CHAPTER 154

The Skin and Disorders of the Musculoskeletal System

Christopher R. Lovell

Department of DermatologyRoyal United Hospital and Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, UK

Introduction

Combined clinics with rheumatology provide a valuable tertiary referral service for patients with complex disease, as well as enhancing the work-related quality of life for the dermatologist. A combined therapeutic approach can be beneficial for the patient with psoriatic arthritis. Both dermatologists and rheumatologists can learn from each other in the management of autoimmune connective tissue diseases, such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, systemic sclerosis and the vasculitides. A patient with an inborn error of matrix protein synthesis, such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, may present to either discipline. These disorders are discussed fully in other chapters. This chapter examines some other conditions where skin lesions and arthropathy play a major part. These include infections, metabolic disorders such as gout, inflammasome disorders and infiltrative conditions such as multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. In addition, this chapter explores cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid disease, relapsing polychondritis and related disorders and some cutaneous adverse effects of rheumatological treatments.

History and examination

Apart from a dermatological and occupational history, questioning about the musculoskeletal system can help indicate a rheumatological diagnosis. Is there pain or stiffness? Where is it localized (e.g. specific muscles or large or small joints)? What exacerbates or relieves it? What words best describe the pain (e.g. the burning pain of neuropathy or the steady ache of an inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid)? Emotive terms such as ‘excruciating’ or ‘terrible’ may indicate a chronic pain syndrome or fibromyalgia, although ethnic and cultural factors may colour the description [1]. Joint stiffness in the morning or after a period of immobility is a feature of inflammatory joint disease. An accurate history of joint swelling can be difficult to elicit. Other questions include a history suggesting serositis, e.g. pleuritic chest pain, fever and its pattern, circulatory problems such as Raynaud phenomenon, soreness and redness of the eyes and fatigue.

Examination of the musculoskeletal system begins when the patient enters the consulting room. Are posture or gait affected? Localize points of pain, e.g. to specific joints, muscles or tendon sheaths; ‘trigger points’ of tenderness are seen in fibromyalgia. Look for joint swelling, synovial thickening or effusion, and determine which joints are affected. Monoarthritis can be a typical presentation of gout. Psoriatic arthritis often affects the distal interphalangeal joints, with associated nail dystrophy, but it can also affect large joints such as the shoulder or the axial skeleton. Look for erythema or temperature change near the affected joints (often normal skin temperature over osteoarthritic joints). Vasomotor alteration and trophic skin changes over a hand or foot occur in algodystrophy (Sudek atrophy), perhaps associated with neurological damage. Is there joint deformity, crepitus or restricted range of movement? Is there muscle wasting or weakness? Assess how the patient gets out of the chair at the end of the consultation. Laboratory and radiological tests can support the clinical diagnosis but should not be interpreted in isolation.

INFECTIVE ARTHROPATHIES

Several infective agents are associated with specific patterns of skin and joint involvement [1] (‘infection-related arthritis’); the major ones are discussed here.

Reactive arthritis

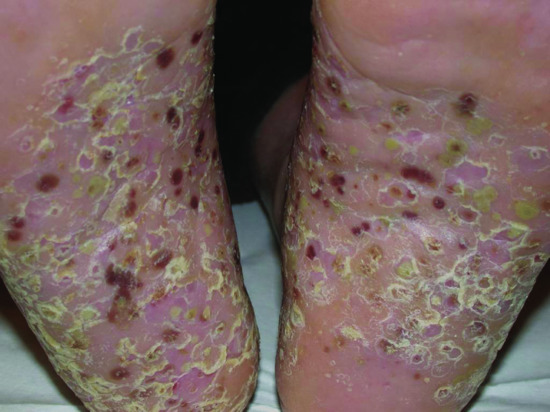

The term reactive arthritis refers to the development of spondyloarthritis following a genitourinary or gastrointestinal infection: it is strongly linked with the HLA-B27 haplotype [1, 2]. A range of infective organisms has been associated with the syndrome (Table 154.1). The classical clinical presentation comprises the triad of an asymmetrical large joint oligoarthritis with or without dactylitis, urethritis and ocular inflammation (conjunctivitis and anterior uveitis) manifesting 1–6 weeks after an acute sexually transmitted chlamydial infection. These may be accompanied by constitutional symptoms including fever and malaise. Skin lesions, most characteristically palmoplantar pustulosis and psoriasiform hyperkeratosis (keratoderma blennorhagicum: blennorhagia = excessive discharge of mucus), develop in around 15% of men with the syndrome. Mouth erosions, geographic tongue and circinate balanitis are common features (Figures 154.1 and 154.2a,b). Although the condition is usually self-limiting, it can progress to a chronic arthritis in around 15–20% of patients [3]. Co-infection with HIV is common in sexually acquired cases [4] and HIV may be arthritogenic [5]. There appears to be molecular mimicry between the infective organisms and a region of the HLA-B27α-I helix [6].

Table 154.1 Infectious agents commonly and less frequently associated with reactive arthritis.

| Gastrointestinal tract | Yersinia Salmonella Shigella Campylobacter jejuni |

| Uro-genital tract | Chlamydia trachomatis

Neisseria gonorrhoea Mycoplasma genitalium Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| Less frequent agents | Clostridium difficile Campylobacter lari Chlamydia psittaci Chlamydia pneumoniae |

From Selmi and Gershwin 2014 [2].

Figure 154.1 Keratoderma blennorhagicum in a patient with reactive arthritis.

Figure 154.2 (a) Geographic tongue and (b) circinate balanitis in HLA-B27 positive adolescent.

Viral arthropathies (see also Chapters 25 and 31)

Rubella and parvovirus B19 are the most commonly implicated viruses in self-limiting arthritis in the developed world. In rubella, a maculopapular rash spreads cephalocaudally, followed or preceded by occipital lymphadenopathy and arthralgia in up to 50%. A few develop a symmetrical polyarthritis affecting the metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joints, later involving the larger joints [1].

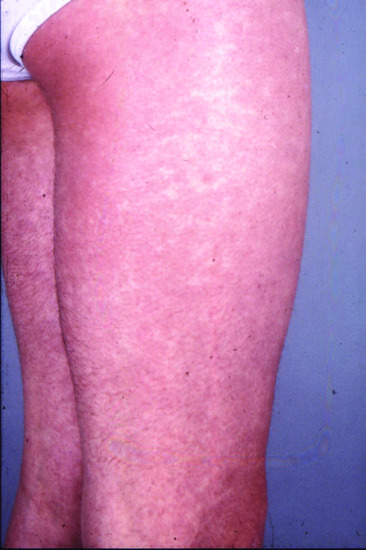

Parvovirus B19 is associated with erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), characterized by ‘slapped cheek’ erythema on the face (and sometimes also on the cheeks of the buttocks) and a reticulate erythema of the trunk and limbs (Figure 154.3); this erythema may recur over several weeks when the child is warm. Posterior cervical lymph nodes are enlarged. Systemic symptoms, such as myalgia and a symmetrical arthritis, are much commoner in adults than in children, occurring around a fortnight after infection [2]. Although parvovirus B19 infection may be associated with a chronic polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid disease [3], there appears to be little value in screening for viral infection in patients with polyarthritis persisting for more than 6 weeks [4].

Figure 154.3 Reticulate erythema of erythema infectiosum.

Arthralgia is common in the acute phase of many viral infections. Polyarthritis, which can be migratory, can be a feature of acute hepatitis B or C infection, usually before the icteric phase. Several rheumatological manifestations are associated with HIV infection. Around 10% of patients develop severe migratory joint pain at the acute seroconversion stage, chiefly affecting shoulders, elbows and knees, often persisting less than 24 h in each joint [5]. A reactive arthritis occurs in 2–3% and septic arthritis in 1% [6]. Diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome (DILS), which mimics SjÖgren syndrome, may be a presenting feature of HIV infection [6]. Unlike SjÖgren syndrome, males are predominantly affected and anti-ENA antibodies (Ro/SSA and La/SSB) are rarely found [7]. Since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), DILS is now rare. Immune reconstitution syndrome describes a systemic inflammatory process which develops from 3–24 months after initiating HAART. CD4 cells are elevated, with increased circulating cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and interferon γ. It is associated with a higher prevalence of autoimmune connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis [8–10].

Alphaviruses are transmitted by mosquitoes, chiefly Aedes species. Specific syndromes include chikungunya (literally ‘twisting up’) and O'nyong-nyong virus (literally ‘joint-breaker’), which are chiefly found in tropical Africa, Sindbis (chiefly in Sweden, Finland and the Baltic states), Mayaro virus (tropical South America) and Ross River virus (epidemic polyarthritis), which occurs in Australia, chiefly Queensland [11]. They are all associated with a maculopapular eruption, severe arthralgia and typically mild synovitis which resolves after weeks or months, although a rheumatoid arthritis-like syndrome may develop [12]. Chikungunya fever presents as facial or neck flushing within 1–5 days, followed by a widespread maculopapular eruption.

Bacterial arthropathies (see also Chapters 26 and 30)

Septic arthritis, usually due to Staphylococcus aureus, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of synovitis, particularly if there is a recent history of trauma or joint aspiration or if the patient is immunosuppressed, e.g. HIV infection or high-dose systemic corticosteroids. In patients on immunosuppressive drugs, joint infection may be caused by opportunistic organisms. Arthralgia can be a feature of acute bacterial infection, and may predominate in brucellosis. An intermittent migratory arthritis may follow the characteristic erythema migrans of Lyme disease or a relatively painless monoarthritis may develop, particularly targeting the knee joint [1]. Although arthralgia is common in syphilis, frank synovitis is rare.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and N. meninigitidis are both associated with inflammatory arthritis. Acute infections with either organism can be followed by an acute polyarthritis within 2–3 weeks [2]. Chronic meningocococcal arthritis is now rare in the developed world. It can be associated with a widespread macular erythema and tender papular, nodular or pustular lesions (Figure 154.4), which may become purpuric; histological changes range from perivascular inflammation to leucocytoclastic vasculitis [3]. Similarly, papular and vesicular lesions, often periarticular, occur in chronic gonococcaemia, and may be misdiagnosed as papular lupus erythematosus [4]. Gonococcal arthritis can be destructive, with or without associated tenosynovitis [5]. Men are at higher risk of gonococcal arthritis, and there may be co-infection with HIV. Usually, the organism can be isolated from blood culture or synovial fluid; if not, it can be identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [6] (see also Chapter 30).

Figure 154.4 A 19-year-old man with short history of headache, nausea, vomiting and weakness: the subsequently confirmed clinical suspicion of early meningococcal septicaemia was raised by the presence of a pustular vasculitic rash over the ankles.

Mycobacterial infections (see also Chapters 27 and 28) may be overlooked as causes of joint disease. In borderline leprosy a symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, often of insidious onset and of waxing and waning severity [7], can mimic a connective tissue disease and, confusingly, serological tests such as rheumatoid factor and antinuclear factor may be positive [8]. Extension of skin lesions on the fingers and toes can give rise to a dactylitis with leprous periostitis and eventually osteomyelitis [9]. Synovitis and dactylitis coincide with the appearance of skin lesions in the reactional state of erythema nodosum leprosum. Chronic nerve damage leads to muscle deformity and joint contracture with eventual joint destruction. Tuberculosis characteristically involves the spine, and may present to the dermatologist as a paravertebral abscess (Pott disease). Peripheral arthritis is usually monoarticular, and may result in bony ankylosis of the joint [10]. Septic arthritis, bursitis, tenosynovitis and even osteomyelitis can result from subcutaneous inoculation [11, 12] or as a contaminant during joint injection [13] of atypical mycobacteria such as M. marinum and M. avium-cellulare.

Rheumatic fever [14] follows infection with group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus, and comprises pyrexia, a migratory polyarthritis and carditis. It affects children, usually between 5 and 15 years, mostly in resource-poor countries. It may be preceded by scarlet fever. Impetigo due to group A streptococci predisposes to rheumatic carditis [15]. Scabies infestation, which is commonly impetiginized, is a major risk factor for rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis [16].

The characteristic urticated annular skin lesions of erythema marginatum, with a predilection for the trunk and proximal limbs, comprise one of the major criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever (see Figure 154.5) [17]. However, they are evanescent, and only seen in around 10% of children. Up to 20% develop subcutaneous nodules, which often occur in crops, typically on the extensor aspects of the limbs, but also over the scapula and forehead. Nodules may last only a few weeks; they are sometimes associated with the development of vegetations on the heart valves. In the Lewis rat model of rheumatic carditis, passive transfer of T-cell lines specific to peptides of streptococcal M protein induce valvulitis with expression of CD4+ T cells and up-regulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule type 1 (VCAM-1) on heart valves of naive rats; additionally, antistreptococcal antibodies attack the valve endothelium, leading to T-cell infiltration. These antibodies are also linked to the development of neuropsychiatric disease and Sydenham chorea [18].

In the developed world, Kawasaki disease has replaced rheumatic fever as a prime cause of cardiovascular disease in childhood [19]. Adult cases have been reported. A specific pathogen has not been identified. It is a systemic vasculitis. Clinical features include high swinging fever, conjunctival injection, erythema of the oral mucosa with a ‘strawberry tongue’ and fissured lips. Skin changes include a diffuse macular erythema and erythema of the palms and soles, which may result in desquamation of the limbs (see Figure 154.4). Up to 30% develop a self-limiting oligo- or polyarthritis of large joints [20].

Whipple disease typically affects middle-aged men who present with weight loss and diarrhoea, focal infections (e.g. endocarditis, encephalitis) and joint symptoms. The actinomycete Tropheryma whipplei has been identified as the causative organism, probably transmitted by the oro-oral or faeco-oral routes. It can be cultured from synovial fluid [21] or detected by PCR of skin lesions, lymph nodes or synovial fluid [22]. A chronic seronegative arthritis affects one or more large limb joints; the process is often intermittent. Spondyloarthropathy may develop [23]. Skin lesions, which are uncommon, include multiple generalized subcutaneous nodules and a septal panniculitis . A granulomatous dermal infiltrate is associated with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) positive macrophages [24]. Treatment has been associated with the development of lesions resembling erythema nodosum leprosum [25]. Untreated, the neurological changes can be fatal, and lifelong doxycycline is recommended because of the risk of relapse [22].

Other infective arthropathies

Disseminated fungal infection (e.g. coccidioidomycosis [1]) may lead to synovitis of one or more joints, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals.

Mycetoma is a progressive tumour-like mass, often affecting the foot. It may be caused by actinomycetes (actinomycetoma; see Chapter 26) or fungi, notably Madurella mycetomatis (eumycetoma; see Chapter 32). The diagnosis can be confirmed by histology and culture of the grains that extrude from the lesion. The mass can destructively invade underlying bone, and amputation is often required [2, 3].

Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (see Chapter 33) is an inflammatory process that may be associated with arthralgia and joint contracture (Figure 154.5). Leishmania synovitis has been described mostly in dogs, although polyarthritis has been reported in immunosuppressed humans [4].

Figure 154.5 Severe joint contractures in a child with post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis.

INFLAMMATORY ARTHROPATHIES

Seronegative arthritis and spondylitis

Seronegative arthritis and spondyloarthropathy are associated with inflammatory bowel disease (see Chapter 152) and psoriasis (see Chapter 35), notably in individuals possessing the HLA-B27 haplotype. There is an increased prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in these individuals [1]. Pyoderma gangrenosum is also characteristically associated with ulcerative colitis and spondyloarthritis; in one survey of 103 patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, 34% had inflammatory bowel disease and 19% pyoderma gangrenosum [2].

Rheumatoid arthritis

Reddening of the skin and a burning sensation may be the initial manifestation of rheumatoid disease, before joint changes develop [1]. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with several skin abnormalities, including non-segmental vitiligo [2] (Box 154.1).

Rheumatoid arthritis-associated skin atrophy

In rheumatoid patients over the age of 60 years, especially women, the skin on the dorsa of the hands may become thin, loose, smooth, inelastic and transparent, so that the details of veins and tendons are clearly seen. The change is generalized but is seldom conspicuous except on the hands and forearms. Histologically, the dermis is thinned but shows no distinctive changes.

There is a significant association between transparent skin, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis, and it is assumed to form part of a general connective tissue defect [1]. Steroid therapy is not a factor but it will potentiate the problem [2, 3]. Skin collagen is structurally abnormal [4]. A reported association with pseudoxanthoma elasticum may be coincidental [5].

Rheumatoid nodules

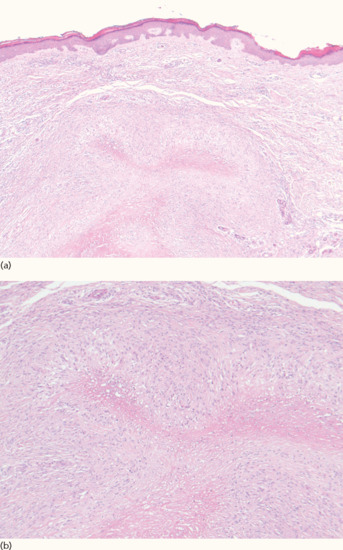

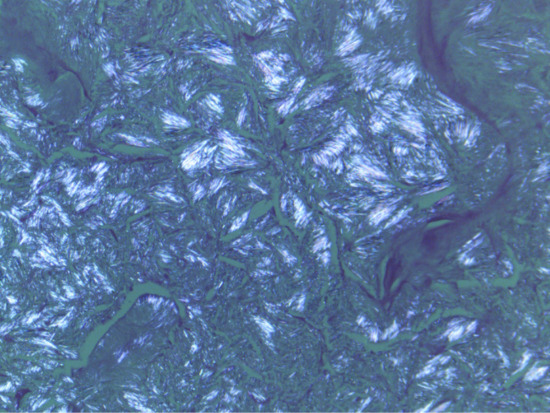

Skin-coloured subcutaneous nodules, often multiple, occur in over 20% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, especially in men and in seropositive disease [1]. They are usually asymptomatic, and found over extensor surfaces, such as the elbows and knees (Figure 154.6), and sites of repetitive trauma. Histology is characteristic, with palisading granulomata around a central area of fibrinoid necrobiosis (Figure 154.7). Necrobiosis is closely associated with the pathogenesis of rheumatoid disease, including collagen degeneration, recruitment of activated neutrophils, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and vascular injury [2].

Figure 154.6 (a,b) Multiple rheumatoid nodules on the lower leg and knees.

Figure 154.7 Histology of rheumatoid nodule at low power (a) and at higher power showing palisading granulomata (b).

The differential diagnosis includes knuckle pads, subcutaneous sarcoid and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Indeed the latter (especially in children) can be associated with a positive rheumatoid factor, leading to a false diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (see Chapter 99). Measurement of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies is current rheumatological practice in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. These antibodies are more specific than rheumatoid factor and appear to be more predictive of progressive disease [3]. Nodules may occur also in the lung parenchyma (Kaplan syndrome). Cutaneous nodules wax and wane with treatment of the disease; rituximab has proved a beneficial treatment [4]. However, some drugs, including methotrexate, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents and leflunomide may exacerbate nodulosis [1]. The term ‘accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis’ describes painful rheumatoid-like nodules which develop rapidly, chiefly on the ears, hands and feet [5], and often on previously unaffected sites. They are typically associated with methotrexate therapy, and often regress when the drug is discontinued [6]. The aetiopathogenesis is uncertain; genetic factors include an increased prevalence of HLA-DR4 [7] and the 2756GG genotype of methionine synthase reductase in affected patients [8] (see Chapter 99).

Rheumatoid vasculitis and cutaneous ulceration

Digital vasculitis (Figure 154.8) presents as splinter haemorrhages and periungual infarcts, palpable purpura, livedo reticularis and atrophie blanche, especially in patients with high titres of rheumatoid factor or citrullinated peptides (CCP). Vasculitis may be associated with cutaneous and pulmonary nodulosis, episcleritis and pleural or pericardial effusions. Pyoderma gangrenosum, which may be atypical [1], can be associated with rheumatoid arthritis. It may respond to colchicine, ciclosporin or dapsone, but some patients require high dose corticosteroids or even anti-TNF-α drugs such as infliximab or certolizumab pegol [2–4]. Rheumatoid patients on immunosuppressive therapy are at risk of infections that may simulate vasculitis [5, 6].

Figure 154.8 Digital vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis.

Chronic leg ulcers in rheumatoid patients are often difficult to manage, and often have mixed aetiology. Causes include arterial occlusion due to vasculitis, venous insufficiency, lympho-oedema, ‘inactivity ulcers’ linked with immobility, poor wound healing and thin skin [7, 8, 9]. Methotrexate and TNF inhibitor therapy appear to potentiate vasculitic ulcers in some cases [10, 11], but can be beneficial in others. Loss of sensation and forefoot deformity contribute to foot ulceration in rheumatoid patients [12].

Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis

Neutrophilic disorders occupy a spectrum including pyoderma gangrenosum (see earlier) and Sweet disease; indeed these different conditions may coexist in one patient. They are typically associated with systemic diseases such as blood cell dyscrasias, inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis [1] and have also been associated with systemic lupus erythematosus [2].

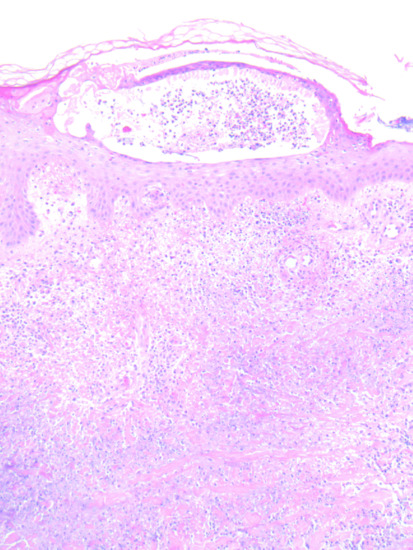

Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis presents as urticaria-like papules and plaques, often symmetrically on the trunk and limbs. There is probably an overlap with Sweet syndrome, although the typical plum-coloured lesions of the latter are not generally seen. Histologically, there is a heavy dermal infiltrate of neutrophils but no frank vasculitis (Figure 154.9) [3].Tense bullae may occur on the lower legs; this variant responds to dapsone, but not to corticosteroids [4, 5]. Neutrophilic dermatosis can present in patients with seropositive or seronegative rheumatoid disease. Some patients develop nodular lesions which can progress to rheumatoid nodules [6].

Figure 154.9 Histology of neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Other

Other conditions which may occur in association with rheumatoid arthritis include interstitial granulomatous dermatosis and intralymphatic histiocytosis (see later).

Fibroblastic rheumatism

This rare condition occurs worldwide, primarily affecting white people of any age; the sex incidence is equal. Acute onset symmetrical polyarthritis is associated with multiple skin-coloured papules and nodules measuring 5–20 mm diameter on the limbs. Some patients give a history of Raynaud phenomenon; there may be sclerodactyly and palmar thickening [1–3], suggesting a forme fruste of a connective tissue disease such as systemic sclerosis. Histology of the skin lesions reveals increased numbers of fibroblasts with myofibroblast differentiation, diffuse dermal fibrosis and absence of elastin on orcein staining [4, 5]. Myofibroblast-like cells are also seen within a collagenous stroma in the synovium [1]. Periarticular erosions may be detected on bone X-ray [1, 6]. Clinically, the condition may mimic multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, and it has been suggested that, like the latter condition, fibroblastic rheumatism is a form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis [7]. However, it fits better into the category of an inflammatory fibromatosis [1, 4, 6, 8]. Unlike multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, fibroblastic rheumatism is not associated with systemic disease or malignant neoplasia [9]. The condition is often self-limiting [10], although immunosuppressive therapy has been used to good effect, including methotrexate [2, 5], interferon-α [6] and infliximab [11]. Bony erosions may persist despite methotrexate therapy [6].

Sarcoidosis (see also Chapter 98)

Acute synovitis is common in patients with Löfgren syndrome (an acute variant of sarcoidosis with erythema nodosum and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest X-ray). The arthritis affects ankles and knees in particular, and tends to resolve in 3–6 months. Chronic sarcoid dactylitis typically affects young adults; the fingers and toes become sausage shaped with spindling (Figure 154.10; see also Figure 154.15). X-rays show a lace-like trabecular pattern with cystic changes in the phalanges [1]. There may be additional flexion deformity due to involvement of finger muscles [2]. Chronic sarcoid oligo- or polyarthritis is rare, affecting around 0.2% patients, favouring those of African descent [1, 3]. Sacroiliitis and spondyloarthritis are commoner than in the general population [4]. Methotrexate is beneficial for both cutaneous lesions and inflammatory joint disease [5]. Although anti-TNF drugs are associated with radiological improvement [6] there is little evidence that they are beneficial clinically for joint disease [7].

Figure 154.10 Sarcoid dactylitis.

So-called early-onset sarcoidosis, which is associated with a chronic granulomatous polyarthritis, has been shown to be the sporadic variant of autoinflammatory granulomatosis of childhood (Blau syndrome) [8]. It is discussed in further detail in Chapter 45.

OSTEOARTHRITIS

A patient with osteoarthritis may present to the dermatologist with concerns about Heberden nodes. Additionally, two metabolic syndromes, haemochromatosis and alkaptonuria, are associated with osteoarthritis (see later).

Heberden and Bouchard nodes

Heberden nodes [1] are posterolateral bony outgrowths affecting one or more distal interphalangeal joints. Similar changes, affecting the proximal interphalangeal joints, are termed Bouchard nodes. Both Heberden and Bouchard nodes are strongly associated with osteoarthritis, although they may be inherited independently as an autosomal dominant trait [2, 3]. Characteristically, they are asymptomatic and of insidious onset, although tender nodes may develop acutely with a red swollen joint. They are commoner on the dominant hand and are associated with radiological features of osteoarthritis such as joint space narrowing [4]. The association of multiple symmetrical nodes with distal interphalangeal joint arthritis has been termed ‘primary generalized osteoarthritis’. Because this is associated with the tissue types HLA-A1 and B8 and shows a marked female preponderance, it has been postulated to be an autoimmune disorder: increased amounts of immune complexes can be detected in cartilage and synovium [5].

METABOLIC DISORDERS WITH MUSCULOSKELETAL AND CUTANEOUS INVOLVEMENT

Haemochromatosis (see Chapter 88)

The classic triad of diabetes, skin hyperpigmentation (bronze diabetes) and cirrhosis is now rare, but musculoskeletal symptoms are common and unresponsive to phlebotomy. The second and third metacarpophalangeal joints are typically affected with pseudogout-like attacks followed by degenerative joint changes with osteophytes. X-ray studies reveal chondrocalcinosis in 50% of cases. Most patients with the condition exhibit a C282Y homozygous mutation in the HFE gene [1].

Alkaptonuria (see Chapter 81)

In this autosomal recessive metabolic disorder, deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase results in deposition of homogentisic acid in connective tissue (ochronosis), causing a grey-black pigmentation most noticeable in ear and nose cartilage. Homopolymeric oxidation products of homogentisic acid bind to collagen, leading to inflammation and degenerative change. Eventually this results in calcification of intervertebral discs and osteoarthritis, chiefly affecting the knees [1, 2].

Gout

Gout may present at any age in adults, especially in the elderly when it may be triggered by diuretic therapy. Acute gout is commoner in men. Although the clinical features are caused by deposition of monosodium urate in tissues, less than 5% of subjects with hyperuricaemia in the UK develop clinical gout. Deposition of the needle-like crystals of monosodium urate is often linked to a sudden recent rise of serum uric acid. Acute gout presents as a monoarthritis, classically affecting the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. Untreated hyperuricaemia may lead to recurrent more severe attacks affecting several joints.

Tophaceous gout (ICD-11: 847186333) used to be a common presenting feature of acute symptomatic gout [1, 2]. A creatinine clearance of less than 30 mL/min is strongly associated with the development of tophi [3]. Since the introduction of allopurinol therapy for hyperuricaemia and gout, tophi occur much less frequently. A tophus is a dense aggregate of monosodium urate crystals presenting as a papule or nodule in the skin [1] (Figures 154.11 and 154.12). Tophi have a predilection for the pinnae, elbows and Achilles tendons (where they may be confused with tendon xanthomata). Tophi may occur without arthritis [4]. They may ulcerate and become secondarily infected. Release of crystals in the conjunctivae cause an acute red eye. Tophi can also occur in the viscera, e.g. the heart. The differential diagnosis includes rheumatoid nodules, neurofibromata and xanthomata. Diagnosis can be made by polarizing microscopy of an aspirate; the stacks of crystals are strongly birefringent [2] (Figure 154.13). The histopathology of gout is discussed in Chapter 99.

Figure 154.11 Tophaceous gout showing multiple cream-coloured papules on the palmar surfaces of the digits (inset: close-up view of thumb).

Figure 154.12 Severe tophaceous gout and acute gouty inflammation affecting the index finger and thumb.

Figure 154.13 Birefringent crystals of uric acid in a gouty tophus (examined under polarizing microscope).

Monosodium urate crystals stimulate IL-β secretion via cryopyrin, giving rise to the acute inflammatory response [5]. Allopurinol is the drug of choice in reducing hyperuricaemia. Unfortunately the drug can be associated with cutaneous adverse effects, including DRESS (drug reaction or rash, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms), Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (see Chapter 119). Recent pharmacogenetic studies have shown that severe reactions are associated with the (HLA)B* allele, offering the possibility of genetic testing in the future [6].

AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISORDERS

Hereditary autoinflflammatory disorders

Several monogenic ‘inflammasome’ disorders have been described which result in autoactivation of the IL-β pathway. Most of them can cause arthralgia or arthritis. Most are rare and present in early childhood. They can be classified into a number of broad groups (Box 154.2)

They are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 45.

Acquired autoinflammatory disorders

Schnitzler syndrome, adult-onset Still disease, systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis) all affect the musculoskeletal system and are discussed in Chapter 45.

Acne (see Chapter 90)

Severe acne is associated with joint symptoms and arthritis.

Acne conglobata has been linked to sacroiliitis, especially in young black men [1]. Associated features may include dissecting cellulitis of the scalp and hidradenitis suppurativa. In addition to sacroiliitis and axial spondylosis there may be an asymmetrical peripheral arthritis, which develops later than the skin disease. Unlike other spondyloarthropathies, the condition is not associated with HLA-B27 [2].

Acne fulminans is a systemic disease typically affecting adolescent white males. In addition to severe acne with abscesses and areas of ulceration, the syndrome includes fever, weight loss and arthralgia. X-rays may reveal osteolytic lesions in the clavicle, sternum, long bones or ilium [1]. Isotretinoin therapy is commonly associated with arthralgia and myalgia in both sexes; this is often trivial and therapy can be continued. Prolonged isotretinoin therapy is associated with spinal hyperostosis, which may be asymptomatic [1]. In a patient with severe acne, isotretinoin therapy may precipitate acute sacroiliitis, which can be disabling [3, 4]. Concomitant prednisolone therapy, and initiating isotretinoin at a low dose, may help prevent this.

Significant acne is a feature of several syndromes, several of which have musculoskeletal features. These include monogenic inherited syndromes such as PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne), DIRA (deficiency of IL-1 receptor antagonist) and SAPHO syndromes, all of which are described in Chapter 45.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (see Chapter 92)

This is associated with several syndromes described earlier, as well as with inflammatory bowel disease [1]. A recent survey of hidradenitis suppurativa patients identified an association with arthralgia, back pain and enthesitis, as well as SAPHO syndrome (see Chapter 45) [2].

INFLAMMATORY CHONDROPATHIES

Relapsing polychondritis

Definition and nomenclature In this non-infective condition, focal inflammatory destruction of cartilage is accompanied by fibroblastic regeneration. It is characterized by the following:

- Recurrent bilateral chondritis of the pinnae.

- Chondritis of the nasal cartilage.

- Chondritis of the respiratory tract.

- Ocular inflammation, including conjunctivitis, scleritis, episcleritis or uveitis.

- Cochlear or vestibular lesions.

- Seronegative non-erosive inflammatory arthritis.

Three or more of these features are required for the diagnosis [1].

Aetiology

Relapsing polychondritis has been recorded as rare, but recent reports suggest that it is not so uncommon but is easily overlooked. The cause is unknown, but it is probably a Th1-mediated disease. Serum levels of cytokines such as interferon-γ, IL-12 and IL-2 parallel changes in disease activity, whereas Th2 cytokines do not [2].

Antibodies to type II collagen have been detected in the serum in acute polychondritis, and granular deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, IgM and C3 at fibrochondrial junctions have indicated a possible role of immune-complex deposits [3–7]. Antibody production is T-cell dependent and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restricted; the arthritis in experimental animal models can be suppressed by synthetic type II collagen peptides [8]. The intravenous injection of papain into rabbits produces loss of cartilage rigidity, manifested by floppy ears [9], and it has been suggested that local protease activity may play some part in causing relapsing polychondritis [10]. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) is decreased and cartilage matrix protein (matrillin-1) increased. Both revert to normal levels during successful therapy [11]; however, in practice they are unreliable markers of disease activity [12]. A recent study suggests that the serum level of soluble triggering receptor, expressed on myeloid cells and typically associated with bacterial infections such as meningitis, more closely reflects disease activity and may be a useful biomarker [13].

Associated conditions suggest that autoimmune mechanisms may be concerned (see also MAGIC syndrome, see later). They include rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, Behçet disease, Hashimoto disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, psoriasis, glomerulonephritis, Sjögren syndrome, thymoma, ankylosing spondylitis, myeloproliferative disorders and following intravenous injections [14–19]. Cutaneous manifestations have been reported in a patient treated for prostatic adenocarcinoma with goserelin, a luteinizing hormone releasing analogue [20].

Relapsing polychondritis probably overlaps with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Auricular chondritis has been described in some patients with the latter [21], and cANCA, an antibody once regarded as specific for GPA, has been reported in patients with relapsing polychondritis [22].

Pathology [23]

Areas of damaged cartilage, which have lost the normal basophilic staining, are separated by areas of predominantly lymphocytic infiltration. Later, the fragments of cartilage are surrounded and replaced by abundant granulation tissue and even nascent cartilage. Occasionally, there is evidence of vasculitis [24].

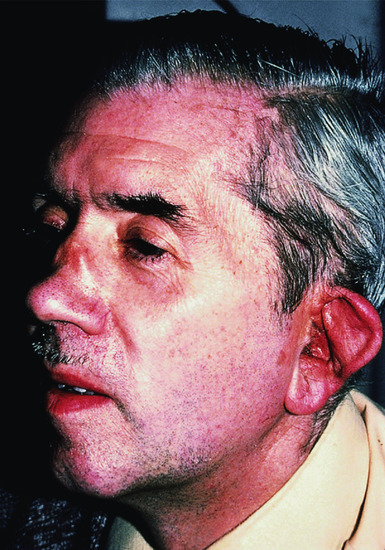

Clinical features [1, 25–28] (Box 154.3)

The condition affects both sexes equally and usually begins between the ages of 30 and 50 years. Chondritis ultimately involves three or more sites in most patients but may be limited to one or two for long periods. The following tissues may be involved in decreasing order of frequency: auricular, joint, nasal, ocular, respiratory tract, heart valves and skin [29, 30]. During the acute stage, the affected area is swollen, red and tender, and may be mistaken for cellulitis (Figure 154.14). Sparing of the ear lobule is a useful differentiating sign. The ear becomes floppy (the ‘forward listening’ ear).Thinning of the cartilage allows the underlying vasculature of the ear to be more visible (the ‘blue ear’ sign) [31]. Serous otitis media can occur, and there may be loss of hearing even in the absence of chondritis [32]. Involvement of the nasal cartilage leads to obstruction and later to a saddle-nose deformity, which may lead to collapse of the nasal bridge [33] (Figure 154.15). Cutaneous and systemic vasculitis, cerebral aneurysms, superficial thrombophlebitis and toxic erythema have been described [1, 24, 27, 34]. A few patients have been described in whom an annular eruption comprising tense urticated papules precedes chondritis; histology reveals a lymphocytic vasculitis. All these patients have haematological abnormalities such as myelodysplasia. Although initially responsive to corticosteroids, this variant carries a poor prognosis [35].

Figure 154.14 Relapsing polychondritis, showing inflammation of the pinna.

Figure 154.15 Relapsing polychondritis: late stage, showing damage to the cartilage of the ear and nose.

The joint changes, usually affecting the smaller peripheral joints, may simulate rheumatoid arthritis [36]. Involvement of the larynx, trachea or bronchi produces respiratory embarrassment and recurrent infection. Permanent tracheostomy may be required [23, 32]. An association with granulomatous lung disease has also been described. Ocular abnormalities are found in some cases – episcleritis, conjunctivitis and iritis (Figure 154.16), scleromalacia, and more rarely keratoconjunctivitis sicca or chorioretinitis. Proptosis occurs in 3% of cases [37, 38]. Giant cell myocarditis is reported, and involvement of the heart valves may cause serious complications, including sudden valve rupture, even in a patient otherwise in remission [1, 39, 40].

Figure 154.16 Relapsing polychondritis, showing ocular involvement.

The course of the disease is extremely variable [19, 28]. Attempts have been made to devise a ‘disease activity’ score [41]. Relapses are the rule, but they vary in frequency and severity. Some cases continue to relapse for over 20 years, but others become inactive within a short period. Pregnancy does not appear to affect the course of the disease, although complications are more frequent [42]. Deformity of the ears and nose is common, but in general the disease is a source of discomfort and disfigurement rather than a threat to life. Plasma viscosity or erythrocyte sedimentation rate is usually raised and anaemia is frequent. The rheumatoid factor and antinuclear factor are often positive. Leukocytosis is inconstant, but eosinophilia is found in 40% of cases. A characteristic biochemical finding is the increased urinary excretion of acid mucopolysaccharides during each relapse.

Radiological abnormalities are not pathognomonic, but evidence of extensive destruction of joint cartilage without changes in adjacent bone is suggestive on plain X-ray. In some cases, the changes are indistinguishable from rheumatoid arthritis. Fluorine-18 deoxyglucose uptake is increased in affected cartilage on PET/CT; this is a useful investigation to determine the extent of cartilage involvement [43]. Doppler echocardiography, MRI and dynamic expiratory computed tomography are of value in investigating cardiopulmonary involvement [12]. Bronchoscopy runs the risk of worsening respiratory dysfunction [12].

Diagnosis

Polychondritis may present to the dermatologist as ‘chronic otitis externa with cellulitis of the pinna’. The diagnosis is established by biopsy, or by other associated changes, and appropriate radiology. GPA and lethal midline granuloma (also causes of a saddle-nose deformity [33]) can produce a similar histology, but in these two conditions the involvement is more purely destructive.

Treatment

The progression of the acute relapse can be controlled with corticosteroids. An initial daily dose of 30 mg prednisolone can be gradually reduced and finally discontinued as remission develops. Indometacin and dapsone have been used [5]. Colchicine is also helpful in some patients [44]. Immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate and ciclosporin [7, 12] may have a role. Pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide has been used for renal disease [12, 45]. Intravenous immunoglobulin [46] and anti-TNF antagonists such as adalimumab have proved to give sustained remission in several [47, 48]. Other cytokine modulators used with success include rituximab and tocilizumab [2]. Remission has followed autologous stem cell transplantation [49]. Surgical reconstruction of the nose or larynx is sometimes required.

MAGIC syndrome

Several patients have been described with features of both relapsing polychondritis and Behçet disease [1]. The term MAGIC syndrome (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage) has been used for this overlap syndrome. The underlying immunological defects are still unclear, but circulating immune complexes and autoantibodies to elastic tissue have been suggested as possible factors [1, 2]. The nodules on the auricle affect the antihelix but, as in polychondritis, spare the lobule [3].

Aortic valve disease and aneurysmal aortitis have been associated with the syndrome [4, 5], and features of the MAGIC syndrome have been described in an HIV-positive individual [6].

Several therapies have been tried, including dapsone, corticosteroids and pentoxifylline. Infliximab has been successful in a severe case [7].

MISCELLANEOUS DISORDERS INVOLVING THE SKIN AND MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Mastocytosis (see Chapter 46)

Some patients with cutaneous mastocytosis (e.g. telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans) experience bone pain due to osteoporosis, related to release of mast cell mediators such as heparin, tryptase and IL-6. Radiological bone changes include localized osteolysis or osteosclerosis and generalized osteopenia or osteosclerosis [1]. The spine is particularly affected and pathological fractures are commoner in men; the severity of osteoporosis relates to raised levels of mast cell tryptase [1] and IL-6 [2]. Spondyloarthritis is commoner in patients with mastocytosis than in the general population [3].

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis

This condition is characterized by destructive polyarthritis, chiefly affecting the distal interphalangeal joints. It may be misdiagnosed as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis. It is one of the most destructive forms of arthritis and severe changes (arthritis mutilans) occur in nearly 50% of patients, with ‘pencil in cup’ changes on X-ray. It is described in detail in Chapter 136.

Pachydermoperiostosis

Introduction and general description

In this rare condition [1–3], inheritance is autosomal dominant, but autosomal recessive families probably also occur [4]. At least two gene mutations are implicated, HPGD and SLCO2A1 [5]. Digital clubbing is associated with cylindrical thickening of legs and forearms (which may suggest acromegaly [6]) (Figure 154.17), hypohidrosis, seborrhoea, sebaceous gland hyperplasia and folliculitis. Arthritis may be severe, with florid knee effusions. Additional clinical features include thickened skin on the forehead, carpal and tarsal tunnel syndrome, chronic leg ulceration and calcification of the Achilles tendon [7]. Cultured dermal fibroblasts synthesize increased amounts of collagen and α1 [8] procollagen mRNA, and exhibit up-regulation of transcriptional activity of the α1(I) procollagen gene promoter [9]. Proteoglycan synthesis is also affected [10].

Figure 154.17 (a,b) Views of the hand (a) and the lower legs and ankles (b) in pachydermoperiostosis.

X-rays reveal symmetrical, irregular periosteal ossification, predominantly affecting the distal ends of long bones [1]. Histology shows cutaneous sclerosis and hyalinosis, with perivascular infiltration by lymphoid cells in the dermis [2].

When conventional treatments (including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids) fail, bisphosphonates such as intravenous pamidronate may help rheumatological manifestations [11]. Cosmetic procedures such as facelift and botulinum toxin improve facial appearance [12].

Interstitial granulomatous dermatosis (see Chapter 102)

This condition is associated with several autoimmune disorders such as Hashimoto thyroiditis and diabetes, as well as autoimmune connective tissue diseases. An association with rheumatoid arthritis is reported in several cases, although the arthritis is often seronegative and non-erosive; in over 50% of patients it is progressive and destructive, resembling psoriatic arthritis [1, 2]. The condition affects adults.

Skin-coloured, erythematous or violaceous papules, linear bands or plaques develop symmetrically on the lateral aspects of the trunk, proximal thighs or axillae. Lesions can be painful or pruritic [1, 2]. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis [3] is probably a variant, with papules and nodules on the extremities.

Skin histology is distinctive: there is a granulomatous interstitial and palisading infiltrate with CD68+ histiocytes showing a variable degree of phagocytosis in the mid to deep reticular dermis. The collagen bundles are thickened but there is also piecemeal fragmentation of collagen and elastic fibres [2, 4, 5].

It is probable that the condition is related to deposition of immune complexes in the skin. Skin and joint lesions may resolve spontaneously in a few weeks, may be recurrent or progress over many months or years [1, 2]. Several drugs have been tried, including NSAIDs, corticosteroids, dapsone, colchicine and tacrolimus [6]. Anti-TNF therapies such as etanercept [5] are beneficial, although these agents may trigger the condition [6]. Ustekinumab has also been used successfully [7].

Intralymphatic histiocytosis [1–4]

Swelling and erythema resembling cellulitis occurs around the elbow or knee in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory disorders such as Crohn disease; it may occur in the absence of systemic disease [4]. Several cases are reported affecting the tissues adjacent to an orthopaedic metal implant [5, 6, 7]; this may raise concern about infection or rejection. Typically asymptomatic poorly demarcated erythematous plaques or livedo reticularis-like lesions develop near an elbow or knee. There may be overlying verrucous change. Histology shows dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, with an endothelial marker profile suggesting lymphatic origin. Some vessels contain CD68+ mononuclear histiocytes [1, 4, 7]. It has been suggested that the condition is related to reactive intravascular angioendotheliomatosis, forming part of the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis [4, 7, 8]. It is a benign process, and although there are reports of the use of drugs such as infliximab [9], it can respond to simple pressure bandaging, suggesting that it may be related to local lymphostasis [10].

CUTANEOUS ADVERSE REACTIONS TO ANTIRHEUMATIC THERAPIES (see also Chapters 120 and 121)

Skin lesions are commonly encountered in patients receiving antirheumatic therapy. Some are trivial, but others may require discontinuation of treatment.

NSAIDs and allopurinol are among the most frequently reported causes of severe adverse drug reactions including DRESS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [1]. Viraemia can be a compounding factor in an immunosuppressed patient [2]. A better understanding of pharmacogenomics may enable screening at-risk patients in the future [2, 3]. This is already potentially achievable with allopurinol [4]. NSAIDs are photosensitizing, and can induce photo-onycholysis. A pseudoporphyria, clinically resembling porphyria cutanea tarda, is seen in patients taking naproxen. Fixed drug eruptions are associated with some NSAIDs, including piroxicam, mefenamic acid and oxyphenbutazone. Urticarial lesions may be induced by immunological or pharmacological mechanisms [3]. Topical NSAIDs, notably ketoprofen, may photosensitize. Cross-reaction with octocrylene, a sunscreen ingredient, is often seen with ketoprofen photosensitivity [5].

Antimalarials e.g. hydroxychloroquine, should be avoided in patients with psoriasis as they may exacerbate the condition [6]. They are also implicated in lichenoid drug reactions, acute generalized exanthematic pustulosis [7] and DRESS syndrome [8]. Mepacrine causes yellow pigmentation of the skin (Figure 154.18) and sclerae and can also induce cutaneous ochronosis (Figure 154.19).

Figure 154.18 Yellow pigmentation of the skin due to mepacrine.

Figure 154.19 Ochronosis of the nail beds due to mepacrine.

Sulfasalazine is also implicated in DRESS [9]; it is a photosensitizer and can induce or exacerbate lupus erythematosus [10].

Corticosteroids. The atrophogenic effects of systemic corticosteroids are well recognized [11], but even intralesional steroids can induce cushingoid features and an acneform eruption [12], as well as the risk of local dermal atrophy.

D-penicillamine can induce lupus or a lichenoid reaction, and its use in Wilson disease is associated with a pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like syndrome.

TNF-α inhibitors may induce an eruption clinically and histologically resembling psoriasis, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: adalimumab may be a major culprit [13, 14]. Fortunately, the eruption often responds to topical therapy and, if not, generally resolves on changing to another biological agent. The risk of serious skin and soft-tissue infections does not appear to be increased in rheumatoid patients on anti-TNF-α drugs [15].

Skin cancer promotion. Non-melanoma skin cancer is commoner in rheumatoid patients than in the general population, attributable at least in part to drugs such as methotrexate and anti-TNF drugs [16]. Multiple eruptive squamous cell carcinomata occurred in a patient on abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis [17]. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomata have been associated with leflunomide, regressing when the drug was discontinued [18]. Lymphomatoid papulosis has been attributed to adalimumab in a patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [19]. Fortunately, the prevalence of melanoma is not increased in rheumatoid arthritis [20]. Historically, multiple basal cell carcinomas developed in the skin overlying sites of radiotherapy for ankylosing spondylitis, i.e. the spine and sacroiliac joints, usually many years after irradiation [21, 22].

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Dr Leigh Biddlestone for providing the histological images.

References

Introduction

- Zborowski M. Cultural components in response to pain. J Soc Iss 1952;8:17–30.

Infective arthropathies

- Espinoza LR, Garcia-Valladares I. Of bugs and joints: the relationship between infection and joints. Rheumatol Clin 2013;9:229–38.

Reactive arthritis

- Braun J, Kingsley G, Van der Heijde D, et al. On the difficulties of establishing a consensus on the definition of and diagnostic investigations for reactive arthritis. Results and discussion of a questionnaire prepared for the 4th international workshop on reactive arthritis, Berlin, Germany, July 3–6, 1999. J Rheum 2000;27:2185–92.

- Selmi C, Gershwin ME. Diagnosis and classification of reactive arthritis. Autoimmune Rev 2014;13:546–9.

- Wu iB, Schwartz PA. Reiter's syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:113–21.

- Winchester R, Bernstein DH, Fischer HD, et al. The co-occurrence of Reiter's syndrome and acquired immunodeficiency. Am J Intern Med 1987;106:19–26.

- Forster SM, Seifert MH, Keat AL, et al. Inflammatory joint disease and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1625–7.

- Lahesmaa R, Skwaik M, Vaara M, et al. Molecular mimickry between HLA-B27 and Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella and Klebsiella with the same region of HLA αI- helix. Clin Exp Immunol 1991;86:399–404.

Viral arthropathies

- Franssila R. Viral causes of arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;6:1138–57.

- Naides SJ, Scharosch LL, Foto F, et al. Rheumatologic manifestations of human parvovirus B19 infection in adults. Initial two-year clinical experience. Arth Rheum 1990;33:1297–309.

- Colmegna I, Alberts-Grill N. Parvovirus B19: its role in chronic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2009;35:95–110.

- Varache S, Narbonne V, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Is routine viral screening useful in patients with recent-onset polyarthritis of a duration of at least six weeks? Results of a nationwide longitudinal prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1565–70.

- Reveille JD. The changing spectrum of rheumatic disease in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Arth Rheum 2000;30:147–66.

- Kole AK, Roy R, Kole DC. Musculoskeletal and rheumatological disorders in HIV infection: experience in a tertiary referral center. Indian J Sex Transm Dis 2013;34:107–12.

- Kazi S, Cohen PR, Williams F, et al. The diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome; clinical and immunogenetic features in 35 patients. AIDS 1996;10:385–91.

- Malin JK, Patel NJ. Arthropathy and HIV infection: a muddle of mimicry. Postgrad Med 1995;93:143–6.

- Calabrese L, Kirchner E, Shrestha E. Rheumatic complications of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): emergence of a new syndrome of immune reconstitution and changing pattern of disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;35:166–74.

- Nguyen BY, Reveille JD. Rheumatic manifestations associated with HIV in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009;21:404–10.

- Fraser JRE. Epidemic polyarthritis and Ross River Disease. Clin Rheum Dis 1986;12:369–88.

- Das T, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Hoarau JJ, et al. Chikungunya fever: CNS infection and pathologies of a re-emerging arbovirus. Prog Neurobiol 2010;91:121–9.

Bacterial arthropathies

- Bhate C, Schwartz RA. Lyme disease. Part 1. Advances and perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:619–36.

- Bookstaver PB, Rudisill CN. Primary meningococcal arthritis as initial presentation in a previously undiagnosed HIV-infected patient. South Med J 2009;102:438–9.

- Pace D, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal disease; clinical presentation and sequelae. Vaccine 2012;30:B3–B9.

- Dutertre M, Tomasevic D, Guillermin Y, et al. Gonococcaemia mimicking a lupus flare in a young woman. Lupus 2014;23:81–3.

- Belkacem A, Caumes E, Ouanich J, et al. Changing patterns of disseminated gonococcal infection in France; cross-sectional data 2009-11. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:613–15.

- Kimmitt PT, Kirby A, Perera N, et al. Identification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae as the causative agent in a case of culture-negative dermatitis arthritis syndrome using real-time PCR. J Travel Med 2008;15:369–71.

- Pereira HL, Ribeiro SL, Pennini SN, et al. Leprosy-related joint involvement. Clin Rheumatol 2009;28:79–82.

- Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting; a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:1557–63.

- Atkin SL, el Ghobarey A, Kamel M, et al. Clinical and laboratory studies of arthritis in leprosy. Br Med J 1989;298:1423–5.

- Kramer N, Rosenstein ED. Rheumatologic manifestations of tuberculosis. Bull Rheum Dis 1997;46:5–8.

- Pang HN, Lee JYL, Puhaindran ME, et al. Mycobacterium marinum as a cause of chronic granulomatous tenosynovitis in the hand. J Infection 2007;54:584–8.

- Hess CL, Wolock BS, Murphy MS. Mycobacterium marinum infection of the upper extremity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:55–9.

- Murdoch DM, McDonald JR. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare cellulitis occurring with septic arthritis after joint injection: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:9.

- Cunningham WF. Streptococcus and rheumatic fever. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012;24:408–16.

- Parks T, Smeesters PR, Steer AC. Streptococcal infection and rheumatic heart disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;25:145–53.

- Fuller LC. Epidemiology of scabies. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26:123–6.

- Burke RJ, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria of acute rheumatic fever. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:503–7.

- Cunningham MW. Rheumatic fever, autoimmunity, and molecular mimicry: the streptococcal connection. Int Rev Immunol 2014;33:314–29.

- Jamieson N, Singh-Grewal D. Kawasaki disease. A clinician's update. Int J Pediatr 2013;645391 (epub oct 2013).

- Gong WG, McCrindle BW, Ching JC, et al. Arthritis presenting during the acute phase of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 2006; 148:800–5.

- Puéchal X, Fenollar F, Raoult D. Cultivation of Tropheryma whipplei from the synovial fluid in Whipple's arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1713–18.

- Fenollar F, Lagier JC, Raoult D. Tropheryma whipplei and Whipple's disease. J Infect 2014;69:103–12.

- Puéchal X. Whipple's disease. Joint Bone Spin 2002;69:133–40.

- Canal L, Fuente D de L, Rodriguez-Moreno J, et al. Specific cutaneous involvement in Whipple disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2014;36:344–6.

- Paul J, Schaller J, Rohwedder A, et al. Treated Whipple disease with erythema nodosum leprosum-like lesions: cutaneous PAS-positive macrophages slowly decrease with time and are associated with lymphangiectases; a case report. Am J Dermatopathol 2012;34:182–7.

Other infective arthropathies

- Kumar KT, Narasimhan A, Gopalakrishnan R, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in Chennai. J Assn Physicians India 2011;59:172–4.

- van de Sande WW. Global burden of human mycetoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(11):e2550.

- Fahal AH, Shaheen S, Jones DH. The orthopaedic aspects of mycetoma. Bone Joint J 2014;96–B(3):420–5.

- Mellor-Pita S, Yebra-Bango M, Tutor de Ureta P, et al. Polyarthritis caused by leishmania in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22:131.

Seronegative arthritis and spondylitis

- Scheinfeld N. Diseases associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: part 2 of a series on hidradenitis. Dermatol Online J 2013;19:18558.

- Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Li VW, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a retrospective review of patient characteristics, comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1244–50.

Rheumatoid arthritis

- Stack RJ, van Tuyl LH, Sloots M, et al. Symptom complexes in patients with seropositive arthralgia and in patients newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative exploration of symptom development. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1646–53.

- Oiso N, Suzuki T, Fukai K, et al. Nonsegmental vitiligo and autoimmune mechanism. Dermatol Res Pract 2011;518090.

Atrophic skin with rheumatoid arthritis

- McConkey B. Transparent skin and osteoporosis. A study of patients with rheumatoid disease. Ann Rheum Dis 1965;24:219–23.

- Shuster S, Raffle E, Bottoms E. Skin collagen in rheumatoid arthritis and the effect of corticosteroids. Lancet 1967;i:525–7.

- Ethgen O. de Lamos Esteves F, Bruyere O, et al. What do we know about the safety of corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Med Res Opinion 2013;29:1147–60.

- Adam M, Vitasek R, Deyl Z, et al. Collagen in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chim Acta 1976;70:61–9.

- Praderio L, Marian JF, Baldini V. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med 1987;147:206–7.

Inflammatory arthropathies

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid nodules

- Clarke JT, Werth VP. Rheumatic manifestations of skin disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010;22:78–84.

- Yamamoto T. Cutaneous necrobiotic conditions associated with rheumatoid arthritis; important extra-articular involvement. Mod Rheumatol 2013;23:617–22.

- Mouterde G, Lukas C, Goupille P, et al. Association of anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and/or rheumatoid factor status and clinical presentation in early arthritis: results from the ESPOIR cohort. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1614–22.

- Sautner J, Rintelan B, Leeb BF. Rituximab as effective treatment in a case of severe subcutaneous nodulosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1535–7.

- Kremer JM, Lee JK. The safety and efficacy of the use of methotrexate in long-term therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:822–31.

- Kersten PJ, Boerboom AM, Jeurisse ME, et al. Accelerated nodulosis during low dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis; an analysis of ten cases. J Rheumatol 1992;19:867–71.

- Segal R, Caspi D, Tishler M, et al. Accelerated nodulosis and vasculitis during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:1182–9.

- Bekun Y, Abou Alta I, Rubinow A, et al. 2756GG genotype of methionine synthase reductase gene is more prevalent in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate and is associated with methotrexate-induced nodulosis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1164–9.

Rheumatoid vasculitis and cutaneous ulceration

- Ohashi T, Miura T, Yamamoto T. Auricular pyoderma gangrenosum with penetration in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2014 Jun 10 (epub ahead of print).

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum; a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2006;55:505–9.

- Teagle A, Hargest R. Management of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Roy Soc Med 2014;107:228–36.

- Cinotti E, Labeille B, Perrot JL, et al. Certolizumab for the treatment of refractory disseminated pyoderma gangrenosum associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014;39:750–1.

- Ichihara A, Jinnin M, Fukushima S, et al. Case of disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. J Dermatol 2014;41:414–17.

- Tanaka A, Hayaishi N, Kondo Y, et al. Severe gangrene accompanied by varicella zoster virus-related vasculitis mimicking rheumatoid vasculitis. Case Rep Dermatol 2014;6:103–7.

- Seitz CS, Berens N, Bröcker EB, et al. Leg ulceration in rheumatoid arthritis – an underestimated multicausal complication with considerable morbidity: analysis of thirty-six patients and review of the literature. Dermatology 2010;220:268–73.

- Chia HY, Tang MB. Chronic leg ulcers in adult patients with rheumatological diseases – a 7 year retrospective review. Int Wound J 2014;11:601–4.

- Hasegawa M, Nagai Y, Sogabe Y, et al. Clinical analysis of leg ulcers and gangrene in rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol 2013;40:949–54.

- Kurian A, Haber R. Methotrexate-induced cutaneous ulcers in a non-psoriatic patient: case report band review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg 2011;15:275–9.

- Turesson C, Matteson EL. Vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009;21:35–40.

- Firth J, Waxman R, Law G, et al. The predictors of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:615–21.

Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis

- Prat L, Bouaziz JD, Wallach JD, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol 2014;32:376–88.

- Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph-Y, Rodriguez-Acosta ED. Autoimmunity-related neutrophilic dermatosis: a newly described entity that is not exclusive of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:655–60.

- Bevin AA, Steger J, Mannino S. Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis. Cutis 2006;78:133–6.

- Kreuter A, Rose C, Zillikens D, et al. Bullous rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:916–18.

- Fujio Y, Funakoshi T, Nakayama K, et al. Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis with tense blister formation: a case report and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol 2014;55:e12–14.

- Yamamoto T. Cutaneous manifestations associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2009;29:979–88.

Fibroblastic rheumatism

- Romas E, Finlay M, Woodruff T. The arthropathy of fibroblastic rheumatism. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:183–7.

- Paupitz JA, de Carvalho JF. Good clinical response to methotrexate treatment in a patient with fibroblastic rheumatism. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:1789–91.

- Cabral R, Brinca A, Cardoso JC, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism – a case report. Acta Reumatol Port 2013;38:128–30.

- Marconi IM, Rivitti-Machado MC, Sotto MN, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:29–32.

- Jurado SA, Alvin GK, Selim MA, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism; a report of 4 cases with potential therapeutic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66:959–65.

- Ji L, Genq Y, Hao Y, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: an addition to fibromatosis. Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:519–21.

- Zelger B, Burgdorf W. Fibroblastic rheumatism: a variant of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis? Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20:461–2.

- Kluger N, Dumas-Tesici A, Hamel D. Fibroblastic rheumatism: fibromatosis rather than non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:587–92.

- Trotta F, Colina M. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis and fibroblastic rheumatism. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol 2012;26:543–7.

- Courties A, Guégan S, Miquel A, et al. Fibroblastic rheumatism: immunosuppressive therapy is not always required. Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:178–9.

- Romiti R, Levy Neto M, Manta Simonsen Nico M. Response of fibroblastic rheumatism to infliximab. Dermatol Res Pract 2009;715729 (epub).

Sarcoidosis

- Spilberg I, Siltzbach LE, McEwen C. The arthritis of sarcoidosis. Arthritis Rheum 1969;12:126–37.

- Motomiya M, Iwasaki N, Kawamura D. Finger flexion contracture due to muscular involvement in sarcoidosis. Hand Surg 2013; 18:85–7.

- Thelier N, Assous N, Job-Deslandre C, et al. Osteoarticular involvement in a series of 100 patients with sarcoidosis referred to rheumatology departments. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1622–8.

- Kobak S, Sevar F, Ince O, et al. The prevalence of sacroiliitis and spondyloarthritis in patients with sarcoidoisis. Int J Rheumatol 2014;2014:289454.

- Kiltz U, Braun J. Use of methotrexate in patients with sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28:S183–5.

- Mehta B, Efthimiou P. Radiographic improvement in sarcoid arthropathy after infliximab treatment. J Rheumatol 2012;39:664–5.

- Banse C, Bisson-Vaivre A, Kozyreff-Meurice M, et al. No impact of tumor necrosis-factor antagonists in the joint manifestations of sarcoidosis. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:605–11.

- Blau EB. Familial granulomatous arthritis, iritis and a rash. J Pediatr 1985;107:689–93.

Heberden and Bouchard nodes

- Kellgren JH, Moore R. Generalised osteoarthritis and Heberden's nodes. BMJ 1952;i:181–7.

- Stecker RM. Heberden's nodes. A clinical description of osteoarthritis of the finger joints. Ann Rheum Dis 1953;48:523–7.

- Irlenbusch U, Dominick G. Investigations into generalized osteoarthritis. Part 1: genetic study of Heberden's nodes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006;14:423–7.

- Rees F, Doherty S, Hui M, et al. Distribution of finger nodes and their association with underlying radiographic features of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:533–8.

- Doherty M, Pattrick M, Powell RJ. Hypothesis – nodal generalised osteoarthritis is an auto-immune disease. Ann Rheum Dis 1990;49:1017–20.

Haemochromatosis

- Husar-Memmer E, Stadlmayr A, Datz C, et al. HFE-related hemochromatosis; an update for the rheumatologist. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014;16:393.

Alkaptonuria

- Borman P, Bodur H, Ciliz D, et al. Ochronotic arthropathy. Rheumatol Int 2002;21:205–9.

- Keller JM, Macauley W, Nercessian OA, et al. New developments in ochronosis: review of the literature. Rheumatol Int 2005;25:81–5.

Metabolic disorders with musculoskeletal and cutaneous involvement

Gout

- Sapkota K, Kolade VO, Boit ML. Gouty tophi. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2014;4:10.3402.

- Gupta A, Rai S, Sinha R, et al. Tophi as an initial manifestation of gout. J Cytol 2009;26:165–6.

- Iglesias A, Londono JC, Saiibi DL, et al. Gout nodulosis: widespread subcutaneous deposits without gout. Arthritis Care Res 1996;9:74–7.

- Ryan JG, Goldbach-Mansky R. The spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases; recent bench to bedside observations. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2008;20:66–75.

- Dalbeth N, House ME, Horne A, et al. Reduced creatinine clearance is associated with early development of subcutaneous tophi in people with gout. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2013;14:363.

- Lam MP, Yeung CR, Cheung BM. Pharmacogenetics of allopurinol – making an old drug safer. J Clin Pharmacol 2013;53:675–9.

Autoinflammatory disorders

Acne

- Knitzer RH, Needleman BW. Musculoskeletal syndromes associated with acne. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1991;20:247–55.

- Lim DT, James NM, Hassan S, et al. Spondyloarthritis associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a review with illustrative cases. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:346.

- Barbareschi M, Paresce E, Chiaratti A, et al. Unilateral sacroiliitis associated with systemic isotretinoin treatment. Int J Dermatol 2010;49:331–3.

- Geller AS, Alagia RF. Sacroiliitis after use of oral isotretinoin – association with acne fulminans or adverse effect? An Bras Dermatol 2013;88(6 Suppl. 1):193–6.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Rosner IA, Burg CG, Wisnieski JJ, et al. The clinical spectrum of the arthropathy associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and acne conglobata. J Rheumatol 1993;20:684–7.

- Richette P, Molto A, Vignier M, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and spondyloarthritis: results from a multicenter national prospective study. J Rheumatol 2014;41:490–4.

Inflammatory chondropathies

Relapsing polychondritis

- McAdam LP, O'Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective review of 23 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:193–215.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmune Rev 2014;13:90–50.

- Ebringer R, Rook G, Swana GT, et al. Autoantibodies to cartilage and type II collagen in relapsing polychondritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1981;40:473–9.

- Foidart JM, Abe S, Martin GR, et al. Antibodies to type II collagen in relapsing polychondritis. N Engl J Med 1978;299:1203–7.

- Ridgeway HB, Hansotia PL, Schorr WF, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Unusual neurological features and therapeutic efficacy of dapsone. Arch Dermatol 1979;115:43–5.

- Ueno Y, Chai D, Barnatt EV. Relapsing polychondritis associated with ulcerative colitis: serial determinations of antibodies to cartilage and circulating immune complex by three assays. J Rheumatol 1981;8:456–61.

- Anstey A, Mayou S, Morgan K, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: autoimmunity to type II collagen and treatment with cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol 1991;125:588–91.

- Cremer MA, Rosloniec EF, Kang AH. The cartilage collagens: a review of their structure, organization and role in the pathogenesis of experimental arthritis in animals and in human rheumatic disease. J Mol Med 1998;76:275–88.

- McCluskey RT, Thomas L. The removal of cartilage matrix in vivo by papain. J Exp Med 1958;108:371–84.

- Gange RW. Relapsing polychondritis. Report of two cases with an immuno-pathological review. Clin Exp Dermatol 1976;1:261–6.

- Saxne T, Heinegard D. Serum concentrations of two cartilage matrix proteins reflecting different aspects of cartilage turnover in relapsing polychondritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:294–6.

- Puéchal X, Ternier B, Mouthon L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:118–24.

- Sato T, Yamano Y, Tomaru U, et al. Serum level of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 as a biomarker of disease activity in relapsing polychondritis. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:129–36.

- Berger R. Polychondritis resulting from i.v. substance abuse. Am J Med 1988;85:415–17.

- Borbujo J, Balsa A, Aguado P, et al. Relapsing polychondritis associated with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20:130–2.

- Conti JA, Colicchio AR, Howard LM, et al. Thymoma, myasthenia gravis and relapsing polychondritis. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:163–4.

- Nield GH, Cameron JS, Lessof MH, et al. Relapsing polychondritis with crescentic glomerulonephritis. BMJ 1978;i:743–5.

- Pazirandeh M, Ziran BH, Khandelwal BK, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol 1988;15:630–2.

- Michet CJ, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, et al. Relapsing polychondritis; survival and predictive role of disease manifestation. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:74–8.

- Labarthe MP, Bayle-Lebey P, Bazex J. Cutaneous manifestations of relapsing polychondritis in a patient receiving goserelin for carcinoma of the prostate. Dermatology 1997;195:391–4.

- Small P, Black M, Davidman M, et al. Wegener's granulomatosis and relapsing polychondritis: a case-report. J Rheumatol 1980;7:915–18.

- Papo T, Piette J-C, Le Thi Huong DU, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in polychondritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1993;52:384–5.

- Kaye RL, Sones DA. Relapsing polychondritis: clinical and pathological features in 14 cases. Ann Intern Med 1964;60:653–64.

- Michet CJ. Vasculitis and relapsing polychondritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1990;16:441–4.

- Damiani J, Levine H. Relapsing polychondritis. Report of 10 cases. Laryngoscope 1979;89:929–46.

- Dolan DL, Lemmon GB, Teitelbaum SL. Relapsing polychondritis. Analytical literature review. Am J Med 1966;41:285–99.

- Hughes RAC, Berry CL, Seifert M, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Three cases with a clinicopathological study and literature review. Q J Med 1972;41:363–80.

- Cantarini L, Vitale A, Brizi MG, et al. Diagnosis and classification of relapsing polychondritis. J Autoimmun 2014;48–49:53–9.

- Balsa-Criada A, Garcia-Fernandez F, Roldan I, et al. Cardiac involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Int J Cardiol 1987;14:381–3.

- Van Decker W, Panidis IP. Relapsing polychondritis and cardiac valvular involvement. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:340–1.

- Bradley JC, Schwab IR. Blue ear sign in relapsing polychondritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:427.

- Moloney JR. Relapsing polychondritis – its otolaryngological manifestations. J Laryngol Otol 1978;92:9–14.

- Schreiber BE, Twigg S, Marais J, et al. Saddle-nose deformities in the rheumatology clinic. Ear Nose Throat J 2014;93(4–5):E45–7.

- Stewart SS. Cerebral vasculitis in relapsing polychondritis. Neurology 1988;38:150–2.

- Tronguoy AF, de Quatrebarbes J, Picard D, et al. Papular and annular fixed urticarial eruption: a characteristic skin manifestation in patients with relapsing polychondritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1161–6.

- Franssen MJ, Boerbooms AM, van de Putt LB. Polychondritis and rheumatoid arthritis, case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 1987;6:453–7.

- McKay DA, Watson PG, Lyne AJ. Relapsing polychondritis and eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol 1974;58:600–5.

- Crovato F, Nigro A, de Marchi R, et al. Exophthalmos in relapsing polychondritis. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:383–4.

- Marshall DAS, Jackson R, Rae AP, et al. Early aortic valve cusp rupture in relapsing polychondritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51:413–15.

- Buckley LM, Ades PA. Progressive aortic valve inflammation occurring despite apparent remission of relapsing polychondritis. Arthritis Rheum 1992;35:812–14.

- Arnaud L, Devilliers H, Peng SL, et al. The Relapsing Polychondritis Disease Activity Index; development of a disease activity score for relapsing polychondritis. Autoimmun Rev 2012;12:204–9.

- Papo T, Wechsler B, Bletry O, et al. Pregnancy in relapsing polychondritis; twenty-five pregnancies in eleven patients. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1245–9.

- Deng H, Chen P, Wang L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis on PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2012;37:712–15.

- Mark KA, Franks AG. Colchicine and indometacin for the treatment of relapsing polychondritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:S22–4.

- Stewart KA, Mazanec DJ. Pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide for kidney disease in relapsing polychondritis. J Rheumatol 1992;19:498–500.

- Temier B, Aouba A, Bienvenu B, et al. Complete remission in refractory relapsing polychondritis with intravenous immunoglobulin. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26;136–8.

- Seymour MW, Home DM, Williams RO, et al. Prolonged response to anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment with adalimumab (Humira) in relapsing polychondritis complicated by aortitis. Rheumatology 2007;46:1738–9.

- Navarete VM, Lebrón CV, de Miera FJ, et al. Sustained remission of pediatric relapsing polychondritis with adalimumab. J Clin Rheumatol 2014;20:45–6.

- Rosen O, Thiel A, Massenkeil G, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in refractory auto-immune diseases after in vivo immunoablation and ex vivo depletion of mononuclear cells. Arthritis Res 2000;2:327–36.

MAGIC syndrome

- Orme RL, Nordlund JJ, Barich L, et al. The MAGIC syndrome (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage). Arch Dermatol 1990;126:940–4.

- doNascimento AC, Gaspardo DB, Cortez TM, et al. Syndrome in question. MAGIC syndrome. An Bras Dermatol 2014;89:177–9.

- Firestein GS, Gruber HE, Weisman MH, et al. Mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage: MAGIC syndrome. Am J Med 1985;79:69–72.

- Le Thi Huong DU, Wechsler B, Piette J-C, et al. Aortic insufficiency and recurrent valve prosthesis dehiscence in MAGIC syndrome. J Rheumatol 1993;20:397–8.

- Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Sabio-Sánchez JM, Linares PJ, et al. Magic syndrome and true aortic aneurysm. Clin Rheumatol 2008;27:115–17.