CHAPTER 137

Soft-tissue Tumours and Tumour-like Conditions

Eduardo Calonje

St John's Institute of Dermatology, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Introduction and general description

For many clinical dermatologists, soft-tissue tumours arising in the dermis, subcutis or deeper soft tissues are a confusing group of lesions. This is probably partly explained by the facts that there is a very long list of soft-tissue tumours, and that a large majority of these can arise in the skin or affect it secondarily. Most of these tumours have no characteristic clinical appearance, and present as non-specific, dermal or deep-seated nodules. However, it is necessary for all clinical dermatologists to have an understanding of the range of tumours that may arise in the dermis, and also of the likely biological behaviour of individual lesions. Although cutaneous malignant soft-tissue tumours are rare, many benign lesions may be histologically confused with a malignancy. Furthermore, there is a group of soft-tissue tumours that have low-grade malignant potential (intermediate malignancy) with frequent local recurrences but little or no potential for metastatic spread (e.g. dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)). These tumours may cause important morbidity, and their recognition is therefore essential for the planning of treatment and follow-up. Recognizing a wide range of soft-tissue tumours is also important as a number of these lesions—particularly when multiple—may be markers of genetic syndromes (e.g. multiple neurofibromas and plexiform neurofibroma in neurofibromatosis type 1).

A broad division can be made between tumours according to the morphological lines of differentiation. The latter include fibroblastic, myofibroblastic, neural, vascular, muscular and adipocytic types. In a number of tumours, the line of differentiation is not clear, as a normal cell of origin cannot be identified (e.g. epithelioid sarcoma). In a still larger group of tumours, their origin is descriptively ascribed to fibrohistiocytic cells, but with mounting evidence that many of these lesions have fibroblast and/or myofibroblastic differentiation and almost none display true histiocytic differentiation. The list of tumours discussed in this chapter is not all inclusive. For a full account of the very wide range of these tumours, the reader is referred to the standard major works in this field [1, 2]. True histiocytic tumours (see Chapter 136), and keloids and hypertrophic scars (see Chapter 96) and metastatic malignant tumours (see Chapter 147) are covered elsewhere.

The most useful biological triage is into totally benign lesions; lesions that may recur locally but never or almost never metastasize; and those that are truly malignant and may metastasize. The great majority of dermal or superficial soft-tissue tumours come into the first two categories, whilst truly malignant soft-tissue tumours much more frequently arise below the deep fascia. In the case of these rare malignant tumours, there is a relationship between bulk and prognosis, smaller lesions carrying a better prognosis. More superficially situated lesions tend to carry a better prognosis than those deeply situated. Mitoses (particularly abnormal mitotic figures) and necrosis both tend to be associated with malignant rather than benign lesions.

The usual clinical presentation of many of the tumours described in this chapter is of a non-specific lump or nodule. An incisional biopsy should be arranged, and it must be adequately deep so that the nature of the lesion at its deepest margin can be determined. Once the pathologist has established the nature of the tumour, appropriate definitive surgery can be planned. Prior consultation with the pathologist is strongly recommended, as samples may be needed for cytogenetics, electron microscopy or immunohistochemistry. All of these may be helpful in arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

FIBROUS AND MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMOURS

Fibrous papule of the face [1]

Definition and nomenclature

A small facial papule with a distinctive fibrovascular component on histological examination.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Lesions are very common [2, 3, 4].

Age

Most patients are middle-aged adults.

Sex

Both sexes are equally affected.

Pathophysiology

It has been suggested that the condition may be a variant of a melanocytic naevus [2, 4], but others disagree [3]. S100 protein, is never present in lesional cells giving further support to the theory of a non-melanocytic proliferation.

Pathology [2, 3, 4]

The epidermis appears normal, although there may be an increased number of clear cells overlying the lesion. In the dermis, there is increased collagen with a hyalinized appearance and scattered, somewhat dilated, vascular channels (Figure 137.1). In the background, there is increased cellularity with mono- and multinucleated cells with a histiocyte-like appearance. In some lesions, epithelioid or clear cells and exceptionally granular cells may predominate [5, 6, 7, 8]. There are prominent dilated capillaries.

Figure 137.1 Fibrous papule with hyalinized collagen bundles and increased dilated vascular channels.

Clinical features [2, 3, 4]

History and presentation

The lesions usually occur singly on the nose. Occasionally, they may occur on the forehead, cheeks, chin or neck, and there may rarely be multiple. The papule develops slowly as a dome-shaped, skin-coloured or slightly red or pigmented lesion, which is usually sessile. Most are asymptomatic, but about one-third bleed on minor trauma.

Differential diagnosis

The main clinical consideration is that of an intradermal melanocytic naevus and less commonly, a basal cell carcinoma.

Management

The lesion is benign, but it may easily be excised usually by shave biopsy for cosmetic reasons.

Storiform collagenoma [1, 2]

Definition and nomenclature

Storiform collagenoma is a fibrous hypocellular cutaneous lesion which, when multiple, may be associated with Cowden disease or phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) hamartoma syndrome (multiple hamartoma and neoplasia syndrome; see Chapter 147) [3].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is relatively rare.

Age

There is a wide age range with a predilection for adults [2, 3].

Sex

No sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

The aetiology of sporadic cases is unknown. In the setting of Cowden syndrome, the development of multiple lesions is associated with loss-of-function mutations in PTEN, leading to hyperactivity of the mTOR pathway.

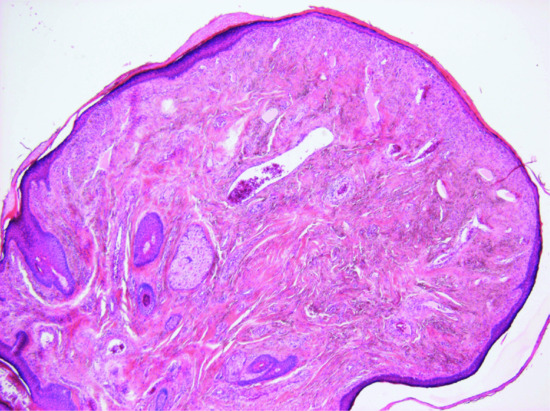

Pathology

Storiform collagenoma typically consists of a fairly well-circumscribed dermal nodule with prominent hypocellular hyalinized collagen bundles in a storiform pattern (Figure 137.2). Bland spindle-shaped cells are rare. A similar histological pattern may be seen in the late stages of lesions as diverse as pleomorphic fibroma, fibrous histiocytoma (FH) and myofibroma and it has been proposed that it does not represent a distinctive entity but a reaction pattern [4, 5].

Figure 137.2 Storiform collagenoma. Poorly cellular stroma composed of hyalinized collagen in a storiform pattern.

A more cellular variant containing multinucleated bizarre cells has been described as giant cell collagenoma [6]. The latter is a potential link between pleomorphic fibroma (see later) and sclerotic fibroma as it has been proposed that both entities are part of the same spectrum [7].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Storiform collagenoma usually presents as a small, solitary, asymptomatic papule, with wide anatomical distribution.

Management

Simple excision is curative.

Pleomorphic fibroma

Definition [1]

Pleomorphic fibroma is a relatively rare lesion with features very similar to those of a fibroepithelial polyp (skin tag), but characterized histologically by bizarre mono- or multinucleated stromal cells.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Pleomorphic fibroma is relatively rare.

Age

Mainly in adults.

Sex

No sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

The aetiology is unknown.

Pathology

Normal or mildly acanthotic epidermis surrounds a collagenous and vascular stroma containing scattered bizarre mono- or multinucleated cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei. Mitotic figures are rare.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Presentation is in the form of a lesion with clinical findings of a fibroepithelial polyp with wide anatomical distribution with some predilection for perianal skin and the face.

Management

Simple excision is curative, and there is no tendency for local recurrence.

Acquired digital fibrokeratoma [1]

Definition

A benign lesion, possibly a reaction to trauma, which occurs on the fingers and toes [2] (Figure 137.3), although the palms and the soles have occasionally been involved.

Figure 137.3 Clinical appearance of an acquired digital fibrokeratoma.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The incidence is low.

Age

Adults are usually affected.

Sex

There is no sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The histology shows thick collagen bundles, thin elastic fibres and increased vascularity. Occasionally, there is an obvious increase in fibroblasts, and rarely the collagen bundles may be separated by oedema [3]. The epidermis is relatively normal, but acanthosis and hyperkeratosis may occur.

Clinical features

History and presentation

The lesion usually occurs as a solitary dome-shaped lesion, with a collarette of slightly raised skin at its base. Occasionally, it may be elongated or pedunculated. Giant lesions may occasionally occur [4]. The surface may appear to be slightly warty.

Differential diagnosis

There is a wide clinical differential diagnosis, which includes dermatofibroma, viral wart, supernumerary digit and cutaneous horn. Histologically, the lesion is extremely similar to the Koenen tumour [5], the periungual fibrous lesion that arises from the nail fold in tuberous sclerosis.

Management

Simple excision is curative.

Nodular fasciitis [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Definition and nomenclature

A rapidly enlarging subcutaneous neoplasm due to a proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts and that histologically resembles a sarcoma.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is relatively common. The intravascular and cranial variants of fasciitis are rare [6, 7].

Age

It is more common in young adults but can occur at any age. Intravascular fasciitis is more common in young adults and cranial fasciitis tends to occur in children less than 2 years of age [6, 7].

Sex

There is no predilection for either sex except for cranial fasciitis that is more common in males [7].

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

There is no clear evidence that trauma initiates the lesions although trauma may play a role in cranial fasciitis [8].

Pathology [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

These lesions may look extremely worrying in view of the high mitotic rate and rapid growth (see later). The tumour is only focally circumscribed and it is composed of bundles of fairly uniform fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with pink cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei and a single small nucleolus. Myxoid change and mucin deposition is often prominent, resulting in a typical tissue culture-like appearance (Figure 137.4). In the background, there are numerous small delicate blood vessels, extravasated red blood cells and scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells. Multinucleated giant cells may be seen, and they resemble osteoclasts. Mitoses are usually numerous, but there are no abnormal forms. Hyalinized collagen bundles are often present and may display a keloidal appearance. At the periphery, compact bundles of fibroblasts and capillaries probe the fascial planes and may infiltrate fat or skeletal muscle. It is not surprising that this histological picture is relatively often confused with that of a malignant tumour. Variants of nodular fasciitis include those with metaplastic bone (ossifying fasciitis); a variant that involves the periosteum (periosteal fasciitis); a variant that involves the scalp and tends to occur in children (cranial fasciitis) [6]; and a variant within the lumen of a blood vessel (intravascular fasciitis) [7, 9]. A rare variant of intradermal nodular fasciitis has also been described [10, 11]. Intra-articular location may also be seen [12]. Tumour cells are variably positive for smooth muscle actin and calponin [13] and usually negative for smooth muscle markers including desmin and h-caldesmon [14]. The histological diagnosis may be very difficult, especially in small biopsies. Confusion with a sarcoma or with fibromatosis are major pitfalls, with obvious detrimental consequences.

Figure 137.4 Typical tissue culture-like appearance of nodular fasciitis with prominent myxoid background.

Immunohistochemistry may be useful in the distinction between fibromatosis and nodular fasciitis. The former tend to display nuclear β-catenin positivity, while the latter are usually negative or display cytoplasmic positivity only [15]. However, some fibromatoses, especially those superficially located, are negative for this marker and the diagnosis should be based on careful clinicopathological correlation.

Genetics

The MYH9-USP6 fusion gene has consistently been identified in lesions confirming the neoplastic nature of this tumour [16]. Lesions like this with a self-limited life and a distinctive clonal genetic translocation have been referred to as transient neoplasms [16].

Clinical features [1, 2, 3, 4]

History and presentation

The majority of tumours appear as tender rapidly growing masses beneath the skin. The average size is 1–3 cm in diameter. The commonest situation is the upper extremities, particularly the forearm, but the lesion can occur anywhere, including the orbit and the mouth [9]. Lesions on the head and neck often present in children. In nearly half the patients, the tumour has been noticed for only 2 weeks or less when they come for advice.

Differential diagnosis

The rapid growth of the lesion may suggest a clinical diagnosis of malignancy.

Disease course and prognosis

Resolution usually follows incomplete surgical removal. Local recurrence is exceptional.

Management

Simple excision is therefore an adequate treatment.

Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digits [1, 2, 3]

Definition

This is a reactive myofibroblastic proliferation with bone formation, which occurs exclusively on the digits.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is rare.

Age

It presents predominantly in young adults although presentation can be at any age.

Sex

Males are more often affected than females.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Trauma appears to be an important factor in the development of the tumour.

Pathology

The tumour is ill defined and similar to nodular fasciitis, except for the fact that there is formation of osteoid and mature bone. Oedematous stroma, vascular proliferation and bundles of spindle-shaped myofibroblast-like cells are seen intermixed with osteoid and mature bone. Mitotic figures are found and their number depends on the age of the lesion.

Clinical features

History and presentation

The lesion grows rapidly and it is not attached to bone. The fingers are more commonly affected than the toes.

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is rare.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Ischaemic fasciitis [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Definition and nomenclature

Ischaemic fasciitis is a reactive pseudosarcomatous fibroblastic/myofibroblastic proliferation that often occurs as a result of alterations in local circulation and sustained pressure in immobilized patients.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Ischaemic fasciitis is relatively rare.

Age

Most patients are elderly usually between the seventh and ninth decades of life.

Sex

There is a slight predilection for males.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Persistent ischaemia and trauma to the affected area in immobilized patients is an important factor in the development of the lesion. However, in many cases there is no association with immobility or debilitation has been found [4].

Pathology

The lesion is poorly circumscribed and contains areas of fibrosis, vascular proliferation, necrosis and focal myxoid change. Thrombosed blood vessels with recanalization and areas of fibrinoid necrosis, focal haemorrhage and mononuclear inflammatory cells are additional features. In the background, there are variable numbers of spindle-shaped myofibroblasts/fibroblasts with vesicular or hyperchromatic nuclei and a prominent nucleolus. Mitotic figures may be seen, but are not prominent.

Clinical features

The lesion presents as an asymptomatic subcutaneous mass, predominantly over bony prominences that may extend to deeper soft tissues and to the overlying dermis.

Management

Excision of the lesion is an adequate treatment.

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy [1-5]

Definition

This is a benign, fibroblastic/myofibroblastic, deep dermal and subcutaneous tumour presenting in children and characterized by three distinctive pathological components, as described below.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

This is a rare tumour.

Age

The majority of cases present in children under the age of 2. A quarter of the cases present at birth.

Sex

Males are more affected than females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The tumour is composed of three components:

- Bundles of interlacing, elongated, bland, wavy spindle-shaped cells in a variable collagenous background.

- Nests of more immature round cells with focal myxoid change.

- Mature adipose tissue.

In a number of cases a focal pseudoangiomatous component is seen [6]. A focal resemblance to a neurofibroma may be seen when the first component predominates, but tumour cells are actin positive and S100 negative [7].

In the dermis overlying the tumour, eccrine glands may show secondary changes including hyperplasia, papillary projections and squamous syringometaplasia [8].

Genetics

Although usually considered to be a hamartoma, it is probably neoplastic in nature. This is further suggested by the presence of complex structural rearrangements demonstrated recently in a single case and involving chromosomes 1, 2, 4 and 17 [9].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Most cases present as an asymptomatic, solitary, skin-coloured plaque/nodule only a few centimetres in diameter. Exceptional tumours are very large and multifocal [10]. Rarely, pigmentary changes and/or hypertrichosis may be seen [11]. The tumour grows rapidly and has a predilection for the axillae, arm and shoulder girdle [1, 2, 3]. Rare cases occur on the head and neck [6]. A familial association has not been reported.

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is exceptional.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice [5]; recurrences are exceptional.

Calcifying fibrous tumour/pseudotumour [1,2,3]

Definition

This is a rare, benign, hypocellular tumour characterized by dense collagen bundles, areas of calcification and a patchy mononuclear cell infiltrate. This lesion has no relation with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour as was originally suggested [3].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

This is very rare.

Age

Most lesions occur in children but rare cases may present in young adults.

Sex

There is no sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The tumour typically consists of haphazardly arranged collagen bundles with scattered bland fibroblasts, focal small calcifications and focal aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Tumour cells are positive for CD34 and may be focally positive for smooth muscle actin and more rarely for desmin [3].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Lesions present as a fairly large subcutaneous or deeper asymptomatic mass with a wide anatomical distribution. Cases may also occur in internal organs [3].

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is rare.

Management

The treatment of choice is simple excision.

Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma [1, 2]

Definition

This is a rare fibroblastic tumour characterized by a nodular proliferation of bland spindle-shaped cells surrounding nodules at different stages of calcification. Cartilage and, less commonly, bone formation may be seen.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are very rare.

Age

Most cases present in children.

Sex

There is no sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The growth pattern is multinodular. Tumour cells are elongated, with scanty pink cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei and very rare mitotic figures. Tumour nodules frequently contain areas of calcification, which are surrounded by tumour cells in a pattern reminiscent of palisading.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Lesions have a predilection for the hands and, less commonly, the feet. Occurrence at other sites is rare but tumours may present in places as diverse as the knee, back and thigh [1, 2]. Tumours are small, slowly growing and usually asymptomatic. Multiple lesions are exceptional [3].

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is observed in 50% of cases but malignant transformation is exceptional [4].

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Dermatomyofibroma

Definition and nomenclature [1-4]

Dermatomyofibroma presents as a benign, dermal and superficial subcutaneous myofibroblastic proliferation microscopically mimicking a fibromatosis. The tumour, however, has no potential for local recurrence and lacks an infiltrative growth pattern.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Dermatomyofibroma is relatively rare.

Age

Most patients are young adults with children only exceptionally affected [5, 6, 7].

Sex

There is predilection for females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Low-power examination reveals a plaque-like proliferation of fascicles of myofibroblast-like cells with an almost parallel orientation to the epidermis. Tumour cells are bland, and mitotic figures are very rare. The tumour does not destroy adnexal structures, but may extend focally into the subcutaneous tissue. Rare cases with haemorrhage may mimic plaque-stage Kaposi sarcoma (see Chapter 139) [8]. The latter, however, is always positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV8). Tumour cells are variably positive for smooth muscle actin and calponin. The latter two markers, however, may be negative or minimally positive in some cases. CD34 is focally positive in around 20% of cases [7].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Dermatomyofibroma presents as a solitary, asymptomatic, skin-coloured or hypopigmented plaque measuring less than 4 cm in diameter. Multiple lesions are rarely seen and an exceptional case has presented with a linear pattern [9].

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is almost never seen.

Management

Simple excision is curative.

plaque-like CD34-positive dermal fibroma [1, 2, 3]

Definition and nomenclature

This is a very rare lesion characterized by a superficial dermal plaque-like proliferation of fibroblasts and not of dermal dendrocytes as originally reported [1].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are very rare.

Age

The age range is wide. Earlier reports were mainly in children but tumours also present in adults. Rare lesions are congenital.

Sex

Females are more frequently affected than males.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The epidermis appears unremarkable or slightly flattend and in the dermis there is a fairly monotonous proliferation of spindle-shaped bland cells in a plaque-like distribution. These cells are positive for CD34 and negative for S100. Only a few scattered cells in the background are positive for factor XIIIa (FXIIIa). The appearance may resemble early DFSP and distinction between the two conditions is very important. Plaque-like CD34-positive dermal fibroma hardly ever extends only focally into the subcutis and does not do it in a lace-like pattern. Furthermore, this tumour does not show the typical t17;22 translocation typically found in DFSP [3].

Clinical features

History and presentation

There is predilection for the trunk and limbs. Lesions are sometimes round or oval and have an atrophic appearance and a yellow-red colour. More often, however, clinical features are non-distinctive.

Disease course and prognosis

Lesions are benign.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Angiomyofibroblastoma [1, 2-4]

Definition

Angiomyofibroblastoma is a distinctive benign neoplasia that occurs almost always in the pelvis and perineum, particularly affecting the vulva. There is some overlap with another tumour that presents in the pelvis and perineum (cellular angiofibroma, see later) and also with aggressive angiomyxoma [5].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is rare.

Age

Young to middle-aged females and very rarely in elderly females.

Sex

Predominantly in females. Exceptional cases in males.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Lesions are well circumscribed and consist of a mixture of round and spindle-shaped bland cells in a myxoid or oedematous stroma with numerous small dilated blood vessels. There is a tendency for tumour cells to surround the vascular channels. Mitotic activity is not usually present. In a number of cases, there are collections of mature adipocytes [4].

Cytological atypia secondary to degeneration is sometimes seen. Tumour cells are positive for desmin and for oestrogen and progesterone receptors. They are only focally positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin. Some tumours are variably positive for CD34.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Tumours present mainly in the vulva and in males usually affect the scrotum. Lesions are subcutaneous, asymptomatic and measure less than 5 cm in diameter. Occasional larger pedunculated lesions have been reported [6].

Disease course and prognosis

Tumours are benign with no tendency for local recurrence. Only one malignant tumour has been reported [7].

Management

The treatment is simple excision.

Cellular angiofibroma [1-4]

Definition and nomenclature

Cellular angiofibroma is a distinctive benign neoplasm that occurs almost exclusively in the vulva and less commonly in the scrotum and inguinal soft tissues of men. Some cases overlap histologically with angiomyofibroblastoma and a relationship with spindle cell lipoma and mammary-type myofibroblastoma has been suggested [2]. The latter is based on histological overlap and also on the presence of a distinctive cytogenetic abnormality (see later).

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

It is relatively rare.

Age

Predominantly in young adults.

Sex

Most tumours occur in females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Tumours are sharply circumscribed but not encapsulated and are characterized by short, usually bland, spindle-shaped cells with scanty ill-defined pale pink cytoplasm. These cells are arranged in bundles and the degree of cellularity varies. In the background, there are thin collagen bundles and numerous small to medium-sized blood vessels. Mitotic figures are rare and cytological atypia may be occasionally seen in some cases. Scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes, and degenerative changes are often identified. The latter consist of haemorrhage, thrombosis, hyalinization and haemosiderin deposition. In myxoid areas, mast cells are present and many tumours contain variable numbers of mature adipocytes. The most consistent immunohistochemical finding is the presence of diffuse positivity for CD34 in many cases. Muscular markers including actin and desmin tend to be negative but positivity has been reported in male tumours. In a few cases, there is focal positivity for oestrogen and progesterone receptors.

Genetics

A monoallelic deletion of RB1 located on chromosome 13q14 is often found [5].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Tumours presenting as a small, well-circumscribed, asymptomatic, subcutaneous nodule. In males, lesions tend to be larger and may be related to a hydrocele or a hernia [2].

Disease course and prognosis

Lesions are benign with little or no tendency for local recurrence. Histologically, exceptional tumours with atypia or sarcomatous transformation have been described but they have not behaved in an aggressive manner, although follow-up was limited [5, 6].

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Elastofibroma [1, 2, 3]

Definition and nomenclature

Elastofibroma is a reactive, probably degenerative, process of the elastic fibres of deep soft tissues that occurs almost exclusively around the shoulder. Although the lesion is regarded as degenerative, the finding of chromosomal alterations (see later), and of clonality in some cases, has led to the suggestion that it represents a neoplastic process [4].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Unknown. However, computed tomography (CT) scans detected incidental lesions in 2% of persons more than 60 years of age and in 16% of adult autopsies in persons older than 55 [5, 6].

Age

Most lesions occur in old-aged individuals.

Sex

No sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Although elastofibroma has been regarded as the result of a degenerative process involving elastic fibres and in association with trauma, the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities in some tumours suggest that it is more likely to be neoplastic (see later).

Genetics

Comparative genomic hybridization in a series of elastofibromas has found chromosomal alterations in a percentage of cases. The most common alteration consists of gains at chromosome Xq12-q22 [7].

Pathology

The mass is poorly circumscribed, and the appearances are characteristic. Abundant hypocellular hyalinized collagen containing numerous large thick eosinophilic elastic fibres is the most distinctive feature. Sometimes the fibres are beaded and fragmented. Staining for elastic tissue nicely highlights the changes.

Clinical features

History and presentation

It presents as an asymptomatic slowly growing mass on the posterior upper trunk. Pain is very rare. Lesions in other locations, including internal organs, are exceptional. Multiple lesions are usually bilateral and may be symmetrical [8].

Disease course and prognosis

There is no tendency for local recurrence.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Inclusion body (digital) fibromatosis [1-3, 4]

Definition and nomenclature

Inclusion body fibromatosis is a fibro/myofibroblastic proliferation that almost only occurs on the fingers and toes. It is characterized by bright, round, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Lesions are rare, representing 2% of fibroblastic tumours in childhood [5].

Age

Most lesions present either at birth or during the first year of life. Presentation in adults is exceptional [6].

Sex

Males and females are equally affected.

Pathophysiology

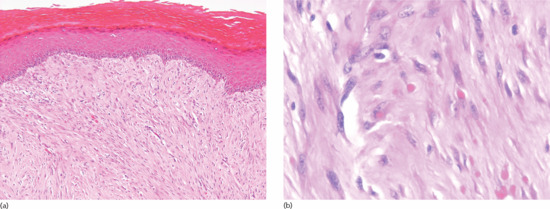

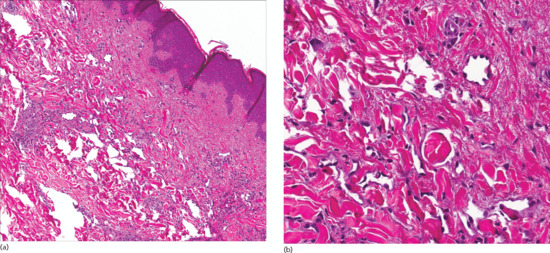

Pathology

Monomorphic bundles of bland myofibroblast-like cells are seen in the dermis (Figure 137.5a) and often the subcutis. Tumour cells have vesicular nuclei, an inconspicuous nucleolus and pink cytoplasm. Some mitotic figures may be seen. A distinctive feature is the presence of variable numbers of small round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions in tumour cells (Figure 137.5b). These are periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) negative, but stain red with Masson trichrome. They also stain for smooth muscle actin.

Figure 137.5 (a) Bundles of bland myofibroblast-like cells in the dermis in a case of inclusion body fibromatosis. (b) Numerous typical eosinophilic intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Lesions present as small multiple nodules with a predilection for the dorsal or dorsolateral aspect of the third, fourth and fifth digits. Involvement of the first digits (thumb and hallux) does not occur. Simultaneous involvement of fingers and toes is very rare. New lesions often develop over a long period of time. Only rare cases have been described at other sites including the leg, arm and breast [4, 7].

Disease course and prognosis

Spontaneous regression is sometimes seen [8]. Local recurrence may be seen in up to 25% of cases. Aggressive behaviour has not been described.

Management

Simple excision may be required for lesions that interfere with function, but simple observation of histologically confirmed lesions may be all that is necessary.

Fibroma of tendon sheath [1, 2]

Definition and nomenclature

This is a distinctive well-circumscribed fibroblastic tumour, presenting almost exclusively on the distal extremities.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are rare.

Age

Fibroma of tendon sheath presents mainly in young to middle-aged adults and exceptionally in children.

Sex

Males and females are equally affected.

Pathophysiology

Pathology [1, 2]

The neoplasm is multilobular and well circumscribed, and consists of cellular or poorly cellular areas on a background of variably hyalinized stroma. Stromal clefting is usually prominent. Tumour cells are spindle shaped, with scanty cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Cytological atypia tends to be absent, and the mitotic count is low. Degenerative changes are seen in some cases and consist of cystic degeneration, myxoid change and bony metaplasia. Rare giant cells are sometimes identified.

Genetics

A translocation at t(2;11)(q31-32;q12) has been demonstrated in a case of fibroma of tendon sheath [3]. This translocation has also been demonstrated in cases of desmoplastic fibroblastoma (p. 137.12).

Clinical features [1, 2]

History and presentation

It is a small slowly growing asymptomatic tumour, with a marked predilection for the distal upper limb, particularly the hand and fingers (1st, 2nd and 3rd). Rare lesions may present with carpal tunnel syndrome [4]. Tumours on the foot are much less common.

Disease course and prognosis

About 20% of cases recur locally but the growth is not destructive.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Desmoplastic fibroblastoma [1, 2]

Definition and nomenclature

Desmoplastic fibroblastoma represents a distinctive subcutaneous fibroblastic tumour consisting of a prominent collagenous stroma.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are relatively common.

Age

Presentation is in middle-aged to old adults.

Sex

Males are twice as frequently affected as females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

This is a well-circumscribed tumour composed of bland elongated or stellate cells, with a background collagenous stroma and focal myxoid change. Mitotic figures are very rare.

Genetics

A translocation t(2;11)(q31;q12) is characteristically found in this tumour [3]. The rearrangement of the 11q12 chromosome results in the deregulated expression of FOSL1 [3, 4].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Lesions present as an asymptomatic nodule less than 4 cm in diameter, at any body site with a predilection for the back and limbs.

Disease course and prognosis

There is no tendency for local recurrence.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Nuchal–type fibroma [1, 2]

Definition and nomenclature

Nuchal fibroma is a dermal or subcutaneous tumour consisting of hypocellular dense collagen.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Occurrence is rare.

Age

Most cases present in adults between the third and fifth decades of life.

Sex

Males are much more commonly affected than females.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Patients often have type 2 diabetes.

Pathology

Dense aggregates of collagen with very few cells and entrapment of adipose tissue. Inflammation is minimal and consists of a few scattered lymphocytes. In some cases, focal proliferation of nerves is seen mimicking a traumatic neuroma.

Clinical features

History and presentation

The great majority of cases present by far on the nape of the neck. Tumours can also present on the upper back, limbs and face [3]. Coexistence with scleredema is possible, probably reflecting the association with diabetes, and lesions identical to nuchal fibroma are recognized to occur in Gardner syndrome (Chapter 80) and are known as Gardner-associated fibromas [3, 4]. The latter may be multiple, present in various locations and may recur. These lesions may be the first clue as to the existence of Gardner syndrome.

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence is common but lesions do not behave aggressively.

Management

Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Palmar and plantar fibromatosis (superfi cial fibromatoses) [1, 2]

Definition and nomenclature

Palmar and plantar fibromatoses are superficial neoplastic proliferations of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that have a tendency for local recurrence, but do not metastasize.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Palmar fibromatosis is fairly common and more common than plantar fibromatosis. The incidence of both conditions but particularly the former increases with age.

Age

Both conditions affect middle-aged to elderly patients and are uncommon in younger individuals. However, children may rarely be affected, particularly by plantar fibromatosis [3].

Sex

Both lesions are more common in men, but the sex difference is more marked in palmar lesions.

Ethnicity

Affected patients are mainly of northern European origin; non-whites are rarely affected.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Genetic predisposition, as well as trauma, is thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of these conditions. Associations with diabetes, alcoholic liver disease and epilepsy have also been described.

Pathology

Early lesions are fairly cellular and consist of bundles of bland fibroblasts with some collagen deposition. The latter increases considerably in older lesions. Interestingly, although superficial fibromatoses are very similar histologically to deep fibromatosis (abdominal, extra-abdominal and mesenteric fibromatosis), the behaviour of superficial fibromatosis is not usually aggressive. This may be due to the fact that deep fibromatosis often display mutations of the APC gene or somatic mutations of the gene encoding β-catenin, while these mutations are absent in superficial fibromatosis. Intriguingly however, although deep fibromatoses often display nuclear expression of β-catenin, this is also seen in a smaller percentage of superficial fibromatoses without gene mutations [4].

Coexistence between the two variants of fibromatoses and desmoid tumours, penile fibromatosis (Peyronie disease) and knuckle pads, may be seen.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Palmar fibromatosis presents as indurated nodules or as an ill-defined area of thickening, bilateral in about 50% of cases that may result in contracture. Plantar fibromatosis usually consists of a single nodule.

Disease course and prognosis

Functional limitation is common. Lesions are prone to local recurrence.

Management

Complete excision is desirable.

Penile fibromatosis [1,2,3]

Definition and nomenclature

Although usually regarded as a variant of superficial fibromatosis, it is more likely that this disease represents a reactive fibrotic disorder of unknown aetiology.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The condition is rare.

Age

Most patients are middle aged.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

There is an association with type 2 diabetes.

Pathology

In early lesions, there is a patchy chronic mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate and focal vasculitic changes. These changes lead to dense bands of hyalinized collagen in late stages.

Clinical features

History and presentation

It presents as a solitary nodule or multiple nodules close to the corpus cavernosum on the dorsal surface of the shaft, and in most the lesion is small. Pain and curvature of the penis on erection are frequent complaints. The presence of diabetes increases the severity of the disease [4].

Disease course and prognosis

The condition results in penile deformity and sexual dysfunction.

Management

Surgery is the treatment of choice but in recent years less invasive therapies have been attempted. The latter include intralesional injections of interferon α-2b or of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum [5].

Lipofibromatosis [1]

Definition and nomenclature

Lipofibromatosis is a locally aggressive childhood tumour composed of variable amounts of mature adipose and fibroblastic elements.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The condition is very rare.

Age

Tumours occur in infants and children; the majority of cases presenting in the first decade of life.

Sex

There is male predominance (around 60% of cases).

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Tumours are infiltrative and consist of lobules of mature adipose tissue intermixed with bundles of fibroblast-like cells with no cytological atypia and low mitotic activity. By immunohistochemistry, tumour cells are focally positive for S100 protein, CD34, bcl-2, actin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and CD99. The lesion closely resembles a fibrous hamartoma of infancy but has more prominent adipose tissue and lacks the third cellular component seen in the latter, which consists of round primitive-looking cells in a myxoid background.

Genetics

A translocation at t(4;9;6) was reported in a single case [2].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Some tumours are congenital. There is a male predominance. The classical presentation is of a slowly growing ill-defined mass. There is a predilection for the hands and feet, but other sites in the limbs, and less commonly on the trunk, may be affected. The rate of local recurrence is high.

Disease course and prognosis

The tumour is locally aggressive with no metastatic potential. There is high tendency for local recurrence.

Management

Complete excision is desirable.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans [1-3]

Definition

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a locally invasive tumour arising in the dermis and showing fibroblastic differentiation.

Epidemiology [1-3]

Incidence and prevalence

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is uncommon but represents one of the most common dermal sarcomas. The incidence in the USA has been estimated as 4.2 cases per million [4].

Age

Tumours more commonly develop during the third and fifth decades of life. However, presentation during childhood and late life is not particularly rare [5, 6, 7]. Congenital cases have been described [7, 8].

Sex

There is a slight female predilection.

Ethnicity

It is more common in black than in white patients [4].

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

Some cases develop at the site of previous trauma and reports have included a burn scar [9] and the site of vaccination. Exceptional cases have been associated with previous radiotherapy to the area [10]. There is an association between DFSP and children with adenosine deaminase deficient severe combined immunodeficiency [11]. Patients affected by the latter have a higher incidence of tumours presenting at early age and often multicentric.

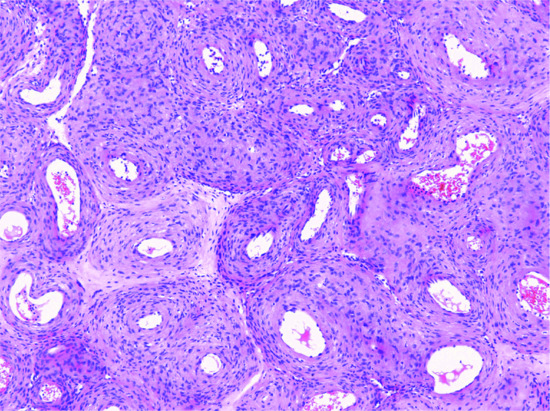

Pathology [1-3]

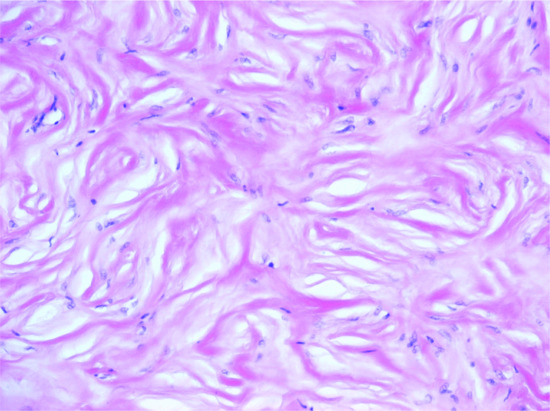

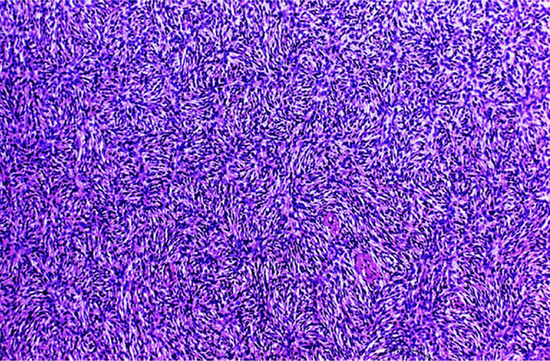

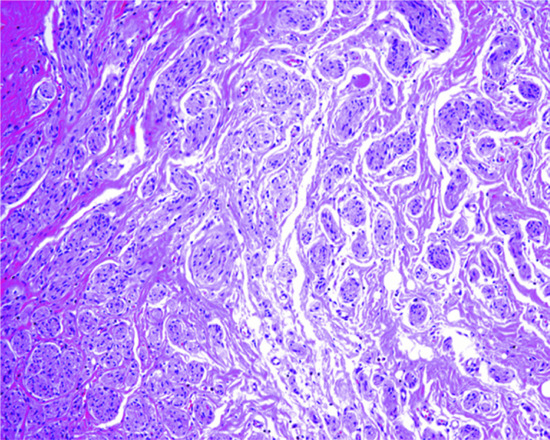

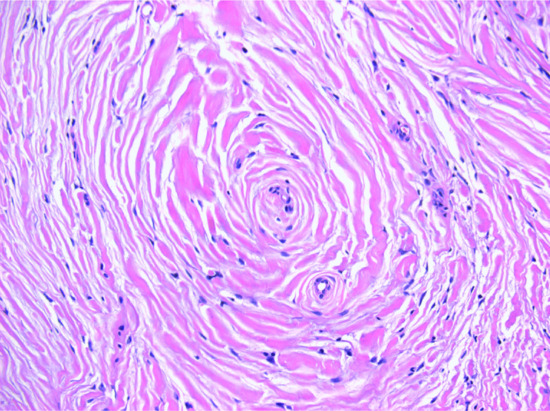

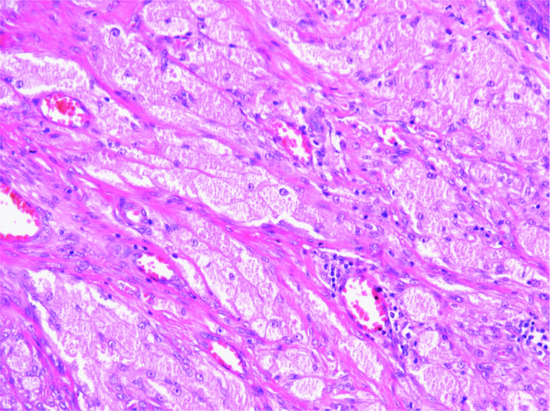

The tumour is usually a solitary multinodular mass. The dermis and subcutaneous tissue are replaced by bundles of uniform spindle-shaped cells with little cytoplasm and elongated hyperchromatic, but not pleomorphic, nuclei. Usually there is little mitotic activity. Deeper involvement may be seen in some cases. Laterally, the tumour cells infiltrate widely between collagen bundles of the deeper dermis and blend into the normal dermis, forming quite definite bands, which interweave or radiate like the spokes of a wheel; this is described as a ‘storiform’ pattern (Figure 137.6). The interstitial tissue contains collagen fibres, except in the most cellular parts of the tumour. The subcutaneous tissue is extensively infiltrated and replaced in a typical lace-like pattern. Myxoid change may be focal or, rarely, prominent; in the latter setting, the histological diagnosis is difficult [12, 13]. Some tumours are colonized by scattered deeply pigmented melanocytes, a variant known as pigmented DFSP (Bednar tumour) [14, 15]. A further variant consists of myoid nodules and is thought to represent myofibroblastic differentiation [16]. Rare cases show focal granular cell change.

Figure 137.6 Pathological appearance of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, showing the storiform or ‘cartwheel’ distribution of the fairly uniform, spindle-shaped tumour cells.

Fibrosarcomatous DFSP [17, 18, 19, 20] is an important variant of this tumour, which is recognized by the focal presence of areas with long sweeping fascicles of tumour cells intersecting at acute angles in a typical ‘herring-bone’ pattern, almost identical to that seen in fibrosarcoma. In these areas, mitoses are increased and there is more nuclear hyperchromatism. P53 expression is increased in fibrosarcomatous areas [20]. Identification of the presence of this pattern, and its quantity, is very important, as it is related to metastatic potential. Fibrosarcomatous areas are more common in recurrent tumours.

Very rare variants of DFSP may show areas of high-grade sarcoma either in the primary tumour or in a recurrence [21].

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may show areas of giant cell fibroblastoma (see later) and either tumour may recur, displaying features of the other tumour [22].

The majority of the lesions are positive on staining with the antibody CD34, although this is not specific for DFSP [23]. Other markers are usually negative but in some cases focal positivity for epithelial membrane antigen may be seen. Fibrosarcomatous areas often show decreased staining with CD34 [19].

Genetics

Cytogenetic studies are helpful, as ring chromosomes indicative of a 17;22 translocation are invariably found [22]. However, it is important to highlight that some cases demonstrate a variant ring chromosome with cryptic rearrangements of chromosomes 17 and 22 [24]. This chromosomal translocation involves the collagen type I α1 (COL1A1) gene on chromosome 17 and the platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB) gene on chromosome 22. The abnormal fusion transcripts resulting from this translocation leads to autocrine stimulation of PDGFB and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRB) and cell proliferation. The fusion transcript is found in almost all examples of the tumour by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [23]. The same cytogenetic abnormality is found in giant cell fibroblastoma, confirming that both tumours are part of the same spectrum.

Clinical features

History and presentation

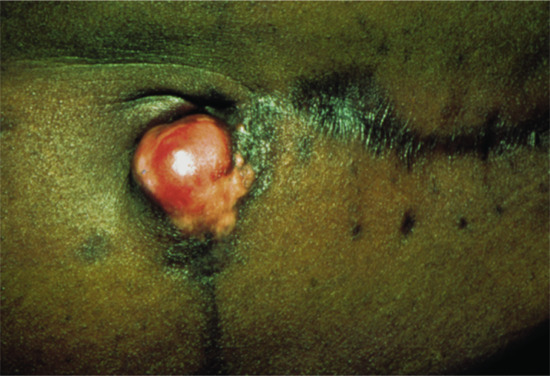

The tumour is more often situated on the trunk (up to half of the cases), particularly in the flexural regions, than on the extremities or the head [1, 2]. Involvement of the limbs is usually proximal. Presentation on the hands and feet, particularly on the digits, is very rare. It may begin in early adult life with one or more small, firm, painless, flesh-coloured or red dermal nodules (Figure 137.7).

Figure 137.7 Recurrent abdominal dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

The tumour starts as a plaque, which may occasionally be atrophic [6, 25]. Progression is usually very slow, and may occur over many years; a significant proportion of tumours only become protuberant after a long period of time [26]. Eventually, nodules develop, coalesce and extend, becoming redder or bluish as they enlarge to form irregular protuberant swellings. At this stage, the base of the lesion is a hard indurated plaque of irregular outline. In the later stages, a proportion of lesions become painful and there may be rapid growth, ulceration and discharge.

Differential diagnosis

In the early stages, it may be impossible to distinguish this tumour from a histiocytoma or a keloid. Some lesions may also be confused with morphoea profunda. The slow progression, deep red or bluish-red colour, and the characteristic irregular contour and extended plaque-like base, are strongly suggestive of DFSP.

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrence of ordinary DFSP is reported to vary from 15% to up to 60% [3, 27, 28]. The fibrosarcomatous variant has a similar rate of local recurrence but a higher rate of metastatic spread [20, 21, 29, 30, 31]. Metastases to lymph nodes and internal organs tend to be extremely rare in pure DFSP [20, 32, 33] but occur in up to 13% of cases with fibrosarcomatous transformation [20, 21, 22, 30, 31].

Management

The tumour should be excised completely, with a generous margin of healthy tissue [34]. The best chance of achieving a complete cure with no recurrence is early detection of small tumours. Local recurrence invariably follows inadequate removal; the clearance necessary to cure the tumour is often underestimated [35]. A margin of between 2 and 4 cm has been recommended [28, 36]. Mohs micrographic surgery has been reported as effective in reducing the rate of local recurrence and it has become the recommended standard treatment in many large centres [37, 38]. If this type of treatment is used it should be performed using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections rather than frozen sections, and evaluation should be by an experienced pathologist. Although Mohs surgery clearly reduces the rate of local recurrences, the latter still occur and sometimes this happens more than 5 years after surgery [39]. Postsurgical radiotherapy has been advocated to reduce the rate of local recurrence [40] but this type of treatment has not been assessed in large series of patients. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that imatinib mesylate, a potent inhibitor of a number of protein kinases including the PDGFR, results in good clinical response in patients with large unresectable or metastatic tumours [41, 42, 43, 44, 45].

Giant cell fibroblastoma [1-3, 4]

Definition

This is a locally recurrent fibroblastic tumour, closely related to DFSP. It is characterized by spindle-shaped, oval or stellate, mono- or multinucleated cells in a fibromyxoid stroma with irregular pseudovascular spaces lined by tumour cells.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are rare.

Age

Most cases present in children. Rare cases are seen in young adults and only exceptionally in older adults.

Sex

About 60% of patients are male.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

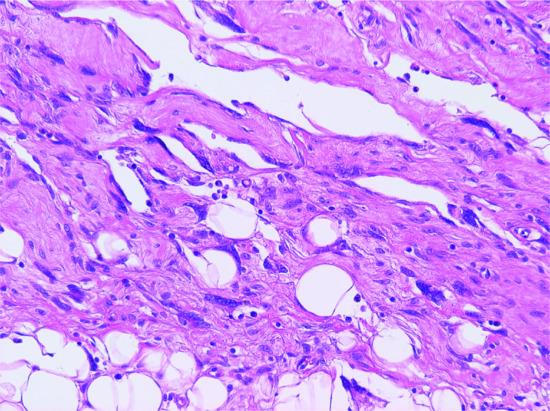

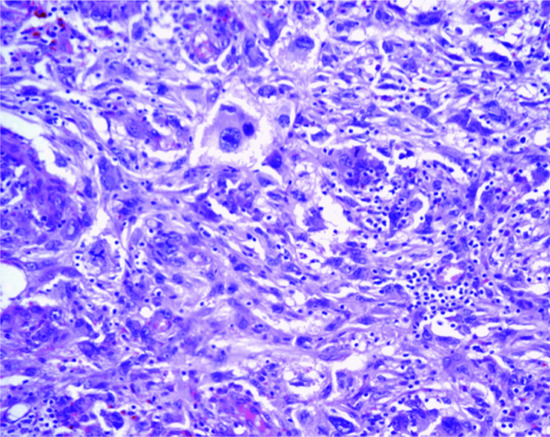

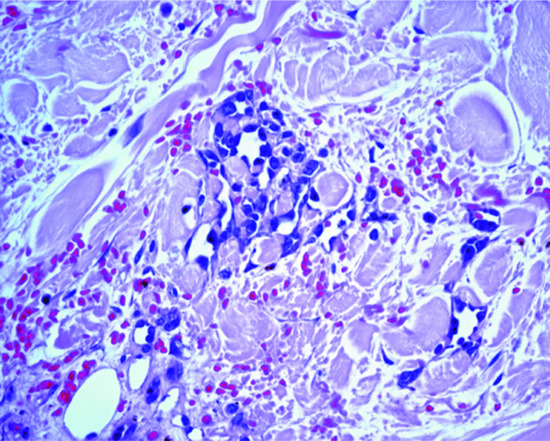

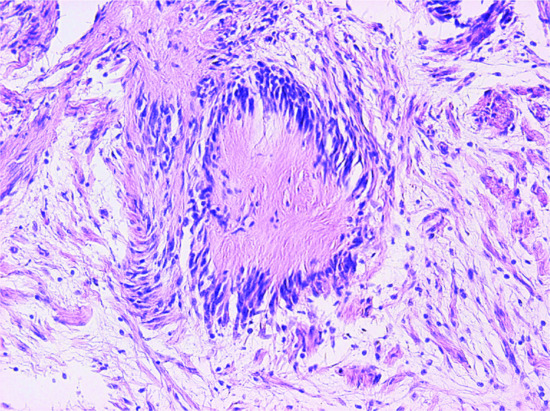

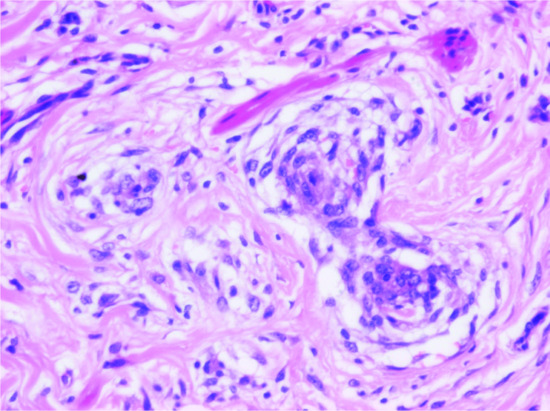

Solid fibromyxoid areas with variable collagen deposition contain stellate and spindle-shaped mono- and multinucleated tumour cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Dilated irregularly branching pseudovascular spaces are commonly seen scattered throughout the lesion. These spaces are lined by tumour cells, which often appear multinucleated (Figure 137.8). Mitotic figures are exceptional. Aggregates of perivascular lymphocytes in an onion-ring pattern and focal haemorrhage are often seen [4]. Focal areas identical to DFSP may be seen and can occupy a substantial part of the tumour. Excised lesions can recur as a pure giant cell fibroblastoma, as a tumour with focal DFSP, or as pure DFSP [4, 5, 6, 7]. All types of tumour cells are positive for CD34.

Figure 137.8 Typical pseudovascular spaces focally lined by multinucleated cells in a case of giant cell fibroblastoma.

Genetics

Ring chromosomes with sequences of chromosomes 17 and 22, identical to those found in DFSP, have been described in this tumour, confirming their close histogenetic relationship [8, 9].

Clinical features [1, 2, 3, 4]

History and presentation

The large majority of cases present as a subcutaneous ill-defined mass but rare tumours are polypoid. It is rare in young adults and more exceptional in older adults. The trunk, axilla and groin are much more commonly involved than the proximal limbs. Head and neck tumours are rare. Lesions measure a few centimetres in diameter and tend to be asymptomatic.

Disease course and prognosis

Recurrence may be seen in about half of the cases, but metastasis has not been reported.

Management

Complete surgical excision with adequate margins is the treatment of choice.

Myxoinfl ammatory fibroblastic sarcoma [1-3, 4]

Definition and nomenclature

Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma is a distinctive, neoplastic process with marked predilection for acral sites, and with histological features closely mimicking an inflammatory process due to the presence of prominent inflammation and virocyte-like inclusions in the nuclei of tumour cells. The latter features were initially thought to indicate an infectious aetiology. A relationship with haemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumour is likely (see p. 137.63). Both tumours share a similar translocation (see later) and an example of the latter lesion progressing to a tumour with features of myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma following recurrence and leading to death of the patient as a result of metastatic disease has been reported [5].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are rare.

Age

Most patients are middle-aged adults. Presentation in children [6] and elderly patients are very rare.

Sex

There is a slight female predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Lesions are lobulated and poorly circumscribed, and involve the subcutaneous fat and often extend to the dermis and deeper tissues, sparing bone. Low-power examination is misleading and the initial impression is that of an inflammatory process. Lobules of hyalinized and myxoid tissue containing variable numbers of inflammatory cells are seen. The latter include lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and less commonly eosinophils and plasma cells. Closer examination reveals variable numbers of neoplastic cells that vary from round to spindle shaped. Some of these cells may be multinucleated. Round cells mimic ganglion cells with nucleoli resembling viral inclusions. Less commonly, vacuolated tumour cells resembling lipoblasts are seen. Mitotic activity is very low. Lesions displaying one or more of the following histological features appear to have a higher rate of local recurrence: areas with complex sarcoma-like vasculature, hypercellular areas and increased mitotic activity or the presence of atypical mitotic figures [4]. Immunohistochemistry shows that tumour cells are variably positive for D2-40 (86%), CD34 (50%), keratins (33%), actin (26%), CD68 (27%) and very rarely for desmin, S100 and EMA [4].

Genetics

Very few cases have been subjected to cytogenetic studies [7, 8]. In two cases published, one showed a complex karyotype with a reciprocal translocation t(1;10)(p22;q24) and loss of chromosomes 3 and 13 [7], and the other a translocation t(2;6)(q31;p21.3) [8]. These findings confirm the theory that these lesions are neoplastic.

Clinical features

History and presentation

Characteristically, tumours are longstanding, asymptomatic and slowly growing, multinodular and usually measure no more than 4 cm. The great majority occur on acral sites, particularly the dorsal aspect of the hands and wrists, followed by the feet. However, lesions may rarely present elsewhere on the limbs (the arm, forearm and thigh) [4, 6, 9, 10] and exceptionally elsewhere in the body, including the head and neck [4, 5, 9]. Most cases are clinically diagnosed as a ganglion cyst or as a giant cell tumour of tendon sheath.

Disease course and prognosis

The rate of local recurrence is high, varying from 11 to 67% in different series [1, 2, 4]. The absence of clear surgical margins correlates with higher recurrence rate. Distal metastases are exceptional and are mainly to regional lymph nodes.

Management

The treatment of choice is wide local excision and this often implies amputation.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma [1-4]

‘Malignant FH’ is an umbrella term encompassing a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that initially included five different clinicopathological subtypes: pleomorphic, myxoid, giant cell, inflammatory and angiomatoid. There is little relation between the different subtypes; the angiomatoid variant has recently been reclassified in the group of fibrohistiocytic tumours and the name changed to ‘angiomatoid FH’. The concept of pleomorphic malignant FH has been challenged as not representing a distinct group of neoplasms but a heterogeneous category, including pleomorphic poorly differentiated sarcomas. If cases classified as such are extensively studied with ancillary studies including immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy and more recently cytogenetics [5, 6], a large percentage may be reclassified as pleomorphic variants of other soft-tissue tumours, including liposarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. The myxoid variant of malignant FH is now known as ‘myxofibrosarcoma’, and it is likely to show fibroblastic differentiation; this tumour often involves the skin because of its frequent origin in the subcutis, and it will therefore be discussed in more detail below. Angiomatoid FH has been described under fibrohistiocytic tumours. The inflammatory and giant cell variants of malignant FH hardly ever involve the skin and will not be discussed further.

Myxofibrosarcoma [1-3,4]

Definition and nomenclature

Myxofibrosarcoma is a neoplasm of the subcutis and deeper soft tissues with variable cellularity, myxoid change and cells with pleomorphic nuclei. The cellular end of the spectrum is identical to a pleomorphic malignant FH, and the diagnosis is made based on the presence of myxoid areas with less cellularity and a lobular pattern. The myxoid change should be seen in 10% or more of the tumour before a lesion is classified as myxofibrosarcoma.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Age

Presentation is mainly in middle-aged to old adults.

Sex

There is a slight male predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology [4]

These tumours have a lobular growth pattern. They are classified according to the degree of cellularity and pleomorphism into low, medium and high grade. Low-grade tumours are paucicellular and consist of round or elongated bland and pleomorphic cells in a prominent myxoid stroma. The atypical cells have irregular hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic figures are relatively frequent. In the background, a fairly prominent number of thin-walled vascular channels with a typical curvilinear pattern are seen. Vacuolated, Alcian blue positive cells, focally mimicking lipoblasts, are relatively frequent. In some tumours, hypocellular areas blend with more cellular areas containing cells with increased pleomorphism; such tumours are classified as intermediate grade. Tumours with high cellularity (high grade) are indistinguishable from the so-called pleomorphic malignant FH and may have necrosis. Grading of lesions is important, because the rate of local recurrence and metastasis varies (see later). Some tumours, particularly high-grade lesions, may have epithelioid morphology [5]. Tumour cells are positive for vimentin and only rarely display very focal positivity for actin.

Clinical features

History and presentation

This tumour mainly presents in the extremities, particularly the lower limbs followed by the upper limbs and less commonly the trunk, head and neck [4]. Typically, an asymptomatic mass, measuring several centimetres in diameter, is found in the subcutis or deeper soft tissues. This is one of the sarcomas that more often involves the dermis as a result of extension from the subcutis or deeper soft tissues, rather than having a dermal origin. About 50% of cases arise in the subcutaneous tissue and involve the overlying dermis [5]. Exceptional cases have been reported in association with a burn scar [6].

Disease course and prognosis

High-grade lesions have a higher tendency for local recurrence and for metastatic spread to regional lymph nodes. The overall 5-year survival is between 60 and 70% [4, 5, 6]. Tumours with epithelioid morphology appear to have a more aggressive behaviour [7].

Management [4]

Excision with clear margins is essential.

Low–grade fibromyxoid sarcoma [1-3]

Definition and nomenclature

This distinctive neoplasm is regarded as a low-grade variant of fibrosarcoma. It is characterized by deceptive, bland, spindle-shaped cells in a stroma with curvilinear blood vessels and either collagenous or myxoid background.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are rare.

Age

It is seen mainly in young to middle-aged adults.

Sex

There is no sex predilection.

Pathophysiology

Pathology [1-3]

The tumour consists of a proliferation of wavy, bland, spindle-shaped cells arranged in short fascicles and surrounded by a collagenous or myxoid stroma. Cellularity varies and tumour cells are usually bland with very rare mitotic figures. Frequent, elongated, thin-walled blood vessels are seen throughout the tumour. Only a small number of cases display some degree of cytological atypia. As a result of the deceiving histological appearances, the tumour is often diagnosed as benign. In a proportion of cases there are focal areas with hyalinized collagen surrounded by epithelioid tumour cells forming rosettes. This variant of the tumour was originally described as hyalinizing spindle cell tumour with giant rosettes [5]. The presence of rosettes does not influence the behaviour of the neoplasm. Immunohistochemistry is of limited value as tumour cells are negative for most markers. They may be, however, positive for EMA and this may lead to a misdiagnosis of perineurioma.

Genetics

Tumours show a distinctive translocation, t(7;16)(q33;p11), leading to fusion of the FUS and CREB3L2 genes [4]. This finding is very useful for confirmation of the diagnosis by FISH.

Clinical features

History and presentation

The tumour usually presents as a slowly growing lesion in young to middle-aged adults, with an equal sex incidence; it has a predilection for the proximal extremities, followed by the trunk. Tumours tend to be longstanding and asymptomatic and present as a mass, measuring several centimetres in diameter, and located in the subcutis or deeper soft tissues. Subcutaneous lesions are often clinically diagnosed as a lipoma.

Disease course and prognosis

In the largest series of cases reported so far it has been shown that local recurrence occurs in 9% of cases, metastases in 9% and mortality in 2% [6]. It seems that areas with higher grade morphology do not confer a more aggressive behaviour. However, this needs to be confirmed in further studies. Metastatic spread may occur many years after the original diagnosis and therefore long-term follow-up is indicated.

Management

Excision with clear margins is essential.

FIBROHISTIOCYTIC TUMOURS

Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath [1,2,3,4]

Definition

This is a benign tumour that in its localized variant occurs mainly on the hands, and consists of a nodular proliferation of histiocyte-like cells with scattered multinucleated giant cells and variable numbers of mononuclear inflammatory cells. The diffuse variant of this tumour that involves joints is not discussed further in this chapter.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Tumours are relatively rare.

Age

Young to middle-aged adults.

Sex

There is a predilection for females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

It is a multinodular lesion composed of sheets of histiocyte-like cells with bland vesicular nuclei, intermixed with multinucleated giant cells, foamy cells, siderophages and scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells. Hyalinization, haemosiderin deposition and cholesterol clefts are often seen. No histological features predict lesions that recur locally [3].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Tumours present mainly on the hands with a predilection for the fingers. They are typically between 1 and 3 cm in diameter and asymptomatic, although they may interfere with function. Multiple tumours are very rare [4].

Disease course and prognosis

The rate of local recurrence varies from 5 to 15% [3, 5].

Management

Excision is the treatment of choice.

Fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofi broma) [1-4]

Definition and nomenclature

Fibrous histiocytoma is a benign dermal and often superficial subcutaneous proliferation of oval cells resembling histiocytes, and spindle-shaped cells resembling fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Their line of differentiation remains uncertain, but these lesions are descriptively classified as fibrohistiocytic tumours because of the microscopic appearance of the tumour cells. The aetiology of FH is unknown, but cytogenetic studies demonstrating clonality favour these lesions being neoplastic [5, 6]. The neoplastic nature of FH is also suggested by their clinical persistence and by the frequency of local recurrence of some variants (cellular, aneurysmal and atypical; see later) as well as the exceptional metastases (rarely leading to death as a result of disseminated disease) of some tumours (cellular, aneurysmal and atypical and more exceptionally, epithelioid and even ordinary types) [7, 8, 9, 10].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Ordinary fibrous histiocytoma is probably the most common cutaneous soft-tissue tumour. Important clinicopathological variants (cellular, atypical and aneurysmal) are much more uncommon. Cellular FH represents less than 5% of all FHs [11]. Aneurysmal and atypical FHs are less common than the latter.

Age

Most FHs occur in young to middle-aged adults. Cellular, atypical and epithelioid FHs are more common in young adults.

Sex

Ordinary FH is more common in females. Cellular and atypical FHs are more common in males. The other variants are more common in females.

Pathophysiology

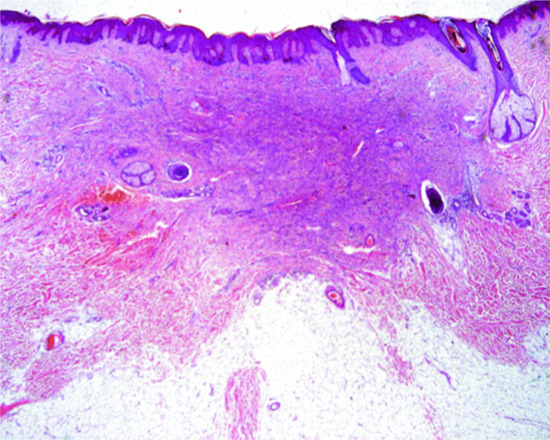

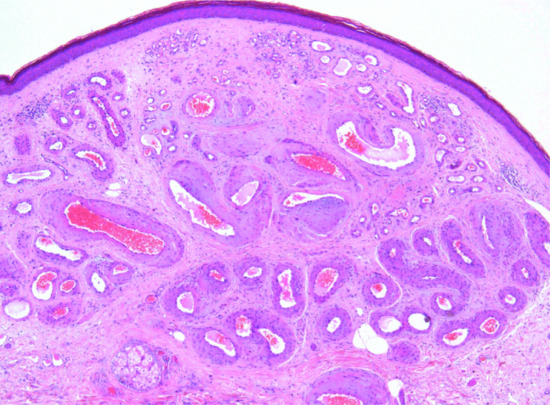

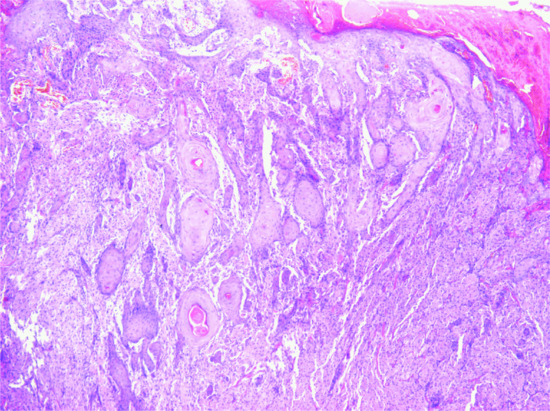

Pathology

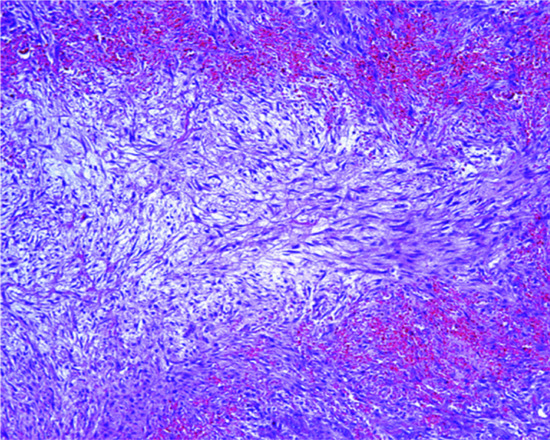

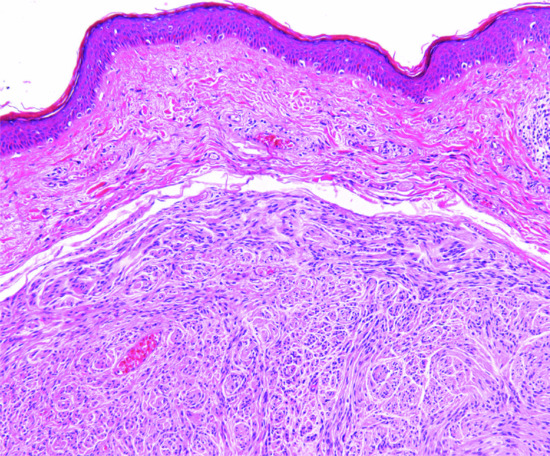

The overlying epidermis frequently shows a degree of epidermal hyperplasia [12] (Figure 137.9). The latter displays different patterns including changes mimicking a squamous papilloma, a seborrhoeic keratosis and lichen simplex chronicus. Occasionally, the epidermal proliferation is associated with immature follicular structures, which are often confused with a basal cell carcinoma. In the dermis, there is a localized proliferation of histiocyte-like cells and fibroblast-like cells, associated with variable numbers of mononuclear inflammatory cells. Foamy macrophages, siderophages and multinucleated giant cells are also variably present. A focal storiform pattern is often seen. The tumour blends with the surrounding dermis. Collagen bundles at the periphery of the lesion are surrounded by scattered tumour cells and appear somewhat hyalinized. Focal myofibroblastic differentiation is often suggested, particularly in the cellular variant. Older lesions show focal proliferation of small blood vessels in association with haemosiderin deposition and fibrosis, hence the older name of ‘sclerosing haemangioma’.

Figure 137.9 Histological appearance of dermatofibroma, showing epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermal sclerotic component.

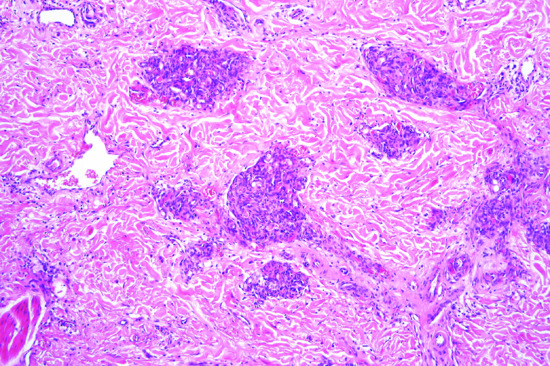

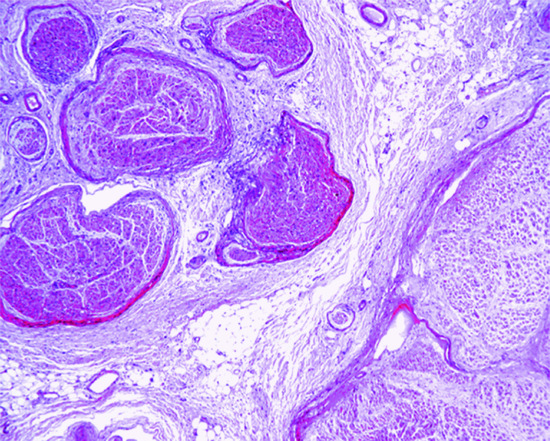

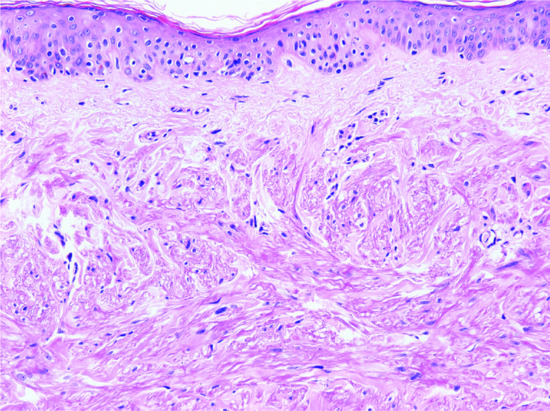

Cellular FH [11] also shows epidermal hyperplasia, but the lesions are more cellular, less polymorphic and consist of bundles of spindle-shaped cells with pink cytoplasm and a focal storiform pattern (Figure 137.10). The mitotic rate varies, and necrosis may be found in up to 12% of cases. Extension into the subcutaneous tissue is more prominent than that seen in ordinary FH. However, the pattern of infiltration is mainly along the septae, and only focally into the subcutaneous lobule in a lace-like pattern. The cellularity and growth pattern often make distinction from DFSP difficult, particularly in small biopsies. DFSP is, however, more monomorphic, tends to infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue diffusely and is generally uniformly positive for CD34. Cellular FH may be focally positive for CD34, but this is predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumour. Staining for FXIIIa is positive in FH and negative in DFSP. Furthermore, cellular FH is often focally positive for smooth muscle actin, whereas this marker is negative in DFSP.

Figure 137.10 Cellular fibrous histiocytoma. Note the increased cellularity, fascicular appearance and focal extension into the subcutis.

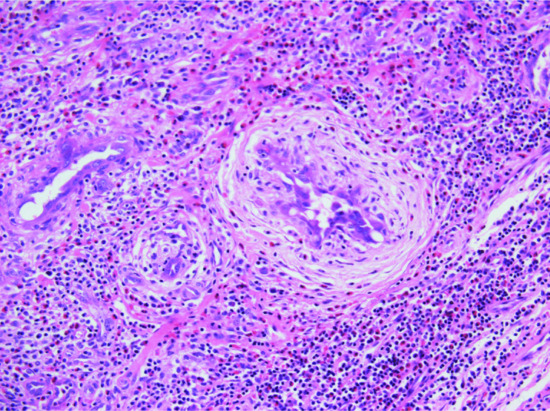

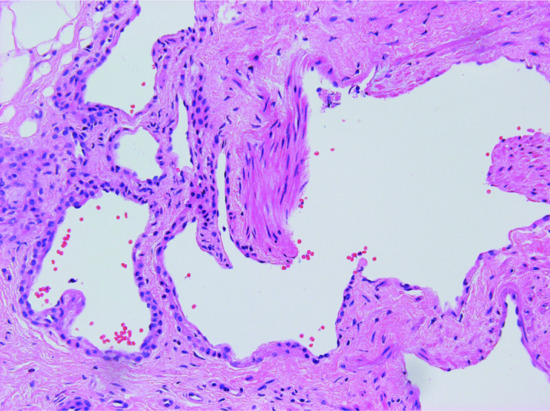

Aneurysmal FH [13, 14] shows extensive haemorrhage, with prominent cavernous-like pseudovascular spaces (Figure 137.11), which are not lined by endothelial cells. The mitotic rate varies, but may be prominent. The background is that of an ordinary FH.

Figure 137.11 Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma. Prominent haemorrhage and cavernous-like spaces obscure the typical background of a fibrous histiocytoma.

Atypical FH [15, 16] shows variable numbers of mono- or multinucleated, pleomorphic, spindle-shaped or histiocyte-like cells on a background of an ordinary FH. These cells may be very prominent, making the histological diagnosis difficult. Mitotic figures, including atypical forms, may be seen. These lesions used to be classified as ‘atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) occurring in non-sun-exposed skin of young patients’.

Epithelioid FH [17, 18] contains a predominant population of cells with abundant pink cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei, and there is often myxoid change and a prominent vascular component. Distinction from a Spitz naevus may be difficult, but in epithelioid FH there is no junctional component, tumour cells are not nested and they are negative for S100.

Many histological variants of FH have been described; recognizing these variants is important to avoid misdiagnosis. They include lesions with palisading granular cell change [19], abundant lipid (ankle-type) [20], clear cell change [21], balloon cell change [22] and keloidal change [23]. The presence of lipid within lesions of FH is not usually associated with systemic lipid abnormalities [24].

Clinical features

History and presentation

Fibrous histiocytoma is commonest on the limbs and appears as a firm papule which is frequently yellow-brown in colour and slightly scaly (Figure 137.12). If the overlying epidermis is squeezed, the ‘dimple sign’ will be seen, indicating tethering of the overlying epidermis to the underlying lesion. Giant lesions (>5 cm in diameter) are occasionally seen [25] and large tumours are more often encountered in some of the variants (see later). Multiple lesions may develop and eruptive variants have been described. The latter may be familial [26], or may be associated with immunosuppression (e.g. HIV) [27], with systemic disease, including autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus and neoplasia, particularly haematological malignancies [28, 29, 30, 31, 32], and even with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [33].

Figure 137.12 Clinical appearance of a fibrous histiocytoma or dermatofibroma.

A number of clinicopathological variants of FH mentioned before have been described, which should be recognized by clinicians and pathologists in order to avoid a misdiagnosis of malignancy. These variants include: cellular FH [11], aneurysmal FH [13, 14], atypical FH (pseudosarcomatous FH, dermatofibroma with monster cells) [15, 16] and epithelioid FH [17, 18]. A further variant, described as ‘atrophic’ [34], may mimic a scar and does not usually pose a problem in differential diagnosis. Rare cases may be ulcerated, erosive or lichenoid [35].

Cellular FH, like ordinary FH, has predilection for the limbs. However, the distribution of age and site is wide; cellular FH is not infrequent in children, and on sites such as the head, neck, fingers and toes. The size of these lesions is also larger than that of ordinary FH. Most cellular FHs are less than 2 cm in diameter, but lesions measuring more than 5 cm may occur. Recognition of this variant is important, because it has a local recurrence rate of 25%, and metastases have been reported anecdotally in a small number of cases [7, 9, 10].

Aneurysmal FH is usually rapidly growing and may attain a very large size. They clinically mimic a vascular tumour. Exceptional tumours are multiple [36]. The rate of local recurrence is 19% [20].

Atypical FH presents as a papule, nodule or plaque, usually less than 1.5 cm in diameter. The rate of local recurrence is around 14%, and exceptional metastases have been reported [23].

Epithelioid FH [24, 25] presents on the limbs of young patients, with a predilection for females. The typical clinical appearance is that of a polypoid, often vascular, lesion resembling a non-ulcerated pyogenic granuloma.

Disease course and prognosis

Ordinary and epithelioid FHs hardly ever recur locally. Cellular FH recurs in 25% of cases, Aneurysmal FH recurs in 19% of cases and atypical FH recurs in 14% of cases. Exceptional metastases have been reported in all clinicopathological variants including ordinary and epithelioid FH. This phenomenon, although exceptional, is more common in cellular, aneurysmal and atypical FHs [7, 8, 9, 10]. In one case of cellular FH, transformation to a pleomorphic sarcoma has been reported [10]. Morphological features do no allow prediction of tumours that will behave in a more aggressive manner [9]. Metastatic tumours are more often associated with chromosomal abnormalities as demonstrated by array comparative genomic hybridization [10, 37]. Fatal tumours are associated with the highest number of chromosomal abnormalities [37].

Management

Most FHs are no more than a cosmetic nuisance, and no treatment is necessary. However, cellular, atypical and aneurysmal variants should be completely removed conservatively, because of the risk of local recurrence and the occurrence of occasional distant metastases.

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumour [1-4,5]

Definition and nomenclature

Plexiform FH is a distinctive predominantly subcutaneous tumour with two distinctive components:

- A fibro/myofibroblastic fascicular component.

- A nodular histiocytic-like component, which also includes giant cells.

Despite its new name, it does not represent a plexiform variant of an ordinary FH (dermatofibroma). An association with cellular neurothekeoma, a tumour that occurs primarily in the dermis, has been suggested based on morphological similarities [5, 6].

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Age

It mainly occurs in children and young adults. An exceptional case has been congenital [7].

Sex

It is most common in females.

Pathophysiology

Pathology [1-4,5]

Low-power examination reveals a predominantly subcutaneous tumour with focal involvement of the dermis and a distinctive plexiform growth pattern. Purely dermal lesions are occasionally seen [8]. Two components are usually identified and consist of fascicles of bland spindle-shaped fibro/myofibroblast-like cells and nodules of histiocyte-like cells with scattered giant cells, focal haemorrhage and haemosiderin deposition. In some tumours, one of the components may predominate. The spindle-shaped cells stain focally for smooth muscle actin, and the cells in the nodules are focally positive for CD68.

Clinical features [1-4,5]

History and presentation

Tumours have a predilection for the upper limbs. The tumour is solitary, measures no more than a few centimetres in diameter and is asymptomatic.

Disease course and prognosis

Local recurrences are observed in up to 30% of cases. Metastases to regional lymph nodes or to the lungs have been reported [1, 3, 9].

Management

Complete surgical excision and follow-up are indicated. Histological features do not predict cases with more aggressive behaviour.

Atypical fibroxanthoma [1,2,3,4]

Definition

Atypical fibroxanthoma, by definition, arises in the sun-damaged skin of elderly people. It is a paradoxical tumour with histological features of a highly malignant neoplasm and low-grade clinical behaviour. Tumours with more aggressive histological features should be diagnosed as dermal pleomorphic sarcoma (see later) [5].

Epidemiology

Age

Most patients are elderly in the seventh to eight decades of life. Tumours in younger patients occur very rarely in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum [6].

Sex

Tumours are much more frequent in males than in females.

Ethnicity

It is a tumour almost exclusively restricted to white people.

Pathophysiology

Predisposing factors

UV radiation-induced p53 mutations have been observed in these lesions, confirming the association with sun-damaged skin [7]. More recently, telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations with UV signature have been identified in AFXs giving further support to the relationship to sun exposure [8].

Pathology