CHAPTER 144

Dermoscopy of Melanoma and Naevi

Natalia Jaimes1 Ashfaq A. Marghoob2

1Dermatology Service, Universidad Pontifi cia Bolivariana and Aurora Skin Cancer Center, Medellín, Colombia

2Dermatology Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

Introduction

The clinical ABCD mnemonic has served well in identifying early melanoma and in differentiating naevi from melanomas. However, many naevi displaying clinically asymmetry, border irregularity, colour variegation or a diameter greater than 5 mm are ‘unnecessarily’ subjected to biopsy. More importantly, some melanomas lack the ABCD features and may escape detection. For example, amelanotic melanomas and melanomas arising in children often do not manifest the classic ABCD features [1, 2]. In fact, some have proposed that the ABCD mnemonic should have a duality with A standing for asymmetry or amelanotic, B for border irregularity or bump (or bleeding bump), C for colour variegation or colour homogeneity (pink or blue) and D for diameter greater than 6 mm or de novo [2]. In addition, since most naevi (at least in adults) are in a state of senescence, the observation of change in a melanocytic neoplasm is regarded as an important sign that may indicate that the lesion is a malignancy. This led to the addition of E to ABCD, with E standing for evolving [3].

However, despite the appreciation of the clinical morphology of naevi and melanomas, it is clear that our diagnostic accuracy remains far from perfect. Fortunately, dermoscopy has proven itself to be a ‘beacon’ in this ‘diagnostic darkness’ [4]. Dermoscopy is now recognized as a useful tool for the evaluation of skin lesions. It increases diagnostic accuracy by up to 30% above that of the unaided eye examination, although this level of improvement is contingent upon gaining expertise in its use [5, 6, 7, 8]. It has been demonstrated that dermoscopy increases sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of skin cancer, in particular melanoma. It allows for the detection of more melanomas at an early stage, while reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies of naevi, thereby improving the malignant to benign biopsy ratio [6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15].

This chapter provides an overview of a dermoscopic approach and evaluation of naevi, in particular those naevi that are frequently subjected to biopsy to rule out melanoma. In addition, this chapter will outline the dermoscopic features of melanoma, according to their histological subtype and anatomical location.

Benign dermoscopic patterns in naevi

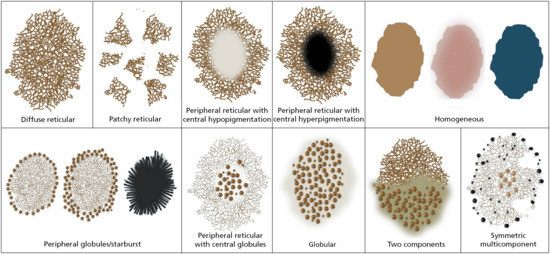

There are a multitude of different types of melanocytic naevi: congenital, speckled lentiginous, naevus spilus, blue, combined, atypical/dysplastic (Clark), intradermal (Unna and Miescher), epithelioid and spindle cell (Spitz/Reed), target (Cockarde), balloon cell, halo, inflamed (Meyerson), recurrent, epidermolysis bullosa naevus, lichen sclerosus naevus and desmoplastic naevus, among others. Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the dermoscopic patterns seen in all of these naevus types, we will outline the patterns seen in the most common naevi encountered in clinical practice that may have morphological features overlapping with those of melanoma. These naevi include atypical or dysplastic naevi, small congenital naevi, blue naevi and Spitz naevi. With that said, one of the main objectives of dermoscopy is to differentiate naevi, in particular atypical or dysplastic naevi, from melanoma [16]. To accomplish this task it is necessary to determine whether the lesion manifests one of the 10 well-defined benign patterns commonly seen in naevi (Figure 144.1). These benign patterns exhibit dermoscopic symmetry in the distribution of colours and structures:

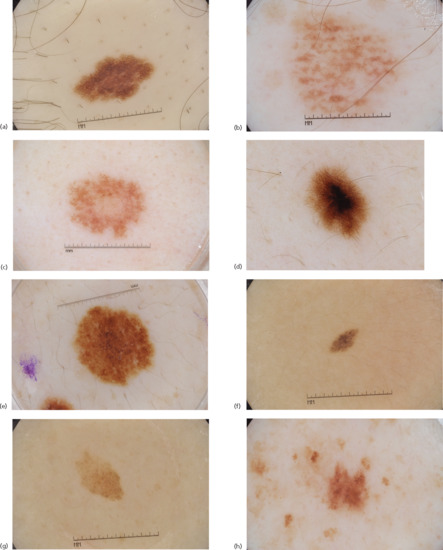

- Reticular diffuse. Diffuse network composed of pigmented lines and hypopigmented holes with minimal variation in their size and colour. The lines of the network tend to be relatively homogeneous in colour, thickness and size and the network tends to fade toward the periphery. This pattern is commonly seen in melanocytic naevi with a prominent junctional component (Figure 144.2a).

- Reticular patchy. This is similar to the pattern described above; however instead of the network being diffusely present throughout the lesion, it is present in focal patches distributed symmetrically within the naevus. These focal patches are separated by homogeneous structureless areas, which are of the same colour or slightly darker than the surrounding normal background skin (Figure 144.2b).

- Peripheral reticular with central hypopigmentation. This pattern has a uniform typical network at the periphery of the lesion with a central homogeneous and hypopigmented structureless area. The structureless area has the same colour or is slightly darker than the surrounding normal background skin. This pattern is commonly seen in acquired melanocytic naevi, especially in individuals with fair skin (Figure 144.2c).

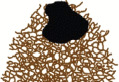

- Peripheral reticular with central hyperpigmentation. This pattern displays a uniform typical network at the periphery of the lesion with a central homogeneous and hyperpigmented structureless area or blotch. This pattern is commonly seen in acquired melanocytic naevi, especially in individuals with darker skin (Figure 144.2d).

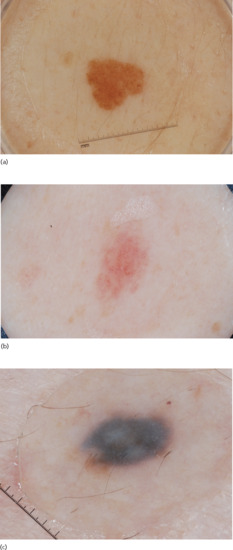

- Homogeneous. This pattern reveals a diffuse homogeneous structureless pattern. It may appear as grey-blue as seen in blue naevi (note that this pattern can also be seen in epidermotropic metastatic melanoma), brown as seen in congenital naevi, or tan-pink as seen in acquired naevi in individuals with fair skin (Figure 144.3).

- Peripheral globules with central network or homogeneous area, including the starburst pattern. This pattern correlates with the active radial growth phase of some naevi. In these lesions the central component consists of a reticular or homogeneous pattern. The peripheral component can manifest in one of three ways: (i) as a single row of globules as seen in some actively growing dysplastic naevi; (ii) as multiple rows of globules (i.e. tiered globules) creating a starburst pattern as commonly seen in Spitz naevi or in dysplastic naevi with spitzoid features; and (iii) as streaks (classic starburst pattern) giving the appearance of an exploding star as seen in Spitz/Reed naevi (Figure 144.4).

- Peripheral reticular with central globules. This pattern reveals a uniform typical network at the periphery of the lesion with central globules. This pattern is commonly seen in naevi with a congenital pattern on histology (Figure 144.2e).

- Globular. In this pattern there are globules of similar shape, size and colour distributed throughout the lesion. Globules may be large and angulated, creating a cobblestone pattern as seen in some congenital naevi (Figure 144.2f).

- Two-component. In these lesions there is a combination of two patterns with one half of the lesion manifesting one pattern and the other half another pattern. The most common two-component pattern is the reticular–globular pattern (Figure 144.2g).

- Multicomponent. Here there is a combination of three or more patterns and/or structures distributed symmetrically in at least one axis (Figure 144.2h).

Figure 144.1 Dermoscopic naevi patterns.

Figure 144.2 (a) Reticular diffuse naevus. (b) Reticular patchy naevus. (c) Peripheral reticular with central hypopigmentation naevus. (d) Peripheral reticular with central hyperpigmentation naevus. (e) Peripheral reticular naevus with central globules. (f) Naevus with globular pattern. (g) Two-component pattern naevus. (h) Multicomponent pattern naevus.

Figure 144.3 Homogeneous pattern naevi: (a) homogeneous brown; (b) homogeneous pink; and (c) homogeneous grey-blue.

Figure 144.4 Naevi with peripheral globules: (a) growing naevus with a single row of globules; (b) Spitz naevus with multiple rows of globules; and (c) Spitz naevus with streaks giving the appearance of an exploding star.

It is interesting to note that most patients tend to manifest a predominant naevus pattern with one or two of the above-mentioned patterns being displayed in most of their naevi [17, 18]. This knowledge can facilitate finding a melanoma within a sea of many naevi. The outlier lesion that manifests a dermoscopic pattern differing from the predominant naevus pattern may be one that deserves closer scrutiny and perhaps biopsy. Lesions manifesting the same pattern as the predominant naevus pattern can be safely monitored [19]. Another observation that is worth mentioning is that the naevus pattern and observed dynamic changes seen in naevi are strongly dependent on patient-related factors including age, anatomical location, Fitzpatrick skin type, personal history of melanoma, UV light exposure and pregnancy [20].

Dermoscopy of melanoma

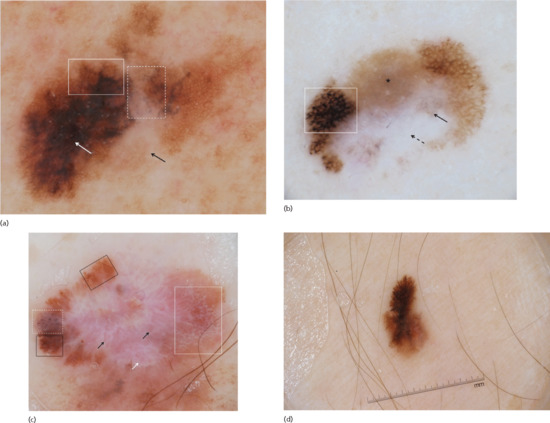

While naevi tend to manifest one of the 10 aforementioned benign patterns, melanomas almost always manifest a pattern that deviates from those depicted in Figure 144.1 [21, 22, 23]. In fact, melanomas can manifest a wide range of dermoscopic characteristics, which may vary depending on factors such as anatomical location, histopathological subtype, growth phase and tumour thickness, and may even depend on specific genetic mutations present within the tumour. With that said, most melanomas developing on non-glabrous skin are of the superficial spreading subtype (SSM), and tend to reveal three or more colours (i.e. brown, black, red, white and/or blue-grey) and at least one of the 10 melanoma-specific structures listed in Table 144.1 (Figure 144.5):

- Atypical network (including angulated lines creating polygonal structures).

- Negative network.

- Streaks.

- Crystalline structures.

- Atypical dots/globules.

- Atypical blotch (off pigment).

- Regression structures.

- Blue-white veil over raised areas.

- Atypical vascular structures.

- Peripheral tan structureless areas.

Table 144.1 Melanoma-specific structures

| Dermoscopic structure | Definition | Schematic illustration |

| Atypical pigment network | Increased variability in the width of the network lines, their colour and distribution. The hole sizes also have increased variability. The network can appear broken up (non-contiguous) appearing as branched streaks, and the network may end abruptly at the periphery [54] |  |

| Angulated lines | Angulated lines creating a zig-zag pattern or coalescing to create polygonal structures such as rhomboids [55] |  |

| Negative pigment network | Serpiginous interconnecting hypopigmented lines, which surround irregularly shaped pigmented structures that resemble elongated curvilinear globules. It can be seen diffusely throughout the lesion or focally and asymmetrically located within the lesion |  |

| Streaks (i.e. pseudopods and radial streaming) | Radial projections located at the periphery of the lesion, which extend from the tumour toward the surrounding normal skin. The presence of irregular, asymmetrical and focally distributed streaks are highly suggestive of melanoma [56] Pseudopods are finger-like projections with small knobs at their tips, whereas radial streaming are the same structures without the knobs. Since both structures represent confluent junctional nests of melanocytes, they are now both categorized under the term streaks |

|

| Crystalline structures | Shiny white, linear streaks that are often orientated parallel or orthogonal to each other [57]. Also known as shiny white streaks or lines |  |

| Atypical dots or globules | Dots are small, round structures, which may be black, brown and/or blue-grey in colour. In melanoma dots vary in size, colour and distribution, tending to be located towards the periphery of the lesion, and are not associated with the pigmented network lines Globules consist of well-demarcated, round to oval structures that may be brown, black, blue and/or white in colour. Globules are larger than dots. In melanoma they are usually multiple and of differing sizes, shapes and colours. They are often asymmetrically and/or focally distributed within the lesion |

|

| Off centre blotch or multiple asymmetrically located blotches | Dark-brown to black, usually homogenous areas with varying hues of pigment that obscure visualization of any other structures. In melanoma, blotches are asymmetrically and/or focally located towards the periphery of the lesion or can present as multiple blotches. Eccentric peripheral hyperpigmentation is often found in melanoma [58] |  |

| Regression structures (white scar-like depigmentation and/or blue-grey granularity or peppering overlying macular areas and not associated with vessels) | Regression structures consist of granularity (also known as peppering) and scar-like areas. When both are present together, it gives the appearance of a blue-white veil over a macular area [59]. In melanoma, regression structures tend to be asymmetrically located and often involve more than 50% of the lesion's surface area |  |

| Blue-white veil overlying raised areas | Confluent blue pigmentation of varying hues with an overlying white ‘ground glass’ haze, which tend to be asymmetrically located or diffusely present throughout the lesion |  |

| Atypical vascular structures | Dotted vessels over milky-red background Serpentine vessels: linear and irregular vessels Polymorphous vessels: two or more vessel morphologies within the same lesion Corkscrew vessels: usually seen in nodular melanoma, desmoplastic melanoma, or melanoma metastases |

|

| Peripheral tan structureless areas | Structureless light brown area/s located at the periphery of the lesion and encompassing more than 10% of a lesion's surface area [48] |  |

Figure 144.5 (a) Dermoscopic image of a melanoma on the lower back revealing an atypical network (solid box), regression structures including granularity and scar-like depigmentation (dashed box), peripheral tan structureless area (black arrow) and atypical blotch area (white arrow). (b) Dermoscopic image of a melanoma located on the leg with an atypical network (solid box) and regression structures (arrows), with the solid arrow pointing to granularity/peppering and the dashed arrow pointing to scar-like depigmentation. The lesion also has a peripheral tan structureless area (asterisk). (c) Dermoscopic image of a melanoma located on the abdomen, with an atypical network (black solid boxes), atypical globules (white dashed box), negative network (white solid box), scar-like areas (white arrow) and atypical vessels including serpentine, dotted and irregular hairpin vessels (black arrows). (d) Dermoscopic image of a melanoma located on the thigh with atypical peripheral streaks (i.e. radial streaming).

Melanoma-specific structures are those dermoscopic structures that have demonstrated a heightened odds ratio for melanoma.

Unlike SSM, which is the most common melanoma subtype on non-glabrous skin, lentigo maligna is the most common melanoma subtype on facial and chronic sun-damaged skin. Although melanomas on the face and on chronically sun-damaged skin can reveal any of the above-mentioned melanoma-specific structures. They more frequently display a different set of dermoscopic structures. These include slate-grey dots/granules surrounding adnexal openings, asymmetrical grey pigment surrounding follicular openings, angulated lines forming rhomboidal structures and pigment blotches distributed in an asymmetrical fashion (Table 144.2; Figure 144.6) [24, 25]. Concentric pigmented rings encircling each other (concentric isobar pattern or circle within a circle) can also be seen in lentigo maligna [26].

Table 144.2 Melanoma structures seen on facial or on sun-damaged skin

| Dermoscopic structure | Definition | Schematic illustration |

| Perifollicular granularity | Dots aggregated around adnexal openings [24] |  |

| Asymmetrical grey perifollicular openings | Dots or grey pigment aggregated around hair follicles in an asymmetrical fashion [24]. This asymmetrical distribution often creates a crescent shape around the hair follicles |  |

| Angulated lines | Brown to bluish grey dots and/or lines arranged in an angulated linear pattern creating a zig-zag pattern or coalescing to create polygonal structures such as rhomboids [55] |  |

| Rhomboidal structures | Hyperpigmented brown and grey lines surrounding hair follicles and creating shapes like rhomboids [24] |  |

| Follicle obliteration | Rhomboidal structures become broader, obliterating hair follicles [24] |  |

| Circle within a circle (isobar pattern) | Concentric pigmented rings encircling each other [26] |  |

Figure 144.6 (a) Dermoscopic image of a lentigo maligna located on the nose with perifollciular granularity and asymmetrical grey perifollicular openings (solid box), polygonal structures (dashed box), rhomboidal structures (solid arrows) and circle within a circle (arrowheads). (b) Dermoscpic image of a melanoma located on chronic sun-damaged skin on the shoulder, revealing perifollicular granularity and asymmetrical grey perifollicular openings (solid box) and polygonal structures (white arrow).

While most melanomas manifest at least one of the melanoma-specific structures discussed above (Tables 144.1 and 144.2), some melanomas manifest a non-specific pattern including lesions that are structureless or featureless and these melanomas may be missed, especially during the initial evaluation [27, 28, 29, 30]. These dermoscopically non-diagnostic lesions, especially if they are clinical or dermoscopic outliers (ugly duckling), should raise suspicion for melanoma. The options of management for these non-specific lesions (including featureless or structureless lesions) include performing a biopsy, utilizing in vivo confocal microscopy to further analyse the lesion and determine if it is malignant or not, or, if the lesion is macular, to subject it to digital surveillance [31]. Digital surveillance can effectively be accomplished via short-term digital dermoscopic monitoring (STM), which compares dermoscopic images of the same lesion taken 3–4 months apart [28, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35]. STM should only be performed on macular lesions (nodular lesions should never be subjected to STM) and by those with experience in using the technique [34]. The rationale behind digital surveillance of macular lesions is that stable lesions are considered biologically indolent and thus benign, whereas changing lesions are biologically dynamic and up to 18% of these dermoscopically changing lesions will prove to be melanomas [30, 34, 35]. Flat lesions lend themselves to STM because, even if they prove to be early melanomas, their rate of growth is generally slow enough that a 3–4 month delay will not adversely impact prognosis [28, 30, 36]. Lesions found to have any morphological change on STM, with the exception of changes in the overall global colour or in the number of milia-like cysts, should be biopsied to rule out a melanoma [30]. Melanomas on non-glabrous skin (usually SSM subtype) will most often reveal changes within 3 months of monitoring. In contrast, up to 25% of lentigo maligna on the face and chronic sun-damaged skin evolve very slowly and thus it is recommended that the monitoring interval be extended for these lesions to between 6 and 12 months [35].

Melanomas in special locations

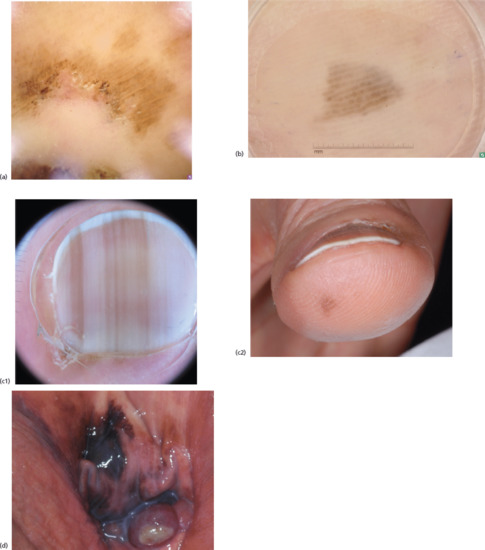

Acral melanoma (volar surfaces of the palms and soles)

Melanomas located on volar surfaces may possess any of the melanoma-specific structures listed in Table 144.1. However, most do not display any of these structures but instead reveal the features listed in Table 144.3. The most frequent melanoma subtype found on volar surfaces is the acrolentiginous type. During the dermoscopic evaluation of lesions on the palms and soles it is imperative to identify the furrows and ridges of the dermatoglyphics, since pigment located on the ridges anywhere within the lesion (i.e. parallel ridge pattern) is highly suggestive of melanoma (Table 144.3; Figure 144.7a, b). Clues to assist in recognizing the ridges include:

- The ducts of the eccrine glands open on the surface of the skin overlying the ridges, and are seen as tiny white dots aligned in rows.

- Ridges are wider than the furrows.

- The ink test, described by Braun et al. [37] and Uhara et al. [38], in which ink applied to the skin highlights the furrows and ridges and even the eccrine openings.

Table 144.3 Melanoma structures in acral melanoma (melanomas on volar skin)

| Dermoscopic structure | Definition | Schematic illustration |

| Parallel ridge pattern | Pigmentation located on the ridges of palms and soles [39] |  |

| Irregular diffuse pigmentation | Irregular, diffuse pigmentation with different shades of tan, brown, black and/or grey [39] |  |

| Irregular fibrillar pattern | Any fibrillar pattern on the palms, or fibrillar pattern on the soles that revels an increased variability in the thickness or colours of the lines. Line colour other than brown is also considered atypical |  |

| Large-diameter lesion | Newly acquired lesion greater than 7–10 mm in diameter, especially in individuals over the age of 50 years |

Figure 144.7 (a, b) Dermoscpic images of melanomas located on the soles with a parallel ridge pattern. (c) Dermoscopic image (c1) of a melanoma, 0.6 mm in thickness, involving the nail unit with multiple, longitudinal, irregular, brown bands with irregular spacing and thickness and the micro-Hutchinson sign. Also present is irregular pigmentation on the hyponychium (clinical image, c2). (d) A vaginal melanoma, demonstrating the presence of blue, grey and white colours within the lesion, and a multicomponent pattern composed by irregular brown-black globules and blue-white veil.

The presence of a parallel ridge pattern has a diagnostic accuracy of 82% for melanoma, with a sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 99%, a positive predictive value of 94% and a negative predictive value of 98% [39, 40]. Exceptions to the ridge pattern exist with some benign lesions manifesting a parallel ridge pattern, for example some congenital naevi and lesions seen in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, Laugier–Hunziker syndrome, subcorneal haemorrhage and ethnic pigmentation. In contrast to melanoma, most naevi reveal patterns with pigment predominantly located in the dermatoglyphic furrows (i.e. parallel furrow and lattice-like patterns).

Besides the parallel ridge pattern, melanomas on volar skin can have a homogeneous pattern displaying multiple shades of brown and/or other colours such as black, red, white, grey and blue [39, 41]. In addition, any lesion on the palms that reveals a fibrillar pattern should be viewed with suspicion (see Table 144.3). In contrast, the fibrillar pattern is quite common in melanocytic neoplasms on the soles; in naevi on the soles, the fibrillar pattern tends to be brown in colour with thin and regular lines, while in melanoma the lines have increased variability in thickness, spacing and colour [42].

Lastly, if the volar lesion does not reveal any of the aforementioned diagnostic features, management will need to rely on the maximal diameter of the lesion. Lesions greater than 7–10 mm in diameter should be considered for biopsy, especially in patients older than 50 years; whereas lesions smaller than 7–10 mm in diameter can either be biopsied or digitally monitored as previously described [43].

Melanoma involving the nail unit

Evaluating melanonychia striata requires inspection not only of the nail plate, but also of the cuticle, paronychium and hyponychium. Pigment on any of these three latter sites, in association with an acquired melanonychia striata, is highly suggestive of melanoma (Table 144.4; Figure 144.7c). Performing dermoscopy on the cuticle may reveal pigment within the skin of the cuticle that is otherwise not visible to the unaided eye and this is known as the micro-Hutchinson sign. The micro-Hutchinson sign needs to be differentiated from the pseudo-Hutchinson sign, which is the reflection of pigment in the nail matrix visible through relatively translucent cuticular skin, and which has no diagnostic significance. Pigment on the hyponychium should be evaluated in the same manner as described for acral/volar melanomas. For example, pigmentation on the hyponychium with a parallel ridge pattern would be highly suggestive for melanoma (see Table 144.3; Figure 144.7).

Table 144.4 Melanoma-specific structures of the nail unit

| Dermoscopic structure | Definition | Schematic illustration |

| Hyponychial pigment with any features described in Table 144.3 | Irregular pigmentation on the distal periungueal skin, with any of the features associated with melanomas on acral skin |  |

| Hutchinson or micro-Hutchinson sign | Pigmentation of the proximal nail fold that can be seen with the naked eye (Hutchinson) or only with dermoscopy (micro-Hutchinson) |  |

| Triangular shape | Width of the melanonychia striata is wider at the proximal end of the nail plate |  |

| Irregular band pattern | Multiple, longitudinal, irregular bands of different colours (i.e. black, brown, grey) with irregular spacing, thickness and disruption of parallelism |  |

| Nail dystrophy | Complete or partial nail destruction, and/or absence of the nail plate |  |

Some have suggested applying dermoscopy directly to the nail matrix and nail bed after nail avulsion [44]. While this may help in identifying nail matrix melanoma, it is not a practical method for the routine evaluation of melanonychia striata. Instead, dermoscopic examination of the nail plate, which allows for the evaluation of pigmented nail bands that together form the melanonychia striata lesion, can provide valuable, albeit indirect, clues regarding the nature of the nail matrix lesion. Examination of the melanonychia striata should include the following (Table 144.4):

- Measurement of the width of the nail plate pigmentation at both the proximal and distal ends of the nail plate. A wider diameter at the proximal end, resulting in a triangular shape to the melanonychia striata, can be seen in rapidly growing tumours, including melanomas [41].

- Evaluation of the individual striations/bands present within the melanonychia striata. Benign lesions are characterized by a regular parallel pattern consisting of parallel lines spaced at regular intervals with minimal variation in their colour or thickness. The colour of the lines tends to get lighter towards the lateral edges. In contrast, melanomas are associated with an irregular pattern consisting of multiple longitudinal lines, of differing colours (i.e. brown, black, grey) and thickness, as well as irregular spacing and disruption of parallelism [41].

Melanomas that are in advanced stages can cause nail plate dystrophy or destruction [41]. Melanoma-specific structures of the nail unit are listed in Table 144.4.

Mucosal melanoma

Mucosal melanomas include those located on the glabrous portion of the lips, oral cavity and anogenital areas. While clinically it may be impossible to distinguish between melanosis and melanoma, dermoscopy can provide some assistance [45]. It has been shown that mucosal melanomas often reveal a multicomponent pattern composed of irregular brown-black dots, blue-white veil, atypical vessels and/or a negative network [46]. Other dermoscopic structures described in mucosal melanomas include focal areas of pigment network, globules, parallel structures (linear streaks of pigment, also known as ‘hyphae’ structures), or ring-like structures (arciform structures or incomplete circles, also known as ‘fish scale-like’ structures) (see Figure 144.7d). The presence of multiple patterns and colours are associated with more advanced melanomas; whereas structureless areas and grey colour are more frequently seen in early melanomas [47]. In a large study regarding the dermoscopic morphology of mucosal melanoma, the authors concluded that the most sensitive and specific feature to help distinguish melanoma from non-melanoma were the colours expressed by the lesion, with blue, grey or white colours being the strongest factors that facilitated the differentiation between malignant and benign lesions (sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 64% for melanoma) [47]. In addition, structureless areas were also significantly associated with malignant lesions. In fact, the combination of one of the three aforementioned colours (i.e. blue, grey, white) and structureless areas were found to be highly predictive of melanoma with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 82% (see Figure 144.7e) [47].

Other melanoma variants

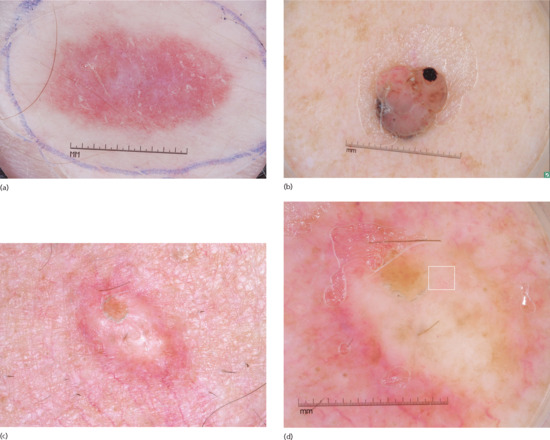

Amelanotic melanoma

Amelanotic melanomas (AMs) account for 2–8% of all melanomas and are defined as melanomas that lack clinically apparent pigmentation. Clinical AMs may, under dermoscopy, reveal subtle focal, brown to tan hues. Thus, with dermoscopy these clinically amelanotic malignancies can be further categorized into those melanomas that do not display any discernable pigment (i.e. pure AMs) and those that display low levels of eumelanin (i.e. hypomelanotic melanomas) [1].

Any melanoma subtype can present as an amelanotic variant, however nodular melanomas are the most common subtype to present with no pigment (Figure 144.8b). These amelanotic nodular melanomas tend to appear as symmetrical, rapidly growing, pink papules. AMs that are not of the nodular subtype tend to present as erythematous patches, with a round to oval symmetrical morphology. Epidermal changes such as scale and disruption of skin markings are also evident in the majority of cases. With dermoscopy, vascular structures are the main and most commonly observed features, in particular serpentine or lineal irregular vessels, milky-red areas and dotted vessels. In fact, these vascular structures may be the only clues for the diagnosis of AMs (Figure 144.8a) [1]. Other structures that may be observed with polarized light dermoscopy are crystalline structures (see Table 144.1). In addition, peripheral, light brown structureless areas can be observed in hypomelanotic melanomas. These structureless areas have been associated with thin melanomas with a 93.8% positive predictive value for melanoma [48]. In one study on amelanotic and hypomelanotic melanomas, the most predictive structures for melanoma were the presence of predominantly centrally located vessels, milky red-pink areas, more than one shade of pink and polymorphous vascular pattern, in particular the presence of dotted and linear irregular (serpentine) vessels within the same lesion [49].

Figure 144.8 (a) Dermoscopic image of an amelanotic melanoma that is not of the nodular subtype, showing serpentine vessels, dotted vessels and vascular blush throughout the lesion. (b) Dermoscopic image of a nodular, amelanotic melanoma displaying atypical vessels (i.e. serpentine and hairpin vessels) within pseudo-lagoons characterized by pink lacuna-like structures that are not separated from each other by septae. (c) Clinical image of a pure desmoplastic melanoma, Breslow thickness of 6.1 mm. (d) Dermoscopic image of the same melanoma showing subtle dotted vessels (box). A biopsy was performed revealing a 6.1 mm pure desmoplastic melanoma with no associated epidermal component.

Nodular melanoma

Nodular melanomas (NMs) comprise up to 30% of all melanomas. These melanomas are characterized by their lack of significant intraepidermal component and rapid tumour growth [50]. Clinically, NMs present as firm papules or nodules, with a relatively symmetrical morphology and pigmentation pattern, and not uncommonly as an amelanotic papule (up to 37% of cases) [50]. On dermoscopy, pure NMs do not have any pigment network, pseudo-network or regression structures (Figure 144.8b) [50, 51]. Pigmented NMs tend to reveal areas of homogeneous blue pigmentation, blue-white veil, crystalline structures, pink or black colours and irregular blotches. NMs can also display atypical dots or globules, in particular black ones at the periphery (odds ratio 28).

In addition, atypical vascular structures, including milky-red areas and atypical vessels with large diameters (most frequently linear irregular/serpentine vessels and hairpin vessels in a pink background), are important clues for NMs, in particular nodular amelanotic melanomas. These amelanotic NMs often also display crystalline structures when viewed with polarized light dermoscopy. For pigmented nodular lesions the presence of blue-black pigmented areas involving at least 10% of the lesion carries with it 78% sensitivity and 80.5% specificity for melanoma [52]. Some NMs may present with pseudo-lagoons, which are characterized by red lacunae-like structures that are not separated from each other by septae, as is the norm for haemangiomas. In addition, some of these lacunae-like structures will have small vessels meandering through them (Figure 144.8b) [51]. One study analysing the features of thin NMs found that these thinner NMs often presented with a homogeneous or featureless pattern with disorganized and asymmetrical distribution of pigment [51].

Desmoplastic melanoma

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is a rare variant of melanoma, accounting for less than 4% of all melanomas. Based on the extent of desmoplasia present in the invasive component, DM can be further subclassified into pure and mixed. This classification appears to have prognostic and therapeutic implications. For example, pure DM (pDM) is less likely to have regional lymph node involvement and is associated with a more favourable outcome. In contrast, mixed DM (mDM) has been associated with higher loco-regional recurrences. Clinically, pDM and mDM may be indistinguishable; they often present as palpable or indurated lesions on sun-exposed areas of older males and often reveal features commonly associated with banal lesions. Therefore, it is not uncommon for the definitive diagnosis of DM to be delayed (Figure 144.8c).

Dermoscopy provides clues and information that may help identify DM or at least prompt a biopsy in these otherwise clinically banal-appearing lesions. Usually, dermoscopic findings in DMs reveal at least one melanoma-specific structure, most commonly atypical vascular structures and regression structures (i.e. granularity and scar-like areas), blue-white veil, atypical globules, atypical network and crystalline structures (Figure 144.8d) [53]. Granularity (also known as peppering) is the most common structure, and is more frequent in pDM than mDM. Since pDM lack an associated epidermal non-DM component, they are extremely difficult to detect while thin. On the other hand, mDM may be easier to detect based on their association with non-DM. The most common non-DM associated with mDM is lentigo maligna. It is because of this association that the authors recommend that all suspect lentigo maligna lesions be palpated to ensure that there is no subcutaneous firmness associated with them [53].

References

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, Marghoob AA. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:591–6.

- Cordoro KM, Gupta D, Frieden IJ, McCalmont T, Kashani-Sabet M. Pediatric melanoma: results of a large cohort study and proposal for modified ABCD detection criteria for children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:913–25.

- Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: revisiting the ABCD criteria. JAMA 2004;292:2771–6.

- Roesch A, Burgdorf W, Stolz W, Landthaler M, Vogt T. Dermatoscopy of “dysplastic nevi”: a beacon in diagnostic darkness. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:479–93.

- Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, Kopf AW, Saurat JH. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:109–21.

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol 2002;3:159–65.

- Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. I. Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:571–83.

- Benvenuto-Andrade C, Marghoob AA. Ten reasons why dermoscopy is beneficial for the evaluation of skin lesions. Exp Rev Dermatol 2006;1:369–74.

- Noor O, Nanda A, Rao BK. A dermoscopy survey to assess who is using it and why it is or is not being used. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:951–2

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:683–9.

- Argenziano G, Puig S, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy improves accuracy of primary care physicians to triage lesions suggestive of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1877–82.

- Carli P, Mannone F, De Giorgi V, Nardini P, Chiarugi A, Giannotti B. The problem of false-positive diagnosis in melanoma screening: the impact of dermoscopy. Melanoma Res 2003;13:179–82.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the “dermoscopy era”: a retrospective study 1997–2001. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:687–92.

- Bafounta ML, Beauchet A, Aegerter P, Saiag P. Is dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) useful for the diagnosis of melanoma? Results of a meta-analysis using techniques adapted to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1343–50.

- Dal Pozzo V, Benelli C, Roscetti E. The seven features for melanoma: a new dermoscopic algorithm for the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol 1999;9:303–8.

- Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:679–93.

- Scope A, Burroni M, Agero AL, et al. Predominant dermoscopic patterns observed among nevi. J Cutan Med Surg 2006;10:170–4.

- Wazaefi Y, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Avril MF, et al. Evidence of a limited intra-individual diversity of nevi: intuitive perception of dominant clusters is a crucial step in the analysis of nevi by dermatologists. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2355–61.

- Argenziano G, Catricala C, Ardigo M, et al. Dermoscopy of patients with multiple nevi: improved management recommendations using a comparative diagnostic approach. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:46–9.

- Zalaudek I, Schmid K, Marghoob AA, et al. Frequency of dermoscopic nevus subtypes by age and body site: a cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:663–70.

- Marghoob AA, Korzenko AJ, Changchien L, Scope A, Braun RP, Rabinovitz H. The beauty and the beast sign in dermoscopy. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:1388–91.

- Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Blum A, Wolf IH, et al. Dermoscopic classification of atypical melanocytic nevi (Clark nevi). Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1575–80.

- Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Blum A, Wolf IH, et al. Dermoscopic classification of Clark's nevi (atypical melanocytic nevi). Clin Dermatol 2002;20:255–8.

- Schiffner R, Schiffner-Rohe J, Vogt T, et al. Improvement of early recognition of lentigo maligna using dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:25–32.

- Schiffner R, Perusquia AM, Stolz W. One-year follow-up of a lentigo maligna: first dermoscopic signs of growth. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:1087–9.

- Cognetta AB, Jr, Stolz W, Katz B, Tullos J, Gossain S. Dermatoscopy of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Clin 2001;19:307–18.

- Kittler H, Binder M. Follow-up of melanocytic skin lesions with digital dermoscopy: risks and benefits. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1379.

- Kittler H, Guitera P, Riedl E, et al. Identification of clinically featureless incipient melanoma using sequential dermoscopy imaging. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:1113–19.

- Skvara H, Teban L, Fiebiger M, Binder M, Kittler H. Limitations of dermoscopy in the recognition of melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:155–60.

- Menzies SW, Gutenev A, Avramidis M, Batrac A, McCarthy WH. Short-term digital surface microscopic monitoring of atypical or changing melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1583–9.

- Guitera P, Pellacani G, Crotty KA, et al. The impact of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy on the diagnostic accuracy of lentigo maligna and equivocal pigmented and nonpigmented macules of the face. J Invest Dermatol 2010;130:2080–91.

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Follow-up of melanocytic skin lesions with digital epiluminescence microscopy: patterns of modifications observed in early melanoma, atypical nevi, and common nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:467–76.

- Robinson JK, Nickoloff BJ. Digital epiluminescence microscopy monitoring of high-risk patients. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:49–56.

- Argenziano G, Mordente I, Ferrara G, Sgambato A, Annese P, Zalaudek I. Dermoscopic monitoring of melanocytic skin lesions: clinical outcome and patient compliance vary according to follow-up protocols. Br J Dermatol 2008;159:331–6.

- Altamura D, Avramidis M, Menzies SW. Assessment of the optimal interval for and sensitivity of short-term sequential digital dermoscopy monitoring for the diagnosis of melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:502–6.

- Liu W, Dowling JP, Murray WK, et al. Rate of growth in melanomas: characteristics and associations of rapidly growing melanomas. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:1551–8.

- Braun RP, Thomas L, Kolm I, French LE, Marghoob AA. The furrow ink test: a clue for the dermoscopic diagnosis of acral melanoma vs nevus. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1618–20.

- Uhara H, Koga H, Takata M, Saida T. The whiteboard marker as a useful tool for the dermoscopic “furrow ink test”. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:1331–2.

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1233–8.

- Saida T, Oguchi S, Miyazaki A. Dermoscopy for acral pigmented skin lesions. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:279–85.

- Phan A, Dalle S, Touzet S, Ronger-Savle S, Balme B, Thomas L. Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:765–71.

- Altamura D, Altobelli E, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, Peris K. Dermoscopic patterns of acral melanocytic nevi and melanomas in a white population in central Italy. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:1123–8.

- Koga H, Saida T. Revised 3-step dermoscopic algorithm for the management of acral melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:741–3.

- Hirata SH, Yamada S, Enokihara MY, et al. Patterns of nail matrix and bed of longitudinal melanonychia by intraoperative dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:297–303.

- Jaimes N, Halpern AC. Practice gaps. Examination of genital area: comment on “Dermoscopy of pigmented lesions of the mucosa and the mucocutaneous junction”. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:1187–8.

- Ferrari A, Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented lesions of the vulva: a retrospective morphological study. Dermatology 2011;222:157–66.

- Blum A, Simionescu O, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented lesions of the mucosa and the mucocutaneous junction: results of a multicenter study by the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Arch Dermatol 2011;147:1181–7.

- Annessi G, Bono R, Sampogna F, Faraggiana T, Abeni D. Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of three dermoscopic algorithmic methods in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic lesions: the importance of light brown structureless areas in differentiating atypical melanocytic nevi from thin melanomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:759–67.

- Menzies SW, Kreusch J, Byth K, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of amelanotic and hypomelanotic melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1120–7.

- Menzies SW, Moloney FJ, Byth K, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of nodular melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:699–709.

- Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:311–18.

- Argenziano G, Longo C, Cameron A, et al. Blue-black rule: a simple dermoscopic clue to recognize pigmented nodular melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1251–5.

- Jaimes N, Chen L, Dusza SW, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of desmoplastic melanomas. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:413–21.

- Salopek TG, Kopf AW, Stefanato CM, Vossaert K, Silverman M, Yadav S. Differentiation of atypical moles (dysplastic nevi) from early melanomas by dermoscopy. Dermatol Clin 2001;19:337–45.

- Slutsky JB, Marghoob AA. The zig-zag pattern of lentigo maligna. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:1444.

- Pizzichetta MA, Stanganelli I, Bono R, et al. Dermoscopic features of difficult melanoma. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:91–9.

- Marghoob AA, Cowell L, Kopf AW, Scope A. Observation of chrysalis structures with polarized dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:618.

- Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Blum A, Wolf IH, et al. Dermoscopic classification of atypical melanocytic nevi (Clark nevi). Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1575–80.

- Braun RP, Gaide O, Oliviero M, et al. The significance of multiple blue-grey dots (granularity) for the dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:907–13.