental forms have been reported [49].

Figure 135.5 (a) Scattered scaly papules on the trunk in a patient with pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC). (b) Close up of individual lesions of PLC showing the mica-like scale.

Differential diagnosis

The acute vesicular form must be distinguished from varicella; acute necrotic lesions may suggest other necrotic skin infections, vasculitis or pyoderma gangrenosum. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a particularly difficult differential diagnosis in patients with necrotic lesions in view of its histological similarity, discussed earlier, although lymphomatoid papulosis is usually characterized by less vesicular and more necrotic papulonodular lesions than those of PLEVA.

PLC must be differentiated from guttate psoriasis and lichen planus. The acral form of PLC in particular may mimic psoriasis, and secondary syphilis needs to be excluded, especially if the palms and soles are involved or if there are mucosal lesions. The single, detachable ‘mica-like’ scale on the red-brown papule is a characteristic sign of PLC. Gianotti–Crosti syndrome is less likely to be confused with pityriasis lichenoides, but insect bites and drug eruptions should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Complications and co-morbidities

In FUMH and PLEVA, ulcerated lesions may become secondarily infected.

Disease course and prognosis

The course of pityriasis lichenoides varies. If the onset is acute, new crops may cease to develop after a few weeks, and many cases are clear within 6 months. However, acute recurrences may occur over a period of years, or may become chronic. In some cases, all lesions are of the chronic scaling type from the onset, and new crops of similar lesions may develop from time to time over the years. Uncommonly, acute attacks occur after chronic lesions have been present for months or years. In general, the immediate prognosis is said to be better when the onset is acute and the lesions in successive crops are also of the acute type, but one large study of 124 children showed only a small difference in clearance times between PLEVA (mean 18 months) and PLC (mean 20 months) [6]. A smaller study comparing adults and children found that the disease tended to run a longer course in children, with a greater extent of lesions, more pigmentation and poor response to conventional treatments [50].

Investigations

A skin biopsy is needed for histology, immunohistochemistry and TCR gene rearrangement analysis. In cases of FUMH, a causative infectious agent may be implicated and investigations should be tailored to each patient's presentation. They may include antistreptolysin (ASO) titre, throat swab, hepatitis, EBV and HIV serology, monospot and investigations for Toxoplasma infection.

Management

Management of both PLC and PLEVA are similar, and, in the small number of controlled trials that have been conducted, both conditions are included. Topical corticosteroids may improve symptoms and healing of lesions but do not alter the course of the disease. There are also reports of disease clearance with the application of topical tacrolimus ointment [51, 52]. In adults, phototherapy [3] is usually the first line treatment of choice, and includes natural sunlight, UVB [53], narrow-band UVB [54, 55], UVA-1 [56] and psoralen and UVA (PUVA) [57]. Responses are also reported with the addition of acitretin to PUVA in refractory disease [58].

A randomized trial comparing narrow-band UVB with PUVA showed no significant difference in response rate between the two therapies [55]. In children, treatment options include antibiotics such as tetracyclines [59] or erythromycin [6, 38, 50] (preferred in young children because of the dental pigmentation side effects of tetracycline). In more aggressive or refractory disease of PLEVA or FUMHD pattern, and less commonly in PLC, various immunosuppressive agents including methotrexate [60], ciclosporin and dapsone [3] and intravenous immunoglobulin [61] may prove successful. Elevated levels of serum tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in a patient with FUMHD [62] has resulted in the successful use of anti- TNF-α inhibitors in a small number of patients [63, 64]. However, there are also reports of infliximab and adalimumab causing pityriasis lichenoides [65, 66, 67].

Parapsoriasis

This term has caused confusion since its introduction in 1902 because of the lack of a universally agreed definition of the clinical entities to be included. For this reason, many dermatologists prefer not to use the term at all, and to substitute one of the many synonyms for clinical conditions that might be included in one of the parapsoriasis groups. There is unresolved controversy as to whether two of the parapsoriasis variants are either precursors of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides (MF) variant (so-called premycotic eruptions) or established, but early, MF from the outset. There is a broad division of parapsoriasis into small and large plaque variants, each with a number of synonyms. The evidence that the majority of cases of small plaque parapsoriasis (SPP) are a chronic, benign condition is reasonable. In contrast, large series of patients with large plaque parapsoriasis (LPP) have recorded the development of definite MF in 11% of cases but whether these cases were MF from the outset remains unclear at present [1]. However, a more recent retrospective study of both SPP and LPP showed that 10% of patients with SPP and 35% of those with LPP evolved into MF over a median period of 10 and 6 years, respectively [2]. Unfortunately, TCR gene rearrangement studies have been inconclusive, although the proportion of cases with evidence of monoclonality is lower in SPP [3, 4, 5, 6]. Long-term follow-up of these cases is required.

Small plaque parapsoriasis

Definition and nomenclature

This is a chronic asymptomatic condition, characterized by the presence of persistent, small, scaly plaques, mainly on the trunk [1, 2, 3].

Epidemiology

Incidence

The incidence of SPP is not known and may be underreported as it is usually asymptomatic.

Age

It normally presents in middle age with a peak incidence in the fifth decade.

Sex

It is more common in males, with a 3 : 1 male to female incidence.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

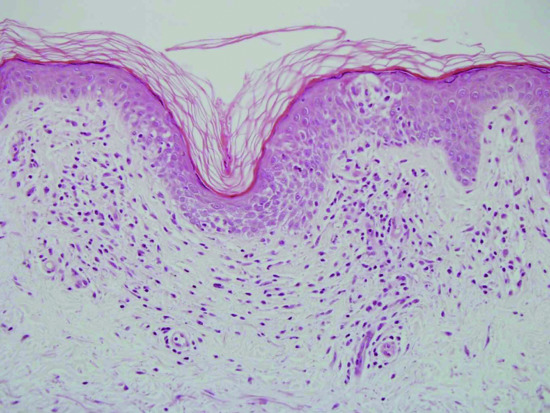

This is non-specific. There are small focal areas of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, and in the underlying dermis there are small aggregates of morphologically normal CD4+ T cells, mainly around the vasculature. There is no epidermotropism, and no Pautrier microabscesses (Figure 135.6).

Figure 135.6 H&E-stained section of skin illustrating spongiosis, light lymphocytic dermal inflammation and exocytosis – features commonly seen in chronic superficial scaly dermatitis. Original magnification 100×.

(Courtesy of Dr Alistair Robson.)

Immunophenotypic studies reveal a normal mature T-cell phenotype. Reports have identified ‘dominant T-cell clones’ in some cases of SPP using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis [3, 4]. The significance of this observation in terms of its relationship to MF and disease progression is not yet clear. There is also a report of a higher frequency of clonal T cells in the peripheral blood of patients with SPP [6] with no evidence of clonality in the skin, although the significance of this finding is questionable because non-pathological T-cell clones can be found in the peripheral blood of patients with benign cutaneous infiltrates and normal, healthy volunteers [7, 8].

Clinical features

Presentation

The lesions usually appear insidiously and asymptomatically on the trunk and, to a lesser extent, on the limbs of young adults. Individual lesions are monomorphic, round or oval erythematous patches, 2.5–5 cm in diameter, with slight scaling (Figure 135.7). Some have a slightly yellow, waxy tinge. The digitate dematosis is a distinctive form, which consists of finger-like projections following dermatomes on the lateral aspects of the chest and abdomen. The lesions persist for years or even decades, and may be more obvious during the winter. There is sparing of the pelvic girdle area and the striking polymorphic appearance of individual patches seen in MF is lacking.

Figure 135.7 Typical pattern of chronic, superficial, scaly dermatosis showing finger-like projections on the sides of the torso.

Differential diagnosis

This includes other inflammatory dermatoses that may present with scaly, erythematous patches and includes discoid eczema, guttate psoriasis, pityriasis versicolor and allergic contact dermatitis. Early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma should also be considered.

Disease course and prognosis

It may persist for many years and subsequently resolve spontaneously. There are reports of progression to MF in a minority of cases [1, 2, 9].

Investigations

The diagnosis is usually made clinically as histology is non-specific. However, a skin biopsy should be taken for histology and TCR gene rearrangement studies if there is any suspicion of MF.

Management

Often, little treatment is needed. Emollients may help control the scaling. There are no randomized clinical trials but retrospective and prospective studies have shown that both PUVA and narrow-band UVB phototherapy may result in temporary clearance of the lesions [10, 11, 12, 13]. Both complete and partial responses have also been reported with topical nitrogen mustard [14].

Large plaque parapsoriasis

Definition and nomenclature

This is a chronic condition characterized by the presence of fixed, large, atrophic, erythematous plaques, usually on the trunk and occasionally on the limbs.

Epidemiology

Sex

There is a slight male predominance.

Associated diseases

It may progress to MF [15] although it may be early-stage MF from the outset.

Pathophysiology

There is frequently epidermal atrophy, and a lichenoid or interface reaction may also be seen at the dermal–epidermal junction. There is a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis, and there may also be free red cells present. The histology is not diagnostic for MF and most biopsies only show a mild dermatitis. Immunophenotypic studies reveal a normal T-cell phenotype. TCR gene rearrangement studies have shown a clonal T-cell population in the skin in six of 12 patients, but progression to overt cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was only noted in one of the 12 patients [18].

Clinical features

Patients present with persistent, large, yellow-orange atrophic patches and thin plaques on the trunk and limbs. The involvement of covered skin on the breast and buttock areas suggests MF and in these cases patches and plaques may show striking polymorphism and poikiloderma with slow progression [19].

Investigations

A skin biopsy is needed for histology, immunohistochemistry and TCR gene rearrangement analysis.

Management

Topical emollients, UVB and PUVA are all helpful in offering symptomatic relief [20, 21]. Topical nitrogen mustard can also lead to clearance of disease [22]. There is one report of the successful use of the excimer laser (308 nm) with long-term benefit [23]. Topical steroids should be used with caution because of the atrophic nature of the condition. In view of the risk of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, patients should be offered intermittent dermatology review.

Lymphocytoma cutis

Definition and nomenclature

Lymphocytoma cutis is a benign, cutaneous, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder that is included as a subtype of pseudolymphoma. It encompasses a spectrum of benign B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases that share clinical and histopathological features. It occurs as a response to known or unknown antigenic stimuli that result in the accumulation of lymphocytes and other inflammatory cells in a localized region on the skin.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Not known, although in Europe lymphocytoma cutis associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection occurs primarily in areas where the Ixodes ricinus tick is endemic [1].

Age

It can occur at any age but is most commonly seen in early adulthood. Borrelial lymphocytoma is more common in children than adults [2].

Sex

There is a female preponderance, with a female to male ratio of approximately 2 : 1 [3].

Ethnicity

There is no racial predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology [3-6]

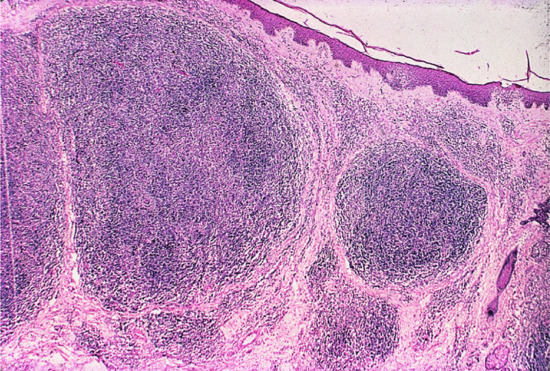

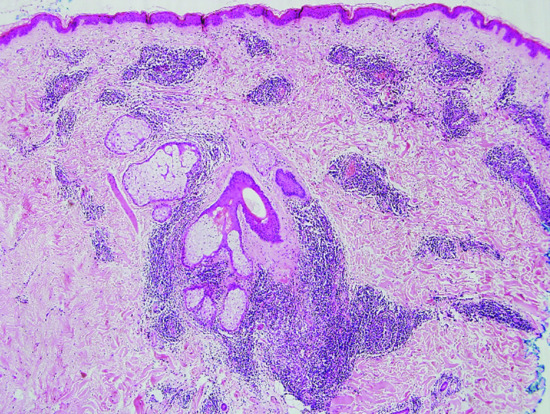

The epidermis is usually unaffected and is often separated by a relatively acellular grenz zone from the dermis, which is replaced by a nodular, dense infiltrate extending through the full thickness of the dermis but without cellular atypia (Figure 135.8). In classic cases, lymphocytes and histiocytes form a follicular arrangement (germinal centre) resembling the appearance of a lymph node (Figure 135.9). Mitotic figures may be visible in the cells of the follicles and occasional eosinophils may also be present. Appendages and blood vessels are spared. Some cases lack well-defined lymphoid follicles, although the histological appearance with normal lymphocytes and histiocytes is otherwise similar. The majority of lymphocytes in the dermis are B cells. In cases with well-formed germinal centres, a cuff of reactive T cells may be seen around the periphery of the main B-cell aggregate. The germinal centres also retain cells that express CD10 and BCL-6 but expression of BCL-2 by germinal centre cells is not seen. There is polytypic expression of κ and λ light chains. The histological differential diagnosis includes primary cutaneous lymphoma, particularly of marginal zone origin.

Figure 135.8 H&E-stained section of skin illustrating a dense, nodular infiltrate in the dermis. There is a Grenz zone and a normal epidermis. Original magnification 20×.

(Courtesy of Dr Alistair Robson.)

Figure 135.9 H&E-stained section demonstrating the large reactive lymphoid follicles that can be seen in lymphocytoma cutis.

Causative organisms

Infectious stimuli include Borrelia burgdorferi [1, 2], molluscum contagiosum and Leishmania donovani [7]. Lymphocytoma cutis may also present in scars from previous herpes zoster virus infections [8].

Environmental factors

Other reported stimuli causing lymphocytoma cutis include trauma, vaccinations [9], allergy hyposensitization injections [10], drug ingestion, arthropod bites, acupuncture, metallic pierced earrings [11] and treatment with leeches [12].

Clinical features

Presentation

Most patients show solitary or grouped, asymptomatic, erythematous or plum-coloured papules, nodules or plaques, most commonly on the face, chest and upper extremities (Figure 135.10). Occasionally, they may have a translucent appearance. They are usually asymptomatic but can occasionally be itchy or tender. They enlarge slowly and may reach a diameter of 3–5 cm. Associated sunlight sensitivity has been reported in some patients [13]. Bafverstedt [14] has described an unusual form of lymphocytoma that presented as a solitary tumour of the scrotal skin. Disseminated or miliary lymphocytoma cutis is also reported [15, 16]. Lymphocytoma cutis secondary to Borrelia infection is most frequently seen at sites with low skin temperature such as the earlobes, nipples, nose and scrotum [1].

Figure 135.10 Extensive dermal nodules of lymphocytoma cutis on the face.

Differential diagnosis

Histological examination should distinguish lymphocytoma cutis from granulomatous disorders including sarcoidosis, granuloma faciale and rosacea. Distinction from primary cutaneous B-cell marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) is difficult, although the presence of atypical lymphoid cells, immunoglobulin light chain restriction and detection of a clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangement by molecular analysis would suggest a primary cutaneous MZL. Insect bite reactions may also be impossible to distinguish from lymphocytoma cutis.

Jessner's benign lymphocytic infiltration, tumid discoid lupus erythematosus (LE) and polymorphic light eruption can also cause difficulties. However, in Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate, which characteristically waxes and wanes in severity, the dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is dominated by T cells. The presence of basal cell liquefaction degeneration and positive direct immunofluorescence helps distinguish LE.

Disease course and prognosis

The course of disease varies but is often chronic and indolent. If the cause is identified, the lesions may resolve once the cause is removed. Some lesions resolve spontaneously. Long-term follow-up of these patients suggests that a small proportion progress to or begin as a primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (MZL) [5, 17, 18].

Investigations

A skin biopsy is needed for histology, immunohistochemistry and immunoglobulin gene analysis. Serology is required to test for Borrelia burgdorferi. Patch testing may be requested if a possible contact allergen is suspected.

Management

There is no treatment of proven value for lymphocytoma cutis, with only anecdotal reports and small case series, and no clinical trials. If a causal agent is identified, it should be removed if possible.

First line therapies for localized disease include excision, topical or intralesional corticosteroids and oral antibiotics if the Borrelia serology is positive. In generalized disease, hydroxychloroquine [19] may be of benefit. Second line therapies for localized disease with reported success include superficial radiotherapy [20], intralesional interferon α (IFN-α) [21, 22], cryotherapy, intralesional rituximab [23], topical 0.1% tacrolimus ointment [24] and topical photodynamic therapy [25, 26, 27]. Subcutaneous IFN-α [28, 29] and thalidomide [16, 30] have also shown benefit in generalized disease.

Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate

Definition

This is a chronic, benign, inflammatory condition, usually affecting photo-exposed skin. First described in 1953 by Jessner and Kanof [1], it remains poorly understood. Recent literature suggests that it has many similarities with LE tumidus, both clinically and histologically [2, 3, 4].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The incidence and prevalence are not known but it is uncommon.

Age

It mainly occurs in adults below the age of 50 years. It may occur in children [5] and familial cases have also been reported [6, 7].

Sex

There are conflicting reports of male and female predominance.

Ethnicity

There is no known racial predilection.

Associated diseases

Recent literature suggests that it may be a variant of LE.

Pathophysiology

It is not well understood. Its relationship to LE and other benign cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates is not clear.

Pathology [2, 8, 9, 10]

The epidermis is usually normal with no atrophy, follicular plugging or basement membrane thickening. There is a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. It may also be perifollicular and extend to the subcutis (Figure 135.11). The infiltrate contains small mature lymphocytes, with occasional large lymphoid cells, plasmacytoid and plasma cells. Copious dermal mucin is not seen. Immunohistochemistry confirms a mixed lymphocytic infiltrate with a dominant population of CD8+ cells. Direct immunofluorescence is negative. Molecular analysis of both T-cell and B-cell populations are polyclonal on molecular analysis.

Figure 135.11 H&E-stained section of skin from a patient with Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate showing a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Original magnification 40×.

Clinical features

Presentation

It presents with asymptomatic, non-scaly, erythematous papules and plaques, mainly affecting the face, neck and upper chest. There may be one, a few or numerous lesions and central clearing of lesions may occur, giving them an annular appearance (Figure 135.12). There is no atrophy or follicular plugging. There may or may not be a history of onset following sun exposure. The lesions may last months or years and often resolve spontaneously but can recur, either at the same or a different site.

Figure 135.12 Non-scaly erythematous plaques on the face of young woman with Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate.

Differential diagnosis

Polymorphic light eruption can usually be excluded from the history and short duration of lesions. LE and lymphocytoma cutis can be excluded histologically.

Disease course and prognosis

Prognosis is good as it is benign in nature and may resolve spontaneously; there is no increase in mortality.

Investigations

A skin biopsy is needed for histology, direct immunofluorescence and molecular gene rearrangement studies. Serology testing for systemic lupus erythematosus should be considered, including antinuclear antibodies, ESR, anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, FBC and urinalysis. Phototesting may be useful in those patients with a history of photosensitivity.

Management

Treatments are often unsatisfactory and based on case reports. It may require no treatment if it is asymptomatic. Cosmetic camouflage, excision of small lesions, photoprotection and topical [2] or intralesional [5] steroids may provide benefit. Hydroxychloroquine [2], systemic steroids and cryotherapy have been used with success. There are reports of benefit with methotrexate [11], retinoids [12] and oral auranofin [13]. There is one randomized double blind cross-over study comparing thalidomide with placebo in 27 patients; 59% remained in complete remission 1 month after stopping treatment [14]. Clearing of lesions has also been reported with pulsed dye laser [15] and methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy [16].

References

Pseudolymphoma

- Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:877–905.

- Halevy S, Sandbank M. Transformation of lymphocytoma cutis into malignant lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1987;67:172–5.

- Nakayama H, Mihara M, Shimao S. Malignant transformation of lymphadenosis benigna cutis. J Dermatol 1987;14:266–9.

- Kluger N, Vermeulen C, Moguelet P, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma) in tattoos: a case series of seven patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:208–13.

- Rijlaarsdam J, Bruynzeel D, Vos W, et al. Immunohistochemical studies of lymphadenosis benigna cutis occurring in a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol 1998;10:518–23.

- Maubec E, Pinquier L, Viguier M, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:623–9.

- Kim K, Lee M, Choi J, et al. CD30-positive T-cell rich pseudolymphoma induced by gold acupuncture. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:882–4.

- Furness PN, Goodfield MJ, Maclennan KA, et al. Severe cutaneous reactions to captopril and enalapril. J Clin Pathol 1986;39:902–7.

- Henderson CA, Shamy HK. Atenolol induced pseudolymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 1990;115:119–20.

- Kaurdan SH, Scheffer E, Vermeer BJ. Drug-induced pseudolymphomatous reactions. Br J Dermatol 1988;188:545–52.

- Souteyrand P, Duncan M. Drug-induced mycosis fungoides-like lesions. Curr Prob Dermatol 1990;19:176–82.

- Nathan DL, Belsito DV. Carbamazepine induced pseudolymphoma with CD30 positive cells. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:806–9.

- Ecker RI, Winkelmann RD. Lymphomatoid contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 1981;7:84–93.

- Martinez-Moran C, Sanz Munoz C, Morales-Callaghan AM, et al. Lymphomatoid contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2009;60:53–5.

- Kawada A, Mori S, Hayashi T. Lymphadenosis benigna cutis: pseudomalignant form and its imprint smear cytology. Dermatologica 1970;141:339–47.

- Geerts ML, Kaiserling E. A morphologic study of lymphadenosis benigna cutis. Dermatologica 1985;170:121–7.

- Shelley WB, Wood MG, Wilson JF, et al. Premalignant lymphoid hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:500–3.

- Evans HL, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Differential diagnosis of malignant and benign cutaneous infiltrates. Cancer 1979;44:699–717.

- Burg G, Braun-Falco O, Schmoeckel C. Differentiation between pseudolymphomas and malignant B-cell lymphomas of the skin. In: Goos M, Christophers E, eds. Lymphoproliferative Diseases of the Skin. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1982:101–34.

- Van der Putte SCJ, Toonstra J, Felten PC, van Vloten WA. Solitary nonepidermotropic T-cell pseudolymphoma of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;14:444–53.

- Bernstein H, Shupack J, Ackerman AB. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma resulting from antigen injections. Arch Dermatol 1974;110:756–7.

- Chimenti S, Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, et al. The role of MT2 and anti bcl-2 protein antibodies in the differentiation of benign from malignant cutaneous infiltrates of B lymphocytes with germinal centre formation. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:319–22.

- Wood G, Ngan B, Tung R, et al. Clonal arrangements of immunoglobulin genes and progression to B-cell lymphoma in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 1989;35:969–78.

- Bignon YJ, Souteyrand P. Genotyping of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol 1990;19:114–23.

- Zelickson BD, Peters MS, Muller SA, et al. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25:787–96.

- Weinberg J, Rook A, Lessin S. Molecular diagnosis of lymphocytic infiltrates of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:1491–500.

- Wood GS. Analysis of clonality in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and associated diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;941:26–30.

- Walton S, Bottomley WW, Wyatt EH, Bury HPR. Pseudo T-cell lymphoma due to scabies in a patient with Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol 1991;124:277–8.

- Castelli E, Caputo V, Morello V, Tomasino RM. Local reactions to tick bites. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:241–8.

- Hermes B, Haas N, Grabbe J, Cznarnetzki B. Foreign body granuloma and IgE-pseudolymphoma after multiple bee stings. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:780–4.

- Garbe C, Stein H, Dienemann D, Orfanos C. Borrelia burdorferi-associated cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:584–90.

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Mulleegger R, Chott A, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Borrelia burgdorfori-associated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathological, immunophenotypic and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;31:232–40.

- Recalcati S, Vezzoli P, Girgenti V, Venegoni L, Veraldi S, Berti E. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia associated with Leishmania panamensis infection. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:418–19.

- Moreno-Ramírez D, García-Escudero A, Ríos-Martín JJ, Herrera-Saval A, Camacho F. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma in association with molluscum contagiosum in an elderly patient. J Cutan Pathol 2003;30:473–5.

- Roo E, Villegas C, Lopez-Bran E, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:661–3.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, Ortiz S, Schaller J, Rohwedder A. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:161–8.

- Rijlaarsdam JU, Scheffer E, Meier CJLM, Willemze R. Cutaneous pseudo T-cell lymphomas. Cancer 1992;69:717–24.

- Beltraminelli H, Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous CD4+ small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a cutaneous nodular proliferation of pleomorphic T lymphocytes of undetermined significance? A study of 136 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2009;31:317–22.

- Ally MS, Prasad Hunasehally RY, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. Evaluation of follicular T-helper cells in primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma and dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol 2013;40:1006–13.

- Hammer E, Sangueza O, Suwanjindar P, White CR, Braziel RM. Immunophenotypic and genotypic analysis in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:426-433.

Pityriasis lichenoides

- Tsuji T, Kasamatsu M, Yokota M, et al. Mucha–Habermann disease and its febrile ulceronecrotic variant. Cutis 1996;58:123–31.

- Degos R, Duperrat B, Daniel F. Le parapsoriasis ulcero-necrotique hyperthermique. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr 1966;93:481–96.

- Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:557–72.

- Khachemoune A, Blyumin ML. Pityriasis lichenoides. Pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007;8:29–36.

- Patel DG, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides. Cutis 2000;65:17–23.

- Ersoy-Evans S, Greco F, Mancini AJ, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides in childhood. A retrospective review of 124 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:205–10.

- Longley J, Demar L, Feinstein RP, et al. Clinical and histological features of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in children. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:1335–9.

- Shieh S, Mikkola DL, Wood GS. Differentiation and clonality of lesional lymphocytes in pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:305–8.

- Magro C, Crowson A, Morrison C, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica: stratification by molecular and phenotypic profile. Hum Pathol 2007;38:479–90.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:1483–6.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1063–7.

- Helmbold P, Gaisbauer G, Fielder E, et al. Self-limited variant of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease with polyclonal T-cell receptor rearrangement. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:1113–14.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:1014–17.

- Kempf W, Kutzner H, Kettelhack N, et al. Paraneoplastic pityriasis lichenoides in cutaneous lymphoma: case report and review of the literature on paraneoplastic reactions of the skin in lymphoma and leukaemia. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1327–31.

- Benmaman O, Sanchez JL. Comparative clinicopathological study on pityriasis lichenoides chronica and small plaque parapsoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol 1988;10:189–96.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma. Report of the 2011 Society for Haematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology Workshop. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:536–51.

- Jang KA, Choi JC, Choi JH. Expression of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen and TIA-1 by lymphocytes in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and lymphomatoid papulosis: immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28:453–9.

- Dupont C. Pityriasis lichenoides in a family. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:388–9.

- Rongioletti F, Delmonte S, Rebora A. Pityriasis lichenoides and acquired toxoplasmosis. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:372–4.

- Nassef NE, Hammam MA. The relation between toxoplasmosis and pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 1997;27(1):93–9.

- Tsai KS, Hsieh HJ, Chow KC, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann's disease. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:694–8.

- Nanda A, Alshalfan F, Al-Otaibi M, Al-Sabah H, Rajy JM. Febrile ulcernecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta fulminans) associated with parvovirus infection. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:503–6.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Palmedo G, Fraitag S, Schaerer L, Kutzner H. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta with numerous CD30 (+) cells: a variant mimicking lymphomatoid papulosis and other cutaneous lymphomas. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1021–9.

- Labarthe MP, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Ulcers of the tongue, pityriasis lichenoides and primary parvovirus B19 infection. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1996;123:735–8.

- Auster BI, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease with interstitial pneumonitis. J Cutan Pathol 1979;6:66–76.

- Klein PA, Jones EC, Nelson JL, Clark RA. Infectious causes of pityriasis lichenoides: a case of fulminant infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:S151–3.

- Edwards BL, Bonagura VR, Valacer DJ, et al. Mucha–Habermann's disease and arthritis: possible association with reactivated Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Rheumatol 1989;16:387–9.

- Smith JJ, Oliver GF. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease associated with herpes simplex virus type 2. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(1):149–52.

- Cho E, Jun HJ, Cho SH, Lee JD. Varicella-zoster virus as a possible cause of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Pediatr Dermatol 2014;31:259–60.

- Hervas JA, Martin-Santiago A, Hervas D, Gomez C, Duenas J, Reina J. Varicella precipitating febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:216-17.

- Smith KJ, Nelson A, Skelton H, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in HIV-1+ patients: a marker of early stage disease. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:104–9.

- Gunatheesan S, Ferguson J, Moosa Y. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a rare association with measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. Australas J Dermatol 2012;53:76–8.

- Zhang LX, Liang Y, Liu Y, Ma L. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease with pulmonary involvement. Pediatr Dermatol 2010;27:290–3.

- English JC, Collins M, Bryant-Bruce C. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection. Int J Dermatol 1995;34:642–4.

- Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder. Evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;31:531–8.

- Takahashi K, Atsumi M. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica resolving after tonsillectomy. Br J Dermatol 1993;129:353–4.

- Romani J, Puig L, Fernandez-Figueras MT, de Moragas JM. Pityriasis lichenoides in children: clinicopathologic review of 22 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;15:1–6.

- Hapa A, Ersoy-Evans S, Karaduman A. Childhood pityriasis lichenoides and oral erythromycin. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:719–24.

- Piamphongsant T. Tetracycline for the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol 1974;911:319–22.

- Zechini B, Teggi A, Antonelli M, et al. A case report of pityriasis lichenoides in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Infect 2005;51:e23–5.

- Kim JE, Yun WJ, Mun SK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica: comparison of lesional T-cell subsets and investigation of viral associations. J Cutan Pathol 2011;38:649–56.

- Gelmetti C, Rigioni C, Alessi E, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides in children: a long-term follow-up of 89 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23:473–8.

- Brazzini B, Ghersetich I, Urso C, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta during pregnancy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001;15:458–60.

- Puddu P, Cianchini G, Colonna L, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann's disease with fatal outcome. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:691–4.

- De Cuyper C, Hindryckx P, Deroo N. Febrile ulceronecrotic pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Dermatology 1994;189(Suppl. 2):50–3.

- Kossard S. Acral pityriasis lichenoides. Australas J Dermatol 2002;43:68–71.

- Chung HG, Kim SC. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica with acral distribution mimicking palmoplantar syphilid. Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:239.

- Halbesleben JJ, Swick BL. Localized acral pityriasis lichenoides chronica: report of a case. J Dermatol 2011;38:832–3.

- Cliff S, Cook MG, Ostlere LS, Mortimer PS. Segmental pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996;21:464–5.

- Wahie S, Hiscutt E, Natarajan S, Taylor A. Pityriasis lichenoides: the differences between children and adults. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:941–5.

- Simon D, Boudny C, Nievergelt H, Simon H-U, Braathen LR. Successful treatment of pityriasis lichenoides with topical tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:1033–5.

- Mallipeddi R, Evans AV. Refractory pityriasis lichenoides chronica successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28:456–8.

- Pavlotsky F, Baum S, Barzilai A, Shpiro D, Trau H. UVB therapy of pityriasis lichenoides – our experience with 29 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20(5):542–7.

- Aydogan K, Saricaoglu H, Turan H. Narrowband UVB (311 nm, TL01) phototherapy for pityriasis lichenoides. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2008;24(3):128–33.

- Farnaghi F, Serafi H, Ehsani AH, Agdari ME, Noormohammadpour P. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of narrow band UVB vs PUVA in patients with pityriasis lichenoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:913–16.

- Pinton PC, Capazzera R, Zane C, De Panfilis G. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 therapy for pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:410–14.

- Powell FC, Muller SA. Psoralens and ultraviolet A therapy of pityriasis lichenoides. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:59–64.

- Panse I, Bourrat E, Rybojad M, Morel P. Photochemotherpay for pityriasis lichenoides; 3 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2004;131:201–3.

- Piamphongsant T. Tetracycline for the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol 1974;911:319–22.

- Lynch PJ, Saied NK. Methotrexate treatment of pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis. Cutis 1979;23:634–6.

- Marenco F, Fava P, Fierro MT, Quaglino P, Bernengo MG. High-dose immunoglobulins and extracorporeal photochemotherapy in the treatment of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. Dermatol Ther 2010;23:419–22.

- Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:794–9.

- Nikkels AF, Gillard P, Pierard GE. Etanercept in therapy multiresistant overlapping pityriasis lichenoides. J Drugs Dermatol 2008;7:990–2.

- Meziane L, Caudron A, Dhaille F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: treatment with infliximab and intravenous immunoglobulins and review of the literature. Dermatology 2012;225:344–8.

- Lopez-Ferrer A, Puig L, Moreno G, Camps-Fresneda A, Palou J, Alomar A. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica induced by infliximab, with response to methotrexate. Eur J Dermatol 2010;20:511–12.

- Newell EL, Jain S, Stephens C, Martland G. Infliximab-induced pityriasis lichenoides chronica in a patient with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:230–1.

- Said BB, Kanitakis J, Graber I, Nicolas JF, Saurin JC, Berard F. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica induced by adalimumab therapy for Crohn's disease: report of 2 cases successfully treated with methotrexate. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:912–13.

Parapsoriasis

- Ackerman AB, Schiff TA. If small plaque parapsoriasis is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, even an abortive one, it must be mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol 1996;132:562–6.

- Vakeva L, Sama S, Vaalati A, Pukkala E, Kariniemi AL, Ranki A. A retrospective study of the probability of the evolution of parapsoriasis en plaques into mycosis fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol 2005;85:318–23.

- Klemke CD, Dippel E, Dembinski A, et al. Clonal T cell receptor gamma-chain rearrangement by PCR-based GeneScan analysis in the skin and blood of patients with parapsoriasis and early-stage mycosis fungoides. J Pathol 2002;197:348–54.

- Burg G, Dummer R. Small plaque parapsoriasis is an abortive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and is not mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:336–8.

- Haeffner AC, Smoller BR, Zepter K, Wood GS. Differentiation and clonality of lesional lymphocytes in small plaque parapsoriasis. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:321–8.

- Muche JM, Lukowsky A, Heim J, Friedrich M, Audring H, Sterry W. Demonstration of frequent occurrence of clonal T cells in the peripheral blood but not in the skin of patients with small plaque parapsoriasis. Blood 1999; 94:1409–17.

- Posnett DN, Sinha R, Kabak S, Russo C. Clonal populations of T cells in normal elderly humans: the T cell equivalent to “benign monoclonal gammapathy”. J Exp Med 1994;179:609–18.

- Delfau-Larue MH, Laroche L, Wechsler J, et al. Diagnostic value of dominant T-cell clones in peripheral blood in 363 patients presenting consecutively with a clinical suspicion of cutaneous lymphoma. Blood 2000; 96:2987–92.

- Belousova IE, Vanecek T Samtsov AV, Michal M, Kasakov DV. A patient with clinicopathological features of small plaque parapsoriasis presenting later with plaque-stage mycosis fungoides: report of a case and comparative retrospective study of 27 cases of ‘nonprogrssive’ small plaque parapsoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:474–82.

- Powell FC, Spiegel GT, Muller SA. Treatment of parapsoriasis and mycosis fungoides: the role of psoralen and long-wave ultraviolet light A (PUVA). Mayo Clin Proc 1984; 59: 538–46.

- Hofer A, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P. Narrow-band UVB therapy for small plaque parapsoriasis and early stage mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:1377–80.

- Herzinger T, Degitz K, Plwig G, Rocken M. Treatment of small plaque parapsoriasis with narrow-band (311 mm) ultraviolet B: a retrospective study. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:379–81.

- Aydogan K, Karadogan SK, Tunali S, Adim SB, Ozcelik T. Narrowband UVB phototherapy for small plaque parapsoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:573–7.

- Lindahl LM, Fenger-Gron M, Iversen L. Topical nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides or parapsoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:163–8.

- Vakeva L, Sama S, Vaalati A, Pukkala E, Kariniemi AL, Ranki A. A retrospective study of the probability of the evolution of parapsoriasis en plaques into mycosis fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol 2005;85:318–23.

- Kempf W, Dummer R, Burg G. Approach to lymphoproliferative conditions of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol 1999;111(Suppl. 1):S84–93.

- Liu V, McKee PH. Cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Adv Anat Pathol 2002;9:79–100.

- Simon M, Flaig MJ, Kind P, et al. Large plaque parapsoriasis: clinical and genotypic considerations. J Cutan Pathol 2000;27:57–60.

- Lambert WC, Everett MA. The nosology of parapsoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;5:373–95.

- Rosenbaum MM, Roenigk HH, Jr, Caro WA, Esker A. Photochemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and parapsoriasis en plaque. Long term follow-up in forty-three patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;13:613–22.

- Arai R, Horiguchi Y. Retrospective study of 24 patients with large or small plaque parapsoriasis treated with ultraviolet B therapy. J Dermatol 2012;39:674–6.

- Lindahl LM, Fenger-Gron M, Iversen L. Topical nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides or parapsoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:163–8.

- Gebert S, Raulin C, Ockenfels HM, Gundogan C, Greve B. Excimer-laser (308 nm) treatment of large plaque parapsoriasis and long-term follow-up. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:198–9.

Lymphocytoma cutis

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Mullegger R, Chott A, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;31:232–40.

- Strle F, Pleterski-Rigler D, Stanek G, Pejovnik-Pustinek A, Ruzic E, Cimperman J. Solitary borrelial lymphocytoma: report of 36 cases. Infection 1992;20;201–6.

- Baldassano MF, Bailey EM, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Duncan LM. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma: comparison of morphologic and immunophenotypic features. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:88–96.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma. Report of the 2011 Society for Haematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology Workshop. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:536–51.

- Arai E, Shimizu M, Hirose T. A review of 55 cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: reassessment of the histopathologic findings leading to reclassification of 4 lesions as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and 19 as pseudolymphomatous folliculitis. Hum Pathol 2005;36:505–11.

- Bergman R, Khamaysi K, Khamaysi Z, Ben Arie Y. A study of histologic and immunophenotypical staining patterns in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:112–24.

- Flaig MJ, Rupec RA. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma in association with Leishmania donovani. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:1042–3.

- Moreira E, Lisboa C, Azevedo F, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma in a patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:1112–14.

- Cerroni L, Borroni RG, Massone C, Chott A, Kerl H. Cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma at the site of vaccination. Am J Dermatopathol 2007;29:538–42.

- Lanzafame S, Micali G. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma) secondary to vaccination. Pathologica 1993;85:555–61.

- Watanabe R, Nanko H, Fukuda S. Lymphocytoma cutis to pierced earrings. J Cutan Pathol 2006;33(Suppl. 2):16–19.

- Choi Y, Kim S-C. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by Hirudo medicinalis therapy. J Dermatol 2012;39:195–7.

- Frain-Bell W, Magnus IA. A study of the photosensitivity factor in cutaneous lymphocytoma. Br J Dermatol 1971;84:25–31.

- Bafverstedt B. Unusual forms of lymphadenosis benigna cutis (LABC). Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1962;42:3–10.

- Moulonguet I, Ghnassia M, Molina T, Fraitag S. Miliarial-type perifollicular B-cell pseudolymphoma (lymphocytoma cutis): a misleading eruption in two women. J Cutan Pathol 2012;39:1016–21.

- Pham-Ledard A, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot-Barry M. Disseminated cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia of 12 years' duration triggered by vaccination. Dermatology 2010;220:176–9.

- Wood GS, Ngan BY, Tung R, Hoffman TE, Abel EA, Hoppe RT. Clonal rearrangements and progression to B cell lymphoma in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 1989;135:13–19.

- Hammer E, Sangueza O, Suwanjindar P, White CR, Braziel R. Immunophenotypic and genotypic analysis in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:426–33.

- Stoll DM. Treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma with hydroxychloroquine. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983;8:696–9.

- Olson LE, Wilson JF, Cox JD. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: results of radiation therapy. Radiology 1985;155:507–9.

- Aydogan K, Karadogan SK, Adim SB, Tunali S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis successfully treated with intralesional interferon-alpha-2A. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:1030–2.

- Tomar S, Stoll HL, Grassi MA, Cheney R. Treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma with interferon alfa-2b. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:172–4.

- Martin SJ, Duvic M. Treatment of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia with the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2011;11:286–8.

- El-Dars LD, Statham BN, Blackford S, Williams N. Lymphocytoma cutis treated with topical tacrolimus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:305–7.

- Takeda H, Kaneko T, Harada K, Matsuzaki Y, Nakano H, Hanada K. Successful treatment of lymphadenosis benigna cutis with topical photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid. Dermatology 2005;211:264–6.

- Mikasa K, Watanabe D, Kondo C, Tamada Y, Matsumoto Y. Topical 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy for the treatment of a patient with cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:911–12.

- O'Neill J, Fien S, Zeitouni NC. ALA-PDT for the treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma: a case report. J Drugs Dermatol 2010;9:688–9.

- Hervonene K, Lehtinen T, Vaalasti A. Spiegler-Fendt type lymphocytoma cutis: a case report of two patients successfully treated with interferon alpha-2b. Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:241–2.

- Singletary HL, Selim MA, Olsen E. Subcutaneous interferon alfa for the treatment of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:572–4.

- Benchikhi H, Bodemer C, Fraitag S, et al. Treatment of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia with thalidomide: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:1005–7.

Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate

- Jessner M, Kanof NB. Lymphocytic infiltration of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1953;68:447–9.

- Toonstra J, Wildschut A, Boer J, et al. Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin: a clinical study of 100 patients. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:1525–30.

- Lipsker D, Mitschler A, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Could Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin be a dermal variant of lupus erythematosus? An analysis of 210 cases. Dermatology 2006;213:15–22.

- Rémy-Leroux V, Léonard F, Lambert D, et al. Comparison of histopathologic-clinical characteristics of Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin and lupus erythematosus tumidus: multicenter study of 46 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:217–23.

- Higgins CR, Wakeel RA, Cerio R. Childhood Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin. Br J Dermatol 1994;131:99–101.

- Dippel E, Poenitz N, Klemke CD, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S. Familial lymphocytic infiltration of the skin: histochemical and molecular analysis in three brothers. Dermatology 2002;204:12–16.

- O'Toole EA, Powell F, Barnes L. Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate and probable discoid lupus erythematosus occurring separately in two sisters. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:90–3.

- Calnan CD. Lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (Jessner): cutaneous Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol 1957;69:169–73.

- Willemze R, Dijkstra A, Meijer CJ. Lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (Jessner): a T-cell lymphoproliferative disease. Br J Dermatol 1984;110(5):523–9.

- Rijlaarsdam JU, Nieboer C, de Vries E, Willemze R. Characterization of the dermal infiltrates in Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin, polymorphous light eruption and cutaneous lupus erythematosus: differential diagnostic and pathogenetic aspects. J Cutan Pathol 1990;17:2–8.

- Laurinaviciene R, Clemmensen O, Bygum A. Successful treatment of Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin with methotrexate. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:542–3.

- Morgan J, Adams J. Satisfactory resolution of Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin following treatment with etretinate. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:570.

- Farrell AM, McGregor JM, Staughton RC, Bunker CB. Jessner's lymphocytic infiltrate treated with auranofin. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:500.

- Guillaume JC, Moulin G, Dieng, MT, et al. Crossover study of thalidomide vs placebo in Jessner's lymphocytic infiltration of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:1032–5.

- Borges da Costa J, Boixeda P, Moreno C. Pulsed-dye laser treatment of Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:595–6.

- Park KY, Kim HK, Li K, et al. Photodynamic therapy: new treatment for refractory lymphocytic infiltration of the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012;3:235–7.

Pseudolymphoma

- Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:877–905.

- Halevy S, Sandbank M. Transformation of lymphocytoma cutis into malignant lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1987;67:172–5.

- Nakayama H, Mihara M, Shimao S. Malignant transformation of lymphadenosis benigna cutis. J Dermatol 1987;14:266–9.

- Kluger N, Vermeulen C, Moguelet P, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma) in tattoos: a case series of seven patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:208–13.

- Rijlaarsdam J, Bruynzeel D, Vos W, et al. Immunohistochemical studies of lymphadenosis benigna cutis occurring in a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol 1998;10:518–23.

- Maubec E, Pinquier L, Viguier M, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:623–9.

- Kim K, Lee M, Choi J, et al. CD30-positive T-cell rich pseudolymphoma induced by gold acupuncture. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:882–4.

- Furness PN, Goodfield MJ, Maclennan KA, et al. Severe cutaneous reactions to captopril and enalapril. J Clin Pathol 1986;39:902–7.

- Henderson CA, Shamy HK. Atenolol induced pseudolymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 1990;115:119–20.

- Kaurdan SH, Scheffer E, Vermeer BJ. Drug-induced pseudolymphomatous reactions. Br J Dermatol 1988;188:545–52.

- Souteyrand P, Duncan M. Drug-induced mycosis fungoides-like lesions. Curr Prob Dermatol 1990;19:176–82.

- Nathan DL, Belsito DV. Carbamazepine induced pseudolymphoma with CD30 positive cells. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:806–9.

- Ecker RI, Winkelmann RD. Lymphomatoid contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 1981;7:84–93.

- Martinez-Moran C, Sanz Munoz C, Morales-Callaghan AM, et al. Lymphomatoid contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2009;60:53–5.

- Kawada A, Mori S, Hayashi T. Lymphadenosis benigna cutis: pseudomalignant form and its imprint smear cytology. Dermatologica 1970;141:339–47.

- Geerts ML, Kaiserling E. A morphologic study of lymphadenosis benigna cutis. Dermatologica 1985;170:121–7.

- Shelley WB, Wood MG, Wilson JF, et al. Premalignant lymphoid hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:500–3.

- Evans HL, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Differential diagnosis of malignant and benign cutaneous infiltrates. Cancer 1979;44:699–717.

- Burg G, Braun-Falco O, Schmoeckel C. Differentiation between pseudolymphomas and malignant B-cell lymphomas of the skin. In: Goos M, Christophers E, eds. Lymphoproliferative Diseases of the Skin. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1982:101–34.

- Van der Putte SCJ, Toonstra J, Felten PC, van Vloten WA. Solitary nonepidermotropic T-cell pseudolymphoma of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;14:444–53.

- Bernstein H, Shupack J, Ackerman AB. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma resulting from antigen injections. Arch Dermatol 1974;110:756–7.

- Chimenti S, Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, et al. The role of MT2 and anti bcl-2 protein antibodies in the differentiation of benign from malignant cutaneous infiltrates of B lymphocytes with germinal centre formation. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:319–22.

- Wood G, Ngan B, Tung R, et al. Clonal arrangements of immunoglobulin genes and progression to B-cell lymphoma in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 1989;35:969–78.

- Bignon YJ, Souteyrand P. Genotyping of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol 1990;19:114–23.

- Zelickson BD, Peters MS, Muller SA, et al. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25:787–96.

- Weinberg J, Rook A, Lessin S. Molecular diagnosis of lymphocytic infiltrates of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:1491–500.

- Wood GS. Analysis of clonality in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and associated diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;941:26–30.

- Walton S, Bottomley WW, Wyatt EH, Bury HPR. Pseudo T-cell lymphoma due to scabies in a patient with Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol 1991;124:277–8.

- Castelli E, Caputo V, Morello V, Tomasino RM. Local reactions to tick bites. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:241–8.

- Hermes B, Haas N, Grabbe J, Cznarnetzki B. Foreign body granuloma and IgE-pseudolymphoma after multiple bee stings. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:780–4.

- Garbe C, Stein H, Dienemann D, Orfanos C. Borrelia burdorferi-associated cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:584–90.

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Mulleegger R, Chott A, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Borrelia burgdorfori-associated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathological, immunophenotypic and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;31:232–40.

- Recalcati S, Vezzoli P, Girgenti V, Venegoni L, Veraldi S, Berti E. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia associated with Leishmania panamensis infection. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:418–19.

- Moreno-Ramírez D, García-Escudero A, Ríos-Martín JJ, Herrera-Saval A, Camacho F. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma in association with molluscum contagiosum in an elderly patient. J Cutan Pathol 2003;30:473–5.

- Roo E, Villegas C, Lopez-Bran E, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:661–3.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, Ortiz S, Schaller J, Rohwedder A. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:161–8.

- Rijlaarsdam JU, Scheffer E, Meier CJLM, Willemze R. Cutaneous pseudo T-cell lymphomas. Cancer 1992;69:717–24.

- Beltraminelli H, Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous CD4+ small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a cutaneous nodular proliferation of pleomorphic T lymphocytes of undetermined significance? A study of 136 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2009;31:317–22.

- Ally MS, Prasad Hunasehally RY, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. Evaluation of follicular T-helper cells in primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma and dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol 2013;40:1006–13.

- Hammer E, Sangueza O, Suwanjindar P, White CR, Braziel RM. Immunophenotypic and genotypic analysis in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:426-433.

Pityriasis lichenoides

- Tsuji T, Kasamatsu M, Yokota M, et al. Mucha–Habermann disease and its febrile ulceronecrotic variant. Cutis 1996;58:123–31.

- Degos R, Duperrat B, Daniel F. Le parapsoriasis ulcero-necrotique hyperthermique. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr 1966;93:481–96.

- Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:557–72.

- Khachemoune A, Blyumin ML. Pityriasis lichenoides. Pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007;8:29–36.

- Patel DG, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides. Cutis 2000;65:17–23.

- Ersoy-Evans S, Greco F, Mancini AJ, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides in childhood. A retrospective review of 124 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:205–10.

- Longley J, Demar L, Feinstein RP, et al. Clinical and histological features of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in children. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:1335–9.

- Shieh S, Mikkola DL, Wood GS. Differentiation and clonality of lesional lymphocytes in pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:305–8.

- Magro C, Crowson A, Morrison C, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica: stratification by molecular and phenotypic profile. Hum Pathol 2007;38:479–90.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:1483–6.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1063–7.

- Helmbold P, Gaisbauer G, Fielder E, et al. Self-limited variant of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease with polyclonal T-cell receptor rearrangement. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:1113–14.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:1014–17.

- Kempf W, Kutzner H, Kettelhack N, et al. Paraneoplastic pityriasis lichenoides in cutaneous lymphoma: case report and review of the literature on paraneoplastic reactions of the skin in lymphoma and leukaemia. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1327–31.

- Benmaman O, Sanchez JL. Comparative clinicopathological study on pityriasis lichenoides chronica and small plaque parapsoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol 1988;10:189–96.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma. Report of the 2011 Society for Haematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology Workshop. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:536–51.

- Jang KA, Choi JC, Choi JH. Expression of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen and TIA-1 by lymphocytes in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and lymphomatoid papulosis: immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28:453–9.

- Dupont C. Pityriasis lichenoides in a family. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:388–9.

- Rongioletti F, Delmonte S, Rebora A. Pityriasis lichenoides and acquired toxoplasmosis. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:372–4.

- Nassef NE, Hammam MA. The relation between toxoplasmosis and pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 1997;27(1):93–9.

- Tsai KS, Hsieh HJ, Chow KC, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann's disease. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:694–8.

- Nanda A, Alshalfan F, Al-Otaibi M, Al-Sabah H, Rajy JM. Febrile ulcernecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta fulminans) associated with parvovirus infection. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:503–6.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Palmedo G, Fraitag S, Schaerer L, Kutzner H. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta with numerous CD30 (+) cells: a variant mimicking lymphomatoid papulosis and other cutaneous lymphomas. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1021–9.

- Labarthe MP, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Ulcers of the tongue, pityriasis lichenoides and primary parvovirus B19 infection. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1996;123:735–8.

- Auster BI, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease with interstitial pneumonitis. J Cutan Pathol 1979;6:66–76.

- Klein PA, Jones EC, Nelson JL, Clark RA. Infectious causes of pityriasis lichenoides: a case of fulminant infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:S151–3.

- Edwards BL, Bonagura VR, Valacer DJ, et al. Mucha–Habermann's disease and arthritis: possible association with reactivated Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Rheumatol 1989;16:387–9.

- Smith JJ, Oliver GF. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease associated with herpes simplex virus type 2. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(1):149–52.

- Cho E, Jun HJ, Cho SH, Lee JD. Varicella-zoster virus as a possible cause of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Pediatr Dermatol 2014;31:259–60.

- Hervas JA, Martin-Santiago A, Hervas D, Gomez C, Duenas J, Reina J. Varicella precipitating febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:216-17.

- Smith KJ, Nelson A, Skelton H, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in HIV-1+ patients: a marker of early stage disease. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:104–9.